ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to current debates in the field of entrepreneurship on the persistent gender gap in capital allocation to entrepreneurs. Drawing on recent theories of entrepreneurial belonging (Stead, V. 2017. “Belonging and Women Entrepreneurs: Women’s Navigation of Gendered Assumptions in Entrepreneurial Practice.” International Small Business Journal 35 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1177/0266242615594413; Birkner, S. 2020. “To Belong or Not to Belong, That Is the Question?! Explorative Insights on Liminal Gender States within Women’s STEMpreneurship.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 16: 115–136. doi:10.1007/s11365-019-00605-5), we conducted narrative research to gain rare insights into the gendered challenges faced by female fund managers in private equity in Sub-Saharan Africa during the fundraising process. We discover a triple dissonance between the feminine normative frames of womanhood and the male normative frames of entrepreneurship and private equity, compounded by intersectional stereotypes of Africa. Our research offers novel, exploratory insights into what has been a blind spot in the emerging field of gender-lens investing: how gender bias in capital allocation to entrepreneurs is reinforced by gender bias in capital allocation to fund managers. We conclude that the field must move beyond viewing African women as beneficiaries of empowerment and put them in power of investment decisions.

Empowerment is receiving capital to grow a business. Power is deciding how capital is allocated and which businesses grow.

1. Introduction

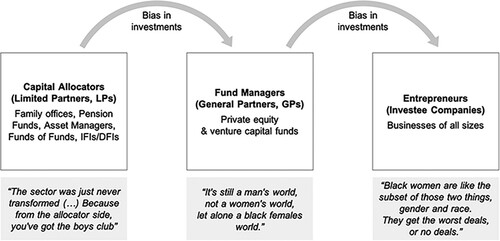

The gender gap in capital allocation to women entrepreneurs globally is well documented. Recent scholarship has deepened our understanding of how structural barriers and gender bias are drivers of the gender gap in entrepreneurship finance. Gender lens investing has emerged as a global trend among investors to close this gap by promoting investments in women-owned and -led businesses. This has led to an unprecedented focus among investment practitioners and policy-makers on women entrepreneurs as beneficiaries of investments. Interestingly enough, the question of who holds power over investment decisions has remained largely unchallenged. This raises the question whether the gender gap in entrepreneurship finance can be truly overcome while the gender gap on the capital allocators’ side persists.

Our research builds on recent entrepreneurship scholarship on the genderedness of entrepreneurial belonging (Stead Citation2017; Birkner Citation2020) and extends it to the challenges experienced by female fund managers in the private equity space, particularly in the fundraising process. This paper aims to offer explorative insights into the dissonance between feminine normative frames of womanhood and male normative frames of both entrepreneurship as well as private equity fund management. By so doing, we explore how the capital allocation to female fund managers reinforces the gender gap in capital allocation to women entrepreneurs. The question of how investment decisions are made and who gets to make those decisions is critical to deepen our understanding of how to build a field of gender lens investing, which is inclusive, sustainable and scalable.

Drawing on recent theories of entrepreneurial belonging (Stead Citation2017; Birkner Citation2020), we conducted narrative research with 23 female fund managers across Sub-Saharan Africa to gain rare insights into the gendered challenges faced by female fund managers in the fundraising process. We discover a triple dissonance between the feminine normative frames of womanhood and the male normative frames of entrepreneurship and private equity, compounded by intersectional stereotypes of Africa. Our research offers novel, exploratory insights into what has been a blind spot in the emerging field of gender-lens investing: how gender bias in capital allocation to entrepreneurs is reinforced by gender bias in capital allocation to fund managers.

We respond to calls for more research on the supply side of capital to investigate the persistent gender gap (Brush et al. Citation2018) as well as for research focusing on women’s entrepreneurship in the global South (Yadav and Unni Citation2016; Leitch, Welter, and Henry Citation2018). Our paper contributes to the current debates on gender and entrepreneurship as well as on the key question of why investors allocate significantly more capital to male entrepreneurs. Our research findings shed further light on how gender stereotypes lead investors to turn to simple heuristics leading to cognitive bias, which distort decisions on capital allocation (Balachandra et al. Citation2013, Citation2019; Brooks et al. Citation2014; Malmström, Johansson, and Wincent Citation2017).

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Gender gaps in capital allocation

Women-led businesses receive only 7% of private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) in emerging markets (IFC Citation2019). A key question and ongoing debate in the entrepreneurship literature is why investors allocate significantly more capital to male than to female entrepreneurs (Balachandra et al. Citation2013, Citation2019; Leitch, Welter, and Henry Citation2018). Recent entrepreneurship scholarship has advanced our understanding of unconscious gender bias in investment decision-making. Empirical studies have found investor-driven biases directly affecting the amount of capital allocated to male versus female entrepreneurs: Investors were found to use rhetoric based on gender stereotypes when evaluating entrepreneurs for investment decisions (Malmström, Johansson, and Wincent Citation2017), ask men promotion-oriented questions and women prevention-oriented questions (Kanze et al. Citation2018), and have a bias towards ‘attractive’ male entrepreneurs (Brooks et al. Citation2014). In addition to gender bias in entrepreneurship and investment discourse, scholars have investigated gender bias in the structure of capital markets including homophily among investors (Alsos and Ljunggren Citation2017; Brush et al. Citation2017, Citation2019).

The gender finance gap is often attributed to the fact that women are significantly underrepresented among investment decision-makers, holding only 10% of all senior positions in PE and VC firms in developed markets and 8% in emerging markets excluding China (IFC Citation2019). Globally, the gender and racial gap in the fund management industry is just as sobering: Less than 1.3% of the $69.1 trillion global financial assets under management are managed by women and people of colour (Lyons-Padilla et al. Citation2019).

Homophily theory suggests a tendency of people to associate and bond with people who are demographically similar to them (Brashears Citation2008). This offers one explanation why all-men teams are four times more likely to receive venture capital from investors (who are predominantly men) than teams with even one woman (Brush et al. Citation2018). It is therefore commonly theorized that gender bias in capital allocation to entrepreneurs can best be overcome by increasing women’s representation among investors and in institutional investment decision-making bodies. Indeed, female partners in PE and VC funds have been found to invest almost twice as much in women entrepreneurs than male partners (IFC Citation2019). According to research by Brush et al. (Citation2014), venture capital firms with female partners are twice as likely to invest in companies with women on the management team and three times more likely to invest in companies with a female CEO. Recent studies from the global South have shed light on intersectional biases in entrepreneurship and finance (Gonzales Martínez et al. Citation2020; Gunewardena and Seck Citation2020).

This raises the question why women’s underrepresentation in investment decision-making is so persistent. Interestingly, recent research focusing specifically on the capital allocation from institutional investors (limited partners, LPs) to fund managers (general partners, GPs) finds that this lack of diversity among fund managers is not only a pipeline problem, but that there are also systemic barriers and investor biases at play (Lyons-Padilla et al. Citation2019). Fund managers play a crucial role in the capital allocation to entrepreneurs, but are themselves dependent on capital allocation from investors. This suggests that gender bias in capital allocation to entrepreneurs is reinforced by gender bias in capital allocation to fund managers.

In the African context, women are particularly underrepresented in private equity with women in senior roles accounting for just 7.6% (compared to 11.8% in Asia) (Mchunu and Brewis Citation2018). However, there is a noticeable upward trend. The number of women entering male-dominated spaces like PE and VC industry events is growing. These trailblazers are said to play an important role in breaking down gender stereotypes and barriers. While there seems to be no shortage of women entering the industry, factors like ‘male domination of corporate cultures, masculine leadership still considered to be the default norm, and inadequate access to female mentors’ are responsible for the persistent glass-ceiling (ibid, 12).

2.2. Gendered normative frames of entrepreneurship

Although often presented as a gender-neutral space, entrepreneurship itself is fundamentally gendered (Ahl Citation2007; Henry, Foss, and Ahl Citation2016). Therefore, entrepreneurship cannot be fully analysed from a gender-neutral perspective (Ahl and Marlow Citation2012), making a gender lens critical to fully understand dynamics in entrepreneurship and investment decisions. Following Scott (Citation1986), gender is not only ‘a constitutive element of social relationships based on perceived differences between the sexes’, but also ‘a primary way of signifying relationships of power’ (1067).

Scholars in the field of women’s entrepreneurship have long observed a masculine normative frame of entrepreneurship, privileging men as ‘the norm’ and women as ‘the other’ within research and practice (Bruni, Poggio, and Gherardi Citation2004; Ahl Citation2004; Citation2006; Birkner Citation2020). Consequently, entrepreneurial belonging has mostly been masculine biased (Ahl Citation2006; Ahl and Marlow Citation2012; Díaz-García and Welter Citation2013; Birkner Citation2020), creating a dissonance between discourse on womanhood and entrepreneurship (Ahl Citation2002; Citation2006; Díaz-García and Welter Citation2013; Swail and Marlow Citation2017). As a result, women entrepreneurs have been subordinated and stereotyped as, for example, only starting businesses in feminine gendered industries like beauty and fashion, dubbed the ‘pink ghetto myth’ (Adler Citation1999).

Given persisting gender bias in private equity and roles of financial decision-making (Barber, Scherbina, and Schlusche Citation2017; Brush et al. Citation2018; Lyons-Padilla et al. Citation2019), masculinity is considered ‘the norm’ and femininity ‘the other’, analogously to entrepreneurship. There is thus also a dissonance between the masculine normative frame of private equity and fund management on the one hand, and the feminine normative frame of womanhood on the other hand.

Scholarship from Sub-Saharan Africa has explored the social norms around womanhood in the regional context and shown how gendered stereotypes and social expectations about women’s role in society act as impediments to women’s entrepreneurship (Adom et al. Citation2018; Etim and Iwu Citation2019). Studies with an intersectional lens found that entrepreneurship is associated with whiteness, which has led black women entrepreneurs to experience a sense of double alienation (Dy, Marlow, and Martin Citation2017; Nambiar, Sutherland, and Scheepers Citation2020). South African scholars have shown how race and gender are drivers of the entrepreneurial finance gap (Musk, Botha, and Neil Citation2017).

Recent entrepreneurial literature has explored how women entrepreneurs accomplish entrepreneurial belonging and how they ‘do’ and ‘redo’ gender in a male-dominated entrepreneurial context (Birkner Citation2020; Díaz-García and Welter Citation2013). Birkner (Citation2020) analyses how women entrepreneurs need to continuously balance the state of belonging ‘betwixt and between’ (Turner Citation1967) feminine normative frames of womanhood and masculine normative frames of entrepreneurship. She coined the term ‘entrepreneurial liminal gender states’ to describe the state of continuously balancing whether – in the words of Stead (Citation2017, 61) – ‘to fit in or to feel out of place, to be an insider or to be excluded, to feel accepted or to feel marginalized’.

2.3. Entrepreneurial belonging and female fund managers

The study of female fund managers and the concept of belonging is particularly interesting, due to the double dissonance between feminine normative frames of womanhood and masculine normative frames of both entrepreneurship and financial decision-making. For fund managers, the fundraising process, in particular, is a key moment of truth and when the stakes are the highest: to be or not to be a fund manager is determined by the ability to raise a fund that is subsequently managed. While being an entrepreneur does not necessarily require having access to capital (although access to capital is, of course, a key ingredient for entrepreneurial growth and an important aspect of belonging to the entrepreneurship community), a private equity fund manager, by definition, is a person who manages a fund. Therefore, the whole identity of a fund manager is contingent on being able to raise enough capital for a fund. The fundraising process is therefore the phase in the journey of a fund manager when his or her belonging is most challenged. Interestingly then, gender bias in capital allocation to female fund managers is not only a threat to their entrepreneurial success but also to their identity as a fund manager.

Prior research cited above suggests that the double dissonance of womanhood and entrepreneurship as well as financial decision-making may cause investors to turn to heuristics leading to cognitive bias in their assessment of female fund manager, which in turn may distort their decisions on capital allocation. This is likely to be particularly pronounced where female fund managers seek to raise their own fund with their own firm rather than raising and managing a fund on behalf of an established private equity firm. An interesting question that emerges then is how female fund managers perform belonging once confronted with gendered challenges in their interactions with investors. Furthermore, female fund managers with a gender lens investing strategy may experience even greater challenges in their interaction with investors who may not only be biased towards the female fund manager herself but also towards the strategy of investing in women entrepreneurs.

This paper focuses on two central research questions:

What are the gendered challenges female fund managers in Sub-Saharan Africa experience during the fundraising process in the male-dominated field of private equity?

How is their belonging challenged when female fund managers seek to disrupt the way capital is allocated to entrepreneurs?

3. Research design and method

We draw on recent theory of belonging developed by Stead (Citation2017), conceptualizing entrepreneurial belonging as relational, dynamic and gendered, to investigate the challenges encountered by female fund managers in Sub-Saharan Africa during the fundraising process.

We chose an exploratory qualitative research design to gain rare insights into the challenges faced by female fund managers during the fundraising process. By so doing, we respond to calls for qualitative studies using narrative analysis to explore women’s performing of belonging in entrepreneurial careers (Stead Citation2017). Narrative analysis often reveals turning points in the journey of the protagonist and is particularly well-suited to investigate how female fund managers experience challenges in the fundraising process and perform belonging in a male-dominated field.

We conducted narrative interviews (Creswell and Poth Citation2017; Riessman Citation2008) with 23 female fund managers in Sub-Saharan Africa (representing 21 funds, including two funds with co-managers). To our knowledge, there is no public data available on the total number of female fund managers in Africa. We conducted a mapping of the universe of female fund managers on the continent through desk research, direct outreach to fund manager networks, and snowball sampling. We were able to identify a total of 28 women-led funds in the private equity space across Sub-Saharan Africa and we aimed to interview as many of them as possible. Nine female fund managers in our sample are from South Africa, six from West Africa (Nigeria, Ghana, Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire) and five from East Africa (based in Kenya, often with regionals strategies). The majority of female fund managers in the region are on the journey to raise their own fund (rather than manage a fund for an established private equity firm) and are still in the fundraising process. shows key characteristics of the female fund managers included in our sample. It illustrates the diversity in investment strategies from venture capital to growth equity to turnaround as well as the diversity of target investee companies both in terms of size and sector. Following the recommendation of several female fund managers, we also conducted a narrative interview with an established male fund manager who plays a key role in supporting female fund managers across various countries in Sub-Saharan Africa as a male ally.

Table 1. Sample.

Each interview took between 45 and 120 min, was conducted by video or audio call, and recorded. We conducted thematic data analysis following Riessman (Citation2008). All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed with the qualitative data analysis software NVIVO. Each interview served as a stand-alone entity to explore individual perspectives on the experiences and challenges on the journey of female fund managers and the performance of belonging. In a second stage, we analysed cross-case patterns to identify commonalities of their experiences with investors and peers, challenges in the fundraising process, as well as strategies and tactics of performing belonging.

4. Findings

4.1. Motivation to enter ‘a man’s world’

Our exploratory research revealed three main reasons why women decide to become fund managers and raise their own funds in Sub-Saharan Africa. What they all have in common is the motivation to change the way capital is invested in local entrepreneurs. They have all observed how women entrepreneurs, and in some regions (South Africa and East Africa) black entrepreneurs, as well as certain sectors have received significantly less capital from private equity and venture capital funds. As fund managers who make those investment decisions, they want to change that dynamic.

And it struck me that actually I hadn't invested in women. (…) I found I was (…) looking in the same places where everyone else in the field was looking. And so therefore realized that we had a huge blind spot (…). (Nigerian female fund manager)

I've actually been able to be in institutions that have given me an opportunity to learn amazing things (…), but somehow, I can't break the ceiling. And the ceiling is: you don't belong in that decision-making role in finance. You belong, if you're maybe supporting somebody in that decision-making role. But it shouldn't be you. (Kenyan female fund manager)

There are a lot of women doing the work of partner, but they are just not carrying the title. (Ghanaian female fund manager)

And so part of my argument of getting into the space was really shaking things up and saying ‘I'm here and I'm not going anywhere, and we have to start doing things differently.’ (South African female fund manager)

When I see women like [African female fund manager], I'm really excited, and she’s one of the women that really inspired me to do this. She started and she's really built her firm very well. (West African female fund manager)

It's very hard and it's still a man's world, not a women's world, let alone a black females world. (West African female fund manager)

So you're dealing with mostly men, mostly white, who've been very successful. (South African female fund manager)

4.2. Moment of truth: the fundraising journey

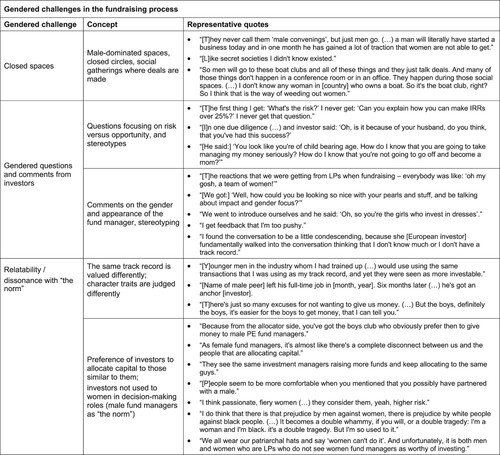

As we laid out above, the fundraising journey is a key moment of truth when the belonging of female fund managers is most challenged. While first-time fund managers in general face particular challenges during fundraising, female fund managers have observed some notable gendered differences, which can be clustered along three dimensions summarized with illustrative quotes in .

First, private equity spaces where relationships are built and deals are discussed are male-dominated, tend to be closed circles, and are often in the form of social gatherings which only insiders know of or are invited to.

Second, female fund managers receive gendered questions and gendered comments from investors. This includes risk-oriented questions (Kanze et al. Citation2018) and remarks stereotyping female fund managers as wives and (potential) mothers (Malmström, Johansson, and Wincent Citation2017).

Third, they observe how male peers with a similar career trajectory succeed in raising their funds faster, because their track record and their character are judged differently. Closely related to this point, female fund managers observe a general preference of investors to allocate capital to those who are similar to them. Furthermore, they note that investors are not used to seeing women in financial decision-making roles, so male fund managers are seen as ‘the norm’ and women as ‘the other’.

The majority of them are white males in their 40s, 50s, 60s. They see the same investment managers raising more funds and keep allocating to the same guys. There's just no transformation. So there are almost no female-owned fund managers that are being supported, let alone black-owned fund managers being supported. (South African female fund manager)

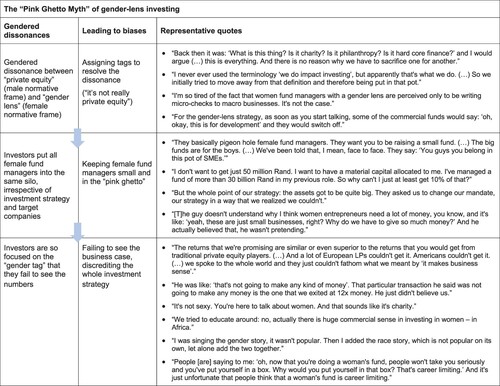

4.3. The pink ghetto myth

4.3.1. Diversity of investment strategies

The investment strategies and target companies of female fund managers are very diverse, as illustrated by . The majority of female fund managers has an explicit gender-lens strategy to invest in businesses that are women-owned or -led, create quality employment for women, and/or empower women along the value chain.

Many adopt a gender lens when sourcing investments, others focus more on transforming the business with a gender lens during the value creation phase in the portfolio after the initial investment is made. The latter is especially the case where the investment strategy focuses on larger corporates or on transforming sectors which have traditionally been male dominated.

I want to get women into ownership of sizeable SMEs, not just small SMEs. (…) What I'm saying is: I'm going to create them in the same way that South Africa created black ownership through legislated black economic empowerment share target. That's my thinking, to use a similar concept and create women ownership in the same way. (South African female fund manager)

Female fund managers in particularly male-dominated investment spaces, such as venture capital for tech companies, have started to notice how women entrepreneurs emerge and become more visible in those fields:

We are starting to see a shift in terms of female-started organizations, specifically maybe in the last 12 months, that are approaching us because we, you know, we look like them, we sound like them. (South African female fund manager)

4.3.2. Gendered dissonance: a single silo

Despite this diversity in investment strategies and target investee companies, female fund managers have experienced gendered dissonances as soon as they mention any kind of ‘gender lens’ to investors. These dissonances can be broadly structured into three categories ().

First, the combination of private equity (male normative frame) and gender lens (female normative frame) triggers a dissonance in relation to the status quo of ‘the norm’ of ‘how private equity works’. To resolve this dissonance and reconcile the investment proposition with the status quo, investors assign certain tags or labels to female fund managers as soon as they mention a gender lens.

Back then it was: What is this thing? Is it charity? Is it philanthropy? Is it hard core finance? (Nigerian female fund manager)

They basically pigeonhole female fund managers. They want you to be raising a small fund (…), so when you say to them: ‘Guys, I actually want to raise a significant fund’, they actually discourage you from doing that. (…) because they also pigeonhole you under ‘impact’. And for them ‘impact’ is ‘you're supporting SMEs’. (…) So, and this is where they see female fund managers. The big funds are for the boys. (South African female fund manager pitching to international investors)

He was like: ‘that's not going to make any kind of money’. That particular transaction he said was not going to make any money is the one that we exited at 12x money. He just didn't believe us. (Pan-African female fund manager)

They [international investors] were not used to two strong African women going to market and saying: ‘we're trying to raise a 100 million USD to invest in other women in Africa’, because they thought that African women in the main sell tomatoes on the side of the road. Yes, we've got lots of women selling tomatoes and peanuts on the side of the road, but we also have lots of women that are running substantial businesses, scalable businesses and businesses that can actually become global businesses for that matter. (…) the returns that we're promising are similar or even superior to the returns that you would get from traditional private equity players. (…) And a lot of European LPs couldn't get it. Americans couldn't get it. (…) we spoke to the whole world and they just couldn't fathom what we meant by ‘it makes business sense’. (Pan-African female fund manager)

We were literally told: ‘don't dress up so smartly when you're presenting to investors, because it doesn't marry well with the focus area that you are talking about.’ It was almost like we should be dower and dull, and I remember we actually asked one of the investors who had given that feedback that: ‘Are you saying that we're not poor enough? Would you tell a man that his suit looks too tailored?’ (West African female fund manager)

Consequently, a major theme that emerged from our research is that female fund managers regularly experience how both local and international investors try to keep them small. This even holds true for female fund managers who are modelling the norm, that is, they are raising funds with a target size above $100 million, invest in corporates with a growth strategy, and have a track record in this investment segment.

I mean, he said to us: ‘No, no, no, no, no, female – even though you guys have got this track record, you've got a balance sheet, a huge balance sheet of over 200 million USD. But actually, we think that you guys would be better off applying for the SME fund bucket.’ (…) We said: ‘No. Actually, we are not going to be applying for that pot. (…) We want to raise a fund of 100–150 million USD. Therefore, sorry, we're not now going to change our strategy just to suit you, because you're seeing a bunch of women and you've got this impact pool of funds and you think that impact, SME, women all go together.’ (South African female fund manager pitching to international investors)

4.4. Tempered disruption: re-defining how capital should be allocated

Our research revealed fascinating strategies and tactics female fund managers across the continent employ to enter male-dominated spaces, build networks, and secure meetings. These mirror the five forms of belonging identified by Stead (Citation2017) for women entrepreneurs: by proxy, concealment, modelling the norm, identity-switching, and, above all, tempered disruption. We also find that these strategies of performing belonging are shaped by intersecting factors including gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and (perceived) motherhood. We will elaborate on those in a separate paper. In this section we focus on the key highlights of performing belonging, which are directly related to disrupting the way in which capital is allocated to entrepreneurs.

Female fund managers have long been, or have quickly become, familiar with the contemporary rules of the game and are able to model the norm when necessary. But given their motivation to raise their own fund in the first place (as described earlier), they prefer to consciously do things differently, engaging in tempered disruption: redefining who and what a fund manager is and how capital should be allocated.

In response to the gendered dissonance, which they have experienced during fundraising, they have developed sophisticated strategies to reposition their investment proposition in a way that resonates with investors. By doing so, they model the norm in their language and pitching approach, but stay true to their gender-lens investment strategy and their purpose of doing things differently. In practice, this is often a balancing act. Those who are too disruptive pay the price by seeing their reputation and credibility adversely affected, getting bullied and being denied access to spaces and networks that are critical for success. Those who strike the right balance between modelling the norm and disruption, by tempering their disruption, often experience turning points in their journey and achieve milestones of belonging.

A female fund manager from South Africa narrated how she was invited to speak at a major private equity conference. At that time, there was a specific gender justice incident in the country she was very upset about and which to her was clearly linked to the high levels of inequality in the country and the lack of diversity in financial decision-making. One of her female investor partners encouraged her to use the speaking opportunity for disruption, but to temper it by employing a language that models the norm:

And she said: ‘you've got an opportunity to speak on such a platform where you can actually make a difference. But you have to understand that pissing them off doesn't make a difference. And so how do you speak to them in their language, which is money and returns?’

I think it moved my pitch, even my positioning, from a crusader black feminist to an investor. I got into the space. And before I was like: ‘you need to be investing in women’ – more like that, just the crusader black feminist, you know, making noise in the industry. But now it was like ‘aha’ - actually seeing the money in this place. (South African female fund manager)

I've been very deliberate in making sure that nobody can pin me into any specific pot. Others call me a private equity player, because if I have to wear that hat, I do. Others call me a VC player. Others call me an accelerator, whatever. (…) [A]s a woman, my attitude has been to say: this country needs to achieve its full potential and we need to do what is necessary for us to achieve our full potential. And that has then meant that we cannot allow ourselves to be siloed, but rather saying: this is the problem and it requires a multipronged strategy to solve. (South African female fund manager)

I actually challenged the president of [large development bank] on this, because I would be on different forums with him. And he would always talk about ‘we've invested in [name of women-led fund]’. So I said to him: ‘you know, Africa has almost 500 million women. Every time I see you, you talk about investing in only one fund.’ And we actually became friends through that, because he said to me, ‘that is so true.’ (West African female fund manager)

I said to her: it doesn't matter how you get into the space, just make sure that you're doing something right with what you've been given. Just make sure you do something right. (South African female fund manager)

[W]hat we're doing is beyond just fundraising, we're also building a whole sector in Africa. I tell you, it's a very daunting responsibility that those of us who are the first to lead women-led funds are actually setting an example. (West African female fund manager)

I'm hoping that we're the first and only women who will ever have to go through that kind of experience (…) It does take pioneers to create a path for others and hopefully make the path a bit smoother for those that follow. (…) it has not been an easy journey. (…) It was about changing the mindset of the world. (Pan-African female fund manager)

And I was quite surprised to hear even the male guys on the podium talking about investing with a gender lens or looking at gender diverse management teams. (Pan-African female fund manager)

I'm beginning to see a change among foreign investors who are excited to see (…) a woman in a role like I am [in], because of all the advocacy for gender equality. (West African female fund manager)

The new wave of interest in gender lens investing among local and international LPs has so far not translated into more capital being allocated to female fund managers.

[T]hey want to support the end-businesses that are owned by women, but they don't trust that women can allocate capital to those businesses. Yeah, no, it's crazy. (South African female fund manager)

5. Discussion

5.1. Disrupting the triple dissonance

Female fund managers entering the male-dominated space of investors (LPs) and fund managers (GPs) who allocate capital largely to male entrepreneurs, experience different layers of gendered dissonance. The first layer is being a woman in the role of a fund manager, which has traditionally been held by men. The second layer of dissonance is the gender lens they add to their investment strategies, which is closely related to the dissonance of the feminine normative frame of ‘women’ and the male normative frame of ‘entrepreneurship’ (owners of investable businesses). The third layer of dissonance stems from the combination of a female fund manager, investing with a gender lens, and investing in black African entrepreneurs. This third dissonance is particularly pronounced in interactions with international investors who perceive a dissonance between ‘Africa’ and ‘investable businesses’ (especially women-led businesses) as well as in a local South African and East African context, where investments have traditionally been skewed towards white and expatriate (male) entrepreneurs.

So I found that as women - for us it's a double tragedy, you know. You are discriminated against because you are women and therefore you can't possibly do private equity well. (…). And then on top of that, you're doing it [investing with a gender lens] in Africa, you know, the dark continent. (Pan-African female fund manager)

However, the growing interest among local and international investors in gender-lens investing has not yet translated into more capital being allocated to women-led funds. Although female fund managers have reached important milestones in belonging, such as opportunities to pitch to investors, speak on panels at key industry events, and co-invest with male peers, their fundraising challenges remain largely unchanged.

Everyone is cognizant of the fact that that has to change. So everyone's kind of entertaining meetings with potential transformed or more diverse teams. But what they're battling with is to give you the money. (South African female fund manager)

But when it comes to cash, it's not there. (West African female fund manager)

5.2. Empower versus power

Our exploratory research has revealed a significant blind spot in the emerging field of gender-lens investing. Gender-lens investing has women’s empowerment at its centre, yet has a blind spot when it comes to power.

So the reason why women entrepreneurs are not being funded is because women fund managers are not being funded. Because all of the capital allocators [LPs] are men. (South African female fund manager)

While there is now a growing focus on women entrepreneurs as beneficiaries of investments, the industry is still hesitant when it comes to putting money into the hands of female fund managers and giving them the power to make investment decisions.

[T]hat's the main thing I would say – that there seems to be a lack of trust in giving the allocating power to managers who are women. (South African female fund manager)

From the capital allocators perspective, (…) there's no diversity, no transformation. So you've got people that have been working for years allocating capital to established private equity fund managers. And the same people are now being tasked with allocating capital to new and emerging fund managers, using the same type of criteria, mindset, you know, there is no change. (South African female fund manager)

So the question is: What more are we going to allow women to do in the investment industry? (East African female fund manager)

5.3. Avenues for future research

Given the scarcity of literature on female fund managers in general, and in the global South in particular, we chose an exploratory research design to discover key themes of the gendered challenges experienced by female fund managers on their fundraising journey. These novel insights advance our understanding of how such gendered challenges, in turn, shape how capital is allocated to entrepreneurs. With this paper, we have responded to calls for more research on (i) women’s entrepreneurship in the global South, (ii) the supply side of capital to investigate the persistent gender gap, as well as (iii) more qualitative and narratives-based research in the field of entrepreneurship.

Our research deliberately approaches the question of capital allocation to female fund managers and to women entrepreneurs from the perspective and lived experience of female fund managers. Future research may employ additional research methods to investigate the reasons behind the gender gap in capital allocation from institutional investors to fund managers in further depth. From an intersectional perspective, the narratives of the female fund managers in our sample reflected a high level of awareness of gender and racial bias in capital allocation to fund managers and entrepreneurs, and the desire to change this. Irrespective of race and ethnicity, female fund managers noted that the challenges in the investment industry are even greater for Black female fund managers with the exception of West Africa where race and expatriate status do not appear to play the same role as in South and East Africa. White female fund managers in South and East Africa in our sample demonstrated investment strategies with a strong and intentional focus on businesses with Black women ownership and leadership. It would be interesting to investigate from an intersectional feminist perspective whether this holds true in other markets. For example, whether white female fund managers in Brazil show the same level of awareness of racial bias and allocate more capital to Black women entrepreneurs.

With this paper, we aim to contribute to future theory building and practice of gender-lens investing. Our research offers novel, exploratory insights into what has been a blind spot in the emerging field of gender-lens investing, namely how the question of who holds power over investment decisions is closely related to the question of how the gender gap in capital allocation to entrepreneurs can be overcome.

Novel insights from this paper offer a number of avenues for future research.

Research exploring how female fund managers perform entrepreneurial belonging across the spectrum of stages along their journey

Direct research with investors making decisions on capital allocation to fund managers, including field-based or experimental studies

Studies with larger sample sizes on female fund managers in other geographies to identify cross-regional patterns for theory building

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adler, N. J. 1999. “Twenty-First-Century Leadership Reality Beyond the Myths.” Research in Global Strategic Management 7: 173–190.

- Adom, K., I. T. Asare-Yeboa, D. M. Quaye, and A. O. Ampomah. 2018. “A Critical Assessment of Work and Family Life of Female Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa: Some Fresh Evidence from Ghana.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 25 (3): 405–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2017-0063.

- Ahl, H. 2002. The Making of the Female Entrepreneur: A Discourse Analysis of Research Texts on Women’s Entrepreneurship. JIBS Dissertation Series No. 015. Jonkoping International Business School. Accessed February 2021. http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:3890/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Ahl, H. 2004. The Scientific Reproduction of Gender Inequality: A Discourse Analysis of Research Texts on Women's Entrepreneurship. Copenhagen: CBS Press.

- Ahl, H. 2006. “Why Research on Women Entrepreneurs Needs New Directions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (5): 595–621.

- Ahl, H. 2007. “A Foucauldian Framework for Discourse Analysis.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Entrepreneurship, edited by Helle Neergaard and John Parm Ulhøi, 216–250. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Ahl, H., and S. Marlow. 2012. “Exploring the Dynamics of Gender, Feminism and Entrepreneurship: Advancing Debate to Escape a Dead End?” Organization 19 (5): 543–562.

- Alsos, G. A., and E. Ljunggren. 2017. “The Role of Gender in Entrepreneur–Investor Relationships: A Signaling Theory Approach.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (4): 567–590. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.1222.

- Balachandra, L., A. R. Briggs, K. Eddleston, and C. Brush. 2013. “Pitch Like a Man: Gender Stereotypes and Entrepreneur Pitch Success.” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 33: Article 2. http://digitalknowledge.babson.edu/fer/vol33/iss8/2.

- Balachandra, L., T. Briggs, K. Eddleston, and C. Brush. 2019. “Don’t Pitch Like a Girl!: How Gender Stereotypes Influence Investor Decisions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43 (1): 116–137.

- Barber, B., A. Scherbina, and B. Schlusche. 2017. Performance Isn't Everything: Personal Characteristics and Career Outcomes of Mutual Fund Managers. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3032207 or https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3032207.

- Birkner, S. 2020. “To Belong or Not to Belong, That Is the Question?! Explorative Insights on Liminal Gender States within Women’s STEMpreneurship.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 16: 115–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-019-00605-5.

- Brashears, M. E. 2008. “Gender and Homophily: Differences in Male and Female Association in Blau Space.” Social Science Research 37 (2): 400–415.

- Brooks, A. W., L. Huang, S. W. Kearney, and F. E. Murray. 2014. “Investors Prefer Entrepreneurial Ventures Pitched by Attractive Men.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111: 4427–4431.

- Bruni, A., B. Poggio, and S. Gherardi. 2004. “Entrepreneur-Mentality, Gender and the Study of Women Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 17: 256–268. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810410538315.

- Brush, C., L. Edelman, T. Manolova, and F. Welter. 2019. “A Gendered Look at Entrepreneurship Ecosystems.” Small Business Economics 53: 393–408.

- Brush, C. G., P. G. Greene, L. Balachandra, and A. Davis. 2014. Women Entrepreneurs 2014: Bridging the gap in Venture Capital. Report Sponsored by Ernst & Young. Wellesley, MA: Babson College.

- Brush, C., P. Greene, L. Balachandra, and A. Davis. 2017. “The Gender Gap in Venture Capital- Progress, Problems, and Perspectives.” Venture Capital 20: 1–22.

- Brush, C., P. Greene, L. Balachandra, and A. Davis. 2018. “The Gender Gap in Venture Capital- Progress, Problems, and Perspectives.” Venture Capital 20 (2): 115–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2017.1349266.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Díaz-García, M., and F. Welter. 2013. “Gender Identities and Practices: Interpreting Women Entrepreneurs’ Narratives.” International Small Business Journal 31: 384–404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242611422829.

- Dy, A. M., S. Marlow, and L. Martin. 2017. “A Web of Opportunity or the Same Old Story? Women Digital Entrepreneurs and Intersectionality Theory.” Human Relations 70 (3): 286–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716650730.

- Etim, E., and C. G. Iwu. 2019. “A Descriptive Literature Review of the Continued Marginalisation of Female Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa.” International Journal of Gender Studies in Developing Societies 3 (1): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGSDS.2019.10017284.

- Gonzales Martínez, R., G. Aguilera-Lizarazu, A. Rojas-Hosse, et al. 2020. “The Interaction Effect of Gender and Ethnicity in Loan Approval: A Bayesian Estimation with Data from a Laboratory Field Experiment.” Review of Development Economics 24 (3): 726–749.

- Gunewardena, D., and A. Seck. 2020. “Heterogeneity in Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: Risk, Credit, and Migration and the Entrepreneurial Propensity of Youth and Women.” Review of Development Economics 24 (3): 713–725.

- Henry, C., L. Foss, and H. Ahl. 2016. “Gender and Entrepreneurship Research: A Review of Methodological Approaches.” International Small Business Journal 34 (3): 217–241.

- IFC (International Finance Corporation). 2019. Moving toward Gender Balance in Private Equity and Venture Capital. Washington, DC: IFC. Accessed February 2021. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/gender+at+ifc/resources/gender-balance-in-emerging-markets.

- Kanze, D., L. Huang, M. A. Conley and E. T. Higgins. 2018. “We Ask Men to Win and Women Not to Lose: Closing the Gender Gap in Startup Funding.” The Academy of Management Journal 61. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1215.

- Leitch, C., F. Welter, and C. Henry. 2018. “Women Entrepreneurs’ Financing Revisited: Taking Stock and Looking Forward: New Perspectives on Women Entrepreneurs and Finance (Special Issue).” Venture Capital 20: 103–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691066.2018.1418624.

- Lyons-Padilla, S., H. Markus, A. Monk, D. Radhakrishna, R. Shah, N. Dodson, and J. Eberhardt. 2019. “Race Influences Professional Investors’ Financial Judgments.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 17225–17230. doi:https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1822052116.

- Malmström, M., J. Johansson, and J. Wincent. 2017. “Gender Stereotypes and Venture Support Decisions: How Governmental Venture Capitalists Socially Construct Entrepreneurs’ Potential.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (5): 833–860.

- Mchunu, N., and T. Brewis. 2018. “Gender Parity in Private Equity.” Without Prejudice 18 (7): 12.

- Musk, G. C., G. H. Botha, and B. S. Neil. 2017. “Hindrances Encountered by Women Entrepreneurs in Accessing Financial Opportunities in South Africa.” African Journal of Gender and Women Studies ISSN 2 (1): 57–68.

- Nambiar, Y., M. Sutherland, and C. B. Scheepers. 2020. “The Stakeholder Ecosystem of Women Entrepreneurs in South African Townships.” Development Southern Africa 37 (1): 70–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2019.1657001.

- Riessman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Scott, J. W. 1986. “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis.” American Historical Review 91 (5): 1053–1075.

- Stead, V. 2017. “Belonging and Women Entrepreneurs: Women’s Navigation of Gendered Assumptions in Entrepreneurial Practice.” International Small Business Journal 35 (1): 61–77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615594413.

- Swail, J., and S. Marlow. 2017. “‘Embrace the Masculine; Attenuate the Feminine': Gender, Identity Work and Entrepreneurial Legitimation in the Nascent Context.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1406539.

- Turner, V. 1967. “Betwixt and between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage.” In The Forest of Symbols, edited by V. Turner, 3–19. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Yadav, V., and J. Unni. 2016. “Women Entrepreneurship: Research Review and Future Directions.” Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0055-x.