Abstract

This article addresses the adaptation of the 1869 French novella ‘Lokis’, by Prosper Mérimée, as a feature-length film in Poland in 1970 by Janusz Majewski, from a postcolonial and cognitive cultural perspective. The production marked the story’s hundredth anniversary, but also fell within the so-called ‘Small Stabilization’ under the authoritarian Gomułka regime. A foreign literary adaptation was ‘safe’ material for coded messages, as is typical of Socialist-era Polish cinema as well as of the Gothic. The figure of the werebear can be a foil for discussing defective masculine heroism in a familiar Polish nationalist mode, but also for recuperating a changing concept of Lithuania, where the story is set, as adapted from the pro-Polish, French-origin source material in a self-orientalizing process. This adaptation thus bespeaks a hidden and specifically cultural imperialism. Struggles over the origins, membership, and ownership of Polish culture are visible through certain innovations in Majewski’s work, including both new literary inclusions and the film’s English subtitling. While the film as received in Polish is not an unalloyed national self-projection, on Poland’s part, as a nuance-free historical subject, its packaging for global Anglophone audiences at least tries to suggest otherwise.

In 1969, Poland was nearing the end of the ‘Small Stabilization’, and entering a brief but sharp period of repression at the end of the premiership of Władysław Gomułka. Although censorship was a part of life in the Polish film industry throughout the Socialist era, during this particular time an ordinarily whimsical, sometimes negotiable or even corruptible system had become particularly rigid (Coates Citation2005, 17; Haltof Citation2002, 111).Footnote1 Adaptations of Polish literary classics would normally constitute ‘safe ground’ for the prestige market, and usually the domestic mass market too. However, it would make sense that at such a tense juncture, Janusz Majewski (b. 1931), an established filmmaker known for adapting European literature of the fantastic, might aim for an absolute minimum of controversy in choosing, for his latest work, a French text. There was even an occasion to celebrate, perhaps a conveniently distracting one: 1969 was the hundredth anniversary of the piece in question, Prosper Mérimée’s quasi-Gothic novella ‘Lokis’,Footnote2 which is set in the wilds of LithuaniaFootnote3 after Poland’s Third Partition, when this area was under the Russian Empire.

Polish filmgoers of the Communist era were well aware of the power of cinema as an allegorical tool. Although open political analysis would not normally appear in print media, the dissection of films for ‘hidden’, subversive commentary on current affairs was commonplace (Haltof Citation2002, 113).Footnote4 Majewski’s choice, and the manner in which the resulting production developed, confirm the role of the Gothic in both permitting certain taboos to be voiced, and providing a locus for other agendas to emerge and be propagated surreptitiously.Footnote5 His Lokis. Rękopis profesora Witembacha (1970) takes on many functions of the classic heritage film in mourning the szlachta, the enfranchised Polish noblesse, thereby implicitly condemning the violent Communist state. The changes made in the original story’s plot, which are strategic rather than numerous, pay lip service to Socialist-era conventions while reinforcing an underlying discourse of defective masculine Polish heroism, albeit ambivalently. These are all typical phenomena for the context (Mazierska Citation2008, 191; Ostrowska Citation2016, 32).

A postcolonial reading of Lokis can uncover how the reality of Lithuanian cultural dependency on Poland, born of linguistic-cum-cultural isolation, permits implicit Polish hegemony to hide behind a model of cohabitation within a Russian-ruled imperial space. My methodology relies on postcolonial and cognitive theory with film aesthetics, as guided by Charles Taylor’s politics of recognition, with close attention to be paid to ‘the tension between socially determined identity as a determinant of value, and dialogical human experience, versus inward derivation and Herderian authenticity’ (Taylor Citation1992, 31–32). If the postcolonial sensibility can bring new insights to analysis of cultural production from empires such as the USSR or Austria-Hungary (Mazierska, Kristensen, and Näripea Citation2014, 5), it might also help in decoding relationships shaped within a different, less violent, but still unequal context such as the kresy, the eastern borderlands of Poland – or, from another perspective, the multi-ethnic lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.Footnote6

Majewski’s film domesticates Mérimée’s Orientalist approach to Eastern Europe, coöpting French perceptions of Poland and one of its own modern ethnonational Others, Lithuania, and dramatizing the favourable French view of Polish nationalism.Footnote7 I argue that French Orientalism vis-à-vis Eastern Europe, coded positive from the dominant Polish point of view, maps seamlessly into a nostalgic quasi-colonialist view of the region of Lithuania in the film, where it supports a recuperative anti-Communist strategy. Majewski also exaggerates heteronormative masculine display, not least through his choice of casting Józef Duriasz as Szemioth, again in the service of a neo-Romantic Polish nationalism. Intriguingly, the film’s recent (2011) English subtitling simplifies and amplifies these tendencies at a key moment, while downplaying a residual tension that Majewski not only preserved but actually played up, as will be discussed.

Mérimée’s « Lokis »: French Fantasy, Polish propaganda

Mérimée’s novella excels as a violent conte fantastique. An erudite, repressed pastor, Wittembach, travels to Lithuania to collect material for his project of translating the Bible into Samogitian, a Baltic dialect closely akin to standard Lithuanian. His host, the nobleman Michał Szemioth, holds a rare Samogitian catechism in his library. Froeber, the family doctor, tells Wittembach that Szemioth’s mother, now a madwoman sequestered in their mansion,Footnote8 had been violently abducted by a bear two or three days after her wedding, and nine months before Szemioth was born. Szemioth himself is in love with the beautiful and mischievous Ioulka Iwinska, a young noblewoman, who had earlier passed off a modern romance by Adam Mickiewicz, Poland’s national poet, as a Samogitian fairytale to the unsuspecting pastor. Wittembach is at once charmed and troubled by the worldly Szemioth, whose attributes, especially his physical ones, seem by turns cultivated and beastly. On an outing into the wilds, the men come across a witch who suggests that Szemioth should become king of the beasts, as he is big and strong, with claws and teeth (!). In spite of the witch’s advice to the contrary Szemioth visits the house of Ioulka’s aunt, where he sees Ioulka dance the Rusalka – named after the siren-like water spirit of East Slavic mythology. Later Szemioth asks Ioulka to marry him, also against the witch’s advice, and she agrees. After a carnivalesque wedding, Wittembach, who has presided over the ceremony in spite of his misgivings, retires early; only to be horribly disturbed with the other guests the following morning when it is discovered that Szemioth is nowhere to be found – and Ioulka is in bed, dead, her throat torn out by a bite.

After a relatively unfavoured early career in the criticism,Footnote9 ‘Lokis’ has attracted some newer attention for its complex shell games, notably around the pastor’s show of flawed linguistic erudition, and around marriage and masculinity. Most agree with Cory Cropper’s persuasive reading, itself following Alan Raitt, of Mérimée’s narratives overall, according to which the objective is to defeat causal meaning (Cropper Citation2008, 63–64). The emphasis is on the lack of resolution, both in the short stories themselves and in the historical events and contexts that inspired them (Cropper Citation2008, 75). Similar to this is Scott Sprenger’s idea of Mérimée’s using mystification to reveal the irrationality of humankind, which denies and externalizes its violent desires (Sprenger Citation2009, 2). Kirsten Fudeman’s study of how Mérimée caricatures Wittembach as a less-than-reliable language expert lends a very useful platform for exploring aporia in ‘Lokis’, specifically how the story stages Polish and Lithuanian cultural contact in mystifying ways. Wittembach’s preoccupation with linguistic pursuits is ‘a deliberate piece of the mystification process constructed by Mérimée’ (Fudeman Citation2011, 122), with effects on the plot including the delay of Wittembach’s own marriage.Footnote10 Fudeman highlights a split within the story’s language discourses, according to a difference of scale: while Mérimée himself admitted that what Wittembach says about Samogitian and Lithuanian is not accurate, the pastor’s obsession does call attention to the relation between languages – Lithuanian and Sanskrit, written and spoken language, and so on.Footnote11 Fudeman cites several conversations in the story in which Szemioth and Wittembach converse in German, so as not to be understood by the servants or by peasants such as the witch, thus demonstrating unintelligibility even among fairly close relatives (Fudeman Citation2011, 115).

While both Fudeman and the narrative itself acknowledge, here and elsewhere, that Polish and Lithuanian are also in contact in this setting, neither points clearly to which is being used conversationally, as real-time speech, at several likely moments in the novella. Consider, for example, Dr. Froeber’s first words to the dowager countess, as witnessed by Wittembach (Mérimée [Citation1869] 1976, 1051); Wittembach’s conversation with the servant, when he complains of having seen Szemioth up in the tree (Mérimée [Citation1869] 1976, 1057); his first conversation with Szemioth, when the count introduces himself (Mérimée [Citation1869] 1976, 1058), and so forth. Overall, ‘Lokis’ gestures ostentatiously towards the linguistic complexity of Lithuania as it was, but finesses the distance between the Baltic Lithuanian languages – Highland/Aukštaitian and Lowland/Samogitian – on the one hand, and Slavic Polish on the other. It underlines, however, that the latter is a high-literary language and that all the nobles in the story speak it fluently, either because they are natives (Ioulka) or at least highly educated (Szemioth). The same does not necessarily apply to Lithuanian. Ioulka might well style herself as the ‘muse de la Lithuanie’, writing her portion of the wedding invitation to Wittembach in Samogitian. While I would agree with Fudeman that Ioulka’s writing in Samogitian, whereas Szemioth composes in German, reinforces the gendering of ‘feminine’ dialectal vs. ‘masculine’ written language (Fudeman Citation2011, 119; cf. Mérimée [Citation1869] 1976, 1083–1084), I would differ with Fudeman’s view of how the language choices foreshadow her eventual doom. Ioulka is slain as a bride, hence denied being a mother, not because the ‘mother language’ is the weaker of the two but because, like Szemioth, she is a linguistic impostor. Although her roots are not specified in the story,Footnote12 evidently, she is either Polish or Polonized: while she is well-educated in French, German, and Italian, her grasp of Samogitian is flawed, as Szemioth and her own aunt agree (Mérimée [Citation1869] 1976, 1062, 1071). She cannot incarnate or assimilate the ‘mother language’ of Samogitian because it is not fully hers; he cannot have recourse to the ‘logic of German’ because of his animal, Lithuanian roots. And so her and his respective impostures combine in violence.

It is well known that in the mid-19th century the term ‘Lithuania’ did not designate an organized, ethnonational state. The reality of Lithuania was of a plurilinguistic space, inhabited by a mixed community of native speakers of Lithuanian, Polish, Yiddish, and other languages within a polycentric cultural field, and a shifting political one. As Thomas Venclova says, ‘the matter of Lithuanianness or Polishness is historically badly confused because the notion of ‘a Lithuanian’ or ‘a Pole’ changed over the centuries’ (Citation1979, 38). Within this brindled zone, Lithuanian speakers in the modern era obtained cultural and literary innovations through the medium of Polish, as they had for centuries before (Sverdiolas Citation2006, 235). The Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, in a letter to his Lithuanian friend Venclova, speaks tellingly of his parents’ generation, of Lithuanian speakers who regarded Polish culture as denationalizing, and of Polish speakers who behaved contemptuously towards the ‘Klausiuks’, a nation of peasants: ‘undoubtedly, underneath the sentimental attachment to the idea of the Grand Duchy, the dream of domination lay hidden within some of the gentry descendants’ (Miłosz Citation1979, 10; cf. Bakuła Citation2006, 18). Venclova is even more explicit as to the longstanding reality of growing Polish cultural hegemony in the area: ‘Polish cultural (as well as social) domination in Lithuania in the 18th century began to threaten the Lithuanians with the loss of their language and their historical identity. Add to that hundreds of years of painful national subordination…’ (Venclova Citation1979, 35).

Such hardened attitudes are, as both Miłosz and Venclova point out, partly the products of Romantic nationalizing discourses. It is also true that Polish hegemony was much more conducive to the survival of Lithuanian language and culture than the Russian alternative (Wandycz Citation1974, 247). Nevertheless, Poland certainly saw itself as a civilizing, enlightening influence in the area (Wandycz Citation1974, 35). The history of the Commonwealth from the mid-16th century onward involved a comprehensive process of Lithuanian linguistic and political adaptation to Polish norms (Kiaupienė Citation2001, 83, 85–87). Hanna Gosk describes the ideological polarity of the Kresy as split between ‘Western Europe, the Polish noble’s manor, Polish Catholicism, the Polish language as a carrier of high culture, awareness of a long-lasting tradition and historical mission, which justifies the right to the land … while at the opposite pole, the barbaric Tatar East, the dark Ruthenian village, Orthodox Christianity, folk dialects … elemental forces instead of social structures’ (Gosk Citation2008, 33).

The evident class division corresponded to a linguistic division. Modern Lithuanian intellectuals wrote in the Polish language, even in the case of some militant Lithuanian nationalists as late as 1880 (Wandycz Citation1974, 244–245).Footnote13 Moreover, Poles from Lithuania viewed themselves as culturally distinct from western Poles, on account of their roots and, often, their own pluriligualism; but they also ‘…presumed that Polish culture in general was of a higher quality than that available in the Lithuanian or Belarusian languages’ (Snyder Citation2003, 54–55).Footnote14 Prizel speaks of the noble elite, the szlachta, who in the first half of the 19th century held and fostered a Polish national identity, as holding ‘the messianic notion of having been endowed with a civilizing mission and a racially superior ruling class’ (1998, 38). Prizel also underlines the instrumental role of the szlachta in forming Polish national identity in the modern period, up through the Second Republic of 1918–1939 (Prizel, Citation1998, 39, 42) – a popular if not uncontroversial idea, as will be discussed presently. Wojciech Olszewski’s language of class, in his version of these realities, is particularly telling: ‘cet «état» comprenait pratiquement tous les citoyens possédant tous les droits… Dans ces conditions, la noblesse était plus qu’une classe, elle s’identifiait à la nation’ (Olszewski Citation2006, 203).Footnote15 The heroic, class-based model of the nation had been changing in the nineteenth century, following the trauma of the Partitions, with a developing sense of a Christlike Poland suffering from its violent national eclipse, and particularly with a stronger ethnolinguistic identity (Coates Citation2005, 6–7).

Prizel approvingly quotes the literary scholar Wiktor Weintraub, who says that, uniquely in the Polish case, language was not the basic element of national consciousness in the Romantic era. However, Weintraub immediately says next that ‘Polish patriotism did of course mean to be attached to the Polish language as well as its literature and folklorist tradition’ (Weintraub in Prizel Citation1998, 44). This apparently contradictory account leaves a question mark over the role, and value, of other languages and traditions within a restored and allegedly multinational Polish state. Robert Frost, arguing in a similar vein to Weintraub, spends some time explaining away the differences between Polish and Ruthenian, which are indeed closely related; but he neglects to mention the Lithuanian language sensu stricto (cf. Frost Citation2005, 216–217), which of course is markedly different from both. More recently, Bogusław Bakuła has explicitly identified Polish fiction (writ large) and historiography as complementary arms of a commemorative, dominating discourse (Citation2006: 19, 26).

All this historical background matters because the dominant Polish self-image of an oppressed and civilizing nation strongly influences the French view of Poland, both as a cultural entity and as a geographical space. To the extent that what Mérimée calls Lithuania is a multicultural space, it was perceived in France to have Oriental trappings that serve partly to exoticize its inhabitants, in the negative sense, but also to highlight and privilege cultural Polishness at the expense of other cultures within this ill-defined and contested zone. Indeed, Mérimée’s calling this zone ‘Lithuania’ is itself innovative, for a French audience. ‘Le concept de Pologne, dans sa dimension symbolique, continue [au XIXe siècle], en dépit de la disparition politique du pays, de désigner le territoire mal défini de cette partie à la fois orientale et septentrionale de l’Europe’ (Rosset Citation1996, 70).Footnote16 While earlier French discourses of Polishness emphasize characteristics of hybridity and indeterminacy, these qualities do not extend to observed ethnicity or language, from a French perspective; they pertain only to the character of the Polish people and of their land itself (Rosset Citation1996, 91).Footnote17

Despite Mérimée’s more precise approach to the space, the degree to which Romantic szlachta nationalism could have shaped his vision is not to be taken lightly. A sophisticated mix of pro-Polish propaganda had been circulating in France at least since the Third Partition, targeting distinct socio-economic strata through various media, from newspaper cartoons and lithographsFootnote18 to vaudeville and popular song (Devitt Tremblay Citation2018, 14, 235). Casimir Delavigne’s 1831 song, ‘La Varsovienne’, is only the most famous of sundry pop culture examples (Devitt Tremblay Citation2018, 80 passim). Active contributors included Balzac, in his journalism no less than his fiction (Forycki Citation2016, 336–337). Moreover, it is of course known that one of Mérimée’s key sources for ‘Lokis’, alongside Mickiewicz’s celebrated epic Pan Tadeusz (1834), was La Pologne captive et ses trois poètes (Mickiewicz, Krasiński, Słowacki) (1864), by Charles Edmond (né Edmund Chojecki) – a classic of nationalist scholarship (Raitt Citation1970, 331).

The satirical French attitude towards this discourse in later works such as Jarry’s Ubu roi (1896),Footnote19 while arguably familiar now, dates from at least a generation after Mérimée’s death. Sprenger, for one, does not see any irony to the way in which Mérimée incorporates the idea of Catholic Poland as tutor and civilizer, despite Merimée’s sharp anti-clericalism and hatred of superstition (Sprenger Citation2009, 7). Ubu roi has itself been adapted as a vehicle for domestic political satire in post-communist Poland (cf. Ubu król, 2003, dir. Piotr Szulkin), despite its less-than-solemn treatment of that country’s Romantic nationalist project (cf. Youker Citation2015, 534–536). Overall, it must be made clear that, in the later 1860s, Mérimée was writing in the context of a then-established, now-familiar nationalist discourse of a noble, heroic, civilizing, suffering Poland, and writing for an audience – France – that had been carefully prepared for such a message for some time.Footnote20 Such is the discursive background to the semi-Polonized Lithuania of ‘Lokis’: a vision of a fabulously heteroclite yet sui generis exotic zone,Footnote21 whose cultural and political tensions are not clear from Mérimée’s depiction, in which Polishness occupies an unspoken default position akin to whiteness.

Ewa Mazierska, Lars Kristensen and Eva Näripea say that, under the Iron Curtain, minorities such as Silesians and Mazurians experienced a double colonization, both Polish and Soviet (Mazierska, Kristensen, and Näripea Citation2014, 11).Footnote22 They point out the problem of whiteness vis-à-vis interpellating Europeans as colonized by other Europeans (Mazierska, Kristensen, and Näripea Citation2014, 16), suggesting that the USSR, for example, would have engaged in a ‘hidden colonialism’ (Mazierska, Kristensen, and Näripea Citation2014, 17).Footnote23 However, they also underline the tangible, material roots of colonial relationships, which could be unpredictable and situationally reversible. They cite Polish traders smuggling Western consumer goods into the USSR, profiteering like settler whites from the Soviet ‘Injuns’ [sic] and plundering their treasure (Mazierska, Kristensen, and Näripea Citation2014, 9). I suggest that a different but comparable double colonization operated, with some allowances, on Lithuanians living under the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century, and that a subtle colonial attitude drawn from yet earlier contexts could underlie Polish perceptions well into the 20th. Hints of situational Polish consumption, and perhaps adoption, of Western colonial attitudes towards other subjugated peoples appear in canonical Polish popular culture, even in the Stalinist era. In Wajda’s Pokolenie/A Generation (Wajda Citation1955), for instance, set around 1940, there are repeated clear mid-shots in Aunt Valerie’s bar of a clock whose design, of a cartoonish African boy with huge eyes, exemplifies racialized kitsch.

In tracing the influence of the szlachta discourse on French attitudes towards Poland in Mérimée’s era, I hope to have more fully grounded a postcolonial reading not only of ‘Lokis’ itself, but also of its nachleben, specifically Majewski’s work. Kristensen has already proposed using the postcolonial perspective to reveal how a much more established film genre in Poland, the war epic, ‘…on the one hand, eludes nationalism, but, on the other, promotes national centricity. This, I believe, is particular to the postcommunist condition, where national visibility is paramount’ (Citation2016, 26). While in agreement with Kristensen’s methodology and analysis, I hope to prove that the limits he applies to generic and historical scope are not needed. In terms of a cultural imaginary, at least in the Polish case, it is entirely possible for genre cinema even in more hardline episodes of the socialist period to promote nationalism.

Majewski’s adaptation, its context and stakes

Majewski’s film is at least the fourth performance adaptation of Mérimée’s story to date. Previous ones include Charles Esquier’s Citation1906 stage version, a Russian play from 1924 by Anatoly Lunacharsky, Medvezhya svadba/The Marriage of the Bear, and an eponymous Soviet film adaptation the following year, directed by Konstantin Eggert and Vladimir Gardin.Footnote24 All are easily recognizable from each other and from the novella, with allowances for degrees of innovation and transformation. The early Esquier play is the most divergent, with simplified plot and psychology. Here I shall pursue the Polish film’s innovations in some detail, comparing the novella’s and the film’s staging of a cultural tug-of-war over the identity of the chief agonist, Szemioth. While identities and national labels, such as ‘Lithuania’, have changed in meaning over time, the linguistic nationalism underlying Mérimée’s approach enables a modern Polish appropriation, through this character, of cultural privilege, itself imbricated with a repressed cultural hegemony over the Lithuanians. This claim coincides, by turns, with a multifaceted ambivalence towards cultural but also social and political hybridity, which Szemioth to become the vehicle of a similarly complex self-orientalizing and mythologizing process. At the same time, the film’s turn towards its Romantic roots apparently conjures one ghost too many, a problem that its modern framing, in the form of subtitles, tries to gloss over.

Majewski’s choice of ‘Lokis’ could be called natural for him. Billed as the first Polish horror film (Grzelecki Citation1972, 54), Lokis forms an apparent ‘bridge’ within a portfolio of work including macabre shorts from the late 1960s, other Mérimée adaptations for television (‘Avatar’ and ‘La Vénus d’Ille’), and prestigious literary adaptations for which Majewski was to become celebrated in the 1970s. Stanisław Grzelecki describes the film as ‘partly romantic and partly sinister’ (Grzelecki Citation1972, 54). Marcin Giżycki does not compare it with those of Majewski’s earlier works, Rondo (1958), Kapelusz (1961) and Szpital (1962), that for him qualify as ‘Surrealist grotesque’, implicitly suggesting a more realist and traditional approach (Giżycki Citation2014, 88). Marek Haltof describes the film as a kind of threshold for the director: ‘In The Bear (Lokis, 1970), based on Prosper Mérimée’s short story, Majewski continued his fascination with the horror genre. Critical acclaim, however, allowed him to make subtle adaptations of the prewar Polish literary canon’ (Haltof Citation2007, 118).

Haltof’s warmer appraisal of Majewski’s later work could coincide with a common generic prejudice. The implication seems to be that films from within the horror genre would have difficulty in being subtle, or even anything other than the director’s hobbyhorse.Footnote25 Radosław Pisula points out that because of official disfavour, there was a lack in Poland of a recent tradition of genre films overall (2016, 95).Footnote26 However, none of the criticism complains that Lokis diverges from Majewski’s typically high standard of production design, nor even that it is particularly gory, despite being ‘the first Polish horror film’. Jacek Fuksiewicz, who calls it a ‘film d’épouvante d’esprit romanesque’,Footnote27 sees within Lokis ‘des qualités de langage et d’exécution qui manquent souvent aux films polonais’ (1989, 140),Footnote28 while Pisula counts it as the first of four main, rare examples of successful Polish versions of ‘Western’ genre output, of any genre, in Socialist-era popular screen.Footnote29

The question of subtlety needs to be posed in an industrial and historical context. Majewski’s production unit (zespół), Tor, was one of only two not to be liquidated in 1968 during a general crackdown on the culture industry (Wach Citation2013, 259). Lokis was one of only 24 feature films produced in Poland for 1970, a small figure for this country and era (Iordanova Citation2003, 24). Patently, Majewski was under intense political, economic, and social pressure either to conform to the current ideological demands, or to avoid them studiously, perhaps to fly under the radar with a supposedly de-politicized and generically dismissable, ‘foreign’ work.

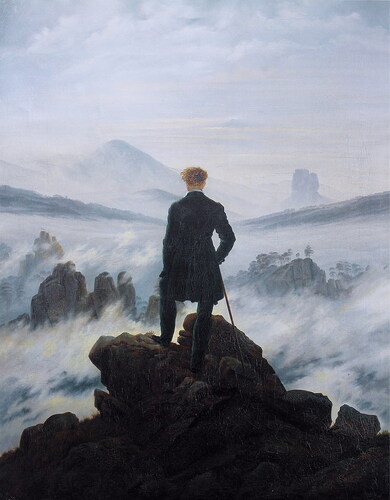

Philippe Met gives a helpful overview of Majewski’s main innovations within the film, highlighting their creative response to and, Met argues, recreation of the spirit and function of the novella (Citation2017, 152). These include: a train ride at the beginning, in which Wittembach encounters Ioulka, Countess Dowghiełło, and the governess, with a journey by sled and train at the film’s end to complete the frame; a sequence in which Szemioth reveals that he keeps a hoard of captured ‘animals’, including the witch (!), all of whom he releases later as part of the wedding celebrations; and a dramatic standoff at the top of a ruined castle, where Szemioth contemplates suicide, the text drawing on Juliusz Slowacki’s Kordian,Footnote30 and the mise-en-scène clearly inspired, as Met says, by Kaspar David Friedrich’s celebrated painting, Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer/Wanderer above the Sea of Clouds (ca. 1818, cf. and ; cf. Met Citation2017, 153–154).

Met says that Majewski’s interpretation overall is faithful to the manner and style of Mérimée’s story, with these various additions complementing and contributing to them regardless of any incidental narrative departure (Met Citation2017, 149, 152 n. 9). Thanks to the often lush location shooting, ‘Il se dégage du film une couleur locale accrue, qui est aussi affaire de vision ou de mise au point’ (Met Citation2017, 149).Footnote31 I agree with both statements as given, although they might possibly reflect an older habit in adaptation studies of judging the film on the basis of its accuracy in ‘recreating the text’ (after Venuti Citation2007, 25–28). I would like to compare two of the film’s innovations, one that Met has discussed and one that he has not, in order to reveal what I see as potential Western misprision of the film’s Polish national discourse, but also its intriguing and ultimately inconclusive evocation of problems of class in Polish culture.

In the ending frames to the film, where the train pulls away into the distance, Met perceives a reference to the deportations of the Holocaust: the train would betoken deportation to the Nazi death camps (2018, 156). This message would be reinforced through metonymy, given that animal carcasses – including a bear, which as Met suggests is almost certainly the transmogrified body of Szemioth – are shown from the train windows, lying by the tracks, perhaps evoking bodies by a mass grave. While not wanting to dismiss this interpretation, I do find it debatable. For a start, framing a film with a train journey was already a typical device in Polish cinema of the mid-1960s, with no necessary reference to the Holocaust implied (Garbicz Citation1975, 62). Another problem with perceiving Nazi death camp commemoration in Lokis lies in what is shown in that film’s closing sequence. After Wittembach has boarded the train, we see that it bears the frost-covered emblem of the doubleheaded eagle carrying an orb and a sceptre: a common Russian crest. It is worth spending some time on this iconography.

In contrast to the Russian eagle, the Polish eagle is single-headed, carries nothing in its talons, wears a simpler crown (or no crown, during the Polish People’s Republic), and – crucially – is white. However, the emblem in Lokis appears quickly, in two shots, and like many of the train windows is covered almost completely in hoarfrost. One might be forgiven for thinking, in the blink of an eye, that it is a white Polish eagle.Footnote32 It can however be seen at the symbol’s edges that the feathers are russet, standing out against the dull grey of the carriage (cf. ).

Iconographically speaking, a Polish home audience would not necessarily have been conditioned to read ‘train in Poland’ as signifying ‘death camps’, whereas modern Western audiences might. However, as the camera lingers in closeup on the bear’s body, Wittembach prays for the departed. Spurred on by Wojciek Kilar’s sinister non-diegetic score, and by the pastor’s unease as he looks at the dead bear, a Polish audience might well react with dismay.

Wittembach, as interpreted soberly by Edmund Fetting, is a flawed but sincere mourner and witness to a crime scene, himself to be carried away later by a manifestation of Russian modernity and power. The innocent dead animals might be approximated to the ‘natural people’ of the land, crushed by the Russian Empire – perhaps the Soviet one too? A frosted-over icon of Russian power might well allude to Siberia, a justifiably notorious frozen waste to whose gulags so many ethnic Poles, from within the country and abroad, were condemned.Footnote33 It is also possible that the implied responsibility for these killings extends to those who are ‘frosted over’ with Polishness, but actually serve the Empire: the collaborationist Polish socialist state (Hartford in Met Citation2017, 156 and n.). Such messages would be immediately relevant to the film’s mainstream domestic audience.

Nation, madness, and heroic (?) recuperations

Met’s attention to the Romantic origins of Majewski’s iconography, and to its debt to Friedrich’s painting in particular, gives a strong basis for approaching another innovation in the film, unmotivated from a plot point of view and absent from Mérimée’s novella, which Met does not have space to discuss. Two thirds of the way through, immediately after Szemioth abandons his suicide attempt at the ruined castle by firing his pistol into the air, the film cuts from the gun firing against a full sky (1h04:08) to Szemioth delivering a dramatic monologue in a small theatre space in his mansion (full sequence: 1h04:09 to 1h06:11). His initial stance is mid-close, one eighth profile, mid-stage right, almost identical to the blocking at the end of the previous scene. As he paces about the stage, the camera angles are consistently low, thus showing him in a heroic aspect. Quick matching shots, in contrast with the long takes on Szemioth as he delivers his monologue, establish that Wittembach (in medium closeup, from a delicately raised angle) has been watching him. Behind the stage stands a bright floral backdrop soon revealed to be a parkland scene. After a quick exchange in which it is established that the theatre was built by Szemioth’s grandfather, the characters are called away and back into the main, Mériméean narrative.

It is worth unpacking this interlude in light of its predecessor, the standoff atop the ruin, but also in context with the film’s earlier examples of unhinged nobility, with reference both to what it shows and what it tells. In the novella Szemioth tells of having fired a gun in a somnambulant state, narrowly missing a companion (Mérimée [1869] 1978, 1078), and speculates about a cliff-edge standoff and the longing to kill with a loaded gun (Mérimée [1869] 1978, 1080, 1081); but we never see him do so. Doubtless the censors would have been pleased to have such a protagonist be so deeply cracked, and volatile.Footnote34 Now, at no point in Merimée’s novella is Szemioth portrayed as a captor.Footnote35 There is not a hint of his trapping and caging the witch, as in the film; indeed he reacts to her revelations with embarrassment, then sincere hospitality (Mérimée [1869] 1978, 1070). In contrast, Majewski plays up Szemioth’s cruelty as a man long before he transforms, it seems, into a beast.

Majewski’s exaggeration of Szemioth’s undesirable qualities does not hold this character back from invoking true heroism. Polish cinema was already laden with ambivalent characters who blend bohaterstwo (‘heroism’) with bohaterszczyzna (‘heroic excess’), not to mention other iconic flawed heroes such as Maciek, in Andrzej Wajda’s celebrated Popiół i diament/Ashes and Diamonds (1958) (Mazierska Citation2008, 39, 50 passim). As Mazierska notes pithily, Polish culture is awash with mad patriots (Mazierska Citation2008, 38). ‘There is a close link between patriotic madness alla polacca and suicide’ (Mazierska Citation2008, 39, sic). All this allows us to appreciate the referential complementarity between the castle scene and the stage scene, in which Szemioth speaks of past generations lost to an unspecified heroic cause. At least, this is what he says according to the English subtitles.

Without knowing the Polish, from the 2011 international release, a global audience would be led both visually and verbally to view both scenes as having been inspired by Kordian. The film’s original dialogue quotes an entirely different work: the second (earliest) part of Mickiewicz’s Citation1823 work, Dziady. It is very hard to overstate how celebrated this piece is, and has been, in its homeland. Public performance of it in Warsaw was suppressed in January of 1968, for its anti-Russian and pro-religious sentiments; protest was immediate and vigorous, the response was heavy-handed, and the whole affair contributed substantially to the violent uprisings in March that year. It seems audacious enough on Majewski’s part to have quoted Dziady at all, so soon after the crackdown. It beggars belief to suggest that the censors would not have noticed a monologue taken from it. The selection’s content is both more violent and more ambivalent than a Kordian-inspired elegy: it is the Night Birds’ Chorus, wherein various raptors who embody a vicious landowner’s former serfs promise to devour him in the afterlife, all the way down to his liver (Mickiewicz [Citation1823] 2016, 157).Footnote36 Szemioth delivers the lines with gusto, dramatically unaware that he could be apostrophising himself and foretelling his own doom – or perhaps he revels in his own dismembowelling? Either way, the lines both reinforce his own links with violence, and by extension the message of noble decadence, and root the film much more clearly in the troubles of its day.

A full pursuit of this issue’s complexity requires a few more contextual reference points. Adam Lowenstein has explored how horror cinema in particular overcomes the problem of representing national trauma. To speak of a national trauma means to perceive events as wounds (Lowenstein Citation2005, 1; after Caruth Citation1996, 3–8 passim); which means that in order to work, an allegorical moment must carry off a complex process of embodiment (Lowenstein Citation2005, 2). Lowenstein evokes Lyotard’s concept of the différend as a model for opposing forces in a cultural struggle to be broached by a given film (Lowenstein Citation2005, 5), and asks, ‘How does this film access discourses of horror to confront the representation of historical trauma tied to the film’s national and cultural context?’ (Lowenstein Citation2005, 9). To give some examples, he says that it is unthinkable to address the idea of contemporary ‘France’ without the Occupation, of ‘Britain’ without the Blitz, ‘Japan’ without Hiroshima, ‘America’ without Vietnam. ‘Poland’ unfortunately would have a choice of such events, not least of which the Warsaw Uprising of 1944; but in the time-context of the Small Stabilization, for certain informed members of the Polish mainstream – which means non-Jewish – audience, another candidate would be the 1940 Soviet massacres of the Polish officer corps at Katyń.

To discuss Katyń was a firm taboo throughout the Iron Curtain era (Röger Citation2013, 202), but it was still ‘a place of crucial importance for a certain nation’ (Mazierska Citation2011, 42). Although wider discussion of this event was well-suppressed by successive pro-Soviet governments (Zwierzchowski Citation2020, 3), it certainly was well known in Polish film school circles. Andrzej Wajda’s father was one of its victims. In the film’s two ‘Romantic drama’ scenes, a dense network of visual cues builds on Szemioth’s established identity as ‘cracked noble’ to point towards this more recent massacre. When he shoots the gun into the air, we see it in closeup against the sky, the camera then panning up into the ether before the cut to Szemioth, alive and slightly bowed, against the sylvan backdrop of the stage (cf. ). As the scene develops through Szemioth’s and Wittembach’s conversation, the metonymic link between the stage space itself and Szemioth’s father, hence his paternity/descendance, invites us to reflect on the loss of noble ancestors in general. The contrasts of pose between the Friedrichian Szemioth on the castle wall and, in the next scene, the declaiming, acting, embodying Szemioth, against a forest backdrop, further cement the contrastive and interpellative link between one ‘bad’ noble, himself, who survived, and so many good (and noble) Polish officers who were shot dead, against another forest backdrop. Indeed, whereas the choreographic allusion to Friedrich in the standoff scene certainly could be a more aesthetic, possibly psychological reference to the sublime, in its form of an overwhelming personal situation (Szemioth’s growing insanity), its carry-over into the stage scene can also suggest that a separate overarching referent for the audience, if perhaps they were identifying with Szemioth, might be Katyń.

The problem with all of this is, of course, Dziady, and behind it the historic dimension of class. Promoting a nostalgic modern ethnonationalism in this case requires some skating over entrenched disagreements as to which class, specifically, really ‘owns’ Polish culture. Czesław Lewandowski has explained how post-1945, the Leftist sociologist Józef Chałasiński proposed the noble-origin Polish intelligentsia as a social class, ‘a layer alien to modern society, anachronistic in its ambitions and therefore without a future’ (Lewandowski Citation1990, 78–79 passim). Lewandowski carefully details several debates over this. Key objections include that, after Stanisław Ossowski, the intelligentsia, who were mostly from petty nobility, could be compared to the noblesse only insofar as they claimed social prestige (Lewandowski Citation1990, 81, 83); and moreover that, after Stefan Kiniewicz, their ranks drew from a motley of bourgeois, Jews, foreigners, and a few peasants (Lewandowski Citation1990, 81).Footnote37 Chałasiński at least took these criticisms respectfully, and his views developed to the point where he wrote frequently of ‘the legend-myth of the noble origin of the intelligentsia’ (in Lewandowski Citation1990, 92). Nonetheless, his generally pessimistic endorsement of this very myth, from a Leftist perspective, proved deeply influential to later writers such as Szczepański (Lewandowski Citation1990, 95). It also met with official acceptance. Now, returning to Lokis, the raptors whose lines Szemioth quotes in the Polish dialogue are at once reincarnations and avengers of the abused common people: not Szemioth’s stock. Presuming them to be on the side of the angels, it would thus become harder for ordinary audience members to identify with him.

As for Katyń, the event is impossible to commemorate if one has never heard of it, or has no stake in it. It is intriguing to think that the visual discourse, rooted in fine art as well as in a less politically challenging text, might speak to a more patrician audience, whereas the dialogue – presaged by the gunshot? – might appeal to the aggrieved masses, while partly displacing the violence from them to the noble character who conjures it. Of course, the subtitles hide from outsiders the fact that there is any internal social tension in these scenes at all. Still, they does not discount the possibility that Majewski’s staging of Kordian vis-à-vis the raptors – likely at the suggestion of Andrzej Biernacki, who was the film’s literary consultantFootnote38 – might also stage an unresolved debate about who really creates Polish culture.

Certainly, there are other possibilities. Perhaps, by suggesting that Dziady was not as out of keeping with official doctrine as it had been thought (by featuring a pro-proletarian passage within it), Majewski would be offering an olive branch to the authorities. Perhaps, by associating the piece with a deluded antagonist, he would be trying to come across as ‘cheeky’ rather than truly subversive. Either way, these additions make Szemioth carry an increasingly volatile and incoherent blend of discourses. From a literary point of view, we can imagine what pleasure Mérimée might have taken at such obfuscation even before the subtitlers’ choice. Did they think Dziady was too local, its concerns too complex, to appeal to international audiences? Did a more restrained, Kordian-esque allusion to nameless, perhaps fungible past traumas seem more bankable? Or, was the violence in Dziady too radical, too iconoclastic to be unleashed?

It seems telling that Mickiewicz’s irreverent work came to be overlain by a piece that was written partly as a riposte to it (Kraszewski Citation2018, 7); not to mention that Majewski’s Szemioth, by indulging in a flight of fancy atop a ruin, becomes a bridge-figure of sorts between Kordian and Słowacki himself, who once wrote of his ‘Sophoclean’ childhood dreaming atop the castle on Bona Hill, in a letter to his friend Zygmunt Krasiński (Kraszewski Citation2018, 11). And yet, in the original film at least, Majewski gives Mickiewicz the last word. The two Romantic nationalists thus hang, in tension, with a barely veiled, literary threat of peasant violence hanging over the seeming balance.

Part of Majewski’s skill at sailing so close to the wind, in so many ways, involves his throwing a few bones to pro-Soviet viewers, notably at the beginning and end of the film. By transforming the role of Ioulka’s governess, from a non-speaking Frenchwoman to a Hollywood stereotype of the prissy and coy Englishwoman (compare Mérimée [1869] 1978, 1072), he adds a Cold War touch in caricaturing a traditional Polish ally, yet well-known Soviet adversary. When the governess bridles at the thought of tea without milk, Ioulka’s aunt patiently explains the cultural differences in serving it. It is tempting to see their conversation as a staging of reason and unreason, with unusual positions thereby assigned to East and West. Much later, at the fateful wedding feast, we hear that the lovely toy bear music box came from St. Petersburg. That it horrifies Szemioth, who drops it and so breaks it, is a token of impending doom. The toy’s destruction is both shocking in itself and a sign of coming misfortune: injury to a Russian product is thus iconically tragic. And of course, there is the Russian Imperial eagle device, beautifully frosted over on the train carriages, such that it might even look ‘romantic’. Such Russophilic touches might help the film to disavow its nationalist appeal.

The film’s casting plays a part in sealing Szemioth’s connection to the tragic Polish noblesse. The patriotic heritage cinema of Poland revels in ‘tall, dashing horsemen with flowing blond locks’ (Iordanova Citation2003, 50). Although his costuming and hairstyle are more Belle Époque, the alluring Józef Duriasz dominates the scene as Szemioth, his blond hair, rangy limbs, and height lending contrast with the smaller, darker Fetting (Wittembach) and indeed with all the rest of the cast. In the novella, Szemioth has very dark hair (Mérimée [1869] 1978, 1078), and from Esquier’s play he is described as pale, with a solid red beard (Esquier [Citation1906] 1907, 21) – presumably betokening volatility, animality, and danger. Duriasz’s bright blue eyes are piercing but hooded, with little or no makeup to cover the redness underneath; at 34 he is a bit more weathered, and possibly more virile than the vision of Szemioth in the novella, where the character is at most 27 (Mérimée [1869] 1978, 1053; cf. ). The bath scene, another innovation of Majewski’s, shows off his powerful adult man’s body: he is to be looked at and noticed, like Maciej in Popiól i diament (Mazierska 2008, 50).Footnote39 Even in scenes of affliction, he is powerful: his cries and gnawing at the pillow during the nightmare sequence look and sound realistic and frightening. Duriasz does ride a horse well, as does Mérimée’s Szemioth, despite the character’s dislike of such creatures. His embodiment is thus vital, unpredictable, expressive, and also wholly recognizable as a local type: as a figure of suffering adult masculinity, he marks only a minor generic departure from the tragic cavalryman.

It is tempting to see an Imperialist, Orientalist agenda behind Mérimée’s interaction with the lands to the east.Footnote40 Without dismissing this, I can say that the novella’s evaluations of, and implications for, the various easterly peoples and cultures are not interchangeable. Some of its apparent targets, the Poles, had pre-existing imperial agendas of their own, which harmonized with Mérimée’s perceptions; indeed, they may probably influenced him a priori. Whereas in historical cultural discourse, Poland shares the common Eastern European identity-perspective of the invaded (Iordanova Citation2003, 43), historic Polish attitudes towards Lithuania bespeak nostalgia for a particularly cultural imperialism. The later appropriation and adaptation of Mérimée’s novella at a time of bitter national contest, in order to produce a commemorative and recuperative device, would suggest a cosmopolitan narcissism, in the proper sense, on a national scale. As a participant in the Polish national discourse, Majewski saw, in Mérimée’s ‘Lokis’, the opportunity for Poland’s national self-projection as an individual and nuance-free historical subject.Footnote41 However, possibly at Biernacki’s suggestion, he both resisted another totalizing discourse and kept to the spirit of Mérimée, by refusing an easy solution to the social-cum-cultural conflict inherent in that national self-formation.

Biernacki’s introduction to ‘Lokis’ ends with an anecdote of how the real Franiszek Szemioth’s great-nephew claimed, in 1939, that Mérimée’s story was inspired by a real family legend (Biernacki Citation1969, 21, cf. 19): an audacious and obfuscating simplification, and a self-serving claim. That the later subtitlers of Majewski’s work sought to obfuscate its nuances, perhaps anticipating contemporary neo-Romantic Catholic nationalism, seems only just as well. In Althusserian terms (cf. Althusser Citation1965, 112–113), the character of Szemioth, in all his contradictions, develops further from Mérimée’s more distant and equivocal perspective into a filmic vehicle for the ‘structure in dominance’ that is the Kresy myth: a subtle and powerful longing for the Polish nation.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the anonymous reviewers, I thank Philippe Met, Dariusz Skórczewski, Dorota Ostrowska, and my research assistants, Dawid Czeczelewski and especially Michał Romaniuk, for their invaluable assistance with this piece. I also thank the University of Dundee for a funded writing retreat, which proved most helpful for the piece’s final revision.

Disclosure statement

There is no conflict of interest to report, concerning this piece.

Notes

1 Coates gives a detailed overview of the history of censorship in Socialist Poland (2005, 74–80 passim); see also Zwierzchowski (Citation2020). Once a script was approved, the director usually had considerable leeway over the production process. There was no censor on set. However, a displeasing end product could be distributed poorly or not at all.

2 Hereafter, the 1869 novella by Mérimée shall be styled as ‘Lokis’, while the 1970 film by Majewski shall be styled as Lokis.

3 This name has several contrasting historical meanings. Discussion will follow.

4 Hendrykowski speaks of Socialist Polish cinema’s ‘Æsopic film language – hermetic cultural code’ (Citation1996, 633). Werner echoes the Æsopian reference, underlining that such messages were ‘infallibly deciphered by the public’ (Citation2007, 5).

5 On the film’s Gothic character, see for example, Met (Citation2017), 151. Biernacki mentions Hoffmann, Poe, and Shelley as influences (1969, 20).

6 The heyday of the Commonwealth is usually quoted as 1569–1772. For a firm grounding in postcolonial approaches within Poland to its double role as colonizer and colonized, over the centuries, see for example, Kołodziejczyk (Citation2018), esp. 180–182.

7 I call Lithuania a ‘modern’ other in order to recognize the unusual nature of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, in which citizenship was broadly a function of class rather than ethnicity.

8 Many will recognize this archetypally Gothic character and plot, with its potential for feminist readings.

9 See for example, Babińska (Citation1993), 93.

10 Fudeman traces this insight to Jean Bellemin-Noël’s Vers l’inconscient du texte (Paris, PUF, 1979).

11 The spirit of Fudeman’s argument recalls another comment by Raitt, who had said that the patent deception throughout Mérimée’s work positively invites sceptical inquiry (Raitt Citation1970, 230).

12 In the first stage adaptation I have found, she becomes Russian (Esquier [Citation1906] 1907, 19).

13 Frost says that the Polish constitution of 3 May 1791 did away with the old class-based model of citizenship under the Commonwealth, replacing it with a revolutionary identity and nationality to be extended to all citizens (2005, 220). In his view, this enfranchisement was ironically its weakness, as it depended on the common peoples’ acceptance of it. The nobility, whose old Polish identity was dual (citizenship vs. ethnicity), rejected the idea of a new Polish state for class reasons, while a newly educated peasantry rejected it for newer reasons of Herderian cultural nationalism (ibid., 221–223). Such conflicts gesture towards ongoing debate concerning ‘instrumentalist’ versus ‘primordialist’ models of ethnic identity formation (Steen Citation2000, 70–71).

14 Biernacki notes that nobility from Greater Poland (Wiełkopolska) gosspied that Colonel Lachman, grandfather of Mérimée associate Maria Walewska and who had Courlander origins, was of ‘perhaps less Catholic origins’ (Biernacki Citation1969, 8–9).

15 ‘This “estate” comprised practically all citizens possessing all rights… In these conditions, the nobility was more than a class, it identified with the nation’.

16 ‘The concept of Poland, in its symbolic dimension, continued [in the 19th century], despite the country’s political disappearance, to designate the ill-defined territory of this at once easterly and northerly part of Europe’.

17 There are at least harmonic echoes of this point of view from within the social sciences, in Poland itself. ‘Poland, along with some other countries in the region, can be regarded as a transitional society from as far back as the late 18th century, if not for its entire history’ (Zarycki Citation2003, 101).

18 The drowning of Józef Poniatowski in the River Elster (1813) was just one such popular lithograph. Any one of several versions of it may have inspired Blazac (Guise Citation1976, 1302; cf. Balzac [Citation1842] Citation1976, 223).

19 See especially Jarry (Citation1896b), 336–337, as well as Jarry (Citation1896a), 130 and Jarry (Citation1896c), 342.

20 Rosset’s book (Citation1996) abounds with examples; see for instance pp. 79–80. For a discussion of Euro-Orientalism and the discourse of class, drawing particularly on French Revolutionary and romantic conceptions, see Adamovsky (Citation2005), especially pp. 617–619.

21 On Eastern Europe overall, Kołodziejczyk says that ‘pervasive orientalizing and modernizing discourses in Western social science “re-iterate a geo-epistemic boundary through which the region was re-created as a special island with its own laws”’ (Petrovici in Kołodziejczyk Citation2018, 180–181).

22 Their editorial acknowledges Elsaesser’s notion of ‘Europe’s vast borderlands having a constant double occupancy’ (Elsaesser in Mazierska, Kristensen, and Näripea Citation2014, 20–21).

23 Mazierska notes (Citation2016, 42) that in Polish film prior to 1939, a stereotypical plot was for a Russian man to fall in love with a highborn Polish woman, who would then reject him. This trope would harmonize with a dominant and longstanding perception of Russia as militarily superior but intellectually inferior to Poland. Quoth Balzac: ‘Disons en passant que la Pologne pouvait conquérir la Russie par l’influence de ses mœurs, au lieu de la combattre par ses armes…’ [‘let us say in passing that Poland could conquer Russia by the influence of its ways and values, in place of armed combat…’] ([1842] 1976, 196-97). Mazierska says that such images and themes would moreover conform to the commonplace of feminizing the colonial object (ibid.). Maria Janion notes that, contextually, Poland is fancied to have either feminine or masculine characteristics, depending on the object of comparison—Russia (the ‘man’), or Kresy nations such as Belarus (Citation2006, 326-27)

24 Mallion and Salomon allude fleetingly to another film attempt in 1926, ‘interdite par la censure allemande’ {‘forbidden by German censorship’} (Mallion and Salomon Citation1978, 1629). Biernacki mentions the Soviet film and ‘at least two adaptations since’, as well as three translations into Polish between 1918 and 1939 (1969, 8); Leopold Staff’s, for which he wrote the preface, can date only as late as 1957, when Staff died. Met (Citation2017) traces how Lokis inspired Walerian Borowczyk’s 1975 film La Bête, although he carefully underlines that Borowczyk’s film is a case of strong influence rather than adaptation.

25 Janicki’s catalogue of ‘fantastic’ film gives exhaustive coverage, at the price of almost any detail on a given title other than basic data and plot summary. Its entry on Lokis is strictly descriptive (cf. Janicki Citation1990, 233).

26 Pisula cites a well-known resolution from the Central Committee, of June 1960, which sets implicit yet menacing bounds for formal and generic experimentation: ‘Together with ideological movies, we should develop other genres, for instance, entertainment movies, comedies and dramas, to provide an ordinary audience with their interests; and it should not be primitive or in bad taste, and these films should not be devoid of social interest, according to the socialist spirit’ (Lubelski in Pisula Citation2016, 94).

27 ‘horror film in the Romanesque spirit’.

28 ‘Qualities of language and of execution that are often lacking in Polish films.’ Fuksiewicz describes Majewski overall as being ‘très soucieux de la forme’ (‘most concerned about form’) (Fuksiewicz Citation1989, 178).

29 Pisula’s three later examples are the crime/noir TV series 07 zgłoś się (1976–1987), the science fiction anthology series Opowieści niezwykłe (1967–1968), also on TV, and the Polish-Soviet film coproduction Test pilota Pirxa (1978), an adaptation from Stanisław Lem.

30 Specifically, Act I, scene ii, where Kordian takes out his pistol (Słowacki [Citation1834] 2018, 102–103).

31 ‘The film gives forth an accumulated local colour, which is also a question of vision or focus’.

32 I myself have made this mistake, mentioning it in a seminar hosted by Philippe Met, whence it made its way into his 2017 article. I apologise to Prof. Met and his readers for this confusion, and humbly direct them to this piece for a corrected reading.

33 I thank Dariusz Skórczewski for proposing this reading.

34 Of course the aristocracy had long been a target for the Communist authorities (Mazierska Citation2008, 191).

35 His mother was sequestered long before his maturity; and in any case, she is clearly the victim of Dr. Fröber, not of her son. These aspects are unchanged in the film.

36 The actual lines spoken in the film are: Hej, sowy, puchacze, kruki,/I my nie znajmy litości:/Szarpajmy jadło na sztuki,/A kiedy jadła nie stanie,/Szarpajmy ciało na sztuki,/Niechaj nagie świecą kóści. In Kraszewski’s version: ‘Now, ravens, fall we to the feast: Tear up each morsel, rip each piece, And when there’s no more bread or wine Slice off his flesh: let his bones shine!’ I thank Dorota Ostrowska for her help with this material.

37 Bakuła notes that the Kresy discourse ‘is only available to Poles’, with other ethnicities excluded (Citation2006, 14).

38 I thank Dariusz Skórczewski for alerting me to this.

39 Majewski, like most Polish directors, is not known for sympathetic approaches to homosexuality or homoeroticism (Mazierska Citation2008, 191). That said, we cannot rule out the possibility of a displaced, performance-based homoerotic appeal, comparable with that in Dracula (cf. Stoker [Citation1897] 1996, 58 passim; Ellmann Citation1996, xxiv, xxviii). Szemioth’s tree-climbing activities in the novella certainly seem to anticipate Dracula’s feats on his castle wall.

40 See for example Gibson Citation2006, 146 passim.

41 In my reading here of the ‘Polish national mind’, I draw a close analogy with Michael Kelly’s excellent reading of the cosmopolitan narcissist Alfred Jarry – itself guided by Zygmunt Bauman’s idea of cosmopolitan ambivalence: ‘While expressing a cosmopolitan aspiration to be expanded and as-yet-uncodified versions of belonging, particular individual cosmographies may also and at the same time be read as the aggrandizing and aggressive self-projection of an individual literary subject’ (Kelly Citation2013, 212, original emphasis). It is tempting to speculate that such subjectivity could be collective as well as individual, historic as well as literary. (Might a certain affinity have contributed to Jarry’s placement of King Ubu in Poland?)

References

- Adamovsky, Ezequiel. 2005. “Euro-Orientalism and the Making of the Concept Eastern Europe in France, 1810-1880.” The Journal of Modern History 77 (3): 591–628. https://doi.org/10.1086/497718.

- Althusser, Louis. 1965. Pour Marx. Paris: Maspero.

- Babińska, Teresa. 1993. “De Lokis de Mérimée.” Roczniki Humanistyczne 41 (5): 93–100.

- Bakuła, Bogusław. 2006. “Kolonialne i Postkolonialne Aspekty Polskiego Dyskursu Kresoznawczego (Zarys Problematyki) Teksty Drugie 6: 11–33. With thanks to Michał Romaniuk for a private translation.

- Balzac, Honoré de. 1842. 1976. “La Fausse Maîtresse.” Edited by René Guise, Pierre-Georges Castex. In La Comédie humaine II: Études de mœurs: Scènes de la vie privée. Paris: Pléiade-Gallimard, 195–243.

- Biernacki, Andrzej. 1969. ““Wprowadziene” [“Introduction”].” In Lokis. Rękopis Profesora Wittembacha. Edited by Mérimée. Translated by Leopold Staff [†1957], Warszawa: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1–21. As translated for the author by Dawid Czeczelewski.

- Caruth, Cathy. 1996. Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative, and History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Coates, Paul. 2005. The Red and the White: The Cinema of People’s Poland. London: Wallflower.

- Cropper, Cory. 2008. Playing at Monarchy: Sport as Metaphor in 19th Century France. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P.

- Devitt Tremblay, Maeve. 2018. Manifestations of Poland in Nineteenth-Century French Culture. DPhil. diss., University of Cambridge.

- Ellmann, Maud. 1996. “Introduction.” In Dracula. Edited by Bram Stoker. Oxford: Oxford University Press, vii-xxviii.

- Esquier, Léon Charles Stéphane. 1906. 1907. Lokis!… Paris: Georges Ondet.

- Forycki, Remigiusz. 2016. “Balzac en Pologne russe.” In France-Pologne. Contacts, échanges culturels, représentations (fin XVIè-fin XIXè siècle). Edited by Jarosław Dumanowski, Michel Figeac and Daniel Tollet. Paris: Honoré Champion, 335–347.

- Friedrich, Kaspar David. 1818. ca. Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer. Oil on canvas. Kunsthalle, Hamburg. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Der_Wanderer_%C3% BCber_dem_Nebelmeer#/media/File:Caspar_David_Friedrich_-_Wanderer_above_the_sea_ of_fog.jpg

- Frost, Robert. 2005. “Ordering the Kaleidoscope: The Construction of Identities in the Lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth since 1569.” In Power and the Nation in European History. Edited by Len Scales and Oliver Zimmer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 212–231.

- Fudeman, Kirsten. 2011. “Linguistic Science and Mystification in Prosper Mérimée’s ‘Lokis.” Nineteenth-Century French Studies 40 (1-2): 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1353/ncf.2011.0057.

- Fuksiewicz, Jacek. 1989. Le Cinéma polonais. Paris: Cerf.

- Garbicz, Adam. 1975. 1. “The Hourglass [Sanatorium Pod Klepsydrą]”. Film Quarterly 28 (3): 59–62. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.1975.28.3.04a00100.

- Gibson, Matthew. 2006. Dracula and the Eastern Question: British and French Vampire Narratives of the Nineteenth Century Near East. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Giżycki, Marcin. 2014. “Avant-Garde and the Thaw: Experimentation in Polish Cinema in the 1950s and 1960s.” In The Struggle for Form: Perspectives on Polish Avant-Garde Film, 1916-1989. Edited by Kamila Kuc and Michael O’Pray. Translated by Kamila Kuc. London: Wallflower, 83–92.

- Gosk, Hanna. 2008. “Polski Dyskurs Kresowy w Niefikcjonalnych Zapisach Międzywojennych. Próba Lektury w Perspektywie Postcolonial Studies.” Teksty Drugie 6: 20–33. With thanks to Michał Romaniuk for a private translation.

- Grzelecki, Stanisław. 1972. Polish Film. Warszawa: Ministry of Culture and Art.

- Guise, René. 1976. “Notes et variantes.” In La Fausse Maîtresse”, by Balzac. La Comédie humaine II: Études de mœurs: Scènes de la vie privée. Edited by Pierre-Georges Castex, 1284–1310. Paris: Pléiade-Gallimard.

- Haltof, Marek. 2002. Polish National Cinema. New York: Berghahn.

- Haltof, Marek. 2007. Historical Dictionary of Polish Cinema. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow.

- Hendrykowski, Marek. 1996. “Changing States in East Central Europe.” In The Oxford History of World Cinema. Edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 632–640, 1997.

- Iordanova, Diana. 2003. Cinema of the Other Europe: The Industry and Artistry of East Central European Film. London: Wallflower.

- Janicki, Stanisław. 1990. Polskie Filmy Fabularne 1902-1988. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Artystyczne i Filmowe.

- Janion, Maria. 2006. Niesamowita Słowiańszczyzna: Fantazmaty Literatury. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. With thanks to Michał Romaniuk for a private translation.

- Jarry, Alfred. 1896a. 1978. Ubu roi. In Ubu: Ubu roi, Ubu cocu, Ubu enchaîné, Ubu sur la butte. Edited by Noël Arnaud and Henri Bordillon. Paris: Gallimard, 27–132.

- Jarry, Alfred. 1896b. 1978. “Conférence prononcée à la création d’Ubu roi.” In Ubu., Edited by Arnaud and Bordillon, 340–342.

- Jarry, Alfred. 1896c. 1978. “Programme d’Ubu roi.” In Ubu. Edited by Arnaud and Bordillon, 336–339.

- Kelly, Michael. 2013. “Jarry, Stevenson and Cosmopolitan Ambivalence.” Comparative Critical Studies 10 (2): 199–218. https://doi.org/10.3366/ccs.2013.0088.

- Kiaupienė, Jūratė. 2001. “The Grand Duchy and the Grand Dukes of Lithuania in the Sixteenth Century: Reflections on the Lithuanian Political Nation and the Union of Lublin.” In The Polish- Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context, c. 1500-1795. Edited by Richard Butterwick. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 82–92.

- Kołodziejczyk, Dorota. 2018. “Comparative Posts Going Political—The Postcolonial Backlash in Poland.” In Postcolonial Europe: Comparative Reflections after the Empires. Edited by Lars Jensen, Julia Suárez-Krabbe, Christian Groes and Zoran Lee Pecic. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 177–191.

- Kraszewski, Charles. 2018. “Introduction: The Early Plays of Juliusz Słowacki.” In Four Plays: Mary Stuart, Kordian, Balladyna, Horstyński. Edited by Słowacki. London: Glagoslav, 7–28.

- Kristensen, Lars. 2016. “Wanna Be in the New York Times?’ Epic History and War City as Global Cinema.” In Contested Interpretations of the Past in Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian Film: Screen as Battlefield. Edited by Sander Brouwer. Leiden: Brill-Rodopi, 21–39.

- Lewandowski, Czeszław. 1990. “Dyskusja Prasowa Nad Koncepcją Inteligencji Polskiej J. Chałasińskiego w Latach 1946-1948.” Kwartalnik Historii Prasy Polskiej 29 (3-4): 71–101.

- Lowenstein, Adam. 2005. Shocking Representation: Historical Trauma, National Cinema, and the Modern Horror Film. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Majewski, Janusz. 1970. director “Lokis. Rękopis Profesora Witembacha.” performance by Józef Duriasz, Edmund Fetting, Tor: Poland, 100 minutes. In Horrory. Lokis/Wilczyca/Widziadło. Warszawa: Telewisja KinoPolska, 2011.

- Mallion, Jean, and Pierre Salomon. 1978. “Notice.” In Théâtre de Clara Gazul. Romans et nouvelles, by Prosper Mérimée, 1621-29. Paris: NRF-Gallimard.

- Mazierska, Ewa. 2008. Masculinities in Polish, Czech and Slovak Cinema: Black Peters and Men of Marble. New York: Berghahn.

- Mazierska, Ewa. 2011. European Cinema and Intertextuality: History, Memory, and Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mazierska, Ewa. 2016. “At War: Polish-Russian Relations in Recent Polish Films.” In Contested Interpretations of the Past in Polish, Russian, and Ukrainian Film: Screen as Battlefield. Edited by Sander Brouwer. Leiden: Brill-Rodopi, 41–57.

- Mazierska, Ewa., Lars Kristensen, Eva Näripea, et al. 2014. “Introduction: Postcolonial Theory and the Postcommunist World.” In Postcolonial Approaches to Eastern European Cinema: Portraying Neighbours On-Screen. Edited by Ewa Mazierska. London: I B Tauris, 1–39.

- Mérimée, Prosper. 1869. “Lokis.” In Théâtre de Clara Gazul. Romans et nouvelles. Edited by Jean Mallion and Pierre Salomon. Paris: NRF-Gallimard, 1049–1090.

- Met, Philippe. 2017. “Le Fantastique mériméen à l’écran: Lokis, de Majewski à Borowczyk”. Cahiers Mérimée 9: 147–169.

- Mickiewicz, Adam. 1823. Dziady [część II]. In Forefathers’ Eve. Translated by Charles Kraszewski. London: Glagoslav, 2016.

- Miłosz, Czesław. 1979. “Untitled Letter to Thomas Venclova. In “A Dialogue about a City.” In Forms of Hope. Edited by Thomas Venclova. Translated by M Ostafin. Riverdale-on-Hudson: Sheep Meadow, 1–18, 1999.

- Olszewski, Wojciech. 2006. “Identité, exclusivisme, cosmopolitisme. Commentaire anthropologique.” In Noblesse française et noblesse polonaise: Mémoire, identité, culture: XVIè—XXè siècles. Edited by Jarosław Dumanowski and Michel Figeac. Pessac: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme d’Aquitaine, 199–206.

- Ostrowska, Elżbieta, et al. 2016. “What Does Poland Want from Me?’ Male Hysteria in Andrzej Wajda’s War Trilogy.” In The Cinematic Bodies of Eastern Europe. Edited by Ewa Mazierska. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 31–52.

- Pisula, Radosław. 2016. “Suszyć, Skruszyć, Zmielić, Zważyć. Kino Gatunków a Filmy z Panem Kleksem.” Panoptikum 15 (22), 94–109. As translated for the author by Dawid Czeczelewski.

- Prizel, Ilya. 1998. National Identity and Foreign Policy: Nationalism and Leadership in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Raitt, Alan. 1970. Prosper Mérimée. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- Röger, Maren. 2013. “Narrating the Shoah in Poland: Post-1989 Movies about Polish-Jewish Relations in Times of German Extermination Politics.” In Iconic Turns: Nation and Religion in East European Cinema since 1989. Edited by Liliya Berezhnaya and Christian Schmitt. Leiden: Brill, 201–216.

- Rosset, François. 1996. L’Arbre de Cracovie: Le Mythe polonais dans la littérature française. Paris: Imago.

- Słowacki, Juliusz. 1834. “Kordian.” In Four Plays: Mary Stuart, Kordian, Balladyna, Horsztyński. Translated by Charles Kraszewski. London: Glagoslav, , 81–155, 2018.

- Snyder, Timothy. 2003. The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Sprenger, Scott. 2009. “Mérimée’s Literary Anthropology: Residual Sacrality and Marital Violence in ‘Lokis.” Anthropoetics: The Journal of Generative Anthropology 14 (2): 1–16.

- Steen, Anton. 2000. “Ethnic Relations, Elites and Democracy in the Baltic States.” The Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 16 (4): 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523270008415449.

- Stoker, Bram. 1897. [né Abraham] 1996. Dracula. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sverdiolas, Arūnas. 2006. “The Sieve and the Honeycomb: Features of Contemporary Lithuanian Cultural Time and Space.” In Baltic Postcolonialism. Edited by Violeta Kelertas. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 233–250.

- Taylor, Charles. 1992. “The Politics of Recognition.” In Multiculturalism: Examining the Politics of Recognition. Edited by Amy Gutmann, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 25–73.

- Venclova, Thomas. 1979. “Untitled Letter to Czesław Miłosz.” “A Dialogue about a City”. In Forms of Hope. Edited by Thomas Venclova. Translated by M. Ostafin. Riverdale-on-Hudson: Sheep Meadow, 19–40, 1999.

- Venuti, Lawrence. 2007. “Adaptation, Translation, Critique.” Journal of Visual Culture 6 (1): 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470412907075066.

- Wach, Margarete, et al. 2013. “Repreßion—Revolte—Regreßion: Historische Umbrüche und cineastische Emanzipazionsprozeße.” In Der polnische Film. Von seinen Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Edited by Konrad Klejsa,vol. 3. Marburg: Schüren, 258–290.

- Wajda, Andrzej. 1955. director. “Pokolenie [A Generation].” Performance by Tadeusz Łomnicki, Ursula Modrzyńska, KADR, Poland. 83 minutes.

- Wandycz, Piotr. 1974. The Lands of Partitioned Poland, 1795-1918. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Werner, Mateusz. 2007. New Polish Cinema. Warszawa: Adam Mickiewicz Institute.

- Youker, Timothy. 2015. “War and Peace and Ubu: Colonialism, the Exception, and Jarry’s Legacy.” Criticism 57(4): 533–556. https://doi.org/10.13110/criticism.57.4.0533.

- Zarycki, Tomasz. 2003. “Cultural Capital and the Political Role of the Intelligentsia in Poland.” Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 19 (4): 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523270300660030.

- Zwierzchowski, Piotr. 2020. “Archives and the Cinema of the PRL.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 11 (2): 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2020.1718419.