ABSTRACT

Background: Despite the established efficacy of psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) there has been little systematic exploration of dropout rates.

Objective: To ascertain rates of dropout across different modalities of psychological therapy for PTSD and to explore potential sources of heterogeneity.

Method: A systematic review of dropout rates from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of psychological therapies was conducted. The pooled rate of dropout from psychological therapies was estimated and reasons for heterogeneity explored using meta-regression.

Results:: The pooled rate of dropout from RCTs of psychological therapies for PTSD was 16% (95% CI 14–18%). There was evidence of substantial heterogeneity across studies. We found evidence that psychological therapies with a trauma-focus were significantly associated with greater dropout. There was no evidence of greater dropout from therapies delivered in a group format; from studies that recruited participants from clinical services rather than via advertisements; that included only military personnel/veterans; that were limited to participants traumatized by sexual traumas; that included a higher proportion of female participants; or from studies with a lower proportion of participants who were university educated.

Conclusions: Dropout rates from recommended psychological therapies for PTSD are high and this appears to be particularly true of interventions with a trauma focus. There is a need to further explore the reasons for dropout and to look at ways of increasing treatment retention.

Antecedentes: A pesar de la eficacia establecida de las terapias psicológicas para el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), la exploración sistemática de las tasas de abandono se ha estudiado poco.

Objetivo: Determinar las tasas de abandono a lo largo de las diferentes modalidades de terapia psicológica para el TEPT y explorar las fuentes potenciales de heterogeneidad.

Método: Se llevó a cabo una revisión sistemática de las tasas de abandono de ensayos controlados aleatorios (RCTs en su sigla en inglés) de terapias psicológicas. La tasa combinada de abandono de las terapias psicológicas fue estimada y las razones para la heterogeneidad fueron exploradas usando meta-regresión.

Resultados: La tasa combinada de abandono en RCTs de terapias psicológicas fue 16% (95% IC 14%–18%). Hubo evidencia de una heterogeneidad importante a lo largo de los estudios. Se encontró evidencia de que las terapias psicológicas con un foco en el trauma se asociaron con el mayor abandono. No hubo evidencia de mayor abandono en las terapias implementadas en un formato grupal; en los estudios que reclutaron participantes desde servicios clínicos en vez de vía anuncios; que incluyeron solo personal militar/veteranos; que se limitaron a participantes traumatizados por traumas sexuales; que incluyeron una proporción más alta de participantes mujeres; o en estudios con una proporción más baja de participantes que tenían estudios universitarios.

Conclusiones: Las tasas de abandono de las terapias psicológicas recomendadas para el TEPT son altas y pareciera ser particularmente aplicable a las intervenciones con un foco en el trauma. Existe una necesidad de explorar en más detalle las razones para el abandono y buscar formas de aumentar la retención en el tratamiento.

背景 : 尽管心理治疗对创伤后应激障碍 (PTSD) 具有确定的功效, 但鲜研究有对其退出率进行系统性探究。

目标 : 确定创伤后应激障碍的不同心理治疗方法的退出率, 并探究异质性的潜在来源。

方法 : 系统地回顾了对来自随机对照试验 (RCT) 的心理疗法退出率。估计了心理治疗的合并退出率, 并使用元回归分析了异质性的原因。

结果 : RCT的PTSD心理疗法合并退出率为16% (95%CI置信区间为14%-18%) 。证据表明各研究间存在很大的异质性。我们发现的证据表明, 聚焦创伤的心理治疗法与高退出率显著相关。没有证据表明以下治疗或研究有更多的退出者:以团体形式进行的治疗;参与者来自临床服务而非通过广告招募的研究;仅包括军事人员/退伍军人的研究;参与者仅限于性创伤遭遇者的研究;参与者中女性比例更高的研究;或参与者中受过大学教育比例较低的研究。

结论 : PTSD推荐心理治疗的退出率很高, 尤其是聚焦创伤的干预措施。有必要进一步探究中途退出的原因, 并探寻提高治疗维持率的方法。

1. Introduction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating psychiatric disorder with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 8% (Kessler, Citation2000). In addition to the requirement of exposure to a major traumatic event, the diagnostic criteria for PTSD specify the presence of symptoms including re-experiencing the traumatic event; avoiding reminders of the trauma; alterations in arousal and reactivity; and changes in cognition and mood (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

Despite decades of research converging on support for the efficacy of psychological therapy for PTSD (Bisson, Roberts, Andrew, Cooper, & Lewis, Citation2013; Bradley, Greene, Russ, Dutra, & Westen, Citation2005; Jonas et al., Citation2013), we know remarkably little regarding dropout from these interventions (Foa et al., Citation2005; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, Citation2002; Schnurr et al., Citation2007; Schottenbauer, Glass, Arnkoff, Tendick, & Gray, Citation2008). Many psychological therapies have been applied to the treatment of PTSD and these have fundamentally different components and proposed active ingredients (Foa, Keane, Friedman, & Cohen, Citation2008; Schnyder et al., Citation2015). It follows that these variations may have some influence on differential rates of dropout. Despite this likelihood, there have been few attempts to systematically determine dropout rates from the psychological therapies commonly applied to the treatment of PTSD.

Among the evidence-based therapies for PTSD, a major distinction can be drawn between the therapies that focus on the traumatic event and those that aim to reduce traumatic stress symptoms without directly targeting the trauma memory or related thoughts, with the strongest evidence for the effect of those with a trauma-focus (Bisson et al., Citation2013; Bradley et al., Citation2005; Jonas et al., Citation2013). Trauma-focused Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) are currently recommended as first-line interventions for PTSD (American Psychological Association, Citation2017; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), Citation2018; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Citation2018). These trauma-focused psychological therapies rely on confrontation of traumatic images, which can be difficult to tolerate and may result in the potential for greater dropout (Pitman et al., Citation1991; Tarrier et al., Citation1999a). Psychological therapies omitting a role for trauma-focused work may be more tolerable, potentially leading to better retention. However, there is evidence that the absence of a trauma-focus results in poorer outcomes (Bisson et al., Citation2013; Bradley et al., Citation2005; Jonas et al., Citation2013).

The issue of treatment tolerability and symptom exacerbation resulting from trauma-focused psychological therapies has been one of contention in the literature (Devilly & Foa, Citation2001; Hembree et al., Citation2003; Tarrier et al., Citation1999a). It is uncertain whether dropout rates vary as a function of treatment modality or whether those with a trauma-focus are associated with poorer retention. To date, a small number of meta-analyses have compared drop-out rates across different modalities of psychological therapy for PTSD (Bradley et al., Citation2005; Goetter et al., Citation2015; Hembree et al., Citation2003, Imel, Laska, Jakupcak, & Simpson, Citation2013). One of these studies reported no differences between therapies with and without exposure-work, however, the review is now dated and includes a far smaller number of studies than currently available (Hembree et al., Citation2003). Another review reported a trend towards greater dropout from exposure-based treatment, but did not analyse this statistically (Bradley et al., Citation2005). A more recent review reported that dropout was not associated with trauma-focus; however, studies comparing trauma-focused CBT to waitlist or usual care control groups were excluded, restricting the review to 42 studies (Imel et al., Citation2013). A more recent review found no difference in dropout rates from therapies that included exposure work in comparison to those that did not, but the review only included twenty studies of US military veterans (Goetter et al., Citation2015).

The aim of the current review was to ascertain rates of dropout across different modalities of psychological therapy and to determine whether some psychological therapies (especially those with a trauma-focus) were associated with higher rates of dropout than others. Since there is no agreed definition of dropout, we took the number of participants that had left the study at the point of post-treatment assessment as a proxy-indicator of dropout in order to allow the inclusion of data from a maximal number of studies. We also aimed to explore potential sources of heterogeneity among the included studies. Our overarching goal was to contribute to a refined understanding of dropout from psychological therapies for PTSD that will inform the development of treatment protocols that maximize retention.

2. Method

2.1. Selection criteria

Data on drop-out were extracted from studies that had been identified for a review of the efficacy of psychological therapies for adults with PTSD, which was undertaken as part of an update of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) Treatment Guidelines (International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), Citation2018). Both reviews had the same inclusion criteria. RCTs of any defined psychological therapy aimed at the reduction of PTSD-symptoms in comparison with a control group (e.g. usual care/waiting list); other psychological therapy; or psychosocial intervention (e.g. psychoeducation/relaxation training) were included. At least 70% of study participants were required to be diagnosed with PTSD with a duration of three months or more, according to DSM or ICD criteria determined by clinician diagnosis or an established diagnostic interview. This review considered studies of adults aged 18 or over, only. There were no restrictions based on symptom-severity or trauma-type. The diagnosis of PTSD was required to be primary and studies of comorbid PTSD and substance use disorder were excluded, but there were no other restrictions based on co-morbidity. Studies were only included if they reported data on the number of participants that had dropped out of the study by the point of post-treatment assessment. If multiple studies reported data on the same participants, dropout data were only included once. We also excluded RCTs of single-session interventions.

2.2. Search strategy

A search was conducted by the Cochrane Collaboration, which updated a previously published Cochrane review with the same inclusion criteria, which was published in 2013 (Bisson et al., Citation2013). The updated search aimed to identify all RCTs related to the prevention and treatment of PTSD, published from January 2008 to the 31 May 2018, using the search terms PTSD or posttrauma* or post-trauma* or ‘post trauma*’ or ‘combat disorder*’ or ‘stress disorder*’. The searches included results from PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase and the Cochrane database of randomized trials. This produced a group of papers related to the psychological treatment of PTSD in adults. We checked reference lists of the included studies. We searched the World Health Organization’s, and the US National Institutes of Health’s trials portals to identify additional unpublished or ongoing studies. We contacted experts in the field with the aim of identifying unpublished studies and studies that were in submission. A complementary search of the Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) was also conducted.

2.3. Data extraction

Study characteristics and dropout data were extracted by two reviewers independently and in duplicate, using a form that had been pre-piloted. Since there is no agreed definition of dropout, taking the number of participants that had left the study at the point of post-treatment assessment allowed the inclusion of data from a maximal number of studies. Study authors were contacted to obtain missing data. Therapy classifications were agreed with the ISTSS treatment guidelines committee and posted on the ISTSS website to allow comment from the membership. Reasons for dropout and adverse events were not universally available or consistently reported by studies and it was not therefore possible to extract or meta-analyse these data.

2.4. Risk of bias assessment

All included studies were assessed for risk of bias at the study level, using Cochrane criteria (Higgins et al., Citation2011). This included: (1) sequence allocation for randomization (the methods used for randomly assigning participants to the treatment arms and the extent to which this was truly random); (2) allocation concealment (whether or not participants or personnel were able to foresee allocation to a specific group); (3) assessor blinding (whether the assessor was aware of group allocation); (4) incomplete outcome data (whether missing outcome data were handled appropriately); (5) selective outcome reporting (whether reported outcomes matched with those that were pre-specified); and (6) any other notable threats to validity (for example, premature termination of the study). Two researchers independently assessed each study and any conflicts were discussed with a third researcher with the aim of reaching a unanimous decision.

2.5. Data synthesis

Meta-analyses of proportion were conducted using the metaprop command in STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, Citation2013). The metaprop command pools proportions and uses the score statistic and the exact binomial method to compute 95% confidence intervals (Thompson & Higgins, Citation2002). Data were pooled across all active psychological therapies. Sub-group analyses were also conducted to determine the dropout rate for each psychological therapy. A random effects model was chosen due to the heterogeneity across studies in terms of the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the studies; the populations from which the samples were drawn; the nature and duration of therapy; the predominant trauma type; and the mean age of participants.

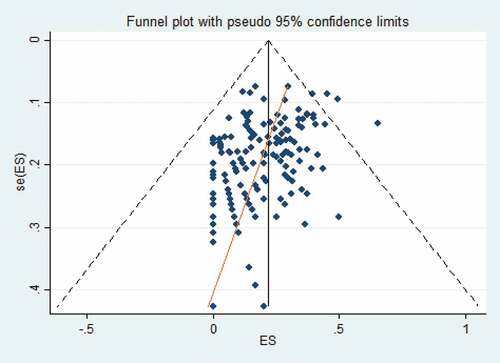

Heterogeneity was assessed using both the I2 statistic (which indicates the proportion of the variance that is due to heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, Citation2011)) and visual inspection of the forest plots. To explore potential sources of heterogeneity, meta-regression was performed using the metareg function of STATA version 13.1 (StataCorp, Citation2013). Meta-regression assesses the association between study-level variables and the effect size (Thompson & Higgins, Citation2002). It was hypothesized that a number of study-level variables would result in higher rates of drop-out, these being: therapies having a trauma-focus (due to the possibility of these therapies being difficult for some participants to tolerate); therapies being delivered in a group-format (since drop out from group therapies has been found to be greater than from therapies delivered on an individual basis (Imel et al., Citation2013)); recruitment from clinical services rather than through advertisements (due to the likelihood of more severe symptoms and a possible tendency for these participants to be less motivated to engage in treatment); whether or not the participants were selected from military/veteran populations (due a greater likelihood of complex or severe PTSD); whether the trauma experienced by participants was sexual (due to the possibility of therapy being more difficult to tolerate); and the percentage of participants who were University educated (due to the possibility that more educated participants are better able to grasp the concepts involved in therapy). To explore the possibility of publication bias, we constructed a funnel plot using data on dropout from all active therapy groups.

3. Results

The original Cochrane review included 70 RCTs. The update search identified 5500 potentially eligible studies published since 2008. Abstracts were reviewed and full-text copies obtained for 203 potentially relevant studies. Forty-four new RCTs met inclusion criteria for the review and reported data on dropout at the point of post-treatment assessment. This resulted in a total of 115 RCTs of 7724 participants. presents a flow diagram for study selection.

3.1. Study characteristics

Study characteristics are summarized in . Twenty-eight defined psychological therapies were evaluated. Eight of these were broadly categorized as CBT with a Trauma Focus (CBT-T) delivered on an individual basis: Brief Eclectic Psychotherapy (BEP); Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT); Cognitive Therapy (CT); Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET); Prolonged Exposure (PE); Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories (RTM); Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRE) and CBT-T (not based on a specific model). Thirteen other therapies delivered to individuals were evaluated: EMDR; CBT without a Trauma Focus; Present Centred Therapy (PCT); Supportive Counselling; Written Exposure Therapy; Observed and Experiential Integration (OEI); Interpersonal Psychotherapy; Psychodynamic Psychotherapy; REM Desensitization; Emotional Freedom Technique (EFT); Dialogical Exposure Therapy (DET); Internet-based CBT; and Relaxation Training. There were six different types of group therapy: Group CBT-T; Group Present Centred Therapy (PCT); Group and Individual CBT-T; Group Stabilizing Treatment; Group Interpersonal Therapy; Group Supportive Counselling. There were also RCTs of couples CBT-T. There were six types of control group: psychoeducation; couples psychoeducation; internet-based psychoeducation; waitlist; treatment as usual; and minimal attention/symptom monitoring.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies

The number of randomized participants ranged from 10 to 360. Studies were conducted in Australia (9), Canada (2), China (2), Denmark (1), Germany (5), Iran (2), Israel (1), Italy (2), Japan (1), the Netherlands (5), Norway (1), Portugal (1), Romania (1), Rwanda (1), Spain (1), Sweden (3), Switzerland (1), Thailand (1), Turkey/Syria (1), Uganda (2), UK (10) and USA (62). Participants were traumatized by military trauma (27 studies), sexual assault or rape (11 studies), war/persecution (4 studies), road traffic accidents (6 studies), earthquakes (2 studies), childhood abuse (3 studies), political detainment (1 study), terrorism (2 studies), physical assault (2 studies), domestic abuse (4 studies), medical diagnoses/emergencies (4 studies), genocide (1 study) and organized violence (3 studies). The remainder included individuals traumatized by various different traumatic events. There were 27 studies of females only and 10 of only males; the percentage of females in the remaining studies ranged from 1.75% to 96%. The percentage with a University education ranged from 4% to 90%.

3.2. Risk of bias

Risk of bias assessments for the included studies are summarized in . Fifty-two studies reported a method of sequence allocation judged to pose a ‘low’ risk of bias; five reported a method with a ‘high’ risk of bias; the remainder reported insufficient details and were, therefore, rated as ‘unclear’. Forty-one studies reported methods of allocation concealment representing a ‘low’ risk of bias; two a method with a ‘high’ risk of bias; with the remainder rated as ‘unclear’. The outcome assessor was aware of the participant’s allocation in 11 of the included studies; it was unclear whether the outcome assessor was aware of group allocation in 20 studies; with the remainder using blind-raters or self-report questionnaires delivered in a way that could not be influenced by members of the research team. Twenty-three studies were judged as posing a ‘high’ risk of bias in terms of incomplete outcome data; 79 studies were felt to have dealt with dropouts appropriately (‘low’ risk of bias); it was unclear in the remaining studies. The majority of studies failed to reference a published protocol, resulting in an ‘unclear’ risk of selective reporting for 75 studies; risk of bias was judged as ‘high’ in five studies and low in the remainder. Seventy of the included studies presented a ‘high’ risk of bias in other areas, for example, in relation to sample size, baseline imbalances between groups, or other methodological shortfalls. We could not rule out potential researcher allegiance, since treatment originators were involved in the evaluation of their own intervention in many of the included studies.

Table 2. Risk of bias assessments of the included studies

3.3. Dropout

Across the different modalities of psychological therapy, dropout rates from individual studies ranged from 0%-65%. The pooled dropout rate from psychological therapies for PTSD was 16% (95% CI 14–18; k = 116) with substantial heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 77.3%). The dropout rate for each modality of psychological therapy is presented in . The heterogeneity in dropout rates indicates differences that may be predicted by the variables entered into meta-regression.

Table 3. Results of the meta-analyses of dropout

Table 4. Meta-regression of study-level variables on dropout from all active psychological therapies

3.4. Meta-regression

Results of the meta-regressions are presented in . We found evidence that psychological therapies with a trauma-focus were significantly associated with greater dropout (β = 0.069; CI 0.011–0.127; P = 0.021; dropout rate of 18% (95% CI 15–21%) from those with a trauma focus versus 14% (95% CI 10–18%) from those without a trauma focus). There was no evidence of greater dropout from therapies delivered in a group format; from studies that recruited participants from clinical services rather than via advertisements; that included only military personnel/veterans; that included only participants traumatized by sexual traumas; from studies with a higher proportion of female participants; or from studies with a lower proportion of participants who were University educated.

3.5. Publication bias

A funnel plot (see ), which was constructed using data on dropout from all active therapy groups, did not show evidence of publication bias.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

Taking the number of participants that had left the study at the point of post-treatment assessment as a proxy-indicator of dropout, the pooled rate from psychological therapies for PTSD was 16% (95% CI 14–18%). This is of a similar magnitude to a previous meta-analysis of 42 studies, which found an average dropout rate of 18% (Imel et al., Citation2013) using the definition of dropout given by the included studies. This is also similar to the dropout rate of 17.5% obtained from a meta-analysis of dropout from RCTs of psychotherapy for depression (Cooper & Conklin, Citation2015) that defined dropout as unexpected attrition among individuals who were randomized to a treatment but failed to complete it. It was considerably lower than the pooled drop-out rate of 36% found by a more recent review of twenty studies of US military veterans (Goetter et al., Citation2015). This was in comparison to a pooled dropout rate from studies of veterans/military personnel in this review of 18% (95% CI 15–22%). This is likely to reflect the fact that the previous review included a variety of different study designs including naturalistic studies and used the definition of dropout given by the authors of individual studies.

There was no evidence of greater dropout from therapies delivered in a group format. This contradicts the findings of earlier reviews that found group delivery to be associated with a significant increase in dropout (Goetter et al., Citation2015; Imel et al., Citation2013). This may be the result of more recent studies evaluating interventions that have been optimized to increase retention or more proactive attempts to retain participants. There was also no evidence of significantly greater dropout from studies that recruited participants from clinical services rather than via advertisements; that included only military personnel/veterans; that included only participants traumatized by sexual traumas; that included only female participants; and from studies with a lower proportion of participants who were University educated. Research looking at factors associated with dropout have yielded inconsistent findings (Bryant et al., Citation2007; Schottenbauer et al., Citation2008; Taylor, Citation2003). Although the findings of the current review contradict some previous studies; they are in agreement with others. Inconsistencies may be the result of difference in study type and design; the types of interventions of interest and the degree to which they are protocolized; or may vary according to the populations of interest.

We found evidence that psychological therapies with a trauma-focus were significantly associated with greater dropout. This challenges the findings of previous, far smaller, meta-analyses, which found no significant differences in dropout rates from therapies with and without a trauma-focus (Goetter et al., Citation2015; Hembree et al., Citation2003). However, one of these studies found a significant difference between PCT (a non-trauma-focused intervention) and a group of therapies that had a trauma-focus (Imel et al., Citation2013). Our findings may be a result of the accumulated data available from a larger number of studies. The results, however, are consistent with the findings of a review of seven studies of treatments specifically targeting child abuse-related or complex PTSD, which found some evidence of greater drop-out from exposure-based therapies (Dorrepaal et al., Citation2014). Although there are many reasons for dropout from psychological therapies, this finding suggests that difficulties tolerating trauma-focused treatment may be one of these. Adverse events such as the prolonged exacerbation of existing symptoms (for example, an increased frequency of unwanted thoughts or nightmares) or the occurrence of new symptoms (for example, anger or self-blame) may lead to dropout, yet there is a surprising scarcity of research exploring the issue (Berk & Parker, Citation2009). Psychological therapy is traditionally perceived as safe, presenting a low risk of unwanted effects (Nutt & Sharpe, Citation2008). In reality, the estimated rate of reported side effects is between 3% and 15%, which is of a similar magnitude to that reported for pharmacotherapy (Linden, Citation2012). However, it is often difficult to draw a distinction between adverse events and time-limited negative experiences inherent to the process of some psychological therapies. This includes the experience of distress provocation, which is inevitable in the process of trauma-focused work.

A survey of psychologists’ attitudes to trauma-focused intervention found that concerns about tolerability and dropout were among the main reasons that psychologists did not use trauma-focused intervention, despite the compelling evidence supporting its use (Becker, Zayfert, & Anderson, Citation2004). However, only a small number of studies have acknowledged or explored adverse events such as symptom worsening or its influence on dropout in relation to trauma-focused therapy. This is surprising, given that symptom exacerbation has long since been documented in the treatment of PTSD (Pitman et al., Citation1991; Tarrier et al., Citation1999b). It also limits our ability to judge how well various therapies were tolerated by PTSD sufferers. An RCT of imagery rehearsal therapy for trauma-related nightmares found that all four participants who actively withdrew from the treatment group had experienced increased negative imagery effects, suggesting a direct relationship between an inability to tolerate the treatment and subsequent dropout (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Tarrier, Sommerfield, Pilgrim, & Humphreys, Citation1999). Conversely, a study of 76 individuals found that only 9–21% of participants showed reliable symptom exacerbation, and these individuals were no more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely (Foa, Zoellner, Hembree, & Alvarez-Conrad, Citation2002). Similarly, an RCT comparing cognitive therapy (without a trauma focus) to imaginal exposure found that symptom worsening affected 10% of participants, with a significantly greater number of these being in the imaginal exposure group; however, this between-group difference was no longer present at follow-up and rates of dropout were similar from both groups (Tarrier et al., Citation1999).

The studies included in this review usually failed to provide information on adverse events and contained few explanations for dropout, so it is difficult to ascertain the reasons that participants dropped out. It must be acknowledged that symptom improvement is a possible reason for dropout (Szafranski, Smith, Gros, & Resick, Citation2017). It follows that termination of treatment for this reason would be highest from the most effective treatments (i.e. those with a trauma-focus (Bisson et al., Citation2013; Bradley et al., Citation2005; Jonas et al., Citation2013)). This said, recent studies have found that those who attend more treatment sessions generally obtain more favourable outcomes (Holmes et al., Citation2019; Rutt, Oehlert, Krieshok, & Lichtenberg, Citation2018). More transparent reporting of dropout is required to explore this further. Whatever the cause, dropout is a major health and societal concern, which may result in individuals failing to receive optimal treatment (Craske et al., Citation2006).

4.2. Strengths and limitations

The review followed Cochrane guidelines for the identification of relevant studies; data extraction; and risk assessment (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). A wide range of psychological therapies for PTSD were considered, which included participants from different countries and backgrounds, who had been exposed to a variety of different traumatic events. Inevitably, there were some limitations. The majority of studies included in the review excluded individuals with comorbidities of substance dependence, psychosis, and severe depression, who may be more likely to drop out of treatment prematurely, as evidenced by particularly high rates of drop out from studies of participants with co-morbid alcohol dependency (Bothwell, Greene, Podolsky, & Jones, Citation2016; Roberts, Jones, & Bisson, Citation2016; Zandberg et al., Citation2016). All included studies were published, resulting in the possibility of publication bias. However, a funnel plot constructed from the data did not show evidence of this being an issue.

Since there is no agreed conceptualization of dropout, this review extracted and meta-analysed data on the number of participants that had left the study at the point of post-treatment assessment to allow the inclusion of data from a maximal number of studies. There may have been some participants who completed a full course of therapy but failed to attend the post-treatment assessment. Equally, there may have been some participants who failed to complete the course of treatment but attended the post-treatment assessment nonetheless. Although this may bias our findings, there are limitations to all methods that we could have adopted to conceptualize dropout.

The review relied on RCT evidence, which is both a strength and a limitation. The methodology may have excluded some potentially high-quality sources of evidence, such as large observational studies and non-randomized controlled effectiveness studies (Bothwell et al., Citation2016), which could contribute to a more accurate overall assessment of dropout. It may be the case that dropout from clinical trials underestimates the true extent of dropout in routine clinical care on the basis that study teams are motivated to retain participants and often provide incentives for the completion of treatment. Equally, participants may have been more inclined to drop out on the basis of the additional demands of participation in a trial, such as regular completion of research assessments. However, taking a broader approach would risk diluting higher quality sources of evidence with weaker ones. A major weakness was that reasons for dropout were not reported or were poorly reported by most studies and it was not possible to systematically extract and analyse this information.

4.3. Research implications

Bringing together the available evidence on dropout has always been problematic given that there is no agreed definition and studies have conceptualized the phenomenon differently. Agreeing a definition of dropout would advance the field by encouraging the reporting of data that is comparable across trials. A previous study that compared the application of four operational definitions of dropout (therapist judgement, failure to attend the last scheduled appointment, a median-split procedure, and failure to return to therapy after the intake appointment) found that the rate ranged from 17.6% to 53.1%, depending on the definition that was used (Hatchett & Park, Citation2003). It follows that a framework to guide the standardized collection and documentation of data related to dropout including information on adverse events is needed. There is currently no theoretical concept to guide the evaluation and reporting of dropout and adverse events that occur during psychological therapy, which is needed and would include a standardized list of reasons for dropout. A first step would be for research ethics committees to mandate that future RCTs of psychological treatments routinely collect and report standardized data on dropout, including the reasons for it. When possible, studies should also report on the severity of symptoms at the point that participants drop out from therapy and whether any adverse events occurred (Hembree et al., Citation2003). Systematic reviews that analyse individual patient data in relation to dropout enable the application of a standardized definition across studies and would advance the field by moving beyond looking at associations between study-level variables and dropout. As noted by previous reviews, there is also a need for the standardized and consistent measurement of treatment acceptability across trials (Lewis, Roberts, Bethell, Robertson, & Bisson, Citation2018; Simon et al., Citation2019). Only when we have sufficient knowledge on the reasons for dropout can we be sure that patients are receiving the best possible intervention.

4.4. Clinical implications

Although we cannot be sure that the reasons for dropout are negative, the findings point to the need for careful assessment of the suitability of patients for trauma-focused work. Since there is evidence for the effect of many different modalities of psychological therapy (American Psychological Association, Citation2017; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS), Citation2018; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Citation2018), a ‘one-size fits all’ approach should be avoided and the evidence-base used to guide shared-decision making between patient and clinician (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Citation2018, Cloitre, Citation2015). Enhancing patient choice may improve retention on the basis that individuals are self-selecting treatment approaches that hold personal appeal. Whether or not this ultimately impacts retention and treatment outcomes requires investigation. Since PTSD is a highly heterogeneous condition (Cloitre, Citation2015; DiMauro, Carter, Folk, & Kashdan, Citation2014) a greater understanding of dropout has the potential to facilitate the targeted recommendation of existing evidence-based treatments to specific sub-groups of patients. Dropout is clearly a complex phenomenon, which may be best conceptualized as having a multi-faceted aetiology that is likely to vary across different therapies and diagnostic groups. A multi-factorial approach is likely to be required to reduce dropout, such as a stepped care approach that is personalized to include stabilization if necessary and addresses the various barriers to remaining in treatment (Dorrepaal et al., Citation2013; Zatzick, Citation2012). Although there is evidence to suggest that trauma-focused therapies can be safely used with a wide range of people with PTSD, including those who may be considered to have contraindications such as psychiatric comorbidities and histories of sexual abuse (Cloitre, Garvert, & Weiss, Citation2017, van Minnen, Harned, Zoellner, & Mills, Citation2012, Wagenmans, Van Minnen, Sleijpen, & De Jongh, Citation2018), further work is needed to determine any possible impact on dropout. Phased therapies have been developed with preparatory work to improve stability before trauma-focused work (Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, Citation2002a). However, there is no consensus as to whether models starting with stabilization are necessary or preferable to directly applying evidence-based trauma-focused interventions (Lahuis, Scholte, Aarts, & Kleber, Citation2019, Ter Heide, Mooren, & Kleber, Citation2016; Ter Heide, Mooren, Kleijn, de Jongh, & Kleber, Citation2011). This approach has been found to result in improved outcomes and greater retention in trauma-focused CBT for PTSD (Bryant et al., Citation2013). Another option is the introduction of peer support, which has been shown to encourage participants to re-enter treatment and subsequently achieve significant clinical improvement (Hernandez-Tejada, Hamski, & Sánchez-Carracedo, Citation2017).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acarturk, C., Konuk, E., Cetinkaya, M., Senay, I., Sijbrandij, M., Gulen, B., & Cuijpers, P. (2016). The efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among Syrian refugees: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 46(12), 2583–22.

- Adenauer, H., Catani, C., Gola, H., Keil, J., Ruf, M., Schauer, M., & Neuner, F. (2011). Narrative exposure therapy for PTSD increases top-down processing of aversive stimuli – evidence from a randomized controlled treatment trial. BMC Neuroscience, 12(1), 1–13.

- Ahmadi, K., Hazrati, M., Ahmadizadeh, M., & Noohi, S. (2015). REM desensitization as a new therapeutic method for post-traumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Medica Indonesiana, 47(2), 111–119.

- Akbarian, F., Bajoghli, H., Haghighi, M., Kalak, N., Holsboer-Trachsler, E., & Brand, S. (2015). The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy with respect to psychological symptoms and recovering autobiographical memory in patients suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 395–404.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed. 4th ed. Text Revision). Washington, DC: Author.

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in adults. Washington, DC: Author.

- Asukai, N., Saito, A., Tsuruta, N., Kishimoto, J., & Nishikawa, T. (2010). Efficacy of exposure therapy for Japanese patients with posttraumatic stress disorder due to mixed traumatic events: A randomized controlled study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(6), 744–750.

- Beck, J. G., Coffey, S. F., Foy, D. W., Keane, T. M., & Blanchard, E. B. (2009). Group cognitive behavior therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: An initial randomized pilot study. Behavior Therapy, 40, 82–92.

- Becker, C. B., Zayfert, C., & Anderson, E. (2004). A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 277–292. doi:10.1016/S0005-7967(03)00138-4

- Berk, M., & Parker, G. (2009). The elephant on the couch: Side-effects of psychotherapy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(9), 787–794.

- Bichescu, D., Neuner, F., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2007). Narrative exposure therapy for political imprisonment realted chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2212–2220.

- Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Cooper, R., & Lewis, C. (2013). Psychological therapies for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD003388.

- Blanchard, E., Hickling, E. J., Devineni, T., Veazey, C. H., Galovski, T. E., Mundy, E., & Buckley, T. C. (2003). A controlled evaluation of cognitive behaviorial therapy for posttraumatic stress in motor vehicle accident survivors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(1), 79–96.

- Bothwell, L. E., Greene, J. A., Podolsky, S. H., & Jones, D. S. (2016). Assessing the gold standard – Lessons from the history of RCTs. New England Journal of Medical, 374(22), 2175–2181.

- Bradley, R., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L., & Westen, D. (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 214–227.

- Bradshaw, R. A., McDonald, M. J., Grace, R., Detwiler, L., & Austin, K. (2014). A randomized clinical trial of Observed and Experiential Integration (OEI): A simple, innovative intervention for affect regulation in clients with PTSD. Traumatology Traumatology: an International Journal, 20, 161–171.

- Brom, D., Kleber, R., & Defares, P. (1989). Brief psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorders. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 57(5), 607–612.

- Bryant, R., Moulds, M. L., Guthrie, R. M., Dang, S. T., & Nixon, R. D. V. (2003). Imaginal exposure alone and imaginal exposure with cognitive restructuring in treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 706–712.

- Bryant, R. A., Ekasawin, S., Chakrabhand, S., Suwanmitri, S., Duangchun, O., & Chantaluckwong, T. (2011). A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of cognitive behavior therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in terrorist-affected people in Thailand. World Psychiatry, 10(3), 205–209.

- Bryant, R. A., Mastrodomenico, J., Hopwood, S., Kenny, L., Cahill, C., Kandris, E., & Taylor, K. (2013). Augmenting cognitive behaviour therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder with emotion tolerance training: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 43(10), 2153–2160.

- Bryant, R. A., Moulds, M. L., Mastrodomenico, J., Hopwood, S., Felmingham, K., & Nixon, R. D. V. (2007). Who drops out of treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder? Clinical Psychologist, 11(1), 13–15.

- Buhmann, C., Nordentoft, M., Ekstroem, M., Carlsson, J., & Mortensen, E. L. (2016). The effect of flexible cognitive-behavioural therapy and medical treatment, including antidepressants on post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in traumatised refugees: Pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208, 252–259.

- Butollo, W., Karl, R., König, J., & Rosner, R. (2016). A randomized controlled clinical trial of dialogical exposure therapy versus cognitive processing therapy for adult outpatients suffering from PTSD after type I trauma in adulthood. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(1), 16–26.

- Capezzani, L., Ostacoli, L., Cavallo, M., Carletto, S., Fernandez, I., Solomon, R., … Cantelmi, T. (2013). EMDR and CBT for cancer patients: Comparative study of effects on PTSD, anxiety, and depression. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 7, 134–143.

- Carletto, S., Borghi, M., Bertino, G., Oliva, F., Cavallo, M.,Hofmann, A., … Ostacoli, L. (2016). Treating post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with multiple sclerosis: A randomized controlled trial comparing the efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing and relaxation therapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 526.

- Carlson, J., Chemtob, C. M., Rusnak, K., Hedlund, N. L., & Muraoka, M. Y. (1998). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EDMR) treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11(1), 3–32.

- Castillo, D. T., Chee, C. L., Nason, E., Keller, J., C'de Baca, J., Qualls, C., … Keane, T. M. (2016). Group-delivered cognitive/exposure therapy for PTSD in women veterans: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 8(3), p. No-Specified.

- Chard, K. M. (2005). An evaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 965.

- Cloitre, M. (2015). The “One size fits all” approach to trauma treatment: Should we be satisfied? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 27344.

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., & Weiss, B. J. (2017). Depression as a moderator of STAIR narrative therapy for women with post-traumatic stress disorder related to childhood abuse. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1377028.

- Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002a). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067.

- Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002b). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1067–1074.

- Cloitre, M., Stovall-McClough, K. C., Nooner, K., Zorbas, P., Cherry, S., Jackson, C. L., … Petkova, E. (2010). Treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 915–924.

- Cooper, A. A., & Conklin, L. R. (2015). Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 57–65.

- Craske, M. G., Roy-Byrne, P., Stein, M. B., Sullivan, G., Hazlett-Stevens, H., Bystritsky, A., & Sherbourne, C. (2006). CBT intensity and outcome for panic disorder in a primary care setting. Behavior Therapy, 37(2), 112–119.

- Devilly, G., & Foa, E. (2001). Comments on Tarrier et al’s (1999) study and the investigation of exposure and cognitive therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 114–116.

- Devilly, G., Spence, S., & Rapee, R. (1998). Statistical and reliable change with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Treating trauma within a veteran population. Behavior Therapy, 29, 435–455.

- Devilly, G. J., & Spence, S. H. (1999). The relative efficacy and treatment distress of EMDR and a cognitive-behavior trauma treatment protocol in the amelioration of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 13(1–2), 131–157.

- DiMauro, J., Carter, S., Folk, J. B., & Kashdan, T. B. (2014). A historical review of trauma-related diagnoses to reconsider the heterogeneity of PTSD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 774–786.

- Dorrepaal, E., Thomaes, K., Hoogendoorn, A. W., Veltman, D. J., Draijer, N., & van Balkom, A. J. L. M. (2014). Evidence-based treatment for adult women with child abuse-related complex PTSD: A quantitative review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 23613.

- Dorrepaal, E., Thomaes, K., Smit, J. H., van Balkom, A. J. L. M., Veltman, D. J., Hoogendoorn, A. W., & Draijer, N. (2012). Stabilizing group treatment for complex posttraumatic stress disorder related to child abuse based on psychoeducation and cognitive behavioural therapy: A multisite randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 81, 217–225.

- Dorrepaal, E., Thomaes, K., Smit, J. H., Veltman, D. J., Hoogendoorn, A. W., van Balkom, A. J. L. M., & Draijer, N. (2013). Treatment compliance and effectiveness in complex PTSD patients with co-morbid personality disorder undergoing stabilizing cognitive behavioral group treatment: A preliminary study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 21171.

- Duffy, M., Gillespie, K., & Clark, D. (2007). Post-traumatic stress disorder in the context of terrorism and other civil conflict in Northern Ireland: Randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal, 334, 1147–1150.

- Dunne, R. L., Kenardy, J., & Sterling, M. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy for the treatment of PTSD in the context of chronic whiplash. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 28(9), 755–765.

- Echeburua, E., Zubizarreta, I., & Sarasua, B. (1997). Psychological treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in victims of sexual aggression. Behavior Modification, 21, 433–456.

- Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., & Fennell, M. (2005). Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Development and evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43, 413–431.

- Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., Fennell, M., Herbert, C., & Mayou, R. (2003). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, a self-help booklet, and repeated assessments as early interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(10), 1024–1032.

- Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Grey, N., Wild, J., Liness, S., Albert, I., & Clark, D. M. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of 7-day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and emotion-focused supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171, 294–304.

- Falsetti, S., Resnick, H., & Davis, J. (2008). Multiple channel exposure therapy for women with PTSD and comorbid panic attacks. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 37, 117–130.

- Fecteau, G., & Nicki, R. (1999). Cognitive behavioural treatment of post traumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accident. Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapy, 27(3), 201–214.

- Feske, U. (2008). Treating low-income and minority women with posttraumatic stress disorder a pilot study comparing prolonged exposure and treatment as usual conducted by community therapists. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(8), 1027–1040.

- Foa, E., Dancu, C. V., Hembree, E. A., Jaycox, L. H., Meadows, E. A., & Street, G. P. (1999). A comparison of exposure therapy, stress inoculation training, and their combination for reducing posttraumatic stress disorder in female assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 194–200.

- Foa, E., Hembree, E. A., Cahill, S. P., Rauch, S. A. M., Riggs, D. S., Feeny, N. C., & Yadin, E. (2005). Randomized trial of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder with and without cognitive restructuring: Outcome at academic and community clinics. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 953–964.

- Foa, E., McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Rosenfield, D., Yadin, E., Yarvis, J. S., & Peterson, A. L. (2018). Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present-centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: A randomized clinical trial. Jama, 319, 354–364.

- Foa, E., Rothbaum, B. O., Riggs, D. S., & Murdock, T. B. (1991). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(5), 715–723.

- Foa, E. B., Keane, T. M., Friedman, M. J., & Cohen, J. A. (Eds.). (2008). Effective treatments for PTSD: Practice guidelines from the international society for traumatic stress studies. Guilford Press.

- Foa, E. B., Zoellner, L. A., Hembree, E. A., & Alvarez-Conrad, J. (2002). Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4). doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.1022

- Fonzo, G., Goodkind, M. S., Oathes, D. J., Zaiko, Y. V., Harvey, M., Peng, K. K., … Etkin, A. (2017). PTSD psychotherapy outcome predicted by brain activation during emotional reactivity and regulation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 1163–1174.

- Forbes, D., Lloyd, D., Nixon, R. D. V., Elliott, P., Varker, T., Perry, D., … Creamer, M. (2012). A multisite randomized controlled effectiveness trial of cognitive processing therapy for military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(3), 442–452.

- Ford, J. D., Chang, R., Levine, J., & Zhang, W. (2013). Randomized clinical trial comparing affect regulation and supportive group therapies for victimization-related PTSD with incarcerated women. Behavior Therapy, 44(2), 262–276.

- Ford, J. D., Steinberg, K. L., & Zhang, W. (2011). A randomized clinical trial comparing affect regulation and social problem-solving psychotherapies for mothers with victimization-related PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 560–578.

- Galovski, T. E., Blain, L. M., Mott, J. M., Elwood, L., & Houle, T. (2012). Manualized therapy for PTSD: Flexing the structure of cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 968.

- Gamito, P., Oliveira, J., Rosa, P., Morais, D., Duarte, N., Oliveira, S., & Saraiva, T. (2010). PTSD elderly war veterans: A clinical controlled pilot study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 13(1), 43–48.

- Gersons, B. P., Carlier, I. V., Lamberts, R. D., & Van der Kolk, B. A. (2000). Randomized clinical trial of brief eclectic psychotherapy for police officers with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 13(2), 333–347.

- Goetter, E. M., Bui, E., Ojserkis, R. A., Zakarian, R. J., Brendel, R. W., & Simon, N. M. (2015). A systematic review of dropout from psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(5), 401–409.

- Gray, R., Budden-Potts, D., & Bourke, F. (2017). Reconsolidation of traumatic memories for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial of 74 male veterans. Psychotherapy Research, 1–19.

- Hatchett, G. T., & Park, H. L. (2003). Comparison of four operational definitions of premature termination. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 40(3), 226.

- Hembree, E. A., Foa, E. B., Dorfan, N. M., Street, G. P., Kowalski, J., & Tu, X. (2003). Do patients drop out prematurely from exposure therapy for PTSD? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(6), 555–562.

- Hensel-Dittmann, D., Schauer, M., Ruf, M., Catani, C., Odenwald, M., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2011). Treatment of traumatized victims of war and torture: A randomized controlled comparison of narrative exposure therapy and stress inoculation training. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 80(6), 345–352.

- Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., Hamski, S., & Sánchez-Carracedo, D. (2017). Incorporating peer support during in vivo exposure to reverse dropout from prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: Clinical outcomes. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 52(4–6), 366–380.

- Higgins, J., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from www.cochrane-handbook.org

- Higgins, J. P., Altman, D. G., Gotzsche, P. C., Juni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., … Sterne, J. A. C. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343, d5928.

- Hinton, D., Chhean, D., Pich, V., Safren, S. A., Hofmann, S. G., & Pollack, M. H. (2005). A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy for Cambodian refugees with treatment resistant PTSD and panic attacks: A cross over design. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18, 617–629.

- Hinton, D. E., Hofmann, S. G., Rivera, E., Otto, M. W., & Pollack, M. H. (2011). Culturally adapted CBT (CA-CBT) for Latino women with treatment-resistant PTSD: A pilot study comparing CA-CBT to applied muscle relaxation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(4), 275–280.

- Hogberg, G., Pagani, M., Sundin, O., Soares, J., Aberg-Wistedt, A., Tarnell, B., & Hallstrom, T. (2007). On treatment with eye movement desensitization and reprocessing of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder in public transportation workers – a randomized controlled trial. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61(1), 54–60.

- Hollifield, M., Sinclair-Lian, N., Warner, T. D., & Hammerschlag, R. (2007). Acupuncture for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(6), 504–513.

- Holmes, S. C., Johnson, C. M., Suvak, M. K., Sijercic, I., Monson, C. M., & Wiltsey Stirman, S. (2019). Examining patterns of dose response for clients who do and do not complete cognitive processing therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 68, 102120.

- Imel, Z. E., Laska, K., Jakupcak, M., & Simpson, T. L. (2013). Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 394.

- International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). (2018). New ISTSS Prevention and Treatment Guidelines [Online]. Retrieved from http://www.istss.org/treating-trauma/new-istss-guidelines.aspx

- Ironson, G., Freund, B., Strauss, J. L., & Williams, J. (2002). Comparison of two treatments for traumatic stress: A community based study of EMDR and prolonged exposure. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 113–128.

- Ivarsson, D., Blom, M., Hesser, H., Carlbring, P., Enderby, P., Nordberg, R., & Andersson, G. (2014). Guided internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 1, 33–40.

- Jacob, N., Neuner, F., Maedl, A., Schaal, S., & Elbert, T. (2014). Dissemination of psychotherapy for trauma spectrum disorders in postconflict settings: A randomized controlled trial in Rwanda. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83, 354–363.

- Jensen, J. (1994). An investigation of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing as a treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms of Vietnam combat veterans. Behavior Therapy, 25, 311–325.

- Johnson, D., Johnson, N. L., Perez, S. K., Palmieri, P. A., & Zlotnick, C. (2016). Comparison of adding treatment of PTSD during and after shelter stay to standard care in residents of battered women’s shelters: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 29, 365–373.

- Johnson, D. M., Zlotnick, C., & Perez, S. (2011). Cognitive behavioral treatment of PTSD in residents of battered women’s shelters: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 542.

- Jonas, D. E., Cusack, K., Forneris, C. A., Wilkins, T. M., Sonis, J., Middleton, J. C., … Olmsted, K. R. (2013). Psychological and pharmacological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In: Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 92. US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Karatzias, T., Power, K., Brown, K., McGoldrick, T., Begum, M., Young, J., … Adams, S. (2011). A controlled comparison of the effectiveness and efficiency of two psychological therapies for posttraumatic stress disorder: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs. emotional freedom techniques. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199, 372–378.

- Keane, T., Fairbank, J. A., Caddell, J. M., & Zimering, R. T. (1989). Implosive (flooding) therapy reduces symptoms of PTSD in Vietnam combat veterans. Behavior Therapy, 20(2), 245–260.

- Kessler, R. C. (2000). Posttraumatic stress disorder: The burden to the individual and to society. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry., 61(5), 4–14.

- Krakow, B., Hollifield, M., Johnston, L., Koss, M., Schrader, R., Warner, T. D., & Prince, H. (2001). Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 286(5), 537–545.

- Krupnick, J. L., Green, B. L., Stockton, P., Miranda, J., Krause, E., & Mete, M. (2008). Group interpersonal psychotherapy for low-income women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychotherapy Research, 18(5), 497–507.

- Kubany, E., Hill, E., & Owens, J. (2004). Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD (CTT-BW). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 3–18.

- Kubany, E., Hill, E. E., & Owens, J. A. (2003). Cognitive trauma therapy for battered women with PTSD: Preliminary findings. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16, 81–91.

- Lahuis, A. M., Scholte, W. F., Aarts, R., & Kleber, R. J. (2019). Undocumented asylum seekers with posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1605281.

- Laugharne, J., Kullack, C., Lee, C. W., McGuire, T., Brockman, S., Drummond, P. D., & Starkstein, S. (2016). Amygdala volumetric change following psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 28, 312–318.

- Lee, C., Gavriel, H., Drummond, P., Richards, J., & Greenwald, R. (2002). Treatment of PTSD: Stress inoculation training with prolonged exposure compared to EMDR. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58, 1071–1089.

- Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Bethell, A., Robertson, L., & Bisson, J. I. (2018). Internet-based cognitive and behavioural therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, Art. No.: CD011710.

- Lewis, C. E., Farewell, D., Groves, V., Kitchiner, N. J., Roberts, N. P., Vick, T., & Bisson, J. I. (2017). Internet-based guided self-help for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Randomized controlled trial. Depression and Anxiety, 34(6), 555–565.

- Lindauer, R. J., Gersons, B. P., van Meijel, E. P., Blom, K., Carlier, I. V., Vrijlandt, I., & Olff, M. (2005). Effects of brief eclectic psychotherapy in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: Randomized clinical trial. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18(3), 205–212.

- Linden, M. (2012). How to define, find and classify side effects in psychotherapy: From unwanted events to adverse treatment reactions. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Published Online in Wiley Online Library. doi:10.1002/cpp.1765,

- Littleton, H., Grills, A. E., Kline, K. D., Schoemann, A. M., & Dodd, J. C. (2016). The From Survivor to Thriver program: RCT of an online therapist-facilitated program for rape-related PTSD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 41–51.

- Litz, B. T., Engel, C. C., Bryant, R. A., & Papa, A. (2007). A randomized, controlled proof-of-concept trial of an Internet-based, therapist-assisted self-management treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164, 1676–1683.

- Marcus, S., Marquis, P., & Sakai, C. (1997). Controlled study of treatment of PTSD using EMDR in an HMO setting. Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice, 34, 307–315.

- Markowitz, J., Petkova, E., Neria, Y., Van Meter, P. E., Zhao, Y., Hembree, E., & Marshall, R. D. (2015). Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172, 430–440.

- Marks, I., Lovell, K., Noshirvani, H., Livanou, M., & Thrasher, S. (1998). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by exposure and/or cognitive restructuring: A controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55(4), 317–325.

- McDonagh, A., Friedman, M., McHugo, G., Ford, J., Sengupta, A., Mueser, K., … Descamps, M. (2005). Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 515–524.

- McLay, R., Baird, A., Webb-Murphy, J., Deal, W., Tran, L., Anson, H., … Johnston, S. (2017). A randomized, head-to-head study of virtual reality exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20, 218–224.

- McLay, R., Wood, D. P., Webb-Murphy, J. A., Spira, J. L., Wiederhold, M. D., Pyne, J. M., & Wiederhold, B. K. (2011). A randomized, controlled trial of virtual reality-graded exposure therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in active duty service members with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14, 223–229.

- Monson, C., Fredman, S. J., Macdonald, A., Pukay-Martin, N. D., Resick, P. A., & Schnurr, P. P. (2012). Effect of cognitive-behavioral couple therapy for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Jama, 308, 700–709.

- Monson, C., Schnurr, P. P., Resick, P. A., Friedman, M. J., Young-Xu, Y., & Stevens, S. P. (2006). Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 898–907.

- Morath, J., Moreno-Villanueva, M., Hamuni, G., Kolassa, S., Ruf-Leuschner, M., Schauer, M., & Kolassa, I.-T. (2014). Effects of psychotherapy on DNA strand break accumulation originating from traumatic stress. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83, 289–297.

- Mueser, K. T., Rosenburg, S. D., Xie, H., Jankowski, M. K., Bolton, E. E., Lu, W., … Rosenburg, H. J. (2008). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder in severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 259–271.

- Nacasch, N., Foa, E. B., Huppert, J. D., Tzur, D., Fostick, L., Dinstein, Y., … Zohar, J. (2011). Prolonged exposure therapy for combat- and terror-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized control comparison with treatment as usual NCT00229372. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72, 1174–1180.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder (NICE guideline NG116). Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

- Neuner, F., Kurreck, S., Ruf, M., Odenwald, M., Elbert, T., & Schauer, M. (2010). A randomized controlled pilot study. Can asylum seekers with posttraumatic stress disorder be successfully treated? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39(2), 81–91.

- Neuner, F., Onyut, P. L., Ertl, V., Odenwald, M., Schauer, E., & Elbert, T. (2008). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by trained lay counselors in an African refugee settlement: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(4), 686.

- Neuner, F., Schauer, M., Klaschik, C., Karunakara, U., & Elbert, T. (2004). A comparison of narrative exposure therapy, supportive counselling, and psychoeducation for treating posttraumatic stress disorder in an African refugee settlement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(4), 579–587.

- Nijdam, M. J., Gersons, B. P. R., Reitsma, J. B., de Jongh, A., & Olff, M. (2012). Brief eclectic psychotherapy v. eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 200(3), 224–231.

- Nutt, D. J., & Sharpe, M. (2008). Uncritical positive regard? Issues in the efficacy and safety of psychotherapy. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22(1), 3.

- Pacella, M. L., Armelie, A., Boarts, J., Wagner, G., Jones, T., Feeny, N., & Delahanty, D. L. (2012). The impact of prolonged exposure on PTSD symptoms and associated psychopathology in people living with HIV: A randomized test of concept. AIDS and Behavior, 16(5), 1327–1340.

- Paunovic, N. (2011). Exposure inhibition therapy as a treatment for chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: A controlled pilot study. Psychology, 2(6), 605.

- Peniston, E. G., & Kulkosky, P. J. (1991). Alpha-theta brainwave neurofeedback for Vietnam veterans with combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical Psychotherapy, 4(1), 47–60.

- Pitman, R. K., Altman, B., Greenwald, E., Longpre, R. E., Macklin, M. L., Poire, R. E., & Steketee, G. S. (1991). Psychiatric complications during flooding therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 52(1), 17–20.

- Power, K., McGoldrick, T., Brown, K., Buchanan, R., Sharp, D., Swanson, V., & Karatzias, A. (2002). A controlled comparison of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing versus exposure plus cognitive restructuring versus waiting list in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 9, 229–318.

- Rauch, S., King, A. P., Abelson, J., Tuerk, P. W., Smith, E., Rothbaum, B. O., … Liberzon, I. (2015). Biological and symptom changes in posttraumatic stress disorder treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Depression and Anxiety, 32, 204–212.

- Ready, D. J., Gerardi, R. J., Backscheider, A. G., Mascaro, N., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2010). Comparing virtual reality exposure therapy to present centred therapy with 11 US Vietnam Veterans with PTSD cyberpsychology. Behavior and Social Networking, 13(1), 49–54.

- Reger, G., Koenen-Woods, P., Zetocha, K., Smolenski, D. J., Holloway, K. M., Rothbaum, B. O., & Gahm, G. A. (2016). Randomized controlled trial of prolonged exposure using imaginal exposure vs. virtual reality exposure in active duty soldiers with deployment-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 946–959.

- Resick, P., Nishith, P., Weaver, T. L., Astin, M. C., & Feuer, C. A. (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 867–879.

- Resick, P. A., Wachen, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Pruiksma, K. E., Yarvis, J. S., Peterson, A. L., … Young-McCaughan, S. (2017). Effect of group vs individual cognitive processing therapy in active-duty military seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry (Chicago, IL), 74(1), 28–36.

- Resick, P. A., Wachen, J. S., Mintz, J., Young-McCaughan, S., Roache, J. D., Borah, A. M., & Peterson, A. L. (2015). A randomized clinical trial of group cognitive processing therapy compared with group present-centered therapy for PTSD among active duty military personnel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1058. Epub ahead of print.

- Roberts, N. P., Jones, N., & Bisson, J. I. (2016). Psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4), Art. No.: CD010204. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010204.pub2

- Rothbaum, B. (1997). A controlled study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disordered sexual assault victims. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 61(61), 317–334.

- Rothbaum, B., Astin, M. C., & Marsteller, F. (2005). Prolonged exposure versus eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) for PTSD rape victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18, 607–616.

- Rutt, B. T., Oehlert, M. E., Krieshok, T. S., & Lichtenberg, J. W. (2018). Effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure in the Department of Veterans affairs. Psychological Reports, 121(2), 282–302.

- Sautter, F. J., Glynn, S. M., Cretu, J. B., Senturk, D., & Vaught, A. S. (2015). Efficacy of structured approach therapy in reducing PTSD in returning veterans: A randomized clinical trial. Psychological Services, 12(3), 199–212.

- Scheck, M., Schaeffer, J. A., & Gillette, C. (1998). Brief psychological intervention with traumatized young women: The efficacy of eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 25–44.

- Schnurr, P., Friedman, M. J., Engel, C. C., Foa, E. B., Shea, M. T., Chow, B. K., … Bernardy, N. (2007). Cognitive behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in women. JAMA, 28, 820–830.

- Schnurr, P., Friedman, M. J., Foy, D. W., Shea, M. T., Hsieh, F. Y., Lavori, P. W., & Bernardy, N. C. (2003). Randomized trial of trauma-focused group therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 481–489.

- Schnyder, U., Ehlers, A., Elbert, T., Foa, E. B., Gersons, B. P. R., Resick, P. A., … Cloitre, M. (2015). Psychotherapies for PTSD: What do they have in common? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 28186.

- Schnyder, U., Müller, J., Maercker, A., & Wittmann, L. (2011). Brief eclectic psychotherapy for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(4), 564–566. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05440blu

- Schottenbauer, M. A., Glass, C. R., Arnkoff, D. B., Tendick, V., & Gray, S. H. (2008). Nonresponse and dropout rates in outcome studies on PTSD: Review and methodological considerations. Psychiatry, 71(2), 134–168.

- Simon, N., McGillivray, L., Roberts, N. P., Barawi, K., Lewis, C. E., & Bisson, J. I. (2019). Acceptability of internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (i-CBT) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A systematic review. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1646092.

- Sloan, D., Marx, B. P., Bovin, M. J., Feinstein, B. A., & Gallagher, M. W. (2012). Written exposure as an intervention for PTSD: A randomized clinical trial with motor vehicle accident survivors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(10), 627–635.

- Sloan, D., Marx, B. P., Lee, D. J., & Resick, P. A. (2018). A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 75, 233.

- Spence, J., Titov, N., Dear, B. F., Johnston, L., Solley, K., Lorian, C., … Schwenke, G. (2011). Randomised controlled trial of internet delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 28, 541–550.

- StataCorp. (2013). Stata statistical software: Release 13. College Station, TX: Author.

- Stenmark, H., Catani, C., Neuner, F., Elbert, T., & Holen, A. (2013). Treating PTSD in refugees and asylum seekers within the general health care system. A randomized controlled multicenter study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, 641–647.

- Suris, A., Link-Malcolm, J., Chard, K., Ahn, C., & North, C. (2013). A randomized clinical trial of cognitive processing therapy for veterans with PTSD related to military sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26, 28–37.

- Szafranski, D. D., Smith, B. N., Gros, D. F., & Resick, P. A. (2017). High rates of PTSD treatment dropout: A possible red herring? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 47, 91–98.

- Tarrier, N., Pilgrim, H., Sommerfield, C., Faragher, B., Reynolds, M., Graham, E., & Barrowclough, C. (1999a). A randomized trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 13–18.

- Tarrier, N., Pilgrim, H., Sommerfield, C., Faragher, B., Reynolds, M., Graham, E., & Barrowclough, C. (1999b). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy and imaginal exposure in the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 67, 13–18. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.13

- Tarrier, N., Sommerfield, C., Pilgrim, H., & Humphreys, L. (1999). Cognitive therapy or imaginal exposure in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: 12-month follow-up. British Journal of Psychiatry, 175, 571–575.

- Taylor, S. (2003). Outcome predictors for three PTSD treatments: Exposure therapy, EMDR, and relaxation training. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 17(2), 149.

- Taylor, S., Thordarson, D. S., Maxfield, L., Fedoroff, I. C., Lovell, K., & Ogrodniczuk, J. (2003). Comparative efficacy, speed, and adverse effects of three PTSD treatments: Exposure therapy, EMDR, and relaxation training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 330–338.

- Ter Heide, F. J. J., Mooren, T., Kleijn, W., de Jongh, A., & Kleber, R. (2011). EMDR versus stabilisation in traumatised asylum seekers and refugees: Results of a pilot study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2(1), 5881.

- Ter Heide, F. J. J., Mooren, T. M., & Kleber, R. J. (2016). Complex PTSD and phased treatment in refugees: A debate piece. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 28687.

- Thompson, S. G., & Higgins, J. P. (2002). How should meta‐regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1559–1573.

- Tylee, D. S., Gray, R., Glatt, S. J., & Bourke, F. (2017). Evaluation of the reconsolidation of traumatic memories protocol for the treatment of PTSD: A randomized, wait-list-controlled trial. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 3(1), 21–33.

- van Minnen, A., Harned, M. S., Zoellner, L., & Mills, K. (2012). Examining potential contraindications for prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 18805.

- Vaughan, K., Armstrong, M. S., Gold, R., O’Connor, N., Jenneke, W., & Tarrier, N. (1994). A trial of eye movement desensitization compared to image habituation training and applied muscle relaxation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25, 283–291.

- Wagenmans, A., Van Minnen, A., Sleijpen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1430962.

- Wells, A., & Sembi, S. (2012). Metacognitive therapy for PTSD: A preliminary investigation of a new brief treatment. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 35(4), 307–318.

- Wells, A., Walton, D., Lovell, K., & Proctor, D. (2015). Metacognitive therapy versus prolonged exposure in adults with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: A parallel randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39(1), 70–80.

- Yehuda, R., Pratchett, L. C., Elmes, M. W., Lehrner, A., Daskalakis, N. P., Koch, E., & Bierer, L. M. (2014). Glucocorticoid-related predictors and correlates of post-traumatic stress disorder treatment response in combat veterans. Interface Focus, 4(5), 20140048.

- Zandberg, L. J., Rosenfield, D., Alpert, E., McLean, C. P., Foa, E. B., Karatzias, T., … Adams, S. (2016). Predictors of dropout in concurrent treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and alcohol dependence: Rate of improvement matters. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 80, 1–9.

- Zang, Y., Hunt, N., & Cox, T. (2013). A randomised controlled pilot study: The effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy with adult survivors of the Sichuan earthquake. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1.

- Zang, Y., Hunt, N., & Cox, T. (2014). Adapting narrative exposure therapy for Chinese earthquake survivors: A pilot randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 262.

- Zatzick, D. (2012). Toward the estimation of population impact in early posttraumatic stress disorder intervention trials. Depression and Anxiety, 29(2), 79–84.