ABSTRACT

Background: Healthcare staff represent a high-risk group for mental health difficulties as a result of their role during the COVID-19 pandemic. A number of wellbeing initiatives have been implemented to support this population, but remain largely untested in terms of their impact on both the recipients and providers of supports.

Objective: To examine the experience of staff support providers in delivering psychological initiatives to healthcare staff, as well as obtain feedback on their perceptions of the effectiveness of different forms of support.

Method: A mixed methods design employing a quantitative survey and qualitative focus group methodologies. An opportunity sample of 84 psychological therapists providing psychological supports to Northern Ireland healthcare staff participated in an online survey. Fourteen providers took part in two focus groups.

Results: The majority of providers rated a number of supports as useful (e.g. staff wellbeing helplines, Hospital In-reach) and found the role motivating and satisfying. Thematic analysis yielded five themes related to provision of support: (1) Learning as we go, applying and altering the response; (2) The ‘call to arms’, identity and trauma in the collective response; (3) Finding the value; (4) The experience of the new role; and (5) Moving forward.

Conclusions: While delivering supports was generally a positive experience for providers, adaptation to the demands of this role was dependent upon important factors (e.g. clinical experience) that need to be considered in the planning phase. Robust guidance should be developed that incorporates such findings to ensure effective evidence-based psychological supports are available for healthcare staff during and after the pandemic.

HIGHLIGHTS

Providers of wellbeing supports to healthcare staff during COVID-19 viewed them as useful and the role satisfying.

Key factors (e.g. clinical experience) should be considered to make the role manageable.

Guidance should be developed to ensure appropriate supports are delivered.

Antecedentes: El personal de salud representa un grupo de alto riesgo para las dificultades de salud mental como resultado de su papel durante la pandemia de COVID-19. Se han implementado varias iniciativas de bienestar para apoyar a esta población, pero permanecen ampliamente sin ser probadas en términos de su impacto tanto en los receptores como en los proveedores de apoyo.

Objetivo: Examinar la experiencia de los proveedores de apoyo al personal en la entrega de iniciativas psicológicas al personal de atención médica, así como obtener retroalimentación sobre sus percepciones de la efectividad de diferentes formas de apoyo.

Método: Un diseño de métodos mixtos que emplea una encuesta cuantitativa y metodologías cualitativas de grupos focales. Una muestra de oportunidad de 84 terapeutas psicológicos brindando apoyo psicológico al personal de atención médica de Irlanda del Norte participó en una encuesta en línea. Catorce proveedores participaron en dos grupos focales.

Resultados: La mayoría de los proveedores calificaron una serie de apoyos como útiles (p. ej., líneas de ayuda para el bienestar del personal, al alcance del Hospital) y encontraron que el rol era motivador y satisfactorio. El análisis temático arrojó cinco temas relacionados con la provisión de apoyo: (1) Aprendiendo sobre la marcha, aplicando y alterando la respuesta; (2) El ‘llamado a las armas’, identidad y trauma en la respuesta colectiva; (3) Encontrar el valor; (4) La experiencia del nuevo rol; y (5) Avanzando.

Conclusiones: Si bien la entrega de apoyos generalmente es una experiencia positiva para los proveedores, la adaptación a las demandas de este rol dependió de factores importantes (p. ej., experiencia clínica) que deben ser considerados en la fase de planificación. Debiera desarrollarse una guía sólida que incorpore dichos hallazgos para garantizar que haya apoyo psicológico efectivo basado en evidencia disponible para el personal de atención médica durante y después de la pandemia.

背景:医护人员因其在 COVID-19 疫情中的角色,是心理健康困难的高危人群。已经实施了一些身心健康扶助计划来支持这一人群,但对支持的接受者和提供者的作用大体上仍未得到检验。

目的:考查员工支持提供者向医护人员提供心理扶助的经验,并获得他们对不同形式支持有效性的看法反馈。

方法:采用定量调查和定性焦点小组方法的混合方法设计。一个由为北爱尔兰医护人员提供心理支持的 84 名心理治疗师组成的机会样本参与了一项在线调查。十四个提供者参加了两个焦点小组。

结果:大多数提供者将一些支持评为有用(例如,员工身心健康热线、手边医院),并发现该角色给与他们动力和满足感。主题分析产生了与提供支持相关的五个主题:1)边走边学,应用和改变反应; 2) 集体反应中的‘战斗号召’、身份和创伤; 3)寻找价值; 4)新角色的经历; 5) 前进。

结论:虽然提供支持对提供者来说通常是一种积极的体验,适应这一角色的需求取决于规划阶段需考虑的重要因素(例如,临床经验)。应制定纳入这些发现的稳健指南,以确保在疫情期间和之后为医护人员提供有效的循证心理支持。

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the psychological wellbeing of healthcare workers. Recent studies estimate that staff have experienced clinical levels of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, insomnia, and other mental health difficulties (Jordan et al., Citation2021; Kang et al., Citation2020; Olff et al., Citation2021). Potential antecedents for these issues include a number of stressors also faced by the wider public during the pandemic (e.g. social isolation, deprivation of liberties, reduced access to everyday wellbeing activities) as well as specific occupational challenges associated with working in the health service (McGlinchey et al., Citation2021). Increased exposure to patients with COVID-19, excessive clinical and managerial demands during pandemic surges, as well as more nuanced psychological sequelae associated with their health provider roles, most notably moral injury, have been cited as risk factors for psychopathology in this population (Jordan et al., Citation2021; Lamb et al., Citation2021).

While the research literature has drawn attention to the potentially overwhelming negative mental health consequences of COVID-19 for healthcare staff and wider society, it should be acknowledged that some observed effects have been more complex. An international study of mental health helpline usage reported an increase in helpline calls pertaining to loneliness, anxiety, and isolation during the pandemic, but a concomitant decrease in the topics of relationship issues, violence, and suicidal ideation. The findings also suggested that the prevalence of these more severe forms of mental health difficulties were mitigated by adequate provision of supports (Brulhart et al., 2021). Such a dynamic conceptualisation is reinforced by traumatogenic models that emphasise the buffering role of social support and cognitive ‘meaning-making’ in moderating the development of post-traumatic stress symptoms, as well as fostering alternative positive sequelae such as post-traumatic growth (Cohen & Wills, Citation1985; O’Donnell & Greene, Citation2021; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004). In this vein, if relevant protective factors and social supports are accessible to individuals before, during, and after profound negative life experiences such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this can offset the impact on their mental health (Li et al., Citation2021; Olff et al., Citation2021).

In response to this theoretical rationale and the vulnerability to psychological distress facing healthcare workers, a number of staff wellbeing guidance frameworks were launched to promote positive mental health among the workforce. The British Psychological Society COVID-19 Staff Wellbeing Group (2020) published a document outlining a series of stepped care strategies for staff support (e.g. psychological first aid). Moreover, Cole-King & Dykes (Citation2020) provided a regularly updated online matrix containing advice on practical self-care strategies that could be implemented to support individual staff and teams (e.g. ‘Buddy’ systems, Staff Huddles). In Northern Ireland, content from both these texts and recommendations from the wider literature base were used to develop a regional Staff Wellbeing Framework (Department of Health, Citation2020) with supports that fell under five broad categories:

Staff Wellbeing Helpline: A triage and psychological first aid phone line available in each Northern Ireland HSC Trust.

Drop-In Centres: A Psychological Therapist available on-site to signpost staff towards supports, self-help materials, as well as provide psychological first aid.

Hospital In-reach Support: A service where Psychological Therapists engage with hospital teams to develop bespoke support plans for staff employing relevant psychological supports (e.g. consultation; reflective practice with teams; mindfulness sessions; etc.)

Community Out-reach Support: A service where Psychological Therapists engage with community services (e.g. care homes) to develop bespoke support plans for staff employing relevant psychological supports similar to Hospital In-reach Support

General Wellbeing Initiatives: General self-help supports are made available on public health websites and HSC Trust Intranets (e.g. relaxation sessions, wellbeing apps, wellbeing webinars, resilience sessions).

Wellbeing supports during the COVID-19 pandemic have been positively-received by healthcare staff and provided some useful findings relating to their implementation. At the height of the pandemic, 32% of healthcare staff reported using staff wellbeing supports and 36% of those who did not access these interventions nevertheless felt supported knowing these services were available (Shannon et al., Citation2020). However, evidence for the clinical impact of specific forms of support remains lacking. A review by Buselli et al. (Citation2021) examined the extant research base on healthcare staff wellbeing interventions in healthcare settings. The authors concluded that few international studies published the content of their healthcare staff support protocols, and, as such, it was not possible to discern the useful elements within these support packages. Even more concerning was the lack of robust outcomes assessment, as it hinders the development of future intervention guidelines and limits the measurement of individual support effectiveness (Buselli et al., Citation2021; Siddiqui et al., Citation2021).

A further omission in the literature base is the limited understanding of how the unique stresses and demands of support roles impact on the wellbeing of psychological therapist providers. Recent evidence has shown that mental health workers represent a further at-risk population within healthcare services, exhibiting increased irritability and loneliness relative to other clinical staff (Brillon et al., Citation2021). In addition to providing potential support roles, mental health staff have also had to adjust to a number of unique modifications in practice, including a change in intervention delivery models (e.g. remote therapy), while at the same time demonstrating a well-documented tendency to neglect their own needs and self-care (Rokach & Boulazreg, Citation2020).

The specific risk factors, both personal and organisational, that contribute to how effectively therapists have adapted to the pressures of new roles during the pandemic presents as an important new avenue of investigation. Clinician characteristics such as level of experience and post-qualification training have been shown to contribute to capacity in managing work demands (Kjellenberg et al., Citation2014; Kumar et al., Citation2019). Understanding the salient variables relevant to the experience of providing staff supports may be highly beneficial for the development of future psychological wellbeing pandemic response guidelines.

Taking a qualitative approach, Billings et al. (Citation2021) completed one of the few studies in this area. The authors conducted a reflexive thematic analysis of interviews from 28 mental health professionals delivering wellbeing initiatives, identifying six themes. A ‘stepping up’ theme outlined how mental health clinicians were highly motivated to contribute to the COVID-19 response and support their front line colleagues. However, an ‘uncertainty, inconsistency, and lack of knowledge’ theme stressed that clinicians felt ill-prepared at times in terms of the formal training required to provide the supports, and experienced concomitant anxiety as a result. The qualitative analysis did not focus on the providers perceptions of support acceptability and effectiveness; although the authors commented that more research needs to target these outcomes. Moreover, further exploration of specific clinician and organisational factors was not a focus of the study.

The present study followed on from Billings et al. (Citation2021) by utilising a mixed methods approach to examine the experience of staff support providers in delivering psychological supports to healthcare staff, as well as the role of clinician factors relevant in their adjustment to this role. In order to inform future development of robust intervention frameworks, support providers also gave feedback on the effectiveness of different forms of support, most notably perceived usefulness and suggestions for improvement of delivery. It was hypothesised that practitioner clinical and demographic factors would be significantly related to their experience of delivering supports (e.g. stress levels, ability to manage demands of the role). Moreover, it was predicted that types of wellbeing support would differ significantly on provider ratings of perceived usefulness.

1. Method

1.1. Design and participants

The cross-sectional study employed a convergent parallel design, wherein qualitative and quantitative data were collected in parallel (Fetters et al., Citation2013). Quantitative data was analysed first, with the findings used to inform the focus of the qualitative analysis. Several integration methods were used including connecting and merging (Fetters et al, Citation2013). Specifically, the qualitative sample was drawn from a subpopulation of participants who were invited to participate in the survey, and the questions of the surveys and interviews were carefully designed to facilitate merging post analysis. All 208 psychological therapists in Northern Ireland providing psychological supports to health and social care staff during the COVID-19 pandemic as part of the HSC Regional Staff Wellbeing Framework were invited to take part in the Staff Support Provider Survey. A total of 84 psychological therapists participated in the survey (response rate = 40%).

Psychological support providers within one specific HSC Trust, the Northern Health and Social Care Trust (NHSCT), were also invited to take part in focus groups. Focus groups were the chosen mode of qualitative data collection since providers were already engaging in reflective practice groups in relation to their support role. It was decided that this forum would provide a familiar and comfortable setting for staff to have free-flowing discussions about their experiences. Of the 60 psychology support providers approached, 21 staff volunteered (35%). Booking systems were established to identify suitable time slots for the two focus groups: (1) for those who both provided and managed the psychological supports for staff; (2) for those who provided psychological supports to staff only. In total, 14 psychological support providers who varied in terms of years of experience, specialisation, and gender were available to participate in the focus groups (7 per group). No renumeration was provided to the focus group participants as staff were allowed to take part during normal working hours.

1.2. Measures

1.2.1. Staff support provider survey

This survey included a range of demographic questions (e.g. gender, clinical specialism, clinician seniority, clinician years’ experience). The remainder of the questionnaire asked about experiences of providing wellbeing supports. Respondents were asked which of the 5 provision types they had delivered (i.e. Staff Wellbeing Helpline; Drop-In Centres; Hospital In-reach Support; Community Out-reach Support; General Wellbeing Initiatives) and to rate those supports on the following dimensions using a five-point Likert scale: usefulness (1 = not useful; 5 = very useful); quality of the support and guidance provided (1 = very poor; 5 = very good).

A further section asked respondents general questions about their experiences of providing staff psychological supports, including: (a) anxiety levels prior to undertaking their new role (1 = not anxious; 5 = very anxious); (b) confidence levels in providing supports (1 = not confident; 5 = very confident); (c) stress levels during provision of supports (1 = not stressful; 5 = very stressful); (d) how challenging it was to manage the demands of their job role (1 = not challenging; 5 = very challenging); (e) how challenging it was to maintain a work-life balance (1 = not challenging; 5 = very challenging); and (f) level of job satisfaction (1 = not satisfied; 5 = very satisfied).

A final section provided respondents with a menu of actions that could potentially improve delivery of psychological supports. Participants were asked to click on options that would have improved their experience of providing these initiatives.

1.2.2. Semi-structured interview

This interview schedule (Appendix 1, supplemental data) contained focus group questions pertaining to the following: (a) types of support participants had provided; (b) how often and for how long they had provided support; (c) thoughts and feelings they had about providing support before starting the role; (d) their experience of providing supports; (e) challenges faced in delivering staff psychological support; (f) aspects of provision that worked well and those that could be improved. A joint display depicting how the theoretical constructs measured by the qualitative and quantitative data sources is shown in .

Table 1. Joint display of mixed methods data collection.

1.3. Procedure

The Staff Support Provider survey was completed online via the Survey Mechanics platform. All psychological therapists in Northern Ireland involved in the provision of HSC Regional Staff Wellbeing Framework supports were issued an email invite to take part in the Staff Support Provider survey; the survey ran from 11–24 January 2021. Focus groups were conducted via zoom in December 2020 using a semi-structured interview format.

The research was approved by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Service (REC reference 20/WS/0122), and was conducted in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (revised in 2013). Participants provided informed consent after receiving a full explanation of the study and anonymisation procedures.

2. Data analysis

There were no missing values in the survey dataset as all questions were designated ‘required’ in the survey platform. Bootstrapped bias-corrected multiple regressions with simultaneous entry were used to examine the relationship between five independent variables (gender; clinical specialism, clinician years’ experience; clinician seniority and amount of supports provided) and the dependent variables of prior anxiety, stress levels, confidence levels, job satisfaction, ability to manage demands of job role, and work-life balance. Clinical specialism was recoded into adult (reference category), non-adult, and other for the purposes of regression analyses. Number of supports provided was the sum of support types clinicians had been involved in delivering (range 1-5). Both clinician years’ experience and clinician seniority were treated as continuous variables in the regressions. Participants whose seniority was classified as ‘other’ were excluded from these analyses, meaning the regression models were run on a sample of 74. This sample size yielded sufficient power to detect a medium effect size (f2 = .21) using 6 predictors with a power level of 80%, alpha = .05. Two chi-square analyses were conducted comparing types of wellbeing support on their perceived ‘usefulness’ and ‘support and guidance provided’ for their delivery. Qualitative data were analysed via thematic analysis in accordance with the protocol outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). A number of integration strategies were used during the mixed methods analysis including explaining and corroborating (Fetters, Citation2013). For example, in relation to the perceived usefulness of different support types, the qualitative and quantitative findings were compared to see if they supported the same conclusions, with qualitative findings being used to provide an explanation for the usefulness ratings.

3. Results

3.1. Survey Sample characteristics

Demographic characteristics of the Staff Support Provider survey sample and their means on specific provider experiences are presented in and . Most respondents were involved in providing helpline support (75%), with fewer (21-33%) being involved in the drop-in centres, in-reach, out-reach, and general wellbeing initiatives.

Table 2. Demographic variables from the Psychology Support Provider Survey sample.

Table 3. Provider experience ratings from the Psychology Support Provider sample.

3.2. Experiences of providing each support type

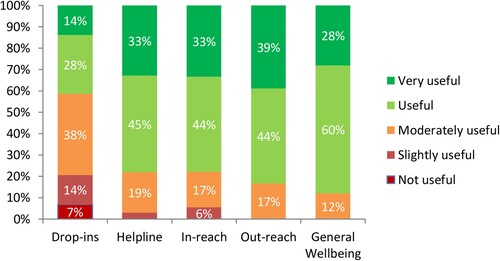

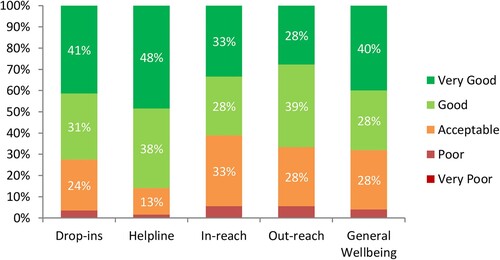

The majority of support providers rated helplines (79%), Hospital In-reach (78%), Community Out-reach (83%) and general wellbeing initiatives (88%) as being useful or very useful (). By contrast, fewer than half of those involved in the drop-ins considered them to be useful or very useful (43%). Good to very good ratings were assigned by most respondents to the support and guidance provided to them: drop-ins (71%); helpline (86%); in-reach (61%); out-reach (67%); general wellbeing initiatives (68%; ).

Due to assumption violations, the ‘usefulness’ and ‘support and guidance provided’ variables were recoded dichotomously (e.g. very useful/useful vs not/moderately/slightly useful) to support chi-square analyses. Type of wellbeing support differed significantly on ratings of ‘usefulness’, χ2(4) = 19.77, p = .001, Cramer’s v = .36, but not on ‘support and guidance provided’ χ2(4) = 7.42, p = .116, Cramer’s v = .22. Post-hoc z-tests were conducted to compare column proportions, revealing that the proportion viewing the drop-ins as being useful or very useful was significantly lower compared to the other four provision types.

3.3. Factors related to experience providing support

provides the mean ratings given by clinicians on their experiences of providing staff psychological supports. In terms of Likert rating endorsements, only a small proportion of staff reported feeling anxious or very anxious before providing the support (11%) or being stressed or very stressed while working a staff support provider (5%). The majority of respondents reported feeling confident or very confident (70%) and having good or very good job satisfaction (71%) while providing the supports. Around one quarter, found it challenging or very challenging to manage the demands of their job role (27%) or to maintain a work-life balance (25%)

Bootstrapped bias-corrected multiple regressions (n = 74) were used to examine the relationship between the independent variables of gender, specialism, clinician years’ experience, clinician seniority, and number of supports provided, and each of the six support staff provider experience dependent variables (). No significant relationships were found between the independent variables and prior anxiety or ability to manage job role demands. Those from a non-adult specialism reported significantly higher levels of stress while providing psychology supports compared to those from an adult specialism, although overall the model only explained a very small amount of variance (model adjusted R2 = 2%). Higher levels of confidence while providing psychology supports was associated with a greater number of years having worked as a clinician; the overall model explained a considerable amount of variation in confidence levels (model adjusted R2 = 34%). Those who had served as a clinician for a greater number of years and had lower clinician seniority reported better levels of job satisfaction (model adjusted R2 = 14%). Finally, being from non-adult specialism and being involved in a greater number of provision types was significantly associated with difficulty maintaining a work-life balance (model adjusted R2 = 27%).

Table 4. Factors associated with experience providing psychology support to health and social care staff.

3.4. Recommendations for improvement

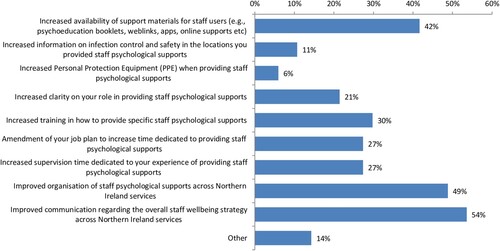

contains the percentage of support providers who endorsed specific recommendations that would have improved their experience of delivering staff wellbeing interventions. The recommendations most commonly selected were (1) Improved communication regarding the overall staff wellbeing strategy (54%); (2) Improved organisation of staff psychological supports (49%); and (3) Increased availability of support materials for staff users (42%).

3.5. Qualitative findings

Focus group participants responses to questions on their experiences of providing psychological staff supports clustered around five themes, namely: (1) Learning as we go, applying and altering the response; (2) The ‘call to arms’, identity and trauma in the collective response; (3) Finding the value; (4) The experience of the new role; and (5) Moving forward. Evidence supporting all 5 themes emerged in both focus groups.

Theme 1: Learning as we go, applying and altering the response. Providers reflected on the evolution of staff support roles throughout the pandemic. Participants initially described a response of reacting without thinking, in which they were propelled into ‘action mode’ (FG2, S3, p. 6), and felt emotionally compromised by being unable ‘to think around it … I was able to do … ’ (FG2, S6, p. 15). This was attributed to personal factors (e.g. internal desires to help and be useful) and organisational factors (e.g. to be seen to respond to the needs of staff, urgent need to establish psychological supports). This initial reaction was followed by a process of learning and ‘discovering as we were doing it’ (FG1, S1, p. 12), where it took time to understand the most effective supports. The low uptake of some supports originally provided, particularly drop-in supports, was believed to be due to early drives to react to the novelty of the pandemic in the absence of reflection:

Looking back at it now there has been a beautiful evolution here of what is helpful and what isn’t … . We threw everything at it at the start … then we had data to look at … the staff voted with their feet … I think there’s been a lot of learning. (FG2, S6, p. 7)

Theme 2: The ‘call to arms’, identity and trauma in the collective response. Participants described the ‘call to arms’ (FG1, S5, p. 5), with volunteers mobilised to fulfil new roles at a time of uncertainty. Individuals shared their willingness to offer support during the crisis but considered this in the context of personal fears, compromised safety, and heightened responsibilities in the service of others. Participants reflected on the personal battles associated with trying ‘to help people process the pandemic while you hadn’t quite processed it yourself’ (FG1, S1, p. 5):

… there was a real sense of urgency … when I rode that wave I felt less vulnerable … I wonder if maybe that was reflective of what staff were doing as well … ? Were they riding the wave of ‘this is easier than feeling brittle and vulnerable and exposed’ … . (FG2, S2, p. 7)

Theme 3: Finding the value. Participants compared the quality, quantity, and value of staff supports. While drop-in sessions were associated with limited staff engagement, participants stated that there was some ‘value in those sessions’ (FG1, S4, p. 15) on the few occasions they were used. Nevertheless, the low uptake was deemed to outweigh the need for this form of intervention. Helpline services were viewed as more helpful and adopted to a greater degree by staff. Providers who experienced repeat helpline contact with staff members described feeling reassured that the support provided was ‘obviously something that was helpful’ (FG1, S5, p. 11). Hospital In-reach and Community Out-reach interventions were viewed as the most valuable supports, and were a key consideration for the tailoring of psychological support as the pandemic progressed:

… the input for managers is really important … being able to provide something to them to help them do their job in containing and holding their team … I think that would be really useful going forward. (FG2, S3, p. 17)

Theme 4: The experience of the new role. Providers described the challenge of ‘stepping back from what we’re trained to do’ (FG1, S2, p. 11) when delivering supports. Clinicians who normally practiced in child services, intellectual disability services, and high intensity specialist mental health teams had to adapt to delivering low intensity supports to an adult population. Providers voiced concerns regarding consistency of practice, with a belief that training could have been given on Psychological First Aid to establish ‘a shared vision for what we actually should have been doing’ (FG1, S1, p. 17). Participants also struggled with feelings of frustration and resentment when supports were not used. This added to the pressure of maintaining a dual role (e.g. both Support Provider to staff and Clinical Psychologist in a child service) as ‘services had to keep going … ’ (FG2, S5, p. 18) and participants felt a need to complete their normal job duties when supports were not accessed. At the time of interview, a number were no longer providing psychological support due to the changing need for specific interventions, and had returned to standard duties:

I was quite relieved when they wound down … it was hard to sustain. Initially our demand-capacity balance changed quite a lot … then that sort of wore off, the referral rate crept up. How are we going to juggle this with everything else that I’m meant to be doing?. (FG2, S2, p. 5)

Theme 5: Moving forward. Participants discussed experiences following the alteration or discontinuation of staff supports, reporting a range of emotions including relief and ‘guilt at feeling the relief whenever we didn’t have to provide it anymore’ (FG2, S5, p. 17). Ongoing uncertainty was reflected in their comments with some acknowledging that the pandemic had become more severe, and moving forward required a commitment from volunteers to remain available should they be needed in the future:

… things are actually worse … this situation is totally different. There’s a lot more pressure on the wards. The hospital staff are under a lot more pressure than they were back then … . (FG2, S4, p. 17)

I don’t think we did well enough to look after ourselves. I don’t think as a psychology service we thought our own staff are going to find this really difficult, and we just put another level of stress upon them by asking them to [provide support]. (FG2, S1, p. 19)

4. Discussion

This study used a unique mixed method approach to examine the views and experience of staff providers in delivering psychological supports to healthcare staff. As hypothesised, there were significant differences in the perceived usefulness of the wellbeing supports. Participants reported that a number of social support interventions developed during the first year of the pandemic were useful, most notably staff wellbeing helplines, Hospital In-reach, Community Out-reach and general wellbeing initiatives. Difficulties associated with the new role of support provider were also identified. While overall staff anxiety/stress was relatively low and satisfaction levels high, a small proportion of providers found the role challenging. The hypothesised contribution of clinician factors to this adjustment process was confirmed, with more experienced clinicians likely to have higher levels of confidence and satisfaction in the new role. Prominent factors associated with a negative experience included lower levels of clinical experience; higher clinician seniority; higher number of supports provided; and practicing in a non-adult specialism.

There was clear similarity between the themes identified in the present study and those found in the only other qualitative study to have evaluated staff support providers’ experiences (i.e. Billings et al. Citation2021). Support providers were proud to be part of a ‘call to arms’ response aimed at helping fellow healthcare workers maintain their wellbeing. However, even though staff were highly motivated and quick to move into ‘action mode’ as providers, they reported concomitant feelings of uncertainty and a lack of preparatory training. ‘The experience of the new role’ theme stressed the need for additional training to ensure consistency of support implementation and highlighted the considerable challenges faced by providers in maintaining a manageable job role balance. Quantitative fundings further reinforce this point with 42% of providers reporting that the increased availability of support materials would have improved their ability to deliver interventions.

The fundamental issues of staff unpreparedness, workload demands, and the need for appropriate advance training in support functions have been raised in recent studies and previous pandemic research (Billings et al., Citation2021; Forbes et al., Citation2011; Maunder et al., Citation2008). A key interpretation is that job-planning, skills development, supervision, and resource allocation should be prioritised when assigning psychological therapists to support provider roles. In times of crisis and reactive planning, it can be taken for granted that staff will easily generalise clinical skills and knowledge (e.g. assumptions of quick adaptability of ‘non-adult’ specialisms to an adult population), but this may, in fact, be challenging in heightened circumstances and require enhanced support to ensure provider wellbeing and intervention effectiveness.

Support staff described substantive learning throughout the process of providing wellbeing interventions. Converging evidence from all strands suggests that over time staff developed an awareness of the utility, or lack thereof, of specific social supports. Drop-In Centres were viewed to have low levels of staff engagement and significantly less utility. Early drives to provide this type of intuitively helpful intervention were seen to represent the oft-cited, well-intentioned need to be responsive during a pandemic in the absence of reflection or clear evidence of effectiveness (Buselli et al., Citation2021; Jonker, Graupner, & Rossouw, Citation2020). While it was acknowledged that the small number of staff attending drop-ins may have benefited from this approach, the present study re-affirms the necessity of evaluating ongoing interventions, since results from such studies may conflict with pre-existing anecdotal assumptions of their value.

The ‘finding the value’ theme and high usefulness ratings for specific interventions suggest that a mixed model of evidence-based low intensity general supports available to all staff (e.g. helplines, wellbeing website, self-help materials) and high intensity tailored supports targeting specific teams in need (e.g. Hospital In-Reach, Community Out-Reach) might be a helpful, basic organisation of supports. In terms of the latter, the ‘finding the value’ theme revealed that, over the course of the pandemic, support providers came to the conclusion that these systemic approaches were more useful than initially considered. Hospital In-Reach was highly rated due to the emphasis on equipping line managers with the skills to support their team in a variety of meaningful bespoke ways. It also increased accessibility and uptake in frontline teams as support was specifically configured via an engagement process to be delivered to staff at a convenient time (e.g. during their shift) and place (e.g. on a designated ward). In contrast, general supports such as helplines had their value in being openly available to all, with the capacity to provide low intensity supports to a wide range of staff. Broader organisational factors, specifically improved communication and co-ordination of supports, were highlighted as important means to ensure this form of multifaceted delivery, influences that have also been noted in other empirical studies (see Maunder et al., Citation2008; Jordan et al., Citation2021).

4.1. Implications

Providers highlighted the utility of a number of social support interventions in mitigating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic stressors on staff wellbeing, while also stressing the need for appropriate preparation, co-ordination, communication, and delivery. The findings show there is a clear role for psychological services to be more involved in disaster planning, particularly the development of evidence-based psychological wellbeing pandemic response guidelines for the wider public and specific at-risk populations (i.e. healthcare staff). While helpful, current pandemic protocols were developed ad hoc and limited in both detail and training advice. More robust guidelines should include best practice recommendations gathered from the wider evidence base, including provider studies. For example, the current findings suggest that staff wellbeing response preparation should take into account professional background of the provider (e.g. clinician experience, seniority, adult vs non-adult specialism), wider job responsibilities, and training needs to create an individualised provider job plan and resource package to ensure effective delivery of evidence-based wellbeing supports (e.g. Psychological First Aid; Shah et al., Citation2020).

4.2. Limitations

The present study had number of methodological limitations, partly due to practical issues of conducting the investigation during the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus groups were delivered via Zoom and low numbers were obtained; however, there was evidence to suggest saturation had been reached as all five themes emerged in both focus groups. The quantitative sample was also small, restricting both interpretation and capacity to perform more powerful multivariate analysis. Moreover, the investigation examined the perspective of a relatively niche population involved in the pandemic response (i.e. staff providers), whereas a more comprehensive analyses of the views of providers, recipients, managers, and commissioners of staff wellbeing initiatives would allow more substantive conclusions to be drawn as to support effectiveness. The online survey was also cross-sectional and used a force-choice format in some items, which, although useful in gaining a comprehensive data set, has received criticism regarding response bias (Dhar & Simonson, Citation2003). In spite of these shortcomings, the findings still provide useful insights into the wider understanding of staff wellbeing provision during the COVID-19 pandemic and a foundation for the development of large-scale studies using more rigorous indices of effectiveness.

5. Conclusion

The research highlights the importance of supporting healthcare workers and wellbeing providers in the most effective way possible during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Providers reported several staff wellbeing initiatives as useful and were highly motivated to support the needs of their colleagues. However, their adaptation to the demands of this role was dependent upon professional and training factors that need to be addressed in bespoke job plans. Disaster planning guidance should be developed that incorporates these types of findings and other psychological perspectives to ensure the rollout of evidence-based psychological wellbeing initiatives for the wider public and healthcare staff.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thanks all of the health and social care staff who took part, and to those staff at the participating Health and Social Care Trusts who disseminated information about the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (KD), upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Billings, J., Biggs, C., Chi Fung Ching, B., Gkofa, V., Singleton, D., Bloomfield, M., & Green T. (2021). Experiences of mental health professionals supporting front-line health and social care workers during COVID-19: Qualitative study. BJPsych Open, 7(2), https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.29

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brillon, P., Philippe, F. L., Paradis, A., Geoffroy, M., Orri, M., & Ouellet-Morin, I. (2021). Psychological distress of mental health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparison with the general population in high- and low-incidence regions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(4), 602–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23238

- The British Psychological Society COVID-19 Staff Wellbeing Group. (2020). The Psychological Needs Of Healthcare Staff As A Result Of The Coronavirus Pandemic. British Psychological Society.

- Buselli, R., Corsi, M., Veltri, A., Baldanzi, S., Chiumiento, M., Del Lupo, E., Marino, R., Necciari, G., Caldi, F., Foddis, R., Guglielmi, G., & Cristaudo, A. (2021). Mental health of Health Care Workers (HCWs): a review of organizational interventions put in place by local institutions to cope with new psychosocial challenges resulting from COVID-19. Psychiatry Research, 299, 113847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113847

- Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

- Cole-King, A., & Dykes, L. (2020). Wellbeing for HCWs during COVID19, https://www.lindadykes.org/covid19.

- Department of Health. (2020). Supporting the well-being needs of our health and social care staff during COVID-19: A framework for leaders and managers. Northern Ireland Department of Health.

- Dhar, R., & Simonson, I. (2003). The effect of forced choice on choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 40(2), 146–160. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.40.2.146.19229

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs – principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6pt2), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Forbes, D., Lewis, V., Varker, T., Phelps, A., O’Donnel, M., Wade, D. J., Ruzek, J. I., Watson, P., Bryant, R. A., & Creamer, M. (2011). Psychological first aid following trauma: implementation and evaluation framework for high-risk organizations. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 74(3), 224–239. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2011.74.3.224

- O’Donnell, M. L., & Greene, T. (2021). Understanding the mental health impacts of COVID-19 through a trauma lens. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12), https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1982502

- Jonker, B. E., Graupner, L. I., & Rossouw, L. (2020). An Intervention framework to facilitate psychological trauma management in high-risk occupations. Frontiers in Psychology, 11), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00530

- Jordan, J.-A., Shannon, C., Browne, D., Carroll, E., Maguire, J., Kerrigan, K., Hannan, S., McCarthy, T., Tully, M. A., Mulholland, C., & Dyer, K. F. W. (2021). COVID-19 Staff Wellbeing Survey: longitudinal survey of psychological well-being among health and social care staff in Northern Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open, 7, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.988

- Kang, L., Ma, S., Chen, M., Yang, J., Wang, Y., Li, R., Yao, L., Bai, H., Cai, Z., Xiang Yang, B., Hu, S., Zhang, K., Wang, G., Ma, C., & Liu, Z. (2020). Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behaviour, & Immunity, 87, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi

- Kjellenberg, E., Nilsson, F., Daukantaité, D., & Cardeña, E. (2014). Transformative narratives: The impact of working with war and torture survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031966

- Kumar, S. A., Brand, B. L., & Courtois, C. A. (2019). The need for trauma training: Clinicians’ reactions to training on complex trauma. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000515

- Brülhart, M., Klotzbücher, V., Lalive, R., & Reich, S. K. (2021). Mental health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic as revealed by helpline calls. Nature, 600(7887), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04099-6

- Lamb, D., Gnanapragasam, S., Greenberg, N., Bhundia, R., Carr, E., Hotopf, M., Razavi, R., Raine, R., Cross, S., Dewar, A., Docherty, M., Dorrington, S., Hatch, S., Wilson-Jones, C., Leightley, D., Madan, I., Marlow, S., McMullen, I., Rafferty, A.-M., … Wessely, S. (2021). Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4378 UK healthcare workers and ancillary staff: initial baseline data from a cohort study collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 78(11), 801–808. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-107276

- Li, F., Luo, S., Mu, W., Ye, L., Zheng, X., Xu, B., Ding, Y., Ling, P., Zhou, M., & Chen, X. (2021). Effects of sources of social support and resilience on the mental health of different age groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-03012-1

- Maunder, R. G., Leszcz, M., Savage, D., Adams, M., Peladeau Romano, D., Rose, M., & Schulman, R. (2008). Applying the lessons of SARS to pandemic influenza. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 99, 486–488. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403782

- McGlinchey, E., Hitch, C., Butter, S., McCaughey, L., Berry, E., & Armour, C. (2021). Understanding the lived experiences of healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1904700

- Olff, M., Primasari, I., Qing, Y., Coimbra, B. M., Hovnanyan, A., Grace, E., Williamson, R. E., Hoeboer, C. M., & the GPS-CCC Consortium (2021). Mental health responses to COVID-19 around the world. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12), https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1929754

- Rokach, A., & Boulazreg, S. (2020). The COVID-19 era: How therapists can diminish burnout symptoms through self-care. Current Psychology, 41(8), 5660–5677. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01149-6

- Shah, K., Bedi, S., Onyeaka, H., Singh, R., & Chaudhari, G. (2020). The role of psychological first aid to support public mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. Cureus, 12, https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8821

- Shannon, C., Jordan, J.-A., & Dyer, K. (2020). COVID-19 wellbeing survey time one findings. IMPACT Research Centre, Northern Health and Social Care Trust. http://www.impactresearchcentre.co.uk/site/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/COVID-19-Wellbeing-Survey-Brief-Report-21_12_2020-FINAL-2.pdf.

- Siddiqui, I., Aurelio, M., Gupta, A., Blythe, J., & Khanji, M. (2021). COVID-19: Causes of anxiety and wellbeing support needs of healthcare professionals in the UK: A cross-sectional survey. Clinical Medicine, 21(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmed.2020-0502

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Target ARTICLE: “posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence”. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01