ABSTRACT

Background: During peacekeeping missions, military personnel may be involved in or exposed to potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs), such as an inability to intervene due to a limited mandate. While exposure to such morally transgressive events has been shown to lead to moral injury in combat veterans, research on moral injury in peacekeepers is limited.

Objective: We aimed to determine patterns of exposure to PMIEs and associated outcome- and exposure-related factors among Dutch peacekeepers stationed in the former Yugoslavia during the Srebrenica genocide.

Method: Self-report data were collected among Dutchbat III veterans (N = 431). We used Latent Class Analysis to identify subgroups of PMIE exposure as assessed by the Moral Injury Scale–Military version. We investigated whether deployment location, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), posttraumatic growth, resilience, and quality of life differentiated between latent classes.

Results: The analysis identified a three-class solution: a high exposure class (n = 79), a moderate exposure class (n = 261), and a betrayal and powerlessness-only class (n = 135). More PMIE exposure was associated with deployment location and higher odds of having probable PTSD. PMIE exposure was not associated with posttraumatic growth. Resilience and quality of life were excluded from analyses due to high correlations with PTSD.

Conclusions: Peacekeepers may experience varying levels of PMIE exposure, with more exposure being associated with worse outcomes 25 years later. Although no causal relationship may be assumed, the results emphasize the importance of better understanding PMIEs within peacekeeping.

HIGHLIGHTS

Peacekeeping veterans reported different patterns of exposure to potentially morally injurious experiences: high exposure, moderate exposure, or experiences of betrayal and powerlessness only.

Deployment location predicted the pattern of exposure.

More exposure was associated with worse psychological outcomes 25 years later.

Antecedentes: Durante las misiones de mantenimiento de la paz, el personal militar puede verse implicado o expuesto a experiencias potencialmente dañinas para la moral (PMIE), como la imposibilidad de intervenir debido a un mandato limitado. Aunque se ha demostrado que la exposición a este tipo de sucesos moralmente transgresores provoca daños morales en los veteranos de combate, la investigación sobre los daños morales en el personal de mantenimiento de la paz es limitada.

Objetivo: Se pretendía determinar los patrones de exposición a los PMIE y los factores asociados relacionados con los resultados y la exposición entre las fuerzas de paz holandesas destinadas en la ex Yugoslavia durante el genocidio de Srebrenica.

Método: Se recopilaron datos de autoinforme entre veteranos del Dutchbat III (N = 431). Se utilizó el análisis de clases latentes para identificar subgrupos de exposición a PMIE según la evaluación de la Escala de Daño Moral-Versión Militar. Se investigó si el lugar de despliegue, el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), el crecimiento postraumático, la resiliencia y la calidad de vida diferenciaban entre clases latentes.

Resultados: El análisis identificó una solución de tres clases: una clase de alta exposición (n = 79), una clase de exposición moderada (n = 261) y una clase de traición e impotencia solamente (n = 135). Una mayor exposición a PMIE se asoció con el lugar de despliegue y con mayores probabilidades de padecer un probable TEPT. La exposición al PMIE no se asoció con el crecimiento postraumático. La resiliencia y la calidad de vida se excluyeron de los análisis debido a las altas correlaciones con TEPT.

Conclusiones: Las fuerzas de paz pueden experimentar distintos niveles de exposición a PMIE, y una mayor exposición se asocia a peores resultados 25 años después. Aunque no se puede asumir ninguna relación causal, los resultados subrayan la importancia de comprender mejor las PMIE dentro del mantenimiento de la paz.

1. Introduction

1.1. Morally injurious experiences in military peacekeepers

Since its establishment after World War II, the United Nations have employed 71 peacekeeping operations (see peacekeeping.un.org). Apart from helping countries to maintain peace and security, peacekeeping operations aim at achieving a range of other objectives including the protection of civilians, disarmament of former combatants, the organization of elections, and the promotion of human rights. Peacekeeping operations are guided by the principles of consent of all parties, impartiality, and the non-use of force except in self-defense and defense of the mandate (United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Citation2008). While peacekeeping operations may be highly effective, the United Nations increasingly recognize that operations may be challenged by the absence of political solutions, a lack of focus of mission mandates, complex threats leading to casualties, and lack of personnel and equipment (see peacekeeping.un.org).

The challenges involved in peacekeeping may prove morally burdening for those deployed (Dallaire & Beardsley, Citation2003; Shigemura & Nomura, Citation2002). For example, the limited mandate and lack of resources associated with peacekeeping missions may lead to painful moral dilemmas where on the one hand peacekeepers may wish to intervene, but on the other hand they may not be allowed to or may not have the necessary resources to be successful. In several instances, this limited power meant peacekeepers were unable to stop tragedies from taking place – the Rwanda and Srebrenica genocides being well-known examples (Klep, Citation2008).

For peacekeepers, such tragic events may amount to potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIEs). PMIEs may involve acts by self and others, including active perpetration, failure to prevent such perpetrations, as well as bearing witness to or falling victim to perpetrations (Litz et al., Citation2009). Examples of involvement in such events by peacekeepers include making cruel jokes about civilians due to feeling morally overwhelmed, and being forced to choose between providing medical aid to a wounded child or a wounded soldier (Molendijk, Citation2018). PMIEs can also concern the betrayal of ‘what’s right’ by authority figures (Shay, Citation2014), which peacekeepers may experience when they are restricted from engaging in combat and are thereby unable to prevent loss of civilian life (Dallaire & Beardsley, Citation2003). The long-lasting psychological, social, spiritual, and behavioural impact of such experiences is known as moral injury (MI; Litz et al., Citation2009).

1.2. PMIE exposure and mental health

A growing body of research suggests that PMIE exposure is associated with mental health problems. A meta-analysis by Williamson et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated PMIE exposure to be reliably associated with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013), depression, and suicidality. Other studies also found associations between PMIE exposure and anxiety, substance use, lower work/social functioning, and painful moral emotions such as anger, guilt and shame (Currier et al., Citation2015; Lancaster & Harris, Citation2018; Maguen et al., Citation2021; Nash et al., Citation2013).

Among veterans, the type and extent of exposure to PMIEs may differ, and different (patterns of) PMIEs may be associated with different outcomes. Several recent studies therefore examined patterns of PMIEs and their subsequent impact using the person-centred method known as Latent Class Analysis (LCA). This method discerns latent subgroups in the data – in this case, co-occurring PMIEs – and enables the comparison of these groups with other variables. Zerach et al. (Citation2021), for example, conducted an LCA among Israeli veterans and found three subgroups reporting different patterns of PMIE exposure: one group had predominantly experienced PMIEs for which they held themselves responsible, another group reported betrayal-related PMIEs, and the last group experienced few PMIEs at all. Another LCA among US veterans (Saba et al., Citation2022) found four subgroups, of which two had experienced high and moderate PMIE exposure and two reported specific PMIE types (having witnessed transgressions and having been troubled by a failure to act). In both studies, the subgroups differed with respect to symptoms of PTSD and depression (Saba et al., Citation2022; Zerach et al., Citation2021), guilt (Zerach et al., Citation2021), and anxiety and anger (Saba et al., Citation2022).

1.3. PMIE exposure and salutogenic factors

However, PMIE exposure may also have a more positive impact. Posttraumatic growth (PTG) is the transformational process through which dealing with trauma can create positive changes, such as a greater appreciation for life and an enhanced sense of spirituality (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004). Evans et al. (Citation2018) found that among US veterans, their own moral violations were significantly associated with greater PTG, while overall PMIE exposure was not. Hijazi et al. (Citation2015) similarly found that veterans who had a greater perception of moral wrongdoing displayed greater PTG.

Another salutogenic construct that may be associated with PMIE exposure is resilience. Resilience is conceptualized as the process through which an individual maintains a mental and physical equilibrium after experiencing an adverse event (Bonanno, Citation2004). The association between PMIE exposure and psychological resilience has, thus far, not been studied in veteran samples. In studies of healthcare professionals (Fitzpatrick et al., Citation2022; Rushton et al., Citation2022) and veterinarians (Crane et al., Citation2015), PMIE exposure and moral injury symptoms were found to be negatively associated with resilience.

Lastly, PMIE exposure may be related to quality of life (QoL). In a latent profile analysis of PTSD and moral injury-related outcomes, PMIE exposure was found to increase the odds of being in a ‘potential moral injury’ class and having a lower QoL (Smigelsky et al., Citation2019). However, Evans et al. (Citation2018) found moral violations by the self to be predictive of higher life satisfaction (one aspect of QoL).

1.4. Current study

While research points to differences in PMIE exposure and consequent psychosocial functioning among military veterans, little research exists on PMIE exposure and associated outcomes among veterans of peacekeeping missions. Yet peacekeepers commonly witness extreme human distress and suffer from feelings of powerlessness and shame when they are unable to intervene (Dirkzwager et al., Citation2005; Molendijk, Citation2021; Rietveld, Citation2009; Shigemura & Nomura, Citation2002). It has been posited that when PMIEs elicit an empathic response on which someone cannot act (e.g. being unable to help in the face of suffering), this increases the odds of developing moral injury (Ter Heide, Citation2020).

To obtain insight into PMIE exposure and its consequences among peacekeeping veterans, we conducted an LCA of PMIEs among Dutch peacekeepers that were part of Dutchbat III. This battalion was stationed in the former Yugoslavia between January 6, 1995 and July 14, 1995, as part of the United Nations Protection Force peacekeeping mission during the Bosnian War. The battalion was tasked with carrying out United Nations Security Council resolution 819, which designated the town of Srebrenica and its surroundings as a civilian ‘safe area’, to be ‘free from any armed attack or any other hostile act’ (United Nations Security Council, Citation1993). Under the UN mandate, Dutchbat III was only permitted to use force in self-defense. In July 1995, Bosnian Serb forces captured the enclave, displacing many of its inhabitants and leading many to seek refuge in the Dutch compound. These forces then took away and killed over 8,000 Bosnian Muslim boys and men. This event, now known as the Srebrenica genocide, caused great outcry in the Netherlands, where Dutchbat III, the UN, and the Dutch government were strongly condemned for failing to protect the local Muslim population (Molendijk, Citation2021). Research suggests that many Dutchbat III veterans experience a lasting negative impact from their deployment, the genocide, and the subsequent societal condemnation (Olff et al., Citation2020). Moreover, during the mission, all types of PMIEs (acts of commission, acts of omission, and betrayal) took place (Molendijk, Citation2021).

Our aim was to investigate if we could find distinct patterns of PMIE exposure among Dutch peacekeepers, and whether these patterns could be predicted by location at the fall of Srebrenica, as a proxy measure of exposure to human distress. Additionally, we explored the association of PMIE patterns with different psychological outcomes with regards to PTSD, PTG, resilience, and QoL. Identifying distinct PMIE patterns and associated outcomes helps replicate prior studies, contributes to knowledge about (the impact of) PMIE exposure among peacekeepers, and allows treatments for this group to be adjusted accordingly.

Based on prior findings, we hypothesized that we would find PMIE patterns characterized by various levels of PMIE exposure (e.g. low, moderate, and high) and/or marked by specific PMIEs types. In addition, we hypothesized that veterans who were at the fall of Srebrenica would have higher PMIE exposure. We further expected different constellations of PMIE exposure to be differentially associated with PTSD symptom severity, PTG, resilience, and QoL.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

This study concerns a secondary analysis of data collected for a mixed-method study into the wellbeing of Dutchbat III veterans (Olff et al., Citation2020) commissioned by the Dutch Ministry of Defense (MoD). The reason for commissioning the study was the observation that some Dutchbat III veterans still experienced problems as a result of the mission. The study was carried out by ARQ National Psychotrauma Center, a Dutch national institute for research, policy, diagnostics and treatment of complex psychotrauma. Included in the study were active duty and post-active Dutchbat III veterans. Data were collected between October and December 2019. The medical committee of the Amsterdam Academic Medical Center evaluated the quantitative part of the study as exempt from ethical approval under the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO; W19_208 # 19.285). A Privacy Impact Assessment was also carried out.

2.2. Procedure

To reach the active duty veterans, the MoD shared contact details of veterans residing in the Netherlands. To contact active duty veterans residing outside of the Netherlands, the MoD sent an email invitation to participate in the study, while several veteran organizations disseminated information online. In October 2019, letters were sent to all Dutchbat III veterans in the Netherlands (N = 748) to inform them of the study. One week later, these veterans received a personalized invitation to participate, alongside the informed consent form and questionnaires (on paper), and a return envelope. Participants could also fill out the questionnaires online. After two and four weeks, non-respondents received a letter to remind them of the study. There was a designated contact point for questions and assistance in filling out the questionnaires.

Fifteen active and post-active veterans, residing abroad, responded and received the questionnaires as well; as a result, a total of 763 veterans received the questionnaires. All questionnaires filled out before January 2020 were included in the study, resulting in a total sample of 431 participants (56%). As shown in , participants were almost exclusively male. The average age was 53.78 (SD = 7.12). Of the total sample, just over half were at the enclave when it fell; the rest was elsewhere (i.e. another location in the former Yugoslavia or on leave outside the country).

Table 1. Participant characteristics (N = 431).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Moral injury questionnaire – military version (MIQ-M; Currier et al., Citation2015)

The MIQ-M is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that assesses PMIEs. It consists of 14 ‘event items’ (e.g. I saw / was involved in the death(s) of an innocent in the war), as well as six ‘effect items’ (e.g. I feel guilt over failing to save the life of someone in the war). Items are rated on a four-point scale indicating PMIE frequency: never, seldom, sometimes, or often (sum score range 0-80). The MIQ-M has good psychometric properties (Currier et al., Citation2015). The instrument was translated to Dutch for the original data collection and specifically referred to experiences during the Dutchbat III mission.

2.3.2. PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., Citation2015)

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report instrument for PTSD symptoms according to the DSM-5. The severity of symptoms in the previous month is rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The current study used a summed symptom severity score, ranging between 0 and 80. We used a threshold score of 33 as an indication of probable PTSD according to the DSM-5 (Bovin et al., Citation2016). The Dutch translation of the PCL-5 has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Van Praag et al., Citation2020). Cronbach's alpha in the current study was α = .98. In this study, the PCL-5 did not specifically refer to the Dutchbat III mission but after the last item respondents were asked to indicate whether they felt that any symptoms were related to the mission.

2.3.3. Posttraumatic growth inventory (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1996)

We used the PTGI to measure positive changes as a result of the Dutchbat III mission. The PTGI consists of 21 items and five subscales. The total scale was used as an indicator of overall PTG. Items are rated on a six-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (did not experience this) to 5 (experienced this to a great degree). Summed scores were used, ranging 0–105; higher scores indicate more positive changes. The Dutch translation of the PTGI is psychometrically sound (Jaarsma et al., Citation2006). Internal consistency in this study was high, α = .93.

2.3.4. Resilience evaluation scale (RES; Van der Meer et al., Citation2018)

We measured general psychological resilience using the RES. The RES consists of nine items that are rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). This study used summed scores whereby higher scores indicate greater resilience (range 9–45). The RES displays good psychometric properties (Van der Meer et al., Citation2018). Internal consistency in this study was high, α = .94.

2.3.5. Manchester short assessment of quality of life (MANSA; Priebe et al., Citation1999)

The MANSA comprises 12 items which measure current quality of life, scored on a seven-point satisfaction scale ranging from 1 (cannot be worse) to 7 (cannot be better). We used summed scores ranging 12–84; higher scores indicate higher satisfaction with various aspects of one’s life. The Dutch translation of the MANSA is psychometrically sound (Van Nieuwenhuizen et al., Citation2017). Cronbach's alpha in the current sample was α = .94.

2.4. Data analysis

We conducted Latent Class Analysis in Mplus (version 8.6, Muthén and Muthén, Citation1998–2017) to identify subgroups that displayed similar patterns of PMIE exposure. For missing data, full information maximum likelihood estimation was applied. We tested models with one to six classes and compared indices of model fit to identify the most accurate model with the least number of latent classes. Classes were added until classes became too small (<10% of the total sample) and fit measures suggested a diminishing gain in model fit. We also considered the theoretical interpretation and clinical relevance of each model. To avoid local likelihood maxima, we requested 5000 random sets of starting values in the first step and 200 in the second step of optimization, as well as 500 initial stage iterations. To avoid local likelihood maxima for the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT), we used 500 bootstrap samples with 50 sets of starting values in the first and 20 sets in the second step of optimization.

To assess model fit, we evaluated the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the BLRT, and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR-LRT). Lower values of the BIC indicate better fit, while for the BLRT and LMR-LRT, a significant p-value indicates that the model with the added class improves the fit of the model (Nylund et al., Citation2007). We also examined the entropy values and average latent class probabilities; models with entropy values and average latent class assignment probabilities closer to 1.00 indicate higher classification accuracy (Geiser, Citation2013). Classification accuracy is considered acceptable when entropy values are >0.80 (Celeux & Soromenho, Citation1996).

Although it is common to dichotomize item responses to enhance the interpretability of LCA results, this proved challenging for the MIQ-M due to the different ways of interpreting the item response seldom for event and effect items. In the case of event items, seldom indicates someone experienced a PMIE at least once (i.e. the presence of a PMIE). However, for effect items, seldom indicates the near absence of a PMIE’s impact. We therefore first ran an LCA for one to six classes without dichotomized item responses. Because the item response often was endorsed infrequently, we merged the answers sometimes and often into one answer category (in a similar approach to Eid et al., Citation2003). For the optimal class solution, the answer category seldom was found to have low conditional response probabilities for most items, suggesting it had little differentiating power. For easier interpretability and reporting of results, we therefore decided to test models with one to six classes with dichotomized answer responses, but with different dichotomies for event and effect items. Item responses for event items were dichotomized to indicate whether someone had had an experience at least once (1; rated as having occurred seldom, sometimes or often) or not at all (0; rated as having occurred never). Item responses for effect items, on the other hand, were dichotomized to reflect whether someone considered the impact of a PMIE to be considerable (1; rated as occurring sometimes or often) or low (0; rated as occurring never or seldom).

To be exhaustive, we present model fit statistics for the LCA with three answer categories in Supplement 1. Regardless of the number of answer categories (three versus two), model fit measures (the BIC and LMR-LRT) favoured the same optimal class solution (see Supplement 1). We investigated conditional response probabilities per class to label the latent classes. We also inspected the different class solutions in item probability plots. Our chosen label for each latent class was the same for both the LCA with two and three answer categories.

Subsequently, we used the three-step method to study associations between class membership and location at the fall of the enclave, PTSD symptom severity, PTG, resilience, and QoL (Asparouhov & Muthén, Citation2014). The three-step method calculates a multinomial logistic regression with class membership as the dependent variable and the other variables as predictors of latent subgroup membership. The three-step approach does not allow for full information maximum likelihood estimation and handles missing data by listwise deletion. As a result, data from 28 participants were excluded from the analysis. Item responses to ‘location at the fall of Srebrenica’ were dichotomized to reflect whether participants were (1) or were not (0) present when the enclave fell.

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analysis

We first examined missing data and variable frequency distributions in SPSS (version 27). Full MIQ-M data were available for 398 participants (92.3%). We deleted one participant for whom most MIQ-M responses and all other questionnaire items were missing. Additionally, we deleted MIQ-M items 13 and 17 from subsequent analyses due to low item endorsement frequencies: 427 participants (99.4%) said to never have experienced item 13 (experiencing sexual abuse) and 425 participants (98.9%) said to never have experienced item 17 (unnecessarily destroying civilian property; see Supplement 2). Low item endorsement frequencies are unlikely to differentiate between subgroups and likely to result in convergency issues in LCA, and are thus best removed from the analysis (Geiser, Citation2013).

3.2. Descriptives

presents mean scores and bivariate correlations. All but four veterans (99.1% of the sample) endorsed at least one PMIE. The average PMIE score was 14.09 (SD = 9.25). PMIE exposure was positively correlated with PTSD symptom severity, lower QoL, and location, and negatively correlated with resilience. The average PTSD score was 18.5 (SD = 20.09), with 106 (24.7%) participants meeting the cut-off score of 33 for probable PTSD. Of all the respondents who replied ‘no’ to mission-relatedness of their PTSD symptoms, 153 (100%) had no probable PTSD diagnosis; of the respondents who replied ‘yes’ 53 (38.4%) had no probable PTSD diagnosis; and of those said who replied ‘I don’t know’ 105 (83.3%) had no probable PTSD diagnosis. In other words: those who felt that their current symptoms were related to the mission were more likely to have a probable PTSD diagnosis than those who felt that their symptoms were unrelated or were not sure, and vice versa, those with a probable PTSD diagnosis were more likely to feel that their symptoms were related to the mission than those without a probable PTSD diagnosis (p < .001).

Table 2. Mean scores and bivariate associations for the study variables.

3.3. Latent class analysis

summarizes model fit indicators for the LCA with one to six classes for the MIQ-M with dichotomized answers. As displayed in , the BIC favoured a three-class solution; the BLRT was significant for all six classes; and the LMR-LRT yielded a significant p-value for two, three and five classes, but not four and six. Inspection of the item probability plots and conditional response probabilities revealed that the three-class solution consisted of subgroups characterized by different levels of PMIE exposure; the four-class solution split one subgroup into two smaller but minimally different subgroups; and the five-class solution similarly divided another subgroup into two less-readily interpretable subgroups. Conceptually, we thus preferred the three-class solution over the other two. The entropy value also favoured the three-class model, which showed good classification quality. Average latent class assignment probabilities supported the three-class solution too, with values of .90, .90, and .92 for the first, second, and third latent class respectively. In conclusion, we deemed the three-class solution to be the most optimal, parsimonious, and clinically meaningful model.

Table 3. Model fit statistics for the latent class analysis of PMIE exposure (N = 430).

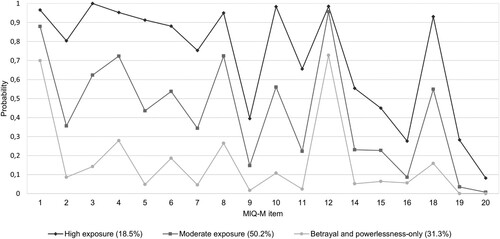

shows the plot with item probabilities for the three-class solution. Notably, all three subgroups displayed high probabilities of endorsing items 1 (things I saw / experienced in the war left me feeling betrayed or let-down by military / political leaders) and 12 (I experienced tragic warzone events that were chaotic and beyond my control), indicative of most participants having had these experiences. All subgroups demonstrated relatively low probabilities of endorsing items 9, 15, 16, 19, and 20, due to few participants having experienced these PMIEs (see Supplement 2). Other items were characterized by different levels of exposure per latent subgroup. We therefore labelled class 1 ‘high exposure’ (n = 79; 18.5%), class 2 ‘moderate exposure’ (n = 216; 50.2%), and class 3 ‘betrayal and powerlessness only’ (n = 135; 31.3%), as this latent subgroup was characterized by low endorsement of most items except for items 1 and 12.

3.4. Predictors of class membership

Means and standard deviations of the predictor variables are presented in . The mean PTSD total symptom severity score for those in the high exposure class was above the threshold score of 33 for probable PTSD. The high exposure class also reported the lowest mean scores for resilience and QoL. As can be seen in , QoL highly overlapped with both PTSD symptom severity (−.80) and resilience (.67), and resilience highly overlapped with PTSD symptom severity (−.67), indicating a high degree of multicollinearity among these predictors. In the multinomial regression model, in which the predictors PTSD symptom severity, PTG, QoL, resilience, and location were simultaneously regressed on the latent class variable, this resulted in issues concerning unstable regression coefficients. Such issues are common in regression models with a high degree of multicollinearity among predictors (Bowerman & O'Connell, Citation1990; Field, Citation2018). We therefore decided to remove QoL and resilience from the multinomial logistic regression. We then regressed PTSD symptom severity, PTG, and location on the latent class variable. presents the results of the multinomial logistic regression analysis. The B coefficients (log odds) indicate the increased or decreased likelihood of being in one latent subgroup compared to another one, as the predictor variable increases by one unit. Participants who reported higher PTSD symptom severity and who were at the enclave when it fell were significantly more likely to be in the high-exposure class than in the other two classes, and more likely to be in the moderate-exposure class than in the betrayal and powerlessness-only class. Participants’ reported PTG did not differentiate significantly between classes.

Table 4. Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) of the predictor variables per latent class.

Table 5. Multinomial regression analysis of PMIE classes on PTSD, PTG, and location.

4. Discussion

4.1. Outcomes

The purpose of this study was to examine patterns of PMIE exposure among Dutch peacekeepers, as well as associations between those patterns and potential outcome- and exposure-related factors. In line with our expectations, we found two subgroups reporting different levels of exposure and one subgroup reporting a specific type of PMIE, i.e. feelings of betrayal and powerlessness. While all subgroups reported having felt betrayed and powerless, the latter subgroup was distinct in reporting only these PMIEs – i.e. their overall exposure to other PMIEs was low. Also as hypothesized, being present at the fall of Srebrenica was associated with more PMIE exposure, and more PMIE exposure was associated with higher odds of having PTSD 25 years later. Levels of PTG did not differ between classes. We excluded resilience and QoL from the regression analysis as these constructs highly overlapped with PTSD symptom severity.

Our results display both similarities to and differences from earlier LCAs with combat veterans. Prior work with US veterans similarly found subgroups characterized by high and moderate PMIE exposure, while also identifying subgroups characterized by specific but different PMIE types (Saba et al., Citation2022). Likewise, and partially aligning with our results, a study of Israeli combat veterans found subgroups who reported high exposure and experiences of betrayal, but also a large subgroup who reported little PMIE exposure overall (Zerach et al., Citation2021). Some of these differences might be attributed to prior studies relying on the Moral Injury Events Scale (Nash et al., Citation2013), which contains items that differentiate between self- and other-related PMIEs and betrayal. The MIQ-M, while assessing a wider range of PMIEs, does not distinguish between acts of commission and omission/witnessing, which may have impacted our results. It is also conceivable, however, that our results reflect the nature of this mission, which is generally considered morally injurious because of the genocide that took place and Dutchbat III’s inability to intervene. Notably, all classes in our study displayed high odds of endorsing two items indicative of feeling like the situation was beyond one’s control and of feeling betrayed by political and military leadership. Such experiences of betrayal and powerlessness, of being prevented from engaging in combat despite witnessing severe human distress, are precisely what might make peacekeeping missions morally injurious (Dallaire & Beardsley, Citation2003; Molendijk, Citation2021).

As expected, presence at the fall of Srebrenica – representing an indication of greater exposure to suffering – was associated with more exposure to PMIEs. Prior research has suggested that during combat missions, greater combat exposure increases the risk of PMIEs (Bryan et al., Citation2016; Currier et al., Citation2015; Maguen et al., Citation2010). During peacekeeping missions, however, where service members may be exposed to combat but generally do not engage in it directly, a more relevant predictor of PMIEs might be exposure to human distress. Such exposure might be particularly morally injurious when soldiers feel powerless before it – possibly because such situations elicit feelings of empathy that cannot be acted upon (Ter Heide, Citation2020). Generally, people are more inclined to feel empathy when they feel connected to someone (because they know or like them, or are like them) or when there is a strong desire to help. This seems to apply to Dutchbat III veterans at Srebrenica, who were in close contact with the local population and generally felt impelled to protect them (Molendijk, Citation2021). Therefore, as veterans who were at the enclave were disproportionately exposed to civilian suffering, they also seem to have been disproportionately affected. These findings thus highlight the importance of better understanding how feelings of empathy and powerlessness might contribute to PMIEs.

Our analysis of behavioural outcomes suggests that more PMIE exposure is associated with more negative outcomes, including higher PTSD symptom severity and lower quality of life. As pointed out by Saba et al. (Citation2022), this aligns with studies of cumulative trauma exposure, which suggest that exposure to multiple traumatic events increases the odds of developing negative behavioural outcomes compared with exposure to a single traumatic experience (Davis et al., Citation2022; Macia et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, given that our data were collected 25 years post-deployment, this also supports the idea that the consequences of PMIE exposure may be lifelong – an idea that is often reiterated in the moral injury literature (Currier et al., Citation2021).

Because resilience and QoL highly overlapped with PTSD symptom severity, we removed these variables from the regression analysis. While QoL and resilience have been shown to be inversely related to PTSD among veterans (King et al., Citation1998; Pietrzak et al., Citation2009; Schnurr et al., Citation2009), studies have used differing operationalizations of resilience, complicating direct comparisons across studies (Windle et al., Citation2011). Additionally, this study found no association between PMIE exposure and PTG, possibly because prior research has specifically associated PTG with perceived moral violations by the self, rather than PMIE exposure overall (Evans et al., Citation2018; Hijazi et al., Citation2015).

4.2. Limitations and strengths

Several of the study’s limitations require further elaboration. First, because this study concerned a secondary data analysis, measured negative mental health outcomes were limited to PTSD. Additionally, the MIQ-M was translated into Dutch for the original study and this Dutch version was not psychometrically validated. Moreover, as the MIQ-M conflates events and reactions to events, it is possible that the inclusion of effect items in the LCA impacted our results. However, as the effect items were particularly relevant for the experiences of Dutchbat III (e.g. item 1, concerning feelings of betrayal), we decided to retain these items while using a different dichotomization for event and effect items in the LCA. Also, as the MIQ-M was originally developed based on the experiences of US warzone veterans (Currier et al., Citation2015), it might not fully match the experiences of peacekeeping soldiers. Some additional items, more aligned with the experiences of peacekeepers, could make the MIQ-M a more widely applicable instrument, appropriate for veterans from combat and non-combat missions alike.

Further, even though the Dutchbat mission has been exceptionally impactful, for individual lives as well as societies, no exclusive causality can be assigned to the relationship between the events in Bosnia and the response 25 years later. Other life events may have had an impact on veterans’ wellbeing – the assessment of events that took place in the intermediate time was beyond the scope of this research. However, most veterans who met a diagnosis of probable PTSD indicated that they felt their symptoms were related to the mission. In addition, compared to assessments of other cohorts (Reijnen & Duel, Citation2019), the number of Dutchbat III veterans suffering from mental health difficulties was higher – underlining the significance of the events in Srebrenica, Bosnia in 1995.

Lastly, many Dutchbat III veterans feel they were negatively impacted by the societal condemnation that followed the Srebrenica genocide (Olff et al., Citation2020) and this possibly aggravated some veterans’ moral suffering (Molendijk, Citation2021). Unfortunately, the current study was unable to assess this, and generally measures of PMIE exposure do not inquire about the experience of public condemnation. However, moral outrage directed at a military intervention or lack thereof is not unique to the Dutchbat III mission (Klep, Citation2008) and might affect veterans already struggling with their conscience. Little is currently known about the ways in which societal condemnation of a morally injurious situation may contribute to moral distress, posing a fruitful avenue for future research.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study was the first to employ LCA to examine patterns of PMIE exposure in peacekeepers. By collecting data among Dutchbat III veterans – former peacekeepers known to have experienced a deeply tragic and potentially morally injurious event – we were able to investigate if respondent location at the time of this event impacted these patterns and subsequent outcomes. Over half the battalion participated in this study, which may be considered a particularly high response rate for a veteran sample.

We also contributed to the PMIE literature by partially replicating prior work with LCAs, while also being the first study to jointly examine PTG, resilience, and QoL in the context of PMIE exposure. Moreover, this study was the first to carry out a long-term follow-up of PMIE exposure and associated outcomes and demonstrated an association between current PTSD symptom severity and PMIE exposure 25 years prior. The study’s outcomes thus point to the potentially lifelong consequences of exposure to PMIEs, which require further systematic study.

4.3. Implications and conclusion

Our results emphasize the importance of better understanding PMIE exposure and experiences of powerlessness among peacekeeping forces – particularly when acts of omission result from the mission’s mandate. While acts of omission are assessed by currently available instruments measuring PMIEs, such acts are commonly described as a personal rather than an institutional failure. To better understand such experiences and their impact, items assessing PMIEs characteristic of peacekeeping missions – such as situations marked by powerlessness and the inability to intervene – would be a meaningful addition to any instrument assessing PMIEs. Indeed, for both treatment and research purposes, a measure of PMIE exposure that is more widely applicable to veterans from different nations and missions, and that does not conflate events and reactions to events, would be very valuable.

Another implication is the importance of monitoring and proper, easily-accessible aftercare when veterans are known to have been stationed in places where PMIEs occurred. In fact, over half of all Dutchbat III veterans had wished to receive support after the mission and, 25 years later, a third still express a need for treatment (Olff et al., Citation2020). Moreover, as demonstrated by this study, nearly a quarter still meet criteria for probable PTSD. These findings stress the importance of exploring the role of PMIE exposure and its impact on peacekeepers’ poorer post-deployment wellbeing. Simultaneously, as Molendijk (Citation2021) has justly pointed out, an overly narrow focus on mental health care as a solution to moral injury may distract from ways in which political decisions can contribute to moral distress. The experiences of Dutchbat III therefore not only stress the importance of proper aftercare, but also serve as a reminder of how moral injury should not be treated as an exclusively individual phenomenon.

In conclusion, among peacekeeping veterans, we found various levels of PMIE exposure. Those who had been exposed to more human suffering reported higher levels of PMIE exposure, and higher PMIE exposure was associated with worse psychological outcomes 25 years later. We believe these results highlight the importance of better understanding morally injurious experiences within peacekeeping, so that interventions for moral injury post-peacekeeping can be tailored accordingly.

Supplements.docx

Download MS Word (35.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors thank Charlie Steen, Ilse Raaijmakers, Joris Haagen, Hans te Brake, Marieke Sleijpen, and Mercede van Voorthuizen for their contributions to the data collection; Anne Marthe van der Bles, Bart Nauta, Onno Sinke, and Tine Molendijk for their contributions to the design of this study; and Bart Hetebrij for his contributions to the design of this study and for commenting on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2014). Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using M plus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(3), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.915181

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20

- Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

- Bowerman, B. L., & O'Connell, R. T. (1990). Linear statistical models: An applied approach (2nd ed.). Duxbury Press.

- Bryan, C. J., Bryan, A. O., Anestis, M. D., Anestis, J. C., Green, B. A., Etienne, N., & Ray-Sannerud, B. (2016). Measuring moral injury: Psychometric properties of the moral injury events scale in two military samples. Assessment, 23(5), 557–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115590855

- Celeux, G., & Soromenho, G. (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01246098

- Crane, M. F., Phillips, J. K., & Karin, E. (2015). Trait perfectionism strengthens the negative effects of moral stressors occurring in veterinary practice. Australian Veterinary Journal, 93(10), 354–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12366

- Currier, J. M., Drescher, K. D., & Nieuwsma, J. (2021). Addressing moral injury in clinical practice. American Psychological Association.

- Currier, J. M., Holland, J. M., Drescher, K., & Foy, D. (2015). Initial psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Questionnaire—Military version. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1866

- Dallaire, R., & Beardsley, B. (2003). Shake hands with the devil: The failure of humanity in Rwanda. Random House Canada.

- Davis, J. P., Lee, D. S., Saba, S., Fitzke, R. E., Ring, C., Castro, C. C., & Pedersen, E. R. (2022). Applying polyvictimization theory to veterans: Associations with substance use and mental health. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(2), 144. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000781

- Dirkzwager, A. J. E., Bramsen, I., & Van Der Ploeg, H. M. (2005). Factors associated with posttraumatic stress among peacekeeping soldiers. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 18(1), 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800412336418

- Eid, M., Langeheine, R., & Diener, E. (2003). Comparing typological structures across cultures by multigroup latent class analysis: A primer. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(2), 195–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102250427

- Evans, W. R., Szabo, Y. Z., Stanley, M. A., Barrera, T. L., Exline, J. J., Pargament, K. I., & Teng, E. J. (2018). Life satisfaction among veterans: Unique associations with morally injurious events and posttraumatic growth. Traumatology, 24(4), 263. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000157

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Fitzpatrick, J. J., Pignatiello, G., Kim, M., Jun, J., O'Mathúna, D. P., Duah, H. O., Taibl, J., & Tucker, S. (2022). Moral injury, nurse well-being, and resilience among nurses practicing during the COVID-19 pandemic. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 52(7/8), 392–398. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000001171

- Geiser, C. (2013). Data analysis with Mplus. The Guilford press.

- Hijazi, A. M., Keith, J. A., & O'Brien, C. (2015). Predictors of posttraumatic growth in a multiwar sample of US Combat veterans. Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology, 21(3), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000077

- Jaarsma, T. A., Pool, G., Sanderman, R., & Ranchor, A. V. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Dutch version of the posttraumatic growth inventory among cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 15(10), 911–920. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1026

- King, L. A., King, D. W., Fairbank, J. A., Keane, T. M., & Adams, G. A. (1998). Resilience–recovery factors in post-traumatic stress disorder among female and male Vietnam veterans: Hardiness, postwar social support, and additional stressful life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.420

- Klep, C. (2008). Somalië, Rwanda, Srebrenica. De nasleep van drie ontspoorde vredesmissies [Somalia, Rwanda, Srebrenica. The aftermath of three derailed peacekeeping missions]. Boom Uitgevers.

- Lancaster, S. L., & Harris, J. I. (2018). Measures of morally injurious experiences: A quantitative comparison. Psychiatry Research, 264, 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.057

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Macia, K. S., Moschetto, J. M., Wickham, R. E., Brown, L. M., & Waelde, L. C. (2020). Cumulative trauma exposure and chronic homelessness among veterans: The roles of responses to intrusions and emotion regulation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(6), 1017–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22569

- Maguen, S., Lucenko, B. A., Reger, M. A., Gahm, G. A., Litz, B. T., Seal, K. H., Knight, S. J., & Marmar, C. R. (2010). The impact of reported direct and indirect killing on mental health symptoms in Iraq war veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(1), 86–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20434

- Maguen, S., Nichter, B., Norman, S. B., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2021). Moral injury and substance use disorders among US combat veterans: Results from the 2019–2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Psychological Medicine, 53(4), 1364–1370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001628

- Molendijk, T. (2018). Toward an interdisciplinary conceptualization of moral injury: From unequivocal guilt and anger to moral conflict and disorientation. New Ideas in Psychology, 51, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2018.04.006

- Molendijk, T. (2021). Moral injury and soldiers in conflict: Political practices and public perceptions. Routledge.

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user's guide (8th ed.).

- Nash, W. P., Marino Carper, T. L., Mills, M. A., Au, T., Goldsmith, A., & Litz, B. T. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Military Medicine, 178(6), 646–652. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Olff, M., Raaijmakers, I., Te Brake, H., Haagen, J., Mooren, T., Nauta, B., & Van Voorthuizen, M. (2020). Focus op Dutchbat III: Onderzoek naar het welzijn van Dutchbat III-veteranen en de behoefte aan zorg, erkenning en waardering [Focus on Dutchbat III: Research into the well-being of Dutchbat III veterans and the need for care, recognition and appreciation]. ARQ Nationaal Psychotrauma Centrum.

- Pietrzak, R. H., Johnson, D. C., Goldstein, M. B., Malley, J. C., & Southwick, S. M. (2009). Psychological resilience and postdeployment social support protect against traumatic stress and depressive symptoms in soldiers returning from operations enduring freedom and Iraqi Freedom. Depression and Anxiety, 26(8), 745–751. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20558

- Priebe, S., Huxley, P., Knight, S., & Evans, S. (1999). Application and results of the Manchester short assessment of quality of life (MANSA). International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 45(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076409904500102

- Reijnen, A., & Duel, J. (2019). Veteraan, hoe gaat het met u? Achtergrondrapport [Veteran, how are you doing? Background report]. Dutch Veterans Institute.

- Rietveld, N. (2009). De gewetensvolle veteraan: Schuld- en schaamtebeleving bij veteranen van vredesmissies [The conscientious veteran: The experience of guilt and shame among veterans of peacekeeping missions]. BOXPress BV.

- Rushton, C. H., Thomas, T. A., Antonsdottir, I. M., Nelson, K. E., Boyce, D., Vioral, A., Swavely, D., Ley, C. D., & Hanson, G. C. (2022). Moral injury and moral resilience in health care workers during COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 25(5), 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0076

- Saba, S. K., Davis, J. P., Lee, D. S., Castro, C. A., & Pedersen, E. R. (2022). Moral injury events and behavioral health outcomes among American veterans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 90, 102605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102605

- Schnurr, P. P., Lunney, C. A., Bovin, M. J., & Marx, B. P. (2009). Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life: Extension of findings to veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 727–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.006

- Shay, J. (2014). Moral injury. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(2), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036090

- Shigemura, J., & Nomura, S. (2002). Mental health issues of peacekeeping workers. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 56(5), 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1819.2002.01043.x

- Smigelsky, M. A., Malott, J. D., Veazey Morris, K., Berlin, K. S., & Neimeyer, R. A. (2019). Latent profile analysis exploring potential moral injury and posttraumatic stress disorder among military veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 499–519. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22714

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Ter Heide, F. J. J. (2020). Empathy is key in the development of moral injury. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1843261. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1843261

- United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations. (2008). United Nations peacekeeping operations: Principles and guidelines. United Nations.

- United Nations Security Council. (1993). Resolution 824 (1993). https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/166133/files/S_RES_824%281993%29-EN.pdf.

- Van der Meer, C. A., Te Brake, H., Van der Aa, N., Dashtgard, P., Bakker, A., & Olff, M. (2018). Assessing psychological resilience: Development and psychometric properties of the English and Dutch version of the Resilience Evaluation Scale (RES). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00169

- Van Nieuwenhuizen, C., Janssen-de Ruijter, E. A. W., & Nugter, M. (2017). Handleiding Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA). Stichting QoLM.

- Van Praag, D. L., Fardzadeh, H. E., Covic, A., Maas, A. I., & von Steinbüchel, N. (2020). Preliminary validation of the Dutch version of the Posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) after traumatic brain injury in a civilian population. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231857

- Williamson, V., Stevelink, S. A., & Greenberg, N. (2018). Occupational moral injury and mental health: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(6), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.55

- Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-9-8

- Zerach, G., Levi-Belz, Y., Griffin, B. J., & Maguen, S. (2021). Patterns of exposure to potentially morally injurious events among Israeli combat veterans: A latent class analysis approach. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 79, 102378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102378