ABSTRACT

Objectives

In this paper, we outline and compare pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies for in-patent prescription medicines in three Maghreb countries, Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, and explore possible improvements in their pricing and reimbursement systems.

Methods

The evidence informing this study comes from both an extensive literature review and a primary data collection from experts in the three studied countries.

Key findings

Twenty-six local experts where interviewed Intervieweesincluded ministry officials, representatives of national regulatory authorities, health insurance organizations, pharmaceutical procurement departments and agencies, academics, private pharmaceutical-sector actors, and associations. Results show that External Reference Pricing (ERP) is the dominant pricing method for in-patent medicines in the studied countries. Value-based pricing through Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is a new concept, recently used in Tunisia to help the reimbursement decision of some in-patent medicines but not yet used in the pricing of innovative medicines in the studied countries. Reimbursement decision is mainly based on negotiations set on Internal Reference Pricing (IRP).

Conclusion

Whereas each country has its specific regulations, there are many similarities in the pricing and reimbursement policies of in-patent medicines in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The ERP was found to be the dominant method to inform pricing and reimbursement decisions of in-patent medicines. Countries in the region can focus on the development of explicit value assessment systems and minimize their dependence on ERP over the longer-term. In this context, HTA will rely on local assessment of the evidence.

Introduction

Access to health services and pharmaceuticals is a fundamental human right [Citation1]; some countries incorporate it in their national constitution. Countries currently working towards universal health coverage and where a large part of pharmaceutical spending is still out of pocket are facing many challenges to achieving equitable access to affordable, safe, efficacious, and quality medicines. In this context, pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies have a substantial impact on controlling pharmaceutical costs of in-patent medicines – particularly innovative and expensive ones that also carry a significant financial burden for overall health expenditure.

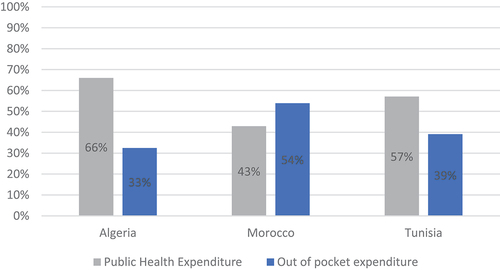

Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia are North African countries (also called Maghreb countries) with specific economic status and fragmented health-care systems. These countries are classified according to the World Bank income categories as Lower-Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) [Citation2]. The health-care environment in the region is subject to considerable epidemiological change (rising prevalence of non-communicable disease) [Citation3] as well as economic and financial pressure (rising health-care costs and coverage challenges). Total health expenditure ranges between 5% and 7% of GDP in the three Maghreb countries (438 to 974 current PPP USD per Capita) [Citation4]. The total health expenditure comprises the greatest proportion of GDP in Tunisia (7%) and the lowest proportion of GDP in Morocco (5%). However, government health expenditure represents the greatest proportion of GDP: 4% in Algeria, 4% in Tunisia, and only 2.5% in Morocco. Understandably, there is a significant difference between total and public (government) spending in health mostly covered through out-of-pocket (OOP) spending which is notable in the Maghreb countries. It ranges from 32,5% in Algeria to 54% of the total health expenditure in Morocco in 2017 ( ) [Citation5].

Figure 1. Proportion of public health expenditure and OOP in total healthcare expenditure by country.

Table 1. Healthcare expenditure (HE) in the Maghreb region [Citation5].

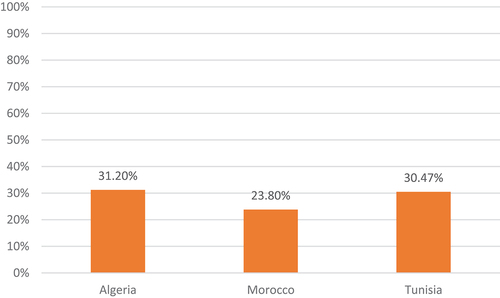

As in other low- and middle-income countries, medicines account for a large share of the health expenditures in the studied countries [Citation5]. Pharmaceutical spending ranges between 24% and 31% of the total health expenditure in the studied countries () [Citation5–8]. The patented pharmaceutical spending ranges from 41% to 52% of total pharmaceutical spending () [Citation5–8].

Table 2. Pharmaceutical expenditure and relation to health expenditure (2016 for Algeria and Morocco, 2014 for Tunisia [Citation5–8].

In the challenging context, of increasing demand, raising innovation of the pharmaceutical industry associated with growing medicine prices, and the limited resource allocations for health budgets, there is a need for a better understanding of how pharmaceutical markets are organized and financed in the Maghreb countries.

Pricing and reimbursement of pharmaceuticals has always had an important impact on health policy objectives, patients, wholesalers, pharmacists, doctors, health insurers, the pharmaceutical industry, and medicines availability. Papers describing pharmaceutical price setting or negotiating procedures and reimbursement systems that are implemented in the Maghreb region are very limited.

This study is the first one that describes and compares implemented regulations and procedures for pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement of in-patent medicines in three Maghreb countries: Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. A better understanding of the pharmaceutical landscape will help to foster pharmaceutical policies aiming to achieve universal and equitable access to essential medicines.

Methods

This study was conducted to map available evidence on pricing and reimbursement policies of in-patent pharmaceuticals in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia. The evidence informing this study comes from both (a) a literature review (LR), and (b) primary data collection from experts in the three studied countries.

The LR was based on an extensive review of peer-reviewed and grey literature, reports, analyses, national guidelines of health authorities web pages, related articles, reports, laws, and directives, with the objective to retrieve information relating to pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies and trends in the study countries.

To complete our literature review and validate our findings, a survey was conducted among pharmaceutical experts and stakeholders including government officials, representatives from regulatory authorities, insurance organizations, hospital pharmacy departments, procurement agencies, and private pharmaceutical-sector actors and associations. Interviews were conducted through face-to-face questionnaires (physically or via virtual platforms). The Stakeholder’s interview list is shown in Appendix 1.

In order to address the study objectives, a questionnaire was developed according to the LR outcome and was used during the interviews (Appendix 2). The questionnaire comprised three sections: a) Healthcare system and sources of financing; b) Pricing Policies and Price Setting for in-patent pharmaceuticals; c) Reimbursement and Coverage Decisions for in-patent pharmaceuticals. The identified outcomes of each section are detailed in .

Table 3. Key endpoints of the questionnaire.

The interviews were completed between March 2021 and July 2022. The responses were then evaluated and summarized to highlight key concepts and trends in each country.

Based on the results of the LR and the primary data collection, an analysis was undertaken to consolidate the information by mapping, describing, and reviewing the currently applied pricing and reimbursement mechanisms in the study target countries and providing practical suggestions on how to improve pricing and reimbursement policies.

Results

Official documents, legal texts, and published pricing guidelines were reviewed in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia in the national language [Citation9–23]. Twenty-six local experts were interviewed. Interviewees included ministry officials, representatives of national regulatory authorities, health insurance organizations, pharmaceutical procure-ment departments and agencies, academics, private pharmaceutical-sector actors, and associations.

Pricing policies for in-patent pharmaceuticals

In Algeria, the authority responsible for setting pharmaceutical prices is the National Agency of Pharmaceutical Products (ANPP) under the supervision of the Ministry of Pharmaceutical Industry (MPI). An inter-ministerial committee is responsible for price setting: The Intersectoral Economic Committee of Drugs (CEPS). It was created at the ANPP by decree [Citation9,Citation10].

This committee includes representatives from the Ministry of Trade, the Ministry of Public Health, the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Affairs, and the National Health Insurance ([Citation9] [Citation24] primary data collection Algeria 2022). Price negotiation and approval occur before the grant of the Marketing Authorization Application (MAA) (primary data collection Algeria 2022).

The main policy used for in-patent pharmaceutical pricing is External Reference Pricing (ERP). The list of benchmark countries is determined by the decision of the Minister in charge of the Pharmaceutical Industry and it includes Belgium, France, Greece, Morocco, Spain, Tunisia, Turkey, the UK, and the Country of origin (COO). The price is calculated based on the lowest Ex-factory price (5, primary data collection Algeria 2022).

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) has been recently used through medico-economic assessments. According to the Ministerial decree of 26 December 2020, the Economic Committee may now require pharmacoeconomic studies to inform pricing decisions. The Ministry of Pharmaceutical Industry is responsible for medico-economic assessment, but this activity is still under development. The nature of the studies that may be required is primarily Budget Impact Analysis but cost-effectiveness studies can also be required [Citation5] (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

The Ministry of Health is responsible for hospital medicines management along with the procurement body for the public sector, the Hospitals’ Central Pharmacy (PCH) (Primary data collection Algeria 2022). Access programs for low-income patients are rarely deployed in Algeria because of cultural aspects (Algerian culture rejects donations or the help of companies). Nevertheless, the PCH may request free units on each purchase as a discount [Citation5] primary data collection Algeria 2022).

In the private sector, distributors and pharmacists' margins are controlled by decree () [Citation11].

Table 4. Comparison of mark-up schemes in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia [Citation11,Citation12,Citation17,Citation18].

In Morocco, the pricing regulations and objectives are clearly stated in the country’s legislation [Citation12]. The authority responsible for setting pharmaceuticals prices is the Ministry of Health through an inter-ministerial committee where many representatives are involved, mainly the Directorate of Medicine and Pharmacy (DMP) and the National Health Insurance/Ministry of Health (ANAM). Although price setting is not mandatory to obtain marketing authorization, the marketing of medicine remains conditioned by the publication of its price in the Official Journal (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

The main policy used for pricing originator medicine newly introduced on the market is ERP. Seven countries are considered in the basket: Belgium, France, Portugal, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Turkey, and the country of origin if different. The considered price is the average price of the basket for existing products and the lowest price for newly launched pharmaceuticals converted into dirhams according to the national regulations [Citation5] (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

Pharmaceuticals’ prices are also controlled through regulated mark-ups in the supply distribution chain [Citation12]. For locally manufactured drugs, the profit margins to be applied to the wholesale pharmaceutical establishment and to the dispensing pharmacist are defined in according to the MPET ranges. For imported medicines, an additional 10% importer margin is also applied [Citation12].

There is a multi-source procurement in Morocco: public and private sources. This can lead to different prices, especially between the public and the private sector (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

It is worth noticing that in-patent pharmaceuticals’ prices are negotiated independently of their reimbursement (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

In Tunisia, the prices of medicines (in-patent and generics) are negotiated by the Marketing Authorization Committee called ‘Technical Committee of Pharmaceutical Specialties’, which sits in the National Regulatory Authority (The Directorate of Pharmacy and Medicines or DPM), MOH. Indeed, Tunisian regulations state that Marketing authorization should be granted only to medicines that are presumed to improve the medical service rendered, to bring savings on the cost of health, in particular, compared to marketed products with the same or similar therapeutic aim [Citation13].

Pricing of in-patent pharmaceuticals in Tunisia combines ERP and Internal Reference Pricing (IRP) to derive the price of similar products in the same therapeutic class. External reference pricing is applied to all imported medicines (originator brands and generics) seeking approval for regulatory registration and marketing in Tunisia. When submitting Marketing Authorization (MA) application, manufacturers must submit available prices of the medicine at an ex-wholesaler level in six countries: Algeria, France, Germany, Italy, Morocco, and Spain [Citation14].

For originator brands and thereafter for most of the newly launched in-patent pharmaceuticals, price negotiation with the manufacturers is made by the Ministry of Health’s Technical Committee of Pharmaceutical Specialties based on the:

Initial rule: at least 12.5% lower than the wholesaler price in the product country of origin

Prices of the product in the reference countries

Prices of existing therapeutic analogs in Tunisia (IRP)

Further health technology assessments by foreign HTA agencies or pharmacoeconomic studies: the price is determined by the assessment of the value informed by the evidence and HTA opinions and price data existing in the models including the cost-efficiency ratio.

For innovative medicines, an access program for indigent patients is systematically required. In this case, an agreed-on quantity is freely made available by the manufacturer to cover the needs of low-income patients who do not have health insurance coverage. Thus, specific contracts are signed by the pharmaceutical company and the Minister of Health (DPM and PCT). The access program is implemented once the medication is covered by national insurance (CNAM) (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

Once price negotiation is agreed on from both sides (Manufacturer and Technical Committee of Pharmaceutical Specialties), the marketing authorization is granted with a proposed price (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

In Tunisia, the public and private sectors have distinct procurement and pricing mechanisms. In the public sector, medicine procurement is ensured and centralized by the PCT, the procurement agency under the supervision of the Ministry of Health. It procures medicines for public hospitals mostly through procurement processes including tendering when appropriate/possible. The PCT is also playing a major role in private-sector procurement as it is the sole authorized importer of medicines [Citation15]. Therefore, for all imported medicines (public and private sectors) and for hospital medicines, the Medicines Purchasing Commission (CAM) of the PCT fixes the purchase price with suppliers. Locally manufactured products intended for the private sector can be distributed directly through wholesalers without the intervention of the PCT (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

Retail Prices are then officially approved by the Ministry of Trade as the pricing regulation of medicines is stated in the law n° 36–2015 of 15 September 2015 on the reorganization of competition and prices which excludes essential products and services from the free pricing regime. Medicines are included in the list of products and services subject to the regime of price approval at all stages by the Ministry of Trade ([Citation16] primary data collection Tunisia 2022). Price setting takes into consideration the agreed price by the MOH, currency exchange level, and mark-ups applied along the supply chain. While the wholesaler’s and pharmacists’ margins are set by a joint order of the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Trade [Citation17,Citation18] (), the PCT (importer) margin is fixed by internal procedures approved by the PCT Board.

Eventually, wholesalers, pharmacists, and patients’ purchase prices are published by the PCT in the form of public circulars. The purchasing price by the PCT is confidential, while public prices are published in PCT website. PCT Commercial medicines margin is 10.5% in the private sector fixed by internal procedures. It is worth noticing that the price approved by the Ministry of Trade does not apply to the hospital sector where prices are set through tendering by the PCT (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

summarizes the criteria for price setting of in-patent pharmaceuticals in the studied countries.

Table 5. Criteria for price setting of in-patent pharmaceuticals in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia [Citation5,Citation9–19,Citation24–26] (Primary data collection 2022 Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia).

Price revision

In Algeria, in-patent pharmaceutical prices are revised every 5 years at the same time as MA renewal [Citation19], but some events can trigger in-patent medicines’ price revision:

When the price changes in the country of origin or in key basket countries.

When the manufacturer asks for price revision. This can happen even 1 year after price homologation and MA. Price can be reviewed downward or upward.

When the price changes worldwide (downward) independently of ERP basket countries (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

In Morocco, medicine price revision is performed by the economic service of the national regulatory body (DMP, MOH). Price revisions take place during the MA renewal, every 5 years. Some events can trigger in-patent pharmaceuticals’ price revision: (i) when price changes in key basket countries occur, (ii) when an originator loses its market exclusivity, (iii) When the manufacturer asks for price revision to have a more competitive price, (iv) there is a change in the pharmaceutical formula or packaging [Citation5,Citation12] (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

Following a global benchmark of medicine prices in Morocco with other countries, important price reductions were applied by the Ministry of Health to 320 and 1258 drugs, respectively, in 2013 and 2014 [Citation12,Citation25].

In Tunisia, the revision of retail prices is made by the Ministry of Trade (Department of Economic Studies and Price Competition) after consultation with the MOH (DPM). Revisions are only applied for locally manufactured pharmaceuticals upon request and generally every 5 years [Citation15].

For the imported medicines, downward revision of the purchase prices may be applied by the Tunisian Central Pharmacy (PCT) every 5 years but not systematically. In this context, the downward price revision process and timelines are not described by law, and there is no systematic reduction of the originator brand price upon the registration of the first generic in the Tunisian pharmaceutical market (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

On the other hand, purchase prices by the PCT regularly increase without revision of the retail price by the Ministry of Trade. This practice is due to the compensation process by the PCT. This practice is applied to compensate for price increases of imported medicines resulting in exchange rate fluctuations. The exchange rate applied by the central pharmacy corresponds to the real exchange rate of the pricing operation (average day rate of the central bank BCT on the day of the first receipt of the product). Consequently, PCT will lose its profit margin and even sell below the purchase price at a loss. This loss is compensated by the Government and applies only to imported drugs and aims to maintain stable retail prices and therefore maintain the affordability of essential medicines to Tunisian patients (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

As the amount of PCT loss gets greater every year, it reached € 55 million (TND 210 million) in 2018 [Citation26], several exceptions were applied to retail price revision for imported medicines (when purchasing costs increase or when the Tunisian currency drops) in the following cases:

Medicines classified as comfort (non-essential)

Medicines classified as intermediate with a price under 5 Tunisian dinars

Medicines having non-compensated equivalent. A list of 50 to 60 imported products was subject to price revision (decompensation) (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

Some events can trigger pharmaceuticals’ purchasing price revision (after price approval by the Ministry of Trade), when price changes in the country of origin, suppliers are asked for a price reduction, namely for compensated products (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

For hospital products purchased by mutual agreement, the purchasing prices can be revised by the PCT (CAM) upon request. Price cuts and increases will be applied to hospitals through annual revisions of the PCT prices (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

To mitigate exchange rate fluctuations, price adjustments are implemented in Morocco (prices of imported in-patent pharmaceuticals and generics are revised when the exchange rate varies by more than 10%). Whereas in Algeria, there are no price adjustments to take into account exchange rate fluctuations [Citation5] (primary data collection Algeria, Morocco 2022). In Tunisia, for the imported medicines, exchange rate fluctuations are charged by the PCT and not transferred to the retail prices. This practice called the ‘compensation’ rises the amount of its loss (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

Reimbursement policies

In Algeria, access to the retail market is under the social security (ministry of labor) which is in charge of the reimbursement process for outpatient care. Algeria is a predominantly reimbursed market. The public sector provides free treatments (formulary listing) to all citizens, while 85% of the population is covered by social security for outpatient care. Access to treatment is mainly influenced by the reimbursement and enlisting. CNAS (‘Caisse Nationale des assurances sociales des Travailleurs Salariés’) covers working employees (social affiliates) through El Chifa card, CASNOS (‘Caisse Nationale des Assurances Sociales des Non Salariés’) covers self-employed persons, CNR (Caisse Nationale des Retraités) covers retired citizens, CNAC (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Chomage) covers unemployed persons (Primary data collection Algeria 2022) [Citation27]. El Chifa card covers about 80% of the medicines price [Citation27,Citation28].

The bodies that decide for the reimbursement of in-patent pharmaceuticals in Algeria are the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Social Affairs through the reimbursement committee. The main actors involved in reimbursement decisions are the National Insurance Scheme, the National Regulatory Authority (ANPP), and health-care providers or the DGSS (hospital or special services directorate). Key opinion leaders and health-care professionals (experts) have a consultative role (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

Reimbursement decisions of in-patent molecules are based on prices resulting from ERP (set by the Pricing Committee), local comparators, unmet needs, and reimbursement status in reference countries. Negotiations can lead to three outcomes: (i) ERP-derived price is retained as a reimbursement price with or without prescribing conditions; (ii) a lower price is set for reimbursement based on budget impact assessments or comparative clinical benefit assessment, or (iii) a reference price for reimbursement is set based on the cheapest alternative product already on the market (IRP molecular or therapeutic basis) [Citation5,Citation29]. The reference prices list is published in the form of a positive list [Citation30]. The reference price is revised when a new competitor (generic) is launched in the market (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

There are two possible percentages of reimbursement: 100% for NCDs medicines and 80% for other medicines (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

Concerning the off-label use of drugs, if a hospital obtains specific authorizations for temporary use of certain drugs, it can place a dedicated procurement order with the PCH to acquire the medication (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

In Morocco, the compulsory health insurance system is fragmented with the existence of two main systems: the National Health Insurance (ANAM) and the funding system led by the government through fiscal resources (Primary data collection Morocco 2022) [Citation31,Citation32]. A high number of Moroccan citizens could benefit from a mandatory national health insurance plan known as the AMO (Assurance Maladie Obligatoire). The CNOPS or National Fund for Social Welfare Organizations is for the public sector, and the CNSS or National Social Security Fund is for the private sector. Indigent patients have access to medical assistance scheme set by the Ministry of Health as an assistance to vulnerable people (RAMED). Private health insurance also exists but it does not have a considerable contribution to healthcare funding. It is to be noticed that a coverage for the Royal Armed Forces exists and it has its specific schemes (Primary data collection Morocco 2022) [Citation32,Citation33].

Reimbursement decisions of in-patent pharmaceuticals are taken by the MOH through two committees: the Transparence Committee (CT) and The Commission for Economic and Financial Evaluation of Health Products (CEFPS), both of which sit in the ANAM.

The Transparency committee provides an opinion on the Medical Service Rendered (SMR) and/or the Improvement of the Medical Service Rendered (ASMR) of a medicinal product that has already obtained the MA. The CT involves Key opinion leaders (KOLs)/health-care professionals (experts) and scientific societies in its scientific assessment. Industry representatives can participate as observers (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

The CEFPS analyzes the economic and financial impacts of drugs with a favorable SMR by the CT and engages in one-to-one negotiations with the manufacturers to (i) make decisions regarding the inclusion or removal of medicines from the list of reimbursable drugs; (ii) set the reimbursement percentage and price (price revision if the reimbursement is proposed later by the company) (Primary data collection Morocco 2021) [Citation34,Citation35]. ERP prices are usually used as a starting point for negotiations to determine reimbursement of innovative drugs. Negotiations are usually based on IRP (molecular or therapeutic basis).

There are two possible percentages of reimbursement: 100% for NCDs medicines and 80% for other medicines (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

The reference price for reimbursement is set based on the highest price of registered medicines (Primary data collection Morocco 2022). The reference prices list is published in the form of a positive list (GMR or Guide des Médicaments Remboursables) [Citation36]. The reference price is revised when a new competitor (generic) is launched in the market (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

In Morocco, off-label use of medicines without marketing authorization or prescriptions outside approved indications involves a process of derogation granted by the ANAM. These derogations are based on claims submitted by insured individuals and require a comprehensive medical dossier. A group of experts evaluates these claims and provides their opinions (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

In Tunisia, the funding system is fragmented with the existence of two main tiered social protection systems: the National Health Insurance (CNAM or Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie) and the Free Medical Assistance (AMG) led by the government. Both are based on the principles of insurance and assistance. 70% of the Tunisian citizens are covered by CNAM [Citation37] that covers both affiliates from CNRPS (Caisse Nationale de Retraite et de Prévoyance Sociale) (public sector employees) and CNSS (Caisse Nationale de Securité Sociale) (private sector employees). Indigent patients have the right to the public facilities through AMG (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022). Two types of AMG exist for indigent patients: type 1 the patient is exempt from consultation and medication fees, while type 2 pays a token sum according to the criteria fixed by the Ministry of Social Affairs. The social security contribution is essentially oriented to the public sector subsidiaries despite an increasing contribution to private sector facilities. The reform of the social security with the creation of the CNAM aimed to transform the private sector [Citation38–40].

The National Health Insurance (CNAM) is under the supervision of the Ministry of Social Affairs. The reimbursement committee is the decision-making body for drug reimbursement and sits at the general directorate of social security (Ministry of Social Affairs). The CNAM and the Ministry of Health (DPM) are represented in this committee (Primary data collection, Tunisia 2022).

Reimbursement decisions of originator medicines are based on prices set at the time of the MA grant that serves as the starting negotiation price. Discount rates are usually requested to determine the reimbursement price. Negotiations can be based on IRP (molecular or therapeutic basis) (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

In Tunisia, native HTA has been implemented by the National Instance of Evaluation and Accreditation in Health (INEAS), a public institution under the supervision of the Ministry of Health created in 2012 [Citation41]. Since the HTA activity started in 2015, some studies have been carried out to help the reimbursement decision-making [Citation20,Citation21]. The INEAS economic guidelines on ‘Methodological choices for pharmaco-economic studies’ and ‘Methodological choices for the analysis of the budget impact’ have been recently published [Citation22,Citation23].

Currently, INEAS is informing the payer’s decision-making for the reimbursement of innovative medicines when requested by the CNAM. The strategic vision of INEAS is currently to focus on high-priced drugs (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

Regarding the percentage of reimbursement; for NCDs medicines, there are 24 fully covered Diseases for which Medicines are reimbursed at 100% of their reference price; and for other outpatient medicines provided in the private health-care sector, different reimbursement rates are applied depending on the medicine classification into Vital medicines (100%), Essential medicines (85%), Intermediate medicines (40%), or Comfort medicines (0%). The classification of medicines is decided by the national regulatory body (DPM) at the time the MA is granted (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022). Reimbursement is made based on the reference price calculated according to the cheapest generic existing in the market, the lowest retail price of one tablet or unit [Citation38] (primary data collection Tunisia 2022). It is worth noticing that similar dosage forms are considered generics. The reference prices list is published in the form of a positive list [Citation42]. The reference price is revised annually (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

In Tunisia, the process for the off-label use of drugs (also called ‘commande ferme’) begins with an appeal commission for reimbursement with the CNAM. If the initial decision is unfavorable, patients have the option to resort to the courts, and in some cases, they may subsequently obtain a favorable decision from the CNAM. Following this, patients are required to submit a request to the DPM for a specific marketing authorization. It is important to note that once the DPM receives the request, they are obligated to accept it. Then, the process is initiated allowing the patient to obtain the off-label medication (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

summarizes the reimbursement system in the studied countries.

Table 6. Reimbursement system in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia [Citation5,Citation20–23,Citation29,Citation30,Citation34–36,Citation38,Citation42] (primary data collection Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia 2022).

Discussion

By reviewing official documents and interviewing stakeholders, our study provides a clearer understanding of the pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement policies in Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia (, and ).

When pricing systems are reviewed in our study, it can be seen that even though there are similarities between the three countries, each studied country has its own particular scheme. Interestingly, prices are controlled for all medicines in the studied countries, though different Ministries are responsible for medicine prices approval (Ministry of Pharmaceutical Industry in Algeria, Ministry of Health in Morocco and Ministry of Trade in Tunisia). Regarding the relationship between price negotiation and marketing authorization, while the pricing intervenes after the registration process in Morocco, price negotiation is still occurring before the MA is granted in Algeria and Tunisia.

As appears to be the case in the majority of the Middle East and North African (MENA) countries, currently ERP is the most used method of pricing across the Maghreb region for in-patent medicines, while IRP is mainly used for generic and biosimilar pricing [Citation5]. However, additional criteria may apply for in-patent medicines, such as the prices of pharmaceuticals in the same therapeutic category (internal reference pricing – IRP). So finally, ERP is indicative and not the only policy used for setting prices of in-patent pharmaceuticals in Maghreb countries.

The reference basket countries to which the prices are benchmarked in the Maghreb region are relatively small comparatively to large baskets in some countries of the MENA region such as Saudi Arabia and Egypt (30 and 36, respectively) [Citation5]. In the three studied countries, the reference list includes 4 to 5 European countries and 1 to 2 countries from Maghreb or MENA Region. In Algeria and Tunisia, the reference price is calculated based on the lowest price in the basket with the exception of Morocco, which uses the average price of the basket for existing products and the lowest price for newly launched pharmaceuticals. Regarding the comparator price, the ex-factory price is used in Morocco and Algeria, whereas the wholesaler price excluding VAT is applied in Tunisia.

Profit margins are fixed with different schemes along the pharmaceutical supply chain in the studied countries (). In the three countries, the different mark-up schemes are available to the public in Decrees. A regressive mark‐up structure, in which the mark‐up rate decreases as the price increases, is applied at different levels in the three countries. However, with the exception of Morocco, there is no cap on percentage margins for the high price medicines.

The range of the cumulative profit margins for wholesalers and retailers varies from 39.6% to 50.9% in Tunisia, from less than 24% to 68% in Morocco and from 30% to 70% in Algeria. The maximum cumulative mark-up is relatively high when compared to other MENA region countries such as Lebanon (32–40%), Qatar (40% for all medicines), and Jordan (39% for all pharmaceuticals) [Citation5,Citation43]. The minimum cumulative mark-up applied for the most expensive medicines is also relatively high in Algeria (30%) and Tunisia (38.5%).

In Morocco, from public stakeholders’ perspective, Moroccan current pricing policy leads to high prices when compared to other countries for in-patent and innovative medicines in private sector and unavailability of drugs in public sector [Citation44] (Primary data collection Morocco 2022).

In Algeria, access to innovative medicines remains very difficult because of willingness to pay and cost containment issues. Innovative medicines are perceived as very expensive and the only way to improve access to medicines is enlisting by the central pharmacy of hospitals (Primary data collection Algeria 2022).

In Tunisia, from public stakeholders’ perspective, current pricing policies can lead to high prices for in-patent and innovative medicines [Citation20,Citation45] (primary data collection Tunisia 2022). From the company's perspective, continuous discounts on in-patent medicines price from the stage of price setting to the reimbursement step lead to very low prices for a great number of products. This situation discourages the launch of innovative medicines in the Tunisian market (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

In the three countries, access to innovative treatment is mainly influenced by the reimbursement. While the three countries have some similarities with respect to the reimbursement decision-making process, there are significant differences regarding the negotiations’ methods.

In Algeria and Morocco, like several countries in the MENA region, ERP prices set in the pricing process become the starting point for reimbursement price negotiations and often, ERP prices become reimbursement prices [Citation5]. Whereas in Tunisia, considerable price reduction may be required for reimbursement (Primary data collection Tunisia 2022).

With regard to the use of HTA to inform pricing and coverage decisions, the evidence generally indicates an increased interest for pharmacoeconomic evaluations in the studied countries. Tunisia has already invested in an HTA agency to address the challenges of value assessment, Algeria started by requiring budget impact analysis and Morocco implemented a committee of transparence to inform reimbursement decisions. However, further significant investments in the development of human capabilities and in data generation processes are required to ensure formal value assessment systems are in operation in a systematic manner in the Maghreb countries.

In regard to our findings, some suggestions could be considered for possible improvements to innovative medicines access:

Review the entire pricing process to reduce response times and allow rapid access to innovative treatments by promoting the separation of MA and pricing.

Countries, especially low-income ones, could not rely only on ERP method for setting prices because reference price may be used to determine a maximum price, while the actual price that the country health system pays will be based on confidential discounts or rebates.

Including HTA when negotiating prices and reimbursement will allow stakeholders to reduce the cost and the out-of-pocket expenditure of patients.

Conclusion

Our study presents a number of findings relative to pricing and reimbursement policies for in-patent medicines in Tunisia, Morocco, and Algeria. Whereas each country has its specific regulations, pricing, and reimbursement policies of medicines, there are many similarities.

The ERP was found to be the dominant method to inform pricing and reimbursement decisions of in-patent pharmaceuticals, which may not be reflective of net prices.

As Healthcare expenditures will continue to rise all over the world because of the introduction of innovative and expensive therapies, there is a real need to have pricing and reimbursement policies for medicines that are based on more-formalized arrangements around value assessment that will rely on local assessment of the evidence.

Further investigations on how to improve operational procedures for transition from price-focused to value-focused policies in the studied countries are required. Moreover, a reflection on how to review the processes of the studied countries to implement innovative contracting and to use risk sharing to mitigate the high cost of new medicines is needed to ensure equity in access to new health technologies in the Maghreb region.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the experts and contributors who offered their insights and expertise on the topics of pricing and reimbursement in the Maghreb region through survey responses and virtual interviews. Contributors are part of a research group called “Maghreb Research Group.” This group includes experts and stakeholders from the public health sector (government officials, representatives from regulatory authorities, insurance organizations, pharmacy departments, procurement agencies) and from the private health sector (actors and associations). Contributors’ names and positions are illustrated in the appendix 1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Human rights: key facts. World Health Organization. 10 December 2022. [cited 2022 December 18]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-rights-and-health#:~:text=The%20WHO%20Constitution%20(1946)%20envisages,acceptable%2C%20and%20affordable%20health%20care.

- World Bank Country and Lending Groups. Lower middle income economies. [cited 2022 March 1]; Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

- World Health Organization. Estimated DALYs (‘000) by cause, sex and WHO member state (1) 2016. [cited 2020 September 10]; Available from: www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GHE2016_DALYs-2016-country.xls?ua=1.

- World Bank. GDP per capita, PPP (constant 2017 international $) 2017. World Bank DataBank, World Development Indicators. [cited 2020 January 15]; Available from: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/source/world-development-indicators.

- Kanavos P, Tzouma V, Fontrier A-M, et al. Pharmaceutical pricing and reimbursement in the Middle East and North Africa region. A mapping for the current landscape and options for the future 2018 November. [cited 2019 December 2]; Available from: https://www.lse.ac.uk/business/consulting/assets/documents/pharmaceutical-pricing-and-reimbursement-in-the-middle-east-and-north-africa-region.pdf.

- Abdelaziz AB, Amor SH, Ayadi I, et al. Financing health care in Tunisia. Current state of health care expenditure and socialization prospects, on the road to Universal health coverage. La Tunisie Médicale. 2018;96(10/11):789–17.

- IQVIA June 2019 report on Middle East and Africa Pharmaceutical market insights thirteen edition. Analytical Timeframe: MAT Dec 2018. [cited 2020 March 11]; Available from: www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/mea/edition-13-mea-pharmaceutical-market-quarterly-report.pdf.

- World bank blog. [cited 2021 February 12]; Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/fr/arabvoices/dialogue-tunisia-pharmaceutical.

- Executive decree n° 20-326 of 6 Rabie Ethani 1442 corresponding to November 22, 2020 concerning the missions, composition, organization and functioning of the intersectoral economic committee of medicines. [cited 2021 February 12]; Available from: https://www.miph.gov.dz/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/07-De%CC%81cret-exe%CC%81cutif-n%C2%B0-20-326.pdf.

- Ministerial Order of December 26, 2020 on the appointment of the chairman and members of the intersectoral economic committee of drugs. [cited 2021 October 25]; Available from: https://www.miph.gov.dz/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/04-Arrete-du-26-decembre-2020-portant-designation-du-president-et-des-membres-du-comite-economique-intersectoriel-des-medicaments.pdf.

- Executive Decree No. 98-44 of February 1, 1998 on the ceiling margins applicable to the production, packaging and distribution of medicines for human medicine. [cited 2021 March 10]; Available from: https://www.joradp.dz/FTP/jo-francais/1998/F1998005.PDF.

- Decree n° 2-13-852 of 18th December 2013 sante.Gov.ma 2013. [cited 2023 February 25]; Available from: https://www.sante.gov.ma/Reglementation/TARIFICATION/2-13-852.pdf.

- Law No. 85-91 of 11/22/1985: regulating the manufacture and registration of drugs intended for human medicine as amended by Law No. 99-73 of July 26 1999. [cited 2021 June 12]; Available from: http://www.dpm.tn/images/pdf/texte/loi-85-91-consolide.pdf.

- Registration guide of the Directorate of Pharmacy and Medicines (DPM) of 2016. [cited 2019 December 11]; Available from: http://www.dpm.tn/images/pdf/guide_dpm.pdf.

- World Health OrganizationCountry pharmaceutical pricing policies: a handbook of case studies (March 2021) 2021cited 2022 November 5]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/341188.

- Decree N° 95-1142 of June 28, 1995 relating to products and services excluded from the regime of freedom of price and terms of their supervision. JORT. [cited 2022 February 2]; Available from: http://www.dpm.tn/images/pdf/texte/decret-95-1142.pdf.

- Order of the Minister of Health and the Minister of Commerce of March 27, 2020, amending the order of May 21, 1982, on the prices of pharmaceutical products. [cited 2022 February 2]; Available from: https://www.jurisitetunisie.com/download_jort.php?f=A2020_0581-F2020_027.pdf

- WHO. Maîtrise des coûts des médicaments importés/Etude de cas: Tunisie 2003. [cited 2021 February 4]; Available from: http://www.dpm.tn/images/pdf/maitrise_des_couts_tunisie.pdf.

- Order of 11 Joumada El Oula 1442 corresponding to December 26, 2020 setting the procedure for setting the prices of drugs by the intersectoral economic committee for drugs. [cited 2021 October 25]; Available from: https://www.miph.gov.dz/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/05-Arrete-du-26-decembre-2020-fixant-la-procedure-de-fixation-des-prix-des-medicaments-par-le-comite-economique-intersectoriel-des-medicaments.pdf.

- Avis d’Evaluation des technologies de Santé - INEAS. Le trastuzumab dans le traitement du cancer du sein HER2 positif au stade précoce et localement avancé 2018. [cited 2022 February 25]; Available from: https://www.ineas.tn/sites/default/files/trastuzumab-ineas.pdf.

- Avis d’Evaluation des technologies de Santé - INEAS. SKYRIZI® (Risankizumab) dans le traitement du psoriasis en plaques modéré à sévère chez l’adulte 2022. Tunis: INEAS. [cited 2023 February 25]; Available from: https://www.ineas.tn/sites/default/files/SKYRIZI%20ETS%20INEAS.pdf.

- Choix méthodologiques pour les Etudes Pharmaco-Economiques - INEAS. n.d. [cited 2023 February 25]; Available from: https://www.ineas.tn/sites/default/files/ineas.hta_.guide_etudes_pharmacoeconomiques.pdf.

- Choix méthodologiques pour L’ANALYSE de L’IMAPCT Budgétaire a L’INEAS. n.d. [cited 2023 February 25]; Available from: https://www.ineas.tn/sites/default/files/ineas.hta_.guide_analyses_impact_budgetaire.pdf.

- Algérie presse service. Installation du comité intersectoriel des médicaments et de la commission d’homologation des dispositifs médicaux. [cited 2021 April 11]; Available from: https://www.aps.dz/sante-science-technologie/115586-installation-du-comite-intersectoriel-des-medicaments-et-de-la-commission-d-homologation-des-dispositifs-medicaux.

- Au Maroc , les prix de 1 258 médicaments vont baisser de 30 à 60 n.d. [cited 2023 February 25]; Available from: https://www.lequotidiendumedecin.fr/actus-medicales/medicament/au-maroc-les-prix-de-1-258-medicaments-vont-baisser-de-30-60.

- La Presse. Le secteur du médicament en Tunisie: les failles d’un système. [cited 2020 January 14]; Available from: https://lapresse.tn/9930/le-secteur-du-medicament-en-tunisie-les-failles-dun-systeme/#:~:text=Le%20syst%C3%A8me%20de%20compensation%20des,financier%20pour%20l’y%20aider.

- Algeria. Healthcare and Life sciences Review Pharmaboardroom February 2019. [cited 2020 May 16]; Available from: https://pharmaboardroom.com/country-reports/algeria-pharma-report-2019/.

- Nasreddine A. The Algerian pharmaceutical market; specifics and Characteristics. Revue des Etudes et Recherches en Logistique et Développement (RERLED). 1st ed. Vol. 1, Algeria: RERLED; 2020.

- Order of 23 Dhou El Hidja 1439 corresponding to September 3, 2018 amending and supplementing the order of March 6, 2008 setting the reference rates used as a basis for the reimbursement of drugs and the terms of their implementation. [cited 2022 October 25]; Available from: https://www.joradp.dz/FTP/JO-FRANCAIS/2018/F2018071.pdf.

- Order of 6 Safar 1434 corresponding to December 19, 2012 supplementing the order of March 6, 2008 establishing the list of medicines reimbursable by social security. [cited 2022 October 25]; Available from: https://www.m-culture.gov.dz/images/pdf/textes/2013/F2013026.pdf.

- Mobilising the health revenues to finance the health system in Morocco OECD. 2020. [cited 2021 December 11]; Available from: https://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/mobilising-tax-revenues-to-finance-the-health-system-in-morocco.pdf.

- Comptes nationaux de la sante. Direction de la planification et des ressources financieres. Ministere de la sante. OMS 2018. [cited 2021 January 22]; Available from: https://www.sante.gov.ma/Publications/Etudes_enquete/Documents/2021/CNS-2018.pdf.

- WHO 2015: Morocco: Health Profile. Regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean, World Health Organization. 2015. [cited 2020 November]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/253774.

- Commission d’évaluation économique et financière des produits de santé, internal regulations. National Health Insurance Agency, Kingdom Of Morocco, Mars. 2014. [cited 2020 August 3]; Available from: https://anam.ma/anam/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Re-glement-Inte-rieur-CEEFPS.pdf.

- Transparency Commission. The National Health Insurance Agency. [cited 2020 August 3]; Available from: https://anam.ma/anam/commission-de-transparence/.

- Guide to reimbursable drugs ANAM. [cited 2021 March 3]; Available from: https://anam.ma/regulation/guide-medicaments/recherche-de-medicaments-par-nom/.

- UNICO studies series 4 consolidation and transparency: transforming tunisia’s health care for the poor. Washington DC: The World Bank, January 2013. Available from: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/242251468122347643/pdf/749970NWP0Box30Transparency0TUNISIA.pdf

- Khanfir M. How public policy could enable the knowledge economy: the case of healthcare sector in Tunisia. Tunisia Africa Business Council, January 2018. [cited 2021 January 12]; Available from: http://tabc.org.tn/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Public-policy-to-enable-KBE-in-Africa.-The-case-of-Healthcare-sector-in-Tunisia.pdf.

- WHO, 2006: Tunisia: Health System Profile. Regional health systems observatory, World Health Organization 2006. [cited 2020 September 5]; Available from: https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1017861/1228_1216908062_tunisia.pdf.

- WHO. Tunisia: medicine prices, availability, affordability and price components. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, World Health Organization. 2010. [cited 2020 August 15]; Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/116638.

- Decree No. 2012-1709 of September 6, 2012, creating the national health accreditation body and setting its powers, administrative, scientific and financial organization, as well as the terms of its operation. [cited 2021 June]; Available from: http://www.atds.org.tn/Decretseptembre2012.pdf.

- Social Insured Area. Cnam. n.d. [cited 2022 March 3]; Available from: https://www.cnam.nat.tn/espace_assure.jsp.

- Abdel Rida N, Izham Mohamed Ibrahim M, Babar ZUD. Pharmaceutical pricing policies in Qatar and Lebanon: narrative review and document analysis. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2019;10(3):277–287. doi: 10.1111/jphs.12304

- Tuck C, Maamri A, Chan AH, et al. Editorial: medicines pricing, access and safety in Morocco. Trop Med Int Health. 2019 March;24(3):260–263. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13191

- Fradi H, Ghozzi N, Miled S, et al. An analysis of the Tunisian medicines price policy. Utrecht WHO Winter Meeting 2019. [cited 2022 February 12]; Available from: http://www.pharmaceuticalpolicy.nl/assets/uploads/2016/10/Programme-Winter-Meeting-report-2019.pdf.

Appendix 2

Pricing and reimbursement questionnaire

Important to notice: vaccines are not considered in this questionnaire.

Section 1: Healthcare system and sources of financing

1. Which country are you completing this survey for?

2. In your country, do you have Universal Health Coverage?

Yes

No

Other, please specify:

If yes, what are the sources of funding and in which percentage?

- Government (freely)

- National Health Insurance

- Private Health Insurance

- Other, please specify

3. In the case of Universal Health coverage, is it a unique (common) or a fragmented system?

4. In case of fragmented system:

- How many principal insurances do you have?

- What percentage of people does each insurance cover?

5. How are pharmaceuticals covered in your country?

A. Full coverage

- Yes

- No

B. Partial coverage

- Yes

- No

C. Other, please specify

6. What are pharmaceuticals’ coverage conditions in your country?

Section 2: Pricing Policies and Price Setting for in-patent pharmaceuticals

7. Are the pricing regulations and objectives clearly stated in your country’s legislation?

- Yes

- No

If yes please provide the law reference

8. For which type of pharmaceuticals prices are fixed:

(Please tick all that apply)

Public sector

Private sector

Reimbursed medicines

None of the above list

9. In your country, are pharmaceuticals’ prices controlled through distributor and pharmacist margins?

- Yes

- No

10. Which authority is responsible for setting pharmaceutical prices in your country?

(Please tick all that apply)

Ministry of Health

Ministry of Trade

Ministry of Industry and Economy

Social affairs

Other competent authority, please specify:

Please specify the authority (or the committee):

11. Which of the policies below are used for pricing of in-patent pharmaceuticals in your country?

(Please tick all that apply)

Cost-Plus Pricing

External Reference Pricing (ERP)

Internal reference pricing

Value-Based Pricing (HTA, pricing based on cost-effectiveness analysis …)

Other, please specify

12. If HTA is used for the pricing of in-patent pharmaceuticals:

- How the value is measured?

- Does it apply to all kinds of products?

13. In your country, is price setting mandatory to obtain MA?

- Yes

- No

14. Is it possible to launch a new pharmaceutical with a free fixed price, without reimbursement?

- Yes

- No

15. Following MA, can price setting take place subsequently to the launch of a new pharmaceutical with a reimbursement objective?

16. If manufacturers disagree with decisions made by competent authorities on the price of a new pharmaceutical, are there any provisions for an appeal?

Yes

No

If your answer is Yes:

- Is this applied in practice?

- Does this lead to tangible results?

17. How frequently are prices revised for in-patent pharmaceuticals in your country?

(Please tick all that apply)

Every five years

Two years after initial registration

Other, please specify:

18. Are there events which can trigger pharmaceuticals’ price revision?

(Please tick all that apply)

When price changes in the country of origin

When price changes in key basket countries (if ERP is applied)

When a new competitor is launched in the market

When the manufacturer asks for price revision

Loss of data protection/exclusivity

Other, please specify:

19. Which authority decides for price revision in your country (if different from the authority fixing the price)?

20. In your country, are in-patent pharmaceuticals’ prices negotiated in parallel with their reimbursement or independently?

- Yes

- No

Section 3: Reimbursement and Coverage Decisions for in-patent pharmaceuticals

21. Are the reimbursement regulations and objectives clearly stated in your country’s legislation?

- Yes

- No

If yes please provide the law reference

22. Which criteria influence reimbursement decisions for in-patent pharmaceuticals?

(Please tick all that apply)

Health Technology Assessment (HTA)

Managed Entry/Risk Sharing Agreements

Other countries’ evaluations (External Reference Reimbursement)

Other, please specify:

23. In your country, is there a Formulary Management at national, regional, or local level (a list of reimbursed pharmaceuticals and conditions for the access to these pharmaceuticals)

- Yes

- No

- If you answered Yes, how is it managed?

24. Is there a list of pharmaceuticals freely made available by the government?

Yes

No

If yes:

- Please provide a link:

- What is the target population?

25. In your country, which organism decides for the reimbursement of in-patent pharmaceuticals?

26. In your country, who are the main actors involved in reimbursement decisions

- National insurance scheme

- HTA agency unit

- National regulatory authority

- Health care provider (hospital)

- Key opinion leaders/health care professionals

- Scientific Societies, etc.

- Other (please specify):

27. In your country, are prices negotiated for reimbursement decision?

- Yes

- No

28. Which price is used for reimbursement of in-patent pharmaceuticals?

Please tick that apply

Initial price fixed or proposed for the medicine

A reference price based on the same therapeutic class (IRP)

Price reset after negotiations

29. Are Managed Entry Agreements (MEA) used in your country to facilitate reimbursement decision?

30. If you answered Yes in the previous question, when were MEA first introduced in your country? (Please insert the year in the space below)