ABSTRACT

Pasteurella multocida is a gram-negative bacterium that colonizes domestic animals. It is commonly implicated in bite and scratch wounds, potentially resulting in cellulitis, superficial abscesses, osteomyelitis, or peritonitis. Rarely, it can lead to bacteremia and septic shock in high-risk patients. We present an atypical presentation of Pasteurella multocida bacteremia and sepsis in a patient with stage 4 decompensated cirrhosis. The patient presented with melena and altered mental status with CT imaging showing a heterogeneous nodular liver along with an enlarged portal vein, gastric varices, and ascites consistent with decompensated cirrhosis. The patient was initially managed with intravenous (IV) octreotide and pantoprazole, blood and platelet transfusions, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Upper endoscopy showed diffuse non-bleeding esophageal and gastric varices, which required band ligation and continued IV octreotide therapy. The infection resolved after a 7-day course of IV ceftriaxone.

1. Introduction

Pasteurella multocida is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic coccobacilli commonly found in the normal flora of domestic animals, such as cats, dogs, and pigs [Citation1]. Cats and dogs have a particularly high carriage rate, 70–90% and 2–50%, respectively, [Citation2]. With high rates of pet ownership throughout the world, and in the USA in particular, there is an increasing threat of zoonoses among human populations [Citation3]. Each year, there are approximately 300,000 visits to the emergency departments in the U.S. secondary to animal bite or scratch wounds each year, of which Pasteurella species are isolated from 50% of dog bites and 75% of cat bites [Citation4–6]. Pasteurella species are usually associated with soft tissue infections, particularly cellulitis and abscess formation [Citation7]. Less commonly, pneumonia, osteomyelitis, peritonitis, meningitis, and blood stream infections have also been associated with Pasteurella [Citation1,Citation7–12]. Pasteurella’s ability to act as an opportunist pathogen and cause bacteremia in immunocompromised and liver failure/dysfunction patients has been rarely documented [Citation1,Citation13,Citation14]. Here we present a case of Pasteurella multocida bacteremia and septic shock in a patient with cirrhosis.

2. Case report

A 65-year-old man was brought to the emergency department with a 1-day history of melena and altered mental status. Though the patient was unable to provide a cogent history due to his altered sensorium, the patient’s significant other noted that the patient displayed confusion, incoherent speech, and progressive somnolence over the prior day. In addition, the patient had profuse diarrhea with dark tarry stools over the last few hours prior to presentation, resulting in noticeably soiled clothing. The patient had not complained to his significant other regarding fevers, chills, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting. His medical history included untreated chronic hepatitis C and polysubstance abuse. There had been no recent travel, but the patient had a history of chronic alcoholism and numerous episodes of binge drinking over the last 2–3 months.

His vital signs on admission were as follows: blood pressure, 125/100 mmHg; pulse, 135 beats per minute; temperature, 99.2ºF; O2 saturation, 91% on room air; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths per minute. On physical examination, mucous membranes were dry and there was a partially healed wound with surrounding erythema on the right knee with no crepitus or fluctuance (see ). There was no jaundice or significant findings on the abdominal examination; Murphy’s sign was negative. The patient appeared lethargic and somnolent, with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 8 leading to concerns about patient’s ability to protect his own airway. As a result, patient was intubated in the emergency room.

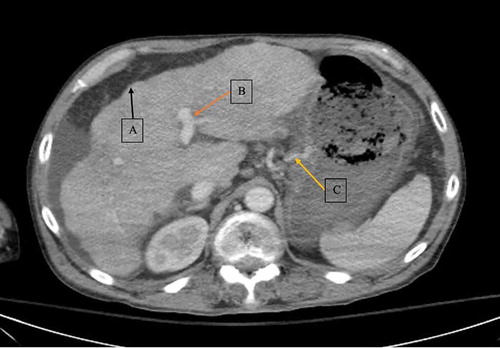

Initial laboratory tests were done in the emergency department (see ). Laboratory work revealed an increase in creatinine to 1.5 mg/dL from baseline of 0.8 mg/dL and a drop in hemoglobin to 6.7 g/dL from baseline of 11 g/dL. Abdominal CT scan with intravenous (IV) contrast was consistent with hepatic cirrhosis along with a heterogeneous and nodular liver, portal hypertension with an enlarged portal vein, and gastric varices (see ). A CT scan of the right lower extremity was also performed, which showed cellulitis without abscess or gas formation. The patient received IV infusion of octreotide, packed red blood cells and platelets, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. Given the patient’s tachycardia and leukocytosis, he met two of four criteria for the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). In addition to SIRS, given elevated lactate, hepatic encephalopathy, respiratory failure and concern for bleeding varices in setting of decompensated cirrhosis, patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Table 1. Laboratory values

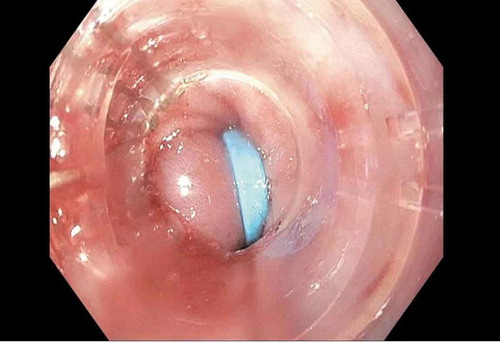

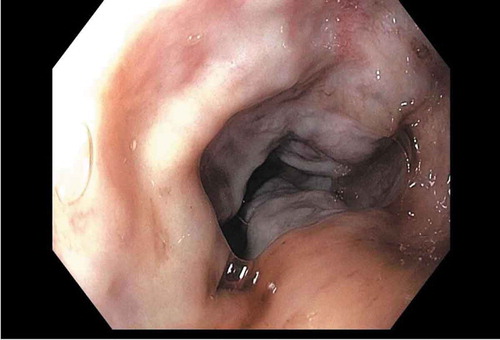

In the ICU, the patient underwent emergent upper endoscopy, which showed diffuse non-bleeding esophageal and gastric varices (see ). Band ligation was performed on multiple varices. The patient received octreotide infusion through the first 2 days of hospitalization, without experiencing further episodes of melena. Patient was successfully extubated on day 3 of admission, with return to baseline mentation.

Patient was then able to provide further history and endorsed being bitten by a dog below his right knee 3 weeks prior to presentation, with subsequent subjective fevers and chills. At this point, blood culture collected on admission returned positive for gram-negative rods, later identified as Pasteurella multocida. The patient was then treated with a 7-day course of IV ceftriaxone prior to discharge, with the presumption that the Pasteurella bacteremia resulted from the recent dog bite. Patient was discharged home at baseline on day 15.

3. Discussion

Pasteurella multocida has multiple virulence factors that aid in pathogenesis including but not limited to membrane lipopolysaccharides (LPS), presence of a surrounding capsule, elaboration of adhesins and proteases, and iron acquisition mechanisms [Citation15–17]. LPS is a particularly important virulence factor, serving as a barrier to serum complement-induced degradation, while the outer capsule confers resistance to phagocytosis [Citation6,Citation15,Citation18].

Multiple studies conclude that P. multocida–related infections are primarily acquired through contact with animals and in particular household pets [Citation4–7]. A review conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Greece of 13 cases of Pasteurella-induced infections found that the majority of cases were soft tissue and respiratory infections in nature, such as pneumonia and tracheobronchitis [Citation19]. Another analysis of 34 case reports concluded that the most common infectious process was soft tissue infection, followed by respiratory and abdominal infections [Citation1]. Giordano et al. reported 44 patients at a single center with Pasteurella multocida infection, in which 25 were infected via animal bites and no bites were reported in the remainder of the patients [Citation20]. In that series, skin and soft tissue infections were once again predominant, followed by bloodstream and respiratory infections [Citation20]. Other case reports detail rare sequelae of P. multocida infection, including endocarditis, meningitis, and septic shock [Citation1,Citation7–12,Citation21,Citation22].

As various case reports document Pasteurella infection [Citation1,Citation7,Citation13–15,Citation23–25] in patients with immune-compromised states and with cirrhosis, these conditions are considered risk factors for infection. Giordano et al. identified an immunocompromised state as a risk factor for Pasteurella multocida infection in 63% of patients in their case series [Citation20]. A study in the American Journal of Infectious Diseases, cited that in patients with bacteremia, there was a mortality rate of 31%, with all fatalities occurring in patients with severe cirrhosis [Citation19]. The study included 13 patients, of which one patient died within 24 h of admission while two patients died after prolonged ICU treatment [Citation19]. Furthermore, the presence of an immunocompromised state, in the form of cirrhosis, suggests the need for ICU level of care [Citation20]. Wilson et al. also documented the presence of immunocompromised state, including liver dysfunction and less commonly chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and renal dysfunction, as factors increasing susceptibility to Pasteurella infection [Citation15,Citation20].

Why does cirrhosis invite infection with this organism? When the LPS on its outer cell membrane encounters hepatocytes, there is widespread release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), a pro-apoptotic cytokine [Citation15,Citation26]. Animal studies have demonstrated that in hepatic cirrhosis, nuclear factor kappa Beta (NF-kB), which normally protects cells from TNF-alpha apoptosis, is downregulated. This subsequently leads to potentiation of the action of TNF-alpha, resulting in hepatocyte cell death [Citation15,Citation26]. Given this pathophysiology, patients with chronic hepatic cirrhosis are particularly susceptible to complications from gram-negative bacteremia.

Empiric treatment of animal bites is typically a penicillin antibiotic in combination with a beta- lactamase inhibitor, such as amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. An alternative is clindamycin plus a fluoroquinolone, although the combination of a third-generation cephalosporin and a fluoroquinolone would also be effective. Fortunately, resistance has been minimal in Pasteurella species [Citation15,Citation20].

4. Conclusion

The prevalence of cirrhosis is increasing in the U.S., reflecting the growing epidemic of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [Citation27]. Even more common is the presence of domestic pets, who serve as carriers for multiple pathogens including Pasteurella multocida. Our case highlights the need for education and vigilance regarding the presence of pets, particularly cats and dogs, near immunocompromised and cirrhotic patients. Pasteurella multocida should be suspected in patients presenting with decompensation of cirrhosis without an obvious infectious source. Blood cultures should be collected promptly to further guide treatment. A history of close animal contact might prompt empiric antibiotic treatment, averting a potentially fulminant clinical course.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Weber DJ, Wolfson JS, Swartz MN, et al. Pasteurella multocida infections. Medicine (Baltimore). 1984;63(3):133–154.

- Owen CR, Buker EO, Bell JF, et al. Pasteurella multocida in animals’ mouths. Rocky Mt Geol. 1968;65(11):45–46.

- Cutler SJ, Fooks AR, Van Der Poel WH. Public health threat of new, reemerging, and neglected zoonoses in the industrialized world. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(1):1–7.

- Weiss HB, Friedman DI, Coben JH. Incidence of dog bite injuries treated in emergency departments. JAMA. 1998;279(1):51–53.

- Griego RD, Rosen T, Orengo IF, et al. Dog, cat, and human bites: a review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33(6):1019–1029.

- Talan DA, Citron DM, Abrahamian FM, et al. Bacteriologic analysis of infected dog and cat bites. Emergency medicine animal bite infection study group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):85–92.

- Harper M, Boyce JD, Adler B. Pasteurella multocida pathogenesis: 125 years after Pasteur. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;265(1):1–10.

- Nagata H, Yamada S, Uramaru K, et al. Acute cholecystitis with bacteremia caused by Pasteurella multocida. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2014;15(1):72–74.

- Charalampopoulos A, Apostolakis M, Tsiodra P. Pasteurella multocida pneumonia in an elderly non-immunocompromised man with a leg ulcer and exposure to cats. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(5):380.

- Samarkos M, Fanourgiakis P, Nemtzas I, et al. Pasteurella multocida bacteremia, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and septic arthritis in a cirrhotic patient. Hippokratia. 2010;14(4):303.

- Hombal SM, Dincsoy HP. Pasteurella multocida endocarditis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;98(6):565–568.

- Kawashima S, Matsukawa N, Ueki Y, et al. Pasteurella multocida meningitis caused by kissing animals: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurol. 2010;257(4):653–654.

- Migliore E, Serraino C, Brignone C, et al. Pasteurella multocida infection in a cirrhotic patient: case report, microbiological aspects and a review of literature. Adv Med Sci. 2009;54(1):109–112.

- Palutke WA, Boyd CB, Carter GR. Pasteurella multocida septicemia in a patient with cirrhosis. Report of a case. Am J Med Sci. 1973;266(4):305–308.

- Wilson BA, Ho M. Pasteurella multocida: from zoonosis to cellular microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(3):631–655.

- Wilkie IW, Harper M, Boyce JD, et al. Pasteurella multocida: diseases and pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2012;361:1–22.

- Hatfaludi T, Al-Hasani K, Boyce JD, et al. Outer membrane proteins of Pasteurella multocida. Vet Microbiol. 2010;144(1–2):1–17.

- Donnio PY, Lerestif-Gautier AL, Avril JL. Characterization of Pasteurella spp. strains isolated from human infections. J Comp Pathol. 2004;130(2–3):137–142.

- Christidou A, Maraki S, Gitti Z, et al. Review of Pasteurella multocida infections over a twelve-year period in a tertiary care hospital. Am J Infect Dis. 2005;1(2):107–110.

- Giordano A, Dincman T, Clyburn BE, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Pasteurella multocida infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(36):e1285.

- Adler AC, Cestero C, Brown RB. Septic shock from Pasturella multocida following a cat bite: case report and review of literature. Connecticut Med. 2011;75(10):603–605.

- Al-Ghonaim MA, Abba AA, Al-Nozha M. Endocarditis caused by Pasteurella multocida. Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26(2):147–149.

- Morris JT, McAllister CK. Bacteremia due to Pasteurella multocida. South Med J. 1992;85(4):442–443.

- Tamaskar I, Ravakhah K. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with Pasteurella multocida in cirrhosis: case report and review of literature. South Med J. 2004;97(11):1113–1115.

- Ashley BD, Noone M, Dwarakanath AD, et al. Fatal Pasteurella dagmatis peritonitis and septicaemia in a patient with cirrhosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(2):210–212.

- Gustot T, Durand F, Lebrec D, et al. Severe sepsis in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50(6):2022–2033.

- Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, et al. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):123–133.