Abstract

The introduction of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000 by the United Nations, which was aimed at reducing poverty, hunger, illiteracy, gender inequality and correcting some developmental malfunctions, was received with mixed feelings from development experts especially regarding its 15-year target for Africa. Some scholars were of the opinion that the MDGs were a huge failure in most, if not all, countries in Africa. Others, however, recorded considerable progress in developing countries. Deploying data from secondary sources, this paper, which is a retrospective study, brings into recognition that while the implementation of the MDGs was a good idea, they do not reflect Africa’s development stance outright. This paper analyzes each goal with substantial examples, and contends that the MDGs were an indirect way of making developing countries depend on the West. The paper recommends that Africa has to make a demarcation between its economy and that of the Western world.

Introduction

A critical examination of development in Africa reveals a disappointing performance despite varying policies and strategies put in place. From the pervasive state of misery, disease, poverty and all forms of negativity that continue to plague the continent, it is clear that real development is yet to take place. Confronting this notion in the gross aftermath of colonial rule is disheartening but realistic. As much as the euphoria which followed the end of colonial rule had fizzled into thin air, its aftermath had been of an indirect overturn. Various neo-liberal strategies put in place by various African leaders to quicken development in Africa and put it on a path of sustainability have appeared vague and outside the African context, for example, the Structural Adjustment Programme [SAP] of 1986 (Shah Citation2001, 2; Orji Citation2005, lxxviii–lxxxi).

Considering all these eventualities in the actualization of development, the United Nations in an attempt to fast track development processes, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, came up with a strategy including an array of goals, targets, and indicators known as Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000. These goals sought to bring about development and foster a close-up relation between the developed North and the under-developed South (Ogunrotifa Citation2012).

From the inception of the programme to its end in 2015, Africa’s progress report about the goals and targets indicated a slow pace, and for the goals whose targets were met in some African countries, the achievement did not reflect in the continental sphere (MDG Report Citation2015). Going through the literature, a variety of factors has been attributed to the failure of MDGs on the African continent. They are lack of ownership and commitment (Ogunrotifa Citation2012; Ali Citation2013, 105), non-emphasis on sustainable development (Sachs Citation2012), evaluation and implementation problems (Oshewolo Citation2011), poor governance and conflicts (Global Poverty Report Citation2002), and the failure to own the goals at various levels and capacities (Aleyomi Citation2013, 10–11; Igbuzor Citation2015, 14–17; Nigeria MDG Report Citation2015).

The outlined factors, as cogent as they may appear, represent the symptoms and not the real issue undermining the achievements of MDGs in Africa. The fundamental issues mitigating against the actualization of the MDG goals, targets, and indicators are not Africa-bound as seen in the latter part of this paper. Ogunrotifa (Citation2015) affirmed that the developmental goals do not reflect the actual picture of what is happening on the ground in Africa or what it takes to promote development in Africa, as a result of the neo-colonialist technique put in place by the superpowers and the UN in developing the goals. In other words, the implementation of the MDGs can be regarded as a reflection of neo-colonialism that seeks to strengthen Western economic power and its mainstream development discourse.

This paper attempts to critically examine the MDGs and why they were ineffective in Africa. Although the MDGs have come and gone, and have been succeeded by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), it is imperative that the MDGs are analyzed within the African context, with a view to providing alternatives as to where and how Africa’s development should be executed.

This paper is divided up as follows. The conceptual term for this study is discussed in the section below. Section three focuses on the theoretical framework about the actualization of MDGs in Africa. Section four deals with the why and how of the Millennium Development Goals. Section five addresses the MDGs in Africa and why they could not be achieved. Section six looks at a road map to development in Africa while the final section presents the conclusion and concluding remarks.

Basis for analysis

Neo-colonialism

This is a concept that has been in existence since the 1960s. To the layperson, neo-colonialism is an indirect form of control by a superpower through cultural and economic means. It also means an indirect continuation of colonial policies under the guise of achieving freedom (Udodilim Citation2016). Kwame Nkrumah,Footnote1 in his book Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, articulated the concept as:

… an indirect source of exploitation rather than for the development of the less developed parts of the world. Investment under neo-colonialism increases rather than decreases the gap between the rich and the developing nations. Moreover, the struggle against neo-colonialism is not aimed at excluding the capital of the developed world from operating in the less developed countries. Instead, it is aimed at preventing the financial powers of the developed countries to be used in a way to impoverish the less developed ones. (Nkrumah Citation1965, 30)

Neo-colonialism could also be described as the geopolitical practice of using capitalism, business globalization, and imperialism to control society instead of either direct military control or indirect political control (Gbera 2008, 107). For example, most African nations rely on their colonial mother countries for defence and internal security. Attesting to this, Nkrumah (Citation1965) argued that the imperialist nations advance their economic neo-colonial aspirations through various schemes under the guise of improving or developing other countries. These imperialist countries major in areas such as poverty alleviation, education, child mortality and foreign aid while having an inclined mind to exploit these other countries natural resources or subject them to policies that are against their beliefs or national interests. For instance, the Iranian leader, Ayatollah Ali, maintained that the interference of the UN but especially USA’s intervention in Libya was an indirect opportunity to seize Libya’s oil. In Ali’s words, ‘the US and Western allies claim they want to defend people by carrying out military operations. Instead, they came for Libyan oil’ (Phillips Citation2011). Similarly, multinational corporations owned by these ex-colonial masters like Great Britain, Germany, France and other European countries continue to exploit the natural resources and people of the countries they had previously colonized. British companies, for instance, currently have access to large areas of Africa’s mineral resources, just as they had during the colonial era. Records from the London Stock Exchange show that 101 British companies have mining operations in 37 sub-Saharan Africa countries, and they collectively control over $1-trillion worth of Africa’s most valuable resources (Curtis Citation2016).

Fantahun (Citation2013, 13) posits that most economic and trade policies used by developing countries have been adopted from mechanisms or techniques that were used by colonial countries. Hence, neo-colonialism encourages the dependency syndrome where developing nations remain dependent on developed nations.

Development

This is a pluralistic term that has been accorded different meanings by different authors (such as Rodney Citation1976; Sen Citation1999; Fukuda-Parr Citation2003; Thomas Citation2004) based on their belief or knowledge of the term. However, there has been a common theme in the definition of ‘development’ which can be divided into three perspectives: the first perspective sees ‘development’ as the realization of economic and societal progress; the second places emphasis on individuals as the basis for development; while the third conceptualizes ‘development’ as multidimensional, that is, the combination of societal growth and individual progress.

Looking at development from the economic and societal point of view, Rodney (Citation1976) defines development to be the ability of a state to utilize its resources for the wellbeing of its citizens. Thomas (Citation2004) posits that development is a structural change in the society involving a long-term transformation of the society. From the individual domain, the COCOYOC declaration asserts that development is the redefinition of man and his entitlement to basic things in life such as shelter, health, clothing, and education (Ghai Citation1977, 6). In a similar view, Sen (Citation1984) states that development should enhance the entitlement and capabilities of individuals in the society. Todaro and Smith (Citation2005, 51) describe development as a distinct transformation in which a society transforms the lives of its citizens from an unsatisfactory way of life to a fine-tuned life.

Lastly, the multidimensional approach to development which gained popularity in the late 1990s to the 2000s was defined by UNDP (Citation1990) to be a process of enlarging people’s choices that are available to individuals who can live long and healthy lives. From a different angle, Fadeiye (Citation2005) asserted development to be innovations or progress which brings about changes that result in a better quality life for people in society. He expatiated that such development should include the eradication of poverty, as well as a reduction of inequalities and in the unemployment rate. Also, there should be easy access to basic needs such as health, shelter, food and education. Correspondingly, Adedokun, Agboola, and Ojeleye (Citation2010) defined development as the involvement of people in using their thoughts and resources within and outside their environment to create positive change in society.

The above definitions show that although development is all encompassing, it essentially aims to bring about notable transformation, improvement and advancement that are reflective in the lives of the citizens and in the nation in its entirety.

Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)

In ensuring development over the world, the United Nations came up with a developmental framework known as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in the year 2000 to respond to the world’s developmental abnormalities. The framework, which comprised eight well-outlined goals, eighteen defined targets and 48 quantifiable indicators (see ), was designed to solve developmental abnormalities and ensure a better life for citizens (Eteete Citation2013, 108). Adopted by 189 nations and signed by 147 heads of states, the goals had a timeframe of being achieved by 2015.

Table 1: Millennium Development Goals.

The MDGs emerged from actions, targets and several developmental conferences prior to 2000 and sought to eradicate poverty, and promote human dignity, equality, good standards of living and environmental stability (Aluko and Nwogwugwu Citation2013, 225–226). However, there were mixed feelings regarding the actualization of the developmental policy by 2015. While some scholars felt the MDGs target was not comprehensive enough with the 15-year time frame (Todaro and Smith Citation2009), others argued that the goals formulated were unfair particularly to Africa (Easterly Citation2009; Aleyomi Citation2013, 1–3; Dada and Owolabi Citation2013; Igbuzor Citation2013, 3–11).

Methodological inferences

This paper adopted a secondary method of collecting data. The sources of data include textbooks, journals, articles, magazines, newspapers and the internet, as they are related to the work.

Theoretical framework

This paper is anchored on the dependency theory. The theory which emerged in the 1960s was precipitated by discontentment with the modernization theory. As noted by scholars like Prebisch (Citation1950) and Singer (Citation1950), the modernization theory turned the world into a dominant abode where third world countries especially were being marginalized and had to deal with policies imposed from outside. The dependency theory indirectly did not change the thinking of modernization theory on development. According to Dos Santos (Citation1970, 226), the dependency theory is a position where the relationship between or amongst countries assumes the form of dependence where some countries expand, while others are a reflection of such expansion. The theory divides countries in the world into two: the core nations and the periphery. The core nations include the powerful nations in the global economic system. They include the USA, Japan, Russia and Europe. These nations are characterized by well-grounded economic diversification, strong military forces, and high levels of technology and industrialization, all of which exercise a significant means of influence over periphery nations. The periphery nations in this context are mainly the developing nations in sub-Saharan Africa and countries from Latin America. These third world or developing countries have very poor economic diversification and are open to exploitation by multinational companies who exert huge influence over them.

The dependency theory emphasizes that the lack of development in the periphery nations is attributed to exploitation carried out by the core nations (Willis Citation2011). Matunhu (Citation2011, 68–69) argues that dependency has made Africa a dump for waste and excess labour. It has also made it a market where the terms of trade and policies or strategies adopted are to the advantage of the developed world. Examples include the failure of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the 1980s (an initiative of the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and the Western DonorsFootnote2) to address Africa’s financial crisis of the 1970s and other key problems affecting Africa’s development such as weak management of the public sector, poor investment choices, unreliable infrastructures, etc. (Heidhues and Obare Citation2011).

The SAP was adopted by African leaders in the erroneous belief that it would promote macro-economic stabilization, privatization and free market development, thereby fostering economic growth and extricating people from poverty. However, it failed to promote economic growth; neither was there an improvement in the reduction of the poverty level. Instead, it plunged African countries into further debt and development deterioration. Countries like Uganda had to retrench half its civil service to be able to cater for the few left; Zambia witnessed an increase in the divorce rate as a result of increased financial hardship; and Zimbabwe’s debt increased and its currency devalued (NewsRescue Citation2009). The failure of the SAP, as originally designed, to effectively address the developmental challenges in Africa has resulted in rethinking the outcome of the MDGs, now the SDGs, as a repackaged plan of the West to have Africa at their mercy. As posited by scholars such as Easterly (Citation2009) and Dansabo (Citation2013), the MDGs are a modernized way of having developing countries at the mercy of the West.

The MDGs take into cognizance inclusiveness, ownership, accountability and transparency through its indicators. However, this does not change the ideological underpinnings of the MDGs as the global context, thus revealing a contradictory impulse to Africa’s developmental stance, putting into question the adequacy of the goals and indicators as developmental tools for Africa.

The Millennium Development Goals: A mismatch for Africa

The prevailing intensity of poverty across the globe triggered the General Assembly of the United Nations to come up with the establishment of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) during the millennium summit in 2000. The adoption of the MDGs was an evolvement from 23 developmental conferences and meetings such as the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (Soubbotina Citation2004, 123; Rippin Citation2013). Eight goals were formulated that sought to reduce poverty and human deprivation at a global level, with mapped out targets and measurable indicators, to be accomplished within 15 years (Hulme Citation2009, 4).

The goals were regarded as a design set to reduce poverty in its many dimensions such as income poverty, disease, maternal deaths, and lack of shelter, while simultaneously promoting gender equality, education, foreign aid and environmental sustainability (UNMP Citation2005, 1). The implementation of the goals spelt out freedom for countries and individuals. In Poku and Whitman’s (Citation2011) opinion, when people are poor, ill or illiterate, they are restricted to what they can do with their freedom.

In his study, McArthur (Citation2013, 2) also regarded the MDGs as more than goals; he referred to them as an integration of countries to achieve global integration for development. Implicitly, the MDGs were supposed give room for countries to come together and assist themselves in the areas of foreign aid and core investment in infrastructure, thus assisting and empowering the poor wherever they reside.

Yet, the outcomes for Africa have been contradictory. Regardless of the immense foreseen benefits of the MDGs, there was some criticism regarding their implementation and adoption, especially by Africans, in the development of their continent. Ogunrotifa (Citation2012) argued that the MDGs were not designed to bring about development in African countries but a form of neo-colonialism. Using the problem-solving theory of Cox (Citation1981, Citation12), which states that a theory is always for someone and a particular purpose so as to obtain an efficient result in the smooth functioning of the system, Ogunrotifa laid emphasis on how development cannot be separated from politics and economics, how theory is linked to practice, and how material relations and ideas are intertwined together to co-produce global development. This implies that whenever there is a problem that is going to affect the overall functioning of a system, a theory or strategy is quickly designed to address the problem. Indirectly, the idea of the MDGs emerged because of the developmental crisis, such as poverty, hunger, gender inequality and others, faced in the world, especially amongst developing countries, thereby warranting developed countries to come up with a design like the MDGs to bridge the gap.

Poku and Whitman (Citation2011) argued that developmental issues cannot be reduced to eight unified goals because various countries have different areas of concern. Kabeer (Citation2005) and Waage et al. (Citation2010) in their studies also criticized the MDGs on the premise that they were not inclusive of those they claim to assist in the creational process. Instead, the MDGs had little involvement to do with developing countries and their civil societies.

As Amin (Citation2006) posited, the USA, Europe and Japan (often regarded as the imperialist troika) drove the creation of the MDGs and subjected them under the instrumentality of international organizations like the World Bank, United Nations, International Monetary Funds (IMF) and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for them to have international recognition.

It is worth noting that Western-led reform in Africa has frequently been in conflict with the continent’s own development strategies. Ake (Citation1996, 21) referred to this phenomenon as ‘competing agendas’, which is evident between Western institutions and African governments over African development approaches. The prescription of liberal policies by developed nations as the right and most appropriate path of development for Africa has in most cases clashed with the developmental objectives and vision of the continent and further ‘dive-crashed’ the continent. One such policy is the SAP, the aftermath of which left many African countries in burdensome debts.

The implementation of the framework of the MDGs has been regarded as neither benefitting to Africa nor contextualized (Easterly Citation2005; Ogunrotifa Citation2015). Fukuda-Parr and Greenstein (Citation2010) argued that the framework favours developed countries and rich institutions. According to them, the MDGs were not designed to bring development to developing countries. Instead, they were meant to protect the interests of a specific order, which is revolving poverty while maintaining a capitalist status quo.

The MDGs have also been criticized on the grounds that the goals set were insufficiently ambitious when considered against the volume of basic human needs that were not being met (Barnes and Brown Citation2011). For example, the first goal (eradicate extreme poverty and hunger) when compared to the 1996 World Food Summit’s goal on poverty alleviation, rather than halving the proportion of people suffering from extreme poverty and hunger, the MDGs should have instead aimed to halve the absolute number of people suffering.

All these submissions align with Escobar’s (Citation1995) thesis that international discourse on development is not tailored towards achieving true development but has more to do with the exercise of power and domination over third world countries.

MDGs in Africa: The trickle-down effect

The achievement, or otherwise, of any global development programme like the MDGs depends on the motive and origin of the idea itself. A critical understanding of the MDGs based on the above submission shows that the MDGs were developed for the world’s developing nations without their inclusive voice. Amin (Citation2006) questions the rationale behind the MDGs and asserts that the initiative was not basically to bring development to the developing countries but a form of neo-colonialism. He added that the goals, which were drafted by Ted Gordon, a renowned consultant for the CIA, tend to give easy access to the further exploitation of developing countries. This implies that the whole idea was not homegrown solutions for developing countries problems; rather it was the initiative of the troika, co-sponsored by the World Bank, IMF and OECD, and foisted on developing countries as a path towards development, just like the SAP had been. It is no wonder that Easterly (Citation2009) regarded the design of the targets and indicators of the MDGs as being unfair to developing countries, particularly African countries, because the basis of their measurement made it difficult for these countries to progress.

The MDGs have come and gone and have been succeeded by the SDGs. It is imperative to analyze each goal of the MDGs within the African context with a view to come up with a developmental strategy that could aid African countries.

Millennium Development Goals in Africa: Analytical review

Despite the challenges faced in the implementation of the MDGs, as stated in the previous section, the goals could still be regarded as relatively successful in Africa. For example, poverty in Rwanda reduced from 78% to 44.9% in 2003 with the help of MDGs induced policies (Sangado et al. Citation2003). Also, countries like Benin, Togo, Tanzania, Nigeria and São Tomé made considerable changes in the area of education (Durokifa and Moshood Citation2016, 664). Even though some scholars believe that African countries could have done better (MDG Report Citation2007; Aribigbola Citation2009), other scholars (Falade Citation2008; Aleyomi Citation2013; Ki-moon Citation2015) maintain that Africa made no appreciable progress towards the actualization of the goals. Hence, there is a need for a better understanding of the existing situation that is associated with development in Africa using the MDGs. This study analyzed each goal as a form of neo-colonialism which indirectly hindered development in Africa.

Poverty eradication and hunger

To Ahmed and Cleeve (Citation2004, 21), poverty is rooted in the thinking of Africans. The traditional culture of Africans has values which impede their development. For instance, almost all African countries give room for having a large family which is often a rational response to poverty. Hence, any target or yardstick to be used must take into account the African culture and mentality. However, the targets used to define, measure and tackle poverty and hunger as depicted in the MDGs challenge the realistic nature of poverty in developing countries.

It would have been better if these kinds of questions were asked: What is the nature of poverty in different countries? Does the global yardstick of poverty and hunger measurement adequately encompass the poverty level of countries all over the globe? The poverty situation in Nigeria might not be similar in nature and level to that in countries like Bangladesh, Uganda, Sierra-Leone, amongst others. Therefore, using a yardstick of people whose income is less than $1.90 per day as it is now, and the proportion of individuals who suffer hunger, cannot capture a country’s true poverty state. The one-size-fits-all yardstick cannot adequately measure poverty and hunger. For instance, a country like Nigeria has a minimum wage of N18,000 monthly, while the MDG target was to halve the proportion of people whose income is less than $1 a day (which was changed to $1.90 a day in 2011). The equivalent of $1.90 today in NairaFootnote3 is N608 (Mataf Citation2017), while the black-market rateFootnote4 is N874 (Vanguard Citation2017). Hence, if an individual with a wife and children earns a minimum wage of N18,000 monthly, following the global yardstick, they would be living in poverty. People in other African countries also face similar scenarios such as this (Ucha Citation2010; Magnowski Citation2014; Chandy Citation2015). A study carried out by the World Bank in Uganda shows that using the $1.90 yardstick increased the number of poor people in the country. According to the report, out of every three Ugandans who had moved out of poverty, two fell back as a result of this poverty line (World Bank Citation2016).

Education

Education is the great engine of personal development. It is through education that the daughter of a peasant can become a doctor, that the son of a mine worker can become the head of the mine, that a child of farm workers can become the president of a great nation. (Mandela Citation1995)

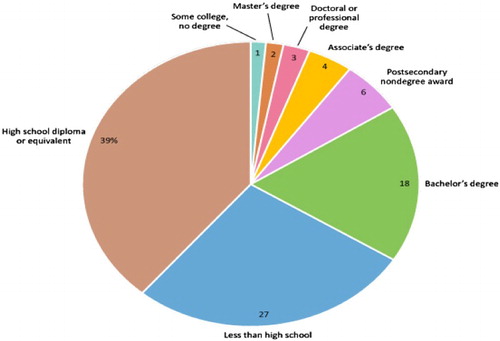

Figure 1: Designated jobs in the USA according to educational level, 2013. Source: Torpey and Watson (Citation2014)

Thus, the second goal of the MDGs did not depict the African position. What should happen after the completion of a primary school education are issues that were omitted. Igbuzor (Citation2013, Citation17), while reviewing MDGs for a post-development agenda, noted that the focus on primary education had led to the neglect of secondary and tertiary education which, had in, turn contributed to the production of unqualified people in the labour market. Additionally, the neglect of secondary and tertiary education would increase the poverty rate since in many African countries, having only a primary school certificate does not provide one with the opportunity to obtain a befitting job, and without a befitting job, one might not be able to earn a meaningful income. For instance, statistics in South Africa reveal that 60% of people who have only primary school certificates were unemployed (Stats SA Citation2014).

Gender equality and women empowerment

The third goal in the MDGs laid a lot of emphasis on the issue of gender equality and women empowerment, prominently amongst boys and girls in primary and secondary schools, and also among adults especially in the area of giving more chances to women in politics and attaining political posts. However, the inability to understand how gender is entrenched and shapes the everyday lives of people will affect efforts made to address gender inequality (Ogunrotifa Citation2015, 3). Undoubtedly, the MDGs failed to capture the cultural practice and historical context that underpins gender and religious belief in Africa. For example, there are areas in Africa where the female gender is prohibited from going to school and prevented from doing certain jobs.

Beliefs such as these hinder development, and until cultural beliefs and practices of African countries are put in place as regarding gender equality, achieving gender equality will be unrealistic in African nations.

Health

Goals 4, 5 and 6 were concerned with improving the health situation in countries, from reducing infant mortality by two-thirds, to reducing maternal mortality and stopping the spread of pandemic diseases such as AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis. As important as these goals were to the African community, based on past data shown by the United Nations (UN Citation2000) and Easterly (Citation2009), the MDGs did not put in place holistic policies which would have aided African governments in addressing the underlying causes of death and diseases. However, reports by the World Health Organization (WHO Citation2014) and the African Development Bank (ADB Citation2015) indicated that Africa made some slight progress in health-related matters. For example, countries like Ethiopia, Liberia, Malawi and Tanzania were able to reduce under-five-mortality to a large extent; Cape Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea and Rwanda were able to reduce their maternal mortality rate; Algeria, Burundi, Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Nigeria have done well in halting tuberculosis; in the fight against malaria and other diseases, Algeria, Botswana, Gabon, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Seychelles and Tanzania have recorded good outcomes.

Regardless of this result, there has been an inexcusable number of deaths recorded from preventable causes (ADB Citation2015). Schmidt (Citation2008) and Ogunrotifa (Citation2012) posited that the MDGs did not take into cognizance specific African problems like corruption, mismanagement of funds, inadequate data, weak monitoring and evaluation, and weak human and institutional capacity leading to low programme implementation. Hence, policies were not built around these problems. For example, Ogunrotifa (Citation2012) argued that the Nigerian government failed to address the problem of universal healthcare in the country. Instead, they supplied cheap drugs to patients (12). This is one of the reasons that Okeke and Nwali (Citation2013, 70), in their study, asserted that policies or strategies without effective institutions to implement them are meaningless.

For Africa, specific policies that are aligned with the African context should be developed and implemented. Implicitly, illiteracy and awareness, and not the contraction of these diseases, is the issue in Africa. In determining health policy, considerations should be placed on the awareness of such diseases and their consequences, and there should be more focus on the benefits of early detection of such diseases as tuberculosis, malaria and AIDS.

Environmental sustainability

The seventh goal was based on the fundamental principle of integrating the principles of sustainable development into national and global policies (Ogunrotifa Citation2015). This principle overpowered targets 10 and 11. As stated by Amin (Citation2006), there was no explicit content attached to the principle other than targets 10 and 11.

However, the above-mentioned targets and indicators within the African context seemed unrealistic and unworkable. Although Africa is endowed with diverse natural, mineral, and environmental resources, the MDGs did not take into consideration the increasing population in Africa coupled with the growing demand for these resources. Also, the global West has a high stake in African industrialization as most industries in AfricaFootnote5 are owned by multinationals. Hence, resources obtained from Africa are taken outside Africa and spent on the development of the foreign nations.

Many African countries also have inappropriate policies and programmes shielding their citizens’ access to improved water sources in urban and rural areas (Aleyomi Citation2013). For example, the 2015 Nigeria MDG Report emphasized that Goal 7 was primarily achieved in Nigeria because the people had chosen to build their own boreholes rather than relying on the government (Nigeria MDG Report Citation2015). South Africa’s policymakers and water research commission had also in the past four years continued to put all hands on deck in finding solutions to the water problem faced in the country (Tissignton Citation2011; Madi Citation2016). Likewise, the National Water Policy of Ghana has been coming up with policies to assist the country in providing its people with access to safe water and sanitation considering the water crisisFootnote6 in the country (Doozie Citation2017; water.org).

Attesting to the strong role of African governments in ensuring environment sustainability coupled with the development projects organized by international institutions like the World Bank, IMF and others, Okeke and Nwali (Citation2013) added that there has been uneven success between rural and urban areas. According to Okeke and Nwali (Citation2013, 69), more precedence was given to urban than rural areas. While there is nothing wrong with development activities in urban areas, it is fundamental that these are replicated in rural areas.

Foreign aid and global partnership

The eighth goal has been referred to as the fundamental basis upon which all other goals rested (Ogunrotifa Citation2012). The provision of aid and development assistance was needed especially by developing countries to guarantee poverty reduction and promote global prosperity for all. Nevertheless, this goal was a form of neo-colonialism by the troika to control the developing countries (Nkrumah Citation1965; Akata Citation2015; Ogunrotifa Citation2015). Goal 8 required a partnership between the developed and developing countries. However, the developed countries knew that it would not be possible for the developing countries to achieve the MDGs unless they relied on assistance such as foreign aid and business opportunities emanating from the West. Thus, this aid was conditional, as argued by Udodilim (Citation2016), and came with benefits highly favourable to the West. Udodilim (Citation2016) also asserted that most foreign aid was given as loans which bore high interest rates, or as an exchange for something of the utmost importance to the developing country. In both cases, thus, the West benefitted while the position of the developing countries worsened.

This goal also gave room for extreme privatization, deregulation and globalization. For example, since 2000, a vast amount of the European Commission’s budgetary allocation has been from the support of African, Pacific and Caribbean countries through the Commission’s numerous businesses in these countries. As recorded by Curtis (Citation2016), 101 British companies have mining operations in 37 sub-Saharan African countries. On the other hand, the European Union as a whole contributes around 60% of the Global Development Assistance to African countries. This made it a critical player in the global efforts to achieve the MDGs in Africa. Additionally, the developed countries ensured that the developing countries opened their borders to foreign goods and multinational companies to make investments that would lead to greater capitalist economic development in return for economic aid, grants and loans.

This analysis buttresses Escobar (Citation1995) and Lawson’s (Citation2015) statements that the MDGs were not tailored towards achieving real and genuine development in developing countries. Instead, the MDGs had more to do with the West’s market extension and the exercise of power and domination over Third World countries.

From the Millennium Development Goals to the Sustainable Development Goals: Africa’s state of development

Following the completion of MDGs, the United Nations and other international developmental agencies like the United Nations Development Programme, WHO and others came up with a post-developmental agenda beyond 2015 known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Adegbulu Citation2015; Ihejirika Citation2015). The SDGs, which were launched in September 2015, but commenced operation in 2016, comprised 17 goals with the aim of improving the livelihood and the stability of the economy and environment, and protecting the planet for future goals. As plausible as this may seem, developmental observers such as Igbuzor (Citation2015), Ihejirika (Citation2015) and Sachs (Citation2015) have raised concerns as to how Africa will achieve 17 goals within the time frame, given that it was unable to achieve the eight Millennium Development Goals.

Examining the outline of the SDGs, it is clear that the premise underlying development is unchanged (Ogunrotifa Citation2015). It is still a top-down approach, just like the MDGs, although there were participatory platforms like regional consultations and websites through which people/civil societies could send in their opinions (Lawson Citation2015). However, the question is: ‘How well have these views and lessons learned from the MDGs been taken into consideration?’ Another basic issue is how inclusive these goals are towards Africa development.

Ogunrotifa (Citation2015) insists that the SDGs are a continuation of the efforts by the West to safeguard their interests, especially their multinational companies. However, the goals have been broadened and now take into consideration some mistakes made from the implementation of the MDGs. For example, the fourth goal of the SDGs (quality education for all phases), unlike the universal primary education goal of the MDGs, has been broadened to include secondary and tertiary education, thus giving educational opportunities to a lot more children and youth. Goal 8 also gives room to make available decent work and to promote economic growth. Nonetheless, these goals, like the MDGs, still rely on a general framework for development instead of being contextualized for the settings where they are to be applied.

The African continent is still battling with developmental issues such as poor governance, corruption, unemployment, mismanagement of funds, insurgencies, terrorism, political upheavals, insecurity, population influx and a depleting economy (Aleyomi Citation2013; Okeke and Nwali Citation2013, 69; UNDP Citation2016). These problems faced by African countries are not specifically addressed in the SDGs, and until these issues are dealt with within an African context, achieving these developmental goals in Africa will remain a challenge.

Further developmental address for Africa

In as much as a general statement of development could be acknowledged and accepted, it is best defined, understood and situated within the everyday realities of individual countries. This implies that African nations must look beyond the new rhetoric of the SDGs for their development. This is because the SDGs, like its predecessor MDGs, are not constituted based on the African context, but on a globalized platform. The following recommendations are hereby highlighted:

Ownership: African leaders, through their blocs like the African Union and the African Economic Union, must come up with their own development approach that hinges on a free society and on the cultures and beliefs of the African people, and that also aligns with the political, economic and social beliefs of Africans. They must look inwards and develop homegrown solutions by working with local economists, African development experts, social scientists, policymakers and people from the judiciary, to tackle problems of poverty, hunger, malnutrition, healthcare crisis, environmental hazards and other issues confronting the continent. This will help the African community to chart their own path and keep up with their needs which are free from external pressures. In doing this, they can cease to rely on a colonialist type of approach by the developed countries and their institutional agencies such as the UN, IMF, EU and the World Bank.

Inclusive participation: If global developmental policies are to be adopted by African countries, then there must be all-round participation in their formulation, just as it was before the SDGs, which is more inclusive and involves the participation and opinion of the grassroots. There should be more research and interactions where every developmental stakeholder in each municipal or local level works hand in hand with local activists, community leaders and civil societies to map out the real problems faced by the people and identify sustainable solutions in solving such problems.

Proposed development commission: There should be a internal development commission which would serve as a subsidiary of the United Nations. It would work independently, without interference from national governments or the international institution. The commission would consist of local activists, developmental observers and experts, community development leaders, academicians, officials from various international agencies and from the government, who would be saddled with national development issues and matters relating to development financing, funds distribution with respect to developmental projects, as well as implementation, monitoring and evaluation of development projects.

Each country should develop its own yardstick for measuring the actualization of its developmental targets. By doing so, checks can be put in place to identify the existence of weak institutions and mismanagement which undermine the accurate measurement of achievement towards national goals.

Conclusion

This study contextualized the implementation of the MDGs in African countries as a form of further exploitation by the Western nations using a neo-colonialist dictate. It also emphasized the development of the MDGs as a one-size-fits-all extrapolation of global trends and common targets that draw their strength from the broader consensus and rhetoric of open markets, inclusion, and partnerships. Thus, in Africa affirming to implement the MDGs, the continent weakened the ability of its countries to expand their economies transnationally as the West has coveted it. This status quo goes with an African proverb that says: ‘What you do not own, you cannot control.’ In this case, for Africa, it is: ‘What you do not design, you cannot implement and expect it to work perfectly.’

The MDGs have proven, within their time frame, that the purpose of designing them was not aimed at the deliberate transformation of the social, political and economic structure of the African continent. Instead, the MDGs were designed by Western nations to extend their markets to African countries and have these countries at their mercy.

Therefore, following the submissions made, the MDGs were neither the creation/introduction of new ideas by the UN nor the product of ideas to tackle poverty and underdevelopment. Moreover, the present SDGs follow the same approach as the MDGs albeit with minor adjustments. These adjustments, however, neither changed the designed goals from being one-size-fits-all targets, nor – just like the MDGs – did they look at the historical, political and social structures that are inimical to development in each country. Thus, Africa needs to break away from an exploitative capitalist system which will continue to do more harm than good to the continent (like the Structural Adjustment Programme did), and look beyond the narrow lens of the MDGs, now the SDGs. Africans should also equip themselves with homegrown solutions with respect to their developmental agenda, and firmly engage themselves in purposeful networks through their blocs, such the African Union.

Acknowledgements

This paper was first delivered at the 17th Annual Africa Conference at the University of Texas, Austin in Texas, USA held March 31st−April 2nd, 2017. The authors benefitted greatly from significant inputs given by scholars and panelists present, and thank the conference organizers and everyone who contributed to the success of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Anuoluwapo Durokifa is an emerging researcher in the Department of Public Administration, University of Fort Hare. Her research interest cuts across policy implementation, organizational studies/management, development and leadership issues.

Edwin Ijeoma is the Head of the Department of Public Administration at the University of Fort Hare. He is professor of Policy and Public Sector Economics and a recognized scholar in monitoring and evaluation. A prolific writer and researcher, he has a series of published publications and books to his name, such as Introduction to South Africa's Monitoring and Evaluation in Government.

Notes

1 Kwame Nkrumah was the first president of Ghana from 1960–1966.

2 Western donors are countries like the USA, Germany, Japan and other relevant developed countries.

3 This is the bank rate of N320 to US$1 as at 6 March 2017.

4 The black-market rate of N460 to US$1 dollar as at 6 March 2017.

5 West here means the global powers or people in developed countries.

6 Statistics showed that 67% of Ghanaians lacked access to safe water and improved sanitation. Many of the households with access to safe water and sanitation invested in their own solutions, while those who lacked fund could not (water.org).

References

- ADB. 2015. Growth, Poverty and Inequality Nexus: Overcoming Barriers to Sustainable Development. [Online]. https://www.afdb.org/en/documents/document/african-development-report-2015-growth-poverty-and-inequality-nexus-overcoming-barriers-to-sustainable-development-89715/

- Adedokun, M. O., B. G. Agboola, and J. A. Ojeleye. 2010. “Practical Steps for Rural Community Development.” Contemporary Humanities 4 (1/2): 241–247.

- Adegbulu, A. 2015. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals and Targets. [Online]. Accessed January 11, 2017. https://adesojiadegbulu.com/sustainable-development-goals/

- Ahmed, A., and E. Cleeve. 2004. “Tracking the Millennium Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Journal of Social Economics 31 (1/2): 12–29. doi: 10.1108/03068290410515394

- Akata, L. M. 2015. “Africa and the United Nations Millennium Reforms: A Critical Appraisal.” PhD diss., University of Nigeria.

- Ake, C. 1996. Democracy and Development in Africa. Washington DC.: Brookings Institution Press.

- Aleyomi, M. B. 2013. “Africa and the Millennium Development Goals: Constraints and Possibilities.” International Journal of Administration and Development Studies 4 (1): 1–19.

- Ali, I. A. 2013. “Appraising the Policies and Programmes of Poverty Reduction in Nigeria: A Critical View Point.” International Journal of Administration and Development Studies 7 (10): 88–110.

- Aluko, J. O., and N. Nwogwugwu. 2013. “MDGS in Nigeria: An Examination of the Contributions of the Redeemed Christian Church of God and the Seventh-Day Adventist [2000–2010].” Arabian Journal of Business Management and Review, 222–236.

- Amin, S. 2006. “The Millennium Development Goals: A Critique From the South.” Monthly Review 57 (10): 1–15. monthlyreview.org/2006/03/01/the-millennium-development-goals-a-critique-from-the-south. doi: 10.14452/MR-057-10-2006-03_1

- Aribigbola, A. 2009. Institutional Constraints to Achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in Africa: The Example of Akure Millennium City and Ikaram/Ibaram Villages in Ondo State, Nigeria. FGN/ECA/OSSAP-MDGs/World Bank 7-9 May 2009.

- Barnes, A., and G. W. Brown. 2011. “The Idea of Partnership Within the Millennium Development Goals: Context, Instrumentality, and the Normative Demands of Partnership.” Third World Quarterly 32 (1): 165–180. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2011.543821

- Chandy, Laurence. 2015. “Why is the number of Poor People in Africa increasing when Africa’s economies are Growing?” Brookings, May 4. Accessed February 6, 2017. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/Africa-in-focus/2015/05/04/why-is-the-number-of-poor-people-in-africa-increasing-when-african-economies-are-growing.

- Cox, R. 1981. “Social Forces, States and World Orders: Beyond International Relations Theory.” Millennium 10 (2): 128–129. doi: 10.1177/03058298810100020501

- Curtis, M. 2016. The New Colonialism. War on Want Campaign.

- Dada, S. O., and S. A. Owolabi. 2013. “Millennium Development Goals and Eradication of Poverty in Nigeria.” Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 150–157.

- Dansabo, M. T. 2013. “Contending Perspectives on Development: A Critical Appraisal”. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4 (16): 41–53.

- Dos Santos, T. 1970. “The Structure of Dependence.” American Economic Review 60 (2): 231–236.

- Doozie, P. 2017. “The Looming Water Crisis in Ghana and the Way Forward.” Modern Ghana [Online] February 13, 2018. https://www.modernghana.com/news/766875/the-looming-water-crisis-in-ghana-and-the-way-forward.html

- Durokifa, A., and A. Moshood. 2016. “Evaluating Nigeria’s Acheivement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): Determinants, Deliverables and Shortfalls.” Africa Public Service Delivery Review 4 (4): 657–684.

- Easterly, W. 2009. “How The Millennium Development Goals Are Unfair to Africa.” World Development 37 (1): 26–35. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.02.009

- Easterly, W. 2005. Can Foreign Aid Save Africa? In Clemens Lecture Series. Saint John's University.

- Escobar, A. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Eteete, M. A. 2013. “Re-Inforcement of the Regime of Human Rights Law as Channels for Achieving Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).” Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 107–116.

- Fadeiye, J. O. 2005. A Social Studies Textbook for Colleges and Universities. Ibadan: Akin-Johnson Publishers.

- Falade, J. B. 2008. “Socio-economic Policies and Millennium Development Goals (MDGS) in Africa: Analysis of Theory and Practice of MDGS.” In E. A. Akinnawo, et al. (Eds.), Proceedings of International Conference on Socio-Economic Policies and Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in Africa, pp. 4–32. Faculty of Social and Management Sciences, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba Akoko, 24 and 26 September 2008.

- Fantahun, Michael. 2013. “Africa-China Relations: Neocolonialism or Strategic Partnership? Ethiopia as a Case Analysis.” PhD diss., Atlantic University.

- Fukuda-Parr, S. 2003. “The Human Development Paradigm: Operationalizing Sen's Ideas on Capabilities.” Feminist Economics 9 (2–3): 301–317.

- Fukuda-Parr, S., and J. Greenstein. 2010. “How should MDG Implementation be Measured: faster Progress or Meeting Targets.” Centre for inclusive growth working paper 63. [Online]. http://tinyurl.com/ortwhn6.

- Gbara, Loveday. 2008. “Policy Analysis of Nigerian Developmental Projects 1979–2004.” PhD diss., Washington State University.

- Ghai, D. P. 1977. The Basic Needs Approach to Development: Some Issues Regarding Concepts and Methodology. 148Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Global Poverty Report. 2002. “Achieving the Millennium Development Goals in Africa. Progress, Prospects and Policy Implications”.

- Heidhues, F. and G. Obare. 2011. “Lessons from Structural Adjustment Programmes and their Effects in Africa.” Quarterly Journal of Agriculture 50 (1): 55–64.

- Hulme, David. 2009. “The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs): A Short History of the World’s Biggest Promise.” Manchester, Brooks World Poverty Institute Working Paper 100 [Online]. Accessed July 05, 2016. <http://www.bwpi.manchester.ac.uk/resources/Working-Papers/bwpi-wp-10009>.

- Igbuzor, O. 2013. “Review of MDGs in Nigeria: Emerging Priorities for a Post 2015 Development Agenda.” Presentation of the national and thematic consultation for post 2015 development agenda. At Ladi Kwali Hall.

- Igbuzor, O. 2015. “Transition from MDGs to SDGs in Nigeria.” Opinion Nigeria, October 15 [Online]. Accessed February 19, 2016. www.opinionnigeria.com/transition-from-mdgs-to-sdgs-in-nigeria-by-otive-igbuzor/#sthash.g83bTgr6.dpbs.

- Ihejirika, P. I. 2015. “SDGs: Will Nigeria Overcome Extreme Poverty, Hunger by 2030.” Leadership [Online]. Accessed February 19, 2016. leadership.ng/news/472659/sdgs-will-nigeria-overcome-extreme-poverty-hunger-by-2030.

- Kabeer, N. 2005. “Gender Equality and Wome's Empowerment: A Critical Analysis of the Third Millennium Development Goal.” Gender & Development 13 (1): 13–24.

- Ki-moon, Ban. 2015. On African Day, UN Chief Spotlights Continent's Acheivements Reflects on Challenges of 2015. UN News [Online]. Accessed March 15, 2017. https://news.un.org/en/story/2015/05/499702-africa-day-un-chief-spotlights-continents-acheivements-reflects-challenges-2015

- Kolawole, T. O., Y. K. Adeigbe, Y. H. Zaggi, and E. Owonibi. 2014. “Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in Nigeria: Issues and Problems.” Global Journal of Human Social Science: Sociology and Culture 14 (5): 43–53.

- Lawson, Ponnle. 2015. “Progress Towards Achieving the United Nations First Millennium Development Goal: An Analysis of Income and Food Poverty in Nigeria’s States of Osun and Jigawa.” MPhil., Nottingham Trent University.

- Madi, Themba. 2016. “Service delivery and equitable distribution of water and sanitation services in the Newcastle Local Municipality.” PhD diss., University of the Free State.

- Madunagu, E. 1983. Nigeria: the Economy and the People. London: NewBeacon Books.

- Magnowski, D. 2014. “As Nigeria Gets Richer, More Nigerians live in Poverty.” Business, March 18 [Online]. Accessed February 15, 2017. https://mg.co.za/article/2014-03-18-as-nigeria-gets-richer-more-nigerians-live-in-poverty.

- Mandela, N. 1995. Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Boston: Back Bay Books.

- Mataf. 2017. US Dollar to Nigerian Naira [Online]. https://www.mataf.net/en/currency/converter-USD.NGN?M1=100.

- Matunhu, J. 2011. “A Critique of Modernization and Dependency Theories in Africa: Critical Assessment.” African Journal of History and Culture 3 (5): 65–72.

- McArthur, J. 2013. “Own the Goals: What the Millennium Development Goals Have Accomplished.” Brookings [Online]. Accessed February 5, 2017. http://www.brookings.edu/research/articles/013/02/21-millennium-dev-goals-mcarthur.

- McCullum, H. 2005. Education in Africa: Colonialism and the Millennium Development Goals. [Online] Accessed March 20, 2017. www.newsfromafrica.org/newsfromafrica/articles/art_9909.html.

- MDG Report. 2007. Millennium Development Goals: 2007 Progress Chart. [Online]. Accessed April 30, 2017. www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG_Report_2007

- NewsRescue. 2009. How the IMF, World Bank and Structural Adjustment Programs (SAP) destroyed Africa. [Online] Accessed April 10, 2017. newsrescue.com/how-the-imf-world-bank-and-structural-adjustments-programsap-destroyed-africa/Haxzz5FDZRBRZi

- Nigeria Millennium Development Goals End Report. 2015. Abuja: Office of the Senior Special Assistant to the President.

- Nkrumah, K. 1965. Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. London: Nelson Books.

- Ogunrotifa, A. B. 2012. “Millennium Development Goals in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Critical Assessment.” Radix International Journal of Research in Social Sciences 1 (10): 1–22.

- Ogunrotifa, A. B. 2015. “Grand developmentalism: MDGs and SDGs in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Pambazuka News. http://www.pamazuka.org/governance/grand-developmentalism-mdgs-sdgs-sub-saharan-africa.

- Okeke, M. S., and U. Nwali. 2013. “Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the UN Post-2015 Global Development Agenda: Implications for Africa.” American Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 1 (2): 67–73. doi: 10.11634/232907811301306

- Orji, I. J. 2005. “An Assessment of Impacts of Poverty Reduction Programmes in Nigeria as a Development Strategy, 1970–2005.” PhD Thesis, St Clements University, Turks and Caicos Island.

- Oshewolo, S. 2011. “Poverty Reduction and the Attainment of the MDGS in Nigeria: Problems and Prospects.” International Journal of Politics and Good Governance 2 (2): 1–22.

- Phillips, J. 2011. “Iran Blasts U.S intervention in Libya while escalating its meddling in Neighbour Affairs.” Daily Signal, March 23. https://www.google.co.za/amp/dailysignal.com/2011/03/23/iran-blasts-us.

- Poku, N., and J. Whitman. 2011. “The Millennium Development Goals: Challenges, Prospects and Opportunities.” Third World Quarterly 32 (1): 3–8. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2011.543808

- Prebisch, R. 1950. The Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems. NewYork: United Nations.

- Rippin, N. 2013. Progress, Prospects and Lessons from the MDGs. Background Research Paper submitted to High level panel on Post-Development Agenda [Online]. www.post015hlp.org/…/Rippin_Progress_Prospects-and-Lessons-from-t…

- Rodney, W. 1976. How Europe underdeveloped Africa. Washington: Howard University Press.

- Sachs, J. D. 2012. “From Millennium Development Goals to Sustainable Development Goals.” The Lancet 379 (9832): 2206–2211.

- Sachs, J. 2015. The Age of Sustainable Development. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Sangado, K., S. Nsanzabaganwa and E. Myyisi. 2003. Rwanda: Country position. In: Regional workshop on Ageing and Poverty. Dar es Salaam. Tanzania, October 29–31, 2003.

- Schmidt, D. 2008. “Why Africa is unlikely to achieve the Millennium Development Goals?” [Online]. Accessed February 5, 2017. https://www.grin.com/en/e-book/92145/why-africa-is-unlikely-to-acheive-the-millennium-development-goals.

- Sen, A. 1984. Poverty and Famines; An Essay in Entitlement and Deprivation. Oxford: Claredon Press.

- Sen, A. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

- Shah, A. 2001. Causes of poverty: Poverty facts and stats. [Online]. http://www.global issues. org/Trade Related/Facts.asp.

- Singer, H. 1950. “The Distribution of Trade Between Investing and Borrowing Countries.” American Economic Review 40: 473–485.

- Soubbotina, T. P. 2004. Beyond Economic Growth: An Introduction to Sustainable Development. Washington: The World Bank.

- Stats SA. 2014. Education: A Road Map Out of Poverty? [Online] Accessed March 20, 2017. www.statssa.gov.za/?p=2566

- The Millennium Development Goals Report. 2015.

- Thomas, A. 2004. “The Study of Development.” DSA annual conference, House, London, November 6.

- Tissignton, K. 2011. Basic Sanitation in South Africa: A Guide to Legislation, Policy and Practice. Johannesburg: Socio-economic Rights Institute of South Africa.

- Todaro, M. P. and S. C. Smith. 2005. Economic Development. 9th ed. United States: Pearson Education.

- Todaro, M. P., and S. C. Smith. 2009. Economic Development. 10th ed. London: Pearson Education.

- Torpey, E., and A. Watson. 2014. “Education level and Jobs Opportunities by State.” Career Outlook [Online]. https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2014/article/education-level-and-jobs.htm.

- Ucha, C. 2010. “Poverty in Nigeria: Some Dimensions and Contributing Factors.” Global Majority 1 (1): 46–56.

- Udodilim, N. 2016. “Navigating Nkrumah’s Theory of Neo Colonialism in the 21st Century.” E-international Relations Students. [Online]. Accessed March 30, 2017. https://www.e-ir.info/2016/01/13/navigating-nkrumahs-theory-of-neo-colonialism-in-the-21st-century/

- UN. 2000. UN Millennium Declaration. New York: United Nations.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 1990. Human Development Report. New York: Oxford University Press.

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2016. Africa Human Development Report. [Online]. http://hdr.undp.org/en/2016-report

- UNMP (UN Millennium Project). 2005. Investing in Development: A Practical Plan to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals. London: Earthscan.

- UN-NGLS. 2010. MDG Targets and Indicators. [Online]. Accessed May 9, 2018. https://unngls.org/index.php/background-mdg10/1386

- Vanguard. 2017. Dollar Crashes, Naira gains at Parallel Market [Online]. Accessed March 7, 2017. www.vanguardngr.com/2017/03/dollar-crashes-naira-gains-parallel-market/.

- Waage, J., R. Banerji., O. Campbell., E. Chirwa., G. Collender., V. Dieltens., … and E. Unterhalter. 2010. “The Millennium Development Goals: A Cross Sectoral Analysis and Principles for Goal Setting after 2015.” The Lancet 376 (9745): 991–1023.

- Willis, K. 2011. Theories and Practices of Development. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- World Bank. 2016. The Uganda Poverty Assessment Report, Farms, Cities and Good Fortune: Assessing Poverty Reduction in Uganda from 2006 to 2013. Abridged version [Online]. Accessed February 7, 2017. pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/890971474327477241/Uganda-poverty-assessment-report-2016-overview.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2014. Progress Towards the Achievement of the Health Related Millennium Development Goals. In: Regional Committee for Africa. Sixty-Four Session. Cotonou. Republic of Benin.