ABSTRACT

Background: The death of a child is a highly traumatic event for parents and often leads to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Attentional bias has been demonstrated in the onset and maintenance of PTSD symptoms.

Objective: This study aimed to investigate the time course of attentional bias among bereaved Chinese parents who have lost their only child (Shidu parents), and to examine its relationship with PTSD symptoms and symptom clusters.

Methods: Shidu parents (n = 38; 50–72 years of age) completed a dot-probe task with negative (trauma-related), positive, and neutral images at four stimulus presentation times (250, 500, 750, and 1250 ms). PTSD symptoms were measured by the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

Results: We observed difficulty in disengaging from both negative and positive stimuli at 750 ms and attentional bias away from negative stimuli at 1250 ms. At 1250 ms, attentional avoidance of trauma-related stimuli was positively correlated with PCL-5 total and intrusion scores. Difficulty in disengaging from positive stimuli was negatively correlated with PCL-5 total and intrusion scores as well as negative alterations in cogniti and mood scores.

Conclusions: These findings enhance our understanding of attentional bias and cognitive–affective processing in PTSD. This study provides evidence that attentional bias (difficulty in disengaging from positive stimuli and bias away from negative stimuli) are correlated with PTSD symptoms and certain symptom clusters.

HIGHLIGHTS

The current study examined the time course of attentional bias among bereaved Chinese parents who have lost their only child through a dot-probe task and investigated its relationship with PTSD symptoms and symptom clusters.

Participants exhibited difficulty in disengaging from both trauma-related and positive stimuli at 750 ms and exhibited attentional avoidance of trauma-related stimuli at 1250 ms.

Attentional avoidance of trauma-related stimuli was positively correlated with PCL-5 total and intrusion scores. Difficulty in disengaging from positive stimuli was negatively correlated with PCL-5 total and intrusion scores as well as negative alterations in cognition and mood scores.

Antecedentes: La muerte de un hijo es un evento altamente traumático para padres y a menudo lleva a trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT). El sesgo atencional se ha demostrado en el comienzo y en la mantención de los síntomas del TEPT.

Objetivo: Este estudio buscó investigar el curso del tiempo del sesgo atencional entre los padres chinos en duelo que han perdido a su único hijo (padres Shidu), y examinar su relación con los síntomas de TEPT y los grupos sintomáticos.

Método: Padres Shidu (n = 38, 50–72 años de edad) completaron una prueba de dot-probe con imágenes negativas (relacionadas al trauma), positivas, y neutrales en cuatro momentos de presentación del estímulo (250, 500, 750, y 1250 ms). Los síntomas del TEPT se midieron por medio de la Lista de Chequeo del TEPT para el DSM-5 (PCL-5 en su sigla en inglés).

Resultados: Observamos dificultades en desvincularse de los estímulos negativos y positivos desde los 750 ms y desaparición del sesgo atencional desde el estímulo a 1250 ms. A los 1250 ms, la evitación atencional del estímulo negativo se correlacionó positivamente con los puntajes totales de la PCL-5 y puntajes de intrusión. Las dificultades en desvincularse desde el estímulo positivo se asociaron negativamente con los puntajes totales de la PCL-5 y los puntajes de intrusión como también con la puntuación de alteraciones negativas de cognición y ánimo.

Conclusiones: Estos hallazgos mejoran nuestro entendimiento del sesgo atencional y procesamiento cognitivo-afectivo en el TEPT. Este estudio provee evidencia que el sesgo atencional (dificultades en desvincularse desde un estímulo positivo y sesgo distanciándose desde el estímulo negativo) se correlacionan con los síntomas de TEPT y algunos grupos de síntomas.

背景:子女的死亡对父母来说是最严重的创伤事件,往往导致创伤后应激障碍(PTSD)。对情绪刺激的注意偏向被认为是PTSD患者典型的认知特点,也是引发和维持PTSD的重要认知因素。

目的:本文旨在探讨失独父母注意偏向的时程特征,并探索其与PTSD症状之间的关系。

方法:以38名失独父母(50–72岁)为研究对象,以负性(创伤相关)、正性和中性图片为实验刺激材料,让被试在四种刺激呈现时间(250、500、750和1250 ms)下完成点探测任务来测量注意偏向。采用创伤后应激障碍检查表第5版(PCL-5)测量PTSD症状。

结果:当图片呈现时间为750 ms时,被试对负性和正性图片存在注意解除困难;当图片呈现时间为1250 ms时,被试只对负性图片存在注意回避;当图片呈现时间为1250 ms时,对负性图片的注意回避与PTSD总分和闯入维度的分数之间存在正向关联,对正性图片的注意解除困难与PTSD总分、闯入和认知和情绪负性改变维度的分数之间存在负向关联。

结论:本研究扩展了在创伤领域中我们对注意偏向模式以及认知和情感过程关系的理解,并提供了注意偏向(注意解除困难和注意回避)与PTSD症状相关的证据。

1. Introduction

The death of a loved one (e.g. a parent, spouse, sibling, or child) is inevitably tragic. Research has found that losing a child resulted in more severe traumatic outcomes in parents compared with the death of other loved ones, possibly due to the stronger attachment between parents and children (Kristensen et al., Citation2012). In China, there is a remarkable number of parents who have lost their only child, an unintentional consequence of the ‘one-child policy’; such parents are called Shidu parents (Chen, Citation2013). Specifically, Shidu parents are bereaved parents who have passed their reproductive windows and cannot conceive another child (i.e. mothers over 49 years of age) and are unwilling to adopt another child (Chen, Citation2013). In Chinese culture, children represent generational continuity and play an important economic and social support role for aging parents (Wei et al., Citation2016). Losing their only child thus represents the termination of family lines and the loss of caregivers in old age. Moreover, Chinese culture regards the death of a child as a sign of bad luck (Zheng & Lawson, Citation2015), resulting in the stigmatization of Shidu parents. Therefore, these Shidu parents experience psychological trauma and cultural pressure that induce major mental health problems, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Eli et al., Citation2020; Citation2021; Wang & Xu, Citation2016).

PTSD is a debilitating mental condition that develops after exposure to a traumatic event, including the loss of a loved one due to a violent or unnatural cause (e.g. homicide, suicide, or accident), natural or man-made disasters, or experience of interpersonal violence as presented in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). The prevalence of PTSD may differ substantially by type of traumatic event (Blanco, Citation2011; Lukaschek et al., Citation2013), and the death of a loved one is strongly linked to the risk of PTSD (Blanco, Citation2011). Shidu parents may also have a higher risk of PTSD than other bereaved individuals. The international lifetime prevalence of PTSD is 5.6% (Koenen et al., Citation2017). The prevalence of PTSD among individuals with a late-life spousal bereavement is 16% (O’Connor, Citation2010). Studies found that the estimated rates of PTSD among bereaved survivors who lost first-degree family members and second-degree relatives after an earthquake were 65.6% and 34.1%, respectively (Chan et al., Citation2012). After the same earthquake, the probable PTSD prevalence in Shidu parents was as high as 83.5% (Wang & Xu, Citation2016). Furthermore, previous studies have found that more than 50% of parents reported PTSD symptoms after losing their only child (Eli, Citation2019; Eli et al., Citation2021; Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2019). Shidu parents, with their high prevalence of PTSD, have become a major focus in clinical research and psychological intervention. In addition, Shidu parents are more likely to be triggered by cues related to their child's death or to have maladaptive cognitive responses to these cues. Studies have indicated that Shidu parents undergo cognitive changes after their loss, including intrusive thoughts, avoidance of cues related to their child's death, and attentional problems (Eli, Citation2019). However, the cognitive risk factors for PTSD onset among Shidu parents remain unclear.

One factor to consider is maladaptive attentional patterns, such as attentional bias, in individuals exposed to trauma. Attentional bias is defined as the tendency to allocate attentional resources to emotional stimuli (Mogg & Bradley, Citation1998; Weber, Citation2008) and is considered a potential cognitive risk factor for PTSD symptom onset, maintenance, and remission (Sipos et al., Citation2014; Yuval et al., Citation2017). Most studies have used a dot-probe task (Mogg & Bradley, Citation1999) to measure attentional bias and have shown positive correlations between bias toward threats and PTSD symptoms (DePierro et al., Citation2013; N. Fani et al., Citation2012a; Herzoga et al., Citation2019), bias away from threats and PTSD symptoms (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2010; Sipos et al., Citation2014; Wald et al., Citation2011), or difficulty in disengaging from threats and PTSD symptoms (Bardeen & Orcutt, Citation2011). While these studies have advanced our knowledge of the field, they have yielded inconclusive results regarding PTSD symptoms, and some important questions remain unanswered.

First, previous studies have focused on PTSD symptoms as a whole, without distinguishing between symptom clusters (e.g. intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity) and their respective associations with attentional bias patterns. PTSD is a heterogeneous disorder, and certain types of symptoms may be more positively correlated with attentional bias. For instance, symptom network studies of PTSD have shown that intrusion and avoidance symptoms are associated with PTSD onset following combat exposure (Segal et al., Citation2020) and that intrusion symptoms and alterations in arousal and reactivity are associated with maintenance of PTSD symptoms after the loss of one's only child (Eli et al., Citation2021). In addition, attentional bias is likely to be a temporally dynamic process, expressed in fluctuating, phasic bursts toward or away from motivationally relevant stimuli over time (Zvielli et al., Citation2016). The cognitive model of anxiety disorders suggests that anxious individuals tend to automatically orient attention toward threats, followed by attentional avoidance at longer stimulus exposure durations to alleviate their anxiety (Mogg & Bradley, Citation1998). Attentional bias toward threats promotes the reappearance of traumatic memories, which underlies the re-experiencing and hypervigilance symptoms of PTSD (Hayes et al., Citation2012). Attentional avoidance as a coping strategy appears after enhanced detection of threats (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2007). A study found that attentional bias toward traumatic cues positively correlated with behavioural avoidance of traumatic cues (Yuval et al., Citation2017). Another study found a positive correlation between experiential avoidance (to control or avoid unpleasant thoughts, feelings and bodily sensations) and negative affect (Machell et al., Citation2015). Therefore, exploring the specific relationship between attentional bias components and PTSD symptom clusters may help to identify the risk factors for different symptom clusters and the potential causes of PTSD symptoms.

The different components of attentional bias might operate at different information processing stages. For example, facilitated attention to threats occurs at the automatic processing stage with brief stimulus exposure, whereas delayed disengagement from threats and attentional avoidance of threats occur at late strategic stages with prolonged stimulus exposure (Cisler & Koster, Citation2010). Fox and colleagues indicated that models of selective attention vary within individuals according to the different stages of information processing, namely orientation (less than 30 ms), engagement (30–500 ms), disengagement (500–1000 ms), and avoidance (Fox et al., Citation2001). To our knowledge, only one study investigated the relationship between total PTSD symptoms and attentional bias at rapid (250 ms), short (500 ms), and long (2000 ms) exposures; they found a positive relationship between total PTSD symptoms and bias toward threats in the 2000-ms exposure (Herzoga et al., Citation2019). However, the relationship between attentional bias components at different stimulus exposure durations and PTSD symptom clusters remains unclear.

In addition, selection of experimental materials (trauma-related or trauma-unrelated) may be important for assessing attentional bias in PTSD. Evidence indicates that attentional bias to threatening stimuli is influenced by individuals’ traumatic experiences (Yuval et al., Citation2017; Zinchenko et al., Citation2017). Compared to trauma-unrelated cues, the corresponding trauma-related cues provoke stronger arousal responses and attract more attention in individuals with PTSD (Pergamin-Hight et al., Citation2015; Yuval et al., Citation2017). Several studies have also found content specificity of trauma-related bias among individuals with PTSD symptoms (Ashley et al., Citation2013; Zinchenko et al., Citation2017). Moreover, image stimuli are of greater ecological value and emotional salience than word stimuli (McBride & Dosher, Citation2002). Therefore, selecting effective tailored stimuli (e.g. trauma-related images) for participants with PTSD symptoms is crucial for detecting precise attentional bias. However, few studies on the relationship between attention bias and PTSD symptoms have used trauma-related stimuli.

Finally, few PTSD studies have focused on the attentional bias patterns of bereaved parents, especially Shidu parents; most PTSD studies on attentional bias have been conducted with soldiers/veterans (Olatunji et al., Citation2022; Sipos et al., Citation2014), victims of interpersonal violence (DePierro et al., Citation2013; Hirai et al., Citation2022; Klanecky Earl et al., Citation2020), or other traumatized groups. Although previous studies have provided novel insights in this field, repeatability of these results in Shidu parents may be limited because of differences in the types of trauma and cultural backgrounds. Thus, exploring the attentional bias patterns and their association with PTSD symptom clusters in this unique population is particularly important.

The present study had two main objectives: (1) to explore the time course of attentional bias among Shidu parents through a dot-probe task using negative (trauma-related), positive, and neutral images as stimuli; and (2) to examine the relationship of attentional bias components with PTSD symptom clusters. According to the suggestions and cognitive model of Fox and colleagues (Citation2001), we selected four stimulus exposure duration: 250, 500, 750, and 1250 ms. We hypothesized that participants would show attentional bias toward emotional stimuli at rapid exposures (250 ms), difficulty in disengaging from emotional stimuli at short and moderate exposures (500 and 750 ms), and attentional bias away from emotional stimuli at long exposures (1250 ms). We also hypothesized that attentional bias toward emotional stimuli is correlated with symptoms of intrusion and alterations in arousal and reactivity; difficulty in disengaging from stimuli is correlated with symptoms of intrusion and negative alterations in cognition and mood; and attentional avoidance is correlated with symptoms of avoidance and negative alterations in cognition and mood.

2. Methods

2.1 Procedure and participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted from November to December 2021 in Huai’an, Jiangsu Province, China. Participants were recruited by local community workers who underwent standardized and strict training to supervise the investigation. Eligible participants were bereaved parents who had lost their only child at least one year earlier and had no living child, were between 50 and 75 years old, were right-handed with normal or corrected visual acuity, and had no history of neurological or mental illness that could potentially affect the results of the experiment. Participants who satisfied the inclusion criteria were invited to the community office to answer the questionnaire and complete the dot-probe task.

The study protocol was approved by the ethics review committee of the Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; all the research procedures met ethical standards. Before individuals participated, the aims of the study were described, anonymity and confidentiality in the reporting of results was emphasized, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time was clearly conveyed. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, and all participants completed the experiment voluntarily. Participants then completed the questionnaires and comfortably seated themselves at a 70-cm viewing distance from the computer to perform the dot-probe task on a standard set of identical laptop computers. Participants were provided with standardized instructions before completing the dot-probe task; specifically, participants were told that the background images were irrelevant to the task, instructed to maintain central fixation and respond to the targets (indicate whether the letter ‘E’ opened to the left or right) as quickly and accurately as possible, and allowed to complete 16 practice trials (all stimuli consisting of neutral image pairings). After finishing all the tests, each participant was compensated with 100 RMB for participation. Professional psychological services were available for the participants if they felt mental discomfort and emotional anguish during or after the study.

A total of 40 Shidu participants aged 50–72 years participated in our study; data from two (5%) of these participants were excluded from analyses due to invalid data. The final sample consisted of 38 (95%) participants with a mean age of 61.0 ± 5.0 years. Of these participants, 45% were men and 55% were women. Regarding educational attainment, 28.9% never went to school, 36.8% attended junior high school or below, and 34.2% attended high school or above. Regarding marital status, 94.7% were married and 5.2% were divorced or widowed. The monthly income of most participants (81.6%) was less than 2,000 RMB. Regarding cause of death, 60.5% of participants had lost their only child due to accident, homicide, or suicide, and 39.5% of participants had lost their only child due to illness. Regarding the sex of the child, 60.5% had lost their son, 26.3% had lost their daughter, and 13.2% of participants had missing information for this variable. The age of the children at death ranged from 11 to 42 years (M = 27.6 years; SD = 8.4). The loss had occurred an average of 9.3 years (SD = 5.3; range: 1–20 years) prior to data collection.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 PTSD symptoms

The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) was used to assess PTSD symptoms over the past month (Weathers et al., Citation2013). The self-report PCL-5 contains 20 items from four subscales that correspond to the four DSM-5 PTSD symptom clusters: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity (AmericanPsychiatricAssociation, Citation2013). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = Not at all to 4 = Extremely. The total score ranges from 0 to 80, with higher scores representing more severe PTSD symptoms. A cut-off for the total score equal to 33 or greater was considered to indicate PTSD (Weathers et al., Citation2013). In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for this measure was 0.84.

2.2.2 Attentional bias

Attentional bias was measured by the dot-probe task. Tasks were presented in Eprime 2.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh).

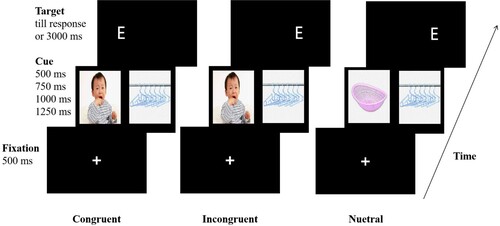

Dot-probe task. In the dot-probe task (), each trial began with the presentation of a white fixation cross for 500 ms at the centre of a black screen; subsequently a pair of images were presented on either side of the fixation cross for one of four stimulus presentation durations (250, 500, 750, or 1250 ms); in each pair, a negative, positive, or neutral image was randomly paired with a neutral image. Immediately following the offset of the image pair, a probe took the place of one of the images; the probe remained present until the participants pressed a button or 3000 ms later; the next trial started after 1000 ms.

Each participant performed a total of 192 trials over four blocks according to the cue duration (250, 500, 750, and 1250 ms). Each block consisted of 48 trials (16 negative (trauma-related)-neutral (T-N), 16 positive-neutral (P-N), and 16 neutral-neutral (N-N) image pairs) and all trials appeared in random order. Each block presented the same images, but the images were randomly distributed across task trials, and an image appeared only once in each block. Participants were presented with an equal number of trials in each block counterbalanced according to image pair, image emotional valence, image location, probe type, and probe location across participants such that each image appeared in either location with equal probability.

Three conditions, namely ‘congruent’, ‘incongruent’, and ‘neutral’, were tested. In congruent trials, the probe appeared on the same side as the emotional (negative or positive) images. In incongruent trials, the probe appeared on the same side as the neutral images. For the emotional image pairs, half were congruent and the other half were incongruent. In neutral trials, two neutral images were displayed, and the probe randomly occurred on one side.

Stimuli. Pictorial stimuli were used in this study because pictorial stimuli possess higher ecological value and emotional salience than word stimuli (McBride & Dosher, Citation2002), and word stimuli require greater semantic processing (Pineles et al., Citation2009). Stimuli were selected from the Shidu event stimulus set described in a pilot study. The pilot study consisted of two steps: first, 19 Shidu parents (50–70 years) were recruited to determine what kind of scenes or pictures were traumatic or positive for this bereaved group. Thus, participants were asked two questions: (1) what kind of scenes or images make you feel threatened or uncomfortable (e.g. experiencing fear or tension)? (2) What kind of scenes or images make you feel comfortable and joyful? Participants were required to provide at least three different answers to each question. Then, four postgraduate students compiled relevant images according to the scenes or images mentioned by the participants. Additionally, neutral images (valence scores of 4–6, arousal scores < 4.5; e.g. images of furniture) were selected from the Chinese Affective Picture System (CAPS). Finally, a total of 300 images were selected and set to the same size (533 × 400 pixels). Second, another set of 23 Shidu parents (50–70 years) were asked to assess the emotional valence and arousal of the selected 300 images on a 9-point scale (ranging from 1 to 9). According to the results for all images, 68 images were labelled negative emotional images (valence score ≤ 3, arousal score > 4.5), 62 images were labelled positive emotional images (valence score ≥ 7, arousal score > 4.5), and 129 images were labelled neutral emotional images (valence score of 4–6, arousal score < 4.5). Emotional valence and arousal of images were assessed in a pilot study (further details on the pilot study are presented in the Supplementary Materials).

In the present study, 16 negative (trauma-related; e.g. of accidents, illness, or crying children), 16 positive (e.g. of natural scenery such as mountains and rivers, scenes of people dancing, singing and interacting with relatives), and 72 neutral (e.g. of furniture) images were randomly selected from the Shidu event stimulus set. Participants rated the emotional valence and arousal of all the images that appeared in the experiment after completing all dot-probe tasks. The mean valence ratings of negative, positive, and neutral images were 2.56 (SD = 0.21), 7.33 (SD = 0.20), and 6.04 (SD = 0.55), respectively, and the mean arousal ratings of negative, positive, and neutral images were 6.23 (SD = 0.83), 5.24 (SD = 0.70), and 3.48 (SD = 0.59), respectively.

2.3 Statistical analyses

Trials with reaction times (RTs) less than 300 ms or more than 2000 ms were excluded from the analysis. To assess attentional bias effects, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse the RT data collected from the dot-probe task. Probe congruency (congruent, incongruent) and emotion (T-N, P-N, N-N) served as the within-subject factors. In addition, one-sample t tests were conducted for the attentional bias index. The attentional bias index was calculated as the difference between the average RT to targets in emotional and neutral image locations. Vigilance was calculated as RTneutral−RTcongruent; a positive value indicated attentional bias toward emotional stimuli, whereas a negative value indicated attentional bias away from emotional stimuli. Disengagement was calculated as RTincongruent−RTneutral; a positive value indicated difficulties in disengaging (Salemink et al., Citation2007). Second, correlation analyses were used to examine the relation between the attentional bias indices (vigilance and disengagement) in each block and PCL-5 total scores as well as scores on four subscales (symptom clusters: intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity). Third, regression analyses were employed to investigate the association between PTSD symptoms and attentional bias, with the attentional bias indices as the independent variables, PCL-5 total and subscale scores as the dependent variables, and demographic information (e.g. sex, age, marital status, educational attainment, monthly family income, cause of child's death, sex and age of child, and time since child's death) as covariates. The statistical analyses above were conducted with SPSS (IBM SPSS, version 21.0). All tests were two-sided. A p value less than .05 was considered statistically significant, and .05 ≤ p < .1 was considered marginally significant (Pagano, Citation2002).

3. Results

3.1 Descriptive analyses

According to the cut-off score of 33, the prevalence rate of PTSD in the sample was 76.3%. The mean and standard deviation of the PCL-5 total score was 39.36 ± 9.15. The mean and standard deviation of four subscale scores (intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity) for all participants were 11.66 ± 3.52, 4.55 ± 1.89, 12.21 ± 3.15, and 10.95 ± 2.96, respectively. Mean RTs and standard deviations related to performance on each condition are shown in .

Table 1. Mean RTs and standard deviations related to performance on each condition (ms).

3.2 Attentional bias

The results of repeated-measures ANOVAs and one-sample t tests for vigilance and disengagement indices (see ) at four presentation times were as follows.

Table 2. One sample t-test for vigilance and disengagement index in each condition.

At both 250 and 500 ms, no significant main effect of RT or interaction effect of probe congruency and emotion were observed. A one-sample t test revealed no significant difference in vigilance or disengagement for T-N and P-N trials.

At 750 ms, there was a significant main effect of probe congruency (F(1,37) = 7.75, p < .01, η2 = 0.173); specifically, RTcongruent was significantly longer than RTincongruent (mean difference = 22.39, p < .01). Neither a significant main effect of emotion nor an interaction effect was found. A one-sample t test revealed a significant positive value of disengagement from T-N and P-N trials (T-N: t = 1.93, p < .05; P-N: t = 2.39, p < 0.05); no significant difference in vigilance on T-N and P-N trials was revealed.

At 1250 ms, there was a significant main effect of probe congruency (F(1,37) = 4.29, p < .05, η2 = 0.104); specifically, RTcongruent was significantly shorter than RTincongruent (mean difference = −13.36, p < .05). No significant main effect of emotion was revealed, and the interaction effect (F(2, 74) = 2.48, p = .09, η2 = 0.063) was marginally significant. Further simple effect analysis showed that on P-N trials, RTcongruent was significantly shorter than RTincongruent (mean difference = −37.29, p < .05). A one-sample t test revealed that vigilance on T-N trials (t = −1.76, p = .08) was marginally significant, with negative values indicating attentional bias away from T-N images. No significant difference was found in vigilance toward or disengagement from T-N and P-N images.

In conclusion, participants showed difficulty in disengaging from both negative and positive stimuli at 750 ms, and attentional bias away from only negative stimuli at 1250 ms.

3.3 Relationship between attentional bias and PTSD symptoms

Correlation analyses revealed that vigilance on P-N trials was negatively correlated with the intrusion score (r = −0.31, p < .05) at 500 ms; the vigilance on T-N trials was marginally positively correlated with both the PCL-5 total score (r = 0.28, p = .08) and the negative alterations in cognition and mood subscale scores (r = 0.29, p = .07) at 1250 ms. See Table S2 for a full report of the correlations.

The results of the regression analyses are shown in . At 1250 ms, the disengagement on T-N trials was marginally positively associated with PCL-5 total score (β = 1.12, t = 2.04, p = .06) and positively associated with the intrusion score (β = 1.17, t = 2.50, p < 0.05); the disengagement on P-N trials was negatively associated with the PCL-5 total score (β = −0.96, t = −2.40, p < .05), intrusion score (β = −0.93, t = −2.69, p < .05), and negative alterations in cognition and mood score (β = −0.89, t = −2.50, p < .05).

Table 3. Linear regression of attentional bias on PTSD symptoms.

4. Discussion

The current study is the first to evaluate the time course of attentional bias in bereaved Chinese parents who have lost their only child using dot-probe tasks with negative (trauma-related), positive, and neutral images as stimuli. The general time course of attentional bias and changes in bias direction in Shidu parents was illustrated. Furthermore, significant associations of attentional bias patterns with total PTSD symptoms and symptom clusters were demonstrated.

Specifically, participants showed difficulty in disengaging from both negative and positive stimuli at moderate stimulus exposures (750 ms) and avoidance of negative stimuli at long stimulus exposures (1250 ms), which partially supported our hypotheses. These findings also supported previous conclusions that attentional bias is a dynamic rather than static trait (Zvielli et al., Citation2016). The present study observed attentional bias, characterized by an initial difficulty in disengaging from stimuli and subsequent attentional avoidance of threats. A potential explanation of these findings is that attentional control and emotion regulation are impaired after trauma.

Attentional control, the ability to regulate attentional allocation, is regarded as top-down regulatory ability (Posner & Rothbart, Citation2000). According to attentional control theory, trauma might limit attentional control, including inhibition and shifting (Eysenck et al., Citation2007). Individuals with low attentional control exhibit difficulty in disengaging from emotional stimuli (Eysenck et al., Citation2007) that may activate fear memories and induce negative affect (Lazarov et al., Citation2019b). Emotion regulation is considered a coping strategy for managing negative emotions. Shifting attention away from threats may be a coping strategy employed to reduce negative mood (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2010; Shipherd & Beck, Citation2005). This coping strategy is consistent with characteristic strategic alterations among individuals with anxiety disorders (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2007). Shidu parents often exhibit exaggerated startle responses and irritability/anger in response to stimuli, which are the primary symptoms of PTSD development in this bereaved group (Eli et al., Citation2021). Prolonged hyperarousal (exaggerated startle responses and irritability) may impair attentional control and emotion regulation (Hayes et al., Citation2012), further contributing to attentional bias patterns, such as difficulty in disengaging from threatening stimuli and avoidance of threatening stimuli.

With respect to the emotional valence of stimuli, difficulty in disengaging was observed for both trauma-related and positive stimuli. This suggests that difficulty in disengaging is not limited to trauma-specific stimuli, in line with a previous study (Bardeen & Orcutt, Citation2011). This finding might also suggest that difficulty in disengaging might generalize to environmental information regardless of emotional valence in bereaved parents, which might be explained by the limited attentional control of traumatized individuals (Honzell et al., Citation2013). Individuals with impaired attentional control fail to redirect their attention from emotional stimuli (Eysenck et al., Citation2007). In contrast, avoidance of stimuli in the present study was specific to trauma-related stimuli at long stimulus exposures (1250 ms), which is consistent with previous findings (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2010; Sipos et al., Citation2014; Wald et al., Citation2011). Directing attention away from trauma-related stimuli might occur due to the dramatic increase in stress following difficulties in disengaging from trauma-related cues (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2010).

Another important finding in this study was that increased attentional avoidance of negative stimuli at long stimulus exposures (1250 ms) might be correlated with the severity of intrusion symptoms and total PTSD symptoms, which was inconsistent with our hypotheses. Previous studies have found a strong association between attentional bias and total PTSD symptoms among soldiers, survivors of rocket attacks, and civilian populations (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2010; Beevers et al., Citation2011; Wald et al., Citation2011). Attentional avoidance is regarded as a risk factor for PTSD symptoms and is thought to play an indirect role in PTSD symptom etiology by disrupting emotion regulation, including the successfully identification, processing, and acceptance of emotion (O’Bryan et al., Citation2015). In the current study, the relationship between attentional avoidance of trauma-related stimuli at long stimulus exposures (1250 ms) and intrusion symptoms might be related to the difficulty in disengaging from threats at moderate stimulus exposures (750 ms). Attentional interference (difficulty in disengaging) might evoke traumatic memories (Hayes et al., Citation2012), which underlie the intrusion symptoms and heightened negative emotional reactions (Lazarov et al., Citation2019b). In particular, Shidu parents in Chinese culture might show more intense negative emotions, such as self-blame and guilt (Eli, Citation2019), due to the perception of the death of a child as a sign of bad luck (Zheng & Lawson, Citation2015). Attentional bias away from trauma-related stimuli might be due to the dramatic increase in negative affect following difficulty in disengaging from trauma-related cues (Bar-Haim et al., Citation2010). Attentional avoidance as a maladaptive coping strategy might further aggravate PTSD symptoms (Mekawi et al., Citation2020). In addition, we also observed that increased difficulty in disengaging from positive stimuli at long stimulus exposures (1250 ms) might be correlated with reduced symptoms of intrusion, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and total PTSD symptoms at long stimulus exposures, which supports the findings of previous studies that attentional bias to positive stimuli might serve as a protective factor against PTSD symptoms (DePierro et al., Citation2013).

Contrary to our hypotheses, no attentional bias was found at rapid stimulus exposures (250 ms) or short stimulus exposures (500 ms). Research has indicated that attentional bias toward stimuli is an automatic, bottom-up process that enables faster orienting toward threat information (Cisler & Koster, Citation2010; Weierich et al., Citation2008). One possible reason for the absence of attentional bias toward stimuli in the present study is the stimulus exposure duration, which may not have been short enough. Some previous studies have found attentional bias toward threat-related stimuli in individuals with PTSD symptoms (DePierro et al., Citation2013; Fani et al., Citation2012b; Herzoga et al., Citation2019), while others failed to find such bias (N. Fani et al., Citation2012a; Schoorl et al., Citation2013). Further research is needed to address these mixed results.

The current study has several limitations. First, we were unable to examine the causal relationship between the onset of attentional biases and PTSD symptoms due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. The inability to establish causality also prevented us from determining whether attentional bias caused increased PTSD symptoms or vice versa. Hence, longitudinal studies are needed to determine causal patterns and directionality. Second, the participants were limited to Shidu parents, and the sample size was relatively small due to the difficulties in accessing this bereaved group. In addition, the lack of a control group limited our understanding of whether there are differences in attentional bias patterns between Shidu parents and parents with a living child. Future studies should consider adding nonbereaved parents as a control group to further explore the characteristics of attentional bias and its associations with PTSD symptoms. Third, we selected trauma-related stimuli in the dot-probe task to better understand attentional bias among Shidu parents. Some stimuli (e.g. images of children) that were regarded as traumatic/negative stimuli for Shidu parents may not be traumatic/negative stimuli for other traumatic groups. This stimuli choice has limited the findings of the current study to Shidu parents viewing trauma-related content. Future studies could test attentional bias among Shidu parents with trauma-unrelated stimuli. Last, although we controlled the time since the death of their child and removed outlier RTs in the analysis, the exact time since the death of their child varied, and there was high variance in RTs across participants. In addition, attentional bias patterns and associations with PTSD symptoms were investigated in the current study. The associations of attentional bias patterns with other relevant factors (e.g. depression, anxiety) should be explored in future studies to better interpret our findings. Thus, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution.

5. Conclusion

The present study is the first to investigate the time course of attentional bias among bereaved Chinese parents who have lost their only child (Shidu parents) and further clarified the association between attentional bias components and PTSD symptom clusters among Shidu parents. The results showed attentional bias, characterized by initial difficulty in disengaging from stimuli and subsequent attentional avoidance of threats. In addition, attentional bias (difficulty in disengaging from stimuli and bias away from threats) are correlated with PTSD symptoms and certain symptom clusters. These results expand our understanding of attentional bias patterns and cognitive–affective processes in trauma.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (98.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere thanks to all participants and organizations that supported this research. Furthermore, we are grateful for the assistance of Xuanang Liu and Fei Xiao in the acquisition of experimental materials as well as the assistance of Xuezhen Wang and Mengya Li in data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Due to considerations regarding participant privacy, the data that support the findings of this study are available only from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alon, Y., Azriel, O., Pine, D. S., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2023). A randomized controlled trial of supervised remotely-delivered attention bias modification for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 53(8), 3601–3610. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329172200023X

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Ashley, V., Honzel, N., Larsen, J., Justus, T., & Swick, D. (2013). Attentional bias for trauma-related words: Exaggerated emotional Stroop effect in Afghanistan and Iraq war veterans with PTSD. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-86

- Bar-Haim, Y., Holoshitz, Y., Eldar, S., Frenkel, T. I., Muller, D., Charney, D. S., Pine, D. S., Fox, N. A., & Wald, I. (2010). Life-threatening danger and suppression of attention bias to threat. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6), 694–698. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09070956

- Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., & van Ijzendoorn, M. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and non-anxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1

- Bardeen, J. R., & Orcutt, H. K. (2011). Attentional control as a moderator of the relationship between posttraumatic stress symptoms and attentional threat bias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(8), 1008–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.06.009

- Beevers, C. G., Lee, H., Wells, T. T., Ellis, A. J., & Telch, M. J. (2011). Association of predeployment gaze bias for emotion stimuli with later symptoms of PTSD and depression in soldiers deployed in Iraq. American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(7), 735. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10091309

- Blanco, C. (2011). Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (pp. 49–74). Wiley Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119998471.ch2

- Chan, C. L. W., Wang, C. W., Ho, A. H. Y., Qu, Z. Y., Wang, X. Y., Ran, M. S., & Al., E. (2012). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression among bereaved and non-bereaved survivors following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(6), 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.05.002

- Chen, E. (2013). The number of the only-child-died-families in China. Population and Development, 19(6), 100–103. (in Chinese). http://kns.cnki.net.psych.remotexs.cn.

- Cisler, J. M., & Koster, E. H. W. (2010). Mechanisms of attentional biases towards threat in anxiety disorders: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.003

- DePierro, J., D’Andrea, W., & Pole, N. (2013). Attention biases in female survivors of chronic interpersonal violence: Relationship to trauma-related symptoms and physiology. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.19135

- Earl, K., Robinson, A. K., Mills, A. M., Khanna, M. S., Bar-Haim, M. M., & Badura-Brack, Y. (2020). Attention bias variability and posttraumatic stress symptoms: The mediating role of emotion regulation difficulties. Cognition and Emotion, 34(6), 1300–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1743235

- Eli, B. (2019). Latent profiles and stage characteristics of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among parents who lost their only child [Master's thesis]. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences.

- Eli, B., Liang, Y., Chen, Y., Huang, X., & Liu, Z. (2021). Symptom structure of posttraumatic stress disorder after parental bereavement – a network analysis of Chinese parents who have lost their only child. Journal of Affective Disorders, 295, 673–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.123

- Eli, B., Zhou, Y., Liang, Y., Fu, L., Zheng, H., & Liu, Z. (2020). A profile analysis of post-traumatic stress disorder and depressive symptoms among Chinese shidu parents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1766770. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1766770

- Eysenck, M. W., Derakshan, N., Santos, R., & Calvo, M. G. (2007). Anxiety and cognitive performance: Attentional control theory. Emotion, 7(2), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.7.2.336

- Fani, N., Jovanovic, T., Ely, T. D., Bradley, B., Gutman, D., & Tone, E. B. (2012a). Neural correlates of attention bias to threat in post-traumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychology, 90(2), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.001

- Fani, N., Tone, E. B., Phifer, J., Norrholm, S. D., Bradley, B., & Ressler, K. J. (2012b). Attention bias toward threat is associated with exaggerated fear expression and impaired extinction in PTSD. Psychological Medicine, 42(3), 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001565

- Fox, E., Russo, R., Bowles, R., & Dutton, K. (2001). Do threatening stimuli draw or hold visual attention in subclinical anxiety? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 130(4), 681–700. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.130.4.681

- Hayes, J. P., VanElzakker, M. B., & Shin, L. M. (2012). Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: A review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6(89), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2012.00089

- Herzoga, S., D’Andreaa, W., & DePierrob, J. (2019). Zoning out: Automatic and conscious attention biases are differentially related to dissociative and post-traumatic symptoms. Psychiatry Research, 272(2019), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.110

- Hirai, M., Hernandez, E. N., Villarreal, D. Y., & Clum, G. A. (2022). Attentional bias toward threat in sexually victimized hispanic women: A Dot probe study. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 23(1), 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2021.1989108

- Honzell, N., Justus, T., & Swick, D. (2013). Event-related potentials reflect working memory limitations in post-traumatic stress disorder under dual-task conditions. Meeting of the cognitive-neuroscience-society.

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., Karam, E. G., Meron Ruscio, A., Benjet, C., Scott, K., Atwoli, L., Petukhova, M., Lim, C. C.W., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Bunting, B., Ciutan, M., de Girolamo, G., … Scott, K. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000708

- Kristensen, P., Weisæth, L., & Heir, T. (2012). Bereavement and mental health after sudden and violent losses: A review. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 75(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1521/psyc.2012.75.1.76

- Lazarov, A., Suarez-Jimenez, B., Tamman, A., Falzon, L., Zhu, X., Edmondson, D. E., & Neria, Y. (2019). Attention to threat in posttraumatic stress disorder as indexed by eyetracking indices: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 49(05), 705–726. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718002313

- Lukaschek, K., Kruse, J., Emeny, R. T., Lacruz, M. E., & Ladwig, K. H. (2013). Lifetime traumatic experiences and their impact on PTSD: A general population study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(4), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0585-7

- Machell, K. A., Goodman, F. R., & Kashdan, T. B. (2015). Experiential avoidance and wellbeing: A daily diary analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 29(2), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.911143

- McBride, D. M., & Dosher, B. A. (2002). A comparison of conscious and automatic memory processes for picture and word stimuli: A process dissociation analysis. Consciousness and Cognition, 11(3), 423–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8100(02)00007-7

- Mekawi, Y., Murphy, L., Munoz, A., Briscione, M., Tone, E. B., Norrholm, S. D., Jovanovic, T., Bradley, & Powers, A. (2020). The role of negative affect in the association between attention bias to threat and posttraumatic stress: An eye-tracking study. Psychiatry Research, 284(2020), 112674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112674

- Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (1998). A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(9), 809–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00063-1

- Mogg, K., & Bradley, B. P. (1999). Some methodological issues in assessing attentional biases for threatening faces in anxiety: A replication study using a modified version of the probe detection task. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(6), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00158-2

- O’Bryan, E. M., Mcleish, A. C., Kraemer, K. M., & Fleming, J. B. (2015). Emotion regulation difficulties and posttraumatic stress disorder symptom cluster severity among trauma-exposed college students. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 7(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037764

- O’Connor, M. (2010). PTSD in older bereaved people. Aging and Mental Health, 14(6), 670–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903311725

- Olatunji, B. O., Liu, Q., Zald, D. H., & Cole, D. A. (2022). Emotional induced attentional blink in trauma-exposed veterans: Associations with trauma specific and nonspecific symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 87(2022), 102541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102541

- Pagano, R. R. (2002). Understanding statistics in the behavioral sciences. 4th ed. Thomson Wadsworth.

- Pergamin-Hight, L., Naim, R., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2015). Content specificity of attention bias to threat in anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 35, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.10.005

- Pineles, S. L., Shipherd, J. C., Mostoufi, S. M., Abramovitz, S. M., & Yovel, I. (2009). Attentional biases in PTSD: More evidence for interference. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(12), 1050–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.08.001

- Posner, M. I., & Rothbart, M. K. (2000). Developing mechanisms of self-regulation. Development and Psychopathology, 12(3), 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400003096

- Salemink, E., Van Der Hout, M., & Kindt, M. (2007). Selective attention and threat: Quick orienting versus slow disengagement and two versions of the dot probe task. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(3), 607–615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.004

- Schoorl, M., Putman, P., & van Der Does, W. (2013). Attentional bias modification in posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(2), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1159/000341920

- Segal, A., Wald, I., Lubin, G., Fruchter, E., Ginat, K., Yehuda, A. B., Pine, D. S., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2020). Changes in the dynamic network structure of PTSD symptoms pre-to-post combat. Psychological Medicine, 50(5), 746–753. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000539

- Shipherd, J. C., & Beck, J. G. (2005). The role of thought suppression in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy, 36(3), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80076-0

- Sipos, M. L., Bar-Haim, Y., Abend, R., Adler, A. B., & Bliese, P. D. (2014). Postdeployment threat-related attention bias interacts with combat exposure to account for PTSD and anxiety symptoms in soldiers. Depression and Anxiety, 31(2), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22157

- Wald, I., Shechner, T., Bitton, S., Holoshitz, Y., Charney, D. S., Muller, D., Fox, N.A., Pine, D.S., & Bar-Haim, Y. (2011). Attention bias away from threat during life threatening danger predicts PTSD symptoms at one-year follow-up. Depression and Anxiety, 28(5), 406–411. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20808

- Wang, Z., & Xu, J. (2016). A cross-sectional study on risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder in Shidu parents of the Sichuan earthquake. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(9), 2915–2923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0454-1

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale Available from the National Center for PTSD., http://www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weber, D. L. (2008). Information processing bias in post-traumatic stress disorder. The Open Neuroimaging Journal, 2, 29–51. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874440000802010029

- Wei, Y., Jiang, Q., & Gietel-Basten, S. (2016). The well-being of bereaved parents in an onlychild society. Death Studies, 40(1), 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2015.1056563

- Weierich, M. R., Treat, T. A., & Hollingworth, A. (2008). Theories and measurement of visual attentional processing in anxiety. Cognition & Emotion, 22(6), 985–1018. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930701597601

- Yuval, K., Zvielli, A., & Bernstein, A. (2017). Attentional bias dynamics and posttraumatic stress in survivors of violent conflict and atrocities. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616649349

- Zhang, J., Liu, Z., Ma, J., Eli, B., Zhao, Y., & Liu, Y. (2019). Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and its related factors among parents who lost their single child. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 33(1), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2019.01.004

- Zheng, Y., & Lawson, T. R. (2015). Identity reconstruction as Shiduers: Narratives from Chinese older adults who lost their only child. International Journal of Social Welfare, 24(4), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/IJSW.12139

- Zinchenko, A., Al-Amin, M. M., Alam, M. M., Mahmud, W., Kabir, N., Reza, H. M., & Burne, T. H. J. (2017). Content specificity of attentional bias to threat in post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 50, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2017.05.006

- Zvielli, A., Amir, I., Goldstein, P., & Bernstein, A. (2016). Targeting biased emotional attention to threat as a dynamic process in time. Clinical Psychological Science, 4(2), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702615588048