Since 2011 the topic of ‘stranded assets’ created by environment-related risk factors, including physical climate change impacts and societal responses to climate change, has risen up the agenda dramatically. The concept has been endorsed by a range of significant international figures, including: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon (McGrath Citation2014); US President Barack Obama (Friedman Citation2014); Jim Kim, President of the World Bank (World Bank Citation2013a; World Bank Citation2013b); Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chair of the G20 Financial Stability Board (Carney Citation2015); Angel Gurría, Secretary-General of the OECD (Gurría Citation2013); Christiana Figueres, former Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC (Figueres Citation2013); Lord Stern of Brentford (London School of Economics Citation2013); and Ben van Beurden, CEO of Shell plc (Mufson Citation2014).

The emergence of the topic should be of significant interest to scholars and practitioners alike, as it has influenced many pressing topics facing investors, companies, policy-makers, regulators, and civil society in relation to global environmental change, for example:

Measuring and managing the exposure of investments to environment-related risks across sectors, geographies, and asset classes so that financial institutions can avoid stranded assets (e.g. see Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2011; Caldecott Citation2011; Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry Citation2013; Generation Foundation Citation2013; Financial Stability Board Citation2015).

Financial stability implications of stranded assets and what this means for macroprudential regulation, microprudential regulation, and financial conduct (e.g. see Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2011; Caldecott Citation2011; Bank of England Citation2015b; Kruitwagen, MacDonald-Korth, and Caldecott Citation2016).

Reducing the negative consequences of stranded assets created as societies transition to more environmentally sustainable economic models by finding ways to effectively address unemployment, lost profits, and reduced tax income that are associated with asset stranding (e.g. see Caldecott Citation2015).

Internalising the risk of stranded assets in corporate strategy and decision-making, particularly in carbon intensive sectors susceptible to the effects of societal action on climate change (e.g. see Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2013; Ansar, Caldecott, and Tibury Citation2013; Rook and Caldecott Citation2015).

Underpinning arguments by civil society campaigns attempting to secure rapid economy-wide decarbonisation in order to reduce the scale of anthropogenic climate change (e.g. see Ansar, Caldecott, and Tibury Citation2013).

Keeping track of progress towards emission reduction targets and understanding how ‘committed emissions’Footnote1 should influence decarbonisation plans developed by governments, as well as companies and investors (e.g. see Davis, Caldeira, and Matthews Citation2010; Davis and Socolow Citation2014; Pfeiffer et al. Citation2016).

These are some of the most important topics in current policy, investor, industry, and civil society discourses on the environment and look set to remain so for as long as societies continue to transition towards greater environmental sustainability.

What are stranded assets?

There are a number of definitions of stranded assets that have been proposed or are used in different contexts. Accountants have measures to deal with the impairment of assets (e.g. IAS16) which seek to ensure that an entity’s assets are not carried at more than their recoverable amount (Deloitte Citation2016). In this context, stranded assets are assets that have become obsolete or non-performing, but must be recorded on the balance sheet as a loss of profit (Deloitte Citation2016). The term ‘stranded costs’ or ‘stranded investment’ is used by regulators to refer to ‘the decline in the value of electricity-generating assets due to restructuring of the industry’ (Congressional Budget Office Citation1998). This was a major topic for utilities regulators as power markets were liberalised in the United States and UK in the 1990s.

In the context of upstream energy production and from an energy economist’s perspective the IEA (Citation2013) defines stranded assets as ‘those investments which have already been made but which, at some time prior to the end of their economic life (as assumed at the investment decision point), are no longer able to earn an economic return’ (IEA Citation2013, 98). The Carbon Tracker Initiative also use this definition of economic loss, but says they are a ‘result of changes in the market and regulatory environment associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy’ (Carbon Tracker Initiative Citationn.d.). The Generation Foundation (Citation2013) defines a stranded asset ‘as an asset which loses economic value well ahead of its anticipated useful life, whether that is a result of changes in legislation, regulation, market forces, disruptive innovation, societal norms, or environmental shocks’ (Generation Foundation Citation2013, 21).

Different definitions for economists (‘economic loss’), accountants (‘impairment’), regulators (‘stranded costs’), and investors (‘financial loss’) make it difficult for different disciplines and professions to communicate between each other about very similar and overlapping concepts. Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry (Citation2013) proposed a ‘meta’ definition to encompass all of these different definitions, ‘stranded assets are assets that have suffered from unanticipated or premature write-downs, devaluations, or conversion to liabilities’ (Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry Citation2013, 7). This is the definition generally used throughout this Special Issue and the definition most widely used in the literature.

While the environmental discourse appropriated the term in the 2010s and is focused on the environment-related risk factors that can strand assets, asset stranding in fact occurs regularly as part and parcel of economic development. As such it is not a novel phenomenon. Schumpeter (Citation1942) coined the term ‘creative destruction’ and implicit in his ‘essential fact about capitalism’ (Schumpeter Citation1942, 83) is the idea that value is created, as well as destroyed, and that this dynamic process drives forward innovation and economic growth. Schumpeter built on the work of Kondratiev (Citation1926) and the idea of ‘long waves’ in the economic cycle (Perez Citation2010).

Neo-Schumpeterians have attempted to understand the dynamics of creative destruction, particularly how and why technological innovation and diffusion results in technological revolutions. This gave rise to the idea of ‘techno-economic paradigms’ (TEPs), a term coined by Perez (Citation1985), which captures the idea of overlapping technological innovations that are strongly inter-related and interdependent resulting in technological revolutions. Perez (Citation2002) finds five such TEPs: the Industrial Revolution (1771–1829); the Age of Steam and Railways (1829–1875); the Age of Steel, Electricity, and Heavy Engineering (1875–1908); the Age of Oil, the Automobile, and Mass Production (1908–1971); and the Age of Information and Telecommunications (1971–present).

Each TEP was accompanied by the emergence of new sectors and stranded assets in redundant ones. For example, the Industrial Revolution ushered in mechanised cotton production in England that eclipsed India’s cottage textile industry (Broadberry and Gupta Citation2005); the Age of Steam and Railways introduced railway networks that replaced canals and waterways (Bagwell and Lyth Citation2002); the Age of Steel, Electricity, and Heavy Engineering saw the end of sailing ships and the dominance of steam ships (Grübler and Nakićenović Citation1991); the Age of Oil, the Automobile, and Mass Production resulted in the rise of the automobile and the decline of railways (Wolf Citation1996); and our Age of Information and Telecommunications has seen the widespread adoption of digital communication and an information revolution, making analogue communication redundant and technologies from typewriters to telegraphs entirely obsolete. Within each TEP specific companies and brands, physical infrastructure, plant and machinery, and human capital, among other things, have become stranded.

Clearly then, stranded assets can be caused by many factors related to innovation and commercialisation, and these are part of the process of creative destruction articulated in Perez’s TEPs and conceived by Schumpeter. Recent research on stranded assets has, however, sought to explore the idea that some of the causes of asset stranding are increasingly environment-related. In other words, that a combination of physical environmental change and societal responses to this environmental change might be qualitatively and quantitatively different from previous drivers of creative destruction we have seen in TEPs. Moreover, such environment-related factors appear to be stranding assets across all sectors, geographies, and asset classes simultaneously and perhaps more quickly than in previous TEPs, and that this trend is accelerating – something that could be unprecedented.

Carbon budgets and stranded assets

From the late 1980s individuals and organisations working on climate and sustainability issues began to acknowledge the possibility that environmental policy and regulation could negatively influence the value or profitability of fossil fuel companies to the point that they could become impaired (Krause, Bach, and Koomey Citation1989; IPCC Citation1999; IPCC Citation2001; IEA Citation2008). With the concept of a global ‘carbon budget’ – the amount of cumulative atmospheric CO2 emissions allowable for certain amounts of anthropogenic climate change – there was a way to determine when impairments ought to begin given a certain climate change target (Allen et al. Citation2014). When the amount of fossil fuels combusted, plus the amount of carbon accounted for in reserves yet to be burned exceeded the carbon budget, either the climate or the value of fossil fuel reserves would have to give. This concept was dubbed ‘unburnable carbon’ by the Carbon Tracker Initiative (Citation2011) and was popularised by the US environmentalist McKibben (Citation2011), among others, in the early 2010s.

Unburnable carbon quantified the disconnect between the current value of the listed equity of global fossil fuel producers and their potential commercialisation under a strict carbon budget constraint (Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2011; Caldecott Citation2011). The idea that ‘unburnable’ fossil fuel reserves could become stranded assets sparked a significant discussion on the risk of investing in fossil fuels (Ansar, Caldecott, and Tibury Citation2013). It has also helped to spur the development of the fossil fuel divestment campaign (Ansar, Caldecott, and Tibury Citation2013).

Conjoined with and in parallel, the idea of a ‘carbon bubble’ also gained traction. This is the hypothesis that unburnable carbon would mean that upstream fossil fuel assets were significantly overvalued, potentially creating a financial bubble with systemic implications for the global economy (Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2011; Caldecott Citation2011). This has inspired divergent responses – from qualified support to outright opposition (e.g. see Caldecott Citation2012; King Citation2012; Royal Dutch Shell plc Citation2014; Exxon Mobil Corporation Citation2014; Weyzig et al. Citation2014; EAC Citation2014).

Unburnable carbon and the carbon bubble were considered to be derived from work conducted and produced in the early 2010s. However, unknown to the proponents of this discourse in the early 2010s, these ideas actually originated much earlier. This only became clear in 2013–2014 and was confirmed by interviews with authors of previously published work.Footnote2

Krause, Bach, and Koomey (Citation1989) were the first to explicitly make the case for unburnable carbon when they said,

The mere fact that remaining allowable global carbon emissions are so limited means that any economic infrastructures built up mainly on the basis of fossil fuels risk early obsolescence. In effect, the tight carbon budgets implied by climate stabilization greatly reduce the long-term value of fossil fuels. (Krause, Bach, and Koomey Citation1989, 164)

capital owners in the fossil industries would have to bear an indirect cost i.e. die risks and uncertainties of having to diversify into other business activities. For example, even a well-planned retrenchment [from fossil fuels] could create impacts on the value of stocks in the financial markets. Government financial incentives could be required to make these risks acceptable to capital owners. (Krause, Bach, and Koomey Citation1989, 172–173)

[a carbon budget] means major restrictions on the use of global fossil resources … [our carbon budget] figures clash with the conventional assumption that all conventional oil and gas resources would probably be consumed before a major shift away from fossil fuels would occur. Our analysis suggests that climate stabilization requires keeping significant portions of even the world’s conventional fossil resources in the ground. Such a requirement is a stark contradiction to all conventional energy planning and illustrates the magnitude of the greenhouse challenge. (Krause, Bach, and Koomey Citation1989, 144)

From unburnable carbon towards environment-related risk

One tension within the 2010s discourse of stranded assets is the scope of risks that can cause asset stranding. Early on, some preferred to focus on the idea of scientifically derived carbon budgets being directly enforced top-down by governments in a coordinated way (in particular, see Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2011). Others have been much more sceptical of coordinated international action and saw carbon budgets being introduced indirectly bottom-up through a panoply of different local and national policies, technological change and innovation, and social pressure, among other things (in particular, see Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry Citation2013). The views of individuals and organisations has trended towards the latter view over time (see Hedegaard Citation2015), including those that originally preferred the ‘direct top-down’ model over the ‘indirect bottom-up’ one (e.g. see Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2015).

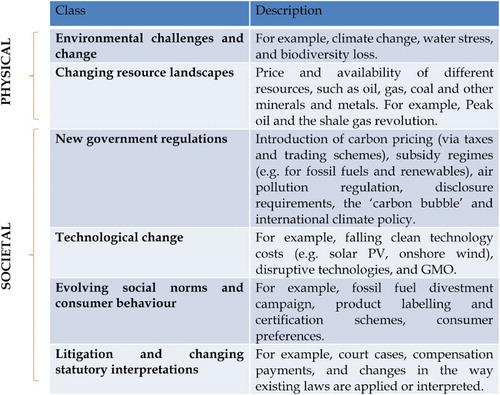

Relatedly, another tension has been the relative status of climate change versus the environment more broadly. Some have been more concerned with stranded assets created by international climate change policy (Carbon Tracker Initiative Citation2011), others have been more interested in the range of societal responses to physical climate change impacts that extend beyond unburnable carbon (Bank of England Citation2015b), and others have been concerned with both physical environmental change and societal responses to such environmental change (Bank of England Citation2015a; Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry Citation2013). Again, the views of individuals and organisations has trended towards the latter view, which is more comprehensive and expansive, and has allowed for a wider range of interests to be engaged on the topic, such as those concerned with water risk and stranded water assets (see Lamb Citation2015) or in sectors that might be affected beyond fossil fuels, such as agriculture (see Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry Citation2013; Rautner, Tomlinson, and Hoare Citation2016; Morel et al. Citation2016). To underpin a more expansive interpretation Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry (Citation2013) proposed a typology for different environment-related risks that could cause stranded assets and this is set out below ().

Figure 1. Typology of Environment-related Risk. Source: Caldecott, Howarth, and McSharry (Citation2013).

Recent developments very clearly illustrate that environment-related risks, and not just those related to unburnable carbon, can have a significant impact on assets today, and these are likely to increase in significance over time (Caldecott et al. Citation2017). If anything, the available evidence suggests these are much more material, particularly in the short to medium term, than the risk of unburnable carbon or the carbon bubble (Caldecott et al. Citation2017). For example, air pollution and water scarcity in China threatens coal-fired power generation, which has changed coal demand and affected global coal prices (Caldecott, Tilbury, and Ma Citation2013); the shale gas revolution in the United States has put downward pressure on coal prices in Europe, stranding new high-efficiency gas plants (Caldecott and McDaniels Citation2014); and the fossil fuel divestment campaign threatens to erode the social licence of some targeted companies and could increase their cost of capital (Ansar, Caldecott, and Tibury Citation2013).

1st Global Conference on Stranded Assets and the Environment

Despite its growing prominence as a topic, there remains a great deal of confusion about: what stranded assets are; what assets might be affected; what drives stranding; how financial institutions and companies can manage the risk of stranded assets; what it means for policy-makers and regulators; and how it links to climate change policy. The academic literature on stranded assets also remains relatively limited. Researchers, scholars, and practitioners have generally opted for the publication of working papers, research notes, speeches, government white papers, and reports to disseminate their work as quickly as possible so they can influence a fast-moving discourse.

To critically review and help formulate a better understanding of stranded assets, and to help foster the development of the academic literature on the topic, the Sustainable Finance Programme at the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment organised the 1st Global Conference on Stranded Assets and the Environment on the 24th and 25th September 2015 at The Queen’s College, Oxford. The conference brought together over 120 leading scholars and practitioners from a range of disciplines, including economics, finance, geography, management, and public policy. The conference was sponsored by Norges Bank Investment Management and the full agenda and list of speakers at the conference can be found in the appendix at the end of this editorial.

Conference papers were considered for inclusion in this Special Issue of the Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. The Special Issue contains 8 of the 25 papers presented at the conference and these were selected through a multiple stage short-listing process based on an editorial assessment of quality and novelty, followed by double-blind peer review. Details of the eight papers included are as follows.

The first paper in the Special Issue, Game theory and corporate governance: conditions for effective stewardship of companies exposed to climate change risks, examines how investors can successfully convince listed fossil fuel companies to avoid asset stranding through the lens of game theory. The paper tests the effectiveness of owner engagement strategies by studying the conditions for cooperation between investors and their companies. Several parameters are modelled for their impact on the development of sustained cooperative equilibria, including: the benefits and costs of cooperation; the degree of strategic foresight; individual discount factors; and mutual history.

The second paper, Assessing the sources of stranded asset risk: a proposed framework, proposes a more efficient framework for assessing where stranded assets might arise, particularly from a bond investor perspective. The author proposes that what are currently called ESG risks are separated into three specific risk categories: (1) Operational or Management Risk; (2) Climate Risk, primarily related to climate mitigation and adaptation; and (3) Natural Capital Risks, a category intended to capture natural capital depletion, subsidy loss risks, and certain geopolitical risks. Stranded assets can arise from all three sources, but those arising from Climate and Natural Capital Risk are more likely to be both significant and irreversible.

The third paper, Investment consequences of the Paris climate agreement, develops a model of an energy transition. Projections for growth in renewables and electric vehicles suggest that the oil and gas industry will be disrupted during the 2020s, but that carbon dioxide emissions are unlikely to fall fast enough to keep within a 2° emissions budget. To keep warming to 2°, additional ways of reducing emissions from industry or of accelerating emissions reductions from generation, transport, and buildings will be needed together with an extensive programme of carbon dioxide removal.

The fourth paper, A comparative analysis of the anti-Apartheid and fossil fuel divestment campaigns, attempts a comparison of the similarities and differences between the extant fossil fuel divestment movement and the anti-Apartheid divestment movement. Fossil fuel divestment campaigners and advocates have deployed stranded assets arguments to make the case for divestment and this is the largest and fastest growing divestment movement in history.

The fifth paper, Transition risks and market failure: a theoretical discourse on why financial models and economic agents may misprice risk related to the transition to a low-carbon economy, links the traditional market failure literature and the recent research around potential stranded assets risks. The market failure literature provides theoretical evidence of a potential mispricing of stranded asset risks due to the design and interpretation of financial risk models, and the practices and institutions linked to economic agents. Policy intervention will likely be needed to address the design of financial risk models and associated transparency around their results, and the actual institutions governing risk management.

The sixth paper, Blindness to risk: why institutional investors ignore the risk of stranded assets, considers if the structure of the investment chain causes investors to be blind to stranded assets. The paper draws on a mixture of academic literature and the author’s own experience of industry practice. The paper finds that institutional investors are constrained to measure risk in relation to a benchmark; risk becomes a function of volatility and divergence from peers. The risk of stranded assets is invisible in the decision-making chain. The industry is further constrained by its culture, regulation, and inappropriate incentives.

The seventh paper, Social and Asocial learning about climate change among institutional investors: lessons for stranded assets, contributes new empirical data from 58 in-depth interviews and a global investor survey to explore how climate change is being learnt socially and asocially within the institutional investment industry. This research seeks to identify ways in which the concept of stranded assets can be better disseminated to investment professionals. This paper should interest both investment professionals keen to learn more about the issue and academic researchers seeking to engage investors on these topics.

The final paper, Climate change and the fiduciary duties of pension fund trustees – lessons from the Australian law, examines the obligations of pension (or ‘superannuation’) fund trustee directors in Australia. The analysis focuses on the obligation to apply due care, skill, and diligence under section 52A of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth) (SIS Act). It concludes that a passive or inactive governance of climate change portfolio risks is unlikely to satisfy their duties: whether the inactivity emanates from climate change denial, honest ignorance, or unreflective assumption, strategic paralysis due to impact uncertainty, or a default to a base set by regulators or investor peers. Considered decisions to prevail with ‘investment as usual’ may also fail to satisfy the duty if they are based on outdated methodologies and assumptions.

Together these eight papers make a significant contribution to furthering the literature on stranded assets. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the authors’ extensive collective experience of finance and investment, there is a strong bias towards research that can directly or indirectly support financial institutions understand and manage the risk of stranded assets. This is welcome, because if stranded assets are effectively priced and integrated into financial decision-making, capital is less likely to flow to assets that are incompatible with environmental sustainability and more like to flow to those that are. This is a necessary, albeit insufficient condition, to address climate change and the other environmental challenges facing humanity. The role of finance in this regard, particularly in a world where the politics and policy of dealing with global of environmental appears to be getting harder, has never been more important.

Notes

1 Defined as the future emissions expected from all existing fossil fuel-burning infrastructure worldwide (Davis, Caldeira, and Matthews Citation2010).

2 These were conducted by the author and took place in March–April 2016 at Stanford University.

References

- Allen, M. R., V. R. Barros, J. Broome, W. Cramer, and R. Christ. 2014. “IPCC Fifth Assessment Synthesis Report-Climate Change 2014 Synthesis Report.” http://www.citeulike.org/group/15400/article/13416115.

- Ansar, A., B. Caldecott, and J. Tibury. 2013. “Stranded Assets and the Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaign: What Does Divestment Mean for the Valuation of Fossil Fuel Assets?” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford, (October).

- Bagwell, P., and P. Lyth. 2002. “Transport in Britain: From Canal Lock to Gridlock.” Accessed August 15, 2016. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=1JdCtWuaQhcC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=railway+networks+replaced+canals+and+waterways+england&ots=W-YkMrbBVF&sig=ywv87TQiCFWx1P4D5UqYsqBYe2M.

- Bank of England. 2015a. “One Bank Research Agenda.” http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/research/Documents/onebank/discussion.pdf.

- Bank of England. 2015b. “The Impact of Climate Change on the UK Insurance Sector A Climate Change Adaptation Report by the Prudential Regulation Authority.” http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/pra/Documents/supervision/activities/pradefra0915.pdf.

- Broadberry, S., and B. Gupta. 2005. Cotton Textiles and the Great Divergence: Lancashire, India and Shifting Competitive Advantage 1600–1850. pp. 23–25. Accessed August 15, 2016. http://www.iisg.nl/hpw/factormarkets.php.

- Caldecott, B. 2011. Why High Carbon Investment could be the Next Sub-prime Crisis. The Guardian.

- Caldecott, B. 2012. Review of UK Exposure to High Carbon Investments.

- Caldecott, B. 2015. Stranded Assets and Multilateral Development Banks. Inter-American Development Bank.

- Caldecott, B., G. Dericks, A. Pfeiffer, and P. Astudillo. 2017. “Stranded Assets: The Transiton to a Low Carbon Economy.” Lloyd’s of London Emerging Risk Report.

- Caldecott, B., N. Howarth, and P. McSharry. 2013. “Stranded Assets in Agriculture: Protecting Value from Environment-Related Risks.” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford. http://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/research-programmes/stranded-assets/StrandedAssetsAgricultureReportFinal.pdf.

- Caldecott, B., and J. McDaniels. 2014. “Stranded Generation Assets: Implications for European Capacity Mechanisms, Energy Markets and Climate Policy.” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford. http://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/research-programmes/stranded-assets/StrandedGenerationAssets-WorkingPaper–FinalVersion.pdf.

- Caldecott, B., J. Tilbury, and Y. Ma. 2013. “Stranded Down Under? Environment-related Factors Changing China’s Demand for Coal and What this Means for Australian Coal Assets.” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford. Accessed December 2, 2015. http://www.smithschool.ox.ac.uk/research-programmes/stranded-assets/StrandedDownUnderReport.pdf.

- Carbon Tracker Initiative. 2011. “Unburnable Carbon – Are the World’s Financial Markets Carrying a Carbon Bubble?” http://www.carbontracker.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Unburnable-Carbon-Full-rev2-1.pdf.

- Carbon Tracker Initiative. 2015. “Lost in Transition: How the Energy Sector Is Missing Potential Demand Destruction.” http://www.carbontracker.org/report/lost_in_transition/.

- Carbon Tracker Initiative. n.d. “Carbon Tracker Initiative’s Definition of Stranded Assets.” Accessed August 23, 2016. http://www.carbontracker.org/resources/.

- Carbon Tracker Initiative. 2013. Unburnable Carbon 2013: Wasted Capital and Stranded Assets. London: Carbon Tracker Initiative.

- Carney, M. 2015. “ Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – Climate Change and Financial Stability.” Speech given at Lloyd’s of London by the Governor of … .

- Congressional Budget Office. 1998. “Electric Utilities: Deregulation and Stranded Costs.” CBO Paper.

- Davis, S. J., K. Caldeira, and H. D. Matthews. 2010. “Future CO2 Emissions and Climate Change from Existing Energy Infrastructure.” Science 329 (5997): 1330–1333. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/doi/10.1126/science.1188566. doi: 10.1126/science.1188566

- Davis, S. J., and R. H. Socolow. 2014. “Commitment Accounting of CO2 Emissions.” Environmental Research Letters 9 (8): 1. http://stacks.iop.org/1748-9326/9/i=8/a=084018?key=crossref.b7c8701dfa5d89a68f45f1956e8793b9. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/9/8/084018

- Deloitte. 2016. “IAS 16 — Property, Plant and Equipment.” http://www.iasplus.com/en/standards/ias/ias16.

- EAC. 2014. Green Finance E. A. Committee, ed. http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201314/cmselect/cmenvaud/191/191.pdf.

- Exxon Mobil Corporation. 2014. Letter on to Shareholders and NGOs Carbon Asset Risk. http://cdn.exxonmobil.com/∼/media/global/files/other/2014/cover-letter-to-arjuna-capital.pdf.

- Figueres, Christiana. 2013. Keynote Address by Christiana Figures, Executive Secretary UNFCCC at the World Coal Association International Coal & Climate Summit. http://www.unep.org/newscentre/Default.aspx?DocumentID=2754&ArticleID=9703.

- Financial Stability Board. 2015. FSB to Establish Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/Climate-change-task-force-press-release.pdf.

- Friedman, T. L. 2014. Obama on Obama on Climate. The New York Times. Accessed June 7, 2014. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/08/opinion/sunday/friedman-obama-on-obama-on-climate.html?smid=tw-TomFriedman&seid=auto&_r=2.

- Generation Foundation. 2013. Stranded Carbon Assets. p.26. http://genfound.org/media/pdf-generation-foundation-stranded-carbon-assets-v1.pdf.

- Grübler, A., and N. Nakićenović. 1991. “Long Waves, Technology Diffusion, and Substitution.” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 14 (2): 313–343. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40241184.

- Gurría, A. 2013. “The Climate Challenge: Achieving Zero Emissions – Lecture by OECD Secretary-General.” http://www.oecd.org/about/secretary-general/the-climate-challenge-achieving-zero-emissions.htm.

- Hedegaard, C. 2015. “Divestment and Stranded Assets in the Low-carbon Transition – Chair’s Summary.” OECD’s 32nd Roundtable on Sustainable Development, 28th October 2015.

- IEA. 2008. World Energy Outlook 2008. Paris: International Energy Agency.

- IEA. 2013. “Redrawing The Energy Climate Map.” World Energy Outlook Special Report, p.134. http://www.worldenergyoutlook.org/media/weowebsite/2013/energyclimatemap/RedrawingEnergyClimateMap.pdf.

- IPCC. 1999. Economic Impact of Mitigation Measures: Proceedings of IPCC Expert Meeting on Economic Impact of Mitigation Measures: The Hague, the Netherlands, 27–28 May, 1999, CPB.

- IPCC. 2001. IPCC Third Assessment Report – Climate Change 2001. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- King, S. M. 2012. Reply to Your Recent Letter on UK Exposure to High Carbon Investments C. C. Capital, ed.

- Kondratiev, N. 1926. The Long Waves in Economic Life. Eastford, CT, USA: Martino.

- Krause, F., W. Bach, and J. Koomey. 1989. Energy Policy in the Greenhouse. El Cerrito, CA: Dutch Ministry of the Environment.

- Kruitwagen, L., D. MacDonald-Korth, and B. Caldecott. 2016. “Summary of Proceedings: Environment-related Risks and the Future of Prudential Regulation and Financial Conduct – 4th Stranded Assets Forum, Waddesdon Manor, 23rd October 2015.” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford.

- Lamb, C. 2015. “Drying and Drowning Assets – How Worsening Water Security Is Stranding Assets.” http://www.strandedassets2015.org/agenda.html; http://www.strandedassets2015.org/uploads/2/6/9/5/26954337/session_v_presenter_ii_catelamb.pdf.

- London School of Economics. 2013. “$674 Billion Annual Spend On ‘Unburnable’ Fossil Fuel Assets Signals Failure to Recognise Huge Financial Risks – Press Release.” http://www.lse.ac.uk/GranthamInstitute/news/674-billion-annual-spend-on-unburnable-fossil-fuel-assets-signals-failure-to-recognise-huge-financial-risks-2/.

- McGrath, P. 2014. “Ban Ki-moon Urges Pension Funds to Dump Fossil Fuel Investments.” ABC.

- McKibben, B. 2011. “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.” Rolling Stone.

- Morel, A., R. Friedman, D. Tulloch, and B. Caldecott. 2016. “Stranded Assets in Palm Oil Production: A Case Study of Indonesia about the Sustainable Finance Programme.” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford.

- Mufson, S. 2014. “CEO of Royal Dutch Shell: Climate Change Discussion ‘has gone into la-la land’.” https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/09/10/ceo-of-royal-dutch-shell-climate-change-discussion-has-gone-into-la-la-land/.

- Perez, C. 1985. “Microelectronics, Long Waves and World Structural Change: New Perspectives for Developing Countries.” World Development 13 (3): 441–463. Accessed August 15, 2016. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0305750X85901408. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(85)90140-8

- Perez, C. 2002. “Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital.” Edward Elgar. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Technological-Revolutions-Financial-Capital-Dynamics/dp/1843763311.

- Perez, C. 2010. “Technological Revolutions and Techno-economic Paradigms.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (1): 185–202. http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/content/34/1/185.abstract. doi: 10.1093/cje/bep051

- Pfeiffer, A., R. Millar, C. Hepburn, and E. Beinhocker. 2016. “The ‘2°C Capital Stock’ for Electricity Generation: Committed Cumulative Carbon Emissions from the Electricity Generation Sector and the Transition to a Green Economy.” Applied Energy 179 (1): 1395–1408.

- Rautner, M., S. Tomlinson, and A. Hoare. 2016. “Managing the Risk of Stranded Assets in Agriculture and Forestry.” Chatham House Research Paper.

- Rook, D., and B. Caldecott. 2015. “Cognitive Biases and Stranded Assets: Detecting Psychological Vulnerabilities Within International Oil Companies.” Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford.

- Royal Dutch Shell plc. 2014. “Letter to Shareholders – Stranded Assets.” Accessed May 16, 2014. http://s02.static-shell.com/content/dam/shell-new/local/corporate/corporate/downloads/pdf/investor/presentations/2014/sri-web-response-climate-change-may14.pdf.

- Schumpeter, J.A. 1942. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Routledge. Accessed August 14, 2016. http://aulavirtual.tecnologicocomfenalcovirtual.edu.co/aulavirtual/pluginfile.php/520365/mod_resource/content/1/TEORIASDELEMPRENDIMIENTO.pdf.

- Weyzig, F., B. Kuepper, J.W. van Gelder, R. van Tilburg, J.W. van Gelder, and R. van Tilbury. 2014. “The Price of Doing Too Little Too Late The Impact of the Carbon Bubble on the EU financial system.” In Green New Deal Series. Brussels: Green European Foundation.

- Wolf, W. 1996. “Car Mania: A Critical History of Transport.” Accessed August 15, 2016. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=DD0samQuijgC&oi=fnd&pg=PR1&dq=rise+of+the+automobile+and+the+end+of+the+steam+railway+&ots=DmO5Le-Z7W&sig=WuYG9kiWjsWptp6C9-toB1shc40.

- The World Bank. 2013a. “Toward a Sustainable Energy Future for All: Directions for the World Bank Group’s Energy Sector.”

- The World Bank. 2013b. “World Bank Group Sets Direction for Energy Sector Investments.” Accessed July 16, 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/07/16/world-bank-group-direction-for-energy-sector.

Appendix. Conference Agenda

Thursday, 24th September 2015

11:00–11:05 Welcome and Opening Remarks

Professor Gordon L. Clark, Director, Smith School, University of Oxford

11:05–11:20 Introduction to Stranded Assets and the Conference

Ben Caldecott, Founder & Director, Stranded Assets Programme, Smith School, University of Oxford

11:20–11:35 Keynote: Petter Johnsen, Chief Investment Officer, Norges Bank Investment Management

11:35–13:05 Session I: CLIMATE CHANGE AND CARBON ASSET RISK

Chair: Professor Paul Ekins, Director, UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources

Papers:

• ‘Committed cumulative carbon emissions and the 2°C capital stock’ by Alexander Pfeiffer, Richard Millar, Cameron Hepburn, and Eric Beinhocker (University of Oxford)

• ‘The Value at Risk from Climate Change’ by Howard Covington (University of Cambridge)

• ‘Carbon Asset Risk: from rhetoric to action’ by Mark Fulton (Energy Transition Advisors), James Leaton (Carbon Tracker Initiative), and Shanna Cleveland (Ceres)

13:05–14:30 Lunch

Hall at The Queen’s College, Oxford

Keynote: Professor Robert Socolow, Professor Emeritus of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Princeton University, and Co-Director of the Carbon Mitigation Initiative at the Princeton Environmental Institute

14:30–16:30 Session II: HOW INVESTORS PERCEIVE STRANDED ASSETS

Chair: James Hulse, Head of Investor Initiatives, CDP

Papers:

• ‘Blindness to risk: why institutional investors ignore the risk of Stranded Assets’ by Nicholas Silver (London School of Economics and Callund Consulting)

• ‘Communicating Stranded Assets throughout the investment value chain’ by Elizabeth Harnett (University of Oxford)

• ‘Could behavioural biases be contributing to the underestimation of climate change policy and renewable technology on investments in fossil fuels?’ by Katie Stafford (London School of Economics)

• ‘Are carbon risks mispriced? Insights from the market failure literature’ by Jakob Thomae, Hugues Chenet, and Didier Janci (2° Investing Initiative)

16:30–17:00 Coffee Break

17:00–18:30 Session III: STRANDED ASSETS AND COAL

Chair: Simon Upton, Director, Environment Directorate, OECD

Papers:

• ‘Ecological limits, technology, and coal’ by John Byrd and Elizabeth Cooperman (University of Colorado)

• ‘Carbon constraints casting a shadow over the coal industry’ by Michael Wilkins (Standard & Poor’s)

• ‘Understanding Stranded Assets in South Africa: a quantitative and qualitative analysis of risks to 2050′ by Jesse Burton, Tara Caetano, Bruno Merven, Fadiel Ahjum, Alison Hughes, Adrian Stone, Mamahloko Senatla, and Bryce McCall (Energy Research Centre, University of Cape Town)

18:30–19:30 Drinks Reception

The Fellows’ Garden at The Queen’s College, Oxford

19:30–22:00 Dinner

Hall at The Queen’s College, Oxford

Keynote: Nick Butler, author of The Financial Times Energy and Power blog and Visiting Professor and Chair of the Kings Policy Institute at King’s College London

Friday, 25th September 2015

09:00–11:00 Session IV: MACROECONOMY IMPLICATIONS

Chair: Isabel Hilton, CEO, China Dialogue

Papers:

• ‘The economic implications of the transition to a low-carbon energy system: a stock-flow consistent model’ by Emanuele Campiglio (London School of Economics), Antoine Godin (Kingston University), and Stephen Kinsella (University of Limerick)

• ‘Lock-in, and stranding, of fossil fuel supply infrastructure’ by Peter Erickson, Michael Lazarus, and Kevin Tempest (Stockholm Environment Institute)

• ‘The fossil fuel bailout: G20 subsidies to oil, gas and coal exploration‘ by Shelagh Whitley, Elizabeth Bast, Shakuntala Makhijani, and Sam Pickard (Overseas Development Institute)

• ‘Beyond carbon pricing: the role of banking and monetary policy in financing the transition to a low-carbon economy’ by Emanuele Campiglio (London School of Economics)

11:00–11:30 Coffee Break

11:30–13:00 Session V: STRANDED ASSETS IN OTHER SECTORS

Chair: Michael Lazarus, US Center Director, Stockholm Environment Institute

Papers:

• ‘Stranded Assets in shipping’ by Tristan Smith (UCL Energy Institute), Thomas Bracewell (Hartland Shipping), and Rebecca Mulley (Lloyd’s Register)

• ‘Drying and drowning assets - how worsening water security is stranding assets now’ by Cate Lamb, Esben Madsen, and James Hulse (CDP)

• ‘Negative Emissions Technologies and Stranded Carbon Assets’ by Ben Caldecott (University of Oxford), Mark Workman (Imperial College London), and Guy Lomax (Imperial College London)

13:00–14:30 Lunch

Hall at The Queen’s College, Oxford

Keynote: Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger, founders of the Breakthrough Institute and executive editors of Breakthrough Journal

14:30–16:00 Session VI: INTEGRATING STRANDED ASSETS AND SHIFTING INVESTOR BEHAVIOUR

Chair: Professor Gordon L. Clark, Director, Smith School, University of Oxford

Papers:

• ‘Assessing the sources of Stranded Asset risk: a proposed framework’ by Bob Buhr (Société Générale)

• ‘Insights in implementing Climate Risk reduction in a pension fund portfolio’ by Faith Ward and Mark Mansley (Environment Agency Pension Fund)

• ‘Climate Change and Fiduciary Duty: the old shield becomes a potent sword’ by Sarah Barker (Minter Ellison Lawyers and University of Melbourne) and Mark Baker-Jones (Dibbs Barker and Queensland University of Technology)

16:00–16:30 Coffee Break

16:30–18:00 Session VII: FORCEFUL STEWARDSHIP

Chair: Howard Covington, Chair, Alan Turing Institute and former Chief Executive, New Star Asset Management

Papers:

• ‘Fiduciary capitalism, systemic risk and forceful stewardship’ by Raj Thamotheram (University of Oxford and Preventable Surprises)

• ‘A comparative analysis of the Apartheid and fossil fuel divestment campaigns’ by Olaf Weber, Chelsie Hunt, and Truzaar Dordi (University of Waterloo, Canada)

• ‘Game theory modelling of conditions for effective stewardship’ by Lucas Kruitwagen (Imperial College London)

18:00–18:05 Closing Remarks

18:05–19:30 Drinks Reception

Hosted by: Sir Martin Smith, Founding Benefactor, Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, University of Oxford

The Fellows’ Garden at The Queen’s College, Oxford