ABSTRACT

Investors recently adopted a novel approach to sustainable investing: engaging with countries to advance sustainable development. But engaging with sovereign entities on sustainability challenges, like the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is complex. To guide sovereign debt investors in operationalizing this new sustainable investing strategy, this methodology and policy paper creates a framework that navigates the sovereign engagement process. The framework answers three questions: (i) who to engage with; (ii) what to engage on; and (iii) how to engage. First, countries are prioritized based on the investor's investment exposure and the country's progress on the SDGs. Second, using public data, SDGs and sub-targets are identified that face slow progress, thus being priorities to engage on. Third, a detailed roadmap is provided that offers a systematic approach to engaging with the identified country on selected SDG(s). This sovereign SDG Engagement Framework aims to help investors and countries achieve their shared sustainability objectives.

1. Introduction

In July 2020, a group of 34 investors started a policy dialogue with the government of Brazil in an effort to halt the country's escalating rate of deforestation and to protect the rights of indigenous peoples. Six months later, the membership of this Investor Policy Dialogue on Deforestation (IPDD) grew to reach 45 financial institutions, with approximately $7 trillion in assets under management (AuM).Footnote1 The Brazilian government responded supportively to the IPDD's request for a dialogue. During the dialogue, Brazil's Vice President has expressed its commitment to combatting illegal deforestation and to ending the ongoing military-led operations in the Amazon.Footnote2 Although it is too soon to tell whether the IPDD will be successful, it is a clear example of a new phenomenon: investor-led engagement with countries on sustainability challenges.

Engaging with investees on sustainability challenges is one of two broad sustainable investing approaches. Sustainable investing, which we liberally define as the simultaneous integration of financial and sustainability dimensions into the investment process in order to coincidentally pursue financial and societal objectives, can broadly be operationalized through capital allocation and via active ownership. The former approach, capital allocation, intends to shift capital towards sustainable assets and away from those that are unsustainable. The latter, active ownership, sees investors use their ownership of an asset to influence the sustainability performance of the investee, for instance through voting at shareholder meetings or through engagement. These approaches are complementary, and the efficiency with which they might support societal value is drawing increased interest from researchers (e.g. Atta-Darkua et al. Citation2020; Blitz, Swinkels, and van Zanten Citation2021; Brest, Gilson, and Wolfson Citation2018; Kölbel et al. Citation2020).

Although sustainable investing is rapidly gaining traction in the financial industry,Footnote3 to date the centre of gravity is on private sector investments. Sustainability integration in public sector assets, like sovereign fixed income, received far less attention, both in research and in practice. Extant research has primarily focused on the relationship between the integration of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors into the sovereign bond investment process and financial performance. Because ESG integration helps avoid a broader spectrum of risks than ‘conventional’ risk assessments would unearth, such studies generally find a positive link with performance (e.g. Badía, Pina, and Torres Citation2019; Drut Citation2010; Duyvesteyn, Martens, and Verwijmeren Citation2016). Another strand of research analyzes the emergence of social and green bonds, which are debt instruments whose proceeds are used to advance societal or environmental objectives (e.g. Agliardi and Agliardi Citation2019; Azhgaliyeva, Kapoor, and Liu Citation2020; Baker et al. Citation2018; Banga Citation2019; Chiesa and Barua Citation2019; Flammer Citation2020; Maltais and Nykvist Citation2020). While the sustainable bond market still covers only a small portion of the global bond market, there is strong demand for such products. They offer investors an opportunity to invest in sustainable solutions that meet their clients’ interests at comparable risk levels relative to similar conventional bonds, although there may be a small premium to purchase green bonds (‘greenium’) (see e.g. Swinkels (Citation2021) for a discussion on allocating to green bonds).

However, aside from green and social bond investing, relatively few efforts have been directed towards helping sovereign debt investors actively contribute to advancing particular sustainable development objectives. This is surprising: public assets comprise a significant portion of the assets managed by investors. Supranational and sovereign bonds account for nearly 70 percent (USD 88 trillion) of the global bond market (USD 128 trillion)Footnote4 (ICMA Citation2020). Clearly, identifying how sovereign debt investors can further integrate sustainability into their strategies holds significant potential for improving investors’ societal and environmental impacts.

The objective of progressively integrating sustainability into sovereign debt investment strategies is particularly relevant in the context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In 2015, all 193 United Nations (UN) member states committed to work towards achieving the 17 SDGs and their 169 targets by 2030 (UN Citation2015). Collectively, the SDGs aim to ‘free humanity from poverty, secure a healthy planet for future generations, and build peaceful, inclusive societies as a foundation for ensuring lives of dignity for all’ (UN Citation2017, 4). While it was clear from the start that these are bold goals, assessments unequivocally show that progress is too slow (Sachs et al. Citation2020; UN Citation2020). Nevertheless, and despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the SDGs still are achievable and affordable (Sachs et al. Citation2020). Among others, turning the tide requires a more active involvement of the private sector in general (e.g. van Zanten and van Tulder Citation2018, Citation2020) and of investors more specifically (e.g. Nedopil Wang, Lund Larsen, and Wang Citation2020; Schramade Citation2017; Zhan and Santos-Paulino Citation2021).

We contend that, because they invest in the debt of countries that have committed to the SDGs, sovereign debt investors are particularly in a position to influence countries to advance these goals through engaging with governments. Indeed, the PRI recently proclaimed that given the size of the sovereign bond market, investors carry the fiduciary responsibility to examine how they can better integrate sustainable investing and engage on sustainability topics with sovereigns (PRI Citation2020). But engagement is not a one-way street that only benefits investors. Governments too have ample reasons for collaborating with investors on improving their nation-wide performance on the SDGs. Partnering with investors may give governments access to sustainability expertise and financial capital that could drive sustainable development progress. If governments credibly work on improving sustainable development outcomes, they signal to investors that they have a long-term perspective, leading them to be perceived as more likely to repay their debt in the future (Margaretic and Pouget Citation2018). This indicates that more sustainable countries are less risky to invest in and they are indeed found to have lower financing costs than (more) unsustainable nations (e.g. Capelle-Blancard et al. Citation2019). However, as the PRI (Citation2020) acknowledges, investor engagement with sovereign entities is highly challenging and must be navigated carefully.

In this methodology and policy paper we therefore investigate how investors can effectively engage with sovereign entities on the SDGs. As this is an emerging phenomenon, we take first steps towards identifying how a successful sovereign engagement project might be shaped. More specifically, we introduce a framework that can navigate investors in their sovereign engagement process. This framework helps sovereign debt investors answer three questions: (i) Who to engage with?; (ii) What to engage on?; and (iii) How to engage? Hence, collectively these three questions support investors in navigating the entire sovereign engagement process in a systematic manner.

The framework that we develop has clear practical implications: it is actionable and we explain how investors might put it to practice. Investors can use the framework to engage with the governments of countries it already invests in (existing portfolios). They might also use the framework to identify which countries to invest in, and which governments to engage with, to generate higher sustainability impacts (new investment opportunities). Thus, the framework can be tailored to individual investors’ needs. Theoretically, this paper presents a prescriptive perspective on how sovereign-debt investors might shape sustainable development outcomes at the level of countries through engagement.

The remainder of this paper delineates our approach to creating a sovereign SDG Engagement Framework (Section 2). The framework is introduced in Section 3. We explain the framework’s logic in detail, whereby we give examples using the IPDD’s engagement with the government of Brazil as a case study. Finally, in Section 4 we offer concluding remarks and delineate pathways for future research.

2. Approach to creating a Sovereign SDG Engagement Framework

The aim of this article is to develop a framework that offers investors a systematic approach to navigating engagement with sovereign entities on the SDGs. We adopted the following approach to create this framework.

First, we scheduled interviews with various teams at an asset management firm that is part of the IPDD and participated in the engagement with Brazil on halting deforestation. This included interviews with portfolio managers of the macro (sovereign) investment team and the emerging markets equity team, but also with engagement specialists in the active ownership team, sustainability experts focused on countries’ performance on ESG issues and on the SDGs. In total, we spoke with fifteen investment professionals with diverse areas of expertise. Through these interviews, we identified which questions a framework must be able to answer and the types of data that can be included.

Second, we gained access to, and participated in, investor-led engagements with Brazil and Indonesia, organized under the IPDD umbrella. This allowed us to analyze sovereign engagement processes in practice.

Third, we organized three subsequent group discussion sessions, involving both investment and sustainability experts at this firm, to present, discuss, and subsequently revise the framework that we were developing based on the inputs collected during the interviews and the ideas generated during the investor-led sovereign engagement activities.

3. The Sovereign SDG Engagement Framework

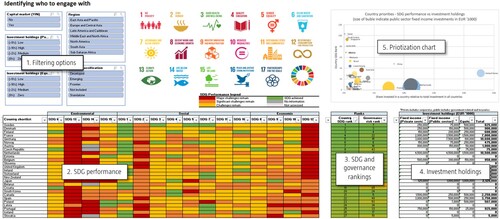

gives an overview of the three-step Sovereign SDG Engagement Framework that was created through this process. In the subsequent sections, we describe how each of the three ‘navigating questions’ in this framework can be operationalized through creating dashboards that combine publicly available statistics with an investor's own data. In describing these sections, we include insights obtained during the interviews. We also use the IPDD's efforts on engaging with Brazil on the topic of deforestation as a case-study. This gives an investor perspective on the decisions that the framework helps to make.

3.1 Who? Identifying countries to engage with

This first part of the framework identifies those countries that are most relevant to engage with. To achieve this, we suggest to prioritize countries based on two criteria: (i) the investor's (current and potential future) holdings of the country's assets; and (ii) the country's performance on the SDGs.

The starting point for prioritizing countries to engage with is to assess the relative and absolute value of an investor's assets across countries. Multiple types of assets fall within the scope of this assessment. First, a pre-requisite for engaging as an investor with sovereign entities is that the investor holds sovereign debt issued by the country. Without holding sovereign debt, it can be challenging for an investor to initiate a dialogue with the country's representatives on SDG performance. Second, including government-related fixed-income investments – such as bonds issued by provincial or municipal organizations – into the assessment is relevant since it can add weight as to why the sustainability performance of a government is important to the investor. Third, corporate fixed income and equity holdings should also be considered. The business environment in which corporates operate is significantly influenced by governmental actions through for example regulatory changes. The outcome of this assessment reveals which countries are the most important to the investor, both in relative and absolute terms. High investments in a particular country provide the investor with an imperative for improving the countries’ sustainability performance – since it can help reduce the risk of its investments and help the investor meet its (clients’) sustainability objectives. In turn, high investments signal to the country that the investor is dedicated to, and invested in, its long-term performance.

Next to assessing investment holdings, countries’ SDG performance must be assessed to identify in which countries the investor can achieve most impact. The SDGs define the world's most urgent sustainability objectives and now are the leading frame of sustainable development (e.g. van Zanten and van Tulder Citation2018). This makes them an ideal blueprint for ranking countries on their sustainable development progress. An interviewee explains how the SDGs provide a shared agenda:

Normally sustainability discussions can be fraught with subjectivity. We find a sustainability topic important, but the party we engage with might disagree. The SDGs make sustainability objective. Countries already adopted them. They find them important so we can align on that.

So, how might investors identify how countries are doing on achieving the SDGs, and which goals are most relevant locally? By adopting the SDGs, countries also committed to report on progress (UN Citation2015). Although there still are vast data gaps (e.g. MacFeely Citation2019), the past years witnessed tremendous progress in surveying countries’ performance on the goals (e.g. van Zanten and van Tulder Citation2020). One of the leading efforts in the SDG Index provided by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (e.g. Sachs et al. Citation2020). This SDG Index annually ranks countries on the SDGs, as well as on the SDGs’ underlying targets, using a mix of official national statistics and informal metrics from non-governmental institutes. This ranking therefore provides an excellent tool for investors to analyze countries’ performance on the goals.Footnote5 Another benefit of using the SDG Index is that the method is audited and that the data is checked for its quality by its creators (e.g. Sachs et al. Citation2020). Sustainability is a field facing significant data challenges. Third party evaluations of performance, using combinations of data sources, is helpful for investors to gain (more) accurate insights into countries’ performance on the SDGs.

Once the data is compiled, it can be proposed that the countries that face bigger challenges in achieving the SDGs should be prioritized for engagement, since these are the countries where most success can be achieved. As a result of the two assessments, countries in which the investor has significant relative and absolute holdings are logical candidates for engagement, whereby those countries facing the most significant challenges should be prioritized.

How can these two criteria be operationalized? We developed a dashboard that allows the investor to view and compare its holdings and SDG performance across countries ().

To explain each of the sections of the dashboard:

Filtering options: allow the user to filter countries according to whether they have sound capital markets (based on inclusion in Bloomberg Barclays Global-Aggregate Index); the extent of public fixed income and/or equity holdings; region; and market classification;

SDG performance: shows how each country is doing on each of the 17 SDGs, using the most recent rankings of the SDG Index (i.e. Sachs et al. Citation2020). In this section, the SDGs are grouped according to whether they drive environmental sustainability, social inclusion, or economic development (cf. Stockholm Resilience Centre Citation2016). This grouping, and the SDG Index's color scheme, help investors quickly grasp what the countries’ most important sustainability challenges are;

SDG and governance rankings: whereas the previous section shows a country's progress on all SDGs, this section first ranks the nation's overall SDG rank (cf. Sachs et al. Citation2020). This gives a rough indication of the country's overall sustainable development status. In addition, a governance risk rank is created using public data on Government Effectiveness from the World Bank. This ranking aggregates factors such as political risks, the quality of policy reform processes and credibility of the government commitment. It helps shed light on how receptive a country might be to an investor's request for dialogue and how credible its participation in an engagement trajectory might be, whereby a higher rank may signal a higher likelihood of a positive response – although it cannot be viewed as an indication of future success;

Investment holdings: this section gives the investor an insight into his/her existing investment holdings in each of the countries. The investment holdings are split into fixed income and equity holdings, although investors could also include their potential exposure in multi-asset strategies;

Prioritization matrix: this matrix is an overlay of a country's SDG rank (y-axis), the share invested in a country relative to the investor's total investment in all countries (x-axis), and the absolute value of public investments in a country (bubble size). The matrix provides an easy way to prioritize countries for engagement on the SDGs: countries with significant bubbles furthest to the top right corner are the countries to prioritize as these are performing poorly on the SDGs with relatively large investment holdings.

We can illustrate the working of this dashboard in the context of IPDD's engagement with Brazil. The country is included in capital markets. In Section 2 of the dashboard, we find that Brazil is ranked 53rd out of 166 countries on its SDG performance (cf. Sachs et al. Citation2020). This signals that although the country is moderately progressing on the SDGs, there is significant progress to be made. In terms of its governance risk ranking (section 3), Brazil is placed 114th out of 203 countries, highlighting the relatively low quality of public services in country and suggesting that investors should pay particular attention to the country's governance during the engagement process. Should the investor using the framework have significant holdings in Brazil (section 4), then the country would show on the top right of the prioritization matrix (section 5).

3.2 What? Defining SDGs to engage on

This second part of the framework selects the SDGs to engage on. Because an investor is unlikely to have the capacity and expertise to engage on all 17 SDGs – whereby a country may perform poorly on achieving most of them – there is a need to prioritize. We suggest to do so by assessing SDGs from both a sustainability perspective and an investment perspective. Inspired by the double materiality perspective introduced by the EU Commission (Citation2019), we define the investment perspective as the impact that failure to meet the SDGs has on a sovereign's ability to meets its repayment obligations in the future, and the sustainability perspective as the impact a sovereign's activities have on achieving the SDGs and ensuring a sustainable, prosperous future.

To consider both perspectives in deciding which SDGs to engage on, we advise to take a cross-organisational approach by forming an internal expert group. The group should include multiple representatives of an organization. This includes: sustainability experts that can advise on the nature of the SDG challenges a country faces and the opportunities to advance them; investment experts that can determine how a country's SDG performance may influence the sovereign issuer's ability to meet future repayment obligations as well the related bond spreads and yields; engagement experts that advice on the actual engagement process; and local offices to ensure that the local perspective and political context is well understood.

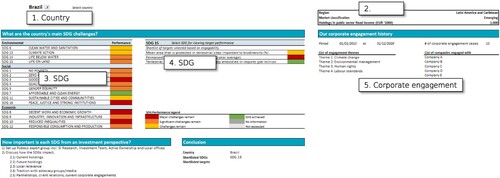

The created expert group can then define which SDG(s) to engage on. The dashboard in can guide this effort. It enables the user to get a detailed description of the country's SDG challenges, as well as of its corporate engagement history.

To explain the sections:

Country selection: select the country that was identified in the first step of the framework;

Overview: a brief snapshot of the holdings in the selected country;

SDG performance: based on the country selection, here the SDGs will be shown together with the extent of challenges the country faces on achieving them;

SDG targets: progress on an SDG is determined by the country's performance on that SDG's underlying targets. This section therefore shows how the country is performing on relevant SDG targets, which allows the investor to better understand what challenges that must be solved to help improve the country's sustainability performance. For example, if a country performs poorly on SDG 15 – Life on Land, the user can select SDG 15 and see the underlying performance on e.g. protected areas important to the biodiversity, deforestation, biodiversity, and biodiversity threats following from a country's imports. Here, we made a pre-selection of SDG targets to identify those that are most actionable for an investor;

Corporate engagement history: this section shows the engagement themes and the companies that have been engaged with in the country. This corporate engagement history may offer an important driver for selecting an SDG to engage on with a sovereign entity. If an investor already has expertise in engaging on a particular sustainability challenge that links well to an SDG, and if it can secure the cooperation of local corporate actors, then the likelihood of success will be higher. Not only will the engagement team already have a good understanding of the issue in a particular country, the possibility of rallying the support of local corporates on the issue – which these companies might benefit from, for instance in the case when a sovereign benefits from a better rating or lower spreads, corporates could in turn also benefit from better financing terms as the sovereign typically serves as a benchmark – adds to the engagement's legitimacy.

Note that once the investor's expert group selected relevant SDGs, it is important to examine whether there are related goals that are relevant to include. Because the SDGs are integrated, contributions to one SDG can promote, but also deteriorate, progress on another goal. By including related SDGs, there is an opportunity for investors to advance multiple goals at the same time (creating co-benefits) while reducing the risk that contributions to one SDG undermine progress on other goals (avoiding trade-offs). Various efforts are being made to better understand these complex interactions between the goals (e.g. Allen, Metternicht, and Wiedmann Citation2019; Nilsson, Griggs, and Visbeck Citation2016; van Zanten and van Tulder Citation2021). Investors can use such analyses, combined with the insights of sustainability experts, to assess whether there are interrelated SDGs to additionally include in the engagement process.

To illustrate the working of this dashboard using the IPDD's engagement with Brazil, we find in section 3 of the dashboard that this country faces ‘significant challenges’ on SDG 15 – Life on Land (cf. Sachs et al. Citation2020). Digging deeper, ‘major challenges’ are faced on the metric ‘Permanent deforestation (% of forest area, 5-year average)’ which is linked to SDG target 15.2 that aims to halt deforestation. 2019 and 2020 were particularly adverse years, hitting one bad record after the other. Between August 2019 and July 2020, 11,088 sq km of rainforest have been destroyed, a 9.5% increase from the previous year and a 12-year high (BBC Citation2020). And forestry decline is intimately linked to additional sustainability challenges. Poor quality of public institutions and the prevalence of corruption is linked to increased deforestation rates (Pailler Citation2018). In turn, when forests are set on fire or felled and left to decompose to clear land for agricultural purposes, large amounts of greenhouse gasses (GHGs) are emitted into the atmosphere. Globally, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that 23% of total anthropogenic GHGs stem from Agriculture, Forestry and Other land use (IPCC Citation2019), of which tropical deforestation is one of the major sources. Adding to that, deforestation is also one of the main reasons for the loss of biodiversity (e.g. IPBES Citation2019).

Based on this discussion, a group of interconnected SDGs can be identified: increased agricultural activity (linked to SDG 2 – Zero Hunger) and weak institutions (linked to SDG 16 – Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions) drive deforestation. Consequently, deforestation (SDG target 15.2), the loss of biodiversity (target SDG 15.5) and climate change (SDG 13) are negatively affected. The dashboard can be used to obtain an indication of Brazil's progress on each of these goals and sub-targets. For investors to make progress on reducing deforestation, it becomes clear that a broad lens should be applied that takes this nexus of interrelated sustainability challenges into account.

What then is the financial perspective? One of the investors that is a member of the IPDD, Robeco, explains:

As long-term investors in Brazilian bonds and equities it is important to us how Brazil deals with deforestation and climate change. It is not only a matter of social responsibility, but also as a financially material factor in our investment decisions. (Robeco Citation2021)

3.3 How? Organizing the engagement process

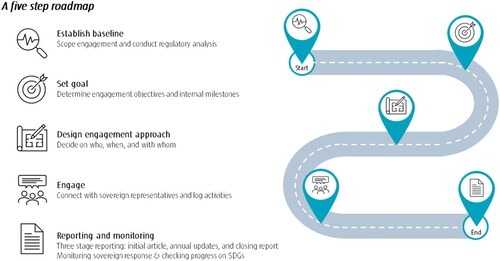

The final part of the framework establishes a roadmap to conduct the engagement with the selected country (following step 1) and the selected SDG(s) and underlying target(s) (following step 2). Because engaging with sovereigns on the SDGs will be demanding, we believe it is crucial to follow a structured approach. This roadmap consists of five steps, as displayed in , that helps investors effectively navigate the engagement process.

Step 1: Establish baseline

The first step is to establish a baseline by understanding the context, challenges and opportunities faced by a country which is vital for a successful engagement. The scope of research required for creating this baseline would comprise of a regulatory and policy analysis of each of the SDGs and sub-targets selected in dashboard 2. This will highlight the present state of the country's actions on the identified SDG(s) and serve as a foundation for designing the engagement agenda. To conduct the analysis in a structured manner, it is suggested to organize the research findings into the following questions:

Is there a lack of policy – including a vision, goal, or ambition – on the SDG(s), as identified in national policy documents?

Is there a lack of regulation – including a legal framework with relevant rules – concerning the SDG(s)?

If there is regulation on the SDG(s), does it have safeguards, such as taxes or penalties?

Does the country have policies that proactively incentivise stakeholders to create positive change on the SDG(s)?

What could an appropriate regulatory framework, including safeguards and incentives, look like for the SDG(s) and the country?

Other – Is there any other sovereign or SDG related information that might be relevant to take into account?

A good starting point for findings answers to these questions is to assess the government's planning for the SDGs. The SDGs are an intergovernmental agreement and governments have committed to work towards their achievement. As a result, many governments are creating plans to implement the goals. Reviewing such plans helps shed light on how countries aim to tackle the sustainability challenges they face, providing an investor with key inputs to the sovereign engagement process.

Step 2: Set goals

Once the baseline research has been conducted, SMART sovereign engagement objectives should be determined. SMART objectives are necessary to determine the success (e.g. Cormier and Elliott Citation2017). SMART engagement objectives mean that they are specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and time-bound. For the engagement objectives to be SMART, it is essential that there is a clear link to the selected SDGs. Moreover, the engagement objectives should clearly align with the investor's as well as the country's interest, to ensure that the dialogue takes a collaborative and constructive approach. These objectives should furthermore contain thresholds that delineate what constitutes a success. Internal milestones may be created to assist the long-term goal of the engagement. Since sovereign engagement can be a long-term process, such internal milestones help ensure sufficient progress as well as regular mapping of the progress made, which will be useful for reporting under Step 5.

The IPDD case gives useful insights. In engaging with Brazil, the investor consortium set five objectives (see IPDD Citation2021):

Significant reduction in deforestation rates, i.e. showing credible efforts to comply with the commitment set down in Brazil's Climate Law, Article 19.

Enforcement of Brazil's Forest Code.

The ability of Brazil's agencies tasked with enforcing environmental and human rights legislation to carry out their mandates effectively, and any legislative developments that may impact forest protection.

Prevention of fires in or near forest areas, in order to avoid a repetition of fires like in 2019.

Public access to data on deforestation, forest cover, tenure and traceability of commodity supply chains.

Step 3: Design engagement approach

To design the engagement approach, the focus should be on three aspects.

The first aspect is to identify which other investors might want to join the engagement process, if any. Hence, the investor must first decide whether the engagement will be a collaborative effort or an individual one. This decision making process requires searching for other investors or theme-based consortiums to collaborate with. There is a clear imperative for undertaking the engagement process in partnership with other investors. A coalition of investors will have more financial assets and external influence, translating in higher (financial) weight and a louder voice. A collective effort thus has more impetus and is likely to be more effective in getting the message through (e.g. Gond and Piani Citation2013). In addition, it is also suggested to involve local corporates in such country dialogue. Large corporates often hold power to impact policies at the country level and by leveraging the corporate relationship investors can strengthen the sovereign engagement.

The second aspect concerns deciding who within the sovereign entity to approach for the engagement. An investor might knock on various doors, so which one to start with? This might be tricky, as one interviewee explains: ‘stepping to political parties is risky because they might easily use you for their own political agendas. That's mixing politics and business which is bad for engagement, investors are not politicians and should stick to the facts’. To navigate this complex environment, we recommend that approaching a country's central bank or treasury officials/debt management offices (DMO) would be an ideal good starting point. The DMOs are experienced with investor inquiries and are well known by country portfolio managers in the investment team. The interviewee further notes: ‘it is prudent to approach the treasury / central bank officials first. They are not involved in the country's politics. They work with investors and are very welcoming to discuss broader sustainability issues’. Should this approach not work, then as a second stage, contact could be made with the country's embassy, since the embassy can help the investor establish linkages with the relevant government officials in the country. Ultimately, a third stage could include having an audience with the specific ministers who hold power to harness reform and can implement concrete actions. Thus, in identifying who to reach out to, we suggest a cascading approach that starts with the central bank (including treasury official and DMOs), then the embassy, and ministerial offices as a final resort.

The third aspect is to determine the timing of the engagement. Initiating the dialogue with the sovereign at the appropriate time is vital for success. Events such as government elections, budget cycles, upcoming events, and media campaigns can prove to be levers for accelerating progress. In this sense, planning the engagement process at the right time can create new urgency on an SDG, or leverage existing momentum for that goal.

Step 4: Engage

Having planned the process in step 3, it is time to start engaging. The appropriate medium to establish first point of contact could be in the form of a letter addressing concerns and followed up with in-person meetings once the issues have been acknowledged. Although this may be a private letter, a public letter brings advantages:

if you write an open letter, or do a press-release, you improve transparency and you can obtain the support of local corporates and stakeholders – but make sure that you leave room for response, the idea is to open the dialogue, not to accuse anyone.

it is important to make it clear to the government that we want to contribute to the country – for us this means that we face lower risks and that we help clients achieve their sustainability ambitions, for the country there is the benefit that it can improve their risk profile, and thus reduce their lending fees.

Illustrating this step with an example from practice, the dialogue with the Brazilian government was initiated through an open letter calling on the government to curb deforestation. Led by PRI, the open letter was signed by 29 global investors representing $3.7 trillion in AuM (Reuters Citation2020a). In response to the letter, a video conference was arranged with Vice President Hamilton Mourão, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Ernesto Araújo, Minister of Agriculture, Tereza Cristina, Minister of Environment Ricardo Salles, and the President of the Central Bank, Roberto Campos Neto.

Throughout the engagement dialogue, we encourage investors to invite the government to share their national planning for the SDGs. As said above, governments have committed to the goals and most are integrating them into their national planning. By inviting governments to share their plans for advancing the goals, rather than solely imposing a list of pre-determined requirements, investors encourage local ownership of the SDGs. Moreover, by aligning with the government's own planning investors signal their willingness for collaborating on tackling sustainability issues in a way that benefits the country, which is likely to be conducive for success.

Step 5: Reporting and monitoring

The last step concerns reporting and monitoring. It is useful to keep a simple and effective reporting structure. This can be done is a threefold manner whereby requisite information and data are made available to the client.

At the start of the engagement, we suggest distributing an initial public statement. This statement should consider the context for engaging with the country, the SDG(s) selected, the specific engagement objectives and a country profile including the findings from the regulatory analysis conducted in Step 1. Then, during the engagement, reporting can take place according to pre-determined timelines, or ad hoc if any reportable activities happens outside the agreed-upon reporting cycle. This implies that maintaining a log of all actions taken throughout the engagement process is important. In these updates, information on the progress made and the internal milestones achieved should be made available. Finally, once the engagement has been finalized, a closing report should be prepared. The purpose of this report is to map and summarize the progress made during the engagement, challenges faced, and future expectations.

Hence, throughout this reporting cycle investors are advised to critically monitor the sovereign's responses and its progress on the SDGs. A positive response to an engagement trajectory is a good start. The next step is to ensure that promises translate into progress. Collecting, and critically reviewing, evidence that can give a credible indication of whether the country really is progressing on the SDGs within the scope of the engagement is key. Public data (such as the indicators provided by the SDG Index), news reports, and NGO perspectives, can all be used to gauge if real progress is being made. Having such supportive evidence ensures that investors do not solely need to rely on a sovereign's words, but that they can validate whether these words have been translated into progress.

Given that investor-led engagement with countries may be sensitive from a sovereignty perspective (PRI Citation2020), transparency to the public is important. Publicly disclosing information on the engagement process, its objectives, and its results, enables citizens, civil-society organizations, and other interested parties to be aware of the investor influencing the public policy space in the country. This helps to ensure that the engagement process is seen as being aligned with the country's interests, rather than it being accused of conflicting with the country's sovereignty.

As a final illustration from the IPDD's engagement with Brazil, the investor group saw and reported positive milestones including:

38 large Brazilian and international companies from multiple sectors sent a letter to the Vice President requiring strict monitoring of environmental breaches and crimes (Statement from the Brazilian Business Sector Citation2020).

The Brazilian government announced a 120 days temporary ban on setting fires in the Amazon (Reuters Citation2020b).

The Central Bank of Brazil launched a ‘Sustainability Dimension’ to the BC # agenda. The dimension amongst other implements the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure, includes BC joining the Network for Greening the Financial System, and the creation of the ‘Green Bureau’ rural credit (Central Bank of Brazil Citation2020).

The fact that the Brazilian government is open to discuss these matters with investors is an important sign, and we’re grateful for having that, but it’s not the ultimate goal itself. The ultimate goal is to achieve a significant reduction in deforestation rates and proper law enforcement against environmental crimes. This is why, together with the other investors from the Investor Policy Dialogue on Deforestation, we had this second call with the Vice President of Brazil. We are not able to solve global challenges like climate change and deforestation on our own, but together we can contribute to positive change (Robeco Citation2021)

Having secured this positive response, the next step is to use public data, news articles, and NGO reports to monitor whether these milestones are being upheld, and whether the country's rate of deforestation is indeed declining. Time will tell whether this case of investor-led engagement with the government of Brazil will be positively linked with improved environmental sustainability.

4. Concluding remarks

Investor-led engagement with countries on sustainability topics is a new phenomenon. Engagement can be an important tool with which sovereign debt investors can operationalize their sustainable investing strategy. By engaging with countries in an active dialogue, an investor can encourage the country to improve its performance on sustainability topics that not only are important to advancing sustainable development in general, but also are relevant for the investor's strategies. In turn, finding ways to improve its sustainability profile can help a country to gain better access to capital markets and obtain financing at lower costs.

Because this is a novel approach to sustainable investing, in this methodology and policy paper we introduced a framework that sovereign debt investors can use to operationalize their engagement with countries on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). We conducted interviews with an investor and studied a recent case that saw a collective of investors engage with the government of Brazil on the topic of halting deforestation. On this basis, we created a framework that helps investors answer three questions that collectively guide the sovereign engagement process: (i) who to engage with; (ii) what to engage on; and (iii) how to engage. The first question identifies relevant countries to engage with based on the investor's (public and private) investment exposure to that country, as well as the overall level of progress that the country is making on the SDGs. The second question defines which SDGs and sub-targets are most relevant to engage on by, among others, assessing how a country is progressing on each of the goals, and by leveraging the investor's experience with those SDGs. Finally, the third question lays out a detailed roadmap that investors can use to start engaging with the defined countries on the selected SDGs – from the initial ‘knock on the door’ to the final reporting. The framework can be used by investors to engage with sovereign entities it already has in existing portfolios, as well as to identify new investment opportunities based on the potential impacts that might be achieved on specific SDGs in particular countries.

At a time in which all 193 UN member states committed to work towards achieving the SDGs by 2030, and in which many investors are identifying novel approaches to integrating sustainability into their investment processes, we posit that engagement is a key mechanism for success. Progress can be made if investors and countries can create shared sustainability objectives, and work together on achieving them. The sovereign SDG engagement framework introduced in this paper aims to help investors and countries achieve their shared sustainability objectives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See e.g. Accessed 9 February 2021. https://www.tropicalforestalliance.org/en/collective-action-agenda/investors-policy-dialogue-on-deforestation-ipdd-initiative/.

3 To illustrate, between 2006 and 2020 the number of signatories to the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) grew from 62 to 3,038, with a corresponding increase in AuM from USD 6.5 trillion to USD 103.4 trillion (PRI Citation2021).

4 To put these figures into context, the United States’ GDP in 2019 totalled USD 21.4 trillion.

5 Note that the SDG Index is not to be used for commercial purposes – we use it here for illustrative purposes and for knowledge sharing.

References

- Agliardi, E., and R. Agliardi. 2019. “Financing Environmentally-Sustainable Projects with Green Bonds.” Environment and Development Economics 24 (6): 608–623.

- Allen, C., G. Metternicht, and T. Wiedmann. 2019. “Prioritising SDG Targets: Assessing Baselines, Gaps and Interlinkages.” Sustainability Science 14 (2): 421–438. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0596-8.

- Atta-Darkua, V., D. Chambers, E. Dimson, Z. Ran, and T. Yu. 2020. “Strategies for Responsible Investing: Emerging Academic Evidence.” The Journal of Portfolio Management 46 (3): 26–35.

- Azhgaliyeva, D., A. Kapoor, and Y. Liu. 2020. “Green Bonds for Financing Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency in South-East Asia: A Review of Policies.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 10 (2): 113–140.

- Badía, G., V. Pina, and L. Torres. 2019. “Financial Performance of Government Bond Portfolios Based on Environmental, Social and Governance Criteria.” Sustainability 11 (9): 2514.

- Baker, M., D. Bergstresser, G. Serafeim, and J. Wurgler. 2018. Financing the Response to Climate Change: The Pricing and Ownership of US Green Bonds (No. w25194). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Banga, J. 2019. “The Green Bond Market: A Potential Source of Climate Finance for Developing Countries.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 9 (1): 17–32.

- BBC. 2020, November 30. “Brazil’s Amazon: Deforestation ‘Surges to 12-year High’.” bbc.com. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-55130304#:~:text=Deforestation%20of%20the%20Amazon%20rainforest,increase%20from%20the%20previous%20year.

- Blitz, D., L. Swinkels, and J. A. van Zanten. 2021. “Does Sustainable Investing Deprive Unsustainable Firms of Fresh Capital?” The Journal of Impact and ESG Investing 1 (3): 10–25. doi:10.3905/jesg.2021.1.012.

- Brest, P., R. J. Gilson, and M. A. Wolfson. 2018. “Essay: How Investors Can (and Can’t) Create Social Value.” Journal of Corporation Law 44: 205.

- Capelle-Blancard, G., P. Crifo, M. A. Diaye, R. Oueghlissi, and B. Scholtens. 2019. “Sovereign Bond Yield Spreads and Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis of OECD Countries.” Journal of Banking & Finance 98: 156–169.

- Central Bank of Brazil. 2020, September 8. BC# Sustainability. https://www.bcb.gov.br/content/about/presentationstexts/BCB_Agenda_BChashtag_Sustainability_Dimension_Sep2020.pdf.

- Chiesa, M., and S. Barua. 2019. “The Surge of Impact Borrowing: The Magnitude and Determinants of Green Bond Supply and its Heterogeneity Across Markets.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment 9 (2): 138–161.

- Cormier, R., and M. Elliott. 2017. “SMART Marine Goals, Targets and Management–is SDG 14 Operational or Aspirational, is ‘Life Below Water’sinking or Swimming?” Marine Pollution Bulletin 123 (1-2): 28–33.

- Drut, B. 2010. “Sovereign Bonds and Socially Responsible Investment.” Journal of Business Ethics 92 (1): 131–145.

- Duyvesteyn, J., M. Martens, and P. Verwijmeren. 2016. “Political Risk and Expected Government Bond Returns.” Journal of Empirical Finance 38: 498–512.

- European Commission. 2019. Guidelines on Reporting Climate-Related Information. Brussels: European Union.

- Flammer, C. 2020. “Green Bonds: Effectiveness and Implications for Public Policy.” Environmental and Energy Policy and the Economy 1 (1): 95–128.

- Gond, J. P., and V. Piani. 2013. “Enabling Institutional Investors’ Collective Action: The Role of the Principles for Responsible Investment Initiative.” Business & Society 52 (1): 64–104.

- ICMA. 2020. Bond Market Size. Accessed 8 January 2021. https://www.icmagroup.org/Regulatory-Policy-and-Market-Practice/Secondary-Markets/bond-market-size/.

- IPBES. 2019. Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat.

- IPCC. 2019. Climate Change and Land: an IPCC Special Report on Climate Change, Desertification, Land Degradation, Sustainable Land Management, Food Security, and Greenhouse gas Fluxes in Terrestrial Ecosystems. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- IPDD. 2021. “Investors Policy Dialogue on Deforestation (IPDD) Initiative.” Tropical Forest Alliance. https://www.tropicalforestalliance.org/en/collective-action-agenda/investors-policy-dialogue-on-deforestation-ipdd-initiative/.

- Kölbel, J. F., F. Heeb, F. Paetzold, and T. Busch. 2020. “Can Sustainable Investing Save the World? Reviewing the Mechanisms of Investor Impact.” Organization & Environment 33 (4): 554–574.

- MacFeely, S. 2019. “The Big (Data) Bang: Opportunities and Challenges for Compiling SDG Indicators.” Global Policy 10: 121–133.

- Maltais, A., and B. Nykvist. 2020. “Understanding the Role of Green Bonds in Advancing Sustainability.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. doi:10.1080/20430795.2020.1724864.

- Margaretic, P., and S. Pouget. 2018. “Sovereign Bond Spreads and Extra-Financial Performance: An Empirical Analysis of Emerging Markets.” International Review of Economics & Finance 58: 340–355.

- Moody’s. 2021, January 18. New Scores Depict Varied, Often Credit-Negative Impact of ESG Factors for sovereigns. Accessed from Moody’s: https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-New-scores-depict-varied-often-credit-negative-impact-of–PBC_1259861.

- Nedopil Wang, C., M. Lund Larsen, and Y. Wang. 2020. “Addressing the Missing Linkage in Sustainable Finance: the ‘SDG Finance Taxonomy’.” Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. doi:10.1080/20430795.2020.1796101.

- Nilsson, M., D. Griggs, and M. Visbeck. 2016. “Policy: Map the Interactions Between Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature 534 (7607): 320–322. doi:10.1038/534320a.

- Pailler, S. 2018. “Re-election Incentives and Deforestation Cycles in the Brazilian Amazon.” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 88: 345–365.

- PRI. 2020. “ESG Engagement for Sovereign Debt Investors.” Accessed 17 December 2020. https://www.unpri.org/download?ac=12018.

- PRI. 2021. “About the PRI.” Accessed 15 February 2021. https://www.unpri.org/pri/about-the-pri.

- Reuters. 2020a. “Global Investors Demand to Meet Brazil Diplomats over Deforestation.” Accessed 8 January 2021. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-environment-investors/global-investors-demand-to-meet-brazil-diplomats-over-deforestation-idUKKBN23U0L8.

- Reuters. 2020b. “Brazil Bans Fires in Amazon Rainforest as Investors Demand Results.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-environment-idUSKBN24A2DV.

- Robeco. 2021. “Group of Investors Meet Again with Vice President of Brazil to Discuss Deforestation.” Accessed 1 February 2021. https://www.robeco.com/en/media/news-item/2021/group-of-investors-meet-again-with-vice-president-of-brazil.html.

- Sachs, J. D., G. Schmidt-Traub, C. Kroll, G. Lafortune, G. Fuller, and F. Woelm. 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19. Sustainable Development Report 2020. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schramade, W. 2017. “Investing in the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Opportunities for Companies and Investors.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 29 (2): 87–99.

- Statement from the Brazilian Business Sector. 2020. Accessed 16 January 2021. http://tozzinifreire.com.br/assets/conteudo/uploads_editor/Statement_from_the_Brazilian_Bus.pdf.

- Stockholm Resilience Centre. 2016. How Food Connects All the SDGs. Accessed 18 November 2020. https://www.stockholmresilience.org/research/research-news/2016-06-14-how-food-connects-all-the-sdgs.html.

- Swinkels, L. 2021. “Allocating to Green Bonds.” SSRN Working Paper. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3813967.

- UN. 2015. Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- UN. 2017. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017. New York: United Nations.

- UN. 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2020. New York: United Nations.

- van Zanten, J. A., and R. van Tulder. 2018. “Multinational Enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An Institutional Approach to Corporate Engagement.” Journal of International Business Policy 1 (3): 208–233.

- van Zanten, J. A., and R. van Tulder. 2020. “Beyond COVID-19: Applying “SDG Logics” for Resilient Transformations.” Journal of International Business Policy 3 (4): 451–464.

- van Zanten, J. A., and R. van Tulder. 2021. “Analyzing Companies’ Interactions with the Sustainable Development Goals Through Network Analysis: Four Corporate Sustainability Imperatives.” Business Strategy and the Environment, doi:10.1002/bse.2753.

- Zhan, J. X., and A. U. Santos-Paulino. 2021. “Investing in the Sustainable Development Goals: Mobilization, Channeling, and Impact.” Journal of International Business Policy 4: 166–183. doi:10.1057/s42214-020-00093-3.