ABSTRACT

Literature suggests that the occurrence of psychological trauma (PT) from various negative life experiences beyond events mentioned in the DSM-criterion A, receives little to no attention when comorbid with psychosis. In fact, despite research indicating the intricate interplay between PT and psychosis, and the need for trauma-focused interventions (TFI), there continue to be mixed views on whether treating PT would worsen psychosis, with many practitioners hesitating to initiate treatment for this reason. This study, therefore, aimed to understand patient perspectives on the role of PT in psychosis and related treatment options. A qualitative exploratory approach was adopted using in-depth interviews with individuals experiencing psychosis. The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale was administered on a predetermined maximum variation sample resulting in two groups of participants- those with moderate-mild disability (GAF 54–80; n = 10) and those experiencing moderate-severe disability (GAF 41–57; n = 10). With the former group, a semi-structured interview schedule was used, while with the latter, owing to multiple symptoms and difficulty in cognitive processing, a structured interview schedule was used. Results from interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) indicated that traumatic loss was central to experienced PT, but received no attention; this often contributed to the psychotic experience and/or depression, through maintenance factors such as cognitive distortions and attenuated affective responses. Further, the experience of loss seems to be more consequential to trauma-related symptoms than the event itself. Participants opined strongly the need for TFI and the role of it in promoting recovery from psychosis.

La literatura sugiere que la ocurrencia de un trauma psicológico (TP) derivado de experiencias negativas de la vida más allá de los eventos mencionados en el criterio A del DSM, recibe poca o ninguna atención cuando se encuentra en comorbilidad con la psicosis. De hecho, a pesar de que la investigación indica la interacción intrincada entre el TP y la psicosis, y la necesidad de Intervenciones con Foco en el Trauma (IFT), continúa habiendo visiones mixtas respecto a si el tratar el TP podría empeorar la psicosis, con muchos profesionales dudando iniciar tratamiento por este motivo. Este estudio por tanto buscó comprender las perspectivas de los pacientes respecto al rol del TP en la psicosis y las opciones de tratamiento relacionadas. Se utilizó un enfoque cualitativo exploratorio usando entrevistas en profundidad con individuos que experimentaban una psicosis. Se administró la Escala Global de Funcionamiento (GAF) a una muestra predeterminada de máxima variación, resultando en 2 grupos de participantes: aquellos con discapacidad leve a moderada (GAF 54–80; n=10) y quienes presentaban discapacidad moderada a severa (GAF 41–57; n=10). Con el primer grupo se utilizó una entrevista semi-estructurada, mientras que con el segundo, debido a sus múltiples síntomas y dificultad en el procesamiento cognitivo, se utilizó un esquema de entrevista estructurada. Los resultados del análisis fenomenológico interpretativo (AFI) indicaron que la pérdida traumática era central al TP experimentado, pero no recibía atención; esto generalmente contribuía a la experiencia psicótica y/o depresión, a través de factores mantenedores como distorsiones cognitivas y respuestas afectivas atenuadas. Más aún, la experiencia de pérdida parece ser más consecuencia de los síntomas relacionados al trauma que del evento en sí mismo. Los participantes opinaron enérgicamente sobre la necesidad de IFT y su rol en la promoción de la recuperación de la psicosis.

文献表明,DSM标准A中提到未涉及的各种负面生活经历所导致的心理创伤(PT),在和思觉失调并发时几乎没有引起注意。实际上,尽管有研究表明PT与思觉失调之间存在复杂的相互作用,并且需要创伤中心的干预措施(TFI),但关于治疗PT是否会使思觉失调恶化仍存在分歧,许多治疗者为此而犹豫不决。 因此,本研究旨在了解患者如何看待PT在思觉失调和相关治疗方案中的作用。采用定性探索方法,对患者进行深度访谈。总体功能评估量表(GAF)对预先确定的最大变异样本进行施测,区分出两组参与者:患有中轻度残疾(GAF 54–80; n= 10)和中重度残疾(GAF 41–57; n= 10)。 前者使用半结构化的访谈时间表,而后者则由于多种症状和认知加工困难而使用结构化的访谈时间表。解释性现象学分析(IPA)的结果表明,创伤性丧亲是PT的核心,但未引起关注;通过维持因素(例如认知扭曲和减弱的情感反应),通常会导致思觉失调和/或抑郁。此外,与事件本身相比,丧亲经历似乎更易导致创伤相关症状。参加者强烈认为需要TFI并肯定其在促进精神病康复中的作用。

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 70% of the general population (n = 68,894) across 24 countries have experienced traumatic exposure consistent with DSM-5 criterion A (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), with an average of 3.4 trauma exposures per individual (Benjet et al., Citation2016; Kessler et al., Citation2017). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) classifies trauma as that in which an individual is exposed to “actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence” (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Although this definition is specific and attempts to better conceptualize trauma, its causes, and nature; to a pragmatist, the definition remains exclusive to only a part of the population and does not account for variegated stress sensitivities in individuals that might lead other negative life events (NLEs) to be subjectively traumatic. Shapiro (Shapiro, Citation2002) for example, refers to the notion of “small-t’ experiences such as losing a job, as being traumatic to the individual and having a lasting impact on the psyche. The aforementioned criterion A (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), therefore, remains conservative in its approach to including traumatic experiences, which could perhaps impede access to clinical care for many with significant and surmounting effects from ‘small-t’ experiences. Another definition of ‘Psychological Trauma (PT) refers to the unique experience an individual has to an event or enduring conditions in which the ability to integrate emotional experiences is overwhelmed or the individual experiences threat to bodily integrity, sanity or to life’ (Pearlman & Saakvitne, Citation1995). This definition is broad, caters to subjective reactions to events while maintaining the seriousness that the experience posits. This also indicates that various experiences beyond criterion A (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) may be perceived as subjectively traumatic. Therefore, PT in this study is operationalized as an experience an individual has to any negative life event (NLE) that is perceived as beyond one’s resources to cope. The word ‘trauma’ or ‘PT’ will thus include experiences to events meeting DSM-5 criterion A as well as to small-ts.

In fact, considering that PT can arise from a broad range of NLEs beyond those mentioned in the DSM-criterion A (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), studying PT in this context is critical. However, the literature on PT resulting from NLEs including small-t experiences is sparse but is known to have high prevalence rates even within the general population (Benjet et al., Citation2016; Kessler et al., Citation2017). It has also been linked to various psychiatric disorders (McLafferty, Armour, & O’Neill, Citation2016) such as somatoform disorders (Thomson, Randall, & Ibeziako, Citation2014), depression, anxiety, substance use, somatization disorder, eating disorder (Brown et al., Citation2014), and in the case of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), it is a precipitating factor (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Similarly, the association between trauma and severe mental illnesses such as psychosis has gained attention over the last decade and many studies have consistently shown that traumatic events are among the most robust factors in the development of psychosis (Bendall, Alvarez‐Jimenez, & Nelson, Citation2013; Moriyama et al., Citation2018; Okkels, Trabjerg, & Arendt, Citation2016; Sareen, Cox, & Goodwin, Citation2005; Varese et al., Citation2012). Studies have indicated that individuals with trauma exposure have three times the odds of developing psychotic experiences compared to the general population (McGrath et al., Citation2017) and over 68.5% (n = 425) of individuals experiencing psychosis also have experienced trauma exposure (Neria, Bromet, & Sievers, Citation2002). It, therefore, appears that the impact of PT remains in the psyche and interplays with severe mental illnesses (Mueser, Rosenberg, & Goodman, Citation2002).

Literature also suggests that the nomenclature of events related to PT is also varied in literature and used interchangeably as adverse life events (ALE), negative life events (NLEs) and trauma exposure (TE). In this study, the authors will use PT as defined by Pearlman and Saakvitne (Citation1995; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) and as stemming from NLEs. Lastly, a critical reason for the disparity in definitions and conceptualizations is perhaps the surprisingly sparse literature exploring experiencers’ narratives/perspectives on PT. Therefore, since PT refers to the 'experience an individual has to an event … ’ (Pearlman & Saakvitne, Citation1995); any event that the person perceives as traumatic, not restricted to Criterion may be included, not restricted to criterion A (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013); NLEs therefore are the actual event that precedes the experience of PT- a stimulus to PT.

Further, despite the sustained evidence that PT is linked to psychosis, treatment for trauma in psychotic disorders (PD) remains at the periphery of clinical practice (Ronconi, Shiner, & Watts, Citation2014), mainly because the dramatic manifestation of psychosis masks the intensity and severity of PT (van Minnen, Hendriks, & Olff, Citation2010). In fact, many therapists do not address traumatic experiences such as abuse while treating those with psychosis (Frueh, Cusack, & Grubaugh, Citation2006; Young, Read, & Barker-Collo, Citation2001) due to concerns regarding exacerbation of psychotic symptoms (Gairns, Alvarez‐Jimenez, & Hulbert, Citation2015; van den Berg, van der Vleugel, & de Bont, Citation2016; Young et al., Citation2001). Patients with PD are also frequently excluded from randomized clinical trials of trauma-focused interventions (TFI) (Becker, Zayfert, & Anderson, Citation2004; Ma & Weng, Citation2016; Mueser et al., Citation2002; van den Berg et al., Citation2016) and trauma-focused treatments (Ma & Weng, Citation2016; Meyer, Farrell, & Kemp, Citation2014; Neria et al., Citation2002; Olatunji, Cisler, & Tolin, Citation2010; van Minnen, Harned, & Zoellner, Citation2012; van Minnen, Zoellner, & Harned, Citation2015). This results in inadequate care protocols and the need for information on treatment approaches for PT among individuals with PD. (Mueser et al., Citation2002)

To achieve more parity in conceptualizations of trauma and guidelines for interventions, it is imperative to understand experiencers’ perspectives and what events they perceive to impact the onset, maintenance, and treatment of their psychotic experience. This will result in information on how PT might be a relevant factor preceeding psychosis; providing clinicians with perspectives on treatment needs. Further, considering patient perspectives on illnesses, treatment, and recovery while developing treatment protocols has been known to affect outcomes (Shay & Lafata, Citation2015). Therefore, to further inform clinical and research practices and to contribute to the debate on whether or not to address PT in psychosis, the present study aimed to understand patient perspectives on the impact of PT on their experience with PD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A qualitative exploratory design was used to understand patient perspectives on the impact and treatment of PT in PD. Considering the heterogeneity in illness manifestation and the corresponding subjective needs of patients, the study was designed to collect patient perspectives from individuals at varying stages of recovery. This, therefore, involved both semi-structured and structured interview methods. The semi-structured interview was used with participants who experience mild-moderate disability while the latter interview was conducted with participants experiencing florid psychotic symptoms including hallucinations, delusions and alogia (moderate to severe disability). This ensured equal and fair representation of the population irrespective of symptom severity.

2.2. Study sample

Participants (n = 20) were recruited at a not-for-profit, inpatient facility for homeless women with severe mental illness, that offers holistic care using a biopsychosocial approach. The organization’s mandate in working with homeless women with severe mental illnesses resulted in a fairly homogeneous group with recovery being the only relevant variable distinguishing potential participants. In order to effectively understand patient perspectives, it was imperative that a sample representative of the population’s disability/recovery was obtained. This was ensured through a maximum variation purposive sampling (Etikan, Musa, & Alkassim, Citation2016) method which allowed for recruiting of individuals at varying levels of recovery.

The in-patient database maintained by the facility was, therefore, scanned for individuals with a diagnosis of psychosis. The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Castillo, Carlat, Millon, Meagher, & Grossman, Citation2007) score was used to determine persons with varying disability and ensure appropriate inclusion; group 1 (n = 10) included participants who obtained a score of 54–80 (moderate-mild disability) and group 2 (n = 10) included participants who obtained a score of 41–57 (moderate to severe disability). Case managers of the patients were then asked to pick 20 participants who were capable of participating in the interviews from each group, meeting the inclusion criteria described below:

To be eligible for the study, all participants were required to have experienced homelessness and be diagnosed with a psychosis spectrum condition according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) (Castillo et al., Citation2007). It is also presumed that considering the homeless profile of the participants, chronic PT would be present. Individuals with a diagnosis of mental retardation and personality disorders were excluded from the study. Despite the knowledge that some personality disorders are closely related to PT, the differential nature of psychotic symptoms in personality disorders such as micropsychotic episodes in borderline personality and character-specific processing of traumatic experiences or NLEs was determined as beyond the purview of this study.

2.3. Procedure

On obtaining informed consent an interview that focused on meaning, signs, and perceived causes of PT, perceived causes of psychosis (mental illness), perpetuating factors of psychosis, perspectives on treatment and recovery were explored. As aforementioned, with group 1, the semi-structured interview schedule was used and with group 2, a brief version of the same schedule was used, to cater to the disability experienced, such as poor comprehension, alogia, and symptoms of psychosis.

Data were collected during July–August 2017 and was completed by the PI of this study, in the language preferred by the participant (Tamil or English). Each interview lasted 60–80 min and was audio-recorded. Interviews were conducted until data saturation was obtained in each group. This was determined by the study’s PI when no new learnings emerged from the data, causing subsequent interviews to become redundant. Further, to establish the reliability of responses triangulation of data was completed using case manager responses and patient records; any discrepancy was flagged off during analysis but did not affect the overall outcome of the interviews.

All participants were debriefed post the interviews. Positive visualization was used to ensure each participant would be able to cope with the recollection of NLEs and other distress. Any note of distress at the end of the interview was reported to the participant’s case manager and 48 h of observation was mandated. No incidences of note were reported at follow-up.

Data were later transcribed directly into English, irrespective of language the interview was conducted in; however, care was taken to ensure all the nuances of the local language were mentioned. This was done by writing the local terminology or reference in English script. Similarly, the PI went through each transcript adding in references to hand gestures and other relevant non-verbal cues to provide a complete picture and aid qualitative analysis. All transcripts were anonymized and none included the participant’s name. This was to circumvent the possibility of biases in the analysis since the PI was also a part of the treating team.

2.4. Data analysis

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) similar to that developed by (Smith, Jarman, & Osborn, Citation1999) was used. This method allowed for understanding the phenomenology of trauma as well as to extrapolate findings and theorize way forward. The analysis was completed in 2 phases:

2.4.1. Phase 1

Coding was completed using both inductive and deductive approaches. A coding framework was built to support the process. This focused on the types and causes of NLE, perpetuating factors, strategies used for coping, recovery ideas, perspectives on treatment and outcomes of NLE. Using this framework, an inductive line by line approach was used to complete coding using Dedoose (v 8.0.,) (Dedoose Version 8.0.35, Citation2018) and began after the first interview systematically, in between every three interviews completed, until data saturation was obtained. The primary analysis was completed by the PI and a codebook was developed. Further, in order to ensure the validity of codes, a blind coding of transcripts using only the coding framework, was also done by the second author and a third neutral researcher. Codes obtained by all three researchers were discussed and consensus on the application of codes was obtained.

2.4.2. Phase 2- theme development

Post coding of all transcripts, codes were assimilated manually, clustered and interpreted in three steps (see ). First, assimilation of parent codes was completed from the initial list code composite of 16 parent and 79 child codes. This resulted in 10 parent and 84 child codes (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Patton, Citation1990). Second, available codes were categorized and developed into themes resulting in eight superordinate themes. Lastly, an interpretative analysis (Castillo et al., Citation2007) approach was used, and themes obtained in step 2 were analysed using a reflexive approach with attention to psychological processes underlying responses. Psychopathology, theories of coping and trauma, sociocultural theories around access to knowledge and treatment were used as reference points. This resulted in the final 6 themes and 12 subordinate themes (Patton, Citation1990) (see ). This phase also led to observations of interrelatedness between themes developed that further strengthened outcomes.

The first and second authors of this study, both psychologists, then regrouped to discuss interpretations and to ensure no biases were involved in the process.

3. Results

3.1. Participant demographics

Two groups of participants leading up to a total of 20 interviews were obtained and analysed. Participants in either group were diagnosed with a psychosis spectrum condition according to the DSM-IV-TR (Castillo et al., Citation2007): schizophrenia (n = 9), schizoaffective disorder (n = 2), bipolar affective disorder type 1 (n = 3) or psychosis NOS (n = 6).

Group 1 included 10 female participants with moderate to a mild disability, as assessed using the GAF (54–80). This was assessed by the study’s PI who is also a member of the treating team. The mean age was 44.15 years (SD = 12.08) and based on information obtained from participants; they had been experiencing a PD for over 10 years. All participants were able to articulate and speak expansively about their experiences and were therefore interviewed using the aforementioned semi-structured interview schedule.

Group 2 included 10 female participants with moderate to severe disability (GAF 41–57). The mean age was 44.40 years (SD = 11.40). While precise years of illness are unknown, owing to the disability of this group, clinical judgement indicates a chronic course for at least 2–3 years. Despite the challenges that were anticipated with this group in eliciting responses, their perspectives were considered crucial to the study since various experiences unique to the group such as the acute presentation, treatment access, recent hospitalizations and other variables usually linked to recovery, course of illness, comorbidities and trauma exposure, were presumed to impact data and results. However, upon analysis, findings did not indicate a difference between the groups in their perception of PT and related consequences.

Participants from both groups were homeless and from different parts of Tamil Nadu, India; currently living and working within an organization that works for marginalized populations, particularly homeless women with severe mental illnesses. No systematic screening for PTSD was completed with participants of this study and therefore no determination could be made regarding how many had a formal diagnosis of PTSD; although all participants had experienced multiple NLEs (see ).

Table 1. Type of NLEs experienced by participants

3.2. Thematic outcomes

Twenty interviews were analysed. Findings revealed 6 superordinate and 12 subordinate themes: Causes of PT, Response to trauma, Coping strategies, Perspectives on treatment, Maintenance factors, and Perspectives on recovery were superordinate themes (see ). Loss seems to be a key feature in promoting the onset, maintenance, and treatment of psychosis. Most participants (90%) opined that they had experienced distress akin with trauma symptoms, but received no care for it which led to maintenance factors that promoted psychosis and impeded recovery. Each superordinate and subordinate theme is described in the section below.

3.2.1. Psychological trauma

Most participants (95%) reported that PT was a result of the losses they experienced post the event, and not the event itself, as popular knowledge suggests. Participants explicitly reported that events were manageable but the losses they experienced consequent to the event were traumatic. This suggests that loss is the pertinent factor to experiencing PT and the events itself are less consequential to its development. The former often resulted in cognitive distortions and heightened affective responses to other, unrelated situations. In addition, it seems like additive stressors deplete an individual’s resources to cope, often worsening the primary problem and leading to ‘spiral loss’ (one loss leading to another). This is illustrated in the quotes below:

“I can [forget] and move on thinking he has gone and it’s [sexual abuse] over, in the past … but I lost my studies and the age [it happened when I was so young] … I lost everything … it’s not that it happened but I lost everything” says a 45 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia, who reported that the loss she experienced as a result of CSA has contributed to many other significant events in her life.

“Yes ma’am … sometimes, even though so many years have passed, I feel very hurt and get angry and lash out when someone is … I don’t know … even shouts at me. It reminds me of all that I could have had if that man didn’t hurt me … ” reported 50 YO G diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, a victim of domestic violence, experienced institutionalisation after she lost her baby and ran away from home.

“It was bad … I mean first I lost my job, because I lost that I did not have money and when I didn’t have money I lost my home … and then my sister tortured me at her home, so I had to leave and I was on the streets … and then they put me in [institution] … I slowly kept losing everything, one-by-one … ” reported 56 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia, who discusses the experience of ‘spiral loss’ where one situation led to another.

3.2.2. Responses to PT

Results indicate that participants (85%) believe that traumatic loss led to the onset and maintenance of PD they experienced. In addition, symptoms consistent with depression such as preoccupation, worry, decreased appetite, and listlessness, were also reported as a response to PT, in addition to their experience of PD. The quotes below illustrate some representative responses:

“I would not eat, sleep or talk to anybody. I just sat quietly … I wouldn’t even comb my hair. I would just keep crying to myself [alone] … ” reports a 40 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia, shares her reaction to negative life experiences.

“Mental illness [refers to her PD] comes when someone is experiencing trauma … without trauma no mental illness can come … The mind is shocked … ” reports a 38 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia, who believes that mental illness is primarily caused by additive stressors.

“ … After that [multiple instances of PT] finally, the last was when I saw an accident of an old man. I thought it might be my father … I went home and then something happened … I don’t know what … later the doctor told my parents I have developed schizophrenia … ” reports a 42 YO, F diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

Coping strategies: Active behavioural and passive emotional strategies of coping were two significant styles for coping that emerged from the data among 50% and 80% of participants, respectively: active behavioural strategies such as reconciliation with the perpetrator, quarrelling, or religious methods such as visiting temples, and passive emotional or avoidant strategies such as ‘letting-be’, distraction, non-confrontation, avoidance, were often used to manage negative emotional states. From the triangulation of data it appears that these strategies were often rigid and inflexible to change, often resulting in only short periods of relief and sometimes led to resurfacing of traumatic memories.

56 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia reports how she managed traumatic stress and attained personal recovery. “Now it’s all better … I have reconciled with my sister … I reconciled with J as well. They all have troubled me but I have reconciled and moved on … ”

46 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia reports work as a tool to managing traumatic stress: “it will take a long time to recover … but best is to keep them [persons with trauma] occupied and doing something so they [persons with trauma] don’t think of it …

35 YO F diagnosed with Psychosis NOS, uses religious methods to distract herself and gain temporary relief from traumatic stress: “I just go to the church and come back … it will come [back to me] again, all that he did but then I just let it be … nothing can be done … ”

3.2.3. Maintenance factors

Factors that perpetuate distress/disorders are referred to as maintenance factors. In this study, it appears that cognitive schemas related to aloneness, womanhood, cognitive distortions (helplessness, unacceptance of the loss, sense of victimization) were noted in 70% of the participants and attenuated affective responses (guilt, frustration), stigma, and continued rejection were reported among 80% of participants as maintenance factors. In addition, resurfacing of traumatic memories was linked to ideas of loss and often resulted from loneliness, sadness and frustration often promoting symptoms associated with PD and depression as indicated by participants quoted below:

23 YO F diagnosed with Psychosis NOS, discusses the maintenance loop with her voices and experiencing continued rejection: “How long can I live alone? My family is not taking me back … I am so tired and crying all the time … fed up … these voices also are not stopping and talking nonsense … ”

69 YO F diagnosed with BPAD Type 1, discusses what was interpreted as her schema interplaying with her symptoms of depression: 'whatever it is a woman cannot live alone … at one point, they will need someone … [my husband beat me] but still a woman cannot sleep alone … I don’t know what to do … I cry all the time and I don’t feel like eating or sleeping. I am just stuck …'

3.2.4. Perspectives on treatment

Participants were aware of various forms of treatment and believed they require pharmacological as well as psychological interventions that focused on processing the experience of loss. They also described the need for social support and recreational activities to enhance recovery outcomes. However, most participants (80%) also reported that despite seeking various treatment options, they received no care for maintenance factors, often leading to resurfacing, relapses or exacerbations of the psychotic disorder, the remaining 20% of participants did not respond to the interview question. Participants believed this was key to managing psychosis and attaining personal recovery.

40 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia, reports a need for biopsychosocial treatment approaches: “[to get better] we will need counseling and medicines … people should understand and support us … take us out, to movie or temple or something … ”

42 YO F diagnosed with schizophrenia, discusses how resurfacing of loss can lead to her relapse: ‘ … sometimes when something happens at work, I will be reminded and think that I’ve ended up here [in this facility] and feel bad. That time I will start to feel low and cry … then if no one helps I will start getting bad thoughts like suspecting others and the staff and all … usually that’s how I relapse … ’

3.2.5. Recovery

Participants (100%) reported that recovery was obtained when they achieve(d) positive health outcomes such as absence of symptoms, physical health and psychosocial outcomes such as pursuing capabilities, enhanced interests in social mixing, and in one case confrontation with the perpetrator was also considered essential for recovery.

35 YO F diagnosed with Psychosis NOS, discusses how working hard and multitasking is a sign of wellness: “ … fully recovered means I will be able to work and take care of my children … I won’t feel tired always … by working in 2–3 houses [housekeeping] I can live … ”

45 YO F diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, reports that socializing and maintaining social relationship is a sign of wellness: ‘it’s not really about work or money … we should be able to go outside and meet new people … we should be able to interact well with everybody … ’

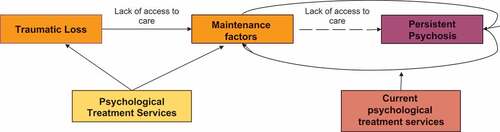

Further analysis indicated that the aforementioned themes were interrelated. In the situation of traumatic loss and lack of access to care, often maintenance factors such as cognitive distortions and attenuated affective responses are developed. In situations of continued lack of access to care, it appears that these maintenance factors are strengthened and contribute to persistent psychotic experiences. The latter leads to further losses such as loss of employment, loss of ontological needs and more; resulting in the further strengthening of the maintenance factors. It would, therefore, be important that psychological services are provided for the experience of traumatic loss and maintenance factors. However, current psychological treatments target psychotic manifestation and in some cases related to cognitive distortions (see ).

4. Discussion

The findings of this study revealed multiple interesting facts pertinent to the understanding of trauma and psychosis. First, despite the understanding that severity of psychosis is predicted by various sociocultural and psychosocial factors (Conus et al., Citation2017; Díaz-Caneja et al., Citation2015) including trauma exposure (Bailey et al., Citation2018), participants from group 2, assessed with more severe psychosis and associated disability, did not differ from group 1 in their perceptions of trauma and its link to their psychosis, indicating that the effect of trauma on severity of psychosis needs to be further investigated. The second crucial finding is that NLEs are appraised as loss which is experienced as PT and has a direct impact on the onset and maintenance of PD. This study has surprisingly found that contrary to popular notions indicating that events cause PT (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), participants of this study have opined that consequent losses post the event are in fact what results in PT and play a key role in the development, maintenance and treatment of their experience of PD often manifesting along with depressive symptoms. Similar results were obtained in relation to hallucinations as well (Vallath, Luhrmann, & Bunders, Citation2018).

The relation between NLEs and depression (Mandelli, Petrelli, & Serretti, Citation2015) and PD (McGrath, Saha, Lim, & Aguilar-Gaxiola, Citation2017) has been a critical conversant in literature for over a decade now. With advances in research, the notion of PTSD in psychosis became more prominent. Yet, the notions of PT including a broad array of stressful events, due to differential stress tolerance (Devylder et al., Citation2013) among individuals remain controversial. In arguing for the inclusion of NLEs and associated PT in clinical purview studies have found that cultural nuances play a key role in an individual’s appraisal of events being traumatic (Gilmoor, Vallath, Reeger, & Bunders, Citation2020). While many individuals exposed to ‘traumatic events’ may experience PTSD, many others such as those in this sample, present with similar, trauma-related symptoms that often do not reach clinical purview, independent of other related conditions (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [US], Citation2014). These symptoms such as sudden irritability or anger, feeling low, and anxiety are often misdiagnosed as a depressive disorder or anxiety disorder (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [US], Citation2014).

This notion of loss interplaying with traumatic events was observed by Hobfoll (Hobfoll, Dunahoo, & Monnier, Citation1995) in the Conservation of Resources model, which suggests that the experience of a NLE can threaten or create actual depletion of an individual’s resources to cope creates traumatic stress. The theory focuses on the notion that all stressful life events are in actuality ‘loss events’, and therefore gaining these resources back may help with recovery. This tenant explains why individuals who lose their job and experience spiral losses experience PT, but are able to recover when employment, housing and finances stabilize.

How NLEs impact individuals, cause PT and contribute to the development of PD: It appears that when an individual is exposed to a NLE, the individual appraises the event as loss which to the individual is PT. This loss, if untreated, festers over time, with cognitive distortions and heightened affective states resulting in further losses; which plays a critical role in the development of PD. Due to the dramatic manifestation that is PD, PT (arising from small-t experiences) receives less attention and is often left untreated. Other studies also indicate the possibility of underlying psychological processes playing a role in psychosis (Freeman, Dunn, & Startup, Citation2015; Vallath et al., Citation2018).

A second critical psychological process underlying PT involves coping. The term coping refers to conscious and unconscious ways of dealing with stress (Lazarus, Citation1996) and includes cognitive, behavioural and physiological reactions (Holubova, Prasko, & Hruby, Citation2015). While all coping mechanisms serve to be adaptive in protecting the individual, they vary in effect, for example, some work well for short-term problems while when applied to long-term problems they can become dysfunctional. Coping styles, however, eventually become a person’s trait (Lazarus, Citation2006). Adaptive coping mechanisms are flexible and efficient while maladaptive coping is rigid and sometimes socially inappropriate (Lazarus, Citation1996).

A key finding from this study was that coping mechanisms used by participants were limited to active behavioural and passive emotional strategies, the latter of which has been linked to paranoid symptoms of psychosis (Ritsner, Ben-Avi, & Ponizovsky, Citation2003). Participants in this study adopted emotion-focused coping strategies that were either active or passive but rarely adopted problem-solving strategies. Further, the strategies used were often rigid and applied without discretion to all problems, perhaps perpetuating psychotic symptoms. Consistent with this finding, literature also suggests that psychotic experiences are often attenuated when maladaptive coping strategies are used to manage traumatic life events and perceived stress (Ered, Gibson, & Maxwell, Citation2017; Horan & Blanchard, Citation2003; Moritz, Lüdtke, & Westermann, Citation2016). Similarly, in a longitudinal study, (Vázquez Pérez, Godoy-Izquierdo, & Godoy, Citation2013) found that better coping with stress led to a decrease in psychotic symptoms over a two-year period.

The need for a broad outlook to PT: As aforementioned, the concrete diagnosis-specific strategy to treating illnesses that is currently popular in mainstream psychiatry, results in a reductionist approach. While this article does not take away from the seriousness that is in PTSD, it aims to bring to light variegated NLEs that lead to the experience of PT, requiring equal clinical attention in treatment such as given to PTSD or PD. The role of PT in developing PD and PTSD has been discussed in detail in the introduction and results section of this paper. If an individual with PD has sudden bouts of irritability and aggression, clinicians must wonder whether PT has been a pertinent trigger to the behaviour. In fact, PT has been known to trigger fears of abandonment, love, anxieties about survival and can have adverse effects on long term well-being (Conus et al., Citation2017). Participants of this study also acknowledged that on many occasions this was overlooked and treatment was provided for psychotic manifestations only.

Untreated PT may result in permanent disability, medical and legal expenses, increased sick leave, loss of productivity, and continued psychological distress (Flannery, Citation1999).

4.1. Treatment approaches

Findings revealed a significant oversight in treatment approaches in psychosis for underlying psychological processes related to PT, impeding clinical, social, functional and personal recovery.

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Citation2014) many patients with PD continue to experience persistent and distressing positive and negative symptoms, and medications are only effective in 40% of cases. This supports findings from this study, where patients reported resurfacing or exacerbations of symptoms in the continued presence of maintenance factors. In fact, studies have indicated that individuals diagnosed with psychosis and past NLEs show higher rates of psychotic symptoms, comorbid disorders, cognitive deficits, frequent hospitalization and even treatment resistance, when compared to those with no NLEs present (Horan & Blanchard, Citation2003; Moritz et al., Citation2016).

Recent research has therefore begun looking into underlying factors in psychotic manifestations (Hassan & De Luca, Citation2015; Schenkel, Spaulding, & DiLillo, Citation2005). Given the relation between NLEs and PDs, many have advocated for the move towards trauma-focused interventions (TFIs) (De Bont et al., Citation2016; van den Berg et al., Citation2015) even for the prevention of PD. However, despite such growing evidence of the interlinkage between PT and PD, an illness paradigm is mostly used in treating problems linked to PDs and treatment is often biomedical. Even psychological therapies for psychosis aim at symptom reduction by focusing on its manifestations, such as hearing voices or delusional thinking.

Findings from this study suggest that treatment interventions are necessary for psychological processes such as loss underlying psychosis instead of only its manifestations and that patients with psychosis are also keen to avail such services but lack access. Patient reports suggested that therapies focusing on loss and associated feelings would perhaps alleviate distress and better coping with the psychotic experience. This is consistent with other studies. Patients with psychosis have reported that trauma-focused interventions have a positive effect on their well-being and symptom management (Bacon et al., Citation2014; Halpin, Kugathasan, & Hulbert, Citation2016; Keen, Hunter, & Peters, Citation2017; Tong, Simpson, & Alvarez-Jimenez, Citation2017).

4.2. The need to build an evidence base for PT and its impact on PDs

For a practice to move forward and advance recovery from PT, it is essential that future studies focus on the notion of PT and treatment models that benefit PT. Similarly, grounding the notion of PT from variegated NLEs may further advance treatment outcomes with practitioners being more cognizant of this while treating severe mental illnesses such as PD. In fact, many classical TFIs such as narrative exposure therapy (Shapiro & Forrest, Citation2004), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) (Shapiro & Forrest, Citation2004), are developed to combat trauma and PTSD (Schauer, Schauer, Neuner, & Elbert, Citation2011), however, with the notion of PTSD gaining prominence and strict criteria of trauma being defined, these forms of therapy became salient to use with PTSD only. In addition, other innovative methods such as art-based therapies are also used in the treatment of trauma (Fikreyesus, Soboka, & Feyissa, Citation2016).

5. Conclusions and implications

Various studies have noted that in PD symptoms are often difficult to manage, and even in cases of recovery relapse rates are as high as 24.6% (Tong et al., Citation2017). There is substantial evidence indicating the pertinent role of psychotherapies in treating severe mental illness. However, despite this evidence, only 10% of the population with PDs have access to psychotherapies (The Schizophrenia Commission, Citation2012). Presumably, access to specialist interventions such as psychological therapies and counselling is especially limited in low and middle-income countries (LMICs), and even more so for those from marginalized backgrounds like homeless persons such as the participants of this study. Findings from this study indicate that treatment must be personalized and individual care plans must be developed. This has been resonated in other studies as well (Kluft, Bloom, & Kinzie, Citation2000). It also reinforces the growing need for treatment of psychosis to also focus on underlying psychological processes of its manifestation. Policy must, therefore, mandate specialist interventions such as trauma-focused interventions in treatment protocols.

5.1. Limitations

The primary limitation of this study includes the retrospective accounts of participants. This was managed through triangulation of data by corroborating factors with treating professionals and case files. Another limitation includes the nature of participants. All participants had a history of homelessness. This understudied and niche population may be unique in terms of experiences. Generalization of results, therefore, may require further study. Lastly, participants in this study were not screened systematically for PTSD at the time of their contact with treatment services, or during this research. While clinical notes suggest that traditional symptoms of PTSD were not present, it is unsure if there has been an oversight in diagnosing PTSD as a comorbidity. However, the authors of this study do not believe that this influences the results obtained since the aim was to understand trauma and its role in psychosis; a formal diagnosis of PTSD was inconsequential.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all clients and staff at the organisation of study for their inputs and cooperation in data collection. The author also thanks Mr Andrew R. Gilmoor, department of earth and life sciences, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, for assisting in data analysis and coding transcripts as well as Mr Srihari Swamy, intern, for assisting the PI in some parts of the data collection process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Bacon, T., Farhall, J., & Fossey, E. (2014). The active therapeutic processes of acceptance and commitment therapy for persistent symptoms of psychosis: Clients’ perspectives. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 42(4), 402–12.

- Bailey, T., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Garcia-Sanchez, A. M., Hulbert, C., Barlow, E., & Bendall, S. (2018). Childhood trauma is associated with severity of hallucinations and delusions in psychotic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(5), 1111–1122.

- Becker, C. B., Zayfert, C., & Anderson, E. (2004). A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42(3), 277–292.

- Bendall, S., Alvarez‐Jimenez, M., & Nelson, B. (2013). Childhood trauma and psychosis: New perspectives on aetiology and treatment. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 7(1), 1–4.

- Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., … Alonso, J. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: Results from the world mental health survey consortium. Psychological Medicine, 46(2), 327–343.

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Brown, R. C., Berenz, E. C., Aggen, S. H., Gardner, C. O., Knudsen, G. P., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., … & Amstadter, A. B. (2014). Trauma exposure and Axis I psychopathology: A cotwin control analysis in Norwegian young adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 6(6), 652.

- Castillo, R. J., Carlat, D. J., Millon, T., Meagher, S., & Grossman, S., & American Psychiatric Association. (2007). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US). (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57.) Chapter 3, Understanding the Impact of Trauma.

- Conus, P., Cotton, S. M., Francey, S. M., O’Donoghue, B., Schimmelmann, B. G., McGorry, P. D., & Lambert, M. (2017). Predictors of favourable outcome in young people with a first episode psychosis without antipsychotic medication. Schizophrenia Research, 185, 130–136.

- De Bont, P. A., Van Den Berg, D. P., Van Der Vleugel, B. M., de Roos, C. J. A. M., De Jongh, A., Van Der Gaag, M., & van Minnen, A. M. (2016). Prolonged exposure and EMDR for PTSD v. a PTSD waiting-list condition: Effects on symptoms of psychosis, depression and social functioning in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Psychological Medicine, 46(11), 2411–2421.

- Dedoose Version 8.0.35. (2018). Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, CA: Sociocultural Research Consultants, LLC. Retrieved from www.dedoose.com.

- Devylder, J. E., Ben-David, S., Schobel, S. A., Kimhy, D., Malaspina, D., & Corcoran, C. M. (2013). Temporal association of stress sensitivity and symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Psychological Medicine, 43(2), 259–268.

- Díaz-Caneja, C. M., Pina-Camacho, L., Rodríguez-Quiroga, A., Fraguas, D., Parellada, M., & Arango, C. (2015). Predictors of outcome in early-onset psychosis: A systematic review. npj Schizophrenia, 1, 14005.

- Ered, A., Gibson, L. E., & Maxwell, S. D. (2017). Coping as a mediator of stress and psychotic-like experiences. European Psychiatry, 43, 9–13.

- Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4.

- Fikreyesus, M., Soboka, M., & Feyissa, G. T. (2016). Psychotic relapse and associated factors among patients attending health services in Southwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 354.

- Flannery, R. B. (1999). Psychological trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health, 1(2), 135–140.

- Freeman, D., Dunn, G., & Startup, H. (2015). Effects of cognitive behaviour therapy for worry on persecutory delusions in patients with psychosis (WIT): A parallel, single-blind, randomised controlled trial with a mediation analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(4), 305–313.

- Frueh, B. C., Cusack, K. J., & Grubaugh, A. L. (2006). Clinicians’ perspectives on cognitive-behavioral treatment for PTSD among persons with severe mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 57(7), 1027–1031.

- Gairns, S., Alvarez‐Jimenez, M., & Hulbert, C. (2015). Perceptions of clinicians treating young people with first‐episode psychosis for post‐traumatic stress disorder. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 9(1), 12–20.

- Gilmoor, A. R., Vallath, S., Reeger, B., & Bunders, J. F. G. (2020). ‘If somebody could just understand what I am going through, it can make all the difference’: Conceptualizations of trauma in homeless populations experiencing severe mental illness. Transcultural Psychiatry, 1–13.

- Halpin, E., Kugathasan, V., & Hulbert, C. (2016). Case formulation in young people with post-traumatic stress disorder and first-episode psychosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 5(11), 106.

- Hassan, A. N., & De Luca, V. (2015). The effect of lifetime adversities on resistance to antipsychotic treatment in schizophrenia patients. Schizophrenia Research, 161(2–3), 496–500.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Dunahoo, C. A., & Monnier, J. (1995). Conservation of resources and traumatic stress. In Traumatic stress (pp. 29–47). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Holubova, M., Prasko, J., & Hruby, R. (2015). Coping strategies and quality of life in schizophrenia: Cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 3041.

- Horan, W. P., & Blanchard, J. J. (2003). Emotional responses to psychosocial stress in schizophrenia: The role of individual differences in affective traits and coping. Schizophrenia Research, 60(2), 271–283.

- Keen, N., Hunter, E., & Peters, E. (2017). Integrated trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy for post-traumatic stress and psychotic symptoms: A case-series study using imaginal reprocessing strategies. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 92.

- Kessler, R. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Cardoso, G., … & Florescu, S. (2017). Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup5), 1353383.

- Kluft, R. P., Bloom, S. L., & Kinzie, J. D. (2000). Treating traumatized patients and victims of violence. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 86, 79–102.

- Lazarus, R. (1996). Psychological stress and the coping process. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Lazarus, R. S. (2006). Stress and emotion. A new synthesis. New York: Springer.

- Ma, H., & Weng, C. (2016). Identification of questionable exclusion criteria in mental disorder clinical trials using a medical encyclopedia. Biocomputing 2016: Proceedings of the Pacific Symposium, Hawaii, United States.

- Mandelli, L., Petrelli, C., & Serretti, A. (2015). The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 665–680.

- McGrath, J. J., Saha, S., Lim, C. C., & Aguilar-Gaxiola, S. (2017). Trauma and psychotic experiences: Transnational data from the world mental health survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(6), 373–380.

- McGrath, J. J., Saha, S., Lim, C. C., McGrath, J. J., Saha, S., Lim, C. C., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., Andrade, L. H., … & De Girolamo, G. (2017). Trauma and psychotic experiences: Transnational data from the world mental health survey. British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(6), 373–380.

- McLafferty, M., Armour, C., & O’Neill, S. (2016). Suicidality and profiles of childhood adversities, conflict related trauma and psychopathology in the Northern Ireland population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 97–102.

- Meyer, J. M., Farrell, N. R., & Kemp, J. J. (2014). Why do clinicians exclude anxious clients from exposure therapy? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 54, 49–53.

- Moritz, S., Lüdtke, T., & Westermann, S. (2016). Dysfunctional coping with stress in psychosis. An investigation with the maladaptive and adaptive coping styles (MAX) questionnaire. Schizophrenia Research, 175(1–3), 129–135.

- Moriyama, T. S., Drukker, M., Gadelha, A., Pan, P. M., Salum, G. A., Manfro, G. G., … & Van Os, J. (2018). The association between psychotic experiences and traumatic life events: The role of the intention to harm. Psychological Medicine, 48(13), 2235–2246.

- Mueser, K. T., Rosenberg, S. D., & Goodman, L. A. (2002). Trauma, PTSD, and the course of severe mental illness: An interactive model. Schizophrenia Research, 53(1–2), 123–143.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2014). Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: Treatment and management (CG178). London: Author.

- Neria, Y., Bromet, E. J., & Sievers, S. (2002). Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in psychosis: Findings from a first-admission cohort. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(1), 246.

- Okkels, N., Trabjerg, B., & Arendt, M. (2016). Traumatic stress disorders and risk of subsequent schizophrenia spectrum disorder or bipolar disorder: A nationwide cohort study. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 43(1), 180–186.

- Olatunji, B. O., Cisler, J. M., & Tolin, D. F. (2010). A meta-analysis of the influence of comorbidity on treatment outcome in the anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 642–654.

- Patton, M. Q. (1990). Humanistic psychology and humanistic research. Person-Centered Review, 5(2), 191–202.

- Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. (1995). Trauma and the therapist. New York: Norton.

- Ritsner, M., Ben-Avi, I., & Ponizovsky, A. (2003). Quality of life and coping with schizophrenia symptoms. Quality of Life Research, 12(1), 1–9.

- Ronconi, J. M., Shiner, B., & Watts, B. V. (2014). Inclusion and exclusion criteria in randomized controlled trials of psychotherapy for PTSD. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 20(1), 25–37.

- Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., & Goodwin, R. D. (2005). Co‐occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder with positive psychotic symptoms in a nationally representative sample. Journal of Traumatic Stress: Official Publication of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 18(4), 313–322.

- Schauer, M., Schauer, M., Neuner, F., & Elbert, T. (2011). Narrative exposure therapy: A short-term treatment for traumatic stress disorders. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe Publishing.

- Schenkel, L. S., Spaulding, W. D., & DiLillo, D. (2005). Histories of childhood maltreatment in schizophrenia: Relationships with premorbid functioning, symptomatology, and cognitive deficits. Schizophrenia Research, 76(2–3), 273–286.

- Shapiro, F. (Ed.). (2002). EMDR as an integrative psychotherapy approach: Experts of diverse orientations explore the paradigm prism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Shapiro, F., & Forrest, M. (2004). EMDR: The breakthrough “eye movement” therapy for overcoming anxiety, stress, and trauma. New York: Basic Books.

- Shay, L. A., & Lafata, J. E. (2015). Where is the evidence? A systematic review of shared decision making and patient outcomes. Medical Decision Making, 35(1), 114–131.

- Smith, J. A., Jarman, M., & Osborn, M. (1999). Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. In Qualitative health psychology: Theories and methods (pp. 218–240).

- The Schizophrenia Commission. (2012). The abandoned illness: A report from the schizophrenia commission. London: Rethink Mental Illness.

- Thomson, K., Randall, E., & Ibeziako, P. (2014). Somatoform disorders and trauma in medically-admitted children, adolescents, and young adults: Prevalence rates and psychosocial characteristics. Psychosomatics, 55(6), 630–639.

- Tong, J., Simpson, K., & Alvarez-Jimenez, M. (2017). Distress, psychotic symptom exacerbation, and relief in reaction to talking about trauma in the context of beneficial trauma therapy: Perspectives from young people with post-traumatic stress disorder and first episode psychosis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 45(6), 561–576.

- Vallath, S., Luhrmann, T., & Bunders, J. (2018). Reliving, replaying lived experiences through auditory verbal hallucinations: Implications on theories and management. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9.

- van den Berg, D. P., de Bont, P. A., van der Vleugel, B. M., de Roos, C., de Jongh, A., Van Minnen, A., & van der Gaag, M. (2015). Prolonged exposure vs eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs waiting list for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with a psychotic disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry (Chicago, Ill.), 72(3), 259–267.

- van den Berg, D. P., van der Vleugel, B. M., & de Bont, P. A. (2016). Exposing therapists to trauma-focused treatment in psychosis: Effects on credibility, expected burden, and harm expectancies. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 31712.

- van Minnen, A., Harned, M. S., & Zoellner, L. (2012, Dec 1). Examining potential contraindications for prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(1), 18805.

- van Minnen, A., Hendriks, L., & Olff, M. (2010). When do trauma experts choose exposure therapy for PTSD patients? A controlled study of therapist and patient factors. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(4), 312–320.

- van Minnen, A., Zoellner, L. A., & Harned, M. S. (2015). Changes in comorbid conditions after prolonged exposure for PTSD: A literature review. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(3), 17.

- Varese, F., Smeets, F., Drukker, M., Lieverse, R., Lataster, T., Viechtbauer, W., … & Bentall, R. P. (2012). Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: A meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective-and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38(4), 661–671.

- Vázquez Pérez, M. L., Godoy-Izquierdo, D., & Godoy, J. F. (2013, Mar 1). Clinical outcomes of a coping with stress training program among patients suffering from schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: A pilot study. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 26(2), 154–170.

- Young, M., Read, J., & Barker-Collo, S. (2001). Evaluating and overcoming barriers to taking abuse histories. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 32(4), 407.