Abstract

The use of humour in sermons may seem incongruous, or distracting, since the traditional sermon’s function is seriously didactic. Nevertheless, and unusually perhaps for a ‘new’ minority Christian denomination whose members have a reputation for being ‘rather dour and pious’, there exists a strong tradition in the MormonFootnote1 Church for sermonic humour. Indeed, this tradition is officially sanctioned and modelled by Church leaders, who - regarded by the membership as modern-day prophets and apostles - thus lend the tradition ecclesiastical authority endorsement. This paper seeks to contribute to the emerging area of research into minorities and humour, by presenting the results of an analysis of Church leaders’ sermonic humour. To study one religious minority’s sermonic humour, is to add to our wider understanding of minorities’ humour practices, suggesting how they might intersect with each other in an increasingly multicultural-multireligious community such as the USA.

Keywords:

Introduction

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, an American institution for over 190 years, being what Leo Tolstoy reportedly called ‘the American religion’ (Brown Citation2014), is nevertheless, for the general public, ‘one of the world’s most misunderstood religious communities [known mostly for its] quirks and differences’ (Verghis Citation2019), despite comprising 2% of the US population, and being one of the US’s fastest growing religions (Cox Citation2019; Smith Citation2012; Pew Research Center Citation2014a; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2020). Research into Mormon humour is nascent, although distinctive Church doctrines and practices – including the abandoned practice of polygamy, and the belief in modern revealed scripture, such as the Book of Mormon, from which the Church’s nickname is derived – have long been the subjects of mainstream media, political and social satire (Cracroft Citation1971; Eliason Citation2000; Perry and Cronin Citation2012). This can be contrasted with the extensive humour-research literature into two comparably-sized religious-cultural minorities in the US: Jewish people, who constitute 2% and Muslim people, who number around 1% of the US population (DellaPergola Citation2019; Hale Citation2023; Pew Research Center Citation2014b).

From what little research exists, members of the Church are regarded as conservative in their humour tastes (McIntyre Citation2012, Citation2014). However, a growing demographic (perhaps 30%) is engaged with both mainstream and non-traditional, even ‘edgy’, media (Hale Citation2023) – which contradicts the public perception of the Church and its members as being conservative, isolationist, or ‘rather dour and pious’ (Wilson Citation1985, 8). Indeed, as the Church becomes more globalised and embraces new technologies, its ever-growing membership appears to have become less insular, more engaged with ‘the world’, and increasingly ‘liberal’ or progressive (Riess Citation2019). These demographic shifts are significant in themselves, but the membership’s receptiveness for humour suggests a Church-sanctioned attitude which features tolerance of satire directed against it, and which promotes formal and informal production of humour by its members - including sermonic humour modelling by Church leaders (Hale Citation2021a, Citation2021b) which members explicitly cite as being instrumental in their own sermonic humour (Hale Citation2023).

Church sermonic humour

The Oxford English Dictionary defines sermon as, ‘A discourse, usually delivered from a pulpit and based upon a text of Scripture, for the purpose of giving religious instruction or exhortation’ (Oxford English Dictionary Citation2022). This definition reflects the popular connotation of seriousness attached to the word ‘sermon’, although a substantial body of research has evidenced sermonic humour across various religious traditions (e.g. Hyers Citation2004; Cooper Citation2012; Gardner Citation2005; Afriani Citation2020).

The Church uses the term ‘sermon’ to refer to historical/scriptural discourses, and ‘talk’ is the term used for sermons delivered in local weekly services and conferences. ‘Talk’ reflects the more participatory culture of the Church, which has no professional preacher tradition, relying almost exclusively on an unpaid clergy (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2022c). While the upper leadership of the Church does receive a ‘living allowance’, they typically leave professional careers when they are ‘called into full time Church service’ (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2023). Consequently, although the Church’s globally-broadcast General Conferences feature leaders’ formal ‘talks’, these leaders are from diverse backgrounds, with individual styles, anecdotes and humour – features which, with varying degrees of success, many members, including children and teenagers, try to imitate in their assigned ‘talks’ during weekly services in local congregations around the world, but which are often disorganised or conversational in tone (Ladanye Citation1978).

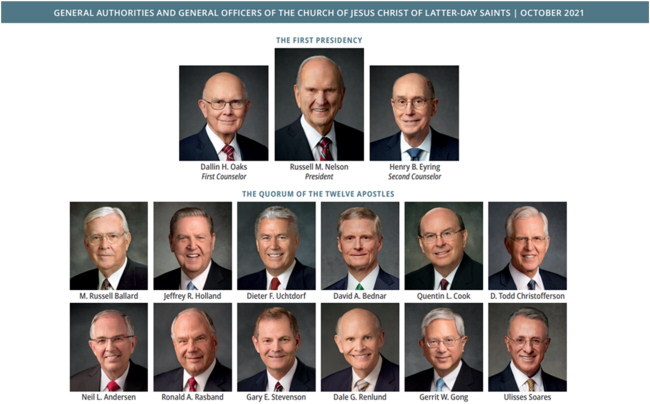

This ‘aspirational’ model of leadership ‘sermonising’, which is conducive for the practice of sermonic humour, reflects the Church’s highly centralised and hierarchical priesthood organisation. Leaders’ sermons entail authoritative doctrinal content and ‘appropriateness’ regardless of whatever personable styles they are presented with. Members ‘sustain’ their leaders in what is regarded as a restoration of Christ’s original Church, headed by the First Presidency—the prophet and two counsellors—and a Quorum of Twelve Apostles (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2021b; Appendix). Such a hierarchical structure generates ‘a highly centralized organization that emphasizes uniformity of doctrine and policies worldwide’ (Simmons Citation2017, 4), and thus any sermon delivered by an apostle or prophet is regarded as potentially having quasi-scriptural authority: ‘Whatever God’s servants speak when moved upon by the Holy Ghost shall be the voice of the Lord’ (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2010).

Therefore, Church leaders’ sermons are highly sought-after, for both instruction and for imitation, and this includes the use of sermonic humour, as evidenced by a recent study, which found that members value it, both at the local congregational level and from Church leaders, with the caveat that the humour must be appropriate and supportive of the message itself, seeing it as, ‘a phatic, or emotionally connecting device, informed by the understanding of what it was like to deliver a sermon themselves’ (Hale Citation2023, 17). This reinforces the idea that members are generally predisposed towards sermonic humour, but it suggests that members would have preferences for certain types of sermonic humour and that some leaders using sermonic humour would be more popular than others.

Church humour culture: modelling, production, and promotion of humour

Official doctrinal statements/publications explicitly support humour as a feature of membership and a healthy lifestyle. For example, in the Church’s family relationships resources kit, scripture - including Proverbs 17:22, ‘A merry heart doeth good like a medicine’ - is quoted to endorse humour as a ‘Gospel Truth’:

Good humor truly is medicine to the soul. Humor can ease tension, relieve uncomfortable or embarrassing situations, change attitudes, generate love and understanding, and add sparkle to life. A properly developed sense of humor is sensitive to others’ feelings and is flavored with kindness and understanding (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2022b).

The caveat ‘appropriately’ references a general Church injunction to avoid transgressive topics and language (McIntyre Citation2012; Oring Citation2017; Hale Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Nevertheless, a sizeable membership minority appears to ignore this injunction to ‘appropriate’ humour, since they enjoy creating and consuming humour which is highly suggestive, sometimes explicit, and frequently subversive of Church authority (Wilson Citation1985; Hale Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Hale Citation2023). Indeed, local ‘priesthood’ leaders (‘bishops’) and women’s leaders (‘Relief Society’ presidents) are particularly prominent as the targets of informally shared subversive/suggestive humour:

Perhaps the Church’s very strict sexual code makes the violation of the code the most effective way of deflating authority figures by making them…seem inferior or ridiculous…These sexual jokes may be one of the few socially acceptable ways of talking openly about this forbidden subject (Wilson Citation1985, 10–1).

Another area of humour promotion is the Church’s recent construction of historical narratives foregrounding the relatability of its prophets’ and apostles’ humour. For instance, the founding prophet, Joseph Smith, is described by the Church’s official historian as a religious leader who rebelled against his dominant Puritan background, viewing ‘humor and religion as quite reconcilable. As he saw it [besides] a core of life that is solemn, serious, and tender—there is still plenty of room for jesting’ (Arrington Citation1974). Similarly, Brigham Young, the second prophet of the Church, is depicted as a model of meeting ‘challenges with restraint and humor…[his] sense of humor endeared him to his followers and showed that he did not take himself too seriously’ (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2004). A famous example of a Church leader celebrated for his humour, is ‘the swearing apostle’, J. Golden Kimball, who appears in many folkloric stories, books, media (Kimball Citation1999, Citation2002; Eliason Citation2007; Eliason and Mould Citation2013; Gordan Citation2017) and even in contemporary apostolic sermons (e.g. Todd and Elder Citation2021) as a model of leadership because his swearing and irreverence help members, ‘laugh at their failures and foibles…to gain courage and strength to move on and overcome’ (Eliason Citation2007, 51).

Additionally, the Church is publicly regarded as being tolerant of satire directed against it by mainstream media – a surprising consequence of its often-uneasy relationship with wider US society (Cracroft Citation1971; Eliason Citation2000; Perry and Cronin Citation2012). This tolerance probably developed as a means of coping with historical, violent persecution (Perry and Cronin Citation2012; Givens Citation2013), and it is consistent with the Church’s fostering of humour in its own congregation as a means of encouraging Christian identity and resilience (Wilcox Citation2000; Eliason Citation2007). Its most unusual response came in 2011, when the creators of South Park staged their internationally successful musical comedy – The Book of Mormon. The musical’s provocative themes, crude language, and overt mockery of the Church and its scripture/doctrines were expected to draw a strong reaction (Trepanier and Newswander Citation2012; Burin Citation2017; Jones Citation2016), but the Church ‘responded with what commentators saw as a unique and good-natured official public relations/proselyting campaign, capitalising on the musical’s success’ (Hale Citation2021b, 186). Much of this response came in the form of humorous advertising, with lines such as, ‘You’ve seen the show, now read the book’ and ‘The book is always better’ (Cuthbertson Citation2015; Burin Citation2017). Officially, the Church signalled, through humour, that it was not offended, and it advocated for the freedom of humour to offend. Members’ feedback indicated an alignment with the Church’s position – indeed, many stated that being tolerant of mockery was an important feature of their membership and a moral good – with some respondents reporting that they had enjoyed the show (Hale Citation2021b).

The study: methodology

To test the notion that Church leaders perform sermonic humour for the membership in a public forum, an analysis of Church leaders’ sermons was performed. The most high-profile sermons occur at the Church’s General Conferences, held twice-yearly in April and October. These sermons are published on the Church’s website as transcripts and videos; the videos are also available on YouTube, and YouTube records the number of views - these view-numbers were used as the criterion for sermon popularity. So, while there are up to 6 sessions (a session is a 2-h meeting with multiple speakers) in each Conference, the most-viewed sessions were the 4 ‘open’ or general sessions. The other, less-popular sessions are the men-only (‘Priesthood’) or women-only (‘Relief Society’) meetings. The most-viewed period for Conferences was the 8 years between April 2022 (the cut-off date for the study) to April 2014. Before April 2014, views dropped to less than 1,000, presumably because these ‘historical’ sessions were loaded after live streaming began. This most-viewed period comprised a total of 16 Conferences, and 64 sessions. With an average of 6-8 speakers in each session, that represented a total of 450+ sermons for potential study.

To refine the dataset, only the 2-3 most popularly-viewed sermons in each session were selected for analysis, with the rationale that popularity might be an indicator of sermonic humour. Indeed, popularity was a major demarcating feature of sermons – there were widely fluctuating YouTube views between different sermons, even in the same session, and there were major differences between sessions in the same Conference. For instance, a Saturday Morning session sermon might attract views of 10,000, while the more popular Sunday Afternoon sermon could produce over 500,000 views. The most common number of views for selected sermons was between 30-40,000. Therefore, as a measure of recognition of popularity as an indicator, up to 4 speakers/sermons were selected from the most popular sessions, while 2 speakers/sermons were selected from the least popular sessions. This data refinement rendered a final corpus of 178 sermons for analysis, and had two major benefits: it rendered a more representative sample, and it provided a more manageable dataset. This was important, since analysis consisted of viewing every sermon in conjunction with every transcript, identifying every act of sermonic humour and analysing each humour act for audience reception and style/features. The average sermon lasts between 10-15 min (remarkably uniform in length), and the transcript is typically around 3,200 words. This rendered a dataset of 2,136 min (or 35.5 h) and 569,600 words.

The analysis identified textual incidents of humour, and the YouTube video was checked for the presence of audience laughter, to indicate a successful act of humour, with the corresponding percentage of laughter incidence recorded for each speaker. Further tabulations were then generated (see ):

Table 1. Summary of Q15 preachers, sermons, and incidence/types of humour.

Incidence of humour total: total humour acts in all sermons per speaker.

Number of sermons: total sermons for each speaker.

Number of sermons with humour: total sermons where at least one act of humour occurred.

Number of sermons without humour: total sermons with no acts of humour.

Average humour acts per sermon: total humour acts divided by the total number of sermons per speaker.

Rate of sermonic humour for all sermons as %: total sermons containing humour, divided by the total sermons, rendered as a percentage.

Jokes per sermon when doing humour: total humour acts, divided by the total of sermons where humour occurred (rounded).

Acts of humour were then categorised according to the target of the joke, following Gruner’s (Citation2000) formulation of humour as a social action with a target. Identified targets were: the audience; self-aggrandisement or self-effacement for the speaker; a 3rd party, (named/unnamed); other religions; Church scripture or sacred beliefs; secular society; intrinsic characteristics of people, such as gender, age, or race; and Mormon culture. These results were then tabulated with the sermonic humour results (, below). Examples of this identification-analysis appear below, including where some targets were duplicated:

Simple humour act: Nelson (April 2022, Sunday Morning Session)

Satan delights in your misery. Cut it short.

Targets: sacred beliefs (Satan), named 3rd party (Satan), audience (your misery/cut it short).

Complex humour act: Holland (April 2017 Saturday Afternoon Session)

Targets: combined targets are self-effacement (Many of us/musically challenged), and inferentially-deictically the audience (Many of us/musically challenged), along with unnamed 3rd parties (two remarkable Latter-day Saint women), Mormon culture (All God’s critters got a place in the choir), sacred beliefs (God).

After tabulation, further analysis was performed, including finding patterns of targeting to define each speaker’s sermonic humour style and strategies. So, for instance, self-effacement and Mormon culture were regarded as ‘internal’ targets designed to build audience rapport, while self-aggrandisement and gender were considered as targets ‘external’ to the speaker, generating audience distance.

Findings and discussion

There are two main findings. Firstly, while humour was practised by around half of all speakers, one group of speakers dominated for ecclesiastical seniority, highest number of sermons, most acts of sermonic humour, and overall popularity. Secondly, while there were clear commonalities for targets across all speakers, three speakers from within this dominant group were distinguishable by their specific choices of targets, and very personal styles of humour; they are categorised as the ‘top 3′ speakers.

Overall, across all speakers and sermons, humour occurred at the average of 52%; i.e. around half of all sermons contained jokes. However, the rate of jokes per speaker was markedly higher for speakers who were more senior in ecclesiastical authority, such that it was possible to divide all speakers into two distinct groups where performance of sermonic humour was aligned with positions in the Church’s hierarchy. The ‘lower’ group (Group 2 or G2) comprised persons from outside the top 2 tiers of Church organisation and priesthood authority. These persons are drawn from the lower tiers of Church organisation, e.g. ‘the Seventy’, the ‘Relief Society’, or the ‘Presiding Bishopric’. Only one woman (whose 1 sermon contained 1 joke) was represented - this reflects the minority of women in the Church’s higher organisation levels and the fact that female speakers were not popular as measured by YouTube views. By contrast, the ‘higher’ group (Group 1 or G1) comprised men from the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, collectively known as the Q15 (Q = quorums, 15 = the number of individuals).

The G2 comprised 18 unique speakers, with a total of 21 sermons, or an average of (rounded) 1 sermon each. Of these 21 sermons, 12 contained humour acts. This rate of 57% humour act incidence was higher than G1’s, but G2’s production of humour acts per speaker was much lower (0.68 as opposed to 1.5). Both groups had consistently similar humour targets: Mormon culture, self-effacement, secular society, scripture/sacred topics, and 3rd party targets (both named/unnamed). Moreover, both groups rarely targeted self-aggrandisement or intrinsic characteristics. There were some notable exceptions to this general rule (amongst the ‘top 3′ speakers in G1), and this will be considered separately. This overall consistency between G1 and G2 is interpreted as G2 being highly imitative of G1’s sermonic humour style. Both groups offer sermons in the same sessions, so there is a likelihood that G2’s sermonic humour style is motivated by conformative pressure – generated by a consciousness of their lower status, and an awareness that their sermons are not received with the same authoritative weight as G1 speakers, whose sermons are more likely to represent the ‘voice of the Lord’ (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2010). Therefore, because of the ‘derivative’ nature of G2 sermonic humour, G1’s more influential modelling of sermonic humour is the focus of this study.

G1 speakers were the most-viewed, they spoke multiple times in each Conference, and they ‘headlined’ every session. Thus, while comprising only 16 unique speakers (including one Q15 member who deceased and was replaced in the period studied), there were 158 sermons preached, or an average of (rounded up) 10 sermons each. Humour acts occurred in 75 (i.e. 48%) of all sermons, but there were 238 humour acts overall. This means that the humour rate per speaker was 1.5 (i.e. more than twice the rate for G2 speakers). It also means that the number of jokes per sermon where humour occurred was 3.17. At first glance, this suggests that G1 was a group characterised by more productivity in sermonic humour, and this probably reflects their higher status, greater experience, confidence in preaching, and perhaps a consciousness of prophetically/apostolically representing the Church’s ‘brand’ through relatable/affable sermonic humour.

Nevertheless, there were identifiable disparities within the G1: 11 of the 16 speakers were minor contributors of humour, e.g. one speaker did not contribute humour at all, 4 contributed one humour act each, and the other 6 contributed between 3-8 humour acts each. This means that only 5 speakers were the most prolific for humour acts, and 2 of these were the most dominant: Holland, with 74 humour acts, and Uchtdorf, with 51, while Nelson produced 28, Bednar, 20, and Eyring, 18. Interestingly, the most prolific humour producers were also the most popular speakers overall, and they were amongst the most senior Apostles (Holland, with 18 sermons; Uchtdorf, 17; Bednar and Eyring, with 15 each), and the current Prophet (Nelson, 29). While Oaks (popular, with 16 sermons) and Ballard (not as popular, with 3 sermons) were also senior Apostles, they were not prominent in the production of sermonic humour, so this concentrated the production of sermonic humour even more amongst the ‘top 5′ apostles/prophet.

To determine if this was merely a reflection of Church status and/or being the most frequent speakers in Conference, several cross-measurements were applied. Setting aside the incidence of humour for speakers who performed high levels of humour acts, but who delivered 6 sermons or less, as being less ‘consequential’ (e.g. Stevenson, with 2 sermons, or Gong, with 3), it was found that these same 5 prominent apostles/prophet were also performing humour at not only an absolute greater number, but also at an average and proportionate rate much greater than others. So, for instance, Holland (average 4.1 and rate of 78%) and Uchtdorf (3 and 94%) were the ‘top performers’ of humour, followed by Eyring (1.2 and 53%), Nelson (.96 and 45%) and Bednar (1.3 and 40%). By contrast, Oaks (.38 and 19%) was performing at a lower average and rate than others such as Christofferson, who with 10 sermons (0.8 and 38%), was the highest-ranked of the less-popular speakers.

Next, the ‘top-performing’ 5 speakers’ targets of humour were analysed. Data from were used to establish a pattern of targets/style of humour. Of these 5 speakers, 3 dominated for deployment of targets overall, as shown in (below), and these 3 speakers are termed the ‘top 3′:

Table 2. Deployment of targets by highest-rated 3 speakers.

While these top 3 speakers’ targets were consistent with other G1 and G2 speakers’ targets, there were many choices which demonstrated a highly personal sermonic humour style. For instance, Uchtdorf (34 instances) and Nelson (17) together accounted for 63% of all self-effacement, while Holland contributed only 7. By contrast, Holland produced almost all the self-aggrandisement targets (14 out of 17 total), while Uchtdorf and Nelson completely avoided this target. Similarly, Holland targeted the audience more than all the rest of the apostles/prophet combined (62% of all instances), and targeted secular society and Mormon culture more than any other speaker. Interestingly, Holland, Uchtdorf and Nelson targeted scripture/sacred in roughly even measure.

However, there were significant stylistic differences, even when targeting the same topic. So, while Uchtdorf was second to Holland in targeting secular society and Mormon culture, his jokes linked these targets to himself through self-effacement. For example (April 2018 Sunday Afternoon Session), Uchtdorf linked secular society (the internet) to self-effacement when satirising his own sermonic style (he frequently references his former occupation as an airline pilot): Recently I asked the internet, ‘What day most changed the course of history?’ The responses ranged from surprising and strange [including] of course, the day in 1903 when the Wright brothers showed the world that man really can fly.

By contrast, Holland typically links targets to self-aggrandisement, rarely using self-effacement. For example (from the same session), when targeting Mormon culture and audience, he chastises members for not performing their ministering responsibilities properly: …the sorry statement I recently saw on an automobile bumper sticker…read, ‘If I honk, you’ve been [ministered to]’. Please, please, brethren. The self-aggrandisement occurs because he (as a senior leader receiving a ‘living allowance’), is inferentially asserting that the membership (performing unpaid volunteer ministry) should emulate his service.

These target patterns suggest either an other-directed focus or a self-directed focus underlying each speaker’s personal sermonic humour style, which can be categorised binarily as either ‘external’ targets, meaning topics beyond self at the service of self-aggrandisement, or as ‘internal’ targets, meaning topics primarily targeting self and personally-held/cherished beliefs and ideas, and which constitute self-effacement. As indicated by the audience laughter, both types can build speaker-audience rapport, but the internal targets can be regarded as positive, in that the speaker produces humour at their own expense, whereas external targets typically identify an external ‘threat’ or ‘problem’. Internal targets tend to make the speaker more vulnerable, and perhaps more relatable, whereas external targets tend to build the speaker’s status and authority at the expense of whatever person or entity is referred to.

This can be a little more complex than it appears; contextual function, or intention must also be considered. For instance, Mormon culture is primarily an internal target, because the speakers are satirising shared cultural/identity practices, and the audience must agree that these are legitimate targets. Thus, Mormon culture is understood as being removed from the ‘divine’, representing instead a shared/relatable flawed human behaviour. Interestingly, its potential rapport/appeal is reflected in it being the most-deployed target: 127 times across all 3 speakers, with Holland deploying it most frequently – he also tends to target Mormon culture as something external to himself, while Uchtdorf and Nelson use it to stress their own shared ‘human weakness’. For instance, Nelson (April 2019 Sunday Morning Session) juxtaposed secular society and scripture/sacred topics through a mundane place name: Actually, my wife and I visited Paradise earlier this year. Paradise, California, that is. The deliberately ambiguous reference to visiting ‘Paradise’ (i.e. ‘heaven’), then clarifying it as the earthly location, was a joke which relied on shared background knowledge for its effect. The joke deployed self-effacement and built audience rapport; Nelson at the time was 94 years old, so the joke references his own frail mortality, but also implies that he, even as the Prophet, was not yet ‘worthy’ of, or ready for, heaven.

By contrast, Holland (April 2019 Saturday Afternoon Session) when referencing Christ’s utterance (Luke 14:5), links scripture/sacred, Mormon culture and audience targets into a self-aggrandisement or external function, by joking about members’ excuses for Sabbath non-observance: …if the ox is in the mire every Sunday, then we strongly recommend that you sell the ox or fill the mire. The joke links the scripture/sacred reference to a common excuse used by members (i.e. representing Mormon culture) for non-Sabbath observance, and so the real target is the audience’s lack of piety. This constitutes self-aggrandisement because Holland invokes his stipended, Apostolic authority to reprimand ‘less-than-pious’ volunteer ministry members who are the joke’s target.

Nevertheless, while there are clear individual sermonic humour styles, there are also clear commonalities; despite some humour styles being more ‘aggressive’ than others, Church leaders on the whole employ ‘safe’ humour. Offensive language is absent and sensitive topics are typically not satirised. The only exception to this general pattern was Holland, who joked about sensitive topics such as other religions, gender, age, and race. For instance, Holland targeted race followed a sermon delivered in Spanish by a non-Q15 speaker (October 2014, Saturday Afternoon Session). Holland ‘congratulated’ - in a language he does not speak - the previous speaker by saying, Bien hecho, Eduardo. Audience laughter accompanied the ‘congratulatory’ Spanish-language phrase, but the potential for offence amongst the Church’s second-largest language group (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2021a) was immense, since the ‘joke’ could be interpreted as condescending, even if Holland’s purpose was self-effacing.

Similarly, Holland targeted gender (April 2019 Saturday Afternoon Session) when saying: … a late pass will always be lovingly granted to those blessed mothers who, with children and Cheerios and diaper bags trailing in marvelous disarray, are lucky to have made it to church at all. Presumably, the intention was rapport-building, but the prescriptive gender-role frame of this joke simultaneously has an external, othering function, which seems outdated/sexist for a membership which is increasingly progressive and diverse (Riess Citation2019). By contrast, Uchtdorf deployed a very subversive gender target (October 2015 Saturday Morning Session): Tell a man there are trillions of stars in the universe, and he’ll believe you. Tell him there’s wet paint on the wall, and he’ll touch it just to be sure. While ‘man’ can be seen as a generic referent, it is also gendered, and Uchtdorf as a senior member of the Q15 is deliberately - if subtly – being self-effacing, and thus subverting the Church’s hierarchical patriarchy.

Another sensitive target was age, where Holland again dominated. For example, he targeted his ecclesiastical superior, the Prophet (Saturday Morning Session 2022 April): I direct my remarks today to the young people of the Church, meaning anyone President Russell M. Nelson’s age or younger (at that time, Nelson was 97, while Holland was 81). While this joke might be seen as unexceptional ‘teasing’ of a close colleague, it should also be contextualised within Holland’s sermonic style of one-sided external targeted humour; Nelson never targeted Holland, while Holland’s targets were almost invariably someone or something else. Another example of this ‘teasing’ was his non-reciprocal targeting of Q15 colleagues with baldness (October 2020 Sunday Afternoon Session): We are so tired of this contagion, we feel like tearing our hair out. And apparently, some of my Brethren have already taken that course of action. As someone who does not suffer from baldness, and as one of the most senior Church leaders, Holland’s targeting of others’ intrinsic characteristics seems to be insensitive at best, and an act of aggression or power imbalance at worst.

This contrasts with Uchtdorf’s characteristically self-effacement style. For instance, Uchtdorf discussed a personal health issue with a sequence of 3 self-deprecatory jokes (October 2015 Saturday Morning Session): as a patient, I’m not very patient…I decided to expedite the healing process by undertaking my own Internet search…I suppose I expected to discover truth of which my doctors were unaware or had tried to keep from me. He also regularly jokes about his German-accented English/background: e.g. (October 2014 Saturday Morning Session) Some asked me if would speak in German. I said no, but it might sound like it. When discussing the decision to ‘rebrand’ volunteer Church service as ‘ministering’ (October 2018 Saturday Afternoon Session), he commented: One of the names considered was shepherding…However…using that term would make me a German shepherd.

Nelson also extensively used self-effacement, despite his previous high international status as a famous surgeon/medical scientist (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Citation2022a), and current ecclesiastical status as head of the Church. Indeed, his humour often relates to self-doubt and challenges of faith, e.g. he candidly reported that prayers and faith could not always prevent rain: [we] sat through a very wet two-hour meeting (April 2021 Sunday Morning Session), and he confessed to an early career crisis when he lost a patient, expressing gratitude for his wife’s blunt but efficacious advice (October 2015 Sunday Morning Session): [she] looked at me and lovingly asked, ‘Are you finished crying? Then get dressed!’

Conclusion

This paper investigated Mormon leaders’ sermonic humour delivered during the Church’s General Conferences over a period of 8 years (2014-22), finding that sermonic humour was welcomed by members, as measured by popularity of YouTube views. Additionally, sermonic humour functioned as a significant model of ‘appropriateness’ in the context of a Church doctrine/culture which promotes humour production and consumption as part of a healthy, moral lifestyle. Related to this finding was the fact that the most popular Conference speakers were senior Church leaders who consistently used sermonic humour, with 3 of the most senior leaders dominating overall. While there were many commonalities across all speakers, there were also discernible individualistic sermonic humour styles, especially amongst the ‘top 3′ speakers (Nelson, Holland and Uchtdorf), who diverged widely in target choices. Thus, the symbolic act of leaders’ sermonic humour – and with the freedom to express personality - in such a prominent public religious setting seems to be a key finding.

Several features of this sermonic humour were noted. Consistent with the limited research extant on this topic, language, topics, and humour choices were clearly pre-planned and ‘safe’. Controversial topics were not satirised, nor was sexualised/offensive language used. Further, there was a strong focus on ‘internal’ targets: self-effacement, Mormon culture and scripture/sacred. These targets are ‘internal’ because they rely on shared knowledge and identity, and a willingness to laugh at the speaker’s/members’ human failings - especially when contrasted with divine/scriptural models of moral behaviour. Additionally, it was rare to find any targeting of ‘external’ topics such as secular society, other religions, gender, age, or race, while references to 3rd party targets were typically benign or generic, and self-aggrandisement was unusual. Most surprising, given the traditional/popular understanding of sermons as being serious, and didactic, was the frequent juxtaposition of scripture/sacred references with the targeted mundane/cultural behaviour of members for the purposes of humour.

Indeed, this ‘irreverent’ feature of sermonic humour was quite popular with both speakers and members. It signifies a good-natured willingness to laugh at themselves, and this probably contributes to, and is a product of, the Church’s culture of tolerance towards satire directed against it. What might once have been a ‘coping mechanism’ against mockery and persecution, and/or a product of doctrinal injunction for moral/spiritual health, seems to now be well-established as a distinctive feature of Mormons’ cultural/spiritual lives. The fact that Church leaders lead their congregation in the use of sermonic humour probably fosters a modelling effect in local congregations globally.

However much the practice of sermonic humour is distinctive to the Mormon faith is a matter of future research that would involve comparative studies with other religious traditions. Additionally, an attitudinal study is proposed with a large sample of Mormon members and leaders to determine how widespread this cultural practice is, and whether it is popularly endorsed as a matter of religiosity. Ideally, further research would also examine sermonic humour through the frames of membership demographics, i.e. the reception of apostolic/prophetic ‘joking’ by members according to gender, age, ethnicity, language background, and orientation. This seems especially relevant, given the fact that the Church’s leadership, its General Conferences, and its ‘approved’ sermonic humour, are dominated by a cisgendered, straight, male priesthood hierarchy from which the voices of others, including women, are absent.

Additionally, this paper, which focuses on an 8-year period of high-profile sermonic humour, suggests that more research is needed into explaining how this particular Church model of humour developed. If, as already noted, the Church responded to historic persecution and public ridicule by adopting a stance of tolerance and passivity, it prompts the question of how this relates to other Christian humour/tolerance traditions, or how it contrasts with religious traditions which do not easily tolerate ridicule. This broader contextual examination can not only help us understand the Mormon religious community, but also intersections of humour practice between the religious and non-religious. Such research, it is argued, is essential in building social bridges of rapport and understanding between communities of faith and communities of the non-religious. This paper argues that a minority religious community which can laugh at themselves – even, or especially, when derided by the majority – represents a model of self-confidence and maturity as ‘good neighbours’ from which we can all benefit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The original data-working set can be made available on request through an email to the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Adrian Hale

Adrian Hale (PhD) is a Senior Lecturer at Western Sydney University, Australia. His research and teaching areas are: Linguistics, Academic English, Discourse Analysis, Linguistic Studies of Humour, and Mormon Studies, especially for Humour, LBGQT + and Policy.

Notes

1 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is more commonly known as the Mormon Church, or the LDS Church. For brevity, and because of the Church’s officially stated preference, this paper uses ‘the Church’ in most instances.

References

- Afriani, Susi H. 2020. “Illuminating Distinctive Cultural-Linguistic Practices in Palembangnese Humour and Directives in Indonesia.” Global Media Journal: Australian Edition 14 (1) https://www.hca.westernsydney.edu.au/gmjau/?p=3819

- Arrington, Leonard J. 1974. “The Looseness of Zion: Joseph Smith and the Lighter View.” BYU Speeches, November 19. https://speeches.byu.edu/talks/leonard-j-arrington/looseness-zion-joseph-smith-lighter-view/

- Astle, Randy, and Gideon O. Burton. 2007. “A History of Mormon Cinema.” BYU Studies Quarterly 46 (2): 12–21. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol46/iss2/2/

- Bennett, Jeanette W. 2004. “2 Funny Guys Show Quirky LDS Culture on The Big Screen.” UtahValley360, January 1. https://utahvalley360.com/2004/01/01/2-funny-guys-show-quirky-lds-culture-on-the-big-screen/

- Bennett, Jim. 2014. “What happened to the wave of Mormon movies?” Deseret News, April 25. https://www.deseret.com/2014/4/25/20540085/what-happened-to-the-wave-of-mormon-movies

- Brown, Keith L. 2014. “Leo Tolstoy: Mormonism as the ‘American Religion’.” History of Mormonism, September 30. https://historyofmormonism.com/2014/09/30/leo-tolstoy-mormonism-american-religion/

- Burin, Margaret. 2017. “What real Australian Mormons think about The Book of Mormon musical.” ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-04/what-real-mormons-think-about-the-book-of-mormon-musical/8239188

- BYU Broadcasting. 2022. “Studio C: Clean Comedy.” BYU Broadcasting. https://www.byutv.org/studioc

- Todd, Christofferson, and D. Elder. 2021. “Why the Covenant Path.” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2021/04/54christofferson?lang=eng

- Cooper, D. J. 2012. “Religion and humor.” Santa Barbara: University of California. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1237250057?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Cox, Daniel. 2019. “Most churches are losing members fast—but not the Mormons. Here’s why.” Vox, March 6. https://www.vox.com/identities/2019/3/6/18252231/mormons-mormonism-church-of-latter-day-saints

- Cracroft, Richard H. 1971. “The Gentle Blasphemer: Mark Twain, Holy Scripture, and the Book of Mormon.” BYU Studies Quarterly 11 (2): 119–140. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol11/iss2/2.

- Cuthbertson, Debbie. 2015. “South Park creators‘Trey Parker and Matt Stone‘s Broadway hit The Book of Mormon to open in Melbourne.” The Sydney Morning Herald, April 27. http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/musicals/south-park-creators-trey-parker-and-matt-stones-broadway-hit-the-book-of-mormon-to-open-in-melbourne-20150427-1mu5h5.html

- DellaPergola, Sergio. 2019. “World Jewish Population, 2018.” In American Jewish Year Book edited by A. Dashefsky, and I. Sheskin, 361–449. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03907-3_8

- Eliason, Eric, and Tom Mould. 2013. Latter Day Lore: Mormon Folklore Studies. Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press.

- Eliason, Eric. 2007. The J. Golden Kimball Stories. Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Eliason, Eric A. 2000. “Mark Twain, Polygamy, and the Origin of an American Motif.” Mark Twain Journal 38 (1): 2–6.

- Fandom n.d. Super Best Friends. https://southpark.fandom.com/wiki/Super_Best_Friends

- Gardner, R. 2005. “Humor and Religion: An Overview.” In Encyclopedia of Religion, 2nd ed., 4194–4205. Detroit, MI: Macmillan reference USA (Thomson Gale).

- Givens, Terryl. 2013. The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University.

- Gordan, Kathryn Jenkins. 2017. “4 Surprising Facts About the “Swearing Apostle” J. Golden Kimball.” LDS Living, June 2. https://www.ldsliving.com/4-surprising-facts-about-the-swearing-apostle-j-golden-kimball/s/85516

- Gruner, Charles R. 2000. The Game of Humour: A Comprehensive Theory of Why we Laugh. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Hale, Adrian. 2021a. “Do Mormons Think the Book of Mormon is Funny?” HUMOR 34 (4): 659–677. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2020-0134

- Hale, Adrian. 2021b. “Mormon Reactions to the Book of Mormon.” Comedy Studies 12 (2): 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/2040610X.2021.1893469

- Hale, Adrian. 2023. “What Makes Mormons Laugh.” HUMOR 36 (3): 463–486. https://doi.org/10.1515/humor-2022-0018

- Hess, Jared. 2004. Napoleon Dynamite. Fox Searchlight Pictures.

- Hyers, Conrad. 2004. The Laughing Buddha: Zen and the Comic Spirit. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

- Jones, M. 2016. “How the LDS Church’s Response to ‘The Book of Mormon’ Musical is Actually Working.” Deseret News, November 16. https://www.deseretnews.com/article/865667313/How-the-LDS-Churchs-response-to-The-Book-of-Mormon-musical-is-actually-working.html

- Kimball, James. 1999. J. Golden Kimball Stories. Salt Lake City, UT: Whitehorse Press.

- Kimball, James. 2002. More J. Golden Kimball Stories. Salt Lake City, UT: Whitehorse Press.

- Ladanye, Thomas W. 1978. “The Six Best Talks I Ever Heard.” Ensign, November. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/1978/01/the-six-best-talks-i-ever-heard?lang=eng

- McIntyre, Elisha. 2012. “Knock Knocking on Heaven’s Door: Humour and Religion in Mormon Comedy.” In Handbook of New Religions and Cultural Production, 71–97. Leiden: Brill.

- McIntyre, Elisha. 2014. “God’s Comics: Religious Humour in Contemporary Evangelical Christian and Mormon Comedy.” Unpublished PhD. Thesis. Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Sydney.

- Olson, Bradley. 2017. “A Comedy Show Thrives by Avoiding Vulgarities–Such as the Word ‘Gosh’.” The Wall Street Journal, October 18. https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-comedy-show-thrives-by-avoiding-vulgaritiessuch-as-the-word-gosh-1508342560

- Oring, E. 2017. “The Consolations of Humor.” The European Journal of Humour Research 5 (4): 56–66. https://doi.org/10.7592/EJHR2017.5.4.oring

- Oxford English Dictionary. 2022. “Sermon.” https://www-oed-com.ezproxy.uws.edu.au/view/Entry/176489?rskey=WicJRo&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid

- Perry, Luke, and Christopher Cronin. 2012. Mormons in American Politics: From Persecution to Power. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

- Pew Research Center. 2014a. The Religious Landscape Study: Mormons. https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/religious-tradition/mormon/

- Pew Research Center. 2014b. The Religious Landscape Study. https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/

- Riess, Jana. 2019. The Next Mormons: How Millennials Are Changing the LDS Church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Simmons, Brian William. 2017. “Coming out Mormon: An Examination of Religious Orientation, Spiritual Trauma, and PTSD among Mormon and ex-Mormon LGBTQ + QA Adults.” PhD diss., University of Georgia.

- Smith, G. 2012. “Mormons in America: Certain in Their Beliefs, Uncertain of Their Place in Society.” The Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. Washington, DC: The Pew Centre for Research.

- Sunstone. Sunstone. 2020. About Us. Magazine. https://www.sunstonemagazine.com/about/

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2004. “Presidents of the Church Student Manual: Chapter 2: Brigham Young.” https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/manual/presidents-of-the-church-student-manual/chapter-2?lang=eng#d

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2010. New Era, August. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/new-era/2010/08/doctrine-and-covenants-1-38?lang=eng

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2021a. President Nelson Launches Personal Instagram Account in Spanish. https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/article/president-nelson-launches-personal-instagram-account-in-spanish

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2021b. Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/learn/quorum-of-the-twelve-apostles?lang=eng.

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2022a. Russell M. Nelson. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/learn/russell-m-nelson?lang=eng

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2022b. Sense of Humor. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/family-home-evening-resource-book/lesson-ideas/sense-of-humor?lang=eng

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2022c. Sunday Services. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/comeuntochrist/belong/sunday-services/what-are-sunday-services-like

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2023. Do General Authorities get paid?. https://faq.churchofjesuschrist.org/do-general-authorities-get-paid

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. 2020. Facts and Statistics: United States. https://newsroom.churchofjesuschrist.org/facts-and-statistics/country/united-states

- Trepanier, Lee, and Lynita K. Newswander. 2012. LDS in the USA: Mormonism and the Making of American Culture. Waco: Baylor University Press.

- Verghis, Sharon. 2019. “All your questions about Mormonism, answered.” SBS.com.au, March 25. https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/voices/culture/article/2019/03/25/all-your-questions-about-mormonism-answered

- Walker, David. 2017. “Mormon Melodrama and the Syndication of Satire, from Brigham Young (1940) to South Park (2003).” The Journal of American Culture 40 (3): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacc.12741

- Wilcox, Brad. 2000. “If We Can Laugh at It, We Can Live with It.” Ensign. March https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/2000/03/if-we-can-laugh-at-it-we-can-live-with-it?lang=eng

- Wilson, William A. 1985. “The Seriousness of Mormon Humor.” Sunstone 10: 6–13.

Appendix

Ranking of the Church’s top 2 tiers of leadership, known as the Q15 (at October, 2021).

Image credit: https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/learn/global-leadership-of-the-church?lang=eng