ABSTRACT

Background: Intensive care unit (ICU) admission and invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) are associated with psychological distress and trauma. The COVID-19 pandemic brought with it a series of additional long-lasting stressful and traumatic experiences. However, little is known about comorbid depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Objective: To examine the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and PTSD, and their predictive factors, in COVID-19 critical illness survivors.

Method: Single-centre prospective observational study in adult survivors of COVID-19 with ≥24 h of ICU admission. Patients were assessed one and 12 months after ICU discharge using the depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Davidson Trauma Scale. Differences in isolated and comorbid symptoms of depression and PTSD between patients with and without IMV and predictors of the occurrence and persistence of symptoms of these mental disorders were analysed.

Results: Eighty-nine patients (42 with IMV) completed the 1-month follow-up and 71 (34 with IMV) completed the 12-month follow-up. One month after discharge, 29.2% of patients had symptoms of depression and 36% had symptoms of PTSD; after one year, the respective figures were 32.4% and 31%. Coexistence of depressive and PTSD symptoms accounted for approximately half of all symptomatic cases. Isolated PTSD symptoms were more frequent in patients with IMV (p≤.014). The need for IMV was associated with the occurrence at one month (OR = 6.098, p = .005) and persistence at 12 months (OR = 3.271, p = .030) of symptoms of either of these two mental disorders.

Conclusions: Comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms were highly frequent in our cohort of COVID-19 critical illness survivors. The need for IMV predicted short-term occurrence and long-term persistence of symptoms of these mental disorders, especially PTSD symptoms. The specific role of dyspnea in the association between IMV and post-ICU mental disorders deserves further investigation.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04422444.

HIGHLIGHTS

Clinically significant depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in survivors of COVID-19 critical illness, especially in patients who had undergone invasive mechanical ventilation, were highly frequent, occurred soon after discharge, and persisted over the long term.

Antecedentes: El ingreso en la unidad de cuidados intensivos (UCI) y la ventilación mecánica invasiva (VMI) se asocian con malestar psicológico y trauma. La pandemia de COVID-19 trajo consigo una serie de experiencias estresantes y traumáticas adicionales de larga duración. Sin embargo, se sabe poco sobre la depresión y el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) comórbidos.

Objetivo: Examinar la aparición, coexistencia, y persistencia de síntomas clínicamente significativos de depresión y TEPT, y sus factores predictivos, en supervivientes de enfermedad crítica por COVID-19.

Método: Estudio observacional prospectivo unicéntrico en adultos supervivientes de COVID-19 con ≥24 h de ingreso en UCI. Los pacientes fueron evaluados uno y 12 meses después del alta de UCI mediante la subescala de depresión de la Escala Hospitalaria de Ansiedad y Depresión y la Escala de Trauma de Davidson. Se analizaron las diferencias en los síntomas aislados y comórbidos de depresión y TEPT entre pacientes con y sin VMI y los predictores de la aparición y persistencia de síntomas de estos dos trastornos mentales.

Resultados: Ochenta y nueve pacientes (42 con VMI) completaron el seguimiento de 1 mes y 71 (34 con VMI) completaron el seguimiento de 12 meses. Un mes después del alta, el 29,2% de los pacientes presentaba síntomas de depresión y el 36% presentaban síntomas de TEPT; al cabo de un año, las cifras respectivas eran del 32,4% y el 31%. La coexistencia de síntomas de depresión y TEPT representó aproximadamente la mitad de todos los casos sintomáticos. Los síntomas de TEPT aislados fueron más frecuentes en pacientes con VMI (p≤0,014). La necesidad de VMI se asoció con la aparición al mes (OR = 6,098, p = 0,005) y la persistencia a los 12 meses (OR = 3,271, p = 0,030) de síntomas de cualquiera de estos dos trastornos mentales.

Conclusiones: Los síntomas comórbidos de depresión y TEPT fueron muy frecuentes en nuestra muestra de supervivientes de enfermedad crítica por COVID-19. La necesidad de VMI predijo la aparición a corto plazo y la persistencia a largo plazo de síntomas de estos dos trastornos mentales, especialmente de síntomas de TEPT. El papel específico de la disnea en la asociación entre la VMI y los trastornos mentales tras la UCI merece mayor investigación.

1. Background

Psychological, cognitive and physical alterations are common in survivors of critical illness and are encompassed in what is known as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) (Marra et al., Citation2018). These disturbances are either new onset or are due to worsening of deficits already existing before admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and may become chronic (Herridge & Azoulay, Citation2023). Recently, emphasis has been placed on the need for early identification and long-term follow-up of cognitive sequelae and, in particular, of psychological disorders (Ramnarain et al., Citation2023).

Critically ill patients often suffer a strong emotional impact related to their illness or the ICU environment and certain medical procedures (e.g. facing one's own death, experiencing dyspnea, presenting with delirium, being hooked up to machines) that can be stressful, even traumatic, for some people (Guttormson et al., Citation2023). This can result in psychological disorders such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which often coexist (Jackson et al., Citation2014; Rabiee et al., Citation2016). Compared to depression or PTSD alone, the co-occurrence of these two conditions leads to lower levels of functioning, a delayed response to treatment, a more chronic course (Angelakis & Nixon, Citation2015), and an increased risk of suicide (Oquendo et al., Citation2005).

The need for invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) has been associated with particularly high levels of psychological distress and an increased propensity for traumatic experiences (Demoule et al., Citation2022; Schmidt et al., Citation2011), making this ICU population especially vulnerable to anxiety, depression and PTSD (Worsham et al., Citation2021). Estimates of the prevalence of these disorders fall within the range observed among survivors of natural disasters (Long et al., Citation2014) and people traumatized by war (Mollica, Citation2000), and may be as high as 60%. In this context, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic brought with it a series of long-lasting stressful and traumatic experiences that led to a widespread increase in mental disorders (Santomauro et al., Citation2021; Yuan et al., Citation2021). Indeed, during the first pandemic wave (i.e. from March to July 2020), between one-fifth and one-third of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 required ICU admission and two-thirds of them also required IMV (Ginestra et al., Citation2022).

To date, the occurrence of COVID-19-related anxiety, depression, and PTSD in non-hospitalized patients (Albtoosh et al., Citation2022), non-critically ill hospitalized patients (Mazza et al., Citation2023; Yunitri et al., Citation2022) and critically ill hospitalized patients (Groff et al., Citation2021; Nagarajan et al., Citation2022; Sankar et al., Citation2023; Yang et al., Citation2022; Zürcher et al., Citation2022) has been extensively described in several systematic reviews and meta-analyses. However, in these studies, the data have been analysed for each disorder separately, or by grouping them into a single mental health category, without an in-depth consideration of the specific overlap between depression and PTSD. Furthermore, the limited evidence available regarding comorbid depression and PTSD in survivors of COVID-19 critical illness does not always directly address its occurrence, persistence, and predictive factors at the same time, nor does it reflect the specific long-term impact of the need for IMV (Banno et al., Citation2021; Chean et al., Citation2023; Maley et al., Citation2022; Nanwani-Nanwani et al., Citation2022; Vlake et al., Citation2021). Consequently, the current data are partial and the full spectrum of mental health sequelae in this clinical population is not yet known.

Therefore, we conducted a longitudinal study spanning one year of follow-up and two assessment time points (one and 12 months after ICU discharge) with a twofold objective: first, to compare the occurrence, co-occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and PTSD between a group of COVID-19 ICU survivors who had undergone IMV and a group of COVID-19 ICU survivors who had not undergone this treatment; and, second, to explore sociodemographic and clinical predictors of the occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of either of these two mental disorders.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

This study is part of a larger prospective longitudinal research project conducted in Catalonia, Spain, between 13 March 2020, and 2 February 2022. Participants were recruited among critically ill patients admitted to the medical/surgical ICU of the Parc Taulí University Hospital in Sabadell, Barcelona, between 13 March 2020, and 21 January 2021. Follow-up covered the 12 consecutive months following ICU discharge, from 29 May 2020, to 2 February 2022. The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Parc Taulí University Hospital (Ref. 2020/577; 3 May 2020) and registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT04422444; 9 June 2020). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this study comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Some data not related to the objectives of this study have been published elsewhere (Fernández-Gonzalo et al., Citation2021; Godoy-González et al., Citation2023).

2.2. Participants and procedure

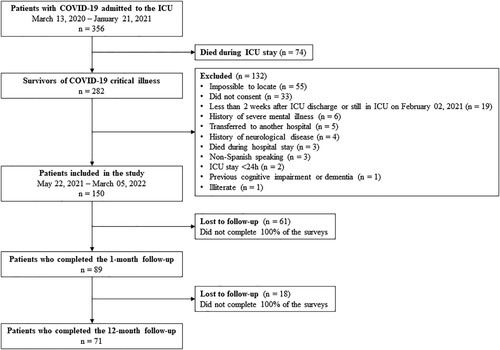

All critically ill patients ≥18 years old who were COVID-19 survivors and had been admitted to the ICU for ≥24 h, regardless of the need for IMV, were eligible to participate in the study (). SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction. Patients with previous cognitive impairment or dementia, history of neurological disease (including brain damage at admission), history of severe mental illness (including substance use disorder and intellectual disability), non-Spanish speakers, or with a life expectancy <12 months were excluded. Data on previous cognitive impairment or dementia and on history of neurological disease or severe mental illness according to DSM-5 criteria were extracted from medical records. To rule out increased risk of previous cognitive impairment or dementia in patients ≥65 years, the Short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (S-IQCODE) (Morales González et al., Citation1992) was administered to a family member by telephone, and patients with scores >57 were excluded. This double check in patients aged ≥65 years (i.e. medical history review and administration of the S-IQCODE) to ensure the absence of mild cognitive impairment or incipient dementia not yet recorded in the medical history has already been used in previous studies in critically ill patients (Fernández-Gonzalo et al., Citation2020; Godoy-González et al., Citation2023; Navarra-Ventura et al., Citation2021).

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study. Of the 365 patients with COVID-19 admitted to the ICU, 282 survived critical illness. Of these, 150 were included in the study. Eighty-nine patients completed the 1-month follow-up and 71 completed the 12-month follow-up. ICU, Intensive care unit; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019.

Eligible patients were screened daily by an ICU research nurse and enrolled between three to five weeks after discharge, once witnessed telephone informed consent to take part had been obtained. Patients were assessed remotely one month and 12 months after ICU discharge using a digital platform of self-administered questionnaires and questions, which were specifically designed by a multidisciplinary team of experts in critical care, rehabilitation medicine, and neuropsychology with extensive experience in PICS-related sequelae. This digital platform was created to overcome the difficulties of face-to-face assessment caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and was funded by the Government of Spain. All patients were asked to complete the questionnaires and expert-made questions remotely through the digital platform, within 15 days of receiving a digital prompt (i.e. a message with instructions on how to access and use the digital platform). In those patients who did not have access to an electronic device (e.g. mobile phone, tablet, personal computer, laptop) or did not have internet access, the questionnaires and expert-made questions were administered by telephone by a neuropsychologist.

2.3. Sociodemographic and clinical variables

Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records upon agreement to participate, including age, sex, education, COVID-19 pandemic wave, length of hospital and ICU stay, comorbidities at ICU admission (Charlson Comorbidity Index, CCI), severity of illness at ICU admission (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation-II, APACHE-II), need for IMV during ICU stay, and destination at hospital discharge. Delirium during ICU stay was extracted from patients’ medical records by considering the following assumptions: a medical report of delirium, the presence of an episode of agitation, and/or the prescription of antipsychotic/neuroleptic drugs (Godoy-González et al., Citation2023). Additionally, we assessed patients’ cognitive reserve by administering the Cognitive Reserve Questionnaire (CRQ) (range 0–25) by telephone. Higher CRQ scores indicate greater cognitive reserve (i.e. greater brain resistance to neuropsychological insults) (Rami et al., Citation2011).

2.4. Mental health variables

Patients were administered two self-reported mental health questionnaires with good test-retest reliability and internal consistency (all ≥0.86): the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Quintana et al., Citation2003; Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) and the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) (Davidson et al., Citation1997). The HADS consists of 14 items in two subscales, with seven items assessing anxiety symptoms and seven assessing depressive symptoms, with a cut-off score for clinically significant symptoms of ≥8 for each subscale (range 0–21). The DTS consists of 17 items assessing PTSD symptoms, with a cut-off score for clinically significant symptoms of ≥27 (range 0–136). For the purposes of this study, only the HADS-Depression (HADS-D) subscale and the DTS were considered.

2.5. Data pre-processing

To help reduce collinearity in the regression models, the following ratios were calculated: (1) length of ICU stay divided by length of hospital stay, and (2) duration of IMV divided by length of ICU stay. This method of data correction was made by consensus among the authors and has already been used in a previous study in critically ill patients (Fernández-Gonzalo et al., Citation2020).

To explore the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and PTSD, the following categories of mental disorders were considered: (1) isolated depressive symptoms (HADS-D score >7), (2) isolated PTSD symptoms (DTS score >26), and (3) comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms (HADS-D score >7 and DTS score >26). In turn, to assess predictors of the occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of either of these two mental disorders, the following constructs were calculated: (1) occurrence at one month (i.e. a clinically significant HADS-D and/or DTS score at 1-month follow-up), (2) occurrence at 12 months (i.e. a clinically significant HADS-D and/or DTS score at 12-month follow-up in asymptomatic patients at 1-month follow-up), and (3) persistence at 12 months (i.e. a clinically significant HADS-D and/or DTS score at both follow-up visits). All of these categories and constructs are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive, and are based on a previous longitudinal study that examined psychiatric symptoms in war-traumatized individuals (Mollica, Citation2001).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed with SPSS v28. Statistical significance was set at p <.05. Data normality was checked using skewness, kurtosis, and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Results are shown as mean (standard deviation, SD), median [range] or number (%). Differences in sociodemographic, clinical, and mental health variables between patients with and without IMV were analysed by the Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and by the chi-square (X2) test for categorical variables. Descriptive statistics were used to present the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD during the 1-year follow-up. Backward binomial logistic regressions were used to analyse predictors of the occurrence (at one and 12 months) and persistence (at 12 months) of clinically significant symptoms of either of these two mental disorders (Mollica, Citation2001). Predictive factors were selected based on their potential to influence mental health outcomes according to previous literature reports in ICU patients (Lee et al., Citation2020) and the authors’ clinical judgment.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Eighty-nine patients (47.2% with IMV) completed the 1-month follow-up and 71 (47.9% with IMV) were re-evaluated 12 months later. shows the sociodemographic, clinical, and mental health characteristics of patients who completed the 1-month follow-up, overall and by IMV group. Patients who had undergone IMV were mostly male, were recruited mainly during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave, with more severe illness at ICU admission (APACHE-II), longer hospital and ICU length of stay, higher frequency of delirium, and greater occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of mental disorders (particularly PTSD symptoms), than patients who had not undergone IMV. Similar results were observed among patients who completed both follow-up visits (Tables S1 and S2, see Supplemental online material).

Table 1. Sociodemographic, clinical, and mental health data of patients who completed the 1-month follow-up

During the study, 18 (20.2%) patients were lost to follow-up, eight (44.4%) of whom had undergone IMV and 10 (55.6%) had not. Discontinuation was more frequent among patients with fewer medical comorbidities at ICU admission (CCI, 1 [0–4] vs. 2 [0–6], p = .044) and among patients with comorbid symptoms of depression and PTSD at 1-month follow-up (n = 8/18, 44.4% vs. n = 12/71, 16.9%, p = .012). No other significant differences were found between patients who completed both follow-ups and those who completed only the 1-month follow-up.

3.2. Clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in the whole sample

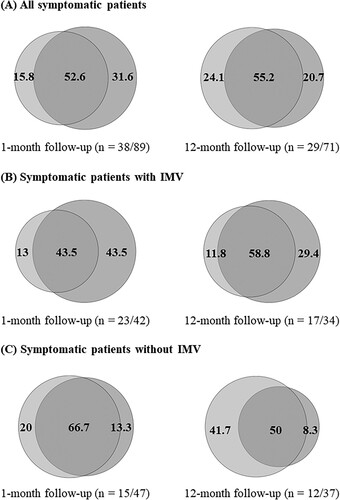

(A) shows the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in patients who completed both follow-up visits. While 83.7% (n = 36/43) of asymptomatic patients at one month were still symptom-free at 12 months, 78.6% (n = 22/28) of symptomatic patients at one month were still symptomatic at 12 months. Among patients with isolated depressive symptoms at one month (n = 5), one (20%) was symptom-free at 12 months, another (20%) still had isolated depressive symptoms, and three (60%) developed comorbid PTSD symptoms. Among patients with isolated PTSD symptoms at one month (n = 11), three (27.3%) were symptom-free at 12 months, four (36.4%) still had isolated PTSD symptoms, and two (18.2%) developed comorbid depressive symptoms. Among patients with comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms at one month (n = 12), two (16.7%) were symptom-free at 12 months and nine (75%) still had symptoms of both mental disorders. (A) and Table S2 show more details on the percentages of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD among symptomatic patients.

Figure 2. Percentages (%) of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD among symptomatic patients, overall and by IMV group. Depressive symptoms only (light grey, left area), PTSD symptoms only (medium grey, right area) and comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms (dark grey, middle area). Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. IMV, Invasive mechanical ventilation, PTSD, Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Table 2. Occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant depressive and/or PTSD symptoms over a 12-month period in patients who completed 1- and 12-month follow-ups.

3.3. Comparison of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD between patients with and without IMV

The occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in patients with and without IMV who completed both follow-up visits are described in (B) and (C) respectively. The frequency of asymptomatic patients at one month who were still symptom-free at 12 months was similar between those with and without IMV (n = 15/17, 88.2% vs. n = 21/26, 80.8%). In contrast, the frequency of symptomatic patients at one month who were still symptomatic at 12 months was higher in patients with IMV than in patients without IMV (n = 15/17, 88.2% vs. n = 7/11, 63.6%). One month after discharge, depressive symptoms with and without comorbid PTSD symptoms were present in 31% (n = 13/42) of patients with IMV and 27.7% (n = 13/47) of patients without IMV, whereas PTSD symptoms with and without comorbid depressive symptoms were present in 47.6% (n = 20/42) of patients with IMV and 25.5% (n = 12/47) of patients without IMV. One year later, 35.3% (n = 12/34) of patients with IMV and 29.7% (n = 11/37) of patients without IMV still had depressive symptoms with and without comorbid PTSD symptoms, whereas 44.1% (n = 15/34) of patients with IMV and 18.9% (n = 7/37) of patients without IMV still had PTSD symptoms with and without comorbid depressive symptoms. Further details on the percentages of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in symptomatic patients with and without IMV are shown in (B) and (C) respectively and in Table S2.

3.4. Clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in patients with IMV

(B) shows the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in patients with IMV who completed both follow-up visits. Among patients with isolated depressive symptoms at one month (n = 3), one (33.3%) was symptom-free at 12 months and two (66.7%) developed comorbid PTSD symptoms. Among patients with isolated PTSD symptoms at one month (n = 9), one (11.1%) was symptom-free at 12 months, four (44.4%) still had isolated PTSD symptoms, and two (22.2%) developed comorbid depressive symptoms. All (n = 5, 100%) patients with comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms at one month still had symptoms of both mental disorders at 12 months. (B) and Table S2 show more details on the percentages of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD among symptomatic patients with IMV.

3.5. Clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in patients without IMV

(C) shows the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD in patients without IMV who completed both follow-up visits. Among patients with isolated depressive symptoms at one month (n = 2), one (50%) still had symptoms of isolated depression at 12 months and another (50%) developed comorbid PTSD symptoms. All (n = 2, 100%) patients with isolated PTSD symptoms at one month were symptom-free at 12 months. Among patients with comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms at one month (n = 7), two (28.6%) were symptom-free at 12 months and four (57.1%) still had symptoms of both mental disorders. (C) and Table S2 show more details on the percentages of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD among symptomatic patients without IMV.

The occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD including patients lost to follow-up are shown in Table S3 (see Supplemental online material).

3.6. Predictors of the occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD

shows the final backward binomial logistic regression models for the occurrence (at one and 12 months) and persistence (at 12 months) of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder, including depressive and/or PTSD symptoms. Predictive factors were age, sex (male, female), cognitive reserve (CRQ), COVID-19 pandemic wave (first, subsequent), ICU length of stay (ratio), IMV during ICU stay (yes, no) and delirium during ICU stay (yes, no). IMV during ICU stay was considered categorical and not continuous, as neither the duration of IMV in days nor the ratio were significant as predictive factors in screening analyses.

Table 3. Predictors of the occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder, including depressive and/or PTSD symptoms

The need for IMV during ICU stay was the only significant factor associated with the occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder at one month (OR = 6.089, 95% CI: 1.717–21.655, p = .005) (, A) and with its persistence at 12 months (OR = 3.217, 95% CI: 1.125–9.551, p = .030) (, C). While female sex showed a positive trend toward the occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder at one month, patients admitted to the ICU during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave showed the opposite trend. None of the variables were significant for the occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder at 12 months in asymptomatic patients at one month (, B).

Details on the iterative backward binomial logistic regression models are given in Tables S4, S5 and S6 (see Supplemental online material).

4. Discussion

This is one of the few longitudinal studies in COVID-19 ICU survivors that has specifically explored the occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD and their predictive factors, placing particular emphasis on the impact of the need for IMV. As reported in previous research involving COVID-19 critical illness survivors (Banno et al., Citation2021; Chean et al., Citation2023; Maley et al., Citation2022; Nanwani-Nanwani et al., Citation2022; Vlake et al., Citation2021), we found a high occurrence, co-occurrence, and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of these mental disorders throughout the study. These symptoms, particularly of PTSD with or without comorbid depressive symptomatology, were more frequent in patients who had undergone IMV. In fact, the need for IMV proved to be the only predictor of the occurrence at one month and persistence at 12 months of clinically significant symptoms of either of these two mental disorders.

One month after ICU discharge, 6.7% of patients had clinically significant symptoms of isolated depression, 13.5% of isolated PTSD and 22.5% of comorbid depression and PTSD. One year later, 9.9%, 8.5% and 22.5% of patients still had clinically significant symptoms of these mental disorders. On the one hand, our results are at odds with those of a large longitudinal investigation conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e. the BRAIN-ICU study), which found a prevalence of depression of 37% at three months and 33% at 12 months, a prevalence of PTSD of 7% at three and 12 months, and a co-occurrence of depression and PTSD of 6% at three and 12 months (Jackson et al., Citation2014). These differences between studies could be attributed to the use of different mental health questionnaires and diagnostic criteria, or to the characteristics of the cohorts (i.e. general ICU survivors in their study vs. COVID-19 survivors in ours) (Guttormson et al., Citation2023). On the other hand, our findings are consistent with those of a large multicentre study, also conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic in general ICU survivors, but in which the HADS-D and a PTSD questionnaire equivalent to the DTS were used (Hatch et al., Citation2018). More importantly, our results are in line with a systematic review and meta-analysis of patients affected by COVID-19 or other coronaviruses, which found the frequency of depressive and PTSD symptoms after hospitalization or ICU admission to be 33.2% (95% CI, 19.8% to 50.1%) and 38.8% (95% CI, 30.9% to 47.3%) respectively (Ahmed et al., Citation2020). In our study, the cumulative frequency of clinically significant depressive and PTSD symptoms were 29.2% and 36% at one month and 32.4% and 31% at 12 months.

We also found that only 16.3% of asymptomatic patients at one month had developed clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder one year later, whereas 78.6% of symptomatic patients at one month still had clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder after this period. Given that the occurrence of clinically significant depressive and/or PTSD symptoms remained relatively stable during the 1-year follow-up, with no factor explaining their occurrence at 12 months in patients asymptomatic at one month, these results suggest that the occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of either of these two mental disorders shortly after ICU discharge would be primarily related to events occurring during admission (e.g. the need for IMV). In contrast, significant variations were observed within the three symptomatic categories, insofar as approximately one-third of patients with clinically significant isolated depressive or PTSD symptoms at one month had developed clinically significant comorbid symptoms of the other mental disorder a year later. This is consistent with previous studies in other clinical populations which showed that, after exposure to trauma (e.g. undergoing IMV), PTSD is often comorbid with depression at rates ranging from 30% to 50% (Flory & Yehuda, Citation2015), and also with other studies conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in general ICU survivors which showed that PTSD symptoms frequently coexist with depression (Hatch et al., Citation2018; Jackson et al., Citation2014), especially in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Huang et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, three-quarters of patients with clinically significant comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms at one month still had clinically significant symptoms of both mental disorders a year later; thus, this condition was the most frequent mental health sequela in our study, accounting for approximately half of all short- and long-term symptomatic cases.

However, clear differences in the occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of these mental disorders were found between patients with and without IMV. In patients with IMV, clinically significant symptoms of isolated depression, isolated PTSD, and comorbid depression and PTSD were observed in 7.1%, 23.8% and 23.8% of individuals at one month and in 5.9%, 14.7% and 29.4% of individuals one year later. In patients without IMV, clinically significant symptoms of these mental disorders were only observed in 6.4%, 4.3% and 21.3% of individuals at one month and in 13.5%, 2.7% and 16.2% of individuals one year later. Of the symptomatic patients at one month, only 11.8% of those in the IMV group, but up to 36.4% of those in the non-IMV group, were symptom-free a year later, indicating that psychological sequelae, particularly PTSD symptoms, were more frequent and persistent in patients who had required IMV during ICU admission. Meanwhile, of the patients with clinically significant isolated symptoms of depression or PTSD at one month, up to 33.3% of those who had undergone IMV, but only 25% of those who had not undergone IMV, developed clinically significant comorbid symptoms of the other mental disorder one year later. Furthermore, all patients who had undergone IMV, but only 57.1% of those who had not undergone IMV among those with clinically significant comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms at one month still had clinically significant symptoms of both mental disorders one year later. This is consistent with previous literature reports in general ICU survivors (Hatch et al., Citation2018; Jackson et al., Citation2014) and ARDS patients (Huang et al., Citation2016) which showed that IMV is a risk factor for worse mental health outcomes after discharge.

In our study, the need for IMV was found to be the main factor conditioning the short-term occurrence and long-term persistence of clinically significant symptoms of depression and/or PTSD. Specifically, we observed that patients who had undergone IMV during the ICU stay had a 6-fold increased risk of clinically significant symptom occurrence one month after discharge and a 3-fold increased risk of clinically significant symptom persistence one year later. Previous studies in patients admitted to the ICU found that dyspnea (i.e. breathlessness or shortness of breath) is frequent and intense in mechanically ventilated patients and is associated with delayed extubation (Schmidt et al., Citation2011). Especially when combined with high respiratory drive and excessive respiratory effort, it seems to predict a relapse of respiratory failure during weaning from IMV (Esnault et al., Citation2020), making patients more prone to air hunger (i.e. the most distressing form of dyspnea) and increasing the risk of traumatic experiences and ultimately mental disorders, particularly PTSD (Demoule et al., Citation2022; Worsham et al., Citation2021). Other noxious factors, besides dyspnea, that may also be stressful or traumatic for patients undergoing IMV are the endotracheal tube, the tracheostomy cannula, or the need for deeper suctioning itself. Although tentative, this is a possible explanation for our results that warrants further investigation.

Our finding that women may be more prone than men to the occurrence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder one month after discharge is in agreement with previous reports (Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Citation2021). Backward regression models also showed that patients admitted during the first COVID-19 pandemic wave (i.e. March through July 2020) might be less likely to develop clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder shortly after discharge than patients admitted during subsequent COVID-19 pandemic waves (i.e. August 2020 onwards). One possible explanation could be that during the first pandemic wave patients were not yet fully aware of the dangers associated with COVID-19 disease and the strong emotional impact associated with ICU admission and the need for IMV, compared to patients in later pandemic waves, who may have become sensitized to it due to the massive and constant information disseminated by the media and internet about the devastating consequences of COVID-19 disease, mainly in case of severe or critical illness. Indeed, there is evidence that certain mental health sequelae, such as those related to trauma, can manifest in the long term and that cumulative stress and anxiety sustained over time are potential triggers for the onset of PTSD (Long et al., Citation2014). A previous study analyzing the trajectories of different mental health components during the COVID-19 pandemic also obtained results consistent with this hypothesis (Bayes-Marin et al., Citation2023). Nevertheless, this is at odds with the fact that in our study we did not find a significant effect of this variable (i.e. of the COVID-19 pandemic wave) in models assessing predictors of the occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder at 12 months, and so caution is advised when interpreting this result.

As clinical implications, our results highlight that patients with IMV are priority candidates for early psychological interventions during ICU stay, such as neurocognitive stimulation and relaxation using virtual reality techniques. Interventions of this kind have been shown to be useful in reducing stress/anxiety during ICU admission and preventing mental health sequelae after discharge (Martí-Hereu et al., Citation2023; Navarra-Ventura et al., Citation2021). They may also help reduce dyspnea, alleviate distress during weaning from IMV and thus lower the risk of a traumatic experience (De Peuter et al., Citation2004). Finally, our results strengthen the need for early identification and long-term follow-up of mental disorders in ICU survivors, both by critical care and PICS specialists and primary care professionals (Herridge & Azoulay, Citation2023; Ramnarain et al., Citation2023).

This study is not without limitations. During the pandemic, ICUs were overloaded with COVID-19 patients, so we did not have a control group of non-COVID-19 critically ill patients. In addition, the lack of data from non-critically ill COVID-19 patients limits the generalizability of our results. Some important IMV-related data, such as medication doses and SOFA (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment), were not accurately recorded in the medical records due to the emergency situation. Therefore, it may not be IMV per se, but IMV plus all its associated factors (e.g. dyspnea, sedation, organ failure) that is the main predictor of the occurrence and persistence of clinically significant symptoms of a mental disorder after ICU discharge. Also due to the pandemic context, mental health assessments were based on self-reports rather than direct clinical assessments, and so the data on clinically significant depressive and/or PTSD symptoms should be considered a measure of screening for the disorder (or a probable case), but not a definitive diagnosis. We also did not collect information on possible subsyndromal psychiatric disorders prior to ICU admission, possible negative experiences in the ICU related or unrelated to delirium, or possible stressful events during the 12-month follow-up, such as new hospital admissions or personal losses during the pandemic, which some studies have linked to the development of mental disorders in survivors of critical illness (Lee et al., Citation2020). Finally, an attrition rate of 20.2% was observed, and dropouts were especially pronounced among patients with fewer medical comorbidities at the time of ICU admission and with clinically significant comorbid symptoms of depression and PTSD at the 1-month follow-up. One possible explanation for why these patients may be more likely to be lost to follow-up would be avoidance of the discomfort or emotional distress associated with having to go to a hospital, remembering their ICU admission, or thinking about their critical illness. Indeed, avoidance is a key symptom of acute stress disorder or PTSD widely described in previous literature (Maercker et al., Citation2022). Consequently, it is possible that the rates of clinically significant comorbid depressive and PTSD symptoms, especially in patients with fewer medical comorbidities, are higher than our results show. In any case, and despite the relatively small sample size, the longitudinal design lends value and robustness to our results. In addition, the online methodology used (i.e. the digital platform for data collection) often provides more reliable information on certain sensitive mental health-related topics than face-to-face interviews (Tourangeau & Yan, Citation2007). This data collection approach has also been routinely used in the evaluation of COVID-19 patients during the pandemic, which allows and facilitates comparisons between studies.

5. Conclusions

In summary, approximately 40% of the COVID-19 ICU survivors in our cohort developed clinically significant symptoms of a severe mental disorder during the 12 months following discharge. The coexistence of clinically significant depressive and PTSD symptoms was high throughout the study, occurring soon after ICU discharge and persisting long-term. Importantly, clinically significant PTSD symptoms were the most frequent mental health sequelae in patients who had undergone IMV, a medical procedure that is often described as a stressful or even traumatic experience. In fact, the need for IMV during the ICU stay was revealed to be the main risk factor for short-term occurrence and long-term persistence of clinically significant symptoms of either of these two mental disorders. Future research should study the specific role that dyspnea may play in the association between the need for IMV and post-ICU psychological disorders, PTSD in particular.

Supplemental_online_material_revised.docx

Download MS Word (45.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Michael Maudsley for his invaluable support in editing the manuscript and the patients who participated in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Guillem Navarra-Ventura ([email protected]), upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed H., Patel K., Greenwood D., Halpin S., Lewthwaite P., Salawu A., Eyre L., Breen A., O'Connor R., Jones A., & Sivan M. (2020). Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or ICU admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 52(5), jrm00063. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2694

- Albtoosh, A. S., Toubasi, A. A., Al Oweidat, K., Hasuneh, M. M., Alshurafa, A. H., Alfaqheri, D. L., & Farah, R. I. (2022). New symptoms and prevalence of postacute COVID-19 syndrome among nonhospitalized COVID-19 survivors. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 16921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21289-y

- Angelakis, S., & Nixon, R. D. V. (2015). The comorbidity of PTSD and MDD: Implications for clinical practice and future research. Behaviour Change, 32(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2014.26

- Banno, A., Hifumi, T., Takahashi, Y., Soh, M., Sakaguchi, A., Shimano, S., Miyahara, Y., Isokawa, S., Ishii, K., Aoki, K., Otani, N., & Ishimatsu, S. (2021). One-year outcomes of postintensive care syndrome in critically Ill coronavirus disease 2019 patients: A single institutional study. Critical Care Explorations, 3(12), e0595. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000595

- Bayes-Marin, I., Cabello-Toscano, M., Cattaneo, G., Solana-Sánchez, J., Fernández, D., Portellano-Ortiz, C., Tormos, J. M., Pascual-Leone, A., & Bartrés-Faz, D. (2023). COVID-19 after two years: Trajectories of different components of mental health in the Spanish population. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32, e19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796023000136

- Chean, D., Benarroch, S., Pochard, F., Kentish-Barnes, N., Azoulay, É., Resche-Rigon, M., Megarbane, B., Reuter, D., Labbé, V., Cariou, A., Géri, G., Meersch, G., Kouatchet, A., Guisset, O., Bruneel, F., Reignier, J., Souppart, V., Barbier, F., Argaud, L., … Biard, L. (2023). Mental health symptoms are not correlated with peripheral inflammatory biomarkers concentrations in COVID-19-ARDS survivors. Intensive Care Medicine, 49(1), 109–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06936-2

- Davidson, J. R. T., Book, S. W., Colket, J. T., Tupler, L. A., Roth, S., David, D., Hertzberg, M., Mellman, T., Beckham, J. C., Smith, R. D., Davidson, R. M., Katz, R., & Feldman, M. E. (1997). Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004229

- De Peuter, S., Van Diest, I., Lemaigre, V., Verleden, G., Demedts, M., & Van den Bergh, O. (2004). Dyspnea: The role of psychological processes. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(5), 557–581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.05.001

- Demoule, A., Hajage, D., Messika, J., Jaber, S., Diallo, H., Coutrot, M., Kouatchet, A., Azoulay, E., Fartoukh, M., Hraiech, S., Beuret, P., Darmon, M., Decavèle, M., Ricard, J.-D., Chanques, G., Mercat, A., Schmidt, M., Similowski, T., Faure, M., … Michelin, F. (2022). Prevalence, intensity, and clinical impact of dyspnea in critically Ill patients receiving invasive ventilation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 205(8), 917–926. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202108-1857OC

- Esnault, P., Cardinale, M., Hraiech, S., Goutorbe, P., Baumstrack, K., Prud'homme, E., Bordes, J., Forel, J.-M., Meaudre, E., Papazian, L., & Guervilly, C. (2020). High respiratory drive and excessive respiratory efforts predict relapse of respiratory failure in critically Ill patients with COVID-19. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 202(8), 1173–1178. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202005-1582LE

- Fernández-Gonzalo, S., Navarra-Ventura, G., Bacardit, N., Gomà Fernández, G., de Haro, C., Subirà, C., López-Aguilar, J., Magrans, R., Sarlabous, L., Aquino Esperanza, J., Jodar, M., Rué, M., Ochagavía, A., Palao, D. J., Fernández, R., & Blanch, L. (2020). Cognitive phenotypes 1 month after ICU discharge in mechanically ventilated patients: A prospective observational cohort study. Critical Care, 24(1), 618. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03334-2

- Fernández-Gonzalo, S., Navarra-Ventura, G., Gomà, G., de Haro, C., Espinal Sacristan, C., Fortià Palahí, C., Ridao Sais, N., López-Aguilar, J., Godoy González, M., Oliveras Furriols, L., Miguel Rebanal, N., Subirà, C., Jodar, M., Sarlabous, L., Fernández, R., Ochagavía, A., & Blanch, L. (2021). A follow-up and accompaniment programme to assess the post-intensive care syndrome seqüelae in COVID-19 ICU surviviors: The PICS-COVID19 project. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental, 9(Suppl 1), 40–41.

- Flory, J. D., & Yehuda, R. (2015). Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder: Alternative explanations and treatment considerations. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 17(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2015.17.2/jflory

- Ginestra, J. C., Mitchell, O. J. L., Anesi, G. L., & Christie, J. D. (2022). COVID-19 Critical illness: A data-driven review. Annual Review of Medicine, 73(1), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-042420-110629

- Godoy-González M., Navarra-Ventura G., Gomà G., de Haro C., Espinal C., Fortià C., Ridao N., Miguel Rebanal, N., Oliveras-Furriols L., Subirà C., Jodar M., Santos-Pulpón V., Sarlabous L., Fernández R., Ochagavía A., Blanch L., Roca O., López-Aguilar J., & Fernández-Gonzalo S. (2023). Objective and subjective cognition in survivors of COVID-19 one year after ICU discharge: The role of demographic, clinical, and emotional factors. Critical Care, 27(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-023-04478-7

- Groff D., Sun A., Ssentongo A. E., Ba D. M., Parsons N., Poudel G. R., Lekoubou A., Oh J. S., Ericson J. E., Ssentongo P., & Chinchilli V. M. (2021). Short-term and long-term rates of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. JAMA Network Open, 4(10), e2128568. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.28568

- Guttormson, J. L., Khan, B., Brodsky, M. B., Chlan, L. L., Curley, M. A. Q., Gélinas, C., Happ, M. B., Herridge, M., Hess, D., Hetland, B., Hopkins, R. O., Hosey, M. M., Hosie, A., Lodolo, A. C., McAndrew, N. S., Mehta, S., Misak, C., Pisani, M. A., van den Boogaard, M., & Wang, S. (2023). Symptom assessment for mechanically ventilated patients: Principles and priorities: An official American thoracic society workshop report. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 20(4), 491–498. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202301-023ST

- Hatch, R., Young, D., Barber, V., Griffiths, J., Harrison, D. A., & Watkinson, P. (2018). Anxiety, depression and post traumatic stress disorder after critical illness: A UK-wide prospective cohort study. Critical Care, 21(1), 310. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2223-6.

- Herridge, M. S., & Azoulay, É. (2023). Outcomes after critical illness. New England Journal of Medicine, 388(10), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra2104669

- Huang, M., Parker, A. M., Bienvenu, O. J., Dinglas, V. D., Colantuoni, E., Hopkins, R. O., & Needham, D. M. (2016). Psychiatric symptoms in acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors. Critical Care Medicine, 44(5), 954–965. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001621

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2021). European survey of health in Spain 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2022, from https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176784&menu=resultados&idp=1254735573175

- Jackson, J. C., Pandharipande, P. P., Girard, T. D., Brummel, N. E., Thompson, J. L., Hughes, C. G., Pun, B. T., Vasilevskis, E. E., Morandi, A., Shintani, A. K., Hopkins, R. O., Bernard, G. R., Dittus, R. S., & Ely, E. W. (2014). Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and functional disability in survivors of critical illness in the BRAIN-ICU study: A longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 2(5), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70051-7

- Lee, M., Kang, J., & Jeong, Y. J. (2020). Risk factors for post–intensive care syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian Critical Care, 33(3), 287–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2019.10.004

- Long, A. C., Kross, E. K., Davydow, D. S., & Curtis, J. R. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors of critical illness: Creation of a conceptual model addressing identification, prevention, and management. Intensive Care Medicine, 40(6), 820–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3306-8

- Maercker, A., Cloitre, M., Bachem, R., Schlumpf, Y. R., Khoury, B., Hitchcock, C., & Bohus, M. (2022). Complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Lancet, 400(10345), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00821-2

- Maley, J. H., Sandsmark, D. K., Trainor, A., Bass, G. D., Dabrowski, C. L., Magdamo, B. A., Durkin, B., Hayes, M. M., Schwartzstein, R. M., Stevens, J. P., Kaplan, L. J., Mikkelsen, M. E., & Lane-Fall, M. B. (2022). Six-Month impairment in cognition, mental health, and physical function following COVID-19-associated respiratory failure. Critical Care Explorations, 4(4), e0673. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCE.0000000000000673

- Marra, A., Pandharipande, P. P., Girard, T. D., Patel, M. B., Hughes, C. G., Jackson, J. C., Thompson, J. L., Chandrasekhar, R., Phd, M. A., Ely, E. W., Brummel, N. E., & Wahlen, G. E. (2018). Co-occurrence of post-intensive care syndrome problems among 406 survivors of critical illness. Critical Care Medicine, 46(9), 1393–1401. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000003218

- Martí-Hereu, L., Navarra-Ventura, G., Navas-Pérez, A. M., Férnandez-Gonzalo, S., Pérez-López, F., de Haro-López, C., & Gomà-Fernández, G. (2023). Usage of immersive virtual reality as a relaxation method in an intensive care unit. Enfermería Intensiva (English Ed.) 35(2), 107–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfie.2023.08.005

- Mazza, M. G., Palladini, M., Villa, G., Agnoletto, E., Harrington, Y., Vai, B., & Benedetti, F. (2023). Prevalence of depression in SARS-CoV-2 infected patients: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. General Hospital Psychiatry, 80, 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2022.12.002

- Mollica, R. F. (2000). Waging a new kind of war. Invisible wounds. Scientific American, 282(6), 54–57. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0600-54

- Mollica, R. F. (2001). Longitudinal study of psychiatric symptoms, disability, mortality, and emigration among bosnian refugees. JAMA, 286(5), 546. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.286.5.546

- Morales González, J. M., González-Montalvo, J. I., Del Ser Quijano, T., & Bermejo Pareja, F. (1992). [Validation of the S-IQCODE: The spanish version of the informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly]. Archivos de Neurobiología, 55(6), 262–266.

- Nagarajan, R., Krishnamoorthy, Y., Basavarachar, V., & Dakshinamoorthy, R. (2022). Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of severe COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.040

- Nanwani-Nanwani, K., López-Pérez, L., Giménez-Esparza, C., Ruiz-Barranco, I., Carrillo, E., Arellano, M. S., Díaz-Díaz, D., Hurtado, B., García-Muñoz, A., Relucio, M. Á., Quintana-Díaz, M., Úrbez, M. R., Saravia, A., Bonan, M. V., García-Río, F., Testillano, M. L., Villar, J., García de Lorenzo, A., & Añón, J. M. (2022). Prevalence of post-intensive care syndrome in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 7977. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11929-8

- Navarra-Ventura, G., Gomà, G., de Haro, C., Jodar, M., Sarlabous, L., Hernando, D., Bailón, R., Ochagavía, A., Blanch, L., López-Aguilar, J., & Fernández-Gonzalo, S. (2021). Virtual reality-based early neurocognitive stimulation in critically Ill patients: A pilot randomized clinical trial. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(12), 1260. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11121260

- Oquendo, M., Brent, D. A., Birmaher, B., Greenhill, L., Kolko, D., Stanley, B., Zelazny, J., Burke, A. K., Firinciogullari, S., Ellis, S. P., & Mann, J. J. (2005). Posttraumatic stress disorder comorbid with major depression: Factors mediating the association with suicidal behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(3), 560–566. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.560

- Quintana, J. M., Padierna, A., Esteban, C., Arostegui, I., Bilbao, A., & Ruiz, I. (2003). Evaluation of the psychometric characteristics of the Spanish version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 107(3), 216–221. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00062.x

- Rabiee, A., Nikayin, S., Hashem, M. D., Huang, M., DInglas, V. D., Bienvenu, O. J., Turnbull, A. E., & Needham, D. M. (2016). Depressive symptoms after critical illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical Care Medicine, 44(9), 1744–1753. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001811

- Rami, L., Valls-Pedret, C., Bartrés-Faz, D., Caprile, C., Solé-Padullés, C., Castellvi, M., Olives, J., Bosch, B., & Molinuevo, J. L. (2011). Cognitive reserve questionnaire. Scores obtained in a healthy elderly population and in one with Alzheimer’s disease. Revista de Neurologia, 52(4), 195–201.

- Ramnarain, D., Pouwels, S., Fernández-Gonzalo, S., Navarra-Ventura, G., & Balanzá-Martínez, V. (2023). Delirium-related psychiatric and neurocognitive impairment and the association with post-intensive care syndrome—a narrative review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 147(5), 460–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13534

- Sankar, K., Gould, M. K., & Prescott, H. C. (2023). Psychological morbidity after COVID-19 critical illness. Chest, 163(1), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2022.09.035

- Santomauro, D. F., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B. L., Bertolacci, G. J., Bloom, S. S., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Cogen, R. M., Collins, J. K., … Ferrari, A. J. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

- Schmidt, M., Demoule, A., Polito, A., Porchet, R., Aboab, J., Siami, S., Morelot-Panzini, C., Similowski, T., & Sharshar, T. (2011). Dyspnea in mechanically ventilated critically ill patients*. Critical Care Medicine, 39(9), 2059–2065. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821e8779

- Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin, 133(5), 859–883. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859

- Vlake, J. H., Van Bommel, J., Hellemons, M. E., Wils, E.-J., Bienvenu, O. J., Schut, A. F. C., Klijn, E., Van Bavel, M. P., Gommers, D., & Van Genderen, M. E. (2021). Psychologic distress and quality of life after ICU treatment for coronavirus disease 2019: A multicenter, observational cohort study. Critical Care Explorations, 3(8), e0497.

- Worsham, C. M., Banzett, R. B., & Schwartzstein, R. M. (2021). Dyspnea, acute respiratory failure, psychological trauma, and post-ICU mental health. Chest, 159(2), 749–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2020.09.251

- Yang, T., Yan, M. Z., Li, X., & Lau, E. H. Y. (2022). Sequelae of COVID-19 among previously hospitalized patients up to 1 year after discharge: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection, 50(5), 1067–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-022-01862-3

- Yuan, K., Gong, Y.-M., Liu, L., Sun, Y.-K., Tian, S.-S., Wang, Y.-J., Zhong, Y., Zhang, A.-Y., Su, S.-Z., Liu, X.-X., Zhang, Y.-X., Lin, X., Shi, L., Yan, W., Fazel, S., Vitiello, M. V., Bryant, R. A., Zhou, X.-Y., Ran, M.-S., … Lu, L. (2021). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder after infectious disease pandemics in the twenty-first century, including COVID-19: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Molecular Psychiatry, 26(9), 4982–4998. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01036-x

- Yunitri, N., Chu, H., Kang, X. L., Jen, H.-J., Pien, L.-C., Tsai, H.-T., Kamil, A. R., & Chou, K.-R. (2022). Global prevalence and associated risk factors of posttraumatic stress disorder during COVID-19 pandemic: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 126, 104136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104136

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

- Zürcher, S. J., Banzer, C., Adamus, C., Lehmann, A. I., Richter, D., & Kerksieck, P. (2022). Post-viral mental health sequelae in infected persons associated with COVID-19 and previous epidemics and pandemics: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence estimates. Journal of Infection and Public Health, 15(5), 599–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2022.04.005