ABSTRACT

Our contribution describes a reorientation in the intelligibility of governance practices authorised under international law. Observing the World Bank, we narrate new managerial attitudes and organisational routines that exhibit heightened ‘risk appetites’. Risk and complexity are no longer seen as limiting conditions on the institutional project, but as co-constitutive elements and constructive tools, including new sets of heuristics aimed at governing with and through contingency and unknowability. The practices that we observe are characterised by adaptive, iterative and recursive routines, flexibly attuned to immanent possibilities and aims of resilience. We situate these changes in a genealogy of governmentality, focusing on the relation to a ‘surplus of life’, or unruly elements of populations that persistently escape productive incorporation into the closure of institutional programmes. The World Bank’s turn to resilience as a particular rationality of reform signals an institutional attempt to enrol what has escaped prior efforts at determinate institutional intervention.

Oedipus and the wellness guru

Our contribution to this special issue takes off from questions raised in this symposium about the impossibility of closure in institutional contexts exhibiting features associated with un-governance. Closure refers in this context to the orientation of institutional practices towards ‘determinate and mobile artefacts’Footnote1 deployable for pre-defined governance purposes, such as benchmarks, exchangeable models and rules of general applicability. The impossibility of closure, in turn, refers to a recognition in institutional practice of ‘the inescapably fragile, contingent, interested, [and] indeterminate nature’ of those formerly determinate and mobile artefacts, leading to the recognition of the ‘ultimate practical impossibility of matching institutional structures with desired outcomes’.Footnote2 The impossibility of closure reflects radical complexity in certain domains of global governance, such that institution-building will only produce ‘ever-more complex effects’ despite an institutional mission to ‘govern or regulate complexity in the world’.Footnote3 Moreover, the impossibility of closure is not merely an abstract observation, but ‘emerges as a mundane and routine part of the performance of institution-building practices’ – whether in moments of misrecognition and miscommunication, or an acknowledgment of limited competence, etc – manifesting the constraints of bounded knowledge.Footnote4 Our interest in these phenomena, in keeping with the introduction to this special issue, is not in the reflexive awareness of these knowledge-limitations exhibited by institutional actors as they nonetheless carry out their institutional practices despite the limitations.Footnote5 Rather, with the editors of this special issue, we are interested in the ways in which such limitations, hesitations or awareness of things lacking are positively mobilised for governance purposes, especially insofar as they are recently deployed in deliberate relation and even productive tension with familiar practices and notions associated with closure in a traditional institutional sense.

A close relationship between law and a defining (or constitutive) lack is not new,Footnote6 but our analysis here proceeds from the possibility that the terms of that relationship have changed. Staging our analysis, we use two archetypal characters to tell a story about the World Bank, namely Oedipus and the wellness guru. This register signals the importance of narrating un-governance in material as well as psychoanalytic terms.Footnote7 Oedipus, in this register, is the classic symbol for the ‘agency of prohibition’ behind law’s traditional posture of constraint, which includes cabining and setting off limits to the unknown.Footnote8 In this latter respect, the character maintains a prohibition that is both inflexible and seemingly superfluous: barring access even to the constitutive lack, which cannot be known (and so cannot be accessed or overcome) in the first place. In short, the oedipal figure activates the defining lack commonly (if variously) associated with law, ‘transforming the inherent impossibility of its [knowledge or] satisfaction into prohibition’.Footnote9 The wellness guru, healthful and flexible popular media success, is a counterpart symbol that we propose to stand for contemporary attempts to get beyond the formal oedipal prohibition, aiming not to cabin the unknown but to access it for positive, productive purposes.Footnote10 The oedipal figure attains to order with discipline. The wellness guru attains to productivity by other means, generating surplus value out of attunement to immanent conditions in the world at large, production that is unattainable by Oedipus.Footnote11 The wellness guru thereby exhibits a technologically mediated adaptive immediacy, keyed to resilience that is achieved not by imposing or adhering to a fixed order, but by exploiting material conditions according to information in and of the moment. We perceive the wellness guru as symbol for a new normative architecture of un-governance, and so will flesh out the figure as we proceed. Institutionally, as our narrative of transformations at the World Bank instantiates, a turn to the wellness guru is visible in the abandonment of formal frames of legal evaluation or decision-making. The cultivation of new managerial attitudes and organisational routines display a heightened ‘risk appetite’ as well as a new set of heuristics aimed at coping (and governing) with and through contingency and unknowability.

Simultaneous to this shift in frames of legal reasoning, we observe a remarkable reorientation in the intelligibility of governance practices authorised under law. We examine these changes in governance practices through a Foucauldian analytic of governmentality keyed to resilience. We situate the changes we observe in the genealogy of governmentality that Foucault sketches, and focus specifically on the relation he draws between governmentality and a ‘surplus of life’, or the unruly elements of populations that persistently escape productive incorporation into the closure of institutional programmes.Footnote12 Recognising the impossibility of closure associated with un-governance, the World Bank’s turn to resilience as a particular rationality of reform signals an institutional attempt to enrol what has escaped efforts at determinate institutional intervention. This will be manifest in the use at the World Bank of adaptive, iterative and recursive routines that are flexibly attuned to immanent possibilities in the subjects and objects of governance. In this situation, surplus and complexity are no longer seen as ‘limit to the world of governmental reason but [as] the basis for governmental reason itself’.Footnote13 Risk and resilience thereby emerge as co-constitutive elements in the adoption of governance tools positively mobilised around the ‘impossibility of closure’.

The World Bank as a site of un-governance

We empirically instantiate the turn to un-governance with reference to the World Bank’s embrace of criminal justice reform – and security sector reform more generally – in the past decade. Two (rather simultaneous) institutional transformations defined the expansion of the World Bank’s mandate and operational engagement in this domain: the replacement of traditional (read: prohibitive) practices of legal evaluation, interpretation and decision-making with performative practices of risk-management, on the one hand, and the adoption of a mode of governance oriented towards the enhancement of local resilience, on the other. In dialogue, these transformations display a deferral of foundational questions on both the legal nature of institutional authority and the causal determinants of socio-political change. They can be qualified as instances of un-governance insofar as they demonstrate a highly productive attunement to conditions of contingency and unknowability in material practices of institutional reform oriented around generally framed aspirational objectives.Footnote14 Expressive of broader changes in contemporary practices of governance that operate under conditions of not-knowing,Footnote15 the institutional templates of risk and resilience signal the emergence of routines, tools and techniques oriented around immanence (rather than transcendence); experimentation (rather than imposition); and open-endedness (rather than teleological determination).

Against this backdrop of developments at the World Bank, we observe a double movement arguably in keeping with the (productive) tension between closure and the impossibility of closure. On the one hand, the practices we describe constitute a radical departure from previous modes of liberal rule. On the other hand, we situate their performance in a longer genealogy of governmentality designed to make populations more productive for competitive purposes by making social complexity legible and available for capture in new material registers of governance.Footnote16 The new tools, routines and heuristics we discuss did not emanate from fixed templates for socio-political governance and change. Instead, they overtly broke from a teleological script for institutional action. The absence of institutional ideal-types, endpoints and foundations is a constant feature in this assemblage of reformist techniques and rationalities. The getting-beyond of these structuring features promises a new or expanded field of opportunity, a making-productive of untapped conditions immanent in the (social) world at large. The unstructured, unknown or un-governed – including the Foucauldian surplus of life – does not figure here as a constraint on governance but rather as conduit and constitutive condition.Footnote17 This constitutive dimension corresponds with an embrace of the impossibility of closure, as part of a move towards un-governance structures of adaptive utility and resilience.Footnote18

In the account of the World Bank, Oedipus is at work in the background as a figure holding together a traditional notion of law for practical purposes, representing a foundational but ongoing intervention to sustain the entirety of a formal structure.Footnote19 According to this intervention, the mission of law is predicated on containing what remains unknown and so achieve closure. In this sense, the unknown or unknowable is constitutive of law, even as law prohibits access to it. But at a stroke, the law defines in a formal sense – it gives form to – the constitutive void that cannot be known. In this light, the law is an intervention, violent and lawless in the first instance like any other intervention, but the one ongoing intervention that achieves the prohibition of any further intervention.Footnote20 Oedipus's law turns what is not or cannot be known into what must not be known. Further, there is an important temporal aspect to such an intervention: it is always retrospective, communicating from the first instance an order that always already exists.Footnote21 Our argument here is that un-governance likewise is intelligible as part of an order that already exists, a temporal order organised according to escalating competition and ever more productivity without object or end (the dispositif). The figure of the wellness guru holds together the new formal institutional mandate appropriate for practical purposes to this condition. In contrast to Oedipus’s intervention, however, the wellness guru turns what is not or cannot be known into what must be exploited. In this way, the wellness guru attains to closure by embracing its impossibility.

Thus, the move to un-governance within an institutional context still committed to closure, such as the World Bank, involves a radical move to incorporate the surplus of life that has historically escaped successive modes of governance. In this sense, the mobilisation to exploit even the surplus of life is constitutive of the move to un-governance, a continuation of a genealogy of governmentality but also a break from prior modes. The continuation and the break both consist of the embrace of the elusive, contingent possibilities encompassed within the multifariousness of a population. The confrontation, then, between the constant escape of the surplus of life and the development of the technologies and tools of modern governance designed to contain it is one factor to explain governmentality keyed to the contingent and emergent in this register of un-governance. These fundamental tensions track and elaborate on the tensions sketched in the introduction to this special issue. They also arguably call for a shift from representational to performative modes of critique that do not take the technology of risk as a (potentially flawed) map of reality, but focuses on its ‘productive work’ in constituting new objects of knowledge, templates of institutional practice, managerial subjectivities and rationalities of reform.Footnote22 We will instantiate immediately below the development and deployment of destabilising techniques at the World Bank that do not pretend to observe fixed models or maps of reality – models or maps that critique might once have shown up for their shortcomings – but are performatively linked to immanent possibility associated with an elusive surplus of life. The object of our analysis as part of this special issue is to contribute to a new stream of critique trained on the productive power apparent in this new mode of governance.

A ‘new normative framework’ – introducing the organisational routine of risk management

The first empirical thread of the article is focused on the way that the World Bank’s turn to criminal justice and security reform was legally justified and rationalised. The analysis is centred around the displacement of prohibitory legal considerations through the development of a ‘new normative architecture’ (described as a ‘paradigm shift’ by former General Counsel Leroy).Footnote23 In this context, we retrace salient changes in the practice of lawyering and the processes of internal legal evaluation in the World Bank, where the deformalised technology of risk-management replaced traditional legal hermeneutics, conceived as constraints or prohibitions. These changes align with the frame of our analysis insofar as they are centred around the shift from ‘rules to principles’ and from ‘risk avoidance to risk management’ as the new paradigm for legal interpretation.Footnote24 This ‘new normative architecture’ also aimed to cultivate a particular prototype of the institutional lawyer: a pragmatic, managerial type who has traded the binary and prohibitive logic of (il)legality for a calculative and adaptive multiplicity of novel techniques to manage contingency and unknowability.

Criminal justice reform and engagement with the security sector of states had traditionally been seen as legally off-limits for the Bank. In 1997, Sureda – who was one of the leading figures in the legal department during the era of Shihata (General Counsel from 1983 to 1998) – had drafted an opinion which expressed that ‘police power is an expression of the sovereign, political power of a state over all persons and things’ and that, for this reason, ‘financing of police expenditures, as a class, would not be consistent with a reasonable reading of the Bank’s Articles’.Footnote25 ‘Appraisal of police activities’, the opinion continued, ‘would necessarily require the World Bank to take into account political and other non-economic consideration and would not be consistent with the prohibition of political activity’.Footnote26 ‘[T]he Bank’, Sureda stipulated, ‘is not an organization to serve all purposes but only those specifically included in the Articles’ and should refrain from engaging in this operational domain.Footnote27 This categorical prohibition resonates with the figure of Oedipus – law appears in its rigid, binary form: a formal delineation of what could reasonably be brought under the reformist ambit of the World Bank. Simultaneously, this legal intervention – described by Leroy as epitomising the ‘old’, ‘traditional’ and ‘risk-averse’ mode of lawyering – equally entailed an expression of the World Bank’s political authority (and its juridical boundaries) as derived from a foundational, formal legal act of sovereign delegation.Footnote28

This ‘traditional’ and prohibitive approach, Leroy lamented, had been ‘interpreted as a complete bar to engagement in the criminal justice sector’.Footnote29 As a clear expression of the entrepreneurial logic that underpinned the core of her legal intervention, she argued that this orthodox practice of ‘drawing a “bright line” between the permissible and the impermissible’ had created an excessive ‘opportunity cost’ for the World Bank.Footnote30 Leroy, a graduate from the French Ecole Normale d’Administration (ENA) who perceived her role as ‘allowing this institution to adapt’,Footnote31 perceived an urgent need to dismantle these prohibitory, outdated evaluations in her 2012 legal memorandum on criminal justice reform.Footnote32 ‘[O]ne traditional view in the Bank has it that criminal justice is … essentially an exercise of sovereign power’, the opinion observes, claiming instead that ‘our understanding of the criminal justice sector has evolved decisively … The sector is now seen as provider of public services’.Footnote33 Considering that the criminal justice sector is seen as merely a ‘provider of public services’ (rather than the expression of state sovereignty), the opinion provides that ‘a blanket prohibition on Bank involvement in the sector on political interference grounds would be overly broad’.Footnote34 Subsequently, and even more significantly, the opinion expresses that the logic of legality ‘need not be binary’ and that ‘political interference’ is not a label assigned to particular domains of state reform but a ‘risk that could be managed’.Footnote35

In Leroy’s turn away from a ‘binary’, prohibitive logic to adaptive ‘management strategies’, we witness the core of what the memorandum describes as a decisive ‘paradigm shift’ in legal practice.Footnote36 This shift in practice was promoted both materially (through the introduction of new templates of assessment and evaluation) and subjectively (through the cultivation of new professional attitudes). In justifying the organisation’s embrace of security sector reform, Leroy thereby enacted a categorical rejection of the mode of law through which Shihata had perceived and constructed his institutional authority: a legal practice consistently aiming at delineating clear ‘boundaries’ between the legal and illegal, the ‘permissible and impermissible’.Footnote37 The structuring device of the ‘old’ legal framework was a dichotomy between political sovereignty and international institutional authority, which aligned with the image of the World Bank as intergovernmental entity operating under international law and always at risk of acting ultra vires. By intervening – in the nature of the wellness guru’s intervention, which supplants the oedipal attitude – to qualify states as both clients (of the World Bank) and providers of services (towards its citizens), the old structuring device was disabled and replaced by a managerial technology of risk aimed at both the management of and productive engagement with contingency.Footnote38

This new ideal of lawyering aligned with President Jim Yong Kim’s call to increase the ‘risk appetite’ and sharpen the entrepreneurial spirit of the Bank’s senior management.Footnote39 As Leroy argued, this did not entail the introduction or rejection of particular legal norms or doctrines, but, rather, implied both a professional reorientation and recourse to a novel set of evaluative tools: the need to ‘instill and nurture a culture of informed risk-taking’ and to ‘build an institutional architecture for informed risk management’.Footnote40 ‘[L]awyers will have a crucial role to play’, Leroy elaborates, ‘but a different one than before, requiring a different approach to legal issues’ supported by ‘a new concept of our normative architecture’.Footnote41 This significant professional transformation – which Leroy described as a general shift from ‘rules to principles’ and from ‘risk avoidance to risk management’ – was grounded in a specific perspective on the nature and purpose of legal authority and manifested in a new set of tools, managerial heuristics and bureaucratic techniques for the assessment and management of ‘risk’.Footnote42

Before elaborating on these specific tools and techniques, it is important to note that the embrace of risk called for by the World Bank’s president was manifested far beyond the domain of criminal justice reform and the specific institutional segment of the legal department. Leroy’s 2013 essay stresses the nexus between changes in the ‘culture’ of lawyering and the observation that ‘the Bank is undergoing certain fundamental changes in its way of doing business’.Footnote43 Signifying these changes was the creation of a new lending instrument – Program-for-Results financing (PforR) – that was introduced by the Bank in January 2012.Footnote44 This instrument ties the Bank’s funding to the ‘achievement of verifiable results and performance actions’ and operates on the basis of ‘country and program-specific strategic, technical and risk considerations’.Footnote45 The programmatic aspects of this vehicle rely on a diagnostic apparatus to quantify, assess and compare ‘the existing economic, technical and political situation in the member’s territory’ as well as ‘the strength of [their] existing institutions’.Footnote46 On the basis of these evaluations, a determination is made on the ‘parameters of the program’ and an operational strategy is developed to ‘strengthen or build’ national institutions in order to ‘minimize risk’.Footnote47 Additionally, in response to recommendations by the Bank’s Internal Audit Department (IAD) and Independent Evaluation Group (IEG),Footnote48 the organisation’s senior management developed a range of reforms proposals regarding the Bank’s main lending instrument – Investment Project financing – which culminated, following Board approval, in a new integrated operational policy (OP 10.00).Footnote49 At the heart of this ‘modernization’ was the endorsement of a ‘risk-based approach for investment lending’ and a shift from a ‘rule-based’ operational process to a culture of ‘informed risk-taking’.Footnote50 Not only did the Bank need to measure and manage ‘risk’ with more conviction and awareness, the organisation also needed to ‘help [its] client countries to strengthen their own risk management systems’.Footnote51

The shift from a ‘rules-based’ paradigm (where concerns regarding mandate, political interference or legal competence pivot centrally) to the ‘principles-based’ operational template of analytical country diagnostics and risk-management techniques, aligns with the emergence of a ‘risk commonwealth’Footnote52 in public governance more broadly. For Leroy, who had built out a career in public sector reform this register came naturally: risk management, not international law, had been her bread and butter.Footnote53 This managerial reform did not only have an impact on the design of the Bank’s lending instruments and procedures (as explored above), but also impacted both the processes of enacting and legitimising the organisation’s internal accountability standards that were altered (or dissolved). As an example of the latter aspect, Leroy’s essay refers to the organisation’s new ‘Environmental and Social Framework’.Footnote54 ‘A key feature of the new framework’, she observes, ‘will be a risk assessment approach … a measured shift towards the mitigation and management of risks’.Footnote55 Indeed, the key change in the environmental and social safeguards lies not in the minor substantive extensions to previously disregarded policy domains or in the ambiguous references to international (human rights) law but in the shift from ex ante deontic standards to a process of downstream contextual assessment and continuous managerial modification. The prescriptive ex ante evaluation of projects based on formal normative criteria is thereby traded for a process of ‘adaptive [risk] management’ based on ‘downstream monitoring and implementation support’.Footnote56 Reflecting on these changes in the Bank’s lending instruments and in the changing contours of its accountability standards, Leroy concluded that ‘[t]he leitmotiv of all these initiatives undergirding the construction of a ‘Solutions Bank’ is clear’:Footnote57 the Bank, she asserted, had taken a decisive turn toward ‘more agile [and] less regulated decision-making based on informed risk-taking’.Footnote58 These broad-sweeping managerial changes clearly called for a particular mode of lawyering associated with a new institutional toolkit of risk management.

‘Taking on the technicalities’Footnote59 – the institutional toolkit of un-governance

In a section of the legal opinion titled Managing Risks of Political Interference, Leroy introduces new risk templates and typologies,Footnote60 tools of probability calculus and cost–benefit analysis, and a ‘special review’ mechanism aimed at iterative risk ‘monitoring’.Footnote61 The prohibitive posture of lawyering is to be traded, the opinion elaborates, for a ‘series of measures aimed at analysing the risks [of political interference] and managing them’.Footnote62 This new ‘analytical framework’ – as Leroy describes it – discards the ‘binary logic’ of the ‘traditional’ legal posture (never constituting a formal act of judgment), and operates on the basis of a ‘spectrum’ of ‘risk categories’,Footnote63 each associated with ‘mitigation measures as well as capacity-building activities to address those risks’.Footnote64 The reference to such ‘capacity-building activities’ in this central ‘tool’ of the new ‘risk-based approach’ signals how the embrace of this new logic not only impacts the institution’s internal decision-making processes (including processes of legal interpretation and legal evaluation) but also its envisaged mode of institutional reform, which now increasingly focuses on enhancing the local capacities for risk resilience. Both the identification and qualification of ‘risks’ and the enactment of productive coping strategies and capacity building projects forms part of a flexible and adaptive learning process that we identify with the wellness guru.

Since many lawyers in the World Bank were unfamiliar with this methodology (or considered it to be ‘unlawyerly’),Footnote65 Leroy distributed a Staff Guidance Note. Its purpose was announced as follows:

[t]his note does not set out a prescriptive set of instructions but provides guidance for Bank staff on how to analyse whether an [involvement in the criminal justice sector] is appropriate for the Bank to engage in, how to assess the risks involved, and how to develop a risk-taking and management strategy.Footnote66

The stated purpose of ORAF explicitly disavows normativity: it is ‘there to help’ teams in calculating and containing contingencies that can hamper the achievement of their PDOs.Footnote74 The ruling rationality of the risk-based operational toolkit is entrepreneurial: the guiding concern is the ‘achievement of the project’s results’, and ‘risk ratings’ are attributed on the basis of the ‘impact of the risk’ on these results and the ‘probability that the risk will occur’.Footnote75 The routine of risk management thereby provides modes of calculation and adaptation oriented towards value-enhancing, competitive behaviour – the ‘risk appetite’ demanded by senior management – and the promotion of economic rationality. Foucault's epithet, ‘live dangerously’, applies here as the motto of a managerial toolkit occupied less with ‘threat and loss’ than with ‘gain and profit’.Footnote76 This logic resonates also in Leroy’s defence of her ‘paradigm shift’: while engagement with the criminal justice sector ‘pos[es] considerable risks’, she argues, it ‘also promise[s] transformational rewards’.Footnote77 The productive logic embedded in this shift from ‘rules’ to ‘principles’ is further elucidated in Leroy’s introduction of a probability-based cost–benefit calculus aimed at ‘weighing the residual risks against anticipated benefits’,Footnote78 as well as the integration of the ‘risk of absence’: it would make ‘strategic sense’, Leroy’s Staff Guidance Note states, if the World Bank would also weigh the ‘risk of not acting’, the risk of missing out, against ‘risks [of] political interference’ involved in ‘undertaking action in the criminal justice system’.Footnote79

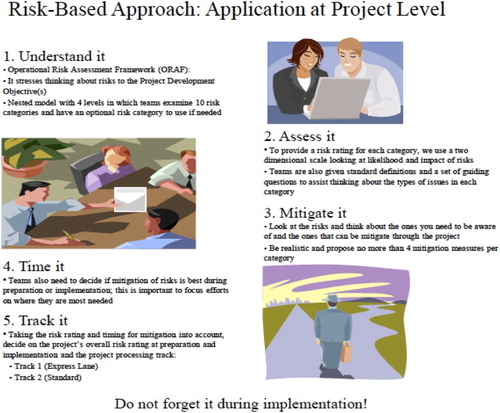

To facilitate the risk-based approach, which provides the model for Leroy’s ‘paradigm shift’ in legal practice, ORAF provides a ‘risk assessment template’;Footnote80 an online ‘risk portal’ for virtual adaptation at the project level; visual heuristics for management training (cf ); ‘rule[s] of thumb’ for risk management measures;Footnote81 a ‘roadmap’ for risk evaluation;Footnote82 ‘guiding questions’ for risk assessment;Footnote83 and detailed allocations of roles and responsibilities in the ‘dynamic process’ of risk management.Footnote84 In interlinking legal decision-making with this managerial framework of risk assessment, Leroy’s ‘new normative architecture’ now reconfigures and reduces the role of the lawyer to her ‘participation … in the [project] team discussions [on] the PCN [Project Concept Note] risk ratings’.Footnote85 This shift in the role of the lawyer is also explicit in the ‘special review process’ that was introduced by Leroy’s legal opinion and guidance note.Footnote86 To ensure that ‘all relevant risks are carefully analysed and appropriate … risk management measures [are] identified’,Footnote87 Leroy noted that the creation of a new ‘mechanism to provide task teams with expert guidance in this new and risky area … appear[ed] warranted’.Footnote88 To this end, the self-proclaimed ‘paradigm shift’ in legal practice enacted by Leroy was accompanied by the creation of a new institutional mechanism: the Criminal Justice Resource Group (CJRG). This CJRG, Leroy set out, would need to be involved in the planning of all ‘high risk’ projects, where it would provide ‘expert analysis of risk and the identification of potential safeguards and risk management measures’.Footnote89 The guidance note (as well as the legal opinion) stipulates that the key normative concern of the CJRG is not the legality of proposed projects, but the operational and ‘reputational’ risks for the World Bank.Footnote90 The composition of the CJRG equally signals a relative displacement of legal authority as it is

expanded to include experts from across the Bank in areas such as justice reform, crime and violence prevention, environmental crimes, risk management, urban planning, youth development, gender, stolen asset recovery, anti-money laundering, and assistance to fragile and conflict-affected states, as well as the relevant Regional staff and OPCS [Operations Policy and Country Services].Footnote91

Figure 1. A visual heuristic for the risk-based approach (ORAF).Footnote167

The emergence of risk-management as a productive encounter with uncertainty is less the product of consciously planned attempts to overcome or accommodate the impossibility of closure, than it is an effort to capitalise on it by means of institutional arrangements of unsettlement and reconfiguration determined by adaptive managerial diagnostics and institutional templates. ORAF explains that

[r]isk assessment is a dynamic process starting with preparation and continuing through implementation. This assessment will help to continuously monitor the evolution of risks; to identify the emergence of new risks; to assess progress with, and impact of the implementation of risk management measures; and, as necessary, to devise appropriate adjustments to support to achievement of the project’s results.Footnote92

‘The role of the lawyer in the solutions bank’Footnote99 – risk as productive professional practice

The qualification of this institutional technique as a provisional, material assemblage enacted through mundane professional practices helps to appreciate the performative and productive nature of the risk-based governance tools. The ‘risk scores’ that serve as focal points in Leroy’s ‘new normative architecture’ do not (purport to) serve as unmediated representation of external phenomena to be acted upon, but serve as thoroughly artificial heuristics allowing the organisation to move beyond the impossibility of closure in a productive manner. It is through these iterative and adaptive practices of assessment, mitigation and management itself that risk artefacts gradually coagulate and form effects in stable networks of institutional practice.Footnote100 ‘Risk’, Dillon generally observes, ‘is a carefully crafted artefact [and] does not exist “out there”, independent … of the computational and discursive practices that constitute specific risks as the risks that they are … Risks are thus created, circulated, proliferated and capitalized upon’.Footnote101 The direct relationship between ‘risk assessment’ and ‘capacity-building activities’ in the ORAF further signals how the embrace of this new technology not only impacts the ‘paradigm’, ‘analytical framework’ or ‘normative architecture’ of legal evaluation in the World Bank, but also its envisaged mode of governance reform (focused now on enhancing immanent capacities of risk resilience).Footnote102 For projects in contentious operational domains (such as the security sector), the ORAF provides novel bureaucratic tools for designing ‘capacity-building activities’ in the client state; evaluating ‘whether or not to go forward’ with the operation and ‘deciding on the processing speed’ of the project in the World Bank’s transactional machinery. ‘Some measures’, the ORAF indicates, ‘may go beyond mitigation to also include capacity building and system enhancements to reduce the risks not only for the duration of the operation but also to prepare the borrower for better dealing with such risks following the conclusion of the operation’.Footnote103 Yet, the ORAF explicitly denies that its risk-based diagnosis and ‘capacity-building’ would thereby constitute an evaluative, political enterprise: ‘[c]lients … should understand that the Bank uses risk ratings to make decisions as to best support [them] and is not making value judgments or ranking countries’.Footnote104 The governmental logic of risk unfolds in an agnostic register, outside normative premises of liberal interventionism.Footnote105

To conclude, by framing the institution’s contentious operational expansion into the field of security sector reform as a matter of ‘manageable risk’, Leroy’s Legal Memorandum and Staff Guidance Note envisaged a ‘paradigm shift’ in legal practice where ‘boundaries’ are traded for ‘risk categories’ and ‘prohibitions’ for ‘management strategies’.Footnote106 This, she understood, called for both the introduction of novel evaluative tools (such as the ‘live instrument’ of the ORAF)Footnote107 and the cultivation of an altered professional sensibility oriented towards an adaptive attunement to insecurity and complexity. This calculative, risk-oriented logic, Leroy claimed, ‘lays the groundwork’ for a radically new ‘paradigm for the future role of Bank lawyers in dealing with Articles’ interpretation’.Footnote108 This was her response to the perceived need to ‘rethink the traditional role played by lawyers in the Bank’ and the expressed conviction that ‘the legal [department] continues to play a central role’.Footnote109 The institutional ‘shift from risk avoidance to risk management, and from bright rules to broad principles’, Leroy held, ‘need not spell the end of the lawyers’ role in … interpretation or in any other aspect of the Bank’s work’.Footnote110

The assemblage of risk management tools and templates developed elsewhere in the World Bank’s operational segments was now put forward as the more opportune and robust mode of legal practice and, thereby, displaced the ‘old’ language, argumentative practice and professional sensibility of international law(yering) as it had previously been embodied within the organisation. In its practical manifestation, this ‘new normative architecture’ of risk management signals both the displacement of the oedipal figure by the wellness guru and the concomitant emergence of a type of institutional practice displaying a ‘simultaneous commitment to closure and its impossibility’.Footnote111 Leroy’s ‘paradigm shift’ was oriented at orchestrating action despite uncertainty regarding foundational questions on the limits of institutional authority and the nature of political interference. These formal concerns, which had been central to the authority associated with the oedipal figure, were displaced by holding devices and management tools aimed at coping with (and capitalising on) this open-endedness and contingency. The move from the oedipal figure to the wellness guru thereby reflects a move towards an adaptive, calculative and utilitarian logic grounded in particular material technologies of seeing, reasoning and acting and attuned to the central tenets of the move to un-governance.Footnote112 Our analysis above has explored this ‘embrace of risk’ as both a set of novel evaluative tools and heuristics as well as the cultivation of a particular (flexible, adaptive) professional sensibility attuned to uncertainty. This turn was rendered visible not only in formal legal decisions but also in operational toolkits, managerial manifestos, visual heuristics, task team compositions and risk management templates.

Un-governing through contingency and self-denial – the rationality of resilience

The foregoing changes in its ‘normative architecture’ enabled the World Bank’s engagement with the security sector of states and with matters of violence and conflict. In this field, new operational models and toolkits were deployed for coping with violence and rationalising socio-political adaptation, in sharp differentiation from the World Bank’s earlier practices of institutional reform. Aligning with the articulated features of un-governance, these new models propose to operate through rather than against unknowability, agnosticism and contingency with adaptive, mutable, open-ended and data-driven attempts at enhancing the resilience of local communities. These transformations entail altered modes of knowing and seeing;Footnote113 a more radical decentring of sovereign sites of authority as essential vectors of reform; and practices of both detection and intervention aimed at capturing and capitalising the immanent and emergent surplus of life formerly situated outside the architectonics of institutional reform. Throughout the World Bank, however, these models were less the result of conscious design and more the result of improvisational, experimental techniques and toolkits – dispersing authority across the staff, rather than consolidating it around a central figure or plan.

The World Bank’s 2011 World Development Report (WDR) on Conflict, Security and Development is exemplary here. While previous versions of the institution’s flagship publication consistently provide models for an ideal institutional configuration for development (leaving space, of course, for modification of institutional transplants to specific local contexts),Footnote114 the 2011 WDR is surprisingly agnostic when it comes to matters of policy guidance. It underlines on multiple occasions that ‘there is no “one path”’ to prosperity and security in the development process.Footnote115 ‘Institutions do not need to converge on Western models’, the report stipulates, ‘local adaptation is best’.Footnote116 Rather than putting forward ideal types or best practices, the mantra of the adopted paradigm is that violence is ‘complex, diverse and diffuse’ and needs to be counteracted by continuous adaptation and homeopathic forms of policy intervention on the level of ‘local institutions’.Footnote117 Violence and poverty are qualified as immanent ‘risks’ for every society that need to be coped with by ‘resilient’ institutions.Footnote118 The model, thereby, trades familiar ‘cause-and-effect’ interventions, grounded in moral or epistemic universals, for iterative, process-based, open-ended and never-ending cycles of policy intervention that work with (rather than against) complexity in an attempt to improve a society’s own capacity to manage risk and stress resiliently.Footnote119

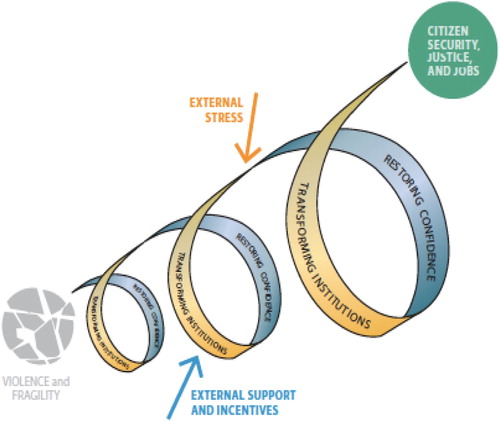

This resilience-based logic clearly differs from recognisable rationalist attempts to bridge knowledge gaps between global projects and local sites of reform: in the turn to immanence, the vector of social change is now inversed. The surplus of life – the externalities and complexities that defy legibility in rationalist registers of reform – are no longer impediments to be overcome but immanent energies to be enrolled and capitalised on.Footnote120 This transformation is apparent in the visual representation of the resilience framework in the WDR, as referred to above and reproduced at . The shift from intervention at the level of causation to intervention at the level of resilience is represented here with remarkable optical and metaphorical precision. Expressive of the immanent ontology of the resilience paradigm, the WDR elaborates that the ‘framework is graphically represented as a spiral, because these processes repeat over time as countries go through successive transition moments’.Footnote121 ‘Even as one set of immediate priorities is resolved’, the report observes, ‘other risks and transition moments emerge and require a repeated cycle of action to bolster institutional resilience to stress’.Footnote122 At the heart of this model is the assertion that ‘[b]uilding resilience to violence and fragility is a nationally owned process’, and that ‘external support and incentives’ can only ‘contribute to progress’ insofar as they engage with, enrol and stimulate ‘local organic processes’.Footnote123 The enhancement of autonomous capacities of resilience at a local level, in this sense, is operationalised through unscripted processes of learning and adaptation. The focus on endless, circular iteration (as reflected in the spiral) as well as the inversion of the vector of reform (from the local pointing upwards) signal how this form of un-governance reconfigures the orthodox temporal and spatial coordinates of institution-building.Footnote124 The topographies and temporalities of this reformist project are provisional, open-ended and mediated by mundane material practices of trial, translation and learning. The local thereby appears as an always inaccessible yet pivotal normative repository for the global.Footnote125 The endpoint is always only a moment of reorientation (in potentially different directions) en route to ever more of the same. The time and space of reform are (re)organised in the relational practices of resilience themselves.

Figure 2. The WDR framework: building resilience to violence.Footnote168

‘The political economy of reform and risk’Footnote126

The governance strategy associated with WDR 2011 states that the World Bank no longer promotes ‘presumed solutions based on institutional and organizational forms [enacted] elsewhere’.Footnote127 Rather, informed by the ‘political economy of reform and risk’, the strategy claims to provide a new ‘problem-solving approach’ that relies on continuous, open-ended cycles of diagnosis and tailored intervention, without ‘assumptions about the ideal form a judicial system should take’.Footnote128 In this strategy, ‘the use and strengthening of developing countries’ systems is central’.Footnote129 The legal department’s companion piece is even more explicit in its agnosticism and its rejection of universalist policy models: ‘it should be clear that the Bank does not have a blueprint for success in justice reform’, the piece states, which calls for a ‘problem-solving and empirically based approach … rather than the establishment of what are identified in advance as the “right” institutions and rules’.Footnote130 New policy ‘models and approaches’ are called for in this open-ended process of problem-solving, such as the identification of ‘flagship justice reform initiatives as sites of learning and innovation’.Footnote131 Rather than seeking to overcome the knowledge gaps associated with social complexity by developing updated policy templates, these tools embrace the radical contingency of society and seek to govern through and with contingency via open-ended and adaptable practices of ‘problem-solving’ that aim at fostering risk resilience at the level of the population. The ‘political economy of reform and risk’, in short, does not provide ‘pre-set goals’ but entails ‘the careful management or modulation of interactions to attempt to balance and ease the strains of adaptation as an ongoing process’.Footnote132 It thereby forms a pivotal element in the turn to ‘un-governance’ within the World Bank.

This shift from the old cause-and-effect ideals of liberal interventionism to practices of (not) knowing and acting associated with resilience was closely linked with new technological assemblages at and including the World Bank.Footnote133 The implementation, adaptation and appraisal of projects designed to amplify resilience at the (always contingent and unknown) ‘local’ level, relies on the continuous influx of digital data and diagnostics. Capacity-building and resilience interventions, the governance strategy noted, required new ‘diagnostic tools’ to ‘improve the assessment of country systems’ as elements of a ‘national capacity building strategy’.Footnote134 The legal vice presidency’s companion piece equally urges that ‘[s]trong diagnostics should inform the design of interventions by providing data on the actual functions of the justice system, the political economy of reform and its risks, and the way potential reforms might translate into progress towards justice’.Footnote135 Both operational documents, therefore, articulate calls to expand the World Bank’s data-gathering infrastructure and diagnostic capacities.Footnote136 Importantly, this new infrastructure for data analytics was not only needed within the World Bank but also within these ‘local’ sites themselves. Consequently, the reform ‘process’, the companion piece states, supports the ‘national capacity for data collection’ considered necessary for ‘cross-country learning and collaboration’.Footnote137 If ‘local’ actors or spaces of governance are to be made resilient through iterative and open-ended process of reform, they would need to be seen, measured and mapped. This enormous flow of data is not (or at least not exclusively) processed through pre-existing schemes of interpretation and policy action, however, but also produces new forms of policy design, learning and implementation.Footnote138 The very point of these interventions often emerges only in dialogue with data analytics (a point no longer expressed in terms of ‘right institutions’ but emanating from the ‘needs of end users’).Footnote139 Continuous contextual data, in other words, is what materially ties the governmental assemblage of action-despite-agnosticism in the sphere of justice reform together.Footnote140 It is the energy of an unscripted, immanent mode of intervention.Footnote141

One World Bank project – the Honduras Safer Municipalities Project – reveals the contours of this risk-resilience assemblage and the way in which its various technical, material and conceptual components are brought together in a particularly powerful way. In line with the expression of un-governance mapped out above, the project’s stated objective is to enhance the ‘resilience of communities to address key risk factors of violence’.Footnote142 The attempt to enhance capacities of resilience at the local level is embedded in an ‘integrated approach to violence prevention’, which addresses all ‘risk factors that increase the likelihood of a person to become either a victim or perpetrator of violence’ through ‘multiple, coordinated interventions and activities, whether at the individual, family, peer, community or societal level’.Footnote143 In a remarkable expression of the resilience paradigm, the project states that it will therefore ‘use the ecological risk model developed by the WHO to identify and target key risk factors related to violence’.Footnote144 It is the language of immunology and adaptation – not intervention and transplantation – that structures this ideal of governance reform. To orchestrate these localised, iterative and wide-ranging reform projects – generating resilience through ‘the family, the school and the community’ – the project primarily aims at building a complex data infrastructure: the ‘provision of technical assistance and acquisition of equipment to enhance the National Violence Observatory’ and the ‘strengthening of municipal crime and violence observatories’ are central to the spiral-like learning process of resilience, which relies on a continuous flow of ‘localised’ knowledge and data.Footnote145

With the turn to resilience, the state as a privileged international legal subject and an insulated sphere of authority is decentred, and the focus shifts to materially observable and legible aspects of life trained for resilience (the ‘family, school and community’). The episteme of this governmental logic is not the mechanical Enlightenment ideal of causality that underpinned the grand narratives of liberal internationalism. The change is predicated instead on a biophysical vocabulary of autoimmunisation and adaptation emerging from various management, organisational, and social science disciplines – touching on fields like systems theory, cybernetics and ecological sustainability. It no longer commits to policy transplants or scripted techniques for problem-solving, but provides coping strategies for self-empowerment, resilience and risk-management in emergent, complex and contingent processes in which violence and deprivation are engendered. More abstractly, this epistemological rupture can be qualified as a departure from orthodox architectonics of sovereign reform towards Foucauldian notions of governmentality. In the latter sense, these transformations can then also be situated in the longer genealogy of attempts to register and enrol the surplus of life, the externalities of modernity, that always escape governance. In this sense, we argue, as expression of un-governance, resilience signals not a suspension but an acceleration of a material mode of governing under conditions of unending competition for its own sake. As with other developments in the genealogy, it represents a moment of material, historical transformation, but simultaneously exhibits elements of continuity with the apparatuses out of which it has developed. Un-governance, as investigated in this special issue, captures the element of pivotal transformation in the move to appropriate the surplus of life as a source of power in the conduct of the population. By the same token, however, the ever-more-granular dispersion of adaptive techniques tailored to the productivity of the population represents continuity, especially insofar as it reflects an extension of economic rationality predicated on myriad individualised material situations. Both these elements, change and continuity, are characteristic of a temporal social order defined by competition without end, driving a race for material change in an unending pursuit of ever-greater production. They are characteristic of a singular regime’s escalating attempts to capture an uncapturable surplus of life.

Productive practices in a time of endless competition

Behind the adaptive immediacy associated with the institutional changes described in the preceding sections lie two things that we observe in Foucauldian terms of governmentality: (1) a technology of risk assembled in practice on the basis of an economic appreciation for contingency and emergence, such as in Leroy’s ‘new normative framework’; and prior even to that, (2) a temporal condition (along the lines of a dispositif in the Foucauldian vocabulary) populated by myriad subjects interacting transactionally in a state of competition without end or object beyond sustaining competitive, transactional relationships. The temporal order associated with endless competition is bound up with an historical move away from the universal and teleological orders that preceded the modern political economics of the secular interstate system. Competition and economic self-interest replaced classical empire and imperial ambition.Footnote146 We also, by proposing the metaphors of Oedipus and a wellness guru, incorporated a Lacanian psychoanalytic vocabulary in our analysis, one applicable to the normative significance of law in this context by virtue of being specifically trained on a central lack around which identity and action are organised and regulated.Footnote147 This vocabulary helps to analyse the work done by and with gaps in knowledge systems inside enterprises of international law and global governance, and the institutional work done despite an impossibility of closure.

In making sense of these practices, we therefore draw on Foucault’s work to situate un-governance practices in the temporal and historical frame he established for governmentality, while drawing on the Lacanian vocabulary as the basis for a (non-historicist) assessment of the development of un-governance practices in that frame of governmentality over time. Foucault, in his overall genealogy of rational governance techniques, observes a move from disciplinary and state-oriented governance (identified with raison d’etat) to a different sort of governmentality keyed to population, or the diversity of individuals constituting all together the object and subject of political power in modern, secular social relations.Footnote148 The change over time is bound up with the dispositif mentioned above, featuring an embrace of economic rationality for competitive production, production without greater object or end other than the sustenance of more production under competitive circumstances.Footnote149 This condition might be visualised as a spiral, moving in circles without end but always escalating towards a particular direction (ie, heightened competition). Such a figure of the spiral has been used for un-governance purposes by the World Bank, as reproduced above at . It is also the figure of a peculiar political economy of self-affirming subjects interacting on a competitive, transactional basis, resulting in ever greater production but without any other apparently unifying teleology.Footnote150

The emphasis on the productivity of the population prompts a move away from a consolidated centre of disciplinary command associated with the state, towards dispersed technologies predicated not (or no longer primarily) on discipline, but on profiting from the competitive potential of a population in its diversity. That shift over time includes the development of materialised law intended to maximise the productive capacity of the population, by maximising the productive powers of the individuals it comprises in transactional networks. The change marks a move away from imposed rational plans and towards opportunistic responses to dynamic conditions, much as the new direction at the World Bank that we describe diminished reliance on pre-set models in favour of adaptive agency. In the historical context described by Foucault, disciplinary domination could not over time adequately account for the contingent possibilities of dynamic conditions that are inherent in the population. Under conditions of constantly escalating competition, the closure sought by discipline alone was too restrictive.Footnote151 Governmentality, trained on instrumentalising the diverse competitive potentialities of a population, surpassed disciplinary domination (though did not abandon it) with a more process-based, resilience-oriented mode of governance, less vulnerable to contingencies, one more conducive to thriving under competitive conditions.

As a result, the locus of authority moves from diminished central points of consolidated interest and control to still more dispersed technologies operating according to the contingent situation(s) of the population – a process associated with a decentring of sites of authority and an appropriation of ever-expanding productive dimensions of social life. As a means of practical governance, imposed planning becomes apparently less efficacious than opportunistic responses to dynamics emergent in the population itself. But even the population-based governmental programme that capitalises on contingency reaches its productive limit in the phenomenon identified by Foucault as the surplus of life. The surplus of life, however, is a strange sort of limit. It is not an object, but a condition of escape that always frustrates governing structures of power at their margins.Footnote152 And because it describes a condition of perpetual escape, the surplus of life represents a limit that is constantly receding. This is the sort of limit that is produced by the underlying temporal condition (the dispositif) of constantly escalating competition without end. The surplus of life is the failure to reach a final point of ultimate productivity, the impossibility of its closure, which makes the surplus of life also the horizon of possibility for ever more competitive performance.

As described by the editors in their introduction to this special issue, un-governance introduces a new governmental practice into this situation, one which in our framework now appears as logical as it does paradoxical: namely, embracing the impossibility of closure to advance the impossible pursuit of closure. And here the Lacanian insight is key to assessing the contemporary situation of institutions pursuing closure by embracing the impossibility of closure: the embrace of the impossibility of closure can be analysed according to the very urge towards closure with which it conflicts.Footnote153

Risk in the register of enjoyment

Key to the developments described here has been the adoption and refinement of risk as a technology of governance. As we instantiated with reference to institutional innovations at the World Bank, risk constitutes a material mode of governing that diminishes law’s prohibitive parameters to capitalise on contingency and the impossibility of closure. Risk today includes particular technologies that go beyond risk technologies of just a few years ago. Whereas risk technologies have traditionally been deployed prophylactically, following insurance models, today they are deployed opportunistically, as speculation, more in keeping with practices associated with the world of finance.Footnote154 In this specific historical context, risk technologies produce an equally specific sort of resilience, more closely linked with thriving than with enduring.Footnote155 This combination of speculation and thriving calls for one last Lacanian term, but which is also a quotidian one, namely enjoyment.Footnote156 The specific phenomena of risk and resilience at work in this story demonstrate the political valence of enjoyment under the historical and material conditions of competition today. The connection between risk and enjoyment is already apparent in the regular identification of risk technologies with gambling.Footnote157 As read through Žižek, ‘Lacan’s fundamental thesis is that superego in its most fundamental dimension is an injunction to enjoyment: the various forms of superego commands are nothing but variations of the same motif: “Enjoy!”’ By this reading, gambling becomes obligatory, even as it remains distinct from the legal mandate:

Law is the agency of prohibition which regulates the distribution of enjoyment on the basis of a common, shared renunciation … whereas superego marks a point at which permitted enjoyment, freedom-to-enjoy, is reversed into obligation to enjoy – which, one must add, is the most effective way to block access to enjoyment.Footnote158

But gambling has been the frustrating pursuit of enjoyment throughout a variety of historical and material conditions. The question becomes: why does gambling take the form of a governmental technology now? With this question, we echo what is asked in the introduction to this special issue: why now? Consider in this light the economic analysis of Mariana Mazzucato. She details how the historical field of political economy was surpassed by the narrower discipline of economy, which turned in the process from objective measures of value (such as a labour theory of value as measured by the amount of labour necessary to produce a commodity) to subjective ones (especially the theory of marginal utility as measured by price, or what so many individual customers are willing to pay for something).Footnote161 This subjective shift in economic reason dovetails with the elevation of the individual, or the abstracted individual engaged at the scale of the transacting population. And as Mazzucato makes clear, it establishes the possibility of comprehending material value creation in purely speculative exercises that produce no new goods.Footnote162 The washing machine has a value measured in price, as does the packaging and repackaging of debt accrued in the purchase of the washing machine, or a bet on the likelihood that the repackaged debt will be worth more or less over time. Under mainstream, marginal utility (or equilibrium) economic theory, the achievement of value objectively becomes indistinguishable from possibilities of gain by speculative wager. The enjoyment of gambling thereby becomes socially useful, elevating its performance in the register of risk to a level appropriate to governance. But more than useful, it becomes socially necessary, as constant conditions of always-intensifying competition ensure that every next opportunity must be capitalised on. Indeed, as Leroy argued, the new risk calculus needs to include the ‘risk of not acting’ – the risk of missing out.

In other words, survival is no longer an issue of guarding against contingency, but the competitive requirement to exploit it. And so, risk not only secures against the contingent, à la insurance in its classical form, risk also capitalises on the contingent, for instance in the forms of finance associated with speculation. The financial derivative, pervasive in the contemporary transnational economy even since the global crash occasioned by the instrument, is supposed to do both of these things at once, delivering surplus profit while distributing the costs of failure. The same spirit of resilience-with-profit was apparent above in the promise of ‘transformational rewards’ attendant on the embrace of risk-management in the legal practices of the World Bank. More than anything else, as Dillon has observed elsewhere, risk technologies ‘provide opportunity for gain or they compensate people [and things] for any loss they may incur, allowing them to continue to actively circulate in the general combinatorial and transactional economy of contingency’ in the first place.Footnote163 Yet, to say that risk technologies allow activity is misleading: the interlacing of legal regimes, financial instruments and insurance practices, among other things, work together to enable and ensure activity, whether to minimise negative exposure or to maintain profit and growth in an endlessly competitive environment, one metastasised today by predictive technologies capable of extracting and deploying massive amounts of data to extend the scale and scope of speculative, risk-oriented performance for governance (and other) purposes. In short, risk is constitutive of institutional participation today in the endless competition that materially defines contemporary subjects in their interrelations.

Conclusion: un-governance and critique

We indicated earlier that we intend to contribute to a new mode of critique suited to some of the distinct features that we associate with un-governance.Footnote164 Specifically, we are interested in a mode of critique attuned to the productive performativity of this new mode of governance.Footnote165 We are not especially interested in the failure of un-governance practices to ‘live up’ to any representational figure or promise. In part, this is because we are not much convinced that un-governance actors are much interested any more in representing any idealistic promise. Idealism figures into our two empirical threads at the World Bank only in connection with Shihata, the embodiment of our oedipal figure, who described a line between law and politics that the World Bank’s legal counsel was bound by mandate not to cross. That representation operated as a sort of constitutional (and constitutive) limit, an ideal-type boundary mark projected back into the identity of the legal counsel to define (and delimit) its practice.Footnote166 It also provided an object for critique. Leroy’s legal counsel, however, does not maintain that ideal boundary mark, nor the professional identity that it supports. Under Leroy, the World Bank’s legal counsel is an opportunistic one, trained on and for resilience and productivity, unbound from Shihata’s defining prohibition. To be clear: by opportunistic, we do not mean (to be) cynical. And that is the point. Leroy’s legal counsel is the wellness guru, aiming at vitality rather than disciplinary identity. In this mode, it is adaptive, resilient and productive, full stop. And it is resilient-productive (productive of and for resilience) as part of a remarkable new development in a condition of governance that calls for competitive productivity without any objects or ends beyond competitive productivity itself. This development is what we associate with un-governance, in which there is diminished adherence to or deployment of a false ideal(ism), diminished reliance on representations to be failed in practice, but also diminished identification of or with any unitary purpose.

The pursuit of closure persists, as it must in a condition of ever more competition, because without the gesture of intended closure – the ambition to win and not lose – the competitive pursuit collapses. But now it includes an embrace of the impossibility of closure, the receding horizon that sustains the perpetual competition in the first place. As a result, there remains only the productivity, in a pressurised system that drives ever greater productivity, and it is on this performance that we mean to train our critique. With our contribution to this special issue, we have proposed a particular framework by which to make specific institutional aspects of un-governance legible in historical context. We have instantiated that framework and those institutional aspects with two developments at the World Bank. Comprehending the productive reality of these practices has been our primary goal here, to enable further critical investigation into their possibilities and discontents going forward.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Andrew, Deval and the participants at the Ungovernance workshop for the opportunity to develop this work together.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Deval Desai and Andrew Lang, ‘Introduction: Global Un-governance’ (2020) Transnational Legal Theory (this issue).

2 Ibid

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

5 We are not, for example, performing Sloterdijk’s critique of cynical reason. See Peter Sloterdijk, Critique of Cynical Reason (University of Minnesota Press, 1988).

6 It can be found in work from Kelsen’s grundnorm to Derrida’s foundational violence, and points beyond and in between. Hans Kelsen, Pure Theory of Law (University of California Press, 1960); Jacques Derrida, ‘Force of Law: “The Mystical Foundation of Authority”’ in Drucilla Cornell, Michel Rosenfeld, and David Gray Carlson (eds), Deconstruction and the Possibility of Justice (Routledge, 1992).

7 We use here a Lacanian psychoanalytic vocabulary that comes by way of Žižek, drawing principally on Slavoj Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do: Enjoyment as a Political Factor (Verso, 2002).

8 Žižek (n 7) 266; cf, Jacques Lacan, ‘A Theoretical Introduction to the Functions of Psychoanalysis in Criminology’, in Jacques Lacan (ed), Écrits (WW Norton and Company, 2006).

9 Žižek (n 7) 266.

10 In its embrace of uncertainty as productive possibility, the image of the wellness guru intersects with other psychological prototypes in literature (particularly in relation to the entrepreneurial embrace of risk). Knight’s classic text, for example, refers to the figure of the ‘adventurer’ – a figure traditionally associated with corporate life. Yet, with Amoore, we see an extension of this ‘adventuring spirit’ in current practices of (un-)governance where ‘the unknowable environment is to be embraced, positively invited, for its intrinsic possibilities’. See Frank Knight, Risk, Uncertainty and Profit (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1921) 311; Louise Amoore, The Politics of Possibility (Duke University Press, 2013) 10.

11 This corresponds with Foucault’s dichotomy between the sovereign (the oedipal figure) ‘who can say no to any individual’s desire’ and the ‘economic-political thought of the physiocrats’ for whom the ‘problem is how they can say yes to this desire’ by finding ways to ‘live dangerously’ amid the ever emergent and unpredictable externalities of life. In Michel Foucault, The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). Latour refers to this as the attunement to the ‘externalities of modernity’. See Bruno Latour, ‘Is Re-modernization Occurring—And If So, How to Prove It?: A Commentary on Ulrich Beck’ (2003) 20(2) Theory, Culture & Society 35.

12 Michel Foucault, Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the Collège de France 1977–1978 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009).

13 See David Chandler, Ontopolitics in the Anthropocene: An Introduction to Mapping, Sensing and Hacking (Routledge, 2018) 37. Chandler describes this as a shift from modernist modes of reform to the ‘ontopolitics of mapping’. In a way that perfectly resonates with the World Bank’s turn to resilience explored below, Chandler describes the mode of governance of ‘mapping’ as a form of ‘systemic adaptation to emergent social, economic and environmental conditions’. This differs from the ‘linear problem of optimizing scarce resources’. Ibid, 50

14 Desai and Lang (n 1).

15 Fleur Johns, ‘From Planning to Prototypes: New Ways of Seeing like a State’ (2019) 82(5) Modern Law Review 833. Johns focuses on new ‘styles’ of governance more attuned to inferential sensing than comprehensive knowing.

16 This aligns with the analysis of Duffield, who qualifies new infrastructures of data connectivity as essential for the functioning and acceleration of global security governance, which he places in a longer genealogy of liberal rule. See Mark Duffield, ‘The Resilience of the Ruins: Towards a Critique of Digital Humanitarianism’ (2016) 4(3) Resilience: International Politics, Practices and Discourses 165 (‘[T]he development-security nexus has pivoted from the ground into the volumetric and vertical dimensions of a buccaneering digital atmosphere’).

17 We refer to the ‘surplus of life’ in Foucauldian terms as the multiplicity of emergent social elements that escape productive incorporation in institutional programmes. In Foucault (n 12). From the perspective of object-oriented ontology, ‘this surplus is not something that … lurks beneath the human symbolic order, as in Lacan’s … sense of “the Real,” but is always a form that can never be fully translated into any set of relations’. Graham Harman, ‘The Only Exit From Modern Philosophy’ (2020) 3(1) Open Philosophy 143.

18 We are inspired here by work that places the embrace of resilience in a longer lineage of governmentality. See Jessica Schmidt, ‘Intuitively Neoliberal? Towards a Critical Understanding of Resilience Governance’ (2015) 21(2) European Journal of International Relations 402; Jeremy Walker and Melinda Cooper, ‘Genealogies of Resilience: From Systems Ecology to the Political Economy of Crisis Adaptation’ (2011) 42(2) Security Dialogue 143; David Chandler, ‘Beyond Neoliberalism: Resilience, the New Art of Governing Complexity’ (2014) 2(1) Resilience: International Politics, Practices and Discourses 47, 47 (arguing that, in contrast to ‘actually existing neoliberalism’, ‘resilience asserts a flatter ontology of interactive emergence’).

19 In Lacanian terms, we describe Oedipus as point de capiton. See Žižek (n 7) 16–27; Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (Verso, 1989) 109ff.

20 Cf. Žižek (n 7) 31–34.

21 Ibid, 16–20

22 This shift from representational to performative modes of analysis is inspired by Andrew Lang, ‘International Lawyers and the Study of Expertise: Representationalism and Performativity’ in Moshe Hirsch and Andrew Lang (eds), Research Handbook on the Sociology of International Law (Edward Elgar Publishing 2018). Inspired by Johns’ observation on the shift from ‘planning to prototypes’, Lang calls for a mode of critique going beyond ‘denaturalization, rehistoricization, decoding’ and employs the perspective of performativity to ask a different range of questions: ‘what productive work do [knowledge practices] do as they circulate? What forms of social action are they able to mobilize and how? What subjects, objects, and situations are produced in the manner of their circulation and deployment, and how?’ For Lang, expertise is ‘less about producing objective common sense, and more about the practical work of organizing action despite skepticism … as well as the bracketing of epistemological differences’ (at 149).

23 See World Bank LVP, Annual Report FY 2013: The World Bank’s Engagement in the Criminal Justice Sector and the Role of Lawyers in the ‘Solutions Bank’ (World Bank, 2013) (referred to below as ‘LVP Annual Report 2013’).

24 Ibid

25 Andres Rigo Sureda, ‘Eligibility of Police Expenditures for Bank Financing’ (1997) (Copy on file with author).

26 Ibid

27 Ibid

28 On the tenets, cultivation and institutional effects of ‘traditional’ approach, see Dimitri Van Den Meerssche, ‘Performing the Rule of Law in International Organizations: Ibrahim Shihata and the World Bank’s turn to Governance Reform’ (2019) 32(1) Leiden Journal of International Law 47.

29 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 93.

30 Ibid, 93, 94.

31 Interview with Anne-Marie Leroy (Washington DC, October 2016).

32 Anne-Marie Leroy, Legal Note on Bank Involvement in the Criminal Justice Sector (9 February 2012) (copy on file with author) (referred to below as ‘Leroy Criminal Justice Opinion’).

33 Ibid, para 22

34 Ibid, para 26

35 Ibid, para 34

36 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 94.

37 Ibid

38 On the emergence of a ‘governmental technology of risk’ in the public sector more generally. See Julia Black, ‘The Emergence of Risk-Based Regulation and the New Public Risk Management in the United Kingdom’ (2005) Public Law 512; Jonathan Pugh, ‘Resilience, Complexity and Post-Liberalism’ (2014) 43(3) Area 313.

39 Jim Yong Kim’s ‘Change Agenda’ called for a ‘major shift in paradigm … from a rules-based to a principles-based normative approach to operations that encourages informed risk-taking’. LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 90.

40 Ibid (emphases added).

41 Ibid

42 Particularly telling was Leroy’s managerial manifesto on the proper role of the lawyer in the ‘solutions Bank’.

43 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23).

44 This involved the adoption of Operational Policy and Band Procedure (OP/BP) 9.00. Previously, the Bank had two key lending instruments: Investment Project Financing (regulated in OP/BP 10.00) and Development Policy Financing, which has replaced and reproduced the structural adjustment lending (SAL) (regulated in OP/BP 8.60).

45 See OP 9.00 (n 44) para 5.

46 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 91. This diagnostic is embedded in the Bank’s ‘systematic country diagnostics’ (SCD) that underpin its comprehensive ‘country partnership frameworks’ (CPF). For a more elaborate definition of this new lending instrument: ‘PforR relies on Bank assessments of programme systems and institutions, promotes an integrated approach to risk, and encourages management rather than avoidance of risk, by identifying risks, and balancing them against results. PforR relies on the borrowers’ fiduciary, environmental and social systems, and seeks to address gaps in such systems through a combination of initiatives, from legal requirements and actions, to capacity building, disbursement incentives and to implementation support’. In ibid 13 (emphasis added).

47 In OP 9.00 (n 44) para 5–8. On the rationality of reform in the PforR framework. See Maninder Malli, ‘Assessing Capacity Development in World Bank “Program-for-Results Financing”’ (2014) 47(2) Verfassung und Recht in Übersee 250.

48 See, inter alia, Internal Audit Department (IAD), Audit of the World Bank Group Framework for Policies and Procedures, AC2012-0011 (February 2012) (copy on file).

49 See World Bank, Investment Lending Reform: Concept Note (2009) (copy on file); OP/BP 10.00 (n 44).

50 See OPCS, Investment Lending Reform: Modernizing and Consolidating Operational Policies and Procedures, (World Bank 2012) (copy on file) (clarifying that ‘[m]anagement outlined an investment lending reform programme that was based on … implementing a risk-based approach for investment lending’).

51 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 91.

52 Elizabeth Fisher, ‘The Rise of the Risk Commonwealth and the Challenge for Administrative Law’ (2003) 3 Public Law 455.

53 This was, of course, not only the professional trajectory of Leroy but also of the people she gathered around her. Anna Chytla—who was Deputy General Counsel under Leroy—left the Bank’s Legal Vice Presidency shortly after Leroy did in 2016 to join LF McCarthy Associates, ‘an international integrity and risk management services company’. Her webpage highlights extensive experience in ‘managing risk’ and enhancing ‘agility’, as obtained and developed in the legal department of the Bank. https://www.lfmccarthyassoc.com/copy-of-scott-b-white (accessed 9 September 2020).

54 World Bank, Environmental and Social Framework (2016) (referred to as ‘ESF’).

55 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 92.

56 ESF, ESS1 (n 54) para 39, 44.

57 LVP Annual Report 2013 (n 23) 92

58 Ibid

59 Cf Annelise Riles, ‘A New Agenda for the Cultural Study of Law: Taking on the Technicalities’ (2005) 53(3) Buffalo Law Review 973.

60 Leroy Criminal Justice Opinion (n 32) para 34.

61 Ibid, paras 31–34

62 Ibid, para 27