ABSTRACT

Background and objectives: Ukraine’s mental health system has been found to be inadequate and unresponsive to the needs of the population, in view of its emphasis on inpatient service delivery. This study sought to identify potential changes to the organization and financing of mental health services within the Ukrainian health system that would facilitate the delivery of mental health services in a community-based setting.

Methodology: A systematic literature review was undertaken to identify organizational and financing features that have been successfully used to enable and incentivize the delivery of community-based mental health services in Central or Eastern European and/or former Soviet Union countries.

Results: There was limited literature on the organizational and financing features that facilitate the delivery of community-based care. Key facilitators for transitioning from institution-based to community-based mental health service delivery include; a clear vision for community-based care, investment in the mental health system, and mechanisms that allow health funding to follow the patient through the health system.

Conclusions: Ukraine should adopt strategic purchasing mechanisms to address inefficiency in the financing of its mental health system, and prioritize collaborative planning and delivery of mental health services. Ongoing reform of the Ukrainian health system provides momentum for instituting such changes.

Introduction

Mental health disorders are a leading contributor to morbidity and disability among the global population. Major depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, dysthymia, and bipolar disorder represent five of the top 20 causes of the global burden of disease, and account for almost a quarter of all years lived with disability globally [Citation1]. In order to better respond to the burden of mental disorders, health systems around the world have been encouraged to deinstitutionalize their mental health systems and move toward enhanced provision of services in primary and community-based settings [Citation2–5].

The Ukrainian government has acknowledged the need to reform its mental health system in order to meet the needs of its population [Citation6]. The prevalence of mental disorders in Ukraine is high, with one in three Ukrainians experiencing at least one mental health disorder in their lifetime [Citation7]. The most common mental disorders in Ukraine include alcohol disorders, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders [Citation7,Citation8]. The overall prevalence of disorders such as depression has been found to be substantially higher in Ukraine compared to Western European countries [Citation8]. For example, a 2018 report indicated depressive disorder among 6.31% of the population in Ukraine, compared to the EU average of 5.02% [Citation9]. Furthermore, conflict and displacement as a result of the ongoing war in Eastern Ukraine have resulted in higher rates of mental health disorders in the East, as well as among internally displaced persons (IDPs) across Ukraine [Citation10–12]. Research into the mental health implications of the conflict found that 8.2% of respondents struggle with symptoms of PTSD, whilst 12.7% of respondents showed indications of excessive alcohol abuse [Citation13]. Despite the high burden of mental health disorders seen in Ukraine, few Ukrainians access mental health services. For example, a recent survey indicated a treatment gap of 75% among IDPs with common mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) [Citation11].

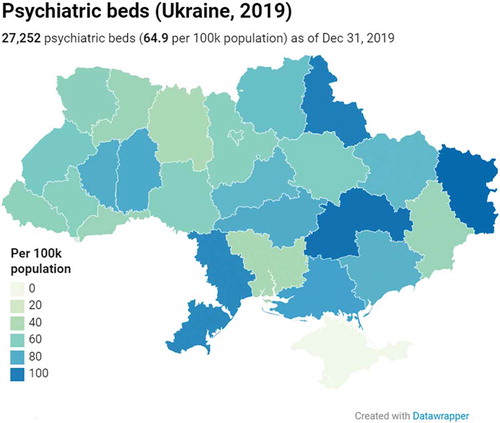

Reviews of the Ukrainian mental health system have attributed this treatment gap to its centrally planned, Semashko-style structure, that has remained largely unchanged since Ukrainian independence in 1991 [Citation9,Citation14]. The Ukrainian mental health system comprises psychiatric and narcological hospitals,Footnote1 psychiatric and narcologic departments in general hospitals, a large network of outpatient clinics, polyclinics with a psychiatrist or narcologists on staff, as well as psychiatric agencies that work under the jurisdiction of other governmental departments. Alongside these services (overseen by the Ministry of Health), long-term care for patients with neurological disorders, mental health disorders, and intellectual (and sometimes physical) disabilities is provided in institutions that fall under the auspices of the Ministry of Social Policy [Citation9]. As of 2019, there are 64.9 psychiatric beds per 100,000 population, a figure much higher than in European countries overall, but fairly in line with other Eastern European countries [Citation15]. As of 2019, there are a total of 7.9 narcological beds per 100, 000. and provide an overview of the total number of psychiatric and narcological beds in Ukraine in 2019.

Figure 1. Psychiatric beds per 100,000 population

Figure 2. Narcological beds per 100,000 population

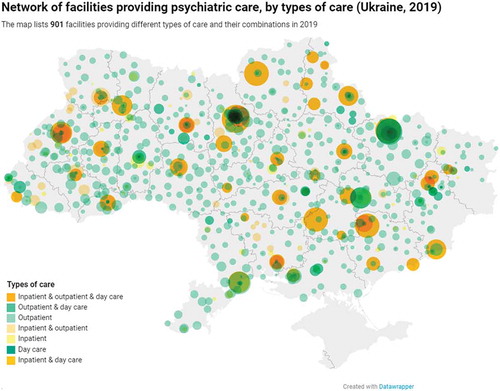

Community-based mental health services are formally available in Ukraine via the aforementioned network of outpatient cabinets, departments, and dispensaries, as well as day-stay departments in mental health, narcological, and non-specialized clinics. A large number of nurses work as psychiatric nurses in these settings too. For example, as of 31 December 2019, 8409 nurses were reported to be worked in outpatient mental health services across Ukraine [Citation16]. Nevertheless, these community-based services are not efficiently organized. For example, many of these services function as dispensaries (i.e., focusing on a specific illness or sphere, such as narcology, psycho-neurology), and are not always well integrated with other mental health or social services. These services are mostly located in big cities. The delivery of mental health care in primary care is also very limited [Citation9]. In terms of health service financing, it has been estimated that 89% of total mental health expenditure is allocated to inpatient services [Citation14]. details the facilities that participated in providing psychiatric care in 2019.

Figure 3. Network of facilities providing psychiatric care, by types of care

The quality of services delivered by the Ukrainian mental health system has been found to be variable, and in some instances has been rated as poor [Citation9]. For example, it has been reported that not all interventions delivered within the mental health system are evidence-based [Citation9]. Furthermore, the accessibility of services is hampered by high out-of-pocket (informal) payments [Citation9,Citation14]. High levels of stigma and low trust in medical professionals have also been reported as key barriers to use mental health services [Citation9]. These factors can be attributed (at least in part) to Ukraine’s history of Soviet rule, where stigmatizing conceptualizations of mental health were widely promoted, and psychiatry was sometimes used as a form of punishment and a tool of repression [Citation9]. However, the present-day social exclusion of a large number of individuals through institutionalization, alongside contemporary examples of human rights violations both in and outside these institutions [Citation9,Citation17,Citation18], has left many reluctant to engage with the mental health system as it currently operates.

In view of this, in its Concept Note on Mental Health [Citation6], the Ministry of Health of Ukraine outlined a number of key proposals for reform. Among these were the deinstitutionalization of the mental health system and a transition towards greater provision of mental health services within the community. The proposed changes to the Ukrainian mental health system comprise part of a broader reform agenda of the health system. This wide-ranging reform seeks to improve the quality and accessibility of all health services and includes financial reform, strengthening of primary care, and the adoption of internationally recognized guidelines for treating patients [Citation19]. Ukraine has already seen the successful implementation of a number of structural changes to its health system as part of the reform. A single purchaser of health services (the National Health Service of Ukraine, NHSU) was established in 2018, and the financing of the primary care sector was also reformed in 2018 [Citation20]. More recently, changes to the financing of the secondary care sector began to be implemented in April 2020. Over the course of 10 months, inpatient services will transition from input-based financing (line-item budgets) to a diagnostic-related group (DRG)-based system. It is planned that, by February 2021, all hospital-based services be contracted by the NHSU on a DRG basis.

The design of Ukraine’s financing reforms is in line with evidence and international good practices, and its focus on health financing mechanisms is seen as the most efficient way of effecting tangible change in service delivery [Citation20]. Reform of inpatient service financing presents – indirectly – a compelling opportunity to reshape mental health service delivery. Changing the way that mental health services are financed has been identified, across a number of studies in Central and Eastern European (CEE) and former Soviet countries, as a vital step for mental health system reform [Citation21,Citation22].

Countries across the world use a variety of financial mechanisms to ensure the efficient use of finite resources, and concurrently, the delivery of high-quality care [Citation23,Citation24] (see for a description of financial mechanisms typically used). Financial mechanisms can similarly be used to facilitate the optimal distribution of mental health services, as described by the WHO [Citation25]. The nature of these mechanisms naturally depends on the services that already exist within the health system, as well as the ‘legacy’ organizational and financial mechanisms in place to finance and regulate these services. There is a large body of literature on the various advantages and disadvantages of remuneration mechanisms regarding the behavioral incentives they create within a health system [Citation22,Citation26]. However, there is a lack of research on mechanisms that can be, or have been, implemented to facilitate a transition towards greater community-based service provision, particularly in lower- and middle-income health systems.

Table 1. Definitions of payment mechanisms

This study, therefore, had two aims. Firstly, to study mental health reforms undertaken in comparable health systems (specifically, CEE and/or post-Soviet countries), in particular, to identify the financing mechanisms implemented to facilitate enhanced mental health service delivery in the community. Secondly, to derive and formulate a set of recommendations for Ukraine’s mental health system, together with an assessment of the critical success factors for their sustainable implementation.

Methodology

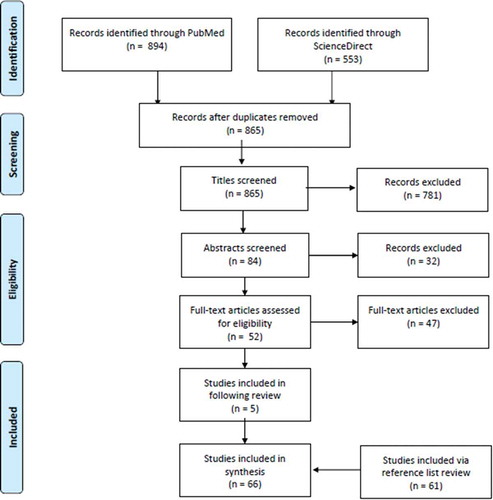

A comprehensive literature review was conducted to fulfil the study objectives. PubMed and ScienceDirect were used for the search. Snowballing was also used to identify any articles that may not have been identified via the systematic search. The literature search was conducted on 24 November 2019 and included source documents published from 2002 to 2019.

The identified articles were screened to determine whether they met the predefined inclusion criteria, namely:

Describe and/or evaluate broader government financing mechanisms, and/or the introduction or reform of organizational structures at the national/country level to incentivize or improve the delivery of mental health services in community-based settings.

Pertain to CEE and/or post-Soviet countries.

Reports and other non-peer-reviewed articles were included in the literature study, provided they met the inclusion criteria for the search. These resources were included in view of the number of reports and studies commissioned by governments or non-government agencies that are not formally published in a journal. Studies not published in the English language were excluded.

Results

A total of 865 articles were identified for review. Following the assessment of these articles and their reference lists against the inclusion/exclusion criteria, a total of 66 sources were included for analysis (see Appendix 1 for an overview). A table of included articles can be found in Appendix 2. Included literature pertained to the mental health systems of a total of 25 CEE and/or post-Soviet countries, namely, Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. This article presents a summary of the review’s key findings. Not all included articles have been referenced in the main body of the text.

Mental health service delivery in all CEE and/or post-Soviet countries included in this review typically takes place in a hospital-based environment. The majority of countries have issued mental health plans, indicating an intention to transition from institution-based service delivery to more community-based service delivery. Nevertheless, this review could only identify detailed information on reforms implemented in Bosnia and Herzegovina [Citation27–31], Georgia [Citation32], Lithuania [Citation33] and Moldova [Citation34]. In view of this, only broad themes on factors that facilitate and impede the implementation of community-based services could be derived.

Firstly, a well-articulated vision of how community mental health services will fit into the existing mental health system is key to facilitating the implementation of planned reforms. This should be supplemented by a roadmap for implementation, identifying key milestones to be reached, the required budget allocation to enable each milestone to be met, who is tasked with the responsibility of ensuring each milestone is met, and key indicators against which progress can be tracked. For example, in Bosnia & Herzegovina, a key aspect of the reform process involved aligning mental health legislation with European standards and designating community-based care as a leading principle for the organization of mental health services [Citation27]. Legislation also delineated the number of professionals to work in community mental health centers, as well as established an inspection and accreditation system to ensure the quality of institutions admitting mental health patients [Citation27]. On the other hand, among a number of the identified countries, policy documents pertaining to mental healthcare delivery and/or reform either did not exist or were unfocused and unspecific [Citation21].

Secondly, the way in which mental health services are financed can inhibit greater community-based service provision. A number of countries, such as Russia [Citation35–38], finance mental health services using input-based (line-item, fee-for-service) financing [Citation39–44], which neither incentivize the provision of quality services nor are responsive to population needs. Rechel et al. note that such financing structures are ‘a major cause of inefficiency’ (p62 [Citation45]), with mental health care in these countries characterized by lengthy hospitalization and repeat admissions. The payment of staff and infrastructure-related costs (such as heating) according to line-item budgets encourages the preservation of large hospitals and the hospitalization of patients [Citation38]. ‘Active’ or ‘strategic’ purchasing of health services, namely adapting payment mechanisms and funding allocations according to population needs and provider performance, has been identified as a way of improving the quality and efficiency of health services [Citation22,Citation46,Citation47]. Theoretically, ‘active’ and ‘strategic’ purchasing can be implemented using a range of financing mechanisms. A requirement, however, is that it is underpinned by accurate and reliable health information systems [Citation23,Citation46], and is supported by an empowered regulatory body [Citation23,Citation46].

Thirdly, a lack of collaboration between the health and social sector has been found to impede the implementation of community-based services. Despite the same patients engaging with both social and healthcare services, there often remains ineffective communication between the two sectors [Citation48]. Fragmentation in the system creates incentives that impede the quality of care delivered to patients. For example, pressure to reduce the number of mental health hospital beds, coupled with the absence of alternatives in the community, leads to patients being admitted to social care homes [Citation21]. In view of this, McDaid et al. argue that any reform that seeks to enhance community-based mental healthcare provision requires extensive collaboration between the health and social sectors [Citation49]. However, administrative laws and financing regulations often hamper such collaboration, including the pooling of health and social care budgets [Citation38]. Moreover, the scope of mental health reforms in most countries has not been extended to include the social sector [Citation21,Citation27,Citation29,Citation34,Citation50].

Finally, insufficient resourcing of health systems, and in particular, their mental health sub-systems, impedes mental health reform [Citation48,Citation51]. Ultimately very few, if any, resources are available to finance mental health system development and/or reform [Citation48]. On top of this, not only do community services need to be either strengthened or established; the existing infrastructure of hospital-based services requires significant investment [Citation48]. The situation is further exacerbated by a lack of protection or ring-fencing of mental health budgets, particularly where mental health hospitals are closed [Citation52]. It is argued that ‘double’ or ‘transitional’ funding is required to facilitate the effective transition from institution-based to community-based care [Citation52,Citation53]. Such additional funding allows for the provision of existing mental health services, whilst developing the required infrastructure in the community setting [Citation53].

Discussion

Despite the limited literature on organizational and financing mechanisms implemented in CEE and/or post-Soviet countries, this study highlights a number of opportunities for Ukraine to move away from its institutionalized model of mental health care. Recommendations for Ukraine’s next steps are discussed in turn.

Adopt a clear policy framework, delineating a vision for community-based care, and timeframes for its implementation

A concept for the reform of the mental health system in Ukraine was devised and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers in 2017. This concept has been discussed widely by mental health professionals, as well as national and international representatives, and it has been used to devise a mental health action plan. However, this action plan has not yet been approved by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine. A document that distils when and how mental health reform will be realized is therefore lacking.

Invest in mental health system reform

As Medieros et al. note, the development of policies and passing of legislation alone are insufficient to garner real change in service provision [Citation52]. The development of community-based care requires investment by the government to create new services, repurpose old facilities, as well as train professionals to shape service delivery [Citation52,Citation53].

It was estimated, in a 2015 WHO report, that 2.5% of health expenditure in Ukraine is spent on mental health services, which – whilst comparable to its neighbors – is deemed insufficient from a needs-based perspective [Citation14]. Given the well-recognized poor quality of mental health infrastructure in Ukraine [Citation9,Citation14,Citation54], significant investment will be required to reform the Ukrainian mental health system. Transitional funding will facilitate a more effective reform of mental health services. The optimal approach would be for community-based services to be established prior to the closure or reconfiguration of hospital-based services [Citation9].

Total mental health expenditure in Ukraine should also gradually be brought into line with its European neighbors. Given the current low prioritization of mental health, as well as the relative instability of health reforms, a clear budget allocation for mental health services would signify a clear commitment to improving mental health service provision. It would also provide a degree of stability during the course of mental health reform.

Implement financing mechanisms that redress the inefficiency of current mental health financing structures

It has been estimated that 89% of mental health expenditure is spent on inpatient mental services [Citation9]. According to a recent review of the Ukrainian mental health system, inpatient services are predominantly provided in urban centers. There is insufficient coverage of mental health services within rural areas [Citation9], and the majority of long-stay facilities are isolated from the community and local infrastructure.

This allocative inefficiency in service provision is attributed to the way in which mental health services have been financed [Citation9,Citation14,Citation54]. Regional and local authorities receive funds to finance their services according to line-item budgets, based on their facilities’ capacity, as opposed to the true costs associated with delivering care [Citation9,Citation14,Citation55]. This has led to inefficiency, waste, and services that are not responsive to population needs. Furthermore, it has increased the demand for funding without increasing efficiency [Citation55].

Ukraine needs to adopt more active purchasing strategies, in order to improve the quality and efficiency of its services [Citation46]. Firstly, the allocation of funds to local and regional authorities should be based on the needs of the population, as opposed to the mere capacity metrics of service providers. Secondly, funding for mental health services should follow the patient in their journey through the health and social care system.

The financing mechanisms used within the Ukrainian health system are under reform at the time of writing. Changes made to date include the institution of a capitation system for the financing of primary care services. Reforms to the financing of secondary health services were implemented from April 2020, with a view to implementing DRG-based payments for all secondary services (with scope for these being applied to mental health services as well).

To facilitate the integration of mental health services into primary care, the current bundle of services – agreed by primary care providers and the NHSU and financed through capitation – could be expanded to include essential mental health services. This could be undertaken using the mental health gap action program (mhGAP), a WHO program that seeks to scale up mental health services in low- and middle-income countries through capacity building of primary care service providers [Citation56]. In addition to this, community-based mental health centers could also be financed via capitation, contracted by the NHSU to provide an agreed volume and quality level of services. The NHSU would need to define criteria for such a tender model, including provider eligibility, service volume, quality standards, and contract duration. Initial funding would need to be provided for their establishment phase, as currently, very few community-based mental health centers exist. While district psychiatrists, narcologists, and nurses currently work in the community, their functions differ from those of community-based mental health centers. The establishment of community-based mental health centers, supported by training and capacity building, would allow for the more efficient utilization of their skills.

Finally, the application of DRGs in the hospital setting should not reward lengthy hospitalization, nor should it incentivize providers to discharge their patients too quickly. To achieve this, DRGs should reward hospital-based services for providing care in outpatient-settings as appropriate, as well as collaborating with, and referring patients to, community-based providers.

Prioritize collaborative planning and delivery of community-based mental health services

The planning of mental health services, and specifically the provision of care in the community, should be jointly undertaken by the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Social Policy, and communities. Representatives working in education, justice, and the military should also be included in service planning. In particular, it is vital that both sectors be involved in the reduction of hospital beds, to avoid the inappropriate discharge of patients from the health or social sector when community-based services are unavailable.

Budgets should be pooled to facilitate this. This has already been suggested by two key reviews of the Ukrainian health system [Citation9,Citation20]. Efforts could be conducted at the regional level, with regional authorities empowered to purchase primary and secondary care services for their respective populations [Citation55]. Community-based mental health services could be funded by a joint health and social care budget (both state and local), utilizing funds currently allocated to the financing of social care homes and a portion of the total health budget. This budget would be used to finance services such as community-based mental health centers, multi-disciplinary teams working independently, or alongside primary care, as well as supported residential facilities. Given the regional health and social care authorities are tasked with the purchase and provision of services for their respective populations, it would be most efficient to empower these authorities to deploy the pooled budgets jointly. Such an approach would also promote an integrated and balanced approach to service planning, and emphasize the development of strong referral networks and pathways between primary, community-based, and inpatient services.

Empower regional authorities to collaborate in the strategic purchase of mental health services that are in line with the needs of their population

egional and local authorities in Ukraine own, and are responsible for, the delivery of mental health services within their respective regions, including the utility costs and maintenance of health facilities [Citation9,Citation20,Citation55]. Ongoing reforms will see the NHSU responsible for the purchasing of all primary and secondary care services [Citation20]. Given that local governments own and manage most healthcare infrastructure, which are responsible for local public health spending and have the greatest understanding of the local context and their populations’ needs, the NHSU and regional authorities should collaborate in the purchase of mental health services for their populations. Such collaboration should include regional strategic planning (including the required immediate investment in health infrastructure and human resource development), as well as the sharing of data pertaining to health service provision.

Improve the collection and dissemination of health information

Since its establishment, the NHSU has been developing an integrated health information system to monitor service delivery and support quality assurance within the health system (see, for example, https://cmhmda.org.ua/form_10_database/). An e-health system, currently being developed by the Ministry of Health, is envisaged to support the NHSU in its purchasing of health services [Citation20]. This system will be linked to the enrolment databases of health providers contracted by the NSHU. However, information collected at any service level is not always accurate [Citation14]. The e-health information system that is currently being implemented does not integrate with other national registers, nor does it allow for the updating of key information, such as birth and mortality data [Citation20]. The collection and dissemination of health information, in particular for the purposes of enhancing health service purchasing, should therefore be improved. Health information should also be more accessible and user-friendly for health service providers.

Feasibility of implementing these recommendations in Ukraine

The ongoing public sector reforms as well as broader health system reform in Ukraine represent a great opportunity to implement the identified recommendations for mental health reform in Ukraine. These reforms are popular components of the current policy agenda in Ukraine [Citation57], and the design of Ukraine’s financing reforms is in line with evidence and international good practices [Citation20]. Furthermore, great strides have been made in the implementation of several aspects of Ukraine’s health system reform, providing a strong foundation for further health system development. The speed with which these changes were implemented is remarkable. Continued momentum and further successes in the implementation of broader health reforms may facilitate reform of the mental health system.

Nevertheless, there are a number of key challenges that will need to be overcome in order for mental health reform in Ukraine to be realized. Firstly, there are many actors more interested in preserving the existing organization of the health system, than in facilitating improvements [Citation55]. The current arrangement of the system carries financial and status-related benefits for a number of stakeholders, and implementation of financial reform within the health system has generated resistance among these stakeholders, including medical professionals and specialist physicians [Citation20,Citation54,Citation58]. Secondly, health system reform has been, and continues to be, threatened by political instability. The political instability of the Cabinet of Ministers has also subverted the introduction of multiple regulations proposed by the Ministry of Health in the past two decades [Citation58]. Thirdly, it cannot be understated that – in order for the reform to have a demonstrable impact on the availability and quality of health services, including mental health services – continued investment in the health system is needed. Funds allocated to the health system need to be increased [Citation55]. Reform to date has been undertaken in a tight fiscal environment, with the understanding that there is limited scope for increased funding for health [Citation20]. The long-term availability of funds for the health system, as well as the funding required to implement all planned components of the reform, depends on the stability of the Ukrainian economy [Citation20,Citation54]. However, the Ukrainian economy remains weak [Citation57], presenting a number of challenges for the Ukrainian government, not least the financing of health reform. Fourthly, the broader issue of corruption in Ukraine represents a significant challenge to reform. Attempts to modernize the Ukrainian public sector and ensure its competitiveness in global markets have been hampered by the interests of highly influential private individuals [Citation54]. Given health reforms pursue the same objectives as the anti-corruption agenda, including greater transparency and the reduction of informal payments [Citation20], they also are under the threat of private interests. Finally, war in the eastern regions of Ukraine provides additional economic and social challenges for the Ukrainian government [Citation14,Citation54], and the implementation of administrative and health reform is naturally hampered by the ongoing conflict.

In view of these challenges, implementing the seven recommendations outlined in this study represents a long-term goal. The first priority for Ukraine in the immediate term is for a vision for mental health reform to be agreed, supported by an outline of the stages and timeline of its implementation. The steps thereafter should include the delineation of the type and volume of mental health services to be included under a package of services financed by the NHSU. Key indicators and reporting timeframes should be devised in order to track and publicize progress.

Beyond Ukraine, further empirical evidence is needed on the financial and organizational mechanisms that incentivize the delivery of community-based mental health care. There is only very scant literature on mental health reform in CEE and/or post-Soviet countries. Further research in these countries would provide useful insights for those seeking to pursue greater provision of mental health services in community-based settings.

Strengths and weaknesses

Whilst this study drew on a wide variety of sources, including peer-reviewed journals and grey literature, potentially relevant information could have been contained in sources that were excluded on the basis of their publication in another language (i.e., not in English). The WHO’s resources on health systems provided the basis of the analysis of a number of countries included in this review. This is not necessarily a weakness, as the WHO often has extensive access to a country’s information systems and statistical data. However, the reports for some countries that were included in this analysis were around 10 years old and therefore may not represent the more recent developments taking place in these countries. Finally, it is worth noting that a key aspect of health systems is the people working in them. Delineation of the tasks in each profession should perform, as well as the competencies required to undertake these tasks, comprise a vital aspect of any health system. The reform of these aspects, as well as the education and accreditation systems that support the competence of professionals, therefore represent key opportunities for improving the quality and efficiency of a health system. Research considering the specific changes in human resource planning and training to facilitate the delivery of community-based care would provide complementary insights to those provided by this review.

Conclusions

The mental health system in Ukraine, as it functions currently, is rather unresponsive to the significant mental health needs of the Ukrainian population. Broader health system reform currently underway in Ukraine represents progress towards a health system that is more responsive to the needs of its population. Moreover, the Ministry of Health’s commitment to mental health reform as a key component of these broader reforms provides a foundation for transitioning towards greater community-based service provision. Delineation of a vision for mental health reform needs to be prioritized and supplemented by a clear roadmap for its implementation. Key indicators and reporting timeframes are required to allow for the tracking of progress. Reforms that prioritize the financing of services whereby ‘money follows the patient’ should continue to be implemented.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heiko Königstein (Project Leader of the Mental Health for Ukraine project) for his insightful contributions to drafts of this manuscript. This study was conducted following an internship with the Mental Health for Ukraine project, a project made possible with the support of Switzerland through the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC). The project aims to improve mental health outcomes among the Ukrainian population. It is jointly implemented by a consortia comprised of GFA Consulting Group GmbH, Implemental Worldwide C.I.C., University Hospital of Psychiatry Zurich, and Ukrainian Catholic University Lviv.

Disclosure statement

The opinions and views presented in this publication represent those of the authors and may not necessarily represent the views of the Ukrainian Catholic University, the Centre for Mental Health and Monitoring of Drugs and Alcohol Ministry of Health of Ukraine, Mental Health for Ukraine project team, the Mental Health for Ukraine project implementing consortia, the SDC, the Hamburg University of Applied Sciences nor the DAAD.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Narcology refers to psychiatric care for people with mental health disorders due to substance use.

References

- Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–15.

- World Health Organization, editor. Mental health: new understanding, new hope. repr. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. p. 178. (The world health report).

- World Health Organization. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective; 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Balancing community-based and hospital-based mental health care. World Psychiatry Off J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2002 Jun;1(2):84–90.

- Thornicroft G, Tansella M. Components of a modern mental health service: a pragmatic balance of community and hospital care: overview of systematic evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185(4):283–290.

- Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Concept note of the state targeted mental health program in Ukraine lasting till 2030 [Internet]. Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine; 2017 Dec. Available from: http://www.moz.gov.ua/ua/portal/#2

- Bromet EJ, Gluzman SF, Paniotto VI, et al. Epidemiology of psychiatric and alcohol disorders in Ukraine: findings from the Ukraine world mental health survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005 Sep;40(9):681–690.

- Tintle N, Bacon B, Kostyuchenko S, et al. Depression and its correlates in older adults in Ukraine. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(12):1292–1299.

- Weissbecker I, Khan O, Kondakova N, et al. Mental health in transition: assessment and guidance for strengthening integration of mental health into primary health care and community-based service platforms in Ukraine (English) [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2017 Oct [cited 2019 Mar 2]. (Global Mental Health Initiative). Available from: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/310711509516280173/Mental-health-in-transition-assessment-and-guidance-for-strengthening-integration-of-mental-health-into-primary-health-care-and-community-based-service-platforms-in-Ukraine

- Kuznestsova I, Mikheiva O, Catling J, et al. The mental health of IDPs and the general population in Ukraine. Briefing Paper. 2019.DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.2585564

- Roberts B, Makhashvili N, Javakhishvili J, et al. Mental health care utilisation among internally displaced persons in Ukraine: results from a nation-wide survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019 Feb;28(1):100–111.

- Colborne M. Ukraine struggles with rise in PTSD. Can Med Assoc. 2015;187(17):1275.

- Kyiv International Institute of Sociology. Mental health in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2020 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/operations/ukraine/document/mental-health-donetsk-and-luhansk-oblasts-2018

- Lekhan V, Rudiy V, Shevchenko M, et al. Ukraine: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. (Health Systems in Transition).

- Samele C, Frew S, Urquia N Mental health systems in the European Union member states, status of mental health in populations and benefits to be expected from investments into mental health: European profile of prevention and promotion of mental health (EuroPoPP-MH) [Internet]. European Commission; 2013. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/mental_health/docs/europopp_full_en.pdf

- Statistical form 10 - Report on Psychiatric Care 2019 [Internet]. Center for Mental Health and Monitoring of Drugs and Alcohol Ministry of Health of Ukraine. [ cited 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://cmhmda.org.ua/category/statistic/zvedena-forma-10/

- Keukens R. Review of social care homes in Ukraine and the development of a plan of action. Hilversum: Federation of Human Rights in Mental health (FGIP); 2017.

- Council of Europe. Report to the Ukrainian government on the visit to Ukraine carried out by the European committee for the prevention of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment (CPT) from 8 to 21 December 2017. Strasbourg: Council of Europe; 2018 Sep.

- National Health Reform Strategy for Ukraine 2015-2020 [Internet]. Kiev (Ukraine): Ministry of Health; 2015 [cited 2019 Aug 19]. Available from: https://healthsag.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Strategiya_Engl_for_inet.pdf

- World Health Organization, World Bank. Ukraine review of health financing reforms 2016-2019 [Internet]. Copenhagen (Denmark): World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 2020 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/416681/WHO-WB-Joint-Report_Full-report_Web.pdf?ua=1

- Petrea I. Mental health in former Soviet countries: from past legacies to modern practices. Public Health Rev. 2012;34(2):5.

- Langenbrunner JC, O’Duagherty S, Cashin CS. Designing and implementing health care provider payment systems: ‘ how-to’ manuals. Washington D.C.: The World Bank; 2009.

- Kutzin J, Witter S, Jowett M, et al. Developing a national health financing strategy: a reference guide [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 23]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/254757/1/9789241512107-eng.pdf?ua=1

- Knapp M, McDaid D. Financing and funding mental health care services. Mental Health and Policy Practice in Europe. 2007;p 60-99.

- World Health Organization. The optimal mix of services [Internet]. Geneva (Switzerland); 2007 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/

- Cashin C, Ankhbayar B, Phuong HT. Assessing health provider payment systems: a practical guide for countries working toward universal health coverage. Washington, DC: Joint Learning Network for Universal Health Coverage; 2015.

- Placella E. Supporting community-based care and deinstitutionalisation of mental health services in Eastern Europe: good practices from Bosnia and Herzegovina. BJPsych Int. 2019 Feb;16(1):9–11.

- Sinanovic O, Avdibegovic E, Hasanovic M, et al. The organisation of mental health services in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int Psychiatry. 2009;6(1):10–12.

- Kucukalic A, Dzubur-Kulenovic A, Ceric I, et al. Regional collaboration in reconstruction of mental health services in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(11):1455–1457.

- De Vries AK, Klazinga NS. Mental health reform in post-conflict areas: a policy analysis based on experiences in Bosnia Herzegovina and Kosovo. Eur J Public Health. 2006 Jun 1;16(3):246–251.

- Cain J, Duran A, Fortis A, et al. Health care systems in transition: bosnia and Herzegovina. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2002.

- Sulaberidze L, Green S, Chikovani I, et al. Barriers to delivering mental health services in Georgia with an economic and financial focus: informing policy and acting on evidence. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Dec;18(1):108.

- Murauskiene L, Janoniene R, Veniute M. Lithuania: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. (Health Systems in Transition).

- Petrea I, Shields-Zeeman L, Keet R, et al. Mental health system reform in Moldova: description of the program and reflections on its implementation between 2014 and 2019. Health Policy. 2020 Jan;124(1):83–88.

- Popovich L, Potapchik E, Shishkin S, et al. Russian federation: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. (Health Systems in Transition).

- Krasnov V, Gurovich I, Bobrov A. Russian federation: mental healthcare and reform. Int Psychiatry. 2010;7(2):39–41.

- Shek O, Pietilä I, Graeser S, et al. Redesigning mental health policy in post-soviet Russia: a qualitative analysis of health policy documents (1992-2006). Int J Ment Health. 2010;39(4):16–39.

- McDaid D, Samyshkin YA, Jenkins R, et al. Health system factors impacting on delivery of mental health services in Russia: multi-methods study. Health Policy. 2006 Dec;79(2–3):144–152.

- Ibrahimov F, Ibrahimova A, Kehler J, et al. Azerbaijan: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. (Health Systems in Transition).

- Golubeva N, Naudts K, Gibbs A, et al. Psychiatry in the Republic of Belarus. Int Psychiatry. 2006;3(3):11–13.

- Richardson E, Malakhova I, Novik I, et al. Belarus: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. (Health Systems in Transition).

- Lecic Tosevski D, Pejovic Milovancevic M, Popovic Deusic S. Reform of mental health care in Serbia: ten steps plus one. World Psychiatry Off J World Psychiatr Assoc WPA. 2007 Jun;6(2):115–117.

- Khodjamurodov G, Sodiqova D, Akkazieva B, et al. Tajikistan: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. (Health Systems in Transition).

- Ahmedov M, Azimov R, Mutalova Z, et al. Uzbekistan: health system review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. (Health Systems in Transition; vol. 16).

- Rechel B, Richardson E, McKee M. Trends in health systems in the former Soviet countries. Copenhagen: European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2014.

- World Health Organization, editor. Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage. Geneva: The world health report; 2010. p. 106.

- Feldhaus I, Mathauer I. Effects of mixed provider payment systems and aligned cost sharing practices on expenditure growth management, efficiency, and equity: a structured review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 Dec;18(1):996.

- Dlouhý M, Barták M Mental health financing in six eastern European countries. Ekonomie [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2019 Dec 23]. Available from: http://www.ekonomie-management.cz/download/1404732056_e98f/2013_4+Mental+Health+Financing+in+Six+Eastern+European+Countries.pdf

- McDaid D. Mental health reform: europe at the cross-roads. Health Econ Policy Law. 2008;3(3):219–228.

- Makhashvili N, van Voren R. Balancing community and hospital care: a case study of reforming mental health services in Georgia. PLoS Med. 2013 Jan 8;10(1):e1001366.

- Winkler P, Krupchanka D, Roberts T, et al. A blind spot on the global mental health map: a scoping review of 25 years‘ development of mental health care for people with severe mental illnesses in central and eastern Europe. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017 Aug 1;4(8):634–642.

- Medieros H, McDaid D, Knapp M. Shifting care from hospital to the community in Europe: economic challenges and opportunities. London: PSSRU; 2008.

- Muijen M, McCulloch A. Reform of mental health services in Eastern Europe and former Soviet republics: progress and challenges since 2005. BJPsych International. 2019 Feb;16(1):6–9.

- Romaniuk P, Semigina T. Ukrainian health care system and its chances for successful transition from Soviet legacies. Glob Health. 2018 Dec;14(1):116.

- Lekhan V, Rudiy V, Shishkin S. The Ukrainian health financing system and options for reform. Copenhagen (Denmark): World Health Organization; 2007.

- World Health Organization. mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance-use disorders in non-specialized health settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- World Bank. Ukraine systematic country diagnostic: toward sustainable recovery and shared prosperity (English) [Internet]. Washington (DC): World Bank Group; 2017 [cited 2020 Jan 24]. (Systematic Country Diagnostic). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1596/27148

- Semigina T, Mandrik O. Drug procurement policy in Ukraine: is there a window of opportunity? Bull APSVT. 2017;1:25–38.