Abstract

After the Second World War, Japan fell under the spell of a post-war ideology that popularized an ideal middle-class nuclear family. Mainstream housing options responded to this ideology with the introduction of a typical floorplan that contained a hierarchy akin to the nuclear family and stressed the need for individuality with multiple private (bed)rooms. By the mid-1960s, this nLDK-model — a layout system in which n came to indicate the number of rooms in addition to the Living room and the Dining-Kitchen space, had become a national code, not only creating homogeneity in the type of houses but also pushing one specific type of family. This study focuses on the two case-study houses of Kazuyo Sejima’s Bairin no Ie (2003) and Sou Fujimoto’s T-House (2005) to highlight a recent transformation in the conception of a house from a standard ‘container’ for the nuclear family into a particular house for a tangible lifestyle. By situating the two case studies in a socio-historical context, this paper aims to identify a redefinition of house-family relations that no longer relied on established notions of “wall” and “room,” but supported the free movement of people and the spontaneous formation of new relationships between rooms and functions.

Introduction

This article examines a critique of existing domestic values among architects in Japan at the end of the second millennium, manifested in the design of new kinds of living environments that contain delicate measures of privacy yet where one feels “being together”. The paper starts off providing a historical background to the development of concepts of home and housing typologies in post-war Japan that resulted from an acute housing shortage caused by the war, a rapid economic recovery, a fast-growing middle-class and a governmental push for homeownership to explain the rise of a typical housing layout system in post-war Japan that was accompanied by a typical image of what a family entailed. Using as primary sources Japanese architecture journals, an archive of personal interviews with architects and residents collected in Japan, as well as site visits that attest to the lived experience of these new kinds of living environments, this study introduces an architects’ critique of the predominant post-war housing model in Japan based on a nuclear family ideology. Kazuyo Sejima’s Bairin no Ie (2003) and Sou Fujimoto’s T-House (2005) are the two case-study houses emblematic of how this critique of existing domestic values manifested itself in a new interest among architects around the turn of the millennium in the house as a container of a tangible lifestyle rather than a mere planning device. These two houses demonstrate a clear alternative to the planning principles introduced in the prototypical two-bedroom-with-dining-kitchen floorplan that came to symbolize the typical nuclear family in post-war Japan. Influenced by these two case study houses, an entire younger generation of architects could no longer design a home based on strict private individual bedrooms, but instead experimented with alternative to “rooms” and “walls”. This altered understanding led the new generation of architects to propose to their clients a different way of living, one in which residents were encouraged to interact with each other. By identifying how architects not only recognized a growing discrepancy between the ideology of “the standardized container” for “the Japanese family” and its reality, but actively proposed alternatives, this text aims to unlock a discussion of the essential meanings of the spheres and spatial devices within the private realm. Subtlety, it also activates universal themes of privacy and collectivity beyond the Japanese context.

Nurturing a post-war family ideology

After the Second World War, Japan experienced a rapid industrial recovery using a model of state-driven economic development that would go down in history as “the economic miracle” (Gordon Citation2020, 351). This period of high economic growth was accompanied by an influx of internal migrants to Japan’s major urban areas that significantly expanded the white-collar labor force (Hirayama and Ronald Citation2006, 2). What followed was a rapid process of suburban growth that necessitated the development of a new type of domestic space. Instead of housing the extended family, houses were now designed to suit the lifestyle of a salaried worker and his nuclear family in urban conditions (Vogel Citation1965; Ochiai Citation1997). The Japanese government actively supported the arrival of newly employed salaried workers by providing access to urban housing.Footnote1 In the early 1950s, the government set up a three-tiered housing system that transformed Japan from a predominantly rental society into a homeownership society (Hirayama Citation2006, 21). Although the policy included measures for subsidized public housing, priority was given to homeownership as a means of supporting economic recovery. In 1950, the Government Housing Loan Corporation (GHLC) began to provide long-term, fixed, low-interest mortgages on standard lending conditions that provided middle-income workers with access to private homeownership. The pressing demand for housing after the war, in combination with an increasing number of nuclear families and growing wealth, fueled the prefabricated housing market (Togo Citation2010, 231). In the 1960s, the mass production of houses took off and became, in turn, the motor of Japan’s economic success and sustained growth (Hirayama Citation2003, 154).

In addition to pushing for homeownership, the post-war housing system also had the effect of constructing “a middle-class consciousness” (chūryū ishiki) (Borovoy Citation2005, 8; Sand Citation2012, 71). A new constitution drafted by the Allied Forces in 1947 during Japan’s occupation drastically changed Japanese personal and family relations and with them, domestic needs. With the aim of transforming Japan from a militarist, feudalist country into a peaceful and democratic one, the new constitution promulgated democracy, respect for the individual, and marriage based on the mutual consent of both sexes and equal rights for husband and wife, in contrast to the pre-war ideas and institutions of a patriarchal society.Footnote2 As a result, the pre-war notion of the extended household lost validity, giving way to an entirely new family ideology based on a couple or nuclear family living separately from the rest of the family members.

This post-war ideology popularized an ideal middle-class nuclear family consisting of the ubiquitous salaryman (sararīman) who dedicated his life to the company and a professional housewife (sengyō shufu) who looked after her studious children, the household budget, and the needs of her husband (Allison Citation1996; Goldstein-Gidoni Citation2012).Footnote3 Although labor was strongly divided into two gendered pools of “company warriors” versus the “education mothers,” the salaryman and the housewife were intimately connected in the image of a normative household and their equal reliance on duty and performance (Hirayama Citation2003, 154).Footnote4 The government and businesses actively supported this new standardized lifestyle. Government measures encouraged women to stay at home to take care of housework, household budgets, the education of their children, and mental support for their husbands. Corporations granted company men lifetime employment and, through a gradually rising income, the prospect of climbing the housing ladder (Hirayama Citation2006, 21). Through homeownership, middle- to high-income earners were expected to become part of the “100 million-strong middle-class” (ichioku sō chūryū).

Significant efforts were made in Japan to develop a prototypical floorplan for the modern nuclear family. Inspired by the rational planning efforts to separate sleeping from eating, drafted by urban planner and scholar Uzo Nishiyama (1911–1994) during the Second World War, a committee consisting of architects, academics, and bureaucrats began to investigate the ordinary small house for the working class in the wake of Japan’s defeat. In line with Western standards of “hygiene, sexual morality, and personal privacy”, as Nishiyama had formulated it in his treatise, the interdisciplinary committee introduced a layout that separated parents and children using two proper bedrooms (Nishiyama Citation1942, 149–155).Footnote5 Because the size of the model apartment was restricted to 35 square meters, these separation requirements were met by combining the cooking and eating spaces into an eat-in kitchen. The resulting prototypical floor plan 51 C – first introduced in 1951 – was revolutionary in the way it brought order to the small dwelling in Japan. Besides rearranging Japanese co-sleeping habits, it promoted a radical new lifestyle for the post-war democratic nuclear family. Unlike in the traditional Japanese house in which rooms served multiple functions, residents were now exposed to a 1:1 functional division of space, and the newly introduced dining-kitchen area would come to define the image of the family for generations to come (Yatsuka Citation2013, 156). The design principle underlying the 51 C floorplan was adopted by the Japan Housing Corporation (Nihon Jūtaku Kōdan) in 1955 and successively used in public housing projects called danchi, multi-unit apartment complexes which were developed throughout Japan’s urban areas in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s (Neitzel Citation2003).

Although 51 C was designed as a model for Japanese public housing, the prototypical floorplan quickly found its way into the mass-produced single-family house. With the economic boom and advancements in technical knowledge of the early 1960s, the prefabricated housing industry rapidly took off. Beginning with the Super Midget-House (1960), the construction company Daiwa House introduced a model prefabricated house that targeted newlywed couples.Footnote6 Other residential construction firms followed suit with their own versions. In these designs for prototypical houses for the nuclear family, the prefabrication industry relied heavily on the two-bedroom-with-eat-in-kitchen (2DK) concept introduced in 51 C. Yet, by adding a central living room (2LDK), they somehow appropriated the original 51 C concept of “separating sleeping from eating” and incorporated the need for (Western) individuality in private (bed)rooms. By the mid-1960s, the nLDK-model had become a national code, not only creating homogeneity in the type of house but also pushing one type of family.

Despite a discrepancy between the ideology of “the Japanese family” and alternative forms of family and lifestyles, house-manufacturing companies continued to make average models for the average family during the following decades. The nLDK format remained popular among both public and private sectors and produced a tedious uniformity among detached houses, low-rise apartment buildings, and high-rise apartment buildings throughout Japanese cities, which assumed an urban existence in which families lived their private lives separate from the public realm.

Criticizing the container

Awareness of this gap between the ideal house and ideal family, and the demand for alternative spatial models and lifestyles, led some architects to resist the tendency of the prefabrication industry to standardize the image of the family and to pose alternatives to the house for the nuclear family. By the 1990s, it was impossible to conceal the reality that families in Japan consisted of far greater heterogeneity of forms and concepts of family than had been previously acknowledged, including school refusers (futōkō), adolescents who neither study nor work (“NEET”), graduates who reside as “parasites” in their parents’ homes in order to save money (“parasite singles”), single working mothers, late bloomers (reiburu) and Solitary Non-Employed Persons (suneppu) (Ronald and Hirayama Citation2009).Footnote7 Independent architects — acknowledging that “expectations for families are considerably different from real families”, as anthropologist Merry White has formulated it, and that family is not something tangible but a subjective experience — started to openly question the functional floorplan as introduced in the postwar era (White Citation2002, 13). Associating the closed, internalized house, consisting of a fixed number of rooms, with problems such as acute social withdrawal, domestic violence, and the hollowing out of public life, some architects proposed alternatives to the grand family ideology by breaking the rigid walls of the modern nLDK floorplans, offering residents open-plan houses that attempted to strengthen the ties among family members as well as between the house and the environment.

This critique of the post-war ideology of “the container for a standard nuclear family” and its reality escalated in the 1990s, after which some architects began to actively explore ways in which recent social changes might be expressed by new spatial forms.Footnote8 Through the work of people like sociologist Chizuko Ueno, preconceptions regarding changes in the Japanese family reached architects. Ueno’s thesis centered on the current pluralization of families and the diversification of lifestyles (Ueno Citation1994). While the traditional Japanese concept of household (ie) was based on the sharing of a residence, the modern Japanese family exists above all in its members’ perception of it. Moreover, if ie is taken as the norm, then the modern Japanese family has diverged miles from this ideal image. Ueno, in the same set of essays, pointed out the existence of many new unconventional family models, some of which had been artificially constructed in their members’ imaginations.

Kazuyo Sejima’s Bairin no Ie (2003) and Sou Fujimoto’s T-House (2005) both rely on a new understanding among architects at the turn of the millennium that the contents of the house had changed, but the container itself had largely remained the same. Statistics showed that the atypical family — including single-family households, one-parent-households, and unmarried couples — had numerically surpassed the standard idealized household consisting of a couple and two children. Despite this, the postwar nLDK ideology still determined the layout of houses. Awareness about a growing discrepancy between the ideologies of the Japanese family and the reality of its multiple configurations initiated a lively discussion among architects about the meaning of “family.” As a result, architects, among them Sejima and Fujimoto, began to explore the dichotomies of public versus private and individual rooms versus a common room, as well as the question of what makes a collection of individuals into a family.

Sejima’s Bairin no Ie

Sejima reacted to the changed social conditions with the design of alternative domestic models that stemmed from her belief about the real needs of contemporary society. An early project that revealed this mode of thought is Saishunkan Seiyaku Women’s Dormitory (1990–1991) in Kumamoto. In the design for this 80-bed women’s dormitory, Sejima adopted a radical look on the program and translated dormitory not as “a building that provides sleeping spaces for a large number of people,” but rather as “a space for living for a group (Itō and Sejima Citation1991, 54).” Taking the dormitory as a scaled-up version of a single-family house, with 80 female employees forming an alternative family unit, Sejima explored the way individuals can find privacy within a collective. Rather than giving the women as much personalized space as possible in the form of 80 bedrooms, Sejima freed the “family” from such individualistic tendencies and instead emphasized the large common space. With this proposal, the architect took the liberty of translating the company's request for “a dormitory, a training center and house in one” as “a large single room containing many functions” where “eighty people could spend time comfortably as a group, and where the individual can comfortably spend time on her own” (Sejima Citation2015, 20). As each bedroom is allocated to four people, residents are invited to use the oversized 7.6-meter-high collective space at will and choose which activities to participate in. Privacy in the Saishunkan Seiyaku Women’s Dormitory, then, is not regulated by physical walls but rather by psychological barriers, so that although living communally, “each person can individually adjust her distance from others, thereby adjusting the relationships of public and private” (Sejima Citation1999, 118).

The design of the Gifu Kitagata Apartment Building (1994–2000) expresses Sejima’s commitment to humanizing residential space, not only at the scale of the individual family but also on a national level. In 1994, Sejima was given the opportunity to design a high-rise 107-unit public housing block as part of the Kitagata Public Housing Project in Gifu Prefecture, just north of Nagoya city. The program was under the supervision of master architect Arata Isozaki and allowed for a bold statement against the monotonous repetition and rigid planning of Japanese collective housing.Footnote9 The first change she introduced was to remove the general character of collective housing blocks by adjusting the proportions of the building to an incredibly thin slab, creating a building volume that was not merely related to the view from outside but that also referred to the lives inside the apartments. Next, Sejima reassessed the notion of family as regulated by Japanese social housing standards as a simple gathering of the required number of dwellings based on “a setup image of what a family is” (Sejima Citation1999, 120). Footnote10Acknowledging that contemporary Japan was no longer based on the postwar nuclear family of a couple with two children, but rather varied significantly in composition, her apartment wing was based on the premise of a place where people live “in all kinds of collective ways” (Sejima, Nishizawa, and Futagawa Citation2005, 52) The core module of her housing block, therefore, was not the “apartment” but the single “room.” By connecting these modular blocks in different quantities and in various ways — at times across two levels — Sejima introduced a flexibility in domestic patterns previously unknown to collective housing in Japan. Depending on how rooms were stacked and combined, and where the exterior walls cut the unit off from the other units, a unique image of “house” emerged.Footnote11

Sejima further explored the possibilities of dissolving the solid walls of the nuclear family box in the design of Bairin no Ie, a detached single-family house for a creative director cum copywriter, her advertising film producing husband, grandmother and two children. Acknowledging that suburban living and the stable employment system no longer existed, Sejima started off designing with a situation of a family of five in which both husband and wife were working full-time in the city. The house is a response to the clients’ request for a way of living that would be more intimate than the standard housing options, yet also contain a rich variety of different places. The residents’ vision about domesticity was interpreted by the architect as a request for “a house like a three-dimensional one-room space where the family can gain the feeling of living together” (Sejima Citation2004, 27). When Sejima completed the single-family house in 2003, fellow architects responded with awe to her original solution of accommodating the contemporary (rather than modern) Japanese family. Commentary to this house ranged from her designs as a powerful expression of “superflat” architecture that made the space look two-dimensional and depthless to a realistic yet simultaneously surrealistic indoor scenery, and the view that the house is an ultimate three-generation house that, with its multi-layering, creates a visual distance that also ties the minds of the residents together.Footnote12

Sejima response was an unconventional solution that ignored the views both of commercial house builders and of her fellow architects. While the former overlooked social changes altogether and still configured houses according to the obsolete nLDK system, the latter often strove toward the complete opposite. Independent architects, eschewing the nLDK system for its rigid division of family members and predefined functions in fixed locations, eliminated fixed rooms altogether to create “one-room” spaces. Sejima, however, interpreted the limitations of the nLDK method differently. In her opinion, the nLDK floor plan layout was not too rigidly defined (as fellow architects commonly explained), but rather too ambiguously defined. She observed that a living room, a dining room, and a kitchen are, in reality, crowded with other activities. A bedroom is not solely used for sleeping but frequently functions as a place to study, to casually read a book or to meditate. A living room can be as diverse as a place for reading, eating or napping. By extracting those extra functions from the standard nLDK system and providing each function with its own separate “room,” Sejima created a floorplan that readily exceeded the number of rooms in a conventional Japanese house.

Through close communication with the clients, Sejima translated their vision into a functional purification that would free the residents from the notion that a certain number of people needed a fixed number of rooms. As she explained in her own words:

In asking what kind of house, they had been living in, I discovered that each of their preferences seemed to overlap and expand. I thought that the size of the Japanese house would thus be insufficient for the size in question and the number of possessions of an ordinary family did not appropriately correspond to the space. When things other than the bed crowd into the limited space, the objects would not be simply placed in each bedroom or the living room but could be distributed uniformly and three-dimensionally through the house. The series of rooms became an array of small spaces that functioned more like furniture, thus requiring them to be made with thin walls. As the original objective had been for an open plan, numerous openings were created, connecting the entire house while dividing the space with thin walls (Sejima Citation2015, 64).

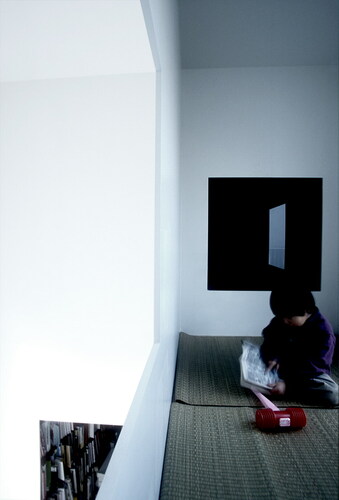

Her proposal for constructing 17 tiny rooms within a three-story white box, each scaled down to the size of the furniture each room accommodated, transformed the planning of domestic space from a functional division into a three-dimensional connector of different activities (). Despite the suggestion evoked by the floorplan that the house contains seventeen clearly defined spaces, in reality, the house is an assembly of places that loosely connect, overlap, and separate.Footnote13 In the scheme, even the private bedrooms in the house somehow belong to everybody, making the multifarious spaces a personal, and at the same time collective, experience ().

Figure 1 Rooms are so small in Bairin no Ie that they function as furniture. The son’s double height bedroom located on the ground floor has the size of a bed.

Credits: Kazuyo Sejima & Associates

Figure 2 Large windows cut out extremely thin walls create a sense of interconnection in Bairin no Ie. This space is connected both to a double-height library and a double-height master bedroom through large “cut-outs” in the walls.

Credits: Kazuyo Sejima & Associates

The composition of the internal membrane — the sum of the partitions — is of great importance in understanding the house as a place where the family feels they are living together. Made of 16-mm paper-thin steel-plate walls perforated with square openings rather than filled with conventional doors, the membrane contributes both functionally and experimentally (). The thin divisions take a minimum amount of the scarce floor area available while allowing multiple openings without imposing themselves as physical objects. The result is that the divisions produce a different type of privacy than that generated by the walls of a typical post-war Japanese house, or any Western house. The configuration of different sized rooms within this delicate membrane offers the five residents a diversified atmosphere in which the family members have a choice of action within the ambiguity of “feeling connected” and “being on one's own” (Sejima Citation2015, 41).

Fujimoto’s T-House

For architect Sou Fujimoto, the clue to newness in architecture rested in primitive forms of dwelling. Soon after he set up practice in 2000, the architect started to advocate the idea of a house like a cave (dōkutsu) as a prototypical example of the 21st-century living.Footnote14 In his vision, Le Corbusier’s Modernist domestic scheme of Dom-Ino was a “nest” (su) organized in the name of functionalism, although it represented for Le Corbusier a plan that was “free,” hence a space within which one could find one’s place. Fujimoto’s “cave” harked back to a way of living before the introduction of such nests (Fujimoto Citation2008, 24). Referring to the quality rather than the physical form of this primordial living space, Fujimoto presented the cave as a housing model that was organized not by functionalism but by place-making. A “cave,” in his vision, was a tolerant place (kyoyōsuru ba) that encouraged people to find their own place within the larger domestic setting. By contrasting the playfulness and intuition associated with his image of an artificial and transparent cave (in which floors functioned equally as benches, beds, or tables) with the fixed floors inherent in a “nest,” Fujimoto advocated for an image of the house in which the living functions “happened to be made rather than made with a strong intention” (Fujimoto Citation2008, 24).

What people needed, Fujimoto argued, was no longer the functional organization of the machine age but rather a flexibility and freedom of choice framed by a hidden order, akin to the organization of a forest (Inui, Fujimoto, Ishigami 2010, 62). Fujimoto's “new geometry” was his proposal for this new order that would square with the Modernist language of “absolute time” and Mies van der Rohe's “universal space.” If the staff of musical notation represented the Miesian architecture of universal space, it was the sounds removed from the staff — floating in space — that represented Fujimoto's new geometry. With the term “weak architecture” (yowai kenchiku), Fujimoto advocated a notion of architecture based on the relationship among its parts, rather than on an overall order (Fujimoto Citation2008, 9).Footnote15 This architecture is premised on a loose relationship rather than a rigid grid, as represented by boxes connected in a seemingly random manner, or a house in which the basic elements of walls, floors, and ceilings are no longer distinguishable, but rather deformed and punched with large holes, representing a “weak order” (Fujimoto Citation2008, 32).Footnote16

A child of the computer age, Fujimoto used his architecture to explore the problems related to the rapid rise in digital communication and the effect this had on human relationships. For him, the recently introduced Internet reflected a situation in which people are connected to each other, like a computer network. To accommodate such contemporary complex human relations, a house should not reflect a functionalist division or an open plan; instead, it should reflect an in-between state in which residents are close and connected and yet separate (hanarete ite dōjini tsunagatte iru) at the same time the proposal for the Sendai Hospital Annex (1999) revealed Fujimoto’s early ideas on architecture that are concerned with a sense of distance (kyorikan no kenchiku) (Fujimoto Citation2008, 32). Corridors and circulation spaces in this square one-story building are eliminated, creating a situation in which all rooms sit directly next to one another, “shearing like cellular tissue (Fujimoto Citation2008, 61). In the competition entry for the Annaka Environmental Art Forum (2003), a single undulating wall is the tool used to produce an infinite amount of spatial qualities. Inflections and depressions in the wall of different sizes interiorize the large public space into a place where one can feel simultaneously separated and connected to others (Fujimoto Citation2015, 40–41).

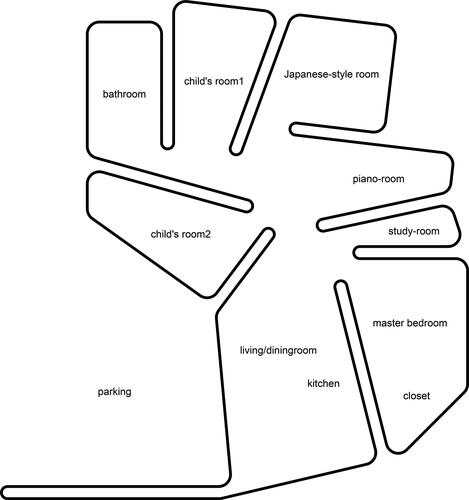

Fujimoto’s first built residential project of T-House (2005) in Maebashi further explored the concepts of separating and connecting. Rather than relying on a functionalist division of the house into separate rooms or an entirely open floorplan, Fujimoto believed in an ambiguous in-between state, in which rooms connect but at the same time remain apart (Fujimoto Citation2011, 105) (). In T-House, this notion was explored using wall panels that were placed radially inside the 90-square-meter one-room space ( and ). The 12-millimeter-thick plywood walls subtly divide the space and produce a spatial variation that significantly alters the relationship between “rooms” when people move through them (). The effect of the loosely defined, interdependent “rooms” on residents was to be “animalistic,” evoking a sense of moving (ugomeku) without any direction, like insects (Aoki and Fujimoto Citation2009, 156). “Wriggling in a house,” Fujimoto continued, “is my image of real life.”Footnote17

The floorplan of T-house is nothing more than a diagram, yet the experience inside this diagrammatic space is much more complex. The interior fluidly links the different spaces without a single corridor. Within this in essence one-room interior, “the gradation of territorial chiaroscuros changes” to give form to “ambiguous spaces and pulsating loci” (Fujimoto and Takiguchi Citation2017, 10).Footnote18

Figure 5 The more you move towards the center of T-House, the more open the interior feels and the more the space starts to connect to other places.

Credits: Daici Ano

Figure 6 The conceptual diagram of T-House illustrated how the house works simultaneously as a place of separation and that of connection.

Credits: Sou Fujimoto Architects

Figure 7 Floorplan T-House. The radially placed walls in T-House produce “places” rather than rooms.

Credits: Sou Fujimoto Architects

Figure 8 The more you move towards the perimeter of T-House, the more private and intimate the space feels.

Credits: Daici Ano

Fujimoto sold his radical design to the clients — a family of four — as “an experience of walking through the house as it were a landscape”, creating a rich and expansive sensation despite the limited space. The single-story house containing bedrooms, a living room, and a Japanese-style room in a semi-open place plays with people’s mental states:

The rooms faced each other, but they were staggered. You couldn’t see straight into the opposite room, but the space was a connected series of open areas. While maintaining private areas, the space manifested a community (i.e., a family) through the acts of moving and living. (Fujimoto and Takiguchi Citation2017, 10).

The house stimulates a corporal experience, as one is constantly reminded of each other’s presence and one is always close enough to hear each other’s voices. For Fujimoto, this proximity is not a limitation but rather an enrichment of domestic life, provoking new relationships between humans wherein “corporeality and intuition can be felt powerful” (Nishizawa and Fujimoto Citation2010, 6).

Forerunners of a new generation houses

Sejima’s Bairin no Ie and Fujimoto’s T-House heralded the beginning of a new movement in Japan towards a redefinition of house-family that no longer relied on established notions of “wall” and “room.” The house designs that sprouted from such ideas envisioned a life in the city that allowed for more flexible family arrangements and a free interpretation of domestic life. Both case study houses have been exceptional in their influence on an entire generation of younger architects who, inspired by societal changes, redefined the house from a private shelter for the standard family into an environment in which residents selectively relate to others. They, like Sejima and Fujimoto started to reorganize the content of the container in response to clients who realized that mass produced houses don’t fit their needs. These clients did not require privacy in the Western sense of the word but requested spaces that could accommodate a greater awareness among family members ( and ). Architects like Tanijiri Makoto and Yoshida Ai (Suppose Design Office), Kuno Hiroshi, Iwatsuki Miho and Kurihara Kentaro (Studio Velocity), Hosaka Takeshi, Kochi Kazuyasu, Mayumi and Kawamoto Atsushi (mA-style), Fujino Takashi, Nadamoto Yukiko, and Maeda Keisuke, to name a few, started to put emphasis in their house designs on the way residents connect with each other ().18 Through a technique of “placemaking” – creating many different areas within a fluid interior space yet with still communication among the various spaces—the architect-houses produced in the following decade tried to break the homogeneity of the housing stock in Japan in a different way. Contrary to the earlier solutions by architects to break the rigid walls of the nLDK model and make houses with a radical open plan, these architects used devices that are not real partitions and equally don’t have the conceptual significance of a room. Punching large openings in interior walls, subtly playing with the height of floor levels, adding space-dividing interior courtyards, or adding corners and niches, was their way to provide the necessary distance between various family members. Even if one cannot see the entire space at once in these houses, one is able to feel the activities of other family members. Design solutions often block views but not sound. As such, this generation rediscovered value in traditional Japanese room dividers (shōji) and folding screens (byōbu) yet put in an entirely different form to match people’s changed lifestyles and domestic requirements.

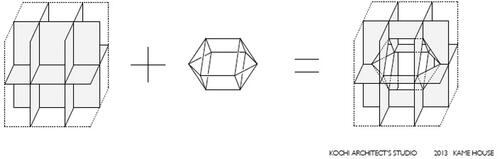

Figure 9 Kazuyasu Kochi aims to design relationships between rooms through a technique of walls, ceilings and floors that are “cut off”. The resulting dynamic and complex interior of Kame House (2013) provides the experience of being present in all rooms without losing the possibility of retreating into just one.

Credits: Takumi Ota

Figure 10 Kazuyasu Kochi’s Kame House consists of 12 small rooms divided over two floors with a hexagonal void at the middle of the house that establishes a connection to every other room. The hexonagal “cut” influences one’s sense of orientation and at the same time allows you to see many rooms at once.

Credits: Kazuyasu Kochi/Kochi Architect’s Studio

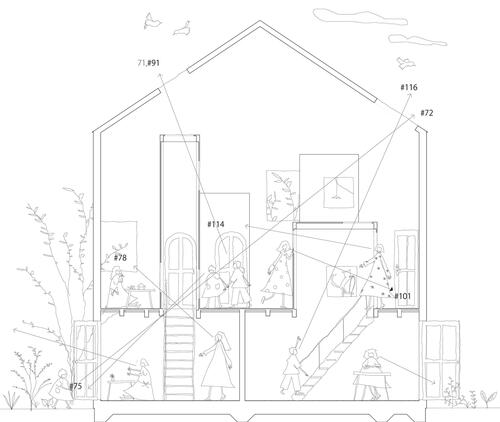

Figure 11 Miho Iwatsuki and Kentaru Kurihara of Studio Velocity removed the common hierarchical distinction between floors by integrating upstairs-downstairs connections at various places using no less than four staircases. The resulting House in Chiharada (2012) is a continuous living environment were a family of four lives in close relationship with one another.

Credits: Studio Velocity

Figure 12 Studio Velocity’s House in Chiharada redefines the notion of “rooms” with four freestanding boxes standing in a circular one-room space, containing living spaces up to 7 meters height. The upper floor contains the living area while bedrooms and bathroom are located on the ground floor. An abundance of (interior) windows allows for countless spatial relationships within the house and with the outside. Section with eyesight lines.

Credits: Studio Velocity

Figure 13 Mayumi and Atsushi Kawamoto of the office of mA-style installed a miniature gabled house with many openings in the middle of the interior of Ant House (2012). The “house-in-a-house” is not a real partition and doesn’t have the conceptual significance of a room yet creates an interior which feels more like a passage than a large space.

Copyright 2021: mA-style. All rights reserved.

Conclusion

This paper focused on the two case-study houses of Kazuyo Sejima’s Bairin no Ie (2003) and Sou Fujimoto’s T-House (2005) to highlight the sprouting of a new generation of single-family houses that introduced residents to an image of living (seikatsu suru) rather than to a mere object (building). Using 17 tiny rooms within a three-story white envelope, each scaled down to the size of the furniture it accommodates, Sejima’s Bairin no Ie freed residents from the notion that a certain number of people need a fixed number of rooms. Her proposal transformed the planning of domestic space from a functional division into a three-dimensional connecting of different activities. Fujimoto’s T-House, equally, does not rely either on a functionalist division or an open plan to accommodate the complexity of contemporary human relations. Wall panels placed radially inside the 90-square-meter one-room space subtly divide the space, producing a spatial variation that significantly alters the relationship between “rooms” when people move through them. The two case study houses are representative of an entire generation of houses designed in the first decade of 2000 that all serve as potential new prototypical models of living, not just for its owners but also for others. Looking at Bairin no and T-House allows us a much better understanding of one “chapter” in a decades-long housing debate in Japan that, in turn, illustrates Japanese architects’ continuous efforts to resist the tendency to standardize the image of house and family and propose houses for alternative lifestyles and families beyond the new, postwar nLDK ideal. In these new housing models, there is no room for a strict privacy between individual members. Instead, these house models serve as realistic alternatives to mainstream housing and are as such considered to have a much wider cultural significance beyond the profession.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cathelijne Nuijsink

Cathelijne Nuijsink is a Lecturer and Postdoctoral Researcher at the Institute for the History and Theory of Architecture (gta) at ETH Zurich. She obtained master’s degrees in Architecture from TU Delft and The University of Tokyo and a Ph.D. in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from The University of Pennsylvania. Her research focuses on cross-cultural, interdisciplinary knowledge exchange in architecture culture and aims to contribute to a more dynamic and inclusive history of architecture. She is currently completing the book manuscript Another Historiography: The Shinkenchiku Residential Design Competition, 1965-2020 (Jap Sam Books, 2022) that will be accompanied by a travelling exhibition and website as part of the Marie Sklodowska-Curie postdoctoral research project “Architecture as a Cross-Cultural Exchange: The Shinkenchiku Residential Design Competition, 1965-2017”. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 The three pillars of Japan’s postwar housing policy consisted, in chronological order, of the 1950 Government Housing Loan Corporation (GHLC) Act, The 1951 Public Housing Act, and the 1955 Japan Housing Corporation (JHC) Act. While the GHLC facilitated home ownership to middle-class incomes and the JHC developed multi-family housing estates for middle-income households, the Public Housing Act subsidized public housing to low-income people. However, the division was unequal.

2 The new Japanese Constitution came into effect on May 3, 1947, during the Occupation period after the nation’s defeat in the Second World War. http://japan.kantei.go.jp/constitution_and_government_of_japan/constitution_e.html

3 For alternative pictures of the Japanese family in the high-growth era, the limitations of the stay-at home housewife and the consequences of the salary man life see, among others, (Goldstein-Gidoni Citation2012; Borovoy Citation2005; Allison Citation1994; Kondo Citation1990; Roberson and Suzuki Citation2002; Aoyama et al. Citation2014). About the expectations of children in the “Japan Inc.” society: (Peak Citation1991; LeTendre Citation2000).

4 For a more detailed account on the binary between “company warriors” versus “education mothers,” see (Dasgupta Citation2003; Thorsten Citation2012).

5 In his 1942 treatise “The Theory of Separate Eating and Sleeping for a Functional Composition of Living Spaces,” Nishiyama laid the basis for a new prototype for a standardized floorplan for “all people.” A small house could only have comfort if it had order, he argued, and this was to be achieved by separating the eating-related area from that of the sleeping quarters (Nishiyama Citation1942).

6 See the website of company Daiwa House for a description of its history. https://www.daiwahouse.com/English/about/history/y1960.html

7 For an extensive discussion on social changes in Japan in the 1990s and the resulting multiple family configurations, see (Ronald and Hirayama Citation2009).

8 The critique of the living room and n bedroom formula reached new heights in the April 1995 issue of Kenchiku Zasshi. Facilitating a roundtable discussion with architects Mayumi Miyawaki (b. 1936), Riken Yamamoto (b. 1945) and Kengo Kuma (b. 1954), the magazine brought to light an awareness among architects about the gap between the nLDK norm and the reality of how people lived. (Miyawaki et al. Citation1995).

9 In the 1950s, the Japan Housing Corporation (JHC) started building public housing in suburban areas to address the housing shortage. In the run-up to the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, private developers joined the market with rented and privately owned apartments. To make the commercial apartments distinctive from public housing, private developers borrowed the “exotic” English word mansion (マンション “manshion” ) to suggest a spacious and comfortable apartment. Since public housing units and mansions are based on the very same room layout, collective housing in Japan has a very homogeneous character.

10 Original Japanese phrase of 設定された家族像 (settei sareta kazokuzō) translates as “a setup image of what a family is.” (Sejima Citation1999, 120)

11 “Could it be that laying out room units work better than laying out household units?” is the question Ryue Nishizawa (Citation2005, 9) posed himself when working on the design of Gifu Kitagata Apartment. .

12 A plurality of opinions about Bairin No Ie was published in Jūtaku 10 nen-2000–2010, a publication complied by Shinkenchiku publishers in 2010.

13 Note the similarities with a modernist architect such as Adolf Loos (1870–1933) who in a series of private houses in the early the 20th century already experimented with a free disposition of volumes within a simple building form to give more complex interior spaces than are possible with continuous horizontal floor divisions. His most notable examples are the Steiner House (1910), and Scheu House (1912–13). While Bairin no Ie perhaps attempts a similar diversity of spaces, Sejima does so with other means — not through half-wall partitions and skipped floors like Loos, but by using super thin walls with openings so big that the walls feel at times absent, and at times protective.

14 The first monograph in English on the work of Sou Fujimoto lays out, albeit in a preliminary way, his architectural theories. (Fujimoto Citation2008).

15 Sou Fujimoto, in his lecture in the TN Probe Lecture Series, “Alternative Modern.” On Quotation. (Itō Citation2008, 9).

16 Fujimoto’s “Weak Order” echoes Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo’s idea of “Weak Thought” (il pensiero debole). The Japanese translation of Vattimo’s book with the same title (1983), however, appeared only in 2012 in Japanese translation as Yowai shikō (Weak Thought). A parallel development within Japan, however, is seen in the writings of Kengo Kuma who coined the term “weak architecture.” Kuma advocated architecture made of “weak” natural materials as an alternative to “strong” modern architecture of steel, concrete, and glass (Kuma Citation2005). Fujimoto, on the other hand, translated “weak” as an architecture of relationships between parts that together create a whole. For him, it refers to a weak system or weak order in which separate building elements such as slabs, columns, and stairs are not clearly distinguishable but are rather “undefined” in terms of their function. In this kind of vision on architecture, slabs can be slabs, but can also function as chairs, steps, or shelves (Fujimoto 2001, 10–11). See also the interview (Nuijsink 2008, 178).

17 Fujimoto deliberately used the more sensuous term ugomeku (蠢く) rather than the more familiar ugoku (動く) to stress the naturalness of the movement. Where ugoku implies a movement from A to B, ugomeku refers to a more primordial action of “wriggling,” such as the movement of insects at the arrival of spring. (Aoki & Fujimoto Citation2009, 156).

18 One of the most frequently heard phrases during my interviews with Japanese architects of this generation echoes sociologist Chizuko Ueno’s description of living together while each of the residents can find their own space (Ueno Citation1992). Toyo Ito has espoused critique on the many white boxes made by young Japanese architects as the wrong interpretations of the work of Sejima. Only a few of them, including Sou Fujimoto, managed to give a new twist to Sejima’s diagram architecture by pushing it forward with “primitive” ideas (Itō Citation2009, 4). For architects’ individual interests and space making techniques, see also (Nuijsink Citation2012a, Citation2012b, Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

References

- Allison, Anne. 1994. Night Work: Sexuality, Pleasure, and Corporate Masculinity in a Tokyo Hostess Club. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Allison, Anne. 1996. “Producing Mothers.” In Re-Imaging Japanese Women, edited by Anne Imamura, 135–155. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Aoki, Jun, and Sōsuke Fujimoto. 2009. “Ima Jūtaku o Tsukurutoki ni Kangaeru Koto” (What I Think about When Designing a House These Days).” Jūtaku Tokushū 276 (April): 154–159.

- Aoyama, Tomoko, Laura Dales, and Romit Dasgupta. 2014. Configurations of Family in Contemporary Japan. London: Routledge.

- Borovoy, Amy Beth. 2005. The Too-Good Wife: Alcohol, Codependency, and the Politics of Nurturance in Postwar Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Dasgupta, Romit. 2003. Creating Corporate Warriors: The "Salaryman" and Masculinity in Japan.” in Asian Masculinities: The Meaning and Practice of Manhood in China and Japan, edited by Kam Louie and Morris Low, 118–134. London: Routledge.

- Editorial. 2010. Jūtaku 10 Nen-2000–2010” (the First Decade of the Century: Japanese Houses). Tokyo: Shinkenchiku sha Co Ltd.

- Fujimoto, Sōsuke. 2015. Sou Fujimoto Architecture Works 1995–2015. Tokyo: Toto.

- Fujimoto, Sou. 2011. “Internet jidai no kenchiku to wa – T House to Annaka kankyo art forum.” In Fujimoto Sōsuke dokuhon, edited by Yukio Futakawa, and Sou Fujimoto. Tokyo: A.D.A. EDITA.

- Fujimoto, Sou. 2001. “Architecture of Parts.” Japan Architect 43 (Autumn): 10–11.

- Fujimoto, Sou. 2008. Fujimoto Sōsuke Genshoteki na Mirai No Kenchiku” (Sou Fujimoto Primitive Future). Tokyo: INAX Shuppan.

- Fujimoto, Sōsuke, and Noriko Takiguchi. 2017. Sincere by Design: The Architecture of Sou Fujimoto. Tokyo: Toto.

- Goldstein-Gidoni, Ofra. 2012. Housewives of Japan: An Ethnography of Real Lives and Consumerized Domesticity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gordon, Andrew. 2020. A Modern History of Japan. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hirayama, Yōsuke. 2003. “Housing Policy and Social Inequality in Japan.” In Comparing Social Policies: Exploring New Perspectives in Britain and Japan, edited by Misa Izuhara. Bristol: The Policy Press, 151–172.

- Hirayama, Yosuke. 2006. “Reshaping the housing system: home ownership as a catalyst for social transformation.” In Housing and Social Transition in Japan, edited by Yosuke Hirayama, and Richard Ronald, 15–46. New York; London: Routledge.

- Hirayama, Yōsuke, and Richard Ronald. 2006. Housing and Social Transition in Japan. London: Routledge.

- Inui, Kumiko, Sou Fujimoto, and Junya Ishigami. 2010. “Ko No Jidai Kara Shūgo No Jidai e.” (from the Age of the Individual to the Age of Common).” Shinkenchiku 85 (11): 62–67.

- Itō, Tōyō. 2008. “‘Yowai Kenchiku’ Kara No Dappi” (Casting off Weak Architecture).” In “Genshoteki na Mirai No Kenchiku” (Architecture of a Primitive Future), edited by Fujimoto Sōsuke, 6–11. Tokyo: INAX Shuppan.

- Itō, Tōyō. 2009. “Theoretical and Sensorial Architecture: Sou Fujimoto’s Radical Experiments.” 2G 50: 4–11.

- Itō, Tōyō, and Kazuyo Sejima. 1991. “‘Saishunkan Seiyaku Jyoshi Ryō: baransu Kara Umareru Kinshitsu.’ (Saishunkan Seiyaku Women’s Dormitory: homogeneity Born from Balance).” Kenchiku Bunka 541 (November): 43–58.

- Kondo, Dorinne. 1990. Crafting Selves: Power, Gender, and Discourses of Identity in a Japanese Workplace. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Kuma, Kengo. 2005. “Weak Architecture.” GA Architecture 19: 8–15.

- LeTendre, Gerald K. 2000. Learning to Be Adolescent: Growing up in U.S. and Japanese Middle Schools. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Miyawaki, Mayumi, Riken Yamamoto, Kengo Kuma, Takenobu Watanabe, Shūji Funo, and Manabu Hatsumi. 1995. “‘nLDK Igo’ (beyond nLDK).” Kenchiku Zasshi 110 (April): 26–28.

- Neitzel, Laura. 2003. “Living Modern: Danchi Housing and Postwar Japan.” PhD dissertation., Columbia University.

- Nishiyama, Uzō. 1942. “Jūkyō Kūkan No Yōto Kōsei ni Okeru Shokushin Bunriron.” (the Theory of Separate Eating and Sleeping for a Functional Composition of Living Spaces).” Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai ronbushu, 25: 149–155.

- Nishizawa, Ryūe. 2005. Creating Principles—Structure, Plan, Relationship, Landscape. GA Architect 17. Tokyo: A.D.A Edita.

- Nishizawa, Ryūe, and Sou Fujimoto. 2010. “A Conversation between Ryue Nishizawa and Sou Fujimoto.” In Sou Fujimoto, 2003-2010: Theory and Intuition, Framework and Experience, edited by Sou Fujimoto and Fernando Márquez Cecilia, vol. 151, 5–19. Madrid: El Croquis.

- Nuijsink, Cathelijne. 2008. “Log House: Fujimoto Stacked 189 Logs to Create a Small Vacation House.” Mark Another Architecture 16: 172–183.

- Nuijsink, Cathelijne. 2012a. “House without Doors.” Mark Another Architecture 40(October/November): 90–95.

- Nuijsink, Cathelijne. 2012b. “Light and Airy.” Mark Another Architecture 36(February/March): 156–167.

- Nuijsink, Cathelijne. 2017a. “The Store Box That is Suppose Design’s Residential Portfolio.” In Suppose: Building in a Social Context, edited by Makoto Tanjiri and Ai Yoshida, 256–257. Amsterdam: Frame Publishers.

- Nuijsink, Cathelijne. 2017b. “I Want to See Many Rooms at the Same Time' : Kazuyasu Kochi Likes to Make Cuts in Walls, Floors and Ceilings.” Mark Another Architecture 68 (June): 132–139.

- Ochiai, Emiko. 1997. The Japanese Family System in Transition: A Sociological Analysis of Family Change in Postwar Japan. Tokyo: LTCB International Library Foundation.

- Peak, Lois. 1991. Learning to Become Part of the Group: The Japanese Child’s Transition to Preschool Life. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

- Roberson, James E, and Nobue Suzuki. 2002. Men and Masculinities in Contemporary Japan: Dislocating the Salaryman Doxa. London: Routledge.

- Ronald, Richard, and Yōsuke Hirayama. 2009. “Home Alone: The Individualization of Young, Urban Japanese Singles.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41 (12): 2836–2854. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a41119.

- Sand, Jordon. 2012. “中流 / Chūryū / Middling.” San Francisco: UC Berkeley. eScholarship. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3rw380hc.

- Sejima, Kazuyo. 1999. “‘Sakuhin Setsumei’ (Explanation of the Projects).” Japan Architect 35 (Autumn): 118–120.

- Sejima, Kazuyo. 2004. “‘Sejima Kazuyo Kenchiku Sekkei Jimusho Bairin No Ie Kotonaru Katachi Sukēru No Heya o Yawaraka ni Kankei Dzukeru’ (Kazuyo Sejima Architects’ House in a Plum Grove: softly Correlating Rooms of Different Shapes and Scales).” Kenchiku Bunka 59 (670): 24–27.

- Sejima, Kazuyo. 2015. “Ie” (Living Space).” Japan Architect 99 (Autumn) : 60–67.

- Sejima, Kazuyo, Ryūe Nishizawa, and Yukio Futagawa. 2005. Kazuyo Sejima, Ryue Nishizawa: 1987-2006. Tokyo: A.D.A. Edita.

- Thorsten, Marie. 2012. “Supermoms: Kyōiku Mamas.” In Superhuman Japan: Knowledge, Nation, and Culture in US-Japan Relations, edited by Marie Thorsten. London: Routledge.

- Togo, Takeshi. 2010. “Nihon no kōgyōka jūtaku (purehabujūtaku) no sangyō to gijutsu no hensen” (Transition of the industry and technology of industrialized housing (prefab housing) in Japan). Survey Report on Systematization of Technology. Vol. 15 (March 2010). Tokyo: National Museum of Nature and Science. http://sts.kahaku.go.jp/diversity/document/system/pdf/063.pdf. .

- Ueno, Chizuko. 1992. “Kaitai Shita Kindai Jūkyo No Yukue: kazoku, Sei, ko (the Dismantling of Modern Housing: Family, Gender, Individual).” Kenchiku Bunka 552 (October): 54–62.

- Ueno, Chizuko. 1994. Kazoku No Seiritsu to Shūen (The Rise and Fall of the Modern Family), 2009). Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

- Vogel, Ezra. 1965. Japan’s New Middle Class: The Salary Man and His Family in a Tokyo Suburb. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- White, Merry. 2002. Perfectly Japanese: Making Families in an Era of Upheaval. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Yatsuka, Hajime. 2013. “Jūtaku Kenchiku No ‘Kigen’ (the Origins of House Design).” In Jūtaku to wa Nanika, edited by Xknowledge, 156–159. Tokyo: X-Knowledge.