ABSTRACT

Background: Mobile health applications (apps) are considered to complement traditional psychological treatments for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). However, the use for clinical practice and quality of available apps is unknown.

Objective: To assess the general characteristics, therapeutic background, content, and quality of apps for PTSD and to examine their concordance with established PTSD treatment and self-help methods.

Method: A web crawler systematically searched for apps targeting PTSD in the British Google Play and Apple iTunes stores. Two independent researchers rated the apps using the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS). The content of high-quality apps was checked for concordance with psychological treatment and self-help methods extracted from current literature on PTSD treatment.

Results: Out of 555 identified apps, 69 met the inclusion criteria. The overall app quality based on the MARS was medium (M = 3.36, SD = 0.65). Most apps (50.7%) were based on cognitive behavioural therapy and offered a wide range of content, including established psychological PTSD treatment methods such as processing of trauma-related emotions and beliefs, relaxation exercises, and psychoeducation. Notably, data protection and privacy standards were poor in most apps and only one app (1.4%) was scientifically evaluated in a randomized controlled trial.

Conclusions: High-quality apps based on established psychological treatment techniques for PTSD are available in commercial app stores. However, users are confronted with great difficulties in identifying useful high-quality apps and most apps lack an evidence-base. Commercial distribution channels do not exploit the potential of apps to complement the psychological treatment of PTSD.

Antecedentes: se han discutido las aplicaciones móviles de salud (apps) para complementar los tratamientos psicológicos tradicionales para el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT). Sin embargo, se desconoce su uso para la práctica clínica y la calidad de las aplicaciones disponibles.

Objetivo: evaluar las características generales, bases terapéuticas, contenido y calidad de las aplicaciones para el TEPT y examinar su concordancia con el tratamiento y los métodos de autoayuda establecidos para el TEPT.

Método: un rastreador web buscó sistemáticamente aplicaciones dirigidas al TEPT en las tiendas británicas Google Play y Apple iTunes. Dos investigadores independientes calificaron las aplicaciones utilizando la Escala de calificación de aplicaciones móviles (ECAM). El contenido de las aplicaciones de alta calidad se verificó para concordancia con el tratamiento psicológico y los métodos de autoayuda extraídos de la literatura actual sobre el tratamiento del TEPT.

Resultados: De 555 aplicaciones identificadas, 69 cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. La calidad general de las aplicaciones basándose en el ECAM fue media (M = 3.36, SD = .65). La mayoría de las aplicaciones (50.7%) estaban basadas en Terapia Cognitivo Conductual y ofrecían un amplio rango de contenido, incluyendo métodos de tratamiento psicológico del TEPT establecidos, como procesamiento de emociones y creencias relacionadas con el trauma, ejercicios de relajación y psicoeducación. Digno de notar, los estándares de protección de datos y privacidad fueron deficientes en la mayoría de las aplicaciones y solo una aplicación (1.4%) fue evaluada científicamente en un ensayo controlado aleatorio.

Conclusiones: las aplicaciones de alta calidad basadas en técnicas de tratamiento psicológico establecidas para el TEPT están disponibles en las App-stores comerciales. Sin embargo, los usuarios se enfrentan a grandes dificultades para identificar aplicaciones de alta calidad útiles y la mayoría de las aplicaciones carecen de una base de evidencia. Los canales de distribución comercial no explotan el potencial de las apps para complementar el tratamiento psicológico del TEPT.

背景: 讨论了移动健康应用程序 (apps), 以补充对创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 的传统心理治疗方法。但是, 临床实践的使用和可用应用程序的质量尚不清楚。

目标: 评估PTSD应用程序的一般特征, 治疗背景, 内容和质量, 并考查其与既定PTSD治疗方法和自助方法的一致性。

方法: 使用网络爬虫在英国Google Play和Apple iTunes商店中系统地搜索针对PTSD的应用程序。两名独立的研究人员使用《移动应用程序评估量表》 (MARS) 对应用程序进行了评估。考查了高质量应用程序的内容是否与心理治疗和从PTSD治疗现有文献中摘录的自助方法相一致。

结果: 在555个被识别的应用程序中, 有69个符合纳入标准。基于MARS的总体应用质量为中等 (M = 3.36, SD = .65) 。大多数应用程序 (50.7%) 基于认知行为疗法, 并且提供了广泛的内容, 包括已有的心理PTSD治疗方法, 例如处理与创伤有关的情绪和信念, 放松锻炼和心理教育。值得注意的是, 大多数应用程序中的数据保护和隐私标准都很差, 并且在一项随机对照试验中仅有一个应用程序 (1.4%) 进行了科学评估。

结论: 基于成熟的PTSD心理治疗技术的高质量应用程序可在商业应用商店中获得。但是, 用户在识别有用的高质量应用程序时面临很大的困难, 并且大多数应用程序都缺乏证据基础。商业发行渠道没有充分开发应用程序的潜能来补充PTSD的心理治疗。

Abbreviations: CI: confidence interval; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; M: mean; N: number of sample size; NICE: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; p: probability value; PCL-5: PTSD Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PMR: progressive muscle relaxation; PTSD: Posttraumatic stress disorder; r: correlation coefficient; RCT: randomized control trial; SD: standard deviation; ω: Omega; WMH: World Mental Health

1. Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prevalent condition with an estimated cross-national lifetime prevalence of 3.9% in the general population and 5.6% in trauma exposed people (Koenen et al., Citation2017). The average incidence rate after experiencing trauma is estimated at 15.9% (Alisic et al., Citation2014). PTSD is associated with substantial disease burden for individuals, families, and communities (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013; Bromet, Karam, Koenen, & Stein, Citation2018; Kessler et al., Citation2009; Miller & Sadeh, Citation2014; Sareen, Citation2014; Walker et al., Citation2003).

Evidence-based psychological treatment methods for PTSD include trauma‐focused cognitive behavioural therapy, prolonged exposure therapy, cognitive processing therapy, narrative exposure therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) (Bisson, Roberts, Andrew, Cooper, & Lewis, Citation2013; Charney, Hellberg, Bui, & Simon, Citation2018; Mueser et al., Citation2015; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], Citation2018). Cognitive behavioural therapy with a trauma focus typically involves psychoeducation, homework, exposure and cognitive work as well as relaxation and stress management techniques (Berliner et al., Citation2019). In addition to psychological treatment methods, self-help guides have been developed to help people cope with traumatic experiences (Northumberland, Tyne and Wear [NHS], Citation2016).

Thus, several effective treatments have been developed; however, mental healthcare for PTSD remains insufficient across countries (Kazlauskas et al., Citation2016; Koenen et al., Citation2017; Sareen, Citation2014). Treatment-seeking is low and delayed, and the supply of treatment itself is insufficient even in countries with a generally appropriate health system (Koenen et al., Citation2017; Zammit et al., Citation2018). Main barriers to seeking professional help after trauma include limited resources on the part of the health system, and on the part of the affected person, time constraints, a lack of knowledge about services, fear of negative social consequences, stigma, and shame (Kantor, Knefel, & Lueger-Schuster, Citation2017).

Mobile health applications (apps) are often utilized to complement established treatment methods and to improve treatment accessibility (Bakker, Kazantzis, Rickwood, & Rickard, Citation2016; Donker et al., Citation2013). They can be administered independent of time and place at relatively low costs (Boulos, Brewer, Karimkhani, Buller, & Dellavalle, Citation2014; Hussain et al., Citation2015), can provide information about mental healthcare, and can be used anonymously, which might be appealing to those who fear stigmatization (Andrade et al., Citation2014; Donker et al., Citation2013). In addition, in blended care models, apps can improve psychological treatment approaches through functions like activity and symptom monitoring, mobile sensing, or automatically displayed tiny tasks in everyday life, which repeat contents of the therapy (Donker et al., Citation2013; Ebert et al., Citation2018). Today, mental health apps are available in abundance in commercial app stores, including apps for PTSD and related disorders, and they are used by the general public (Owen et al., Citation2015).

However, the usage of apps is also accompanied by several risks and challenges including privacy and data protection risks as well as the lack of an informed consent (Hussain et al., Citation2015; Luxton, McCann, Bush, Mishkind, & Reger, Citation2011), possible harms in case of device failure, especially for patients relying on functional apps (Luxton et al., Citation2011), and a low quality of evidence of effectiveness as well as the absence of quality standards for the development of apps (Byambasuren, Sanders, Beller, & Glasziou, Citation2018; Hussain et al., Citation2015; Olff, Citation2015).

Therefore, this systematic review aimed to evaluate the content and quality of PTSD apps available on the Google Play and Apple iTunes stores and to set them in perspective with established psychological treatment methods for PTSD.

2. Method

2.1. Search strategy and selection procedure

A web crawler (an automated web search engine) was used to systematically screen the British Google Play and Apple iTunes stores with trauma-related search terms (‘trauma’, ‘post-traumatic stress disorder’, ‘traumatic stress’, ‘moral injury’, ‘post traumatic neurosis’, and ‘flashback’). The identified apps were screened and downloaded if the title or description indicated that the app was (a) conceptualized for mental disorders, (b) provided in the English or German language (in accordance with the authors’ language skills), and (c) officially available in the British Google Play or Apple iTunes stores. Downloaded apps were eligible for inclusion if (a) they focused on PTSD, contained a PTSD-specific section, or were useful for PTSD according to the app store description, and (b) they were fully functional to enable an assessment. Dead links were retrieved multiple times and technical problems (e.g. app does not start) were verified on at least two separate devices.

2.2. Quality rating

Two independent reviewers (students and graduates of clinical psychology (JS, KS) trained and supervised by a licenced psychotherapist (LS)) acquired and evaluated the data of the included apps using the German version of the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS-G) (Messner et al., Citation2019; Stoyanov et al., Citation2015). The MARS-G is a reliable and valid scale for the quality assessment of apps (Messner et al., Citation2019). The overall MARS-G score shows a good internal consistency (ω = .82, 95%-confidence interval (CI): .76 to .86) and a high intraclass-correlation (Fleiss, Citation1999) (ICC: .83, 95%-CI: .82 to .85) (Messner et al., Citation2019). The subscales demonstrate internal consistencies ranging from acceptable to excellent (ω = .72 to .93) (Messner et al., Citation2019).

The quality rating of the MARS-G is based on a 5-point scale (1-inadequate, 2-poor, 3-acceptable, 4-good, and 5-excellent) and includes 19 items that are divided into four subscales: (A) engagement (5 items: fun, interest, individual adaptability, interactivity, target group), (B) functionality (4 items: performance, usability, navigation, gestural design), (C) aesthetics (3 items: layout, graphics, visual appeal), and (D) information quality (7 items: accuracy of app description, goals, quality of information, quantity of information, quality of visual information, credibility, evidence base). For the evaluation of the overall quality, the total score was determined from the four main subscales (Stoyanov et al., Citation2015). Mean scores (M) and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for the MARS total scores and subscales.

In addition to the four subscales used for the quality rating, three additional categories were assessed in accordance with the MARS-G (Messner et al., Citation2019): (E) therapeutic gain (4 items: gain for patients, gain for therapists, risks and side effects, ease of implementation into routine healthcare), (F) subjective quality (4 items: recommendation, frequency of use, willingness to pay, overall star rating), and (G) perceived impact (6 items: awareness, knowledge, attitudes, intention to change, help seeking, behavioural change).

Prior to the rating process, the reviewers underwent an online training (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5vwMiCWC0Sc&t=1367s, last updated on 31 July 2019). In the training, the subscales of the MARS-G rating are presented, the scoring is explained, and an app can be rated in an exercise. The interrater reliability (IRR) between the reviewers was calculated using the ICC. If the ICC had fallen below a minimum value of .75 (Fleiss, Citation1999), a third reviewer would have been called in. The two ratings of each app were averaged for all calculations.

2.3. User star ratings

User ratings (one to five stars) were extracted from the app stores. Means and standard deviations were calculated for the user ratings and bivariate correlations between the user ratings and the means of the MARS total score and subscales were calculated, whereby only user ratings with a minimum number of three ratings were included in the analyses.

2.4. General characteristics

The classification section of the MARS-G captures descriptive information of apps and was slightly modified in this study to cover the following dimensions: (a) app name, (b) platform (android or iOS), (d) content-related subcategory, (e) specific target group, (f) price, (g) provision of important information (e.g. information on how to find therapy, emergency contact), (h) embedded in a therapeutic programme, (i) technical aspects, (j) data protection and privacy, (k) user rating, (l) number of conducted randomized controlled trials (RCT). We searched for evaluation studies on the manufacturers’ homepage, in the description in the app stores, the app itself as well as google scholar and Medline.

2.5. Therapeutic background and content

The therapeutic background and content of the apps were captured using the MARS-G. The following therapeutic backgrounds were distinguished: (a) behaviour therapy, (b) cognitive behavioural therapy, (c) third-wave behaviour therapy, (d) systemic therapy, (e) psychodynamic psychotherapy, (f) humanistic therapy, (g) integrative therapy, and (h) other. Moreover, the presence of the following contents has been investigated: (a) information/psychoeducation, (b) assessment, (c) monitoring and tracking, (d) feedback, (e) skill training, (f) exposure, (g) mindfulness, (h) relaxation, (i) breathing, (j) body exercises, (k) resource orientation, (l) tips and advices, and (m) other.

2.6. Concordance with treatment and self-help methods for PTSD

We derived key components of psychological treatment from scientific literature (Beck & Sloan, Citation2012; Charney et al., Citation2018; Schnyder et al., Citation2015; Watkins, Sprang, & Rothbaum, Citation2018), and self-help methods for PTSD from specialized literature (Beck & Sloan, Citation2012; NHS, Citation2016). Apps that were specifically developed for PTSD and had a MARS total score in the upper quartile of all included apps (high-quality apps) were compared with the treatment methods identified (see Appendix).

3. Results

3.1. Search

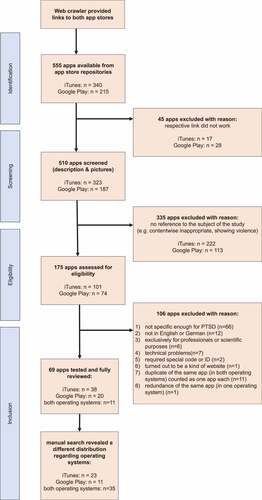

displays the process of inclusion. From 555 identified apps, a total of 69 apps (12.4%) were included in the analyses. 23 apps (33.3%) were developed for iOS, 11 apps (15.9%) for android, and 35 apps (50.7%) for both operating systems.

3.2. General characteristics

The general characteristics of the included apps are shown in detail in . The majority of the apps were specifically developed for PTSD or contained a PTSD-specific section (n = 54 (78.26%)), were not embedded in a therapeutic programme (n = 59 (85.5%)), and were free of charge (n = 55 (79.7%)). The costs of the 14 apps (20.3%) that required payment ranged from EUR 2.29 to EUR 38.99 (M = 8.24, SD = 10.1). The most frequent specific target group of the included apps for PTSD were soldiers and veterans (n = 13 (18.8%)).

Table 1. Descriptive data for the apps included in the MARS-G rating

Passwords and logins were required in n = 7 (10.1%) apps, n = 12 (17.4%) provided a privacy statement. No app had a user star rating on the Apple iTunes store, 27 apps on the Google Play store had a user star rating. The median of the user ratings (maximum five stars) was 4.3 (M = 4.2, SD = 0.7) (last updated on 15 May 2019). One app (‘PTSD coach’) was evaluated in several studies, including an RCT (Kuhn et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Miner et al., Citation2016; Possemato et al., Citation2016; Wickersham, Petrides, Williamson, & Leightley, Citation2019). The ‘CBT-I coach’ app was evaluated in a feasibility pilot RCT (Koffel et al., Citation2018). One RCT evaluated the web-version of the ‘VetChange’ app (Brief et al., Citation2013). For two apps (‘PE coach’ and ‘PTSD Family Coach’), we identified user experience studies (Kuhn et al., Citation2015; Owen et al., Citation2017; Reger, Skopp, Edwards-Stewart, & Lemus, Citation2015).

3.3. Quality rating

displays the results from the MARS-G rating. The total score showed a good level of IRR (2-way mixed ICC = .87, 95%-CI .79 to .92). The IRRs of the MARS-G subscales were moderate to excellent (ICC = .70-.91). The overall quality of the apps was average, with M = 3.36 (SD = 0.65), ranging from M = 1.95 to M = 4.7. Concerning the four main subscales, functionality was the highest-rated (M = 3.82, SD = 0.64), followed by aesthetics (M = 3.36, SD = 0.82), information quality (M = 3.22, SD = 0.79), and user engagement (M = 3.03, SD = 0.81). The additional subscales showed lower rating scores: the mean for therapeutic gain was M = 2.67 (SD = 0.76), for subjective quality M = 2.54 (SD = 0.89), and for perceived impact M = 2.59 (SD = 0.85). The means of all subscales of the MARS-G rating are illustrated in . No significant bivariate correlations were found between the user ratings and the overall total score of the MARS-G (r(27) = .28, p > 0.05) or MARS-G subscales (r(27) = .09-.32, p > .05).

Table 2. Means of the MARS-G (Messner et al., Citation2019) ratings in descending order of the total mean score (range: 1 to 5)

3.4. Therapeutic background and content

shows the the rapeutic background and content of the apps. The most common therapeutic background was cognitive behavioural therapy, for which elements were found in more than half of the apps (n = 35 (50.7%)).

Table 3. Therapeutic background and content of the apps included in the MARS-G rating

As to content, 44 apps (63.8%) offered elements of mindfulness, relaxation, breathing, or body exercises. This included a variety of techniques, such as meditation, guided positive imagery, grounding exercises, or progressive muscle relaxation (PMR), mainly guided by audio recordings. 41 apps (59.4%) included psychoeducational content about PTSD, of which 31 apps addressed the term ‘PTSD’, 23 provided information on the progression and prognosis of PTSD, 22 dealt with the aetiology and pathogenesis, and eight with its descriptive epidemiology. Provided tips and advice (n = 32 apps, 46.4%) ranged from how to deal with difficult emotions, cognitions (e.g. changing perspective), and behaviour (e.g. drinking behaviour). 30 apps (43.5%) involved monitoring and tracking that encompassed various functions, such as pre- and post-exercise distress measurements. Assessment sections were offered by 28 apps (40.6%), half of which used validated scientific questionnaires (e.g. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5)(Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, Citation2015), Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)(Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, Citation2001)). None of the apps made a diagnosis at the end of the assessment; 19 of these apps provided an explanation of the results; 17 apps showed a sum score of the assessment; 18 apps recommended seeking further help. Twelve apps referred to a link or phone number to directly contact professionals if their assessment revealed severe symptoms.

3.5. Concordance with treatment and self-help methods for PTSD

Twelve apps were specifically developed for PTSD and had a MARS total score in the upper quartile of all included apps (M ≥ 3.73) (see ). All of these apps included psychoeducational content. Eleven apps (91.7%) integrated modules for processing trauma-related emotions and beliefs, and ten apps (83.3%) included modules for cognitive processing, restructuring, or meaning making. Both breathing training and relaxation exercises (e.g. PMR, grounding techniques, body scan) were also offered by ten apps (83.3%). Nine apps (75.0%) comprised teaching emotional regulation and coping skills. Eight apps (66.7%) dealt with the acceptance of support and asking for help from others. Seven apps (58.3%) included self-care and help in structuring everyday life. Five apps (41.7%) offered the identification of triggers for flashbacks. Imaginative or in vivo exposure as well as homework assignments were offered by two apps (16.7%). A form of reorganizing memory processes was integrated in one app (8.3%). Exercises related to EMDR were included by none of the apps in the upper quartile of ratings.

Table 4. Psychological treatment and self-help methods of apps in the upper quartile

4. Discussion

This is the first study that systematically assessed the quality, general characteristics, and content of apps for PTSD. In addition, we reviewed the concordance of the content of high-quality apps with that of established PTSD-specific treatment and self-help methods.

Our search resulted in a plethora of available apps in Google Play and Apple iTunes stores (N = 555), of which 54 were operable and included PTSD-specific content. For another 15 apps, the app stores description stated their use for treating PTSD, but no PTSD-specific content could be identified. The MARS-G ratings resulted in an average overall quality and most of the identified apps lacked a scientific evidence-base. Yet, apps in the upper quartile of all rated apps that were specifically tailored for PTSD showed good consistency with known psychological treatment methods for PTSD. The most frequent therapeutic background of the included apps was cognitive behavioural therapy, comprising a range of established psychological treatment elements like psychoeducation, mood tracking, cognitive restructuring, processing of trauma-related emotions and beliefs, and relaxation exercises. The absence of an evidence-base is consistent with prior reviews on the quality of apps (Sucala et al., Citation2017; Terhorst, Rathner, Baumeister, & Sander, Citation2018), and can partly be explained by the discrepancy between the fast-paced nature of technological development and the slow pace of research processes. Research innovation commonly takes a long time from development to full implementation of health interventions (Balas & Boren, Citation2000; Brown et al., Citation2012; Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, Citation2003). Technology-based interventions may already be outdated by the time they are validated. To overcome this discrepancy, Mohr and colleagues proposed a methodologic framework of continuous evaluation of evolving behavioural intervention technologies (CEEBIT) through systematic prospective analyses (Mohr, Cheung, Schueller, Brown, & Duan, Citation2013).

Many apps, however, only transfer pen and paper versions of psychological tools (e.g. mood diaries) into digital devices. In those cases, a decline in symptom burden when used as stand-alone interventions is rather unlikely, which makes efficacy trials dispensable. Scientific evaluations should therefore differentiate where effectiveness trials and where other study formats (e.g. usability studies) are appropriate.

An indispensable operation, however, is a valuation of potential iatrogenic effects of apps. In the case of PTSD, unguided exposure without a treatment plan might increase symptom severity (Cuijpers & Schuurmans, Citation2007). Furthermore, apps might be used in place of regular health services and thus prevent or at least delay the application of first-line treatment options (Price et al., Citation2014). As a minimal standard, apps that are listed in market categories such as medical or health apps should, therefore, include a disclaimer indicating that the app does not substitute regular treatment and incorporate information on how to access other treatment options. This was the case in 64%, respectively 45% of the apps reviewed in this study.

A further concern relates to the inadequate data protection and privacy declarations revealed in many apps in this study. This finding is consistent with the results of prior investigations (O’Loughlin, Neary, Adkins, & Schueller, Citation2019; Sucala et al., Citation2017; Terhorst et al., Citation2018). Even more concerning is the fact that many apps transmit data to commercial entities without disclosing this (Huckvale, Torous, & Larsen, Citation2019). This constitutes a serious threat to patients’ data privacy and illustrates the need for developers to be more strictly bound to security, data protection, and privacy regulations (Armontrout, Torous, Fisher, Drogin, & Gutheil, Citation2016). Until then, clinicians and consumers need to be careful when using apps (Armontrout et al., Citation2016).

The use of apps in clinical practice is further afflicted by great difficulties to identify an appropriate app of high quality. Our search yielded an abundance of available hits (N = 555), of which only a minority of apps had PTSD-specific content. Additionally, the reviewed apps were of varying, overall average quality and neither one of the subscales nor the overall quality were significantly related to the user ratings of the apps. This is a constant finding when reviewing commercially available apps (Bardus, van Beurden, Smith, & Abraham, Citation2016; Terhorst et al., Citation2018) and makes it very difficult for help-seekers to find an app that suits their needs. In order to overcome this problem, numerous international initiatives have started to develop platforms promoting safe and high-quality apps: www.psyberguide.org, www.healthnavigator.com, www.vichealth.vic.gov.au, and www.mhad.science are examples of services providing quality-reviews based on the MARS as well as information about scope, functionality, privacy, and security of apps. Such platforms can contribute to facilitating the accessibility of health-related apps.

Beyond that, a group of international experts from research, industry, and health systems recommend international collaborations to establish appropriate standards and practices for digital interventions (Torous et al., Citation2019). They called for unified standards in terms of usability, effectiveness, data security, and data integration (Torous et al., Citation2019). In the context of PTSD, Schellong, Lorenz, and Weidner (Citation2019) developed a model covering the process of building, assessing, and implementing apps. Another approach proposed by Muñoz and colleagues is a global ‘digital apothecary’ that offers apps and web-based interventions for specific health conditions (Muñoz et al., Citation2018). In their vision paper, they emphasize the need to develop apps for particularly vulnerable target groups, including those affected by war, conflict, and other psychological traumas (Muñoz et al., Citation2018), as also pursued by Sijbrandij et al. (Citation2017). Our search revealed soldiers and veterans as the most frequently addressed target group, which corresponds to the increased prevalence of PTSD in this group (Xue et al., Citation2015). However, other target groups, such as victims of sexual or domestic violence or refugees (Alisic et al., Citation2014; Kessler et al., Citation2017; Kizilhan & Noll-Hussong, Citation2018), are also frequently affected by PTSD symptoms, for which no tailored app could be found.

This study has some limitations. First, due to the fast-paced nature of the development of apps (Larsen, Nicholas, & Christensen, Citation2016; Mohr et al., Citation2013), it is conceivable that some of the illustrated apps are no longer accessible or their content has changed. Second, this review only covered apps in British Google Play and Apple iTunes stores found by the web crawler using the given search terms. Hence, the findings might not be generalizable to other app stores, and some apps might not have been identified. Third, the conducted search was limited to PTSD specific keywords. As a result, useful apps for other trauma- and stressor-related disorders might not be included (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Future studies should investigate the keywords used by people affected by trauma- and stressor-related disorders when searching app stores to conduct searches from a user perspective. Fourth, due to language limitations of the authors, only apps in the English and German language could be included. Fifth, the MARS was chosen for the ratings because it is a currently widespread tool for classifying and evaluating the quality of apps for a variety of health conditions (Bardus et al., Citation2016; Chavez et al., Citation2017; Mani, Kavanagh, Hides, & Stoyanov, Citation2015; Santo et al., Citation2016). Future studies may repeat this research using different evaluation instruments, such as the Enlight (Baumel, Faber, Mathur, Kane, & Muench, Citation2017) or the App Evaluation Model (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2019), to benefit from specific emphases of different rating tools.

5. Conclusion

This is the first review that systematically examined apps for PTSD in the British app stores. The reviewed apps showed a medium overall quality (M = 3.36, SD = 0.65) and offered a wide range of functionalities, including digital versions of established psychological treatment and self-help methods. Some apps might help to improve PTSD care and to support face-to-face treatment. At present, however, apps are still lagging behind their potential benefits for people with PTSD: both people affected by PTSD and mental health providers have great difficulties identifying high-quality apps, and most apps lack scientific evidence of their effectiveness. Global databases, such as digital apothecaries as proposed by Muñoz et al. (Citation2018), could facilitate the accessibility of useful apps and provide information on their quality, security, and safety.

Author contributions

LS, YT, HB, and EMM designed the trial and initiated this study. RP programmed the web crawler. JS and KS coordinated and conducted the MARS ratings. LS supervised all MARS ratings. LS and JS wrote the first draft. All authors revised the manuscript, read, and approved the final report.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carla Grosche for proofreading the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–16.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). London: American Psychiatric Pub.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2019). App evaluation model.

- Andrade, L. H., Alonso, J., Mneimneh, Z., Wells, J. E., Al-Hamzawi, A., Borges, G., … Kessler, R. C. (2014). Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 44(6), 1303–1317.

- Armontrout, J., Torous, J., Fisher, M., Drogin, E., & Gutheil, T. (2016). Mobile mental health: Navigating new rules and regulations for digital tools. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(10), 91.

- Bakker, D., Kazantzis, N., Rickwood, D., & Rickard, N. (2016). Mental health smartphone apps: Review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e7.

- Balas, E. A., & Boren, S. A. (2000). Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In J. H. vanBemmel & A. T. McCray (Eds.), Yearbook of medical informatics (pp. 65–70). Stuttgart: Schattauer.

- Bardus, M., van Beurden, S. B., Smith, J. R., & Abraham, C. (2016). A review and content analysis of engagement, functionality, aesthetics, information quality, and change techniques in the most popular commercial apps for weight management. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 13(1), 1–9.

- Baumel, A., Faber, K., Mathur, N., Kane, J. M., & Muench, F. (2017). Enlight: A comprehensive quality and therapeutic potential evaluation tool for mobile and web-based eHealth interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(3), e82.

- Beck, J. G., & Sloan, D. M. (2012). The Oxford handbook of traumatic stress disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Berliner, L., Bisson, J., Cloitre, M., Forbes, D., Goldbeck, L., Jensen, T., … Shapiro, F. (2019). ISTSS PTSD prevention and treatment guidelines methodology and recommendations. Retrieved from www.istss.org/treating-trauma/new-istss-prevention-and-treatment-guidelines

- Bisson, J., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Cooper, R., & Lewis, C. (2013). Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (12), CD003388. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003388.pub4

- Blevins, C. A., Weathers, F. W., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Domino, J. L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498.

- Boulos, M. N. K., Brewer, A. C., Karimkhani, C., Buller, D. B., & Dellavalle, R. P. (2014). Mobile medical and health apps: State of the art, concerns, regulatory control and certification. Online Journal of Public Health Informatics, 5(3), 1–23.

- Brief, D. J., Rubin, A., Keane, T. M., Enggasser, J. L., Roy, M., Helmuth, E., … Rosenbloom, D. (2013). Web intervention for OEF/OIF veterans with problem drinking and PTSD symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 890–900.

- Bromet, E. J., Karam, E. G., Koenen, K. C., & Stein, D. J. (2018). The global epidemiology of trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder. In Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: Global perspectives from the WHO world mental health surveys (pp. 1–12). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781107445130.002

- Brown, C. H., Kellam, S. G., Kaupert, S., Muthén, B. O., Wang, W., Muthén, L. K., … McManus, J. W. (2012). Partnerships for the design, conduct, and analysis of effectiveness, and implementation research: Experiences of the prevention science and methodology group. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 39(4), 301–316.

- Byambasuren, O., Sanders, S., Beller, E., & Glasziou, P. (2018). Prescribable mHealth apps identified from an overview of systematic reviews. Npj Digital Medicine, 1(1), 12.

- Charney, M. E., Hellberg, S. N., Bui, E., & Simon, N. M. (2018). Evidenced-based treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: An updated review of validated psychotherapeutic and pharmacological approaches. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 26(3), 99–115.

- Chavez, S., Fedele, D., Guo, Y., Bernier, A., Smith, M., Warnick, J., & Modave, F. (2017). Mobile apps for the management of diabetes. Diabetes Care, 40(10), e145–e146.

- Cuijpers, P., & Schuurmans, J. (2007). Self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: An overview. Current Psychiatry Reports, 9(4), 284–290.

- Donker, T., Petrie, K., Proudfoot, J., Clarke, J., Birch, M. R., & Christensen, H. (2013). Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(11), e247.

- Ebert, D. D., Van Daele, T., Nordgreen, T., Karekla, M., Compare, A., Zarbo, C., … Baumeister, H. (2018). Internet- and mobile-mased psychological interventions: Applications, efficacy, and potential for improving mental health. European Psychologist, 23(2), 167–187.

- Fleiss, J. L. (1999). The design and analysis of clinical experiments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Glasgow, R. E., Lichtenstein, E., & Marcus, A. C. (2003). Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1261–1267.

- Huckvale, K., Torous, J., & Larsen, M. E. (2019). Assessment of the data sharing and privacy practices of smartphone apps for depression and smoking cessation. JAMA Network Open, 2(4), e192542.

- Hussain, M., Al-Haiqi, A., Zaidan, A. A., Zaidan, B. B., Kiah, M. L. M., Anuar, N. B., & Abdulnabi, M. (2015). The landscape of research on smartphone medical apps: Coherent taxonomy, motivations, open challenges and recommendations. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 122(3), 393–408.

- Kantor, V., Knefel, M., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2017). Perceived barriers and facilitators of mental health service utilization in adult trauma survivors: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 52, 52–68.

- Kazlauskas, E., Javakhishvilli, J., Meewisse, M., Merecz-Kot, D., Şar, V., Schäfer, I., … Gersons, B. P. R. (2016). Trauma treatment across Europe: Where do we stand now from a perspective of seven countries. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 29450.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., … Koenen, K. C. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Chatterji, S., Lee, S., Ormel, J., … Wang, P. S. (2009). The global burden of mental disorders: An update from the WHO world Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Epidemiologia E Psichiatria Sociale, 18(1), 23–33.

- Kizilhan, J. I., & Noll-Hussong, M. (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder among former Islamic State child soldiers in northern Iraq. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(1), 425–429.

- Koenen, K. C., Ratanatharathorn, A., Ng, L., McLaughlin, K. A., Bromet, E. J., Stein, D. J., … Kessler, R. C. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder in the world mental health surveys. Psychological Medicine, 47(13), 2260–2274.

- Koffel, E., Kuhn, E., Petsoulis, N., Erbes, C. R., Anders, S., Hoffman, J. E., … Polusny, M. A. (2018). A randomized controlled pilot study of CBT-I coach: Feasibility, acceptability, and potential impact of a mobile phone application for patients in cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. Health Informatics Journal, 24(1), 3–13.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

- Kuhn, E., Crowley, J. J., Hoffman, J. E., Eftekhari, A., Ramsey, K. M., Owen, J. E., … Ruzek, J. I. (2015). Clinician characteristics and perceptions related to use of the PE (prolonged exposure) coach mobile app. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 46(6), 437–443.

- Kuhn, E., Kanuri, N., Hoffman, J. E., Garvert, D. W., Ruzek, J. I., & Taylor, C. B. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of a smartphone app for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 85(3), 267–273.

- Kuhn, E., van der Meer, C., Owen, J. E., Hoffman, J. E., Cash, R., Carrese, P., … Iversen, T. (2018). PTSD Coach around the world. mHealth, 4(2), 15–15. doi:10.21037/mhealth.2018.05.01

- Larsen, M. E., Nicholas, J., & Christensen, H. (2016). Quantifying app store dynamics: Longitudinal tracking of mental health apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(3), e96.

- Luxton, D. D., McCann, R. A., Bush, N. E., Mishkind, M. C., & Reger, G. M. (2011). mHealth for mental health: Integrating smartphone technology in behavioral healthcare. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42(6), 505–512.

- Mani, M., Kavanagh, D. J., Hides, L., & Stoyanov, S. R. (2015). Review and evaluation of mindfulness-based iPhone apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(3), 1–10.

- Messner, E.-M., Terhorst, Y., Barke, A., Baumeister, H., Stoyanov, S., Hides, L., … Probst, T. (2019). Development and validation of the German version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (MARS-G). JMIR mHealth and uHealth. doi:10.2196/14479

- Miller, M. W., & Sadeh, N. (2014). Traumatic stress, oxidative stress and post-traumatic stress disorder: Neurodegeneration and the accelerated-aging hypothesis. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(11), 1156–1162.

- Miner, A., Kuhn, E., Hoffman, J. E., Owen, J. E., Ruzek, J. I., & Taylor, C. B. (2016). Feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of the PTSD coach app: A pilot randomized controlled trial with community trauma survivors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 8(3), 384–392.

- Mohr, D. C., Cheung, K., Schueller, S. M., Brown, C. H., & Duan, N. (2013). Continuous evaluation of evolving behavioral intervention technologies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(4), 517–523.

- Mueser, K. T., Gottlieb, J. D., Xie, H., Lu, W., Yanos, P. T., Rosenberg, S. D., … McHugo, G. J. (2015). Evaluation of cognitive restructuring for post-traumatic stress disorder in people with severe mental illness. British Journal of Psychiatry, 206(6), 501–508.

- Muñoz, R. F., Chavira, D. A., Himle, J. A., Koerner, K., Muroff, J., Reynolds, J., … Schueller, S. M. (2018). Digital apothecaries: A vision for making health care interventions accessible worldwide. mHealth, 4, 1–13.

- NHS (Northumberland, Tyne and Wear). (2016). Post traumatic stress. An NHS self help guide. Retrieved from https://web.ntw.nhs.uk/selfhelp/leaflets/Post%20traumatic%20Stress%20A4%202016%20FINAL.pdf

- NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence). (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

- O’Loughlin, K., Neary, M., Adkins, E. C., & Schueller, S. M. (2019). Reviewing the data security and privacy policies of mobile apps for depression. Internet Interventions, 15, 110–115.

- Olff, M. (2015). Mobile mental health: A challenging research agenda. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(s4), 27882.

- Owen, J. E., Jaworski, B. K., Kuhn, E., Hoffman, J. E., Schievelbein, L., Chang, A., … Rosen, C. (2017). Development of a mobile app for family members of Veterans with PTSD: Identifying needs and modifiable factors associated with burden, depression, and anxiety. Journal of Family Studies, 1–22. doi:10.1080/13229400.2017.1377629

- Owen, J. E., Jaworski, B. K., Kuhn, E., Makin-Byrd, K. N., Ramsey, K. M., & Hoffman, J. E. (2015). mHealth in the wild: Using novel data to examine the reach, use, and impact of PTSD coach. JMIR Ment Health, 2(1), e7.

- Possemato, K., Kuhn, E., Johnson, E., Hoffman, J. E., Owen, J. E., Kanuri, N., … Brooks, E. (2016). Using PTSD coach in primary care with and without clinician support: A pilot randomized controlled trial. General Hospital Psychiatry, 38, 94–98.

- Price, M., Yuen, E. K., Goetter, E. M., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Ancierno, R., & Ruggiero, K. J. (2014). mHealth: A mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(5), 427–436.

- Reger, G. M., Skopp, N. A., Edwards-Stewart, A., & Lemus, E. L. (2015). Comparison of prolonged exposure (PE) coach to treatment as usual: A case series with two active duty soldiers. Military Psychology, 27(5), 287–296.

- Santo, K., Richtering, S. S., Chalmers, J., Thiagalingam, A., Chow, C. K., & Redfern, J. (2016). Mobile phone apps to improve medication adherence: A systematic stepwise process to identify high-quality apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 4(4), e132.

- Sareen, J. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: Impact, comorbidity, risk factors, and treatment. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 59(9), 460–467.

- Schellong, J., Lorenz, P., & Weidner, K. (2019). Proposing a standardized, step-by-step model for creating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related mobile mental health apps in a framework based on technical and medical norms. Eur J Psychotraumatol, 10(1), 1611090.

- Schnyder, U., Ehlers, A., Elbert, T., Foa, E. B., Gersons, B. P. R., Resick, P. A., … Cloitre, M. (2015). Psychotherapies for PTSD: What do they have in common? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 28186.

- Sijbrandij, M., Acarturk, C., Bird, M., Bryant, R. A., Burchert, S., Carswell, K., … Cuijpers, P. (2017). Strengthening mental health care systems for Syrian refugees in Europe and the Middle East: Integrating scalable psychological interventions in eight countries. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup2), 1388102.

- Stoyanov, S. R., Hides, L., Kavanagh, D. J., Zelenko, O., Tjondronegoro, D., & Mani, M. (2015). Mobile app rating scale: A new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 3(1), e27.

- Sucala, M., Cuijpers, P., Muench, F., Cardoș, R., Soflau, R., Dobrean, A., … David, D. (2017). Anxiety: There is an app for that. A systematic review of anxiety apps. Depression and Anxiety, 34(6), 518–525.

- Terhorst, Y., Rathner, E. M., Baumeister, H., & Sander, L. (2018). “Help from the app Store?”: A systematic review of depression apps in German app stores. Verhaltenstherapie, 28(2), 101–112.

- Torous, J., Andersson, G., Bertagnoli, A., Christensen, H., Cuijpers, P., Firth, J., … Arean, P. A. (2019). Towards a consensus around standards for smartphone apps and digital mental health. World Psychiatry, 18(1), 97–98.

- Walker, E. A., Katon, W., Russo, J., Ciechanowski, P., Newman, E., & Wagner, A. W. (2003). Health care costs associated with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in women. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(4), 369–374.

- Watkins, L. E., Sprang, K. R., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2018). Treating PTSD: A review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 1–9.

- Wickersham, A., Petrides, P. M., Williamson, V., & Leightley, D. (2019). Efficacy of mobile application interventions for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: A systematic review. Digital Health, 5, 1–11.

- Xue, C., Ge, Y., Tang, B., Liu, Y., Kang, P., Wang, M., & Zhang, L. (2015). A meta-analysis of risk factors for combat-related PTSD among military personnel and veterans. PLoS One, 10(3), 1–21.

- Zammit, S., Lewis, C., Dawson, S., Colley, H., McCann, H., Piekarski, A., … Bisson, J. (2018). Undetected post-traumatic stress disorder in secondary-care mental health services: Systematic review. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(1), 11–18.