ABSTRACT

CMV can infect a variety of organs including gastrointestinal tract, meninges, eyes and other organs depending upon the nature of immune system but it can also manifest as a flare-up in ulcerative colitis patients. It usually presents as loose stools, bright red blood in the stool and weight loss in the patient. In the setting of an Immunocompetent patient, CMV colitis has been diagnosed in patients with occult inflammatory bowel disease. It is usually diagnosed on histology secondary to endoscopic biopsy. We herein report a case of a 73 years old female with CMV colitis found to have underlying ulcerative colitis.

1. Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is common in normal adults and is generally asymptomatic but it gets symptomatic in patients with defective cell-mediated immunity like AIDS, transplant patients and those receiving chemotherapy for myelo-or lymphoproliferative disorders, particularly when treated with steroids [Citation1]. CMV colitis usually presents with loose stools and abdominal discomfort. Here is a case of a 73 years old female who presented with complaints of loose stools and bleeding per rectum, significant weight loss and eventually diagnosed with CMV colitis with the help of biopsy and polymerase chain reaction test

2. Case presentation

A 73 years old female with significant past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and Type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital with complaints of diarrhea, hematochezia, lower left quadrant abdominal pain and significant weight loss of 25lbs in 6 weeks. The patient denied vomiting, any recent change in her diet, sick contacts, recent travel or any other active complaints. Physical exam was significant for dry oral mucosa, diffuse abdominal tenderness more prominent in left lower quadrant and sluggish bowel sounds. Her laboratory findings were significant for Hemoglobin: 10mg/dl, hematocrit: 34, white blood cell count: 15 x 103, sodium: 131, bicarbonate 20.2 with normal anion gap, albumin of 2.1 and globulin of 3.9. Clostridium Difficle PCR and Giardia Lamblia antigen were negative on the stool smear. Computerized tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed wall thickening of the distal descending colon and sigmoid colon concerning for colitis (), Hence, a colonoscopy was performed for further evaluation.

Figure 1. CT scan.

Bowel wall thickening at the level of distal descending and sigmoid colon indicated by a red arrow – CT scan.

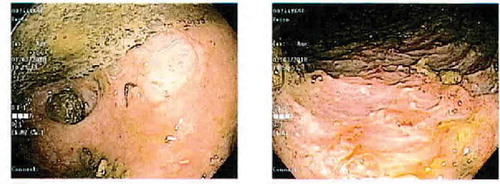

Colonoscopy showed ulcerated mucosa, and punched out ulcers throughout the colon. Pathology results revealed inclusion bodies as shown in the bottom picture of concerning for CMV. Hence, the patient was started on ganciclovir and after improvement, was discharged to a subacute rehabilitation center.

Figure 2. Colonoscopic biopsy.

On above Left Image: Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing Cryptitis. On above right side: Hematoxylin and Eosin staining showing shortening of the crypts and Crypts Abscess – marked by Black Arrow. On below image: classic ‘owl eye inclusion bodies’ visualized on histology

The patient was readmitted a few weeks later with altered mental status and significant abdominal pain. Physical exam demonstrated guarding, rigidity and absent bowel sounds concerning for bowel perforation. CT scan of abdomen and pelvis was done which showed extensive air in mesentery and abdominal cavity consistent with perforation with the most likely site being the distal colon. The patient underwent subtotal colectomy and tissue was sent for biopsy. The differential considerations at that point included inflammatory bowel disease and ischemic colitis.

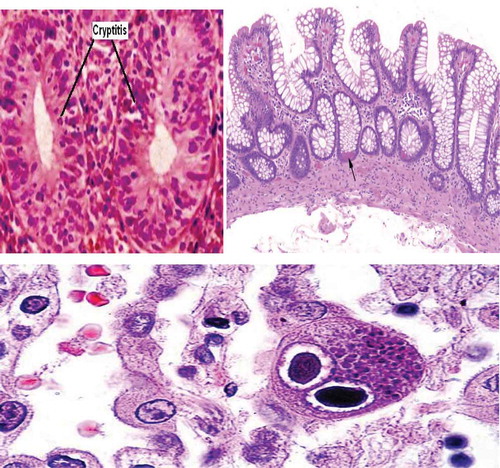

Histology of the terminal ileum and colon revealed chronic active colitis including crypt distortion and crypt abscess as shown in the left and right pictures () involving the entire colon with extensive ulceration and pseudo polyp formation with terminal ileum sparing consistent with active ulcerative pancolitis.

3. Discussion

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is common in normal adults and is generally asymptomatic. It gets symptomatic in patients with defective cell-mediated immunity like AIDS, transplant patients and those receiving chemotherapy. The disease can be due to either reactivation of latent infection, re-infection or new infection. Significant CMV disease may be manifested in a variety of organs like the retina, the gastrointestinal tract, and the lung. The target organ seems to be specific to the nature of the immunodeficiency [Citation1].

In the gastrointestinal tract, CMV infection may affect from mouth to anus with nonspecific gross lesions of erosions, ulcerations and mucosal hemorrhage. Microscopically, sub-mucosal vasculitis or microvascular thrombosis is often present as seen in our case. Tissue necrosis may also be a prominent feature. On histology, the diagnosis is usually made by visualizing the large cells with intra-nuclear and intra-cytoplasmic inclusions (Owl eye Inclusion bodies) as seen in our case. Culture is neither sensitive nor specific.

There are several cases in the worldwide literature of patients with established inflammatory bowel disease developing an acute exacerbation secondary to cytomegalovirus disease [Citation2–Citation5]. The vast majority of cases of CMV infection have been in patients with ulcerative colitis; only one case had Crohn ileocolitis [Citation6] and one had indeterminate colitis [Citation3]. Begos, et al concluded from their investigations that patients with inflammatory bowel disease complicated by cytomegalovirus colitis had a 67% colectomy rate and 33% mortality rate [Citation7]. Another study conducted by Orvar, et al, suggested that onset of CMV infection might act as a triggering factor for the presentation of ulcerative colitis. [Citation8] We treated the CMV infection in the patient. In the study conducted by Van Dorp, et al, it showed that CMV infection in tissue culture causes the induction of MHC I surface antigen expression in monocytes. Thus, CMV infection in colonocytes may trigger an autoimmune response in the susceptible host which leads to the manifestation of ulcerative colitis [Citation9]. Previous reports relied heavily on biopsy evidence before the start of ganciclovir therapy. Histology demonstrating the classical appearance of ‘owl’s eye’ inclusion bodies is the gold standard test for cytomegalovirus diagnosis. Xiaoyan et.al in his study demonstrated that biopsies which had > 2 Immunohistochemical stains positive for CMV and positive PCR in the serum were truly infective and recommended treatment with ganciclovir. Biopsies which had 1–2 IHC stains positive for CMV were probably ‘innocent bystanders’ and did not recommend treatment unless they were immunocompromised or post-transplant patient where treatment was recommended irrespective of the number of cells with positive stains and CMV viremia [Citation10].

Getting back to our case, it was very unclear which process occurred first. Was it the CMV infection that preceded ulcerative colitis or vice versa. There was no mention of ulcerative colitis in the early pathology which is why the patient was only treated with ganciclovir. The subsequent pathology report commented on the ulcerative colitis but due to concern for worsening of CMV colitis, steroids therapy was not initiated.

4. Conclusion

Cytomegalovirus infections are asymptomatic in a patient with the intact immune system, although it is reported as a notorious infection in the setting of acquired or inherited defective T cell-mediated immunity. It virtually affects any organ but has a predilection for retina, brain and gastrointestinal system. There have been multiple case reports of patients who developed CMV infections manifesting as colitis in the setting of intact immunity. Such patients were simultaneously diagnosed with ulcerative colitis as in our patient. Based on the limited data we have, it appears that there may be an association of CMV colitis with ulcerative colitis and it is reasonable to consider ulcerative colitis in an immunocompetent patient presenting with CMV colitis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Goodgame RW Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus disease. Ann Int Med. 119:924–935, 1993.

- Vega R, Bertran X, Menacho M, et al. Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1053–1056.

- Papadakis KA, Tung JK, Binder SW, et al. Outcome of cytomegalovirus infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2137–2142.

- Eddleston M, Peacock MS, Juniper, et al. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:52–56.

- Kaufman HS, Kahn AC, Iacobuzio-Donahue C, et al. Cytomegalovirus enterocolitis: clinical associations and outcome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:24–30.

- Dent DM, Duys PJ, Bird AR, et al. Cytomegalic virus infection of bowel in adults. S.Afr.Med.J. 49:669–672, 1975.

- Begos DG, Rappaport R, Jain D. Cytomegalovirus infection masquerading as an ulcerative colitis flare-up: case report and review of the literature. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:323–328.

- Orvar K, Murray J, Carmen G, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection associated with onset of inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:2307–2310.

- Van Dorp WT, Jonges E, Bruggeman CA, et al. Direct induction of MHC class I but not class II expression of endothelial cells by cytomegalovirus infection. Transplantation. 1989;48:469–472.

- Liao X, Reed SL, Lin GY. Immunostaining detection of cytomegalovirus in gastrointestinal biopsies: clinicopathological correlation at a large academic health system. Gastroenterology Res. 2016;9(6):92–98.