ABSTRACT

Background: In June 2021, 40 years have passed since the first cases of HIV infection were detected. Nonetheless, people living with HIV (PLWH) still suffer from intense HIV-related distress and trauma, which is nowadays mostly linked to the still-existing stigmatization of PLWH.

Objectives: The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the association between HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being among PLWH. We also explored whether this association varies as a function of sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as well as study publication year and stigma measurement.

Method: A structured literature search was performed on Web of Science, Scopus, PsyARTICLES, MedLine, ProQuest, and Google Scholar databases. The inclusion criteria were quantitative, peer-reviewed articles published in English between 1996 and 2020.

Results: After selection, 64 articles were accepted for further analysis (N = 25,294 participants). The random-effects pooled estimate revealed an overall negative and medium-strength association between stigma and well-being (r = −.31, 95% CI [−.35; −.26]). The participants’ age modified this effect with a stronger association for older PLWH. Other sociodemographic and clinical variables as well as publication year and stigma measurement did not explain the variation in association between stigma and well-being across studies.

Conclusions: The present meta-analysis and systematic review not only showed an expected negative relationship between stigma and well-being but also revealed a substantial heterogeneity between studies that suggests a strong role of context of a given study. This finding calls for more advanced theoretical and analytical models to identify protective and vulnerability factors to effectively address them in clinical practice and interventions.

HIGHLIGHTS

In this meta-analysis, the relationship between HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being of people living with HIV was investigated.

Antecedentes: En junio de 2021 pasaron cuarenta años desde que fueron detectados los primeros casos de infección por VIH. No obstante, las personas que viven con el VIH (PVCV) todavía sufren de angustia intensa y trauma relacionados con el VIH, que en la actualidad se vinculan principalmente con la estigmatización aún existente de las PVCV.

Objetivos: El propósito de esta revisión sistemática y metanálisis fue examinar la asociación entre el estigma del VIH/SIDA y el bienestar psicológico entre las PVCV. También exploramos si esta asociación varía en función de las características sociodemográficas y clínicas, así como del año de publicación del estudio y la medición del estigma.

Método: Se realizó una búsqueda estructurada de literatura en las bases de datos Web of Science, Scopus, PsyARTICLES, MedLine, ProQuest y Google Scholar. Los criterios de inclusión fueron artículos cuantitativos, revisados por pares, publicados en inglés entre 1996 y 2020.

Resultados: Después de la selección, se aceptaron 64 artículos para análisis adicionales (N = 25.294 participantes). La estimación combinada de efectos aleatorios reveló una asociación general negativa y de intensidad media entre el estigma y el bienestar (r = −.31, IC del 95% [−.35; −.26]). La edad de los participantes modificó este efecto con una asociación más fuerte para las PVCV mayores. Otras variables sociodemográficas y clínicas, así como el año de publicación y la medición del estigma, no explicaron una variación de la asociación entre el estigma y el bienestar entre los estudios.

Conclusiones: El presente metanálisis y revisión sistemática mostró una relación negativa esperada entre el estigma y el bienestar, pero también reveló una heterogeneidad sustancial entre los estudios que sugiere un papel importante del contexto de cada estudio dado. Este hallazgo requiere modelos teóricos y analíticos más avanzados para identificar factores protectores y de vulnerabilidad, para abordarlos de manera efectiva en la práctica clínica y las intervenciones.

背景: 2021 年 6 月, 距离发现第一例 HIV 感染病例已经过去了 40 年。尽管如此, HIV感染者 (PLWH) 仍然遭受着强烈的HIV相关痛苦和创伤, 如今这主要与仍然存在的 PLWH 污名化有关。

目的: 本系统综述和元分析旨在考查PLWH 中HIV/AIDS污名与心理幸福感之间的关联。我们还探讨了这种关联是否因社会人口统计学和临床特征以及研究发表年份和污名测量而异。

方法: 在 Web of Science, Scopus, PsyARTICLES, MedLine, ProQuest 和 Google Scholar 数据库上进行了结构化文献搜索。纳入标准是 1996 年至 2020 年间以英文发表的同行评审的定量文章。

结果: 筛选之后, 纳入了64 篇文章进行进一步分析 (N = 25,294 名参与者) 。随机效应汇总估计显示, 污名和幸福感之间总体呈中强度负相关 (r = −.31, 95% CI [−.35; −.26]) 。参与者的年龄调节了这种效应, 年龄更大的 PLWH 有更强的关联。其他社会人口统计学和临床变量以及出版年份和污名测量并不能解释跨研究的污名和幸福感之间关联的变异。

结论: 本元分析和系统综述表明, 污名和幸福感之间存在预期的负相关关系, 但也揭示了研究之间的巨大异质性, 这表明给定研究背景的重要作用。这一发现需要更先进的理论和分析模型来识别保护和易感因素, 以便在临床实践和干预中有效解决这些问题。

PALABRAS CLAVE:

关键词:

1. Introduction

In June 2021, 40 years have passed since the first cases of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection were detected and described by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC, Citation1981), resulting in a previously unknown disease, Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). Since its discovery, enormous progress in HIV treatment has changed this disease from a terminal to a chronic medical problem (Carrico et al., Citation2019). As a result, the current average life expectancy of people living with HIV (PLWH) does not differ significantly from the life expectancy of the general population (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV-AIDS; UNAIDS, Citation2019). Furthermore, several recent studies have shown that psychosocial variables outweighed the medical parameters as predictors and correlates of psychological well-being (PWB) of PLWH (e.g. Cooper, Clatworthy, Harding, Whetham, & Consortium, Citation2017; Rzeszutek, Gruszczyńska, & Firląg-Burkacka, Citation2018). However, PLWH still suffer from intense HIV-related distress and consistently report a much poorer well-being level when compared to patients suffering from other chronic illnesses (Cooper et al., Citation2017). According to several meta-analyses, this paradoxical situation is linked to the still-existing stigmatization of PLWH, whose explicit manifestations have changed, although its overall level remains relatively similar to the beginning of the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Rueda et al., Citation2016). In particular, HIV/AIDS stigma is perceived by PLWH as the main source of distress among PWB (Rendina, Brett, & Parsons, Citation2018) and is still the greatest barrier to effective coping with the HIV epidemic in health care worldwide (UNAIDS, Citation2019). However, despite a plethora of studies on HIV/AIDS stigma, contemporary research on this topic demonstrates theoretical and methodological limitations and several research areas in this field remain unexplored (Fazeli & Turan, Citation2019). The latter fact precludes us still from the thorough understanding on how HIV/AIDS stigma deteriorates PLWH’s well-being.

From its beginnings, the definition of HIV/AIDS stigma posed a great challenge for researchers (Crawford, Citation1996; Rueda et al., Citation2016). The difficulties in operationalizing the aforementioned term stemmed from the interaction of two layers of this type of stigma, encompassing the internal, traumatic character of HIV/AIDS itself, as well as the external, socio-cultural issues. On the one hand, diagnosis and life with potentially fatal somatic disease is a very strong stressor, which from the fourth edition of DSM was classified as an event meeting the criterion of a traumatic stressor, leading even to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation1994; Cordova, Riba, & Spiegel, Citation2017; Kangas, Henry, & Bryant, Citation2005). The disease that has the consequences described above is HIV/AIDS, since roughly 28% to even 64% of HIV-infected people meet the diagnostic criteria of PTSD (Sherr et al., Citation2011; Tang et al., Citation2020). However, PTSD symptoms accompanying PLWH have a complex aetiology and variable dynamics. Although they are usually initiated by the moment of diagnosis, they also result from a later struggle with such a disease, constant awareness of the real-life threat, treatment side effects and especially strong social stigma (Neigh et al., Citation2016). In other words, trauma experienced by PLWH applies not only to the past (see diagnosis) but it is also an ongoing process induced by internal (somatic) and external factors (stigma) related to the present and/or future life of these patients. The latter fact provoked plenty of controversial discussion on applying the diagnosis of PTSD to PLWH (Kagee, Citation2008). On the other hand, HIV/AIDS stigma is rooted also in socio-cultural factors engaged in stereotyping and discriminating against PLWH, which mirrored existing inequalities in class, race, gender, and sexuality (Parker & Aggleton, Citation2003). Taking this complexity of the stigmatization process of PLWH into account, research on HIV/AIDS stigma lacks a theoretical model that provides not only a clear definition of HIV/AIDS stigma but additionally proposes definitive mechanisms by which stigma exerts its deteriorating effects on the lives of PLWH. Instead, many studies are based on some global and even atheoretical (built ad hoc) HIV/AIDS stigma index, devoid of differentiating distinct mechanisms of this stigma and their unique association with the domains of functioning of PLWH (Rueda et al., Citation2016). One exception is the HIV Stigma Framework by Earnshaw and Chaudoir (Citation2009), which underscores a number of HIV stigma mechanisms that are distinct psychological responses to the knowledge that PLWH have about their HIV/AIDS status. More specifi-cally, the HIV Stigma Framework distinguishes three mechanisms of stigmatization experienced by PLWH: internalized, anticipated, and enacted HIV/AIDS stigma. According to Earnshaw and Chaudoir (Citation2009), differentiating between these three mechanisms of HIV/AIDS stigma is critical to foster understanding of how HIV/AIDS stigma affects the lives of PLWH, as each of these stigma mechanisms may have a unique impact on psychological, social, and physical components of health and well-being in this patient group (Earnshaw, Rosenthal, & Lang, Citation2016; Earnshaw, Smith, Chaudoir, Amico, & Copenhaver, Citation2013). However, this model was criticized as the data for it were obtained only in cross-sectional studies, without control of other possible pathways of such relationships, and the conceptualization of its outcome components (i.e. health and well-being) was rather poorly based on the current understanding of these constructs in psychology (Misir, Citation2015).

The methodological shortcomings of the majority of studies devoted to HIV/AIDS stigma pertain to either a cross-sectional design using self-report questionnaires or, less commonly, a longitudinal design also using solely classic psychometric questionnaires (Logie & Gadalla, Citation2009; Rueda et al., Citation2016; Smith, Rossetto, & Peterson, Citation2008). These kinds of procedures not only preclude causal interpretations but also prevent grasping the processual aspect of struggling with HIV/AIDS stigma among PLWH. Experiencing HIV/AIDS stigma is a dynamic process, and more advanced methods are necessary to capture the trajectories of this process in longer and shorter temporal perspectives, which may lead to different conclusions (Rendina et al., Citation2018). A paucity of studies control for distinct levels of HIV/AIDS stigma, that is, most do not account for the mechanism of stigma accumulation via the minority stress theory (Meyer, Citation2003). More specifically, it has been observed that HIV/AIDS stigma may be intensified among sexual and gender minorities (e.g. lesbian, gay, and bisexual PLWH), who are significantly affected by the HIV epidemic (Cramer, Burks, Plöderl, & Durgampudi, Citation2017). To be sure, not every person infected with HIV is a sexual or gender minority, but those who are may be prone to stigma accumulation (Cramer et al., Citation2017). It has been documented in several studies that PLWH who belong to sexual and gender minorities have even lower well-being and worse health than the general population of HIV/AIDS patients (Rendina et al., Citation2018; Rendina, Weaver, Millar, López-Matos, & Parsons, Citation2019). To further complicate the topic, it must be taken into account that the gender and ethnicity of PLWH may affect stigma accumulation. Specifically, HIV-infected women have reported a lower quality of life, more intense HIV-related stigma, and higher rate of associated mental problems (Machtinger, Wilson, Haberer, & Weiss, Citation2012). The same process of stigma accumulation has also been observed among PLWH representing ethnic minorities (Logie, Ahmed, Tharao, & Loutfy, Citation2017). Thus, a negative synergistic effect of being a minority in any of these three areas, gender, sexual orientation, and ethnicity, may be observed although it is yet to be tested.

Finally, as previously mentioned, HIV/AIDS stigma was predominantly examined in the context of the negative aspects of the functioning of PLWH, searching for both stigma correlates and consequences (e.g. Logie & Gadalla, Citation2009; Rueda et al., Citation2016). However, such a broad scope of analysed variables, ranging from mental and physical health to risk behaviours, access to health care services, and overall social functioning, has led to ambiguous conclusions (Rendina et al., Citation2019). More integrative work with a particular focus on the well-being of PLWH and other factors clearly defined as potential moderators should bring more conclusive results in identifying how well-being is related to stigma and what modifies this relationship.

2. Objectives of the current study

Taking the aforementioned issues into consideration, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to synthesize, analyse, and critically review existing studies on the association between HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being among PLWH. We followed the broad operationalization of well-beingin particular, quality of life and health-related quality of life, satisfaction with life, and affective components.

Moreover, in the meta-analytic portion, we aimed to evaluate the overall strength and direction of this relationship and searched for its possible moderators, including year of study publication, operationalization of stigma, and the most crucial sociodemographic (i.e. participant age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, employment, education, and relationship status) and clinical variables (time since HIV diagnosis, AIDS status, CD4 count, and viral load). We also examined the possibility of HIV/AIDS stigma accumulation, paying specific attention to a potential synergistic effect of moderators such as sexual and gender minority status, gender, and ethnicity.

3. Method

3.1. Search strategy and inclusion/exclusion criteria

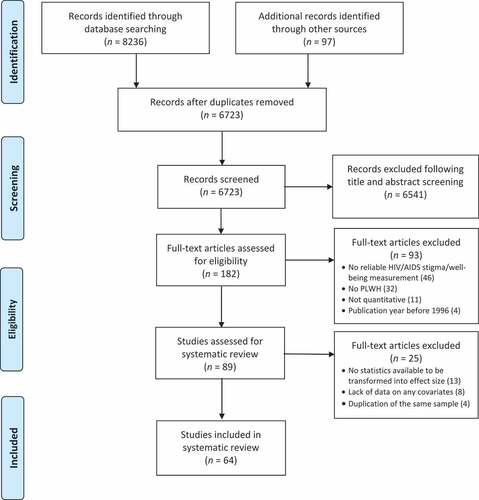

The literature search and review were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009; see also ). A search was performed on 12 December 2020, in the following databases: Web of Science, Scopus, PsyARTICLES, MedLine, ProQuest, and Google Scholar (this was treated as an additional source of grey literature; Bellefontaine & Lee, Citation2014). The Boolean query had the following form: (HIV OR AIDS OR (acquired AND immunodeficiency AND syndrome) OR (human AND immunodeficiency) OR PLWH OR PLWHA OR HIV/AIDS OR SIDA) AND (stigma* OR (HIV-stigma) * OR (HIV/AIDS-stigma) AND (well-being OR wellbeing OR (well AND being) OR (life AND satisfaction) OR life-satisfaction OR (life AND quality) OR life-quality). We searched only for papers written in English and published between January 1996 (indicating the advent of combination antiretroviral therapy [Antiretroviral Therapy; ART]) and December 2020. This specific time span was also applied in other meta-analyses on HIV/AIDS stigma (Logie & Gadalla, Citation2009; Rueda et al., Citation2016) and was motivated by the fact that in 1996, HIV/AIDS evolved from a terminal to a chronic medical condition as a result of the introduction of ART, which result in differences in the role of HIV/AIDS stigma on the psychosocial functioning of PLWH compared to the era before ART (Logie & Gadalla, Citation2009).

In addition to the English-language criterion, the studies had to meet the following criteria to be included in the systematic review and subsequently in the meta-analysis:

(1) Type of study: We included only peer-reviewed, quantitative, empirical articles that measured the relationship between HIV/AIDS-related stigma and well-being outcomes among PLWH. We excluded other systematic reviews or meta-analyses, editorials, letters, and qualitative reports.

(2) Participants: We included studies conducted on HIV/AIDS patients, with no restriction on gender, age, sexual orientation, disease stage, or ethnicity. We also included studies in which participants were composed of PLWH and patients with other chronic illnesses. We excluded studies that focused on caregivers or family members of PLWH.

(3) Methodology: We included only studies with psychometrically sound measurements of HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being outcomes and reported any one of the following statistics: correlation coefficients and sample sizes, regression coefficients, or other statistics that could be transformed into a standardized effect size. We excluded studies with no psychometric HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being measurements (i.e. studies with ad hoc author-created scales/items) and studies without sufficient statistics to compute a standardized effect size, even after contacting authors.

(4) Quality of study: We followed the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (Feng et al., Citation2014), which consists of 14 criteria and requires the evaluator to answer whether the study in question meets the particular criterion. Studies were rated by three independent evaluators (see Results and ). They paid special attention to whether the study used a clear definition of HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being outcomes, used validated measures with psychometric data, controlling for sociodemographic and clinical covariates, and provided data to calculate effect sizes. Additionally, the articles, especially those by the same authors, were checked to ensure that they did not use an identical sample of participants more than once. If this was the case, only one of them was included in the final analysis.

3.2. Statistical analysis

As the majority of studies used the global HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being index, analysis was performed on such global indicators. If more than one dimension of HIV/AIDS stigma (i.e. internalized stigma, anticipated stigma, or enacted stigma) was considered in the study, the result with the highest strength of association with the outcome was selected (Rueda et al., Citation2016).

Meta-analysis was performed with the use of library ‘meta’ in the R Statistics 4.03 software environment (Schwarzer, Citation2007) and Pearson’s correlation coefficients for effect size measures. The unstandardized and standardized regression coefficients obtained from single studies, after adjustment for having the same direction regardless of the measurement method, were transformed to Pearson’s correlation coefficients following formulas provided by Lipsey and Wilson (Citation2001) with the use of library ‘esc.’ A random effects model was implemented, assuming heterogeneity of the effect size between studies because the studies do not stem from one population. The DerSimonian–Laird estimator of the variance of the distribution of true effect sizes was used. Heterogeneity in true effect sizes between studies was evaluated by Cochran’s Q statistics (distributed as a chi-square statistic with number of studies minus 1 degrees of freedom) and I2 statistics (Higgins, Thompson, Deeks, & Altman, Citation2003). Outliers’ diagnostics were based on Baujat plot (Baujat, Mahé, Pignon, & Hill, Citation2002) and Graphic Display of Heterogeneity (GOSH) plot (Olkin, Dahabreh, & Trikalinos, Citation2012) analysis. Publication bias was assessed with a contour-enhanced funnel plot (Peters, Sutton, Jones, Abrams, & Rushton, Citation2008). The potential moderators of the effect size were analysed with meta-regression (Viechtbauer, Citation2010).

4. Results

4.1. Identification, screening, and eligibility

Initially, 8,333 titles and abstracts were gathered through electronic databases, including 5,452 from MedLine, 1,402 from Web of Science, 781 from ProQuest, 582 from Scopus, 19 from PsyARTICLES, and 97 from Google Scholar, which was treated as an additional database source. After removing duplicates, 6,723 potentially eligible records remained for further screening. Careful title and abstract screening performed by three independent reviewers garnered 182 full articles for assessment, and 118 of them were eliminated after applying the exclusion criteria. Finally, 64 articles were accepted for further analysis. The details of the selection process are presented in in a PRISMA flow diagram.

Regarding the year of publication, the majority of studies were published in the last five years. Included study publication years are as follows: 2020 (9 articles, 14% of all); 2019 (7 articles, 11% of all); 2018 (7 articles, 11% of all); 2017 (7 articles, 11% of all); and 2016 (5 articles, 8% of all). In the remaining analysed years, one to three articles from each year were eligible, with the exception of 2013, which had seven articles, accounting for 10% of all analysed. The total sample size was N = 25,294 PLWH, including 14,590 males, 10,682 females, and 22 participants who chose the ‘other’ option regarding sex. 92% (59 out of 64) of analysed studies were cross-sectional in design. Finally, as far as the study settings are concerned (i.e. country), more than half (51%; 33 out of 64) of the eligible studies have been conducted in the USA. About 15% (10 out of 64) have been carried out in Asian regions (e.g. China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Vietnam), 7% (5 out of 64) in European countries, 7% in African countries (5 out of 64), 4% (3 out of 64) in Canada. The rest of the studies came from other parts of the world, such as Australia, India, Iran and Indonesia.

The eligible studies used various measures to assess the HV/AIDS stigma, but the most common were the Berger HIV Stigma Scale (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, Citation2001), the Internalized HIV Stigma instrument (Sayles et al., Citation2008), the Barriers to Care Scale (Heckman, Somlai, Kelly, Stevenson, & Galdabini, Citation1996), the HIV Stigma Framework Scale (Earnshaw & Chaudoir, Citation2009), and the HIV Stigma Measure (Sowell et al., Citation1997). With respect to well-being measures, quality of life was evaluated most commonly by the WHOQOL-HIV BREF (WHOQOL Group, Citation1995), the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36-Item Health Survey (Stewart, Hays, & Ware, Citation1988), and the HIV/AIDS Targeted Quality of Life instrument (Holmes & Shea, Citation1998). Life satisfaction was assessed almost exclusively by the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, Citation1985). The other components of psychological well-being were evaluated primarily by the Psychological Well-Being Scale (Ryff, Citation1989) as well as the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, Citation1988). summarizes the details of the 64 selected articles.

Table 1. Summary of literature investigating association between HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being among people living with HIV

4.2. Meta-analysis: association between HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being outcomes

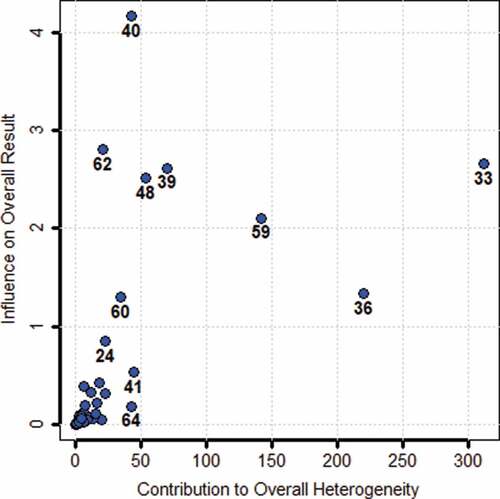

4.2.1. Diagnosis of outliers and influencing cases

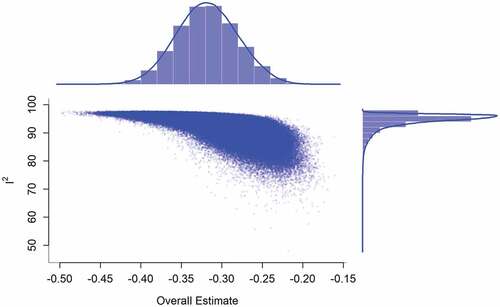

Possible outliers and influencing cases, that is, studies yielding observed effects outlying or well-separated from the rest of the data, were identified with a Baujat plot. Results of the Baujat plot are depicted in . The plot shows the contribution of each study to the overall Q-test statistic for heterogeneity on the horizontal axis versus the influence of each study on the overall result on the vertical axis. As can be seen, especially in the case of Study 33 (i.e. Miller et al., Citation2016), some studies appeared to contribute heavily to overall heterogeneity and, as such, may have a strong influence on the overall results. However, since careful inspection of this study did not identify any specificity, we decided to conduct GOSH plot analysis to further detect outliers and influential studies. In , the pooled effect size is presented on the x-axis and the between-study heterogeneity on the y-axis. As seen, the obtained model formed a unimodal distribution, with domination of high between-study heterogeneity. Since graphical analysis showed no multimodality, we decided not to remove any study from the subsequent analyses.

4.2.2. Publication bias

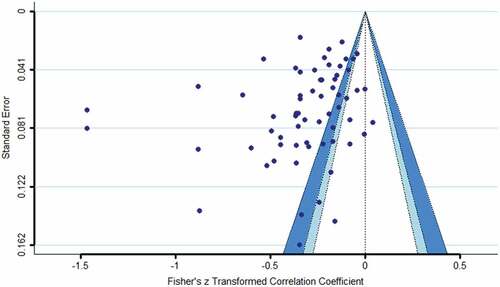

The potential publication bias effect was examined with a contour-enhanced funnel plot. The results are depicted in , which shows that in general, small studies appear to be under-represented in the areas of both high and no statistical significance. Thus, although publication bias cannot be excluded, this may suggest that the observed asymmetry is caused by other factors, such as the real absence of smaller studies due to their known insufficient power to detect the effect in question. The mean sample size of the studies included in the meta-analysis is 392.22 (SD = 499.89), ranging from 41 to 2987, and 14% of studies had a sample size below 100 participants. Additionally, sample characteristics as well as study quality, not only statistical significance, may favour publication of larger studies.

Figure 4. Heterogeneity diagnostics using a contour-enhanced funnel plot. The effects in the white zone are greater than p = .10; the effects in the adjacent light blue zone are between p = .10 and p = .05; the effects in the darker blue zone are between p = .05 and p = .01; the effects outside this zone are smaller than p = .01

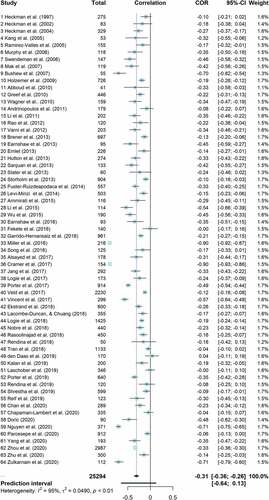

4.2.3. Effect sizes and heterogeneity

The effect sizes for individual studies ranged from −.90 to .04 and overlap in the confidence interval was minimal (). This heterogeneity was significant, (Q(63) = 1242.65, p < .001, I2 = 94.9% [94.1%; 95.6%]), indicating that 95% of the total variation in estimated effects was due to between-study variation, which was considered to be high (Higgins et al., Citation2003). The random-effects pooled estimate revealed a negative and medium-size (Cohen, Citation1988) association between stigma and subjective well-being (r = −.31, 95% CI [−.36; −.26]). However, a 95% prediction interval [−.77; .13] informing on the range of true effects in similar future studies suggests that this association may be from negative to null or even slightly positive (IntHout, Ioannidis, Rovers, & Goeman, Citation2016).

4.2.4. Moderators

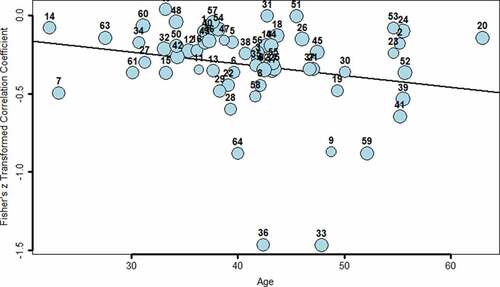

In the next step, possible moderators of the obtained effect size were examined through meta-regression. They included publication year, operationalization of stigma, and sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. There was no evidence of variation in the effect size due to publication year (B = −.01, p > .05) or the Berger’s scale versus other tools to assess stigma (B = .03, p > .05). The observed effect size also did not change with percentage of male participants in the study (B = −.06, p > .05), being in a stable relationship (B = .04, p > .05), higher education (B = −.09, p > .05), or stable employment (B = .06, p > .05). Similarly, statistically insignificant results were noted for the percentage of participants with heterosexual orientation (B = .01, p > .05) and Caucasian ethnicity versus other ethnicities (B = −.16, p > .05). For clinical variables, all the effects were insignificant, including mean viral load (B = .21, p > .05), mean time since diagnosis (B = −.01, p > .05), and AIDS status (B = −.08, p > .05). Thus, only two moderators were identified: mean age of the participants, (B = −.01, p < .05) and mean CD4 count (B = −.01, p < .05). However, values for CD4 count became insignificant when controlled for participant age. Thus, mean age of the participants was the only significant moderating variable, modifying the stigma-well-being effect, which is presented in using a bubble plot with a circle size proportional to the weight of the individual studies. As seen, the negative relationship between stigma and subjective well-being was stronger for older participants. Nonetheless, mean participant age in the individual studies explained 9.4% of the variation, with still significant heterogeneity of the effect size between stigma and well-being across the studies (Q(62) = 1103.08, p < .001).

Figure 6. Moderating effect of mean participants’ age on the relationship between HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being of PLWH. The circle sizes are proportional to the weights of individual studies in the meta-analysis. The numbers of the studies correspond to the numbers assigned in

Additionally, we verified if stigma accumulation, defined as an interaction of being female, other than heterosexual and other than Caucasian, affected the stigma well-being effect, but this interaction as well as all two-way interactions were insignificant.

5. Summary of main findings and discussion

The aim of this study was to examine and critically review the relationship between HIV/AIDS stigma and PWB among PLWH. After the selection process, 64 articles were determined as having met the criteria and the publication range (between 1997 and 2020). They were subsequently analysed for content and quality, and the reported effect sizes were investigated by meta-analysis. Despite high variability in the operationalization of both HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being, we noticed a pattern indicating a negative relationship of medium strength between these two constructs, with the random-effects pooled estimate equalling −.31 ( and ). However, high between-study heterogeneity was noted, with possible null future effects. This raised the question of publication bias, but the relevant analysis showed no evidence of this. In addition, the publication year did not explain the between-study effect heterogeneity, which may suggest that despite more than two decades of implementation of ART, the strength of the relationship between stigma and the well-being of PLWH remains quite stable.

This corresponds to the observations made by Rendina et al. (Citation2018, Citation2019) that although the manifestations of HIV/AIDS stigma have changed at the individual and societal levels, its overall effect on the well-being of people with HIV/AIDS is the same as at the beginning of the epidemic. Historically, this result has indicated both a widespread overestimation of past effects and an underestimation of current effects, which may have important implications for clinical practice. On the other hand, it can also be a sign that despite 40 years of great medical progress in treating HIV/AIDS, PLWH still experience their HIV+ status as a highly traumatizing factor (Neigh et al., Citation2006; Tang et al., Citation2020).

As for sociodemographic covariates, eleven out of twelve eligible studies pointed to elevated stigma and much worse well-being among older PLWH. In meta-analysis, age was identified as the only significant moderator of effect size, with older adults having a stronger negative relationship between stigma and well-being. Currently, HIV has been increasingly diagnosed among older adults (UNAIDS, Citation2019). The poorer quality of life among them has been found to be a derivative of not only comorbid health conditions that are increased by age (Heckman et al., Citation2002) but also experienced stigma, which indicates a double jeopardy (i.e. HIV/AIDS stigma and ageism; Emlet, Citation2006; Emlet, Fredriksen-Goldsen, & Kim, Citation2013). As such, this constitutes a special case of stigma accumulation and the only case obtained in our study.

For other possible areas of HIV/AIDS stigma accumulation, namely, gender (being female), sexual and gender minority (other than heterosexual), and ethnicity (other than Caucasian), not only was an interaction effect insignificant but also no main effects were noted. This indicates that the strength and direction of the relationship between stigma and well-being were not modified by a combination of the aforementioned characteristics. However, the systematic review highlighted a more complex picture, as ten out of fifteen eligible studies in this context indicated a higher HIV/AIDS stigma and significantly poorer well-being among female PLWH compared to male PLWH; yet four studies found the opposite trend (Earnshaw et al., Citation2016; Jang & Bakken, Citation2017; Parcesepe et al., Citation2020) and one study showed that male PLWH suffered more from some components of stigma than females (loneliness), although it did not account for gender differences in well-being (Vincent et al., Citation2017). In addition, in six out of seven eligible studies, PLWH representing sexual and gender minorities (i.e. lesbian, gay, and bisexual) experienced higher stigma and declared substantially lower quality of life compared to heterosexual PLWH. Only Nguyen et al. (Citation2020) found higher well-being among PLWH representing sexual and gender minorities compared to heterosexual PLWH, although there was no significant difference in the stigma level between these two groups. Furthermore, in six out of nine eligible studies, African and/or African American PLWH reported higher stigmatization and lower well-being compared to PLWH of Caucasian ethnicity, although Heckman et al. (Citation2002) and Earnshaw et al. (Citation2013) observed the reverse and Kang, Rapkin, Remien, Mellins, and Oh (Citation2005) found the lowest well-being and the highest stigma among Asian PLWH. However, in all of these studies, the moderating effect of sociodemographic variables was tested directly, which showed a low theoretical advancement of the studies on stigma thus far.

Similarly, employment, education, and marital status also had some associations with both stigma and well-being in single studies, but they were not verified as moderators. During meta-analysis, they did not modify the effect size, thus a protecting role of these factors against the negative consequences of stigma on well-being is not as universal as is often assumed (Cooper et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2008). For instance, Jang & Bakken, (Citation2017), Nobre, Pereira, Roine, Sutinen, and Sintonen (Citation2018), and Kalan et al. (Citation2019) observed that higher education sometimes increases perceived stigma and, in turn, deteriorates the well-being of PLWH. In addition, two studies in our review conducted on women with HIV in India showed that married women experienced higher HIV/AIDS stigma and worse well-being than those who were single (Ekstrand et al., Citation2018; Garrido-Hernansaiz, Heylen, Bharat, Ramakrishna, & Ekstrand, Citation2016).

For clinical covariates, such as CD4, viral load, time since diagnosis and treatment, and AIDS status, we are very cautious in reaching certain conclusions, as the majority of reviewed studies did not include these variables or if they did, CD4 count and viral load status were based on self-assessment only. Nonetheless, the overall trend indicated by meta-analysis was that the negative relationship between stigma and well-being was stronger among PLWH with a higher CD4 count. This suggests that the psychological context of being infected with HIV, expressed by the association between stigma and well-being, is more pronounced for people in better health condition. This is understandable, as, in the presence of poor health, stigma may be experienced differently and have less impact on general well-being. However, this effect became zero after including the participants’ mean age in the analysis, implying a possible interdependence between age and self-reported CD4.

5.1. Limitations and future research directions

Our systematic review and meta-analysis revealed a strong heterogeneity among the studies, thus despite clear selection criteria, thorough assessment of the methodological and statistical quality of eligible articles by independent reviewers, and established methods to aggregate the study results, we must specify several limitations of the obtained findings. First, we included only published studies in the English language. Both unpublished studies and studies published in different languages may bring different results, particularly as stigma, its internalization, and its social expression can be strongly rooted in cultural context (Liamputtong, Citation2013). Second, even if we did not observe the effect of the tool in measuring stigma, it was limited to the comparison of the most popular Berger’s scale with other questionnaires, sometimes developed ad hoc for the purpose of a given study, where different aspects of stigma without a relevant psychometric evaluation were aggregated into a global stigma index. This illuminates the fundamental problem of the lack of a conclusive theoretically and empirically validated model of HIV/AIDS stigma in the literature. Specifically, as was already mentioned, research on HIV/AIDS stigma lacks a theoretical model that provides not only a clear definition of HIV/AIDS stigma but additionally proposes definitive mechanisms by which stigma exerts its deteriorating effects on the lives of PLWH. Instead, many studies are based on some global and even atheoretical (built ad hoc) HIV/AIDS stigma index, devoid of differentiating distinct mechanisms of this stigma and their unique association with the domains of functioning of PLWH. Even wider heterogeneity of well-being operationalization forced us to abandon a similar analysis for well-being, instead of using this term as an umbrella concept. Thus, it cannot be excluded that for separate dimensions of well-being, the obtained effect may differ substantially. Third, 92% of reviewed studies were cross-sectional and adopted only elementary statistical analysis with control for relatively scarce covariates. As such, more longitudinal studies are critical for understanding HIV/AIDS stigma mechanisms, with more advanced models that include its potential mediators and moderators. Thus, future research on HIV/AIDS stigma and well-being should be of better quality and go beyond the basic description of the relationship into more explanatory models. Finally, the vast majority of reviewed studies came from the USA region, which reflects the dominance of the USA studies in HIV/AIDS stigma research. This latter fact calls for the need for more research on stigma in other geographical regions, representing culturally versatile samples of PLWH in the future.

6. Conclusions

The present meta-analysis and systematic review not only indicate an expected negative relationship between stigma and well-being but also reveal a substantial heterogeneity between studies that suggests a strong role of context of a given study. This context may include not only functional characteristics of the participants (e.g. being a minority) but also differences in structural stigma at both local and national levels (Hatzenbuehler, Citation2016). Thus, future study designs require more advanced theoretical and analytical models to identify protective and vulnerability factors to improve the ability to address them in clinical practice and interventions for PLWH.

Information about data sharing

Data are available in Supplementary Information.

Research involving human participants

The study protocol was accepted by the institutional ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation in the study.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abboud, S., Noureddine, S., Huijer, H., Dejong, J., & Mokhbat, J. (2010). Quality of life in people living with HIV/AIDS in Lebanon. AIDS Care, 22, 687–24. doi:10.1080/09540120903334658

- Alsayed, N., Sereika, S., Albrecht, S. A., Terry, M., & Erlen, J. (2017). Testing a model of health-related quality of life in women living with HIV infection. Quality of Life Research, 26, 655–663. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1482-4

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Ammirati, R., Lamis, D., Campos, P., & Farber, E. (2015). Optimism, well-being, and perceived stigma in individuals living with HIV. AIDS Care, 27, 926–933. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1018863

- Andrinopoulos, K., Clum, G., Murphy, D. A., Harper, G., Perez, L., Xu, J., … Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2011). Health related quality of life and psychosocial correlates among HIV-infected adolescent and young adult women in the US. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23, 367–381. doi:10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.367

- Baujat, B., Mahé, C., Pignon, J.-P., & Hill, C. (2002). A graphical method for exploring heterogeneity in meta-analyses: Application to a meta-analysis of 65 trials. Statistics in Medicine, 21, 2641–2652. doi:10.1002/sim.1221

- Bellefontaine, S., & Lee, C. (2014). Between Black and White: Examining grey literature in meta-analyses of psychological research. Journal of Child and Families Studies, 23, 1378–1388. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9795-1

- Berger, B., Ferrans, C., & Lashley, F. (2001). Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health, 24, 518–529. doi:10.1002/nur.10011

- Brener, L., Callander, D., Slavin, S., & De Wit, J. (2013). Experiences of HIV stigma: The role of visible symptoms, HIV centrality and community attachment for people living with HIV. AIDS Care, 25, 1166–1173. doi:10.1080/09540121.2012.752784

- Buseh, A., Kelber, S., Stevens, P., & Park, C. (2007). Relationship of symptoms, perceived health, and stigma with quality of life among urban HIV-infected African American men. Public Health Nursing, 25, 409–419. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00725.x

- Carrico, A. (2019). Getting to zero: Targeting psychiatric comorbidities as drivers of the hiv/aids epidemic. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26, 1–2. doi:10.1007/s12529-019-09771

- Centres for Disease Control (CDC). (1981). Pneumocystis Pneumonia. Los Angeles. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 30, 250–252. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5021a1.htm

- Chan, R., Mak, W., Ma, G., & Cheung, M. (2020). Interpersonal and intrapersonal manifestations of HIV stigma and their impacts on psychological distress and life satisfaction among people living with HIV: Toward a dual-process model. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-020-02618-y

- Chapman Lambert, C., Westfall, A., Modi, R., Amico, R., Golin, C., Keruly, J., & Mugavero, M. J. (2020). HIV-related stigma, depression, and social support are associated with health-related quality of life among patients newly entering HIV care. AIDS Care, 32, 681–688. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1622635

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Cooper, V., Clatworthy, J., Harding, R., Whetham, J., & Consortium, E. (2017). Measuring quality of life among people living with HIV: A systematic review of reviews. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15, 220. doi:10.1186/s12955-017-0778-6

- Cordova, M., Riba, M., & Spiegel, D. (2017). Posttraumatic stress disorder and cancer. Lancet Psychiatry, 4, 330–338. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30014-7

- Cramer, R., Burks, A., Plöderl, M., & Durgampudi, P. (2017). Minority stress model components and affective well-being in a sample of sexual orientation minority adults living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care, 29, 1517–1523. doi:10.1080/09540121.2017.1327650

- Crawford, A. (1996). Stigma associated with AIDS: A meta‐analysis1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 26, 398–416. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1996.tb01856.x

- den Daas, C., van den Berk, G., Kleene, M., de Munnik, E., Lijmer, J., & Brinkman, K. (2019). Health-related quality of life among adult HIV positive patients: Assessing comprehensive themes and interrelated associations. Quality of Life Research, 28, 2685–2694. doi:10.1007/s11136-019-02203-y

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Đorić, S. N. (2020). HIV-related stigma and subjective well-being: The mediating role of the belief in a just world. Journal of Health Psychology, 25, 598–605. doi:10.1177/1359105317726150

- Earnshaw, V. A., Rosenthal, L., & Lang, S. M. (2016). Stigma, activism, and well-being among people living with HIV. AIDS Care, 28, 717–721. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1124978

- Earnshaw, V., & Chaudoir, S. (2009). From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: A review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 1160–1177. doi:10.1007/2Fs10461-009-9593-3

- Earnshaw, V., Smith, L., Chaudoir, S., Amico, R., & Copenhaver, M. (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS and Behavior, 17, 1785–1795. doi:10.1007/2Fs10461-013-0437-9

- Ekstrand, M., Heylen, E., Mazur, A., Steward, W., Carpenter, C., Yadav, K., … Nyamathi, A. (2018). The role of HIV stigma in ART adherence and quality of life among rural women living with HIV in India. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 3859–3868. doi:10.1007/s10461-018-2157-7

- Emlet, C. A., Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., & Kim, H. (2013). Risk and protective factors associated with health-related quality of life among older gay and bisexual men living with HIV disease. The Gerontologist, 53, 963–972. doi:10.1093/geront/gns191

- Emlet, C. (2006). ”You’re awfully old to have this disease”: Experiences of stigma and ageism in adults 50 years and older living with HIV/AIDS. Gerontologist, 46, 781–790. PMID: 17169933. doi:10.1093/geront/46.6.781

- Fazeli, P., & Turan, B. (2019). Experience sampling method versus questionnaire measurement of HIV stigma: Psychosocial predictors of response discrepancies and associations with HIV outcomes. Stigma and Health, 4, 487–494. Advance online publication. doi:10.1037/sah0000170

- Fekete, E., Williams, S., Skinta, M., & Bogusch, L. (2016). Gender differences in disclosure concerns and HIV-related quality of life. AIDS Care, 28, 450–454. doi:10.1080/09540121.2015.1114995

- Feng, S., Shu-Xun, H., and Jiaguang, T. (2014). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. PLoS One. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0111695

- Fuster-Ruizdeapodaca, M. J., Molero, F., Holgado, F., & Mayordomo, S. (2014). Enacted and internalized stigma and quality of life among people with HIV: The role of group identity. Quality of Life Research, 23, 1967–1975. doi:10.1007/s11136-014-0653-4

- Garrido-Hernansaiz, H., Heylen, E., Bharat, S., Ramakrishna, J., & Ekstrand, M. L. (2016). Stigmas, symptom severity and perceived social support predict quality of life for PLHIV in urban Indian context. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14. doi:10.1186/s12955-016-0556-x

- Greeff, M., Uys, L., Wantland, D., Makoae, L., Chirwa, M., Dlamini, P., & Holzemer, W. L. (2010). Perceived HIV stigma and life satisfaction among persons living with HIV infection in five African countries: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47, 475–486. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.09.008

- Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2016). Structural stigma: Research evidence and implications for psychological science. The American Psychologist, 71(8), 742–751. doi:10.1037/amp0000068

- Heckman, T., Anderson, E., Sikkema, K., Kochman, A., Kalichman, S., & Anderson, T. (2004). Emotional distress in nonmetropolitan persons living with HIV disease enrolled in a telephone-delivered, coping improvement group intervention. Health Psychology, 23, 94–100. PMID: 14756608. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.23.1.94

- Heckman, T., Heckman, B., Kochman, A., Sikkema, K., Suhr, J., & Goodkin, K. (2002). Psychological symptoms among persons 50 years of age and older living with HIV disease. Aging and Mental Health, 6, 121–128. doi:10.1080/13607860220126709a

- Heckman, T., Somlai, A., Kelly, J., Stevenson, L., & Galdabini, C. (1996). Rural persons living with HIV/AIDS: Barriers to care and improving quality of life. AIDS Patient Care, 10, 37–43. doi:10.1089/apc.1996.10.37

- Heckman, T., Somlai, A., Sikkema, K., Kelly, J., & Franzoi, S. (1997). Psychosocial predictors of life satisfaction among persons living with HIV infection and AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 8, 21–30. doi:10.1016/S1055-3290(97)80026-X

- Higgins, J. P., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 327, 557–560. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

- Holmes, W., & Shea, J. (1998). A new HIV/AIDS-targeted quality of life (HAT-QoL) instrument: Development, reliability, and validity. Medical Care, 36, 138–154. doi:10.1097/00005650-199802000-00004

- Holzemer, W. L., Human, S., Arudo, J., Rosa, M. E., Hamilton, M. J., Corless, I., … Maryland, M. (2009). Exploring HIV stigma and quality of life for persons living with HIV infection. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 20, 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002

- Hutton, V., Misajon, R., & Collins, F. (2013). Subjective wellbeing and “felt” stigma when living with HIV. Quality of Life Research, 22, 65–73. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0125-7

- IntHout, J., Ioannidis, J. P., Rovers, M. M., & Goeman, J. J. (2016). Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 6(7), e010247. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010247

- Jang, N., & Bakken, S. (2017). Relationships between demographic, clinical, and health care provider social support factors and internalized stigma in people living with HIV. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 28, 34–44. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2016.08.009

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Report. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-UNAIDS-data

- Kagee, A. (2008). Application of the DSM-IV criteria to the experience of living with AIDS: Some concerns. Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 1008–1011. doi:10.1177/1359105308097964

- Kalan, M. E., Han, J., Taleb, Z. B., Fennie, K. P., Jafarabadi, M. A., Dastoorpoor, M., … Rimaz, S. (2019). Quality of life and stigma among people living with HIV/AIDS in Iran. HIV/AIDS - Research and Palliative Care, 11, 287–298. doi:10.2147/HIV.S221512

- Kang, E., Rapkin, B., Remien, R., Mellins, C., & Oh, A. (2005). Multiple dimensions of HIV stigma and psychological distress among Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV illness. AIDS and Behavior, 9, 145–154. doi:10.1007/s10461-005-3896-9

- Kangas, M., Henry, J., & Bryant, R. (2005). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer. Health Psychology, 24, 579–585. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.579

- Lacombe-Duncan, A., & Chuang, D. (2018). A social ecological approach to understanding life satisfaction among socio-economically disadvantaged people living with HIV/AIDS in Taiwan: Implications for social work practice. British Journal of Social Work, 48, 557–577. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcx060

- Laschober, T. C., Serovich, J. M., Brown, M. J., Kimberly, J. A., & Lescano, C. M. (2019). Mediator and moderator effects on the relationship between HIV-positive status disclosure concerns and health-related quality of life. AIDS Care, 31, 994–1000. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1595511

- Levi-Minzi, M., & Surratt, H. (2014). HIV stigma among substance abusing people living with HIV/AIDS: Implications for HIV treatment. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 28, 442. doi:10.1089/apc.2014.0076

- Li, X., Huang, L., Wang, H., Fennie, K. P., He, G., & Williams, A. B. (2011). Stigma mediates the relationship between self-efficacy, medication adherence, and quality of life among people living with HIV/AIDS in China. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 25(11), 665–671. doi:10.1089/apc.2011.0174

- Li, X., Li, L., Wang, H., Fennie, K. P., Chen, J., & Williams, A. B. (2015). Mediation analysis of health-related quality of life among people living with HIV infection in China. Nursing and Health Sciences, 17, 250–256. doi:10.1111/nhs.12181

- Liamputtong, P. (2013). Stigma, discrimination and living with HIV/AIDS A cross-cultural perspective. Melbourne: Springer.

- Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Logie, C. H., Ahmed, U., Tharao, W., & Loutfy, M. R. (2017). A structural equation model of factors contributing to quality of life among African and Caribbean women living with HIV in Ontario, Canada. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 33, 290–297. doi:10.1089/aid.2016.0013

- Logie, C. H., Wang, Y., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Wagner, A. C., Kaida, A., Conway, T., & Loutfy, M. R. (2018). HIV-related stigma, racial discrimination, and gender discrimination: Pathways to physical and mental health-related quality of life among a national cohort of women living with HIV. Preventive Medicine, 107, 36–44. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.12.018

- Logie, C., & Gadalla, T. (2009). Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care, 21, 742–753. doi:10.1080/09540120802511877

- Machtinger, E., Wilson, T., Haberer, J., & Weiss, D. (2012). Psychological trauma and PTSD in HIV-positive women: A meta-analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 16, 2091–2100. doi:10.1007/s10461-011-0127-4

- Mak, W., Cheung, R., Law, R. W., Woo, J., Li, P., & Chung, R. (2007). Examining attribution model of self-stigma on social support and psychological well-being among people with HIV+/AIDS. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 1549–1559. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.12.003

- Meyer, I. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 5, 674–697. doi:10.1037/2F0033-2909.129.5.674

- Miller, C. T., Solomon, S. E., Varni, S. E., Hodge, J. J., Knapp, F. A., & Bunn, J. Y. (2016). A transactional approach to relationships over time between perceived HIV stigma and the psychological and physical well-being of people with HIV. Social Science and Medicine, 162, 97–105. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.025

- Misir, P. (2015). Structuration Theory: A Conceptual Framework for HIV/AIDS Stigma. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC), 14, 328–334. doi:10.1177/2F2325957412463072

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.; The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6, e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

- Murphy, D. A., Austin, E. L., & Greenwell, L. (2006). Correlates of HIV-related stigma among HIV-positive mothers and their uninfected adolescent children. Women and Health, 44, 19–42. doi:10.1300/J013v44n03_02

- Neigh, G., Rhodes, S., Valdez, A., & Jovanovic T. (2016). PTSD co-morbid with HIV: Separate but equal, or two parts of a whole? Neurobiology of Disease, 92, 116–123. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.012

- Nguyen, A., Sundermann, E., Rubtsova, A., Sabbag, S., Umlauf, A., Heaton, R., Letendre, S., Jeste, D., & Marquine, M. 2020. Emotional health outcomes are influenced by sexual minority identity and HIV serostatus. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV. doi:10.1080/09540121.2020.1785998

- Nobre, N., Pereira, M., Roine, R. P., Sutinen, J., & Sintonen, H. (2018). HIV-related self-stigma and health-related quality of life of people living with HIV in Finland. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 29, 254–265. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2017.08.006

- Olkin, I., Dahabreh, I. J., & Trikalinos, T. A. (2012). GOSH - a graphical display of study heterogeneity. Research Synthesis Methods, 3(3), 214–223. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1053

- Parcesepe, A. M., Nash, D., Tymejczyk, O., Reidy, W., Kulkarni, S., & Elul, B. (2020). Gender, HIV-related stigma, and health-related quality of life among adults enrolling in HIV care in Tanzania. AIDS and Behavior, 24, 142–150. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02480-1

- Parker, R., & Aggleton, R. (2003). HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine, 57, 13–24. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0

- Peters, J. L., Sutton, A. J., Jones, D. R., Abrams, K. R., & Rushton, L. (2008). Contour-enhanced meta-analysis funnel plots help distinguish publication bias from other causes of asymmetry. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61, 991–996. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.010

- Porter, K. E., Brennan-Ing, M., Burr, J. A., Dugan, E., Karpiak, S., & Pruchno, R. (2017). Stigma and psychological well-being among older adults with HIV: The impact of spirituality and integrative health approaches. Gerontologist, 57, 219–228. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv128

- Porter, K. E., Brennan-Ing, M., Burr, J. A., Dugan, E., & Karpiak, S. (2019). HIV stigma and older men’s psychological well-being: Do coping resources differ for gay/bisexual and straight men? Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74, 685–693. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx101

- Ramirez-Valles, J., Fergus, S., Reisen, C. A., Poppen, P. J., & Zea, M. C. (2005). Confronting stigma: Community involvement and psychological well-being among HIV-positive latino gay men. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 27, 101–119. doi:10.1177/0739986304270232

- Rao, D., Chen, W. T., Pearson, C. R., Simoni, J. M., Fredriksen-Goldsen, K., Nelson, K., … Zhang, F. (2012). Social support mediates the relationship between HIV stigma and depression/quality of life among people living with HIV in Beijing, China. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 23, 481–484. doi:10.1258/ijsa.2009.009428

- Rasoolinajad, M., Abedinia, N., Noorbala, A. A., Mohraz, M., Badie, B. M., Hamad, A., & Sahebi, L. (2018). Relationship among HIV-related stigma, mental health and quality of life for HIV-positive patients in Tehran. AIDS and Behavior, 22, 3773–3782. doi:10.1007/s10461-017-2023-z

- Relf, M., Pan, W., Edmonds, A., Ramirez, C., Amarasekara, S., & Adimora, A. (2019). Discrimination, medical distrust, stigma, depressive symptoms, antiretroviral medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life among women living with HIV in North Carolina: A mediated structural equation model. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, 81, 328–335. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000002033

- Rendina, H. J., Weaver, L., Millar, B. M., López-Matos, J., & Parsons, J. T. (2019). Psychosocial well-being and HIV-related immune health outcomes among HIV-positive older adults: Support for a biopsychosocial model of HIV stigma and health. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, 18. doi:10.1177/2325958219888462

- Rendina, H., Brett, M., & Parsons, J. (2018). The critical role of internalized HIV-related stigma in the daily negative affective experiences of HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 289–297. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.11.005

- Rueda, S., Mitra, S., Chen, S., Gogolishvili, D., Globerman, J., Chambers, L., & Rourke, S. B. (2016). Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 6, e011453. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011453

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

- Rzeszutek, M., Gruszczyńska, E., & Firląg-Burkacka, E. (2018). Socio-medical and personality correlates of psychological well-being among people living with HIV: A latent profile analysis. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 14, 1113–1127. doi:10.1007/s11482-018-9640-

- Sanjuán, P., Molero, F., Fuster, M. J., & Nouvilas, E. (2013). Coping with HIV related stigma and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 709–722. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9350-6

- Sayles, J., Hays, R., Sarkisian, C., Mahajan, A., Spritzer, K., & Cunningham, W. (2008). Development and psychometric assessment of a multidimensional measure of internalized HIV stigma in a sample of HIV-positive adults. AIDS and Behavior, 12, 748–758. doi:10.1007/s10461-008-9375-3

- Schwarzer, G. (2007). meta: An R package for meta-analysis. R News, 7, 40–45. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/meta/meta.pdf

- Sherr, L., Nagra, N., Kulubya, G., Catalan, J., Clucasa, C., & Harding, R. (2011). HIV infection associated post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth – A systematic review. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 16, 612–629. doi:10.1080/13548506.2011.579991

- Shrestha, S., Shibanuma, A., Poudel, K. C., Nanishi, K., Koyama Abe, M., Shakya, S., & Jimba, M. (2019). Perceived social support, coping, and stigma on the quality of life of people living with HIV in Nepal: A moderated mediation analysis. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 31, 413–420. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1497136

- Slater, L. Z., Moneyham, L., Vance, D. E., Raper, J. L., Mugavero, M. J., & Childs, G. (2013). Support, stigma, health, coping, and quality of life in older gay men with HIV. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 24, 38. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2012.02.006

- Smith, R., Rossetto, K., & Peterson, B. (2008). A meta-analysis of disclosure of one’s HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care, 20, 1266–1275. doi:10.1080/09540120801926977

- Song, B., Yan, C., Lin, Y., Wang, F., & Wang, L. (2016). Health-related quality of life in HIV-infected men who have sex with men in China: A cross-sectional study. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 22, 2859–2870. doi:10.12659/msm.897017

- Sowell, R., Lowenstein, A., Moneyham, L., Demi, A., Mizuno, Y., & Seals, B. (1997). Resources, stigma and patterns of disclosure in rural women with HIV infection. Public Health Nursing, 14, 302–312. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.1997.tb00379.x

- Stewart, A., Hays, R., & Ware, J. (1988). The MOS short-form general health survey: Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care, 26, 724–735. doi:10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007

- Storholm, E. D., Halkitis, P. N., Kupprat, S. A., Hampton, M. C., Palamar, J. J., Brennan-Ing, M., & Karpiak, S. (2013). HIV-related stigma as a mediator of the relation between multiple-minority status and mental health burden in an aging HIV-positive population. Journal of HIV/AIDS and Social Services, 12, 9–25. doi:10.1080/15381501.2013.767557

- Swendeman, D., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Comulada, S., Weiss, R., & Ramos, M. E. (2006). Predictors of HIV-related stigma among young people living with HIV. Health Psychology, 25, 501–509. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.501

- Tang, C., Goldsamt, L., Meng, J., Xiao, X., Zhang, L., Williams, A., & Wang, H. (2020). Global estimate of the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among adults living with HIV: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 10(4), e032435. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032435

- Tran, B. X., Fleming, M., Do, H. P., Nguyen, L. H., & Latkin, C. A. (2018). Quality of life improvement, social stigma and antiretroviral treatment adherence: Implications for long-term HIV/AIDS care. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 30, 1524–1531. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1510094

- Varni, S. E., Miller, C. T., McCuin, T., & Solomon, S. (2012). Disengagement and engagement coping with HIV/AIDS stigma and psychological well-being of people with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31, 123–150. doi:10.1521/jscp.2012.31.2.123

- Veld, D., Pengpid, S., Colebunders, R., Skaal, L., & Peltzer, K. (2017). High-risk alcohol use and associated socio-demographic, health and psychosocial factors in patients with HIV infection in three primary health care clinics in South Africa. International Journal of STD and AIDS, 28, 651–659. doi:10.1177/0956462416660016

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the Metafor Package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1–48. doi:10.18637/jss.v036.i03

- Vincent, W., Fang, X., Calabrese, S. K., Heckman, T. G., Sikkema, K. J., & Hansen, N. B. (2017). HIV-related shame and health-related quality of life among older, HIV-positive adults. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 434–444. doi:10.1007/s10865-016-9812-0

- Wagner, A. C., Hart, T. A., Mohammed, S., Ivanova, E., Wong, J., & Loutfy, M. R. (2010). Correlates of HIV stigma in HIV-positive women. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 13, 207–214. doi:10.1007/s00737-010-0158-2

- Watson, D., Clark, L., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect. The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

- WHOQOL Group. (1995). WHOQOL Group, The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment: Position paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science and Medicine, 41, 1403–1409. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-k

- Wu, X., Chen, J., Huang, H., Liu, Z., Li, X., & Wang, H. (2015). Perceived stigma, medical social support and quality of life among people living with HIV/AIDS in Hunan, China. Applied Nursing Research, 28, 169–174. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2014.09.011

- Yang, X., Li, X., Qiao, S., Li, L., Parker, C., Shen, Z., & Zhou, Y. (2020). Intersectional stigma and psychosocial well-being among MSM living with HIV in Guangxi, China. AIDS Care - Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 32(sup2), 5–13. doi:10.1080/09540121.2020.1739205

- Zhou, G., Li, X., Qiao, S., Shen, Z., & Zhou, Y. (2020). HIV symptom management self-efficacy mediates the relationship of internalized stigma and quality of life among people living with HIV in China. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(3), 311–321. doi:10.1177/1359105317715077

- Zhu, M., Guo, Y., Li, Y., Zeng, C., Qiao, J., Xu, Z., … Liu, C. (2020). HIV-related stigma and quality of life in people living with HIV and depressive symptoms: Indirect effects of positive coping and perceived stress. AIDS Care, 32(8), 1030–1035. doi:10.1080/09540121.2020.1752890

- Zulkarnain, Z., Tuapattinaja, J., Yurliani, R., & Iskandar, R. (2020). Psychological well-being of housewives living with HIV/AIDS: Stigma and forgiveness. HIV and AIDS Review, 9(1), 24–29. doi:10.5114/hivar.2020.93158