?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Background: Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is one of the prevalent forms of trauma experienced during childhood and adolescence. Previous research underscores its associations with depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and psychosis.

Objective: This study examined symptom connections between depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis while simultaneously investigating whether these connections differed by gender among CSA survivors.

Methods: A large-scale, cross-sectional study among 96,218 college students was conducted in China. Participants’ CSA was measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF). Participants’ PTSD, psychosis, depression, and anxiety were measured by the Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ), the Psychosis Screener (PS), the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7), respectively. Network analysis was used to explore the potential associations between these symptoms and to compare the sex differences in the symptoms model.

Results: Among participants who suffered from CSA, females were more likely from left-behind households, while males were more likely from households with a high annual income (P < .001, Cohen’s W = 0.07). In addition, compared to male victims, female victims were more likely to report depression, anxiety, and PTSD (P < .001, Cohen’s d≈0.2), while male victims were more likely to report psychosis (P < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.36). Results from network estimation showed that psychosis, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms were positively correlated. Moreover, psychosis had a stronger connection with PTSD symptoms, including hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, and physiological and emotional reactivity.

Conclusions: The current study explores the associations between PTSD symptoms and psychiatric symptoms among college students exposed to CSA using a network analysis approach. These crucial symptoms of PTSD may have potential connections to psychosis. Target intervention and strategy should be developed to improve mental health and quality of life among these CSA victims. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are warranted to advance our understanding of PTSD and psychosis.

HIGHLIGHTS

The current study examined associations between PTSD symptoms and other psychiatric symptoms among sexual abuse victims using network analysis.

Male victims were more likely to have psychosis.

Female victims were more likely to report depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

Psychosis had stronger connections with PTSD symptoms, including hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, and other symptoms.

Antecedentes: El abuso sexual infantil (CSA, por sus siglas en inglés) es una de las formas predominantes de trauma experimentado durante la niñez y la adolescencia. Investigaciones anteriores subrayan su asociación con la depresión, la ansiedad, el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) y la psicosis.

Objetivo: Este estudio examinó las conexiones de los síntomas de depresión, ansiedad, TEPT y psicosis mientras investigaba simultáneamente si estas conexiones diferían según el género entre los sobrevivientes de CSA.

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio transversal a gran escala entre 96218 estudiantes universitarios en China. El CSA de los participantes se midió mediante el Cuestionario de Trauma Infantil-Versión Corta (CTQ-SF). El TEPT, la psicosis, la depresión y la ansiedad de los participantes se midieron mediante el Cuestionario de detección de trauma (TSQ), el Detección de psicosis (PS), el Cuestionario de salud del paciente de nueve ítems (PHQ-9) y la Escala de trastorno de ansiedad generalizada de 7 ítems. (GAD-7), respectivamente. Se utilizó el análisis de redes para explorar las asociaciones potenciales entre estos síntomas y para comparar las diferencias, según sexo, en el modelo de síntomas.

Resultados: Entre los participantes que sufrieron CSA, las mujeres eran más propensas a pertenecer a hogares abandonados*, mientras que los hombres eran más propensos a pertenecer a hogares con un ingreso anual alto (P < .001, W de Cohen = 0.07). Además, en comparación con las víctimas masculinas, las víctimas femeninas tenían más probabilidades de reportar depresión, ansiedad y TEPT (P < .001, d de Cohen ≈0,2), mientras que las víctimas masculinas tenían más probabilidades de informar psicosis (P < .001, d de Cohen = 0.36). Los resultados de la estimación de la red mostraron que psicosis, depresión, ansiedad y síntomas del TEPT estaban correlacionados positivamente. Además, la psicosis tenía una conexión más fuerte con los síntomas del TEPT, incluida la hipervigilancia, los pensamientos intrusivos y la reactividad fisiológica y emocional.

Conclusiones: El estudio actual explora las asociaciones entre los síntomas de TEPT y los síntomas psiquiátricos entre estudiantes universitarios expuestos a CSA utilizando un enfoque de análisis de red. Los síntomas del TEPT, que incluyen hipervigilancia, pensamientos intrusivos y reactividad fisiológica y emocional, pueden tener una conexión potencial con la psicosis. Se deben desarrollar intervenciones y estrategias específicas para mejorar la salud mental y la calidad de vida entre estas víctimas de CSA. Además, los estudios longitudinales garantizan un avance en nuestra comprensión del TEPT y la psicosis.

背景:童年期性侵害 (CSA) 是童年期和青春期经历的普遍创伤形式之一。前人研究强调了它与抑郁、焦虑、创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 和精神病的关系。

目的:本研究考查抑郁、焦虑、PTSD和精神病之间的症状联系,同时考查这些联系在 CSA 幸存者中是否因性别而异。

方法:在中国进行了一项针对96,218名 大学生的大规模横断面研究。参与者的 CSA 由儿童创伤问卷 – 简表 (CTQ-SF) 测量。参与者的 PTSD、精神病、抑郁和焦虑分别通过创伤筛查问卷 (TSQ)、精神病筛查问卷 (PS)、九条目患者健康问卷 (PHQ-9) 和七条目广泛性焦虑障碍量表进行测量(GAD-7)。使用网络分析探究这些症状之间的潜在关联,并比较症状模型中的性别差异。

结果:在遭受CSA的参与者中,女性更可能来自留守家庭,而男性更可能来自年收入高的家庭(P < .001,Cohen’s W = 0.07)。此外,与男性受害者相比,女性受害者报告抑郁、焦虑和 PTSD(P < .001,Cohen’s d≈0.2)可能性更高,而男性受害者更可能报告精神病(P < .001,Cohen’s d = 0.36 )。网络估计的结果表明,精神病、抑郁、焦虑和 PTSD 症状呈正相关。此外,精神病与 PTSD 症状有更强的联系,包括高警觉、侵入性思维以及生理和情绪反应。

结论:本研究使用网络分析方法探讨了遭受CSA 大学生的 PTSD 症状与精神症状之间的关联。PTSD症状,包括高警觉、侵入性思维以及生理和情绪反应,可能与精神病有潜在联系。应制定有针对性的干预措施和策略,以改善这些 CSA 受害者的心理健康和生活质量。此外,有必要进行纵向研究以促进我们对 PTSD 和精神病的理解。

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is considered as one of the prevalent forms of child and adolescent trauma. According to the World Health Organization, sexual abuse against children and adolescents refers to the involvement in sexual activity and other law-violating actions for which children and adolescents often do not comprehend, are not developmentally prepared, and are unable to provide informed consent (World Health Organization, Citation1999, Citation2017). Globally, the prevalence of CSA-related experiences varies drastically across countries and gender, ranging from 6% to 45% on a global scale (Vila-Badia, Citation2021). The deleterious health effects of CSA often persist throughout the lifetime, including but not limited to a higher susceptibility to risky sexual behaviours, conduct disorder, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and severe psychosis (Fisher, Citation2013; Hardy et al., Citation2021; Isvoranu, Citation2017). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have explored that exposure to CSA is a significant risk factor for PTSD, regardless of the gender of the victim and the severity of abuse (Maniglio, Citation2013; McTavish et al., Citation2019). PTSD symptoms involve the persistent re-experience of the traumatic event through recurrent and intrusive recollections of the event, repetitive dreams of the event or frightening dreams without recognizable content, flashbacks of the traumatic event, feeling as if the traumatic event was recurring, and/or intense psychological distress or physiologic reactions at exposure to trauma cues (Hornor, Citation2010). It is possible that PTSD symptoms might not appear right away after the sexual assault but instead appear months or even years later. PTSD may cause behaviours that are detrimental to the individual’s life. PTSD also medicated the relation between CSA, adverse health outcomes, and non-suicidal self-injury (Eadie et al., Citation2008; Weierich & Nock, Citation2008).

A larger number of studies have investigated the relationship between CSA, PTSD, and psychosis (Chatziioannidis, Citation2019). Findings from previous research reported that those with a history of sexual abuse are at risk of developing disturbances involving emotion regulation, interpersonal relationships, and self-concept, which are considered essential pieces of criteria for ‘complex PTSD’ (World Health Organization, Citation2019). In support of the affective pathway to psychosis, most research demonstrated that CSA was connected to the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis through symptoms of general psychopathology (Alameda, Citation2021; Bloomfield, Citation2021). These findings underline the potential utility of examining the interactions between psychosis and PTSD (Hardy et al., Citation2021; Isvoranu, Citation2017; Liotti & Gumley, Citation2008). Moreover, increasing evidence from large population-based and prospective studies supports the notion of a causal relationship between the experience of CSA and psychosis risk (Fisher, Citation2013; Misiak, Citation2017). Growing meta-analytical research also accentuated the associations between developmental trauma and psychosis via PTSD, dissociation, and emotional dysregulation (Alameda, Citation2021; Bloomfield, Citation2021; Matheson et al., Citation2013; Varese, Citation2012). Childhood trauma, such as sexual abuse, has been shown to be associated with more severe clinical psychotic symptoms and consistently higher severity of both psychotic experiences and symptoms over time (Garcia, Citation2016; Trotta et al., Citation2015). A meta-analysis also found that there was a significant association between sexual abuse and psychosis across all research designs, with an overall effect of OR = 2.38 (95% CI: 1.98–2.87, P < .001) (Varese, Citation2012). According to current evidence, the key trauma-related psychological mechanisms involved in psychosis are intrusive trauma memories, beliefs, as well as cognitive, behavioural, and interpersonal emotion regulation (Alameda, Citation2021; Bloomfield, Citation2021; Hardy, Citation2017; Matheson et al., Citation2013; Varese, Citation2012). Although numerous pathways for trauma-related processes have been studied in the literature, little is known about their connections to psychosis.

Network analysis would be useful for elucidating which PTSD symptoms are heavily related to psychosis. Network analysis could address symptoms’ complexity since it argues that psychological issues are caused by dynamic feedback loops constituted by different components rather than a common latent variable (Epskamp et al., Citation2018; van Borkulo et al., Citation2016). Different from the biomedical paradigm that claims that one central monolithic latent element (the disorder) causes all the symptoms, the current psychological network approach suggests that the disorder is constituted by a system of interconnected and interacting symptoms (e.g. one cannot be depressed without depressed mood) (Borsboom, Citation2017). As a result, the disorder may be a complex network of symptoms that interact with one another and may even reinforce one another during those interactions. Additionally, network analysis provides a novel exploratory method for examining how variables interact with each other while highlighting noteworthy intervariable interactions in the network (Di Blasi, Citation2021). One advantage of this method is that relationships between variables are taken into account based on partial correlations or predictive values between the researched variables (Hevey, Citation2018). When network analysis is used in a cross-sectional study, it can explore the central variables that might trigger and maintain other factors while investigating associations between variables (Borsboom & Cramer, Citation2013). Previous research has explored the association between PTSD and psychosis among CSA victims. One network analysis found that CSA was connected to the positive and negative symptoms of psychosis through symptoms of general psychopathology (Isvoranu, Citation2017). Another study also found that hypervigilance was a bridge symptom between PTSD and psychotic symptoms (Hardy et al., Citation2021). Dissociative amnesia, visual intrusions, and physical reactions also play key roles in the network among CSA survivors (Kratzer, Citation2020).

Few studies have explored gender and sex differences in the prevalence of CSA and its consequences on PTSD and psychosis. A cross-sectional study among 733 college students found that female students with a CSA history were more likely to report greater PTSD symptom severity than male students with a CSA history (Ullman & Filipas, Citation2005). Other studies on psychosis found that significantly more female than male patients had experienced CSA (Sweeney et al., Citation2015), despite the fact that other studies could not confirm this result (Garcia, Citation2016; Vila-Badia, Citation2021). Another community sample study found that adolescence-onset and duration of sexual abuse respectively predicted anxiety and PTSD in females but not males, whereas the severity of sexual abuse was associated with PTSD symptoms in males but not females (Merza et al., Citation2017). Moreover, depression and anxiety were suggested as common comorbid disorders with PTSD and psychosis in CSA victims (Gottlieb et al., Citation2011; Molnar et al., Citation2001). The evidence is substantial that CSA is a risk factor for a wide range of psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis (Janssen, Citation2004; Shrivastava et al., Citation2017). However, there are no studies specifically investigating symptom relationships between psychopathology and PTSD among college students who were exposed to CSA. To address such a critical gap in clinical literature, the present study examined symptom connections between depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosis while simultaneously investigating whether these connections differed by sex among CSA survivors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and settings

This study was part of a large-scale, cross-sectional study among college students conducted online between 26 October and 18 November 2021 in Jilin province, China. All 63 universities and colleges in this province were invited to the study. A Quick Response code (QR Code) linked to the introduction, invitation, and questionnaire was distributed by all the colleges and then forwarded to students. Eligibility inclusion criteria included: (1) aged above 16 years; (2) studying in universities or colleges in Jilin province, China; (3) able to understand the assessment content and Chinese. Jilin University granted ethical approval for this study. Electronic informed consent was obtained online from all participants.

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Childhood sexual abuse (CSA)

Childhood sexual abuse (CSA) was measured by the validated Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) (He et al., Citation2019), which was originally developed by Bernstein et al. (Bernstein, Citation2003). The CTQ-SF consists of 28 items, and each item was scored from ‘1’ (never true) to ‘5’ (very often true). This scale assesses five domains of childhood abuse and neglect: sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and emotional neglect. Each type of abuse or neglect was categorized by summing up the scores for related questions. The recommended clinical cutoff score of sexual abuse ≥ 8 was used to determine whether participants suffered from CSA.

2.2.2. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms

Participants’ PTSD symptoms were measured by the Trauma Screening Questionnaire (TSQ) (Brewin, Citation2002), which has been validated in the Chinese version (Jiang, Citation2018). The TSQ is a 10-item self-rated instrument that contains five re-experiencing items (e.g. ‘Upsetting dreams about the event’) and five arousal items (e.g. ‘Difficulty falling or staying asleep’). It was adapted from the PTSD Symptom Scale-Self-Report Version (PSS-SR) (Foa et al., Citation1993). The TSQ is a validated screening tool for PTSD with a sensitivity and specificity score of 0.85 and 0.89, respectively (Walters et al., Citation2007). The reference names of ten items are listed in Table S1.

2.2.3. The psychosis screener

The presence of psychosis was assessed using the validated Chinese version of the Psychosis Screener (PS), which was adapted based on the core elements of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Schizophrenia module. The PS consists of 7 items, three of which were asked if the respondent endorsed a previous question. Each item was scored 1 when an individual responded ‘Yes.’ The final item asked whether a doctor had told the person they might have schizophrenia. The recommended clinical cutoff cumulative score of 3 or more was used to identify cases of psychosis with 82% of sensitivity and 57% of specificity for diagnosing schizophrenia (Degenhardt et al., Citation2005).

2.2.4. Depression and anxiety

The severity of depressive symptoms was measured using the Chinese version of the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001). Each item was scored from ‘0’ (not at all) to ‘3’ (nearly every day), with a higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms. The validity of the PHQ-9 has been well established in the Chinese population (Wang & Chen, Citation2014; Zhang, Citation2013). The severity of anxiety symptoms was measured using the Chinese version of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (Garabiles, Citation2020; Spitzer et al., Citation2006), which comprises seven items with each score from ‘0’ (not at all) to ‘3’ (nearly every day). Higher scores indicate more severe anxiety symptoms.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using the R program, version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, Citation2020). Participants’ sociodemographic variables such as residence, ethnicity, and only-child status were analyzed by chi-square test between males and females. The Rao-Scott chi-square tests with 1 degree of freedom were then used for bivariate comparisons in variables such as family types and annual income. The continuous variables were analyzed by t-test to compare the difference between sex. The effect sizes of the chi-square test and t-test were also calculated to understand the magnitude of differences found (Sullivan & Feinn, Citation2012).

2.3.1. Network estimation

The network model for all variables (i.e. PTSD, depression, anxiety, psychosis) was estimated among the participants exposed to CSA. The association between each item was computed with a polychronic correlation. The Graphical Gaussian Model (GGM) with the graphic least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) and the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) model were performed using the R package ‘qgraph’ (Epskamp et al., Citation2012). The nodes represented symptoms, while the edges represented the associations between these symptoms. The thickness of edges represented the strength of association between nodes. The colour of the edge indicates the direction of the correlations (e.g. green edges represented positive correlations; red edges represented negative correlations) (Epskamp et al., Citation2012). Expected influence (EI) was calculated to explore the central symptoms in the network. The EI represented the summed weight of all its edges, including positive and negative associations with its immediate neighbour nodes in the network (Borsboom, Citation2017; Spiller, Citation2020).

Moreover, networks’ shortest pathways between PTSD symptoms and psychosis were computed. Compared with the first network, the second network explicitly identified possible pathways between PTSD and psychosis. The shortest path between two nodes was calculated using Dijkstra’s method and represents the smallest number of steps required to travel from one node to the other. The R packages named ‘NetworkTools’ (version 4.0.2) (R Core Team, Citation2020) were used to perform the analyses (Epskamp et al., Citation2012).

2.3.2. Network accuracy and stability

Three procedures were used to assess the accuracy and stability of the network model. First, the accuracy of edge weights was estimated by computing confidence intervals (CIs) with a non-parametric bootstrapping method (Chernick, Citation2011). Then, the primary dataset was resampled randomly to create new datasets from which the 95% CIs were calculated. According to the sorting of bootstrapped mean edge weights, we could find whether the edge weights of the total sample are consistent with the bootstrapped sample. Second, the correlation stability coefficient (CS-C) was calculated to assess the stability of the EI using subset bootstraps (Costenbader & Valente, Citation2003; Epskamp et al., Citation2018). The CS-C measured the maximum proportion of cases that can be dropped such that the correlation would reach a certain value with a 95% probability. Generally, the CS-C should not be less than 0.25 and preferably above 0.5. Third, bootstrapped difference tests were performed to evaluate differences in the network’s properties (Epskamp & Fried, Citation2018). This test relied on 95% CIs, to determine if two edge-weights or two-node centrality indices significantly differed. The bootstrap procedure and the overall stability were calculated using the ‘bootnet’ R-package version 4.0.5.

2.3.3. Network comparison

A permutation test was performed to examine statistical differences among the networks between males and females with CSA history. This methodology assessed the difference in network structure (e.g. distributions of edge weights), global strength (e.g. the absolute sum of all edge weights of the networks), and each edge between the two networks (i.e. females versus males) using Holm–Bonferroni correction of p values due to multiple tests (Van Borkulo, Citation2017). After these testing, the significant edge differences for each pair of groups were plotted. These tests were performed with the R-package ‘NetworkComparisonTest’ version 4.0.5 (van Borkulo et al., Citation2016).

3. Results

3.1. Study sample

96,218 participants fulfilled the study entry criteria and completed the assessment (40,065 males and 56,153 females). Among the 96,218 participants, 3,479 reported CSA experiences. The sample prevalence of CSA was 3.62% (95% CI: 3.50–3.73%), while the prevalence of CSA in females was 3.17% (95% CI: 3.03–3.32%) and in males was 4.24% (95% CI: 4.05–4.44%). The sociodemographic characteristics of participants who experienced SA are listed in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of participants who experienced CSA.

Among participants who suffered from CSA, females were more likely from left-behind households, while males were more likely from households with a high annual income (P < .001, Cohen’s W = 0.07). Moreover, the total scores of PHQ-9, GAD-7, PTSD-10, and psychosis were also significantly different (P < 0.001) between males and females with a CSA history. While female victims were more likely to report depression (Cohen’s d = 0.23), anxiety (Cohen’s d = 0.24), and PTSD (Cohen’s d = 0.16), male victims were more likely to have psychosis (Cohen’s d = 0.36).

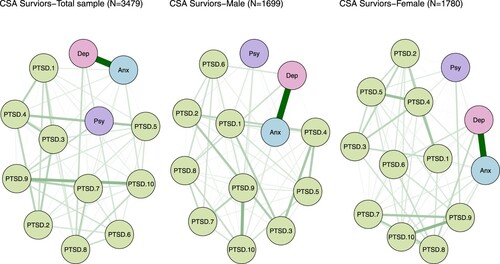

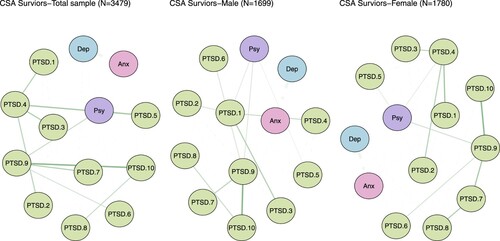

3.2. Network estimation and centrality analysis results

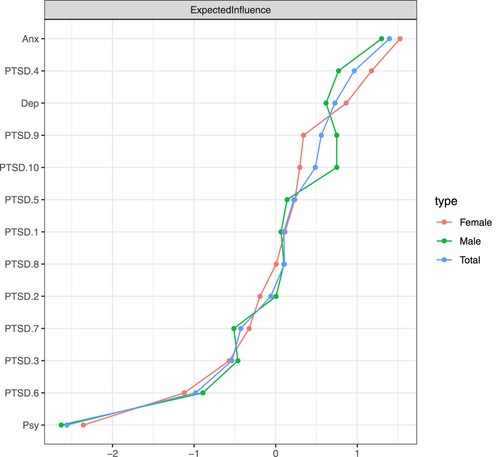

The network estimation among the total participants in the CSA sample, including males and females, was displayed in . These results showed that psychosis, depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptoms were positively correlated. In the total CSA sample, the node ‘Anxiety’ had the highest strength centrality, followed by the PTSD-4 ‘Emotional cue reactivity’ and ‘Depression.’ In the associations between PTSD symptoms and psychosis, psychosis had stronger connections with PTSD-9 ‘Hypervigilance,’ PTSD-5 ‘Physiological cue reactivity,’ and PTSD-4 ‘Emotional cue reactivity’ (). The strongest edges in the CSA sample and female sample included ‘Depression" – ‘Anxiety,’ PTSD-9 ‘Hypervigilance’ – PTSD-10 ‘Exaggerated startle response,’ and PTSD-4 ‘Emotional cue reactivity’ – PTSD-5 ‘Physiological cue reactivity.’

Figure 1. Symptom networks of the total sample (N = 3479), male (N = 1699) and female (N = 1780) exposed to CSA.

Note: Anx: Anxiety; Dep: Depression; Psy: Psychosis; PTSD.1: Intrusive thoughts; PTSD.2: Nightmares; PTSD.3: Flashbacks; PTSD.4: Emotional cue reactivity; PTSD.5: Physiological cue reactivity; PTSD.6: Sleep disturbance; PTSD.7: Irritability/anger; PTSD.8: Difficulty concentrating; PTSD.9: Hypervigilance; PTSD.10: Exaggerated startle response.

Figure 2. Symptom pathways between PTSD and psychosis among the total sample (N = 3479), male (N = 1699), and female (N = 1780) exposed to CSA.

Note: Anx: Anxiety; Dep: Depression; Psy: Psychosis; PTSD.1: Intrusive thoughts; PTSD.2: Nightmares; PTSD.3: Flashbacks; PTSD.4: Emotional cue reactivity; PTSD.5: Physiological cue reactivity; PTSD.6: Sleep disturbance; PTSD.7: Irritability/anger; PTSD.8: Difficulty concentrating; PTSD.9: Hypervigilance; PTSD.10: Exaggerated startle response.

In female participants who experienced CSA, psychosis was more likely to connect with PTSD-9 ‘Hypervigilance,’ PTSD-4 ‘Emotional cue reactivity,’ and PTSD-5 ‘Physiological cue reactivity.’ In addition, among male participants who experienced CSA, psychosis had stronger association with PTSD-9 ‘Hypervigilance,’ PTSD-1 ‘Intrusive thoughts,’ and PTSD-5 ‘Physiological cue reactivity.’ These results were consistent with the total CSA sample in the female sample. In the male sample, the node ‘Anxiety’ also had the highest EI centrality, followed by PTSD-4 ‘Emotional cue reactivity’ and PTSD-9 ‘Hypervigilance’ ().

3.3. Network accuracy and centrality

The bootstrap 95% CI for edges and bootstrapped differences tests for edge weight were shown in Supplementary Figure S1, and the results of estimation of edge weight difference by bootstrapped difference test were shown in Supplementary Figure S2. The bootstrap difference test estimated node strength difference (Supplementary Figure S3). The edge weights in the three samples were consistent with the bootstrapped sample, especially for the association with larger weights. These results indicated a stable network model among three symptom networks. The case-dropping subset bootstrap procedure showed that the EI value remained stable even after dropping large proportions of the sample (Figure S4). The EI showed an excellent level of stability (CS-C = 0.75) among the three groups.

3.4. Network comparison tests for sex

The comparison of network models between female (n = 1780) and male (n = 1699) participants with CSA history showed no significant differences in the network global strength (network strength: 5.38 in male participants; 5.49 in female participants; S = 0.12, p = .111) and edge weights (M = 0.08, p = 0.591; Supplementary Figure S6). These results indicated the association between depression, anxiety, psychosis, and PTSD symptoms were similar between male and female participants who experienced CSA.

4. Discussion

The current study investigates symptom associations between PTSD symptoms and psychiatric symptoms and compares the sex differences among CSA victims using a network analytic approach. The prevalence of CSA among the total sample was 3.62% (95% CI: 3.50–3.73%), with the prevalence of CSA in females was 3.17% (95% CI: 3.03–3.32%) and in males was 4.24% (95% CI: 4.05–4.44%). There were significant differences in the CSA prevalence between male and female victims. Among participants who suffered from CSA, females were more likely from left-behind households, while males were more likely from households with a high annual income (P < 0.001). In addition, female CSA victims were more likely to report depression, anxiety, and PTSD compared to male CSA victims, while male CSA victims were more likely to have psychosis compared to female CSA victims. Moreover, compared to other symptoms, psychosis had stronger connections with PTSD symptoms, including hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, and physiological and emotional reactivity.

Our results found that female CSA victims were more likely to be from left-behind families when compared with male CSA victims. This result was consistent with previous studies conducted in China (Wang et al., Citation2020; Zhao et al., Citation2018). Rural family separation in China has resulted in a huge number of ‘left-behind’ youngsters who were exposed to high risks of CSA. Failure and insufficient tutelage as a result of parental migration into cities and peculiar rural living environments (e.g. drab and confined habitats) could potentially be the key contributors to the high risks of sexual abuse against left-behind children. Several studies have reported that family environment, such as whether children lived with both parents during childhood, was related to the risk of CSA (Vogeltanz, Citation1999). Thus, increasing attention should be paid to left-behind children. Our results also revealed that female CSA victims were more likely to report depression, anxiety, and PTSD, while male CSA victims were more likely to have psychosis. These results were in line with former studies. A 24-month follow-up study found that more childhood trauma was related to higher levels of depression in women and to negative symptoms in men among patients with first-episode of psychosis (Pruessner, Citation2019). Men were more sensitive to psychosis, according to research on the neural diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia (Pruessner et al., Citation2017), as evidenced by reduced hippocampal volume and attenuated Hypothalamus-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis reactivity (Pruessner, Citation2008; Pruessner et al., Citation2013). In this regard, it has been argued that greater estrogen levels in women have a protective effect on psychosis by modulating the hormonal response to stress (Handa & Weiser, Citation2014), which might explain why males have a shorter disease course (Häfner, Citation2003). However, several studies reported the connection between sexual abuse and psychosis was stronger in females (Bebbington, Citation2011; Myin-Germeys et al., Citation2004). For instance, Fisher and her colleagues found that severe sexual abuse was associated with psychosis in women but not in men (Fisher, Citation2009). Longitudinal studies should be conducted to explore the differences in the connection between PTSD and psychosis in males and females.

According to our results from the symptoms network model, we found that in the total CSA sample, psychosis had stronger connections with PTSD symptoms, including hypervigilance, physiological and emotional reactivity, and intrusive thoughts. These findings are in line with a previous study in which they also found that hypervigilance was a bridge symptom between PTSD and psychotic symptoms (Hardy et al., Citation2021). Adversity in childhood has been linked to a reduction in hippocampus volume (Teicher et al., Citation2012). In patients with psychosis, adversity in childhood has also been linked to a blunted HPA axis response. Hypervigilance is an abnormal level of activation that develops after traumatic or highly stressful experiences. Hypervigilance can be characterized by elevated levels of stress hormones like norepinephrine and cortisol, as well as a change in the number or sensitivity of stress hormone receptors (Kendall-Tackett, Citation2000). With exposure to high quantities of stress hormones, hypervigilance may potentially stimulate certain brain areas, such as the hippocampus. Through sensitization, hyperarousal can make victims of prior traumatic events more vulnerable to current life pressures. The brain develops threat-sensitized after experiencing traumatic situations (McCarty & Gold, Citation1996). When confronted with a new stressor, the body ‘remembers’ the previous incident and overreacts. The trauma-genic neurodevelopmental model provides a neurobiological pathway that leads from early trauma to negative symptoms via hyperarousal and the biological stress system (Read et al., Citation2001). All these factors and actions have been suggested as potential symptoms of psychosis, especially among the victims of CSA (Fisher, Citation2013; Hardy et al., Citation2021; Isvoranu, Citation2017). According to our results of the shortest pathways in the network analysis, physiological and emotional reactivity and intrusive thoughts are also linked to psychosis, such as feeling upset by reminders of the event and bodily reactions (e.g. fast heartbeats and stomach churning). This could result from the activation of beliefs in autobiographical memory, which subsequently leads to trauma-related emotions and physical responses. Similarly, hyperarousal and intrusive thoughts were suggested as central symptoms in a large sample with PTSD (Fried, Citation2018). Another three-year follow-up study on 311 military veterans with PTSD also reported intrusive memories with negative emotions and beliefs were the most prominent symptoms (von Stockert et al., Citation2018). However, previous studies found that re-experiencing and dissociative detachment in hallucinations play a key role in explaining the link between trauma and psychosis (Chapman, Citation1984; Vila-Badia, Citation2021). These inconsistencies with previous results might be due to methodological differences across structural equation modelling (SEM), logistic regression, and network analysis and population differences across patients with severe PTSD or psychosis, military personnel, and college students. Nevertheless, consistent with previous studies, no significant differences in the psychotic symptoms model between sex have been found in the present study.

Furthermore, although several symptoms such as dissociation and hallucinations were not measured in this study, they also play crucial roles between PTSD and psychotic disorders in CSA survivors (Anglin et al., Citation2015; Bentall, Citation2014; Kratzer, Citation2018; O’Neill et al., Citation2021; Varese et al., Citation2012). For instance, both theoretical and empirical studies have proposed a specific relationship between CSA and hallucinations in which dissociation plays a mediating role (Bentall, Citation2014; Kratzer, Citation2018; Varese et al., Citation2012). Additionally, there are also a number of studies emphasizing that the associations between CSA and psychotic symptoms might be both directly and indirectly explained by dissociative processes (Anglin et al., Citation2015; O’Neill et al., Citation2021). As for the measure of dissociation, the most widely used scales are the Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES and DES-II) (Bernstein & Putnam, Citation1986; Carlson & Putnam, Citation1993), which consists of 28 items that are used to screen dissociative symptoms. Nevertheless, when it is used with nonclinical populations, the resulting scores would show severe floor effects and often are highly skewed (Wright & Loftus, Citation1999). Other scales also claim to measure dissociation specifically, such as the Wessex Dissociation Scale (WDS) with 40 items (Kennedy, Citation2004), the Dissociative Symptoms Scale (DSS) with 20 items (Carlson, Citation2018), the Multidimensional Inventory of Dissociation (MID) with 218 items (Dell, Citation2006), and Multiscale Dissociation Inventory (MDI) with 30 items (Briere et al., Citation2005). However, due to the application of PTSD symptoms screening instrument (TSQ) in the general population, particularly in this large-scale study with 117,248 respondents, the specific instruments for CSA survivors might not be suitable for our study. Therefore, the specific instruments for CSA survivors might not be suitable for our study because the participants in this study belong to the general population. The application of the PTSD symptoms screening instrument (TSQ) in this large-scale study among 117,248 respondents would be more suitable. In the future, we plan to conduct a study with specific instruments for dissociation in CSA survivors to address this question.

Several limitations of the present study should be taken into consideration. First, the CSA is a self-report, retrospective measure of sexual abuse and may thus be prone to bias (i.e. social desirability, memory bias, and demand characteristics). Second, the presence of psychosis was assessed by the PS. Although this brief screening instrument is effective for discriminating whether the general population suffers from psychotic disorders, it cannot be used to diagnose or determine the specific types of psychotic disorders due to its relatively low specificity. More accurate assessment of psychotic disorders requires the application of semi-structured or structured instruments such as the Structured Clinical Interview, DSM-IV, and ICD-10 (Steinberg, Citation1994; World Health Organization, Citation2019). Third, due to the cross-sectional design, the causation between PTSD and psychosis symptoms cannot be confirmed. Fourth, results cannot be extended to a nationwide scale because only participants from Jilin province were enrolled. Fifth, the present study’s objectives only included (1) examining the associations between PTSD symptoms and psychosis and (2) providing suggestions based on our findings. Therefore, the possible correlations between PTSD, depression, anxiety, and psychosis were not examined, an important area warranting attention from future studies.

In conclusion, the current study explores the association between psychosis and PTSD symptoms among college students exposed to CSA using network analysis. Symptoms of PTSD, such as hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, and physiological and emotional reactivity, might have a potential connection with psychosis. Target intervention and strategy should be developed to improve mental health and quality of life among these CSA victims. Furthermore, longitudinal studies, including neurocognitive assessments, should be conducted to advance the understanding of the biopsychosocial mechanisms underlying the association between PTSD and psychosis in CSA victims.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (225.4 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The dataset and R code for this specific manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alameda, L. (2021). Association between specific childhood adversities and symptom dimensions in people with psychosis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 47(4), 975–985. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa199

- Anglin, D. M., Polanco-Roman, L., & Lui, F. (2015). Ethnic variation in whether dissociation mediates the relation between traumatic life events and attenuated positive psychotic symptoms. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(1), 68–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.953283

- Bebbington, P. (2011). Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: Data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083642

- Bentall, R. P. (2014). From adversity to psychosis: Pathways and mechanisms from specific adversities to specific symptoms. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(7), 1011–1022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0914-0

- Bernstein, D. P. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Bernstein, E. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174(12), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004

- Bloomfield, M. A. P. (2021). Psychological processes mediating the association between developmental trauma and specific psychotic symptoms in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 20(1), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20841

- Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375

- Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

- Brewin, C. R. (2002). Brief screening instrument for post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Psychiatry, 181(2), 158–162. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.2.158

- Briere, J., Weathers, F. W., & Runtz, M. (2005). Is dissociation a multidimensional construct? Data from the Multiscale Dissociation Inventory. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(3), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20024

- Carlson, E. B. (2018). Development and validation of the dissociative symptoms scale. Assessment, 25(1), 84–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116645904

- Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation: progress in the dissociative disorders.

- Chapman, L. J. (1984). Impulsive nonconformity as a trait contributing to the prediction of psychotic-like and schizotypal symptoms. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 172(11), 681–691. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-198411000-00007

- Chatziioannidis, S. (2019). The role of attachment anxiety in the relationship between childhood trauma and schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis. Psychiatry Research, 276, 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.05.021

- Chernick, M. R. (2011). Bootstrap methods: A guide for practitioners and researchers. John Wiley & Sons.

- Costenbader, E., & Valente, T. W. (2003). The stability of centrality measures when networks are sampled. Social Networks, 25(4), 283–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-8733(03)00012-1

- Degenhardt, L., Hall, W., Korten, A., & Jablensky, A. (2005). Use of a brief screening instrument for psychosis: Results of an ROC analysis. National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.

- Dell, P. F. (2006). The multidimensional inventory of dissociation (MID): A comprehensive measure of pathological dissociation. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 7(2), 77–106. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v07n02_06

- Di Blasi, M. (2021). Psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 lockdown: A two-wave network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 284, 18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.016

- Eadie, E. M., Runtz, M. G., & Spencer-Rodgers, J. (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms as a mediator between sexual assault and adverse health outcomes in undergraduate women. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(6), 540–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20369

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

- Fisher, H. (2009). Gender differences in the association between childhood abuse and psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(4), 319–325. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047985

- Fisher, H. L. (2013). Pathways between childhood victimization and psychosis-like symptoms in the ALSPAC birth cohort. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 39(5), 1045–1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs088

- Foa, E. B., Riggs, D. S., Dancu, C. V., & Rothbaum, B. O. (1993). Reliability and validity of a brief instrument for assessing post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490060405

- Fried, E. I. (2018). Replicability and generalizability of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) networks: A cross-cultural multisite study of PTSD symptoms in four trauma patient samples. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(3), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617745092

- Garabiles, M. R. (2020). Psychometric validation of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in Filipino migrant domestic workers in Macao (SAR), China. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(6), 833–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1644343

- Garcia, M. (2016). Sex differences in the effect of childhood trauma on the clinical expression of early psychosis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 68, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2016.04.004

- Gottlieb, J. D., Mueser, K. T., Rosenberg, S. D., Xie, H., & Wolfe, R. S. (2011). Psychotic depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and engagement in cognitive-behavioral therapy within an outpatient sample of adults with serious mental illness. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(1), 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.04.012

- Häfner, H. (2003). Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28(Suppl. 2), 17–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0306-4530(02)00125-7

- Handa, R. J., & Weiser, M. J. (2014). Gonadal steroid hormones and the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35(2), 197–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.11.001

- Hardy, A. (2017). Pathways from trauma to psychotic experiences: A theoretically informed model of posttraumatic stress in psychosis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 697. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00697

- Hardy, A., O’Driscoll, C., Steel, C., van der Gaag, M., & van den Berg, D. (2021). A network analysis of post-traumatic stress and psychosis symptoms. Psychological Medicine, 51(14), 2485–2492. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001300

- He, J., Zhong, X., Gao, Y., Xiong, G., & Yao, S. (2019). Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) among undergraduates and depressive patients. Child Abuse & Neglect, 91, 102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.009

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2018.1521283

- Hornor, G. (2010). Child sexual abuse: Consequences and implications. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 24(6), 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.07.003

- Isvoranu, A. M. (2017). A network approach to psychosis: Pathways between childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(1), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbw055

- Janssen, I. (2004). Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 109(1), 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0001-690X.2003.00217.x

- Jiang, W.-J. (2018). Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form for inpatients with schizophrenia. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208779. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208779

- Kendall-Tackett, K. A. (2000). Physiological correlates of childhood abuse: Chronic hyperarousal in PTSD, depression, and irritable bowel syndrome. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(6), 799–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00136-8

- Kennedy, F. (2004). Towards a cognitive model and measure of dissociation. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 35(1), 25–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.01.002

- Kratzer, L. (2018). Mindfulness and pathological dissociation fully mediate the association of childhood abuse and PTSD symptomatology. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 2(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2017.06.004

- Kratzer, L. (2020). Sexual symptoms in post-traumatic stress disorder following childhood sexual abuse: A network analysis. Psychological Medicine, 52(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720001750

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Liotti, G., & Gumley, A. (2008). An attachment perspective on schizophrenia: The role of disorganized attachment, dissociation and mentalization. Psychosis, Trauma and Dissociation: Emerging Perspectives on Severe Psychopathology, 14, 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470699652.ch9

- Maniglio, R. (2013). Child sexual abuse in the etiology of anxiety disorders: A systematic review of reviews. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(2), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838012470032

- Matheson, S. L., Shepherd, A. M., Pinchbeck, R. M., Laurens, K. R., & Carr, V. J. (2013). Childhood adversity in schizophrenia: A systematic meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 43(2), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712000785

- McCarty, R., & Gold, P. E. (1996). Catecholamines, stress, and disease: A psychobiological perspective. Psychosomatic Medicine, 58(6), 590–597. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-199611000-00007

- McTavish, J. R., Sverdlichenko, I., MacMillan, H. L., & Wekerle, C. (2019). Child sexual abuse, disclosure and PTSD: A systematic and critical review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 92, 196–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.006

- Merza, K., Papp, G., Molnár, J., & Szabó, I. K. (2017). Characteristics and development of nonsuicidal super self-injury among borderline inpatients. Psychiatria Danubina, 29(4), 480–489. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2017.480

- Misiak, B. (2017). Toward a unified theory of childhood trauma and psychosis: A comprehensive review of epidemiological, clinical, neuropsychological and biological findings. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 75, 393–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.015

- Molnar, B. E., Buka, S. L., & Kessler, R. C. (2001). Child sexual abuse and subsequent psychopathology: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. American Journal of Public Health, 91(5), 753–760. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.5.753

- Myin-Germeys, I., Krabbendam, L., Delespaul, P. A., & van Os, J. (2004). Sex differences in emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(6), 805–809. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.v65n0611

- O’Neill, T., Maguire, A., & Shevlin, M. (2021). Sexual trauma in childhood and adulthood as predictors of psychotic-like experiences: The mediating role of dissociation. Child Abuse Review, 30(5), 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2705

- Pruessner, M. (2008). Sex differences in the cortisol response to awakening in recent onset psychosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(8), 1151–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.04.006

- Pruessner, M. (2019). Gender differences in childhood trauma in first episode psychosis: Association with symptom severity over two years. Schizophrenia Research, 205, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.043

- Pruessner, M., Cullen, A. E., Aas, M., & Walker, E. F. (2017). The neural diathesis-stress model of schizophrenia revisited: An update on recent findings considering illness stage and neurobiological and methodological complexities. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 73, 191–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.12.013

- Pruessner, M., Vracotas, N., Joober, R., Pruessner, J. C., & Malla, A. K. (2013). Blunted cortisol awakening response in men with first episode psychosis: Relationship to parental bonding. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.06.002

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Read, J., Perry, B. D., Moskowitz, A., & Connolly, J. (2001). The contribution of early traumatic events to schizophrenia in some patients: A traumagenic neurodevelopmental model. Psychiatry, 64(4), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.64.4.319.18602

- Shrivastava, A. K., Karia, S. B., Sonavane, S. S., & De Sousa, A. A. (2017). Child sexual abuse and the development of psychiatric disorders: A neurobiological trajectory of pathogenesis. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 26(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.4103/ipj.ipj_38_15

- Spiller, T. R. (2020). On the validity of the centrality hypothesis in cross-sectional between-subject networks of psychopathology. BMC Medicine, 18(1), 297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01740-5

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Steinberg, M. (1994). Interviewer’s guide to the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV dissociative disorders (SCID-D). American Psychiatric Pub.

- Sullivan, G. M., & Feinn, R. (2012). Using effect size-or why the P value is not enough. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 4(3), 279–282. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-12-00156.1

- Sweeney, S., Air, T., Zannettino, L., & Galletly, C. (2015). Gender differences in the physical and psychological manifestation of childhood trauma and/or adversity in people with psychosis. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1768. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01768

- Teicher, M. H., Anderson, C. M., & Polcari, A. (2012). Childhood maltreatment is associated with reduced volume in the hippocampal subfields CA3, dentate gyrus, and subiculum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(9), E563–E572. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115396109

- Trotta, A., Murray, R. M., & Fisher, H. L. (2015). The impact of childhood adversity on the persistence of psychotic symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45(12), 2481–2498. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715000574

- Ullman, S. E., & Filipas, H. H. (2005). Gender differences in social reactions to abuse disclosures, post-abuse coping, and PTSD of child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29(7), 767–782. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.01.005

- Van Borkulo, C. D. (2017). Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Manuscript submitted for publication 10.

- van Borkulo, C., Epskamp, S., Jones, P., Haslbeck, J., & Millner, A. (2016). Package ‘NetworkComparisonTest’.

- Varese, F. (2012). Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: A meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(4), 661–671. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbs050

- Varese, F., Barkus, E., & Bentall, R. P. (2012). Dissociation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and hallucination-proneness. Psychological Medicine, 42(5), 1025–1036. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001826

- Vila-Badia, R. (2021). Types, prevalence and gender differences of childhood trauma in first-episode psychosis. What is the evidence that childhood trauma is related to symptoms and functional outcomes in first episode psychosis? A systematic review. Schizophrenia Research, 228, 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.11.047

- Vogeltanz, N. D. (1999). Prevalence and risk factors for childhood sexual abuse in women: National survey findings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23(6), 579–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00026-5

- von Stockert, S. H. H., Fried, E. I., Armour, C., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2018). Evaluating the stability of DSM-5 PTSD symptom network structure in a national sample of U.S. military veterans. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 63–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.043

- Walters, J. T., Bisson, J. I., & Shepherd, J. P. (2007). Predicting post-traumatic stress disorder: Validation of the Trauma Screening Questionnaire in victims of assault. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008658

- Wang, C., Tang, J., & Liu, T. (2020). The sexual abuse and neglect of “left-behind” children in rural China. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29(5), 586–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2020.1733159

- Wang, X. Q., & Chen, P. J. (2014). Population ageing challenges health care in China. The Lancet, 383(9920), 870. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60443-8

- Weierich, M. R., & Nock, M. K. (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms mediate the relation between childhood sexual abuse and nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.39

- World Health Organization. (1999). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused: WHO clinical guidelines.

- World Health Organization. (2019). International statistical classification of diseases, eleventh revision (ICD-11).

- Wright, D. B., & Loftus, E. F. (1999). Measuring dissociation: Comparison of alternative forms of the dissociative experiences scale. The American Journal of Psychology, 112(4), 497–519. https://doi.org/10.2307/1423648

- Zhang, Y. L. (2013). Validity and reliability of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Patient Health Questionnaire-2 to screen for depression among college students in China. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 5(4), 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12103

- Zhao, C., Wang, F., Zhou, X., Jiang, M., & Hesketh, T. (2018). Impact of parental migration on psychosocial well-being of children left behind: A qualitative study in rural China. International Journal for Equity in Health, 17(1), 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-018-0795-z