Abstract

This article combines the insights of an academic and a professional comedian, Paul Merton, in exploring how players attempt to mitigate cognitive overload or ‘brain fry’ in the popular BBC radio panel game Just a Minute (JaM). JaM requires players to present one minute of entertaining fluent spoken narrative on a specified subject, in front of a live audience. However, they have to navigate three rules: not to hesitate, repeat or deviate. These constraints impede the strategies that speakers customarily use to sustain fluency. They also undermine some of the classic tools of comedy. With reference to the role of fluency in regular speech, and how risks to fluency are usually mitigated by speakers, we show why the game’s rules build such a cognitive burden. We explore the various tactics of players for managing that burden so that they avoid brain fry, and we draw in particular on the approach taken by the co-author, a regular and successful player for over 35 years. His solution to the challenge of cognitive overload is to reframe the purpose of the game. This article is the first to offer a theory-based account of the mechanisms of this internationally popular game show.

1. Introduction

Just a Minute is a text-book example of a successful radio format, with approaching sixty years of broadcast history on the BBC. In this article, an academic and a professional comedian, Paul Merton (PM)—who has regularly appeared on JaM since 1988—collaborate to examine the programme’s winning combination of tension and humour. Of particular interest to us is the inherent risk that players will experience cognitive overload, or ‘brain fry’, as they attempt to sustain fluent narrative without hesitating, repeating themselves or deviating—all outlawed in the rules of the game. We show what makes the game so cognitively challenging and how the challenge is navigated by different players.

We begin by introducing the Just a Minute format, rules and character. In Section 2, we explore the nature of fluency in regular spoken narrative, and how hesitation markers, repetition and deviation support it. Section 3 shows how removing these options for sustaining fluency can create a cognitive burden that, in extremis, leads to brain fry and, often, a strong emotional response. We illustrate these effects with evidence from broadcasts, the writings of JaM players and long-time chairman Nicholas Parsons, and the experiences of PM. Section 4 considers the options available for minimising the risk of brain fry within the game, again exemplifying them from a range of sources. In Section 5, PM comments directly on his own approach to JaM, illustrating an alternative path to success. The conclusion, in Section 6, draws the findings together, to capture the essence of the JaM format.

1.1. Just a Minute

Just a Minute (JaM) is a half-hour radio panel game on the UK’s BBC Radio 4, the BBC World Service and the internet platform BBC Sounds.Footnote1 First broadcast in its current format in 1967, it was chaired for almost 52 years by Nicholas Parsons, and is now chaired by Sue Perkins. It is recorded in front of a live audience and four panellists take turns to try and talk for (up to) one minute on a topic given to them, without hesitating, repeating themselves (other than the words on the topic card) or deviating from the subject. The other players listen for breaches of those rules and if they buzz in correctly, they receive a point and take over the topic for the remainder of the minute. An incorrect challenge rewards the speaker with a point, and whoever is speaking when the whistle is blown to mark the end of the minute also gains a point.

Notwithstanding the allocation of points, final totals are never given, only a ranking, a fact significant for understanding the phenomenon of JaM. Because players must jointly generate one minute of content on the topic, editing within rounds is difficult to achieve and there are no retakes (Parsons Citation2010, 156), so being vague about the scores enables editors to select, and reorder, the best rounds from a slightly larger number recorded. The integrity of complete rounds ensures that the show retains its vital characteristics of spontaneity and unpredictability, in contrast to the more heavily ‘over-recorded’ and edited radio panel games and shows with which it shares the famous six-thirty pm Radio 4 slot.Footnote2

In its early days, JaM had four resident panellists, Clement Freud, Peter Jones, Kenneth Williams and Derek Nimmo, who developed their own styles. PM replaced Williams in 1988 and, along with a few others, he has provided a backdrop of continuity for many new players over the years, most of whom appear only a handful of times.Footnote3

JaM can be exhilarating to play. Of Gyles Brandreth, Parsons says,

when he is about to talk on a subject, [he] begins to wind himself up, drawing in deep breaths, sitting upright, his eyes sparkling with anticipation. Suddenly he launches himself into the narrative with great gusto, often clutching his waistband as he becomes more and more animated and enthused (Parsons Citation2014, 410-411).

However, for others, the experience is more negative. Jenny Éclair reports: ‘I was terribly intimidated by the whole thing and at one point I had to go to the bathroom to rest my head on the cold white tiles, as I felt I might faint with the stress of it all’ (Parsons Citation2014, 209). Kenneth Williams (Citation1985, 184) observed: ‘It’s rather like putting leg-irons on a sprinter: one’s chances of running the race, let alone winning it, are hampered from the beginning.’

As will become clear, the most successful players are those who have had time to develop strategies and skills: the more experience you have, the more confident you feel. However, we shall show in Section 5 that confidence is not simply the outcome of experience. It is a strategy for managing the challenges of the game.

1.2. Unpacking the rules

The JaM game was devised in the 1960s by Ian Messiter. He adapted it from his own earlier and more intricate radio game One Minute Please, which broadcast on BBC radio in 1951.Footnote4 The JaM rules, while inherently simple in outlawing repetition, hesitation and deviation, attract negotiation, not least on account of linguistic definitions. With regard to repetition, for instance, plurals are counted as different words from the singular. Finite and infinite verbs, if identical in form (e.g. to put; he put), constitute repetition. Homophones (words that sound the same but are spelled differently, e.g. bare, bear) count as different words. There is less consensus about homophones that are also homographs:

Derek: ‘Suit’, repetition of ‘suit.’

Victoria [Wood]: No, in two different senses, suit to suit and suit in the costume sense.

Nicholas: She’s quite right, you know, Derek [AUDIENCE APPLAUD]

Kenneth [Williams]: It doesn’t matter in what sense! The word’s the same, and Derek’s right. It was repeated! (Parsons Citation2014, 235).

To understand why such disagreements are likely within JaM, we have to take into account how players will be tracking what they hear. To detect repetition, players must pay attention to sounds as well as meaning, otherwise they might inadvertently claim repetition for a synonym (e.g. sofa followed by settee). However, tracking phonological information is independent of semantics, so that two words sounding identical will be clocked as repetition. A player’s only way to recognise that the meanings were different would be to back-track on the content. But since the phonological loop in short term memory is restricted in both size and longevity (Cowan Citation2008), in the course of doing so, they would likely lose touch with the word form they were looking for. In any case, time is of the essence. As a result, we should anticipate that players, hearing the same form, are likely to challenge it as repetition, even if the meaning is different (and then, as Williams does, justify that sort of challenge as within the rules).

Although hesitation is somewhat easier to define—a pause or a filler like er or um—there are still, inevitably, debates in JaM about whether a gap counts as a hesitation, if it has been motivated for some other reason, such as waiting for laughter to subside, or even just taking a breath.

Originally, deviation referred to not sticking to the topic on the card, but later was extended ‘to deviation from the English language’ thus allowing challenges for garbled output and speech errors (Example 1).

Example 1: Deviation from the English language.Footnote5

Although it might seem detrimental to JaM that the rules are somewhat fuzzy, the vagueness of what counts as repetition, deviation and hesitation may actually account for the long-term success of the game because it creates turbulence and humour.

1.3. Just a Minute as comedy

JaM is a comedy show on the radio, and so the humour needs to be verbal and situational, rather than visual. Humour upends our expectations, linguistic and pragmatic, often by setting up a particular frame of reference that is later undermined by revealing an alternative frame (Skynner and Cleese Citation1993; Carr and Greeves Citation2007; Dynel Citation2011; Attardo Citation2020; Morreall Citation2020). In JaM, the humour is derived from the verbal gymnastics of keeping to the rules, along with anecdotes, non-sequiturs, situational contradictions, puns and disputes. What is unusual about JaM is that there is a clash between the classic tools for creating humour and the rules of the game. In comedic terms, hesitation is a device for achieving timing. Repetition is used for reinforcing an idea, reframing, and for catch phrases. Deviation is at the very heart of comedy, because the audience thinks the account is going in one direction, and it unexpectedly goes in another. Being funny without using any of those standard techniques is not easy, thus adding further to the cognitive challenge of playing.

1.4. Previous research on Just a Minute

Despite its potential interest to linguists, little research has been carried out on JaM. There are a few journal articles reporting the use of the game’s format as a vehicle for improving spoken fluency and oral confidence – in Gaza (Shaaban Citation2020), India (Gayathri Citation2016; Kumar Citation2017), Indonesia (Pertiwi and Amri Citation2017; Jaelani and Rizkatria Utami Citation2020) and Saudi Arabia (Rao Citation2018, Citation2019), though, in fact, none investigates or demonstrates the method’s efficacy for that purpose.

Christiansen (Citation2008, Citation2011) draws on a significant corpus of JaM transcripts to look at the use of slang in the English language generally (rather than in JaM specifically) and the use of certain discourse features. But so far, there is only one study that examines the effect of the JaM rules on how participants speak. Wray (Citation2023) undertook two large analyses of JaM. The first compared the speech of PM within successfully completed minutes of JaM, with individual minutes from an interview PM gave in front of an audience, and found that although the amount of repetition was certainly less in JaM, it was far from negligible. The second analysis tracked the instances of repetition in twelve complete JaM episodes (that is, in contributions by a number of different players), to establish what sorts of words were repeated with, and without, detection. The results were complex, but indicated that while, as often asserted in relation to JaM, the repetition of ‘small’ (i.e. function) words was permitted, that was far from the full story, since function words were challenged under certain circumstances, while many content words slipped through, unchallenged. We return to that study in Section 2.3, when the impact of JaM on what players say is examined.

2. Fluency and Just a Minute

The rules of JaM, not to hesitate, repeat or deviate, may appear to outlaw three rather discrete features, each with its own dynamics in spoken discourse. However, that is not the case. At the core of JaM is speaking fluently. Hesitation is a direct marker of failing to do so, while repetition and deviation are often indicators of compensatory actions, that would, in other circumstances, be available to assist the speaker in avoiding hesitation. To understand how these features of speech work together, it is necessary to step back and explore why fluency is so important to us that we would develop a toolbox for protecting it.

2.1. Fluency in regular spoken discourse

The term fluency in this context is speech ‘which flows easily without noticeable pausing or backtracking’ (Foster Citation2013, 2124). Speakers value fluency because without it, they are likely to lose the floor (i.e. the opportunity to speak), or at least the attention of their hearers. In everyday interaction, the purposes of speaking include: to gain attention, impart information, express and secure social relationships, invite responses, and so on. Once someone has lost the floor, they are not in a position to achieve these outcomes. As a result, there is a high premium on remaining sufficiently fluent. But sustaining fluency is not always easy. There are many potential impediments, not least interruptions due to the hearer’s own desire to win the floor. Furthermore, the speaker’s capacity to manage the complex internal processes associated with turning thoughts into comprehensible speech may be placed under pressure by competing cognitive demands.

Anything that interferes with the speaker’s ability to find words, construct comprehensible, coherent text, track the context and gauge the pragmatic demands of the situation, will undermine the effectiveness of the output, including, potentially, its fluency. A range of linguistic tricks, acquired through child- and adulthood, is required to effectively manage these demands, including processing shortcuts that need less resource, until the overall load is restored to a manageable level (Wray Citation2017).

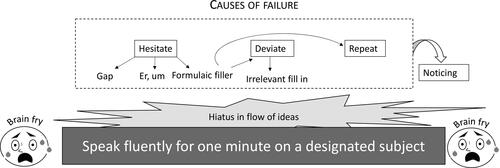

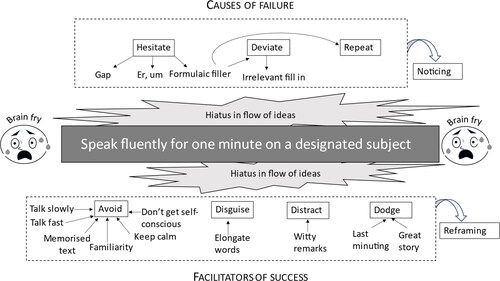

Some of the most visible of these tricks are fillers, repetitions and deviations (), most of which are directly or indirectly outlawed in JaM (see discussion in Section 3).

Table 1. Example resources for sustaining fluency.

2.2. The challenging rules of Just a Minute

‘Well, I don’t know what to do in this game! I’ve never been so terrified in my whole life’ (Elaine Strich, quoted by Parsons Citation2014, 241).

In JaM, fluency is paramount. The smallest silence will attract a challenge so that the player loses the floor. However, as showed, the rules get in the way of remaining fluent. Filling a silence with um or er will count as hesitation, as could even a cough or laugh. A player might get away with I mean or you know as a filler, but only once, because after that, it will be repetition. In its own right, repetition is a recognised way to manage information flow (Giulianelli, Sinclair, and Fernández Citation2022) and yet repeating material is not permitted in JaM. Meanwhile, replacing an unavailable word with a proform like thingamajig might be challenged for deviation from the subject (or the English language), as will adding less relevant information to facilitate planning.

Just a Minute creates the perfect storm. It places players into an inherently stressful situation—extemporising in public—and, as the cognitive pressure threatens to undermine their fluency, the rules prevent them adopting the customary solutions of normal conversation. Since the need to be vigilant about repetition, deviation and hesitation will itself further increase stress, we see that the cleverness of the game’s design lies in first creating high cognitive load and then exacerbating it, to the point where it is extremely difficult not to resort to the outlawed toolkit of solutions in .

2.3. How do the JaM rules affect the language?

At times, the impact of the JaM rules on what is said on a topic, and how, is almost imperceptible. But at other times, the discourse is significantly distorted—itself frequently a source of humour. In Example 2, the topic is Abba. Jan Ravens repeats the word song and loses the turn to Paul Merton. Merton’s attempt to name Abba songs is hampered by inherent repetition within the titles (Knowing Me, Knowing You; SOS), which he overcomes by circumlocution.

Example 2: Repeating and avoiding repeating.Footnote6

Complete minutes, where a speaker begins and finishes the topic without being challenged, are sufficiently rare for them to be commented on when they occur. Most broadcast programmes, with eight to twelve topic rounds, do not feature one. Nevertheless, they can be achieved, and PM is one of those most able to do so. According to the JaM statistics siteFootnote7, by 2017, there had been 306 instances (in 50 years of broadcasts), which included 31 individuals completing a minute only once—some achieved through leniency towards first-timers. Of the 306, more than 10% (32) were achieved by PM, second only (at that time) to Kenneth Williams (66).

But what does a successful minute actually look like? Although heralded as devoid of hesitation, repetition or deviation, it would be more accurate to describe it as a full minute without anyone noticing or challenging for hesitation, repetition or deviation. In other words, some breaches of the rules get through.

In Wray’s (Citation2023) analysis, mentioned earlier, only hesitation was totally absent from PM’s successful minutes. Deviation, which is always in the eye of the beholder, was arguably rather frequent in PM’s imaginative responses to a topic. But most striking was the high level of repetition. The mean percentage of repeated types (different words) in the twelve complete minutes of PM’s that were analysed was 21.64%. Counting tokens (total repetitions) it was 34.54%. Although both figures were significantly lower than in the ‘control’ condition of twelve discrete minutes from an interview with PM in front of an audience, these values are still high in absolute terms, given the aim of having no repetition.

Wray (Citation2023) found that repetitions of a given word were less likely to be challenged (thus, by inference, less easy to notice) if the occurrences captured different shades of meaning. For example, people can refer to specific nameable individuals (e.g. some people I know), a collective of individuals (e.g. people in the suburbs), or be a generalised proform (e.g. people might say).

Unsurprisingly, Wray (Citation2023) reports that the main source of the repetition was function words, which are difficult to avoid using. The game would not operate effectively if repetitions of this sort were challenged every time they occurred. Leniency in the JaM rules arose after experimenting, in the very early days, with penalty rounds in which a word like and or the was not permitted at all—something that the players found inhibiting (Parsons Citation2014, 43). PM describes Esther Rantzen as one of the worst contestants, because she insisted on challenging words like I and and (Jeffries 2016).

Wray investigated whether it was the frequency of use in the language that made the repetition of function words relatively invisible and/or tolerable. In contrast to content words, where both frequency and the proximity of the mentions helped determine whether or not a repetition would be challenged, for function words only proximity appeared to contribute—indeed, they were usually noticed only when they were repeated in very quick succession (e.g. Example 3).

Example 3: Exceptional challenging of a function word.Footnote8

Excessive use is therefore typically required before a challenge occurs (Brandreth Citation2022, 5). Otherwise, the repetition of function words is either tolerated or, more likely, not easily noticed. This would be because their meaning is relational (e.g. linking content words grammatically) rather than referential, so they have little independent semantic presence for the players to latch onto and remember. Meanwhile, they are mostly very short words that are not strongly emphasised, and so they leave little phonological resonance.

3. Manifestations of brain fry in Just a Minute

A minute. A MINUTE. It’s such a tiny unit of time – it goes by relatively unmarked unless you’re boiling an egg or counting down to a nuclear catastrophe. But on this show – it’s everything. When you’re in that minute, eyes bulging, neck straining, it feels like an hour. It feels like a lifetime. It feels like wading through treacle while the synapses of your brain desperately hunt for synonyms. It feels like panic and pain and then, suddenly, at around the 50-second mark, it feels like you’re flying. It is, I believe, the closest thing we’ll ever get to flying.

Sue Perkins (Parsons Citation2014, 368).

‘Brain fry’ is a colloquial term for cognitive fatigue or overload. Although it is often associated with extensive periods of overwork, in the context of JaM we use it to refer to the immediate demands of playing the game. Brain fry can occur when players are listening, when it will manifest as an inability to track breaches of the rules. However, for obvious reasons, it is most easily observed when a player is trying to speak, and so that is the focus of the discussion that follows.

shows how the central external pressure on JaM players derives from the rules. The core requirement is to speak fluently for one minute. As illustrated earlier, in , when there is a hiatus in the flow of ideas, as is typical in normal speech production, the solution is to hesitate or cover a hesitation with a filler. But in JaM, both will attract a challenge. A third option is to disguise a hesitation with a formula like you know. While formulas in themselves do not infringe the rules, they have certain characteristics that can result in a challenge.

First, automatic fill-ins like you know are often little more than verbal ticsFootnote9 and likely to be inadvertently used whenever the need for them arises, leading to repetition. Second, since such formulaic expressions can be generated without attention to their component parts (Wray Citation2002), we often don’t notice the individual words inside them. As a result, using them is likely to lead to inadvertent repetition. We saw in Example 2 how, when Jan Ravens repeated song, the first occurrence was inside the formula Eurovision Song Contest—she might not have had a strong sense that song actually featured in the name of that show. When Derek Nimmo said: ‘It seems to me to be totally ludicrous that they have a rate of inflation there under two per cent per annum’ (Parsons Citation2014, 142), he was challenged for repetition of per inside two different formulas, within which per is relatively invisible. This peril even extends to the two Bs in BBC, which repeatedly catches players out. Finally, some filler formulas could potentially be challenged as deviation, if their literal meaning is at odds with the topic—for instance, if a player said, I love mornings because, at the end of the day, they’re the best time to do the housework.

The role of ‘noticing’, including self-monitoring, is also captured in , for while it is the rules, along with the live audience performance context, that line up the conditions for brain fry, it is the player’s internal cognitive activity that actually causes it. If a player simply spoke as normal, allowing hesitation, repetition and deviation to occur, and didn’t mind being challenged for them, there would be far less cognitive pressure. But insofar as players are trying to abide by the rules and to win, they create additional burden by trying to manage what they say and monitoring their own output. The level of brain fry, then, is determined by how much they need to control what they say in order to avoid infringing the rules, how much they notice the errors they make, and how much they care. The exertion may be visible:

When Gyles [Brandreth] is telling a story, rattling along, making things up, he puts himself under such enormous pressure not to repeat, hesitate or deviate that he forces his imagination to work overtime, producing a physical reaction. You can see it (Parsons Citation2014, 410-411).

The more players become anxious, the more likely they are to make mistakes. The players who mind losing find JaM particularly stressful. Kenneth Williams was renowned for taking JaM very seriously. He would get angry at being interrupted and felt wounded when he had put in considerable effort for no reward, e.g. ‘What’d you clap him for? … It’s me that done the work and he got in and you know it with those last two seconds. It’s a disgrace!’ (Parsons Citation2014, 337). Although a measure of Williams’ reaction was an act, in Parsons’ view, there was genuine emotion in his outbursts. Williams (Citation1985, 185) himself admits, ‘If I’m given an unfair judgement I sulk or scream abuse at the chairman.’

Another player with a strong emotional investment was Clement Freud, who on one occasion

took my decision to heart, allowing it to fester for a couple of hours. That is the aspect that surprises me most… that such a clever man… could allow himself to become so worked up over something that ultimately was entirely trivial (Parsons Citation2014, 333).

In fact, there was considerable, often aggressive, rivalry between Freud and Williams, due, in Freud’s view, to Williams’ egotism:

No longer a word game gently contested among four players, it was now a Williams monologue performed for a small audience of players (me, Nimmo and Jones) and a burgeoning audience, also the Kenny Williams claque: a couple of dozen fans led by Kenny’s mother and aunt’ (Freud Citation2001, 147).

The listeners liked her because she was good at the game and sounded like a real character, but she was not popular with the audience in the studio because she looked miserable and appeared irritable. In one particular show, her feelings towards Paul Merton boiled over. Paul challenged her, as he was perfectly entitled to do, and Wendy snapped, ‘You’re having a go at me again! You’re always like that. What have I done to you?’ Wendy was not joking; this was said in deadly earnest (Parsons Citation2010, 140).

It is a necessity for me to concentrate very hard through every programme…. People often think I have some kind of backup when judging challenges, such as an earpiece to the producer. That would not work; the delays would kill the show. So I have to listen carefully and make instant decisions. I am not so much enjoying the show as paying attention to every word the panellists say. As a result, when I listen to the broadcast of Just a Minute, it is as though I am hearing the show for the first time.

4. Navigating brain fry

How, then, do successful players manage the potential effects of brain fry? extends , by identifying four broad types of strategy that we have identified in broadcasts and accounts of games: avoidance, disguise, distraction and dodging.

In avoidance, the speaker takes steps not to experience a hiatus in idea flow in the first place. Talking slowly, as Clement Freud famously did, is one option. Parsons (Citation2010, 141) comments: ‘He was a shrewd man and knew that if he spoke at a measured pace, without actually hesitating, he was far less likely to be challenged.’ Other players, including Kenneth Williams and, often, PM himself, talk extremely fast. It might seem counterintuitive that talking faster can avoid a hiatus in idea flow, given that ideas are needed more promptly. But fast speech could help the player stay in ‘the zone’, totally focussed, and not distracted by other thoughts.

Players sometimes bypass the need for original ideas entirely by quoting from memory. Parsons’ (Citation2014) examples include Tim Rice reciting the spoken section in Elvis’s Are You Lonesome Tonight? (224), PM repeating exactly what Peter Jones had just said (337), and a youth player trying the same trick in an edition of the junior version of the show (440). Finally, players can exploit a long topic title, as Derek Nimmo did:

I rather like having subjects like the things of mine refused by garbage collectors, because you are allowed to repeat that line, the things of mine refused by garbage collectors. And if you get a long question like this, it occupies most of the minute you are trying to speakFootnote10

Even safer would be to prepare the topic in advance. Freud (Citation2001, 148-149) claims that Kenneth Williams would ‘ask the producer for bizarre subjects, like Theosophus III, so that he could (a) mug up on it and do a hilarious monologue and (b) inhibit us from challenging him for fear of getting the subject and having to talk about someone of whom we knew less than nothing.’

Having said that, it is central to the ethos of JaM that the game is unrehearsed. Bedford (2015) points to a Twitter discussion after a particularly fluent delivery of a full minute by Gyles Brandreth on the topic Alice in Wonderland, which a listener considered to be ‘proof of scripted rehearsal.’ Brandreth replied ‘Absolutely not’ and another player, Jane Godley, commented ‘I have done Just a Minute and have never heard of a rehearsal. It was always in the moment.’ An audience member adds, ‘It clearly wasn’t scripted… I was at the recording.’ Bedford comments on this discussion as follows:

It’s interesting, so many people do feel that really good improvisation must in some way be a con. A few years ago now a former producer said the panellists did have the option of seeing the subjects they were going to start. But anyone who has been to a recording must know the show is not scripted. Could it be that some panellists think ahead about what they are going to say? Maybe. But the reason that Gyles is so good is – well, because he is so good (Bedford 2015).

One way of distracting the other players, so they don’t notice infringements, is to steer the topic into an area that they will enjoy or react to. The most commonly used version is what Sheila Hancock referred to as Nick-baiting, where players make affectionately disparaging comments about Parsons (Examples 4 and 5), something that he seemed not to mind too much. According to comedian Barry Cryer (2020), Parsons ‘loved being the butt of affectionate jokes. He had no ego.’

Example 4: Nick-baiting 1, 2007.Footnote13

Example 5: Nick-baiting 2, 2004.Footnote14

Finally, players can dodge being challenged. One way is by timing their interruption. Williams (Citation1985, 184-185) complains that ‘Clement Freud waits till someone has almost completed the time before challenging on some minor point, leaving the field free for him to speak for a few seconds and score an easy victory.’ Peter Jones’s dodge on one occasion was flattery. He successfully reached the end of the minute by talking effusively about a stage performance by Kenneth Williams. He commented, ‘I knew Kenneth wouldn’t interrupt me!’ (Parsons Citation2014, 177).

All of these approaches to managing the risk of brain fry reflect a core assumption: that the main purpose of the game is to speak fluently for one minute. But in the next section, PM directly describes his own approach to mitigating the risk of brain fry—reframing the purpose of the game.

5. Paul Merton’s approach to Just a Minute

There is no question that JaM feels like a very good workout for the brain, both when you’re listening out for things to challenge and, particularly, when you’re speaking. You have to learn some techniques. I tend to talk fast, but that does risk introducing errors. If you talk more slowly, you have more time to find synonyms, and to self-monitor, though arguably it’s a good idea not to listen too closely to yourself or you’ll trip up. To avoid repetition, if I’ve already spoken on the subject and then I get another chance, I approach it in a new way, so I have a clear run.

I think I’m less affected by the pressure than some other players are. One reason is that I have many years of experience in improvisation, where you turn up at the venue and there is no show, as such. You have to make it up and you have to trust it’s going to work because it’s worked before. Because JaM isn’t scripted, it’s very similar. I’ve done radio shows where I’ve had a script in front of me and that gives you something to worry about. But with JaM, there’s no need to panic. You just have to trust that you’ll start talking and funny stuff will emerge. For me, it always does. This is important, because it’s anxiety that hampers you in this game.

In my early days doing JaM, I was like the new players we get now, who start okay but run out of confidence after ten or fifteen seconds. It’s confidence that gives you fluency. Back then, I couldn’t speak for a minute without interruption. But now, I can find what sports stars call the zone, a feeling of knowing I’ll do well and getting a natural flow. It’s as if my brain is more of a receiver than a transmitter. Rather like an old tickertape machine, I start talking and I don’t know where the sentence is going. I can be surprised where it takes me.

This means I come into a show differently to the less experienced players. I don’t get nervous, I get ready. The newcomers are generally pretty nervous, and there’s not much you can say to them to help. I try to tell them it’s like playing golf. Nobody expects to get a hole in one or shoot five under par when they first play it. If you can just hit the ball in the right general direction, you’d consider that a kind of success. So in JaM, if you can speak for 20 or 30 seconds before you trip up, that’s fine. But people don’t see it that way. They put huge pressure on themselves by making the mistake of thinking they have to be really good at avoiding hesitation, deviation and repetition, when in fact, that’s not the most important thing.

Playing JaM is about making a good show, and that isn’t to do with how long you can talk for. There’s much more fun to be had from interruptions and challenges. The show needs to be amusing, accrue laughter. It doesn’t matter who wins, as long as we’ve jointly achieved that goal. You can get very experienced broadcasters on the show who are dreadful because they see JaM as a competition when actually it’s a team effort, to entertain. Part of the skill is learning how to manage the pace and the mood. If I feel the programme needs a boost of energy, I’ll talk quicker. Inevitably I will then falter, because I can’t think of another word for ocean or whatever, and that will raise a laugh.

Sometimes I’ll deliberately sabotage myself, to lighten the mood. When the topic was Keeping my Diary, I started with: ‘Well I’ve got about fifteen cows at the moment, and what I do is I milk them regularly.’ I knew I’d get buzzed for deviation, but getting the laugh was more important. When Nicholas gave me the topic Repairing a combine harvester, I said, ‘Oh good. This is perfect. I spent five years on a farm when I was growing up.’ But when the minute started, I said, ‘I know nothing about repairing combine harvesters’ and stopped, so someone could challenge me for hesitation. If I was playing to accrue points, I obviously wouldn’t do that.

Ironically, I often do win. That’s partly because I can get points for an amusing challenge even though it isn’t upheld. At one point I won twelve episodes in a row and I realised I needed to stop it happening. If Man United keeps winning, then people want Leicester City to have a chance.

So that’s one way that you have to manage the audience’s attitudes. Another is being seen as mean. If you challenge a new player too much, they’ll shift all their sympathy away from you, and they won’t want you to challenge. And yet if you don’t challenge to some extent, you undermine the game and things start to fall apart. It’s important for the game that there are a couple of very experienced, core players in each show that can keep that balance.

6. Conclusions

Our aims in this article were (a) to characterise why the constraints in JaM make the game so difficult to play; (b) to explore what impact the cognitive pressure of JaM has on players; and (c) to establish how players manage the cognitive burden so that they can play successfully without experiencing (too much) brain fry.

Regarding (a), we demonstrated that the central cause of cognitive overload is the way the game’s rules undermine the customary means by which fluency is sustained during a spontaneous narrative. In regular speech, we can manage the idea flow and gain time while we plan or regroup our ideas, by inserting hesitation filler words, repeating material and putting in asides—deviations. Outlawing these options in JaM makes speaking fluently much harder. A second contributor to the risk of brain fry is that the players are aiming to be amusing. Hesitation, repetition and deviation are all key devices for delivering comic material, so, again, the need to avoid their usual tools of the trade puts the players under pressure.

In relation to (b), we saw that the cognitive pressure imposed by JaM generates linguistic errors and also a physical and, particularly, strong emotional response, which is centred on the desire to succeed in the task. Players who are not yet adept at the game are at most risk of feeling defeated. Some become aggressive, while others might drop back. Already nervous, inexperienced players are apt to lose confidence, self-monitor and freeze.

As for (c) we showed how players take a range of approaches to reduce the risk of losing fluency: avoidance, disguise, distraction and dodging. They might speak very slowly or very fast, elongate words, adopt material they have memorised for another purpose, find (or invent) an angle on the topic that takes them into familiar ground, or manipulate the game and its players in ways that give them advantages for completing the minute and winning the point.

PM’s experience, however, sheds a different light on JaM. While not denying that the game is cognitively demanding, he has described side-stepping the expectation of winning points by means of speaking fluently. He has learnt to construe the purpose of the game differently. Drawing on his skills in improvisation, he finds it liberating to not have a script, given that he can trust himself to generate output ‘in the zone.’ He describes the JaM venture as a team effort to entertain, rather than a contest to be best at the core task of talking for one minute.

PM’s approach is not a subversion of the game but an acknowledgement of its true nature, because, as one time producer David Hatch wrote to Nicholas Parsons in 1968, ‘The point and fun of this game comes out of [the] challenges and not from a brilliant exposition of one minute’ (Parsons Citation2014, 59).

Any successful vehicle for entertainment needs to balance a range of parameters and constraints. The remarkable longevity of JaM (now close to its 1000th episode, over some 66 years) cannot be fully explained in terms of an audience watching performers undergo the extreme cognitive challenge of constrained linguistic output, something that could become excruciating if not balanced with humour and managed ambiguity. The winning quality of JaM is the delicate balance between an ingenious fundamental format and a vital undercurrent of prioritising the show’s entertainment value, the latter in turn being a means of managing the audience’s needs and expectations.

This article lays out a path for asking how other show formats achieve these outcomes, or fail to, and what relationship there is between the appeal and success of a show and its particular profile for combining a core concept with the necessary goal of sensitively monitoring and addressing the audience’s response. In short, there is plenty more to investigate in relation to the dynamic layers of tension and intention that are necessary for the creation of a successful entertainment format.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alison Wray

Alison Wray is a Research Professor in the Centre for Language and Communication Research, Cardiff University, UK. As a linguist, she explores how language sits at the interface of cognition and social interaction. She has won international awards for her books on formulaic language (Formulaic Language and the Lexicon, 2002; Formulaic Language: Pushing the Boundaries, 2008) and on dementia communication (The Dynamics of Dementia Communication, 2020; Why Dementia Makes Communication Difficult – a Guide to Better Outcomes, 2021) and has also contributed to research into the evolution of language, and second language acquisition.

Paul Merton

Paul Merton is a British comedian with a major UK media presence (see https://www.paulmerton.com). He is well-known for his improvisation, stand-up and dead-pan contributions to radio and television shows including Just a Minute, Have I Got News for You, Room 101 and Whose Line is it Anyway? He has authored several books, including his autobiography, Only When I Laugh (2015).

Notes

2 PM reports that for a 28-minute transmission of JaM, about 35 minutes is recorded, which accommodates two extra rounds. Shows like The News Quiz (BBC Radio) and Have I Got News for You (BBC Television), with comparable transmission lengths, can have up to two hours of recorded material.

3 The Wikipedia page for Just a Minute lists over 250 different panellists https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Just_a_Minute. See http://just-a-minute.info/who.html for brief profiles of how different players have approached the game.

5 http://just-a-minute.info/jam496.html, 24.02.2003.

6 Series 82, Episode 6, 10.09.2018 (not currently available online).

8 http://just-a-minute.info/jam442.html 14.01.2002.

9 This is not to deny that expressions like this can have a function, meaning and full legitimacy in the language (Traugott Citation2022), only that they can also serve the primary purpose of preventing the loss of fluency.

10 http://just-a-minute.info/jam531.html, 18.09.82.

11 https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m0017k7t 23.05.22.

12 http://just-a-minute.info/jam529.html, 11.09.1982.

13 http://just-a-minute.info/jam695.html, 22.01.2007.

14 http://just-a-minute.info/jam536.html, 09.02.2004.

References

- Attardo, Salvatore. 2020. The Linguistics of Humor: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bedford, Dean. 2015. "Is Jam Scripted or Rehearsed?" Just a Minute blog (blog). June 2. http://justaminutesite.blogspot.com/2015/06/is-jam-scripted-or-rehearsed.html.

- Brandreth, Gyles. 2022. A History of Britain in Just a Minute. London: BBC Books.

- Carr, Jimmy, and Lucy Greeves. 2007. The Naked Jape: Uncovering the Hidden World of Jokes. London: Penguin.

- Christiansen, Thomas. 2008. “Trends in the Use of Slang in the Panel Show Just a Minute in the Period 1967-2006.” In Socially-Conditioned Language Change: Diachronic and Synchronic Insights, edited by Susan Kermas and Maurizio Gotti, 445–469. Lecce: Edizione del Grifo.

- Christiansen, Thomas. 2011. Cohesion: A Discourse Perspective. Bern: Peter Lang.

- Cowan, Nelson. 2008. “What Are the Differences between Long-Term, Short-Term and Working Memory?” Progress in Brain Research 169: 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(07)00020-9.

- Cryer, Barry. 2020. "Taking a Minute to Remember Nicholas Parsons - a Friend Who Always Knew the Score." The Telegraph, 29 January, 2020. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/01/29/taking-minute-remember-nicholas-parsons-friend-always-knew/.

- Dynel, Marta. 2011. “Pragmatics and Linguistic Research into Humour.” In The Pragmatics of Humour across Discourse Domains, edited by Marta Dynel, 1–15. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Foster, Pauline. 2013. “Fluency.” In Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics, edited by Carol A. Chapelle, 2124–2130. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Freud, Clement. 2001. Freud Ego. London: BBC Worldwide.

- Gayathri, S. 2016. “Just a Minute (or Jam): A Joyous Communication Enhancement Game.” International Journal of Communication and Media Studies 6 (1): 13–16.

- Giulianelli, Mario, Arabella Sinclair, and Raquel Fernández. 2022. “Construction Repetition Reduces Information Rate in Dialogue.” 2nd Conference of the Asia-Pacific Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics/12th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Taipei, Taiwan. 21-23 November 2022.

- Jaelani, Alan, and Imanda Rizkatria Utami. 2020. “The Implementation of Just a Minute (Jam) Technique to Scaffold Students’ Speaking Fluency: A Case Study.” English Journal 14 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.32832/english.v14i1.3784.

- Jeffries, Stuart. 2016. "Paul Merton on Just a Minute: ‘Our Worst Contestant? Esther Rantzen’." The Guardian, 16 February, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/feb/16/paul-merton-manages-28-years-without-hesitation-repetition-or-deviation.

- Kumar, Sunita Vijay. 2017. “Just a Minute Sessions - a Gift of the Gab.” ITIHAS Journal of Indian Management 7 (1): 44–46.

- Morreall, John. 2020. “Philosphy of Humor.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Edward N. Zalta. Stanford CA.: Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2020/entries/humor/.

- Parsons, Nicholas. 2010. My Life in Comedy. Edinburgh & London: Mainstream Publishing.

- Parsons, Nicholas. 2014. Just a Minute. Edinburgh: Canongate Books.

- Pertiwi, Rinindi, and Zul Amri. 2017. “Using Just a Minute Game to Improve Students’ Speaking Ability in Senior High School.” Journal of English Language Teaching 6 (1 E): 1–7. http://ejournal.unp.ac.id/index.php/jelt/article/view/9664.

- Rao, Parupalli Srinivas. 2018. “The Importance of Jam Sessions in English Classrooms.” Research Journal of English Language and Literature 6 (4): 338–346.

- Rao, Parupalli Srinivas. 2019. “The Significance of Just a Minute (Jam) Sessions in Developing Speaking Skills in English Language Learning (Ell) Environment.” Research Journal of English 4 (4): 237–248.

- Shaaban, Sumer S. Abou. 2020. “The Effect of Just a Minute on Enhancing the Use of Grammar in Oral Contexts among Palestinian Tenth Graders and Their Attitudes Towards It.” Journal of Al-Azhar University - Gaza (Humanities) 22 (1, 4): 1–24. https://shorturl.at/amDM8.

- Skynner, Robin, and John Cleese. 1993. Life and How to Survive It. London: Methuen.

- Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. 2022. Discourse Structuring Markers in English: A Historical Constructionalist Perspective on Pragmatics. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Wiehler, Antonius, Francesca Branzoli, Isaac Adanyeguh, Fanny Mochel, and Mathias Pessiglione. 2022. “A Neuro-Metabolic Account of Why Daylong Cognitive Work Alters the Control of Economic Decisions.” Current Biology: CB 32 (16): 3564–3575.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.07.010.

- Williams, Kenneth. 1985. Just Williams. London: J M Dent.

- Wray, Alison. 2002. Formulaic Language and the Lexicon. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wray, Alison. 2015. “Why Are We So Sure We Know What a Word Is?.” In Oxford Handbook of the Word, edited by John Taylor, 725–750. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wray, Alison. 2017. “Formulaic Sequences as a Regulatory Mechanism for Cognitive Perturbations During the Achievement of Social Goals.” Topics in Cognitive Science 9 (3): 569–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12257.

- Wray, Alison. 2023. “Hidden in Plain Sound: Overlooked Repetition in Just a Minute.” Yearbook of Phraseology 14 (1): 33–88. https://doi.org/10.1515/phras-2023-0004.