ABSTRACT

Writing in discipline and across the curriculum as an academic literacy practice has been the subject of a growing body of research in HE over the past few decades. In Bangladesh, however, effective academic writing in English as a second language (ESL) is an interminable challenge for tertiary students. This study uses a sociocultural theoretical lens by applying a CHAT framework to develop an in-depth, contextualised understanding of how Bangladeshi HE students engage with writing in an ESL setting while collaborating among individual learners and their social learning contexts. Drawing on data collected from in-depth interviews, the paper elucidates how learners construct subjective accounts of their perception of academic writing in HE and identifies six contradictions in their writing trajectory. In conclusion, the implications of utilising a CHAT framework as a reflective tool to re-evaluate, re-envision and remodel learning activity systems while steering interventions at micro, meso and macro-level policymaking to enhance expansive learning are discussed.

Introduction

Central to learning, teaching and assessment in higher education (HE), academic writing is widely acknowledged as being beneficial for students as it develops metacognition, critical thinking skills as well as “deep” approaches to learning (Prosser & Trigwell, Citation1999) by means of expository and argumentative prose used to disseminate a body of information about a particular topic. As a skill often considered to be acquired “implicitly through purposeful participation, not instruction” (encountersIvanic R, Citation2004, p. 235), educators and researchers of disciplinary genres have nonetheless advocated the significance of teaching and developing academic writing skills, particularly in English as Second Language (ESL) context within HE settings. Evidently, a considerable number of seminal studies in academic writing theory and pedagogy in HE (Barnett & Coate, Citation2004; Beaufort, Citation2007; Ganobcsik-Williams, Citation2006) have sought to determine practices of teaching with writing for assignments (Graham, MacArthur, & Fitzgerald, Citation2013) as part of instructional discourses and epistemologies of learning to write (Werder & Otis, Citation2010). Few attempts have been made to create academic identities within disciplinary and professional boundaries (Lea & Stierer, Citation2009) while eliciting metacognitive experiences and reflection. Notably, much research has been undertaken in nursing education (Andre & Graves, Citation2013; Giles, Gilbert, & McNeill, Citation2014) among other specialised domains like medicine (Cooke, Irby, & O’Brien, Citation2010), business (Colby, Ehrlich, Sullivan, & Dolle, Citation2011), engineering (Sheppard, Macatangay, Colby, & Sullivan, Citation2008) and law (Sullivan, Colby, Wegner, Bond, & Shulman, Citation2007).

However, owing to a paradigm shift from the cognitive to the sociocultural approach (Johnson & Golombek, Citation2011; Yoon & Kim, Citation2012), the necessity of contextualising academic writing practices in second language learning within a sociocultural framework has gained growing recognition (Block, Citation2003). Since, within a sociocultural perspective, language is effectively seen “as part of larger meaning-making resources that include the body, cultural-historical artefacts [and] the physical surroundings” (van Lier, Citation2008, p. 599), its usage is essentially considered to be embedded within a dialogical perspective (Zheng & Newgarden, Citation2011). As a core social “process of creating, co-creating, sharing and exchanging meanings” (van Lier, Citation2008, p. 599), which is key to “interactions, [social] activities and situations” (Linell, Citation2009, p. 15) in social learning contexts, several major studies conducted over the past decades, resonated ESL students’ voices about their triumphs, tribulations and expectations (Alan & Sweetland, Citation2005; Leki & Carson, Citation1997; Maharsi, Citation2007; Stuart, Citation2012; Whitehead, Citation2002) about the effectiveness of ESL academic writing courses.

Hence, this present study aims to bridge that empirical gap by taking a sociocultural approach to capture ESL students’ experiences and reflections on their interactions with academic writing courses embedded in social and cultural practices by drawing on Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT). Through the documentation of the cases of twelve Bangladeshi ESL students in a higher education institution (HEI), this paper delves deep into their insights, experiences and expectations in consideration of the teaching and learning of academic writing, from the way they give meaning to it to how they overcome the difficulties from a perspective where it is possible to prescribe effective solutions to the integration of writing skills within the core curriculum structure itself. Such exploratory investigation, therefore, has the potential for significant impact on the practices of both ESL students and academic staff considering the social need to transform curriculum and writing practices across primary, secondary and tertiary educational institutions, particularly in South Asia, and specifically in Bangladesh.

Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) in educational research

To provide a meta-interpretation of the way the teaching and learning activities of a group of ESL students are constituted, this study design draws upon the theoretical lens of a sociocultural approach. Thus, this study operationalises concepts from CHAT to decipher how the students make sense of their own learning experiences of academic writing in HE in the light of “teaching approaches, learning resources” and other relevant institutional factors that “shape their encounters with the curriculum” (Ashwin & Mcvitty, Citation2015).

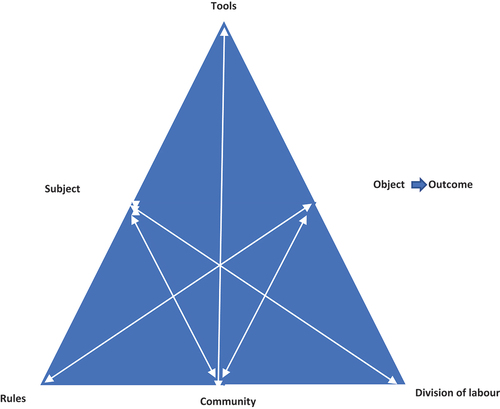

Originating in sociocultural theory through the works of Vygotsky (Citation1978), Leont’ev (Citation1981) and later Engeström (Citation1987), CHAT highlights interaction among subject, object, activity, goals, motivation, outcomes and socio-historical context. This activity systems analysis, developed from CHAT, can be valuable for “qualitative researchers and practitioners who investigate issues related to real-world complex learning environments” (Yamagata-Lynch, Citation2014, p. 1). Designed to augment understanding of human activity in a collective context, this analysis method is graphically represented by a series of triangle diagrams (see ), guiding researchers and practitioners in their design, implementation, analysis, and development of conclusions in a research study. In this activity system model, the subject is the individual or group of individuals involved in the activity. The tool includes social and other artefacts that can act as resources for the subject in the activity. The object is the goal or motive of the activity. The rules are any formal or informal regulations that affect how the activity takes place. The community is the social group that the subject belongs to while being engaged in an activity. The division of labour refers to how the tasks are shared among the community. Lastly, the outcome of an activity system is the end result of the activity. This analysis method can help researchers and practitioners understand individual activity in relation to its context and how the individual, through his/her activities, within the context, affects one another.

Figure 1. Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) (Adapted from Engeström, Citation1987)

CHAT is relevant in situations where the partakers effectively use tools and cultural artefacts that are in a process of constant change to facilitate the achievement of certain learning, teaching or assessment goals. The key conceptualisation of CHAT arises through an understanding of human consciousness as shaped by experience from the societal structure and subjectivity of awareness. Applying the CHAT framework provides researchers with both conceptual and practical tools to observe the internal tensions and contradictions within the complex interrelationship between multiple activity systems to facilitate opportunities of contradictions for reflexivity as well as interventions and transformation in teaching and learning and professional work practices.

Over the past two decades, CHAT had been increasingly utilised as a multifaceted research toolkit of sociocultural approaches in reforming teaching practices (Kim, Citation2011) and developing curricula across multiple disciplines such as, clinical psychology (Sundet, Citation2010); medicine (Heeneman & de Grave, Citation2017); organisational development (Blackler, Crump, & McDonald, Citation1999), digital technologies (Lim & Hang, Citation2003), architecture (Groleau, Demers, Lalancette, & Barros, Citation2012) as well public policy development (Canary, Citation2010).

More specifically, a notable number of CHAT research in the domain of English studies have focused on students’ conceptualisation of learning English (Bazerman, Citation2012); the use of critical literacy (Burgess, Citation2007); the role of classroom discourse in learning (Mercer, Citation2008); novice English teachers’ notion of pedagogy (Smagorinsky, Citation2015) and development of writing abilities (Russell, Citation2009; Thompson, Citation2012). Even though a growing number of CHAT studies in ESL have concentrated on computer-assisted language learning (Blin, Citation2004; Montoro & Hampel, Citation2011); variations in students’ interactions in the ESL context (Storch, Citation2004); second language (L2) vocabulary learning (McCafferty, Roebuck, & Wayland, Citation2001) and motive in L2 oral proficiency (Yu, Citation2015), there has been little research as a mean to highlight collaborations among individual ESL learner and their social learning contexts.

Having been influenced by the sociocultural perspective of human learning, which accounts for the mediation of human activity using cultural artefacts and tools, this particular study encompasses an epistemological stance that students’ cognitive development can be delineated as well as represented vis-à-vis the context, culture and communities wherein it is embedded. As issues with regard to higher education institutions (HEI) and teaching/learning practices become more and more complex, a solid theoretical basis utilised to change practices through a student-led intervention can greatly improve the way effective instruction is envisaged. In exploring how a group of Bangladeshi tertiary students mediate activities by writing for academic purposes, using CHAT as a framework allows for richer and thicker conceptualisations of individual experiences of academic writing that occur in communal practices and communities, shaped by multiple interpretations and affinity.

Language movements in Bangladesh: a historical perspective

English as a second language (L2) was brought to the Indian subcontinent as part of colonial rule and was seen as the language of power and social mobility (Earling et al., Citation2013). With the decolonisation in 1947, India was split into two so that Pakistan could emerge. While West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) were divided by over 1000 miles of Indian territory, the rift grew wider with the Language Movement in 1952 to uphold Bengali, not Urdu, as the only state language, which eventually culminated in the creation of Bangladesh as a nation (Musa, Citation1996) in 1971. As Bengali was given the status of a national language post-independence, it became the medium of instruction at every primary, secondary and tertiary level of education until the education policymakers began to perceive the damage done to English language teaching (ELT) and learning and reintroduced it into the national curriculum as a mandatory subject from Grade 1–12 in 1991. Subsequently, due to increased demand for higher education (HE) resulting from demographic growth, the government of Bangladesh, by proclamation of the Private University Act, 1992 (Kabir, Citation2012), approved and initiated the privatisation of HE, which is a milestone in the exclusive usage of English as the medium of instruction.

The study

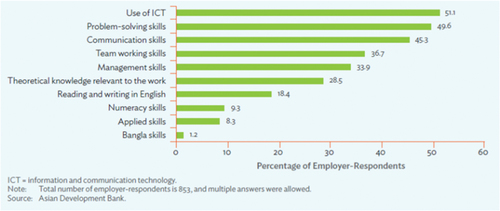

Given the context of Bangladesh, where more than 160 million people speak Bengali as the national language in domains of governance, education, law, media and everyday communication besides English being used in higher education (University Grants Commission, Citation2011) and research as well as commerce, industry and international communication (Roshid, Citation2014), student’s English language proficiency is found to be very unsatisfactory. According to an Asian Development Bank (Citation2019), nearly 39% of graduates remain unemployed for as long as two years, while employers found graduates lacking skills that mainly comprised of English language and communication skills, Information and Communications Technology (ICT), and the essential, transferable skills (see below).

Figure 2. Skill areas where universities need more focus

Even after years of compulsory English language instruction, writing is “the least developed English language skill among the learners in Bangladesh” (Uddin, Citation2014), abundant with “problems [of] writing (in)coherently and re-structuring ideas” (Mustaque, Citation2014) besides grammatical, lexico-syntactic and organisational errors (Afrin, Citation2016; Akhter, Citation2016). Whilst prior studies have primarily focused on the frequency of errors and writing difficulties besides approaches to the teaching of academic writing (Uddin, Citation2014), there have not been many case studies to understand academic practices in the light of student interpretations and conceptualisations of writing as an integral element of academic literacy in Bangladeshi HE institutional settings.

Therefore, this paper presented an overview of the challenges experienced by Bangladeshi ESL learners in their encounters with academic writing practices to bring about necessary changes in curriculum pedagogy and institutional structures. Building on from this idea, the paper utilised a descriptive tool of a cultural-historical activity system to “tease out” (Hasan & Kazlauskas, Citation2014), and delineate human activities to develop critical writing and analytical skills embedded in academic literacy skills vital to intellectual growth personal development and employability. As a whole, a conceptualisation of the activity system developed interventions to translate evidence towards macro, meso and micro language policies while recognising the importance of writing for research and lifelong learning to reach sustainable development goals.

Data collection & analysis

In the light of an interpretive enquiry, a qualitative design was chosen for this small-scale research to examine the various ways Bangladeshi ESL students identified and created meaningful connections through their experiences of the social world. As this study shed light on students’ perceptions of their attainments and the challenges in academic writing, “efforts [were] made to get inside the person and to understand from within” (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, Citation2018, p. 19). Accordingly, a case study approach was adopted not only to “investigate a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context” (Yin, Citation2014, p. 13), but also to construct a multi-dimensional representation of individual perceptions of learning experiences. Allowing to “establish theoretically valid connections between events and phenomena which previously were ineluctable” (Mitchell, Citation1984, p. 239), such analysis explores how these individuals weave their experiences in multiple layers. As people experience the world and reflect upon these experiences and build their own representations in relation to their social realities, a rich and deeper understanding of the complexities in constructing stories as experienced by individuals is constantly in the making. In view of this, the study drew on a narrative analysis of semi-structured interview accounts of a small group of ESL students. Each interview lasted about 60–90 minutes, and all interviews were voice recorded, anonymised and then transcribed, with more emphasis on significance than grammatical accuracy.

The focus being on ESL learners and their interactions with academic writing, CHAT was implemented as a process-oriented theoretical lens to ensure systematic and comprehensive data extraction while seeking answers to the following research questions:

In what ways do Bangladeshi ESL students experience the trajectory of academic writing?

How do the students perceive the instructional tools/instrument utilised in the process of their academic writing?

While encapsulating the experiences of ESL students in their writing courses, CHAT could be a useful approach hence employed to understand, identify and overcome barriers to changing established academic practices with regard to the institutionalised system wherein the ESL classrooms and teachers operate in the way they do. The strength of such a framework particularly lies in its ability to examine “social activities” and their impact on “the social conditions and systems that are produced in and through such activity” (Daniels, Citation2008, p. 115). Furthermore, in educational research, the value of the CHAT model lies not only in its evocative power but in its authority to provide opportunities for contradictions as a transformative influence for students and educators. As these individual cases recounted their episodic experiences with academic writing, the key objective was not to draw generalisations from a representative sampling but to account for an in-depth analysis providing a more holistic and systematic interpretation of L2 students’ voices about their expectations and reality.

Ethical considerations

Participation was voluntary and signed informed consent was obtained from all individual participants involved in the study. The participants were ensured that their participation involved no foreseeable social, cultural, political or institutional risk. All were given the opportunity to decline to partake in the study at any time. In disseminating findings from the study, the confidentiality of individual participants was ensured, and any personal identifier was removed.

Participants

This study was conducted at a private university in Bangladesh. The participants, aged between 20 and 30, were randomly selected from returning graduate and undergraduate students’ lists studying Business Administration, Computer Science and Engineering, Media and Communications Studies, English Language Teaching and sustainability degrees such as Environment Science and Management and Development Studies. All the participants had completed three mandatory English language courses despite the different disciplines they belonged to. A detailed pen portrait of five male and six female respondents, as associated with their knowledge, beliefs and associations with academic writing, offered “translucent windows into cultural and social meanings” (Patton, Citation2002, p. 116) in an ESL environment.

The institutional context

Established over two decades ago, the University of Bangladesh (pseudonym) has ten departments under six academic faculty: English, Media Studies, Social Sciences, Law, Public Health, Pharmacy, Engineering, Physical Sciences, Environmental Science and Life Sciences. It currently enrols over 8000 undergraduate and graduate students and has over 12,000 alumni. More than 45% of the academic staff hold PhD and postgraduate degrees from foreign universities in English-speaking countries. English is the primary medium of instruction (MOI) at the University of Bangladesh (UoB). Lectures and assessments are conducted in English and all instructional materials are in English. However, there are no official language policy documents defining the breadth of the usage of English in teaching, research and administration at the meso and micro levels.

To support the usage of English in teaching and learning, the UoB offers a mandatory university-readiness English language programme for students who gain admission through an English and mathematics placement test meeting strict entry requirements. Even though clear institutional language-in-education policies have yet to be laid down explicitly in strategic documents of UoB, prospective students with a minimum SAT score of 1000 and a minimum IELTS score of 5.5 or TOEFL score of 550 (paper-based) are exempted from the entry admission test. Upon admission, students are required to complete three academic English courses and two mathematics courses as part of a general education foundation programme. These courses run alongside specialised content courses in the first one to two years from admission. The foundation programme offers four other major areas of education besides communication skills and numeracy- computer skills, natural sciences, social sciences and humanities.

The English programme at the foundation level consists of three levels: elementary, intermediate and advanced. The programme is designed to help students achieve an intermediate level of language proficiency before they can register for major courses. Thus, the newly admitted students are allocated to these levels based on the admission test results. All three English foundation courses earn students credits: Listening and Speaking Skills, Reading and Composition and Business English. The main purposes of these courses are to equip students, regardless of their specialisation, with the necessary language skills to help them cope with learning in their respective academic subjects and the potential challenges of English as an MOI. Each English course offers three contact hours a week, two hours of tutorial and an hour of practice at the English Language Centre every week, besides guided self-study and English language practice over the weekends for students needing further language support.

The English Language Centre at UoB was established in 2016 to provide general English language support to students. Based on diagnostic language tests and needs analyses, one-to-one or closed-group language support is provided to students besides tutorials. All students at the UoB can avail of the various academic English courses in communication skills, academic reading and grammar rather than guidance on academic writing, critical thinking, study skills and analysis skills, providing students with assistance on their papers, projects, reports, and other common academic genres across disciplines.

Analysis

At the initial stage, by using NVivo qualitative data analysis software, the interview transcripts were closely studied and annotated for preliminary coding of each individual student’s transcription as well as for the organisation of data with regard to themes. A top-down coding protocol, based on the theoretical constructs of CHAT, was operated to guide the coding of each transcript (see ). The coding protocol included definitions of CHAT system components from existing literature and was operationalised by the guiding questions and examples extracted from the interviews almost verbatim with minor grammatical corrections. Whilst the transcribed texts were unitised into one identifiable idea, duly aimed at gaining students’ insight about the phenomenon of ESL academic writing, statements found to be relevant to the research questions were selected, marked and coded as emerging categories functioning as the tools or artefacts that were mediated by the students to attain the object of the activity system of writing regarding rules and division of labour within the social context. As the descriptive extracts of the participants were analysed, particular attention was paid to how the participants perceived the challenges, concerns and perspectives in terms of what was instrumental in learning to write in ESL. Finally, notes were compiled and collated in support of the analysis of the data.

Table 1. Bangladeshi ESL students’ experiences of academic writing: A top-down coding protocol.

Findings

The following part of this paper describes, in greater detail, the Bangladeshi ESL students’ experiences with the challenges and successes in their learning trajectory of academic writing practices and chronicles their perceptions regarding the utilisation of instruments and tools in the process. As contradictions within the activity system of writing emerged in the students’ voices, they were able to reflect on their circumstances to seek solutions. In presenting their worldview of the contextual elements of academic writing while seeking solutions for the same, six themes emerged from the analysis of the transcribed data: writing inside the disciplines, grammatical and lexical interferences, a clear framework of writing goals and processes, showcasing of good models of writing, technology solutions and lastly, use of peer review in academic writing.

Writing inside the disciplines

One of the respondents preferred to learn how to write a research proposal or report in his discipline rather than learn how to write a “claim letter”. He reported that the mandatory academic skills courses offered by his university in his first year only “focused on basic communication, reading and basic writing skills” and failed to “help much” in writing “discipline- specific assignments”. He emphasised that such English courses if taught, should cover all the key “vocabulary”, “terms” and their “usage” in “the way a student will come across in textbooks, articles and lectures” to raise his/her language awareness in the particular “academic discipline”. Had vocabulary been presented, he pondered, as part of a “real-life problem” via extracts from lectures, presentations, essays, tables or any form of graphical data, students could “visualise as well as practice their language skills in various problem-solving activities” which could, in turn, be replicated in their workplace. He concluded that there should be “a specialised English course” offered as part of the Science, Technology and Engineering programme:

To write assignments in computer science, the first thing you need to know is vocabulary. Then most importantly, you need to learn how to write certain types of written assignments. You will have to learn how to write design specifications about the software or a procedure or write technical reports, lab reports, project reports besides essays. But the instructor won’t clearly tell you how to write or what structure you need to follow. It’s like a mystery you have to solve yourselves. You must figure out from the samples of essays given by teachers … how to do methodology recounts or write research reports or do literature surveys … . The remedial English courses did not help me with any of those.

Another student reported how an English course did not provide “much guidance” on the process of writing a research paper related to his/her own discipline:

The Academic English courses taught us very basic writing skills. We were asked to write 26 different journal entries in 26 classes and about the most trivial topic possible- from describing the room where we stayed to writing about memorable holidays, fears, dreams or challenges. But we learnt nothing about how to structure a research paper.

While most of the students expected that they would be taught the conventions of academic writing conforming to their specific discipline, a student from Business Administration added, “I didn’t get to know that I have to write an executive summary when I report case studies until I actually had to write one”. She further stated, “Little did I know that essays usually follow an introduction-body-conclusion structure where it is not conventional to use sub-headings as pointers for paragraphs”.

Grammatical and lexical interferences

One of the most crucial hindrances in the process of writing, the participants unanimously identified, were grammatical and lexical problems. According to one participant, the root of the problems, however, went further back:

The main problem with writing is language- both grammar and vocabulary, not to mention spelling. Since, traditionally in Bangla medium schools, we were only made to memorise some common English grammatical rules … that too … unfortunately taught in Bengali … and out of context … And generally, we were asked to translate from Bengali to English to complete writing tasks. Having learnt grammar like this, we can neither speak nor write properly.

While comments about the way most of the students received language education in a mainstream Bengali medium school in part reflected the ESL environment in a developing country, the stark reality of insufficient state spending on language teacher training besides having a good national English textbook published was also true.

Many participants felt very strongly about the school education they received and specifically pointed out how they were unable to think clearly in English and had to contemplate in Bengali first and then translate while writing, most often not being able to retrieve the exact English word owing to a lack of English vocabulary knowledge. Another student, however, identified the most recurring grammatical errors in writing due to the structural differences between English and Bengali: lack of auxiliary verbs, misuse of pronouns, articles, prepositions, subject/verb disagreement and use of the wrong tense.

A graduate student pointed out;

Bengali is the only major language we use in our everyday life. Most of us were not interested to learn English grammar the way we were taught in Bengali. Big classrooms … . Many students … so we didn’t get to practise the language much. Vocabulary didn’t even have a place. So, how do you manage to write? Lack of technical and, even worse, general English vocabulary besides writing skills created many problems with word choice and sentence formation. I just didn’t know how to transfer my ideas into sentences.

Another graduate student, however, recommended that students, from the very beginning, ought to be explicitly “instructed” about the usages of “Academic Word List”, “Academic Collocation List” and finally “Academic Phrasebank”, which he “quite sadly” was not aware of until he started studying for his second postgraduate degree. These are, according to him, “basic but highly useful toolbox” for writers in an academic context who are,

… not yet confident about presenting their studies, not knowing how to put words together even for an introduction or to describe methods, analyse, report the findings or present suggestions by drawing conclusions.

A clear framework of writing goals and processes

The participants reported that they felt writing to be unconnected to the overall learning goals of a certain course. As a student participant pointed out,

A big part of the problem starts when you are asked to choose a topic for your assignment. Without any prompts, I most often have no idea what I want to write on or why and how it will help me. Then, I am expected to write critically. How do you write critically? What do you have to use if you want to be critical? As I am unsure how the whole mysterious process of writing works, how can I be critical, let alone creative?

Teachers have an obligation, she suggested, to clearly exhibit the pathway to effective academic writing;

They usually instruct us to develop ideas from a thesis statement and asks us to pay attention to organisation, signposting and rules of paragraphing, which most of us have a very vague idea about. With very little writing practice, we prefer, when given a choice, to take written exams on what we have been taught in class rather than write term papers or assignments.

For an English major student, the process through which he was taught how to write a research paper at the postgraduate level was “quite hazy”:

We were taught about the different sections one must have while writing a research paper. But the first barrier was to making sense of what must be included in a literature review while reading resources. Then when you managed to have gathered a lot of data through interviews or surveys … the next hurdle was to interpret them … not being clear about how to report findings. Tutors gave us guidelines about what needed to be done but did not clearly explain how.

An engineering major student, however, reflected that writing one-page-long lab reports every week in a regular semester had been “really helpful” in “making the leap” to his final “big” writing project. Despite his initial struggle with academic writing, like most of his peers, he eventually learned “the ways of writing” after “more than a year” through “trial and error”.

A business major student also articulated the ineffectiveness of academic language skills courses in pointing out “specific features of academic writing” that could have helped her develop “better understanding about writing” and make improvements to her written work:

It would have been beneficial if we were clearly taught some precise rules and instructions about the whole range of strategies, from how to plan, outline and structure our writing … to presenting arguments … being critical … or doing referencing or even editing … Moreover, since we never get to see what a good essay look like … the criteria we are required to fulfil to get a good grade … we never come to know how we are supposed to write.

She, however, deeply felt the need for a writing centre in the university wherein students “in need” could receive “continuous writing support” in the form of “academic writing workshops”, “tutorials” or even “one-to-one sessions” where writing instructors would assist students with the whole writing process, from “selection of an essay topic to final editing”.

Showcase of good models of writing

All the participants articulated the challenges they had faced regarding the written projects which they were assigned in the first year of their university education, as they had not encountered such writing activities previously. Thus, a student reflected:

While giving written projects, some instructors provided guidelines, but that is it. I think it would have been beneficial if we could see some dummy assignments which we could have followed and reproduced. So, we had to guess. A lower grade in assignments meant we couldn’t write like this. But we want to understand the criteria against which our writing is assessed clearly. We always wish to receive clear feedback on where we need to work, which might help improve our next assignment.

He noted that the instructors often overestimated that all the students coming into the class would know the difference between a review, case study, term paper or a dissertation, “But most of us do not know the difference because we have not seen one! If the instructors had shown us model papers to evaluate and reflect on, we perhaps could have learnt to help ourselves”.

However, a student from the Computer Science and Engineering programme appreciated how he was given sample papers and lab reports to read and emulate, ’It was very difficult at the beginning. Still, I eventually developed awareness about structure and language by merely looking at models’.

For another student from the multidisciplinary Environment Science and Management department, it would have been helpful if every discipline had example essays and reports along with the tutor’s feedback. He suggested that it would be “beneficial” to scrutinise both “good and bad examples” of different types of essays or even sections taken from the literature review, methodology or findings section, which would make students be aware of the “patterns of writing”.

Technology solutions

Some participants expressed that to “direct students to additional resources” in this “digital age”, every university, should develop “effective and clear” instructional and study skills materials and have them indexed as “e-resources” besides a “writing handbook”. They felt the need to have all course content materials, handouts, “notes and even course-specific word glossary” organised and available as web-based resources to make it “easy for them to brainstorm about written assignments”. As a student noted,

The instructors would tell us to develop study skills while not explaining what it really meant. Further along the line … I learnt that there is unlimited availability of online resources out there … you can find everything you would need when you are stuck with your assignments … from reference management to electronic databases … I just had no idea. It is every university’s responsibility to provide these supports, at least online, if they cannot provide them to students face-to-face in class.

Several students also reiterated the need for online “how-to-write guidance” as supplements to a writing class but not as “replacements” besides a “comprehensive reading list” of learning how to write.

A few graduate students, however, reflected on the usefulness and ease of using “online grammar checker” like Grammarly or After the Deadline and stated,

Most students struggle with their academic writing without knowing that the internet offers so much. It is important that they are notified during orientation as to what is required of them and what the university will eventually deliver.

Use of peer review in teaching writing

The issue of planning in-class peer review was something the participants expected the writing tutors to guide carefully. The students consistently commented that they want to develop peer relationships with their classmates to “learn and err together” in an “interactive” class. As a student explained,

If the instructor could clarify the grading criteria and show examples of a good essay, we, the students, could have taken it from there. We can help each other from the very beginning … when we are at the earliest stage and have just written an introduction to an essay. By breaking the assignment down into smaller sections and having each other revise … comment … elaborate … .and maybe, incite and stimulate ideas which we could develop through our writing. As we all struggle with the frustration and anxiety of not being able to write well … we can at least start by reading each other’s work carefully and learn how to improve and strengthen one another’s writing by formulating constructive feedback for each other.

According to him, submitting peer-review writing assignments have the ability to create a “deeper learning opportunity” for students. Moreover, he felt the necessity of peer review to be “inclusive” in the process of learning and assessment of any course. Hence, he reported,

Traditionally, we are assessed through long essays, presentations and assignments. But, ever since I enrolled for an ELT degree, I have been assessed through peer review report, peer observation report … or even through a reflective journal I had to keep while doing teaching practicum… which have tremendously helped develop my writing skills.

Providing effective feedback, many students felt would make the writing process more collaborative through peer review, giving them opportunities to learn from one another and to think critically.

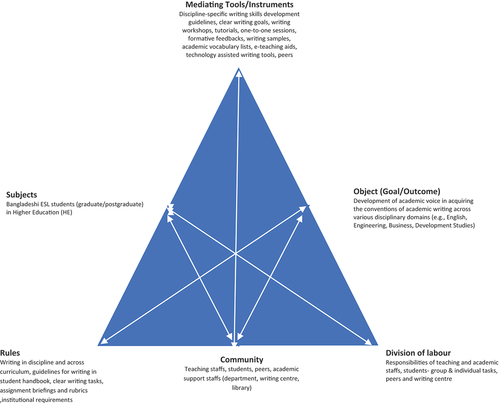

Discussions

In light of the findings, a visual representation of data gathered from the narrative accounts of the Bangladeshi ESL learners is illustrated within the methodological framework of CHAT “activity triangle” (Engeström, Citation1999) in below. To map students’ experiences of academic writing, the activity-theory framework presented a comprehensive view of their reality of academic writing as attested by the mediated tools, rules and social resources they deemed essential in their learning trajectory of writing. The participants shared information regarding existing or lacking tools, artefacts and documents related to existing rules besides the division of labour and the role of community in their learning trajectory of academic writing in HE. Hence, the triangle model in served as a visual and conceptual tool representing these ESL learners as subjects.

Figure 3. Conceptualization of Bangladeshi ESL students’ experiences & engagement with academic writing (Adapted from Engeström, Citation1987)

While the object of the activity system was conceived of as being able to write effectively in various disciplines (business, engineering and humanities and so on) and genres, the outcomes, rather by extension, comprised of “non-physical phenomenon” (DiSarro, Citation2014, p. 443) such as the development of the individual student’s academic voice, exposure to conventions of disciplinary academic writing and sustainable writing practices.

The tools are fundamental in the progression of the outcome from the object which may consist of textbooks, handouts or even cognitive artefacts such as language, beliefs and procedures. While for Vygotsky (Citation1978) human beings’ usage of tools, bound by society and culture, facilitates learning, Engeström (Citation1987) deciphers learning as the complex outcome of tool-mediated interactions. Therefore, tools or instruments are operated with regard to the teaching/learning environment, where the students, for example, expected instructors to provide in-class writing skills development guidelines alongside formative feedback to students in conjunction with electronic teaching aids and writing workshops delivered by the university writing centre.

The community within the activity system included members who adhered to prevalent rules, norms and conventions, having their roles and responsibilities be exemplified through division of labour. The community comprised of the teaching staff, the academic support staff at library, writing and IT centres, students and their peers involved at the micro level, department, administrative bodies and the institutions at the meso level.

Rules, quite generally, comprise explicit and extensive instructional guidelines as provided in a writing class prescribing how students ought to write critically in academia or typically in the form of an academic support handbook developed by the writing centre or even web-based language resources within the institution for independent study. The division of labour delineates clear roles and responsibilities to the involved participants- teachers, academic support staff, students and peers alike.

Since “activity systems are not static or purely descriptive; rather, they imply transformation and innovation” (Lantolf & Thorne, Citation2006, p. 226), the first step in the activity-theory analysis is to define each component and their interrelationships among themselves as a change in one component will change the activity system and its object. An activity theory perspective could thus provide a more holistic framework for the appraisal of writing project briefings, rubrics bounded by institutional and even state HE language policies. Through a narrative perspective, the group of ESL students (subjects) redefined the mediational tools and artefacts, which, in turn, facilitated the students in making their object and goal-oriented activity robust. To this end, they had even set a dual agenda – a rather holistic subjective one to master the conventions of academic writing (object) and a more objective outcome like knowing the variations in the different types of academic writing specific to a particular discipline. Even though contradictions, as manifested through challenges and tensions experienced by the students, were central in social development, finding ways to interrogate, identify and resolve these contradictions could model ideas for a possible change and steer towards a process of “further learning and creation of expansive solutions” (Virkkunen & Newnham, Citation2013, p. 51–52) regarding students’ transformational learning of “what is not yet there” (Engeström & Sannino, Citation2011, p. 74) to promote changes.

It is also important to highlight that such mediated tools and artefacts and “collaborative construction of opportunities” (Lantolf, Citation2000, pg. 17), as emphasised by the Bangladeshi ESL students in the form of “scaffolding” (Vygotsky, Citation1978), support from teachers, academic staff and even from “more capable peers” could be considered helpful while the adult learners developed their mental abilities and completed writing tasks being in the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, Citation1978, p. 86) well until they reached the stage wherein they could eventually perform unaided. In the light of the context which held writing to be indivisible from “humanistic issues of self-efficacy, agency and the effects of participation in culturally organised activity” (Lantolf & Thorne, Citation2007), it is crucial to recognise the use of writing for cognitive advancement as it regards learning as a cognitive process to develop conscious awareness and mastery of one’s thinking embedded within a social context.

Even though the study primarily highlighted students’ experiences with academic writing, it was evident that students were simultaneously aware of the approaches to writing and their probable outcomes. The students recognised how their previous experiences of very limited academic writing at the pre-tertiary level of education were in conflict with new expectations of academic literacy in HE. They emphasised receiving cognitive support, which additionally “consists of those elements which serve to support the students in building their understandings of, and competence in, the subject matter” (Reigeluth & Moore, Citation1999, p. 64).

Such explicit mediation and “collaborative construction of opportunities” (Lantolf, Citation2000, pg. 17), as emphasised by the Bangladeshi students in the form of support from teachers, academic staff, coaches and even from “more capable peers” is considered helpful, while the adult learners develop their mental abilities and complete tasks being in the zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, Citation1978, p. 86) well until they reach the stage wherein they can eventually perform unaided. In contrast to traditional measures of assessment that indicate the level of accomplished development, operation of the zone of proximal development (ZPD) can foreshadow what one can autonomously do in the future under particular conditions from what they can do today with assistance. As one of the primary constructs of sociocultural theory, the operationalisation of ZPD can be utilised as an andragogical tool that can be used to improve educational processes and environments as it regards learning as cognitive processes embedded within a social context, inseparable from activities like writing.

Implications and limitations of the study

The study contributes to the existing body of literature on academic literacy by applying the activity theory framework to understand interactions, tensions and difficulties that challenge students in their realisation of social activity like academic writing. Although activity system analysis has been applied to different learning settings, its formative evaluation technique can be valuable in improving and validating academic writing courses in Bangladeshi HE institutions. By pinpointing issues with individual students, this research has raised a wider institutional approach to student writing in the Bangladeshi HE context. Thus, this article demonstrates how an activity-theory framework can direct institutions, stakeholders, researchers and practitioners besides students with a reflective tool to evaluate and revise their current teaching practices of academic writing, especially at the tertiary level.

Even though CHAT has been known to have limitations while being used in the interpretation of specific enactments in a localised context of professional practices, it could potentially be used in student learning to function as a “transformative tool” through the characterisation of HE students as “human agency” (Nichol & Blake, Citation2013, p. 287) whose perceptions of ESL learning environments are directly correlated to a deep approach to their learning. By means of these in-depth situated accounts of the ESL students revealing their identity as “agents of experiences” in “exploring, manipulating and influencing the environment that counts” (Bandura, Citation2001), the efficacy of CHAT as a stimulus for change is manifested. As the study added valuable insight into the concept of student engagement in critical academic writing, it could provide a solid basis for the way teaching, learning and assessment of second language curriculum could be formulated and developed.

While not intended to make a generalised observation, the scope of this research was limited to the extent that it had engaged a small number of Bangladeshi ESL students who revealed their belief about the complexities of writing in an ESL context. As their voices echoed in the backdrop, their experiences, tensions and perceptions of their trials and tribulations helped paint a more close-up vignette which could act as a tool to lobby the government, Education Ministry and institutions for the planning of a curriculum that integrates multiple literacies (Newman, Citation2002) and corroborates the transformation of writing inside and across curriculum teaching practices. More specifically, the study offered practical implications for academics and stakeholders alike in HE to develop clear policies and guidelines about providing greater and continuous writing support to ESL learners.

Conclusion

In recent times, educational research into student teaching and learning in HE has tended to focus on ways students can be helped to adapt their practices and perception of social integration with that of the HEIs. This paper on student academic writing could build on the knowledge of the pyramid of students’ reflection on academic writing and can track the development of students’ approaches to acquiring mastery in writing skills vis-a-vis their learning experiences in various disciplines. By giving Bangladeshi ESL students the opportunity to talk about their experiences in adapting to academic writing practices in HE, this project revisits the crucial aspects of academic writing, including critical thinking, negotiation and communication of ideas, which can further support the academics in developing their teaching practices. Describing the different ways that students experience or understand the relationship between writerly support and academic literacy could be vital for the development of academic curriculum that acculturates students into the discourse and genres of a particular discipline in relation to institutional practices, power relations and identities. This route of student academic socialisation that is manifested through “new ways of understanding, interpreting, and organising knowledge” (Lea & Street, Citation2000, p. 32) could be monumental for educationalists as well as educational stakeholders, who would better be able to assist students in developing the subject-discipline discourse by developing appropriate literacy practices.

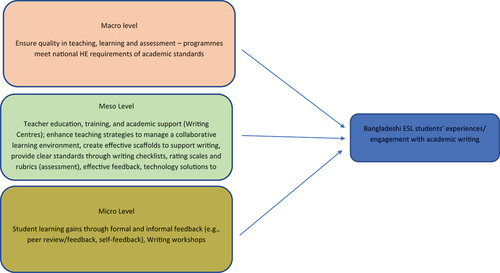

As this study has endeavoured to show, the transformational framework of the CHAT analysis of activity could be utilised to lay “emphasis on action or intervention to develop practice and the sites of practice” (Edwards & Daniels, Citation2004, p. 108) in the teaching and learning of academic writing through policy mediations at the macro, meso and micro levels ( below). Although one of the major contributions of this paper is to add to real grounded knowledge of learner experiences and perceptions of academic writing in an ESL environment, it has larger education policy relevance in the assessment of a supportive learning environment to advance the quality of teaching, particularly in south Asia, specifically in a developing nation like Bangladesh as it prepares to meet an estimated tertiary education demand of around 700,000 over the next decade (British Council Report, Citation2012). To this end, the paper could also be a part of a wider global discussion of the increasing importance of focusing on ways ESL students could be helped to adapt their writing practices and perception of social integration with that of the HE institutional policies, which account for the way learners make sense of their own learning experience, as opposed to the abstraction others may attempt to impose on them. As such, this research has provided a pathway for further research into what pedagogical practices may be implemented effectively in academic writing within a CHAT framework to successfully determine effective student learning while increasing the overall reliability of a particular teaching, learning and assessment practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Naureen Rahnuma

Naureen Rahnuma is an assistant professor in the English and Modern Languages department at Independent University, Bangladesh. Her primary research interests explore the uses and impacts of digital pedagogy in English language education for social justice, emphasising critical language awareness, second language writing pedagogy, and academic literacy. In her current role as the head of the department, her research interests broadly concern English-medium instruction policies and national quality assurance frameworks that safeguard standards in meeting regulatory and legislative requirements to improve the quality of higher education towards the internationalisation of the Bangladeshi higher education system.

References

- Afrin, S. (2016). Writing problems of non-english major undergraduate students in Bangladesh: An observation. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 4(3), 104–115. doi:10.4236/jss.2016.43016

- Akhter, A. T. (2016). The problems students face in developing writing skill: A study at tertiary level In Bangladesh. International Conference on Teaching and Learning. M. Alam, A. S. M. Asaduzzaman, & O. A. Marjuk, (eds). Dhaka: Center for Pedagogy, IUB.

- Alan, H., & Sweetland, Y. L. (2005). Two case studies of L2 writers’ experiences across learning-directed portfolio contexts. Assessing Writing, 10(3), 192–213. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2005.07.001

- Andre, J. A., & Graves, R. (2013). Writing requirements across nursing programs in Canada. Journal of Nursing Education, 52(2), 91–97. doi:10.3928/01484834-20130114-02

- Ashwin, P., & Mcvitty, D. (2015). The meanings of student engagement: Implications for policies and practices. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi, & P. Scott (Eds.), The European higher education area: Between critical reflections and future policies (pp. 343–359). Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-20877-0_23

- Asian Development Bank. (2019). Bangladesh: Computer and software engineering tertiary education in 2018. Available from

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Barnett, R., & Coate, K. (2004). Engaging the curriculum in higher education. Berkshire, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Bazerman, C. (2012). Writing with concepts: Communal, internalized, and externalized. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 19(3), 259–272. doi:10.1080/10749039.2012.688231

- Beaufort, A. (2007). College writing and beyond: A new framework for university instruction. Logan, UT: Utah State Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt4cgnk0

- Blackler, F., Crump, N., & McDonald, S. (1999). Managing experts and competing through innovation: An activity theoretical analysis. Organisation, 6(1), 5–31. doi:10.1177/135050849961001

- Blin, F. (2004). CALL and the development of learner autonomy: Towards an activity-theoretical perspective. ReCALL, 16(2), 377–395. doi:10.1017/S0958344004000928

- Block, D. (2003). The social turn in second language acquisition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press Ltd.

- British Council Report. (2012). Higher education global trends and emerging opportunities. Available from: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/528471/bangladesh-computer-engineering-education-2018.pdf

- Burgess, T. (2007). The picture of development in Vygotskyan theory: Renewing the intellectual project of English. Rethinking English in Schools: Towards a new and constructive stage. C. F. V. Ellis, and B. Street, (eds). London:Continuum.

- Canary, H. (2010). Structurating activity theory: An integrative approach to policy knowledge. Communication Theory, 20(1), 21–49. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2009.01354.x

- Chowdhury, R., & Farooqui, S. (2011). Teacher training and teaching practice: The changing landscape of ELT in secondary education in Bangladesh. In L. Farrell, N. Udaya, & R. A. Giri (Eds.), English language education in South Asia: From policy to pedagogy (pp.147–159). Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research Methods in Education (8th ed.). London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315456539

- Colby, A., Ehrlich, T., Sullivan, W. M., & Dolle, J. R. (2011). Rethinking undergraduate business education: Liberal learning for the profession. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Cooke, M., Irby, D. M., & O’Brien, B. C. (2010). Educating physicians: A call for reform of medical school and residency. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Daniels, H. (2008). Vygotsky and research. London: Routledge.

- DiSarro, D. R. (2014). Let’s CHAT: Cultural historical activity theory in the creative writing classroom. New Writing, 11(3), 438–451. doi:10.1080/14790726.2014.956123

- Edwards, A., & Daniels, H. (2004). Using sociocultural and activity theory in educational research. Educational Review, 56(2), 107–111. doi:10.1080/0031910410001693191

- encountersIvanic R. (2004). Discourses of writing and learning to write. Language and Education, 18(3), 220–245. doi:10.1080/09500780408666877

- Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki: Orienta-Konsultit.

- Engeström, Y. (1999). Activity theory and individual and social transformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Engeström, Y., & Sannino, A. (2011). Discursive manifestations of contradictions in organisational change efforts: A methodological framework. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 24(3), 368–387. doi:10.1108/09534811111132758

- Erling, E. J., Seargeant, P., Solly, M., Chowdhury, Q. H., & Rahman, S. (2012). Attitudes to English as a language for international development in rural Bangladesh. London: British Council. Available online at: https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/sites/teacheng/files/B497%20ELTRP%20Report%20Erling_FINAL.pdf

- Ganobcsik-Williams, L. (Ed.). (2006). Teaching academic writing in UK higher education: Theories, practices and models. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. doi:10.1007/978-0-230-20858-2

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Giles, T. M., Gilbert, S., & McNeill, L. (2014). Nursing students’ perceptions regarding the amount and type of written feedback required to enhance their learning. Journal of Nursing Education, 52(1), 23–30. doi:10.3928/01484834-20131209-02

- Graham, S., MacArthur, C. A., & Fitzgerald, J. (2013). Best Practices in Writing Instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

- Groleau, C., Demers, C., Lalancette, M., & Barros, M. (2012). From hand drawings to computer visuals: Confronting situated and institutionalised practices in an architecture firm. Organization Science, 23(3), 651–671. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0667

- Hasan, H., & Kazlauskas, A. (2014). Activity Theory: who is doing what, why and how. In H. Hasan (Ed.), Being Practical with Theory: A Window into Business Research (pp. 9–14). Wollongong, Australia: THEORI.

- Heeneman, S., & de Grave, W. (2017). Tensions in mentoring medical students toward self-directed and reflective learning in a longitudinal portfolio-based mentoring system – an activity theory analysis. Medical Teacher, 39(4), 368–376. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2017.1286308

- Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (2011). Research on second language teacher education: A sociocultural perspective on professional development. New York: Routledge.

- Kabir, A. H. (2012). Neoliberal hegemony and the ideological transformation of higher education sector in Bangladesh. Critical Literacy: Theories and Practices Journal, 6(2), 2–15.

- Kim, E. (2011). Ten Years of CLT curricular reform efforts in South Korea: An activity theory analysis of a teacher’s experience. New York: Routledge.

- Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning: Recent advances. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural Theory and the Genesis of Second Language Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lantolf, J. P., & Thorne, S. L. (2007). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An Introduction, Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah (pp. 201–224). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Lea, M., & Stierer, B. (2009). Lecturers’ everyday writing as professional practice in the university as workplace: New insights into academic identities. Studies in Higher Education, 34(4), 417–428. doi:10.1080/03075070902771952

- Lea, M., & Street, B. (2000). Student writing and staff feedback in higher education: An academic literacies approach. In M. R. Lea & B. Stierer (Eds.), Student writing in higher education. New Contexts (pp. 32–46). Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Leki, I., & Carson, J. G. (1997). Completely different worlds: EAP and the writing experiences of ESL students in university. TESOL Quarterly, 31, 39–70. doi:10.2307/3587974

- Leont’ev, A. N. (1981). The problem of activity in psychology. In J. V. Wertsch (Ed.), The concept of activity in Soviet psychology (pp. 37–71). Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, Inc.

- Lim, C. P., & Hang, D. (2003). An activity theory approach to research of ICT integration in Singapore schools. Computers and Education, 41(1), 49–63. doi:10.1016/S0360-1315(03)00015-0

- Linell, P. (2009). Rethinking language, mind, and world dialogically: interactional and contextual theories of human sense-making. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing.

- Maharsi, I. (2007). The Academic Writing Experience of Undergraduate Industrial Technology Students in Indonesia. In Global Perspectives, Local Initiative (pp. 145–158). National University of Singapore.

- McCafferty, S. G., Roebuck, R. F., & Wayland, R. P. (2001). Activity theory and the incidental learning of second-language vocabulary. Language Awareness, 10(4), 289–294. doi:10.1080/09658410108667040

- Mercer, N. (2008). Talk and the development of reasoning and understanding. Human Development, 51(1), 90–100. doi:10.1159/000113158

- Mitchell, J. C. (1984). Case studies. In R. F. Ellen, (eds.) Ethnographic research: A guide to general conduct (pp. 237–241). Orlando, FL: Academic Press, Inc.

- Montoro, C., & Hampel, R. (2011). Investigating language learning activity using a CALL task in the self-access centre. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(3), 119–1inter. doi:10.37237/020303

- Musa, M. (1996). Politics of language planning in Pakistan and the birth of a new state. International Journal of the Sociology of Language, 118(1), 63–80. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1996.118.63

- Mustaque, S. (2014). Writing problems among the tertiary level students in Bangladesh: A study in Chittagong Region. Language in India, 14, 327–391.

- Newman, M. (2002). The designs of academic literacy: A multiliteracies examination of academic achievement. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- Nichol, J., & Blake, A. (2013). Transforming teacher education, an activity theory analysis. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(3), 281–300. doi:10.1080/02607476.2013.799846

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Prosser, M., & Trigwell, K. (1999). Understanding learning and teaching: The experience in higher education. Buckingham: SRHE Open University Press.

- Reigeluth, C. M., & Moore, J. (1999). Cognitive education and the cognitive domain. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-design theories and models, Volume 2 (pp. 51–68). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Roshid, M. M. (2014). Pragmatic strategies of ELF speakers: A case study in international business communication. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Russell, D. R. (2009). In: Uses of activity theory in written communication research. Learning and expanding with activity theory. H. D. A. Sannino and K. Gutierrez, (eds). New York:Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511809989.004.

- Sheppard, S., Macatangay, K., Colby, A., & Sullivan, W. M. (2008). Educating engineers: Designing for the future of the field. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Smagorinsky, P. (2015). Designing the task of teaching novice teachers to design instructional tasks. Designing tasks in secondary education: Enhancing subject understanding and student engagement. I. Thompson. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315755434-11

- Storch, N. (2004). Using activity theory to explain differences in patterns of dyadic interactions in an ESL class. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 60(4), 457–480. doi:10.3138/cmlr.60.4.457

- Stuart, C. D. D. (2012). Succeeding through uncertainty: Three L2 students in a first-year composition class. University of Washington: ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Sullivan, W. M., Colby, A., Wegner, J. W., Bond, L., & Shulman, L. S. (2007). Educating lawyers: Preparation for the profession of law. San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.

- Sundet, R. (2010). Therapeutic collaboration and formalised feedback: Using perspectives from Vygotsky and Bakhtin to shed light on practices in a family therapy unit. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(1), 81–95. doi:10.1177/1359104509341449

- Thompson, I. (2012). Planes of communicative activity in collaborative writing. Changing English, 19(2), 209–220. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2012.680766

- Uddin, M. E. (2014). Teachers’ pedagogical belief and its reflection on the practice in teaching writing in EFL tertiary context in Bangladesh. Journal of Education & Practice, 5(116). doi:10.19044/ejes.v1no3a5

- University Grants Commission. (2011). Poitrishtomo Barshik Protibedon . Dhaka: UGC.

- van Lier, L. (2008). Ecological-semiotic perspectives on educational linguistics. In F. M. Hult, (ed.) The Handbook of Educational Linguistics. B. S. a (pp. 596–604). Malden: Blackwell.

- Virkkunen, J., & Newnham, D. S. (2013). The Change Laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychologicalprocesses. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Werder, C., & Otis, M. M. (2010). Engaging student voices in the study of teaching and learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Whitehead, D. (2002). The academic writing experiences of a group of student nurses: A phenomenological study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 38(5), 498–506.

- Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2014). Activity systems analysis methods: Understanding complex learning environments. New York: Springer.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research design and methods (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Yoon, B., & Kim, H. K. (2012). Teachers’ roles in second language learning: Classroom applications of sociocultural theory. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

- Yu, L. (2015). Reexamining motive in L2 oral proficiency development: An activity theory perspective. Language and Sociocultural Theory, 2(1), 85–117. doi:10.1558/lst.v2vi1.22201

- Zheng, D., & Newgarden, K. (2011). Rethinking language learning: Virtual worlds as a catalyst for change’. International Journal of Learning and Media, 3(2), 13–36. doi:10.1162/ijlm_a_00067