ABSTRACT

Background: Partners and family can play a key role in encouraging military service and ex-service personnel to seek help for their mental health. Community Reinforcement Approach and Family Training (CRAFT) was developed to equip concerned significant others (CSOs) of those experiencing substance use disorders with skills to encourage their loved one to enter treatment and improve their own well-being. It was adapted in the US for CSOs of ex-service personnel with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (VA-CRAFT).

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate an adaptation of VA-CRAFT for use with CSOs of serving and ex-service personnel experiencing PTSD and Common Mental Disorders in the UK (UKV-CRAFT).

Method: Acceptability of UKV-CRAFT was assessed with interviews with experts, namely key stakeholders (n = 15) working in support provision for serving and ex-service personnel. In addition, individuals who took part in a small-scale demonstrative trial of UKV-CRAFT (three CSOs and three facilitators who delivered UKV-CRAFT) provided feedback.

Results: UKV-CRAFT was viewed positively, with interviewees highlighting that programmes like UKV-CRAFT filled a gap in provision for UK Armed Forces families as most services were only available to the serving or ex-service personnel. Interviewees praised how UKV-CRAFT enhanced CSO well-being and communication with their loved one. Concerns over the confidentiality of taking part in UKV-CRAFT were raised due to the perceived negative effects of highlighting a loved one’s mental ill health, especially for CSOs of serving personnel. Ideas for improvement included broadening access to all CSOs regardless of whether their loved one was seeking treatment.

Conclusion: Interviewees regarded UKV-CRAFT as a potentially useful intervention suggesting it could be proactively offered universally to support timely help-seeking if required. We recommend further evaluation of UKV-CRAFT on a wider scale, incorporating our recommendations, to assess its effectiveness accurately.

HIGHLIGHTS

Community Reinforcement And Family Therapy (CRAFT), a programme for the concerned significant others (CSOs) of people experiencing Substance Abuse Disorders (SUDs), was adapted for the CSOs of UK Armed Forces serving and ex-service personnel (UKV-CRAFT).

UKV-CRAFT aimed to equip CSOs with the skills to encourage their Armed Forces loved ones to seek mental health treatment; it was evaluated by post-trial interviews with UKV-CRAFT facilitators, recipients, and Armed Forces stakeholders.

UKV-CRAFT was found to be a useful intervention for CSOs but would benefit from further evaluation on a wider scale.

Evaluation of Community Reinforcement And Family Therapy in the UK military community.

Antecedentes: Las parejas y la familia pueden desempeñar un papel clave a la hora de alentar al personal del servicio militar y a ex militares a buscar ayuda para su salud mental. El Enfoque Comunitario de Reforzamiento y Entrenamiento Familiar (CRAFT, por sus siglas en inglés) se desarrolló para preparar a las Personas Involucradas y Preocupadas (CSOs, por sus siglas en inglés), de quienes experimentan Trastornos por Uso de Sustancias con habilidades, para alentar a sus seres queridos a iniciar tratamiento y mejorar su propio bienestar. Este enfoque fue adaptado en los EE.UU. para CSOs de ex militares con Trastorno de Estrés Postraumático (TEPT) (VA-CRAFT, por sus siglas en inglés).

Objetivo: Este estudio tuvo como objetivo evaluar una adaptación del VA-CRAFT para su uso con CSOs de personal en activo y ex militares que experimentan TEPT y trastornos mentales comunes en el Reino Unido (UKV-CRAFT, por sus siglas en inglés).

Método: La aceptabilidad del UKV-CRAFT se evaluó mediante entrevistas con expertos, concretamente actores claves (n = 15) que trabajan en la prestación de apoyo al personal activo y ex militares. Además, brindaron comentarios personas que participaron en una prueba demostrativa a pequeña escala del UKV-CRAFT (tres CSOs y tres facilitadores que implementaron el UKV-CRAFT).

Resultados: El UKV-CRAFT fue visto positivamente, y los entrevistados destacaron que programas como el UKV-CRAFT llenaron un vacío en proveer este tipo de programas para las familias de las Fuerzas Armadas del Reino Unido, ya que la mayoría de los servicios sólo estaban disponibles para el personal en servicio o ex militares. Los entrevistados elogiaron cómo el UKV-CRAFT mejoró el bienestar de las CSOs y la comunicación con sus seres queridos. Surgieron preocupaciones sobre la confidencialidad de la participación en el UKV-CRAFT, debido a los efectos negativos percibidos de resaltar la enfermedad mental de un ser querido, especialmente para las CSOs de personal en servicio. Las ideas de mejora incluyeron ampliar el acceso a todas las CSOs, independientemente de si el ser querido estaba buscando tratamiento.

Conclusión: Los entrevistados consideraron al UKV-CRAFT como una intervención potencialmente útil, lo que sugiere que podría ofrecerse de manera proactiva y universal para apoyar la búsqueda oportuna de ayuda, si fuera necesario. Recomendamos una evaluación adicional del UKV-CRAFT a una escala más amplia, incorporando nuestras recomendaciones, para evaluar su eficacia con precisión.

背景:伴侣和家人可以在鼓励军人和退役人员寻求心理健康帮助方面发挥关键作用。社区强化方法和家庭培训 (CRAFT) 旨在为患有药物滥用障碍的相关重要他人 (CSO) 提供技能,鼓励其亲人接受治疗并改善自身福祉。在美国,它被改编用于患有创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 的退役人员的 CSO (VA-CRAFT)。

目的:本研究旨在评估 VA-CRAFT 的适应性,以供英国经历 PTSD 和常见精神障碍的在职和退役人员的 CSO 使用(UKV-CRAFT)。

方法:通过采访专家,即为在职和退役人员提供支持的主要利益相关者 (n = 15),评估 UKV-CRAFT 的可接受性。此外,参加 UKV-CRAFT 小规模示范试验的个人(三名 CSO 和三名交付 UKV-CRAFT 的协调员)提供了反馈。

结果:UKV-CRAFT 受到积极评价,受访者强调,像 UKV-CRAFT 这样的项目填补了为英国武装部队家庭提供服务的空白,因为大多数服务仅向现役或退役人员提供。受访者称赞 UKV-CRAFT 如何增强公民社会组织的福祉以及与亲人的沟通。 人们对参加 UKV-CRAFT 的保密性表示担忧,因为强调亲人的精神疾病会带来负面影响,尤其是对现役人员的公民社会组织而言。改进的想法包括扩大与所有公民社会组织的联系,无论他们的亲人是否正在寻求治疗。

结论:受访者认为 UKV-CRAFT 是一种潜在有用的干预措施,表明可以主动普遍提供该干预措施,以在需要时及时支持寻求帮助者。我们建议结合我们的建议,在更广泛的范围内进一步评估 UKV-CRAFT,以准确评估其有效性。

1. Background

Community Reinforcement Approach and Family Training (CRAFT) was developed as a therapeutic programme to equip the concerned significant others (CSOs) of people experiencing Substance Use Disorders (SUDS) with the skills to a) persuade their loved one to seek professional help, b) improve their well-being, and c) improve their relationship with the loved one. The skills include but are not limited to, improving communication, increasing positive behaviours, and goal setting (Smith & Meyers, Citation2004).

CRAFT’s potential to support those experiencing SUDs with seeking professional support, commonly termed within CRAFT as ‘treatment entry’, has been examined extensively through over a dozen randomised controlled trials (Kirby et al., Citation2017; Sisson & Azrin, Citation1986). An early systematic review found CRAFT to have around twice the level of treatment entry compared to several alternative interventions, including the more widely-known Al-Anon and Johnson Intervention approaches (Roozen et al., Citation2010). Delivery of CRAFT and associated treatment entry rates vary across studies, but treatment entry rates for loved ones with SUDs have been consistently high where CRAFT has been delivered in a one-to-one format, with most achieving rates above 60% (Miller et al., Citation1999; Kirby et al., Citation1998; Meyers et al., Citation1998). A more recent review found multi-modality treatment, comprising of both one-to-one and group sessions, yielded the highest treatment entry rates (77% and 86%), compared to one-to-one (13%–71%), group (60%) and self-directed workbook (13%–40%) alone (Archer et al., Citation2020). This more recent review (Archer et al., Citation2020) identified three ‘essential elements’ characteristic of the most effective versions of CRAFT: thorough training and supervision for therapists delivering CRAFT; input from the CRAFT originators into the adaptation; and treatment for CSOs offered within the same service providing CRAFT. In addition to increased treatment entry amongst their loved ones, CSOs often report reductions in their own psychological symptoms following CRAFT and improvements in family functioning (Manuel et al., Citation2012; Waldron et al., Citation2007).

Recent research found 22% of regular British service and ex-service personnel had probable Common Mental Disorders (CMDs) such as depression and anxiety, and 6% had probable Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Stevelink et al., Citation2018). These data are elevated compared to rates of 17% (CMD) and 4.4% (PTSD) in the general UK population (McManus et al., Citation2016). Elevated rates of poor mental health are also seen in CSOs, particularly partners of service and ex-service personnel. A survey of partners of UK ex-service personnel with PTSD found 39% had probable depression, 37% a probable anxiety disorder and 17% probable PTSD (Murphy et al., Citation2016).

Delayed mental health support seeking has been associated with an increased risk of deprivation (measured by English Index of Multiple Deprivations) in ex-service personnel (Murphy et al., Citation2017), stressing the importance of timely help-seeking. However, evidence suggests only 55% of UK service personnel reporting a mental health concern access formal mental healthcare services (Stevelink et al., Citation2019). Significant barriers to seeking mental health care for ex-service personnel include an inability to identify their experiences as a mental health problem and a cultural aversion to acknowledging a need for help, with many ex-service personnel only doing so when they reach crisis points or are encouraged by a loved one (Rafferty et al., Citation2020). This suggests CSOs can be integral to recognising mental ill health and encouraging their loved ones to seek help.

1.1. The current intervention: UKV-CRAFT

CRAFT has been adapted by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for PTSD (NC-PTSD) for use with CSOs of US ex-service personnel (VA-CRAFT) (Erbes et al., Citation2020) with support from Robert Meyers, the creator of CRAFT and a veteran with lived experienced of PTSD. Pilot studies of VA-CRAFT targeting PTSD and Alcohol Use Disorders (AUD) indicate its usefulness in supporting CSOs, though VA-CRAFT did not increase the treatment entry rate of ex-service personnel (Erbes et al., Citation2015. Erbes et al., Citation2020). A number of other studies exploring CRAFT have similarly found improvements to CSO well-being irrespective of whether the loved one entered treatment (Dutcher et al., Citation2009; Meyers et al., Citation1998; Miller et al., Citation1999; Waldron et al., Citation2007).

Building upon this work, and with support from the VA-CRAFT developers and a psychologist at the VA who had previously worked on CRAFT studies, Dr Jennifer Manuel, UKV-CRAFT was developed for CSOs of UK ex-service and serving personnel experiencing PTSD and CMDs. The decision was taken to broaden the scope of the intervention to include CMDs as these are more prevalent than PTSD among the UK Armed Forces population (Stevelink et al., Citation2018). UKV-CRAFT represents a multimodal approach, combining weekly one-to-one treatment sessions over 6–12 weeks with a printed self-help workbook. The core contents of the programme were drawn from VA-CRAFT, Smith & Meyers’ CRAFT therapist manual (Smith & Meyers, Citation2004) and Meyers & Wolfe’s CRAFT self-help book (Meyers & Wolfe, Citation2003) and are summarised in . The content of UKV-CRAFT is very similar to VA-CRAFT, with minor changes made to the language to suit a UK audience.

Table 1. Outline of UKV-CRAFT Therapy Sessions.

Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners (PWPs) at a well-known UK military charity, Help for Heroes (CitationHelp For Heroes), were trained and supervised in CRAFT over two days by an experienced practitioner (Dr Jennifer Manuel) who was involved in the UKV-CRAFT development. These PWPs will be referred to as UKV-CRAFT facilitators. This adaptation of CRAFT met important criteria previously identified and outlined above (Archer et al., Citation2020): the UKV-CRAFT facilitators were given adequate supervision and input from the CRAFT originators throughout the trial.

A trial of UKV-CRAFT was completed with six CSOs who received one-one treatment sessions over 6–12 weeks. To assess the potential utility of UKV-CRAFT, measures of treatment entry of the loved one and CSO wellbeing pre and post-trial were taken. This paper reports on the final method of assessing potential utility; post-trial interviews with the CSOs and UKV-CRAFT facilitators who took part in the UKV-CRAFT trial. In addition, interviews with key stakeholders in military mental health support were held to gather broader feedback on the intervention. For further details about the UKV-CRAFT trial, please see the report (Greenberg et al., Citation2019).

2. Method

2.1. Design and procedure

An exploratory study using semi-structured interviews was conducted. MA conducted individual interviews in person or via telephone. These interviews were audio recorded with consent from interviewees. Interviews ranged in duration from 26 to 56 min. Interviewees were provided with a three-page document including an outline of the interview sections, main questions, UKV-CRAFT outline (see ) and examples of recruitment materials (supplementary material B) the day before. This allowed participants to prepare for the interview and provided reference points during the interview.

2.2. Participants

For the UKV-CRAFT trial, advertisements on social media were used to recruit CSOs. CSOs were eligible to take part in the trial if they met each of the criteria below:

Had a loved one who was serving, or had previously served, in the UK Armed Forces,

Was worried about either/both the effects of a loved one’s untreated or worsening mental health problems on their own wellbeing or/and how to get their loved one to seek professional help,

Had regular contact with their loved one,

The CSO and their loved one were both aged over 18,

Had a loved one who was not currently seeking professional help for their mental health,

Available for at least three or more consecutive weeks during the treatment period,

Able to give informed consent.

Interviewees (n = 21) included UKV-CRAFT CSOs, facilitators and stakeholders. UKV-CRAFT CSOs and facilitators who participated in the aforementioned UKV-CRAFT trial were invited to interview; three CSOs and three UKV-CRAFT facilitators agreed to participate. An additional 15 stakeholders were interviewed; these included individuals from organisations involved in delivering support services or policy development for Armed Forces members and their families ().

Table 2. List of Stakeholders Interviewed.

2.3. Measures

The interview comprised of a series of open-ended questions in six sections: 1. About the interviewee 2. About UKV-CRAFT (e.g. strengths/weaknesses), 3. Decision to try UKV-CRAFT 4. Making UKV-CRAFT visible and accessible, 5. Delivering UKV-CRAFT (e.g. special considerations for Armed Forces families), and 6. Talking to loved ones about mental health (e.g. suggestions on how to encourage help-seeking). The full schedule is presented in supplementary material A.

2.4. Analyses

MA manually transcribed the audio recordings verbatim. The interview transcripts were analysed using the Thematic Analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), facilitated by NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2012). After familiarisation with the transcripts, MA developed a list of initial ideas and tagged units of text with the same concept under a code. Themes were developed where multiple codes clustered together. These themes were then organised by defining overarching categories.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics

All three CSOs were female, and their loved ones were ex-service personnel who had left the UK Armed Forces by the time their CSO took part in the UKV-CRAFT trial. In regard to the relationship to the loved one, one CSO was a parent, one was their sister-in-law and the final CSO was a spouse.

Demographic information was not collected for the UKV-CRAFT facilitators. For stakeholders, their role and organisation is listed in .

3.2. Interview themes

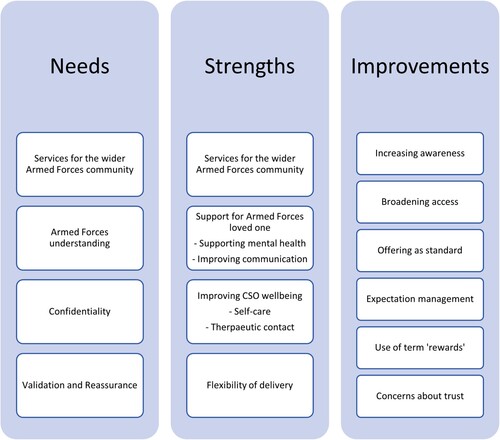

The interview themes are organised into three main categories: Needs of Armed Forces families, Strengths of UKV-CRAFT, and Ways to improve UKV-CRAFT (see ). The three categories are presented with a summary and the associated themes (italicised headers).

Needs of Armed Forces Families: Armed Forces families require support services that are underpinned by an understanding of the Armed Forces, confidential and provide reassurance that things can improve.

3.3. Service for the wider Armed Forces community

A recurring theme was that services for the wider Armed Forces community were inadequate. In relation to the direct needs of Armed Forces family members, there was a recognition that many military-focused mental health services were not open to them or might not meet their needs. Stakeholder 7 noted:

I know, for example, in [place in Wales] there’s a Department of Community Mental Health there, and you, a family member, can’t access the mental health service because of this constraint of funding, obviously, military funding, so a family member (who) has anxiety, depression, PTSD themselves, they have to leave the camp, go register on a primary care waiting list, which can be a year, so things almost need to change from that level for it to be accepted that maybe family members also need that extra bit of support.

3.4. Armed Forces understanding

The need for services for CSOs to be delivered by people who understand the specific experiences, culture, and challenges of Armed Forces personnel and their families was the most consistently stressed idea across all types of interviewees, including all three CSOs interviewed. Concerning UKV-CRAFT, Stakeholder 1 stressed:

It would be important for the person giving the intervention to have some understanding of military life, like the mobility, the separations, family dynamics, you know how long people remain in the service, what it takes to leave the service // not necessarily having to serve themselves // but just having an idea of someone's background, because it's not just an occupation, serving in the military, it's sort of a lifestyle.

3.5. Confidentiality

Interviewees expressed concerns about potential negative consequences of help-seeking within the Armed Forces, particularly pertaining to an Armed Forces loved one’s career. These concerns were discussed as potentially preventing Armed Forces personnel from seeking help. It was also reported that spouses, who along with their children are ‘dependents’ for their Armed Forces’ livelihood and military living quarters, are reluctant to draw attention to a mental health problem in their Armed Forces loved one for fear of a negative impact on income and career.

The perception within the military is that if you come forward for treatment, you will potentially be medically downgraded, which will affect your promotion, and you will potentially be discharged. And if you are going to be discharged then obviously lose your accommodation, and your livelihood. (Stakeholder 6)

3.6. Validation and reassurance

Several stakeholders emphasised services should offer hope that the situation would improve, and that CSOs’ struggles were valid and understandable.

I think reassurance early on in the process because I think one of the things I think when you’re really, really feeling that overt pressure that someone that you love is clearly compromised and a lot of other areas of your life probably are as well, you want someone to actually tell you ‘Look, beyond this, there is more and we are going to help you to get to that more. (Stakeholder 13)

Strengths of UKV-CRAFT: UKV-CRAFT can provide important and wide-ranging benefits to AF families

3.7. Service for the wider Armed Forces community

The focus on Armed Forces family members, particularly that UKV-CRAFT recognises their needs as individuals, as well as their supporting role, was identified as a key strength of UKV-CRAFT.

3.8. Support for the Armed Forces loved one: supporting mental health

The importance of UKV-CRAFT’s primary objective (i.e. increasing access to mental health treatment) was a recurring theme across many interviews. Interviewees endorsed the way in which family members encourage treatment access. In addition to facilitating initial help-seeking, the potential of UKV-CRAFT to provide CSOs with skills for ongoing support of their AF loved one was recognised.

I can see how the presence over a longer period of time of somebody who's got those skills – so if you go to a counselling session that might be one hour per week, whereas if you've got somebody in your house who can understand what you're going through and deal with it appropriately, that's going to have potentially a better positive impact as well, will complement it. (Stakeholder 3)

3.9. Support for the Armed Forces loved one: improving communication

Several interviewees, including all CSOs, reported that improving communication with their loved ones was of central importance. Interviewees praised UKV-CRAFT for helping CSOs plan and practise difficult conversations with Armed Forces loved ones giving them an optimum chance to provide support successfully. This was expressed by CSO 2:

It was really useful for me to have the space really to think about how I interact with my veteran and what words I do use. And have a little time and space to actually practise how I say things, it was actually really useful because it's something that you don't usually think about on a day-to-day basis.

3.10. Improving CSO well-being: self-care for the CSO

The secondary objective of UKV-CRAFT, improving CSO wellbeing, was referred to across many interviews. As UKV-CRAFT facilitator 3 observed:

Self-care's going to be really important for [CSOs] because if they're putting a lot of focus into one member of the family, which is to all intents and purposes being very intensive toward their needs. If you've got a serviceman in the family who suffers from PTSD or mental health issues, a lot of the focus goes to that person automatically. So if you've got a spouse who also has children to worry about, they're not going to be looking after themselves particularly well quite often, they're going to put themselves last on the list quite often.

I guess that’s also a weakness [of UKV-CRAFT], and I guess my concern will be more responsibility being placed on family members, but this emphasis on the self-care, that will balance this out, and it’s about getting that balance isn’t it.

3.11. Improving CSO well-being: therapeutic contact for the CSO

Whilst UKV-CRAFT is not designed to provide an explicitly therapeutic component for the CSO, interviewees reported value in sharing experiences and being listened to attentively by the UKV-CRAFT facilitator and that this contributed to improving CSO wellbeing.

3.12. Flexibility of delivery

The flexibility of the delivery of UKV-CRAFT, in terms of in-person or remotely, duration of programme, order of sessions, and timing, was also noted as particularly important to the CSO, and referenced across all types of interviewees. The discretion of phone or Skype sessions was also highlighted as important, given the concerns about confidentiality and Armed Forces loved one’s awareness that the CSO is engaged in the programme (noted below in ‘betrayal of trust’). This was expressed by CSO 1:

The main reason we went for the telephone was because if he [Armed Forces loved one] came through or anything, unexpectedly, I could just say something on the phone, whereas if it’d been Skype, it would have been harder to conceal.

Ways of improving UKV-CRAFT: Enhancing presentation of and access to UKV-CRAFT

Interviewees had very few direct criticisms of the intervention but provided some observations and ideas to improve the delivery of UKV-CRAFT.

3.13. Increasing awareness

Interviewees provided a wide range of views on how to make UKV-CRAFT visible and accessible to CSOs, giving mostly positive appraisal of the trial recruitment materials (Supplementary material B). Unit Welfare Officers (individuals in charge of personnel welfare in each military unit) were identified among the serving community as a potentially trusted gateway to signpost CSOs to UKV-CRAFT:

They [Unit Welfare Officers] could signpost a spouse who'd maybe plucked up the courage to come to them for advice on something other than, you know, housing, or anything to do with the day-to-day military life … you know families do trust the Unit Welfare Officers, they know that they're there to support them. (Stakeholder 1)

Because people don't really know what mental health problems are still, we're learning so much about it still, is it more comfortable, in I suppose lay person's terms ‘Are you having trouble sleeping?’ ‘Have you lost track of time?’ ‘Have you become withdrawn and not wanting to go out?’ rather than saying ‘mental illness?’ Problem drinking is a huge one, absolutely huge, just because of the military culture.

3.14. Broadening access to UKV-CRAFT

A wide range of interviewees across all categories suggested ways in which UKV-CRAFT could be made more inclusive to meet the needs of all CSOs. For example, a need to tailor the service to the specific circumstances of parent CSOs was stressed by CSO 1:

When you've only got that 10 or 15 min you can't jump in heavily and say things, and where a partner would be sharing a room with a person there's more opportunities to try and get them out of it. So, again, this where it is more difficult for parents than it is partners. Partners, they've got more access to the veteran. And even after having done that [UKV-CRAFT] course and everything I still don't know how to overcome that.

So someone, the veteran might well have taken those tentative steps towards seeking help but for whatever reason recoiled from it, either the waiting list was too long or, you know, something tangible like that. So, at that point, they're not necessarily eligible [for UKV-CRAFT] because they're kind of knocking on the door. So I think [it would be good] if we had more freedom to use CRAFT, even if their veteran were open to treatment.

3.15. Offered as standard

Several suggestions were also made about specific time points during a loved one’s military service when UKV-CRAFT might be particularly beneficial, such as prior to a loved one’s return from deployment or in anticipation of, or during, transitions out of the services, particularly in cases of medical discharge. On balance, there was a broad consensus that adapting and delivering UKV-CRAFT components for early detection of mental health distress and early intervention (rather than delivery at the point of crisis) would be highly beneficial.

3.16. Expectation management

Several interviewees commented on the need to manage CSO expectations, both for their own well-being and to reduce the risk of drop-out if things do not go as hoped. Expectation management is also connected to the challenges that Armed Forces loved ones, who are successfully persuaded to seek help, may face when they attempt to engage in treatment.

3.17. ‘Rewards’

‘Improving positive behaviours’ was the only UKV-CRAFT session to receive critical feedback from interviewees, including two of the three CSOs, and mostly focused on the use of the word ‘rewards’.

He was an officer, and he was responsible for hundreds of men, and he was making life or death decisions, and my concern with the word ‘reward’ is that it feels a little bit like treating him like a child, or a dog or something, like a dog biscuit.

3.18. Concerns about trust

Overlapping with Trust and Confidentiality, CSOs engaging with UKV-CRAFT shared concerns around ‘betraying’ trust by seeking support in relation to their Armed Forces loved one’s mental health. This was particularly sensitive and difficult for CSOs because their loved ones typically did not acknowledge a problem.

I don't think he realised how deeply we [the CSO and UKV-CRAFT facilitator] were going into it, and I think he would still probably get annoyed if he thought that we were talking about problems that he had because he still doesn't see that he has a problem. (CSO 1)

4. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate whether UKV-CRAFT might be an acceptable intervention to support CSOs of serving and ex-service personnel experiencing PTSD and Common Mental Disorders in the UK (UKV-CRAFT). The principal findings indicate a perceived gap in service provision for the wider Armed Forces community and UKV-CRAFT could be both beneficial and acceptable for this community. The strengths reported (supporting treatment, self-care for CSOs, improving communication) mirrored the goals of CRAFT (treatment entry of loved one, improving CSO wellbeing and improving the relationship between CSO and loved one). This mirroring indicates both a need for, and an acceptability of CRAFT to support the wider Armed Forces community within the UK. Several suggestions for improvement were made, including broadening access to all CSOs regardless of which stage their loved one was on their help-seeking journey.

The flexibility of delivery, including the option to do the sessions in person or via video call, was highlighted as a strength by interviewees. The combination of weekly one-to-one facilitator-led sessions with the self-guided workbook in the UKV-CRAFT programme also struck a satisfactory balance of convenience, autonomy, and expert support. As mentioned earlier, a pilot study of the web-based VA-CRAFT – entirely self-guided – showed promise in reducing caregiver burden but did not enhance treatment initiation (Erbes et al., Citation2020). Similarly, a recently published randomised controlled trial of a web-based CRAFT programme for alcohol misuse disorder failed to demonstrate substantial changes regarding treatment initiation for loved ones or CSO mental health (EÉk et al., Citation2020). Although our study was unable to provide solid conclusions about the effectiveness of UKV-CRAFT delivered via mixed modalities, it does offer a good insight into the preference of CSOs and might suggest having a choice over delivery is key as opposed to the format itself.

Findings indicate there is a distinct impression that, in many cases, loved ones ‘were not treatment resistant’, rather they are seeking treatment but experience frustration when trying to access it. This links to previous research, which found many ex-service personnel actively seek mental health support but face several barriers when seeking this support, including eligibility and access concerns (Rafferty et al., Citation2020). Therefore, efforts to engage CSOs in programmes like UKV-CRAFT should anticipate, and provide for, the possibility that CSOs might also be disengaged through experiences of prior unsuccessful attempts to gain access to services. This highlights the importance of signposting being an integral part of programmes like UKV-CRAFT as there are plenty of organisations offering support, but individuals are not always aware of them or have difficulty navigating which ones would be most suitable for their needs.

5. Study limitations

This study was the first to adapt VA-CRAFT for a UK population and provides initial evidence for its acceptability in this population. However, this evaluation was limited by the small number of CSOs who took part in the trial and furthermore, only half of those consented to be interviewed. This meant relying mostly on the interviews with stakeholders, many of whom had relatively superficial familiarity with UKV-CRAFT. Whilst these interviews provided valuable feedback based on their experience of providing services, it is not clear if these views are reflective of CSOs. For example, only stakeholders mentioned the need to reassure CSOs and provide validation of their difficulties, a point not raised by the CSOs. Therefore, a larger trial of UKV-CRAFT is needed to fully assess its acceptability.

6. Recommendations

Interviewees pointed out that broadening access to all CSOs, including CSOs with loved ones currently seeking or receiving treatment would be beneficial given the fact that their loved ones might face several unsuccessful attempts to seek help. This would also change the intervention's primary emphasis in line with interviewees’ recommendations, lessening the focus on treatment entry and increasing the emphasis on the other two aims of CRAFT: improving CSO well-being and improving the relationship between the CSO and their loved one. By focusing on these other aims, loved ones’ treatment adherence might be subsequently improved. For example, self-stigma can be a barrier to help-seeking in ex-service personnel (Mellotte et al., Citation2017), and so providing CSOs with the skills to address this with their loved one may help mitigate this barrier. This approach has demonstrated some success in the US, where significant reductions in CSO anxiety and depression were observed after involvement in a four-session web-based intervention ‘Partners Connect’ – which had the more modest goal of addressing CSOs’ own mental health concerns and enhancing their communication skills (Osilla et al., Citation2018).

Similarly, a key recommendation from interviewees was that UKV-CRAFT be made widely available as a universal and/or preventative resource. For example, interviewees suggested it could be provided in anticipation of a major stressor, such as after a deployment or transition out of the Armed Forces. A similar programme called ‘Families Over Coming Under Stress (FOCUS)’ is a preventative intervention offered to US Armed Forces parents (both civilian and military parents) and their children at active-duty military institutions in US and Japan. A longitudinal evaluation of this found both military and civilian parents who completed the intervention showed improvement in depression, anxiety and PTSD symptoms over time (Lester et al., Citation2016). Due to limited resources, it may not be feasible to offer UKV-CRAFT to all CSOs before any problems occur. However, the core contents of UKV-CRAFT could be adapted into an online package, advertised by Unit Welfare Officers as suggested by interviewees or through charities such as the Army/Navy/RAF family federations. This would allow all individuals to learn the same skills before problems occur but continue to provide the full, in-person version to those whose loved ones develop a mental health problem.

Future delivery of UKV-CRAFT should take into consideration interviewees’ desire for the intervention to be delivered as external to the Ministry of Defence (MoD) to alleviate concerns around confidentiality but also delivered by those with an understanding of the Armed Forces and its culture. As highlighted in previous research, it is necessary to consider the Armed Forces’ specific institutional culture when developing CBT approaches (Farrand et al., Citation2019).

7. Conclusions

This research demonstrates a perceived gap in support provision for the wider Armed Forces community. UKV-CRAFT represents an intervention that can provide support for Armed Forces CSOs and support for serving and ex-service personnel who may be resistant to seeking mental health support.

The research has illustrated that broadening the scope of UKV-CRAFT could support not just those who are treatment resistant, but those seeking or engaged in treatment as well. Even more inclusively, UKV-CRAFT could support those who are not experiencing mental health distress but perhaps undergoing a transition, such as the transition out of the Armed Forces, or even as a preventative measure to foster mental resilience.

At the very least, the findings from this study have raised awareness of the needs of the wider Armed Forces community and the need for more targeted provisions. It is hoped further evaluations of UKV-CRAFT or the development of similar interventions will be conducted, noting the recommendations made in this paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study was granted by King’s College London’s Research Ethics Office (reference numbers: RESCM-17/18-4715).

Competing interests

BC, MA, SS, HH and LR have no competing interests. NG is a trustee with the Society and Faculty of Occupational Medicine and also runs March on Stress, a psychological health consultancy.

Copyright statement

For the purposes of open access, the author has applied a Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence to any Accepted Author Manuscript version arising from this submission.

Revised CRAFT Supplementary Materials.docx

Download MS Word (1.8 MB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Help for Heroes for commissioning and funding the research and also for their excellent support and continued engagement throughout the project.

Special thanks also to Dr Jennifer Manuel who was involved in the development of the intervention and training of practitioners in the UKV-CRAFT process as well as to Dr Eric Kuhn and Dr Chris Erbes who provided their VA-CRAFT web-based intervention materials and feedback at critical stages of development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Archer, M., Harwood, H., Stevelink, S., Rafferty, L., & Greenberg, N. (2020). Community reinforcement and family training and rates of treatment entry: A systematic review. Addiction, 115(6), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14901

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Dutcher, L. W., Anderson, R., Moore, M., Luna-Anderson, C., Meyers, R. J., Delaney, H. D., & Smith, J. E. (2009). Community reinforcement and family training (CRAFT): An effectiveness study. Journal of Behavior Analysis in Health, Sports, Fitness and Medicine, 2(1), 80–90.

- Eék, N., Romberg, K., Siljeholm, O., Johansson, M., Andreasson, S., Lundgren, T., Fahlke, C., Ingesson, S., Bäckman, L., & Hammarberg, A. (2020). Efficacy of an internet-based community reinforcement and family training program to increase treatment engagement for AUD and to improve psychiatric health for CSOs: A randomized controlled trial. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 55(2), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agz095

- Erbes, C. R., Kuhn, E., Gifford, E., Spoont, M. R., Meis, L. A., Polusny, M. A., Oleson, H., Taylor, B. C., Hagel-Campbell, E. M., & Wright, J. (2015). A pilot trial of VA-CRAFT: Online training to enhance family well-being and veteran mental health service use. VA HSR&D / QUERI National Meeting.

- Erbes, C. R., Kuhn, E., Polusny, M. A., Ruzek, J. I., Spoont, M., Meis, L. A., Gifford, E., Weingardt, K. R., Campbell, E. H., Oleson, H., & Taylor, B. C. (2020). A pilot trial of online training for family well-being and veteran treatment initiation for PTSD. Military Medicine, 185(3–4), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz326

- Farrand, P., Mullan, E., Rayson, K., Engelbrecht, A., Mead, K., & Greenberg, N. (2019). Adapting CBT to treat depression in Armed Forces veterans: Qualitative study. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 47(5), 530–540. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465819000171

- Greenberg, N., Stevelink, S. A. M., Rafferty, L., Archer, M., & Harwood, H. (2019). HALO: The helping Armed Forces loved ones study.

- Help For Heroes. About us. https://www.helpforheroes.org.uk/about-us/.

- Kirby, K. C., Benishek, L. A., Kerwin, M. E., Dugosh, K. L., Carpenedo, C. M., Bresani, E., Haugh, J. A., Washio, Y., & Meyers, R. J. (2017). Analyzing components of Community reinforcement and family training (CRAFT): Is treatment entry training sufficient? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(7), 818–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000306

- Kirby, K. C., Marlowe, D. B., Festinger, D. S., Garvey, K. A., & La Monaca, V. (1998). Community reinforcement training for family and significant others of drug abusers: A unilateral intervention to increase treatment entry of drug users. Drug and alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 56(1), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00022-8

- Lester, P., Liang, L. J., Milburn, N., Mogil, C., Woodward, K., Nash, W., Aralis, H., Sinclair, M., Semaan, A., Klosinski, L., Beardslee, W., & Saltzman, W. (2016). Evaluation of a family-centered preventive intervention for military families: Parent and child longitudinal outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(1), 14–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.10.009

- Manuel, J. K., Austin, J. L., Miller, W. R., McCrady, B. S., Tonigan, J. S., Meyers, R. J., Smith, J. E., & Bogenschutz, M. P. (2012). Community reinforcement and family training: A pilot comparison of group and self-directed delivery. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 43(1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.020

- McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., & Brugha, T. (2016). Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. NHS Digital.

- Mellotte, H., Murphy, D., Rafferty, L., & Greenberg, N. (2017). Pathways into mental health care for UK veterans: A qualitative study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1389207. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1389207

- Meyers, R. J., Mille, W. R., Hill, D. E., & Tonigan, J. S. (1998). Community reinforcement and family training (CRAFT): Engaging unmotivated drug users in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse, 10(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3289(99)00003-6

- Meyers, R. J., & Wolfe, B. I. (2003). Get your loved one sober: Alternatives to nagging, pleading, and threatening. Hazelden Publishing.

- Miller, W. R., Meyers, R. J., & Tonigan, J. S. (1999). Engaging the unmotivated in treatment for alcohol problems: A comparison of three strategies for intervention through family members. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(5), 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.67.5.688

- Murphy, D., Palmer, E., & Busuttil, W. (2016). Mental health difficulties and help-seeking beliefs within a sample of female partners of UK veterans diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 5(8), 68.

- Murphy, D., Palmer, E., & Busuttil, W. (2017). Exploring indices of multiple deprivation within a sample of veterans seeking help for mental health difficulties residing in England. Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health Reviews, 1(6), 1–6.

- Osilla, K. C., Trail, T. E., Pedersen, E. R., Gore, K. L., Tolpadi, A., & Rodriguez, L. M. (2018). Efficacy of a web-based intervention for concerned spouses of service members and veterans with alcohol misuse. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 44(2), 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12279

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2012). NVivo qualitative data analysis Software. 10th ed.

- Rafferty, L. A., Wessely, S., Stevelink, S. A. M., & Greenberg, N. (2020). The journey to professional mental health support: A qualitative exploration of the barriers and facilitators impacting military veterans’ engagement with mental health treatment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1700613. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1700613

- Roozen, H. G., De Waart, R., & Van Der Kroft, P. (2010). Community reinforcement and family training: An effective option to engage treatment-resistant substance-abusing individuals in treatment. Addiction, 105(10), 1729–1738. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03016.x

- Sisson, R. W., & Azrin, N. H. (1986). Family-member involvement to initiate and promote treatment of problem drinkers. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 17(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(86)90005-4

- Smith, J. E., & Meyers, R. J. (2004). Motivating substance abusers to enter treatment: Working with family members. Guilford Press.

- Stevelink, S. A. M., Jones, M., Hull, L., Pernet, D., MacCrimmon, S., Goodwin, L., MacManus, D., Murphy, D., Jones, N., Greenberg, N., Rona, R. J., Fear, N. T., & Wessely, S. (2018). Mental health outcomes at the end of the British involvement in the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: A cohort study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(6), 690–697. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.175

- Stevelink, S. A. M., Jones, N., Jones, M., Dyball, D., Khera, C. K., Pernet, D., MacCrimmon, S., Murphy, D., Hull, L., Greenberg, N., MacManus, D., Goodwin, L., Sharp, M.-L., Wessely, S., Rona, R. J., & Fear, N. T. (2019). Do serving and ex-serving personnel of the UK armed forces seek help for perceived stress, emotional or mental health problems? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1556552. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1556552

- Waldron, H. B., Kern-Jones, S., Turner, C. W., Peterson, T. R., & Ozechowski, T. J. (2007). Engaging resistant adolescents in drug abuse treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 32(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.007