?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Background: There is ongoing debate as to whether emotion regulation problems should be improved first in order to profit from trauma-focused treatment, or will diminish after successful trauma processing.

Objective: To enhance our understanding about the importance of emotion regulation difficulties in relation to treatment outcomes of trauma-focused therapy of adult patients with severe PTSD, whereby we made a distinction between people who reported sexual abuse before the age of 12, those who were 12 years or older at the onset of the abuse, individuals who met the criteria for the dissociative subtype of PTSD, and those who did not.

Methods: Sixty-two patients with severe PTSD were treated using an intensive eight-day treatment programme, combining two first-line trauma-focused treatments for PTSD (i.e. prolonged exposure and EMDR therapy) without preceding interventions that targeted emotion regulation difficulties. PTSD symptom scores (CAPS-5) and emotion regulation difficulties (DERS) were assessed at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and six month follow-up.

Results: PTSD severity and emotion regulation difficulties significantly decreased following trauma-focused treatment. While PTSD severity scores significantly increased from post-treatment until six month follow-up, emotion regulation difficulties did not. Treatment response and relapse was not predicted by emotion-regulation difficulties. Survivors of childhood sexual abuse before the age of 12 and those who were sexually abused later in life improved equally well with regard to emotion regulation difficulties. Individuals who fulfilled criteria of the dissociative subtype of PTSD showed a similar decrease on emotion regulation difficulties during treatment than those who did not.

Conclusion: The results support the notion that the severity of emotion regulation difficulties is not associated with worse trauma-focused treatment outcomes for PTSD nor with relapse after completing treatment. Further, emotion regulation difficulties improved after trauma-focused treatment, even for individuals who had been exposed to early childhood sexual trauma and individuals with dissociative subtype.

Antecedentes: hay un debate en curso sobre si los problemas de regulación de las emociones deben mejorar primero para beneficiarse del tratamiento centrado en el trauma o si disminuirán después del procesamiento exitoso del trauma.

Objetivo: mejorar nuestra comprensión sobre la importancia de las dificultades de la regulación emocional en relación con los resultados del tratamiento de la terapia centrada en el trauma de pacientes adultos con trastorno de estrés postraumático grave, para lo cual hicimos una distinción entre las personas que informaron abuso sexual antes de los 12 años, aquellas que tenían 12 o más años al inicio del abuso, personas que cumplieron con los criterios para el subtipo disociativo de TEPT y aquellos que no lo hicieron.

Métodos: Sesenta y dos pacientes con trastorno de estrés postraumático grave fueron tratados mediante un programa de tratamiento intensivo de ocho días, que combina dos tratamientos de primera línea centrados en el trauma para el trastorno de estrés postraumático (exposición prolongada y EMDR) sin intervenciones previas dirigidas a las dificultades de regulación emocional. Los puntajes de síntomas de TEPT (CAPS-5) y las dificultades de regulación emocional (DERS) se evaluaron antes, después del tratamiento y a los seis meses de seguimiento.

Resultados: la severidad del TEPT y las dificultades de regulación emocional disminuyeron significativamente después del tratamiento centrado en el trauma. Si bien los puntajes de severidad del TEPT aumentaron significativamente desde el postratamiento hasta los seis meses de seguimiento, las dificultades de regulación emocional no lo hicieron. La respuesta al tratamiento y la recaída no fueron precedidas por las dificultades de regulación de las emociones. Los sobrevivientes de abuso sexual infantil antes de los 12 años y aquellos que fueron abusados sexualmente más tarde en la vida mejoraron igualmente bien con respecto a las dificultades de regulación de las emociones. Las personas que cumplieron con los criterios del subtipo disociativo de TEPT mostraron una mayor disminución en las dificultades de regulación emocional durante el tratamiento que aquellos que no lo hicieron.

Conclusión: Los resultados apoyan la noción de que la gravedad de las dificultades de regulación de las emociones no se asocia con peores resultados del tratamiento centrado en el trauma para el TEPT ni con recaídas después de completar el tratamiento. Además, las dificultades de regulación de las emociones mejoraron después del tratamiento centrado en el trauma, incluso para las personas que habían estado expuestas a traumas sexuales en la primera infancia y las personas con subtipo disociativo.

背景:: 关于情绪调节问题是否应该首先得到改善, 以便从以聚焦创伤治疗中获益, 还是在创伤处理成功后有所减轻, 仍存在争议。

目标: 通过区分报告性虐待发生在12岁之前的人和虐待开始时已年满12岁或12岁以上的人, 符合PTSD分离亚型标准的人和不符合的人, 加深我们对情绪调节困难针对重度PTSD成年患者的密集型聚焦创伤治疗结果的重要性的认识。

方法: 对62例重度PTSD患者进行了为期8天的密集型治疗, 结合了两种针对PTSD的一线聚焦创伤治疗 (即延长暴露和EMDR疗法), 没有进行针对情绪调节困难的干预。在治疗前, 治疗后和六个月的随访中评估了PTSD症状得分 (CAPS-5) 和情绪调节困难 (DERS) 。

结果: 聚焦创伤治疗后, PTSD的严重程度和情绪调节困难显著降低。从治疗后到六个月的随访中, PTSD的严重程度得分显著提高, 但情绪调节方面的困难却没有。情绪调节困难不能预测治疗反应和复发。在情绪调节方面, 12岁之前遭受童年期性虐待的幸存者和12岁之后遭受性虐待的幸存者同样得到了改善。符合PTSD分离亚型标准的患者与不符合标准的患者相比, 在治疗过程中情绪调节困难减少幅度更大。

结论: 结果支持以下观点:情绪调节困难的严重程度与更差的PTSD聚焦创伤治疗结果或完成治疗后的复发无关。此外, 聚焦创伤治疗后, 情绪调节困难得到改善, 即使对于那些遭受早期童年期性创伤的人和具有分离亚型的人也是如此。

1. Introduction

Compared to single trauma in adulthood, interpersonal (sexual) trauma during childhood is assumed to be associated with long-lasting problems in emotion regulation (Cloitre et al., Citation2012). This is one of the reasons why the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) the World Health Organization (WHO) included a new diagnostic category called ‘Complex PTSD’, consisting of persistent problems in emotion regulation, self-perception and interpersonal relationships, in addition to core PTSD symptoms (Maercker et al., Citation2013).

It has been argued that individuals with Complex PTSD, and PTSD following interpersonal and prolonged trauma during childhood, are characterized by loss of emotional and social competencies and therefore would carry a risk for the processing of traumatic memories as this may be too emotionally overwhelming (Cloitre, Garvert, Weiss, Carlson, & Bryant, Citation2014; Cloitre, Koenen, Cohen, & Han, Citation2002; Walsh, DiLillo, & Scalora, Citation2011). The notion that individuals with emotion regulation difficulties may be a difficult subgroup within those suffering from PTSD is supported by the results of a recent meta-analysis that reported on 51 RCTs that examined the effectiveness of psychological treatments with individuals who were likely to meet criteria of Complex PTSD (Karatzias et al., Citation2019). In fact, the authors found no evidence that either CBT, exposure alone, or EMDR therapy have proven to be superior to any non-specific therapies with regard to influencing affect dysregulation.

The difficulty to influence emotion dysregulation in individuals with complex trauma histories and PTSD using trauma-focused treatment caused experts in the trauma field to pay attention to the development of emotion regulation and interpersonal skills before the start of therapy (Cloitre et al., Citation2012; Cloitre, Miranda, Stovall-McClough, & Han, Citation2005; Ford, Citation2015). This is the reason why the first treatment guidelines of the International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) regarding Complex PTSD, recommended a ‘stabilization phase’ prior to trauma-focused treatment, aimed at reducing self-regulation problems and improving emotional, social, and psychological competencies, to ensure that individuals would be better able to tolerate treatment (Cloitre et al., Citation2012). In their most recent treatment guidelines, the ISTSS guideline committee states that treatment should primarily be focused on facilitating the processing of childhood memories, but also propose a ‘personalized medicine’ approach aimed at stability and symptom management because of ‘reduced treatment benefit among those with Complex PTSD compared to PTSD when using established therapies’ (ISTSS, Citation2018, p. 4).

Whether individuals suffering from Complex PTSD would need forms of interventions, in which skills in emotion regulation are trained prior to trauma-focused therapy is a topic of ongoing debate (Cloitre, Citation2015; De Jongh et al., Citation2016). One could reason that PTSD symptoms in itself cause or maintain emotion regulation difficulties and, consequently, treating PTSD symptoms directly will lead to a decrease in these emotional dysregulations. One of the few studies that tested this assumption came from Jerud, Zoellner, Pruitt, and Feeny (Citation2014). They examined changes in emotion regulation among 200 heterogeneous PTSD patients with and without a history of childhood abuse, who received a standard trauma-focused treatment programme, without training emotion regulation skills prior to therapy (10 weeks Prolonged Exposure therapy or sertraline). The results indeed showed improvements in both PTSD symptoms and emotion regulation skills at post-treatment and follow-up. What is more, it was found that adults with a history of childhood abuse (i.e. those for whom it was assumed that emotion regulation had severely been disrupted) and adults without a history of childhood abuse (but had been exposed to other traumatic experiences) benefited equally well from trauma-focused treatment both in terms of improvements of PTSD symptoms and emotion regulation. Further support for the notion that emotion regulation improves following successful treatment of PTSD was found in another study of this research group, showing that patients with high pre-existing emotion regulation difficulties experienced greater improvements over the course of trauma-focused treatment in emotion regulation skills as compared to those scoring low at baseline (Jerud, Pruitt, Zoellner, & Feeny, Citation2016). The results of both studies suggest that emotion regulation difficulties do not necessarily lead to reduced treatment effects or to more emotional dysregulation in relation to trauma-focused treatment but rather improve from treating the underlying PTSD symptoms.

Given the contradictions in the literature concerning emotion regulation being either a consequence of interpersonal trauma like (childhood) sexual abuse, or a symptom of severe PTSD,Footnote1 it is important to enhance our understanding as to how emotion regulation difficulties react to intensive trauma-focused treatment (i.e. prolonged exposure combined with EMDR therapy). Building on conclusions of the studies conducted by Jerud et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016), it was hypothesized that following treatment (1) PTSD severity would significantly decrease, and (2) emotion regulation difficulties, as indexed at baseline, would significantly decline. Furthermore, the long-term changes of PTSD and emotion regulation difficulties after treatment were explored. In addition, we explored (3) to what extent baseline emotion regulation difficulties would predict the outcome of treatment in terms of both response at post-treatment, and relapse at six month follow-up. Moreover, because emotion regulation difficulties have been found to be associated with sexual abuse in childhood, we investigated (4) whether patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse that took place before the age of 12 would display a significantly different treatment response regarding their level of emotion regulation than those who were 12 years or older at the onset of abuse. Finally, a factor that could influence the extent to which people are able to regulate their emotions is dissociation. It has been argued that dissociation is a phenomenon that might negatively influence the outcome of trauma-focused treatments, and that people suffering from depersonalization and/or derealization could benefit from skill training in emotion regulation prior to trauma-focused treatment (Lanius, Brand, Vermetten, Frewen, & Spiegel, Citation2012). This is the reason that we were also interested in determining (5) whether individuals who met the criteria for the dissociative subtype of PTSD would show a significantly poorer improvement in emotion regulation during treatment not containing any form of emotion regulation training than patients who did not.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants of this study took part in the intensive in-patient treatment programme at the Psychotrauma Expertise Centre (PSYTREC), a mental health care centre in the Netherlands. In the period May–August 2018, a total number of 111 participants gave their informed consent and were eligible for research. Four participants dropped out of treatment before completion. At post-treatment, there were no missing data on the CAPS-5, but at six month follow-up, data of the CAPS-5 were missing for 45 participants. Including the follow-up measures, complete data on the CAPS-5 were available for 62 participants, and this group was used for all analyses.

Ethical exemption of the study protocol was appointed by the Medical Ethics Review Committee of VU University Medical Centre (registered with the US Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) as IRB00002991, FWA number FWA00017598).

3. Procedure

Patients were referred by their general practitioner, psychiatrist, or psychologist, after which they were invited for two intake sessions to assess whether they fulfilled the DSM-5 criteria for PTSD (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Included to treatment were individuals who: (1) had a diagnosis of PTSD according to the DSM-5, (2) were at least 18 years old, (3) had sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language to undergo treatment, and (4) did not attempt suicide in the three months prior to intake. There were no further exclusion criteria, such as the presence of a dissociative disorder, psychotic disorder, personality problems, non-suicidal self-injury, or suicidality.

During the intake procedure, written informed consent was obtained for using the data for scientific research purposes, and the Dutch version of the Clinical Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS), and the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview PLUS (MINI-PLUS) were administered. The CAPS and MINI interviews were administered by trained clinical psychologists and master students in psychology. After successful completion of the two intake sessions, patients participated in a brief and intensive treatment programme.

At post-treatment, one week after the last treatment day, the CAPS-5 was administered at our clinic, and the DERS was completed online at home. At the follow-up at six months, patients completed the DERS online and the CAPS-5 was assessed by phone by a research assistant who was blind to the study hypotheses.

4. Treatment programme

The treatment programme consisted of two consecutive periods of four days per week. There was no preparation or stabilization phase before the start of the treatment. During the treatment, patients stayed at the facility because of the busy schedule of the treatment programme. Between the two periods of four treatment days, patients went home for three days. Every treatment day consisted of one 90-minute Prolonged Exposure (PE) therapy session and one 90-minute session of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. These sessions took place individually, each session being delivered by another psychologist, according to the principles of ‘therapist rotation’ (Van Minnen et al., Citation2018). Psychologists who provided therapy sessions completed the necessary training in PE and EMDR therapy. For PE, the principles provided by Foa, Hembree, and Rothbaum (Citation2007) were followed. EMDR therapy was provided according to the Dutch version of the treatment protocol (De Jongh & Ten Broeke, Citation2013) developed by Shapiro (Citation2018).

Between the trauma-focused treatment sessions, patients took part in a physical activity programme, consisting of six sessions of low- and high-intensity, and in- and outdoor activities (e.g. mountain biking, hiking, badminton). During the day, patients received five sessions of group psycho-education concerning relevant PTSD-related topics. The physical activity programme and psycho-education were offered in groups. For a more detailed overview of the treatment programme, see Van Woudenberg et al. (Citation2018).

5. Measures

5.1. PTSD severity

To assess the PTSD diagnosis and severity of PTSD symptoms, the Dutch version of the Clinical Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5; Boeschoten et al., Citation2018; Weathers et al., Citation2017) was administered at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and six month follow-up. The CAPS is one of the most widely used structured clinical interviews for ascertaining the diagnosis of PTSD according to the DSM-5 with adequate psychometric properties (Boeschoten et al., Citation2018; Weathers et al., Citation2017). The CAPS includes two separate items representing the symptoms of the dissociative subtype: derealization and depersonalization. Using the conservative score rule of frequency ≥ 2 and severity ≥ 2 on at least one of these items, patients were classified as meeting or not meeting the criteria of the dissociative subtype.

5.2. Emotion regulation difficulties

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004) is a self-report questionnaire and, for the present study, the Dutch version of the DERS (Neumann, van Lier, Gratz, & Koot, Citation2010) was administered at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and six month follow-up. The DERS consists of 36-items and asks patients to indicate how often the items apply to themselves on a scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always), resulting in a total possible DERS score ranging from 36 to 180. Examples of items are: ‘When I’m upset, I lose control over my behaviour’, ‘When I’m upset, I become angry with myself for feeling that way’, ‘When I’m upset, I have difficulty focusing on other things’, and ‘I have no idea how I am feeling’. The DERS consists of six subscales: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in goal directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004). Reversed items of the DERS were recoded resulting in higher scores for greater emotion regulation difficulties. In the present sample, the reliability of the total DERS scale was high (α = .93). The values of the subscales were satisfactory to high (range .79–.90).

5.3. Trauma type

The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5; Boeschoten, Bakker, Jongedijk, & Olff, Citation2014; Weathers et al., Citation2013) was used in order to describe our study sample in terms of trauma type. The LEC-5 is a self-report measure that assesses exposure to 17 events known to potentially result in PTSD. The LEC-5 demonstrated adequate psychometric properties.

5.4. Index trauma

For analysis purposes, the personalized treatment plan of the participants, as established during the intake assessments, was analysed to divide participants in two trauma groups; that is, an index trauma of sexual abuse that has started before the age of 12, and an index trauma of sexual abuse that started at the age of 12 or later. Both categories of traumatic events were only scored if it actually happened to the respondent themselves (excluding witnessing or having learned about sexual abuse).

5.5. Comorbidity

Potential comorbid disorders and suicidal risk were assessed with the Dutch version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview PLUS (MINI-PLUS; Lecrubier et al., Citation1997; Overbeek, Schruers, & Griez, Citation1999). The MINI is a well-validated structured diagnostic interview used to determine DSM-IV criteria with high psychometric properties for most diagnoses (Lecrubier et al., Citation1997). For each disorder, dichotomous scores could be obtained (yes or no) and suicidal risk was categorized as ‘low’, ‘medium’, and ‘high’.

6. Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the primary measures (CAPS-5 and DERS), comorbidity and suicidal risk, and for sex, age, and trauma-exposure. Preliminary analyses were conducted to ensure no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, sphericity, multicollinearity, and homoscedasticity. Next, the group with and without missing post-treatment and six month follow-up data on the DERS and CAPS-5 were compared on baseline characteristics using analyses of variance and Pearson Chi-square analyses. Two repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) were used to compare means of CAPS-5 and DERS between pre- and post-treatment and six month follow-up. Given that, regarding the CAPS-5, the assumptions of normality and of sphericity at post-treatment and at follow-up measures were violated, a Friedman test was applied as a non-parametric variant of the RM-ANOVA. Concerning the DERS, no outliers were detected and the scores were normally distributed at each time point, as assessed by Shapiro-Wilk’s test (p > .05), and all other assumptions of the test were met. To examine whether emotion regulation difficulties at baseline would be a predictor of treatment response, a multiple regression analysis was carried out using only participants with complete pre- and post-measurements on the CAPS-5, with the baseline DERS score as predictor variable, the difference score of pre- and post-treatment CAPS-5 scores as the criterion variable, while controlling for the influence of the pre-treatment CAPS-5 scores. Finally, to examine whether baseline emotion regulation problems would be a predictor of treatment relapse, a multiple regression analysis was conducted with the baseline DERS score as predictor variable and the difference between post-treatment and follow-up CAPS-5 scores as outcome variable, controlled for the influence of pre-treatment CAPS-5 scores. In order to test whether emotion regulation differed between sexual abuse groups, from the total group of participants (n = 62), those who were sexually abused (n = 54) were divided into two groups, depending on the age of onset of sexual abuse. A mixed analysis of variance was conducted to determine possible differences between patients who had experienced sexual abuse at an age below 12 years and above the age of 12 years on the DERS, across three time points (i.e. before and after trauma-focused treatment and with six month follow-up). The group with trauma other than sexual abuse was not included in this analysis because it consisted of only eight patients. Therefore, the number of individuals that were included in this specific analysis was 54. Also, a mixed analysis of variance was conducted to determine possible differences in emotion regulation between patients who had the dissociative subtype of PTSD at baseline and those who did not. This analysis pertained to 62 individuals. Cohen’s d was used to assess the magnitude of effect, an effect size of 0.2 or less was considered as a small effect, 0.5 as a medium effect, and 0.8 or greater as a large effect (Cohen, Citation1988). The data analyses were conducted with SPSS 25 (IBM SPSS) and all statistical analyses were evaluated at a significance level of p ≤ .05.

7. Results

7.1. Sample characteristics

For an overview of the demographics and baseline measurements across the different trauma groups see . While 32 patients (51.6%) reported a history of sexual abuse before the age of 12, 22 patients (35.5%) had experienced sexual abuse at the age of 12 or later. Eight patients did suffer trauma history other than sexual abuse (or witnessed/learned about sexual abuse without actually experiencing it). The group with trauma other than sexual trauma was not included because of its small size (n = 8). There were no significant baseline differences between the two trauma groups.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the total sample at baseline (N = 62) and the two trauma groups

7.2. Change in PTSD severity

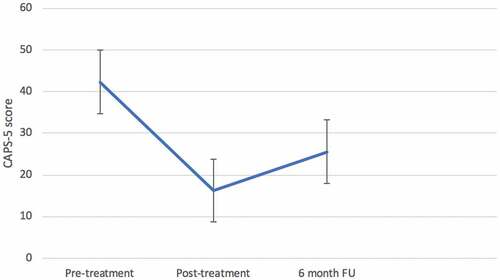

A Friedman test revealed that the CAPS-5 scores were statistically significantly different at the three time points [χ2 (2) = 62.78, p < .001; see ]. Post-hoc analyses (two tailed) showed statistically significant decreases in scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment [Z = −6.72, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 1.81], and pre-treatment to follow-up [Z = −5.12, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.84]. CAPS-5 scores significantly increased from post-treatment to follow-up [Z = −4.04, p < .001; Cohen’s d = −0.56].

7.3. Changes in emotion regulationFootnote2

Analysis of variance showed a significant main effect of treatment over time [F(2, 104) = 18.81, p < .001, = 0.266]. Post-hoc analyses (two-tailed) revealed a significant decrease in DERS scores from pre- to post-treatment [t(58) = 5.61, p < .001; Cohen’s d = 0.73], and from pre-treatment to follow-up [t(54) = 4.18, p < .001, Cohen’s d = 0.56]. The increase in DERS scores from post-treatment to six month follow-up was not significant [t(52) = −1.78, p = .082].

7.4. Baseline emotion regulation difficulties as a predictor of treatment response and relapse

Multiple linear regression analyses revealed that pre-treatment DERS scores, controlled for pre-treatment CAPS-5 scores, did not significantly predict treatment response [F(2, 59) = 2.62, p = .081, R2adj = 0.05] nor treatment relapse [F(3, 58) = 1.72, p = .173, R2adj = 0.04].Footnote3

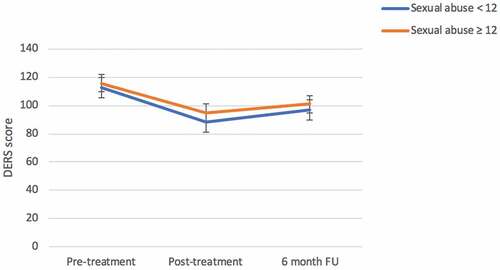

7.5. Emotion regulation compared between two sexual abuse groups

The mixed repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of time [F(2, 90) = 14.32, p < .001, = 0.241] with both groups showing a change in DERS scores over the three time periods (see ). The main effect comparing both trauma groups was not significant [F(1, 45) = .53, p = .472,

= 0.012] indicating that the DERS scores were not significantly different between the sexual abuse age < 12 years group and the sexual abuse age ≥ 12 years group at pre-treatment (M =112.84, SD = 25.08 vs M =115.64, SD = 19.23), at post-treatment (M =88.61, SD = 25.06 vs M =95.00, SD = 27.87), and at six month follow-up (M =96.97, SD = 32.73 vs M =101.05, SD = 30.60; see ). The interaction between time and trauma group was not significant [F(2, 90) = 0.22, p = .801,

= 0.005] which suggests that the change over time did not differ between the trauma groups.

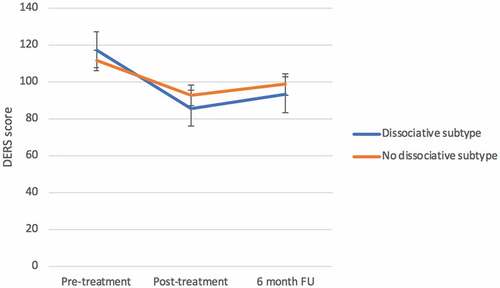

7.6. Emotion regulation compared between individuals with and without dissociative subtype

The mixed repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant main effect of time [F(2, 102) = 20.20, p < .001, = 0.284] with both groups showing a change in DERS scores over the three time periods (see ). The main effect comparing both dissociation groups was not significant [F(1, 51) = 0.15, p = .700,

= 0.003], indicating that the DERS scores were not significantly different between the dissociation group and the group without dissociation at pre-treatment (M =117.41, SD = 20.99 vs M =111.65, SD = 22.81), at post-treatment (M =85.68, SD = 25.30 vs M =92.77, SD = 28.15), and at six month follow-up (M =93.05, SD = 29.03 vs M =98.55, SD = 33.12). The interaction between time and trauma group was also not significant [F(2, 102) = 1.44, p = .242,

= 0.027] which suggests that the change over time did not differ between the dissociation groups.

8. Discussion

The results of the present study showed that intensive trauma-focused therapy was effective in that patients’ severity of PTSD symptoms significantly decreased and emotion regulation significantly improved. Emotion regulation problems at baseline were also not predictive of PTSD symptom reduction after treatment. Improvement of emotion regulation difficulties proved not to be different for survivors of childhood sexual abuse that started before the age of 12 years, compared to those whose sexual abuse started later in life, and not different for individuals who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of the dissociative subtype of PTSD as indexed by the CAPS-5, compared to those who did not meet the criteria of this condition.

The statistically significant decrease in PTSD severity following intensive trauma-focused treatment, supports our hypothesis that following intensive trauma-focused treatment PTSD severity would significantly decrease, and is consistent with recent studies demonstrating positive treatment outcomes of non-phased trauma-focused treatment for individuals suffering from PTSD, delivered in a brief and intensive format. This has been found to hold true for individuals receiving prolonged exposure therapy delivered in an intensive format of 10 days over two weeks (Foa et al., Citation2018), seven days intensive cognitive therapy (Ehlers et al., Citation2014), and EMDR therapy, either as stand-alone therapy (Bongaerts, Van Minnen, & De Jongh, Citation2017) or combined with prolonged exposure therapy delivered in a format of eight days over a two-week period (Van Woudenberg et al., Citation2018; Wagenmans, Van Minnen, Sleijpen, & De Jongh, Citation2018; Zoet, Wagenmans, Van Minnen, & De Jongh, Citation2018). The relapse of PTSD symptoms at six month follow-up is – albeit undesirable – not fully unexpected as it is in accordance with earlier findings among a similar sample of individuals undergoing the same treatment programme (Van Woudenberg et al., Citation2018), and has been observed in other treatment programmes with a massed format as well (e.g. Bryan et al., Citation2018). Possibly, there is a subgroup of patients with complex trauma histories who tend to show a slight relapse in the long term. This response may be explained by the fact that some individuals suffer from such an overwhelming amount of trauma memories that these could hardly be worked through within a brief period of eight days. Another explanation for the relapse might be that individuals suffering from severe PTSD are also those with many vulnerabilities and comorbidities; that is, they can easily end up in circumstances that are potentially traumatic again, and thus easily fall prey to revictimization. Yet, it is important to note that the overall size of the effect of the intensive treatment programme between pre-treatment and six month follow-up was still quite large (Cohen’s d = 0.84), and comparable to other brief and intensive treatment programmes for PTSD (for an overview see Wachen, Dondanville, Evans, Morris, and Cole, Citation2019).

Besides a decrease in PTSD symptoms, we found a significant reduction of emotion regulation difficulties from pre- to post-treatment, and these results were maintained at follow-up. These results were supportive of our hypothesis that patients’ emotion regulation difficulties would significantly decrease following an intensive trauma-focused treatment programme even though their treatment was not preceded by a stabilization phase aimed at training emotion regulation skills. To this end, our results are consistent with the previous findings of Jerud et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016) who also did not teach their study participants specific emotion regulations skills prior to the study, and found small to medium effects (Cohen’s d < 0.40) over the course of regular trauma-focused treatment (10 weekly 90–120 min sessions) on emotion regulation. In this light it is important to note that in contrast to Jerud et al. (Citation2014, Citation2016), in the present study those individuals with the most severe impairments in emotion regulation were not excluded. Overall, few exclusion criteria were applied to patients, allowing treatment to very vulnerable individuals. This may be the reason why patients of the current sample showed substantially higher baseline scores on emotion regulations difficulties as compared to individuals in the original DERS validation studies (Gratz & Roemer, Citation2004; Neumann et al., Citation2010), and several other studies that used the DERS (Cloitre et al., Citation2019; Tripp, McDevitt-Murphy, Avery, & Bracken, Citation2015). Therefore, it is all the more interesting that the current sample showed a large and relatively stable improvement in emotion regulation (Cohen’s d = 0.88 from pre- to post-treatment, and 0.62 from pre-treatment to follow-up), which may be due to the intensity of treatment (i.e. 16 sessions of 90 minutes within two weeks).

Perhaps one of the most important findings is that both treatment response and relapse could not be predicted by emotion regulation difficulties as indexed at baseline. Certainly given the debate about the need of a preceding stabilization phase to address emotion regulation difficulties of PTSD-patients prior to trauma-focused therapy (see Cloitre, Citation2015; De Jongh et al., Citation2016), and the widely held belief among clinicians that the lack thereof would lead to reduced treatment success or worse outcomes, i.e. by emotionally overwhelming the patient (Cloitre et al., Citation2011). Interestingly, pre-treatment emotion regulation difficulties, controlled for pre-treatment CAPS-5 scores, together explained only 5% of the variance in change in PTSD severity after treatment. This suggests that factors other than pre-existing emotion regulation difficulties (e.g. the combination of evidence-based therapies, the therapeutic relationship, motivation of patients, the additional effect of physical activities, psycho-education, and the inpatient setting) contributed to patients’ treatment success.

The results add to the findings from a similar sample in terms of treatment, PTSD severity, and comorbidities, also showing that the presence of a history of childhood sexual abuse before the age of 12 did not have a detrimental effect on PTSD treatment outcome (Wagenmans et al., Citation2018). More importantly, our results were not supportive of our hypothesis that survivors of childhood sexual abuse would differ in emotion regulation difficulties at baseline compared to those who were sexually abused later in life. This result, and the fact that both groups improved similarly well with regard to emotion regulation difficulties following treatment, is fully in line with the results of Jerud et al. (Citation2014). To this end, the results of the present study further disconfirm the common held belief among clinicians that childhood sexual abuse has detrimental effects on emotion regulation, and could cause such severe emotion regulation deficits that trauma-focused treatments must be augmented with phase-based interventions explicitly targeting emotion regulation before trauma processing (De Jongh et al., Citation2016).

A number of limitations of the present study need to be noted. First, by the time of data collection there was no validated instrument available to assess Complex PTSD. However, given that emotion regulation is one of the three symptom clusters added to the ICD-11 Complex PTSD diagnosis, we considered it crucial to elaborate on the issue of Complex PTSD in our paper, particularly because of the possible treatment implications that are subject to debate in the field (see De Jongh et al., Citation2016). The severity of the PTSD in our sample, the relatively high scores on emotional dysregulation, and the high prevalence of interpersonal (sexual) traumatic experiences in childhood, give reason to believe that the results are generalizable to the population of individuals that meet this new diagnosis of Complex PTSD. Secondly, most patients (87.1%) reported sexual abuse as their index trauma (see ). This means that our findings may not be generalizable to a population of patients that has experienced other forms of trauma than sexual abuse. On the other hand, one of our previous studies, in exactly the same setting with the same intensive trauma-focused therapy format, found no differences between treatment outcomes of individuals who reported to have experienced sexual abuse and those with other type of traumas. In other words, it is not likely that those with a history of childhood sexual abuse would respond differently in terms of response to trauma-focused treatments than other groups of patients (Wagenmans et al., Citation2018). Thirdly, it is not certain whether the trauma-focused treatment was the beneficial element improving emotion regulation and diminishing PTSD symptoms. The present study combined multiple treatment components during the intensive trauma-focused treatment programme such as prolonged and in vivo exposure therapy, EMDR therapy, psycho-education, and physical activities. Accordingly, given that the specific beneficial effects of these different modules is unknown, these may all have contributed to the decrease of PTSD symptom severity and improvement of emotion regulation. Fourthly, and related to this, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the long-term effects of our intensive trauma-focused programme on emotion regulation, given the fact that it is impossible to control for other factors, such as the amount of aftercare patients may have received, or the possibility that patients could have been exposed to new traumatic events. Lastly, but most importantly, the present study lacked a control group and a randomized design, by which it remains unknown to what extent the change can be contributed to our treatment per se, and whether a stabilization phase prior to the intensive trauma-focused therapy would have resulted in even larger treatment effects.

In conclusion, although further work is required to gain a more complete understanding as to how emotion regulation difficulties are related to the treatment response of patients with severe PTSD, the present findings provide disconfirming evidence for the notion that emotion dysregulation in individuals suffering from severe PTSD – due to childhood sexual abuse or an elevated level of dissociation – needs to be improved prior to trauma processing therapy sessions to successfully undergo trauma-focused treatment. To this end, the results support the notion that emotion regulation difficulties are merely trauma-related phenomena that reduce following the resolution of PTSD symptoms. Clearly, long-term results of well-designed randomized clinical trials, directly comparing trauma-focused therapy, with and without a preceding stabilization phase, such as those that are currently underway (e.g. Oprel et al., Citation2018; Van Vliet, Huntjens, van Dijk, & De Jongh, Citation2018) should demonstrate whether a stabilization phase prior to trauma-focused therapy could still be beneficial to certain subgroups of trauma-exposed individuals, or not.

Disclosure statement

Ad De Jongh receives income from published books on EMDR therapy and for the training of postdoctoral professionals in this method. Agnes Van Minnen receives income for published book chapters on PTSD and for the training of postdoctoral professionals in prolonged exposure. The other authors do not have competing interests.

Notes

1. Complex PTSD is a new mental health condition for which only recently a diagnostic instrument has become available (i.e. International Trauma Questionnaire, Cloitre et al., Citation2018). Although the patients in our study sample were likely to meet criteria for clinically significant levels of one or more symptom clusters of Complex PTSD, we cannot refer to this classification. That is the reason why in the current manuscript we use the term ‘severe PTSD’ when we refer to the patient characteristics of our study sample.

2. Possible differences on the DERS between the group with (N = 9) and without (N = 53) missing data, at post-treatment and at follow-up, showed only significant differences on age, with individuals with missing DERS data being younger than those with complete data (t(60) = 2.07, p = .043).

3. There was a significant correlation between pre-treatment CAPS-5 and DERS scores: r = .498, p < .001. There was also a significant correlation between post-treatment CAPS-5 and DERS scores: τ = .367, p < .001.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®) (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Boeschoten, M. A., Bakker, A., Jongedijk, R. A., & Olff, M. (2014). PTSS checklist voor de DSM-5 (PCL-5) [PTSD checklist for the DSM-5 (PCL-5)]. Diemen: Arq Academy.

- Boeschoten, M. A., Van der Aa, N., Bakker, A., Ter Heide, F. J. J., Hoofwijk, M. C., Jongedijk, R. A., … Olff, M. (2018). Development and evaluation of the Dutch clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1546085.

- Bongaerts, H., Van Minnen, A., & De Jongh, A. (2017). Intensive EMDR to treat patients with complex posttraumatic stress disorder: A case series. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 11(2), 84–11.

- Bryan, C. J., Leifker, F. R., Rozek, D. C., Bryan, A. O., Reynolds, M. L., Oakey, D. N., Roberge, E. (2018). Examining the effectiveness of an intensive, 2-week treatment program for military personnel and veterans with PTSD: Results of a pilot, open label, prospective cohort trial. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74, 2070–2081. doi:10.1002/jclp.22651

- Cloitre, M. (2015). The “one size fits all” approach to trauma treatment: Should we be satisfied? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 27344.

- Cloitre, M., Courtois, C., Ford, J., Green, B., Alexander, P., Briere, J., & Van der Hart, O. (2012). The ISTSS expert consensus treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Retrieved November, 5, 2012. Retrieved from http://www.traumacenter.org/products/pdf_files/ISTSS_Complex_Trauma_Treatment_Guidelines_2012_Cloitre,Courtois,Ford,Green,Alexander,Briere,Herman,Lanius,Stolbach,Spinazzola,van%20der%20Kolk,van%20der%20Hart.pdf

- Cloitre, M., Courtois, C. A., Charuvastra, A., Carapezza, R., Stolbach, B. C., & Green, B. L. (2011). Treatment of Complex PTSD: Results of the ISTSS expert clinician survey on best practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 24, 615–627.

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Weiss, B., Carlson, E. B., & Bryant, R. A. (2014). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder: A latent class analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25097.

- Cloitre, M., Khan, C., Mackintosh, M., Garvert, D., Henn-Haase, C., Falvey, E., & Saito, J. (2019). Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ACES and physical and mental health. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 11, 82–89.

- Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067.

- Cloitre, M., Miranda, R., Stovall-McClough, K. C., & Han, H. (2005). Beyond PTSD: Emotion regulation and interpersonal problems as predictors of functional impairment in survivors of childhood abuse. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 119–124.

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C., Bisson, J., Roberts, N., Maercker, A., … Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138, 536–546.

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- De Jongh, A., Resick, P. A., Zoellner, L. A., van Minnen, A., Lee, C. W., Monson, C. M., … Bicanic, I. A. (2016). Critical analysis of the current treatment guidelines for complex PTSD in adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 359–369.

- De Jongh, A., & Ten Broeke, E. (2013). Handboek EMDR: Een geprotocolleerde behandelmethode voor de gevolgen van psychotrauma [EMDR manual: A protocolised treatment method for the consequenes of psychotrauma]. Amsterdam: Pearson Assessment and Information B.V.

- Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., Grey, N., Wild, J., Liness, S., Albert, I., … Clark, D. M. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of 7-day intensive and standard weekly cognitive therapy for PTSD and emotion-focused supportive therapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 294–304.

- Foa, E. B., Hembree, E. A., & Rothbaum, B. O. (2007). Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences therapist guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Foa, E. B., McLean, C. P., Zang, Y., Rosenfield, D., Yadin, E., Yarvis, J. S., & Peterson, A. L. (2018). Effect of prolonged exposure therapy delivered over 2 weeks vs 8 weeks vs present centered therapy on PTSD symptom severity in military personnel: A randomized clinical trial. Journal American Medical Association, 319(4), 354–364.

- Ford, J. D. (2015). Complex PTSD: Research directions for nosology/assessment, treatment, and public health. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 27584.

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26(1), 41–54.

- ISTSS Guidelines Committee. (2018). Guidelines position paper on Complex PTSD in adults. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Author. Retrieved from http://www.istss.org/getattachment/Treating-Trauma/New-ISTSS-Prevention-and-Treatment-Guidelines/ISTSS_CPTSD-Position-Paper-(Adults)_FNL.pdf.aspx

- Jerud, A. B., Pruitt, L. D., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2016). The effects of prolonged exposure and sertraline on emotion regulation in individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 62–67.

- Jerud, A. B., Zoellner, L. A., Pruitt, L. D., & Feeny, N. C. (2014). Changes in emotion regulation in adults with and without a history of childhood abuse following posttraumatic stress disorder treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(4), 721.

- Karatzias, T., Murphy, P., Cloitre, M., Bisson, J., Roberts, N., Shevlin, M., … Hutton, P. (2019). Psychological interventions for ICD-11 complex PTSD symptoms: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 1–15. doi:10.1017/S0033291719000436

- Lanius, R. A., Brand, B., Vermetten, E., Frewen, P. A., & Spiegel, D. (2012). The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: Rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 701–708.

- Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, D. V., Weiller, E., Amorim, P., Bonora, I., Sheehan, K. H., … Dunbar, G. C. (1997). The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry, 12(5), 224–231.

- Maercker, A., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., Cloitre, M., van Ommeren, M., Jones, L. M., … Reed, G. M. (2013). Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 12(3), 198–206.

- Neumann, A., van Lier, P. A., Gratz, K. L., & Koot, H. M. (2010). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents using the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Assessment, 17(1), 138–149.

- Oprel, D. A. C., Hoeboer, C. M., Schoorl, M., Kleine, R. A., Wigard, I. G., Cloitre, M., & Does, W. (2018). Improving treatment for patients with childhood abuse related posttraumatic stress disorder (IMPACT study): Protocol for a multicenter randomized trial comparing prolonged exposure with intensified prolonged exposure and phase-based treatment. BMC Psychiatry, 18(385), 1–10.

- Overbeek, T., Schruers, K., & Griez, E. (1999). MINI: Mini international neuropsychiatric interview, Dutch version 5.0. 0 (DSM-IV). Maastricht: University of Maastricht.

- Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Basic principles, protocols and procedures, third edition. New York: Guilford Press.

- Tripp, J. C., McDevitt-Murphy, M. E., Avery, M. L., & Bracken, K. L. (2015). PTSD symptoms, emotion dysregulation, and alcohol-related consequences among college students with a trauma history. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 11(2), 107–117.

- Van Minnen, A., Hendriks, L., de Kleine, R., Hendriks, G.-J., Verhagen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Therapist rotation: A novel approach for implementation of trauma-focused treatment in post-traumatic stress disorder. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1492836.

- Van Vliet, N. I., Huntjens, R. J. C., van Dijk, M. K., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Phase-based treatment versus immediate trauma-focused treatment in patients with childhood trauma-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 19, 138.

- Van Woudenberg, C., Voorendonk, E. M., Bongaerts, H., Zoet, H. A., Verhagen, M., Van Minnen, A., … De Jongh, A. (2018). The effectiveness of an intensive treatment programme combining prolonged exposure and EMDR for severe posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1). doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1487225

- Wachen, J. S., Dondanville, K. A., Evans, W. R., Morris, K., & Cole, A. (2019). Adjusting the timeframe of evidence-based therapies for PTSD-massed treatments. Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry, 6, 107–118.

- Wagenmans, A., Van Minnen, A., Sleijpen, M., & De Jongh, A. (2018). The impact of childhood sexual abuse on the outcome of intensive trauma-ftocused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1430962.

- Walsh, K., DiLillo, D., & Scalora, M. J. (2011). The cumulative impact of sexual revictimization on emotion regulation difficulties: An examination of female inmates. Violence against Women, 17(8), 1103–1118.

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Instrument available from the National Center for PTSD. Retrieved from www.ptsd.va.gov

- Weathers, F. W., Bovin, M. J., Lee, D. J., Sloan, D. M., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., … Marx, B. P. (2017). The clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM–5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. doi:10.1037/pas0000486

- Zoet, H. A., Wagenmans, A., Van Minnen, A., & De Jongh, A. (2018). Presence of the dissociative subtype of PTSD does not moderate the outcome of intensive trauma-focused treatment for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1468707.