Abstract

The salotto buono is a typically Italian room that plays a central role in contemporary domesticity and epitomizes the permanence of traditional family structures within Italian society. This essay explores how this room, and the objects contained in it, defined and consolidated Italian middle-class identity, and how they subsequently had an impact on domestic practices and cultures. Interviews and photographs collected during fieldwork in Italy illustrate how the salotto is used and decorated today, and how it has spatially evolved in the past century. Moreover, this analysis offers further considerations on the mechanisms of permanence, imitation, as well as conformity and how these played a fundamental role in the definition of Italian society and culture by influencing the design and use of domestic interiors, among which the salotto stands out. This essay ultimately demonstrates that the salotto is the room that encapsulates, both physically and symbolically, the conservative thrust that has marked Italian society and politics from the post-war period onwards.

Introduction

The salotto buono is a central space in Italian middle-class homes. It eludes any distinction or categorization generally associated with domestic living spaces, as it is not fully an English living room, much less a French salon. While remaining a representative space, the salotto also includes the dining room in the purest expression of Italian national and domestic culture which includes food, and the rituals associated with it, as its pivots. The salotto is, consequently, a unique space from a cultural and architectural point of view, but is also a synecdochic space in relation to Italian society and culture.

It is important to notice that the history of the Italian salotto has a beginning and an end, a moment of spatial evolution which coincides with a social involution and is the setting in which contemporary Italian domesticity plays out. This regressive path unfolds on two different scales: the micro-scale of objects and individuals, and a larger one characterized by the process of definition of national identity in a country as young and conservative as Italy. The history of the salotto has, therefore, led to political implications with direct repercussions on the creation and definition of individual, gender, and class identities. The latter manifested in the multiple ways in which the domestic space was used, altered, and furnished. This essay will condense the most salient moments and aspects of this descending, fundamentally conservative journey, by demonstrating how the design and use of a room encompasses Italy’s current social tensions and crisis.

In this regard, this text focuses on the architectural production that pervades the bourgeois city, the one built during the slow and late process of urbanization and modernization of the Italian peninsula. It began with the national unity of 1861 and ended with the post-war national plans for affordable housing, or “Piani di Edilizia Economica e Popolare” (PEEP), brought forward until the end of the 1980s (Casciato Citation1988, 568). Despite the use of the term “popular” meant to indicate the “working class,” it should be noted that this type of housing was designed and built largely for the middle-class, hence the term “bourgeois city” as discriminatory in terms as in substance (Salvati 1993, 86). The predominance of the middle-class, both numerical and cultural, also explains the focus of this analysis. In fact, the latter has been establishing itself as the social and cultural model of the country since the end of the nineteenth century and was, subsequently, the protagonist of major societal changes after WWII (Scaraffia Citation1988, 214). It was also the catalyst of the nationalization and bureaucratization of Italy, which began with the unification and was reinforced during the Fascist era (Asquer Citation2011, Melograni Citation1988). Therefore, not only the “average” and “minor” housing production hosted and still hosts the majority of Italian citizens, those now belonging to the white-collar and professional middle-class, but most of its dwellings were purchased by members of that class as a result of the financial stimuli and fiscal concessions implemented in the years of the “economic miracle” (1960s and 1980s).Footnote1 For this reason, a focus on this portion of Italy’s built environment provides a sufficiently accurate picture of contemporary Italian domesticity, specifically that of a generation of retired homeowners that now inhabit post-war housing.

These buildings and their apartments, by virtue of their standardized features, also facilitate the reproduction of the domestic practices and spatial cultures that in the last century have influenced not only the inhabitants, but also the architects that designed them. Indeed, both have more or less consciously adapted to canons and lifestyles that reflect wider projects of social homologation and reinforcement of gender inequalities. Interviews and photographs taken in these interiors in 2019 support this analysis, illustrating the common traits and differences between the layout, furniture and use of domestic spaces of post-war estates by the middle-class. The very rich interiors (, and ), inextricably linked to preconceived values and lifestyles, are contrasted by unadorned exteriors which in their simplicity become bearers of the new messages of modernist architecture ( and ). This contrast exemplifies the evident detachment between architects and inhabitants, even more apparent in a such a fundamentally reactionary cultural context in which modernity, however imposed (during Fascism) or advertised (through the media in the post-war period), was never fully assimilated.

Figure 3 Francesca Romana Forlini, Gardens of Viale Etiopia’s towers, Mario Ridolfi and Wolfgang Frankl architects, Rome, 2019.

Figure 4 Francesca Romana Forlini, Courtyard of Palazzo Federici, Mario De Renzi architect, Rome (1931-37), 2019.

Social, political, and cultural “conservatism” seem to describe the elements that make up the history of the Italian salotto. It pertains, above all, to the conservation of a patriarchal model of society supported both politically and culturally by Roman Catholic morality. In fact, despite changes brought about by the two world wars and the social developments of the last fifty years, the family has been subject to choices that have cyclically favored the restoration of traditional models. Secondly, it pertains the conservation of class privileges and class distinctions by middle and upper classes that invested the space of the salotto through material culture and taste. The post-war housing heritage has also been preserved, indeed it is predominant in Italian cities today and is now part of collective memory (De Pieri et al. Citation2014, XI). Furthermore, the persistence of a conservative spatial distributive logic continues to separate female and male identities through ideological and physical barriers that still limit women’s emancipation and access to the job market. This eventually led to the permanence of the salotto, or the idea of the salotto and the social aspirations it epitomizes which, consequently, foster the scrupulous conservation of the objects and habits associated with them.

Inhabitants

Imitation

The hybrid space of the salotto is the reduction in scale and value of the aristocratic salotti. It was born as a purely representational room, rarely used even by middle-class inhabitants who, instead, preferred eating and gathering in the kitchen. The area is heavily decorated and includes the dining room, which is used – like the rest of the salotto – only in special occasions. The design of this space is the result of a series of adjustments that refer to the model of the casa agiata (wealthy home). In fact, from the 1930s onwards, most of housing projects for the lower classes, to the middle and working class, were inspired by this model (Salvati Citation1993, 86; Casciato Citation1988, 573). Despite the dwellings’ reductions the scale and the concentration of various functions in the same room, symbols of comfort like the salotto persisted. Architectural historian Maristella Casciato, in fact, specifies

The only civil house that was known in Italy was the 'casa agiata'; and of that wealthy house every family aimed to have at least one icon, a domestic representation. (…) In Italy the model of the wealthy house won in every social class, and if this model could not be achieved in the envelope, where the bargaining power of the inhabitant family is decidedly less, it could be pursued inside, where the staging was almost within the reach of every family and everyone was guaranteed the opportunity to exhibit at least a few tranches of the wealthy house (1988, 585, author’s translation).

The space devoted to the exhibition of these icons is, according to Casciato, that of the salotto. Hence, the housing model associated with this space, as well as the symbolism of the objects inside it, are imitated and emulated by lower and middle classes, in a process of class identity construction that is divided between aspirations for social ascent and conformism to models imposed by the State (Salvati Citation1993, 51; Montroni Citation1988, 135). This double inclination is inherent in the mechanisms of imitation explained by French sociologist Gabriel Tarde (Citation1903) who places them both at the centre of social and family life. In his book on the topic he not only explains how imitation is a natural mechanism in societies of all kinds, since it allows for a system of similarities and analogies that strengthen interpersonal and social bonds, but he also explains that the desire to imitate is hereditary. In fact, it is associated with mechanisms of transmission between the beliefs of one person and another (generally between parent and child), knowledge and desires, which subsequently favour assimilation and echoing of customs, manners and rituals. Class identity (but also national identity) is consolidated precisely through these processes. Tarde recognizes the unconscious character of these processes and connects imitation both to the need for conventionality in men and to the materialization of this need in architecture and domestic interiors. In fact, he writes: “architecture requires its followers to become more and more servile in the repetition of the consecrated types that are for the time being in favor” (1903, 191). Therefore thanks to its cyclical nature, predetermination, and ubiquity imitation creates the conditions for success of standardized dwellings – those that respect a certain distributive criterion at the service of the reproduction of shared practices – which become attractive to a certain social class whose daily life is conditioned by the mechanisms of imitation.

As aforementioned, imitation more often relates to tastes and manners of the upper social classes, so “when one person copies another, when one class begins to pattern its dress, furniture and its amusements after those of another, it means that it has already borrowed from the latter” (Tarde Citation1903, 197-198). This observation takes on an even more relevant dimension when the imitated social model is that of the class in power, and since imitation is nothing more than a “passive adherence to the idea of another” (Tarde Citation1903, 197), it is possible to affirm that imitation is a powerful instrument of discipline and control. The space of the salotto encompasses exactly this struggle between passive imitation and the creation of a collective identity, which condemned the Italian middle-class to be branded as conformist, conservative and closed within their private and family sphere. To sum up, the process of homologation and standardization that unfolded throughout the XX century makes the middle-class the object of a mass disciplinary and cultural operation that conditioned lifestyles and domestic practices, finding its concrete manifestation in post-war housing estates.

Family

Historians Mariuccia Salvati (Citation1993) and Enrica Asquer (Citation2011) carefully describe the process of middle-class nationalization of customs that began in Italy under the pressure of Fascist propaganda and culminated in the material and cultural mass homologation of the economic boom. Social changes targeted the nuclear family, as it was the core of the ordered Italian catholic society (Barbagli Citation1984, 19). Specifically, the traditional catholic family is nuclear, it is characterized by asymmetry between sexes and between generations, and it is based on the bonds of marriage (Golini Citation1988, 347), it is also characterized by and parsimony, which still play a fundamental role in domestic consumption. Historian Giuseppe De Rita (Citation1988) clarifies that this family model is still valid and has endured over time as it has been able to adapt to social changes that have mainly affected women in the last century. He explains that,

[a]ccording to a tried and tested strategy, the family has managed to assimilate old qualities (adaptation, arbitrage, combinatorial dimension, etc.) as it did not consider them ancient and obsolete components of the collective culture, but it took them up and valued them as tools for dealing with and mastering the new problems that it faced in recent decades: in essence it used tradition to adapt to vast structural changes. (1988, 415, author’s tranlsation)

According to the previous reflections on Tarde’s book, it is possible to say that adaptation is nothing more than a manifestation of conformism and imitation (based on intergenerational transmission) aimed at the preservation of social order. In fact, the strengthening of the family unit took place mainly thanks to the renewed vigour of behavioural rules dictated by religion, the social control it exercises, and the constant scepticism of Italian citizens towards the State, which has cyclically led them to seek shelter or help through kinship ties (Melograni Citation1988, VIII-IX).

In essence, the reasons underlying the resistance of the traditional nuclear family over the centuries should be ascribed to the mechanisms of parental transmission of values and lifestyles and to the cycles of restoration and legitimization of the traditional Catholic family by the State. In fact, it was the Fascist Regime who first restored them by strengthening the patriarchy and extinguishing the enthusiasm of young Futurist women, the first feminists, and the women who entered the labor market during the interwar period. Subsequently, the post-war government that was led for over forty years by the centrist party Democrazia Cristiana (Christian Democracy, 1943-1994) spread a “pervasive maternalist and familyist rhetoric” defined as “pastoral Catholic” until the end of the 1970s (Asquer Citation2011, 127). This widespread “culture of reconstruction” affected not only the physical aspect of Italian cities – which were rebuilt after the bombings of WWII – but also the private, domestic sphere. In fact, the generation of young couples that settled during the economic boom preferred to take refuge in traditional family values, the church and authority in general. It was especially men who reinforced these dynamics as a reaction to the massive entry of women into the job market, and they did so with a return to strong normative and moralistic beliefs (Asquer Citation2011, 127-129). In fact, throughout the 1970s the embodiment of the full-time housewife was still the most widespread and preferred, both on an ethical and regulatory level (Asquer Citation2011, 132-135). The preservation of gender privilege has, therefore, played a fundamental role in domestic and social realms, slowing down and perhaps even stopping the wave of modernity that influenced other countries’ housing interiors in a more decisive way.

The middle-class

The conquest of the salotto, this superfluous space because it is extraneous to the use and custom of most, will symbolize the social redemption and will mark, like nothing else, the access of the family into the reassuring anonymity of the middle-class. The salotto, whose diffusion is destined to gradually expand, with the uniformity of ever wider layers of the population to an average and urban life model, will become a recurring topos in treatises on domestic life (Casciato Citation1988, 576, my author’s tranlsation).

The middle-class family was the social segment most prone to own and preserve the space of the salotto. This social class was, and still is, “a cornerstone of the country's stability and a model of citizenship for other classes,” its status was consolidated through the “conquest of the salotto” and the ownership of a house (De Pieri et al. Citation2014, XVIII). More than the language or the subsequent development of mass media, it was the mobility on a national scale of the middle-class - inextricably linked to the State as belonging to its bureaucratic apparatus - that brought to completion the ideological project of standardization of the family and housing models of the unitary state (Montroni Citation1988, 136). Indeed, the typical middle-class catholic family embodies

an ideal type imposed from above; a relationship governed by a serious and severe father; a mother entirely devoted to the care of the home and family; strictly hierarchical domestic relationships; a thrifty but decent ménage are the criteria of a family model that must support from below what the State was trying to strengthen from above (Montroni Citation1988, 135, my author’s tranlsation).

The middle-class was, therefore, the easiest target of this bio-political project, as the State managed to insert itself into the process of construction of class, gender, and individual identity. For example, historian Giovanni Montroni suggests that by providing free access to school, it created an unfavourable context for an autonomous cultural production (1988). Consequently, these processes stimulated a propensity to imitate and adopt behavioural standards and adhere to imposed norms.

While these dynamics have caused the stigmatization of an entire social class, criticized for its obsession with “family respectability” and its “petty-bourgeois conservatism” as the results of a broader and more complex homologation project, this has also favoured the emergence of some peculiar characteristics, which over time have become archetypes of Italian family culture: the most important one concerns the fear of loss of acquired well-being, and this is justifiable by the economic circumstances of Italy, which has always been less wealthy than other Western countries. Economic stability is, then, for Italians something that must be obtained at any cost, and home ownership represents a security in this sense. This introduces the theme of sobriety, contained in this maxim: “temperance is not an end in itself, but the handmaid of savings. The truly rich do not spend, and in all cases they do not waste, they reinvest” (Meldini Citation1988, 429). Sobriety and the necessity to avoid waste have clear religious roots which, as previously mentioned, play a fundamental role in the construction of middle-class identity. Obviously, this has a very important implication in the use and appropriation of the salotto, the room devoted to the representation of the household. As Asquer (Citation2011) explains, the influence of catholic morality stimulated, in the period of the economic miracle, both a critical approach towards American consumption models, and a refuge in the so-called “useful consumption,” i.e. the purchase of dependable and durable domestic goods. This frugality is part of a culture focused on the construction of certainties and the preservation of acquired well-being, which finds its clearest manifestation in the purchase of a home within one of the many post-war housing projects made available at that time.

The generation of Italians who still own apartments in post-war housing complexes, consequently, grew up in a very peculiar period, in which respect for authority, order, and discipline was required, often combined with a parochial, patriarchal, and paternalistic pedagogical tradition. Despite the subsequent dynamism and changes associated with post-war modernization, this group of individuals maintained “a deep need for stability and peace, to be enjoyed first and foremost in the private sphere” where they decided to build security through the solidity of their purchases (Asquer Citation2011, 168).

Things

The “average” house and its interiors

The path that defined the design and internal distribution of post-war estates does not differ much from that of other European countries that instituted reconstruction plans after WWII. In Italy, as aforementioned, the middle-class apartment became a national model since the end of the nineteenth century. This type of dwelling is characterized by the presence of a salotto, “a place for preserving the ideal image of the house” and a room devoted to representing the status of the family group (Casciato Citation1988, 587). Between the 1920s and 1930s the Modern Movement in architecture began to take hold and spread throughout Europe, playing a fundamental role in post-war housing design. In Italy, however, this process was filtered by the Fascist Regime which, starting from its rise to power in the 1920s, embraced this new architectural movement but at the same time insisted on the restoration of traditional family models.Footnote2 Italian modernist architects had to mediate between the reformist impulse brought by Modernism and the authoritarian and reactionary proclamations of the regime. This resulted in contrasting architectural and distributive solutions and a never purely completed project of modernization of Italian society. While on the one hand many male architects of the time embraced without hesitation the theme of experimentation on the minimal and technological house – enjoying moderate success among the upper middle classes in the Northern regions – on the other hand, the first female architects, and later on the architects and engineers involved in Italy’s reconstruction, created hybrid housing typologies more in line with societal expectations of the time.

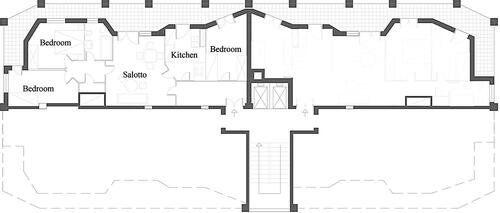

Two unrealized projects clearly illustrate these circumstances, i.e. the Plan of a Modern Quarter of the 1920s published in the Almanac of the Italian Woman of 1921 (), and Casa del Dopolavorista (1930) by Luisa Lovarini. In the house for a Modern Quarter there is clearly a salotto that incorporates study, guest room, and dining room. The coexistence of these environments marks the transition between the nineteenth century casa agiata model to a one smaller in size and with various combined functions. Both projects were, nevertheless, considered virtuous by both the public and critics as they were modern and practical homes, and both had sober furnishings.Footnote3 Despite the quality of the women architects' proposals, none of these noteworthy projects was implemented on a large scale, and this is mainly due to the lack of legitimization of female architectural production given the sexist context. Nevertheless, precisely by virtue of their demonstration purpose, these projects are particularly interesting not only for the spatial solutions proposed, but also for the innovative style of furniture designed. At the time renown architecture and design magazines such as Domus began advertising a certain type of interior design, captivating readers with a new taste in home interior decoration based on simplicity and modernity of style. The new housing was intended to, as elsewhere in Europe, educate citizens to a new way of life. However, two fundamental factors interrupted this project; the first concerns the failure of economic accessibility to modern design furniture and objects by the middle and lower classes, as they quickly became luxury goods.Footnote4 The second pertains to the resistance by the middle and working class to the simplifications brought about by Northern European modernism, the one adopted by all major Italian architects and designers of the post-war period (Casciato Citation1988, 583).

Figure 5 Plan of a Modern Quarter of the 1920s. Source: Cosseta (Citation2000, 88).

The plan to disseminate a new taste in the decoration of interiors through specialized magazines and national exhibitions took hold of the upper classes, especially in Milan. The social group not only had the financial resources to buy these new pieces of design, but also adopted the modern style to furnish their salotti. This choice was made to distinguish themselves from the middle-class, which at the time began to imitate precisely those same well-off domestic interiors (, , and ). This triggered the reaction of architects and technocrats, who wrote with frustration:

if families persist in wanting a distribution of space with ‘noble pretensions’ – the salotto, the studio – even in petty-bourgeois and craftsmen’s environments, the remedy can only be the construction of social housing that lead to this ‘simplicity’ of taste. From this point of view, the partitions are a valid help! (Bigiaretti as quoted in Salvati, 1933, 10, my author’s tranlsation)Footnote5

The architects’ failure to modernize as well as the persistence of old furniture and highly decorated interiors in lower and middle-class homes can be attributed to the failed modernization of Italian society which, as was shown, was then already hit by the regressive wave of restoration of the catholic patriarchal family. This necessarily favoured the persistence of traditional domestic practices and furnishings that still populate post-war domestic interiors today.Footnote6 In fact, it is possible to trace the similarities between two interiors in terms of language and decorative choices even though they belong to members of two different social classes and two different buildings ( and ). Specifically, the photo of interior 6 depicts the living room of an inhabitant of the lower middle-class who lives in a social housing project, while and show an upper middle-class interior in a building from the early twentieth century.

Salotto Buono

The architects of the time designated the salotto as the scapegoat for the failed project of modernization. A curious aversion to this room grew then in the 1930s as it was denounced not only as a symbol of the privileges of the bourgeois class - in stark contrast to the populist rhetoric of the Fascist regime - but also as an impediment to the advent of modernity. It has been so to such an extent that the “salotto, even when it is only a salottino [small salotto], displays the most tangible symbols of the myths and aspirations of this social group in front of an audience of relatives, friends, acquaintances who frequent the house” (Montroni Citation1988, 109, my author’s translation). Thus, a campaign for the suppression of the salotto quickly followed, yet differing in intentions and results to that of other European countries’ and with a decidedly different outcome. In fact, although the end of the salotto and the advent of a new modern space, the soggiorno (living room), were promptly announced, Italy saw no substantial changes in the use, decoration, and disposition of this room. The salotto buono was meant to be a pure representational space of both status and interpersonal power relations, it was hardly used and abundantly decorated. On the contrary, the soggiorno had to, supposedly, host the family’s everyday activities and become the intimate centre of the home. The soggiorno, however, retained the salotto’s main characteristics as key representational space, while fostering a further retreat towards the patriarchal, nuclear family. Hence, the campaign against the salotto and the introduction of the soggiorno were the result of the regime’s political rhetoric. Most importantly,

the abolition of the salotto in the years between the two wars symbolizes a more general deminutio of the private sphere, which is now enclosed entirely in the family circle. Replaced the salotto with the soggiorno, in fact, the centre of the house shifts from ‘external’ and ‘internal’, from ‘public’ and ‘private’, to an infra-family dimension, to a set of relationships enclosed in the domestic nucleus. Its substitute, the soggiorno, will never aspire to be a space of ‘sociability’ (however fictitious), but only the place of the exasperated ‘representation’ of family relationships. (…) [T]he adoption of the sala or soggiorno in Italian social housing risked turning into a field for the exercise of extremely hierarchical family relationships (between sexes and generations), a natural reflection of the Catholic values prevailing in this country (Salvati Citation1993, 28, my author’s tranlsation).

It is worth noting that the deminutio mentioned by Salvati in this passage refers to spatial and symbolic consolidation of the middle-class’ apartment in Italy’s post-war social housing projects. In fact, these considerations on the metaphorical reduction of the private sphere also apply to the spatial alteration of the salotto which was reproduced in most housing projects from the 1950s to, approximately, the 1990s. The middle-class’ identity and sociability have been, as aforementioned, already limited to the nuclear family, closest relatives, or few friends, resulting in a clear closure of the family within the home and subsequent development of social relations mainly outside the domestic realm. This leads to the conclusion that there is no clear practical distinction between salotto and soggiorno, and by virtue of the social and spatial homologation that has invested the middle-class and post-war housing, the abolition or modernization of the salotto – and its subsequent transition into a soggiorno – remains an unfinished project.

The use of the salotto is still limited, as much as possible, to important events. The room is devoted to the display of objects that symbolize the family’s wealth and beliefs, for the reception of guests, and the consumption of food. The room is generally characterized by the presence of a large table for the so-called ricorrenze (recurring or single events) positioned in the centre, under a large chandelier, representing the nuclear family and Italy’s culinary traditions ( and ). The arrangement of this piece of furniture is particularly interesting as it is part of a process of staging an ideal domestic dimension through the decoration of the interior spaces of the dwelling. In this specific context, this process is associated to the ideal image of the reunited family during meals.Footnote7 In fact, “[t]he furnishing of a house is the equivalent of a cosmogonic act, the foundation of its order, which will regulate the space and the life of those who live there putting everything in the right place” (Pasquinelli 2009, 55).This order is highly symbolic, since the arrangement of domestic space (and specifically the salotto) is based on the image designed to be projected to the outside world which often coincides with class conventions and structured interpersonal relations. Places at the dining table in the salotto are, for instance, clearly defined and reflect gender hierarchies: the head of the family always sits in the best place, that is next to the guests, whereas his wife’s seat is usually the one closer to the kitchen. Gender dynamics not only materialize through the positioning of bodies in space, but they are also connected to the spatial distribution of the salotto and the adjacent kitchen, which represented a crucial design problem for modernist architects in the post-war era (Cosseta 2000, 37).

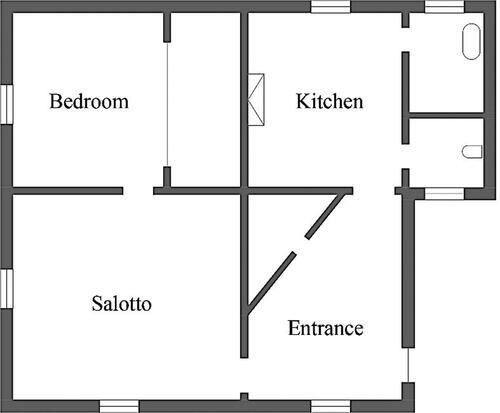

The inhabitants of architect Mario Ridolfi’s modernist housing project in Rome (1955) (), specifically the apartment at the top left of the typical plan below () interviewed in 2019, summarized very clearly what it meant to have a salotto buono:

One couldn’t live in this room. When I was young (…) this was like a sanctuary, immaculate. On practically every surface there were at least twelve photos, on this table there was a green poker table cover, on top of it there was a huge white lace thing, and then a centrepiece, three stone ashtrays. It was impossible to remove them (…) – and these objects were all condensed on one surface. There was a piano, which we then gave away (…) The doors to the salotto were always closed that is, you came from there [entrance door to the living room from the corridor] to go there [bedrooms] you had to close the doors, because everything happened inside the kitchen. In that small table that you see under the window, which is retractable and extendable, 5-6 people ate there, tightly… when we had such a space [the salotto buono] that no one could touch! Only on great occasions, holidays, could it be used… otherwise it was always closed. I remember it was always dark in here. (Author’s translation)

Ridolfi’s building hosted members of the middle-class which immediately found space for the salotto buono, that could be easily isolated (). In fact, as clarified by the inhabitants themselves, even though they had to pass through the salotto to reach the bedrooms it was strictly forbidden to stop over and spend time in it unless there were guests to welcome.

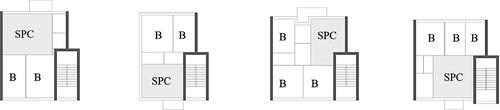

Figure 9 INA-casa dossier n°1, diagrams n° 1, 17, 30 and 31 for the internal distribution of dwellings (S = soggiorno, P = dining room, C = kitchen, B = bedroom). Source: Di Giorgio (2011, 20).

Ridolfi's project is not an isolated case, the distribution of the “soggiorno-dining room-kitchen” (or SPC, with “P” standing for “pranzo” and “C” for “cucina”) was, indeed, at the centre of the post-war Italian architectural debate aimed at identifying new lifestyles for middle-class families. The Fanfani Law (1949) started the post-war reconstruction and the INA-casa institute, responsible for the implementation of new housing, took care of preparing dossiers that suggested housing and dwelling types, leading to the standardization of life. As can be seen from the diagrams shown in the INA-casa dossiers () architects outlined different spatial solutions which were considered “rough guides” that “bent to the needs of users to divide the space into a more traditional salotto buono” (Di Giorgio Citation2011, 16). Most of the options outilined in the dossiers reflect traditional configurations in which the salotto is clearly separated from the kitchen. This spatial solution fostered the division of roles, the production of gender and reproduction of normative gender hierarchies within the domestic environment as food preparation continued to be seen as a purely feminine activity, consolidating the heteronormative and patriarchal foundations of the home. It also reflected the broader social and political project aimed at the restructuring of the traditional, catholic, heterosexual, and patriarchal nuclear family. The salotto inevitably played a central role in the representation and perpetuation of these gendered dynamics as it was the space around which the new symbology of the middle-class had slowly been built. Asquer (Citation2011) made clear how the internal distribution of post-war dwellings fostered the persistence of the salotto, thus reflecting the restoration project that, at that time, influenced all aspects of daily life. Therefore, more or less consciously, architects and members of the middle-class moved towards the same conservative direction defined by the State. This conformity clearly manifested in the salotto through the display of objects and, more in general, the permanence of this room in the overall distribution of dwellings. Indeed, both the salotto and the objects contained inside it remain symbols of traditional ideals and lifestyles, as well as the refuge of a sought-after security among members of this class.

Objects

The critique of the ‘superfluous’ and consumerist fever in the boom years coexists with the memory of the crystal cabinet, with Napoleon's canopy and the pride of memory, with the many objects hanging on the walls, each with a story (…) the critique of yesterday’s and today’s consumerism coexists with a material culture rich in details, which loves to preserve and collect rare objects, knick-knacks, trinkets that have not been functional to everyday life in the strictest sense of the term. (…) [N]ext to the house and the appliances conquered with bills of exchange, the preserved objects are not real ‘consumption’: they are made to last, to crystallize over time a passion, a belonging, a status, even if they are defined only as tools for ostentation, that would be an understatement (Asquer Citation2011, 47-48, my author’s translation).

The preservation of bourgeois order and décor is followed by the physical conservation of spaces and objects as a leitmotif of the history of the salotto and its inhabitants. The most important manifestation of these dynamics is the so-called “art of conservation” inside domestic interiors (Asquer Citation2011, 79-80). Italian women have not only shown great care for household objects, but have also boasted of their ability to keep objects in good condition over time. This is linked to the still cumbersome presence of numerous furniture and large-cut objects that are now outdated, out of fashion, or considered antiques (Asquer 2011). For example, when asked if there was any object in the house she cared about, a woman interviewed stated without hesitation:

I am emotionally attached to all [the objects inside this house] because I connect them to my family. For example, my father’s paintings, my grandmother’s piano (…) I care about it so much… I don't know how to play it, but there are all these things… this handcrafted table was in the house in Sorrento. Anything in this house reminds me [of something] … this painting, I can't tell you how old it is, it was given to my mother when she got married. I don't even know if it has value or not, in any case I am very attached to it (…) That valance has been there for sixty-three years and no one should touch it, even if they say that ‘it's old, it’s ancient, you should have something more modern…’ no! I want it there as it is! (author’s tranlsation)

The interviewee continues by talking about the objects that belonged to her ancestors, mentioning, among other items, a sling bar from her grandfather,

my grandmother's Singer, her jewellery box (…). Let's say that the sling bar is the oldest object. My mother bought the furniture when she got married, so we are talking about sixty-three years ago; this table, these consoles, even that pink sofa, also that one is sixty years old… (, , and , author’s tranlsation)

Figure 10a Francesca Romana Forlini, Salotto and significant objects: the dining table and paintings.

She is part of that in that category of women prone to the maintenance of objects considered “durable” and purchased to be such. The

'tesaurizzazione' mechanisms [capital preservation], usually interpreted as typical of the relationship with real estate, seem to have also been applied to consumer items, such as the first large appliances, jealously guarded for years and remembered today especially for their capacity to last over time (Asquer Citation2011, 55-56, author’s tranlsation).

Domestic objects are treated as the most important durable good, i.e. the house itself, in a cyclical process of conserving the status and order of things that affects all aspects of daily life. Furthermore, the intergenerational transmission of consumerist culture does nothing but materialize those imitation mechanisms mentioned earlier. In fact, the emotional aspect evoked through inter-family ties, the value of memories associated with heirlooms, the unconscious need to keep everything as it has always been favoured the perpetuation of culturally specific domestic practices. In this regard, Bourdieu (Citation1984) writes:

[e]very material inheritance is, strictly speaking, also a cultural inheritance. Family heirlooms not only bear material witness to the age and continuity of the lineage and so consecrate its social identity, which is inseparable from permanence over time; they also contribute in a practical way to its spiritual reproduction, that is, to transmit values, virtues and competencies (2010, 69).

This summarizes the processes addressed so far, as the result is a cyclical reproduction of habits, value systems, and family structures that strengthen family ties, social order, and foster the physical permanence of things and spaces like the salotto. This room thus achieves that synecdochic dimension mentioned at the beginning of this text. The single objects enclosed within it no longer tell just personal stories, but their presence and meanings extend beyond the borders of the domestic space, encompassing politics and society.

Conclusion

The history of the salotto is not over, as the space gradually started to open towards the kitchen and redefined the internal dynamics of the house. However, there is no doubt that this room included all the regressive steps forward that Italian society has made in the last century.Footnote8 An important information, however, dispels some myths about Americanizing consumerism in Italy; as much as the sought-after modernization, its influence and ethos were delayed. In fact, we have seen how during the economic boom Italians had peculiar consumer habits: they had a parsimonious approach, favoured the durability of purchases, and focused on objects’ conservation – a vision at the antipodes of the unbridled consumerism that developed elsewhere. This approach is merely the mirror of the social and domestic dynamics of the time, in line with the cyclical restoration of the traditional family and the transmission, both material and immaterial, of roles, values, and objects. These circumstances inspired the radical scenarios of architectural groups of the 1970s, which were the result of a shared fear among European intellectuals of potential repercussions of capitalism on domestic and urban realms. However, today’s domestic interiors of the middle-class seem to demonstrate the opposite. It is true that some aspects of Italian society criticized, for instance, by Italian Radical architects have persisted, such as the symbolism of objects and ceremonies, as well as social and gender imbalance of the nuclear catholic family. However, the former is the result of a need to imitate and distinguish oneself, which are intrinsic to human nature. The latter, on the other hand, is probably the most important critical contribution of this analysis. In fact, the story of the salotto encapsulates a cultural involution which has especially inflicted women as they have not been able to break away from their traditional domestic role. Despite their massive entry into the workforce over the past fifty years, women are still expected to take care of the house, which leads to numerous tensions within the family unit.Footnote9 The remnants of these dynamics are still evident in the interviewees’ answers, and they are also materially deposited inside contemporary domestic interiors. Furthermore, the differences between the exteriors and interiors of these residential complexes remains evident. The internal distribution of dwellings clearly reflects this schism as architects’ designs oftentimes reflected social conservatism. The material and symbolic conservation of the salotto is, therefore, the result on a large scale of a joint regressive path that has historically invested the political, economic, and social spheres. The only traces left by the advent of modernity are the facades of post-war housing projects, as the progressivism of architectural forms was never truly followed by progress in Italian society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Francesca Romana Forlini

Francesca Romana Forlini works in the fields of architecture and interior design with a focus on cultural and heritage studies. She is currently leading the “History and Theory of Architecture” course at the University of Hertfordshire (BA architecture) and is the director of the book series Stanze for Plectica Editrice. She previously led the “Contextual Studies” course in Interior Architecture and Design at Middlesex University. She held teaching and research positions at Harvard Graduate School of Design and the Royal College of Art, she also contributed as author and editor to the AIA-awarded journal Oblique, Critical Conservation. Francesca Romana is a PhD candidate in Architecture at the Royal College of Art under the Stavros Niarchos Foundation Scholarship, a Fulbrighter and alumna of the Harvard Graduate School of Design with a Master in Design Studies in Critical Conservation. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

Notes

1 “Average” and “minor” housing production refers to the ordinary post-war mass housing projects built in Italy in the second half of the XX century. These are relatively unknown estates in contrast with high-modernist masterpieces. In this regard, the 2001 Italian census reports that about 55% of the total housing stock available in Milan, Rome and Turin was built from the 1940s to the 1970s (De Pieri et al., Citation2014, XXIX).

2 Italian Rationalism in architecture characterizes this era but played a relatively marginal influence on the design of mass housing projects analysed in this text. Few highly refined housing projects that reflected Rationalist aesthetics – such as those built by Giuseppe Terragni, Giuseppe Pagano, and Edorardo Persico – were countered by several modernist mass housing projects. An example is the housing complex Palazzo Federici, built in the 1930s ( and ).

3 Few parallels can be drawn between the prototypes designed by modernist male and female architects. In fact, even though female architects embraced the overall project of simplification of interior furnishings the domestic spaces showcased demonstrate a greater interest in recreating a cosy environment, more in line with feminine taste and domesticity. The interiors of the Casa del Dopolavorista, which was a temporary structure realised for the V Milan Triennale (1933), are very different, for instance, from those designed by Giuseppe Terragni in his Casa sul Lago per Artista, showcased in the same exhibition. Many interesting projects designed by notable female architects have been forgotten, however, they pave the way for a new analysis of the architecture of women architects in twentieth-century Italy.

4 An exemplary case is the story of Charlotte Perriand and Le Corbusier’s furniture which was meant to be affordable, but soon became exclusive luxurious goods. Perriand herself described this process: “These pieces of furniture, before giving them to Thronet, I tried to give them to Peugeot, since it was doing bicycles for everybody, I thought it would have done also sofas for everybody. On that point we were definitely wrong. Because at the beginning there were only few sophisticated intellectuals able to buy them, and at the end even today there’s just a few people able to afford them. It is exactly the contrary of what we had set. They are luxurious pieces of design.” (Di Puolo, Marcello, and Luisa Citation1976, IX author’s tranlsation).

5 Bigiaretti, Luigi. “L’Arredamento della Casa.” Grondaie n°2 (1935)

6 This process can also be read through the lens of gender identity as design historian Penny Sparke argues in her book As Long as it’s Pink: The Sexual Politics of Taste (1996). Indeed, female identities were negotiated inside these highly decorated domestic interiors, which are representative of female tastes as opposed to the masculine features of modernist architecture and interiors.

7 See Paola Milani and Elena Pegoraro, “Tra pentole e legami familiari: il tempo dei pasti”, Rivista Italiana di Educazione Familiare, n. 2 (2006)

8 It would have been also relevant to include further reflections on how these processes have conditioned, and still condition, the female universe. This aspect, along with considerations on contemporary salotti, have been addressed by the author in her Ph.D. dissertation titled From Within: Uncovering Cultural Domesticity (forthcoming).

9 An article published the 21st of April 2021 on Italian newspaper Il Sole24Ore titled “’Woman housewife’ and ‘man with pants’, stereotypes persist among adolescents” reports some data on the persistence of gender stereotypes in Italy. This is just one among the many articles and statistics on the topic that demonstrate how gender stereotyping and traditional family models sadly persist, even among the younger generations. It is clearly stated: “the pandemic, and consequently physical distancing and domestic confinement, has even revitalized gender stereotypes and, therefore, the gender roles prescribed by it. We then find ourselves today having to face an even more complicated scenario than that of the recent past. Precisely because of a regressive ‘sliding’ into a never abandoned past where the idea of the supposed subordination of women to men, the existence of a natural role for women (that of mother and wife), remain the basis of prejudice, discrimination and violence against women” (author’s tranlsation).

References

- Asquer, Enrica. 2011. Storia Intima Dei Ceti Medi: Una Capitale e Una Periferia Nell’Italia Del Miracolo Economico. Rome-Bari: Editori Laterza.

- Barbagli, Marzio. 1984. Sotto Lo Stesso Tetto: Mutamenti della Famiglia in Italia Dal XV al XX Secolo. Bologna: Il Mulino.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. 2010. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London-New York: Routledge.

- Casciato, Maristella. 1988. “L’Abitazione e gli Spazi Domestici.” In La Famiglia Italiana Dall’Ottocento a Oggi, edited by Piero Melograni, 525–588. Rome: Laterza.

- Cosseta, Katrin. 2000. Ragione e Sentimento Dell’abitare: La Casa e l’Architettura nel Pensiero Femminile tra le Due Guerre. Milan: Franco Angeli.

- De Pieri, Filippo, Bonomo Bruno, Caramellino Gaia, and Zanfi Federico. 2014. Storie Di Case: Abitare l’Italia del Boom. Rome: Donzelli.

- De Rita, Giuseppe. 1988. “L’impresa-famiglia.” In La Famiglia Italiana Dall’Ottocento ad Oggi, edited by Piero Melograni, 383–416. Rome: Laterza.

- Di Giorgio, Giorgio. 2011. L’Alloggio ai Tempi dell’edilizia Sociale: dall’INA-Casa ai PEEP. Rome: Edilstampa.

- Di Puolo, Maurizio, Fagiolo Marcello, and MadonnaMaria Luisa. 1976. Le Corbusier 1925/1929: L’idea dell’Architettura Verificata Attraverso gli Elementi di Arredo Presentati al “Salon d’Automne” del 1929. Rome: De Luca Ed.

- Golini, Antonio. 1988. “Profilo Demografico della Famiglia Italiana.” In La Famiglia Italiana Dall’Ottocento a Oggi, edited by Piero Melograni, 327–383. Rome: Laterza.

- Meldini, Piero 1988. “A Tavola e in Cucina.” In La Famiglia Italiana Dall’Ottocento a Oggi, edited by Piero Melograni, 417–464. Rome: Laterza.

- Melograni, Piero, ed. 1988. La Famiglia Italiana dall’Ottocento a Oggi. Rome: Laterza.

- Montroni, Giovanni. 1988. “La Famiglia Borghese.” In La Famiglia Italiana Dall’Ottocento a Oggi, edited by Piero Melograni, 107–140. Rome: Laterza.

- Oppedisano, Gabriella. 2021. “'Donna casalinga' e 'uomo con i pantaloni', gli stereotipi resistono fra gli adolescenti (’Woman Housewife’ and ‘Man with Pants’, Stereotypes Persist Among Adolescents).” Il Sole24Ore, 21 April, 2021. https://alleyoop.ilsole24ore.com/2021/04/21/donna-casalinga-uomo-con-pantaloni-stereotipi-resistono-fra-adolescenti/?fbclid=IwAR1eIyAQYyb1gt Fwe9QYoWixlxSxCEsptHU_Tkeamz8YYtFsDiCjLP_eSqQ

- Pasquinelli, Carla. 2009. La Vertigine Dell’ordine: Il Rapporto Tra Sè e La Casa. Milan: Baldini Castoldi Dalai.

- Salvati, Mariuccia. 1993. L’Inutile Salotto: L’Abitazione Piccolo-Borghese nell’Italia Fascista. Tourin: Bollati Boringhieri.

- Scaraffia, Lucetta. 1988. “Essere Uomo. Essere Donna.” In La Famiglia Italiana Dall’Ottocento a Oggi, edited by Piero Melograni, 193–258. Rome: Laterza.

- Sparke, Penny. 1996. As Long as It’s Pink: The Sexual Politics of Taste. San Francisco: Pandora/HarperCollins.

- Tarde, Gabriel. 1903. The Laws of Imitation. New York: Henry Holt and Company.