ABSTRACT

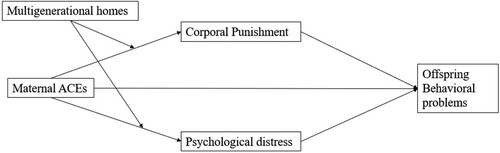

Background: Maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) may lead to increased behavioural problems in children. However, the mediating roles of psychological distress and corporal punishment, two common mechanisms underlying the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs, in these relations have not been examined in Chinese samples. Multigenerational homes (MGH) are the dominate living arrangement in China; however, limited research focuses on the effects of MGHs on the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs.

Objective: This study explored the parallel mediating effects of corporal punishment and psychological distress on the association between maternal ACEs and children’s behaviour and whether MGHs can strengthen or weaken the relationship between maternal ACEs and corporal punishment or psychological distress.

Participants and setting: Participants were 643 three-year-old children and their mothers (mean age of 32.85 years, SD = 3.79) from Wuhu, China.

Methods: Mothers completed online questionnaires measuring ACEs, psychological distress, corporal punishment, their family structure, and children’s behavioural problems. This study used a moderated mediation model.

Results: The findings suggest that psychological distress and corporal punishment mediate the association between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems. The mediating role of corporal punishment was found depend on whether mothers and their children reside in MGHs. MGHs were not found to have a moderating role in the indirect relationship between maternal ACEs and children’s behaviour problems via psychological distress.

Conclusion: Our findings highlight the importance of addressing psychological distress and corporal punishment when designing interventions targeted Chinese mothers exposed to ACEs and their children, especially those living in MGHs.

HIGHLIGHTS

Psychological distress and corporal punishment have parallel mediating roles in the associations between maternal adverse childhood experiences and offspring behavioural problems.

Mothers with more adverse childhood experiences and in multigenerational homes were more likely to use corporal punishment.

Multigenerational homes did not moderate the indirect relationship via psychological distress.

Antecedentes: Las experiencias adversas maternas infantiles (ACEs en su sigla en inglés) conlleva a un incremento de los problemas conductuales en los niños. Sin embargo, los roles mediadores del estrés psicológico y el castigo corporal, dos mecanismos subyacentes comunes en la transmisión intergeneracional de las ACEs maternas, en estas relaciones no han sido estudiados en muestras chinas. Los hogares multigeneracionales (MGHs en su sigla en inglés) son el arreglo de vivienda dominante en China; sin embargo, la investigación enfocada en los efectos de los MGHs en la transmisión intergeneracional de las ACEs maternas es limitada.

Objetivo: Este estudio exploró los efectos mediadores paralelos del castigo corporal y del estrés psicológico en la asociación entre ACEs maternas y conducta infantil, y si los MGHs pueden aumentar o disminuir la relación entre las ACEs maternas y el castigo coporal o el estrés psicológico.

Participantes y contexto: Los participantes fueron 643 niños de 3 años y sus madres (edad promedio 32.85 años, DE = 3.79) de Wuhu, China.

Método: Las madres completaron cuestionarios en línea que medían ACEs, estrés psicológico, castigo corporal, estructura familiar y problemas conductuales infantiles. Este estudio usó un modelo de mediación moderada.

Resultados: Los hallazgos sugieren que el estrés psicológico y el castigo corporal median la asociación entre ACEs maternas y problemas conductuales infantiles. El rol mediador del castigo corporal se encontró dependiendo de si las madres y sus hijos residían en MGHs. MGHs no moderaron la relación indirecta entre ACEs maternas y problemas conductuales infantiles mediante el estrés psicológico.

Conclusión: Nuestros resultados enfatizan la importancia de abordar el estrés psicológico y el castigo corporal a la hora de diseñar intervenciones dirigidas a madres chinas expuestas a ACEs y sus hijos, especialmente a aquellos viviendo en MGHs.

1. Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that individuals face before the age of 18 years, such as maltreatment (sexual, physical, and emotional abuse and neglect) and family stressors, including witnessing violence at home, parental mental health problems, parental divorce or separation, parental incarceration, and drug and alcohol abuse issues in the home (Felitti et al., Citation1998). Studies have shown that ACEs have long-lasting negative health effects (Petruccelli et al., Citation2019). Recently, researchers have turned their attention toward understanding the transmission of ACEs across generations, particularly the effect of maternal ACEs on their offspring’s developmental outcomes (Cooke et al., Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). A recent study suggested that the intergenerational effects of ACEs may be transmitted through two common pathways: unfavourable parenting strategies and parental mental health (Schickedanz et al., Citation2018). However, few studies have examined the effects of the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs on children’s behavioural problems via mental health and unfavourable parenting practices among Chinese mother-child dyads.

Several studies have shown that, although the nuclear family has become the dominant family pattern in China in recent decades, permanently or temporarily living in multigenerational homes (MGHs) with their parents is still relatively common for children because of intergenerational relationship patterns, residential habits, family needs, the absence of state patronage, and inadequate social security systems (Chen et al., Citation2011; Ma et al., Citation2011; Wang, Citation2013). Studies have shown that MGHs may play a moderating role in the relationship between children’s behavioural problems and academic performance by reducing maternal stress and depressive symptoms (Jalapa et al., Citation2023; Zhang & Wu, Citation2021). However, little research has been conducted on whether MGH plays a moderating role in the relationship between children’s behavioural problems and different levels of maternal ACEs. In China, 69.7% of mothers report having had at least one type of ACE (Wang et al., Citation2022). Therefore, the underlying mechanisms and potential protective factors for preventing the intergenerational transfer of trauma are important to explore.

1.1. Maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children

Within the Chinese traditional culture background, mothers are considered as the primary caregivers of the children (Park & Chesla, Citation2007). The study documented that 69% of the mothers were the primary caregivers in Chinese households (Zhong et al., Citation2021). According to attachment theory, unresolved trauma in a mother may impair her ability to respond sensitively to her infant and develop a secure attachment, which may lead to trauma transmission across generations (Sroufe, Citation2005; Iyengar et al., Citation2014). Research revealed almost 85.8% mothers of Chinese preschoolers has experienced at least one type of ACEs (Luo et al., Citation2023). Therefore, we should pay more attention to Chinese mothers who experienced ACEs to interrupt the intergenerational transmission of trauma.

Children’s behavioural problems can be characterised by two broad factors: internalising problems like anxiety and depression, and externalising problems like aggression, oppositional behaviour, and hyperactivity (Vergunst et al., Citation2023). A growing body of research suggests that maternal ACEs may increase the risk of their offspring experiencing behavioural problems (Cooke et al., Citation2021; Racine et al., Citation2018). For example, Madigan et al. (Citation2017) found that maternal ACEs can negatively affect emotional problems in infants. A prenatal longitudinal study of 1030 mother–child dyads found that maternal ACEs influenced children’s internalising behaviours (Shih et al., Citation2023). Research in Eastern countries has also show that maternal ACEs are related to behavioural problems in children. For instance, in China, Zhu et al. (Citation2023) found that high levels of maternal ACEs were related to high levels of behavioural problems in children. A population-based study in Japan reported that the children of mothers with a larger number of ACEs showed higher levels of behavioural problems and depressive symptoms (Doi et al., Citation2021). Although many researchers agree that a link exists between maternal ACEs and offspring behavioural problems, the mechanism underlying it is complex. Research on the underlying mechanism of and protective factors for the intergenerational transmission of trauma is needed, as it could potentially enhance causal inferences and offer implications for practice (Zhang et al., Citation2022).

1.2. Psychological distress and corporal punishment as mediators

Psychological distress refers to non-specific feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression, which are more common among women (Viertiö et al., Citation2021). Corporal punishment can be defined as the use of physical force with the intention of causing a child pain, but not injury, for the purpose of correcting or controlling the child’s behaviour (Straus et al., Citation1998). Maternal psychological distress and corporal punishment are two factors that may partially explain the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs (McDonald et al., Citation2019). Extensive research has shown that ACEs are associated with poor mental health in adults (Daníelsdóttir et al., Citation2024; Merrick et al., Citation2017). For example, individuals with at least one ACE are more likely to experience psychological distress than those without ACEs (Manyema et al., Citation2018; Rudenstine et al., Citation2019). One possible explanation is that ACEs can result in the inability to control negative emotional reactions and intense emotional reactivity, which may lead to later psychological distress (Badour & Feldner, Citation2013). Furthermore, previous studies have shown that maternal psychological distress is related to problematic behaviours in their children (Lê-Scherban et al., Citation2018; Schickedanz et al., Citation2018). Hails et al. (Citation2018) emphasized that maternal depression is one of the most consistent and well-replicated risk factors for negative child outcomes, particularly in early childhood. A meta-analysis revealed that parental mental health is the most common indirect pathway for the intergenerational transmission of ACEs (Zhang et al., Citation2022). However, few studies have explored the mediating role of psychological distress in the Chinese population.

Parenting practices have been explored for their potential mediating effect on the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs. Childhood maltreatment frequently influences a mother’s view of being a caregiver, making them more likely to adopt negative attitudes and beliefs about parenting than mothers who were not maltreated as children (Wright et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, mothers who experienced adversity early in life tend to rely more on corporal punishment than mothers who did not (Yoon et al., Citation2019). The association between corporal punishment and children’s behavioural problems has been well-documented in previous research (Fu et al., Citation2019; Neaverson et al., Citation2020). According to the dimensional model of adversity (McLaughlin et al., Citation2014), exposure to painful or distressing experiences that involve harm or the threat of harm to a child, such as corporal punishment, can influence the development of that child’s neural systems that underpin emotional regulation and threat detection abilities, potentially leading to behavioural problems (Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, Citation2016). Although corporal punishment has been examined in several previous studies that suggested it may play a mediating role in the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs, only one study examined this potential mediating effect of parenting practices (i.e. emotional warmth and overprotection) in a Chinese population (Luo et al., Citation2023). Therefore, research is needed on the mediating roles of psychological distress and corporal punishment in the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs in a Chinese sample.

1.3. MGH as a moderator

MGH is the dominant living arrangement in China (over 60%) (United Nations, Citation2022). Studies have shown that Chinese grandparents are more likely than Western European grandparents to live with their grandchildren in both rural and urban areas (Zhang et al., Citation2020). Previous studies have indicated that MGHs may affect the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs (Coleman, Citation1988; Silverstein & Ruiz, Citation2006). According to Silverstein and Ruiz (Citation2006), grandparents protect their grandchildren’s long-term mental health by reducing the probability of unfavourable parenting and a stressful home environment caused by maternal ACEs. If grandparents offer advice and emotional support to parents, this may result in less parental stress and better parental mental health, which may lead to better outcomes for children. Furthermore, according to Coleman’s (Citation1988) model of intergenerational closure, grandparents may cooperate with parents to impose consistent rules and monitor the activities of children in the home. Poblete and Gee (Citation2018) found grandparent support can increase the co-parenting quality among African American and Latina adolescent mothers. Studies also indicate that when a teenage mother resides in the same family as her grandmother, it enhances the level of mothering and, therefore, improves the likelihood of establishing safe mother-infant attachment bonds (Spieker & Bensley, Citation1994). Grandparent involvement improves children’s social outcomes (Luo, Qi, et al. Citation2020). However, several studies indicated the negative effect of MGH on parents’ and grandchildren’s outcomes. For instance, grandparents may increase parents’ mental health problems if their engagement interferes with or subverts parenting behaviours (Dunifon & Bajracharya, Citation2013). Hoang et al. (Citation2020) found that grandparents’ psychological control is significantly and positively related to co-parenting conflict. Barnett et al. (Citation2012) suggested that mother-grandmother conflict may increase the frequency of maternal negative parenting strategies use, which may present a risk to children’s social-emotional and behavioural problems. Therefore, MGHs may play a moderating role in the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs by influencing maternal parenting practices and mental health.

1.4. The current study

Although the relationship between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children has been well-documented in Western samples, the underlying mechanism and protective factors in the Chinese context require further investigation. Thus, using a moderated mediation model (), this study aimed to explore the underlying mechanism and protective factors of the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs. Based on previous studies, we hypothesised that the following: (1) maternal ACEs have a positive direct effect on behavioural problems in children; (2) maternal psychological distress and corporal punishment have parallel mediating roles in the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs. Mothers who are exposed to higher-level ACEs tend to report a higher level of psychological distress and a higher frequency of corporal punishment use, which may lead their children to have more behavioural problems; (3) MGH plays a protective role in the indirect pathway between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children via corporal punishment as well as MGH moderates the link between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems via psychological if these linkage is stronger among mothers with high ACEs levels.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedures

This study used the baseline year data from the Wuhu Family Study. Located in Central China, the gross domestic product (GDP) of Wuhu City in 2023 was CNY 4,74.1 billion, representing the second largest economy in Anhui province and a moderate level in China. Based on the socioeconomic status (SES) and density of children in the area, we selected 11 kindergartens at random from seven districts in Wuhu between October and December 2022, including both rural and urban areas. The teachers and principals of kindergartens were made aware of the study’s objectives. Prior to enrolling their children in kindergarten, parents were asked to provide information about their children’s health, including allergies, chronic illnesses, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Children with any health problems and those whose parents had communication impairments or physical and mental illnesses were also excluded from the study. The details of this study can be found in our previous studies (Zhu et al., Citation2022, Citation2023). In this study, we focused on the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs. After informing kindergarten principals and teachers of this study’s objectives, we sent invitations to all qualified children newly enrolled (age 3) in kindergarten and their mothers to participate in our cohort study. All parents were informed of the study’s aim and methods, as well as their right to withdraw at any time. After parents provided informed consent, they were asked to complete an online survey on the ‘WenJuanXing’ platform. A total of 669 mother–child dyads received the questionnaire, and 643 mothers provided valid data that was used for the analysis. The affiliated university’s ethical committee approved this project.

Our sample comprised 643 3-year-old preschoolers (53.3% male) with a mean age of 42.75 months (SD = 3.58). The mean age of the mothers who participated in the study was 32.85 years old (SD = 3.79). Participants’ annual family income ranged from below ¥50,000 to above ¥300,000, with the average income reported to be between ¥100,000 and ¥150,000. presents the descriptive statistics for the participants and the study’s variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. ACEs

The Chinese version of the Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) was used in this study to examine maternal ACEs (WHO, Citation2019; Zhu et al., Citation2023). Mothers were asked to retrospectively report ACEs before the age of 18 years. The ACE-IQ includes seven categories: emotional neglect (2 items), physical neglect (3 items), emotional abuse (2 items), physical abuse (2 items), community violence (2 items), peer bullying (3 items), and household dysfunction (6 items). Owing to the sensitivity of the topic in China, questions regarding sexual abuse were omitted from the questionnaire (Wang et al., Citation2022). Participants responded ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on a 2-point scale measuring household dysfunction. If they responded ‘yes’ to any of the six questions regarding experience of household dysfunction, it was coded as ‘1’, and ‘0’ if the answer was ‘no’. The remaining 14 items were scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very often true). Mothers were regarded to have been exposed to ACEs if they answered ‘rarely true’, ‘sometimes true’, ‘often true’, or ‘very often true’ to any of the items and coded as ‘1’; otherwise, they were coded ‘0’. In this study, cumulative ACE-IQ scores ranged between 0 and 7.

2.2.2. Corporal punishment

The Chinese version of the Parent–Child Conflict Tactics Scale was used in this study to measure maternal use of corporal punishment (CTSPC, Straus et al., Citation1998; Wang & Liu, Citation2014). The Chinese version of the CTSPC contains five subscales: nonviolent discipline (4 items), psychological aggression (5 items), corporal punishment (6 items), severe physical assault (3 items), and very severe physical assault (4 items). In this study, we focused on the corporal punishment subscale. Mothers reported how frequently they had engaged in specific behaviours toward their children in the previous six months: never (0), once (1), twice (2), 3–5 times (3), 6–10 times (4), 11–20 times (5), and >20 times. We recorded ratings of 3–6 as the midpoint of each category (i.e. 3 = 4 times, 4 = 8 times, 5 = 15 times, and 6 = 25 times) to determine the frequency of corporal punishment, according to previous studies (Straus et al., Citation1998). Corporal punishment subscale has been widely used among Chinese samples and shown good reliability, the Cronbach’s α was 0.70 in this study.

2.2.3. Psychological distress

The Chinese version of the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) was used in this study to assess maternal psychological distress (combined feelings of anxiety and depression) (Kessler et al., Citation2002; Zhou et al., Citation2008). Mothers responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never felt) to 5 (feel all the time) to describe their feelings about psychological distress (i.e. nervous, helpless, depressed) in the past four weeks. Total K10 scores ranged between 10 and 50, with higher scores indicating a greater level of psychological distress. In this study, Cronbach’s α for the K10 was 0.94.

2.2.4. MGH

Mothers were asked to indicate whether a grandparent was currently part of their household (1 = yes, 2 = no). This variable was coded as ‘1’ if at least one grandparent was present and ‘2’ if no grandparents were present to determine whether a home was multigenerational (Jalapa et al., Citation2023; Zhang & Wu, Citation2021).

2.2.5. Behavioural problems

Behavioural problems in preschoolers were assessed using the Chinese version of the Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ, Du et al., Citation2008; Goodman, Citation2001). Mothers were asked to answer each item based on their child’s behaviour over the previous six months. The questionnaire was divided into five scales, each with five items: emotional problems, conduct problems, hyperactivity, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behaviour. Each item was rated on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true), with total scores ranging between 0 and 50. We summed the scores of the four subscales, excluding prosocial behaviour, to calculate a total score reflecting behavioural problems. Higher scores indicated higher levels of behavioural problems. In this study, Cronbach’s α for the SDQ was 0.64.

2.2.6. Covariates

Based on previous studies indicating the importance of covariates when examining maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems, mothers’ age (years), sex (1 = male, 2 = female), and family SES were included as covariates (Wang et al., Citation2022; Zhu et al., Citation2023). We used both the mother’s and father’s occupations (1 = unemployed, nontechnical workers, and farmers; 2 = semi-technical workers and small business owners; 3 = technical workers and semi-professionals; 4 = professionals, officers, and mid-sized business owners; and 5 = high-level professionals and administrators) and education levels (1 = primary school or lower, 2 = middle school or lower, 3 = high school or vocational secondary school, 4 = Vocational college degree, 5 = Bachelor’s degree, 6 = Master’s degree or above), as well as family annual income (1 ≤ 50,000 RMB, 2 = 50,001–100,000 RMB, 3 = 100,001–150,000 RMB, 4 = 150,001–300,000 RMB, 5 ≥ 300,000 RMB), to determine family SES.

2.3. Statistical analysis

First, we performed descriptive and correlation analyses. Second, we applied Hayes (Citation2017) PROCESS macro to examine the moderated mediation model. We utilised PROCESS macro Model 4 to examine the mediating roles of corporal punishment and psychological distress, and PROCESS macro Model 7 to test the moderating effect of maternal MGH. A total of 5000 bootstrap samples were used to estimate the 95% confidence intervals for the significance of effects. Unstandardised coefficients were reported in both the parallel mediation model and the moderated mediating model. The mothers’ age, children’s sex, and family’s SES were considered covariates in the data analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Based on the guidelines of severe non-normality (i.e. skewness >3; kurtosis >10) proposed by Curran et al. (Citation1996), the main variables in this study met the guidelines, where the skewness values were <3, and kurtosis values were <10. The skewness values for maternal ACEs, psychological distress, corporal punishment, and behavioural problems were 0.081, 0.439, 1.769, and 1.609, respectively. The kurtosis values for maternal ACEs, psychological distress, corporal punishment, and behavioural problems were −1.012, 6.604, 5.199, and 0.191, respectively. Moreover, Tabachnick and Fidell’s (Citation2007) standards of a z-score of ≥3.29 (or a likelihood of p < .001) were used to determine whether our data contained any outliers. Results showed that our data did not contain any outliers.

presents the descriptive statistics for mothers, children, maternal ACEs, corporal punishment, psychological distress, and children’s behavioural problems. The means and standard deviations of the ages of the mothers and their children were 32.85 ± 3.79 years and 42.75 ± 3.58 months, respectively. Of the children, 53.3% (n = 343) were boys, 46.7% (n = 300) were girls. The mean maternal ACE score was 2.93 ± 1.78. The average scores for mothers’ psychological distress, corporal punishment, and children’s behavioural problems were 15.11 ± 5.22, 6.91 ± 11.16, and 8.89 ± 3.60, respectively. shows the bivariate correlations of the main variables.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations among the main variables.

3.2. Mediation model

shows the mediating roles of corporal punishment and psychological distress in the relationship between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children. The results show a direct association between total maternal ACEs scores and children’s behavioural problems (b = 0.31, p < .001). In addition, presents the indirect paths. We found that maternal ACEs were positively related to corporal punishment (b = 1.16, p < .001), which in turn was associated with children’s behavioural problems (b = 0.03, p < .01). We also found that maternal ACEs were positively related to psychological distress (b = 0.98, p < .001), which in turn was associated with children’s behavioural problems (b = 0.11, p < .001). Our results further indicate that corporal punishment (indirect effect = 0.04, Boot SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.08]) and psychological distress (indirect effect = 0.11, Boot SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.05, 0.18]) mediate the relationship between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems.

Table 3. Mediating effects of corporal punishment and psychological distress on maternal adverse childhood experiences and children’s behavioural problems.

3.3. Moderated mediation model

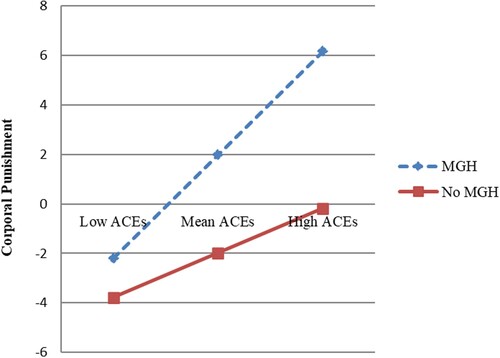

shows the results of moderated mediation model, according to Model 7. The interaction between maternal ACEs and MGHs was negatively associated corporal punishment (b = −1.19, p < .05), indicating that MGHs moderate the effect of maternal ACEs on corporal punishment. Furthermore, the simple slope () indicates the moderating role of MGHs. For those residing in MGHs, the relationship between maternal ACEs and corporal punishment was significant (b = 1.81, t = 4.90, p < .001). However, this relationship was much weaker, albeit still statistically significant, for mothers and children who did not live in MGHs (b = 0.62, t = 1.97, p < .05). Specifically, living with grandparents was found to strengthen the relationship between maternal ACEs and corporal punishment. However, the interaction between maternal ACEs and MGHs was not found to be associated with psychological distress (b = 0.05, p = .8).

Figure 2. Multigenerational homes as a moderator of the relationship between maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and corporal punishment.

Table 4. Moderated mediation model.

The results of testing for conditional indirect effects showed that, for mothers and their children living in MGHs, the indirect effect between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems via corporal punishment was significant (b = 0.06, SE = 0.27, 95% CI = [0.02, 0.12]). However, this indirect effect was weaker for mothers and their children who did not live in MGHs (b = 0.02, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.01, 0.05]). This finding suggests that living in an MGH increases the negative relationship between maternal ACEs and corporal punishment, which in turn associated with high levels of behavioural problems in children.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to extend previous research by examining the mediating roles of psychological distress and corporal punishment and moderating role of MGHs in the relationship between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children. We found that psychological distress and corporal punishment mediated the association between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems, while MGHs moderated the indirect relationship between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems via corporal punishment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the mediating roles of psychological distress and corporal punishment and moderating role of MGH in the relationship between maternal ACEs and offspring behavioural problems in Chinese mother-child dyads. Thus, the results of this study may point to a potential need for such interventions to interrupt the intergenerational cycle of trauma.

Our results support the study’s first hypothesis that a positive direct pathway exists between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in three-year-old children, which is in line with previous research (Zhu et al., Citation2023). Previous studies have suggested that maternal ACEs can lead to developmental delays in infancy (Racine et al., Citation2018). Very young children can develop serious and debilitating mental health disorders at rates comparable to those in older children (Gleason et al., Citation2016). Young children, who have been largely neglected in trauma research, are vulnerable to negative outcomes caused by ACEs because they are developing rapidly, have few coping abilities, and rely heavily on their primary caregiver to protect them physically and emotionally (De Young et al., Citation2011). Therefore, the intergenerational transmission of trauma should be considered in interventions aimed at preventing behavioural problems in young children.

The current study found that psychological distress and corporal punishment play parallel mediating roles in the relationship between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children, which supports our second hypothesis. Similar to previous research (McDonald et al., Citation2019), our study found that high levels of maternal ACEs were related to high levels of psychological distress and a high frequency of corporal punishment, leading to increased behavioural problems in children by 3 years of age. According to attachment theory, parents with a history of maltreatment or household dysfunction are more likely to form insecure attachments with their parents and, eventually, their own children (Widom et al., Citation2018). Parents who were exposed to ACEs received inconsistent and insensitive care; therefore, they are more likely to use corporal punishment on their children and experience mental health problems. This is because they came to view others as unreliable based on their ACEs. These models influence how parents form attachments to their own children, which can adversely affect their capacity to be emotionally available and apply adaptive punishment practices under pressure. When children do not receive consistent emotional support from their parents, these maladaptive parenting techniques harm children’s psychological wellbeing, increasing the risk for internalising and externalising problems (Rowell & Neal-Barnett, Citation2022).

Our results support the third hypothesis that MGH plays a moderating role in the indirect relationship between maternal ACEs and behavioural problems in children via corporal punishment. In contrast to some previous studies, mothers who experienced ACEs and lived in MGHs were more likely to use corporal punishment, thus causing behavioural problems in their children. Although some studies suggested that grandparent involvement improves children’s social outcomes (Luo et al., 2020), they did not consider mothers with different levels of ACEs. Grandparents are seen as family authorities in many Asian cultures, and therefore have the power to intervene and decide how their grandchildren are raised (Goh, Citation2006). Grandparents may also disagree with or refuse to accept the parents’ viewpoints (Hoang et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the expectation of filial piety results in parents being unable to freely express their disagreement with grandparents, making them feel unheard (Leung & Fung, Citation2014). Women who have experienced physical and/or sexual abuse in childhood are more likely to report higher levels of interpersonal difficulties (Van der Kolk et al., Citation1993), fear of intimacy, and lower quality of past interpersonal interactions compared to women who have not experienced childhood adversities (Davis et al., Citation2001). Moreover, ACEs are associated with an increased fear of intimacy, difficulty in forming trusting relationships, anxiety in interpersonal relationships, and a reduced willingness to share feelings and thoughts with others (Davis et al., Citation2001; Ducharme et al., Citation1997). In this case, more conflicts we present in the mother–grandparent coparenting relationship when mothers experienced ACEs, compared to mother–father coparenting (Barnett et al., Citation2011). Mother–grandparent conflict may cause mothers to use negative parenting strategies (i.e. corporal punishment) more frequently (Luo et al., Citation2020), thereby increasing the likelihood their children will experience behavioural problems (Xu et al., Citation2023). However, we did not find a moderating role of MGH in the indirect relationship between maternal ACEs and children’s behavioural problems via psychological distress, which is in line with previous research (Racine et al., Citation2018). This finding could potentially be explained by a direct association between MGHs and psychological distress (Racine et al., Citation2018).

Our study enriches previous research by revealing the underlying mechanism and moderating factors of how maternal ACEs affect behavioural problems in children. A strength of this study is that it revealed whether psychological distress and corporal punishment play mediating roles in the intergenerational transmission of trauma between mothers and their young children. In addition, our study suggests that MGHs help moderate the relationship between maternal ACEs and corporal punishment. Nevertheless, this study has some limitations. First, retrospective reports of maternal ACEs may be subject to decreased accuracy due to elapsed time (Henry et al., Citation1994). Second, despite childhood sexual abuse being linked to behavioural problems among children worldwide (Linde-Krieger & Yates, Citation2018), we did not include it in this study because it is a sensitive topic in China (Zhu et al., Citation2023). This topic may have caused adverse reactions in participants due to the shame and sensitivity associated with sexual victimisation in China (Wang et al., Citation2022). Third, we did not distinguish between stepparents and biological parents, or between maternal and paternal grandparents. Fourth, studies indicated that grandparents’ physical function may be the risk factor for grandparent-parent co-parenting quality and grandchildren health outcomes (Luo et al., Citation2012). In our study, data of grandparents’ physical condition was not collected. We suggest that future studies include grandparents’ physical condition to examine the role of MGH in the intergenerational transmission of ACEs. Furthermore, grandparents’ SES was not included in this study. We suggest that future research explore the effects of more factors (i.e. grandparents) when studying MGH. Finally, the available data is not longitudinal and that parent distress reflects the parent report of the past four weeks whereas the measures of corporal punishment and behavioural problems assess parent report of the past six months. Therefore, the current research is unable to inferred causal relationships between the studying variables. This encourages future studies to apply longitudinal research and establish a clearer understanding of the relationship between maternal ACEs, psychological distress, corporal punishment, and children’s behavioural problems.

5. Conclusion

Our findings suggest that maternal ACEs increase the risk of that their offspring will experience behavioural problems in early childhood via psychological distress and corporal punishment. This emphasizes the necessity of addressing maternal psychological distress and corporal punishment as potential intervention targets to break the cycle of intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs. Although maternal ACEs were found to be related to offspring behavioural problems regardless of the level of corporal punishment, the effect was more pronounced for mothers and children living in MGHs. We suggest that specific interventions should be provided to mothers living in MGHs who have had exposure to ACEs.

Authors’ contributions

Yantong Zhu: Formal analysis, methodology, writing–original draft, and conceptualisation.

Gengli Zhang: Visualisation, supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition.

Shuwei Zhan: Data curation, editing, and review.

Dandan Jiao: Investigation and review.

Tokie Anme: Editing and review.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

Consent for publication

The authors consent to the publication of this work in the journal.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anhui Normal University (AHNU-ET2021034). The children’s parents were informed about the study’s objectives and processes, and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Acknowledgments

We express our deepest gratitude to all the participants and staff members.

Data availability statement

Datasets generated or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Badour, C. L., & Feldner, M. T. (2013). Trauma-related reactivity and regulation of emotion: Associations with posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 44(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2012.07.007

- Barnett, M. A., Mills-Koonce, W. R., Gustafsson, H., Cox, M., & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2012). Mother-grandmother conflict, negative parenting, and young children’s social development in multigenerational families. Family Relations, 61(5), 864–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00731.x

- Barnett, M. A., Scaramella, L. V., McGoron, L., & Callahan, K. (2011). Coparenting cooperation and child adjustment in low-income mother-grandmother and mother-father families. Family Science, 2(3), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/19424620.2011.642479

- Chen, F. N., Liu, G. Y., & Mair, C. A. (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China. Social Forces, 90(2), 571–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sor012

- Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120. https://doi.org/10.1086/228943

- Cooke, J. E., Racine, N., Pador, P., & Madigan, S. (2021). Maternal adverse childhood experiences and child behavior problems: A systematic review. Pediatrics, 148(3). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-044131

- Cooke, J. E., Racine, N., Plamondon, A., Tough, S., & Madigan, S. (2019). Maternal adverse childhood experiences, attachment style, and mental health: Pathways of transmission to child behavior problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 93, 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.011

- Curran, P. J., West, S. G., & Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16

- Daníelsdóttir, H. B., Aspelund, T., Shen, Q., Halldorsdottir, T., Jakobsdóttir, J., Song, H., Lu, D., Kuja-Halkola, R., Larsson, H., Fall, K., Magnusson, P. K. E., Fang, F., Bergstedt, J., & Valdimarsdóttir, U. A. (2024). Adverse childhood experiences and adult mental health outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry.

- Davis, J. L., Petretic-Jackson, P. A., & Ting, L. (2001). Intimacy dysfunction and trauma symptomatology: Long-term correlates of different types of child abuse. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14, 63–79.

- De Young, A. C., Kenardy, J. A., & Cobham, V. E. (2011). Trauma in early childhood: A neglected population. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(3), 231–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0094-3

- Doi, S., Fujiwara, T., & Isumi, A. (2021). Association between maternal adverse childhood experiences and mental health problems in offspring: An intergenerational study. Development and Psychopathology, 33(3), 1041–1058. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420000334

- Du, Y., Kou, J., & Coghill, D. (2008). The validity, reliability and normative scores of the parent, teacher and self report versions of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire in China. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-2-1

- Ducharme, J., Koverola, C., & Battle, P. (1997). Intimacy development: The influence of abuse and gender. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 12(4), 590–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626097012004007

- Dunifon, R., & Bajracharya, A. (2012). The role of grandparents in the lives of youth. Journal of Family Issues, 33(9), 1168–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12444271

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

- Fu, C., Niu, H., & Wang, M. (2019). Parental corporal punishment and children’s problem behaviors: The moderating effects of parental inductive reasoning in China. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.01.028

- Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2016). Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000191

- Gleason, M. M., Goldson, E., Yogman, M. W., Lieser, D., DelConte, B., Donoghue, E., Earls, M., Glassy, D., McFadden, T., Mendelsohn, A., Scholer, S., Takagishi, J., Vanderbilt, D., Williams, P. G., Yogman, M., Bauer, N., Gambon, T. B., Lavin, A., Lemmon, K. M., … Voigt, R. G. (2016). Addressing early childhood emotional and behavioral problems. Pediatrics, 138(6). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3025

- Goh, E. C. (2006). Raising the precious single child in urban China-an intergenerational joint mission between parents and grandparents. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 4(3), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1300/J194v04n03_02

- Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015

- Hails, K. A., Reuben, J. D., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., & Wilson, M. N. (2018). Transactional associations among maternal depression, parent–child coercion, and child conduct problems during early childhood. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(sup1), S291–S305. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1280803

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford publications.

- Henry, B., Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Langley, J., & Silva, P. A. (1994). On the “remembrance of things past”: a longitudinal evaluation of the retrospective method. Psychological Assessment, 6(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.92

- Hoang, N. P. T., Haslam, D., & Sanders, M. (2020). Coparenting conflict and cooperation between parents and grandparents in Vietnamese families: The role of grandparent psychological control and parent–grandparent communication. Family Process, 59(3), 1161–1174. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12496

- Iyengar, U., Kim, S., Martinez, S., Fonagy, P., & Strathearn, L. (2014). Unresolved trauma in mothers: intergenerational effects and the role of reorganization. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 98225.

- Jalapa, K., Wu, Q., Tawfiq, D., Han, S., Lee, C. R., & Pocchio, K. (2023). Multigenerational homes buffered behavioral problems among children of latinx but not white non-latinx mothers. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 1–15.

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., Walters, E. E., & Zaslavsky, A. M. (2002). Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291702006074

- Lê-Scherban, F., Wang, X., Boyle-Steed, K. H., & Pachter, L. M. (2018). Intergenerational associations of parent adverse childhood experiences and child health outcomes. Pediatrics, 141(6), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-4274

- Leung, C., & Fung, B. (2014). Non-custodial grandparent caregiving in Chinese families: Implications for family dynamics. Journal of Children’s Services, 9(4), 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-04-2014-0026

- Linde-Krieger, L., & Yates, T. M. (2018). Mothers' history of child sexual abuse and child behavior problems: The mediating role of mothers' helpless state of mind. Child maltreatment, 23(4), 376–386.

- Luo, S., Chen, D., Li, C., Lin, L., Chen, W., Ren, Y., Zhang, Y., Xing, F., & Guo, V. Y. (2023). Maternal adverse childhood experiences and behavioral problems in preschool offspring: The mediation role of parenting styles. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-022-00552-0

- Luo, Y., LaPierre, T. A., Hughes, M. E., & Waite, L. J. (2012). Grandparents providing care to grandchildren. Journal of Family Issues, 33(9), 1143–1167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12438685

- Luo, Y., Qi, M., Huntsinger, C. S., Zhang, Q., Xuan, X., & Wang, Y. (2020). Grandparent involvement and preschoolers’ social adjustment in Chinese three-generation families: Examining moderating and mediating effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 105057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105057

- Ma, C., Shi, J., Li, Y., Wang, Z., & Tang, C. (2011). Family change in urban areas of China: Main trends and latest findings. Sociological Studies, 25(2), 182–216 (in Chinese).

- Madigan, S., Wade, M., Plamondon, A., Maguire, J. L., & Jenkins, J. M. (2017). Maternal adverse childhood experience and infant health: Biomedical and psychosocial risks as intermediary mechanisms. The Journal of Pediatrics, 187, 282–289.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.052

- Manyema, M., Norris, S. A., & Richter, L. M. (2018). Stress begets stress: The association of adverse childhood experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5767-0

- McDonald, S. W., Madigan, S., Racine, N., Benzies, K., Tomfohr, L., & Tough, S. (2019). Maternal adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and child behaviour at age 3: The all our families community cohort study. Preventive Medicine, 118, 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.013

- McLaughlin, K. A., Sheridan, M. A., & Lambert, H. K. (2014). Childhood adversity and neural development: Deprivation and threat as distinct dimensions of early experience. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 47, 578–591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012

- Merrick, M. T., Ports, K. A., Ford, D. C., Afifi, T. O., Gershoff, E. T., & Grogan-Kaylor, A. (2017). Unpacking the impact of adverse childhood experiences on adult mental health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.016

- Neaverson, A., Murray, A. L., Ribeaud, D., & Eisner, M. (2020). A longitudinal examination of the role of self-control in the relation between corporal punishment exposure and adolescent aggression. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(6), 1245–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01215-z

- Park, M., & Chesla, C. (2007). Revisiting Confucianism as a conceptual framework for Asian family study. Journal of Family Nursing, 13(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840707304400

- Petruccelli, K., Davis, J., & Berman, T. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences and associated health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 97, 104127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104127

- Poblete, A. T., & Gee, C. B. (2018). Partner support and grandparent support as predictors of change in coparenting quality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2295–2304.

- Racine, N., Plamondon, A., Madigan, S., McDonald, S., & Tough, S. (2018). Maternal adverse childhood experiences and infant development. Pediatrics, 141(4), e20172495. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2495

- Rowell, T., & Neal-Barnett, A. (2022). A systematic review of the effect of parental adverse childhood experiences on parenting and child psychopathology. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 15(1), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-021-00400-x

- Rudenstine, S., Espinosa, A., McGee, A. B., & Routhier, E. (2019). Adverse childhood events, adult distress, and the role of emotion regulation. Traumatology, 25(2), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000176

- Schickedanz, A., Halfon, N., Sastry, N., & Chung, P. J. (2018). Parents’ adverse childhood experiences and their children’s behavioral health problems. Pediatrics, 142(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-0023

- Shih, E. W., Ahmad, S. I., Bush, N. R., Roubinov, D., Tylavsky, F., Graff, C., Karr, C. J., Sathyanarayana, S., & LeWinn, K. Z. (2023). A path model examination: Maternal anxiety and parenting mediate the association between maternal adverse childhood experiences and children’s internalizing behaviors. Psychological Medicine, 53(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001203

- Silverstein, M., & Ruiz, S. (2006). Breaking the chain: How grandparents moderate the transmission of maternal depression to their grandchildren. Family Relations, 55(5), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00429.x

- Spieker, S. J., & Bensley, L. (1994). Roles of living arrangements and grandmother social support in adolescent mothering and infant attachment. Developmental Psychology, 30(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.102

- Sroufe, L. A. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & human development, 7(4), 349–367.

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Finkelhor, D., Moore, D. W., & Runyan, D. (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 22(4), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9

- Tabachnick, B., & Fidell, L. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Pearson Education, Inc.

- United Nations. (2022). Database on the household composition and living arrangements of older persons 2022.

- Van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., & Mandel, F. (1993). Complex PTSD: Results of the PTSD field trials for DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Association.

- Vergunst, F., Commisso, M., Geoffroy, M. C., Temcheff, C., Poirier, M., Park, J., Vitaro, F., Tremblay, R., Côté, S., & Orri, M. (2023). Association of childhood externalizing, internalizing, and comorbid symptoms with long-term economic and social outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 6(1), e2249568–e2249568. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.49568

- Viertiö, S., Kiviruusu, O., Piirtola, M., Kaprio, J., Korhonen, T., Marttunen, M., & Suvisaari, J. (2021). Factors contributing to psychological distress in the working population, with a special reference to gender difference. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10560-y

- Wang, M., & Liu, L. (2014). Parental harsh discipline in mainland China: Prevalence, frequency, and coexistence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(6), 1128–1137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.016

- Wang, X., Yin, G., Guo, F., Hu, H., Jiang, Z., Li, S., Shao, Z., & Wan, Y. (2022). Associations of maternal adverse childhood experiences with behavioral problems in preschool children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(21-22), NP20311–NP20330. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211050093

- Wang, Y. S. (2013). An analysis of changes in the Chinese family structure between urban and rural Areas: On the basis of the 2010 National Census data. Social Sciences in China, 12, 60–77 (in Chinese).

- Widom, C. S., Czaja, S. J., Kozakowski, S. S., & Chauhan, P. (2018). Does adult attachment style mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental and physical health outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 533–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.05.002

- World Health Organization. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences international questionnaire (ACE-IQ)[EB/OL]. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en

- Wright, M. O. D., Fopma-Loy, J., & Oberle, K. (2012). In their own words: The experience of mothering as a survivor of childhood sexual abuse. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 537–552. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579412000144

- Xu, X., Xiao, B., Zhu, L., & Li, Y. (2023). The influence of parent-grandparent co-parenting on children’s problem behaviors and its potential mechanisms. Early Education and Development, 34(4), 791–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2022.2073746

- Yoon, Y., Cederbaum, J. A., Mennen, F. E., Traube, D. E., Chou, C. P., & Lee, J. O. (2019). Linkage between teen mother’s childhood adversity and externalizing behaviors in their children at age 11: Three aspects of parenting. Child Abuse & Neglect, 88, 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.12.005

- Zhang, F., & Wu, Y. (2021). Living with grandparents: Multi-generational families and the academic performance of grandchildren in China. Chinese Journal of Sociology, 7(3), 413–443. https://doi.org/10.1177/2057150X211028357

- Zhang, J., Emery, T., & Dykstra, P. (2020). Grandparenthood in China and Western Europe: An analysis of CHARLS and SHARE. Advances in Life Course Research, 45, 100257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2018.11.003

- Zhang, L., Mersky, J. P., Gruber, A. M. H., & Kim, J. Y. (2022). Intergenerational transmission of parental adverse childhood experiences and children’s outcomes: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221126186

- Zhong, J., Wang, T., He, Y., Gao, J., Liu, C., Lai, F., Zhang, L., & Luo, R. (2021). Interrelationships of caregiver mental health, parenting practices, and child development in rural China. Children and Youth Services Review, 121, 105855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105855

- Zhou, C., Chu, J., Wang, T., Peng, Q., He, J., Zheng, W., Liu, D., Wang, X., Ma, H., & Xu, L. (2008). Reliability and validity of 10-item Kessler scale (K10) Chinese version in evaluation of mental health status of Chinese population. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(6), 627–629.

- Zhu, Y., Zhan, S., Anme, T., & Zhang, G. (2023). Maternal adverse childhood experiences and behavioral problems in Chinese preschool children: The moderated mediating role of emotional dysregulation and self-compassion. Child Abuse & Neglect, 141, 106226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2023.106226

- Zhu, Y., Zhang, G., & Anme, T. (2022). Patterns of adverse childhood experiences among Chinese preschool parents and the intergenerational transmission of risk to offspring behavioural problems: Moderating by coparenting quality. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2137913. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2137913