ABSTRACT

Background: Although childhood maltreatment is associated with later self-harm, the mechanism through which it might lead to self-harm is not completely understood. The purpose of this study was to examine the roles of alexithymia, dissociation, internalizing and posttraumatic symptoms in the association between exposure to childhood maltreatment and subsequent self-harm.

Methods: A total of 360 adolescents were asked to complete the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, the Toronto Alexithymia Scale, the Dissociative Experience Scale, the Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire-20, the Posttraumatic Stress Checklist for DSM-5, and the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory.

Results: Results of structural equation modelling analysis revealed the significant mediation effects of alexithymia and dissociative symptoms in the relationship between childhood maltreatment and self-harm, while internalizing and posttraumatic symptoms did not significantly mediate.

Conclusion: The findings indicate that alexithymia and dissociative symptoms may be proximal mechanisms linking maltreatment exposure and adolescence self-harm.

HIGHLIGHTS

Self-harm can be used as a maladaptive coping strategy in response to both hyper- and hypo-arousal symptoms.

Alexithymia and dissociative symptoms may be proximal mechanisms linking maltreatment exposure and adolescent self-harm.

Posttraumatic symptoms did not mediate the relationship between a history of childhood maltreatment and self-harm.

Antecedentes: Aunque el maltrato infantil se asocia con la autolesión posterior, no se comprende completamente el mecanismo a través del cual se podría conducir a la autolesión. El propósito de este estudio fue el de examinar los papeles de la alexitimia, disociación, síntomas internalizantes y postraumáticos en la asociación entre la exposición a maltrato infantil y la autolesión subsecuente.

Métodos: Se le solicitó a un total de 360 adolescentes que completaran el Cuestionario de Trauma Infantil, la Escala de Alexitimia de Toronto, la Escala de Experiencias Disociativas, el Cuestionario de Disociación Somatomorfo-20, la Lista de Chequeo de Estrés Postraumático para el DSM-5 y el Inventario de Autolesión Deliberada.

Resultados: Los resultados del análisis del modelo de ecuaciones estructurales revelaron los efectos de mediación significativos de la alexitimia y síntomas disociativos en la relación entre maltrato infantil y autolesión, mientras que los síntomas internalizantes y postraumáticos no mediaron significativamente.

Conclusión: Los hallazgos indican que la alexitimia y síntomas disociativos pueden ser mecanismos proximales que vinculan la exposición al maltrato y la autolesión en la adolescencia.

PALABRAS CLAVE:

1. Introduction

Self-harm is defined as the direct intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue, with or without the intention to die and for purposes not culturally sanctioned (Gratz, Citation2001; Gratz et al., Citation2014). The two most common types of self-injury behaviours are self-cutting and self-hitting, but other cases consist of burning, whipping, pinching, scratching, and self-poisoning (Norman & Borrill, Citation2015). Although there is no agreement about the prevalence rate due to various definitions and self-report measure used, self-harm is particularly frequent during the adolescence period with prevalence rates ranging between 17.1% and 38.7% (Plener et al., Citation2015). In regard to the gender differences, it has been reported that adolescent girls engage more frequently in self-harm than boys (Nawaz et al., Citation2024).

According to the literature, a number of theoretical frameworks have appeared to explain how self-harm may provide specific functions and motivations which maintain and reinforce such behaviours (Klonsky et al., Citation2011; Nock, Citation2009). Previous studies on self-harm in adolescents indicate that teenagers engage in self-harm for intrapersonal as well as interpersonal reasons (Klonsky et al., Citation2011; Nock, Citation2009). On an intrapersonal level, the main function of self-harm is to regulate negative emotions or psychological states. In fact, the individual functions of these behaviours highlight the role of self-punishment in vulnerability to and maintenance of self-harm through creating good feelings or generating energy as well as escaping from negative affect (Lloyd-Richardson et al., Citation2007; Nock & Prinstein, Citation2004). On the other hand, from the interpersonal point of view, self-harm can be considered as a mechanism to receive attention or access to resources and to avoid punishment by others (Klonsky et al., Citation2011; Nock, Citation2009; Nock & Prinstein, Citation2004).

A substantial number of studies conducted on self-harm have yielded useful information about important risk factors for self-harm (Hawton et al., Citation2012; Nock, Citation2014). Risk factors for self-harm include low socio-economic status, female gender, sexual orientation (LGBT), a history of childhood maltreatment, family history of suicide, bullying, impulsivity, low self-esteem, and mental disorder (Knipe et al., Citation2022; Nock, Citation2014; Stänicke et al., Citation2024). Self-harm is often accompanied by several mental illnesses, and is known to be a risk factor for suicidality (Klonsky et al., Citation2013; Ross et al., Citation2023; Tuisku et al., Citation2014). Particularly, it has been reported that self-harm is related to a wide range of mental disorders such as mood disorders (e.g. major depression and bipolar disorders), anxiety disorders, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), drug abuse, eating disorders, autism, psychosis, and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) (Hawton et al., Citation2012). According to Klonsky et al. (Citation2003), self-harm occurs and is associated with psychiatric problems even in non-clinical populations.

One area of study which focused on possible mechanism for self-harm is Childhood Maltreatment (CM). Research on the potential mechanisms linking Childhood Maltreatment (CM) to self-harm has reported CM as a major cause of self-harm (Zhang et al., Citation2024). However, evidence supporting this relationship remains inconclusive. Some studies have reported a significant relationship between CM and self-harm (Lang & Sharma-Patel, Citation2011), whereas others have not found any association (Klonsky & Moyer, Citation2008). There is a lack of research on specific mechanisms that might explain the relationship between CM and self-harm. Self-harm is often conceptualized as a maladaptive coping mechanism for managing symptoms that emerge after experiencing CM (Smith et al., Citation2014). Yet, the specific symptoms or syndromes that act as underlying mechanisms have not been clearly identified. Common psychopathological symptoms resulting from CM include PTSD, internalizing symptoms, dissociative disorders or symptoms, and alexithymia (the inability to identify and describe emotions) (Kefeli et al., Citation2018; Reis et al., Citation2024; Shenk et al., Citation2022). The high prevalence and comorbidity of these symptoms make it essential to determine their functional role in the development of self-harm. While previous studies have explored the role of these factors in the etiology of self-harm (Ford & Gómez, Citation2015; Kranzler et al., Citation2016; Shenk et al., Citation2010; Swannell et al., Citation2012), the literature is limited by the absence of a cohesive model that incorporates these variables.

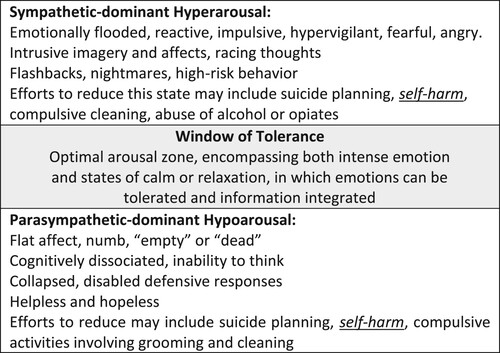

The ‘Window of Tolerance’ (WOT) model, proposed by Ogden et al. (Citation2006), is used to explain the unpredictable and sudden changes in clinical symptoms seen in disorders following severe trauma. Siegel (Citation1999) describes a range of optimal arousal between the extremes of the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) and the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PsNS), within which emotions are manageable and experiences can be integrated. Each person's capacity to process information is influenced by the habitual width of their WOT. Those with a wide WOT can handle higher levels of arousal and process complex information more effectively, while individuals with a narrow WOT find fluctuations unmanageable and dysregulating. Traumatized individuals, especially those with repeated or prolonged childhood trauma (such as sexual or physical abuse, domestic violence, or trauma from medical treatments and accidents), tend to have a narrow WOT. This results in being more susceptible to negative emotional states, such as impulsivity, aggression, fear, anxiety, panic, hypervigilance, flashbacks, and nightmares (indicating sympathetic hyperarousal dominance), or exhaustion, numbness, depression, shame, catatonia, poor digestion, and dissociation (arising from PsNS activation) (Corrigan et al., Citation2011).

Following the above content, it should be mentioned that the coping strategies that people employ to deal with the aforementioned emotional states are different. For instance, high arousal states can be modulated by suicide planning, starvation, abuse of alcohol and cannabis, bathing, grooming and compulsive cleaning, and self-harm. On the other hand, the efforts to reduce low arousal state include risk-taking behaviour (like driving too fast), compulsive activities involving grooming and cleaning, suicide, self-harm, and abuse of alcohol, amphetamine, ecstasy, and cocaine (Corrigan et al., Citation2011) (See ).

Figure 1. Window of tolerance. Adopted from Corrigan et al. (Citation2011).

Although the current theoretical model (i.e. window of tolerance) highlights the role of coping strategies, in particular self-harm, in modulating various symptoms which arise in the aftermath of facing with early traumatic experiences, this association has not been investigated in the frame of the aforementioned theoretical model. In fact, to our knowledge, no study to date has simultaneously examined the effects of psychological symptoms or syndromes that indicate the hyper-activity of both SNS (anxiety and PTSD) and PsNS (depression, alexithymia and paycho/somatoform dissociation) in the relationship between CM and self-harm. Furthermore, although the relationship between CM and self-harm seems logical, this association in different studies has had contradictory results (Kranzler et al., Citation2016; Lüdtke et al., Citation2016; Shenk et al., Citation2010; Swannell et al., Citation2012), which indicates the various effects of different mediating variables. Thus, based on the above theoretical and empirical evidence, the aim of the present study is to develop an integrative model to test alexithymia, internalizing (depression and anxiety), dissociative (psycho/somatoform dissociation) and posttraumatic symptoms as potential mediators of the association between CM and self-harm frequency in a community sample of adolescents.

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedure

Data was collected from several high schools and universities, located in different areas of Tehran (Iran). In total, 365 adolescent students were selected to participate in this study using a convenience sampling method. Five students were excluded due to missing responses. The final sample included 360 students (204 boys, 156 girls), aging from 15 to 20 years (boys: 18.12 ± 2.28; girls: 17.52 ± 2.69). Of these, 183 participants 50.8% reported at least one prior episode of self-harm. The study procedure was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Reg. IR.USWR.REC.1397.129). In the first step, all students signed an informed consent form prior to conducting the study. Then, socio-demographic information was collected in an interview format by research assistants. All other information was gathered through pen and paper instruments, with research assistants being available for any question or explanation.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)

To assess the severity and frequency of childhood trauma, the 28-item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) (Bernstein et al., Citation2003) was used. This measure is designed to evaluate the history of childhood maltreatment in five dimensions: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect. Each dimension consists of five questions which are individually coded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never true to 5 = very often true). Higher scores of CTQ reveal more severe maltreatment experienced. The CTQ has been widely used to assess maltreatment severity and demonstrated to be a valid and reliable questionnaire for evaluating childhood maltreatment experiences (Bernstein et al., Citation2003; Spinhoven et al., Citation2014). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the total scale of the CTQ was 0.71.

2.2.2. Posttraumatic Stress Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)

Symptoms of PTSD were assessed through the Posttraumatic Stress Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (Blevins et al., Citation2015). The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measure that covers PTSD symptoms in four clusters of intrusion (items 1–5), avoidance (items 6–7), negative cognitions and mood (items 8–14), and hyper-arousal (items 15–20). The range of response options is from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely) and the total score is gained from the sum of the items’ scores, where higher scores show greater severity of PTSD symptoms. In different populations including veterans and university students, the PCL-5 has shown good psychometric properties (Blevins et al., Citation2015; Bovin et al., Citation2016). Internal consistency of the total scores of the PCL-5 in this study was excellent (α = 0.91).

2.2.3. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21)

The DASS-21 is a well-established measure for evaluating three negative emotional states of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms during the past week (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). This questionnaire consists of three subscales: depression (7 items), anxiety (7 items), and stress (7 items), and each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (did not applied to me at all) to 5 (applied to me all the times). Higher scores indicate greater experience of depression, anxiety, and stress. The DASS-21 has been widely used among university student populations and shown good reliability and validity (Cavanagh et al., Citation2016; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). In the present study, the depression and anxiety subscales were used, and Cronbachʹs alpha for these subscales was 0.87 and 0.71, respectively.

2.2.4. Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS-20)

Alexithymia was assessed via the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20 (TAS-20) (Bagby et al., Citation1994). This measure includes 20 items in three dimensions including the Difficulty Describing Feelings (DDF) subscale (e.g. ‘It is difficult for me to find the right words for my feelings’), the Difficulty Identifying Feelings (DIF) subscale (e.g. ‘I am often confused what emotion I am feeling’), and the Externally Oriented Thinking (EOT) subscale (e.g. ‘I prefer to analyze problems rather than to only describe them’). Participants responded to sentences using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Higher total subscale scores indicate higher levels of the three aspects of alexithymia. In the original study, Bagby et al. (Citation1994) reported high internal consistency for each of the three subscales (α = 0.75, 0.78, and 0.66 for the DDF, DIF, and EOT respectively). In the current study, Cronbachʹs alpha for total scale was 0.77.

2.2.5. Dissociative Experiences Scale (DES)

Psychological dissociation was examined using the Dissociative Experience Scale-II (DES-II) (Carlson & Putnam, Citation1993). The DES-II is a 28-item self-report questionnaire of dissociative experiences, which requires participants to indicate on a scale ranging from 0 to 100 at 10% intervals (corresponding to an 11-point Likert item) to what extent presented statements of dissociative experiences apply to them. The total score of the DES-II can range from 0% to 100%, and the average score is calculated by adding up the 28-item scores and dividing them by 28. The DES is generally used as a screening tool and not a diagnostic tool, and consists of three areas of amnesia, absorption, and depersonalization-derealization. The Persian version of this scale showed good psychometric properties (Abasian et al., Citation2016).

2.2.6. Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire-20 (SDQ-20)

Somatoform dissociative symptoms were measured through the Somatoform Dissociative Symptoms-20 (SDQ-20) (Nijenhuis et al., Citation1998). It is a 20-item self-report questionnaire which refers to both positive (pain in a specific part of the body, and the alteration of taste and smell preferences/aversions) and negative (analgesia, anesthesia, and motor inhibitions) dissociative symptoms, each of them associated with the frequency of the physical symptoms mentioned in the statement. A 5-point Likert scale is used to show what degree the statements apply. The overall score ranges from 20 to 100, which higher scores indicating severe dissociative symptoms. In the original study (Nijenhuis et al., Citation1998), the reliability of the SDQ-20 was high, and the construct validity was good. In the present study, Cronbachʹs alpha was 0.70.

2.2.7. Deliberate Self-harm Inventory (DSHI)

The Deliberate Self-harm Inventory (DSHI) is a 17-item self-report questionnaire which measures the history of self-harm behaviour and consists of frequency, duration, and type of self-mutilation (like cutting, burning, scarring, breaking bones, etc.) (Gratz, Citation2001). In this inventory, participants are asked to answer a series of questions about types of self-harm based on a binary format (e.g. yes or no). In addition, the DSHI provides a measurement of the frequency of self-harming behaviour rather than simply asking the presence or absence of this behaviour. In the present study, a continuous variable assessing frequency of reported self-harm was created through subjectsʹ scores on the frequency questions for each item. The DSHI has reported good psychometric properties in a sample of non-clinical undergraduates (Gratz, Citation2001).

2.3. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using the IBM SPSS for Windows, version 21. Outliers were checked using box plots and excluded from the relevant analysis. To examine the socio-demographic data, descriptive statistics were calculated by the measures of central tendency. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) was used, through the two steps recommended by Leguina (Citation2015). First, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis for evaluating the measurement model. Second, the evaluation of the structural model. For analysing our model, Smart-PLS 3.3.3, a PLS structural equation modelling tool was used. Here, it is necessary to express the two reasons for its use in the present study; as expressed by Chin (Citation2009). First, the PLS-SEM has a soft distributive assumption and as the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests were significant, it is indicated that the scores were not normally distributed. Second, the complexity of the present model justifies the use of PLS-SEM because the tested model contains multiple moderating variables (Hair et al., Citation2011; Henseler et al., Citation2009; Henseler & Sarstedt, Citation2013).

3. Results

3.1. The external model

The results show that the measures are robust in terms of their internal consistency and reliability as indexed through Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability. All of the values of Cronbach's alpha and the composite reliabilities of the different measures indicated good reliability (>0.70) (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). The Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for all constructs was 0.50 or higher, except childhood maltreatment, which indicated convergent validity for most of the measures (See ).

Table 1. The results of the measurement model of childhood maltreatment and its mediating variables.

For evaluating discriminant validity, the Fornell Larcker criterion was used. As suggested by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the square root of AVE in each latent variable can be used to establish discriminant validity. This value should be higher than other correlation values among the latent variables. As shown in , all square root values of AVE of each latent variable are larger than correlation values among all other latent variables.

Table 2. Correlation matrix between latent variables.

3.2. The structural model

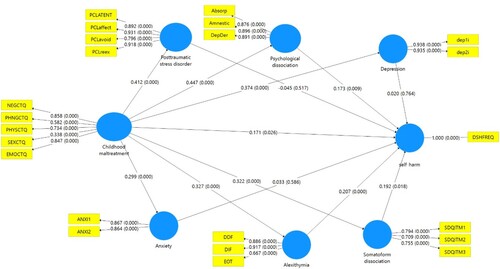

After evaluating the external validity, the structural model was examined, which represents the relationships between the constructs assumed in the theoretical model or latent variables. In order to examine the structural model, as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2021), first, the collinearity problem based on the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) of all the sets of predictive constructions in the structural model was examined. All the values fluctuated between 1.413 and 2.090, so the VIF for all the values are lower than the threshold of 5. Therefore, the collinearity between the predictor constructs is not a vital problem in the structural model. In addition, shows the R2 values of PTSD (.170), anxiety (.089), alexithymia (.107), psychological dissociation (.199), somatoform dissociation (.104), depression .(140), and self-harm (.326). Falk and Miller (Citation1992) suggest a value of .10 for an R squared at least satisfactory level. With the exclusion of anxiety, all other endogenous latent variables possess the threshold level of R-squared values. In addition, all Q2 for all the endogenous latent variables including PTSD (.121), anxiety (.063), alexithymia (.068), psychological dissociation (.145), somatoform dissociation (.054), depression (.116), and self-harm (.284) are above zero providing support for the predictive relevance of the model with respect to endogenous latent variables.

Table 3. Structural model results.

shows the results of the structural model and the beta values of all the path coefficients. According to , all the direct paths, with the exception of PTSD to Self-harm (β = –.045, p = .531), anxiety to DSH (β = .33, p = .624), and depression to self-harm (β = .020, p = .772) are significant. In addition, also shows that the effect sizes (f2) of exogenous variables on endogenous variables are in the range of .001 to .205, with the exception of three paths mentioned above, all paths exceed the minimum threshold of .02 suggested by Chin et al. (Citation2003).

Table 4. Direct relationship between variables.

3.3. Mediation effects

The mediation effects were estimated based on 5,000 bootstrap samples. As shown in , alexithymia (β = .068, t = 3.298, p = .001), psychological dissociation (β = .077, t = 2.320, p = .021), and somatoform dissociation (β = .062, t = 2.132, p = .034) significantly mediated the relationship between CM and self-harm, while PTSD (β = –.018, t = .608, p = .543), depression (β = .008, t = .280, p = .780), and anxiety (β = .010, t = .457, p = .648) did not.

Table 5. Indirect relationships between variables.

4. Discussion

Self-harm is a prominent and relatively prevalent issue in the adolescence period, as evidenced by the high prevalence rates (Plener et al., Citation2015). Even though numerous studies have identified risk factors for the etiology and maintenance of self-harm behaviours, little is known about the underlying mechanisms. Therefore, the main goal of this study was to test an integrative model to predict the frequency of self-harm in a community sample of adolescents. Particularly, the present study was designed to investigate the direct and indirect effects of CM on the engagement in self-harm, through alexithymia, dissociation (psychoform and somatoform dissociation), internalizing (depression and anxiety), and posttraumatic symptoms.

Firstly, consistent with previous studies (Peh et al., Citation2017; Stagaki et al., Citation2022), we found that the severity of CM exposure is positively associated with the frequency of self-harm. Literature indicates that self-harm behaviours are significantly more prevalent among adolescents with history of CM, and a history of CM could be a good predictor for engaging in self-harm (Garisch & Wilson, Citation2015). In fact, as self-harm is negatively reinforced by the removal of unwanted symptoms (e.g. intrusive memories and dissociation) leading to the possible maintenance of self-harm over time. Therefore, self-harm may provide an escape from trauma-related symptoms (Hawton et al., Citation2006).

Results from our path analysis showed that alexithymia mediates the relationship between the severity of CM exposure and self-harm frequency. This finding is in line with previous research (Lüdtke et al., Citation2016; Taş Torun et al., Citation2022), and provides more support for the argument that exposure to CM may cause a disruption in affective processing and difficulties in emotional self-awareness (Moriguchi et al., Citation2006). In fact, people who self-harm have been found to have more difficulties in emotion regulation and the empirical and theoretical work introduces self-harm as a means of regulating unpleasant emotional experience (Wolff et al., Citation2019). The relationship between self-harm and alexithymia may be due to a lack of resources for more adaptive regulation strategies. People with high levels of alexithymia show hypoarousal symptoms like dearth of emotions, a sense of numbing and in general poor emotion regulation and are more likely to employ suppressive regulation strategies than reappraisal ones (Norman et al., Citation2020). More precisely, it should be noted that a history of maltreatment disrupts normal development of language to share emotional experiences and due to this deficit, children need to process traumatic events in a non-verbal manner (Van der Kolk et al., Citation1996). According to Van der Kolk et al. (Citation1996) inability to identify or describe emotions, along with feeling overwhelmed, might result in maltreated individuals expressing feelings by their own body. Self-harm may appear and develop as a compensatory, non-verbal copying strategy to interrupt a sense of psychological numbing and/ or extreme uncontrollable emotions (Yates, Citation2009).

In regard to dissociation, the WOT model, hypothesizes a noradrenergic lateral tegmental limbic forebrain-middbrain circuit, which activates the PsNS and downregulates affect (both positive and negative) leading to depersonalization (i.e. feeling detachment from oneself), derealization (feeling disconnected from the surroundings), emotional numbing, analgesia, and immobility (Bergmann, Citation2007). Several studies in the literature portray the correlation between CM, psychoform dissociation and somatoform dissociation, and it can be certainly said that exposure to CM can be considered one of the most basic etiological elements of psychoform and somatoform dissociation (Kate et al., Citation2021; Nijenhuis, Citation2001; Nijenhuis et al., Citation2003). The present findings indicate that psychoform and somatoform dissociative symptoms add considerable risk for maltreated adolescents to engage in self-harm, which is in line with the results of earlier studies (Ermağan-Çağlar et al., Citation2021; Swannell et al., Citation2012). With respect to psychological dissociation, Nock and Prinstein (Citation2004, p. 886) have noted that self-harm might play the role of an ‘autonomic positive reinforcement’. Based on this theory, self-harm is used to terminate an unpleasant dissociative state. Consistent with this theory, in their study, Kleindienst et al. (Citation2008) found that women with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) report feelings of numbness before the engagement in self-harm, but positive feelings after that. Therefore, self-harm is employed to generate feelings instead of to avoid or reduce them. Here, it is necessary to mention that this function of self-harm (autonomic positive reinforcement) is in clear contrast to the function which can be seen in some other psychological symptoms or syndromes such as depression and PTSD, where self-harm plays the role of an ‘autonomic negative reinforcement’ by reducing or avoiding painful symptoms (Nock & Prinstein, Citation2004).

Clinical observations indicate that dissociation can also manifest in somatoform ways. Somatoform dissociation consists of a wide range of somatic and sensorimotor phenomena which can be observed in numerous ways, including sensory distortion, motor weakness, freezing, numbing, and paralysis (Nijenhuis, Citation2022; Nijenhuis et al., Citation1999). In fact, a history of trauma and threat induce analgesia and numbness, which from the neurobiological point of view, result from the activation of endogenous opioid system. More precisely, there is a well-established connection between pain perception and endogenous opioids, and beta-endorphin and met-enkephalin are known as antagonists at mu opioid receptors which are related to stress-induced analgesia and thermal pain perception; a process which can justify the ‘high pain threshold’ in individuals who engage in self-harm (Sher & Stanley, Citation2008, p. 301). In line with this suggestion, Kemperman et al. (Citation1997), for instance, demonstrated that women with BPD who reported that they did not feel pain during episodes of self-harm behaviour, experienced considerably less pain in response to a standard laboratory pain stimulus as compared to those who did feel pain during self-harm episodes. However, the underlying mechanism for this hyposensitivity to pressure pain in adolescents with self-harm behaviour remains unclear. For example, Nock (Citation2009, p. 79), notes that it is unclear whether this pain analgesia is a dispositional factor due to elevated levels of endogenous opioids, emerges through habituation resulting from early traumatic events, or is a by-product of the release of endogenous opioids cause by repeated self-harm behaviour ().

Figure 2. Mediation model for self-harm based on WOT model. Notes: NEGCTQ = Neglect Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; PHNGCTQ = Physical Neglect Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; PHYSCTQ = Physical Abuse Questionnaire; SEXCTQ = Sexual Abuse Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; EMOCTQ = Emotional Abuse Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; PCLATENT = Posttraumatic Check List Hyperarousal; PCLaffect = Posttraumatic Check List Negative Cognition And Mood; PCLavoid = Posttraumatic Check List Avoidance; PCLreex = Posttraumatic Check List Re-Experience; Absorp = Absorption; Amnestic = Amnesia; Dep/Der = Depersonalization/Derealization; dep = Depression; ANX = Anxiety; DDF = Difficulty Describing Feelings; DIF = Difficulty Identifying Feelings; EOT = Externally Oriented Thinking; SDQ = Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire; DSHFREQ = Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory frequency. The numbers on the lines represent ‘beta (p-value)’.

One interesting finding of the present study was that posttraumatic symptoms did not significantly mediate the relationship between a history of CM and self-harm frequency. This finding is consistent with the study of Franzke et al. (Citation2015). A possible explanation for this lack of association might be the complexity of our path model. In other words, the picture becomes more complex when the mediating role of different variables, in particular PTSD and psychological dissociation, are be tested simultaneously. PTSD and dissociative symptoms are similar to some extent, and many people with a PTSD diagnosis also show symptoms of dissociation such as depersonalization and derealizations, a fact that has been supported by neurobiological and meta-analysis studies (Lanius et al., Citation2010; Stein et al., Citation2013). It should be also mentioned that Bremner (Citation1999) introduced Dissociative subtype of PTSD (D-PTSD); a diagnosis which focuses on symptoms of depersonalization and derealization. In this subtype of PTSD (D-PTSD), unlike the traditional hyperarousal subtype, which is marked by the predominant role of the SNS, the predominant arousal state is hyperarousal (Brantbjerg, Citation2021) Therefore, it can be concluded that the specific dissociative features associated with PTSD, which indicate the hyperactivation of the PsNS, but not PTSD itself, mediate the association between CM and self-harm. Consistent with this, Weierich and Nock (Citation2008), found that the re-experiencing and avoidance/numbing symptoms mediated the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and self-harm, while hyperarousal symptoms did not.

Finally, it was surprising that internalizing symptoms did not mediate the relationship between CM and self-harm frequency. However, this finding is in line with a study by Shenk et al. (Citation2010) that reported the partial meditational effect of internalizing symptoms only in a simple mediator model. When the posttraumatic, internalizing symptoms and emotional regulation were entered simultaneously into the model, the meditational effect of internalizing symptoms disappeared. Again, this finding indicates the complexity of these relationships, and highlights the importance of considering the interrelationship between multiple factors in the prediction of self-harm behaviour.

This study has some limitations that should be considered. First, findings from this study are based on self-report instruments, so future work should replicate these findings through semi-structured interviews and psychophysiological and behavioural measures. Second, this study was carried out using a cross-sectional design that limits the confidence in casual relationships between variables. Therefore, prospective longitudinal studies are needed to conduct a temporal analysis of the meditational effects. Finally, as using nonclinical sample restricts the generalizability of results to a clinical population, the replication of the current study in clinical settings may find more robust findings.

4.1. Conclusion

The WOT theoretical model suggests that self-harm can be used as a maladaptive coping strategy in response to the both hyper- and hypo-arousal symptoms. However, the results of the current study show that subjects with symptoms which indicate the hyperactivation of PsNS including alexithymia and dissociative, but with the exception of depression are more likely to internalize their aggression, and employ self-mutilation as a soothing strategy, compared to those who suffer from anxiety and posttraumatic symptoms (symptoms which steam from the hyperactivation of SNS). It can be argued that in hyperarousal states, people tend to use other coping strategies that do not directly target their own bodies, including externalized aggressive behaviour and abuse of drugs. So, it can be concluded that an important clinical implication of the present findings is that if hypoarousal symptoms play an important role in the development and maintenance of self-harm, clinical interventions should aim at altering such symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the students for their valuable participation in this research study, and all universities and schools staff for their assistance in facilitating study recruitment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Shima Shakiba upon request at [email protected].

References

- Abasian, B., Saffarian, Z., Masoumi, S., & Sadeghkhani, A. (2016). Validity and reliability of Persian versions of peritraumatic distress inventory (PDI) and dissociative experiences scale (DES). Acta Medica, 32(1), 1493.

- Bagby, R. M., Parker, J. D., & Taylor, G. J. (1994). The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale – I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 38(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1

- Bergmann, U. (2007). She’s come undone: A neurobiological exploration of dissociative disorders. In C. E. Forgash & M. E. Copeley (Eds.), Healing the heart of trauma and dissociation with EMDR and ego state therapy (pp. 61–89). Springer Publishing Co.

- Bernstein, D. P., Stein, J. A., Newcomb, M. D., Walker, E., Pogge, D., Ahluvalia, T., Stokes, J., Handelsman, L., Medrano, M., & Desmond, D. (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the childhood trauma questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22059

- Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders–fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000254

- Brantbjerg, M. H. (2021). Sitting on the edge of an abyss together. A methodology for working with hypo-arousal as part of trauma therapy. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 16(2), 120–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2021.1876768

- Bremner, J. D. (1999). Acute and chronic responses to psychological trauma: Where do we go from here? American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(3), 349–351. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.156.3.349

- Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation: Progress in the Dissociative Disorders, 6(1), 16–27

- Cavanagh, A., Caputi, P., Wilson, C. J., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2016). Gender differences in self-reported depression and co-occurring anxiety and stress in a vulnerable community population. Australian Psychologist, 51(6), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12184

- Chin, W. W. (2009). How to write up and report PLS analyses. In V. E. Vinzi, W. W. Chin, J. Henseler, & H. Wang (Eds.), Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 655–690). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Chin, W. W., Marcolin, B. L., & Newsted, P. R. (2003). A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Information Systems Research, 14(2), 189–217. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.2.189.16018

- Corrigan, F., Fisher, J., & Nutt, D. (2011). Autonomic dysregulation and the window of tolerance model of the effects of complex emotional trauma. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881109354930

- Ermağan-Çağlar, E., Öztürk, E., Derin, G., & Tuğba, T.-K. (2021). Investigation of the relationship among childhood traumas and self-harming behaviours, depression, psychoform and somatoform dissociation in female university students. Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Journal, 11(62), 383–402.

- Falk, R. F., & Miller, N. B. (1992). A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press.

- Ford, J. D., & Gómez, J. M. (2015). The relationship of psychological trauma and dissociative and posttraumatic stress disorders to nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality: A review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(3), 232–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.989563.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Franzke, I., Wabnitz, P., & Catani, C. (2015). Dissociation as a mediator of the relationship between childhood trauma and nonsuicidal self-injury in females: A path analytic approach. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(3), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2015.989646

- Garisch, J. A., & Wilson, M. S. (2015). Prevalence, correlates, and prospective predictors of non-suicidal self-injury among New Zealand adolescents: Cross-sectional and longitudinal survey data. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-015-0055-6

- Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012779403943

- Gratz, K. L., Tull, M., & Levy, R. (2014). Randomized controlled trial and uncontrolled 9-month follow-up of an adjunctive emotion regulation group therapy for deliberate self-harm among women with borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 44(10), 2099–2112. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291713002134

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hawton, K., Rodham, K., & Evans, E. (2006). By their own young hand: Deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideas in adolescents. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E., & O'Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. The Lancet, 379(9834), 2373–2382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In T. Cavusgil, R. R. Sinkovics, & P. N. Ghauri (Eds.), New challenges to international marketing (pp. 277–319). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Henseler, J., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Computational Statistics, 28(2), 565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-012-0317-1

- Kate, M.-A., Jamieson, G., & Middleton, W. (2021). Childhood sexual, emotional, and physical abuse as predictors of dissociation in adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 30(8), 953–976. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2021.1955789

- Kefeli, M. C., Turow, R. G., Yıldırım, A., & Boysan, M. (2018). Childhood maltreatment is associated with attachment insecurities, dissociation and alexithymia in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Research, 260, 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.026

- Kemperman, I., Russ, M. J., Clark, W. C., Kakuma, T., Zanine, E., & Harrison, K. (1997). Pain assessment in self-injurious patients with borderline personality disorder using signal detection theory. Psychiatry Research, 70(3), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-1781(97)00034-6

- Kleindienst, N., Bohus, M., Ludäscher, P., Limberger, M. F., Kuenkele, K., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., Chapman, A. L., Reicherzer, M., Stieglitz, R.-D., & Schmahl, C. (2008). Motives for nonsuicidal self-injury among women with borderline personality disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196(3), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181663026

- Klonsky, E. D., May, A. M., & Glenn, C. R. (2013). The relationship between nonsuicidal self-injury and attempted suicide: Converging evidence from four samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030278

- Klonsky, E. D., & Moyer, A. (2008). Childhood sexual abuse and non-suicidal self-injury: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192(3), 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030650

- Klonsky, E. D., Muehlenkamp, J., Lewis, S. P., & Walsh, B. (2011). Nonsuicidal self-injury (Vol. 22). Hogrefe Publishing.

- Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 1501–1508. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501

- Knipe, D., Padmanathan, P., Newton-Howes, G., Chan, L. F., & Kapur, N. (2022). Suicide and self-harm. The Lancet, 399(10338), 1903–1916. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00173-8

- Kranzler, A., Fehling, K. B., Anestis, M. D., & Selby, E. A. (2016). Emotional dysregulation, internalizing symptoms, and self-injurious and suicidal behavior: Structural equation modeling analysis. Death Studies, 40(6), 358–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2016.1145156

- Lang, C. M., & Sharma-Patel, K. (2011). The relation between childhood maltreatment and self-injury: A review of the literature on conceptualization and intervention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838010386975

- Lanius, R. A., Vermetten, E., Loewenstein, R. J., Brand, B., Schmahl, C., Bremner, J. D., & Spiegel, D. (2010). Emotion modulation in PTSD: Clinical and neurobiological evidence for a dissociative subtype. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(6), 640–647. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09081168

- Leguina, A. (2015). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Taylor & Francis.

- Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1183–1192. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170700027X

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Lüdtke, J., In-Albon, T., Michel, C., & Schmid, M. (2016). Predictors for DSM-5 nonsuicidal self-injury in female adolescent inpatients: The role of childhood maltreatment, alexithymia, and dissociation. Psychiatry Research, 239, 346–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.026

- Moriguchi, Y., Ohnishi, T., Lane, R. D., Maeda, M., Mori, T., Nemoto, K., Matsuda, H., & Komaki, G. (2006). Impaired self-awareness and theory of mind: An fMRI study of mentalizing in alexithymia. Neuroimage, 32(3), 1472–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.04.186

- Nawaz, R. F., Anderson, J. K., Colville, L., Fraser-Andrews, C., & Ford, T. J. (2024). Interventions to prevent or manage self-harm among students in educational settings – a systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 29(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12634

- Nijenhuis, E., Van Dyck, R., Ter Kuile, M., Mourits, M., Spinhoven, P., & Van der Hart, O. (2003). Evidence for associations among somatoform dissociation, psychological dissociation and reported trauma in patients with chronic pelvic pain. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 24(2), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.3109/01674820309042806

- Nijenhuis, E. R. (2001). Somatoform dissociation: Major symptoms of dissociative disorders. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 1(4), 7–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J229v01n04_02

- Nijenhuis, E. R. (2022). Somatoform dissociation, agency, and consciousness. In M. J. Dorahy, S. N. Gold, & J. A. O'Neil (Eds), Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: Past, present, future (pp. 528–546). Routledge.

- Nijenhuis, E. R., Spinhoven, P., van Dyck, R., van der Hart, O., & Vanderlinden, J. (1998). Psychometric characteristics of the somatoform dissociation questionnaire: A replication study1. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 67(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012254

- Nijenhuis, E. R., Van Dyck, R., Spinhoven, P., van der Hart, O., Chatrou, M., Vanderlinden, J., & Moene, F. (1999). Somatoform dissociation discriminates among diagnostic categories over and above general psychopathology. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 33(4), 511–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.1999.00601.x

- Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x

- Nock, M. K. (2014). The Oxford handbook of suicide and self-injury. Oxford University Press.

- Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885

- Norman, H., & Borrill, J. (2015). The relationship between self-harm and alexithymia. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 56(4), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12217

- Norman, H., Oskis, A., Marzano, L., & Coulson, M. (2020). The relationship between self-harm and alexithymia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 61(6), 855–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12668

- Nunnally, J., & Bernstein, I. (1994). Psychometric theory. McCraw-Hill.

- Ogden, P., Minton, K., & Pain, C. (2006). Trauma and the body: A sensorimotor approach to psychotherapy (Norton series on interpersonal neurobiology). WW Norton.

- Peh, C. X., Shahwan, S., Fauziana, R., Mahesh, M. V., Sambasivam, R., Zhang, Y., Ong, S. H., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2017). Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking child maltreatment exposure and self-harm behaviors in adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 67, 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.03.013

- Plener, P. L., Schumacher, T. S., Munz, L. M., & Groschwitz, R. C. (2015). The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 2(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-014-0024-3

- Reis, D. L., Ribeiro, M., Couto, I., Maia, N., Bonavides, D., Botelho, A. C., Sena, C. L., Hemanny, C., & de Oliveira, I. R. (2024). Correlations between childhood maltreatment and anxiety and depressive symptoms and risk behaviors in school adolescents. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 46, e20210456. https://doi.org/10.47626/2237-6089-2021-0456

- Ross, E., O'Reilly, D., O'Hagan, D., & Maguire, A. (2023). Mortality risk following self-harm in young people: A population cohort study using the Northern Ireland registry of self-harm. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(7), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13784

- Shenk, C. E., Noll, J. G., & Cassarly, J. A. (2010). A multiple mediational test of the relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(4), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9456-2

- Shenk, C. E., O’Donnell, K. J., Pokhvisneva, I., Kobor, M. S., Meaney, M. J., Bensman, H. E., Allen, E. K., & Olson, A. E. (2022). Epigenetic age acceleration and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder following exposure to substantiated child maltreatment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(5), 651–661. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2020.1864738

- Sher, L., & Stanley, B. H. (2008). The role of endogenous opioids in the pathophysiology of self-injurious and suicidal behavior. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(4), 299–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110802324748

- Siegel, D. (1999). The developing mind. The Guilford.

- Smith, N. B., Kouros, C. D., & Meuret, A. E. (2014). The role of trauma symptoms in nonsuicidal self-injury. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 15(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013496332

- Spinhoven, P., Penninx, B. W., Hickendorff, M., van Hemert, A. M., Bernstein, D. P., & Elzinga, B. M. (2014). Childhood trauma questionnaire: Factor structure, measurement invariance, and validity across emotional disorders. Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 717–729. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000002

- Stagaki, M., Nolte, T., Feigenbaum, J., King-Casas, B., Lohrenz, T., Fonagy, P., Montague, P. R., & Personality and Mood Disorder Research Consortium (2022). The mediating role of attachment and mentalising in the relationship between childhood maltreatment, self-harm and suicidality. Child Abuse & Neglect, 128, Article 105576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105576

- Stänicke, L. I., Hermansen, M. H., & Halvorsen, M. S. (2024). A transitional object for relatedness and self-development – a meta-synthesis of youths’ experience of engagement in self-harm content online. Child & Family Social Work, 29(1), 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.13058

- Stein, D. J., Koenen, K. C., Friedman, M. J., Hill, E., McLaughlin, K. A., Petukhova, M., Ruscio, A. M., Shahly, V., Spiegel, D., & Borges, G. (2013). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: Evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biological Psychiatry, 73(4), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.022

- Swannell, S., Martin, G., Page, A., Hasking, P., Hazell, P., Taylor, A., & Protani, M. (2012). Child maltreatment, subsequent non-suicidal self-injury and the mediating roles of dissociation, alexithymia and self-blame. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(7–8), 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.005

- Taş Torun, Y., Gul, H., Yaylali, F. H., & Gul, A. (2022). Intra/interpersonal functions of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with major depressive disorder: The role of emotion regulation, alexithymia, and childhood traumas. Psychiatry, 85(1), 86–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2021.1989854

- Tuisku, V., Kiviruusu, O., Pelkonen, M., Karlsson, L., Strandholm, T., & Marttunen, M. (2014). Depressed adolescents as young adults–predictors of suicide attempt and non-suicidal self-injury during an 8-year follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152, 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.09.031

- Van der Kolk, B. A., Pelcovitz, D., Roth, S., Mandel, F. S., McFarlane, A., & Herman, J. L. (1996). Dissociation, somatization, and affect dysregulation: The complexity of adaptation to trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(7), 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.7.83

- Weierich, M. R., & Nock, M. K. (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms mediate the relation between childhood sexual abuse and nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.39

- Wolff, J. C., Thompson, E., Thomas, S. A., Nesi, J., Bettis, A. H., Ransford, B., Scopelliti, K., Frazier, E. A., & Liu, R. T. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 59, 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.03.004

- Yates, T. M. (2009). Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to nonsuicidal self-injury. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 117–137). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11875-007

- Zhang, Z., Wang, X., Qiu, H., Wang, Y., Li, J., Ju, Y., & Luo, Q. (2024). Childhood maltreatment and anxiety, depression and self-harm behaviors : a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Research square [Preprint]. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-3909957/v1