ABSTRACT

Background: Moral injury is a relatively new field within psychotraumatology that focuses on understanding and treating psychosocial symptoms after exposure to potentially morally injurious events (PMIE’s). There are currently three models of the development of moral injury which centre around the influence of attributions, coping and exposure. While the capacity for empathy is known to underlie moral behaviour, current models for moral injury do not explicitly include empathy-related factors.

Objective: This paper aims to make a case for complementing current models of the development of moral injury with the perception-action model of empathy (PAM).

Method: In this paper, the perception-action mechanism of empathy and the empathic behaviour that it may initiate, are described. The PAM states that perception of another person’s emotional state activates the observer’s own representations of that state. This forms the basis for empathic behaviour, such as helping, by which an observer tries to alleviate both another person’s and their own, empathic, distress. In this paper it is proposed that in PMIE’s, empathic or moral behaviour is expected but not, or not successfully, performed, and consequently distress is not alleviated. Factors known to influence the empathic response, including attention, emotion-regulation, familiarity and similarity, are hypothesized to also influence the development of moral injury.

Results: Two cases are discussed which illustrate how factors involved in the PAM may help explain the development of moral injury.

Conclusions: As empathy forms the basis for moral behaviour, empathy-related factors are likely to influence the development of moral injury. Research will have to show whether this hypothesis holds true in actual practice.

HIGHLIGHTS

• People who have been involved in harmful acts that they feel were morally wrong, may suffer from psychosocial symptoms known as moral injury.• It is proposed that moral injury may be developed when during or after a transgressive act, a person feels great empathy towards a victim.

Antecedentes: El daño moral es un área relativamente nueva dentro de la psicotraumatología que se centra en la comprensión y el tratamiento de los síntomas psicosociales después de la exposición a eventos potenciales de daño moral (PMIE, en sus siglas en inglés). Actualmente hay tres modelos de desarrollo del daño moral que se centran en la influencia de las atribuciones, el afrontamiento y la exposición. Mientras que se sabe que la capacidad de empatía subyace en la conducta moral, los modelos actuales de daño moral no incluyen explícitamente factores relacionados con la empatía.

Objetivo: El presente documento tiene por objetivo presentar un caso para complementar los modelos actuales de desarrollo de daño moral con el modelo de percepción-acción de la empatía (PAM, en sus siglas en inglés).

Método: En este artículo se describe el mecanismo de percepción-acción de la empatía y la conducta empática que puede iniciar. El PAM establece que la percepción del estado emocional de otra persona activa las propias representaciones del observador de ese estado. Esto forma la base de la conducta empática, como la ayuda, por la cual un observador trata de aliviar empáticamente tanto el sufrimiento de otra persona como el suyo propio. En este artículo se propone que en el PMIE se espera una conducta empática o moral pero no se realiza, o no se realiza con éxito, y por consiguiente no se alivia la angustia. Se formula la hipótesis de que los factores que se sabe que influyen en la respuesta empática, incluyendo la atención, la regulación de las emociones, la familiaridad y la similitud, también influyen en el desarrollo del daño moral.

Resultados: Se discuten dos casos que ilustran cómo los factores involucrados en el PAM pueden ayudar a explicar el desarrollo del daño moral.

Conclusión: Como la empatía es la base de la conducta moral, es probable que los factores relacionados con la empatía influyan en el desarrollo del daño moral. La investigación tendrá que demostrar si esta hipótesis es válida en la práctica real.

背景: 道德创伤是心理创伤学中一个相对较新的领域, 重点关注暴露于潜在道德创伤事件 (PMIE) 后理解和治疗社会心理症状。当前存在三种围绕归因, 应对和暴露影响的道德创伤发展的模型。虽然共情能力是道德行为的基础, 但目前的道德创伤模型并未明确将共情相关因素纳入。

目的: 本文旨在为将共情知觉-行动模型 (PAM) 补充到当前道德创伤发展模型提供依据。

方法: 在本文中, 描述了共情知觉-行为机制及其可能引发的共情行为。PAM指出, 对他人情绪状态的感知会激活观察者自身对该状态的表达。这构成了共情行为 (例如帮助) 的基础, 观察者试图通过这种行为来减轻对方和自己的共情痛苦。本文提出, 在PMIE中, 共情或道德行为会预期出现, 但无法执行或未成功执行, 因此不能减轻痛苦。已知的影响共情反应的因素, 包括注意力, 情绪调节, 熟悉度和相似性, 也会影响道德创伤的发展。

结果: 讨论了两个案例, 说明了PAM中涉及的因素也许可以帮助解释道德创伤的发展。

结论: 由于共情构成道德行为的基础, 所以共情相关因素可能会影响道德创伤的发展。研究将必须证明该假设在实际中是否成立。

In recent years, increasing attention has been dedicated to understanding and treating psychological symptoms related to committing or failing to prevent high-impact moral transgressions, known as moral injury (Shay, Citation1994). The concept refers to moral suffering such as that of a Dutch lieutenant who watched how Muslim men were separated from their families in Srebrenica, 2001, and who later learned they were all killed. ‘It still gets to me,’ he asserts, ‘good didn’t exist there, all I could do was wrong’ (Nauta, Te Brake, & Raaijmakers, Citation2019, p. 75; translation by author).

Moral injury has been defined as ‘the lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact of perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations’ (Litz et al., Citation2009). The main elements in this definition are moral beliefs and expectations, which are based on the spoken and unspoken, personal and shared rules of social behaviour (Litz et al., Citation2009); transgressive acts that – in a military context – may involve, for example, killing of combatants and non-combatants, witnessing brutality towards civilians, or witnessing atrocities (Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016); and the impact of transgressions, which may become manifest in symptoms such as depression and destructive behaviours, interpersonal conflicts and social problems, religious or spiritual distress, and stress-related illness (Griffin et al., Citation2019). Originating primarily from a military context (Griffin et al., Citation2019), more recently the field of moral injury has widened to understanding the impact of moral transgressions in non-military populations such as refugees (e.g. Hoffman, Liddell, Bryant, & Nickerson, Citation2019).

The field of moral injury is relatively new and great effort is still being put into conceptualizing both moral transgressions and moral injury and developing models of how one may lead to the other (Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016; Griffin et al., Citation2019). Research of moral injury focuses on topics such as the definition, prevalence and predictors of transgressive acts or potentially morally injurious experiences (PMIE’s); the influence of moral transgressions on psychological, social, spiritual and physical functioning; the overlap of moral injury and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013); and effectiveness of interventions to alleviate moral injury (Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016; Griffin et al., Citation2019). Existing models of the development of moral injury form the basis for this research, but with the theory and study of moral injury still in its infancy, there is room for further development. In this paper, the idea is put forward that existing models of moral injury may be complemented by principles derived from the perception-action model of empathy (PAM; De Waal & Preston, Citation2017).

1. Morality and empathy

There are currently three models of the development of moral injury. According to the working causal framework by Litz et al. (Citation2009), involvement in a PMIE may cause emotional and cognitive dissonance. When a person tries to resolve this dissonance through making negative, stable, internal, global attributions, such as ‘I am evil’, a circle of moral injury symptoms is set in motion which includes shame and guilt, social withdrawal, self-condemnation, PTSD-like symptoms and self-harming behaviours. Neuroticism and shame-proneness are posited to be predictors both of dissonance and negative attributions, while belief in a just world, forgiving supports and self-esteem are suggested to be protective factors. In the functional-contextual model by Farnsworth, Drescher, Evans, and Walser (Citation2017), involvement in a PMIE may lead to dysphoric moral emotions and cognitions described as moral pain. Moral pain is perceived as a natural and non-pathological response to PMIE’s, which may lead to moral injury when dealt with in a maladaptive manner. Last, Nash’s Stress Injury Model of Moral Injury (Citation2019) states that when repeated or severe moral stress exceeds a person’s capacity to cope, physical and intrapsychic damage may occur. Moral injury occurs when moral stress reactions are irreversible despite adequate rest.

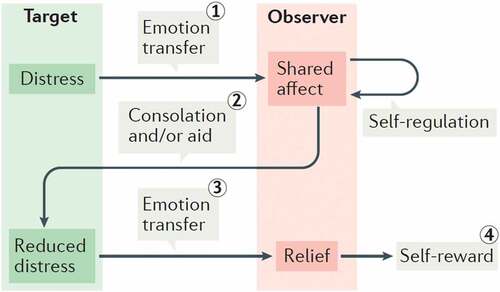

While these three models depict how moral injury may occur after one person gets wrongfully harmed by another, the factors involved in these models are predominantly individual rather than interpersonal – except for the forgiving supports mentioned in the model by Litz and colleagues. In this paper it is proposed that factors related to empathic processes, occurring between and within individuals, may help refine existing models of moral injury. Morally injurious events are, by their very nature, experiences of interpersonal trauma: one person is harmed by another or not (successfully) protected by another, resulting in significant harm or loss. As stated before, the morally ‘right’ behaviour that is expected in those situations is based on implicit and explicit rules, both personal and shared, of how people relate to one another (Litz et al., Citation2009). At the basis of these rules and the associated moral emotions and behaviour lies the capacity for empathy (De Waal, Citation2009). Empathy may be defined as ‘emotional and mental sensitivity to another’s state, from being affected by and sharing in this state to assessing the reasons for it and adopting the other’s point of view’ (De Waal & Preston, Citation2017, p. 498). This definition includes both affective empathy and cognitive empathy, which are seen as functionally integrated. According to the perception-action model of empathy (PAM; De Waal & Preston, Citation2017), perception of another person’s emotional state activates the observer’s own representations of that state, with representation being defined as ‘a pattern of activation in the brain and body corresponding to a particular state so repeated instances of the same event reliably activate the same pattern’ (Preston, Citation2007, p. 430). Empathy may lead to empathic behaviour, such as helping or consolation (also known as altruism), through a four-step process (see ).

Figure 1. From affect transfer to altruism

First, the emotional distress of person A (the ‘target’) is transferred to person B (the ‘observer’), resulting in shared affect; second, B, after regulating his or her own emotional response, attempts to help A; third, the reduced distress of A is again transferred to B; which, fourth, results in a self-rewarding of B’s empathic response. While the ability to show an empathic response may be universal, levels of empathic activation may vary depending on factors such as how much attention B pays to A, the emotion-regulation capacity of B, and familiarity and similarity between A and B (i.e. how close they are to one another and how alike). Empathic activation in B may also be overridden when empathic behaviour would interfere with B’s goals of survival, for example when B is engaged in a fight with A (De Waal & Preston, Citation2017).

2. Using the PAM to understand moral injury

The accuracy of the PAM has been demonstrated in numerous studies (De Waal & Preston, Citation2017). In this paper, it is proposed that the PAM may also help explain the development of moral injury. As stated, empathic activation lies at the basis of moral behaviour, such as helping or consolation, through a process of emotion transfer. This process may go awry during transgressive acts or PMIE’s. During PMIE’s, empathic, morally ‘right’ behaviour is expected but not, or not successfully, performed, and the distress of both parties involved is not ameliorated. For example, situations of severe emotional stress may lead to acts of perpetration (such as going ‘berserk’ after losing a comrade; Shay, Citation1994) in which the empathic response is overridden and another person is harmed (commission); or a person may be empathic and motivated to help someone in distress but may be prevented from doing so because the situation is beyond their control (omission).

Using the PAM to understand the development of moral injury, several hypotheses may be made. Specifically, it may be hypothesized that when during a PMIE levels of attention of B, familiarity and similarity between A and B, and desire to perform empathic behaviour in B are high, and emotion-regulation skills and amelioration of distress in B is low, the perception-action mechanism remains activated in brain and body and B is at risk of developing moral injury. In other words, it may be hypothesized that individuals who are most at risk of developing moral injury are those who (1) have a high exposure to a victim’s facial or bodily expressions of distress, (2) feel personally connected to the victim because they know the person or someone like them, or are similar to them in variables such as gender, age or race, (3) experience great distress and desire to help the victim, but (4) are prevented from or fail in helpful or respectful behaviour, resulting in significant harm to the victim. This may also be the case in individuals in whom empathy is initially suppressed because of conflicting goals (such as in armed conflict) but restored at a later point, which might explain cases of moral injury with delayed onset. Although in the definition of empathy by De Waal and Preston affective empathy and cognitive empathy are functionally integrated, direct exposure to a victim’s distress is likely to arouse a higher level of affective empathy, which then is likely to lead to higher levels of moral distress than situations in which empathy is predominantly cognitive.

It is proposed that when the perception-action mechanism remains activated, the mind and body continue to seek moral closure: individuals may continue to experience intrusive images of the victim’s distress, which evoke strong negative moral emotions such as guilt and shame, and a persistent desire to correct past wrongs so that the distress may be ameliorated. When the desired outcome cannot be achieved, they may resort to numbing and avoidance. They are, so to speak, stuck in the PAM.

3. Case illustrations

The mechanisms described above may be illustrated using two cases: one of commission and one of omission. First, in his war memoirs, Paul Steinberg, a Jewish writer who as a young man was imprisoned in Auschwitz, writes how in exasperation, he struck an elderly Jew:

“Furious, I raise my hand without thinking and slap him. At the last moment, I hold back and my hand just grazes his cheek. I see his eyes. Eyes brimming with exhaustion, with disgust at himself and his fellowman. And perhaps all this is sheer invention. Perhaps it was merely the image of what I had been some eight months earlier. Then I walked away, and that incident, a banal event in the daily life of a death camp, has haunted me all my life. In that world of violence I’d made a gesture of violence, thus proving that I had taken my proper place there. The elderly Polish Jew must have died during the days that followed, and ever since I have carried him inside me like an embryo. The memory of my action torments me still. It remains one of the abject wounds that can never heal.” (Steinberg, Citation2000, p. 126)

Steinberg relates how he initially acts without empathy (he slaps the man’s cheek) but then his empathy is restored in a moment of great attentiveness (watching the man’s eyes and sensing his exhaustion and disgust). In fact, he and the Polish Jew are so similar that he has difficulty telling their feelings apart (it might have been an image of what he himself had been). Blaming himself for causing the man pain (he had taken his proper place in that world of violence), the empathic image of the elderly Jew keeps intruding (he carried him inside him like an embryo) as part of his moral injury (the abject wounds that can never heal).

Second, in a book on professional moral dilemmas, a soldier stationed in Afghanistan shares her memory of a 10-year-old boy she failed to protect:

“He wore his own little police uniform, he had henna on his nails. During the meetings he constantly sat next to the fat old police commander, like a living trophy. The interpreter told me they slept together. I found reasons to not have to do anything about it: because it is their culture, because it undermines the relationship. I parked the boy somewhere in the back of my head. That changed when I had my first daughter in 2013. After her birth I realized how vulnerable children are, and how dependent on the protection of adults. It made me realize how serious the situation with the boy really was. The boy keeps haunting me, especially because he was so young.” (Nauta et al., Citation2019, pp. 28–30; translation by author)

This example illustrates how, although she pays great attention to the boy, the soldier initially suppresses her empathic response (she parks the boy in the back of her head) because protecting the boy conflicts with her goals (working with the Afghan police officer). Not having been directly exposed to the boy’s suffering, her empathic response appears mainly cognitive. However, empathy resurfaces at a later point and with a higher level of affect when similarity increases (after the birth of her daughter) and empathic images keep intruding (the boy keeps haunting her). In fact, in this case the soldier’s desire to protect children became so strong that she later adopted her second child, thus achieving some moral closure.

4. Discussion and conclusion

The pain experienced by individuals who suffer from moral injury confronts us with the fact that we are, at the core, empathic and moral beings, to whom living in a just world may be as important as living in a safe world. Factors related to empathic processes may add to current models that attempt to explain how negative attributions of transgressive acts, maladaptive attempts to cope with moral pain, and severe or repeated exposure to moral stressors contribute to the development of moral injury.

In this paper it is proposed that strong feelings of empathy during or after a transgressive act in which another person is harmed, may result in continued empathic distress and a continued desire to right past wrongs. However, just as empathy does not always lead to morally right behaviour, nor is morally right behaviour always motivated by empathy (De Waal & Preston, 201). It remains to be seen whether empathy is a prerequisite for developing moral injury or whether moral injury may also be developed based on transgression of core moral values alone. In addition, it has been shown that empathic responses in traumatized individuals may actually be dimmed rather than heightened (Maercker & Horn, Citation2013). This suggests that the relationship between empathy and moral injury may not be as straightforward as hypothesized in this paper.

In conclusion, research will have to show whether the hypotheses put forward in this paper hold true in actual practice. If so, empathy might not only be key in the development of moral injury but also in healing from moral injury: by expressing empathy and regret, both in real life or imaginary, towards those who were harmed; by receiving empathy when sharing feelings of guilt and sadness over actions taken and people lost; by fostering self-empathy and self-forgiveness; and by living a life of empathy and renewed connection (Evans, Walser, Drescher, & Farnsworth, Citation2020; Litz, Lebowitz, Gray, & Nash, Citation2017; Sherman, Citation2015). Empathy, perhaps, might be both cause of and cure for moral wounds.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Mirjam Nijdam, PhD, and Stephanie Preston, PhD, for commenting on an earlier version of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable for this manuscript since no new data were created or analysed.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- De Waal, F. (2009). The age of empathy: Nature’s lessons for a kinder society. Harmony Books.

- De Waal, F. B. M., & Preston, S. D. (2017). Mammalian empathy: Behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nature, 18, 498–5.

- Evans, W. R., Walser, R. D., Drescher, K. D., & Farnsworth, J. K. (2020). The moral injury workbook: Acceptance & Commitment Therapy skills for moving beyond shame, anger & trauma to reclaim your values. New Harbinger Publications.

- Farnsworth, J. K., Drescher, K. D., Evans, W., & Walser, R. D. (2017). A functional approach to understanding and treating military-related moral injury. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(4), 391–397.

- Frankfurt, S., & Frazier, P. (2016). A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Military Psychology, 28(5), 318–330.

- Griffin, B. J., Purcell, N., Burkman, K., Litz, B. T., Bryan, C. J., Schmitz, M., … Maguen, S. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 350–362.

- Hoffman, J., Liddell, B., Bryant, R. A., & Nickerson, A. (2019). A latent profile analysis of moral injury appraisals in refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1686805.

- Litz, B. T., Lebowitz, L., Gray, M. J., & Nash, W. P. (2017). Adaptive disclosure: A new treatment for military trauma, loss, and moral injury. Guilford.

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706.

- Maercker, A., & Horn, A. B. (2013). A socio-interpersonal perspective on PTSD: The case for environments and interpersonal processes. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 20(6), 465–481.

- Nash, W. P. (2019). Commentary on the special issue on moral injury: Unpacking two models for understanding moral injury. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 465–470.

- Nauta, B., Te Brake, H., & Raaijmakers, I. (2019). Dat ene dilemma: Persoonlijke verhalen over morele keuzes op de werkvloer [That one dilemma: Personal stories of moral choices at work]. Amsterdam University Press.

- Preston, S. D. (2007). A perception-action model for empathy. In T. Farrow & P. Woodruff (Eds.), Empathy in mental illness (pp. 428–447). Cambridge University Press.

- Shay, J. (1994). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. Scribner.

- Sherman, N. (2015). Afterwar: Healing the moral wounds of our soldiers. Oxford University Press.

- Steinberg, P. (2000). Speak you also: A survivor’s reckoning. Henry Holt and Company.