ABSTRACT

High quality of teacher–student relationships is widely recognized as fundamental part of good education. Moreover, students’ self-efficacy beliefs, or their confidence to succeed within different domains at school, are important impact factors to achievement. Although there is support for an association between student-perceived teacher–student relationship quality and students’ self-efficacy judgements, which mediates achievement, no tool explores this association. This article suggests that two instruments, respectively measuring students’ perceptions of teacher–student relationship quality (TSR) and student’s self-efficacy (SSE), can be used in parallel for a multifaceted exploration of individual students’ perception of TSR quality, in relationship to their self-efficacy. Two well-established instruments were adopted, validated and their factor structures re-confirmed in a Swedish sample, using data from students in five schools (n=382). Factor analysis showed that models with three underlying dimensions of TSR and four underlying dimensions of SSE were the most appropriate. All sub-scales showed good-to-excellent reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.75–0.94). Findings indicated a lack of multigroup invariance across gender and school level for the TSR-model. Substantial associations were found between student-perceived teacher support, and students’ self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and global academic success. We discuss utility and limitations, need of model improvement, and future potential.

Introduction

High quality of teacher–student relationships (TSR) with trustful interaction between adults and youth at school are recognised as a fundamental part of good education (Biesta, Citation2004; Hattie, Citation2009). Biesta (Citation2004, p. 13) stresses that education takes place in the interactional space between learner and educator. Education is understood as a sense-making process that grows in mutual communication through participation in educational relationships. In Hattie’s comprehensive meta-analysis of factors influencing achievement the relational aspect of teaching is pointed out as a key factor: “the most critical aspects contributed by the teacher are the quality of the teacher and the nature of the teacher–student relationships” (Hattie, Citation2009, p. 126). Within trustful educational relationships, teachers contribute to individual students’ positive identity as learners. Such an identity includes students’ confidence in own capability for self-regulation of learning and for social interaction in school (Bandura, Citation1989). Students’ self-belief and expectations are highly associated with learning outcomes (Hattie, Citation2009). In this article, a tool is developed that facilitates a deeper investigation of individual students’ perception of the teacher–student relationship quality, in relationship to their self-efficacy beliefs. Two instruments provide a relational complement to test results and grade points for monitoring school development, and a relational alternative in assessment of educational quality. Such relational assessment is widely asked for by researchers and practitioners who stress an even more instrumental instruction tends to dehumanise education, rather than to develop it (Ashan & Smith, Citation2016; Allodi Westling, Citation2013; Au, Citation2007; Biesta, Citation2010; Braun, Citation2017).

Internationally there is vast research focusing on TSR-quality and its influence on various aspects of student learning. Despite variation in theoretical underpinnings (e.g. attachment theory or social support theories) researchers have identified one positive relational dimension (support) and one negative (conflict) while measuring teachers’ and students’ appreciations of TSR quality (Li, Hughes & Kwok, Citation2012; Roorda & Koomen, Citation2011). TSRs characterised by a high level of emotional support and low level of conflict show association with student engagement, sense of belonging at school, cooperation in class, positive peer relations and attitudes towards school, adaptive behaviour, academic self-efficacy and achievement. TSRs characterised by a low level of support and high level of conflict associate with externalising behaviour, retention, peer rejection, truancy and school dropout (Baker, Citation2006; Hamre & Pianta, Citation2006; Hughes, Citation2011; Murray, Waas, & Murray, Citation2008; O’Connor, Dearing, & Collins, Citation2011; Roorda & Koomen, Citation2011; Wentzel, Citation2012). An important finding is that ratings of TSR quality made by the teachers has different implications than ratings made by students. In a longitudinal study, Hughes (Citation2011) found in a sample of 714 at-risk students and their teachers large differences: While students’ appreciation of TSR quality uniquely predicted change in student-perceived academic competence, sense of belonging at school and maths achievement, teachers’ appreciations of TSR quality instead uniquely predicted teacher-perceived student behaviour and engagement (Hughes, Citation2011, p. 38). Such findings emphasise the importance of exploring the student perspective.

Within the framework of social cognitive theory (Bandura, Citation1989), students’ expectations, self-beliefs and confidence in own chances to succeed within different domains of school have been explored in terms of student’s self-efficacy. Empirical studies confirm student self-efficacy (SSE) for self-regulated learning (task performing, organising and maintaining good habits for learning, persistence), social interaction (peer relationships) and academic performance correlate with students’ well-being, social adjustment and achievement (Fertman & Primack, Citation2009; Klassen, Citation2010; Martin & Rimm-Kauffman, Citation2015; Wesson & Derrer-Rendall, Citation2011; Zuffiano et al., Citation2013).

When it comes to the interrelationship between TSR quality and SSE, Bandura (Citation1989) hypothesised a big impact of teachers’ attitude on students’ self-efficacy. Teacher’s expectations, interpretations and responding to students’ actions, successes and failures may be either favourable or unfavourable to students’ self-efficacy judgements. At the same time, the way students think about themselves as learners and the way they view themselves as interactive partners affects how they interpret the response they get from their teachers and peers, and their own relational response (Klassen, Citation2010). Essentially, the interrelationship between TSR and SSE is thus regarded to be bidirectional.

A few studies investigated the relationship between TSR and SSE directly. Li et al. (Citation2012) found associations between student reports of supportive TSRs and subject-specific self-efficacy (maths and reading). In a longitudinal study, Hughes (Citation2011) found that students’ perceptions of warmth and support in TSRs predicted positive change in academic self-efficacy. In another study, student-reported TSR-conflict had an effect on maths achievement over time, but this effect was regarded as mediated through students’ self-efficacy (Hughes, Wu, Kwok, Villarreal, and Johnson (Citation2012).

To summarise, student-perceived TSR quality and SSE are highlighted as impact factors to students’ wellbeing and learning in international research. There are also theoretical support and some empirical evidence for their interrelatedness. However, this relationship has been explored only to little extent. In Scandinavia, no instruments that measure these two constructs either separately or in relation to one another has been developed.

Our intention is to implement two instruments in one study in order to be able to simultaneously measure individual students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE. The data collected using these instruments is expected to enable a more valid and multifaceted exploration of the association between student-perceived TSR quality and various aspects of SSE. Simultaneous measurement ensures convergence in the data collection process because information and guidance can be offered to all respondents in a cohesive way by the same trained person at the same time point. Moreover, the data collection process could become more homogeneous regarding the participants’ level of engagement to participate, their way of thinking, their feelings and experiences at the time of study. Further, one tool (rather than two separate ones) reduces risk of method bias (de Vijver & Hambleton, Citation1996), and facilitates administration (e.g. for consents and recruitment) and, hence, reduces burden on already strained school staff.

The aims of the article are i) to describe the development process of the “Swedish TSR-SSE Survey” with its theoretical and empirical backgrounds and ii) to validate the new instruments and to reconfirm their latent factor structures. Additionally, the empirical analysis explores the interrelation between Swedish students’ perceptions of TSR and SSE.

Mapping existing instruments

Searching for an instrument that measured both quality in interpersonal teacher–student relationships and students’ self-efficacy beliefs yielded no results in international databases (e.g. Ebsco, Scopus, ProQuest, Google Scholar) or when reviewing an extensive research measures collection provided online at Washington University (Citation2012).Footnote1 However, one could see that there were a number of articles on instruments related to each domain. Fifteen instruments were evaluated concerning theoretical relevance, area of use and availability. From those, three American instruments were selected for further exploration: two measures related to TSR quality, and one related to SSE. The selected instruments met the specific research interest of this study: to investigate individual students’ perceptions of relationship quality in interpersonal relationships with individual teachers, and self-efficacy. One excluded TSR-instrument exemplifies the selection criteria: “The Questionnaire on Teacher Interaction” (QTI), which is based on relational theory (Telli & den Brok, Citation2012), measures students’ perceptions of teacher classroom management and operates at group level, i.e. “If we have something to say, this teacher will listen”. Hence, it does not explore the interpersonal relationship between individual students and teachers, which is the study object of this work. Regarding the SSE-part, the selection was due to our theoretical interest to examine the interrelatedness between TSR-quality and a wider spectrum of students’ self-efficacy judgements: global academic self-efficacy, self-efficacy for self-regulated learning and for peer-social interaction.

Teacher – student relationship

The results of our inquiries showed that the teacher perspective was mostly in focus. Fewer studies concerned the child perspective. After more specified searches, a handful of articles remained that discussed the child perspective of TSR-quality. Most of these articles contained information on variations of two instruments: the “Teacher Relationship Inventory” (TRI) and the “Student–Teacher Relationship Scale” (STRS).

The TRI instrument dates back to Weiss’s theory of social provision (Weiss, Citation1974), on which Furman and Buhrmester (Citation1985) built their “Network of Relationships Inventory” (NRI). The NRI aimed to investigate the interaction effects of the quality in children’s different relationships to significant persons in their lives, namely parents, siblings, grandparents, friends, school peers and teachers. Due to Weiss’s functional perspective of relationships, children seek social support in all kinds of close relationships, but with different qualities, and to a varying extent. The theory stipulates six basic functional social provisions from close relationships: 1) attachment (security, affection and intimate disclosure), 2) reliable alliance (a dependable bond), 3) enhancement of worth, 4) companionship (belonging, sharing of experience), 5) guidance and 6) opportunity to nurture and take care of others. In addition to Weiss’s social provision and support dimension, Furman and Buhrmester (Citation1985) paid attention to two other dimensions in interpersonal relationships frequently discussed in the literature; the ones of relative power and conflict. These aspects represent a dynamic nature of interdependency in relationships, rather than functional support (Furman & Buhrmester, Citation1985).

The NRI was adapted to school research by Jan Hughes and colleagues during the latter part of the 1990s (Hughes & Kwok, Citation2007). Based on chosen items they created the 22-item Teacher Relationship Inventory (TRI) in which students were to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale their appreciated level of support (16 items) and conflict (6 items) in their relationships to their teachers. Even though a bidimensional model was assumed, factor analyzes in repeated studies (Hughes, Citation2011; Hughes & Kwok, Citation2007) suggested a three-factor model, with intimacy (composed of several items from the support-scale) as a third dimension. Confirmatory factor analysis on data from 392 third-graders showed good fit for the three-factor model (see Hughes, Citation2011). Nevertheless, researchers have chosen to compute one total support score, composed of all 16 items, arguing that both the support and the intimacy scale assess positive relatedness, and at the same time the correlations between the two scales were moderately high (Hughes & Kwok, Citation2007). In some later studies, only a warmth (the support minus the intimacy items) and the conflict scales have been analysed (Hughes, Citation2011; Wu, Hughes, & Kwok, Citation2010). As a measure of relationship support, the warmth scale as compared to the intimacy scale was regarded as being better at capturing teacher provision of social support and has also been more consistent in predicting child adjustment (Hughes et al., Citation2012).

The Student–Teacher Relationship Scale (STRS) was originally created by Pianta and Nemitz (Citation1991) and later adopted and used in several countries (Drugli & Hjemdal, Citation2013; Patricio, Barata, Calheiros, & Graca, Citation2015). The STRS is based on attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1988), which posits that infants during the first years of life, in interplay with early caregivers, develop internal working models for subsequent interaction in interpersonal relationships. Such relational foundations may be of great predictive importance for the developing trajectories of the quality in teacher–student relationships (Baker, Citation2006; O’Connor et al., Citation2011; Ubha & Cahill, Citation2014).

The similarities between the development of the respective TRI and the STRS are noteworthy: both instruments rely on interpersonal relational theories, and both extract a predominantly bi-dimensional dichotomy of a similar nature, i.e. that of support/closeness and conflict in the teacher–student relation. In both instruments there is also a third dimension appearing in recurrent factor analyzes, having a less predictable and more difficult nature for the researchers to interpret. Two main reasons motivated disregarding the STRS for the Swedish instrument. First, the STRS was designed for teachers’ assessment of TSR quality with students aged 3–8, a notably younger group than the target group in this research. Second, at the time, STRS only measured the adult perspective (later, a student version of the STRS was published by Koomen & Jellesma, Citation2015).

Student self-efficacy

Bandura (Citation1990) developed the Multidimensional Scales of Perceived Self-Efficacy as a general tool to explore self-efficacy beliefs and its implications in understanding individual and collective behaviour in a wide range of social contexts. The instrument was composed of domain-specific variables aimed to capture self-efficacy beliefs within different life-domains. One subscale was developed as the Children’s Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES). It explores children’s self-efficacy beliefs in different social contexts, among which school is one of great importance (Usher & Pajares, Citation2008). From the CSES scale, several items have been used in school research in a number of studies. Bandura and colleagues (Citation2001) committed data from a study using a 37-item version of the instrument to principal component analysis and found three underlying components: academic self-efficacy, social self-efficacy and self-regulatory self-efficacy. Academic self-efficacy expresses the general view of students’ expectations on how well they will perform at school. Social self-efficacy captures students’ appreciation of their ability to handle relations, sense of belonging at school and self-assertiveness. Self-regulatory self-efficacy finally expresses students’ confidence in own ability to maintain well-functioning learning strategies (Bandura et al., Citation2001).

Zimmerman, Bandura, and Martinez-Pons (Citation1992) specified an 11-item measure for the self-regulatory self-efficacy dimension through principal component analysis (PCA) on data from the original CSEC-scale. Sample of typical items were: “how well can you finish studying when there are other interesting things to do?”, and “how well can you concentrate in class?”. This measure has shown validity and reliability in studies of students with and without learning disabilities (Klassen, Citation2010; Zuffianò et al., Citation2013). More analyzes, by other researchers, confirmed that there is a unidimensional self-efficacy for self-regulated learning factor underlying the original items from Bandura (Choi, Fuqua, & Griffin, Citation2001; in Usher & Pajares, Citation2008). Usher and Pajares (Citation2008) designed an extensive study, but with only 7 items, since professionals judged 4 items to be of low relevance to current school contexts. Factor analysis confirmed a unidimensional model in large student data (n = 3670). Further, their analyzes showed the self-efficacy for self-regulated learning scale to be invariant for girls and boys and likewise invariant between elementary, middle and high-school students (Usher & Pajares, Citation2008).

Bringing together students’ self-efficacy for self-regulative learning and social self-efficacy with self-efficacy in resisting drugs, Fertman and Primack (Citation2009) also adopted items from Banduras’ original CSES-scale. In a study with 392 fourth and fifth graders they changed the wordings of the chosen items from third person (How well do You …) to first person (I feel confident that …) and updated the language and made reading easier. They further changed the response-set to a 5-point Likert scale. A composed instrument of SSE was established, with 20 items together mirroring three domains of students’ self-efficacy. The three dimensions were confirmed in principal component analysis. The first dimension, labelled “Perceived Learning Self Efficacy”, consisted of nine items very similar to Usher and Pajares’ extracted factor of self-efficacy for self-regulated learning. The second factor, “Perceived Peer Self Efficacy”, consisted of eight items similar to the social self-efficacy construct earlier extracted by Bandura and colleges (Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, Citation1996). Finally, the third subscale “Perceived Drug Use Self Efficacy” was a 3-item construct created by the researchers for their study-specific purpose (Fertman & Primack, Citation2009). Analyzes showed that all three subscales were consistent with “good-to-excellent” internal reliability. The two scales for self-regulative- and social self-efficacy showed to be invariant over school, gender, grade level and ethnical background. Moreover, both scales were correlated to each of the different social-support scales (from the Child and Adolescent Social Support Scale) and the different social-skills scales (from the Social Skills Rating System) that were used for concurrent validation (Fertman & Primack, Citation2009).

To summarise, mapping existing instruments ended in two different American instruments, one of each developed within the respective TSR and SSE domains. The two instruments show partial theoretical interrelatedness and relevance for theoretical assumptions about the relationships between TSR quality and SSE. In the next section, the development and validation process of a new tool with two instruments are described.

Swedish TSR-SSE survey

Adaptation

Both of the American instruments were judged translatable (Brislin, Citation1986, pp. 137–150), and possible to adapt to a Scandinavian context. However, adapting instruments between cultures requires accuracy. According to de Vijver and Hambleton (Citation1996), three significant threats to the adequacy of instrument translations/adaptations are i) construct bias, ii) method bias and iii) item bias. These risks are especially crucial to address while adopting instruments for cross-cultural comparisons, but several recommended measures to minimise bias are also important while translating/adopting instruments for intra-cultural use, like in our case. We took the following measures, which correspond to the authors’ recommendations.

Construct bias is related to non-equivalence of constructs between cultures (de Vijver & Hambleton, Citation1996). For instance, the American school culture differs from the Swedish school culture, thus the nature of, and students’ perceptions of, the teacher–student relationship may differ as well. To cope with such challenges, we carefully explored any ethnocentric bias in our theories for operationalisation. The two constructs were scrutinised from a Swedish school culture perspective in several steps. The theoretical foundations of the American instruments (as presented above) were discussed within an expert group consisting of university lecturers and experienced school professionals, and judged recognisable in the Swedish context. All subscales and wordings of the original items were audited in the group as well, and further compared to current Swedish school documents and literature by the researcher. No major cultural mismatch was obtained during this process. Nevertheless, some wordings and concepts were changed in consensus. For a few items, differing views were obtained among the professionals. The decision was made to further evaluate these items based on upcoming student responses.

Method bias concerns, for example, differences in social desirability, various familiarity to stimuli and response formats, and different physical and relational conditions in the response situation (de Vijver & Hambleton, Citation1996). For our intracultural instrument use, these issues mainly become a matter of creating comprehensible questionnaires, and ensuring as equal, well-informed, and safe conditions as possible for the responding students in all schools. The measures taken are described below (“Participants and procedure”). Item bias finally, concern anomalies at the item level (e.g. poor wording, inappropriateness of content in the cultural group, inaccurate translation). We handled this risk of mal-functioning of individual items in three steps: in the expert group (as described above), through piloting the instruments together with students (“Design and piloting”) and finally in the statistical analyses (de Vijver & Hambleton, Citation1996).

An English language academic translator was consulted. The professional translator and the author translated all items in parallel (forward translation), whereafter the two translations were exchanged, back-translated and mutually discussed (Brislin, Citation1986, p. 159; Dhamani & Richter, Citation2011; Majbar, Citation2019). In the agreed on version, some expressions chosen by the professional translator were changed to meet Swedish students’ way of expression. Finally, the last Swedish version was confirmed in the expert group.

Fertman’s and Primack’s (Citation2009) third subscale, the 3-items scale for students’ self-efficacy in resisting drugs, was not relevant to this research. A global school self-efficacy subscale, created by the first author, replaced it. The scale was closely concordant to Banduras’ academic self-efficacy dimension (Bandura et al., Citation2001) and further motivated by the researcher’s interest in exploring the relationship between students’ specific, and more short-sighted, self-efficacy for self-regulative learning and their prospective global expectations on schooling. Three new items were established for this purpose:

“I feel confident that: … I thrive in school and think that school work goes well”, “ … I will have a good time in school until the ninth grade” and “ … I will pass on all learning objectives when I finish school in the ninth grade”.

SSE1 (Student Self-Efficacy for Self- Regulated Learning)

SSE2 (Student Self-Efficacy for Peer Social Interaction)

SSE3 (Student Self-Efficacy for Global School-Success)

TSR1 (Teacher – Student Relationship – Support)

TSR2 (Teacher – Student Relationship – Conflict)

Table 1. All items. Means, modes and standard deviations. Dimensions and subscales.

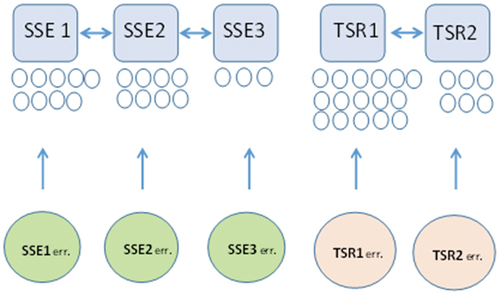

The hypothesised models of TSR and SSE are depicted in

Design and piloting

The instrument was designed as an on-line survey consisting of two parts. In the SSE part, items were presented on screen in clusters representing each of the three dimensions. All items begin with the wording “I feel confident that” followed by the specific expression that is to be valued, i.e. “I can always concentrate during class”. Five response alternatives were given: not at all apply/pretty bad apply/partly apply/fairly good apply/exactly apply. In the TSR part, items were presented on screen one at a time, with the response alternatives not at all/a little/quite much/much/very much.

The instrument was piloted in two steps. First, two boys and one girl (ages 9–11) responded to the first draft of the survey and took part in feedback talks together with the researcher. This led to minor changes in some wordings. In a second step, 25 fourth-graders (14 girls, 11 boys) in a multiethnic suburban school participated in a test round by responding to the instrument, some using the on-line version and some using pen and printed paper. In direct connection with responding to the questionnaires, the students participated in a retrospective debriefing interview (Dhamani & Richter, Citation2011) in which they were asked if they found any items difficult to understand, irrelevant or offensive, and about any other opinion on the instrument. The result was satisfying, with the conclusion that all students were able to read, understand and respond independently to the survey as a whole in a trustworthy way. The items that in the adaptation step were subject to discussion among professionals were not highlighted by the piloting students, and therefore these items remained until further notice in the statistical analysis.

Validation and testing the factor structure

The validation study based on the first data collected with the Swedish “TSR-SSE survey” has two main objectives. First, to examine the functionality and comprehensibility of the web-based instrument in data collection with Swedish students, aged 9–15. Second, to validate (confirm/restructure) the hypothesised factor model of the instruments, to test for multi-group invariance (Usher & Pajares, Citation2008) across gender and school level and to assess the internal reliability of all subscales.

Participants and procedure

Data were obtained from 198 middle-school students (4th – 6th grade) and 184 secondary-school students (7th – 8th grade), n = 382, attending five public schools in a big city county (see ). All participants, with their caregivers’ approval, had consented to respond to the survey. Data collection took place in classrooms with mixed student groups with a maximum size of 15 at a time, informed in person by the researcher or any other trained, unbiased person (teachers who worked closely with the students were not allowed to attend). The general purpose of the survey was explained in the same manner in all groups. The concept of “teacher–student relationship” was clarified and framed: students were asked to think about the teacher(s) they perceived to have the greatest influence over their schooling when responding to the TSR-part of the survey. Confidentiality in the handling of all collected data was carefully emphasised. Practical/technical support was given in order to secure well-functioning response procedures. In the procedure, a few students preferred the adult to read items aloud, and a few comprehensive questions occurred (concepts discussed were, i.e. “learning objectives” and “punish”).

Table 2. Participants and school information.

Statistical analysis

The overall instrument validation includes:

Descriptive analysis

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA): Model (re)specification, test of multi-group invariance

Exploratory steps: Correlation matrix investigation, item evaluation, Exploratory Factor Analyses (EFA)

Investigation of internal reliability of subscales, and subscale intra-correlations

Statistical analysis comprises three parts: (i) descriptive analysis including the examination of the correlation structure among the items, and exploration of factor structures; (ii) setting up the TSR and SSE models based on the theoretical considerations, refining and restructuring these models if necessary; testing for multi-group invariance; and (iii) assessment of internal consistency of subscales, and subscale intra-correlations.

The statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 22, and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), to calculate item means and reliability coefficients for the scales. The CFA model was performed using PROC CALIS of SAS/STAT® software.

Descriptive analysis

A number of questionnaires were reviewed individually to examine the performed functionality and credibility of the web-based survey. The coherence of 20 students’ responses to all items were assessed and judged trustworthy. In the whole dataset, responses were generally collected at the median, with a few outliers identified. Hence, one could claim the instrument has been understandable and that students have responded to it with good intentions and attention. Medians, modes and proportions were observed for all response alternatives. Histograms indicated right-sided skewness of distributions on most variables, which was in line with expectations since students generally scored high on both TSR and SSE in previous studies with the original instruments (Hughes, Citation2011; Usher & Pajares, Citation2008). Means, standard deviations and modes for all items are displayed in . Intercorrelations between all items are displayed in the Appendix Tables A1 and A2.

Factor analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the hypothesised relationship between the survey items. 20 items were considered as indicators of 3 latent factors deduced from the theoretical model for SSE, and 22 items were considered as indicators of 2 latent factors for TSR. The correlation matrix containing polychoric correlation coefficients were used. Since the chi-square test statistic is sensitive to sample size, we used several goodness-of-fit indices to evaluate the fit of the model to data (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). A Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) lower than 0.06 would correspond to a good fit, while values between 0.08 and 0.10 indicate a reasonable to mediocre fit (Byrne, Citation2010). A Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) below 0.08 is recommended. For the comparative fit index (CFI), a value > 0.90 was originally considered representative of a well-fitting model (Bentler, Citation1992; Byrne, Citation2010), however a revised cut-off value close to 0.95 has been later advised, and the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) should preferably be higher than 0.90 (Byrne, Citation2010; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

As initial models for the CFA we used the three-factor model of SSE and the two-factor model of TSR that originate from the two American instruments. The analysis of these models revealed weak figures in all used goodness-of-fit indices (see models a and e, in , below). This result demanded a closer, less prejudiced, exploration of the correlation matrices. Hence, we adopted an explorative approach in the next steps of analysis. The interrelatedness among the 20 variables of the SSE part and the 22 variables of the TSR part were examined through reviewing the correlation coefficients (see Appendices) and in EFA. Observations of significance are presented next.

Table 3. Confirmatory factor analyses. Fit indexes for 8 models, and multigroup comparisions.

In the SSE-part, the item A8 I can arrange a place to study without distractions showed significantly lower correlation to all other variables in the intended self-efficacy for self-regulated learning subscale (SSE1). This item was incoherent and difficult to interpret in the matrix as a whole. We decided to exclude A8 in later analyses. Another item that diverged in the SSE1 was A3, I can always concentrate during class. However, it showed somewhat good correlations to some of the other items of the subscale; it showed substantially higher correlations to two items of the global academic self-efficacy subscale (SSE3). This finding was interesting and suggests that attention and ability to concentrate during class rely on more complex exploratory bases than just self-regulative individual constructs. In the partial matrix of the social self-efficacy subscale (SSE2), a possible fourth latent factor emerged: Three items, A10, A11 and A12, showed strong internal interrelatedness, but only moderate correlation with the other intended variables of the scale. As compared to the others, these items express different aspects of what Bandura et al. (Citation2001) referred to as self-assertiveness, rather than social skills in peer interaction. The global academic self-efficacy subscale (SSE3) finally, seemed to be sustainable with high internal correlations between the variables, although slightly lower for item A20.

In the TSR part of the matrix, the conflict subscale (TSR2) looked solid with consistently high internal correlations among the variables, with one exception. The association between items B8 and B13 was moderately strong as compared to other correlations. The item B13 stood out a bit in general, showing the weakest correlation with four out of five of the other items in the scale, and we decided to exclude it. The support subscale (TSR1) was largely supported by the matrix, but again with one exception. The item B20, How strong are your teacher’s feelings of affection, such as liking, admiring or loving, for you?, showed weak correlations with six of the other 15 subscale-variables. Furthermore, the B20 was subject for questioning among students during the response procedure, as several reacted to the wordings with the word “loving” (älska in Swedish), that some youth thought was strange, irrelevant or even filthy in the teacher–student context. Given such differences in student interpretations, and perhaps also due to difficulties in understanding what is being asked, this question risks receiving inconsistent and less reliable answers. We decided to exclude B20 from subsequent analyses. Another finding in the TSR1 was considered. Three items showed weaker correlations to several of the other subscale items, but at the same time were highly correlated to one another. These three items, B3, B10 and B18, have similar content and concern students’ convenience to disclose things that are more personal with their teachers. Not surprisingly, they all derive from the intimacy dimension of the original instrument (Furman & Buhrmester, Citation1985; Hughes, Citation2011). This possibly third latent TSR-factor also emerged in the EFA. The issue of whether it is proper to include intimacy as a third latent factor in the TSR-part was actualised.

To sum up, the exploratory investigation resulted in:

(i) Variables reduction: item A8 in the SSE part, and items B13 and B20 in the TSR part, were suggested to be excluded in the subsequent model testing.

(ii) A hypothesis that item A3 (concerning students’ self-efficacy in the ability to concentrate during class) would better fit the model as belonging to the SSE3 subscale, rather than to the intended SSE1.

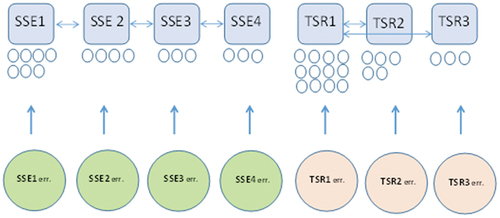

(iii) Ushering two new latent factors, one in each part of the survey, were assumed to improve the models: In the SSE-model, items A10-A11-A12 were preliminary labelled as new indicators for students’ self-efficacy of self-assertiveness (SSE4). In the TSR-model, the earlier extracted dimension of intimacy emerged in items B3-B10-B18 (TSR3).

Through this, the objectives for model re-specification were set. First to explore variable reduction and the move of item A3 from SSE1 to SSE3, and second to explore alternative models with 4 dimensions of SSE and 3 dimensions of TSR.

Model re-specification

To confirm the relevance of continuous actions in order to find the best fitting models, we conducted a series of CFAs (models b-c-d and f-g-h, in ). We continuously applied all suggested modifications, and received subsequently better fit for the data, under developed conditions.

In the SSE-part, the three proposed changes (exclude A8, inset of a fourth dimension, move A3) continuously improved the model, but still with unsatisfying indexes (models b-c). We then explored the new correlation matrix and found A20 to correlate weakly with the moved item A3 in the revised SSE3-scale. In addition, the contents of A20 may be unclear to middle-school students for whom understanding of future “learning objectives in 9th grade” may be limited. Item A16 also stood out as relating weaker to all other items within the revised SSE2-scale. We decided to exclude A20 and A16 and ended the SSE-part of the analyses in model d, with substantially better, but still not fully acceptable goodness-of-fit indices (, bold indexes).

In the TSR-part, all tested three-factor models clearly outperformed the baseline two-factor model. A model with 3 factors and all 22 items remaining, showed substantially increased but still dissatisfying indexes (model g). Then B13 and B20 were excluded from the analysis, resulting in further improvement (model h). Nevertheless, the remaining high error coefficient (RMSEA>0.06) and the insufficient GFI estimate (below 0.90) require further model restructuring.

Hereby we ended with two models to represent the full survey, one with four sub-factors of SSE and one with three sub-factors of TSR. The SSE-model shows all-over stronger goodness-of-fit indices, however still not fully acceptable. The TSR-model shows even more unsatisfying indices. Thus, further remodelling is needed. In the SSE-part, a multigroup comparison displays worse fit for any subgroup (girls/boys, middle-school/secondary school) as compared to the full sample. However, data from boys/girls and middle-school/secondary-school students fit the SSE-model to similar extents, which somewhat supports multi-group invariance of the measure. Contrary, in the TSR-part, multigroup comparison displayed gender and school-grade differences. Girls data differed significantly more from the full sample than did boys data. Data from middle-school students fitted substantially better to the TSR-model than the data from secondary-school students (actually, better than data of full sample). These differences may be random due to small sample sizes. However, the possibility that boys and girls apprehend the presented items concerning relationship quality differently cannot be excluded. And younger students may appreciate their relationships to teachers as more idealistic, obvious and predictive as compared to secondary-school students who may appreciate more complex and varied TSR-qualities. Furthermore, boys scored lower than girls on TSR in this investigation, which is in accordance with research (Hughes, Citation2011; Roorda & Koomen, Citation2011), as is the fact that secondary-school students scored lower on self-efficacy than did middle-school students (Usher & Pajares, Citation2008).

Internal consistency and intra-correlations of the restructured models

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to investigate internal reliability of the seven extracted subscales. The results were satisfying, with good to excellent alphas; 0.75–0.94 (see ). The highest alphas appeared for subscales containing the most items. This was in line with former results (Fertman & Primach, Citation2009; Hughes & Kwok, Citation2007) and concordant with statistical expectations (Bandura, Citation2005). Finally, means and standard deviations () and inter-correlations () between all seven subscales were calculated. An important finding is the substantial cross-associations between TSR1 and subscales of SSE, and of interest is the finding that TSR3 shows negligible association with TSR2.

Table 4. Mean, standard deviation and Cronbachs´ α for the seven extracted subscales of the TSR-SSE survey.

Table 5. Correlations between the seven extracted subscales of the TSR-SSE survey.

Discussion

The first aim of the article was to describe the development process of a tool that measures students’ perceptions of both TSR-quality and SSE, which resulted in the presented Swedish TSR-SSE Survey. The first data collected with the new survey showed it to be manageable and understandable for Swedish students aged 9–15. The cultural transition seems to have been smooth. Only a few questioning reactions from students were obtained, and students’ responses were to a large extent individually cohesive, which indicate that the adopted items were well applicable in the present Scandinavian school context. We conclude, that due to the global theories that underpin the contents (relational theory and social cognitive theory) most items despite their American origins address interpersonal teacher–student relationships in ways consistent with Swedish students’ experiences (e.g. equality values and informal codes of conduct between adults and children), and concern relevant aspects for Swedish students’ sense of school agency as well. However, some items emerged as less well matched to Swedish students’ comprehension or showed to be less reliable, and thus they were excluded. In summary, the findings so far support future use of the proposed instruments in Swedish/Scandinavian school contexts.

The second aim was to validate the two instruments and to explore their factor structures. Based on the original American instruments, the hypothesised TSR and SSE models aimed to cover three dimensions of SSE and two dimensions of TSR, as illustrated in .Footnote2

However, in our first analysis it was obvious that the adopted models were insufficient to match the responses from Swedish students. Through exploratory investigation and further CFA, we identified two models that better fitted the data, together shaping 7 dimensions: 4 of SSE and 3 of TSR, as illustrated in .

In the modified models, five original items have been excluded. The variable reduction was motivated due to certain patterns observed among intra-scale correlations. The instrument contains many variables, thus variable reduction was desirable to increase its usability. In addition, a better balance in subscale sizes may contribute to a better fit of the model. On the other hand, individual subscales holding few variables (≤ 3) may as well weaken the model (Singh, Junnarkar, & Kaur, Citation2016). In our case, there is an unbalance that especially appears in the TSR-part. TSR1 is incomparably the largest subscale. Furthermore, TSR1 contains several items that pairwise might look very similar. As an example, the wording How much does your teacher like you? May be perceived as being very similar to the wording How much does your teacher actually care for you? Teachers’ “liking” is plausibly perceived as very close, or synonymous, to teachers “caring-for”, by many students. Nevertheless, some students may refer to teacher care independently of personal affection. Such differences in students’ interpretations of “seemingly look-alikes” may confound measurement validity and contribute to weak model-fit. We suggest for future adjustments to consider such pairwise item similarities. Exclusion of one, or more, look-alikes, will render better inter-scale balance and decrease risk for confounding differences in students’ interpretations of wordings.

Interestingly, the two new latent factors SSE4 and TSR3 seem to have something in common. Both express something about individual students’ confidence in being self-assertive or convenient being open with things that are more personal in relationships with peers (SSE) and teachers (TSR). These factors seem to be of a complex nature. Students’ perceptions of them vary a lot, with significantly higher standard deviations in scorings () compared to other factors. Little is known about the implications of self-assertive and self-disclosing aspects of relationships for students’ learning and achievement. For example, researchers have reported intimacy- and dependency-scales to be less stable and difficult to interpret and disregarded them in analyses (Baker, Citation2006; Wu et al., Citation2010). In our data, students’ intimacy-scores stand out also as being uncorrelated to conflict-scores but correlated to support-scores (). Disclosing personal thoughts and feelings with one’s most important teacher here seem to be one characteristic of a supportive TSR, but on the other hand, it does not predict students’ appreciation of conflict in that relationship. In contrast, students’ self-efficacy for self-assertiveness versus peers (SSE4) correlates with all other self-efficacy scales, and as expected, more with social- and global self-efficacy aspects than self-regulatory learning aspects. These findings are interesting but so far somewhat speculative. It motivates deeper investigation of the two constructs. In further studies, the subscales should be tested for concurrent validity in relationship to other existing measures of e.g. teacher–student interaction, social support and social skills.

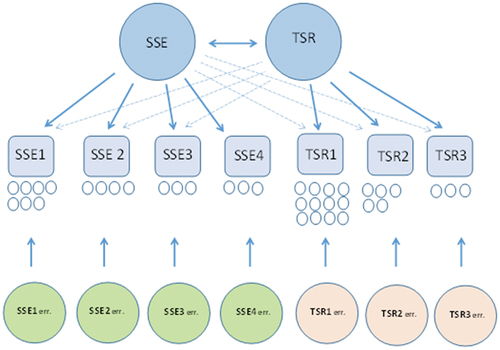

Prospecting further model development, the inter-correlations between the seven subscales are of significance. confirms theoretical assumptions (Bandura, Citation1989; Hamre & Pianta, Citation2006; Hughes et al., Citation2012) and earlier reports of reciprocal cross-mediations of TSR and SSE (Hughes, Citation2011; Martin & Rimm-Kauffman, Citation2015), in that most subscales correlate with one or more subscale of “the other” construct. For instance, teacher-support (TSR1) shows noteworthy strong associations to students’ self-efficacy for self-regulative learning (SSE1) and global school success (SSE3). The only exceptions from the pattern of cross-association are SSE2 and SSE4 which both deal with peer relationships, which show no correlation with student-perceived conflict in teacher–student relationships (TSR2). Based on theory, and our empirical results with cross-associations between significant sub-factors of TSR and SSE, we would explore in the future a correlated second-order model, as suggested in :

In this hypothetical model, the compiled scores of the respective SSE-subscales and TSR-subscales constitute two higher-order factors: SSEtotal and TSRtotal, which are assumed to be inter-correlated. The solid arrows in the illustration represent well-founded assumed connections, whereas dashed arrows represent assumed, but hitherto unexplored, construct-crossing connections. The second-order model further provides an accessible merged measure of “TSR+SSE” of interest for future theoretical consideration: the product of students’ perceptions of the teacher–student relationship quality and their self-efficacy beliefs represent an expanded insight into students’ experiences that encompasses both relational and individual aspects of education, and, thus may capture students’ trust in own schooling in a wide sense.

Conclusions and limitations

The present TSR-SSE survey relies on solid theoretical foundations. All dimensions of the American instruments were re-extracted as latent factors in the Swedish instruments, despite translation, adaption and use in a different school context. Moreover, neither of the added latent factors are surprises, since both can be traced in the original instruments.

However, the obtained results should be interpreted with a caution. Although, each of the subscales show good to excellent internal reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.75–0.94), the suggested model structures for SSE and TSR currently do not hold at the acceptable level. Further, since the multigroup comparisons were not satisfactory, gender and grade level differences in students’ understanding and valuing TSR-items need further investigation.

The unsatisfying model fit could be due to several factors, for example too small sample size, unbalanced data, and possibly, confounding differences in students’ interpretation of pairwise look-alikes. To make the Swedish versions of the instruments become adequate for use, either more sophisticated models using multilevel confirmatory factor analysis could be tried to capture a complex structure of SSE and TSR in a Swedish context, or larger empirical study should be conducted, or both. Another option is to explore a bi-dimensional model of TSR in which the TSR3 subscale either is excluded or its items are included within the TSR1, this could be in line with earlier strategies (see Hughes & Kwok, Citation2007).

The present TSR-SSE survey possesses seven internally reliable sub-scales that together, or selected, can be used for further exploration of the interrelatedness between student-perceived TSR and SSE, and/or the relationship between TSR, SSE and a range of other school-factors (attainment, mental health, etc.). In longitudinal use, these scales can be utilised in monitoring school development processes by means of students’ perceptions of relational aspects of education. The parallel design enables cohesive and efficient administration, and simultaneously obtained data provides a precise comparison and reliable investigation of associations at the individual student level.

The overall interrelatedness between TSR and SSE and its relationship to students’ wellbeing and learning are challenging targets for research. A hypothetical merged construct – that encompasses students’ sense of trust in school in a wider sense – may serve as a global indicator in multifactor studies of relational quality of education. The latter, first demands deeper theoretical consideration and further modelling based on statistical inquiry in larger data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ulf Jederlund

Ulf Jederlund is a teacher educator, school supervisor and authorised psychotherapist, working at the Department of Special Education, at Stockholm University. His research focuses on “Relational School Development”: how improved teacher collaboration and collective learning processes among school staff can support the development of trustful teacher–student relationships, that promote student’s self-believes, well-being and learning.

Tatjana von Rosen

Tatjana von Rosen is a senior lecturer, assistant professor and researcher at the Department of Statistics, at Stockholm University. Her research focuses statistical multilevel models with applications for educational and social sciences, model diagnostics, modelling of different types of dependences, and developing testing procedures.

Notes

1. The search was performed in January 2013, but to our knowledge no such instrument as of yet exists.

2. The theoretically assumed correlation between TSR and SSE was ignored in the initial model testing.

References

- Allodi Westling, M. (2013). Simple-minded accountability measures create failure schools in disadvantaged contexts: A case study of a Swedish junior high school. Policy Futures in Education, 11(4), 331–363.

- Ashan, S., & Smith, W. C. (2016). Facilitating student learning: A comparison of classroom and accountability assessment. In W. C. Smith (Ed.), The global testing culture. Shaping education policy, perceptions, and practice (pp. 131–151). Providence, Rhpde Island: Symposium Books.

- Au, W. (2007). High-stakes testing and curricular control. A qualitative metasynthesis. Educational Researcher, 36(5), 258–267.

- Baker, J. A. (2006). Contributions of teacher–child relationships to positive school adjustment during elementary school. Journal of School Psychology, 44(3), 211–229.

- Bandura, A. (1989). Social cognitive theory. In R. Vasta (Ed.), Six theories of child development (pp. 1–60). Greenwich: JAI Press.

- Bandura, A. (1990). Multidimensional scales of perceived self-efficacy. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

- Bandura, A. (2005). Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-efficacy beliefs of Adolescents (pp. 305–337). Charlotte, North Carolina.

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Multifaceted impact of self-efficacy beliefs on academic functioning. Child Development, 67(3), 1206–1222.

- Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (2001). Self-efficacy beliefs as shapers of children´s aspirations and career trajectories. Child Development, 72(1), 187–206.

- Bentler, P. M. (1992). On the fit of models to covariances and methodology to the Bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 112(3), 400–404.

- Biesta, G. (2004). Mind the gap. In C. Bingham & A. M. Sidorkin (Eds.), No education without relation (pp. 11–22). New York: Peter Lang Publisher.

- Biesta, G. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy (1st ed.). Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London: Routledge.

- Braun, A. (2017). Education policy and the intensification of teachers’ work: The changing professional culture of teaching in England and implications for social justice. In S. Parker, K. N. Gulson, & T. Gale (Eds.), Policy and inequality in education (pp. 169–185). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research. Newbury Park, California: Sage.

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS. Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

- Choi, N., Fuqua, D. R., & Griffin, B. W. (2001). Exploratory analysis of the structure of scores from the multidimensional scales of perceived self-efficacy. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(3), 475–489.

- de Vijver, F. J., & Hambleton, R. K. (1996). Translating tests: Some practical guidelines. European Psychologist, 1(2), 89–99.

- Dhamani, K., & Richter, M. (2011). Translation of research instruments: Research processes, pitfalls and challenges. Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 13(1), 3–13.

- Drugli, M. B., & Hjemdal, O. (2013). Factor structure of the student–teacher relationship scale for Norwegian school-age children explored with confirmatory factor analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 57(5), 457–466.

- Fertman, C. I., & Primack, B. A. (2009). Elementary student self-efficacy scale. Development and validation focused on student learning, peer relations, and resisting drug use. Journal of Drug Education, 39(1), 23–38.

- Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1985). Children’s perceptions of the personal relationships in their social networks. Developmental Psychology, 21(6), 1016–1024.

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2006). Student-teacher relationships. In Bear & Minke (Eds.), Children´s needs III: Development, prevention and intervention (pp. 49–59). Washington DC: National Association of School Psychologists.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning – a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

- Hughes, J. N. (2011). Longitudinal effects of teacher and student perceptions of teacher-student relationship qualities on academic adjustment. Elementary School Journal, 112(1), 38–60.

- Hughes, J., & Kwok, O. (2007). Influence of student-teacher and parent-teacher relationships on lower achieving readers’ engagement and achievement in the primary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 39–51.

- Hughes, J. N., Wu, J.-Y., Kwok, O.-M., Villarreal, V., & Johnson, A. Y. (2012). Indirect effects of child reports of teacher-student relationship on achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(2), 350–365.

- Klassen, R. M. (2010). Confidence to manage learning: The self-efficacy for self-regulated learning of early adolescents with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 33(1), 19–30.

- Koomen, H., & Jellesma, F. (2015). Can closeness, conflict, and dependency be used to characterize students’ perceptions of the affective relationship with their teacher? Testing a new child measure in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 479–497.

- Li, Y., Hughes, J. N., Kwok, O., & Hsu, H.-Y. (2012). Evidence of convergent and discriminant validity of child, teacher, and peer reports of teacher–student support. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 54–65.

- Majbar, M. A. (2019). Validation of the French translation of the Dutch residency educational climate test. BMC Medical Education, 2020(20), 338.

- Martin, D. P., & Rimm-Kauffman, S. E. (2015). Do student self-efficacy and teacher-student interaction quality contribute to emotional and social engagement in fifth grade math? Journal of School Psychology, 53, 359–373.

- Murray, C., Waas, G. A., & Murray, K. M. (2008). Child race and gender as moderators of the association between teacher–child relationships and school adjustment. Psychology in the Schools, 45(6), 562–578.

- O’Connor, E. E., Dearing, E., & Collins, B. A. (2011). Teacher-child relationship and behavior problem trajectories in elementary school. American Educational Research Journal, 48(1), 120–162.

- Patricio, J. N., Barata, M. C., Calheiros, M. M., & Graca, J. (2015). A Portuguese version of the student-teacher relationship scale - short form. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 18(30), 1–12.

- Pianta, R. C., & Nimetz, S. L. (1991). Relationships between children and teachers: Associations with home and classroom behavior. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 12(3), 379–393.

- Roorda, D. L., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2011). The influence of affective teacher–student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach, 37. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529.

- Singh, K., Junnarkar, M., & Kaur, J. (2016). Measures of positive psygohology. development and validation. New Delhi: Springer India.

- Telli, S., & den Brok, P. (2012). Teacher-student interpersonal behaviour in the Turkish primary to higher education context. In D. B. Wubbels, van Tartwijk, & Levy (Eds.), Interpersonal relationships in education. An overview of contemporary research (pp. 187–206). Sense Publisher: Rotterdam.

- Ubha, N., & Cahill, S. (2014). Building secure attachments for primary school children: A mixed methods study. Educational Psychology in Practice, 30(3), 272–292.

- Usher, L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Self-efficacy for self-regulated learning. A validation study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68(3), 443–463.

- Washington University (2012). Research measures of social work. George Warren Brown school of social work. Downloaded 201212. Washington University. St. Louis.

- Weiss, R. (1974). The provisions of social relationships. In Z. Rubin (Ed.), Doing unto others (pp. 17–26). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Wentzel, K. R. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and adolescent competence at school. In T. Wubbels, P. den Brok, J. van Tartwijk, & J. Levy (Eds.), Interpersonal Relationships in Education (pp. 19–36). Rotterdam: Sense.

- Wesson, C. J., & Derrer-Rendall, N. (2011). Self-beliefs and student goal achievement. Psychology Teaching Review, 17(1), 3–12.

- Wu, J., Hughes, J. N., & Kwok, O. (2010). Teacher-student relationship quality type in elementary grades: Effects on trajectories for achievement and engagement. Journal of School Psychology, 48(5), 357–387.

- Zimmerman, B. J., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29(3), 663–676.

- Zuffianò, A., Alessandri, G., Gerbino, M., Luengo Kanacri, B., Di Giunta, L., Milioni, M., & Caprara, G. (2013). Academic achievement: The unique contribution of self-efficacy beliefs in self-regulated learning beyond intelligence, personality traits, and self-esteem. Learning and Individual Differences, 23, 158–162.

Appendix

Table A. Zero-order polychoric correlations for student self-Efficacy items, displayed in hypothesised subscales: SSE1-SSE2-SSE3.

Table B. Zero-order polychoric correlations for teacher–student relationship items, displayed in hypothesised subscales: TSR2-TSR1.