ABSTRACT

At this stage of Asia's development there is a need, and an opportunity, to establish a validation methodology that better gauges ESG implementation and sustainability aspirations in Asian private equity. Private equity, like major public market and debt investors such as Blackrock, has adopted language that suggests a proactive approach to ESG management. However, process-oriented ESG compliance presently far outstrips evidence of tangible contributions to ESG objectives and outcomes. This article describes a taxonomy of common approaches to ESG investment practices in Asian private equity and discusses their shortcomings. It then presents ‘Deep ESG’ as an alternative approach that operationalizes ESG and sustainability metrics more holistically than existing frameworks. The Deep ESG framework enables a higher level of market-led intentionality that better informs institutional investors, regulators, communities, and employees as they evaluate private equity's ‘balance sheet’ of ESG outcomes. By investing in tools for goal setting, measurement and evaluation and applying them consistently across all target and portfolio companies, private equity managers can pivot away from a defensive approach by working with stakeholders to shape constructive solutions to urgent sustainability goals.

1. Introduction

The report of the Global Commission on Adaptation on climate change highlights the urgent challenges arising from crop reductions, rising seas, insufficient water supply, and the resulting poverty that will engulf hundreds of millions of people (GCA Citation2012). Climate change could emerge as the next global crisis; in South Asia alone it is expected to force nearly 40 million people to migrate within their countries by 2050 (Rigaud et al. Citation2018). South Asia, East Asia and the Pacific already account for 42% of persons globally living below the World Bank defined poverty line, and without a change in direction that percentage is likely to increase (World Bank Citation2018b).

Asia's contribution to these global issues over the next decade cannot be ignored. Asia's economies already account for 40% of world activity and in the next 12 years will nearly double in size (Nakao Citation2019). Almost 75% of the world's coal fired power plants that are either under construction or in the planning stages are in Asia (New York Times, November 24, 2018). Large amounts of non-renewable power capacity come on line annually – 725 GW since 2010 (IREA Citation2019) – and renewables represent only 22% of electricity generation (BP Citation2019). Asian urban transport infrastructure is still in development or transition (Arcadis Citation2017). The region is the site of half of the world's largest mining operations (Consultancy Asia Citation2019). Deforestation remains problematic,Footnote1as does the generation of plastic waste (World Bank Citation2018a). The sequelae of Asia's US$100 billion internet economy (Google, Temasek and Bain Citation2019), while sometimes considered low impact from an ecological perspective, is responsible for significant increases in transportation, packaging, waste, and their related emissions. Asia's compelling consumer opportunities – fast food, large mall developments, luxury products, short lifecycle electronics, high performance vehicles – often fall short of environmental, social and governance (‘ESG’) standards and fail to consider the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (‘SDGs’).

This context presents a pressing need for a more profound linkage of ESG investment to sustainabilityFootnote2 objectives. Traditional patterns of emerging markets investment activity are resulting in significant funding going to businesses that are prima facie unsustainable, poorly structured to take advantage of new technologies promoting resource efficiency, and under-designed in terms of worker and community welfare. In the context of highly competitive emerging markets, many of Asia's business founders and financial sponsors are in a hurry for growth and are correspondingly less motivated to consider long-term sustainability. For instance, it has been identified that listed Chinese companies have limited awareness of ESG concepts and the importance played by sustainability to their business operations (Mio and Lu Citation2019). Many senior executives in Hong Kong-listed companies have indicated that the focus on short-term returns over long-term, sustainable growth has hindered consideration of ESG issues within their companies (KMPG China Citation2018). Over relatively short time horizons, such businesses experience few negative consequences. Limited domestic regulations and weak enforcement (Zhao Citation2019) suggest that ESG is typically not a significant consideration in business development and evaluation.

In the following sections, the role of private equity (‘PE’) in guiding Asia's ESG development is considered.Footnote3 The demands of global investors and the evolving efforts of Asian PE managers in the face of local realities have led to common approaches to ESG that are classified into a taxonomy of ‘Compliant’, ‘Selective’ and ‘Illustrative’ ESG. These categories reflect a scaling from lowest ESG commitment levels and lowest ESG impacts to progressively higher levels of commitment and impact. Each of these practices is subject to important limitations on their true ESG value.

The article subsequently proposes Deep ESG as a holistic, methodological framework for PE investment – highest in terms of both commitment and ESG impact. The Deep ESG framework is informed and was developed primarily as a result of: (1) one co-author's experiences implementing ESG systems for a sustainability-focused Asian private equity fund over a 10 year period; and (2) the authors identifying the challenges in applying principles of sustainability to private equity investments in a context where there are few agreed upon metrics or standards for evaluating the sustainability potential of a PE investment, analogous to a lack of accounting standards for a certified financial report.

Although Deep ESG may be applied broadly to PE practices, Asian PE firms seeking to engage ESG and sustainability objectives present unique challenges, and thus deserve special focus. First, Asia's economies represent nearly half of the global economy and provide a majority of global growth so there is substantial room for proactive ESG actions in the context of abundant new investment activities. Second, relative to Western markets, where governments and investors have compelled rigorous reporting and accountability for environmental and social outcomes, Asian governments promote relatively lenient regulatory and enforcement standards for environmental performance, carbon emissions, and social welfare norms for employees. Many PE firms operating in Asia are of course well aware of the initiatives taken in more developed markets, such as the technical screening criteria being developed as part of creating a European taxonomy designed to assist investors and companies to improve their environmental performance. However, the lower hurdle in Asia places an unusual burden on PE firms in that they must drive entrepreneurs towards global ESG and sustainability norms when these norms likely far exceed applicable local standards and expectations.

The key objective of the Deep ESG framework is that it should have utility to PE practitioners who, irrespective of whether they have a specific ESG focus, understand the importance of progressing their strategies beyond checklist ESG programs towards a holistic evaluation of the sustainability impact of investments including on a portfolio basis. The five key elements of the Deep ESG framework reflect the key components of common PE strategies: (1) deal sourcing and early evaluation, (2) due diligence, (3) development of operational plans and governance frameworks, (4) long-term strategic plan formulation, and (5) evaluation and continuous improvement that eventually concludes with exit from the investment.

Academic research focusing on ESG frameworks for investment firms has largely aimed to drive standards and comparability within the mutual fund and public investment firm community. These efforts draw upon readily accessible ESG data for these firms and their publicly-listed portfolio companies.

With regard to private equity, ESG data for private firms and their private portfolio companies (many of which are small or medium sized ventures) is not accessible except to insiders; thus private equity's ESG record has received less attention from academics. This is especially true for PE firms operating in emerging markets such as Asia where reporting requirements, local standards, and frameworks put forward by industry associations are generally less demanding and weaker in terms of accountability.

Deep ESG repositions ESG investment from a defensive strategy to an active engage-and-implement plan of action on a clearer vector toward sustainability outcomes rather than process-oriented checklists. In a Deep ESG framework, (1) the PE firm establishes the ESG bases and SDG outcomes by which it seeks to consistently assess all investments, (2) it externally communicates these policies, and validated outcomes on a regular basis, and (3) the rigor of the framework regarding transparency, objectivity and independence enables stakeholders to confidently assign ESG and SDG merit not only to individual and portfolios of investments, but also to the PE firm as a whole. As such, Deep ESG demonstrates a higher level of intentionality to institutional investors, regulators and communities with a focus on sustainable investment or sustainability impacts. Deep ESG has the potential to drive capital allocation in a more ambitious and commercially compelling direction to solve urgent sustainability goals.

While comparability among firms’ programs is a valuable objective, the undeveloped state of private equity ESG practices in Asian markets suggests a period of experimentation. Deep ESG is therefore not prescriptive, as it allows PE firms to determine how and where to best address the questions and challenges presented by the Deep ESG framework. The experiences that result from Deep ESG implementation will constructively inform, and promote a transition to, standards developed by governments and investors that are more aligned with industry best practices. Defined ESG standards would eventually allow comparability across PE firms, and this could successfully co-exist with the non-prescriptive Deep ESG framework. It is hoped that the adoption of Deep ESG will lead to a significant advancement of current ESG models employed by Asian PE firms, and serve as a meaningful pathway towards addressing the SDGs.

2. Asian private equity's measured approach to ESG

PE in Asia has recently come to be viewed as a truly successful and well-established asset class in which investors provide early stage growth capital and buyout funding to serve the growth of Asia's economies (Yang, Akhtar, and Dessard Citation2019). Up until the early 2000s, much of the investment record in Asian PE lagged other parts of the world, largely due to the inexperience of PE firms and their inability to take control of and add value to portfolio companies. Commitments to Asian PE have expanded dramatically as vintages post-2010 produced attractive returns comparable to established markets – the top quartile of funds from 2010 produced annualized returns between 19% and 25%, in line with investor objectives (Yang, Akhtar, and Dessard Citation2019). Asia Pacific's share of the global PE market in terms of assets under management has grown from 9% in 2009 ($137 billion) to 26% in 2019 ($883 billion), a roughly 6x growth over the past decade (Yang, Akhtar, and Dessard Citation2019).

Many Asian PE firms are pursuing high growth consumption sectors where little consideration is given to the business model in terms of (1) its ecological impact (‘Footprint’), or (2) its societal impact, such as community and worker issues, human rights and access to basic needs (‘Utility’). Business sectors that typically produce negative Footprint or low Utility outcomes include oil and gas development, traditional construction materials such as cement (Mahasenan, Smith, and Humphreys Citation2003), single-use plastic packaging (Sustainability Times, May 21, 2019), electronic products with short lifecycles,Footnote4 convenience-oriented home delivery services (BBC, March 29, 2019), entertainment products including gaming (Mills et al. Citation2019) and gambling sites, and various predatory lending entities aimed at low income borrowers. The potential for explosive growth over a five year horizon – an important timeframe for PE firms – may commercially outweigh the difficulty of assessing Footprint and Utility consequences that only become visible over longer periods.

Yet substantive research often neglects PE's potential influence in contributing to the SDGs in emerging markets such as Asia. This persists despite the growing influence of PE firms in most sectors of the world economy,Footnote5 their ability to control management decision making at the portfolio company level, and their typically long fund investment lives of 10–12 years. Academic research has focused on the activities of large corporate entities, publicly listed companies, and public fund managers. While there is support for a positive correlation between ESG practices and financial performance (Friede, Busch, and Bassen Citation2015; Mishra Citation2020) or the cost of equity for firms (Gregory, Stead, and Stead Citation2020), other research condemns the notion that socially responsible investing consistently produces advantaged financial results (Porter, Serafeim, and Kramer Citation2019) or identifies problems in the accuracy, quality and consistency of ESG ratings (Doyle Citation2018). The notable polarization of views remains nascent in the context of PE where studies’ access to data is limited and anecdotal (for example, see Zeisberger Citation2014). Reflecting this lacuna, between the potential impact of PE and the measurement of project and market outcomes, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) initiated its Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring (AIMM) system in 2017 to study and report on private sector solutions (IFC Citation2019).

Asian PE investors may experience three main hurdles in holistically addressing ESG issues, relative to their international counterparts. First, many Asian PE deals involve minority ownership,Footnote6 under which operational changes can be limited. More recent vintages of Asian PE funds have begun to prioritize ‘control transactions’ (Yang, Akhtar, and Dessard Citation2019). Second, enforcement of environmental and workplace regulations in Asia remains underdeveloped relative to mature markets. Third, a key marketing premise for ESG investments – that they provide shareholders a premium valuation upon public listing or exit – appears to hold less weight within Asian markets where investors prioritize ‘hyper growth’.

The coming 10-year cycle of Asian PE investment represents an opportunity to proactively undertake ESG-positive investments that impose an enduring shape on Asia's regulatory infrastructure. Companies investing ahead of the design and implementation of ESG regulations have an opportunity to shape regulations toward commercially efficient solutions and areas of competitive differentiation (Porter and van der Linde Citation1995). However, the current state of Asian PE firms’ ESG practices falls well short of this aspiration.

2.1. A structural paradox at this stage of development

PE investors in Asia are caught between two conflicting paradigms. International institutional and high net worth investors increasingly want Asian investment products to dramatically expand ESG elements, often referencing the SDGs (The Impactivate, November 8, 2018).Footnote7 They expect PE managers to provide a commitment to ESG practices and information transparency to facilitate ESG evaluation. One leading pension fund states that each of its investments should contribute to SDGs and support the generation of positive social and/or environmental impact through products and services, or acknowledged transformational leadership.Footnote8 The clear directive is that funds that fail to respond to these demands will lose support from at least a segment of institutional investors.

In contrast, Asian companies, regulators and public markets do not typically hold similar expectations. While regulations are becoming more stringent in countries such as China (PRI Citation2018)Footnote9 and India,Footnote10 enforcement is inconsistent. The evidence for better long-term financial performance through strong ESG practices is often less compelling than providing a seller with competitive pricing and terms; in fact, PE firms’ ability to differentiate through knowledge and commitment to ESG practices may be perceived as a negative because of the implied additional short-term costs (Horváthová Citation2012).Footnote11 Thus, the ESG drivers especially for small and medium sized companies in Asia are not powerful.

The field of ESG research and practice is presently littered with an array of tags, phrases and systems seeking to provide PE investors with tools to commence a dialogue with stakeholders about environmental and societal concerns (Novick et al. Citation2020). However, the foregoing conflict of paradigms has led many PE firms to adopt defensive devices for responding to ESG demands. These appear to acknowledge ESG concerns and assert ESG policies but are loose enough not to place the firm at a competitive disadvantage when seeking deals they believe will produce strong returns over five year cycles typical for individual PE investments.Footnote12 Defensive approaches to ESG can still lead firms to egregious mistakes in their quest to demonstrate ESG responsibility. So-called ‘greenwashing’ is common: actual results may fall short of claims or negative data ignored.

The United Nations’ Principles for Responsible Investment (‘UN PRI’) has since its inception in 2006 been seen as a standard for asset managers wishing to express a commitment to responsible investing. As at February 2020, over 2,250 asset owners, managers and service providers have signed on to the six principles which guide PRI membership. However, free-riding and greenwashing effects for less committed firms are problematic (Gray Citation2009; Bauckloh et al. Citation2019) and in 2018 the PRI established a ‘Serious Violations’ policy to protect against outliers. In February 2020 it announced a ‘mandatory to report but voluntary disclosure’ requirement for certain climate-related risk indicators (PRI Citation2019). Continuing issues include the lack of specificity about requirements, reporting that is limited primarily to climate issues over social and governance items, and a continuing reliance on self-reporting over independent verification. Interestingly, PE is not the only financial product struggling to establish credentials in ESG and sustainability performance; green bonds are also receiving similar scrutiny (Flammer, Citation2021).

Most companies that choose to report environmental and social data do so selectively. According to the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (‘CDSB’) (Citation2020),Footnote13 reporting by Europe's 50 largest companies ‘fails to offer investors a clear understanding of companies’ development, performance, position and impact, as it lacks the necessary quality, comparability and coherence’. It may be noted that regulators have not to date applied significant pressure on ESG issues, although the European Union is actively engaging on green and sustainable financing initiatives.Footnote14 In Asia, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited has recently introduced mandatory disclosure requirements requiring a board statement on its consideration of ESG issues.Footnote15 The requirements of stock exchanges signal to private companies societal expectations for leading industry executives and their private investors when they seek a public listing (Johnstone and Goo Citation2017; Johnstone and Long Citation2019).Footnote16 However, exchanges in Mainland China and Southeast Asia typically lack effective ESG reporting policies and enforcement mechanisms.

2.2. A taxonomy of current practices

The foregoing structural issues have led ESG practices in Asian PE to evolve along one of three methodological paths, each of which have limited positive impact on ESG objectives.

2.2.1. Compliant ESG

A firm establishes ESG ‘checklists’ intended to identify and support companies that are seeking to avoid severely damaging activities and/or put in place processes (e.g. ESG policy, board supervision) providing comfort to investors that some form of ESG factor is present. This practice, often minimal and prevention-focused, can at best achieve only isolated outcomes, and at worst may support willful blindness. Generally, checklist approaches should not per se be considered ‘greenwashing’, although compliant ESG approaches would be open to fair criticism where it is claimed that such basic measures fulfill broader sustainability objectives.

2.2.2. Selective ESG

Larger firms may establish within a sub-fund an ESG-centric practice, and utilize that fund for investments in the portion of their deals where there is a case for ESG neutral or positive practices in the investee company. However, firms typically don't apply this ESG approach across the full range of their investment activities, rendering the firm's overall ESG investment profile balanced in a possibly negative direction. For example, a project might showcase a new sustainability model and give the impression that a problem is being solved, when the majority weighting of the firm's capital allocation continues in unsustainable directions. Global funds establishing sidecars for impact face the risk they will be assessed on the consistency of their policies across all investment platforms (Market Watch, November 25, 2019; CRR Citation2018; PERP Citation2018). PE firms that choose to highlight their advanced ESG practices within sub-funds, while failing to explain their actions within their main investment vehicles, may be rightfully criticized that they are window dressing their broader ESG impact.

2.2.3. Illustrative ESG

Smaller firms may establish impact funds where ESG gains higher prominence in the assessment of deal opportunities. The scale of investment, business operations, and thus ESG impact is typically small. As most impact oriented PE managers are newly formed entities with limited track records, they generally receive a limited supply of capital from institutional investors.Footnote17 While this approach has marginal impact on ESG practices in the broader economy, their demonstration of advanced ESG practices is praiseworthy. ImpactBase counts hundreds of PE/VC funds focused on impact investing.Footnote18

When looked at in isolation, the results from Compliant, Selective and Illustrative ESG programs may be directionally positive. When looked at holistically, a significantly different picture may emerge that represents a highly diluted form of what responsible global investors expect ESG initiatives to achieve. It is often a question of form over substance where process takes priority over hard metrics, resulting in an impression that something is being done when the opposite may in fact be the case. As such, there is no ‘holistic accounting’.

2.3. Attendant issues

Other than the structural issues discussed earlier, two factors that support defensive, process-oriented practices in Asia and other emerging economies are (1) the lack of accepted methodologies for evaluating investment prospects and (2) the lack of objective measurement standards post-investment.

2.3.1. Lack of accepted methodologies

Evaluating whether a business model is suitable to be regarded as a prospect for ESG investment is problematic because it presents issues at the first stage of proactive ESG investment. A variety of definitions and approaches can be taken as to what qualifies as ‘green’. Investment tags such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, sustainable transportation, water quality and conservation and green building are sometimes described as ‘unassailable’ in terms of their ‘green-ness’ – but to the extent they lack granularity as to the actual outcomes the concept of ‘unassailability’ invites misleading or counterproductive outcomes. For meaningful common frameworks to develop, an approach is to cross-over different forms of finance and different stages of a business's development without losing perspective on the real ESG issues at stake. It should shed light on problems such as:

can a firm invest in a damaging industry, based on commitments to implement ESG improvement processes;

how should a firm weight unsustainable results from an investment versus its positive contributions;

when should an investment that fails to achieve its ESG targets be re-labelled as unsustainable?

Using an example from the building materials sector, cement companies have long been a compelling investment target. Yet cement production represents 8% of global carbon emissions, according to think tank Chatham House as quoted in a BBC article on December 17, 2018. Within Asia, India's cement industry generates 670 kg of CO2 per tonne of cement produced, including onsite power generation (WBCSD Citation2018). Recent improvements in emissions, waste utilization and product quality have been achieved largely by waste heat recovery systems and blended cement using silica fumes and fly ash materials. Do these improvements in Footprint validate an ESG-driven cement investment? Should PE firms prioritize companies developing alternatives to cement – easier to reuse, lighter, or made from recycled or organic materials – to incorporate sustainability goals?

2.3.2. Lack of objective measurement standards post-investment

Clearer perspectives on the true output of any ESG implementation are needed to provide better quality information. Unlike financial accounting, where there is usually a quantitative answer to a question raised by investors, ESG currently depends too heavily on an array of qualitative metrics that are subject to wide interpretation and manipulation. While certain phenomena can be relatively accurately measured – such as carbon emissions – what this means in the context of an overall sustainability plan can be subject to qualitative interpretation. For example, the number of jobs created is a measurable output but the substantive question is whether, and if so how, it contributes to an ESG or SDG objective.

The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board has created a ‘Materiality Map’ to help companies think about categories to evaluate and measure. The Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures is working with regulators and stock exchanges to establish a standard framework for investors to compare carbon emissions among companies. While Norges Bank, among others, has argued against outcome-based ESG measurement (as noted in Environmental Finance, May 3, 2019), the idea of a ‘scoring system’ for companies to measure SDG outputs is gaining credence (IR Magazine, June 3, 2019).

The shortcomings of ESG investment approaches reviewed above indicate a need for a methodology that better operationalizes ESG metrics in the context of Asian PE. There needs to be a clearer dividing line between (1) investments having qualified and limited ESG impact while still harmful when measured more holistically or over the longer term, and (2) investments evidencing benefits that significantly outweigh any negative Footprint they generate. Global investors have two options: develop a scoring system they impose on PE managers, or allow managers to develop their own tools and support managers in assessment and modification. The latter alternative undoubtedly promotes better integration into market practices. Where practitioner-developed tools are transparent to stakeholders there is an opportunity for minimum market standards for ESG practices to emerge. It is suggested that the adoption of Deep ESG will facilitate this opportunity.

3. Deep ESG

PE investment is typically premised on identifying enterprises that have a strong business model and are growing at a rate exceeding industry norms. One might therefore ask at what stage should ESG considerations be factored in and how should they be weighted. However, this is the wrong question to ask because answers may lapse into Compliant ESG or support an opt-in approach that can give rise to partial and potentially misleading ESG perspectives, as seen in Selective or Illustrative ESG.

Instead, it is proposed that ESG metrics must be comprehensively integrated with core commercial practices and applied over multiple investment life cycles of a PE firm's investments, from pre-investment screening to ongoing implementation and assessment. This requires a deeper partnership between commercial practices and ESG, as opposed to ESG being an adjunct process. Such an approach highlights whether a PE manager's investments in toto are contributing in a meaningful way to ESG objectives. This should encapsulate the broader portfolio and manager actions of PE firms, not just isolated investments.

In response to these considerations, Deep ESG is proposed as a holistic methodological framework that better operationalizes ESG metrics across a PE firm's investment portfolio. It is comprised of five factors, which reflect the key components of PE investment activities and are explained below:

Disclosure of the parameters of a Deep ESG framework brings depth and breadth to ESG assessment. It enables third parties to assign their own confidence level to the ESG merit of the investment and promotes the opportunity for more open and informed dialogue because it implicitly recognizes the many different shapes an ESG investment might take on. Part of the problem in current mainstream ESG investment activity is the (often unilateral) application of binary labels that inhibit more informed discourse by glossing over the more subtle considerations as to whether overarching ESG objectives are truly being met. Deep ESG avoids this problem because it promotes a clear statement of the bases on which an investment is regarded by the manager as meeting ESG objectives.

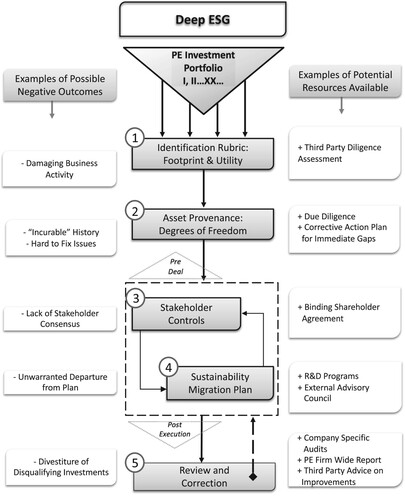

Each of the five factors described below are comprised of two parts. The first, ‘Required Statement’, briefly sets out what the PE firm must state as the basis on which it has applied or will be applying the relevant factor. The second, ‘Commentary’, provides added color to the intent of the Required Statement, and a manager may elect to provide further detail in like terms. shows how the five factors interact.

Figure 1. Deep ESG's five factors operate across the life cycle of a PE firm's investments in toto. Factors (1) & (2) can be applied equally across an investment portfolio as a set of house standards. Factors (3) & (4) are specific to the circumstances of each investment. While variation from one investment to another of factors (3) & (4) would be normal and expected, variation of factors (1) & (2) across investments would weaken a Deep ESG framework. Factor (5) is consequential on the quality of factors (1) & (2), and how well factors (3) & (4) have anticipated business developments and relevant externalities. The examples given at the left and right sides don't impact on a Deep ESG framework per se, but will affect the robustness of an ESG program.

3.1. Identification rubric: footprint and utility

3.1.1. Required statement

What form of review has been undertaken at the front end of the PE firm's investment process to (1) reduce or eliminate exposure to businesses that are likely to have a material negative impact on ESG and sustainability metrics, (2) identify investment prospects for contributing to ESG, and (3) determine whether this review has been applied differently from other investments in a similar asset class. As this factor is capable of being equally applied by an individual PE firm across a number of investments, variation from one investment to the other would be a negative unless adequately justified.

3.1.2. Commentary

Is the business one that provides an essential or valued product in a manner that is efficient? For businesses that are assessed as unsustainable or neutral, managers must articulate their purpose in making the investment, with a reference to ESG metrics where possible.

Numerous industries fall into disqualifying territory: oil and gas, non-renewable resources, and businesses that rely upon substandard worker conditions for production. There are various shades in interpreting whether a business provides Utility. For example, the assessment of food products might focus on whether the end products enhance the well-being of consumers or cause potentially significant health damage, or it might focus on the interactions of the product source with proper land use, efficient and natural pesticides, water use, and worker relationships involving grower communities. These front-end processes will impact on how investments decisions are made. Some research indicates that where basic ESG factors have not been integrated into valuation models cum investment decisions, purported ESG investments do not lead to meaningful ESG outcomes. This may support greenwashing (Schramade Citation2016). Getting the right orientation from the outset is central to the Deep ESG framework.

3.2. Asset provenance: degrees of freedom

3.2.1. Required statement

What steps have been taken to assess provenance of the business and its assets and determine if baseline issues can be meaningfully and appropriately improved, i.e. what degrees of freedom exist with regard to correction of provenance concerns. In respect of a specific investment, has the review of provenance been applied differently from other investments in a similar asset class. As this factor is capable of being equally applied across a number of investments, variation from one investment to the other would be a negative unless adequately justified.

3.2.2. Commentary

This is a distinct item from the identification rubric because it requires a specific focus on the origins of separate elements of an ongoing business. In Asia, many businesses that may be operating on relatively well established grounds, i.e. responsibly, may nevertheless be exposed to issues that cannot easily be ‘cured’. Where such issues are identified they should be addressed in the sustainability migration plan (discussed below).

For example, waste management businesses across Asia have often been allotted licenses through non-public tender processes. In assessing these businesses, investors must determine if such allotment is likely to create future liabilities or claims, possibly on an extraterritorial basis, since best practices require transparent public tenders. The waste management site can pose significant problems, such as when adjacent land is designated for residential or agricultural purposes or when the site is located within traditional community or national park boundaries, any of which may lead to legal or regulatory issues. Soil contamination created in prior years may be difficult to assess and new investors will bear responsibility for remediation. In such cases, the degrees of freedom may be highly limited, even though the business's function may be seen to provide positive benefits.

3.3. Stakeholder controls

3.3.1. Required statement

What arrangements are in place to secure the mutual commitment of founders, management and other stakeholders to ESG leadership and formation of a sustainability plan (discussed below). The statement should provide detail explaining the sufficiency of controls and accountability, the extent to which the same is embedded in the shareholders’ agreement and indicate what human resources and capital are intended to be deployed. Unlike the previous factors, variation of this factor (and those that follow below) across different investments would be normal and expected.

3.3.2. Commentary

The sufficiency of commitment and controls is particularly difficult for Asian PE players because it may mean putting themselves at a disadvantage in competitive deal environments. The statement should therefore provide some indication of the investment dynamics that have led to the incumbent control structure and assess the prospects for this evolving in tandem with the implementation of the sustainability migration plan.

Two examples, one from Europe and one from Asia, demonstrate what stakeholder controls can look like. Unilever has sustainability accountability at both the corporate and business unit level. Unilever defines 177 sustainability topics and puts them into priority categories (Unilever Citation2020). It formed an eight person independent Sustainable Sourcing Advisory Board comprised of NGO experts and impact investors. In Asia, China Light & Power (Hong Kong) (CLP) provides electricity to 80% of Hong Kong's population. CLP's board annually announces targets for decarbonization of its power infrastructure and diversification of its workforce. In December 2019, it announced a ‘Climate Vision’ under which it committed not to invest further in coal-fired capacity and to phase out all coal assets by 2050. It is investing heavily in IT for smart energy and for cyber resilience and data protection. And its task force will use scenario analysis to upgrade these plans every five years. Recent research supports the proposition that longer term strategic models of governance that promote stewardship within a company correlate positively with better ESG performance by the company (Chevrollier et al. Citation2020).

3.4. Sustainability migration plan

3.4.1. Required statement

What is the overall ESG intent of the investment over its life cycle and how will it be accomplished. This should be documented in a sustainability migration plan (‘SMP’), which should (i1 set out the relevant factors according to the nature of the business, (2) envision the steps that can be taken as soon as practicable to evaluate the most suitable modules for implementation and estimate what may be possible in the medium term, (3) encompass granular expectations in relation to the operations of a business and/or more aspirational-based standards that go beyond local market norms, and (4) identify the ESG-sensitive metrics by which the success of the plan can be assessed.

3.4.2. Commentary

The SMP is both formative and reflective of investment intent, and sets the prospect for ESG success from the outset. It should be formed as part of an implementation methodology, be designed in view of stakeholder controls, and be capable of facilitating objective review and correction. Firms should establish SMPs in a more consistent, holistic and ambitious way as part and parcel of pre-investment assessments. This requires a stringent pre-investment assessment of performance metrics and relevant baselines for an operating company prior to investment. In practice it may be difficult or impossible to come up with an SMP post-investment if the fundamentals are not present. Once formed, there should be regular and systematic reviews in order to upgrade and update the SMP. Use of an independent advisory council should be considered, as should access to leading technologies and practices.

Possible scenarios for transitioning business practices should be explored at the outset of the investment, including likely areas of regulatory development as well as potential for gaining competitive advantage. Questions that might be asked include: how the business will provide a valuable societal function in the longer term; how the product can be re-designed in ways that significantly lessen the impact on natural systems and resource utilization; how proper re-use and disposal plans might be achieved; how the employment system will be evolved to address diversity and offer community benefits; and how to incorporate representation and decision making at all stakeholder levels to take into consideration the SMP.

For example, The Bank of England (BoE) requires financial institutions to evaluate the impact of climate scenarios on their portfolios (Bank of England Citation2019). Two scenarios envision near term adjustments required to limit temperature increases to 2° Celsius. A third involves assessing impacts and actions over the period to 2050. Banks began preparing for full implementation by late 2020; however, the onset of COVID-19 compelled BoE to postpone implementation plans. In the meantime, banks like Barclay's are facing public shareholder pressure to unwind lending to carbon intensive energy projects.Footnote19

Corporate examples follow. BMW has rethought its entire product and production process. The result is a vehicle which can be disassembled in one hour, where parts are reconditioned for use in aftermarkets and 95% of materials are recovered and re-used (BMW Citation2014, Citation2017). Patagonia developed the ‘Don't Buy This Jacket’ campaign to encourage people to only buy products they truly need.Footnote20 Patagonia products maintain a lifetime warranty, wherein customers return products experiencing significant wear for repair.Footnote21 SK Group, a Korean conglomerate focused on semiconductors, energy, and telecommunications has made sustainability a pillar of its activities; it is a technical advisor to China's SASAC government entity to establish China's national ESG standards.Footnote22 These examples illustrate paths that Asian PE firms may pursue with their mid-sized private Asian companies (which have tended to prioritize expansion over ESG commitments; Financial Times, May 11, 2020).

3.5. Review and correction

3.5.1. Required statement

What methodology will be used to assess the implementation of the SMP, how often will it be engaged, and how will the results be used to provide feedback on and evolve the SMP. The methodology should indicate how the review and reporting system will be undertaken, e.g. by the company or PE investor self-reporting or by an independent service provider. The review should assess whether stakeholder controls have inhibited or facilitated implementation of the SMP.

3.5.2. Commentary

Company self-reporting is the current model of ESG implementation across Asia. This can raise questions about the quality and integrity of performance metrics provided. Accordingly, where independent reporting is not to be used, this should be accompanied by an explanation as to why. Where independent parties evaluate the implementation of the SMP, it should be indicated whether they will be engaged to, for example, make recommendations for improvements, benchmark the original grade with the grade achieved over time, or utilize automated systems designed to capture and report relevant data on a real-time basis.

Assessment of the interaction between the SMP and stakeholder controls is important as this may indicate whether proposed changes to the SMP are likely to be effective. Where they are proven to be significantly ineffective, consideration may need to be given to divestiture or, alternatively, justification for maintaining the investment.

4. The opportunity and the risk

Scientists and global policy makers view Asia as a critical battleground for ESG and SDG priorities (UNESCAP Citation2019).Footnote23 Asian PE needs a more ambitious path to impart a positive influence on these important issues. While the SDGs are useful tools for policy makers, many of them are difficult for private business to address directly. It remains a point of contention that certain SDGs may collide with profit motives (Agarwal, Gneiting, and Mhlanga Citation2017). Yet the SDGs presently offer the best reference point to begin conversations on how to achieve more sustainable and just economies and societies.

Given the complexity of and prognosis for Asia's ESG problems, it is virtually certain that governments will increase the scale and scope of regulations. This is likely to address the use of non-renewable materials, the pace of developing renewable energy, raising air and water emissions standards, restrictions on international transport of waste, and costing of negative externalities such as carbon emissions. Stringent regulations are already on the books, even though compliance may be insufficient to ensure such regulations are met (Wincuinas Citation2019). One current example is China's approaching soil quality and restoration rules that could exceed even the most stringent standards in Europe or the United States (Farmer and Mahoney Citation2019).

While multinationals are expected to lead Asian ESG initiatives due to global mandates, Asian PE investors working together with locally led businesses have an opportunity to develop competitive advantages by more clearly establishing ESG and sustainability performance. Capital investment that does not go beyond minimal and defensive strategies fails to respond to the changing commercial context. Evidence from outside Asia supports the proposition that Deep ESG can enable positive differentiation, including by establishing the initial ESG valuation proposition, integrating it into investment decisions, and promoting better ESG stakeholder governance. However, more quantitative, longitudinal research needs to be undertaken in the specific context of Asian PE, which may provide different insights from research undertaken in the public context or in political economies not representative of those found in Asia. It would be of considerable interest if underlying themes could be established common to these different contexts.

The driving principle of Deep ESG is to operationalize ESG and sustainability metrics by engaging management commitment to the SMP, moving assessment to an outcomes focused approach, establishing higher aspirations across an entire investment portfolio and enabling the holistic evaluation of performance. Taken together, this enhances the ability of market forces to determine whether capital is being allocated to managers who take ESG and sustainability seriously. Managers will need to ask hard questions to ensure that the entire investment team considers ESG an integral part of the investment process, not simply an afterthought. As such, it promotes a more informed context for the evaluation, implementation and review of investments being held out with ESG or sustainability labeling. Deep ESG is admittedly demanding. Few PE firms may fully achieve it. Hence it is aspirational and represents a direction of travel for PE firms wanting to improve their approach to ESG and sustainability. Where that happens, it will facilitate PE investors seeking competitive advantage via differentiated ESG performance, and it will promote the reappraisal of investment horizons in anticipation of regulatory and market changes. Taken together, this will enable Asian PE as an industry to begin to get sustainability practices right, and to facilitate Asia's contribution to solving global challenges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Indonesia, Malaysia and India are experiencing conversion of forests into agricultural land and plantation. These forests hold our greatest inventory of biological diversity and serve as the storehouse for hundreds of gigatons of carbon. See WWF website, https://wwf.panda.org/our_work/forests/

2 As used herein, sustainability generally refers to sustainable development as being a ‘process of change in which the exploitation of resources, the direction of investments, the orientation of technological development, and institutional change are made consistent with future as well as present needs’. World Commission on Environment and Development, ‘Our Common Future’, (Citation1987) para 30.

3 In a practical sense, the frameworks presented could apply to most of the world's emerging market private equity activity. Since the authors are based in Hong Kong, one an Asian PE sustainability fund manager and the other an expert on regulation and governance practices in Asia, attention is focused on Asia's private equity activities.

4 A shorter lifespan equates to greater environmental costs. See Greenpeace Reports, Guide to Greener Electronics (Citation2017), page 14.

5 Ernst & Young estimates that already 5% of US GDP is overseen and controlled by private equity firms. October 2019. ‘Economic Contribution of the US Private Equity Sector in 2018’.

6 That has been the trend in China. See Kwek (Citation2012).

7 According to their studies, 86% of HNW investors expect companies to ‘make a positive contribution to society’.

8 See https://www.apg.nl/en/asset-management/responsible-investing. APG is a leading Dutch pension fund with 482 billion Euro in assets under management.

9 In 2016, the China Securities Regulatory Commission announced that listed companies will be subject to more stringent ESG disclosure requirements: see http://www.csrc.gov.cn/pub/newsite/zjhxwfb/xwdd/201607/t20160701_300109.html.

10 In 2012, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) made business responsibility disclosure compulsory for the 100, later expanded to 500 in 2015, largest listed companies. See SEBI's circular in 2012: https://www.sebi.gov.in/sebi_data/attachdocs/1344915990072.pdf; also SEBI's regulations in 2015: https://www.sebi.gov.in/legal/regulations/feb-2017/sebi-listing-obligations-and-disclosure-requirements-regulations-2015-last-amended-on-february-15-2017-_37269.html#lir11

11 Environmental practices hinder companies’ short-term financial performances, as shown empirically.

12 Cappucci (Citation2018) has noted that most firms ‘pay heed to sustainable investment principles while demonstrating a less than plenary commitment to ESG practices’, the cause of which (among others) is a lack of standardized ESG performance evaluation.

13 The CDSB is a consortium of business and environmental NGOs established to improve environment-related reporting to the levels of financial reporting.

14 The European Parliament on 28 March 2019 adopted the ‘Establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment’ currently pending Parliament's 2nd reading (2018/0178(COD)), which has been followed by the ‘Report on EU green bond standard’ in June 2019 and the ‘Taxonomy: Final report of the technical expert group on sustainable finance’ in March 2020; China is adopting the NDRC Green Industry Guiding Catalogue and the PBC Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue.

15 Effective for financial years commencing on or after July 1, 2020. See generally HKEX (Citation2019).

16 See in particular Johnstone and Goo (Citation2017) at Recommendation C4.7.1.

17 As per 2013, only 38% of Impact Investment Funds have 3+ years of track record. See World Economic Forum (Citation2013). Impact fund managers are viewed inferior to traditional fund managers in terms of investment track record. See JP Morgan & GIIN (Citation2014).

18 As per 2016, there are in total 403 funds available on ImpactBase. See https://www.impactbase.org/sites/default/files/giin_impactbase_400_funds.pdf.

19 See Mooney and Crow (Financial Times, January 8, Citation2020). In May 2020 shareholders voted to approve Barclays’ commitment to tackling climate change.

22 Bloomberg, ‘China Recruits a South Korean Conglomerate to Advise on ESG’. October 19, 2020.

23 The Asia Pacific region is likely to miss all of its SDGs by 2030. See UNESCAP (Citation2019).

References

- Agarwal, Namit, Uwe Gneiting, and Ruth Mhlanga. 2017. “Raising the Bar: Rethinking the Role of Business in the Sustainable Development Goals.” Oxfam Discussion Papers.

- Arcadis. 2017. Sustainable Cities Mobility Index 2017.

- Bank of England. 2019. The 2021 Biennial Exploratory Scenario on the Financial Risks from Climate Change.

- Bauckloh, Tobias, Sebastian Utz, Sebastian Zeile, and Bernhard Zwergel. 2019. “UN PRI Signatories’ Ethics: Walk the Talk or Talk the Talk? Serious Ethical First Movers vs. Late Free Riders.” SSRN Electronic Journal. Accessed 5 August 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3386095.

- BMW. 2014. Sustainable Value Report 2014.

- BMW. 2017. Sustainable Value Report 2017.

- BP. 2019. BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019.

- Cappucci, Michael. 2018. “The ESG Integration Paradox.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 30 (2): 22–28. doi:10.1111/jacf.12296.

- Chevrollier, Nicolas, Jianhong Zhang, Thijs van Leeuwen, and André Nijhof. 2020. “The Predictive Value of Strategic Orientation for ESG Performance Over Time.” Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society 20 (1): 123–142. doi:10.1108/CG-03-2019-0105.

- Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB). 2020. Falling Short? Why Environmental and Climate-Related Disclosures under the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive Must Improve.

- Consultancy Asia. 2019. “Greater Asia Home to Half of the World’s Largest Mining Companies.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.consultancy.asia/news/2426/greater-asia-home-to-half-of-the-worlds-biggest-mining-companies.

- CRR (Chain Reaction Research). 2018. Private Equity Investment in Consumer Goods Industry Could Jeopardize Zero-Deforestation Effort.

- Doyle, Timothy M. 2018. “Ratings That Don’t Rate – The Subjective View of ESG Rating Agencies.” Technical Report, American Council for Capital Formation. https://bit.ly/2LBwvky.

- Farmer, Alexandra N., and Michael J. Mahoney. 2019. “China’s New Soil Pollution Prevention Law Creates Obligations and Liabilities for Companies with Industrial Sites in China.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.kirkland.com/publications/kirkland-alert/2019/01/china-new-soil-pollution-preventionlaw#:~:text=Overview%20of%20the%20Soil%20Pollution,use%20rights%20holders%20in%20China.

- Flammer, Caroline. 2021. “Corporate Green Bonds.” Journal of Financial Economics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.01.010.

- Friede, Gunnar, Timo Busch, and Alexander Bassen. 2015. “ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More Than 2000 Empirical Studies.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 5 (4): 210–233.

- GCA (Global Commission on Adaptation). 2012. Adapt Now: A Global Call for Leadership on Climate Resilience.

- Google, Temasek, and Bain & Company. 2019. e-Conomy SEA 2019.

- Gray, Taylor. 2009. “Investing for the Environment? The Limits of the UN Principles of Responsible Investment.” SSRN Electronic Journal. Accessed 5 August 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1416123.

- Greenpeace Reports. 2017. Guide to Greener Electronics.

- Gregory, Richard P., Jean Garner Stead, and Edward Stead. 2020. “The Global Pricing of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Criteria.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. doi:10.1080/20430795.2020.1731786.

- HKEX. 2019. “Exchange Publishes ESG Guide Consultation Conclusions and Its ESG Disclosure Review Findings.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.hkex.com.hk/news/regulatory-announcements/2019/191218news?sc_lang=en.

- Horváthová, Eva. 2012. “The Impact of Environmental Performance on Firm Performance: Short-Term Costs and Long-Term Benefits?” Ecological Economics 84: 91–97. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.10.001.

- IFC (International Finance Corporation). 2019. “AIMM Sector Framework Brief.” https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/Topics_Ext_Content/IFC_External_Corporate_Site/Development+Impact/Areas+of+Work/sa_AIMM/.

- IREA (International Renewable Energy Agency). 2019. Renewable Capacity Highlights.

- Johnstone, Syren, and Say Goo. 2017. Report on Improving Corporate Governance in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Institute of Certified Public Accountants. https://bit.ly/2KhYN3B

- Johnstone, Syren, and Frederick Long. 2019. “Alibaba, HKEX & ESG: Missed Leadership Opportunities.” International Financial Law Review. https://www.iflr.com/article/b1lmxc9rbjn57k/alibaba-hkex-amp-esg-missed-leadership-opportunities

- JP Morgan & GIIN. 2014. Spotlight on the Market—the Impact Investor Survey.

- KPMG China. 2018. ESG: A View from the Top—the KPMA, CLP and HKICS Survey on Environmental, Social and Government (ESG).

- Kwek, P. Y. 2012. Private Equity in China: Challenges and Opportunities. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Mahasenan, Natesan, Steve Smith, and Kenneth Humphreys. 2003. “The Cement Industry and Global Climate Change: Current and Potential Future Cement Industry CO2 Emissions.” Proceedings of the 6th International Concerence on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies 3: 995–1000. doi:10.1016/B978-008044276-1/50157-4.

- Mills, Evan, Norman Bourassa, Leo Rainer, Jimmy Mai, Arman Shehabi, and Nathaniel Mills. 2019. “Toward Greener Gaming: Estimating National Energy Use and Energy Efficiency Potential.” The Computer Games Journal 8: 157–178. doi:10.1007/s40869-019-00084-2.

- Mio, Victoria, and Jie Lu. 2019. Overcoming the Challenges of ESG Integration in Chinese A-Shares.

- Mishra, Subodh. 2020. Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2020/01/14/esg-matters/.

- Mooney, Attracta, and David Crow. 2020. “Barclays Pressed to Stop Financing some Fossil Fuel Groups.” Financial Times, January 8. Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/0160cb3a-3167-11ea-9703-eea0cae3f0de.

- Nakao, Takehiko. 2019. Moving Together as One Wave for the Future of Asia and the Pacific. 3 May, Asian Development Bank speech.

- Novick, Barbara, Brian Deese, Tom Clark, Carey Evans, Allison Lessne, Meaghan Muldoon, and Winnie Pun. 2020. Towards a Common Language for Sustainable Investing. January, Blackrock Whitepaper.

- Porter, Michael E., George Serafeim, and Mark Kramer. 2019. “Where ESG Fails.” Institutional Investor. 16 October.

- Porter, Michael E., and Claas van der Linde. 1995/09. “Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate.” Harvard Business Review.

- PRI (Principles for Responsible Investment). 2019. “TCFD-Based Reporting to Become Mandatory for PRI Signatories in 2020.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.unpri.org/news-and-press/tcfd-based-reporting-to-become-mandatory-for-pri-signatories-in-2020/4116.article.

- PRI (Principles of Responsible Investment). 2018. Investor Duties and ESG Integration in China.

- Private Equity Stakeholder Project. 2018. “TPG Capital and Blackstone Affiliates at Center of Puerto Rico Foreclosure Crisis.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://pestakeholder.org/tpg-capital-and-blackstone-affiliates-at-center-of-puerto-rico-foreclosure-crisis/.

- Rigaud, Kanta Kumari, Alex de Sherbinin, Bryan Jones, Jonas Bergmann, Viviane Clement, Kayly Ober, Jacob Schewe, et al. 2018. Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Schramade, Willem. 2016. “Integrating ESG into Valuation Models and Investment Decisions: The Value-Driver Adjustment Approach.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 6 (2): 95–111.

- UNESCAP. 2019. Asia and the Pacific SDG Progress Report 2019.

- Unilever. 2020. “Materiality Matrix 2017/2018.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.unilever.com/Images/materiality-matrix-2017-18_tcm244-537797_en.pdf.

- WBCSD (World Business Council for Sustainable Development). 2018. “India Cement Industry on Track to Meet 2030 Carbon Emissions Intensity-Reduction Initiatives.” Accessed 5 August 2020. https://www.wbcsd.org/Sector-Projects/Cement-Sustainability-Initiative/News/Indian-cement-industry-on-track-to-meet-2030-carbon-emissions-intensity-reduction-objectives.

- Wincuinas, Jason. 2019. Sustainable and Actionable: A Study of Asset-Owner Priorities for ESG Investing in Asia. 17 June, Economist Intelligence Unit.

- World Bank. 2018a. “Planet over Plastic: Addressing East Asia’s Growing Environmental Crisis.” Accessed 2 September 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/06/08/planet-over-plastic-addressing-east-asias-growing-environmental-crisis#:~:text=The%20Singapore%20Hub%20for%20Infrastructure,to%20choose%20Planet%20over%20Plastic.

- World Bank. 2018b. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Our Common Future.

- World Economic Forum, and Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu. 2013. From Margins to Mainstream: Assessment of the Impact Investment Sector and Opportunities to Engage Mainstream Investors.

- Yang, K., Usman Akhtar, and Johanne Dessard. 2019. Asia Pacific Private Equity Report 2019. Bain & Company.

- Zeisberger, Claudia. 2014. ESG in Private Equity: A Fast-Evolving Standard. INSEAD.

- Zhao, Jinhua. 2019. Environmental Regulation: Lessons for Developing Economies in Asia. ADBI Working Paper Series No. 980.