ABSTRACT

Background: Comorbidity between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and borderline personality disorder (BPD) is surrounded by diagnostic controversy and although various effective treatments exist, dropout and nonresponse are high.

Objective: By estimating the network structure of comorbid PTSD and BPD symptoms, the current study illustrates how the network perspective offers tools to tackle these challenges.

Method: The sample comprised of 154 patients with a PTSD diagnosis and BPD symptoms, assessed by clinician-administered interviews. A regularised partial correlation network was estimated using the GLASSO algorithm in R. Central symptoms and bridge symptoms were identified. The reliability and accuracy of network parameters were determined through bootstrapping analyses.

Results: PTSD and BPD symptoms largely clustered into separate communities. Intrusive memories, physiological cue reactivity and loss of interest were the most central symptoms, whereas amnesia and suicidal behaviour were least central.

Conclusions: Present findings suggest that PTSD and BPD are two distinct, albeit weakly connected disorders. Treatment of the most central symptoms could lead to an overall deactivation of the network, while isolated symptoms would need more specific attention during therapy. Further experimental, longitudinal research is needed to confirm these hypotheses.

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03833453.

HIGHLIGHTS

A network analysis of PTSD and BPD symptoms.

PTSD and BPD symptoms largely clustered into separate communities.

Intrusive memories, loss of interest and physiological cue reactivity seem valuable treatment targets.

Antecedentes: La comorbilidad entre el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) y el trastorno límite de personalidad (TLP) está rodeado de controversia diagnostica y aunque existen varios tratamientos efectivos, la tasa de abandono y no respuesta son altas.

Objetivo: Al estimar la estructura de red de los síntomas comórbidos de TEPT y TLP, el presente estudio ilustra cómo la perspectiva de red ofrece herramientas para abordar estos desafíos.

Método: La muestra se compuso por 154 pacientes con diagnóstico de TEPT y síntomas de TLP, evaluados mediante entrevistas administradas por el clínico. Se estimo una red de correlación parcial regularizada utilizando el algoritmo GLASSO en R. Se identificaron los síntomas centrales y los síntomas puente. La confiabilidad y precisión de los parámetros de la red se determinaron mediante análisis de Bootstrap.

Resultados: Los síntomas de TEPT y TLP se agruparon en gran medida en dos grupos separados. Los recuerdos intrusivos, la reactividad a las señales fisiológicas y la pérdida del interés fueron los síntomas más centrales, mientras que la amnesia y la conducta suicida fueron las menos centrales.

Conclusiones: Los hallazgos actuales sugieren que el TEPT y TLP son dos trastornos distintos, aunque débilmente conectados. El tratamiento de los síntomas más centrales podría llevar a una desactivación general de la red, mientras que los síntomas aislados requerirían una atención más específica durante la terapia. Se necesitan más investigaciones experimentales y longitudinales para confirmar estas hipótesis.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

Among people diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), approximately 25% have a borderline personality disorder (BPD) (Friborg et al., Citation2013; Pagura et al., Citation2010) while 30% of persons with BPD also have PTSD (Pagura et al., Citation2010). This comorbidity is associated with a poorer quality of life, higher comorbidity with other mental disorders and more suicide attempts compared to patients with only one of these diagnoses (Frías & Palma, Citation2015; Pagura et al., Citation2010). Although various effective, evidence-based interventions for PTSD (Watts et al., Citation2013) and BPD (Cristea et al., Citation2017) exist, dropout and nonresponse rates are high (Barnicot et al., Citation2011; Bradley et al., Citation2005; Imel et al., Citation2013; Woodbridge et al., Citation2022). Results of a recent meta-analysis suggest that comorbid personality disorders (PDs) attenuate the clinical efficacy of PTSD treatment (Snoek et al., Citation2021), while other studies indicate that comorbid PTSD lowers the chance of remission from BPD (Zanarini et al., Citation2004, Citation2006). Together with the time-intensive, current standard of sequentially treating these disorders, this comorbidity can be quite challenging to tackle.

Next to these treatment-related challenges, the diagnostic classification of PTSD and BPD is surrounded by controversy. While BPD and PTSD diagnoses inherently differ due to the latter's reliance on criterion A trauma exposure, some question the validity of BPD as a distinct diagnostic entity. This primarily stem from the high comorbidity between PTSD and BPD, coupled with their overlapping etiological, neurobiological, and phenomenological features. Instead, it is argued that complex PTSD (cPTSD), which comprises the classic PTSD symptoms plus additional symptoms of affect dysregulation, negative self-concept and disturbances in relationships, would be a more accurate and less stigmatising diagnosis (Herman, Citation1992; Hodges, Citation2003; Kulkarni, Citation2017). While some studies support its inclusion as a distinct diagnostic entity (Cloitre et al., Citation2013, Citation2014; Hyland et al., Citation2019), others conclude that the available evidence is insufficient (Achterhof et al., Citation2019; Lewis & Grenyer Citation2009; Resick et al., Citation2012; Sar, Citation2011). Further complicating things, Powers et al. (Citation2022) found that the degree of distinction between PTSD, cPTSD and BPD depends on whether the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) is used. In sum, while these attempts at reclassification have brought much needed attention to the large heterogeneity of symptoms within trauma populations, it did not yet provide definitive insights.

Although the challenges described above fundamentally differ, they are all inherently linked to the way we conceptualise psychopathology. Psychopathology has traditionally been studied from the ‘latent variable’ perspective, including the DSM and ICD, where mental disorders are viewed as latent entities causing a set of passive symptoms (Borsboom & Cramer, Citation2013). Although the categorisation of complex groups of symptoms into latent mental disorders allows clinicians to develop a quick frame of reference and facilitates consensus across scientists, treatment providers and health insurers, it has received some considerable criticism in the past decade. Perhaps the most fundamental shortcoming of the latent variable model concerns its erroneous assumption that symptoms are no more than passive effects of a latent mental disorder, thereby largely ignoring the complex interactions between those symptoms. Moreover, by merging a group of highly heterogeneous individuals into discrete categories (e.g., presence or absence of a PTSD diagnosis), a great deal of clinically useful information is lost (Friborg et al., Citation2013; Suvak & Barrett, Citation2011). This disorder-level reasoning has led most research basing its conclusions on diagnostic status or symptom sum-scores as indicators of psychopathology and treatment effects, while largely ignoring the specific symptoms and interactions between those symptoms.

In recognition of the limitations of the latent variable model, a radically different approach for conceptualising psychopathology was introduced by Borsboom & Cramer, (Citation2013). The network approach to psychopathology discards the presence of latent mental disorders and instead conceptualises psychopathology as a network of causally interconnected, self-reinforcing symptoms (Borsboom & Cramer, Citation2013). Symptoms can become activated by multiple factors outside the network, such as adverse life events, biological-, psychological-, or societal factors (Borsboom, Citation2017). Once these external factors subside, symptoms may continue to active each other and the network becomes self-sustaining (Kalisch et al., Citation2019). In a visual representation of a psychopathology network, symptoms are illustrated as nodes and the connections between symptoms are illustrated as edges (Borsboom & Cramer, Citation2013). Although some symptoms tend to cluster more closely together than others, clear boundaries are absent which makes comorbidity an inherent aspect of symptom networks. By mapping the unique symptom structure of a group of patients, the network model holds potential for enhancing the efficacy of psychological interventions. For instance, successfully treating the most central symptoms in a network (those symptoms most strongly connected to other symptoms in the network) should lead to an overall deactivation of the symptom network and might thus be efficient when treating a single cluster of symptoms. Targeting bridge symptoms on the other hand (those symptoms that connect two clusters of symptoms), will likely disrupt the connection between two co-occurring clusters of symptoms and might thus be the best strategy of choice when treating comorbidity.

To the best of our knowledge, comorbidity between PTSD and BPD has not yet been explored from a network analytical perspective. Two network studies did, however, explore comorbidity between cPTSD and BPD using self-report questionnaires (Knefel et al., Citation2016; Owczarek et al., Citation2023). In both studies, cPTSD symptoms were only weakly connected to BPD symptoms. Owczarek et al. (Citation2023) concluded that cPTSD and BPD symptoms were connected through symptoms of affect dysregulation. Partly in line with this, Knefel et al. (Citation2016) concluded that the main connection between PTSD and cPTSD symptoms ran from the PTSD symptoms intrusive recollections, external avoidance and startle response to affect dysregulation symptoms including derealization, depersonalisation, emotional vulnerability and heightened emotional reactivity. Whereas Owczarek et al. (Citation2023) found identity disturbance, unstable relationships, anger and affective instability to be among the most central symptoms in the network, Knefel et al. (Citation2016) concluded that symptoms of re-experiencing, dissociation and affect dysregulation were most central.

In sum, only two network analytical studies investigated comorbidity between cPTSD and BPD using self-report data. The symptom structure underlying comorbid PTSD and BPD thus remains largely unknown. The present study aims to contribute to this knowledge gap by mapping the network structure of comorbid PTSD and BPD symptoms in 154 treatment-seeking patients with a PTSD diagnosis and BPD symptoms, assessed through clinician-administered structured interviews. Drawing from two studies investigating the symptom structure of cPTSD and BPD (Knefel et al., Citation2016; Owczarek et al., Citation2023), it is hypothesised that PTSD and BPD symptoms will largely cluster into two separate communities that are connected by affect dysregulation symptoms. Given the limited and inconsistent results of previous network studies on comorbid PTSD and BPD, the current study will investigate the most central symptoms in an exploratory manner.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The study sample comprised of 154 treatment-seeking patients who were enrolled in the Prediction and Outcome Study of PTSD and Personality Disorders (PROSPER) study at Sinai Centrum between May 2018 and March 2022. Sinai Centrum is a mental health care institution specialised in PTSD treatment. For the current study, we utilised baseline data that were collected as part of the PROSPER study (Snoek et al., Citation2020; Van den End et al., Citation2021). The PROSPER study was preregistered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03833453). All patients were 18 years and older and met DSM-5 criteria for PTSD, according to the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). In addition, all patients met at least four BPD criteria on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders self-report questionnaire (SCID-5-SPQ), after which the SCID-5-PD interview (SCID-5-PD) was conducted. The severity of BPD symptoms thus varied from subclinical (one to four symptoms) to clinical (five or more symptoms).

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5) is a 30-item structured clinician-administered interview assessing the 20 PTSD symptoms according to the DSM-5 (Weathers et al., Citation2013). Each symptom is rated on an intensity and frequency scale in reference to the previous month. Intensity and frequency scores are then combined into one overall severity score ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘extremely’). Total severity scores range from 0 to 80. Assessments were carried out by graduate level psychologists or research assistants, who had undergone accredited training from ARQ Academy. Cronbach's alpha was calculated using SPSS (version 29; IBM Corp, Citation2020) to assess the internal consistency within our sample. The coefficient for CAPS-5 items was 0.80, indicating strong reliability.

2.2.2. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD) is a semi-structured clinician-administered interview assessing the ten DSM-5 personality disorders. For the current study, the Dutch version of the SCID-5-PD was used to assess the nine symptoms of BPD (Arntz et al., Citation2017). Total scores range from 0 to 9, with a score of five or higher indicating a BPD diagnosis. Each assessment was carried out by a psychologist or research assistant, who received accredited training from ARQ Academy (Diemen, Netherlands). The calculation of Cronbach's alpha in SPSS yielded a coefficient of 0.69 for SCID-5-PD items within our sample, indicating acceptable reliability.

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Network estimation

The comorbid PTSD-BPD symptom network was estimated in R using the Bootnet package (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). A regularised partial spearman correlation network was estimated using the graphical LASSO (GLASSO) algorithm. The GLASSO algorithm selects the optimal degree of shrinkage according to a hyperparameter γ, which is selected with the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC). This hyperparameter was set to 0.1.

2.3.2. Accuracy and stability

Accuracy and stability were estimated using the Bootnet package in R (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). First, edge weight accuracy was assessed by estimating the 95% confidence intervals (Cis) through non-parametric bootstrapping (1000 samples). Smaller confidence intervals indicate greater accuracy. Second, the stability of strength centrality was assessed using case-dropping subset bootstrapping. As suggested by Epskamp et al. (Citation2018), the correlation stability coefficient (CS) should be at least .25 to interpret centrality differences.

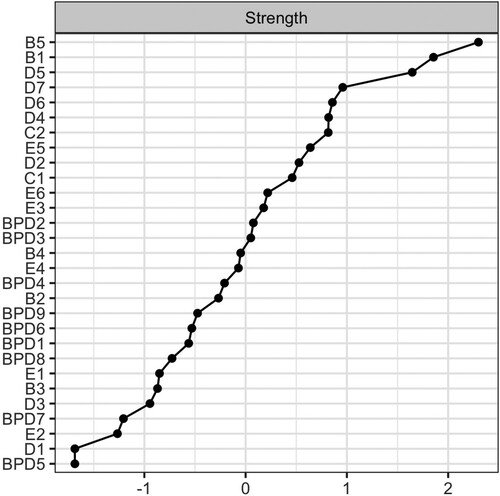

2.3.3. Central symptoms

Previous studies demonstrate that betweenness centrality and closeness centrality are unsuitable for psychological networks, while strength centrality has good stability and replicability (Bringmann et al., Citation2019; Epskamp et al., Citation2017). Solely strength centrality was therefore computed (the sum of the weights of all edges connected to a node) using the centralityPlot function of the qgraph package in R (Epskamp et al., Citation2017).

2.3.4. Bridge symptoms

Bridge symptoms between PTSD and BPD in each network were identified using the bridge function of the qgraph package in R (Epskamp et al., Citation2017). Bridge strength is defined as the sum of the absolute value of all edges between one node in a certain cluster and all nodes in another cluster. In other words, by calculating bridge strength we identified which PTSD symptom was most strongly connected to all BPD symptoms and vice versa.

2.3.5. Community detection

To identify communities within the PTSD-BPD network, the fast-greedy clustering algorithm was performed in R (Clauset et al., Citation2004).

3. Results

3.1. Sample description

Patient characteristics are presented in . The sample comprised of 154 participants. Ages ranged from 22 to 64 years, with a mean age of 40.7 (SD = 11.1) and 82 percent identified as female. The sample exhibited diverse ethnic backgrounds, predominantly consisting of Dutch individuals (57%). Prolonged periods of physical (38%) or sexual abuse (22%), typically spanning from months to years, were reported as the index trauma by most patients and frequently involved a relative as the perpetrator. This was followed by a singular incident of rape (23%), witnessing death (4%) and witnessing a murder (3%). Mean symptom scores and total scores are presented in . CAPS-5 total scores ranged from 17 to 64, with a mean total score of 41.58 (SD = 10.81). The total number of BPD criteria on the SCID-5-PD ranged from one to nine, with a mean number of criteria of 4.23 (SD = 2.37).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

Table 2. CAPS-5 and SCID-5-PD mean scores in 154 patients with PTSD and comorbid BPD symptoms.

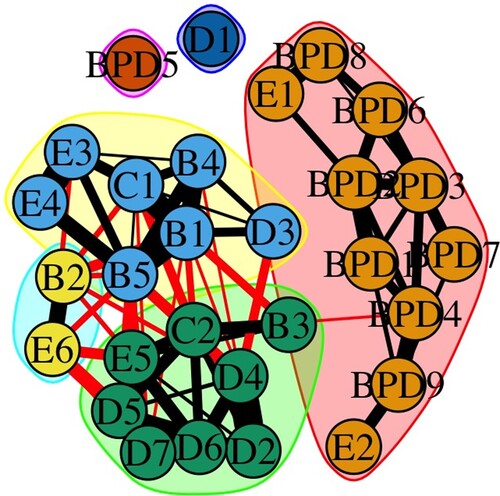

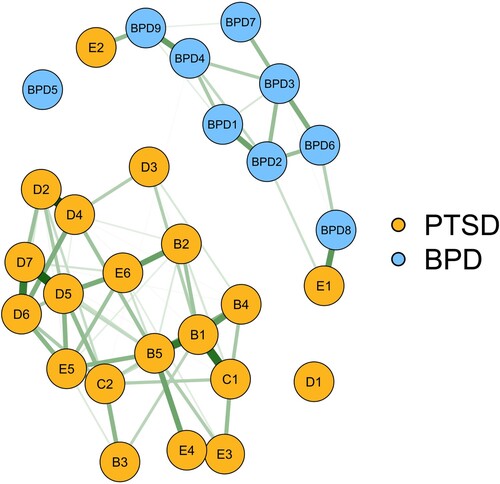

3.2. Network visualisation

A sparse network of 29 nodes and 74 edges was obtained (). The weights matrix is shown in . Symptoms of PTSD and BPD largely clustered into two separate communities. Visual inspection indicates that the PTSD symptom cluster was more densely connected than the BPD symptom cluster. The strongest edges were found between intrusive memories and psychological cue reactivity (B1-B4); intrusive memories and physiological cue reactivity (B1-B5); intrusive memories and avoidance of internal reminders (B1-C1); nightmares and sleep disturbance (B2-E6); physiological cue reactivity and exaggerated startle response (B5-E4); distorted negative beliefs and persistent negative emotional state (D2-D4); loss of interest and inability to experience positive emotions (D5-D7); social detachment and inability to experience positive emotions (D6-D7); hypervigilance and exaggerated startle response (E3-E4); irritable or angry behaviour and anger (E1-BPD8); fear of abandonment and unstable relationships (BPD1-BPD2) and between impulsivity and dissociation (BPD4-BPD9).

Figure 1. GLASSO symptom network in 154 patients with a PTSD diagnosis and comorbid BPD symptoms. PTSD symptoms are illustrated in orange and BPD symptoms are illustrated in blue. Green edges represent positive regularised partial correlations, whereas red edges indicate negative regularised partial correlations. Thicker edges denote stronger correlations between a pair of symptoms.

Table 3. Weights matrix.

3.3. Accuracy and stability

The CS of 0.25 or higher was maintained for all centrality metrics (SM1). Results further indicate that the majority of the 95% CIs for the edge weights were different from zero.

3.4. Central symptoms

Node strength is depicted in . The most central symptoms were intrusive memories (B1), physiological cue reactivity (B5) and loss of interest (D5), whereas amnesia (D1), reckless behaviour (E2) and suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviour (BPD5) were among the least central symptoms.

3.5. Bridge symptoms

Bridge symptoms that were in the 80th percentile or higher included irritable or angry behaviour (E1), reckless behaviour (E2), unstable relationships (BPD2), anger (BPD8) and dissociation (BPD9).

3.6. Sensitivity analyses

Due to the strong conceptual overlap between angry behaviour (E1) and anger (BPD8), two sensitivity analyses were conducted: first, excluding E1, and then excluding BPD8. The overall symptom network and centrality estimates remained similar across both analyses (SM 3-8). Both analyses revealed identical results with four bridge symptoms in the 80th percentile or higher: avoidance of external reminders (C2), reckless behaviour (E2), impulsivity (BPD4), and dissociation (BPD9).

3.7. Community detection

Six communities were detected (). The largest community comprised all BPD symptoms plus angry (E1) and reckless (E2) behaviour. The second-largest community comprised flashbacks (B3), avoidance of external reminders (C2), six negative mood and cognitions symptoms (D2-D7) and difficulty concentrating (E5). The third community included three intrusive symptoms (B1, B4, B5), avoidance of internal reminders (C1), hypervigilance (E3) and exaggerated startle response (E4). The fourth community contained nightmares (B2) and sleep disturbance (E6). The fifth and sixth community comprised solely trauma-related amnesia (D1) and suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviour (BPD5).

4. Discussion

This constitutes the first study conceptualising the network structure of comorbid PTSD and BPD symptoms, solely using clinician-administered interview data. Current findings offer novel insights on the symptom structure underlying PTSD-BPD comorbidity, as well as central and bridge symptoms that may serve as valuable treatment targets.

There was little covariation between the PTSD and BPD symptoms in the present sample. The PTSD symptom cluster was more densely connected than the BPD symptom cluster. This finding is in line with our hypothesis and mirrors the findings of two previous network analytical studies of comorbid cPTSD and BPD (Knefel et al., Citation2016; Owczarek et al., Citation2023), who also concluded that the BPD network was only weakly connected to the cPTSD network. This altogether suggests that PTSD and BPD are two distinct, albeit weakly connected, disorders. Besides validating the correct DSM-5 classification of these symptoms, current findings can directly guide symptom-oriented treatments. As such, findings suggest that it is unlikely that treating PTSD symptoms will automatically deactivate BPD symptoms or vice versa. Instead, treatments targeting both symptom networks are more likely to be effective. These findings are in line with the development of integrated treatment protocols for comorbid PTSD and BPD symptoms (Bohus et al., Citation2013; Dorrepaal et al., Citation2012; Harned et al., Citation2014). Limited evidence suggests that such integrated interventions are more effective in reducing comorbid PTSD and BPD symptoms compared to stand-alone interventions (Bohus et al., Citation2013; Dorrepaal et al., Citation2012; Harned et al., Citation2014).

Three symptom pathways were identified. The first two pathways ran between PTSD symptom irritable or angry behaviour and BPD symptoms anger and unstable relationships. The remaining pathway ran between PTSD symptom reckless behaviour and BPD symptom dissociation. These findings are partly consistent with previous network analytical findings, who also found symptoms of affect dysregulation to be important in connecting cPTSD and BPD symptoms (Owczarek et al., Citation2023). Although bridge symptoms between PTSD and BPD were not explicitly mentioned by Knefel et al. (Citation2016), visual inspection of the symptom network suggests that reckless behaviour, unstable relationships, feelings of emptiness and dissociation played an important role in connecting PTSD and BPD symptoms. Although it is generally assumed that bridge symptoms can disrupt the connection between two disorders and might thus be a good strategy of choice when treating comorbidity, this might be somewhat different within the current study. The strong connection observed between PTSD symptom irritable or angry behaviour and BPD symptom anger could simply be due to their large conceptual overlap. All analyses were therefore repeated without these symptoms, resulting in similar findings for the overall symptom network, centrality indices, and community detection. However, the findings regarding bridge symptoms differed. When excluding either irritable or angry behaviour or anger from the analyses, avoidance of external reminders, reckless behaviour, impulsivity, and dissociation were identified as bridge symptoms. The bridge between reckless behaviour and dissociation thus appeared relatively robust. However, reckless behaviour showed minimal connections with its own PTSD symptom cluster, suggesting that treating this symptom may deactivate the BPD network but have little impact on the PTSD network. Consequently, the clinical utility of the identified bridge symptoms in the current study is questionable. Future research with larger sample sizes and longitudinal designs should explore this further.

Six symptom clusters were identified. The largest community comprised all BPD symptoms plus angry (E1) and reckless (E2) behaviour. The second-largest community included flashbacks (B3), avoidance of external reminders (C2), six negative mood and cognitions symptoms (D2-D7) and difficulty concentrating (E5). Three intrusive symptoms (B1, B4, B5), avoidance of internal reminders (C1), hypervigilance (E3) and exaggerated startle response (E4) made up the third community. Nightmares (B2) and sleep disturbance (E6) formed the fourth community. The fifth and sixth communities comprised solely trauma-related amnesia (D1) and suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviour (BPD5). These findings largely mirror previous network analytical findings of PTSD (Birkeland et al., Citation2020) and PTSD-BPD comorbidity (Knefel et al., Citation2016; Owczarek et al., Citation2023) and to a lesser extent factor-analytical studies on the structure of PTSD symptoms (Elklit & Shevlin, Citation2007; Price & van Stolk-Cooke, Citation2015). It is important to consider that these community structures may partly result from the study design, as items within a questionnaire are likely to be more strongly connected to each other compared to items from another questionnaire. However, the distinct communities within the PTSD symptom network may still offer valuable insights for refining treatment approaches. Prioritising treatment based on the symptom cluster with the highest total score, followed by the next highest score, and so on, could be a viable approach. This possibility should be further validated through experimental longitudinal research. The most central symptoms in the PTSD-BPD network were Intrusive memories, physiological cue reactivity and loss of interest, whereas amnesia, reckless behaviour and suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviour were least central. These findings largely echo previous studies, who also found intrusive memories and physiological cue reactivity to be among the most central symptoms in PTSD networks (Birkeland et al., Citation2020; Contreras et al., Citation2019), and symptoms of re-experiencing and affect dysregulation to be among the most central symptoms in a PTSD-BPD network (Knefel et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, McNally et al. (Citation2017) found that physiological cue reactivity may be an important causal factor in the activation of the PTSD symptom network, since it directly predicted psychological cue reactivity, flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of trauma-related external reminders, startle response and loss of interest. The low centrality of trauma-related amnesia and suicidal and/or self-mutilating behaviour has been consistently replicated in previous network analytical studies (Birkeland et al., Citation2020; Owczarek et al., Citation2023) and factor-analytical studies (Armour et al., Citation2016) as well.

The present study has several limitations that should be addressed. First, the direction of edges could not be determined since cross-sectional data were used. It is therefore unclear whether central symptoms received or provided a lot of input to other symptoms. Although several studies have shown that central symptoms are predictive of treatment outcome (Elliott et al., Citation2020; Papini et al., Citation2020), more so than non-central symptoms (Olatunji et al., Citation2018), this does not imply that central symptoms are the most valuable targets. Experimental, longitudinal studies could further investigate this hypothesis, for example by determining if and to what extent an intervention targeting the most central symptoms leads to an extinction of the overall symptom network. Second, the study sample was relatively small. This was mainly due to the fact that clinical interview methods were used to assess the PTSD and BPD symptoms, which is quite time-consuming and labour-intensive. This did, however, result in high quality data within a specific patient sample that has been little studied so far. Although stability and accuracy analyses indicated that the results were sufficiently reliable, it is important to interpret findings and their generalizability with caution due to the small sample size. Third, our sample was primarily female and European American, which may limit the generalizability to other populations. Last, since the number of BPD symptoms in the present sample varied from one to nine, the network structure might be different in patients with more severe BPD.

In conclusion, current findings increase our understanding of the symptom structure underlying PTSD-BPD comorbidity, as well as symptoms that may serve as valuable treatment targets. This constitutes an important step towards optimising case-conceptualization and improving the subsequent treatment of these symptoms. Approaching comorbid PTSD and BPD from a network analytical perspective thereby supports clinicians to effectively tackle the complex, dynamic symptomatology their patients present themselves with.

Ethical standards

The PROSPER study is performed according to the declaration of Helsinki (64th WMA general assembly; October 2013) and the International Conference on Harmonisation – Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). The study protocol has been approved by the medical ethics committee (METC VUmc – case number A2018.428 (2017.335)).

SM2.tiff

Download TIFF Image (27.5 KB)SM7.tiff

Download TIFF Image (161.4 KB)SM6.tiff

Download TIFF Image (154.5 KB)SM3.tiff

Download TIFF Image (588.9 KB)R code network analysis.pdf

Download PDF (35 KB)SM1.tiff

Download TIFF Image (88.4 KB)SM5.tiff

Download TIFF Image (158.2 KB)SM8.tiff

Download TIFF Image (157.7 KB)SM4.tiff

Download TIFF Image (163.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw, deidentified data are available upon reasonable request via a data use agreement.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achterhof, R., Huntjens, R. J., Meewisse, M. L., & Kiers, H. A. (2019). Assessing the application of latent class and latent profile analysis for evaluating the construct validity of complex posttraumatic stress disorder: Cautions and limitations. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1698223. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1698223

- Armour, C., Műllerová, J., & Elhai, J. D. (2016). A systematic literature review of PTSD's latent structure in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV to DSM-5. Clinical Psychology Review, 44, 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.003

- Arntz, A., Kamphuis, J. H., & Derks, J. (2017). Gestructureerd klinisch interview voor DSM-5 Persoonlijkheidsstoornissen. Amsterdam: Boom uitgevers.

- Barnicot, K., Katsakou, C., Marougka, S., & Priebe, S. (2011). Treatment completion in psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 123(5), 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01652.x

- Birkeland, M. S., Greene, T., & Spiller, T. R. (2020). The network approach to posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1700614. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1700614

- Bohus, M., Dyer, A. S., Priebe, K., Krüger, A., Kleindienst, N., Schmahl, C., Niedtfeld, I., & Steil, R. (2013). Dialectical behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual abuse in patients with and without borderline personality disorder: A randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(4), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348451

- Borsboom, D. (2017). A network theory of mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20375

- Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

- Bradley, R., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L., & Westen, D. (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214

- Bringmann, L. F., Elmer, T., Epskamp, S., Krause, R. W., Schoch, D., Wichers, M., Wigman, J. T. W., & Snippe, E. (2019). What do centrality measures measure in psychological networks? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 128(8), 892. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000446

- Clauset, A., Newman, M. E., & Moore, C. (2004). Finding community structure in very large networks. Physical Review E, 70(6), 066111. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.70.066111

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., & Maercker, A. (2013). Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 20706. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.20706

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Weiss, B., Carlson, E. B., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25097. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v5.25097

- Contreras, A., Nieto, I., Valiente, C., Espinosa, R., & Vazquez, C. (2019). The study of psychopathology from the network analysis perspective: A systematic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 88(2), 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1159/000497425

- Cristea, I. A., Gentili, C., Cotet, C. D., Palomba, D., Barbui, C., & Cuijpers, P. (2017). Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder. Jama Psychiatry, 74(4), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.4287

- Dorrepaal, E., Thomaes, K., Smit, J. H., Van Balkom, A. J., Veltman, D. J., Hoogendoorn, A. W., & Draijer, N. (2012). Stabilizing group treatment for complex posttraumatic stress disorder related to child abuse based on psychoeducation and cognitive behavioural therapy: A multisite randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 81(4), 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1159/000335044

- Elklit, A., & Shevlin, M. (2007). The structure of PTSD symptoms: A test of alternative models using confirmatory factor analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(3), 299–313. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466506X171540

- Elliott, H., Jones, P. J., & Schmidt, U. (2020). Central symptoms predict posttreatment outcomes and clinical impairment in anorexia nervosa: A network analysis. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619865958

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1

- Epskamp, S., Costantini, G., Haslbeck, J., Cramer, A. O., Epskamp, M. S., & RSVGTipsDevice, S. (2017). Package ‘qgraph’.

- Frías, Á., & Palma, C. (2015). Comorbidity between post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder: A review. Psychopathology, 48(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1159/000363145

- Friborg, O., Martinussen, M., Kaiser, S., Øvergård, K. T., & Rosenvinge, J. H. (2013). Comorbidity of personality disorders in anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of 30 years of research. Journal of Affective Disorders, 145(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2012.07.004

- Harned, M. S., Korslund, K. E., & Linehan, M. M. (2014). A pilot randomized controlled trial of dialectical behavior therapy with and without the dialectical behavior therapy prolonged Exposure protocol for suicidal and self-injuring women with borderline personality disorder and PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 55, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.01.008

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490050305

- Hodges, S. (2003). Borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Time for integration? Journal of Counseling & Development, 81(4), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2003.tb00267.x

- Hyland, P., Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., & Cloitre, M. (2019). Examining the discriminant validity of complex posttraumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder symptoms: Results from a United Kingdom population sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(6), 855–863. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22444

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 27.0). [Computer software]. IBM Corp.

- Imel, Z. E., Laska, K., Jakupcak, M., & Simpson, T. L. (2013). Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 394. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031474

- Kalisch, R., Cramer, A. O. J., Binder, H., Fritz, J., Leertouwer, I., Lunansky, G., Meyer, B., Timmer, J., Veer, I. M., & Van Harmelen, A.-L. (2019). Deconstructing and reconstructing resilience: A dynamic network approach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(5), 765–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619855637

- Knefel, M., Tran, U. S., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2016). The association of posttraumatic stress disorder, complex posttraumatic stress disorder, and borderline personality disorder from a network analytical perspective. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.002

- Kulkarni, J. (2017). Complex PTSD–a better description for borderline personality disorder? Australasian Psychiatry, 25(4), 333–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1039856217700284

- Lewis, K. L., & Grenyer, B. F. (2009). Borderline personality or complex posttraumatic stress disorder? An update on the controversy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 17(5), 322–328. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673220903271848

- McNally, R. J., Heeren, A., & Robinaugh, D. J. (2017). A Bayesian network analysis of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults reporting childhood sexual abuse. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup3), 1341276. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1341276

- Olatunji, B. O., Levinson, C., & Calebs, B. (2018). A network analysis of eating disorder symptoms and characteristics in an inpatient sample. Psychiatry Research, 262, 270–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.02.027

- Owczarek, M., Karatzias, T., McElroy, E., Hyland, P., Cloitre, M., Kratzer, L., Knefel, M., Grandison, G., Ho, G. W. K., Morris, D., & Shevlin, M. (2023). Borderline personality disorder (BPD) and complex posttraumatic stress disorder (CPTSD): A network analysis in a highly traumatized clinical sample. Journal of Personality Disorders, 37(1), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.2023.37.1.112

- Pagura, J., Stein, M. B., Bolton, J. M., Cox, B. J., Grant, B., & Sareen, J. (2010). Comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in the U.S. population. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 44(16), 1190–1198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.016

- Papini, S., Rubin, M., Telch, M. J., Smits, J. A., & Hien, D. A. (2020). Pretreatment posttraumatic stress disorder symptom network metrics predict the strength of the association between node change and network change during treatment. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(1), 64–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22379

- Powers, A., Petri, J. M., Sleep, C., Mekawi, Y., Lathan, E. C., Shebuski, K., Bradley, B., & Fani, N. (2022). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder using exploratory structural equation modeling in a trauma-exposed urban sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 88, 102558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102558

- Price, M., & van Stolk-Cooke, K. (2015). Examination of the interrelations between the factors of PTSD, major depression, and generalized anxiety disorder in a heterogeneous trauma-exposed sample using DSM 5 criteria. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.012

- Resick, P. A., Bovin, M. J., Calloway, A. L., Dick, A. M., King, M. W., Mitchell, K. S., Suvak, M. K., Wells, S. Y., Stirman, S. W., & Wolf, E. J. (2012). A critical evaluation of the complex PTSD literature: Implications for DSM-5. Journal of traumatic stress, 25(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21699

- Sar, V. (2011). Developmental trauma, complex PTSD, and the current proposal of DSM-5. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2(1), 5622. https://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5622

- Snoek, A., Beekman, A. T. F., Dekker, J., Aarts, I., van Grootheest, G., Blankers, M., Vriend, C., van den Heuvel, O., & Thomaes, K. (2020). A randomized controlled trial comparing the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and integrated EMDR-Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (DBT) in the treatment of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid (Sub) clinical borderline personality disorder: study design. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02713-x

- Snoek, A., Nederstigt, J., Ciharova, M., Sijbrandij, M., Lok, A., Cuijpers, P., & Thomaes, K. (2021). Impact of comorbid personality disorders on psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1929753. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1929753

- Suvak, M. K., & Barrett, L. F. (2011). Considering PTSD from the perspective of brain processes: A psychological construction approach. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20618

- Van den End, A., Dekker, J., Beekman, A. T. F., Aarts, I., Snoek, A., Blankers, M., Vriend, C., van den Heuvel, O. A., & Thomaes, K. (2021). Clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of imagery rescripting only compared to imagery rescripting and schema therapy in adult patients With PTSD and comorbid cluster C personality disorder: Study design of a randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 633614. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.633614

- Watts, B. V., Schnurr, P. P., Mayo, L., Young-Xu, Y., Weeks, W. B., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(6), e541–e550. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.12r08225

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). Interview available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov, 6.

- Woodbridge, J., Townsend, M., Reis, S., Singh, S., & Grenyer, B. F. (2022). Non-response to psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: A systematic review. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 56(7), 771–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211046893.

- Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Hennen, J., Reich, D. B., & Silk, K. R. (2004). Axis I comorbidity in patients with borderline personality disorder: 6-year follow-up and prediction of time to remission. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(11), 2108–2114. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2108

- Zanarini, M. C., Frankenburg, F. R., Hennen, J., Reich, D. B., & Silk, K. R. (2006). Prediction of the 10-year course of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(5), 827–832. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.2006.163.5.827