Abstract

In the early stage of business, which is where most new ventures fail, many entrepreneurs experience discrepancies between their entrepreneurial expectations and business realities. These discrepancies referred to by this paper as an entrepreneurial gap (EG) are, therefore, among other factors, professed to be responsible for the high attrition rate of emerging ventures in South Africa. An oversight in this area of EG, despite the provision of most required resources, may still lead to business failure. This paper argues that there is more yet to be comprehended regarding early-stage business success, concerning the entrepreneur component. The purpose of this paper was to recognize and classify factors responsible for establishing entrepreneurial gaps with the intent to improve the level of preparedness among emerging entrepreneurs. A qualitative approach with in-depth interviews was employed in the data collection. ATLAS ti 8 was used to unpack factors that instigate entrepreneurial gaps while posing challenges to emerging entrepreneurs in the early stage of business. The groups identified were: entrepreneur management, familism and personal management. The findings provide information that is credible to improving the level of preparedness among emerging entrepreneurs, and could be used by mentors, coaches and relevant support structures.

Introduction

In South Africa, a concurrence among scholars exists which illuminates an alarming rate of three in every four early-stage businesses collapsing (Fatoki and Garwe Citation2010; Luiz and Mariotti Citation2011; Mthabela Citation2015; Kalitanyi and Bbenkele Citation2017; Mamabolo, Kerrin, and Kele Citation2017). In support of this account are some scholars and organizations (Arasti Citation2011; Radipere and Ladzani Citation2014; Kalane Citation2015; Hyder and Lussier Citation2016; GEDI Citation2017) that previously argued on the cause(s) of business failure and challenges, identifying a lack of finance and poor access to markets as the causes of failure. But these accounts convincingly relate to business failure and not necessarily the individual entrepreneur who gives in to failure. In terms of causes of failure emanating from the entrepreneur component, the lack of marketing skills, among others, should be investigated.

Moreover, Schwartz and Hornych (Citation2010), Cant (Citation2012) and Chimucheka and Mandipaka (Citation2015) persuasively argue that the lack of such marketing skills is a convincing dead end for the entrepreneurship journey. In this case, the entrepreneur who aligned business success to his or her marketing skills, might give in to failure and divert from entrepreneurship if his or her marketing skills do not materialize as expected. Then again, it is according to this conception – the presence of marketing skills – that Cheung and Jim (Citation2013), Sheena, Mariapan, and Aziz (Citation2015) and Zhang et al. (Citation2015) boldly state that simply being a good marketer will not necessarily make one’s business a success as there is more to achieving such a status.

Against this background, it is evident that within the first three years of founding a business, which is when most new ventures fail, Neneh (Citation2011) and Kambourova and Stam (Citation2016) accentuate that many entrepreneurs experience discrepancies between their entrepreneurial expectations and business realities. These discrepancies could be derived from the expectation that running a successful business depends on the entrepreneur’s key capabilities – as mentioned earlier – such as being a good marketer which attributes to business skills (Hyder and Lussier Citation2016). Nonetheless, a successful business is a product of many elements such as strategizing, budgeting, the entrepreneur’s ability to implement necessary changes and being resourceful within effective marketing (Trevelyan Citation2008; Vermeulen and Curseuurseu Citation2010; Salamouris Citation2013; Ngwira Citation2016).

These differences or discrepancies for that matter referred to by this paper as an entrepreneurial gap (EG) between entrepreneurial expectations and business realities faced in the early stage of entrepreneurship, are, therefore, among other factors, deemed responsible for the high attrition rate of emerging ventures in South Africa. For instance, ‘consistent negative feedback’Footnote1 on business performance such as constant work demands and unrealized business expectations, would at a certain point derail the emerging entrepreneur who would possibly opt to discontinue business activities. This variance is given prominence by Ucbasaran et al. (Citation2010) as they indicated unmet business venture expectations (entrepreneurial gap) of the entrepreneur to be the blanketing challenge leading to business failure. Furthermore, Ucbasaran et al. (Citation2013) denoted business failure due to unmet expectations as the discontinuity of ownership due to poor performance below the threshold, which is directly linked to ineffective/failure to effect business adjustments by the entrepreneur.

An oversight in this area of EG, despite the provision of most required resources and access to markets for emerging ventures, may still lead to business failure. This paper thereby argues that there is more yet to be comprehended regarding early-stage business success, concerning the entrepreneur component. Therefore, the notion that research work has overlooked one important factor – entrepreneurs’ inability or ability to adapt to the volatile business environment, instituted on micro factors – becomes of interest to explore. Pragmatically, one then should understand the factors evolving around EG taking a micro-perspective lens on the emerging entrepreneur. To attend to the dearth in empirical evidence towards understanding EG issues, this paper was grounded on the need to address the research question: what are the factors that South African entrepreneurs struggle with during the early stage of business formation? Therefore, the purpose of this paper was to recognize and classify factors responsible for the establishment of entrepreneurial gaps with the intent to improve the level of preparedness among early-stage business entrepreneurs.

Literature

The argument of this paper focuses mainly on the entrepreneur component. Micro factors of entrepreneurs occupy a considerate role in developing entrepreneurial expectations which, in turn, would motivate and possibly retain individuals in entrepreneurship. This then creates a need to expand on these factors, while examining the effects that they have on the entrepreneur within the early stage of business. In that sense, Farouk, Ikram, and Sami (Citation2014) outline several factors that exist within the entrepreneur’s sphere of control. The scholars’ focus was on identifying factors that influence the intent to start an entrepreneurial venture among university students. It is noteworthy that their research paper made use of the Theory of Planned Behaviour which promotes an understanding of how an individual will perform for a certain action based on micro aspects.

It is important to note that what these scholars’ research paper outlined, are indeed factors that influence an individual’s actions. However, what this paper intends to achieve, is to illustrate that when that individual has the intent to set up a small business, and proceeds to do so, there comes a time where changes occur along the entrepreneurship process. For example, what might have influenced the entrepreneur to tackle entrepreneurship in the first place, might no longer exist, resulting in a discrepancy. If the entrepreneur then fails to adjust accordingly, then that intent to pursue the entrepreneurial journey could be short-lived. To illuminate the entrepreneurship gaps, the discrepancy theory establishes the ambit of this paper and is presented next.

Discrepancy theory

Discrepancy theory has been applied for understanding the individual (entrepreneur) concerning the expectations against achieved standards, presented by the business component (Fast et al. Citation2014). Cooper and Artz (Citation1995) suggested that discrepancies are primarily based on goals and expectations. A discrepancy in this matter is a perceived difference of set standards (goal) and the level of accomplishment attained thereof or an expectation-reality gap (what was expected – not necessarily a goal – differs from what materialized).

Discrepancy theorists articulate that the existence of such a difference may lead to emotive or active reactions, even to an extent of dismissal of set standards. This outcome is derived from various sources, e.g. social pressure, threshold requirements and personal expectations (Locke Citation1969; Oliver Citation1981). The discrepancy theory thereby suitably sets the thought process for this paper, as it adequately provides a framework for understanding the discrepancies faced by an emerging entrepreneur in the world of business. Therefore, upon the realization of a discrepancy which in this context is an EG, there are consequences that an emerging entrepreneur should encounter. In such circumstances, entrepreneurial abilities to deal with the consequences become significant. The situation may further be exacerbated if the entrepreneur was not adequately prepared (Nheta Citation2020). Thus, micro factors play a considerable role in influencing the intent of an individual, while simultaneously influencing the ability of an individual to cope with business struggles, specifically in the early stage of business.

Equally important to note is how entrepreneurs exist and respond to diverse influential structures. In a similar study by Talebi, Nouri, and Kafeshani (Citation2014) that sought to identify individual factors influencing entrepreneurs’ decision-making skills, various factors like cognitive and personal characteristics were indicated. Some of these factors are shaped by social structures and enhanced by institutional structures (Belas et al. Citation2017; Tur-Porcar, Roig-Tierno, and Mestre Citation2018). It is such findings that allude to the critical role played by micro factors in an entrepreneur’s journey.

Personal factors

Personal factors contribute to the entrepreneur’s way of dealing with matters. Scholars in the field of entrepreneurship have given a reference to traits of an individual playing an integral role in influencing the success of an entrepreneur (Belas et al. Citation2017; Chaudhary Citation2017; Tur-Porcar, Roig-Tierno, and Mestre Citation2018). Complementary factors such as the level of income, education and managerial experience are considered to also influence and shape the intents and expectations of an emerging entrepreneur (Hermans et al. Citation2015).

In the works of Carree and Verheul (Citation2012), they sought to investigate factors which influence satisfaction levels of emerging entrepreneurs. The degree of measurement used to assess the participants of their study, solely focused on entrepreneurs’ expectations. This was captured in five categories, with the first category measuring outcomes that were ‘much worse than expected’, and the fifth category measuring those that were ‘far better than expected’. Interesting to note is that the scholars’ purpose was to identify the determinants of satisfaction among emerging entrepreneurs to establish a key measure of individual entrepreneurship success. Their argument was based on the view that the existing literature at the time their study was conducted, concentrated on determining the satisfaction of employees, rather the entrepreneurs.

Furthermore, they supported their argument by indicating that even though satisfaction was mainly measured by the performance of the venture, individual factors also influenced satisfaction levels. In their study, the scholars empirically examined how income, psychological well-being and leisure time influence individual entrepreneurship success. In an attempt to coin determinants of satisfaction, the scholars outlined the influence of intrinsic and extrinsic motives. A special note was made on the differentiation of entrepreneurs with regard to type or complexity of the business, as well as the commitment towards the business (full-time or part-time managers).

The note was made to address the different levels of satisfaction that exist among heterogenous entrepreneurial ventures. At this point, the scholars’ study simply addressed the determinants of satisfaction and did not unravel how such findings could be directed towards improving the preparedness of emerging entrepreneurs. Broadly stated, personal factors that influence the level of preparedness among entrepreneurs in the early stage of business include: self-efficacy, risk-taking ability, personal optimism, overconfidence, escalation of commitment, planning skills, freedom and sense of achievement (Townsend, Busenitz, and Arthurs Citation2010; Carree and Verheul Citation2012; Rietveld et al. Citation2013; Ucbasaran et al. Citation2013; Talebi, Nouri, and Kafeshani Citation2014; Hermans et al. Citation2015; Bradley and Klein Citation2016; Dawson Citation2017; Farzana Citation2018; Shava and Chinyamurindi Citation2019) However, of interest to this paper is how expectations were used to measure satisfaction towards individual entrepreneurship success. This then highlights the importance of addressing EG issues to improve, among other factors, the levels of preparedness during the early stage of business.

Social structures

Social structures have a certain degree of influence on the character and expectation of any individual. Shapero and Sokol (Citation1982) pointed out that the perceptions that an individual has of persons or social groups (friends, family, referrals) are influenced by cultural and societal variables. Subjective norms increasingly hold significance for the outcome of the character of the entrepreneur. However, the character is not necessarily in question at this point, but the influence of social structures towards shaping the expectations of the entrepreneur and likewise framing the micro perspectives of the individual are important. As pointed earlier in the personal factors’ section, an entrepreneur might demonstrate or possess some of the factors indicated. However, the extent of the effect the respective personal factors have on the entrepreneur, are subject to the social structures that an individual has experienced (Hermans et al. Citation2015).

Due to the interplay of entrepreneurship and social structures, scholarly works have put forward the issue of social embeddedness in entrepreneurship (Mckeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014). The understanding thereof is based on how entrepreneurs are anchored within social structures that provide both opportunities and constraints or threats. Also, entrepreneurs are connected to the various sources of motivation intertwined within their social networks. The impact of social structures on the entrepreneur, therefore, has an effect, depending on how deeply rooted the entrepreneur interacts with a specific social aspect – the extent of congruence with the social structures by the entrepreneur (Kazeem and Asimiran Citation2016).

Social structures consist of networks that provide various opportunities and resources for the entrepreneur. It is within these structures where networks such as familism emerge (Canedo et al. Citation2014). As for Uzzi and Gillespie (Citation2002), their thoughts on social structures as being an integrated part of entrepreneurship, are sided with a specific view. They conferred that socialization influences the expectations of the entrepreneur by shifting the business focus from an economic perspective to a socialized and personal perspective. Therefore, the entrepreneur becomes more oriented towards the fulfilment of social expectations. For instance, an entrepreneur expecting to achieve societal recognition is likely to orientate business focus towards realizing such expectations. Understandably, different types of entrepreneurs like lifestyle entrepreneurs may suit such a descriptor. But even so, other types of entrepreneurs such as empreneurs (Chakuzira Citation2019), could become caught up in chasing societal expectations due to the extent of embeddedness within the social structure.

Consequently, networks such as familism cannot be overlooked with regard to how the social aspect influences the micro perspectives of the emerging entrepreneur (Paunecsu, Popescu, and Duennweber Citation2018). In Canedo et al. (Citation2014), familism is defined as a value expressed within the culture of a respective family. Most important is the role of overseeing individual interests which are enacted by the family. In the maintenance of familism, the individual should prioritize family values. That factor of familism thus has an undeniable influence on the entrepreneur. Therefore, Talebi, Nouri, and Kafeshani (Citation2014) signify the importance of the emerging entrepreneur’s ability to filter social aspects in the attempt to maintain a positive balance of the social network and entrepreneurship. The ability to filter or not depends on how deeply tied the emerging entrepreneur is within that social construct. Thus, the entrepreneur’s personal factors can, therefore, become aligned with heightened social expectations (Hermans et al. Citation2015; Paunecsu, Popescu, and Duennweber Citation2018). In the event of such expectations failing to materialize once more, the social structure would have its toll on the emerging entrepreneur. Comprehending this relationship of entrepreneurship and social structures, thus becomes of great value to the emerging entrepreneur and the business coaches, as well as mentors for future use.

Institutional structures

Institutions have been generally accepted to determine the rules of the game (Salamzadeh et al. Citation2015). Scholars have presented the institutional structure mainly in two perspectives – formal institutions and informal institutions. In an analogous approach routed towards social structures, institutional factors are influenced by the entrepreneur’s perception (Shapero and Sokol Citation1982). The perceptions may be oriented towards factors such as regulative, normative and cognitive which are the total of the two institutional perspectives – formal and informal (Garcia-Cabrera, Garcia-Soto, and Dias-Furtado Citation2018). Furthermore, institutional factors, e.g. tax environment, competitiveness, economic freedom, social security, fiscal policy and corruption are directly connected to entrepreneurial activities (Crnogaj and Hojnik Citation2016; GEM Citation2018). With regulative factors, the importance is on laws that encourage or discourage entrepreneurship and influence entrepreneurial development thereafter (Stenholm, Acs, and Wuebker Citation2013). With normative factors, they refer to cultural values that promote good behaviour, while cognitive factors frame business acumen shared among organizations in an area (Garcia-Cabrera, Garcia-Soto, and Dias-Furtado Citation2018).

The influence of institutional factors on entrepreneurship development is necessary whether it turns out to be a positive or negative outcome (Salamzadeh et al. Citation2015). With such level of importance placed on institutional factors, this section draws attention to how the regulative factors encourage or discourage entrepreneurship inherently, influencing the expectations of an emerging entrepreneur. The justification supporting the selection of the regulative factor is, that an entrepreneurship discourse already exists. The discourse is roused by the misunderstandings between the government’s intention towards developing entrepreneurship and the entrepreneur’s perception towards government support. Regulative factors thus present the government’s intention, while entrepreneurs have no option but to react to the intention. Similarly, micro perspectives of an emerging entrepreneur may be influenced by the regulative factors existing in the country’s laws. Additionally, the normative aspects and cognitive aspects have been partly discussed in the social structure section, as these generally overlap in the two constructs (social and institutional structures) (Garcia-Cabrera, Garcia-Soto, and Dias-Furtado Citation2018).

Expectations of emerging entrepreneurs can be framed, observing the institutional framework in which entrepreneurship is developed (Salamzadeh et al. Citation2015). For instance, an assessment by the entrepreneur on how the entrepreneurship policy influences aspects such as protection of property rights, labour markets, capital markets and the development of entrepreneurship within the geopolitical area, would influence the crafting of the individual’s micro perspectives and consequently entrepreneurial expectations. Therefore, Crnogaj and Hojnik (Citation2016) affirm that the institutional framework has a direct influence on entrepreneurial activities pursued by the respective individuals.

From the assessments of Hermans et al. (Citation2015), entrepreneurial motivations translate into entrepreneurial expectations, specifically in the start-up phase of business. Therefore, for example, if regulatory factors within the labour markets are seemingly unfavourable for a respective type of entrepreneurial venture, the entrepreneur might be discouraged to pursue business activities (Salamzadeh et al. Citation2015; GEM Citation2018). Sometimes the entrepreneur decides to pursue the entrepreneur venture and the expectations thereof will then be linked to the motivations that pushed or pulled the individual into business.

Therefore, institutional factors are decisive in influencing the micro perspectives of an emerging entrepreneur. The extent of the influence of institutional factors on the entrepreneur is thus dependent on the ability of the entrepreneur to dissect and filter respective institutional factors (Nheta Citation2020). In the advent of coaching and specialized mentoring, emerging entrepreneurs may skilfully filter factors towards increased survival chances for their business. To illustrate how micro factors, influence the entrepreneur, illustrates the conceptual framework for this paper.

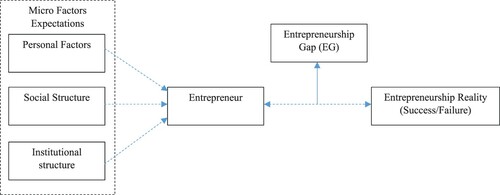

As illustrated within the conceptual framework, three key areas, namely personal factors, social structures and institutional structures are presented as a source of micro factors (Tur-Porcar, Roig-Tierno, and Mestre Citation2018). For the micro factors to emerge and shape up the respective entrepreneur, the individual should filter information from the three identified areas. The ability of the entrepreneur to filter from such sources, would in turn influence the types of micro issues – expectations – that influence the entrepreneur (Talebi, Nouri, and Kafeshani Citation2014). The presence of certain micro factors could then influence the level of preparedness an individual has towards entrepreneurship. However, the existence of an EG in between the entrepreneur and business reality poses a threat to the entrepreneur as the ability of the individual to deal with an EG becomes of significance. Nheta (Citation2020) argues that an entrepreneur who is adequately prepared for business is more likely to successfully manage EG related issues as compared to another who is inadequately prepared. Therefore, an adequately prepared entrepreneur who successfully manages EG issues is likely to improve the chances of the business surviving the early stage of formation.

Methodology

To address the purpose of this paper, a qualitative research approach was used. The justification of the approach is embedded within the need to understand the entrepreneur component (micro-perspective factors). The aim was not to quantify the factors but acquire an in-depth understanding of the factors that stimulate the development of an entrepreneurial gap and classify them. Thus, this paper employed a non-probability sampling technique grounded on purposive sampling design. This design is aimed at accessing individuals based on an existing understanding of the population – entrepreneurs, its elements, and the purpose of the study (Babbie Citation2010). The scholar defines purposive sampling as a sampling design that requires the researcher’s judgment in selecting the units for the study.

Illker, Sulaiman, and Rukayya (Citation2015) state that when using purposive sampling, supporting theories are not necessarily required to establish the sample size, especially if certain characteristics are observed in the elements of the study. This is the case for Sibindi and Aren (Citation2015) as well as for this paper. The authors applied judgment in selecting the units that would reasonably represent the population in this study, at the same time being useful to the successful progression of data collection (Babbie Citation2010). Due to the phenomenon being studied, measures were put in place to ensure that information-rich sources were accessed. Gaining access to the right sources enhanced the quality of data collected, hence sample selection criteria were used ().

Table 1: Sample selection criteria.

The pool of interviewees came from an internationally recognized entrepreneurship conference. The authors attended one of the largest gatherings with participants that were mainly emerging youth entrepreneurs in South Africa at Sandton Convention Centre in 2018. The yearly event known as Enactus South Africa national competitions, which runs for two days and provides room for emerging entrepreneurs to network with established entrepreneurs thus provided a lucrative information-rich source opportunity for data collection of this paper. A maximum of five in-depth interviews was conducted as data saturation was achieved. The interview transcripts were analyzed using ATLAS ti 8 making use of a top-down theoretical thematic analysis, which was driven by this paper’s purpose and the authors’ focus (Braun and Clarke Citation2014). Ethical aspects were considered and adhered to during and after data collection. This meant that the interviewees expressed their consent, were willing to provide data while their identity was protected throughout the process of data analysis and publication.

Discussion and findings

The purpose of this paper was to recognize and classify factors responsible for the establishment of entrepreneurial gaps with the intent to improve the level of preparedness among early-stage businesses. A review of extant literature revealed some of the areas in which these factors emerge. From the entrepreneurial sphere, factors that instigated challenges were found to be embedded within the business component and the entrepreneur component. With the business component, external factors such as government’s role in entrepreneurship were noted to be a platform that triggers off business factors that affect early-stage entrepreneurs. Issues that arose were mainly due to the supposedly misconceived perceptive of entrepreneurship development by the government and its support structure.

However, factors posing challenges while developing entrepreneurial gaps were identified to be predominant within the micro perspective of entrepreneurs. Most business factors revolve around the immediate environment of the entrepreneur. Personal factors, social structures and institutional structures were documented to be a prevalent source of intertwined business factors, which present reasonable challenges for the emerging entrepreneur instigating entrepreneurial gaps.

Since extant literature provided insight and assisted in identifying some common areas that present business factors associated with problematic issues, an attempt to unravel underlying issues were made in this paper. This paper sought to address the research question: what are the factors that South African entrepreneurs struggle with during the early stage of business formation? Factors that instigate entrepreneurial gaps while posing challenges to emerging entrepreneurs in the early stage of business were, therefore, generated for analysis. Firstly, data were transcribed verbatim. Secondly, open coding was conducted, and this was a repetitive process until open coding was completed. Extant literature was referred to during the coding process Thirdly, constant comparison with selective coding was initiated. Lastly, themes were developed. The last step marked the final process of data coding and paved the way for network diagram development and code refinement through peer audit reviews (Creswell Citation2015).

The issues identified from the network diagrams were then grouped to form three themes, namely; entrepreneur management, familism and personal management. These themes hereafter referred to as group factors were identified to be the frames in which an entrepreneurship gap is developed. presents a summary of this paper’s findings – business factors that were recognized and the group factor they were classified under – accompanied by the operational definitions. The summary provides insight into issues that emerging entrepreneurs struggle within the early stage of business inherently, leading to the existence of EG.

Table 2: Summary of factors affecting emerging entrepreneurs.

To comprehend the group factor classifications and how they relate to the institution of EG as an example, consider the group factor of personal management which consists of a business factor namely ‘Relational’. How does such a business factor cause challenges and instigate entrepreneurial gaps that emerging entrepreneurs encounter within the early stage of business? To adequately address the question, one should refer to the operational definition presented in . Consider an emerging entrepreneur who either assumes or is certain that he or she is relational, henceforth closing deals and retaining clients will be an easy task.

Such a predisposition of success concerning that area of client relationships could mislead the entrepreneur. If the success fails to materialize, challenges could arise which would require certain adjustments to be initiated by the entrepreneur. However, consistent corroboration of negative feedback regarding client relationship as an example could yield several challenges that the emerging entrepreneur would struggle with. The struggles are fortified, especially when the emerging entrepreneur was not adequately prepared, since the relational trait was expected to ‘deliver’, thus establishing EG.

As reiterated in the extant literature, the effects of such factors if inadequately addressed, could deter the entrepreneur from the business. Respectively, an emerging entrepreneur who believes is committed to business (entrepreneur management) is likely to have high expectations. When these expectations fail to materialize on the realistic side of the business, this paves way for EG development. If intervention is not rendered, it could affect the survival chances of the entrepreneur in business.

Conclusion

The generated group factors are representative of issues that instigate entrepreneurial gap development among emerging entrepreneurs within the early stage of business. Multitudes of research work have taken a similar slot of identifying such factors, but mainly from a macro-business perspective (Fatoki and Garwe Citation2010; Arasti Citation2011; Luiz and Mariotti Citation2011; Radipere and Ladzani Citation2014; Kalane Citation2015; Mthabela Citation2015; Hyder and Lussier Citation2016; GEDI Citation2017; Kalitanyi and Bbenkele Citation2017; Mamabolo, Kerrin, and Kele Citation2017). This paper, however, took a twist and focused on the union of the entrepreneur component from a micro-entrepreneur perspective and the business component at large.

The intention was to determine how an emerging entrepreneur deals with business factors and in that process, how the same individual degenerates the situation due to EG. Going against the common trends in entrepreneurship research, this paper has revealed some underlying issues with a focus on the micro-perspective factors of emerging entrepreneurs that research has generally overlooked. Policymakers, scholars and the entrepreneurs have comparably ascribed factors that challenge entrepreneurs to be mainly external, yet such an assessment is misleading. With the emergence of the generated factors, a platform has been created to further inquire on different resolutions that could be of use in improving the preparedness of emerging entrepreneurs.

Emerging entrepreneurs encounter a series of macro-business-related challenges in the early stage of business. These challenges could be dealt with reasonably if the individual – an entrepreneur – is adequately prepared. Improved levels of preparedness can be enhanced through supplement coaching and advisory services that are grounded on the business factors, generated by this paper and among other factors of relevance in arresting early-stage business failure. Thus, the generated issues provide pragmatic information that is credible in improving the level of preparedness among emerging entrepreneurs.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Feedback which contradicts what the emerging entrepreneur expected from operating a business.

References

- Arasti, Z. 2011. “An Empirical Study on the Causes of Business Failure in Iranian Context.” African Journal of Business Management 5 (17): 7488–7498.

- Babbie, E. 2010. The Practice of Social Research. 12th ed. California: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Belas, J., B. Gavurova, J. Schonfeld, K. Zvarikova, and T. Kacerauskas. 2017. “Social and Economic Factors Affecting the Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students.” Transformations in Business and Economics 16 (3): 220–239.

- Bradley, S. W., and P. Klein. 2016. “Entrepreneurship: The Contribution of Management Scholarship.” Academy of Management 3 (30): 292–315.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2014. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: SAGE.

- Canedo, J., D. L. Stone, S. Black, and K. M. Lukaszewski. 2014. “Individual Factors Affecting Entrepreneurship in Hispanics.” Journal of Management Pschology 29 (6): 755–772.

- Cant, M. 2012. “Challenges Faced by SME’s in South Africa: Are Marketing Skills Needed?” International Business and Economics Research Journal 11 (10): 1107–1116.

- Carree, M. A., and I. Verheul. 2012. “What Makes Entrepreneurs Happy? Determinants of Satisfaction among Founders.” Journal of Happiness Studies 13: 371–387.

- Chakuzira, W. 2019. “Using a Grounded Theory Approach in Developing a Taxonomy of Entrepreneurial Ventures in South Africa: A Case Study of Limpopo Province.” PhD Thesis, University of Venda.

- Chaudhary, R. 2017. “Demographic Factors, Personality and Entrepreneurial Inclination: A Study among Indian University Students.” Education and Training 59 (2): 171–187.

- Cheung, T. O. L., and C. Y. Jim. 2013. “Ecotourism Service Preference and Management in Hong Kong.” International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology 20 (2): 182–194.

- Chimucheka, T., and F. Mandipaka. 2015. “Challenges Faced by Small, Medium and Micro Enterprises in the Nkonkobe Municipality.” International Business and Economics Research Journal 14 (2): 309–316.

- Cooper, A. C., and K. W. Artz. 1995. “Determinants of Satisfaction for Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing 10: 439–457.

- Creswell, J. W. 2015. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Washington DC: SAGE Publications.

- Crnogaj, K., and B. B. Hojnik. 2016. “Institutional Determinants and Entrepreneurial Action.” Journal of Contemporary Management Issues 21: 131–150.

- Dawson, C. 2017. “Financial Optimism and Entrepreneurial Satisfaction.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 11: 171–194.

- Farouk, A., A. Ikram, and B. Sami. 2014. “The Influence of Individual Factors on the Entrepreneurial Intention.” International Journal of Managing Value and Supply Chains 5 (4): 47–57.

- Farzana, R. 2018. “The Impact of Motivational Factors Towards Entrepreneurial Intention.” Journal of Modern Accounting and Auditing 14 (12): 639–647.

- Fast, N. J., E. R. Burris, and C. A. Bartel. 2014. “Managing to Stay in the Dark: Managerial Self-efficacy, Ego Defensiveness, and the Aversion to Employee Voice.” Academy of Management Journal, 57 (4): 1013–1034.

- Fatoki, O., and D. Garwe. 2010. “Obstacles to the Growth of new SMEs in South Africa: A Principal Component Analysis Approach.” African Journal of Business Management 4 (5): 729–738.

- Garcia-Cabrera, A. M., M. G. Garcia-Soto, and J. Dias-Furtado. 2018. “The Individual’s Perception of Institutional Environments and Entrepreneurial Motivation in Developing Economies: Evidence from Cape Verde.” South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 21 (1): 1–18.

- GEDI. 2017. The Entrepreneurial Ecosystem of South Africa: A Strategy for Global Leadership 2017. [Online]. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://sabcms.blob.core.windows.net/wp-content/2017/03/GEDI-South-Africa-Analysis2.pdf.

- GEM. 2018. GEM South Africa 2017–2018 Report. [Online]. Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.gemconsortium.org/economy-profiles/south-africa.

- Hermans, J., J. Vanderstraeten, A. Witteloostuijn, M. Dejardin, D. Ramdani, and E. Stam. 2015. “Ambitious Entrepreneurship: A Review of Growth Aspirations, Intentions, and Expectations.” Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth 17: 127–160.

- Hyder, S., and R. N. Lussier. 2016. “Why Businesses Succeed or Fail: A Study on Small Businesses in Pakistan.” Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 8 (1): 82–100.

- Illker, E., A. M. Sulaiman, and S. A. Rukayya. 2015. “Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling.” American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics 5 (1): 1–4.

- Kalane, L. 2015. “Reasons for Failure of SMEs in the Free State.” Master thesis, University of Free State, Bloemfontein.

- Kalitanyi, V., and E. Bbenkele. 2017. “Assessing the Role of Socio-Economic Values on Entrepreneurial Intentions among University Students in Cape Town.” South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences 20 (1): 1–9.

- Kambourova, Z., and E. Stam. 2016. “Entrepreneurs’ Overoptimism During the Early Life Course of the Firm.” Discussion Paper 16-14: 1–19.

- Kazeem, A. A., and S. Asimiran. 2016. “Factors Affecting Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy of Engineering Student.” International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 6 (11): 519–534.

- Locke, E. 1969. “What is Job Satisfaction?” Organizational Behavior & Human Performance 4 (4): 309–336.

- Luiz, J., and M. Mariotti. 2011. “Entrepreneurship in an Emerging and Culturally Diverse Economy:a South African Survey of Perceptions.” South African Journal of Economics and Management 1: 47–65.

- Mamabolo, M. A., M. Kerrin, and T. Kele. 2017. “Entrepreneurship Management Skills Requirements in an Emerging Economy: A South African Outlook.” Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management 9 (1): 1–10.

- Mckeever, L., A. R. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2014. “Social Embeddedness in Entrepreneurship Research: The Importance of Context and Community.” In Handbook of Research on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, edited by E. Chell, and M. Kasatas-Ozkan 222–236. Cheltenham: UK: Edward Elgar.

- Mthabela, T. E. 2015. “Assessing the Causal Failures of Emerging Manufacturing Smes in Johannesburg.” Master thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Neneh, B. N. 2011. “The Impact of Entrepreneurial Characteristics and Business Practices on the Long Term Survival of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs).” Master dissertation, University of Free State, Bloemfontein.

- Ngwira, K. P. 2016. The Road to Entrepreneurship: A Sure Way to Become Wealth at Individual Business and State Levels. Bloomington: AuthorHouse.

- Nheta, D. S. 2020. “Entrepreneurship Gaps Framework: An Exploration into Expectations vis-à-vis Realities of Entrepreneurship.” Thesis, University of Venda, Thohoyandou.

- Oliver, R. 1981. “Measurement and Evaluation of Satisfaction Processes in Retail Settings.” Journal of Retailing 57 (3): 25–48.

- Paunecsu, C., M. C. Popescu, and M. Duennweber. 2018. “Factors Determining Desirability of Entrepreneurship in Romania.” Sustainability 10: 1–22.

- Radipere, N. S., and W. Ladzani. 2014. “The Effects of Entrepreneurial Intention on Business Performance.” Journal of Governance and Regulation 3 (4): 210–222.

- Rietveld, C. A., P. J. Groenen, P. D. P. Koellinger, M. J. H. M. Loos, and A. R. Thurik. 2013. “Living Forever: Entrepreneurial Overconfidence at Older Ages (No. ERS-2013-012STR).” ERIM Report Series Research in Management.

- Salamouris, I. S. 2013. “How Overconfidence Influences Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship 2 (8): 1–6.

- Salamzadeh, A., J. Y. Farsi, M. Motavseli, M. R. Markovic, and H. K. Kesim. 2015. “Institutional Factors Affecting the Transformation of Entrepreneurial Universities.” International Journal of Business and Globalisation 14 (3): 271–291.

- Schwartz, M., and C. Hornych. 2010. “Cooperation Patterns of Incubator Firms and the Impact of Incubator Specialization: Empirical Evidence from Germany.” Technovation 30: 485–495.

- Shapero, A., and L. Sokol. 1982. The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship, Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

- Shava, H., and W. T. Chinyamurindi. 2019. “The Influence of Economic Motivation, Desire for Independence and Self-Efficacy on Willingness to Become an Entrepreneur.” The Southern African Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management 11 (1): 1–14.

- Sheena, B., M. Mariapan, and A. Aziz. 2015. “Characteristics of Malaysian Ecotourist Segments in Kinabalu Park, Sabah.” Tourism Geographies 17 (1): 1–18.

- Sibindi, A. B., and A. O. Aren. 2015. “Is Good Corporate Governance Practice the Panacea for Small-to-Medium Businesses Operating in the South African Retail Sector?” Corporate Ownership and Control 12 (2): 579–589.

- Stenholm, P., Z. J. Acs, and R. Wuebker. 2013. “Exploring Country-Level Institutional Arrangements on the Rate and Type of Entrepreneurial Activity.” Journal of Business Venturing 28: 176–193.

- Talebi, K., P. Nouri, and A. Kafeshani. 2014. “Identifying the Main Individual Factors Influencing Entrepreneurial Decision Making Biases: A Qualitative Content Analysis Approach.” International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 4 (8): 1–11.

- Townsend, D. M., L. W. Busenitz, and J. D. Arthurs. 2010. “To Start or Not to Start: Outcome and Ability Expectations in the Decision to Start a New Venture.” Journal of Business Venturing 25: 192–202.

- Trevelyan, R. 2008. “Optimism, Overconfidence and Entrepreneurial Activity.” Management Decision 46 (7): 986–1001.

- Tur-Porcar, A., N. Roig-Tierno, and A. L. Mestre. 2018. “Factors Affecting Entrepreneurship and Business Sustainability.” Journal of Sustainability 10: 1–12.

- Ucbasaran, D., D. A. Shepherd, A. Locket, and J. S. Lyon. 2013. “Life After Business Failure: The Process and Consequences of Business Failure for Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Management 39 (1): 163–202.

- Ucbasaran, D., P. Westhead, M. Wright, and M. Flores. 2010. “The Nature of Entrepreneurial Experience, Business Failure and Comparative Optimism.” Journal of Business Venturing 25: 541–555.

- Uzzi, B., and J. Gillespie. 2002. “Knowledge Spill Over in Corporate Financing Networks: Embeddedness and the Firm’s Debt Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 23: 595–618.

- Vermeulen, P. A. M., and P. L. Curseuurseu. 2010. Entrepreneurial Strategic Decision-Making: A Cognitive Perspective. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Zhang, A., L. Zhong, Y. Xu, L. Dang, and B. Zhou. 2015. “Identifying and Mapping Wetland-Based Ecotourism Areas in the First Meander of the Yellow River: Incorporating Tourist Preferences.” Journal of Resources and Ecology 6 (1): 21–29.