ABSTRACT

Background: The practice of non-medical switch (NMS) from a reference biological (originator) to a biosimilar is widely accepted in some countries. However, there is little documentation on the impact of NMS from one originator to another originator.

Objectives: To assess the consequences for patients of NMS from one biological originator to another, based on existing literature. The focus was on efficacy and cost of treatment with TNF-α-inhibitors in three disease areas.

Methods: A literature search was conducted in Ovid (PubMed, EMBASE) and abstracts from meetings in key therapeutic areas, to identify studies reporting efficacy, safety or costs by switching between originator biologics.

Results: 167 references were identified and abstracts screened; 36 papers reviewed in full text, and 6 fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Three clinical studies of NMS had very small sample sizes, but suggested that NMS is beneficial. The remaining three studies used administrative data with little clinical information, indicating that NMS was disadvantageous and associated with increased health care utilization and costs.

Conclusions: There is very limited documentation on NMS from one originator biological to another, and the literature suffers from methodological limitations. The results are mixed and preclude drawing an overriding conclusion. Future studies, are warranted.

Introduction

Biological medicines (biologics) are medicines made in living systems. Biosimilars are biologic drugs that are highly similar to an already registered biologic drug, a reference medicine [Citation1]. They are, however, made by different sponsors using independently derived cell lines and separately developed manufacturing processes. For the approval of biosimilars in the EU, the European Medicines Agency has provided a detailed guideline [Citation2].

Concerns have been raised that switching patients from reference medicines (originators) to biosimilars, or other structurally related biologics, may lead to increased immunogenicity and consequential safety problems [Citation3], or even a loss of efficacy. Similarly, switching patients from one reference biological to another reference biological in the same group (or the biosimilar of the other reference biological) may raise concerns. Switching between biologicals may also be differentiated based on the reason for switching. If a switch is motivated by a lack of effect or side-effects, this will not raise the same concerns. If a switch is for non-medical causes, (non-medical switch, NMS), such as pressure or incentives from funders to contain costs [Citation4], physicians and patients may be more concerned [Citation5–7].

For patients that are stable or in remission, switching poses a risk of decreased effectiveness or increased side effects. There is considerable documentation on the impact of NMS from an originator to a biosimilar of the same substance, e.g., on the bioavailability, safety, efficacy and challenges of such change [Citation8–12]. The practice of NMS to a biosimilar is widely accepted in some countries, in particular when starting biological treatment, but NMS in stable patients/in remission is also practiced [Citation10].

When there is unsatisfactory control, e.g., a TNF-α-inhibitor (TNFi), there are several options: 1) adjust the dosage of the biological, 2) adjust the interval between the administrations, 3) add another type of immune modulating drug, or 4) switch to another TNFi. If the switch to another originator is motivated by medical reasons such as unsatisfactory control or side effects, this is normally considered acceptable and uncontroversial [Citation13]. There is, however, little documentation on the impact of NMS from one originator to another originator biological, i.e., a different substance with a different effect.

The objective of this review was to assess the consequences for patients of switching from one biological originator to another originator or a new mode of action for non-medical reasons, based on existing documentation in the literature. The review concentrates on the following therapeutic areas: rheumatology, gastrointestinal diseases and dermatology.

Methods

Literature search

A systematic literature search was conducted in Ovid (PubMed, EMBASE) to 8 January 2021 to identify studies reporting efficacy and/or safety data on switching between originator biologics.

The literature search and the presentation of the search strategy were modelled after previous related reviews of switching therapy between reference and biosimilars [Citation8,Citation14]; however, the focus of the present paper is different from those studies.

Records were retrieved using the title and abstract (‘ti, ab”) search filter, as well as limiting to English language. The detailed specification with result of the search is listed in Appendix 1 and 2.

In addition, the following meetings from the main societies representing key therapeutic areas were checked for relevant abstracts published in 2015–2020: European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO); Digestive Disease Week (DDW); European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR); American College of Rheumatology (ACR); and The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR), see Appendix 3 for details.

The reference lists of some of the identified primary articles and literature reviews were hand searched for any additional, potentially relevant articles. To supplement the searches, an exploratory literature search was undertaken to support the overview section around the principles of biologics, NMS and interchangeability. Finally, papers previously provided by UCB, Norway were included.

Literature review

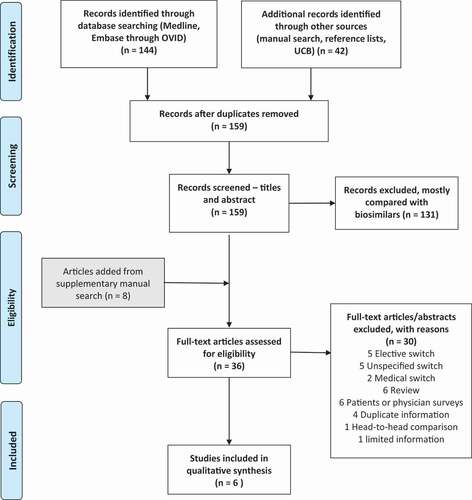

The references of 186 papers were collected in a reference management program (Endnote), and duplicates were eliminated. Then, they were transferred to Rayyan QGRI (https://rayyan.qcri.org/) for manual review of title/abstract of the papers by the author. The major selection criteria for the inclusion of papers in the review were: studies of adult patients (≥18 years) with inflammatory arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) or psoriasis, who switched from an originator biological to another originator biological medicine. Both clinical studies and observational studies were eligible for inclusion. Only studies of humans and published in the English language were included. The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in and a flow chart of the process in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We collected information on reason for switching, type of publication, publication year, study characteristics, patient category/disease, number of patients, medication used, and the major outcomes in the articles that were included.

Results

Identified studies

Overall, 167 abstracts, including 8 from manual search of reference lists, were reviewed in the Rayyan software, and 131 papers were excluded, most because the topic of the paper involved switch to biosimilar(s). In total, 36 papers were reviewed in full-text in EndNote, or the abstract re-reviewed if from a conference proceeding, to decide on further eligibility.

Full text review

When reviewing the 36 papers in full text, a further 30 papers were excluded for the following reasons (): 5 elective switch (e.g., switching from one reference biological that was administered intravenously to one that could be administered subcutaneously (faster or possibly at home) by provider or patient choice, 5 unspecified switch between reference medicines (reason for switching not specified or predominantly medical switch, i.e., for a medical reason, most often register-based study), 2 medical switch, 6 review article, 6 patients or physician surveys (e.g., online or telephone surveys), 4 duplicates of other papers (e.g., abstracts presented for different audiences or duplicating a full-length paper), 1 head-to-head comparison (in biologic-naïve patients), 1 too limited information in an abstract only. Therefore, six papers were left for qualitative analysis ().

Table 2. Included articles on non-medical switch of originator biologicals

Experience of non-medical switch

Only six papers evaluated the impact of switch from one originator to another originator biological. Four of the included papers focused on shift from one TNFi to other TNFi’s [Citation15–18], one paper on shift from one TNFi to another TNFi or discontinuation [Citation19], and the last paper dealt with switch from a TNFi to another TNFi or a biological with a different mechanism of action (interleukin inhibitor) [Citation20].

Two of the papers were retrospective clinical studies from the same study of Crohn’s disease in a special situation prompted by a pharmacy directive leading to an administrative switch of medication. The studies presented different follow-up periods, reporting that 45/60 patients (75%) were in clinical remission and had a successful switch after 1 year, and 25/45 (55%) after 2 years [Citation15,Citation18].

Another retrospective study was a clinical follow-up of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in one Finnish center that switched between originator biologicals for different reasons. In this study, only 23 (46%) patients switched for non-medical reasons, specified as by patient-choice or transfer from inpatient to outpatient treatment. The 1-year drug survival rate for etanercept in those that switched from infliximab for non-medical reasons in this group was 77%, which was numerically higher but statistically not significantly different from that of those that switched from infliximab because of infliximab failure of adverse effects [Citation17].

The remaining papers were studies from administrative databases/health records in pooled patient populations with inflammatory arthritis, IBD or psoriasis [Citation16,Citation19,Citation20]. These studies assessed the impact of NMS on health care utilization, showing an increased health care utilization or costs [Citation16,Citation19,Citation20] and displayed indications of diminished efficacy [Citation16,Citation19] in NMS compared to non-switchers/maintainers.

One of the studies reported higher rates of medication-related adverse effects after NMS than in matched controls over several time periods [Citation16]. The other studies reported adverse events as reasons for discontinuation, without statistical comparison between the groups [Citation15,Citation18], or did not report safety or adverse events [Citation19,Citation20] or for relevant subgroup [Citation17].

Discussion

The few clinical studies of NMS between reference biologicals identified in the literature search had very small sample sizes, but seemed to suggest that NMS is possible and occurs at a small scale [Citation15,Citation17,Citation18]. In contrast, the included non-clinical studies were primarily based on administrative data with little clinical information, and these studies indicated that NMS was disadvantageous and associated with increased health care utilization and increased costs [Citation16,Citation19,Citation20].

However, the current literature on NMS between reference biologicals is very limited and heterogeneous in scope, methods, outcomes, substances included and results, although TNFi’s were included in all six identified studies. Because of this heterogeneity it was not feasible to combine study results in a meta-analysis.

In spite of efforts to adjust the findings for possible confounders by regression analysis or matching, there is probably an inherent bias in some of the studies, e.g., that patients switching medication will be expected to have more frequent follow-ups than stable patients not switching, thus leading to increased health care utilization and increased costs, as suggested by higher rates of physician office visits after NMS than in matched non-switchers [Citation16]. None of the studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which by design would control for unobserved variables.

In administrative databases or retrospective reviews, the reasons for switching might be multiple or unclear, possibly leading to misclassification. Because of these methodological challenges and the very limited data, these findings should be interpreted with caution, and RCTs are warranted. The literature search was wide and primarily conducted in two databases, however, we still might have missed some publications.

We are not aware of other studies of NMS between originator biologicals than those included, therefore we can only compare the findings with switches for other reasons between originator biologicals, such as change from an originator biological requiring intravenous administration to another with subcutaneous administration, for convenience by patient or provider choice (elective switch) [Citation21–25]. These studies were all small clinical studies in RA or IBD, some of which reported that switch was safe and acceptable [Citation22,Citation25]. In contrast, one trial reported that 47% of patients switched from infliximab to adalimumab required increased dosages or discontinued treatment early compared to those remaining on infliximab and cautioned against switching for other reasons than loss of effect or tolerance [Citation23]. These studies may have an inherent bias in that the switchers were selected because they were motivated to switch. Furthermore, these studies represent a different motivation for switching than NMS in patients with stable/controlled disease, which is the topic of this brief review.

Some other studies have reported results from switching between different originator biologicals, typically from a TNFi, without specifying the reason for switching [Citation26–29]. Most of these studies comprised patients with RA, were observational, database/register-based studies with less detailed documentation, some of which reported increased costs from switching [Citation28,Citation29]. In contrast, two studies reported mixed results depending on comparators [Citation26] or outcome [Citation27], and no difference in disease activity [Citation27]. These studies were heterogeneous in medications compared, outcomes assessed and analytic methods, and most important, the reasons for switching was not given. Therefore, the scope of these studies was different from the primary focus of this review, and one should be careful about extrapolating the results to other reasons for switching.

Finally, it should be noted that a previous review of NMS, although with a wider scope than the present study and including studies of NMS in general, pointed at mostly neutral or negative effects of NMS on clinical outcomes, health care utilization, costs, or medication adherence [Citation4]. In a subgroup of studies of patients with stable/well-controlled disease, there was little positive association between NMS and any of the above outcomes.

In conclusion, there is little solid documentation on NMS from one originator TNFi to another. The results seem to be mixed. The existing literature is very limited and suffers from apparent methodological weaknesses. Therefore, it is difficult to aggregate the data and draw an overriding conclusion. Future studies, preferably RCTs, are warranted.

Role of the sponsor

The sponsor was involved in problem formulation, but had no influence on the literature search, data extraction, analysis, interpretation, or writing of the paper.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (155 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Biosimilar biologic drugs in Canada: Fact Sheet Ottawa, Canada: Government of Canada; 2019 Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/brgtherap/applic-demande/guides/Fact-Sheet-EN-2019-08-23.pdf

- Guideline on similar biological medicinal products London: european medicines agency; 2014 Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-similar-biological-medicinal-products-rev1_en.pdf

- McKinnon RA, Cook M, Liauw W, et al. Biosimilarity and interchangeability: principles and evidence: a systematic review. BioDrugs. 2018;32(1):27–8.

- Nguyen E, Weeda ER, Sobieraj DM, et al. Impact of non-medical switching on clinical and economic outcomes, resource utilization and medication-taking behavior: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(7):1281–1290.

- Costa OS, Salam T, Duhig A, et al. Specialist physician perspectives on non-medical switching of prescription medications. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020;8(1):1738637.

- Coleman C, Salam T, Duhig A, et al. Impact of non-medical switching of prescription medications on health outcomes: an e-survey of high-volume medicare and medicaid physician providers. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2020;8(1):1829883.

- Weeda ER, Nguyen E, Martin S, et al. The impact of non-medical switching among ambulatory patients: an updated systematic literature review. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1678563.

- Feagan BG, Lam G, Ma C, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of switching patients between reference and biosimilar infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(1):31–40.

- Feagan BG, Marabani M, Wu JJ, et al. The challenges of switching therapies in an evolving multiple biosimilars landscape: a narrative review of current evidence. Adv Ther. 2020;37(11):4491–4518.

- Moots R, Azevedo V, Coindreau JL, et al. Switching between reference biologics and biosimilars for the treatment of rheumatology, gastroenterology, and dermatology inflammatory conditions: considerations for the clinician. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2017;19(6):37.

- Inotai A, Prins CPJ, Csanadi M, et al. Is there a reason for concern or is it just hype? - A systematic literature review of the clinical consequences of switching from originator biologics to biosimilars. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17(8):915–926.

- Kristensen LE, Alten R, Puig L, et al. Non-pharmacological effects in switching medication: the nocebo effect in switching from originator to biosimilar agent. BioDrugs. 2018;32(5):397–404.

- Hu Y, Chen Z, Gong Y, et al. A review of switching biologic agents in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38(3):191–199.

- Luttropp K, Dalen J, Svedbom A, et al. Real-world patient experience of switching biologic treatment in inflammatory arthritis and ulcerative colitis - a systematic literature review. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020;14:309–320.

- Boktor M, Motlis A, Aravantagi A, et al. Substitution with alternative anti-TNFalpha therapy (SAVANT)-Outcomes of a Crohn’s disease cohort undergoing substitution therapy with certolizumab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(6):1353–1361.

- Gibofsky A, Skup M, Mittal M, et al. Effects of non-medical switching on outcomes among patients prescribed tumor necrosis factor inhibitors. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(11):1945–1953.

- Laas K, Peltomaa R, Kautiainen H, et al. Clinical impact of switching from infliximab to etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(7):927–932.

- Motlis A, Boktor M, Jordan P, et al. Two year follow-up of Crohn’s patients substituted to certolizumab anti-TNFa therapy: SAVANT 2. Pathophysiology. 2017;24(4):291–295.

- Wolf D, Skup M, Yang H, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with switching or discontinuation from anti-TNF inhibitors for nonmedical reasons. Clin Ther. 2017;39(4):849–62 e6.

- Liu Y, Skup M, Lin J, et al. Impact of non-medical switching on healthcare costs: a claims database analysis. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A252.

- Hoentjen F, Haarhuis BJ, Drenth JP, et al. Elective switching from infliximab to adalimumab in stable Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(4):761–766.

- Hutchinson D, Tier J, Soper S, et al., editors. Rheumatoid arthritis–treatment: 136. The conversion of infliximab to adalimumab in stable RA patients. Rheumatology. 2005 (April); Suppl. 1; i72. https://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/article/44/suppl_1/i64/1788688.

- Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Ballet V, et al. Switch to adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease controlled by maintenance infliximab: prospective randomised SWITCH trial. Gut. 2012;61(2):229–234.

- Viazis N, Pontas C, Gazouli M, et al. Efficacy of switching from infliximab to golimumab in ulcerative colitis patients on deep remission. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2019;13(Supplement 1):S449.

- Walsh CA, Minnock P, Slattery C, et al. Quality of life and economic impact of switching from established infliximab therapy to adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(7):1148–1152.

- Virkki LM, Valleala H, Takakubo Y, et al. Outcomes of switching anti-TNF drugs in rheumatoid arthritis–a study based on observational data from the finnish register of biological treatment (ROB-FIN). Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(11):1447–1454.

- Wei W, Knapp K, Wang L, et al. Treatment persistence and clinical outcomes of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor cycling or switching to a new mechanism of action therapy: real-world observational study of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the USA with prior tumor necrosis factor inhibitor therapy. Adv Ther. 2017;34(8):1936–1952.

- Vanderpoel J, Tkacz J, Brady BL, et al. Health care resource utilization and costs associated with switching biologics in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther. 2019;41(6):1080–9 e5.

- Dalen J, Luttropp K, Svedbom A, et al. Healthcare-related costs associated with switching subcutaneous tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor in the treatment of inflammatory arthritis: a retrospective study. Adv Ther. 2020;37(9):3746–3760.