ABSTRACT

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic exposes individuals to multiple stressors, such as quarantine, physical distancing, job loss, risk of infection, and loss of loved ones. Such a complex array of stressors potentially lead to symptoms of adjustment disorder.

Objective: This cross-sectional exploratory study examined relationships between risk and protective factors, stressors, and symptoms of adjustment disorder during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods: Data from the first wave of the European Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS) longitudinal ADJUST Study were used. N = 15,563 participants aged 18 years and above were recruited in eleven countries (Austria, Croatia, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, and Sweden) from June to November 2020. Associations between risk and protective factors (e.g. gender, diagnosis of a mental health disorder), stressors (e.g. fear of infection, restricted face-to-face contact), and symptoms of adjustment disorder (ADNM-8) were examined using multivariate linear regression.

Results: The prevalence of self-reported probable adjustment disorder was 18.2%. Risk factors associated with higher levels of symptoms of adjustment disorder were female gender, older age, being at risk for severe COVID-19 illness, poorer general health status, current or previous trauma exposure, a current or previous mental health disorder, and longer exposure to COVID-19 news. Protective factors related to lower levels of symptoms of adjustment disorder were higher income, being retired, and having more face-to-face contact with loved ones or friends. Pandemic-related stressors associated with higher levels of symptoms of adjustment disorder included fear of infection, governmental crisis management, restricted social contact, work-related problems, restricted activity, and difficult housing conditions.

Conclusions: We identified stressors, risk, and protective factors that may help identify individuals at higher risk for adjustment disorder.

HIGHLIGHTS

We examined symptoms of adjustment disorder in 15,563 adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The prevalence of probable adjustment disorder was 18.2%.

We identified stressors, risk, and protective factors that may help identify individuals at higher risk for adjustment disorder.

Antecedentes: La pandemia de COVID-19 expone a las personas a múltiples factores estresantes, como la cuarentena, el distanciamiento físico, la pérdida del trabajo, el riesgo de infección, y la pérdida de seres queridos. Esta compleja serie de factores estresantes puede potencialmente conducir a síntomas del trastorno de adaptación.

Objetivo: Este estudio exploratorio transversal examinó las relaciones entre los factores de riesgo y de protección, los factores estresantes, y los síntomas del trastorno de adaptación durante el primer año de la pandemia de COVID-19.

Métodos: Se utilizaron datos de la primera ola del estudio longitudinal ADJUST de la Sociedad Europea de Estudios de Estrés Traumático (ESTSS en su sigla en inglés). N = 15.563 participantes de 18 años o más fueron reclutados en once países (Austria, Croacia, Georgia, Alemania, Grecia, Italia, Lituania, Países Bajos, Polonia, Portugal, y Suecia) de junio a noviembre de 2020. Se examinaron mediante regresión lineal multivariante las asociaciones entre los factores de riesgo y de protección (p. ej., género, diagnóstico de un trastorno de salud mental), factores estresantes (p. ej., miedo a la infección, contacto restringido cara a cara), y síntomas del trastorno de adaptación (ADNM-8 en su sigla en inglés).

Resultados: La prevalencia del trastorno de adaptación probable autoinformado fue del 18,2%. Los factores de riesgo asociados con niveles más altos de síntomas del trastorno de adaptación fueron género femenino, edad avanzada, riesgo de enfermedad grave por COVID-19, peor estado de salud general, exposición a un trauma actual o anterior, un trastorno de salud mental actual o anterior, y una exposición más prolongada a las noticias de COVID-19. Los factores de protección relacionados con niveles más bajos de síntomas del trastorno de adaptación fueron mayores ingresos, estar jubilado, y tener más contacto cara a cara con sus seres queridos o amigos. Los factores estresantes relacionados con la pandemia que se asociaron con niveles más altos de síntomas del trastorno de adaptación incluyeron miedo a la infección, manejo gubernamental de crisis, contacto social restringido, problemas relacionados con el trabajo, actividad restringida, y condiciones de vivienda difíciles.

Conclusiones: Identificamos factores estresantes, de riesgo, y protectores que pueden ayudar a identificar a las personas con mayor riesgo de trastorno de adaptación.

背景: COVID-19 疫情使个人面临多重应激源, 例如隔离, 躯体疏离, 失业, 感染风险和失去亲人。如此复杂的一系列应激源可能会导致适应障碍的症状。

目的: 本横断面探索性研究考查了 COVID-19 疫情第一年适应障碍的风险与保护因素, 应激源和症状之间的关系。

方法: 使用了欧洲创伤应激研究协会 (ESTSS) 纵向 ADJUST 研究的第一波数据。 2020 年 6 月至 11 月期间, 在 11 个国家 (奥地利, 克罗地亚, 格鲁吉亚, 德国, 希腊, 意大利, 立陶宛, 荷兰, 波兰, 葡萄牙和瑞典) 招募了 15,563 名 18 岁及以上的参与者。使用多元线性回归考查了适应障碍的因素 (例如, 性别, 精神健康障碍诊断), 应激源 (例如, 害怕感染, 限制面对面接触) 和症状 (ADNM-8)。

结果: 自我报告的可能适应障碍的流行率为 18.2%。与较高水平适应障碍症状相关的风险因素是女性, 年龄较大, 有患严重 COVID-19 疾病的风险, 一般健康状况较差, 当前或以前的创伤暴露, 当前或以前的心理健康障碍以及接触 COVID-19 新闻时间更长。与较低水平适应障碍症状相关的保护因素是较高的收入, 退休以及与亲人或朋友有更多面对面接触。与较高水平适应障碍症状相关的疫情相关应激源包括害怕感染, 政府危机管理, 社交接触受限, 工作相关问题, 活动受限和住房条件困难。

结论: 我们确定了可能有助于识别适应障碍风险较高个体的应激源, 风险和保护因素。

1. Introduction

With the global COVID-19 pandemic, Europe faced one of the most significant challenges in decades, with unique and devastating effects on worldwide lives. By July 2021, the COVID-19 transmission is widespread in the European Union and the European Economic Area, with 33,270,049 COVID-19 cases and 740,809 deaths (ECDC, Citation2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic places multiple stressors on entire populations. It has caused illness, deaths, and strain on healthcare and economic systems. People are afraid of contracting COVID-19, have to cope with COVID-19 symptoms, physical distancing, or grieving the loss of loved ones. Countries have adopted governmental public health policies to contain the spread of COVID-19, such as quarantine, physical distancing, and restriction of individual rights. Governments cancelled public events and gatherings, closed shops, restaurants, and schools, restricted public transport, and enacted remote working (IMF, Citation2021). Some individuals lost their work and income. Even when the ecological disaster is under control, long-term psychological, societal, and economic disruptions can be expected (Gersons, Smid, Smit, Kazlauskas, & McFarlane, Citation2020).

Given the cumulative burden of these pandemic-specific stressors, people may develop symptoms of adjustment disorder (AjD). AjD is characterized by failure to adapt to stressors such as illness or disability, socio-economic problems, and conflicts at home (WHO, Citation2021). The main features of AjD concern preoccupation with the stressor or its consequences, manifested in excessive worry, recurrent and distressing thoughts about the stressor, or constant rumination about its consequences. Symptoms of AjD usually emerge within a month of the stressor and can cause significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational functioning (WHO, Citation2021).

Despite the multiple stressors people face during the current pandemic, to our knowledge, only two studies assessed AjD in the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. An Italian survey used the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire (IADQ; Shevlin et al., Citation2020) to measure self-reported probable AjD, identified in 22.9% of the participants (Rossi et al., Citation2020). A Polish study (Dragan, Grajewski, & Shevlin, Citation2021) assessed self-reported probable AjD with the Adjustment Disorder-New Module 20 (ADNM-20; Einsle, Köllner, Dannemann, & Maercker, Citation2010). The study found that about half (49.0%) of the participants reported probable AjD. Several studies conducted during the early phase of the pandemic reported high levels of psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (Xiong et al., Citation2020).

Within the WHO’s health framework (Solar & Irwin, Citation2010), biological, psychosocial, and material (e.g. living and working conditions) risk and protective factors may buffer or intensify the effects of the stressors on mental health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, biological risk factors (e.g. gender, age, COVID-19 infection), psychosocial factors (e.g. lack of social support), and material factors could be determinants of mental health (for a COVID-19 framework of determinants of health, see Lotzin et al., Citation2020). However, knowledge about which of these factors are related to higher symptom levels of AjD during the COVID-19 pandemic is scarce (Rajkumar, Citation2020).

One study (Dragan et al., Citation2021) examined associations between risk factors and AjD symptom levels using the ADNM-20. The study found that female gender and lack of a full-time job were associated with higher symptom levels of AjD. An Italian study identified female gender and younger age as risk factors for higher AjD symptom levels (Rossi et al., Citation2020). Research on risk factors for probable AjD before the pandemic indicated that loneliness, job loss, dysfunctional disclosure, and lower self-efficacy were associated with higher symptom levels of AjD (Lorenz, Perkonigg, & Maercker, Citation2018). However, the results from studies conducted before the pandemic might not be generalizable to the context of a global pandemic in which multiple pandemic-specific stressors co-occur.

A systematic review synthesized research on the relationships between risk factors and clinical symptoms during the early phase of the pandemic (Xiong et al., Citation2020). Female gender, younger age, unemployment, a pre-existing physical disorder, and a mental health disorder were related to higher levels of psychological distress (Xiong et al., Citation2020). However, the measures and designs of the included studies were heterogeneous and, therefore, difficult to compare. The review did not report relationships between these risk factors and symptom levels of AjD. An Italian study (Rossi et al., Citation2021) examined a wide range of trauma and stress-related symptoms, grouped into the three factors of Negative Affect (depressed mood, anxiety, irritability), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms, and Dissociative Symptoms. Higher scores on these factors were associated with younger age, female gender, and stressful events.

Given the high psychological burden during the COVID-19 pandemic, it seems essential to better understand the relationships between risk and protective factors, stressors, and symptoms of AjD during the COVID-19 pandemic. This exploratory research aimed to examine cross-sectional relationships between risk and protective factors (e.g. age, gender, income), stressors (e.g. fear of infection, restricted social contact, problems with childcare), and symptoms of AjD during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. This knowledge can help identify potential risk and protective factors for probable AjD.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design and setting

Data were drawn from the first wave of the European Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS) pan-European study, named ‘ADJUST study.’ The ADJUST study investigates longitudinal associations between risk and protective factors, stressors, and symptoms of adjustment disorder during the COVID-19 pandemic in eleven European countries (Austria, Croatia, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Sweden). Recruitment is ongoing; the longitudinal analyses will be presented in future publications when the data will be available.

2.2. Participants

We recruited from the general populations of the participating countries (see above). Inclusion criteria were (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) ability to read and write in the respective language, and (3) willingness to participate in the study. The study aimed to include at least 1,000 participants per country (2,000 for countries with >15 million inhabitants). We conducted no a priori sample size calculation for the analysis reported in this manuscript, as we designed the power calculation for the longitudinal data analysis (Lotzin et al., Citation2020).

3. Measures

3.1. Symptoms of adjustment disorder

We assessed symptoms of AjD as the dependent variable using the Adjustment Disorder – New Module 8 scale (ADNM-8; Kazlauskas, Gegieckaite, Eimontas, Zelviene, & Maercker, Citation2018). The ADNM-8 is a self-report measure of symptoms of AjD according to ICD-11 consisting of eight items, with a response format from 1 to 4 (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often). A total score (ranging from 8 to 32) is calculated by summing the item scores. A cut-off score of >22 indicates probable AjD.

The ADNM-8 is the short form of the ADNM-20; the measures are widely used in ICD-11 adjustment disorder research (Kazlauskas, Zelviene, Lorenz, Quero, & Maercker, Citation2017). Empirical studies of the ADNM-8 psychometric properties found strong support for structural and convergent validity of the ADNM-8 in large samples (Ben-Ezra, Mahat-Shamir, Lorenz, Lavenda, & Maercker, Citation2018; Kazlauskas et al., Citation2017). A recent study in a representative Israelian sample (N = 1,007) indicated excellent accuracy of the ADNM-8 to diagnose AjD according to the ICD-11 criteria (Ben-Ezra et al., Citation2018).

3.2. Risk and protective factors

For selecting risk and protective factors, a conceptual framework on the determinants of mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic was developed (Lotzin et al., Citation2020), based on the WHO framework for social determinants of health (Solar & Irwin, Citation2010).

Risk and protective factors included sociodemographic characteristics (, e.g. age, gender, income), pandemic-related characteristics (, e.g. frequency of face-to-face contact, frequency of news consumption), and health-related characteristics (, e.g. general physical health, perceived risk for a severe COVID-19 infection). We assessed the perceived risk of COVID-19 infection as follows: ‘Do you think that you are at risk for severe or life-threatening symptoms of the coronavirus disease?’. Items were self-constructed, except for the items assessing trauma exposure.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics (N = 15,563)

Table 2. Pandemic-related characteristics (N = 15,563)

Table 3. Health-related characteristics (N = 15,563)

Trauma exposure was measured using the Criterion A section of the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Weathers, Keane, Palmieri, Marx, & Schnurr, Citation2013). Participants indicated whether they experienced stressful event(s) involving actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence before the COVID-19 pandemic. We surveyed trauma exposure separately for the period before the pandemic and during the pandemic.

3.2.1. Pandemic-related stressors

The burden of pandemic-related stressors within the last month was assessed by a self-constructed 30-item questionnaire named Pandemic Stressor Scale (PaSS). We constructed the PaSS by reviewing the relevant literature (e.g. Taylor, Citation2019; Wheaton, Abramowitz, Berman, Fabricant, & Olatunji, Citation2012) and existing surveys on stressors of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g. Lages et al., Citation2021; Veer et al., Citation2021). A clinical psychologist and trauma and stress researcher (first author) constructed an item set, the ADJUST study consortium consisting of trauma and stress research experts reviewed and revised the items. The initial questionnaire contained 43 pandemic-specific stressors that used the instruction ‘Please indicate how much the following things have burdened you due to the coronavirus pandemic within the last month.’ The items were rated on a five-point scale (0 = ‘Not at all burdened’; 1 = ‘Somewhat burdened’; 2 = ‘Moderately burdened’; 3 = ‘Strongly burdened, 4 = ‘Does not apply to me’).

To examine the factor structure of the pandemic stressor items, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in the German sample of the ADJUST study (for details, see Lotzin et al., Citation2021). We reduced the item set based on items’ psychometric properties. The final EFA included 30 items that yielded a nine-factor-solution: Crisis management and communication (poor information from the government; poor crisis management; media coverage of the coronavirus pandemic); Fear of infection (uncertainty about duration and risks of the coronavirus pandemic; fear of getting infected with the coronavirus; fear of infecting others with the coronavirus, fear that loved ones get infected with the coronavirus); Burden of infection (own infection with the coronavirus; infection of loved ones with the coronavirus; death of a loved one due to the coronavirus infection); Restricted Face-to-face contact (restricted face-to-face contact with loved ones; restricted face-to-face contact with others; restricted physical closeness to loved ones; social isolation); Restricted activity (restricted everyday activity (e.g. shopping); restricted leisure activity (e.g. restaurant visit); restricted private travelling); Work-related problems (not being able to work; (threat of) income loss; (threat of) job loss; insufficient financial support by the government); Difficult housing conditions, (restricted housing conditions (little space); no place of retreat; conflicts at home); Problems with childcare (loss of childcare and difficulties with combining work with childcare); Restricted access to resources (restricted access to goods, e.g. food, water, clothing; restricted access to regular health care or medication; insufficient capacity of the health care system for seriously ill people).

The nine-factor structure could be replicated in a confirmatory factor analysis using the data of the Austrian sample of the ADJUST study (Lotzin et al., Citation2021). We computed subscale scores by calculating the average of the scores of the relevant items. Before calculating subscores, we recoded the ‘Does not apply to me’ category to ‘Not at all burdened.’ The core item set was developed in the English language. A native speaker then translated the core item set at the study site. A second native speaker checked the correctness of the translation.

4. Data analysis

We imputed missing values of all independent variables using multiple imputation following the guidelines by White, Royston, and Wood (Citation2011). The number of imputed data sets corresponded to the percentage of incomplete cases. All variables of this data analysis were included in the imputation model. Additional variables were selected for the imputation model based on their correlation with the incomplete variables.

A linear multivariate regression model with the AjD symptom score as dependent variable (ADNM-8) was run with all cases with non-missing values in the dependent variable (n = 14,483). As independent variables, risk and protective factors (see methods section) and the nine PaSS stressor subscales were included in the analysis. Country of residence (‘In which country do you currently live?’) was included in the analysis to adjust for possible between-country differences. As this is an exploratory study, p-values were not adjusted for multiplicity. The p-values represent descriptive summary measures and are not the result of confirmatory testing. Descriptive statistics of all variables included in the analysis were computed for the whole sample stratified by country. Mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range were computed, as appropriate, for the continuous variables; absolute and relative frequencies were computed for categorical variables. The same analysis was performed with complete cases (n = 10,086) as sensitivity analysis, revealing comparable results. All analyses were conducted with R-3.5.3 for Windows.

4.1. Procedure

Data were collected from June to November 2020 in eleven countries (please see Supplement 1 for details of the pandemic and lockdown characteristics by country). Given that face-to-face contact was restricted due to containment measures, recruitment was predominantly conducted online. We applied different recruitment strategies to increase the variability of the sample in terms of gender, age, and education. We promoted the study via social platforms (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp), leisure and interest groups (e.g. bicycle or car clubs), newsletters (e.g. newsletters of large companies), and via advertisements in newspapers and magazines. We also disseminated the study information through universities, different stakeholders, and professional organizations. In some countries, printed flyers were distributed. The study site in Poland recruited participants via a professional panel service (Supplement 2 describes the recruitment strategies by country). Interested individuals received an invitation to participate in the study by a website link to the survey. After providing consent, they could complete an online survey.

5. Results

Out of the 15,563 participants, 13,301 (85,47%) completed the survey. Cases were complete (i.e. no missing values in the variables used in analysis) in 10,086 (64,81%) participants. Missing values ranged from 14 (0.09%, age) to 1,797 (11,55%, work area) in the independent variables ().

Table 4. Pandemic-related stressors (N = 15,563)

5.1. Sample characteristics

5.1.1. Sociodemographic health-related, and clinical characteristics

We included N = 15,563 participants from eleven countries. The sample was high-educated but varied in age and income ().

Pandemic-related characteristics. About eight out of ten participants stated to have spent more time at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic (). At the time of assessment, they had spent about five hours per day outside the home, on average.

Health characteristics. The prevalence of self-reported probable AjD was 18.2% (). Almost two out of 100 (1.7%) reported a COVID-19 contraction according to a positive test result, 1 out of 1000 (0.1%) were currently affected. Among the assessed nine stressor domains, fear of infection was perceived as most burdensome ().

5.2. Relationships between risk and protective factors, stressors and symptoms of AjD

5.2.1. Risk and protective factors

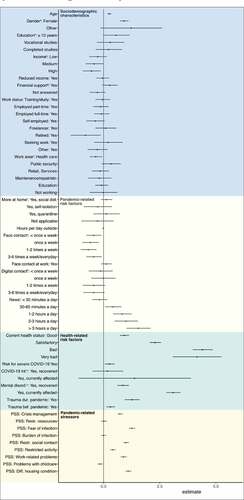

Female gender, older age, (perceived) risk for a severe COVID-19 disease, trauma exposure during or before the pandemic, and a current or previous mental health disorder were related to higher levels of symptoms of AjD. Compared to a ‘very good’ current general health status, a less good health status (‘good’, ‘satisfactory’, ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’) was related to higher levels of symptoms of AjD. Protective factors. Medium and high income (vs. very low income), working in healthcare (vs. other work areas than education, maintenance, retail, services, public security), being retired (vs. in training/education), and having more face-to-face and digital social contacts were related to lower levels of symptoms of AjD. Education, reduced income due to the COVID-19 pandemic, governmental financial support, spending more time at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, hours spent outside the home, and frequency of digital social contact showed no associations with AjD symptom levels.

5.2.2. Pandemic stressors

Six out of nine pandemic stressor domains were positively related to symptoms of AjD (all p < .001, , for effect estimates and p-values see ). These included ‘Governmental crisis communication/management’, ‘Fear of infection’, ‘Restricted face-to-face contact’, ‘Work-related problems’, ‘Restricted (leisure and everyday) activity’, and ‘Difficult housing conditions’. ‘Problems with childcare’ was negatively associated with levels of symptoms of AjD. For the two remaining stressor domains ‘restricted access to resources’ and ‘burden of infection’, no relationship with AjD symptom levels were observed.

Table 5. Effect estimates of regression analysis

Figure 1. Effect estimates of multivariate regression analysis

The analysis was controlled for country of residence, which was related to levels of symptoms of AjD. Compared to Germany, AjD symptom levels were lower in all remaining countries except Lithuania and Georgia.

6. Discussion

This explorative study examined the relationships between risk and protective factors, stressors, and symptoms of AjD in the general populations of eleven European countries in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. AjD is characterized by failure to adapt to stressors that manifests in worry, recurrent and distressing thoughts about the stressor, or constant rumination about its implications. The disorder can cause significant impairment in social or occupational functioning (WHO, Citation2021).

In a large sample obtained in eleven European countries, we found a prevalence rate of self-reported probable AjD of 18.2%. In European general population samples assessed before the pandemic, 15.5% met the diagnostic criteria for AjD according to ICD-11 (Perkonigg, Lorenz, & Maercker, Citation2018). The higher prevalence rate found in this study could indicate an increase in AjD. However, evidence on other mental disorders such as depression during the pandemic does not suggest asharp increase in mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic (Sun et al., Citation2021).

Only a few studies examined prevalence rates of AjD during the COVID-19 pandemic. An Italian study (Rossi et al., Citation2020) found a slightly higher prevalence rate of 22.9% for self-reported probable AjD during the initial phase of the COVID-19 outbreak (Rossi et al., Citation2020). In a Polish study, 49.0% of the participants reported increased symptom levels of AjD in the initial phase of the pandemic (Dragan et al., Citation2021). Psychological distress might have been increased in the initial phase, as an entirely unknown situation challenged individuals. Symptoms may have decreased with increasing experience with the pandemic circumstances in the following months, the period in which we conducted this study. However, chronic exposure to the pandemic-specific stressors may lead to increased symptoms of AjD in the long term. Future studies might examine trajectories of symptoms during different stages of the pandemic.

6.1. Risk and protective factors

6.1.1. Sociodemographic characteristics

6.1.1.1. Gender

Female gender was associated with higher AjD symptom levels. Two earlier studies found positive associations between female gender and self-reported symptoms of AjD during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic (Dragan et al., Citation2021; Rossi et al., Citation2020). Additional studies reported relationships between female gender and psychological distress, anxiety, and depression during the pandemic (Liu et al., Citation2020; Mazza et al., Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2020). It is well established for non-pandemic times that women have higher anxiety and depression symptoms than men (Bracke et al., Citation2020). Women more often work in healthcare, retail, and service industries than men, which might be disproportionately negatively affected by the lockdown measures. Women may experience additional burdens as the primary caregiver of children and elderly family members. In addition to social aspects, biological factors might explain higher AjD symptom levels in women. Men and women differ in their HPA axis stress response patterns, making women more vulnerable to developing anxiety- and stress-related disorders (Goel, Workman, Lee, Innala, & Viau, Citation2014).

6.1.1.2. Age

We found a positive relationship between age and AjD symptoms. The elderly might be more strained by carrying a higher risk for severe or life-threatening COVID-19 than younger individuals. The elderly might be less mobile and less familiar with digital technologies than younger individuals, adding additional burdens. Our result contrasts with one earlier study reporting that younger age was related to higher levels of AjD symptoms (Rossi et al., Citation2020). Studies on the relationships between risk factors and symptoms of anxiety or depression found inconsistent results (Xiong et al., Citation2020), with a higher proportion of studies reporting a negative relationship between age and symptoms of anxiety or depression (Gao et al., Citation2020; Mazza et al., Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2020). Compared to most previous online surveys (Xiong et al., Citation2020), we included more participants aged from 60, which might face higher distress levels than other age groups. At the other end of the age spectrum, we excluded adolescents and included only a few young adults, which might be a second particularly vulnerable group we did not adequately capture. To rule out a nonlinear relationship between age and AjD symptom levels, we inspected the data accordingly, but could not find a nonlinear relationship. Our study differs from the previous studies in the number of variables included in the analysis. We controlled the effect of age on symptoms of AjD for many independent variables that might have confounded the previous study results. However, another study with similar methodological features (i.e. large proportion of older participants, no adolescents, numerous covariates) has reported greater distress among younger patients (Sherman, Williams, Amick, Hudson, & Messias, Citation2020).

6.1.1.3. Education

Consistent with one earlier study (Mazza et al., Citation2020), we found that lower education was related to higher levels of symptoms of AjD. Earlier research on the relationships between education and symptoms of depression or anxiety were heterogeneous, with more studies reporting relationships between lower education and higher levels of symptoms of depression or anxiety (Gao et al., Citation2020; Mazza et al., Citation2020; Wang, Kala et al., Citation2020). Lower levels of education might be related to lower levels of precarious working conditions, job loss, and low health and technical literacy. One earlier study found that higher education was related to higher levels of depressive symptoms (Wang, Pan et al., Citation2020), another study reported no relationship between these variables (Jahanshahi, Dinani, Madavani, Li, & Zhang, Citation2020). The studies conducted so far during the pandemic underrepresent participants with low education. Future studies using representative samples are required to further explore the relationships between education and AjD symptoms.

6.1.1.4. Income

In our study, higher income levels were related to lower AjD symptom levels. Higher-income enables access to buyable resources (e.g. health care, childcare), thus facilitating better adjustment to the pandemic. It also gives a sense of stability and belonging to society (Mimoun, Ben Ari, & Margalit, Citation2020). Earlier studies reported relationships between higher income and lower levels of depression (Lei et al., Citation2020; Olagoke, Olagoke, & Hughes, Citation2020). Associations between higher income and higher levels of anxiety, insomnia (Pieh, O´Rourke, Budimir, & Probst, Citation2020) and a better general mental health also have been reported (Pierce et al., Citation2020). In our study, we additionally assessed income loss due to the pandemic and governmental financial support, which were both unrelated to AjD symptom levels. This result contrasts with one earlier study (Hertz-Palmor et al., Citation2021) that found that income loss was associated with higher levels of depression and anxiety symptoms.

6.1.1.5. Work-related factors

Being retired was associated with lower AjD symptom levels. Retired persons might experience fewer stressors related to education or work. In contrast to earlier studies reporting that student status was a significant risk factor for higher levels of depressive symptoms (González-Sanguino et al., Citation2020; Lei et al., Citation2020), we did not find that student or training status was related to higher AjD symptom levels. Our analysis of the effects of a student status included adjustment for the effects of several other factors (e.g. restricted social contact, reduced income) that might explain the correlation between student status and depressive symptoms in earlier studies.

Working in healthcare, public security, retail or services, maintenance, or education, was unrelated to AjD symptoms, compared to ‘other’ working areas that we did not assess. This unexpected result might be related to the finding that a high proportion of the participants selected the ‘other work area’ category. This category might include participants with heterogenous levels of AjD symptoms. In addition, the categories that we covered might not be specific enough to indicate high-risk groups of AjD. For example, among the category of healthcare professionals, those working as frontline workers may report high levels of AjD, whereas healthcare professionals working in other areas of healthcare may report lower levels. Furthermore, our analysis on the relationships between work area and symptoms of AjD included adjustment for the effects of many other correlated factors. These included the increased risk for contracting COVID-19 and exposure to traumatic events, which could be underlying factors explaining the association between work area and symptoms of AjD.

Having face-to-face contact at work was unrelated to AjD symptom levels. Rather, we found that increased fear of contracting COVID-19 was significantly associated with higher AjD symptom levels (see pandemic-related factors); fear of contracting COVID-19 might be correlated with face-to-face contact at work.

6.1.2. Pandemic-related factors

A higher frequency per week of face-to-face contact with loved ones or friends was related to lower AjD symptom levels. Interestingly, a higher frequency of digital social contact with loved ones or friends (e.g. by phone, Skype, or Zoom) was unrelated to AjD symptom levels, suggesting the possible need for face-to-face contact to enhance mental health during and in the aftermath of the pandemic.

Spending more time at home and hours spent outside the home were unrelated to AjD symptom levels (). Spending more time outside the home might be related to various activities that could be a source of either recovery or distress, such as leisure activities and work.

Higher reported duration of news consumption about COVID-19 was associated with higher AjD symptom levels. Earlier research found associations between media consumption about COVID-19 and higher symptom levels of depression or anxiety (Gao et al., Citation2020; Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, Citation2020). Frequent social media consumption may increase anxiety due to potential misinformation about the risks.

6.1.3. Health-related characteristics

A current health status perceived as less than ‘very good’ was related to higher AjD symptom levels. People with perceived poor health status (‘bad’ or ‘very bad’) reported the highest levels of AjD symptoms. Previous medical problems or chronic physical diseases were related to higher symptom levels of distress, anxiety, and depression in earlier COVID-19 studies (Mazza et al., Citation2020; Özdin & Bayrak Özdin, Citation2020; Wang, Kala et al., Citation2020). Widespread conditions such as obesity (Hussain, Mahawar, Xia, Yang, & Shamsi, Citation2020), diabetes, hypertension (Sawalha, Zhao, Coit, & Lu, Citation2020), and autoimmune diseases (Emami, Javanmardi, Pirbonyeh, & Akbari, Citation2020) were related to higher mortality rates after contracting COVID-19. People with chronic health conditions might also be affected by supply shortages of medical services due to the lockdown. Poor health status was related to a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 in earlier research (Hatch et al., Citation2018), leading to additional distress. Consistent with this result, perceived higher risk for severe COVID-19 was related to higher symptom levels of AjD in our study.

A current or earlier COVID-19 infection verified by a positive COVID-19 test was unrelated to AjD symptom levels in our study. Given the timepoint of the study, only a few participants in our sample were tested positive. Additional studies with a larger proportion of COVID-19 tested participants may be better positioned to examine associations between COVID-19 infection and symptoms of AjD.

6.1.4. Mental health-related characteristics

Current or previous diagnosis of a mental health disorder was related to higher AjD symptom levels in our study. This result is in line with an Italian study showing that a prior psychiatric diagnosis was related to higher levels of AjD symptoms (Rossi et al., Citation2020). Other studies reported a relationship between a history of mental health problems and anxiety (Mazza et al., Citation2020; Özdin & Bayrak Özdin, Citation2020) or depression during the COVID-19 pandemic (Mazza et al., Citation2020). In people with a pre-existing mental health disorder, the multiple stressors during the pandemic might worsen their condition. For example, the fear of getting infected and feeling helpless may trigger clinical symptoms (Hall, Hall, & Chapman, Citation2008).

Trauma exposure was related to higher AjD symptom levels. The association between trauma exposure and AjD symptoms was stronger concerning trauma exposure during the pandemic than concerning trauma exposure before the pandemic. A history of trauma exposure is a general risk factor for developing mental health disorders, such as AjD (Asselmann, Wittchen, Lieb, Perkonigg, & Beesdo-Baum, Citation2018). Previous research found that having a loved one deceased by COVID-19 was associated with self-reported distress and depression (Rossi et al., Citation2020).

6.1.5. Burden of pandemic-related stressors

Out of the nine assessed stressor domains, seven domains showed relationships with levels of AjD symptoms. Distress related to inefficient Crisis management and communication were related to higher AjD symptom levels, suggesting the possible role of governmental media for mental health in the general population. Distress due to Fear of infection was associated with higher AjD symptom levels. This result could indicate the need to address COVID-19 related fears in preventive interventions to reduce distress and AjD symptoms. The perceived Burden of infection was unrelated to AjD symptom levels, which might be since a low proportion of participants contracted COVID-19. Severely affected people might also have not been able to participate in the survey. Distress related to Restricted face-to-face contact was associated with higher AjD symptom levels. In earlier research conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, social support (Zhang & Ma, Citation2020) and good family relations (Dong et al., Citation2020) showed relationships with lower levels of distress. Restricted activity such as shopping, restaurant visits, and restricted private travelling was associated with higher AjD symptom levels, suggesting that preventive interventions may include possible activities during a pandemic. Distress due to work-related problems, including not being able to work, (threat of) income or job loss, and insufficient financial support by the government, was related to increased AjD symptoms levels. Participants with a higher perceived risk of losing income or their job during the COVID-19 pandemic reported significantly higher levels of distress, anxiety, and depression in an earlier study (Rodríguez-Rey, Garrido-Hernansaiz, & Collado, Citation2020). Distress related to Difficult housing conditions, such as restricted housing conditions and conflicts at home, was associated with higher AjD symptom levels. Poor housing has been associated with increased levels of depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic (Amerio et al., Citation2020), particularly in small apartments with poor views.

Distress due to Problems with childcare (i.e. loss of childcare and difficulties with combining work with childcare) were unrelated to symptoms of AjD in our study. While it could be a challenge to take care of children at home during confinement, the related distress might be buffered by the affective support provided by this intimate relationship. However, it is also plausible that parents experiencing significant problems with childcare were underrepresented in our sample due to their high caregiving burden and lack of time resources to participate in the survey. Furthermore, 46.2% of the participants had no children, which might have restricted the variance in the data. In an earlier study on parents, those who perceived it challenging to cope with the quarantine situation reported high levels of distress (Spinelli, Lionetti, Pastore, & Fasolo, Citation2020).

Distress due to Restricted access to resources such as food, regular health care or medication was unrelated to AjD symptom levels. Other studies have found associations between higher food scarcity and higher levels of depression and anxiety (Fang, Thomsen, & Nayga, Citation2021; Polsky & Gilmour, Citation2020). Another study found that limited access to healthcare in individuals with epilepsy was related to higher symptom levels of depression. (Van Hees et al., Citation2020). The results of the present study might suggest that not many of the participants of this survey might have been affected by restricted access to these resources. Additional studies might analyse relationships between limited resources and symptoms of AjD in subgroups of people that have faced a lack of resources.

7. Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the large sample from eleven countries. So far, such cross-cultural studies are rare. We pre-registered the study and used a well-established instrument as the dependent variable, in addition to tailored measures to assess the specific stressors relevant for the current COVID-19 pandemic.

A limitation of the study is the use of a non-probabilistic sample. Our sample overrepresents women and individuals with high education and is not representative of individuals with no or poor internet accessibility. Another limitation concerns the use of different recruitment strategies in the participating countries (please see Supplement 2). For example, Poland recruited participants via panel lists, while the remaining countries recruited participants via social media, leisure and interest groups, and stakeholders. Differences in recruitment strategies might be related to the over- or underrepresentation of subgroups of the general population. The participants were self-selected; we might have overrepresented individuals with a higher psychological distress as they might be more inclined to fill out a survey on mental health problems. On the other hand, individuals with a severe mental illness – who likely represent a COVID-19 risk group – have been shown to be underrepresented in online surveys (Pierce et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, the use of self-report measures could have introduced systematic bias. We self-constructed the PaSS to measure pandemic-specific stressor domains; while we psychometrically tested the generated subscales and found first evidence for their validity, the measure was not evaluated previously. Similarly, most of the items targeting risk and protective factors were self-constructed and were thus not psychometrically tested. In addition, some of the mental-health related risk factors (e.g. a current diagnosis of a mental health disorder) might tap into constructs that may overlap with the dependent variable.

Another limitation concerns the cross-sectional analysis, which precludes causal interpretations and the examination of longitudinal relationships. Furthermore, we collected the data during the summer and autumn 2020. It might be possible that psychological distress peaked at the beginning of the outbreak when individuals experienced an entirely unfamiliar situation (Ho, Chee, & Ho, Citation2020). On the contrary, individuals might experience increased psychological distress and symptoms of AjD in the long-term course of the pandemic when people need to cope with the chronicity of burden. Studies using follow-up assessments might examine trajectories of AjD symptoms during the pandemic to understand the long-term impact in different pandemic phases.

While we controlled for country-level differences, we did not consider different regions of the countries, which might be related to different stages and severities of the pandemic. While we controlled for country-level differences, we did not consider different regions of the countries, which might be related to different stages and severities of the pandemic. At the time the participants responded, the infection rates and the invasiveness of restrictions differed between countries (please see Supplement 1), which may have influenced the results.

Although we recruited participants in eleven countries, we did not include all European countries. Generalizations among the general population at a European level should therefore be made with caution.

8. Conclusions

We found high rates for self-reported probable AjD (18.2%) in the general population during the second and third quarter of the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Higher levels of symptoms of AjD were related to several risk and protective factors and pandemic-specific stressors. The findings of this study may help identify potential risk and protective factors to be examined in future research. If the factors identified in this study will repeatedly emerge in other investigations, psychosocial interventions may target people with the respective high-risk profiles. These may include those with a poor health condition, fear of COVID-19 infection, a diagnosis of a mental health disorder, trauma exposure, lack of social support, work-related problems, and restricted housing conditions. Given the high rate of self-reported probable AjD found in this study, monitoring of mental health problems as well as mental health care delivery for those in need should be a priority in addition to vaccination and other containment measures.

9. Ethics, consent, and permissions

The study was registered in a study registry before its start (OSF registry, doi: 10.17605/OSF.IO/8XHYG). Each country obtained ethical approval of the study: Ethics Committee of the University of Vienna, 00554. Ethics Committee of the University of Urbino ‘Carlo Bo’, 34, 22/07/2020. Ethics Committee of the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, 21 May 2020. Ethics Review Board of the Faculty of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Utrecht University, 20–360. Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Science Research Ethics Committee, 12/06/2020. Local Psychological Ethics Committee at the Centre for Psychosocial Medicine, LPEK-0149. Social Sciences Ethics Review Board (SSERB), University of Nicosia, SSERB 00109. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority, 2020–03217. Vilnius University Ethics Committee of Research in Psychology, 44. Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, 6/7/2020. Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty, University of Porto and Centro Hospitalar São João, Porto, CE 201–20. The National Ethical Review Board in Sweden, 2020–03217. All participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study. Participants were informed that they were under no obligation to participate and that they could withdraw at any time from the study without consequences.

10. Data protection and quality assurance

The dataset for the data analysis was stored on a server of the coordinating site (Centre for Interdisciplinary Addiction Research, CIAR, University of Hamburg). Data handling followed the EU General Data Protection Regulation (DSGVO); data will be stored for at least 10 years.

Author contributions

AL designed the study in cooperation with all members of the ADJUST consortium formed by the representatives of the ESTSS countries. All authors except LK recruited study participants and contributed to the data management of the respective site. AL coordinated the data management. LK conducted the data analysis. AL drafted the manuscript, all authors revised sections of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Acknowledgments

The authors thank the collaborators for their support and contribution to the present paper: Ozan Demirok (team Austria); Marina Ajdukovic, Helena Bakic, Ines Rezo Bagaric, Tanja Franciskovic (team Croatia); Nino Makhashvili and Sophio Vibliani (team Georgia); Eleftheria Eugeniou, George Fevgas, Kostas Messas, Marianna Philippidou, Eleni Papathanasiou, Anastasia Selidou (team Cyprus/Greece); Ilaria Cinieri, Alessandra Gallo and Chiara Marangio (team Italia); Monika Kvedaraite and Auguste Nomeikaite (team Lithuania); Joanne Mouthaan, Suzan Soydas, Marloes Eidhof, Marie José van Hoof and Simon Groen (team Netherlands); Magdalena Skrodzka and Monika Folkierska-Żukowska (team Poland); Aida Dias, Camila Borges, Diana Andringa, Guida Manuel, Joana Beker and João Veloso, Francisco Freitas (team Portugal); Kristina Bondjers, Josefin Sveen, Rakel Eklund, Kerstin Bergh Johannesson and Ida Hensler (team Sweden).

We greatly thank the study team of the coordinating site at University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (team Germany) that prepared the survey and conducted the overall data management, in particular Laura Kenntemich, who was supported by Sven Buth, Eike Neumann-Runde, Ronja Ketelsen, Lennart Schwierzke, Julia Groß, and Laura Gutewort. We also thank Ann-Kathrin Ozga for her statistical advice.

Data availability

The detailed sociodemographic information of the dataset does not fully protect the anonymity of the respondents. For this reason, the entire dataset cannot be made publicly available. However, excerpts of the data on a higher aggregation level can be provided upon justified request by the first author.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial interests that could be perceived as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amerio, A., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Aguglia, A., Bianchi, D., Santi, F., ... & Capolongo, S. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5973. doi:10.3390/ijerph17165973

- Asselmann, E., Wittchen, H.-U., Lieb, R., Perkonigg, A., & Beesdo-Baum, K. (2018). Incident mental disorders in the aftermath of traumatic events: A prospective-longitudinal community study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 82–16. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.004

- Ben-Ezra, M., Mahat-Shamir, M., Lorenz, L., Lavenda, O., & Maercker, A. (2018). Screening of adjustment disorder: Scale based on the ICD-11 and the Adjustment Disorder New Module. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 103, 91–96. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.011

- Bracke, P., Delaruelle, K., Dereuddre, R., & Van de Velde, S. (2020). Depression in women and men, cumulative disadvantage and gender inequality in 29 European countries. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 267, 113354. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113354

- Dong, Z.-Q., Ma, J., Hao, Y.-N., Shen, X.-L., Liu, F., Gao, Y., & Zhang, L. (2020). The social psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical staff in China: A cross-sectional study. European Psychiatry, 63(1). doi:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.59

- Dragan, M., Grajewski, P., & Shevlin, M. (2021). Adjustment disorder, traumatic stress, depression and anxiety in Poland during an early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1860356. doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1860356

- ECDC (2021). COVID-19 situation update for the EU/EEA, updated 8 July 2021. Solna Sweden: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

- Einsle, F., Köllner, V., Dannemann, S., & Maercker, A. (2010). Development and validation of a self-report for the assessment of adjustment disorders. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 15(5), 584–595. doi:10.1080/13548506.2010.487107

- Emami, A., Javanmardi, F., Pirbonyeh, N., & Akbari, A. (2020). Prevalence of underlying diseases in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Academic Emergency Medicine, 8(1), e35. PMID: 32232218.

- Fang, D., Thomsen, M. R., & Nayga, R. M. (2021). The association between food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–8. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10631-0

- Gao, J., Zheng, P., Jia, Y., Chen, H., Mao, Y., Chen, S., … Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One, 15(4), e0231924. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231924

- Gersons, B. P., Smid, G. E., Smit, A. S., Kazlauskas, E., & McFarlane, A. (2020). Can a ‘second disaster’during and after the COVID-19 pandemic be mitigated? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1815283. doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1815283

- Goel, N., Workman, J. L., Lee, T. T., Innala, L., & Viau, V. (2014). Sex Differences in the HPA Axis. In Comprehensive physiology (pp. 1121–1155). American Cancer Society. doi:10.1002/cphy.c130054

- González-Sanguino, C., Ausín, B., Castellanos, M. Á., Saiz, J., López-Gómez, A., Ugidos, C., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Mental health consequences during the initial stage of the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Spain. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 172–176. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.040

- Hall, R. C., Hall, R. C., & Chapman, M. J. (2008). The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: Lessons hospitals and physicians can apply to future viral epidemics. General Hospital Psychiatry, 30(5), 446–452. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.003

- Hatch, R., Young, D., Barber, V., Griffiths, J., Harrison, D. A., & Watkinson, P. (2018). Anxiety, Depression and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder after critical illness: A UK-wide prospective cohort study. Critical Care, 22(1), 310. doi:10.1186/s13054-018-2223-6

- Hertz-Palmor, N., Moore, T. M., Gothelf, D., DiDomenico, G. E., Dekel, I., Greenberg, D. M., … White, L. K. (2021). Association among income loss, financial strain and depressive symptoms during COVID-19: Evidence from two longitudinal studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 291, 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.054

- Ho, C. S., Chee, C. Y., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore, 49(1), 1–3.

- Hussain, A., Mahawar, K., Xia, Z., Yang, W., & Shamsi, E.-H. (2020). Obesity and mortality of COVID-19. Meta-analysis. Obesity Research & Clinical Practice, 14(4), 295–300. doi:10.1016/j.orcp.2020.07.002

- IMF. (2021). Policy responses to COVID-19. https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19#G

- Jahanshahi, A. A., Dinani, M. M., Madavani, A. N., Li, J., & Zhang, S. X. (2020). The distress of Iranian adults during the Covid-19 pandemic – More distressed than the Chinese and with different predictors. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 124–125. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.081

- Kazlauskas, E., Gegieckaite, G., Eimontas, J., Zelviene, P., & Maercker, A. (2018). A brief measure of the International Classification of Diseases-11 adjustment disorder: Investigation of psychometric properties in an adult help-seeking sample. Psychopathology, 51(1), 10–15. doi:10.1159/000484415

- Kazlauskas, E., Zelviene, P., Lorenz, L., Quero, S., & Maercker, A. (2017). A scoping review of ICD-11 adjustment disorder research. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup7), 1421819. doi:10.1080/20008198.2017.1421819

- Lages, N. C., Villinger, K., Koller, J. E., Brünecke, I., Debbeler, J. M., Engel, K. D., … Koppe, K. M. (2021). The relation of threat level and age with protective behavior intentions during COVID-19 in Germany. Health Education & Behavior, 48(2), 118–122. doi:10.1177/1090198121989960

- Lei, L., Huang, X., Zhang, S., Yang, J., Yang, L., & Xu, M. (2020). Comparison of prevalence and associated factors of anxiety and depression among people affected by versus people unaffected by quarantine during the COVID-19 epidemic in Southwestern China. Medical Science Monitor, 26. doi:10.12659/MSM.924609

- Liu, N., Zhang, F., Wei, C., Jia, Y., Shang, Z., Sun, L., … Liu, W. (2020). Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during COVID-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112921. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921

- Lorenz, L., Perkonigg, A., & Maercker, A. (2018). A socio-interpersonal approach to adjustment disorder: The example of involuntary job loss. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 9(1), 1425576. doi:10.1080/20008198.2018.1425576

- Lotzin, A., Aakvaag, H., Acquarini, E., Ajdukovic, D., Ardino, V., Böttche, M., … Schäfer, I. (2020). Stressors, coping and symptoms of adjustment disorder in the course of COVID-19 pandemic – The European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS) pan-European study. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/8XHYG

- Lotzin, A., Ketelsen, R., Zrnic, I., Lueger-Schuster, B., Böttche, M., & Schäfer, I. (2021). The Pandemic Stressor Scale – Factorial validity and reliability of a measure of stressors during a pandemic. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Mazza, C., Ricci, E., Biondi, S., Colasanti, M., Ferracuti, S., Napoli, C., & Roma, P. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Italian people during the COVID-19 pandemic: Immediate psychological responses and associated factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3165. doi:10.3390/ijerph17093165

- Mimoun, E., Ben Ari, A., & Margalit, D. (2020). Psychological aspects of employment instability during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S183. doi:10.1037/tra0000769

- Moghanibashi-Mansourieh, A. (2020). Assessing the anxiety level of Iranian general population during COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 102076. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102076

- Olagoke, A. A., Olagoke, O. O., & Hughes, A. M. (2020). Exposure to coronavirus news on mainstream media: The role of risk perceptions and depression. British Journal of Health Psychology, 25(4), 865–874. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12427

- Özdin, S., & Bayrak Özdin, Ş. (2020). Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: The importance of gender. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(5), 504–511. doi:10.1177/0020764020927051

- Perkonigg, A., Lorenz, L., & Maercker, A. (2018). Prevalence and correlates of ICD-11 adjustment disorder: Findings from the Zurich Adjustment Disorder Study. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 18(3), 209–217. doi:10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.05.001

- Pieh, C., O´Rourke, T., Budimir, S., & Probst, T. (2020). Relationship quality and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown. PLoS One, 15(9), e0238906. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0238906

- Pierce, M., McManus, S., Jessop, C., John, A., Hotopf, M., Ford, T., … Abel, K. M. (2020). Says who? The significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(7), 567–568. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6

- Polsky, J. Y., & Gilmour, H. (2020). Food insecurity and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Reports, 31(12), 3–11. doi:10.25318/82-003-x202001200001-eng

- Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 102066. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

- Rodríguez-Rey, R., Garrido-Hernansaiz, H., & Collado, S. (2020). Psychological impact and associated factors during the initial stage of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic among the general population in Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01540

- Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Mensi, S., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., … Di Lorenzo, G. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790

- Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., Marco, A. D., … Olff, M. (2021). Trauma-spectrum symptoms among the Italian general population in the time of the COVID-19 outbreak. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1855888. doi:10.1080/20008198.2020.1855888

- Sawalha, A. H., Zhao, M., Coit, P., & Lu, Q. (2020). Epigenetic dysregulation of ACE2 and interferon-regulated genes might suggest increased COVID-19 susceptibility and severity in lupus patients. Clinical Immunology, 215, 108410. doi:10.1016/j.clim.2020.108410

- Sherman, A. C., Williams, M. L., Amick, B. C., Hudson, T. J., & Messias, E. L. (2020). Mental health outcomes associated with the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence and risk factors in a southern US state. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113476. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113476

- Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Ben-Ezra, M., Karatzias, T., Cloitre, M., Vallières, F., … Maercker, A. (2020). Measuring ICD-11 adjustment disorder: The development and initial validation of the International Adjustment Disorder Questionnaire. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 141(3), 265–274. doi:10.1111/acps.13126

- Solar, O., & Irwin, A. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

- Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Pastore, M., & Fasolo, M. (2020). Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713

- Sun, Y., Wu, Y., Bonardi, O., Krishnan, A., He, C., Boruff, J. T., … Li, K. (2021). Comparison of mental health symptoms prior to and during COVID-19: Evidence from a living systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- Taylor, S. (2019). The psychology of pandemics: Preparing for the next global outbreak of infectious disease. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Van Hees, S., Siewe Fodjo, J. N., Wijtvliet, V., Van den Bergh, R., Faria de Moura Villela, E., da Silva, C. F., … Colebunders, R. (2020). Access to healthcare and prevalence of anxiety and depression in persons with epilepsy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicountry online survey. Epilepsy & Behavior, 112, 107350. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107350

- Veer, I. M., Riepenhausen, A., Zerban, M., Wackerhagen, C., Puhlmann, L. M. C., Engen, H., … Kalisch, R. (2021). Psycho-social factors associated with mental resilience in the Corona lockdown. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–11. doi:10.1038/s41398-020-01150-4

- Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., McIntyre, R. S., … Ho, C. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2020.04.028

- Wang, Y., Kala, M. P., & Jafar, T. H. (2020). Factors associated with psychological distress during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on the predominantly general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(12), e0244630. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0244630

- Weathers, F. W., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) with Criterion A. Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assess-ment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp

- Wheaton, M. G., Abramowitz, J. S., Berman, N. C., Fabricant, L. E., & Olatunji, B. O. (2012). Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36(3), 210–218. doi:10.1007/s10608-011-9353-3

- White, I. R., Royston, P., & Wood, A. M. (2011). Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine, 30(4), 377–399. doi:10.1002/sim.4067

- WHO. (2021). ICD-11 - mortality and morbidity statistics. Retrieved from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f991786158

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., … McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

- Zhang, Y., & Ma, Z. F. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2381. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072381