ABSTRACT

Background: Racial discrimination is a traumatic stressor that increases the risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but mechanisms to explain this relationship remain unclear. Peritraumatic dissociation, the complex process of disorientation, depersonalization, and derealization during a trauma, has been a consistent predictor of PTSD. Experiences of frequent racial discrimination may increase the propensity for peritraumatic dissociation in the context of new traumatic experiences and contribute to PTSD symptoms. However, the role of peritraumatic dissociation in the relationship between experiences of discrimination and PTSD has not been specifically explored.

Objective: The current study investigated the role of peritraumatic dissociation in the impact of racial discrimination on PTSD symptoms after a traumatic injury, and the moderating role of gender.

Method: One hundred and thirteen Black/African American individuals were recruited from the Emergency Department at a Level I Trauma Center. Two weeks after the trauma, participants self-reported their experiences with racial discrimination and peritraumatic dissociation. At the six-month follow-up appointment, individuals underwent a clinical assessment of their PTSD symptoms.

Results: Results of longitudinal mediation analyses showed that peritraumatic dissociation significantly mediated the effect of racial discrimination on PTSD symptoms, after controlling for age and lifetime trauma exposure. A secondary analysis was conducted to examine the moderating role of gender. Gender was not a significant moderator in the model.

Conclusions: Findings show that racial discrimination functions as a stressor that impacts how individuals respond to other traumatic events. The novel results suggest a mechanism that explains the relationship between racial discrimination and PTSD symptoms. These findings highlight the need for community spaces where Black Americans can process racial trauma and reduce the propensity to detach from daily, painful realities. Results also show that clinical intervention post-trauma must consider Black Americans’ experiences with racial discrimination.

HIGHLIGHTS

Peritraumatic dissociation operates as a mechanism through which racial discrimination predicts posttraumatic symptoms in an adult trauma sample.

Racial discrimination functions as a stressor that increases the risk for trauma-related symptoms.

The lived experiences of Black Americans elicit the use of emotional detachment strategies that may mitigate effects of racial discrimination but increase the risk for peritraumatic dissociation.

Antecedentes: La discriminación racial es un factor estresante traumático que aumenta el riesgo de trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), pero los mecanismos para explicar esta relación siguen sin estar claros. La disociación peritraumática, el proceso complejo de desorientación, despersonalización y desrealización durante un trauma ha sido un predictor consistente del TEPT. Las experiencias de discriminación racial frecuente pueden aumentar la propensión a la disociación peritraumática en el contexto de nuevas experiencias traumáticas y contribuir a los síntomas del TEPT. Sin embargo, no se ha explorado específicamente el papel de la disociación peritraumática en la relación entre las experiencias de discriminación y el TEPT.

Objetivo: El presente estudio investigó el papel de la disociación peritraumática en el impacto de la discriminación racial en los síntomas del TEPT después de un evento traumático, y el papel moderador del género.

Método: Ciento trece individuos afroamericanos fueron reclutados del Departamento de Emergencias en un Centro de Trauma de Nivel I. Dos semanas después del trauma, los participantes reportaron sobre sus experiencias con la discriminación racial y la disociación peritraumática. En la cita de seguimiento a los seis meses, las personas se sometieron a una evaluación clínica de sus síntomas de TEPT.

Resultados: Los resultados de los análisis de mediación longitudinal mostraron que la disociación peritraumática mediaba significativamente el efecto de la discriminación racial en los síntomas del TEPT, después de controlar la edad y la exposición al trauma a lo largo de la vida. Se realizó un análisis secundario para examinar el papel moderador del género. El género no fue un moderador significativo en el modelo.

Conclusiones: Los hallazgos muestran que la discriminación racial funciona como un factor estresante que afecta la forma en que las personas responden a otros eventos traumáticos. Los nuevos resultados sugieren un mecanismo que explica la relación entre la discriminación racial y los síntomas del TEPT. Estos hallazgos resaltan la necesidad de espacios comunitarios donde los afroamericanos puedan procesar el trauma racial y reducir la propensión a desconectarse de las dolorosas realidades diarias. Los resultados también muestran que la intervención clínica postraumática debe considerar las experiencias de los afroamericanos con la discriminación racial.

背景:种族歧视是一种创伤性应激源,会增加创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 的风险,但解释这种关系的机制仍不清楚。创伤期解离,即创伤期间迷失方向、人格解体和现实感丧失的复杂过程,是 PTSD 一贯的预测因素。频繁的种族歧视经历可能会增加新的创伤经历的背景下创伤后解离的倾向,并导致 PTSD 症状。 然而,创伤期解离在歧视经历和 PTSD 之间的关系中的作用尚未得到具体探讨。

目的:本研究考查创伤后解离在种族歧视对创伤后 PTSD 症状的影响中的作用,以及性别的调节作用。

方法:从一级创伤中心的急诊科招募了 113 名黑人/非裔美国人。创伤发生两周后,参与者自我报告了他们在种族歧视和创伤后解离方面的经历。在六个月的随访预约中,个体接受了对其 PTSD 症状的临床评估。

结果:纵向中介分析的结果表明,在控制了年龄和终身创伤暴露后,创伤期解离显著中介了种族歧视对 PTSD 症状的影响。进行了二级分析以考查性别的调节作用。此模型中性别不是显著调节因素。

结论:研究结果表明,种族歧视是一种应激源,会影响个人对其他创伤事件的反应。这一新颖新结果提出了一种解释种族歧视与 PTSD 症状之间关系的机制。这些发现强调了对美国黑人可以处理种族创伤并减少从日常痛苦现实解离倾向的社区空间的需求。 结果还表明,创伤后临床干预必须考虑美国黑人的种族歧视经历。

1. Introduction

Globally, an estimated 70% of individuals experience a traumatic event in their lifetime (Benjet et al., Citation2016; Kessler et al., Citation2017) yet the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is not as widespread with an approximate prevalence of 8% in the United States each year (Kilpatrick et al., Citation2013). It is important, however, to consider racial/ethnic differences given that Black Americans have a higher lifetime prevalence of PTSD compared to White Americans (Carter, Citation2007; Roberts et al., Citation2011). This disparity could reflect more frequent exposures to trauma, a greater risk of PTSD development once exposed to a trauma or a combination of both. Although Black Americans have a greater conditional risk for PTSD after experiencing a trauma, White Americans experience a greater number of traumatic events (Roberts et al., Citation2011). In other words, higher rates of PTSD in Black Americans cannot simply be attributed to the frequency of trauma exposure.

A critical analysis of the definition of trauma, though, reveals prior research may have underestimated the frequency of trauma for Black Americans. Specifically, the current diagnostic criteria for PTSD in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) do not capture the full range of traumatic experiences and omit experiences which affect Black Americans (Abdullah et al., Citation2021; Holmes et al., Citation2016). Criterion A enumerates specific conditions including direct or indirect ‘exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence’ (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013, p. 271). These very specific criteria of trauma preclude the recognition of other events that may also produce posttraumatic stress symptoms, specifically racial discrimination, which may contribute to an increased risk of PTSD (Carter et al., Citation2021; Roberts et al., Citation2011; Sibrava et al., Citation2019). Racial discrimination refers to unequal treatment received by individuals on the basis of their race (Jones, Citation1997; Pager & Shepherd, Citation2008) and impacts marginalized communities of colour in many settings and across interpersonal and structural levels (Hirsch & Cha, Citation2008). Indeed, 70–90% of Black Americans report experiencing racial discrimination (Carter et al., Citation2016; Lee et al., Citation2019).

Several recent studies have highlighted that racial discrimination can produce PTSD symptoms, including re-experiencing, irritability, hypervigilance, and avoidance (Carter, Citation2007; Cénat et al., Citation2022; Holmes et al., Citation2016; Mekawi et al., Citation2020; Mekawi, Carter Brown et al., Citation2021; Mekawi, Carter, Packard et al., Citation2021; Pieterse et al., Citation2010). However, the nature of racial discrimination is unique as a traumatic stressor. Unlike the current DSM-5 criteria that define a single event as a precipitant to PTSD symptoms, racial discrimination is cumulative and pervasive, operates at several levels, and is upheld by systemic structures (Cénat et al., Citation2022). In fact, experiences of racial discrimination rarely have a finite beginning or end like events listed as ‘Criterion A’ of the DSM-5; thus, individuals are likely to be constantly re-exposed, contributing to the distress of experiencing racial discrimination and its conceptualization as a complex trauma (Carter et al., Citation2021). This is best explained through the Complex Racial Trauma Theory, which posits that racial trauma cannot be understood as individual instances of racism, but rather as the overall experience which impacts Black Americans in all facets of life (Cénat et al., Citation2022).

A clear way that racial discrimination impacts the lives of Black Americans is its role in the recovery of separate traumatic events. Experiences of racial discrimination that occurred prior to a traumatic injury predicted PTSD symptoms several months after the injury even when accounting for demographic variables and lifetime trauma exposure (Bird et al., Citation2021). Bird and colleagues (Citation2021) added evidence to prior empirical work suggesting that chronic racism (also referred to as racial trauma and race-based traumatic stress; Carter et al., Citation2021) is a stressor with long-term impacts on psychological health (Carter et al., Citation2017; Torres et al., Citation2010).

2. Peritraumatic dissociation as a mechanism

As noted, empirical research has indicated that racial discrimination is associated with PTSD symptoms, but what is less understood are the mechanisms linking these constructs. One posited mechanism is emotional dysregulation such that those experiences of racial discrimination deplete resources for adequate emotional processing, increasing vulnerability to negative emotionality and later PTSD (Mekawi et al., Citation2020). One factor that has been significantly related to emotional regulation is dissociation, which generally refers to the ‘disruption or discontinuity’ of emotion, sensations, identity, perception, thoughts, and memories (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Based on a meta-analytic review, dissociation is related to maladaptive mechanisms of emotional regulation specifically (e.g. disengagement and detachment; Cavicchioli et al., Citation2021) and thus may be the linchpin connecting racial discrimination to later PTSD. It is necessary to further explore how dissociation, as an emotional response, is affected by racial discrimination and later impacts PTSD.

Peritraumatic dissociation specifically has been established as a risk factor for PTSD development in survivors of several forms of trauma (Cardeña et al., Citation2022; Koopman et al., Citation1994; Marmar et al., Citation1994; Nobakht et al., Citation2019; Thompson et al., Citation2017; Ursano et al., Citation1999). Peritraumatic dissociation refers to complex responses occurring during, or immediately following, a traumatic event, including depersonalization, derealization, and emotional numbness (Lensvelt-Mulders et al., Citation2008; Thompson et al., Citation2017). A dissociative response can be protective in the acute aftermath of the trauma as it allows one to detach from intense fear-related emotions, horror, and revulsion (Punamäki et al., Citation2005), but it alters one’s somatic functioning, perception of time and space, and affective reactions. This response can also disrupt normal information processing and inhibit natural recovery after a traumatic event (Mattos et al., Citation2016; Thompson et al., Citation2017). Although peritraumatic dissociation is not necessary for PTSD development, it is one of the most consistent predictors of PTSD, compared to other risk factors such as previous trauma (Breh & Seidler, Citation2007; Otis et al., Citation2012; Ozer et al., Citation2003; Thompson et al., Citation2017). Research has yet to fully understand what factors increase the risk for peritraumatic dissociation and subsequent PTSD symptoms, but difficulties with emotional regulation have emerged as a possible predictor (Jones et al., Citation2018).

Experiencing racial discrimination elicits symptoms of trauma-related dissociation that cannot be explained by exposure to other traumatic events (Carter et al., Citation2020; Polanco-Roman et al., Citation2016). Although this research does not examine peritraumatic dissociation specifically, it offers insight into the relationship between racial discrimination and dissociation. In fact, recent research has found that experiences of racial discrimination significantly predict dissociative symptoms in Black Americans, beyond other forms of trauma, including childhood sexual abuse (Ayawvi et al., Citation2022). Polanco-Roman et al. (Citation2016) propose that incidents of racial discrimination are related to dissociation because experiences of discrimination may elicit the use of strategies such as emotional numbing and detachment. This may initially mitigate the distress caused by racial discrimination and protect minoritized individuals’ well-being. While those strategies may be linked to coping or emotional regulation more generally, detachment from reality/the environment specifically is highly implicated in peritraumatic dissociation. However, this relationship between racial discrimination and dissociation has to date only been examined cross-sectionally, and no studies have prospectively examined the links between peritraumatic dissociation, racial discrimination, and symptoms of PTSD.

3. Gender differences in trauma, dissociation, and PTSD

When discussing these constructs, it is imperative to employ an intersectional lens. Intersectionality was first discussed in the context of Black women’s lived experiences, which cannot be understood by exploring singular, discrete sources of discrimination (either sexism or racism; Crenshaw, Citation1989). Thus, an intersectional approach considers the underlying interaction between systems of oppression (sexism and racism) rather than viewing them as separate experiences. Sexism can be defined as a system of oppression based on gender differences, and disproportionately impacts women (Shorter-Gooden, Citation2004); sexist experiences can range from sexual harassment and assault to everyday demeaning remarks (Swim et al., Citation2001). This is a necessary perspective to consider as research has established clear gender effects regarding trauma and PTSD.

Women display greater rates of PTSD, and this trend is similar among Black women (Breslau et al., Citation1997; Punamäki et al., Citation2005; Tolin & Foa, Citation2006; Valentine et al., Citation2019). Research exploring the mechanisms behind this discrepancy is ongoing. Previous studies show that women experience greater peritraumatic dissociation, and that this propensity may be accounting for the gender differences in PTSD rates (Bryant & Harvey, Citation2003; Irish et al., Citation2011; Lawyer et al., Citation2006; Lilly & Valdez, Citation2012), but other research has not corroborated such findings (Punamäki et al., Citation2005). In addition to differences in rates of peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD, prior empirical work posits variability in the experiences of racism among Black men and women. While experiences of racial discrimination may overlap, findings suggest that Black women are burdened by the unique intersection of racism and sexism (Mekawi, Carter, Brown et al., Citation2021). This may manifest in sexual objectification, the ‘angry Black woman’ stereotype, silencing in professional settings, and assumptions of the Black female body type (Collins, Citation1991; Dale & Safren, Citation2019; Lewis & Neville, Citation2015). On the other hand, the racialization of Black men may be central to their lived experiences, such as unjust racial profiling, police maltreatment, and workplace discrimination (Aymer, Citation2010; Hawkins, Citation2022; Silverstein et al., Citation2022). Overall, Black men and women experience the world differently in the context of racial discrimination, and thus gender differences should be explored.

4. The current study

Currently, there is a significant link between racial discrimination and PTSD that has been established in recent empirical work (Carter, Citation2007; Carter et al., Citation2021) and in the current sample (Bird et al., Citation2021). The current study was not designed to explicate how racial discrimination functions as a traumatic stressor specifically, but rather demonstrate how it affects posttraumatic responses to a separate traumatic event. While research has shown that experiences of racial discrimination increase the risk for PTSD after a traumatic injury, the underlying mechanisms that explain this relationship remain unclear. The current study explored the mechanistic role of peritraumatic dissociation in the impact of racial discrimination on PTSD symptoms, while integrating the role of gender.

The primary aim of this study examined whether peritraumatic dissociation mediated the impact of racial discrimination on PTSD symptoms in a traumatically injured sample of Black Americans. Given the gender differences in experiences of discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptoms, the moderating role of gender in the mediation model was also examined as a secondary aim. It was hypothesized that peritraumatic dissociation would mediate the effect of racial discrimination on PTSD, even after controlling for other lifetime trauma exposure and that gender would significantly moderate the mediational model.

5. Method

5.1. Participants

This current study was derived from a larger project called Imaging Study on Trauma & Resilience (iSTAR). By collecting psychophysical, neurobiological, behavioural, and self-reported data, iSTAR aimed to examine outcomes of traumatic injury, trajectories of PTSD, and factors that influence general mental health concerns (e.g. Bird et al., Citation2021; Webb et al., Citation2022). English-speaking participants between the ages of 18 and 60 years old were recruited from the Emergency Department (ED) at the Medical College of Wisconsin (MCW) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Participants were eligible if they met criterion A of the DSM-5 and scored 3 or higher on the Predicting PTSD Questionnaire (Rothbaum et al., Citation2012). Participants were excluded from the study if they displayed current, or reported a history of, psychotic or manic symptoms, experienced a spinal cord or traumatic brain injury, or tested positive for alcohol, illegal drugs, or narcotics. Additional exclusion criteria included being in the ED due to a self-inflicted injury or sexual assault. Participants were compensated at every visit.

The final sample size of this current study was 113 (M age = 34.34 years, SD = 11.08) which included only participants who identified as Black/African American, completed all required baseline measurements, and underwent the assessment at the follow-up time point six months after baseline. Initially, 130 Black/African American individuals completed baseline assessments, but 17 participants were lost during follow-up. The individuals who did not complete the follow-up assessments did not significantly differ from those who completed follow-up assessments on racial discrimination and lifetime trauma exposure measures. Only participants who identified as Black/African American were included in the study because their unique lived experiences and mental health warrant investigation without comparison to other groups.

The vast majority of participants (72.6%) were in the Emergency Department as a result of a motor vehicle crash. The remaining participants reported their mechanism of injury as assault or altercation (13.3%), domestic violence (5.3%), or other (8.8%). Of the 113 participants, 69 were women (61.1%). The majority of the sample (65.5%) reported a yearly income of $40,000 or lower. 32.7% of participants graduated high school or obtained GED/equivalent diploma, 30.1% had attended some college, 13.2% had an Associate’s degree, and 12.4% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Fourteen per cent of the sample reported a past diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder and/or treatment. At the six months follow-up, 25.7% of the sample (29 individuals) met the criteria for PTSD, using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale DSM-5 (CAPS-5) as discussed below.

As a follow-up to Bird et al. (Citation2021), which provided seminal evidence, the current study used the same sample to expand the scope of this work by exploring the underlying mechanism linking racial discrimination and PTSD symptoms after a traumatic injury, while integrating the role of gender.

5.2. Procedure

Longitudinal data were used for this study. Self-reported data (racial discrimination and peritraumatic dissociation) collected at the 2-week post-trauma time point were utilized. PTSD symptom severity from the 6-month assessment point was used as the outcome variable in order to capture chronicity of posttraumatic symptoms several months after the traumatic injury.

5.3. Measures

5.3.1. Racial discrimination

The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire (PEDQ; Brondolo et al., Citation2005) was used to collect participants’ experiences with racial discrimination. This validated 17-item measure contains 5 subscales of lifetime racial discrimination (Exclusion, Discrimination at Work, Stigmatization, Threat, Unfair Police) and a Total Score. Participants rated their responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very often). This measure assesses the frequency of discriminatory experiences, but not the appraisal of the impact or severity of such experiences. The PEDQ Total Score represents the mean value of responses on the subscale questions. A sample item of the PEDQ asks participants to rate how often ‘[they have] been treated unfairly by co-workers or classmates.’ PEDQ responses from the baseline visit were used for this study, to capture experiences of racial discrimination prior to the traumatic injury. The reliability of this measure was high in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91).

5.3.2. Peritraumatic dissociation

The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire (PDEQ; Marmar et al., Citation1997) measured self-reported recollection of peritraumatic dissociation during the index trauma that brought participants to the ED (e.g. motor vehicle crash). The PDEQ is a 10-item validated measure that asks respondents to rate on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Not at all true) to 5 (Extremely true) how much each statement related to their experience during the traumatic event. Scores represent a sum (the range for this sample was 10–50). A sample item of the PDEQ states, ‘I had moments of losing track of what was going on. I ‘blanked out’ or ‘spaced out’ or in some way felt that I was not part of what was going on.’ The Cronbach’s alpha for this sample was 0.85.

5.3.3. Posttraumatic symptoms

PTSD symptom severity was measured using the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Weathers et al., Citation2013) administered at the 6-month visit. The CAPS-5 is a semi-structured clinical interview containing 30 items designed to assess the frequency, intensity, and duration of current posttraumatic stress symptoms (Weathers et al., Citation2018). CAPS-5 aims to capture the severity of the four symptom clusters as defined in the DSM-5 (reexperiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, and alterations in negative mood). CAPS-5 yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 with this current sample.

CAPS-5 was administered to the participants six months after the baseline appointment. All CAPS-5 interviews were administered by 14 interviewers who identified as White and were majority female. Each interviewer completed an online training offered by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Additionally, each interviewer administered two mock CAPS-5 interviews that were reviewed by postdoctoral clinical psychologists. Lastly, each interviewer also observed two live interviews conducted by experienced CAPS-5 interviewers. Research staff also reviewed 20% of the interviews, yielding high interrater reliability (0.96; 95% CI [0.93, 0.98]).

The interviewers scored both intensity and frequency of reexperiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal, and negative mood symptoms in the past month, as reported by the participants. For this study, intensity and frequency scores were merged to create a comprehensive PTSD symptom severity score (the range for this sample was 0–57).

5.3.4. Lifetime trauma exposure

The Life Events Checklist (LEC; Gray et al., Citation2004) was utilized to capture lifetime trauma exposure in the sample. This is a self-reported, validated measure that contains 17 items describing stressful, traumatic events (e.g. natural disasters, combat, sexual assault, life-threatening illness). Participants reported if they ever experienced, witnessed, learned about, or were exposed to each item as part of their job. Based on previous literature (Bird et al., Citation2021; Weis et al., Citation2022), scores were weighted to heavily reflect direct and witnessed experiences as well as those that participants learned happened to a loved one. The LEC was used as a covariate in the analyses to isolate the role of racial discrimination in the model and avoid misattributing results to previous, general trauma exposure. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample was 0.87.

5.4. Analytic strategy

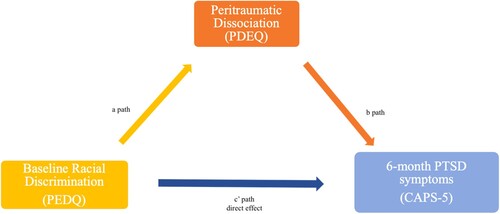

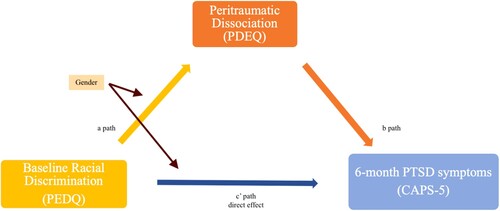

To answer the proposed aims, the following analytic strategy was implemented. Preliminary bivariate correlations were conducted in order to examine the associations between racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptoms. T-tests were also conducted to examine gender differences in racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD. Then, a longitudinal mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS (Hayes & Rockwood, Citation2017). PROCESS is an SPSS macro, computational addition that uses bootstrapping to analyse direct, indirect, conditional, and total effects in moderation and mediation analyses (Hayes & Rockwood, Citation2017). Model 4 was conducted to examine the indirect effect of racial discrimination on PTSD symptoms via peritraumatic dissociation (Hayes, Citation2013). Model is shown in . A subsequent moderated mediation analysis was conducted using PROCESS model 8 to assess gender as a moderator (Hayes, Citation2013; Hayes & Rockwood, Citation2017). Model 8 was chosen in order to explore the moderating role of gender on the direct a path between racial discrimination and peritraumatic dissociation, and the direct c path. The relationship between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD is consistent, such that gender was not expected to moderate that path. Model 8 is shown in . Lifetime trauma exposure and age were used as covariates in the mediation model to isolate the effect of racial discrimination.

6. Results

6.1. Correlations and t-tests

Preliminary bivariate correlations were conducted to examine the associations between racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptoms. Notably, total racial discrimination (RD) was significantly associated with peritraumatic dissociation (r = 0.289, p = .002). All subscales of the PEDQ racial discrimination measure were also significantly associated with peritraumatic dissociation, except the Discrimination at Work subscale. Moreover, peritraumatic dissociation was correlated with PTSD symptom severity (r = 0.445, p < .001). Lastly, total racial discrimination (r = 0.263, p = .002) and the Exclusion/Rejection (r = 0.278, p = .003) and Threat/Aggression (r = 0.298, p < .001) subscales were significantly correlated with total PTSD symptoms. Correlations are in .

Table 1. Bivariate correlations of racial discrimination (RD), peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptom severity.

Next, an independent samples t-test was conducted to understand gender differences related to racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD. The Stigmatization and Unfair Policing subscales showed gender differences. Men (M = 1.81; SD = 1.00) reported higher scores than women (M = 1.47; SD = 0.75) on the Stigmatization subscale (t(111) = 2.058, p = .042 < 0.05). The Unfair Policing subscale yielded a significant gender difference (t(111) = 3.754, p < .001 < .05), such that men reported higher scores (M = 2.93; SD = 1.58) than women (M = 1.93; SD = 1.25). There were no gender differences in other subscales or peritraumatic dissociation. PTSD symptom severity was trending toward significance, (t(111) = −1.96, p = .053), with women reporting greater symptom severity (M = 14.38; SD = 9.36) than men (M = 10.05; SD = 12.61). Results of the independent samples t-tests can be found in .

Table 2. Gender Differences of racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptom severity.

6.2. Mediation analyses

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the impact of racial discrimination on PTSD, as mediated by peritraumatic dissociation. All mediation models included age and lifetime trauma exposure as covariates. It was important to covary for age and lifetime trauma exposure (using Life Events Checklist; Gray et al., Citation2004) in order to isolate the effect of racial discrimination on the PTSD symptomatology, rather than general stress and previous trauma. This also minimizes the possibility of attributing the indirect effect to variables other than the predictor in this model.

Primarily, the results show that peritraumatic dissociation was a significant mediator of the effect of total racial discrimination on total PTSD symptom severity (B = 1.372, CI [0.210, 2.722], SE = 0.647). Results can be found in .

Table 3. Model summary of the indirect effect of total racial discrimination on PTSD symptom severity.

6.3. Moderated analyses mediation

The secondary aim was to examine the moderating role of gender in the mediational model, after establishing the mechanistic role of peritraumatic dissociation. Using PROCESS model 8 (Hayes, Citation2013), the role of gender in moderating the link between the direct a path and the direct c path was explored.

Gender did not significantly moderate the mediational relationship between total racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptom severity (B = −0.71, CI [−3.26, 1.12], S E = 1.11), as seen in .

Table 4. Moderated-mediational analysis for total racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptom severity.

7. Discussion

This current study was a follow-up to previous results showing that experiences of racial discrimination added significant risk to developing acute and chronic PTSD symptoms after a traumatic injury (Bird et al., Citation2021). However, few studies have examined possible underlying mechanisms of this relationship. This study was the first to explore the relationship between racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD, with an emphasis on the mechanistic role of dissociation. The novel findings of this present study show that peritraumatic dissociation significantly mediated the effect of racial discrimination on PTSD symptom severity, even when controlling for age and lifetime trauma exposure. These results suggest that experiences of discrimination increase the risk for peritraumatic dissociation during the index trauma, which in turn increases the risk for future PTSD symptomology. In other words, peritraumatic dissociation is a mechanism through which racial discrimination is linked to PTSD symptom severity. Importantly, these findings were maintained even after controlling for other trauma exposure. This emphasizes the specific effect of racial discrimination and minimizes the misattribution of results to other, lifetime trauma.

7.1. Racial discrimination and peritraumatic dissociation

As it stands, these results demonstrate that Black Americans who experience racial discrimination are at increased risk for dissociating during a traumatic event, and consequently, developing PTSD symptoms. Initially, peritraumatic dissociation may be protective because it helps individuals separate themselves from their painful, life-threatening, and fearful reality (Punamäki et al., Citation2005). However, since important neurobiological, somatic, and affective reactions are disrupted during peritraumatic dissociation, the natural recovery from a traumatic event is disrupted and ultimately increases the risk of PTSD development (Mattos et al., Citation2016; Thompson et al., Citation2017).

Similarly, experiences of racial discrimination create a reality for many Black Americans that involves life-threat and fear and produces posttraumatic stress symptoms as defined by DSM-5 criteria; thus, there has been a call to conceptualize racial discrimination as a chronic traumatic stressor (Abdullah et al., Citation2021; Carter, Citation2007; Carter et al., Citation2021). As the Complex Racial Trauma Theory shows (Cénat et al., Citation2022), Black Americans are faced with frequent experiences of racial discrimination at several levels (e.g. personal and institutional; Williams et al., Citation1999). Thus, racial discrimination may prompt individuals to detach from their environment and engage in avoidance and emotional numbing strategies to manage frequent race-based stress, as many individuals do in the face of other traumatic events (Mekawi et al., Citation2020; Polanco-Roman et al., Citation2016). Moreover, since American systems oftentimes further punish Black Americans when they actively respond to racial injustice, the use of such strategies may also be protecting Black Americans from additional harm or threat (Polanco-Roman et al., Citation2016). Lastly, racial discrimination at an institutional level does not allow Black Americans resources to intervene at an individual level. Thus, the multi-faceted layers of racial trauma emphasize its complex nature (Cénat et al., Citation2022) and may explain why many Black Americans may only be able to rely on such reactions that decrease one’s ability to process stressful events effectively and actively. This may be further compounded when they experience other traumatic events.

In the current study, experiences of racial discrimination increase risk of peritraumatic dissociation during a separate trauma (e.g. a motor vehicle crash). Therefore, it seems that repeated traumatic stress (e.g. racial discrimination) prompts many Black Americans to detach from their reality, and thus be more vulnerable to experiencing the similar, and complex, processes of peritraumatic dissociation (emotional numbing, depersonalization, derealization) in response to other traumas (Lensvelt-Mulders et al., Citation2008; Polanco-Roman et al., Citation2016; Thompson et al., Citation2017). In sum, current results emphasize that racial discrimination is a stressor that increases the risk of peritraumatic dissociation in the face of other traumatic events, and later, PTSD. While this study was not designed to specifically explore how racial discrimination fits as a ‘Criterion A’ traumatic event, it provides evidence that experiences of racial discrimination elicit responses, such as peritraumatic dissociation, that other traumatic events do as well. It also provides evidence for the Complex Racial Trauma theory, showing that the impacts of racial trauma are widespread (Cénat et al., Citation2022).

The secondary aim examined the moderating role of gender in this mediational model. The data used in this current study allowed for the examination of gender differences relating to different types of racial discrimination, since previous research has found that Black men and women’s lived experiences with trauma, PTSD, and discrimination differ (Jones et al., Citation2007; Silverstein et al., Citation2022). In order to examine the role of gender in this mediational model, a moderated mediation was conducted as a secondary aim. However, results did not demonstrate that gender significantly moderated the mediation, suggesting that the indirect effect was upheld for both Black men and women in similar ways. In other words, peritraumatic dissociation seems to function similarly as a mechanism between experiencing discrimination and developing PTSD for Black American men and women. These findings are contrary to previous literature showing that women are more likely to report peritraumatic dissociation (Bryant & Harvey, Citation2003; Irish et al., Citation2011). It may be that, while these gender differences exist among White Americans, they may not necessarily be true for Black Americans.

Overall, these results are significant because they provide an understanding of a mechanism explaining the relationship between racial discrimination and PTSD symptoms in the aftermath of a traumatic event. These findings have an important role in informing prevention and intervention efforts. At a broad level, preventative measures include the need to continue dismantling systems of oppression disproportionately impacting Black Americans and leaving them at an increased risk of dissociation and PTSD. Additional preventative measures may include creating safe, supportive systems at a community level that provide Black Americans resources to actively process experiences of discrimination with other community members. This may help reduce the reliance on avoidance strategies that increase the risk for dissociation during race-based and non-race-based traumatic events (Polanco-Roman et al., Citation2016). Through safe, supportive spaces, individuals can effectively process stressful and traumatic events, and thus, decrease the dependence on strategies that increase the risk for dissociation (Mekawi et al., Citation2020; Mekawi, Carter, Packard et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, these findings can also inform interventions. Interventions for PTSD should consider clients’ lived experiences, as racial discrimination continues to impact the recovery of trauma (Bird et al., Citation2021; Ruef et al., Citation2000). Clinicians should be actively aware of the effect of racial discrimination – which itself is a chronic, traumatic stressor (Cénat et al., Citation2022) – on the healing of a separate, traumatic event, and consider assessing for it when evaluating patients and developing a treatment plan. Therefore, interventions can be tailored to support individuals in the aftermath of a traumatic event as it intersects with the pervasive effects of racial discrimination.

In addition to clinical implications, these findings also offer important considerations for future trauma research. While working to understand trauma, dissociation, and PTSD among Black Americans, researchers should assess for experiences of racial discrimination and their impact. Since findings suggest a clear link between discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation, and PTSD symptoms, researchers should consider assessing for, and including, discrimination as a covariate, or a variable of interest.

The prospective nature of the current study provides impactful findings furthering the body of knowledge regarding trauma and racial discrimination. With this design, it was possible to examine how experiences of racial discrimination prior to the traumatic injury increased the risk for peritraumatic dissociation during the injury, and the subsequent effect on PTSD symptoms several months later. Moreover, these findings were significant even when covarying for lifetime trauma exposure. This isolates the effect of racial discrimination as a traumatic stressor and emphasizes its impact on PTSD symptomatology, via peritraumatic dissociation. A final strength of the study is that it assessed peritraumatic dissociation soon after the traumatic event, minimizing the risk of recall bias.

While important, this study is not without its limitations. Limitations include a limited variability in mechanism of injury and geographic location, focus on Black Americans, small sample size, and the lack of assessment of trauma experienced between time points. Thus, the generalizability of results is limited.

Future studies should explore the neurobiological underpinnings of racial discrimination, peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD to explore the biology behind the mechanistic role of dissociation. Research should also continue this line of work with other minoritized individuals to capture the widespread effect of racial discrimination and recognize the role of systemic injustice. Moreover, studies should continue to implement an intersectional lens while exploring complex lived experiences to avoid diluting individuals to one, single, salient identity and ignoring the way that systems of oppression interact to further subordinate individuals.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the NIMH NDA data repository, https://nda.nih.gov. Data can be made available upon request from the author.

References

- Abdullah, T., Graham-LoPresti, J. R., Tahirkheli, N. N., Hughley, S. M., & Watson, L. T. J. (2021). Microaggressions and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom scores among Black Americans: Exploring the link. Traumatology, 27(3), 244–253. doi:10.1037/trm0000259

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Ayawvi, G., Sanders, A., Raven, B., Powers, A., & Carter, S. (2022). The Iinfluence of racial discrimination and childhood sexual abuse on dissociative symptoms among Black Americans. International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies.

- Aymer, S. R. (2010). Clinical practice with African American men: What to consider and what to do. Smith College Studies in Social Work (Taylor & Francis Ltd), 80(1), 20–34. doi:10.1080/00377310903504908

- Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Stein, D. J., Petukhova, M., Hill, E., Alonso, J., Atwoli, L., Bunting, B., Bruffaerts, R., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., de Girolamo, G., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Huang, Y., Lepine, J. P., … Koenen, K. C. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001981

- Bird, C. M., Webb, E. K., Schramm, A. T., Torres, L., Larson, C., & deRoon, C. T. A. (2021). Racial discrimination is associated with acute posttraumatic stress symptoms and predicts future posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity in trauma-exposed Black adults in the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(5), 995–1004. ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/10.1002/jts.22670

- Breh, D. C., & Seidler, G. H. (2007). Is peritraumatic dissociation a risk factor for PTSD? Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 8(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v08n01_04

- Breslau, N., Davis, G. C., Andreski, P., Peterson, E. L., & Schultz, L. R. (1997). Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(11), 1044–1048. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230082012

- Brondolo, E., Kelly, K. P., Coakley, V., Gordon, T., Thompson, S., Levy, E., Cassells, A., Tobin, J. N., Sweeney, M., & Contrada, R. J. (2005). The Perceived Ethnic Discrimination Questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation of a community version. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(2), 335–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2005.tb02124.x

- Bryant, R. A., & Harvey, A. G. (2003). Gender differences in the relationship between acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder following motor vehicle accidents. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37(2), 226–229. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01130.x

- Cardeña, E., Marcusson-Clavertz, D., & Cervin, M. (2022). The relation between peritraumatic dissociation and coping strategies: A network analysis. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, Advanced online publication https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.uwm.edu/10.1037/tra0001403

- Carter, R. T. (2007). Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(1), 13–105. doi:10.1177/0011000006292033

- Carter, R. T., Johnson, V. E., Muchow, C., Lyons, J., Forquer, E., & Galgay, C. (2016). Development of classes of racism measures for frequency and stress reactions: Relationships to race-based traumatic symptoms. Traumatology, 22(1), 63–74. doi:10.1037/trm0000057

- Carter, R. T., Kirkinis, K., & Johnson, V. E. (2020). Relationships between trauma symptoms and race-based traumatic stress. Traumatology, 26(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000217

- Carter, R. T., Lau, M. Y., Johnson, V. E., & Kirkinis, K. (2017). Racial discrimination and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 45(4), 232–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmcd.12076

- Carter, S. E., Gibbons, F. X., & Beach, S. (2021). Measuring the biological embedding of racial trauma among black Americans utilizing the RDoC approach. Development and Psychopathology, 33(5), 1849–1863. doi:10.1017/S0954579421001073

- Cavicchioli, M., Scalabrini, A., Northoff, G., Mucci, C., Ogliari, A., & Maffei, C. (2021). Dissociation and emotion regulation strategies: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 143, 370–387. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.011

- Cénat, J. M., Dalexis, R. D., Darius, W. P., Kogan, C. S., & Guerrier, M. (2022). Prevalence of current PTSD symptoms among a sample of Black individuals aged 15 to 40 in Canada: The major role of everyday discrimination, racial microaggressions, and internalized racism. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 68(3), 178–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437221128462

- Collins, P. H. (1991). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167. Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8.

- Dale, S. K., & Safren, S. A. (2019). Gendered racial microaggressions predict posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and cognitions among Black women living with HIV. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11(7), 685. doi:10.1037/tra0000467

- Gray, M. J., Litz, B. T., Hsu, J. L., & Lombardo, T. W. (2004). Psychometric properties of the Life Events Checklist. Assessment, 11(4), 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191104269954

- Hawkins, D. S. (2022). “After Philando, I had to take a sick day to recover”: Psychological distress, trauma and police brutality in the Black community. Health Communication, 37(9), 1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1913838

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F., & Rockwood, N. J. (2017). Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 98, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.11.001

- Hirsch, C. E., & Cha, Y. (2008). Understanding employment discrimination: A multilevel approach. Sociology Compass, 2(6), 1989–2007. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2008.00157.x

- Holmes, S. C., Facemire, V. C., & DaFonseca, A. M. (2016). Expanding Criterion A for posttraumatic stress disorder: Considering the deleterious impact of oppression. Traumatology, 22(4), 314–321. doi:10.1037/trm0000104

- Irish, L. A., Fischer, B., Fallon, W., Spoonster, E., Sledjeski, E. M., & Delahanty, D. L. (2011). Gender differences in PTSD symptoms: An exploration of peritraumatic mechanisms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(2), 209–216. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.09.004

- Jones, A. C., Badour, C. L., Brake, C. A., Hood, C. O., & Feldner, M. T. (2018). Facets of emotion regulation and posttraumatic stress: An indirect effect via peritraumatic dissociation. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 42(4), 497–509. doi:10.1007/s10608-018-9899-4

- Jones, H. L., Cross, W. E., Jr, & DeFour, D. C. (2007). Race-related stress, racial identity attitudes, and mental health among Black women. Journal of Black Psychology, 33(2), 208–231. doi:10.1177/0095798407299517

- Jones, J. M. (1997). Prejudice and racism. McGraw-Hill.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., Degenhardt, L., de Girolamo, G., Dinolova, R. V., Ferry, F., Florescu, S., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., Huang, Y., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Lepine, J. P., Levinson, D., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(5), 1353383. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1353383

- Kilpatrick, D. G., Resnick, H. S., Milanak, M. E., Miller, M. W., Keyes, K. M., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21848

- Koopman, C., Classen, C., & Spiegel, D. A. (1994). Predictors of posttraumatic stress symptoms among survivors of the Oakland/Berkeley, California firestorm. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(6), 888–894. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.6.888

- Lawyer, S. R., Resnick, H. S., Galea, S., Ahern, J., Kilpatrick, D. G., & Vlahov, D. (2006). Predictors of peritraumatic reactions and PTSD following the September 11th terrorist attacks. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 69(2), 130–141. doi:10.1521/psyc.2006.69.2.130

- Lee, R. T., Perez, A. D., Boykin, C. M., & Mendoza-Denton, R. (2019). On the prevalence of racial discrimination in the United States. PLOS ONE, 14(1), e0210698. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210698

- Lensvelt-Mulders, G., van der Hart, O., van Ochten, J. M., van Son, M. J. M., Steele, K., & Breeman, L. (2008). Relations among peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(7), 1138–1151. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.03.006

- Lewis, J. A., & Neville, H. A. (2015). Construction and initial validation of the gendered racial microaggressions scale for black women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000062

- Lilly, M. M., & Valdez, C. E. (2012). Interpersonal trauma and PTSD: The roles of gender and a lifespan perspective in predicting risk. Psychological Trauma-Theory Research Practice and Policy, 4(1), 140–144. doi:10.1037/a0022947

- Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D. S., & Metzler, T. J. (1997). The Peritraumatic Dissociative Experiences Questionnaire. In J. P. Wilson, & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD (pp. 412–428). The Guilford Press.

- Marmar, C. R., Weiss, D. S., Schlenger, W. E., Fairbank, J. A., Jordan, B. K., Kulka, R. A., & Hough, R. L. (1994). Peritraumatic dissociation and posttraumatic stress in male Vietnam theater veterans. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 151(6), 902–907. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.6.902

- Mattos, P. F., Pedrini, J. A., Fiks, J. P., & de Mello, M. F. (2016). The concept of peritraumatic dissociation: A qualitative approach. Qualitative Health Research, 26(7), 1005–1014. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315610521

- Mekawi, Y., Carter, S., Brown, B., Martinez de Andino, A., Fani, N., Michopoulos, V., & Powers, A. (2021). Interpersonal trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among Black Women: Does racial discrimination matter? Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 22(2), 154–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2020.1869098

- Mekawi, Y., Carter, S., Packard, G., Wallace, S., Michopoulos, V., & Powers, A. (2021). When (passive) acceptance hurts: Race-based coping moderates the association between racial discrimination and mental health outcomes among Black Americans. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001077

- Mekawi, Y., Watson-Singleton, N. N., Kuzyk, E., Dixon, H. D., Carter, S., Bradley-Davino, B., Fani, N., Michopoulos, V., & Powers, A. (2020). Racial discrimination and posttraumatic stress: Examining emotion dysregulation as a mediator in an African American community sample. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), state Article 1824398. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1824398

- Nobakht, H. N., Ojagh, F. S., & Dale, K. Y. (2019). Risk factors of post-traumatic stress among survivors of the 2017 Iran earthquake: The importance of peritraumatic dissociation. Psychiatry Research, 271, 702–707. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.057

- Otis, C., Marchand, A., & Courtois, F. (2012). Peritraumatic dissociation as a mediator of peritraumatic distress and PTSD: A retrospective, cross-sectional study. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13(4), 469–477. doi:10.1080/15299732.2012.670870

- Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. L., & Weiss, D. S. (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52

- Pager, D., & Shepherd, H. (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740

- Pieterse, A. L., Carter, R. T., Evans, S. A., & Walter, R. A. (2010). An exploratory examination of the associations among racial and ethnic discrimination, racial climate, and trauma-related symptoms in a college student population. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(3), 255–263. doi:10.1037/a0020040

- Polanco-Roman, L., Danies, A., & Anglin, D. M. (2016). Racial discrimination as race-based trauma, coping strategies, and dissociative symptoms among emerging adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(5), 609–617. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000125

- Punamäki, R.-L., Komproe, I. H., Qouta, S., Elmasri, M., & de Jong, J. V. M. (2005). The role of peritraumatic dissociation and gender in the association between trauma and mental health in a Palestinian community sample. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(3), 545–551. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.545

- Roberts, A. L., Gilman, S. E., Breslau, J., Breslau, N., & Koenen, K. C. (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological Medicine, 41(1), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000401

- Rothbaum, B. O., Kearns, M. C., Price, M., Malcoun, E., Davis, M., Ressler, K. J., Lang, D., & Houry, D. (2012). Early intervention may prevent the development of PTSD: A randomized pilot civilian study with modified prolonged exposure. Biological Psychiatry, 72(11), 957–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.06.002

- Ruef, A. M., Litz, B. T., & Schlenger, W. E. (2000). Hispanic ethnicity and risk for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6(3), 235–251. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.6.3.235

- Shorter-Gooden, K. (2004). Multiple resistance strategies: How African American women cope with racism and sexism. Journal of Black Psychology, 30(3), 406–425. doi:10.1177/0095798404266050

- Sibrava, N. J., Bjornsson, A. S., Pérez Benítez, A. C. I., Moitra, E., Weisberg, R. B., & Keller, M. B. (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder in African American and Latinx adults: Clinical course and the role of racial and ethnic discrimination. American Psychologist, 74(1), 101–116. doi:10.1037/amp0000339

- Silverstein, M. W., Mekawi, Y., Watson-Singleton, N. N., Shebuski, K., McCullough, M., Powers, A., & Michopoulos, V. (2022). Psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 10 in a community sample of African American adults: Exploring the role of gender. Traumatology, 28(2), 211–222. doi:10.1037/trm0000316

- Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. J. (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 31–53. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00200

- Thompson, H. J., Jun, J. J., & Sloan, D. M. (2017). The association between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptoms: The mediating role of negative beliefs about the self. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(2), 190–194. doi:10.1002/jts.22179

- Tolin, D. F., & Foa, E. B. (2006). Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 132(6), 959–992. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959

- Torres, L., Driscoll, M. W., & Burrow, A. L. (2010). Racial microaggressions and psychological functioning among highly achieving African Americans: A mixed-methods approach. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29(10), 1074–1099. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2010.29.10.1074

- Ursano, R. J., Fullerton, C. S., Epstein, R. S., Crowley, B., Kao, T. C., Vance, K., Craig, K. J., Dougall, A. L., & Baum, A. (1999). Acute and chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in motor vehicle accident victims. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(4), 589–595. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.4.589

- Valentine, S. E., Marques, L., Wang, Y., Ahles, E. M., Dixon De Silva, L., & Alegría, M. (2019). Gender differences in exposure to potentially traumatic events and diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by racial and ethnic group. General Hospital Psychiatry, 61, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.10.008

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) [Assessment]. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/ adult-int/caps.asp.

- Weathers, F. W., Bovin, M. J., Lee, D. J., Sloan, D. M., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Keane, T. M., & Marx, B. P. (2018). The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment, 30(3), 383–395. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000486

- Webb, E. K., Bird, C. M., deRoon-Cassini, T. A., Weis, C. N., Huggins, A. A., Fitzgerald, J. M., Miskovich, T., Bennett, K., Krukowski, J., Torres, L., & Larson, C. L. (2022). Racial discrimination and resting-state functional connectivity of salience network nodes in trauma-exposed Black adults in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 5(1), e2144759. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.44759

- Weis, C. N., Webb, E. K., Stevens, S. K., Larson, C. L., & deRoon-Cassini, T. A. (2022). Scoring the Life Events Checklist: Comparison of three scoring methods. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 14(4), 714–720. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001049

- Williams, D. R., Spencer, M. S., & Jackson, J. S. (1999). Race, stress, and physical health: The role of group identity. In R. J. Contrada, & R. D. Ash-more (Eds.), Self, Social Identity, and Physical Health: Interdisciplinary Explorations (pp. 71–100). Oxford University Press.

- World Health Organization. (2018). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). World Health Organization.