ABSTRACT

As phenomena, time, and history, particularly the nature of the two and how to tell them apart, are not easily defined. In the tradition of historical consciousness, time, and the human understanding of the nature of time are defined as a part of a historical consciousness, where this may more or less evolved. In this study, students aged 11 were interviewed and asked what history and time are. Their answers consisted in three different ways of describing the nature of time: time as events, time as a continuous now, and time as continuous progress. How students described time was then compared to Rüsen’s (Rüsen, Retzlaff, & Wiklund, 2004; Rüsen, 2005) definitions of historical consciousness. The ability of younger children to understand time has been an issue debated in previous research. This study concludes that time and concept of time is understood by eleven-year-olds but in various forms. These various forms are essential knowledge for history teachers at all levels. There is evidence for historical consciousness, as described by Rüsen, however, in forms appropriate for their age.

Introduction

Time and the nature of time are of central interest to history as a school subject; yet, how to define time in the history classroom is somewhat unclear. Time and history, as concepts, intersect or overlap but do not always converge. This article presents primary students’ ways of reasoning about time and is followed by a discussion about understanding time and students’ historical consciousness.

An understanding of time and chronology has been defined as part of the concept of historical consciousness (Rüsen, Retzlaff, & Wiklund, Citation2004). The concept of historical consciousness is difficult to operationalise and, thereby, to study as such- how does one study a consciousness? – therefore only expressions of historical consciousness can be studied (Ammert, Citation2008; Sandberg, Citation2018; Thorp, Citation2014).

The aim of this article is to present how students in school year five describe what time is and what distinguishes time from history. The students’ perceptions are discussed in terms of historical consciousness based on Rüsen, Retzlaff, and Wiklund (Citation2004). The research questions examine:

-How do students aged eleven define time and then time and history?

-What does their concept of time say about their historical consciousness?

This article contributes to an ongoing discussion about students’ conceptions of time, which has implications for the teaching of history and history as a school subject.

The article first touches on various notions about time, such as time as a phenomenon and the understanding of time, followed by a brief overview of previous research on time and students. The method employed for the interviews and an outline of the theoretical starting point for a discussion of the results are presented. This is followed by a presentation of ways students in my material expressed time. The article concludes with a discussion about students’ understanding of time based on previous research and as part of their historical consciousness and, finally, what this means for teaching history as a school subject.

Background

The concept of time

Closely related to the perception of time as a concept is the perception of time as a process, a succession of events that often move forward in the sense that humans and their circumstances develop towards a better future (Barton, Citation2008; Lee & Ashby, Citation2000). Ricœur (Citation1985) described three parts of time – past, present, and future – as belonging to the consciousness of a modern society that focused on future and future society, whereas the perception of time before the Enlightenment was of an ongoing “now” that rested on a past. With modernism, time vanished more quickly and history itself was perceived to go faster. This experience was reinforced by the subsequent two centuries of industrialisation, urbanisation, and world wars (Clark & Grever, Citation2018). Another way of understanding time is “episode time”: the intuitive feeling that time goes faster when many things happen and slower when we are bored (Forman, Citation2015). Understanding clock time was considered to be linked to understanding historical time and was previously seen as too difficult for children to grasp (Piaget, Citation1968).

Several concepts within history didactics, in both Anglo-American and continental didactics traditions, are based on a consciousness of time, of chronology. To understand change and continuity, an understanding of chronological time needs to exist (Wilschut, Citation2012). Developing historical consciousness requires an understanding of time and that humans and society exist in a time continuum (Thorp, Citation2014). To be able to think like a historian, there needs to be an understanding of distance in time (Wineburg, Citation2001). In other words, an understanding of chronological time is central to history didactics.

Previous research

As mentioned above Piaget (Citation1968) concluded that a notion of time and the maturity to understand time developed at the earliest at the age of eight. Barton and Levstik (Citation1996) showed that children younger than eight could sort pictures in chronological order without knowing time concepts connected to clock time, entailing that past, present, future, and clock time do not have to be linked (Barton & Levstik, Citation1996; Wilschut, Citation2012). However, children in the study tended to relate the images to their own time and not to other time periods (Barton & Levstik, Citation1996). In a follow-up study, Barton (Citation2002) showed that children between the ages of six and twelve used four different strategies to place the images in chronological order: referring to their own experiences, referring to facts they knew, or, if they lacked those tools, looking for signs of change between the pictures, and, finally, placing one picture and putting the others in relation to that picture. Barton (Citation2002) regarded the strategies as cultural tools children had learned; teaching should therefore focus on providing students with a context and presenting the different time periods involved in the material being studied in relation to each other. In a more recent Swedish study previous results were replicated, and students defined time as long ago or very long ago. They could distinguish between different time-periods in history and did not see it as a constant “past”. Even young children use a past tense that consists of mutually different time periods of long ago and even longer ago (Clark & Grever, Citation2018; Rudnert, Citation2019; Solé, Citation2019). However, the notion that historical consciousness is something students mature into by themselves seems to be an accepted wisdom among teachers (Hartsmar, Citation2001).

In a similar study, children thought paintings were always older than photographs, and judged things that were dusty and worn as older than things that looked clean and whole. This reflects a perception of history as a constant development from worse to better, the children reasoned about what had changed in terms of comparing what they had to what people did not have before (de Groot-Reuvekamp, Ros, van Boxtel, & Oort, Citation2017).

Material

Students from six different schools in central Sweden were interviewed in spring the year they turned eleven. One school was situated in a very rich suburb of a big city, an old, esteemed school surrounded by large villas inhabited by residents with high incomes. Another school was in an area with rental apartments in high-rise buildings where more than half of the residents were born outside Europe and almost as many did not have permanent jobs. Two of the schools were in middle-class areas in a larger city. One school was in a small industrial town that had lost many jobs in recent years and in which many residents were new immigrants. Another school was located far out in the countryside, and the last school was in a small community where most residents worked in the nearby industry. The schools were selected to include students from a wide variety of socio-economic backgrounds. All schools were municipal schools to ensure that the students came from the schools’ immediate catchment areas.

The students were interviewed in pairs or in small groups of a maximum five students. Two students were interviewed individually. Group interviews were chosen to ensure that I, as an adult, would not be too dominant and with a hope that interaction between the students would yield richer discussion and reasoning compared to the students being interviewed alone. We met at the students’ schools and interviews took place without any supporting material; students were not shown pictures or objects associated with history. The interviews were semi-structured, follow-up questions varied, but the interviews had a common basic structure (Kvale, Citation1997).

Ethics

All students received written and oral information about the study, and their guardians received written information. Informed consent was obtained from students and their guardians, all students who volunteered and obtained guardian consent were interviewed. In addition, no questions of a private nature were asked, and the students could cease participation at any time. No personal data was collected, and all reproductions of the interviews have been anonymised. In total, I interviewed around 70 students as a part of my research for my dissertation and other results from the interviews are published there (Sandberg, Citation2018). In this text, time, an aspect that weren’t elaborated in the thesis, is studied.

Methodology

An interview is always an exchange of perspectives and thoughts. The interviewer’s task is to interpret the interviewees’ perspectives based on the interviewer’s understanding of these perspectives (Kvale, Citation1997).

The questions

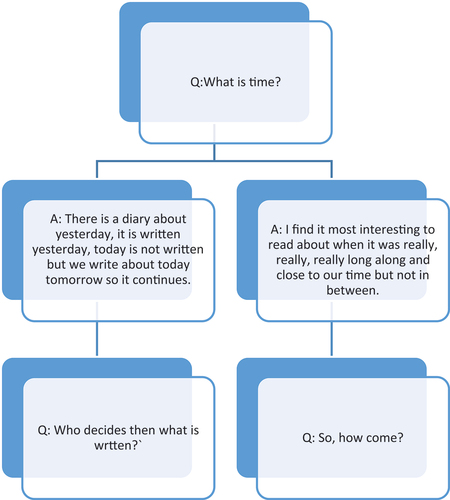

As mentioned above, this text is based on material that to a large extent were left out of the thesis since the aim of the thesis concentrated on students’ historical culture. The questions asked were about time, about what was more recent or more remote history, how distance in time could be understood, and how they had been taught about these things. The questions this text is based on were part of a lager sections of questions and the material selected here had two start questions: What is time and what is history? Depended on the answers the students where then asked how they would define these two, what makes it time respectively, what makes it history? Then they were asked if time and history were linked to one another, and if so, how. Since the interviews were semi-structured follow up questions differed but took similar paths in most of the interviews. The structure of the interviews can be illustrated in the following manner as can be seen in :

As can be seen here, the students interpret my question in two different ways, one speaks about the nature of time, the other about study history. Hence, they are put into different categories, one of what time is as a phenomenon and the other in time as the content of history as a school subject. In the latter is the temporal use of “really, really long ago”, “close to our time” and “between” is interesting but not focus of this text.

Analysis

The analysis followed the phases that characterise thematic analysis. The first phase involved acquainting myself with the material. During this phase, the interviews were transcribed in their entirety, I also listened to them several times. Simultaneously with the transcription, notes were kept on things I found regarding time and the nature of time. The second phase involved generating initial codes and organise the material under these (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). Concretely, this meant that I read through the transcribed interviews. At the same time, I underlined key parts of the texts, noted words of support or codes in the margin, and noted these initial codes and central parts. After that, all quotations, summaries, and initial interpretations were collected under these codes. The third phase involved sorting, analysing, and shaping the codes into categories and these were described and illustrated with quotations. The different categories were colour-coded. The fourth phase involved reviewing and refining these themes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). The fifth phase consisted of defining, naming and further refining the categories presented in the study and analysing the material within them.

Categorization

The material was coded according to the most prominent themes in the material. Three different ways of identifying time were discovered in students’ responses, the coding was conducted according to this scheme ():

Table 1. Categorization scheme

The process was repeated with all three categories. These categories were then related to Rüsen’s, Retzlaff, and Wiklund (Citation2004) concept of historical consciousness and can therefore be defined as deductive, critical, constructionist thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). Throughout, the process was discussed with peers and presented at seminars.

Theory

The narrative of time

When children encounter history, it often takes the form of narrative (Levstik & Thornton, Citation2018). Narrative has been seen as one of the pillars of historical consciousness Rüsen, Retzlaff, & Wiklund, Citation2004. Ricœur (Citation1985) argued that narrative is the first form of time consciousness. For a narrative to be acceptable, the end and the beginning must differ in time, and there must be events in chronological order leading to the ending. Narratives do not linger on how long the events take; the actors in the story complete their actions regardless of time (Ricœur, Citation1985). When applied to history, history becomes a story that has no connection with time, as the narrative allows for detachment from this. Time also has a narrative function as a marker for something associated with the past, from the biblical “It happened at that time” (Luke 2:1) to the fairy tale “Once upon a time”.

Time and historical consciousness

Historical consciousness is seen as universal, as it is assumed to be a prerequisite for human societies (e.g. Nordgren, Citation2019). Nordgren (Citation2019) addresses two different definitions of historical consciousness: one associated with a developed, or modern, society and one that is associated with cultural memory, the latter being what Rüsen (Citation2005) considers all human societies create. Nordgren (Citation2019) points to epistemological and ontological issues involved with the concept: firstly, there is the question of how teaching should be conducted in order for students to develop their historical consciousness; secondly, the didactic questions What? and Why? encounter difficulties with the concept. This means that the theory of historical consciousness needs to be tested empirically. In line with Grever and Adriaansen (Citation2019), this article treats historical consciousness as a part of historical culture. Research about historical consciousness has in the last few years been, at least in Sweden, widely studied, and also discussed (e.g. Alvén, Citation2011, 2017; Andersson Hult, Citation2016, Stymne, Citation2017; Nordgren, Citation2019; Rosenlund, Citation2011; Rudnert, Citation2019; Sandberg, Citation2018; Silfver & Myyry, Citation2022; Thorp, Citation2014; Wibaeus, Citation2010) In Contemplating Historical Consciousness Anna Clark and Clara Peck (Citation2018) give an overview over the current research of the concept, both in the Anglo- American countries as well as European ones.

The Swedish curriculum, steering document for Swedish compulsory school, states that students’ historical consciousness should be developed through history as school subject (Skolverket, Citation2022). A formulation suggesting that historical consciousness can be developed, and history as a school subject should support and help students develop their historical consciousness Historical consciousness, then, is considered part of some “higher good” schooling should impart to students (Thorp, Citation2014). A developed historical consciousness is also seen as linked to a developed ethical and moral consciousness (Rüsen, Retzlaff, & Wiklund, Citation2004; Ammert, 2010). Historical consciousness is not viewed as static but changes with age and new experiences (Körber, Citation2015).

Rüsen (Citation2005) divided historical consciousness into four stages: traditional, exemplary, critical, and genetic. This division has since been further developed by several theorists of history didactics, mainly in Germany (Andersson Hult, Citation2016). These four stages, or levels of historical consciousness, will be used as a starting point for describing the students’ historical consciousness. Rüsen (Citation2005) defined six expressions of historical consciousness in relation to his typology, of which the perception of time is one:

Traditional historical consciousness leans towards tradition: things are as they are because they have always been or are meant to be so. Here, the perception of time is that it is an obligatory repetition of traditions, and time itself is seen as both cyclical and mathematical.

Exemplary historical consciousness sees history as stories – often moral stories – to be learned. The exemplary historical consciousness sees history as a series of events that explain why the present looks the way it does, and the stories of events related as underlying the present do not necessarily have to be true but, rather, serve primarily as signposts for the future.

Critical historical consciousness is critical in that it questions stories that form the basis of the present as well as the basic premise that history can function as an adviser or that it is possible to draw conclusions about contemporary processes based on past events. This view also questions norms and established truths. Time is, in this perception, a representation of what is to be questioned; the present is created as a reaction to the past.

Finally, genetic historical consciousness is based on the previous stages. Here historical statements and facts are governed by the historical context in which they take place. Emphasis is on a chronological development through explanations of cause and effect, change and continuity.

Rüsen (Citation2005) seems to deem these stages based on each other, the latter ones focus mainly on the future, and the way history is perceived depends on what questions are asked. My use of this typology has been inspired by Andersson Hult (Citation2016).

The categories identified in the material are: Event time is dependent on events. Actors are important to some extent, but they are not prominent. Students with this perception of history often reason in terms of before and after. An occasion in history is indicated by naming whether it occurred before or after a certain event. In the interviews the words history, event, and time as used as synonyms by the students. The future is not visible in the students’ responses, history has “ended”. Momentary time is closer to a narrative conception of history, “story” is used interchangeably with “history” and “time” in the interviews. This is the least used form of the perception of time in the interviews and is only mentioned in a few interviews. However, these interviews are not concentrated to one school, but occurs in three out of six schools. It differs from the other two perceptions of time is that it only involves the immediate history. In the final perception of time, time is progress, students drew connections over rather long timespans and saw that time itself has changed history – time was defined as a chain of progress. The difference between time is progress and event time is that time is progress is an ongoing process that will continue into the future. In time as events, events in the past have a direct impact on the present, distance in time has no effect on the impact of the event in the perception of time as events. This was the second most common perception and was identified on five out of six schools. The future was most prominent in this perception.

Results

Even though the students came from differing backgrounds, no differences were discovered between students from separate schools; the differences that emerged were solely at individual level. The categories formed below applies to the entire group of students. What can be noted is that the students at more privileged schools mentioned being exposed to history through visits to museums and reading fiction, whereas the students in the less privileged areas and in the smaller towns stated that they only encountered history in school.

Regarding how they had been taught about time and history, students answered that they did not know or that they had not received any instruction. It is noteworthy that the students only mentioned years on a few occasions in the interviews and only exceptionally eras such as the Stone Age. They also did not indicate time in the form of multitude concepts such as “thousands of years ago”, time was divided into past, present, and future, which in themselves constituted equal units. The students did not make any great distinction between different parts of the past: it was a unit, often just called “the past” in the answers.

Event time. The first form of perception of time is “event time”. Students saw time as a series of events stacked on top of each other, not necessarily with connections between events. History consists of events, and there are examples of students believing that, without events, history does not happen – time then ceases to exist to a certain extent, and similar lives and days are repeated indefinitely. Time as a cosmic phenomenon and as organic processes would continue but not time in the sense that anything would really change. I see this form of perception of time as closely connected with a narrative perception of history. Time and history are narratives stacked on top of each other. This also means that time in different narratives is not significant. It is the event itself that is important. These events also constitute history, as an event is historical content. In this conception of time, those events, insofar as they affect other events, constitute a direct influence on the present. Time that elapsed has no effect on how the event affects or does not affect the present. To read about events is to read history, and time or times are different events in the past – a perception close to the’ “once upon a time” of fairy tales, the narrative is hence strong in the students’ perception of time. Time is perceived to a certain extent as a constant stream in which events take place. This is similar to the results of previous studies (Levstik & Thornton, Citation2018; Wilschut, Citation2019).

Contra-factual descriptions are common, the students discuss how things might have been if a specific event had not taken place. Inventions, of both things and ideas, are also regarded as events and themselves have changed the direction of events and therefore time and history.

These quotes illustrate this notion of time:

If one thing changes, a lot of things happen that happen or have happened.

If the meteorite had missed Earth, dinosaurs would have existed, and we would not have existed or would have been pets.

Then it might have hit another planet, and there would have been earthquakes and chaos, and we would not have lived in a house but in a cave in the ground.

If I had gone back in time and stopped Stockholm bloodbath […]. So, the Vasa period would never have started. What would have been then? What would have happened then? Would we have been living as they did then, or?

Part of this perception of time is also students’ perception that history begins when discernible events can be studied. According to the students, studying the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age means studying how people lived, and it is not synonymous with history because those times do not contain what they consider to be major events (for example interviews 2.3, 4.3, 4.1). Time is measured in events. Students also make a distinction between the past that contains events and the past consisting of peoples’ everyday lives, which they see as non-history. According to the students, education in the future will have problems teaching history, as current and future events must be included in history as a school subject.

This quote points to a beneficial aspect of knowing history, and illustrates a perception that events in the past have a direct impact on the present:

think the Vasa period will be great fun because I have been to the Vasa Museum and have seen the Vasa ship, and I think it is so exciting with how it turned out and that it is still there because it can also help the story. Because it sank, because there were too many cannons on one side and then people now know that if we build such a ship, it must be even, because otherwise it will [sink].

If we move on to Rüsen’s categories, exemplary historical consciousness is prominent in this category. The students often emphasised that it is possible to learn from history, even events far back in time. Critical historical consciousness is visible where the students reasoned that the present builds upon the past and the future will continue to do so. Critical historical consciousness is present in the meaning that history can function as an adviser or that it is possible to draw conclusions about contemporary processes based on past events, however, there are not, yet, any critical questions to the past from the students. Traditional historical consciousness is visible in that things are as they are because they have always been or are meant to be so. Events are time in the sense that only events “drive” history.

Momentary time, the second form is time as a constant now, a now that disappears at the same moment that it occurs, and this perception was future oriented – the past is time that has passed and not of much interest. Nor was the future interesting because the students did not perceive themselves as actors in time: time passes, and they cannot influence its development. I call this “momentary time”. This is also similar to earlier results in studies (Hartsmar, Citation2001).

Students in this category sees time as moments that constantly replace each other. We as humans are trapped in time and history, as we are involved in events that take place but have little impact on the events and cannot influence them to any extent. The impact history has on the present and the future is experience-based, practically oriented, and individual. There are examples of transmission from one generation to another but not over longer timespans than that.

In this quote, three students discuss what the past can be and what can be learned from the past. Most interestingly, they did not see history as extending beyond their own lifetimes or any person’s lifetime. In the quote, the students reasoned from a position based on the way an individual’s experiences can affect how they act in the future:

History can also be what you did yesterday […] If you climb up a climbing wall without a harness and fall after a while and if you do not remember the story then you would fall down a thousand times.

If you do not kill yourself if it is a high wall.

The bus is something I’m thinking about. If you arrive late to the bus, you will learn to not do it again. If you are a driver of a ferry and collide […], then there are a lot of people sitting on it and then they know that “I will not go here again because then I will have a collision”. Then you use [history] with others. Or it could be walking across the road, or someone drives through a red light, and then you get hit or almost hit and then you have risked your life just because you crossed the road.

In this quote, the temporal definition of history is visible – everything is history, and history is synonymous with time passed:

It’s really all the time, for history is, well, really what happened two seconds ago, it is history.

Like it was history a year ago, in the past.

History is all the time. What I am saying now is history in a few seconds.

Those who saw history as momentary time could only learn from their own past experiences or from others who had told them about their experiences; however, it was not possible, in their eyes, to learn from more distant past. Those who saw history as a flow of moments can also, to some extent, be seen possessing a traditional historical consciousness, as they saw history as a constant repetition, however, students who expressed momentary time were not at all connected with the past or the future, as they did not see more distant history as affecting the present or the future. Learning from history was present in the students’ reasoning, but they saw themselves as actors only in a short-term perspective and could thus, in principle, only learn from the immediately preceding generations. There are examples of exemplary historical consciousness but only covering short time spans. This notion of time is also visible in previous research, especially among younger students (Barton & Levstik, Citation1996; Rudnert, Citation2019).

Time as progress. The third form is time as a linear narrative of progress. Unlike event time, this can almost be described as a belief in fate, where human history is seen as a predetermined series of events, insights, and inventions that lead to people and circumstances getting better, I have named this “time is progress”, this notion is also discernible in previous studies (Barton & Levstik, Citation1996; Barton, Citation2002; Wilschut, Citation2012). Time, history, and progress are used as synonyms by the students in this category.

As in the first conception of time above, students are not actors in this development. Development is inevitable and human existence is constantly getting better, a movement from worse to better. The future, according to the students, will continue this movement. In this category, the perspective of time extends beyond the students’ own lifetimes. Inventions are based on previous inventions. Also, there is a notion that the future will look up us as undeveloped:

Interviewer: If we are smarter and faster today, in 500 years will they think we think we are stupid?

Yes it probably will because we think they were kind of stupid in the old days.

You ran to another country to deliver a letter. [In the past]

I think about that a lot.

Then maybe they have chips in their heads instead of mobile phones and think we’re dumb who had a mobile phone in our hands all the time.

Furthermore, this perception of time regards history as consisting of constant progress and as almost predetermined. They see some problems with environmental degradation, but otherwise the future means further improvements. These improvements also apply morally; the idea of progress also applies to the humanity, even if technological development is empathised.

In this form, time is present primarily as a structure on which the present rests and the future will build on. In this quote, the students draw a line from fire to electricity:

Very useful, because if Edison had not invented light bulbs, then we would not have lights and him, or her, who invented electricity, I do not remember what their name was, then we would not have electricity. We would not be able to build houses or have electric cars or game consoles. Lots of things we would not have. Most of it goes on electricity nowadays.

[…]

So like when they came up with how to make fire – then we can make fire because they could do it, and so it has continued from fire to electricity.

Progress is emphasised and the meaning of history is to have knowledge of that process.

Interviewer:You talked about development, what has developed?

It’s kind of like from humans running around naked in a forest and something like this with a stick to what we have today that we wear clothes go to school, have work, trades, shop, because they had to find their food, butcher it and then eat it, we can call a drive thru, talk, get food and then it’s all over.Interviewer:Why have we evolved then?

Because we are not (…)

Because it was monkeys who took the first step and then it’s just progressed, you come up with new things and they come up with things in turn and more new things and then there are other things.

After all, you can’t build a car without a factory.

And you can’t build a farm without machines, like this if, you can’t build machines without tools and you can’t build tools without materials.

Everything must come from the animal kingdom and the plant kingdom.

From a monkey.

From nature.

We develop more and more, and it is important to know how we have developed.

YesInterviewer:Why?

For …

Now you get to say.

For then, we know how we can develop more.[…] Interviewer:Will we continue to develop in the future?

Probably.

The following quote gives an example of students seeing that injustices in the past remain but in a different form. However, they still see a development from past to present and to the future:

It’s pretty awful as in Viking times that women were not worth as much. It’s the same now but, it’s like this, that men still get much more pay than women get and it’s still very unfair, I think.

And that if you could not pay taxes, you had to be a slave. They were treated very badly like that.[…]

Yes.

We make progress, by seeing how they do [things].

It will be like that all the time.

The students who saw time as progress had the characteristic of a critical historical consciousness, as the students saw that different historical events are based on each other and that conclusions were based on previous events. They also believed that people in the future will look at the present in the same way that they, the students, now view the past, that the future will contain changes from the present. Critical historical consciousness is visible also in the sense that the present builds upon the past and the future will continue to do so. Some critical questions are directed to the past, mostly revolving why people in the past did things “wrong”. Also, exemplary historical consciousness is noticed since the student see history as instructions of lessons to be learned.

Discussion

What does it mean to exist in time? It is quite easy to establish that the students did not express time in terms of distance but more as an alienation from people who lived in the past. In the students’ answers, history and time are synonymous: my questions about time were interpreted as questions about history and vice versa. This might be explained by the format of the interviews. I let the students’ own thoughts lead in the interviews and did not give definitions of words or concepts before or during the interviews. The word “story” is also used by the students.

The results ranged from time as a phenomenon to how time and history are inextricably linked, as the students only sparingly mentioned time in the sense of clock time, and the students saw time and history as united. Events are what history consists of. What differed in the students’ understanding was whether they saw events as the force that drove time forward or, rather, time as a stream unaffected by events. In the latter understanding of time, time was not synonymous with history as understood by the students.

The historical consciousness the students expressed was rather undeveloped, which is to be expected in such young children. What needs to be thought about, however, is how we as history educators might go from establishing and examining the students’ historical consciousness to deciding how teaching should be conducted for historical consciousness to develop. Students are taught about a past, a future, and a present they have recently begun to make their own. The concept of historical consciousness is based on that the three time units are handled simultaneously, which can be difficult to reconcile with understanding time distances and being able to contextualise events that happened “in the past”. This study makes clear that more research is needed, mainly to understand how children’s notions of time and history are related and affect one another. The concept of historical consciousness talks about existence in time – but what is time?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karin Bergman

Karin Bergmanre received PhD in didactics and a senior lecturer in the subject since the beginning of 2019. His research interest is mainly children’s democratic upbringing through school, with a particular interest in history as school subject and history didactics. He participate in a research project on gender equality in schools and I am interested in museum education materials and how it is used in history teaching.

References

- Alvén, F. (2011). Historiemedvetande på prov: En analys av elevers svar på uppgifter som prövar strävansmålen i kursplanen för historia. [Historical consciousness to the test: An analysis of students’ answers that test the goals in the curriculum for history as a school subject]. Lund: [Licentiatavhandling, Historia]. Forskarskolan i historia och historiedidaktik, Lunds universitet.

- Ammert, N. (2008). Det osamtidigas samtidighet: historiemedvetande i svenska historieläroböcker under hundra år [To Bridge Time: Historical Consciousness in Swedish History Textbooks During the 20th Century] [ Doctoral dissertation, Lund University]. Sisyfos Förlag.

- Andersson Hult, L. (2016). Historia i bagaget: en historiedidaktisk studie om varför historiemedvetande uttrycks i olika former [Having a history: a study in history didactics on the origins of various expressions of historical consciousness] Doctotal dissertation, Umeå University.

- Barton, K. C. (2002). “Oh, that’s a tricky piece!”: Children, mediated action, and the tools of historical time. The Elementary School Journal, 103(2), 161–185. doi:10.1086/499721

- Barton, K. C.2008.Visualizing Time.Eds., Researching history education: Theory, method and contextpp. 61–70. Routledge. 10.4324/9781315088815-4

- Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (1996). “Back when god was around and everything”: Elementary children’s understanding of historical time. American Educational Research Journal, 33(2), 419–454. doi:10.3102/00028312033002419

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (Vol. 2, pp. 57–71). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- Clark, A., & Grever, M. (2018). Historical consciousness. In Eds., S. A. Metzger & L. M. Harris The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 177–201). doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch7

- Clark, A., & Peck, C. (2018). Introduction: Historical Consciousness: Theory and Practice. doi:10.1002/9j.ctvwbhk.5

- de Groot-Reuvekamp, M., Ros, A., van Boxtel, C., & Oort, F. (2017). Primary school pupils’ performances in understanding historical time. Education 3–13, 45(2), 227–242. doi:10.1080/03004279.2015.1075053

- Forman, H. (2015). Events and children’s sense of time: A perspective on the origins of everyday time-keeping. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 6. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00259

- Grever, M., & Adriaansen, R.-J. (2019). Historical consciousness: The enigma of different paradigms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(6), 814–830. doi:10.1080/00220272.2019.1652937

- Hartsmar, N. (2001). Historiemedvetande: elevers tidsförståelse i en skolkontext. [Consciousness of history. Pupils’ understanding of time in a school context.] Diss. Lund: Univ. Malmö.

- Körber, A., (2015). Historical consciousness, historical competencies – and beyond? Some conceptual development within German history didactics.

- Kvale, S. (1997). Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Lee, P., & Ashby, R. (2000). Progression in historical understanding among students ages 7–14. In P. N. Stearns, P. Seixas, & S. Wineburg (Eds.), Knowing, teaching and learning history: National and international perspectives (pp. 199–222). New York: New York University Press.

- Levstik, L., & Thornton, S. (2018). Reconceptualizing history for early childhood through early adolescence. In Eds., S. A. Metzger & L. M. Harris The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 473–501). doi:10.1002/9781119100812.ch18

- Nordgren, K. (2019). Boundaries of historical consciousness: A Western cultural achievement or an anthropological universal? Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(6), 779–797. doi:10.1080/00220272.2019.1652938

- Piaget, J. (1968). Barnets själsliga utveckling. Gleerup. [Six psychological studies. New York: Random House. 1967.

- Ricœur, P. (1985). Time and narrative (Vol. 2). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Rosenlund, D. (2011). Att hantera historia med ett öga stängt. Samstämmighet mellan Historia a och lärares prov och uppgifter. [Handling history with one eye shut: Alignment between standards and assessment in upper-secondary history education.] Lund: Forskarskolan i historia och historiedidaktik. Malmö: Lunds universitet, Malmö högskola.

- Rudnert, J. (2019). Bland stenyxor och Tv-spel: om barn, historisk tid och när unga blir delaktiga i historiekulturen [Among stone axes and video games: on children, historical time and when children become participants in cultural history]. Malmö university, Fakulteten för lärande och samhälle.

- Rüsen, J. (2005). History: Narration, interpretation, orientation. Berghahn Books.

- Rüsen, J., Retzlaff, J., & Wiklund, M. (2004). Berättande och förnuft: historieteoretiska texter. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Sandberg, K. (2018). Att lära av det förflutna: Yngre elevers förståelse för och motivering till skolämnet historia. [To learn from the past- younger pupils´ understanding of and motivation for history as a school subject] Diss. Eskilstuna: Mälardalens högskola. Eskilstuna.

- Silfver, M., & Myyry, L. (2022). Integrating historical and moral consciousness in history teaching. Historical Encounters, 9(2), 18–29. doi:10.52289/hej9.203

- Skolverket (2022). Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2011: reviderad 2022 [Curriculum for grammar school, kindergarten, and youth recreation centres 2011: revised 2022]. Swedish National Agency for Education.

- Solé, G. (2019). Children’s understanding of time: A study in a primary history classroom’.History. Education Research Journal, 16(1), 158–173. doi:10.18546/HERJ.16.1.13

- Stymne, A. (2017). Hur begriplig är historien?: elevers möjligheter och svårigheter i historieundervisningen i skolan.[Making History Understandable : Problems and Possibilities Facing Students When Learning History] Diss. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet.

- Thorp, R. (2014). Towards an epistemological theory of historical consciousness. Historical Encounters: A Journal of Historical Consciousness, Historical Cultures, and History Education, 1(1), 20–31.

- Wibaeus, Y. (2010). Att undervisa om det ofattbara. En ämnesdidaktisk studie om kunskapsområdet Förintelsen i skolans historieundervisning. [To Teach the Inconceivable: A study of the Holocaust as a field of knowledge when taught and learnt in upper and upper secondary school. Doktorsavhandlingar från Pedagogiska Institutionen nr. 170. Stockholm: Stockholms Universitet.

- Wilschut, A. (2012). Images of time: The role of an historical consciousness of time in learning history. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Pub.

- Wilschut, A. (2019). Historical consciousness of time and its societal uses. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(6), 831–849. doi:10.1080/00220272.2019.1652939

- Wineburg, S. S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.