ABSTRACT

Due to COVID-19, schools closed in Finland for eight weeks in the spring of 2020, and teaching was conducted using distance education. Teachers used their professional agency to ensure a continuation of their students’ learning. This study focuses on the experiences of teachers who taught pupils with intellectual disabilities during the distance education period. The research question is: What kind of experiences did the teachers have with distance education? The data were collected via an electronic questionnaire and analysed using qualitative content analysis. The results were examined using teachers’ professional agency as a theoretical lens. The results showed that teachers encountered many challenges and emotions at the beginning, but during distance education, they learnt new ways to teach and support pupils and families. Teachers’ agency was spread between supporting the agency of pupils and guardians. These are discussed in the article.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic changed education in many countries, including Finland. Transition to distance education in the spring of 2020 was unprecedented because the Finnish Basic Education Act (628/Citation1998) does not recognise the possibility for distance education in compulsory education. The quickly prepared Emergency Power Act (Parliament of Finland, Citation2020) allowed schools the transition to distance education due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it granted pupils from grades 1‒3 and pupils who needed special support the right to study at school if permitted by their guardians. Otherwise, teaching was organised as distance education for all pupils (Parliament of Finland, Citation2020). Numerous pupils with intellectual disabilities (ID) studied at home. Schools all over were closed, and teaching was conducted through distance education for several weeks in the spring of 2020 (Aditya, Citation2021; Judge, Citation2021).

Even in exceptional circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, schooling and studying are essential for children and young people, as they contribute to maintaining a safe and stable daily life. According to a report from Unicef (Citation2020), many children were at risk of falling behind due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, distance education does not mean homeschooling; here, the teacher, not the guardians, primarily handles education following the curricula (Heinonen, Citation2020). However, Downes (Citation2013), in his study of Australian distance education, noted that the guardian’s role in distance education is crucial.

In an unprecedented situation, schools had to find ways to serve pupils academically, socially and emotionally from a distance (Kier & Clark, Citation2020). Teaching and contacts with pupils and guardians had to occur in a new way, primarily using information and communication technologies. We were interested in how the teachers taught when the “routines broke down”, and we set the research question: What kind of experiences did teachers have with distance education? With this research, we intend to highlight teachers’ experiences and provide some guidelines for possible future distance education situations. In order to do this, we will use the concept of professional agency. Hitlin and Elder (Citation2007, p. 176) describe agency in many ways but also as the “ability to innovate when routines break down”. It is therefore very appropriate in the COVID-19 situation.

Many pupils with ID need extra support for learning, which may cause special challenges for pupils, guardians and teachers. Due to the sudden closure of schools, pupils lost direct social interaction with their peers, and guardians faced several demands when supporting their children’s education (Bhamani et al., Citation2020). The teachers also faced new challenges.

Education of pupils with intellectual disabilities in Finland

Pupils with ID could have significant limitations in intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour, such as everyday social and practical skills (AAIDD, Citation2020). IDs is often divided into four levels (mild, moderate, severe and profound), depending on intellectual and adaptive functioning and intensity of support needs. Pupils with mild disability often need intermittent assistance, while pupils with a profound disability may need frequent support (Patel, Greydanus, & Merrick, Citation2014). Because of various needs, the individualisation of teaching is the basis for educating pupils with ID in Finland as well as internationally (Patel et al., Citation2014; Räty, Vehkakoski, & Pirttimaa, Citation2019).

In Finland, pupils with ID can have a decision of special support, 11-year compulsory education and individualised learning goals (Finnish Basic Education Decree, 628/Citation1998). A three-tiered support model is used in Finnish schools – general, intensified and special support – as determined by the Finnish National Agency for Education (Citation2016). Diverse pupils receive special support (Kokko et al., Citation2013). Hence, the individual education plan (IEP) is an essential document in special education (Räty et al., Citation2019). It includes the aims, contents, teaching arrangements, pedagogical methods, and support and guidance needed for a pupil (Finnish National Agency for Education, Citation2016; Kokko et al., Citation2013). The rehabilitation aspect is also closely related to the teaching of pupils with ID. The goals include improving the interaction between the pupil and the environment and supporting the pupil in living independently in the future. These goals have been reconciled with the pupil’s individual aims (Koivikko & Autti-Rämö, Citation2006). The education of pupils with severe ID is organised using the activity area-based curriculum model instead of the content-area subject model (e.g. science, maths, etc.). Pupils’ individual aims guide their education. Sometimes these pupils can also study different subjects like mathematics, mother tongue or physical education, but the goals are individually designed. (Pirttimaa, Räty, Kokko, & Kontu, Citation2015)

Pupils with ID can study in a general education class, special education class or at special schools. School place depends on communities’ practices and guardian’s decision. However, Finland has a commitment to provide inclusive education and support the education of pupils with ID in neighbourhood schools (Finnish National Agency for Education, Citation2016). A special class with pupils having moderate or severe ID may not have more than eight pupils. The group size must be less than six when it comprises pupils with profound ID. If a pupil with ID is placed in a general education class, the group size should not exceed 20 pupils (Finnish Basic Education Degree, 628/Citation1998). These regulations try to ensure adequate learning support. Nevertheless, inclusion has not been widely used with ID pupils in Finland (Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, Citation2014).

Teachers’ professional agency and teachers’ digital competencies

Working as an expert frequently includes an agency (Hallamaa, Citation2018). The agency is not something that people have or possess but something that is achieved and done (Biesta & Tedder, Citation2007). The agency is realised through an interplay of individual capacity and social and material conditions (Priestley, Biesta, Philippou, & Robinson, Citation2015a; Priestley, Biesta, & Robinson, Citation2015b). Teachers are highly educated in Finland; thus, they are autonomous with their professional agency (Sahlberg, Citation2013) within the limits of current regulations and laws. Also, many contextual issues, such as class size or available materials, affect agency (Biesta, Priestley, & Robinson, Citation2015a). At best, there is a clear connection between agency and professional development (Philpott & Oates, Citation2017). Professional agency involves creative work practices and innovative work behaviours (Priestley et al., Citation2015a; Vähäsantanen et al., Citation2019), which are needed when schools suddenly move to distance education.

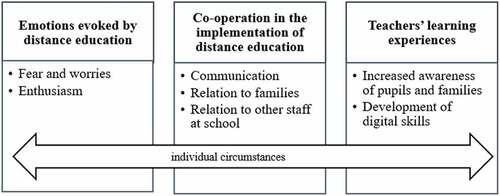

The concept of professional agency is multidimensional and can be viewed from various theoreticalCitation2019 frameworks (Clandinin & Husu, Citation2017; Eteläpelto, Vähäsantanen, Hökkä, & Paloniemi, Citation2014; Priestley et al., Citation2015a). In this study, we consider agency through Priestley et al.’s (Citation2015a, Citation2015b) ecological model ().

Figure 1. Modified ecological model of agency by Priestley et al. (Citation2015a, p. 4)

Originally these three areas were presented by Emirbayer and Mische in 1998, when they suggested that the achievement of agency needs to be understood as a configuration of influences from the past, orientations towards the future and engagement with the present. They named the dimensions of agency as the iterational, the projective and the practical-evaluative dimension. They spoke of a “chordal triad of agency within which all three dimensions resonate as separate but not always harmonious tones” (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998, p. 972). The model highlights that the agency is informed by past experiences, both professional and personal experience. The model also emphasises that the achievement of agency is always orientated towards the future with a combination of short term and long-term objectives and values. In addition, agency is enacted in a concrete situation, therefore both being constrained and supported by cultural, structural and material resources available to actors (Priestley, Biesta & Robinson, Citation2015b).

The iterational part involves the personal and professional past of the teacher. The iterational aspects include personal capacity, personal and professional beliefs and values. (Priestley et al., Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Teachers having more of experience might be expected to be able to develop more expansive orientations to the future and draw upon a greater range of responses to the challenges of the present context, than their less experienced colleagues (Priestley et al., Citation2015b). The projective part contains forward-looking, short- and long-term plans, which are always based on the teacher’s prior experiences. Also here, the long experience is supposed to give the teacher more repertoire and possibilities (Priestley et al., Citation2015b). The practical-evaluative part contains the missing present and important cultural, structural and material aspects, such as political principles, the curriculum and situational factors. Although agency is involved with the past and the future, it can only ever be “acted out” in the present. (Priestley et al., Citation2015b)

Agency is not a static concept but develops over time (Ehren, Romiti, Armstrong, Fisher, & McWhorter, Citation2021). Priestley et al. (Citation2015a, Citation2015b) defined agency as a temporally embedded process. Teachers’ agency is also highly relational and embedded in professional interactions between other teachers, pupils and other people who are connected to the school (Imants & Van der Wal, Citation2019; Pyhältö, Pietarinen, & Soini, Citation2014). Agency also involves power, and power relationships are an essential part of teachers’ agency (Eteläpelto et al., Citation2014). Teachers’ power appears in teacher’s autonomy, and autonomy can be described as teachers’ ability to act independently, also when changes occur (Molla & Nolan, Citation2020).

Teachers can be seen as school developers and an important part of the schools’ change process (Pyhältö et al., Citation2015). Thus, teachers are often called agents of change (Imants & Van der Wal, Citation2019; Pantić, Citation2015; Priestley et al., Citation2015a). During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers worked as active agents to promote their students’ learning. Nevertheless, the changes in education implementation have also tested personal capacities and individual and collective agency (Ehren et al., Citation2021).

Teachers’ digital competencies can be seen as one of the necessary 21st century skills (Kuusimäki, Uusitalo-Malmivaara, & Tirri, Citation2019; Siddiq & Scherer, Citation2016; van Laar, van Deursen, van Dijk, & de Haan, Citation2017). Finnish teachers’ digital skills have been the subject of strong development since 2016, when the new Finnish National Core Curriculum of Basic Education was introduced (Tanhua-Piiroinen, Kaarakainen, Kaarakainen, & Viteli, Citation2020). The National Core Curriculum (Finnish National Agency for Education, Citation2016) sets goals for the teaching of information and communication technologies.

Teachers had perhaps not been actively involved in using digital tools; now they had to and, in the future, teachers have skills to continue using digital devices and tools. The aim of the Report of Comprehensive Schools in the Digital Age II was to create a foundation for the use of up-to-date research data on the education sector in central government decision-making (Tanhua-Piiroinen et al., Citation2020). The report showed that, in Finland, teachers’ digital skills depend on the teacher’s personal interests. The trust in one’s digital skills significantly increases with a teacher’s willingness to use digital technology as part of teaching (Tanhua-Piiroinen et al., Citation2020). It has been shown that the use of digital learning requires self-efficacy from the teacher and organisational support (Börnert-Ringleb, Casale, & Hillenbrand, Citation2021).

Materials and methods

The data were collected via an electronic questionnaire from teachers of pupils with ID. The questionnaire was open for eight weeks during the distance education period. It included 12 quantitative and 17 qualitative questions. We used ten quantitative background questions to determine gender, work experience, school level, professional title, the composition of the group of pupils to be taught and things related to the implementation of distance education, such as equipment provided by the employer. The open-ended questions were used to gain a representative of teachers’ experience and voice. Often, one response addressed issues more broadly than the question required. We used the following six open-ended questions:

What were your first thoughts when distance education began?

How did you practically implement distance education for pupils with IDs?

How and how much do you connect with your pupils and their guardians during distance education?

What new things have you learnt about your pupils during distance teaching?

What new things have you learnt about yourself during distance teaching?

What are your current views on distance education for pupils with IDs?

The link to the questionnaire was shared on social media (Facebook and Twitter); it was also sent to some teachers who were familiar with the first author of the study. In the cover letter, there was a request to re-share the questionnaire link for special education teachers to utilise the snowball effect (Noy, Citation2008; Saaranen-Kauppinen & Puusniekka, Citation2006). Altogether, 96 female special education teachers responded, with most of the participants working in primary schools. The teachers worked in various class compositions, but the majority worked exclusively with pupils with ID (). One of the respondents omitted her school, level of education or years of experience.

Table 1. Participants’ workplace and class composition

Thirty-six participants worked in special education schools and 60 in regular schools. Teachers’ years of experience varied: 45 teachers had taught less than ten years, and 36 teachers had taught 10‒20 years. Fifteen teachers had taught for more than 20 years. All teachers taught pupils with ID, and the degree of this disability varied from mild to profound.

During distance teaching, the location of teaching changed for some teachers. Some taught some days from home and some days at school. About half of the teachers (n = 35) used the “hybrid model” of teaching, where some pupils were in school, and others were studying at home. Some teachers could have two days in distance education and three at school. These changes influenced class composition; pupils studying at school were from different classes and not familiar with each other. This meant that the teachers’ work situation and workload varied. About half of the teachers (n = 37) worked only in distance education.

During the distance education period, 63 teachers had access to a school assistant to promote their pupils learning. Some school assistants worked at school with pupils who were studying at school, and some worked in both forms: distance and at school, while some were laid off.

Method

In this qualitative study, we used qualitative content analysis to provide knowledge and understanding of the phenomenon under study, which helped to create core categories and subcategories (Schreier, Citation2012). We used an inductive approach, including open coding, creating categories and abstraction (Elo et al., Citation2014). Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005) called this conventional content analysis, which is an appropriate method when research literature on a phenomenon is limited, such as education during a pandemic situation.

First, the researchers read the data independently and repeatedly to effectively visualise the material. In the second phase, the researchers read the material to identify themes in it. The themes described key thoughts that arose from the text when reading it. In the third phase, the researchers made a preliminary analysis independently by comparing the codes and identifying the overlaps. Hence, coherent and independent codes were induced. This analysis was then discussed together, and the researchers challenged each other’s interpretations. In the fourth phase, the researchers created the main categories from the subcategories in the data. The researchers also identified relationships among the categories. In the fifth phase, the content of the categories identified in the data was compressed. Consequently, three main categories, seven subcategories and one cross-cutting category were established.

After identifying the main and subcategories, we observed how the concept of professional agency was present in these categories and how it reflected teachers’ experiences. In this phase, our coding frame (Schreier, Citation2012) comprised teachers’ agency, including past, present and future experiences forming current agency (Priestley et al., Citation2015b).

According to Elo et al. (Citation2014), the content analysis should be based on self-critical thinking in each phase of analysis. The first researcher worked as a special education teacher during the distance education period and gained personal experience with the topic. However, this was considered and unknowingly allowed to influence the analysis of the data.

Results

Teachers’ distance education experiences can be divided into three different main categories: emotions evoked by distance education, co-operation in implementing distance education and teachers’ learning experiences. These three categories included several subcategories. One cross-cutting, intertwined category was also found, called individuality (). The individuality category included individual encounters with the situations of both pupils and families during distance education. They also had unique individual learning experiences during distance education and individual possibilities to meet the challenges in teaching. Next, we discuss the content of each category. We also remind that Finnish teachers are independent actors and have a full professional agency. How it was used in this new situation will also be observed.

Emotions evoked by distance education

The category of emotions contained two subcategories, which can also be seen at different ends of a continuum: fear including worries, and enthusiasm.

Fear and worries

The fear and worries subcategory included teacher’s concerns and confusion about how distance education could be realised and how it affected the equality of pupils. As one teacher said, “At first, there was confusion about how distance education could be implemented with pupils having individual aims” (primary school teacher with over 10 years of experience). The teachers’ uncertainty about the future and their skills in using distance education was high. This category also encompassed teachers’ criticism of the political decisions that some pupils could come to school during a pandemic: “The fact that special needs pupils are allowed to be in school, even in exceptional situations, is confusing. They have many somatic diseases, and thus, they are people at risk” (secondary school teacher with over 16 years of experience). Teachers were worried about every pupil and about their family members’ health situation. Teachers who had to work at school were also worried about their own health and ability to cope at work.

Teachers were also worried about the well-being of some individual pupils’ families, mainly because many pupils needed so much support for learning and daily life. For some families, the school can be a place where the pupil spends his or her everyday life, and as such, the responsibility for the child is shared between the home and school. For example, one teacher said, “I am concerned about the support to these pupils with special needs, not so much about learning, but the well-being and resilience of [their] families” (primary school teacher with less than five years of experience). Due to the different situations of the guardians, the teachers’ saw that pupils were in an unequal position regarding how much support for studies they received at home. Equality is an essential value in Finnish education (Finnish Basic Education Act 628/Citation1998); some teachers felt that this value was threatened during distance education.

Enthusiasm

The transition to distance education forced teachers to think innovatively about their work, and many teachers found joy in finding new and creative ways of teaching. One teacher described her experience this way: “Now there is as much work, but it is possible to plan and sometimes create something new, to learn new ways of working and new methods; it is very refreshing” (secondary school teacher with more than 10 years of experience). The unique situation forced teachers to consider their work from a different perspective; one teacher said, “I was excited. I thought this work could not be done remotely, but how wrong I was. I had started thinking about assignments and tasks from a new perspective and also thinking about how to implement the teaching” (primary school teacher with over 16 years of experience).

However, this exceptional situation forced and made it possible for teachers to develop their teaching and learn new skills. Each teacher had to decide how to implement education at an exceptional time. The teachers had to act as “an active agents” (Priestley et al., Citation2015a) and teachers were required to adapt themselves to diverse requirements in their work during the distance education. The practical-evaluative part of agency was involved, and although worried, teachers’ self-efficacy promoted acting (also Priestley et al., Citation2015a).

Co-operation in the implementation of distance education

The Finnish National Core Curriculum (Finnish National Agency for Education, Citation2016) obliges teachers to collaborate with families and other staff members. Some teachers described an increase in cooperation with guardians and said that communication had become easier during distance education. This can be seen as a cultural change in working habits with families (Priestley et al., Citation2015b). From the teachers’ viewpoint, changes in everyday life due to COVID-19 seemed hard for many families, and the teachers wanted to ensure family resilience. Reflexivity is part of agency, and it allows teachers to discard previous practices when they are less effective than new ones (Maclellan, Citation2007).

Individual implementation of teaching is a general tool in special education (Räty et al., Citation2019). During distance education, individuality was even more important as a starting point for teaching than usual. The individualisation of teaching was based on the needs of both pupils and families, while under normal circumstances, it was directed by the needs of the pupils. One teacher explained this by saying: “I send the day’s assignments to the guardians via e-mail in the morning. The assignments are functional. I design individual assignments for each pupil. I cannot control if they are done. I ask guardians to send photos or videos of what the pupil has done during the day. I have allowed the guardians to select tasks because I do not know the situation in each home. I do not want to exhaust my guardians”. (primary school teacher with over 16 years of experience)

The next citation reflects a different approach using a strict structure: We all have our own schedules and hours of instruction. “All the material comes from the school, and the schedule is the same because pupils are accustomed to use it in their daily lives. I make video calls twice a week” (primary school teacher with over 20 years of experience). Some teachers thought that a strict daily structure supports the survival of pupils and families in times of distance education

Communication and relation to families

Flexible interaction was needed when teaching and guiding pupils and in communication with diverse guardians. Teachers used various electronic communication methods, like mobile phones with different applications, emails and electronic platforms like Teams or Google Classroom. The type and frequency of interaction with pupils and guardians was chosen based on individual circumstances, mainly according to the pupils’ abilities, family situation and digital devices. However, the digital tools available varied greatly from school to school and home to home, which also affected communication and created inequality between students and teachers.

Some teachers communicated and instructed the guardians using written instructions via email, video made by the teacher or a link to some other video. The guardians responded by email or WhatsApp messages, photos of their child and/or videos for teachers. With these, they conveyed information about what the pupils had been doing at home. If the pupils were skilful, the teachers communicated using online platforms directly with the pupil. However, full-class distance meetings were seldomly used. Usually, the teachers used distance meetings with small groups, especially when teaching new material. Adding to this communication and teaching methods, some teachers or school assistants assembled material packages, and some of them included craft materials, games, paper tasks or individual material for pupils. The guardians either fetched them from the school or the assistant delivered them home.

During distance education, teachers and guardians had to interact frequently as they discussed pupils’ learning needs and how they could be supported. Such discussions were infrequent in normal situations, and meetings with guardians only happened when designing the IEP. Some teachers said that the discussions with pupils’ families “had improved to a new level” (secondary school teacher with over 20 years of experience), and they found common goals for education. Karakaya, Adıgüzel, Üçüncü, Çimen, and Yilmaz (Citation2021) also noticed that the pandemic situation influenced the relationships between the teacher and guardians positively.

Relation to other staff at the school

During the COVID-19 situation, collaboration with other employees, such as teachers, the head of schools or teaching assistants, decreased and changed. Teachers did not meet other staff members at the school; everyone was more or less isolated and avoided physical contacts. Meetings were still held but via some digital tools and that is why they appeared to become shorter. Sometimes it was hard to reach others, even by phone. This induced more independence and loneliness. However, there were big differences between schools in how the collaboration with staff members was organised. Some had more regular meetings, while others seldom met.

Teachers’ learning experiences – Changes in teaching

Almost all the teachers said they had learnt new things during the distance education period. Surprisingly, teachers’ experiences were quite positive even though the transition to distance education was sudden, unexpected and caused worries. Perhaps the most crucial skills needed in this situation were flexibility and tolerance of pressure. Taking care of oneself and coping at work in this new situation were highlighted in the responses.

It was observed that the teachers enjoyed the time to focus on just one pupil at a time and simultaneously learn new things from the pupils. One teacher said: “I enjoy working when I can focus on one pupil only at a time. Sometimes, lessons are just for one pupil, and the teaching is not interrupted by other adults, phone calls, etc”. (primary school teacher with less than 10 years of experience). Also, Mikola (Citation2011) noticed the rush experienced by teachers at school, which seemed to arise from performing countless different work tasks simultaneously. Distance education gave time for the teachers to focus on one thing – teaching.

Increased awareness of pupils and families

The teachers had also learnt much about their pupils and their families and were both positively and negatively surprised by their pupils’ skills when studying at home. Some pupils performed fine at home, and the teachers were amazed that they could be so independent. It seemed that pupils had hidden skills that were unidentified in the school situation. One teacher explained: “Silent pupils succeeded in group meetings. It is easier for an autistic pupil to participate in discussions through video” (primary school teacher with less than 10 years of experience). However, some teachers noticed that several pupils “lost” some skills at home. For example, some digital skills were successfully learnt, but the transition from school to home did not happen.

However, some issues should be given more attention at school than in distance education; as one teacher said, “They have an incredible amount of skills that only come to light when they are ‘on their own’. Some necessary skills should have already been taught and practiced at school” (vocational school teacher with less than 10 years of experience).

Development of digital skills

According to Fu (Citation2013), digital teaching methods require teachers to be creative and adapt their teaching materials and strategies. Besides creativity, many teachers said that their digital skills had improved unnoticed during distance education. The necessity of using different kinds of digital solutions increased teachers’ digital skills, as one teacher highlighted: “I have not been very excited about ICT issues and have doubted my abilities. Now I find that I know and learn without any training. I’m pretty proud!” (primary school teacher with more than 10 years of experience). Tanhua-Piiroinen et al. (Citation2020) found that many teachers had been afraid of using new software and various digital devices before distance education. Still, teachers recognised a real need to use digital devices and different software, which brought new digital skills and may have changed attitudes towards digital technology.

Discussion

This qualitative study investigated teachers’ experiences in teaching pupils with ID via distance education in Finland because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The found experiences are reviewed through the concept of professional agency (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998; Priestley et al., Citation2015a, Priestley et al., Citation2015bLinkManagerBM_REF_xeCOtELm). The three areas: mixed emotions, new ways of cooperation and teachers’ new but forced learning experiences first seemed to just decrease but finally also increased teachers’ professional agency. The individual effects on each teacher varied. We will discuss the results according to the three dimensions of agency ().

The iterational dimension suggests that agency does not come from nowhere, but is based on past experiences, achievements, and patterns of action (Emirbayer & Mische, Citation1998). These experiences can be made reflectively available (Priestley et al., Citation2015b). Nevertheless, previous experiences of distance education did almost not exist. This resulted in a situation where at the beginning the transition to distance education caused a lot of fear and worry among the teachers participating in our study. Distance education also caused stress to teachers and families elsewhere (Oducado, Rabacal, Moralista, & Tamdang, Citation2021). Practical teaching arrangements, personal and pupils’ health, and the coping of families were the central issues. However, professional experiences can be less important than personal experiences in shaping teacher agency (Priestley et al., Citation2015b). So, despite challenges, several teachers felt enthusiasm and saw the new situation also as an opportunity to develop new ways of teaching and interacting. They believed in their capacity to learn and manage new situations and they act as “active agents” (Priestley et al., Citation2015a) in developing teaching methods for distance education. Zhao (Citation2020) says that the COVID crisis enabled us to rethink education. After the initial shock, teachers’ attitudes towards distance education became more positive. The essential thing in distance education was to handle the individual needs of pupils with ID and also of their families. This differs from the normal situation where teachers’ focus is mainly on pupils.

The projective dimension concerns teachers’ aspirations, both short and long-term, in relation to their work (Priestley et al., Citation2015b). Teachers’ professional agency manifested in their activities during distance education. After the first emotions awakened in the beginning, the teachers were projective, and they soon started to look forward, building new structures in the current situation (Priestley et al., Citation2015a) about how to support pupils’ learning. They did not stagnate; instead, they started to plan within the framework of the situation based on their iterational aspects (Priestley, Citation2015a) like the personal capacity to use different digital devices and platforms and prior experiences of teaching pupils with intellectual disabilities. According to the teachers’ experiences, this happened even though there were some negative attitudes towards distance learning. The teachers were aware that teaching pupils with intellectual disabilities in distance education required active support and cooperation with guardians. This desire to respond to the challenge posed by a pandemic and develop new teaching methods can be interpreted as part of the teachers’ agency that was needed to survive this unexpected situation (Ehren et al., Citation2021; Gudmundsdottir & Hathaway, Citation2020).

The practical-evaluative dimension includes situational factors (Priestley et al., Citation2015a), such as government orders and resources at school. The availability of digital devices and the school assistants’ workforce as well as teachers’ work arrangements during distance education had an important effect on the teachers’ agency and possibilities to carry out teaching. Teachers have to make daily decisions based on resources. This may involve compromises and conflict with teachers’ aspirations. Resources available varied from teacher to teacher, which may have inhibited possibilities for agency (also Priestley et al., Citation2015b).

Individual teachers implemented structured and less structured distance education. This manifested teachers’ agency, which includes autonomy to make their own decisions and changes (Maclellan, Citation2007; Molla & Nolan, Citation2020). Finnish teachers have autonomy in education once the objectives of the curriculum are met (Saari, Salmela, & Vilkkilä, Citation2017; Stenberg, Citation2011). In this situation, power over educational issues was shared with guardians (Molla & Nolan, Citation2020). However, teachers were careful not to use too much power and to listen to the guardians. Teachers’ agency was relational (Imants & Van der Wal, Citation2019; Pyhältö et al., Citation2014), and the agency was shared with guardians in order to support the learning of pupils with ID together with the families. The implementation of distance education would not have been possible without support from families, which agrees with the results of Martin (Citation2020), who observed that digital education has provided unique opportunities to directly engage with guardians more frequently than before. As Brown et al. (Citation2021, p. 136) wrote, “teachers as parents and parents as teachers” was a theme in teaching during COVID-19. To keep the situation in balance required strong agency from the teacher who, finally, was responsible for the delivery of education.

The distance education period gave space for teachers’ creativity; old ways of working had to be reformed. Professional agency involves creative work practices and innovative work behaviour (Hitlin & Elder, Citation2007; Priestley et al., Citation2015a; Vähäsantanen et al., Citation2019), which was observed in teachers’ acts and experiences in our study. An important part of the concept of professional agency is to promote professional development (Lipponen & Kumpulainen, Citation2011) which was also realised during distance education, and almost all teachers experienced they had learnt a lot.

This study has limitations. The delivery of the questionnaire was unsystematic, mainly via social media. Responses were perhaps only sent by the most active teachers or those who managed the situation quite well. Also, the voices of pupils and their guardians were unheard in our study. As Schaefer, Abrams, Kurpis, Abrams, and Abrams (Citation2020) reported, pupils can have useful suggestions on how to improve distance education. Pupils’ perspectives need to be studied in the future. It is possible that pupils with the greatest needs might not have received all the support they needed. Guardians are not, and need not be, professionals in education. Also, many guardians were laid off from their work during COVID-19, and unemployment increased (Maier, Klevan, & Ondrasek, Citation2020). In the future, the experiences of guardians also need to be studied.

A distance education period demands a lot from the teachers. It will be interesting to see which of the working methods and practices learnt during distance education survive after distance education and how the teachers’ work changes, or if it changes. Kamsker, Janschitz, and Monitzer (Citation2020) highlighted the use of different digital platforms and courses in university studies. It is worth considering whether digital courses and distance education could also be used to support the learning of pupils with ID or pupils with other learning disabilities in the future. However, as Priestley et al. (Citation2015b) said, if agency today is influenced by experiences from the past, we can conclude that todays’ contexts will impact the future agency of teachers.

This study revealed that although teaching pupils with ID is demanding and requires individualisation, it can also be done through distance education. Nevertheless, a longer time in distance education might induce different experiences. Teachers’ agency and support for pupils’ and guardians’ agency promoted learning. Additionally, it was evident that significant elements were missing during distance education, as one teacher said – physical presence, gestures and touch. Several teachers also expressed that they hoped to start teaching “normally” soon.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Riikka Sirkko

Riikka Sirkko, PhD, works as a university teacher in special education at the University of Oulu. Her research interests focus on inclusive education at all educational levels and the education of pupils with intellectual disabilities.

Marjatta Takala

Marjatta Takala works as a professor of special education at the University of Oulu, Finland. Her research interests include special and comparative education, inclusion, curriculum design, hearing-impairment and teachers’ professional development.

References

- AAIDD, American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. (2020). Definition of intellectual disability. https://www.aaidd.org/intellectual-disability/definition

- Aditya, D. S. (2021). Embarking digital learning due to COVID-19: Are teachers ready? Journal of Technology and Science Education, 11(1), 104–116.

- Bhamani, S., Makhdoom, A. Z., Bharuchi, V., Ali, N., Kaleem, S., & Ahmed, D. (2020). Home learning in times of COVID: Experiences of parents. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 7(1), 9–26.

- Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 624–640.

- Biesta, G. J. J., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: Towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 132–149.

- Börnert-Ringleb, M., Casale, G., & Hillenbrand, C. (2021). What predicts teachers’ use of digital learning in Germany? Examining the obstacles and conditions of digital learning in special education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 36(1), 80–97.

- Brown, J., McLennan, C., Mercieca, D., Mercieca, D. P., Robertson, D. P., & Valentine, E. (2021). Technology as thirdspace: Teachers in Scottish schools engaging with and being challenged by digital technology in first COVID-19 lockdown. Education Sciences, 11(3), 136.

- Clandinin, J. D., & Husu, J. (2017). The Sage handbook of research on teacher education. UK: Sage.

- Downes, N. (2013). The challenges and opportunities experienced by parent supervisors in primary school distance education. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education, 23(2), 31–41.

- Ehren, M., Romiti, M. R., Armstrong, S., Fisher, P., & McWhorter, D. (2021). Teaching in the COVID-19 era: Understanding the opportunities and barriers for teacher agency. Perspectives in Education, 39(1), 61–76.

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 1–10.

- Emirbayer, M., & Mische, A. (1998). What is agency? The American Journal of Sociology, 103(4), 962–1023.

- Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2014). Miten käsitteellistää ammatillista toimijuutta työssä? [How to conceptualize professional agency at work?]. Aikuiskasvatus [Adult Education], 34(3), 202–214.

- Finnish Basic Education Act 628/1998. https://finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1998/19980628

- Finnish Basic Education Decree 628/1998. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/smur/1998/19980852

- Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, 2014. Oppimisen ja hyvinvoinnin tuki. Selvitys kolmiportaisen tuen toimeenpanosta [Support for learning and well-being. Report on the implementation of the three-step support]. Publications of the Ministry of Education and Culture 2014:2 2014: . https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/75235/okm02.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Finnish National Agency for Education. (2016). National Core Curriculum 2014. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

- Fu, J. (2013). ICT in education: A critical literature review and its implications. International Journal of Education and Development Using Information and Communication Technology, 9(1), 112–125.

- Gudmundsdottir, G. B., & Hathaway, D. M. (2020). “We always make it work”: Teachers’ agency in the time of crisis. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 239–250. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216242/

- Hallamaa, J. (2018). Yhdessä toimimisen etiikka. [Ethics of collaboration]. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Heinonen, O. (2020). Etäopetus ei ole kotiopetusta. [Distance education is not home-schooling.] Retrieved from https://www.oph.fi/fi/blogi/etaopetus-ei-ole-kotiopetusta

- Hitlin, S., & Elder, G. H. (2007). Time, self, and the curiously abstract concept of agency. Sociological Theory, 25(2), 170–191.

- Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277‒1288.

- Imants, J., & Van der Wal, M. M. (2019). A model of teacher agency in professional development and school reform. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 52(1), 1‒14 https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1604809.

- Judge, M. (2021). Covid 19, school closures and the uptake of a digital assessment for learning pilot project during Ireland’s national lockdown. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 419–429.

- Kamsker, S., Janschitz, G., & Monitzer, S. (2020). Digital transformation and higher education: A survey on the digital competencies of learners to develop higher education teaching. International Journal for Business Education, 160, 22–41.

- Karakaya, F., Adıgüzel, M., Üçüncü, G., Çimen, O., & Yilmaz, M. (2021). Teachers’ views towards the effects of Covid-19 pandemic in the education process in Turkey. Participatory Educational Research, 8(2), 17–30.

- Kier, M., & Clark, K. (2020). The rapid response of William & Mary’s School of Education to support preservice teachers and equitably mentor elementary learners online in a culture of an international pandemic. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 28(2), 321–327. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/216153/

- Koivikko, M., & Autti-Rämö, I. (2006). Mitä on kehitysvammaisen hyvä kuntoutus? [What is good rehabilitation for the person with intellectual disability?]. Duodecim: Lääketieteellinen Aikakauskirja, 122(15), 1907–1912. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17091642

- Kokko, T., Pesonen, H., Polet, J., Kontu, E., Ojala, T., & Pirttimaa, R. (2013). Erityinen tuki perusopetuksen oppilaille, joilla tuen tarpeen taustalla on vakavia psyykkisiä ongelmia, kehitysvamma- tai autismin kirjon diagnoosi. [Special support for students in basic education who have a serious mental health problem, a diagnosis of a developmental disability or an autism spectrum]. VETURI-hankkeen kartoitus 2013.

- Kuusimäki, A.-M., Uusitalo-Malmivaara, L., & Tirri, K. (2019). Parents’ and teachers’ views on digital communication in Finland. Education Research International, 29, 2019, 1–7.

- Lipponen, L., & Kumpulainen, K. (2011). Acting as accountable authors: Creating interactional spaces for agency work in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 812–819.

- Maclellan, E. (2007). Shaping agency through theorizing and practicing teaching in teacher education. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 253–268). London: SAGE.

- Maier, A., Klevan, S., & Ondrasek, N. (2020, July). Leveraging resources through community schools: The role of technical assistance. Learning Policy Institute. Policy Brief. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/leveraging-resources-community-schools-technical-assistance-brief

- Martin, A. (2020). COVID notes from the field: Transitioning to digital learning. Georgia Educational Researcher, 17(2), Article 7.

- Mikola, M. (2011). Pedagogista rajankäyntiä koulussa: Inkluusioreitit ja yhdessä oppimisen edellytykset. [Defining pedagogical boundaries at school – The routes to inclusion and conditions for collaborative learning.]. Finland: University of Jyväskylä.

- Molla, T., & Nolan, A. (2020). Teacher agency and professional practice. Teachers and Teaching, 26(1), 67–87.

- Noy, C. (2008). Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11(4), 327–344.

- Oducado, R. M. F., Rabacal, J. S., Moralista, R. B., & Tamdang, K. A. (2021). Perceived stress due to COVID-19 pandemic among employed professional teachers. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation, 15, 305–316.

- Pantić, N. (2015). A model for study of teacher agency for social justice. Teachers and Teaching, 21(6), 759–778.

- Parliament of Finland. (2020). Adoption of the Emergency Powers Act during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.eduskunta.fi/EN/naineduskuntatoimii/kirjasto/aineistot/kotimainen_oikeus/LATI/Pages/valmiuslain-kayttoonottaminen-koronavirustilanteessa.aspx

- Patel, D. R., Greydanus, D. E., & Merrick, J. (2014). Intellectual and developmental disability. In D. R. Patel, D. E. Greydanus, & J. Merric (Eds.), Intellectual disability: Some current issues (pp. 3–13). New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

- Philpott, C., & Oates, C. (2017). Teacher agency and professional learning communities: What can learning rounds in Scotland teach us? Professional Development in Education, 43(3), 318–333.

- Pirttimaa, R., Räty, L., Kokko, T., & Kontu, E. (2015). Vaikeimmin kehitysvammaisten lasten opetus ennen ja nyt. [Teaching children with the most severe developmental disabilities before and now.]. In M. Jahnukainen, E. Kontu, H. Thuneberg, & M. Vainikainen (Eds.), Erityisopetuksesta oppimisen ja koulunkäynnin tukeen [From special education to support of learning and schooling] (pp. 179–200). Jyv‘skyl‘: Suomen kasvatustieteellinen seura.

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G. J. J., Philippou, S., & Robinson, S. (2015a). The teacher and the curriculum: Exploring teacher agency. In D. Wyse, L. Hayward, & J. Pandya (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of curriculum, pedagogy and assessment (pp. 187–201). London: SAGE.

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G. J. J., & Robinson, S. (2015b). Teacher agency: What is it and why does it matter? In R. In Kneyber & J. Evers (Eds.), Flip the system: Changing education from the bottom up (pp. 1–11). London: Routledge.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2014). Comprehensive school teachers’ professional agency in large-scale educational change. Journal of Educational Change, 15(3), 303–325.

- Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2015). Teachers’ professional agency and learning—From adaption to active modification in the teacher community. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(7), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.995483

- Räty, L., Vehkakoski, T., & Pirttimaa, R. (2019). Documenting pedagogical support measures in Finnish IEPs for students with intellectual disability. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 34(1), 35–49.

- Saaranen-Kauppinen, A., & Puusniekka, A. (2006). KvaliMOTV - menetelmäopetuksen tietovaranto. [KvaliMOTV - methodological data repository.] Yhteiskuntatieteellinen tietoarkisto. https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/menetelmaopetus

- Saari, A., Salmela, S., & Vilkkilä, J. (2017). Bildung- ja curriculum-perinteet suomalaisessa opetussuunnitelma-ajattelussa. [Bildung and curriculum traditions in Finnish curriculum thinking.]. In T. Autio, L. Hakala, & T. Kujala (Eds.), Opetussuunnitelmatutkimus: Keskustelunavauksia suomalaiseen kouluun ja opettajankoulutukseen [Curriculum research: Discussion openings for Finnish schools and teacher training] (pp. 61–82). Tampere: Tampere.

- Sahlberg, P. (2013). Teachers as leaders in Finland. Educational Leadership, 71(2), 36–40.

- Schaefer, M. B., Abrams, S. S., Kurpis, M., Abrams, M., & Abrams, C. (2020). ‘Making the unusual usual: Students’ perspectives and experiences of learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Middle Grades Review, 6(2), Article 8. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/mgreview/vol6/iss2/8

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. California: Sage.

- Siddiq, F., & Scherer, R. (2016). The relation between teachers’ emphasis on the development of students’ digital information and communication skills and computer self-efficacy: The moderating roles of age and gender. Large-scale Assessments in Education, 4(17), 1–21.

- Stenberg, K. (2011). Riittävän hyvä opettaja. [Good enough teacher.] PS-kustannus.

- Tanhua-Piiroinen, E., Kaarakainen, -S.-S., Kaarakainen, M.-T., & Viteli, J. (2020). Comprehensive schools in the digital age II. Publications of the Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland 2020:17. http://urn.fi/URN:978-952-263-823-6

- Unicef. (2020). Education and COVID-19. https://data.unicef.org/topic/education/covid-19/

- Vähäsantanen, K., Räikkönen, E., Paloniemi, S., Hökkä, P., & Eteläpelto, A. (2019). A Novel Instrument to Measure the Multidimensional Structure of Professional Agency. Vocations and Learning, 12(2), 267–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9210-6

- van Laar, E., van Deursen, A., van Dijk, J., & de Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 577–588.

- Zhao, Y. (2020). COVID-19 as a catalyst for educational change. Prospects: Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 49(1–2), 29–33.