ABSTRACT

Background: The mental health impacts of climate change-related disasters are significant. However, access to mental health services is often limited by the availability of trained clinicians. Although building local community capability for the mental health response is often prioritised in policy settings, the lack of evidence-based programs is problematic. The aim of this study was to test the efficacy of the Skills for Life Adjustment and Resilience programme (SOLAR) delivered by trained local community members following compound disasters (drought, wildfires, pandemic-related lockdowns) in Australia.

Method: Thirty-six community members were trained to deliver the SOLAR programme, a skills-based, trauma informed, psychosocial programme. Sixty-six people with anxiety, depression and/or posttraumatic stress symptoms, and impairment were randomised into the SOLAR programme or a Self-Help condition. They were assessed pre, post and two months following the interventions. The SOLAR programme was delivered across five 1-hourly sessions (either face to face or virtually). Those in the Self-Help condition received weekly emails with self-help information including links to online educational videos.

Results: Multigroup analyses indicated that participants in the SOLAR condition experienced significantly lower levels of anxiety and depression, and PTSD symptom severity between pre – and post-intervention (T1 to T2), relative to the Self-Help condition, while controlling for scores at intake. These differences were not statistically different at follow-up. The SOLAR programme was associated with large effect size improvements in posttraumatic stress symptoms over time.

Conclusion: The SOLAR programme was effective in improving anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms over time. However, by follow-up the size of the effect was similar to an active self-help condition. Given the ongoing stressors in the community associated with compounding disasters it may be that booster sessions would have been useful to sustain programme impact.

Trial registration: Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry identifier: ACTRN12621000283875..

HIGHLIGHTS

We tested the efficacy of a brief, skills-based psychosocial programme under randomised controlled conditions following compound disasters.

The SOLAR programme was associated with improvements in anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms across time.

The SOLAR programme may benefit from booster sessions especially where there are ongoing impacts of disaster.

Antecedentes: Los impactos en la salud mental de los desastres relacionados con el cambio climático son significativos. Sin embargo, el acceso a los servicios de salud mental es a menudo limitado por la disponibilidad de clínicos entrenados. Aunque construir la capacidad de la comunidad local para la respuesta de salud mental es a menudo priorizada en los contextos de política, la carencia de programas basados en la evidencia es problemática. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la eficacia del programa de Habilidades para Adaptación Vital y Resiliencia (SOLAR en su sigla en inglés) implementado por miembros de la comunidad local entrenados luego de desastres compuestos (sequia, incendios forestales, confinamiento relacionado a pandemia) en Australia.

Método: Treinta y seis miembros de la comunidad fueron entrenados para implementar el programa SOLAR, un programa psicosocial, informado en el trauma, basado en habilidades. Sesenta y seis personas con ansiedad, depresión y/o síntomas de estrés postraumático, y discapacidad fueron asignadas de manera aleatoria al programa SOLAR o una condición de Auto-Ayuda. Fueron evaluados antes, después y dos meses luego de las intervenciones. El programa SOLAR fue entregado en cinco sesiones de una hora (ya sea en persona o virtualmente). Aquellos en la condición de Auto-Ayuda recibieron correos semanales con información de auto-ayuda, incluyendo los enlaces a videos educacionales en línea.

Resultados: Los análisis de los multigrupos indicaron que los participantes en la condición SOLAR experimentaron niveles significativamente menores de ansiedad y depresión, y severidad de los síntomas del TEPT entre antes y después de la intervención (T1 a T2), en relación a la condición de Auto-Ayuda, mientras se controlaron los puntajes al tamizaje. Estas diferencias no fueron estadísticamente significativas en el seguimiento. El programa SOLAR se asoció con un tamaño del efecto grande en los síntomas de estrés postraumático en el tiempo.

Conclusión: El programa SOLAR fue efectivo en mejorar la ansiedad, la depresión, y los síntomas de estrés postraumáticos en el tiempo. Sin embargo, en el seguimiento, el tamaño del efecto fue similar a la condición activa de auto-ayuda. Dado los estresores en curso en la comunidad asociados con los desastres compuestos puede ser que las sesiones de refuerzo podrían ser útiles en mantener el impacto del programa.

背景:气候变化相关灾害对心理健康的影响是巨大的。然而,获得心理健康服务的机会往往受到训练有素临床医生的限制。尽管在政策制定中经常优先考虑建设当地社区的心理健康应对能力,但缺乏循证计划是个问题。本研究旨在是检验澳大利亚发生复合灾害(干旱、野火、大流行相关封锁)后由训练有素的当地社区成员实施的生活调整和心理韧性计划 (SOLAR) 的有效性。

方法:36 名社区成员接受了 SOLAR 计划的培训,这是一项基于技能、创伤知情的社会心理计划。66 名患有焦虑、抑郁和/或创伤后应激症状以及损伤的人被随机分配到 SOLAR 计划或自助条件组。他们在干预前、后和干预后两个月进行了评估。SOLAR 项目分为五次,每次 1 小时(面对面或虚拟)。处于自助条件的人每周都会收到包含自助信息的电子邮件,其中包括在线教育视频的链接。

结果:多组分析表明,相对于自助条件,在干预前和干预后(T1 至 T2)之间,SOLAR 条件下的参与者的焦虑和抑郁水平以及 PTSD 症状严重程度显著降低,同时控制了入组时得分。这些差异在随访时没有统计学差异。随着时间的推移,SOLAR 计划与创伤后应激症状的显著改善相关。

结论:随着时间的推移,SOLAR 计划可有效改善焦虑、抑郁和创伤后应激症状。然而,通过随访,效果的大小与主动自助状态相似。 鉴于社区中持续存在的与复杂灾难相关的压力源,加强会议可能有助于维持计划的影响。

Climate change is associated with an increased frequency of extreme weather events, natural hazards and disasters that impact populations globally (Banholzer et al., Citation2014). There is increasing awareness of the mental health impacts of climate change-related events (Gibson et al., Citation2020). These include acute events such as cyclones and wildfires, and subacute events such as drought and heat stress (Palinkas & Wong, Citation2020). Such events are typically associated with elevated rates of psychiatric disorders, especially anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (Beaglehole et al., Citation2018 Cianconi et al., Citation2020;). Other reactions are also prevalent, including anger and hostility (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2021), sleep disturbances, and elevated psychological distress (Beaglehole et al., Citation2018). These mental health impacts may be even more severe in the context of compounding exposures to multiple disasters, which is occurring more frequently (Cowlishaw et al., Citation2022 Leppold et al., Citation2022;). This is a substantial driver of health inequities amongst minority communities more directly affected by climate change-related threats (Pearson et al., Citation2023). The challenge for researchers, clinicians and government is how best to manage the overwhelming mental health need that is associated with these disasters.

Many disaster mental health frameworks have guiding principles that call for the development of local community capability to support mental health response and recovery (National Mental Health Commission, Citation2022). They also promote the expansion of non-specialist support or task shifting models to help meet the high levels of mental health and wellbeing need in the aftermath of a disaster (National Mental Health Commission, Citation2022). Task shifting is commonly utilised in resource poor settings and acts to shift service delivery of specific tasks from highly qualified health workers to people with lower qualifications (World Health Organization, Citation2008). In the aftermath of disaster however, it is important that mental health task shifting models incorporate programs that are trauma-informed, given the potentially traumatic impact of disasters on individuals and the community.

There are a number of task shifting interventions that are often implemented after disaster that aim to target psychosocial distress. Psychological First Aid is a universal intervention that is routinely delivered in the aftermath of disaster to support distressed individuals – however, there remains little rigorous evidence regarding the benefits of Psychological First Aid (Hermosilla et al., Citation2023), while the intervention principles are arguably relevant across service levels, including basic services and community supports. Problem Management Plus (PM+) is a transdiagnostic task-shifting intervention that was developed mainly for low- and middle-income countries, and has a growing evidence-based suggesting beneficial effects (Schäfer et al., Citation2023). However, this approach does not include trauma focussed content (rather, sessions focus on managing stress, problem solving, behavioural activation, and strengthening social support), and accordingly studies suggest smaller impacts on trauma-related symptoms (Hermosilla et al., Citation2023), when compared to outcomes such as psychological distress. Finally, the Skills for Psychological Recovery (Berkowitz et al., Citation2010) programme was designed to be delivered after disaster by paraprofessionals and is trauma informed. However, it has been criticised for being too complex for delivery by lay community members (Berkowitz et al., Citation2010), which may speak to the lack of published trials investigating its efficacy. As such, there remains a need for additional forms of brief, evidenced based, trauma-informed psychosocial intervention which are accessible, adaptable, and feasibly delivered by laypeople to address the emerging mental health needs of individuals post-disaster.

To address this gap, the Skills for Life Adjustment and Resilience (SOLAR) programme was developed by an International Expert Group in accordance with the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for developing a complex intervention (Craig et al., Citation2008). This involved a scoping literature search process to identify relevant mechanisms of trauma recovery and evidence-based intervention; a ranking process to identify and weight treatment components for inclusion in the SOLAR program; and an international roundtable meeting of experts to reach a consensus on the inclusion of components in the SOLAR programme. Further details of the development of the programme and its content are presented elsewhere (O’Donnell et al., Citation2020). The SOLAR programme is a brief, trauma-informed, skills-based psychosocial programme that can be delivered by trained lay community members. The initial open-label pilot study of the SOLAR programme delivered by local community members after a wildfire provided initial evidence of its safety, feasibility and acceptability (O’Donnell et al., Citation2020). Subsequent studies have provided preliminary evidence of its efficacy. A culturally adapted version of the SOLAR programme was tested in two remote, cyclone-affected communities in the Pacific Island nation of Tuvalu (n = 99) using a quasi-experimental controlled design (Gibson et al., Citation2021). In this study the SOLAR programme was delivered in a group format by community members with varied community and leadership roles, and was associated with large, significant reductions in psychological distress, posttraumatic stress symptoms and impairment relative to a usual care condition (Gibson et al., Citation2021). Significant benefits were sustained at 6-month follow-up (Gibson et al., Citation2021). A randomised-controlled feasibility study in Germany with trauma survivors with adjustment disorder (n = 30) found medium-sized effects of the SOLAR intervention in reducing insomnia, improving quality of life and perceived social support, and small effects on distress and functional impairment – relative to a wait-list control (Lotzin et al., Citation2022). While these studies offer emerging support for the SOLAR programme, further methodologically rigorous studies in different national contexts are required.

The aim of this project was to investigate the efficacy of the SOLAR programme delivered by trained community members to residents of disaster-affected regions in Australia using a randomised controlled trial design. The programme was delivered after the 2019/2020 Black Summer wildfires (known in Australia as ‘bushfires’) in a region of Australia already impacted by widespread drought. The communities who took part in the trial were also severely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic which was associated with prolonged lockdowns that restricted social movement and delayed disaster recovery processes. It was hypothesised that the delivery of the SOLAR programme would result in greater reductions in psychological distress symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms and transdiagnostic constructs including anger intensity and sleep impairment, relative to targeted self-help information provided online, and that these reductions would be maintained at two-month follow-up.

1. Methods

1.1. Study design and participant recruitment

This project was a two-arm randomised controlled trial. SOLAR was delivered one-on-one by trained community members across five weekly sessions, and was compared to a purposively developed self-help programme that entailed five weekly emails providing information and strategies for wellbeing.

Participants were eligible to participate if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) lived in disaster affected regions of rural or regional Victoria, Australia, or had experience of a recent disaster in these regions, including drought, wildfires, and/or the COVID-19 pandemic; (ii) reported elevated levels of psychological distress associated with their experiences, defined by scores ≥4 on the Patient Heath Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) or the Generalised Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., Citation2006), and functional impairment in daily life as a result of these distress symptoms (impairment rated as ≥3 on a Likert scale from 1 to 10); and (3) had sufficient English comprehension to provide informed consent. Key exclusion criteria included: (i) reporting a severe mental disorder or cognitive impairment (e.g. severe intellectual disability, dementia, psychosis, mania); (ii) being at moderate to high risk of self-harm or suicide; and (iii) scores >19 on PHQ-9 or >14 on GAD-7 and an agreement by the individual to pursue a more intensive type of psychological treatment from a mental health professional, (iv) currently receiving other psychological interventions for mental health.

1.2. Procedure

Participant recruitment strategies were designed in the context of pandemic-related public health measures that were in place during the study, including restrictions on movement which prevented travel and visitations to disaster impacted communities. Accordingly, recruitment strategies were predominantly those which could be implemented remotely, via geotargeted social media promotions, advertisements in local media, and targeted social media campaigns by an external research recruitment company. Some participants were also recruited via in-person invitations issued by SOLAR Coaches through their local communities or workplaces. A target sample size of n = 80 was set based on a power analysis for a between-subjects ANCOVA for main effects and interaction, which compares post-test scores between groups while controlling for pre-test scores under the assumption of homogeneity of slopes and variances between groups.

A member of the research team conducted eligibility assessments with prospective participants via telephone. Those who met inclusion criteria were invited to provide informed consent to participate in the study. Participants were randomly allocated to the SOLAR or self-help control condition using permuted block randomisation, and completed self-report measures via an online survey platform at three time points – pre-intervention (T1), after intake but prior to treatment randomisation; post-intervention (T2), within two weeks following their respective intervention; and follow-up (T3), 2-months after completing their respective intervention.

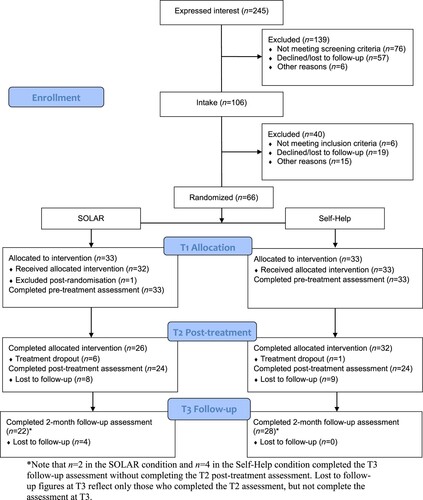

Sixty-six people were recruited for the study and were randomly allocated to receive either SOLAR (n = 33) or the self-help control intervention (n = 33). Participants were recruited between April 2021 and September 2022 which was approximately a year following wildfires and during the COVID pandemic, with associated lockdowns and travel restrictions. Participants in the SOLAR condition could choose to receive it face-to-face (if located geographically close to an available SOLAR Coach) or remotely via videoconferencing. The self-help control condition comprised a 5-week programme of self-directed resources distributed weekly via email. These resources included text and video-based resources including strategies for healthy living, self-care, managing emotions, accessing social support, and overcoming avoidance, and were available on the Phoenix Australia website (https://www.phoenixaustralia.org/your-recovery/helping-yourself/). All participants in the self-help control condition were able to receive SOLAR treatment after the T3 assessment window had passed. Ethics approval for the study was provided by the University of Melbourne Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC ID 14453) and the trial was prospectively registered in the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12621000283875). See for a CONSORT diagram depicting the flow of participants throughout the trial.

1.3. Measures

1.3.1. Intake and screening measures

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., Citation2001) comprises nine self-report items which participants rate on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’) with reference to how often in the past two weeks they have experienced depression symptoms. Scores are summed to produce an overall severity score ranging from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater distress. The PHQ-9 has strong psychometric properties, with high levels of reliability and validity when used with comparable populations (Kroenke et al., Citation2001).

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., Citation2006) comprises seven self-report items which participants rate on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from 0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’) with reference to how often in the past two weeks they have experienced anxiety symptoms. Scores are summed to produce an overall severity score, with scores ranging from 0 to 21, and higher scores indicating greater anxiety. The GAD-7 has excellent psychometric properties, with high reliability and construct and convergent validity (Johnson et al., Citation2019 Spitzer et al., Citation2006;).

1.3.2. Primary clinical outcomes

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins et al., Citation2015) was used to measure the severity of post-traumatic stress symptoms over the past week. The scale comprises 20 self-report items which participants rate on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 = ‘not at all’ to 4 = ‘extremely’. Scores are summed to produce an overall PTSD symptom severity score (Weathers et al., Citation2013). The PCL-5 has strong psychometric properties and has demonstrated high levels of convergent, discriminant and structural validity (Blevins et al., Citation2015).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) was used as a transdiagnostic measure of overall psychological distress. The HADS is a 14-item scale that comprises seven items assessing anxiety and depression. Participants rate each item on a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3 (where scale response options differ by question), with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity or impact. In this study, these scores were summed to provide a composite score which reflected the severity of overall psychological distress. The HADS has strong psychometric properties, with high internal consistency and validity (Djukanovic et al., Citation2017).

The Dimensions of Anger-5 (DAR-5) (Forbes et al., Citation2014) was used as a measure of anger symptomatology. The DAR-5 is a 5-item scale assessing anger experiences over the past 2 weeks. Participants rate each item on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = ‘none or almost none of the time’ to 5 = ‘all or almost all of the time’, where higher scores indicate greater problematic anger symptomatology or impact. Scores are summed to produce an overall score ranging from 5 to 25, where higher scores indicate greater symptomatology. The DAR-5 has demonstrated strong internal reliability, along with convergent, concurrent and discriminant validity against established measures (Forbes et al., Citation2014).

The Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Morin, Citation1993) was used as a measure of insomnia. The ISI is a 7-item scale that measures the severity of insomnia problems and their impact on daily functioning on a scale ranging from 0 to 4, where scale response options differ by question, with higher scores indicating greater severity and impact. Scores are summed to provide an overall severity score ranging from 0 to 28. The ISI has excellent internal consistency as well as convergent and discriminant validity with relevant clinical measures (Morin et al., Citation2011).

The recently developed 6-item Brief Adjustment Scale (BASE-6) (Cruz et al., Citation2020) was also included in questionnaires for exploratory purposes, as a new generic measure of psychological distress and potential outcome scale for transdiagnostic interventions. The scale comprises six items assessing psychological distress and related interference, scored on a seven-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 = ‘not at all’, 4 = ‘somewhat’, 7 = ‘extremely’. Scores are summed to form a total score ranging from 6 to 42, with higher scores indicating higher psychological distress. The BASE-6 has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, with high internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent validity (Ko et al., Citation2023). BASE-6 scale scores were not considered as outcome measures, and instead were used as missing data covariates in the substantive analyses (see below).

1.4. Coach recruitment, training and supervision

Thirty-three SOLAR coaches were recruited from communities impacted by the disasters. Coaches were either individual volunteers with an interest/prior experience in councelling, or employees of community services organisations who were working to support disaster-affected communities in regional and rural Victoria. Coaches were recruited and trained prior to recruiting participants to the study.

Coaches received training in the SOLAR protocol over a two-day training period and supervision over a 10 week period. Training and supervision were conducted by clinical psychologists on the research team. Training consisted of a modular training and support package, which comprised (i) Self-paced, online training to familiarise Coaches with programme content and materials (duration approximately 4 hours); (ii) Synchronous video conference training on how to deliver SOLAR (4 hours); (iii) Optional video conference training on core counselling skills (targeting individuals with no previous experience in counselling contexts; 2 hours); (iv) Optional video conference training on methods of identifying and engaging suitable participants for SOLAR (2 hours); and (v) Weekly group supervision (1 hour/week) by a registered psychologist within the research team with expertise in trauma and the SOLAR programme. After the video conference training, the coaches were directed to complete a short quiz in the online course to finalise the training course. SOLAR Coaches were not financially compensated for their time participating in the project.

1.5. Data analysis

Data file preparation and preliminary analyses were conducted in SPSS, while the substantive analyses used MPlus Version 8 and Program R Version 4.0.3. The former included examinations of item score distributions and missing data analyses, which initially comprised descriptive analyses of item-level missing data, as well as missing data due to study drop-out or survey non-response. Logistic regression models were estimated to quantify differential patterns of non-response according to factors including intervention condition and baseline (T1) measures of both primary and secondary outcome variables. Tests of the benefits of the SOLAR intervention were specified via a series of multigroup analyses in MPlus where the intervention condition (SOLAR versus control) was identified as the grouping factor, while post-intervention (T2) and follow-up (T3) measures of primary and secondary outcomes were specified as endogenous variables in separate analyses. For both groups, the baseline measures of relevant outcomes were included as covariates which thus identified models equivalent to Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA). However, the multiple-group approach was associated with advantages including the capacity to: (a) test and relax traditional ANCOVA assumptions of equality of error variances and regression coefficients for the covariate; and (b) utilise Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation to make use of all available data, consistent with intention-to-treat (ITT) principles. Scale scores for the BASE-6 were included as auxiliary variables and missing data covariates, consistent with Graham’s (Citation2003) saturated correlated approach.

Preliminary analyses involved a series of nested models that were specified for each outcome, and were all estimated using robust Maximum Likelihood (MLR). Appraisals of model fit involved the MLR χ2 test of exact fit. The preliminary model was equivalent to a traditional ANCOVA in which error variances and regression coefficients for the covariate were constrained to equivalence across groups, while intercepts were allowed to vary. Subsequent models then relaxed assumptions of equal error variances and regression coefficients, respectively, with relative improvements in fit tested using the Satorra-Bentler χ2 test. Once a best fitting model was identified as a baseline for each outcome (Model0), the substantive analyses comprised further comparisons involving alternative models (Model1) in which intercepts were constrained to equivalence across groups. Significant differences in fit indicated that constrained intercepts were characterized by reductions in model fit, and comprised the primary tests of intervention effects. Estimated sample statistics and effect size measures were produced to quantify the nature and magnitude of effects. These included Cohen's d for between-group comparisons which was calculated on the basis of estimated sample statistics, along with repeated measures effect size measures (dRM) which were calculated from complete case (paired) data for each group using the ‘effsize’ package (Torchiano Citation2020) in Program R.

1.6. Assumption testing and identification of baseline models

A series of preliminary multi-group models were estimated to screen for baseline differences in primary and secondary outcomes, and test traditional ANCOVA assumptions of homogeneity of regression slopes and error variances. Multi-group models initially tested the implications of constraining baseline scores to equivalence for each outcome, relative to models in which scores were freely estimated, and these identified no significant changes in model fit (suggesting no significant differences in baseline scores across groups). A subsequent series of models were then estimated for each outcome and time-point, and initially (1) constrained error variances and regression coefficients (for the covariate) to equivalence across groups, which was equivalent to a traditional ANCOVA (group intercepts were freely estimated). Comparison models then allowed (2) error variances and (3) regression coefficients to be freely estimated, and were compared with model (1) using the Satorra-Bentler χ2 test. Model tests for T2 scores indicated that the traditional ANCOVA model (1) provided exact fit to data for the HADS (χ2 = 0.02, df = 2, p = .990), PCL (χ2 = 4.20, df = 2, p = .123), and ISI (χ2 = 1.59, df = 2, p = .452), while subsequent models did not yield any significant improvements. Accordingly, these were accepted as the baseline models for subsequent hypotheses tests. In contrast, model (i) was not an exact fit to the data for the DAR at T2 (χ2 = 10.54, df = 2, p = .545), and an alternative model (2) in which error variances were freely estimated provided statistically significant improvements (χ2 = 0.57, df = 1, p = .449) and was accepted as the baseline. On the basis of model comparisons for the T3 scores, the traditional ANCOVA model was accepted as the baseline model for the HADS (χ2 = 0.46, df = 2, p = .796), DAR (χ2 = 1.94, df = 2, p = .379), and ISI (χ2 = 2.15, df = 2, p = .342), while an alternative model (2) with error variances that were freely estimated was accepted as the baseline for analyses of the PCL at T3 (χ2 = 0.57, df = 1, p = .449).

2. Results

2.1. Missing data analyses

From the total sample of n = 66 participants at baseline, there were 48 and 50 participants who completed outcome measures at post-intervention and follow-up respectively, and thus overall non-response rates of 27.3% and 24.2% across these time-points. Further logistic regression analyses indicated that there were no significant associations with non-response rates at T2 or T3 and socio-demographic characteristics including gender, age and education, as well as self-report measures of fire impact, drought impact, and pandemic impacts. All missing data were managed in the substantive analyses using FIML (including missing data covariates), which enable the utilisation of all available data and was thus consistent with principles of ITT analyses.

2.2. Demographics

Participant demographics for the full sample are presented below in .

Table 1. Summary of participant demographic characteristics.

2.3. Participant outcomes

2.3.1. Testing intervention effects

presents estimated sample statistics for both SOLAR and Self-Help conditions across time points, along with statistical tests of the relative benefits of the SOLAR programme at the T2 and T3 time points. These tests were also derived from multi-group analyses and comparisons across (A) baseline models (as identified above) in which intercepts were freely estimated, and (B) alternative models in which intercepts were constrained to equivalence. Accordingly, significant tests were derived from model comparisons and indicated that constraining intercepts (or group means) to equivalence was associated with reduced fit to the data, and thus provides evidence for differences between groups.

Table 2. Descriptive and model statistics for analysis of covariance (ANOVA) models comparing SOLAR and Self-Help conditions over time.

shows the results of comparisons across models of T2 scores which indicated that constraining intercepts to equivalence was associated with significant reductions in fit for all primary and secondary outcomes. These indicate significant post-intervention differences between the SOLAR and control conditions, when controlling for baseline scores, with Cohen's d effect size measures ranging from d = 0.44 (for the HADS) to 0.65 (for the PCL). In contrast, analyses of scores at T3 identified no significant difference between groups when controlling for baseline scores. Cohen's d effect size measures indicated mean differences that were small to moderate for the HADS and the PCL (d = 0.23–0.30), and were approaching zero for the DAR and ISI (d = 0.02–0.08). also displays repeated measures effect size estimates (dRM) that were produced for each group across adjacent time-points. These indicate that SOLAR condition demonstrated large overall improvements in psychological distress and posttraumatic stress symptoms from baseline to follow-up relative to medium/small effect sizes in the Self-Help condition.

3. Discussion

This is the first randomised controlled trial testing the efficacy of the SOLAR programme delivered to communities impacted by compounding disasters including wildfire, drought, and the COVID pandemic. Trained community members delivered the programme. Relative to Self-Help, participants in the SOLAR condition showed significantly greater improvements in distress symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, anger and sleep impairment. Participants in the SOLAR group did not return to pre-intervention levels of symptomatology at 2-month follow-up, and a small effect size difference between the intervention and control condition was maintained (although this between group difference at follow-up was no longer significant). There was a slight increase in symptoms across all measures from post intervention to the two-month point in the SOLAR condition. Incorporation of ‘booster sessions’ may prove useful to maintain intervention effects and is worthy of future investigation This may prove especially important in future scenarios in which significant disaster-related stressors persist over time.

The SOLAR intervention was associated with moderate between group effect sizes in alleviating mental health symptoms post treatment, which decreased to small effect sizes for the primary outcomes at follow-up. This aligns with previous pilot studies of the SOLAR intervention (Gibson et al., Citation2021; Lotzin et al., Citation2022) which found it was effective in addressing psychological distress and/or posttraumatic stress symptoms in a post-disaster or post-trauma setting. Other brief psychosocial interventions that adopt a task shifting approach have found similar results. For example, studies of the Problem Management Plus (PM+) (World Health Organization, Citation2016) intervention, a task-shifting intervention designed to address mental distress in low- and middle-income countries, have found moderate to large between group effect sizes (de Graaff et al., Citation2020). However, it is difficult to meaningfully compare the magnitude of between group effect sizes across studies given that the control condition between studies is different. The use of an active self-help control in our study (which was associated with modest but meaningful improvements across all time points) is different to the treatment as usual (de Graaff et al., Citation2020) or psychoeducation and/or referral to primary care provider (Jordans et al., Citation2021 Sijbrandij et al., Citation2016;) conditions that are characteristic of PM + studies.

Most studies investigating the use of task-shifting models of care in the psychiatry field have predominantly been run in low and middle-income countries. For example, PM + has been trialled among individuals from countries including Kenya, Pakistan, Syria, and Jordan (Acarturk et al., Citation2022; Akhtar et al., Citation2020; de Graaff et al., Citation2023 Rahman et al., Citation2016; Sijbrandij et al., Citation2016; Uygun et al., Citation2020;), but less so in high-income countries. Meta-analytic evidence has suggested that treatment effect sizes in randomised control trials in low to middle-income countries are significantly higher relative to those in high-income countries; which may be partially attributed to differences in baseline risk and limited access to healthcare and mental health resources generally (Panagiotou et al., Citation2013). Our trial is among the first to evaluate a task-shifting model of post-disaster mental health care in a high-income country, and as such the moderate effect sizes are a promising indication that the SOLAR intervention is effective in this context. In post-disaster settings, where timely access to mental health professionals for all disaster-affected individuals is not feasible even in high-income countries, the SOLAR intervention may provide one important way of increasing the accessibility of effective care.

The SOLAR programme has been delivered at different time intervals post disaster and has been shown to be efficacious at each time point. Gibson et al. (Citation2021) found SOLAR to be efficacious at three years post-cyclone; Lotzin et al. (Citation2022) delivered the intervention to a sample of trauma survivors where time since trauma ranged from months to years; while in this current study, we delivered SOLAR approximately one year after wildfires, but during the extended COVID-19 lockdowns that occurred in Victoria, Australia. Key to the question of when to deliver SOLAR is the recognition that initial needs such as shelter and safety need to be met before disaster survivors are ‘ready’ to address their emotional health, consistent with principles of Psychological First Aid (Vernberg et al., Citation2008).

These results should be considered alongside the following limitations. Difficulties in recruiting participants during the COVID-19-related lockdowns, owing to movement restrictions preventing travel and visitation to disaster-affected communities, meant that the study sample size was relatively small. Although the final sample size was close to the original target (n = 80), this may impact the external validity of findings. Additionally, it should be noted that the control treatment condition (Self-Help) employed in this study was an active control, and there was large overlap in the content that was covered across interventions. Self-help information is often provided after disaster and it was interesting to note that it did seem to improve symptoms. It should be noted that this study did not directly measure the severity of disaster exposure to control for this factor at intake – however, none of the mental health symptom severity measures differed between groups at intake, suggesting that the mental health impacts of the disaster were similar between groups after randomisation. Additionally, the majority of the sample in the present study was female, and while this is characteristic of community trauma studies more broadly (Olff et al., Citation2007), it is unclear how these findings might generalise to male dominant populations. There were different completion and follow-up rates between conditions and the degree to which this impacted on findings is not known. Specifically, treatment completion was slightly lower for the SOLAR condition (81%) relative to the Self-Help (97%) condition – and the rates of questionnaire completion was slightly lower for SOLAR (67%) relative to control (85%). Finally, the study aimed to build up capacity to deliver the SOLAR intervention on an ongoing basis beyond the initial trial, such that there is a sizeable workforce of coaches in the community who are able to implement the SOLAR intervention as part of their arsenal in future. As such, the ratio of coaches to participants in the study was relatively high. However, in practice ‘to scale’, community coaches would be able to deliver the intervention to greater numbers of participants.

This is the first randomised controlled trial to test the efficacy of a task shifting programme that aimed to improve mental health and wellbeing following compound disaster in a high-income country. As climate change sees an escalation in the intensity and frequency of disasters, it is important to build evidence to support these models. Early interventions like the SOLAR programme help communities rebuild after disaster, and could potentially increase the resilience of communities to respond to future disasters.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the SOLAR coaches who volunteered their time to train as a SOLAR coach and deliver the SOLAR programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the research.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acarturk, C., Uygun, E., Ilkkursun, Z., Yurtbakan, T., Kurt, G., Adam-Troian, J., Senay, I., Bryant, R., Cuijpers, P., Kiselev, N., McDaid, D., Morina, N., Nisanci, Z., Park, A. L., Sijbrandij, M., Ventevogel, P., Fuhr, D. C. (2022). Group problem management plus (PM+) to decrease psychological distress among Syrian refugees in Turkey: a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03645-w

- Akhtar, A., Giardinelli, L., Bawaneh, A., Awwad, M., Naser, H., Whitney, C., Jordans, M.J., Sijbrandij, M., Bryant, R.A. and STRENGTHS Consortium, (2020). Group problem management plus (gPM+) in the treatment of common mental disorders in Syrian refugees in a Jordanian camp: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7969-5

- Banholzer, S., Kossin, J., & Donner, S. (2014). The impact of climate change on natural disasters. In: Singh, A., & Zommers, Z. (eds.), Reducing disaster: Early warning systems for climate change, 21–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-8598-3_2

- Beaglehole, B., Mulder, R. T., Frampton, C. M., Boden, J. M., Newton-Howes, G., & Bell, C. J. (2018). Psychological distress and psychiatric disorder after natural disasters: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(6), 716–722. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.210

- Berkowitz, S., Bryant, R., Brymer, M., Hamblen, J., Jacobs, A., Layne, C. and Watson, P. (2010). Skills for psychological recovery: Field operations guide. The National Center for PTSD & the National Child Traumatic Stress Network.

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of traumatic stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Cianconi, P., Betrò, S., & Janiri, L. (2020). The impact of climate change on mental health: a systematic descriptive review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11(74), 21–49.

- Cowlishaw, S., Metcalf, O., Varker, T., Stone, C., Molyneaux, R., Gibbs, L., Block, K., Harms, L., MacDougall, C., Gallagher, H. C., Bryant, R., Lawrence-Wood, E., Kellett, C., O'Donnell, M., & Forbes, D. (2021). Anger dimensions and mental health following a disaster: Distribution and implications after a major bushfire. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 34(1), 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22616

- Cowlishaw, S., O’Dwyer, C., Bowd, C., Forbes, D., O’Donnell, M. L., & Howard, A. (2022). Pandemic impacts and experiences after disaster: A compound disaster perspective. Final report produced for the National Mental Health Commission: Phoenix Australia – Centre for Posttraumatic Mental Health: Melbourne.

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008) Developing and evaluating complex interventions: new guidance. Retrieved from the Medical Research Council website: https://mrcukriorg/documents/pdf/complex-interventions-guidance/.

- Cruz, R. A., Peterson, A. P., Fagan, C., Black, W., & Cooper, L. (2020). Evaluation of the Brief Adjustment Scale–6 (BASE-6): A measure of general psychological adjustment for measurement-based care. Psychological Services, 17(3), 332–342. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000366

- de Graaff, A.M., Cuijpers, P., McDaid, D., Park, A., Woodward, A., Bryant, R.A., Fuhr, D.C., Kieft, B., Minkenberg, E. and Sijbrandij, M. (2020). Peer-provided Problem Management Plus (PM+) for adult Syrian refugees: a pilot randomised controlled trial on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29(e162), 1–24.

- de Graaff, A. M., Cuijpers, P., Twisk, J. W. R., Kieft, B., Hunaidy, S., Elsawy, M., Gorgis, N., Bouman, T. K., Lommen, M. J. J., Acarturk, C., Bryant, R., Burchert, S., Dawson, K. S., Fuhr, D. C., Hansen, P., Jordans, M., Knaevelsrud, C., McDaid, D., Morina, N., … Sijbrandij, M. (2023). Peer-provided psychological intervention for Syrian refugees: results of a randomised controlled trial on the effectiveness of Problem Management Plus. BMJ Ment Health, 26(1), e300637. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjment-2022-300637

- Djukanovic, I., Carlsson, J., & Årestedt, K. (2017). Is the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) a valid measure in a general population 65–80 years old? A psychometric evaluation study. Health and quality of life outcomes, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0759-9

- Forbes, D., Alkemade, N., Hopcraft, D., Hawthorne, G., O’Halloran, P., Elhai, J. D., McHugh, T., Bates, G., Novaco, R. W., Bryant, R., & Lewis, V. (2014). Evaluation of the Dimensions of Anger Reactions-5 (DAR-5) Scale in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 830–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.015

- Gibson, K., Barnett, J., Haslam, N., & Kaplan, I. (2020). The mental health impacts of climate change: Findings from a Pacific Island atoll nation. Journal of anxiety disorders, 73, 102237.

- Gibson, K., Little, J., Cowlishaw, S., Ipitoa Toromon, T., Forbes, D., & O’Donnell, M. (2021). Piloting a scalable, post-trauma psychosocial intervention in Tuvalu: the Skills for Life Adjustment and Resilience (SOLAR) program. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1948253. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1948253

- Graham, J. W. (2003). Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_4

- Hermosilla, S., Forthal, S., Sadowska, K., Magill, E. B., Watson, P., & Pike, K. M. (2023). We need to build the evidence: A systematic review of psychological first aid on mental health and well-being. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 36(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22888

- Johnson, S. U., Ulvenes, P. G., Øktedalen, T., & Hoffart, A. (2019). Psychometric properties of the general anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1713. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01713

- Jordans, M. J. D., Kohrt, B. A., Sangraula, M., Turner, E. L., Wang, X., Shrestha, P., Ghimire, R., van’t Hof, E., Bryant, R. A., Dawson, K. S., Marahatta, K., Luitel, N. P., & van Ommeren, M. (2021). Effectiveness of Group Problem Management Plus, a brief psychological intervention for adults affected by humanitarian disasters in Nepal: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS Medicine, 18(6), e1003621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003621

- Ko, H., Shin, J., & Cooper, L. D. (2023). Brief Adjustment Scale–6 for Measurement-Based Care: Psychometric Properties, Measurement Invariance, and Clinical Utility. Assessment, 30(5), 1623–1639. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221115144

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- Leppold, C., Gibbs, L., Block, K., Reifels, L., & Quinn, P. (2022). Public health implications of multiple disaster exposures. The Lancet Public Health, 7(3), e274–e286.

- Lotzin, A., Hinrichsen, I., Kenntemich, L., Freyberg, R.-C., Lau, W., & O’Donnell, M. (2022). The SOLAR group program to promote recovery after disaster and trauma—A randomized controlled feasibility trial among German trauma survivors. Psychological trauma: theory, research, practice, and policy, 14(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001105

- Morin, C. M. (1993). Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. Guilford Press.

- Morin, C. M., Belleville, G., Bélanger, L., & Ivers, H. (2011). The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep, 34(5), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/34.5.601

- National Mental Health Commission. (2022). National disaster mental health and wellbeing framework. Australia.

- O'Donnell, M.L., Lau, W., Fredrickson, J., Gibson, K., Bryant, R.A., Bisson, J., Burke, S., Busuttil, W., Coghlan, A., Creamer, M. and Gray, D. (2020). An open label pilot study of a brief psychosocial intervention for disaster and trauma survivors. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11(483), 1–12.

- Olff, M., Langeland, W., Draijer, N., & Gersons, B. P. (2007). Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological bulletin, 133(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183

- Palinkas, L. A., & Wong, M. (2020). Global climate change and mental health. Current opinion in psychology, 32, 12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023

- Panagiotou, O. A., Contopoulos-Ioannidis, D. G., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2013). Comparative effect sizes in randomised trials from less developed and more developed countries: meta-epidemiological assessment. Bmj, 346, f707. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f707

- Pearson, A. R., White, K. E., Nogueira, L. M., Lewis, N. A., Green, D. J., Schuldt, J. P., & Edmondson, D. (2023). Climate change and health equity: A research agenda for psychological science. American Psychologist, 78(2), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001074

- Rahman, A., Riaz, N., Dawson, K.S., Hamdani, S.U., Chiumento, A., Sijbrandij, M., Minhas, F., Bryant, R.A., Saeed, K., van Ommeren, M. and Farooq, S. (2016). Problem Management Plus (PM+): Pilot trial of a WHO transdiagnostic psychological intervention in conflict-affected Pakistan. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 182–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20312

- Schäfer, S. K., Kunzler, A. M., Lindner, S., Broll, J., Stoll, M., Stoffers-Winterling, J., & Lieb, K. (2023). Transdiagnostic psychosocial interventions to promote mental health in forcibly displaced persons: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2196762. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2023.2196762

- Sijbrandij, M., Bryant, R.A., Schafer, A., Dawson, K.S., Anjuri, D., Ndogoni, L., Ulate, J., Hamdani, S.U. and Van Ommeren, M. (2016). Problem Management Plus (PM+) in the treatment of common mental disorders in women affected by gender-based violence and urban adversity in Kenya; study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. International journal of mental health systems, 10(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0075-5

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Torchiano, M. (2020). Package ‘effsize’: Efficient Effect Size Computation. Available from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=effsize.

- Uygun, E., Ilkkursun, Z., Sijbrandij, M., Aker, A.T., Bryant, R., Cuijpers, P., Fuhr, D.C., De Graaff, A.M., De Jong, J., McDaid, D. and Morina, N. (2020). Protocol for a randomized controlled trial: peer-to-peer Group Problem Management Plus (PM+) for adult Syrian refugees in Turkey. Trials, 21(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-4166-x

- Vernberg, E. M., Steinberg, A. M., Jacobs, A. K., Brymer, M. J., Watson, P. J., Osofsky, J. D., Layne, C. M., Pynoos, R. S., & Ruzek, J. I. (2008). Innovations in disaster mental health: Psychological first aid. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(4), 381. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012663

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013) The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov.

- World Health Organization. (2008). Task shifting: Global recommendations and guidelines. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2016) Problem Management Plus (PM+): Individual psychological help for adults impaired by distress in communities exposed to adversity: World Health Organization.

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x