ABSTRACT

Background: Narrative Therapy is an efficacious treatment approach widely practiced for various psychological conditions. However, few studies have examined its effectiveness on resilience, a robust determinant of one’s mental health, and there has been no randomized controlled trial in sub-Saharan Africa.

Objective: This study sought to evaluate the efficacy of narrative therapy for the resilience of orphaned and abandoned children in Rwanda.

Method: This study was a ‘parallel randomized controlled trial’ in which participants (n = 72) were recruited from SOS Children’s Village. Half of the participants (n = 36) were randomly allocated to the intervention group and the rest to the delayed narrative therapy group. For the intervention group, children attended ten sessions (55 min each) over 2.5 months. Data were collected using the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM) and analyzed using mixed ANOVA within SPSS version 28.

Result: The results from ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of time and group for resilience total scores. Of interest, there was a significant time by group interaction effect for resilience. Pairwise comparison analyses within-group showed a significant increase in resilience in the intervention group, and the effect size was relatively large in this group.

Conclusion: Our findings highlight the notable efficacy of narrative therapy for children’s resilience in the intervention group. Therefore, health professionals and organizations working with orphaned and abandoned children will apply narrative therapy to strengthen their resilience and improve mental health.

Trial registration: Pan African Clinical Trial Registry identifier: PACTR202107499406828..

HIGHLIGHTS

The effect size of narrative therapy for resilience was relatively large in the intervention group.

Narrative therapy is an efficacious approach for resilience elevation in orphaned and abandoned children.

Close attention should be paid to the implementation of narrative therapy for strengthening children’s resilience as an everyday tool in foster care.

Antecedentes: La Terapia Narrativa es un enfoque de tratamiento eficaz ampliamente practicado para varias condiciones psicológicas. Sin embargo, pocos estudios han examinado su efectividad en la resiliencia, un determinante sólido de la salud mental, y no ha habido ningún ensayo controlado aleatorizado en el África subsahariana.

Objetivo: Este estudio buscó evaluar la eficacia de la terapia narrativa para la resiliencia de niños huérfanos y abandonados en Ruanda.

Método: Este estudio fue un "ensayo controlado aleatorizado en paralelo" en el que los participantes (n = 72) fueron reclutados de Aldeas Infantiles SOS. La mitad de los participantes (n = 36) fueron asignados aleatoriamente al grupo de intervención y el resto al grupo de terapia narrativa diferida. Para el grupo de intervención, los niños asistieron a diez sesiones (55 minutos cada una) durante 2,5 meses. Los datos se recopilaron utilizando el instrumento de resiliencia infantil y juvenil (CYRM) y se analizaron mediante ANOVA mixto dentro de SPSS versión 28.

Resultado: Los resultados de ANOVA indicaron un efecto principal significativo del tiempo y el grupo para las puntuaciones totales de resiliencia. Además, hubo un tiempo significativo por efecto de interacción grupal para la resiliencia. Los análisis de comparación por pares dentro del grupo mostraron un aumento significativo en la resiliencia en el grupo de intervención, y el tamaño del efecto fue relativamente grande en este grupo.

Conclusión: Nuestros hallazgos destacan la notable eficacia de la terapia narrativa para la resiliencia de los niños en el grupo de intervención. Por ello, los profesionales de la salud y las organizaciones que trabajan con niños huérfanos y abandonados aplicarán la terapia narrativa para fortalecer su resiliencia y mejorar la salud mental.

背景:叙事疗法是一种广泛应用于各种心理状况的有效治疗方法。然而,很少有研究检验它对心理韧性的有效性,心理韧性是一个人心理健康的重要决定因素,而且在撒哈拉以南非洲也没有随机对照试验。

目的:本研究旨在评估叙事疗法对卢旺达孤儿和被遗弃儿童心理韧性的疗效。

方法:本研究是一项“平行随机对照试验”,参与者 (n = 72) 来自 SOS 儿童村。一半参与者 (n=36) 被随机分配到干预组,其余参与者分配到延时叙述治疗组。对于干预组,孩子们在 2.5个月内参加了 10个疗程(每次 55 分钟)。使用儿童和青少年心理韧性测量 (CYRM) 收集数据,使用28 版SPSS中的混合方差分析进行分析。

结果:ANOVA 的结果表明时间和组别对心理韧性总分有显著的主效应。有趣的是,群体互动对心理韧性影响显著。组内两两比较分析显示,干预组的心理韧性显著增加,且该组效应量相对较大。

结论:我们的研究结果强调了叙事疗法对干预组儿童心理韧性的显著疗效。因此,面向孤儿和被遗弃儿童工作的卫生专业人员和组织将应用叙事疗法来增强其心理韧性,改善其心理健康。

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

Orphanhood and child abandonment in war-affected and undeveloped countries are alarming global public health issues due to their mental health and physical implications. Of the 153 million orphans estimated worldwide, 52 million are from Africa (UNICEF, Citation2017). In Rwanda, nearly 590,000 children were raised without parents (SOS, Citation2017). Several orphanages have emerged worldwide to address the problems, with an estimated 6,000,000 children institutionalized (Goldman et al., Citation2020; Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2011). In Rwanda, residential child care institutions, known as orphanages, increased in the aftermath of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi (Hope and Homes for Children, Citation2016). However, a pool of literature shows that orphanhood and institutionalization may lead a child to develop psychological problems (Shulga et al., Citation2016; Nsabimana et al., Citation2019), but the child is severely affected when both conditions co-occur (Nsabimana et al., Citation2019). Consequently, the Government of Rwanda piloted the de-institutionalization process in 2013 and started Tubarerere Mu Muryango (TMM) (Let’s Raise Children in Families) to promote family-based care (TMM, Citation2019). In 2017, all orphanages were already closed except for SOS Children’s Villages due to support programmes and policies, including narrative therapy to strengthen children’s resilience (SOS, Citation2020).

The concept of resilience has undergone a significant shift during the past two decades, moving from ‘trait-oriented’ to ‘an outcome-or process-oriented perspective’ (Chmitorz et al., Citation2018). A trait-oriented approach assumes that a specific personality type, called a ‘hardy personality,’ that facilitates individual adaptability to stress or adversity, is essentially what determines resilience (Block & Block, Citation1980; Hu et al., Citation2015; Ong et al., Citation2006). When resilience is viewed as a trait, it is thought to be a permanent attribute, but there is currently only scant empirical support for that premise (Bonanno & Diminich, Citation2013; Kalisch et al., Citation2017). As an alternative, personality appears to be one of many risks or resilience factors for preserving or restoring mental health (Bonanno & Diminich, Citation2013; Luthar et al., Citation2000). Resilience is now more frequently thought of as an outcome (outcome-oriented approach), which means that it refers to the ability to maintain or regain mental (or physical) health in the face of significant stress or adversity (e.g. short-term/acute or long-term/chronic, social or physical stressors), (Kalisch et al., Citation2015; Kalisch et al., Citation2017). The current study focuses on the second definition, where resilience is fundamentally predicated on exposure to significant risk or adversity (Earvolino-Ramirez, Citation2007; Jackson et al., Citation2007; Luthar et al., Citation2000). Similarly, American Psychological Association (2020) defines resilience as ‘the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress, such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems, or workplace and financial stressors.’ Resilience increases well-being and life satisfaction (Aiena et al., Citation2015; Konaszewski et al., Citation2021), eliminates the symptoms of anxiety and depression and increases self-esteem, gratitude, and optimism (Bonanno et al., Citation2012; Konaszewski et al., Citation2021; Shaker et al., Citation2020).

Given the crucial role resilience plays in establishing biopsychospiritual balance in adverse conditions, evidence-based treatments are imperative. Narrative therapy (Shaker et al., Citation2020; Jalali et al., Citation2019; Looyeh et al., Citation2012; Zang et al., Citation2013) has been the subject of extensive scientific evaluation. Resilience is strongly linked to the meaning we give to adverse life events (Cicchetti, Citation2015; Werner, Citation1995). By stressing the stories of people's lives, regarding people as the experts in their own lives, and perceiving problems as separate from people, narrative therapy is a method of counselling and community work that tries to address the meaning people give to their experiences (White, Citation1988; White & Epston, Citation1990). The foundation of narrative therapy is that people are ‘interpreting beings,’ connecting the events of their daily lives over time to make meaning of their experiences. This ‘narrative’ is a thread connecting the events to create a story (see www.dulwichcentre.com.au). According to narrative therapists, people have multiple stories about their lives and relationships that all form at once. Narrative therapists work to help people lessen the impact of troublesome stories in their lives. Narrative therapists focus on the history of abilities, beliefs, values, and commitments to help people alleviate the effects of problem stories in their lives. They also highlight the resources and knowledge within individuals, families, and communities. Narrative therapy is an effective approach for several mental health problems in children, such as depression, PTSD, attachment disorders, and violence in the family (Vetere & Dowling, Citation2005). Similarly, prior studies have found this approach to be effective in traumatized populations (Aponte & Shawn, Citation2017; Ghandehari et al., Citation2018; Sahin & McVicker, Citation2011).

Research evidence also suggests that narrative approaches to intervention, where the child or young person is not viewed in terms of their ‘problems’, are particularly effective in reducing stigma (Ertl et al., Citation2011). According to Ghandehari et al. (Citation2018), narrative therapy increases the resilience of women victims of sexual violence. However, it should be emphasized that studies of the impact of narrative therapy on resilience rarely include the young population, especially orphaned and abandoned children who are institutionalized globally, and none was explicitly conducted in Rwanda. The primary goal of the current study was to investigate the hypothesis that narrative therapy is superior to waitlist conditions in increasing resilience. As Narrative Therapy is still a new approach but is attracting the attention of the University of Rwanda and other institutions such as SOS Villages, this research will provide some essential information on the efficacy and results of using narrative therapy. It will also stimulate academic debates and further studies about the approach’s effectiveness across various psychological conditions.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedures

A single-blind, parallel-group, randomized controlled trial was conducted, with the independent evaluators blinded to the treatment condition to maintain objectivity. All work was completed with the formal ethical approval of the Institutional Review Board of the College of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of Rwanda (CMHS/IRB/547/2019), and the clinical trial has been registered as legislation requires (name of registry: The Pan African Clinical Trial Registry; URL: www.pactr.org; registration number: PACTR202107499406828). Furthermore, the authorization to conduct the research was provided by the director of SOS Children’s Village Rwanda.

Assessments at baseline and ten weeks after treatment were conducted by two independent interviewers who were not involved in running the trial. The interviewers were blinded for the allocation of children to minimize the bias. Before data collection, signed assent and consent forms were respectively obtained from SOS children and SOS Mothers. In principle, Narrative Therapy has ten recommended sessions, and only one session is recommended weekly. Therefore, ten sessions were planned for ten weeks to improve participants’ resilience.

2.2. Participants

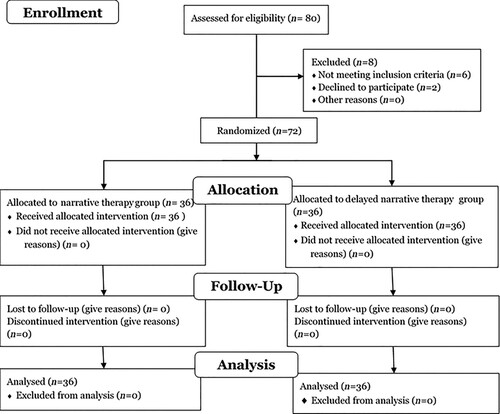

The study participants were randomly selected from SOS children’s villages in Rwanda to partake in this study. Of the 80 orphaned and abandoned children screened for eligibility, eight children did not meet the inclusion criteria (). The inclusion criteria included being aged 6–15 years, being fostered in SOS Children’s villages for at least one year and never receiving Narrative Therapy. This was a two-arm study, and the allocation fraction was 1:1 intervention and control. The allocation was randomly, and computer generated. One arm served as a delayed narrative therapy group (n = 36) while the other received the narrative therapy treatment (narrative therapy group, n = 36). Allocation concealment was ensured as the researchers did not release the randomisation code before the participants provided the consent and assent forms to avoid the influence of knowledge of the group to which they were allocated if they joined the trial. The final sample comprised 72 orphaned and abandoned children (47 boys, 23 females, mean age = 10, range = 6–15), ().

2.3. Treatment

2.3.1. Narrative therapy

Narrative Therapy is a short-term, component-based intervention that involves ten weekly 90–100-minute sessions (White & Keeling, Citation2008). The therapeutic components include re-authorizing (i.e. self-management and self-identity), externalizing the problem (i.e. detachment from the problem and perception of the problem as something else), and deconstruction (i.e. externalizing stories about the identity and person’s dominant narrative). For the current study, narrative therapy was offered to a group of 12 children (each). One psychologist who completed the certified narrative therapy training facilitated the group narrative therapy sessions.

2.3.2. Delayed narrative therapy condition

The SOS children village staff was in charge of all children (i.e. both the waitlist and intervention groups) with the relaxation activities (psychodrama, singing, play, dancing, and drawings) conditions. However, the narrative group children received additional narrative therapy packages weekly. For ethical reasons, the delayed narrative therapy group started the treatment immediately after the end of the intervention group treatment period (10 weeks later).

2.4. Data collection tools

The research tools comprised a socio-demographic questionnaire and ‘the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (the CYRM-28)’. As narrative therapy is a resilience-oriented approach, the current study was interested in resilience. Thus, no other measure was taken apart from the CYRM-28. The tools were translated and back-translated by four and two bilingual psychologists, respectively, and the discrepancies were resolved. The tool was administered to children in the Narrative Therapy group (36 children) and delayed narrative therapy group (36 children) at the baseline and endline.

2.4.1. The socio-demographic questionnaire

The socio-demographic questionnaire collected information on independent variables such as age, gender, years fostered in SOS Children’s Village, and parental status (i.e. orphan, single parent and both parent).

2.4.2. The child and youth resilience measure (CYRM-28).

This is the Child, and Youth Resilience Measure with 28 items (CYRM-28) used to measure children’s resilience levels. The CYRM-28 has three sub-scales, including ‘(a) individual capacities or resources, (b) relationships with primary caregivers and (c) contextual factors that facilitate a sense of belonging’ (Liebenberg et al., Citation2012; Ungar & Liebenberg, Citation2011). The CYRM-28 asks participants to identify the extent to which 28 statements describe them, and each is scored using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 ‘describes me not at all’ to 5 ‘ describes at a lot’. Sample items are ‘I can solve problems without hurting myself or other people.’, ‘I get on with people around me.’ and ‘In my environment, I know where to go to get help.’ This study used the full-scale summed score ranging from 28 to 140, with a higher score indicating the greater presence of resilience processes. Several validation studies have shown that the internal reliability of this scale varies between 0.71 and 0.87 in a sample of children and youth (Kaunda-Khangamwa et al., Citation2020; Sanders et al., Citation2017). The Cronbach’s Alpha was 0.83 in the current sample.

2.5. Data analysis

In congruence with the findings of our pilot study, we calculated the sample size based on the following assumptions: effect size of d = .2 for the delayed narrative therapy group and d = 1.00 for the narrative therapy group, suggesting an effect size of about 0.8 between conditions. Assuming power = 0.89, alpha = 0.05, two comparison groups, and two measurement time points, we needed 33 participants per condition (66 total). Compensation for a possible clustering effect (9%) raised the required sample size to 72 participants. A factorial repeated measure ANOVA within SPSS version 28 was conducted, with the group as the between-subjects factor and time (total pre- and post-treatment scores on the resilience measures) as the within-subjects factor. Preliminary analyses indicated no missed data and no violations of assumptions regarding ‘normality and homogeneity of regression slopes’. In case of violation of the assumption of sphericity in the factorial repeated measures ANOVA, a Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied (Field, Citation2009). We used partial eta squared (ηp2) to assess the magnitude of the effect and considered 0.14 or more to be the large effect, 0.06 to be the medium effect, and 0.01 or more to be the small effect (Lakens, Citation2013; Cohen, Citation1988). Within-subject effect sizes were established by calculating the difference in means divided by the pooled within-group standard deviation (Cohen, Citation1988). A significance level of α = .05 (two-sided) was adopted for all statistical analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

As shown in , all participants in both narrative therapy (NT) and delayed narrative therapy (DNT) groups had completed the baseline (T1) and endline assessment (T2). The sample was dominated by boys in both groups (NT: 19/36 and DNT: 24/36). The mean age in the current sample was ten years (SD = 1.6), and most of the respondents in both groups were aged 12–15 years (NT: 17/36 and DNT: 22/36), followed by 9–11 years (NT: 17/36 and DNT: 10/36). In both groups, many respondents have been institutionalized in SOS Villages for three years (NT: 19/36 and DNT: 17/36), and one year (NT: 11/36 and DNT: 11/36). Following randomization, there were no significant differences between the two groups in socio-demographic characteristics (all p-values > .05).

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics.

3.2. Treatment effects

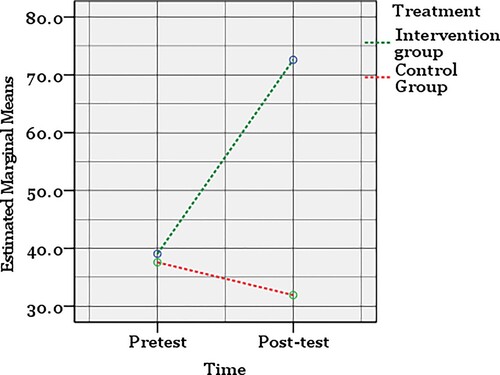

The results emerged from ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of time [F (1, 70) = 354.964, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.835], and group [F (1, 70) = 354.964, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.835] for resilience total scores. Of interest, there was a significant time by group interaction effect for psychological resilience [F (1, 70) = 702.079, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.909].

As shown in and , pairwise comparison analyses within-group showed a significant increase in resilience in the narrative therapy group ([NT], mean difference (MD) = −33.556, p < .001), and the effect size were relatively large (Cohen’s dz = 5.97) in this group. Within the delayed narrative therapy group (DNT), there was a significant decrease in resilience (MD = 6.55, p < .001), and the effect size was medium (Cohen’s dz = 0.75). The same analyses between groups indicated no significant differences during the baseline (MD = 1.47, p = .403), but the difference was significantly large at the endline (MD = 40.69, p < .001).

Table 2. Levels of psychological resilience at baseline and endline with change and effect sizes.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate narrative therapy's effect on the resilience of orphaned and abandoned children living in SOS Children’s Villages Rwanda. Based on findings, it was concluded that narrative therapy increases orphaned and abandoned children’s resilience. Despite the lack of similar studies on orphaned and abandoned children, our findings were in congruence with the results of similar studies conducted among adults in this field (Aponte & Shawn, Citation2017; Banker et al., Citation2010; Ghandehari et al., Citation2018; Khodabakhsh et al., Citation2015). Similarly, a recent study has found that narrative therapy increases resilience among women victims of sexual violence (Ghandehari et al., Citation2018). The hypothesis may be explained by the fact that narrative therapy offers this possibility for orphaned and abandoned children to identify ‘unpleasant internal experiences’ without any effort to control them. Doing so reduces the threat of the experiences, and their effect on children’s lives will be less threatening.

Our findings also show that the level of resilience of children in the delayed narrative therapy group has significantly reduced during the treatment period (M1 = 37.58, M2 = 31.91), which can be explained by institutionalization and, orphanhood and abandonment (Nsabimana et al., Citation2019; Shulga et al., Citation2016; Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2011). Although SOS Children’s Villages is an institutional environment that provides for stable and consistent caregiving, children may be deprived of a regular family life embedded in a regular social environment that, in the absence of narrative therapy, may affect the child’s resilience (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2011). Also, the lack of proper physical resources, unfavorable and inconsistent staffing patterns, and socially and emotionally insufficient caregiver-child interactions are all examples of ‘structural neglect’ that frequently affects children in institutions (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2011). The majority of institutions have many children to each caregiver. For instance, some SOS Children's Villages are designed as a collection of family homes with 6–8 children living in each home, supervised by the same caregiver around-the-clock, seven days a week (SOS, Citation2020). There may be limited access to children of varied ages and developmental stages since groups tend to be homogenous regarding age or disability status. Any single child's caregiver will frequently change, making it challenging to form friendly relationships with children. Most caregivers have no formal training in child care, resulting in subpar quality of care. Most caregivers tend to care children as duty, failing to meet their emotional needs (Van IJzendoorn et al., Citation2011). To create wider family networks that can care for orphaned children, several SOS Children's Villages combine this institutional system with family-building programmes (SOS, Citation2020). However, despite being an ideal and costly institutional setting, SOS Children's Villages still needs to rely heavily on narrative therapy for the beneficiaries’ health.

The main objective of narrative therapy is the well-being and happiness of children; therefore, the factors that lead to the superior compliance of individuals with the requirements and threats of life are the components of this approach. Narrative therapy methods also comprise the ‘telling, listening, re-telling, and re-listening of stories.’ Doing so provides materials and resources to trace meaning, understanding, and insight. The central part of the approach is to enlighten people about the connection between their stories with others and their own lives. It can also be said that through this approach, participants were able to rediscover their abilities to work normally by finding their abilities, developing healthy thinking, improving connection, a sense of self-value, self-respect, and empowerment as the components of resilience. It has been found that besides having attitudes, thoughts, and actions that promote their wellbeing and mental health, resilient people are advanced in their ‘ability to withstand, adapt to, and recover from stress and adversity and maintain a state of mental health by using effective coping strategies’ (Aponte & Shawn, Citation2017). Prior studies have found that narrative therapy helps children regain a sense of power over their daily lives (Baird, Citation1996; Sahin & McVicker, Citation2011).

Clinically, the contention is to train children to gain traits such as ‘prediction, persistence to overcome obstacles, tolerance against failures and problems, and self-efficacy’, which help them in difficulties and strengthen resilience. Resilient children have different ways of reasoning and attitudes in facing adverse conditions. Instead of making a problem a tragedy and being caught by its consequences, they pay more attention to themselves and their abilities. For example, such people may consider a hazardous position an opportunity, not a threat, and experience success instead of anxiety in difficulties. Hence, resilience leads to appropriate adaptation in facing problems and is more than simply avoiding negative consequences.

4.1. Study strength and limitations

The strengths of this study are numerous: firstly, the sample size was satisfactory for the statistical analysis applied in this study, and this sample was comparable to the previous studies conducted on narrative therapy among children (Looyeh et al., Citation2012; Ghandehari et al., Citation2018). Secondly, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the impact of narrative therapy on the resilience of orphaned and abandoned children in post-conflict countries worldwide. However, this study had several limitations. First, this study did not assess the efficacy of narrative therapy on depression and PTSD symptoms, which would be high in the current sample. Second, due to the lack of a follow-up stage, the persistence of the therapeutic effect was not measured in this study. Third, the study was conducted among orphaned and abandoned children fostered in SOS Children’s villages. There should be caution in generalizing the study results to others living in the community. Lastly, this study might have limitation in the analysis performed; although the use of two-way ANOVA for analyzing the resilience scale total scores informed us about the main effect and the interaction effect, future studies analyzing resilience subscales scores using a Multi-variate ANOVA (MANOVA) is recommended.

5. Conclusion

Our findings highlight a notable effect of narrative therapy on psychological resilience in the narrative therapy group and the worsening of these conditions in the delayed narrative therapy group. Therefore, the principles and techniques of narrative therapy increase resilience among abandoned children. This study showed that this intervention could be useful for abandoned children. Based on the results of this study, health professionals and organizations working with orphaned and abandoned children should initiate or reinforce practices of this therapy as management solutions for children’s orphanhood and abandoned lives for improvement and continuity of their lives.

Data availability statement

Data are not publicly available due to the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Restricted data are available upon reasonable request from the PIs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aiena, B. J., Baczwaski, B. J., Schulenberg, S. E., & Buchanan, E. M. (2015). Measuring resilience with the RS-14: A tale of two samples. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2014.951445

- Aponte, D. A., & Shawn, P. (2017). Narrative approaches to counseling survivors of child sexual abuse. Wisdom in Education, 7(2), 1–9. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/ wie/vol7/iss2/2.

- Baird, F. (1996). A narrative context for conversations with adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Progress-Family Systems Research and Therapy, 5(1), 51–71.

- Banker J. E., K., & Allen, C. E., & R, K. (2010). Dating is hard work: A narrative approach to understanding sexual and romantic relationships in young adulthood. Contemporary Family Therapy, 32(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-009-9111-9

- Block, J. H., & Block, J. (1980). The role of ego-control and ego resiliency in the organization of behavior. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology (pp. 39–101). Lawrence Erlbaum Associated, Inc.

- Bonanno, G. A., & Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual research review: Positive adjustment to adversity–trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 378–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12021

- Bonanno, G. A., Kennedy, P., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Lude, P., & Elfström, M. L. (2012). Trajectories of resilience, depression, and anxiety following spinal cord injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 57(3), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029256

- Chmitorz, A., Kunzler, A., Helmreich, I., Tüscher, O., Kalisch, R., Kubiak, T., Wessa, M., & Lieb, K. (2018). Intervention studies to foster resilience - A systematic review and proposal for a resilience framework in future intervention studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 78–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.11.002

- Cicchetti, D. (2015). In D. Cicchetti, & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental Psychopathology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge Academic.

- Earvolino-Ramirez, M. (2007). Resilience: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 42(2), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2007.00070.x

- Ertl, V., Pfeiffer, A., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2011). Community implemented trauma therapy for former child soldiers in northern Uganda. A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(5), 503–512. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1060

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics through SPSS: (and sex and drugs and rock’n’roll). Thousand Oaks.

- Ghandehari, M., Moosavi, L., Jazi, F. R., Arefi, M., & Ahmadzadeh, S. (2018). The effect of narrative therapy on resilience of women who have referred to counseling centers in isfahan. International Journal of Educational Psychology Res, 4, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.4103/2395-2296.204124

- Goldman, P. S., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Bradford, B., Christopoulos, A., Ken, P., Cuthbert, C., Duchinsky, R., Fox, N. A., Grigoras, S., Gunnar, M. R., Ibrahim, R. W., Johnson, D., Kusumaningrum, S., Agastya, N., Mwangangi, F. M., Nelson, C. A., Ott, E. M., Reijman, S., van IJzendoorn, M. H., … Sonuga-Barke, E. (2020). Institutionalisation and deinstitutionalisation of children 2: Policy and practice recommendations for global, national, and local actors. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(8), 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30060-2

- Hope and Homes for Children. (2016). impact report 2016/17. https://www.hopeandhomes.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Impact-Report-2016-Hope-and-Homes-for-Children.pdf.

- Hu, T., Zhang, D., & Wang, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the trait resilience and mental health. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.039

- Jackson, D., Firtko, A., & Edenborough, M. (2007). Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 60(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x

- Jalali, F., Hashemi, S. F., & Hasani, A. (2019). Narrative therapy for depression and anxiety among children with imprisoned parents: A randomised pilot efficacy trial. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 31(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2019.1678474

- Kalisch, R., Baker, D. G., Basten, U., Boks, M. P., Bonanno, G. A., Brummelman, E., Chmitorz, A., Fernàndez, G., Fiebach, C. J., Galatzer-Levy, I., Geuze, E., Groppa, S., Helmreich, I., Hendler, T., Hermans, E. J., Jovanovic, T., Kubiak, T., Lieb, K., Lutz, B., … Kleim, B. (2017). The resilience framework as a strategy to combat stress-related disorders. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(11), 784–790. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0200-8

- Kalisch, R., Müller, M. B., & Tüscher, O. (2015). A conceptual framework for the neurobiological study of resilience. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, e92. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1400082X

- Kaunda-Khangamwa, B. N., Maposa, I., Dambe, R., Malisita, K., Mtagalume, E., Chigaru, L., Munthali, A., Chipeta, E., Phiri, S., & Manderson, L. (2020). Validating a child youth resilience measurement (CYRM-28) for adolescents living with HIV (ALHIV) in urban Malawi. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1896. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01896

- Khodabakhsh M., K., Tirtashi, F., Hashjin, E. N., & K, H. (2015). The effectiveness of narrative therapy on increasing couples intimacy and its dimensions: Implication for treatment. Journal of Family Counselling Psychotherapy, 4, 608–632.

- Konaszewski, K., Niesiobędzka, M., & Surzykiewicz, J. (2021). Resilience and mental health among juveniles: Role of strategies for coping with stress. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 19(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01701-3

- Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

- Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., & Van de Vijver, F. (2012). Validation of the child and youth resilience measure-28 (CYRM-28) among Canadian youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 22(2), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731511428619

- Looyeh, M. Y., Kamali, K., & Shafieian, R. (2012). An exploratory study of the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the school behavior of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(5), 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2012.01.001

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00164

- Nsabimana, E., Rutembesa, E., Wilhelm, P., & Martin-Soelch, C. (2019). Effects of institutionalization and parental living status on children‘s self-esteem, and externalizing and internalizing problems in Rwanda. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 442. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00442

- Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., Bisconti, T. L., & Wallace, K. A. (2006). Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 730–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730

- Sahin, Z., & McVicker, M. (2011). An integration of narrative therapy and positive psychology with sexual abuse survivors. In T. Bryant-Davis (Ed.), Surviving Sexual Violence: A Guide to Recovery and Empowerment (pp. 217–232). Rowman & Littlefield.

- Sanders, J., Munford, R., Thimasarn-Anwar, T., & Liebenberg, L. (2017). Validation of the child and youth resilience measure (CYRM-28) on a sample of at-risk New Zealand youth. Research on Social Work Practice, 27(7), 827–840. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731515614102

- Shaker, J., Ahmadi, S. M., Maleki, F., Hesami, M. R., Moghadam, A. P., Ahmadzade, A., Shirzadi, M., & Elahi, A. (2020). Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on depression, quality of life, and anxiety in people with amphetamine addiction: A randomized clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 45(2), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.30476/IJMS.2019.45829

- Shulga, T. I., Savchenk, D. D., & Filinkova, E. B. (2016). Psychological characteristics of adolescents orphans with different experience of living in a family. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(17), 10493–10504.

- SOS Children’s Villages. (2017). Children are in need of protection. https://www.sos-childrensvillages.org/where-we-help/africa/rwanda

- SOS. (2020). SOS Children‘s Villages, Rwanda (Issue September). https://www.soschildrensvillages.ca/sites/default/files/na_rwanda_kigali_2020_end.pdf?utm_source = info&utm_medium = email&utm_campaign = sponsor-field-update-1.

- TMM. (2019). Evaluation of the Tubarerere Mu Muryango. https://www.unicef.org/rwanda/media/1641/file/TMM Summary Evaluation Phase I.pdf.

- Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L. (2011). Assessing resilience across cultures using mixed methods: Construction of the child and youth resilience measure. Journal of Multiple Methods in Research, 5(2), 126–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689811400607

- UNICEF. (2017). Situation Analysis of Children in Rwanda 2017. https://www.unicef.org/rwanda/media/396/file/2018-Situation-Analysis-Rwanda-Children-Full-Report.pdf.

- Van IJzendoorn, M. H., Palacios, J., Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Gunnar, M. R., Vorria, P., McCall, R. B., LeMare, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Dobrova-Krol, N. A., & Juffer, F. (2011). Children in institutional care: Delayed development and resilience. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 76(4), 8–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.2011.00626.x

- Vetere, A., & Dowling, E. (2005). Narrative Therapies with Children and Their Families: A Practitioner‘s Guide to Concepts and Approaches. Routledge.

- Werner, E. E. (1995). Resilience in development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4(3), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10772327

- White, M. (1988). The externalizing of the problem and the re-authoring of lives and relationships. Dulwich Centre Newsletter, Summer.

- White, M., & Epston, D. (1990). Narrative Means to Therapeutic Ends. W.W. Norton & Co.

- White, M., & Keeling, M. L. (2008). Maps of narrative practice by michael white. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 19(4), 404–405. https://doi.org/10.1080/08975350802475114

- Zang, Y., Hunt, N., & Cox, T. (2013). A randomised controlled pilot study: The effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy with adult survivors of the Sichuan earthquake. BMC Psychiatry, 13, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-41