ABSTRACT

Development finance institutions (DFIs) play a major role in mobilizing private sector investments in developing countries. While there has recently been an increasing interest among DFIs in gender-lens investing, these efforts have been somewhat blind to the question of women’s unpaid work and have not yet led to a stronger investment focus on the care economy. Adopting what has been defined by other feminist scholars as a transformative approach to care, this article analyses the potential transformative effects of private sector investments in the care economy by DFIs to help build more resilient and gender-equitable economies following the global COVID-19 pandemic. The authors find there is significant potential for DFIs to approach investments with a more strategic gender- and care-lens and contribute to the recognition, reduction, redistribution, reward, and representation of care work, in line with their objective to promote sustainable socioeconomic development in developing countries.

1. Introduction

Development finance institutions (DFIs)Footnote1 play a major role in mobilizing private sector investments in developing countries. They aim to promote investments which deliver both development impact (contributing to the Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs) and a market-based return. Due to their signalling, mobilization, and standard-setting function, DFIs also play an important role in shaping private sector development in emerging markets as well as policy and practice among international investors.

DFIs generally acknowledge and accept the importance of the care economy. However, given their focus on the private sector, i.e. the paid or formal economy, the care economy – which has traditionally and continues to rely on the unpaid labour of women – never made it into the core investment thesis and the list of priority sectors DFIs invest in, with perhaps the exception of healthcare and education.

While there has recently been an increasing interest among DFIs and other private sector investors in gender-lens investing – advancing gender equality and women’s economic empowerment through private sector investments – recent efforts have been somewhat blind to the question of women’s unpaid work and have not yet led to a stronger investment focus on the care economy. Since the unpaid care economy is effectively subsidizing the paid economy DFIs rely on, we adopt a feminist perspective on both care work and the role of DFIs to suggest that a stronger focus on DFIs’ role in the care economy is needed. But what would care-focused opportunities look like exactly for DFIs and other investors in the private sector?

The relevance of this question has only become more apparent as the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 crisis on women are starting to emerge. According to the WHO (Citation2019), women represent 70 percent of health and social workers worldwide, which makes them the most exposed to the risk of contracting the virus. Outside the formal healthcare system, the amount of unpaid care work women performs also puts them at greater risk. Lockdown measures imposed across the globe have increased demand for child and elder care, and domestic work in the household (Power Citation2020), while simultaneously endangering the income of women working in hard-hit industries such as services and manufacturing. The UN has also highlighted the pandemic’s destructive effects in increasing gender-based violence, encouraging early marriage, and reducing access to family planning (UNFPA Citation2020). Without proactive and gender-responsive interventions, the negative impacts on women are likely to last for years and rollback progress made towards gender equality in recent decades (Power Citation2020).

In response to this, two groups of DFIs working on gender-lens investing – the 2X Challenge and the Gender Finance Collaborative – have called for DFIs and other investors to put women and girls at the centre of the COVID-19 response, including investing in opportunities that increase resilience to future pandemics and other shocks from a gender perspective (2X Challenge and GFC Citation2020). This paper, therefore, analyses the potential transformative effects of private sector investments in the care economy by DFIs to help build more resilient and gender-equitable economies.

2. Women, care work, and the economy

Care work can take many forms, starting with the direct care of persons, such as children, the elderly, persons with illnesses or disabilities, and others. This type of care refers not only to ensuring that the physical or safety needs of the recipient are met, but their emotional and cognitive needs as well (Chopra and Sweetman Citation2014). Care work also encompasses activities which do not entail face-to-face personal care, such as cleaning, cooking, laundry, fetching water and fuel, and other household maintenance tasks (also referred to as ‘domestic work’), which nevertheless provide the preconditions for personal caregiving (Razavi Citation2007; Folbre Citation2018; Chopra et al. Citation2020).

The performance of care work can take the form of unpaid services in the family or community, or paid work in the marketplace (Folbre Citation2014, Citation2018). Whether paid or unpaid, care activities create ‘value’ and can therefore be considered productive or economic. Yet only paid activities are included in standard measurements of the size of the economy. The ‘care economy’ refers to the value of both paid and unpaid care work (Chopra and Sweetman Citation2014; Folbre Citation2018).

Care work is typically invisible and undervalued in standard economic and development thinking. This phenomenon has its root in gendered division of labour (Folbre Citation2018). Because the term ‘care’ carries a dual meaning – taking care of and being emotionally invested in something – patriarchal gender norms suggest women are better suited for these tasks, partly because of their biological roles as mothers, but also because of traditional associations of the ‘feminine’ with the emotional. Because these tasks are considered ‘natural’ to women, together with women’s lower status in most societies, care activities have traditionally not been considered proper ‘work’ in the same way as male-dominated activities, and have therefore not been remunerated (or valued) at the same level, when remunerated at all.

This gender division of labour has profound implications for women and girls. For many women across the world, caring is a social obligation which absorbs time and energy and perpetuates their subordination by limiting their ability to play other economic, social, and political roles (Chopra and Sweetman Citation2014; Folbre Citation2018). Women around the world continue to shoulder the largest share of unpaid care work, more than three times as much as men on average (ILO Citation2018). The time poverty that ensues is a major barrier to gender equality and women’s empowerment and infringes upon women’s human rights. Data derived from time-use surveys and labour force statistics suggest that the more time women spend on unpaid care activities, the less likely they are to be engaged in paid employment; and those who are active in the labour market are more likely to be limited to part-time or informal employment, and earn less than men (OECD Citation2014).

This also manifests itself in the formal labour market in the form of occupational segregation, i.e. the concentration of men and women in certain roles and occupations based on gender norms (Seguino Citation2020). Recent scholarship finds that occupational and sectoral segregation by gender is surprisingly persistent, even increasing, in developing countries in particular (Borrowman and Klasen Citation2020). Furthermore, research on care work within the paid economy has shown that categories of occupations where women tend to be concentrated (such as nurses, midwives, personal care workers, and cleaners) are characterized by low job quality, including low wages and poor working conditions (ILO Citation2018).

Another factor fuelling the invisibility and undervaluation of care work is the longstanding distinction in political, economic, and legal thought between the private and the public spheres. The public sphere corresponds to the workplace, the marketplace, and the government, for example, while the private sphere is associated with the home and the family. The former, dominated by men, is a space where groups with power can use their influence and resources to shape public policy (Folbre Citation2014). The latter, associated with women and the family, remains where most of the care work, either unpaid or informal, is carried out, and therefore escapes traditional economic measurements and valuation. This distinction allows the state, employers, and other actors (including financial and development institutions) to ignore the care economy, its contribution to both human and economic development, and its negative impacts on women and girls (Chopra and Sweetman Citation2014).

Yet, without the care that is provided in the domestic sphere, the formal economy could not be sustained. Unpaid care work enables the productive economy to function, because it cares for both the existing and future workforce (Chopra and Sweetman Citation2014). If measured and included, unpaid care work would constitute 40 percent of Swiss GDP, and would be equivalent to 63 percent of Indian GDP (OECD Citation2014). However, providing care is not without cost. The costs of providing care, which fall disproportionately on women, include sacrificed opportunities in education, employment and earnings, political participation, and leisure (Esquivel Citation2014).

Unpaid care work and the amount one needs to perform also has an intersectional dimension. Research suggests that the burden of care is most profound for women living in poverty, who are unable to lessen the care load by investing in labour-saving technologies, paying for services from the private sector, or employing household help (Chopra and Sweetman Citation2014; Folbre Citation2018). In many countries across the globe the dynamics of care work intersects with issues of class (Staab and Gerhard Citation2011), age, race, ethnicity, caste (Krishnan Citation2020), and migration (Razavi Citation2007; Song and Dong Citation2018).

Scholars in the fields of gender and development and feminist economics have emphasized that investments into employment opportunities for women in the paid economy must go hand-in-hand with investments into the care economy to reduce and redistribute women’s unpaid labour. Otherwise, initiatives that promote women’s employment may either fall short of their goal or reduce women’s well-being by increasing their workload (Moser Citation1989; Chant Citation2008; Seguino Citation2020).

Field studies have shown that a lack of infrastructure and access to vital services increases drudgery of care and exacerbates women’s time poverty. This, in turn, hampers women’s participation in the paid economy and is an important driver of the depletion of women’s time and energy (Chopra and Zambelli Citation2017). Investments in water supply and sanitation, energy access, and gender-responsive transportation are therefore crucial to reduce women’s unpaid care work. At the same time, greater investments into affordable and quality direct care infrastructure, especially for child care (Agénor and Madina Citation2014; Clark et al. Citation2019; Nandi et al. Citation2020) and elder care (Heger and Korfhage Citation2020), are important to promote women’s labour force participation.

Particularly relevant for DFIs, there is also another important dimension to investments into the care economy related to direct job creation, beyond the indirect employment effects of freeing up women’s time for labour force participation (Warner and Liu Citation2006). Ilkkaracan, Kim, and Kaya (Citation2015) explored the potential employment effects of a 20 billion Turkish lira investment into housing (the construction sector) versus childcare centres and preschools in Turkey. They estimate that the same investment size would translate into 290,000 new jobs in the construction sector (6 percent thereof would go to women) versus 719,000 new jobs generated by investing on childcare centres and preschools (73 percent thereof would go to women). Indeed, Seguino’s (2020) recent review of existing research suggests that social infrastructure spending tends to have a larger job multiplier effect as well as a greater effect on closing gender employment gaps.

3. Defining a feminist approach to the care economy

Our approach follows what has been defined by other feminist authors as a transformative approach to care. As summarized by Valeria Esquivel (Citation2014, 434), ‘a transformative approach to care means radically changing care provision (and possibly, care benefits’ accrual) by recognising, reducing, and redistributing care: The Triple R Framework’. The ILO (Citation2018) later added reward and representation to this conceptual framework, turning it into the ‘5R Framework’.

From a feminist perspective, a careful balance must be struck between the need to focus analyses and interventions aimed at reducing the care burden on women (as the primary caregivers globally), while challenging the notion that this work is intrinsically ‘female’ (Esquivel Citation2014).

As laid out by Chopra and Sweetman (Citation2014, 418), ‘changing historical contexts and big shifts such as demographic changes and the current food and financial crises provide an opportunity to make care more visible’. Between the recurring imagery comparing care workers to ‘frontline workers’ in the fight against the coronavirus, and the lockdown measures imposed across the world, which have in many cases increased the care workload for families (Power Citation2020), it is possible to say that the COVID-19 pandemic, and ensuing health and economic crisis, have made care visible. The time is therefore ripe to re-examine the relationships among the care economy, development actors, and the private sector to build more resilient and gender-equitable economies and societies.

4. Key research questions and methodology

This article adopts a feminist perspective to identify opportunities for transformation in the private sector in developing countries, which emerge from the current COVID-19 crisis, in particular:

What are the early experiences of DFIs with gender lens investment strategies in relation to investments in the paid care economy in developing countries?Footnote2 What lessons can be drawn from these experiences in order to scale up DFIs’ engagement in the care economy?

What is currently holding DFIs and private sector investors back from investing in the care economy, and how can these challenges best be tackled?

What opportunities are there for private sector gender-lens investments by DFIs that increase resilience to future pandemics related to the 5R Framework?

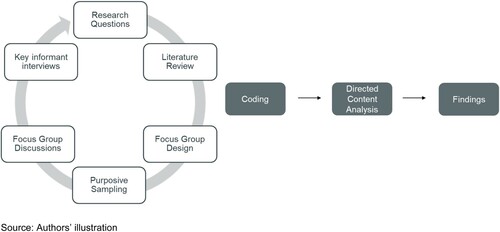

The findings are based on a literature review of feminist approaches to the care economy, as well as two focus-group discussions with representatives from 11 bilateral and multilateral DFIs and semi-structured interviews with two multilateral DFIs in May 2020 (for a total of 13 institutions).

Given the scarcity of extant research on the role of DFIs and the care economy, we chose a qualitative research design for the primary research to gain novel, exploratory insights into current and planned investment practices of DFIs related to the care economy, key challenges, and barriers as well as opportunities for a greater focus of gender-lens investments on the care economy. Focus group discussions are a suitable research method to gain an in-depth understanding of a certain issue (Gundumogula Citation2020). Consistent with the aim of this method, we conducted purposive sampling and selected subject matter experts as focus group participants among the bilateral DFIs most actively engaged in gender-lens investing and who, based on their position within the organization, are at the intersection of gender expertise, corporate strategy, and investment practice and have a comprehensive understanding of their DFI’s strategy and practice.

The overall landscape of bilateral DFIs consists of 14 European DFIs as well as the DFIs of USA, Canada, and Japan. In addition, there are seven multilateral DFIs. As the care economy has not traditionally been a focus of development finance and has only recently received greater attention in the context of gender-lens investing, the sampling method prioritized those DFIs most active in gender-lens investing who, among all DFIs, are most likely to have engaged with the care economy. This research thus focuses on DFIs who have gender-lens investing strategies in place.

This purposive sampling method led to a total of 14 focus group participants representing 11 DFIs (including eight bilateral European, two bilateral North American DFIs and one multilateral DFI). This selected sample accounts for a significant proportion of bilateral DFIs currently investing with a gender lens in emerging markets as well as the first multilateral DFI to join the 2X Challenge, with collectively approximately USD 359 billion assets under management (AUM). The discussions, which were conducted in a semi-formal setting, were designed around the three research questions above.

This research was complemented by conducting semi-structured interviews with representatives from two multilateral DFIs (IFC and EBRD, together approximately USD 142 billion AUM) that have done and published significant work and research on the issue.Footnote3 For the data quality of focus group discussions, it is important to have an adequate number of participants who feel comfortable discussing key issues as a group. As the two multilateral DFIs were significantly more advanced in their engagement with the care economy, we chose to interview them individually rather than including them in the focus group discussions, which might have made DFIs with less experience more hesitant to openly share challenges.

All focus group discussions and key informant interviews took about 60 minutes each, were carried out by videoconference due to the travel and meeting restrictions caused by the global COVID-19 pandemic and were recorded.

We used directed content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005) for the analysis of data obtained from focus group discussions and key informant interviews. Directed content analysis takes theory as a starting point (in this case the 5R framework) and codes are defined both before and during data analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005) ().

5. Findings on DFIs and the care economy

DFIs occupy the space between public aid and pure private sector investments. Their existence is based on the belief that the private sector, too, can contribute to socioeconomic development (including, but not limited to, economic growth, job creation, and poverty alleviation) in developing countries.

Bilateral DFIs are majority-owned by their national government and are expected to invest their own capital on a commercially viable basis. Some DFIs have access to traditional development assistance funds and are able to offer grant money or concessional capital to riskier, earlier-stage companies. However, the core focus of DFIs remains on investments in more mature and profitable companies in agriculture, manufacturing, and industry, as well as infrastructure and renewable energy projects, and financial institutions. Due to their unique mandate, DFIs face the challenge of balancing commercial success with development impact. Unlike multilateral DFIs, several bilateral DFIs must adhere to banking regulations in their home jurisdictions, which can make it difficult to balance risk management requirements with development outcomes (Savoy, Carter, and Lemma Citation2016).

Focus group discussions confirmed that, until recently, DFIs’ investments had been largely gender-blind beyond an environmental and social (E&S) risk analysis. The past few years have, however, seen the rise of women’s economic empowerment and gender-lens investing as an area of focus for DFIs (Lee, O’Donnell, and Ross Citation2020). This research uncovered various ways in which some DFIs were already recognizing, reducing, and redistributing care through a few of their investments, either by providing support for employees to reconcile care responsibilities with paid work, or investing directly in the formal care economy or in sectors with transformative potential from a care perspective. Key findings from these experiences (including lessons learned, challenges, and possible solutions, where relevant) are described in the rest of this section.Footnote4

5.1. Enabling workplace policies and practices

5.1.1 Early experiences of DFIs

DFIs invest in private companies from a range of sectors, to which they will often provide non-financial advice and support in addition to their investment. There is therefore a significant opportunity to foster workplace environments which promote gender equality both in the sphere of paid and unpaid work. Good practices DFIs can promote among their investee companies include paid parental leave (Heymann et al. Citation2017),Footnote5 flexible working arrangements (including staggered start time, job sharing, home office, part-time), childcare and other care-related services as well as pay equity, safe transportation, gender bias training, and progressive advertising challenging gendered stereotypes around care work. We call these enabling workplace policies and practices.

This research revealed that several DFIs offer technical assistance (TA)Footnote6 to their investees for both an initial company-level diagnostic on the potential win-win outcomes of enabling workplace policies and practices, as well as for the actual implementation of such policies and practices. These include support for a company’s own on-site childcare facility, establishing childcare centres between multiple employers, partnerships with third-party childcare providers, and childcare vouchers or subsidies. However, in practice, focus group participants confirmed that this is often not proactively offered and only available if companies ask for it. The presence of champions – both within DFIs and investee companies – who drive change in this area was identified in focus group discussions as an important factor in determining whether care-related TA would be offered or not. This strategy was intentionally used by some research participants in the hope to further build the case for other investee companies to follow suit: ‘We have been cherry-picking and taking the ‘easier’ ones. Hopefully we can use these cases for other companies where the discussion is a bit harder and where we need more data and other convincing elements to get them on board’.

Another finding was that some DFIs play a role by bringing companies together for peer-learning and collaboration. For example, in Pakistan, a multilateral DFI launched an initiative that brought together multiple companies to make a joint commitment to and collaborate on employer-supported childcare. It is worth noting that bilateral DFIs have spearheaded similar initiatives in the past to promote collaboration and peer-learning around E&S risk management. In countries like Sri Lanka, Kenya, and Paraguay, DFI-supported sector initiatives have brought together key stakeholders of the local banking sector to jointly develop E&S standards all members of the initiative commit to, and to engage in regular peer learning during the practical implementation phase. This experience could be leveraged to tackle challenges related to the care economy in different geographies, enabling peer-learning and context-specific solutions, such as voluntary standards of enabling workplace policies and practices or joint childcare facilities sponsored by several employers.

5.1.2 Key lessons learned on enabling workplace policies and practices

As promoting enabling workplace policies and practices among investee companies appears to be the area where DFIs have the most experience in relation to the care economy, this research and analysis of the literature enabled us to identify several key lessons learned, including:

− Understanding the business case is crucial for companies to adopt a proactive approach to childcare and other enabling workplace policies and practices, beyond minimum compliance with national laws or E&S standards. While many companies might recognize the benefits, in terms of women’s workforce participation, reduced absenteeism, productivity gains, and loyalty, in practice significant change has proven to be more likely when context-specific research on these benefits is available. As one of the focus group participants put it: ‘When we are able to make the financial case [for care interventions], it makes it easier to convince investment officers that these are worthwhile investments’. This has led the International Finance Corporation (IFC) to conduct extensive research on the business case for employer-supported childcare and other enabling workplace policies and practices by country and sector, in addition to research on policy frameworks, and care-related demand and supply through its Tackling Childcare Initiative (IFC Citation2019).

− National laws and policies matter. Care policy frameworks around the world are changing and fuel the demand for market-based models of care. In 26 out of 189 economies covered by World Bank research on business, women and the law, private sector employers are legally required to provide childcare to their employeesFootnote7 (World Bank Group Citation2019). Where laws such as these are in place, it becomes easier for DFIs to have a conversation with their investees about the care needs and obligations of their employees, and why it matters to them as an employer.

− Enabling policies and practices should be aimed at both women and men. As scholars in the fields of feminist economics, and gender and development (GAD) have long argued, initiatives targeting women in their roles as mother and carers carry the risk of reinforcing stereotypes and essentializing women as ‘natural’ carers. Such an approach will likely fail to challenge existing inequalities and not lead to a redistribution of unpaid care work from women to men. This aspect was also highlighted in focus group discussions. Employer-supported care should therefore be offered to female and male employees equally. Employers also have a role to play in transforming gender norms by encouraging men’s take up of parental leave and unpaid care work more broadly. This is consistent with research by Oxfam (Citation2018) suggesting that, for change to take place, the perception men have of other people’s approval is more important than their own willingness to engage in care work.

− Fuelling the demand for care services and providers has ripple effects. By incentivizing and supporting their investee companies to offer care-related support to their workforce, DFIs can play an active role in stimulating demand for the market provision of care, indirectly supporting companies they might not otherwise be able to invest in, as explained in Section 5.2.

5.2. Direct investments in the care economy

5.2.1 Early experiences of DFIs

Beyond investments in the healthcare and education sectors, DFIs’ investments in the formal care sector have been limited. Some multilateral DFIs have invested in private sector providers of childcare, elder, and disability care in Europe, but such investments in developing countries have been scarce. Still, this research uncovered a few examples. Some bilateral DFIs with access to concessional funds have supported local care providers, although in a limited number of cases. One DFI provided grants to co-finance the development of vocational training programs for elder care models in the Philippines and China, piloted by European companies in collaboration with local educational institutes, analogously to European elder care quality standards.

Other DFIs have made investments in innovative care providers through private equity funds. Among these care providers is a company which operates a chain of premium day-care centres in residential areas and corporate locations in India, as well as a company providing in-home healthcare services, including nursing, physiotherapy, maternal healthcare, vaccination, and elderly care across sixteen cities across India. The company regularly engages with male employees with trainings about the importance of gender equality and to challenge gendered stereotypes (ICRW Citationn.d.).

5.2.2. Challenges

The lack of reliable information about investment opportunities in the care economy emerged in focus group discussions as the biggest obstacle to greater DFI involvement in this space. Consistent with DFI experience, recent OECD (Citation2019) research shows that limited information is available on both the availability and quality of market provision of care in developing countries. However, there is a general perception that market-based care solutions are increasingly emerging. The current care infrastructure in emerging markets was described by one focus group participant as ‘fragmented’, with smaller companies often operating in a single location. This participant, an investment officer, also added: ‘I think [the main issue] is the lack of opportunities and bankable entities – for now’. Research participants emphasized that data on the financing needs of care providers in developing countries are scarce. Reliable data on the various actors involved in the public and private sector provision of care emerged as a priority need for DFIs and their partners. More and better data on the size of the business opportunity could significantly accelerate DFI involvement in this sector. One focus group participant quoted an investment officer saying: ‘Go find me companies and we’ll invest in them’.

5.2.3 Possible solutions

Collaboration between different actors and investors could create additional direct investment opportunities in the care economy. Since the market-based care infrastructure in developing countries appears to be fragmented and small in scale, the typical minimum investment size of DFIs in the range of USD 5–10 million (sometimes higher) appears to be too large to absorb for many local care providers. This concern was highlighted by one of the focus group participants, whose institution had already made investments in the (public and private sector) care economy in a developed market but was hesitant to do the same in its emerging markets portfolio: ‘The care economy in the EU is already developed, there are promoters that are quite strong and ready to take on the ticket sizes we provide, which (…) we find more challenging outside the EU’. This challenge has led both multilateral DFIs to explore a partnership model with municipalities in order to finance smaller local care providers. While this seems to be an interesting approach to ensure local ownership, quality of service, and scalability, it is not a model that bilateral DFIs could replicate, given their mandate to focus exclusively on private-sector investees. A similar model could be adopted by DFIs that make significant investments in local financial institutions for the purpose of on-lending to small and medium businesses (SMEs). DFIs could incentivize their financial institution partners to use DFI funding for on-lending to local care providers and provide technical assistance to help such care providers enhance key aspects like the quality, sustainability, and accessibility of care.

Another avenue that emerged from interviews and focus groups is for DFIs to support established, international providers of care interested in expanding to new markets. This could be a relevant investment opportunity, considering growing political demands and promotional funding programs for bilateral DFIs to support European and US companies that invest in developing countries. However, such an approach would require careful consideration to ensure this does not jeopardize development impact, exemplified by the risk that international players may acquire local businesses and revenues may not stay in the country.

Finally, combining different types of capital could unlock better financing of private sector care solutions. Care providers have not traditionally been among the primary groups targeted by financial institutions and may struggle to access finance due to a perceived higher risk, such as lower profitability and lack of collateral, or lack of a track record, especially as early-stage companies emerge. This current state of play makes a strong case for innovative partnerships combining different types of capital. Grants and concessional capital can help incubate local care providers, and offer riskier and patient seed and start-up financing, helped by incubators, angel investors, and donor-funded programs. Some DFIs have the possibility of offering venture capital or upscaling programs for early-stage companies. Financial intermediaries – including local financial institutions and funds offering early-stage and growth equity capital as well as a range of credit products – can play an important role in the early growth phase. As care providers become more established and reach scale, DFIs can offer different financing instruments and technical assistance to take them to the next level. This may include helping successful care providers develop franchize models and enhance standards in terms of quality of service, decent jobs for care workers, and affordability of services for different socioeconomic groups.

5.3. Direct investments in sectors with transformative potential for the care economy

As mentioned in Section 2, unpaid care work is closely linked to the issue of time poverty, which is itself a major barrier to gender equality and women’s empowerment. Research suggests that investments in infrastructure, energy as well as time- and labour-saving devices, when designed with a strong gender-lens, can play an important role in reducing and redistributing unpaid care work, and ultimately promoting women’s economic empowerment (OECD Citation2019). For example, the International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that clean cooking would save over 100 billion hours of women’s time collecting fuelwood per year, which would free up time equivalent to a workforce of 80 million people, in addition to preventing 1.8 million premature deaths per year thanks to the reduction in air pollution (IEA Citation2017, OECD Citation2019). Furthermore, data on 25 countries in sub-Saharan Africa (representing 48 percent of the region’s population) shows that women collectively spend at least 15 million hours each day on fetching water alone (Fontana and Elson Citation2014). There is also interesting evidence that men become more involved in unpaid care work when time- and labour-saving technology is available, suggesting potential for the redistribution of unpaid care work (OECD Citation2019).

5.3.1 Early experiences of DFIs

Interestingly, DFIs have traditionally had a strong investment focus on the infrastructure and energy sectors. Yet, despite many studies demonstrating the relevance of these sectors for gender equality outcomes, focus groups and interviews confirmed these are precisely the sectors where many DFIs assume there is least potential for a gender-lens.

This research and literature review uncovered a few examples of DFIs incorporating a gender and care lens to their infrastructure investments. For example, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has been leading the gender-lens investing work in the infrastructure and energy sectors with an explicit focus on women’s time poverty due to unpaid care work (ADB Citation2015). Another emerging example is the gender-lens investing approach of the Private Infrastructure Development Group (PIDG), an infrastructure development and finance organization operating in the poorest and most fragile countries.Footnote8 PIDG recently adopted a Gender Ambition Framework created by gender planning and development expert Caroline Moser.

Regarding investments in time- and labour-saving technologies, an interesting example is an investment of two bilateral DFIs in a pay-as-you-go solar energy company in Kenya. The company launched a pay-as-you-go solar fridge product with the explicit aim of providing affordable cost- and time-saving technology with a gender-lens to millions of households. The company intentionally engaged both male and female consumers equally throughout the product development and user testing phase. Time-saving potential is estimated at two hours per week per household, accruing primarily to women (CDC Citation2019).

5.3.2 Challenges

Despite the potential of investments in sectors such as infrastructure and time- and labour-saving devices to reduce the amount of unpaid care work done by women, there is however no guarantee that this potential will be realized, which makes applying a strong gender-lens in both project design and implementation crucial. Gender-blind investments in infrastructure may even exacerbate the unequal distribution of unpaid care work and further entrench gender inequalities. In fact, the World Bank (Citation2010) has highlighted the lack of social and gender analysis in infrastructure projects as one of the five key challenges to reducing gender inequalities.Footnote9

This research also finds that DFIs rarely consider time-use data in their investment approaches, which limits their understanding of gender and care issues surrounding their investments. Interviews and focus group discussions revealed that some DFIs are currently exploring how to consider gender-disaggregated time-use data in the project design phase, and for monitoring and measuring development impact. However, research participants highlighted the fact that collecting this type of information also comes with its own challenges: ‘We are battling with the question: how do we do this without putting a heavy burden on clients? What do we do when this information is not readily available?’.

Another key challenge revealed in focus-group discussions is that DFIs usually come on board as investors in infrastructure projects at a later stage of the project’s life cycle, which limits their influence on early project design. Speaking of the potential time savings for women if their travel patterns (which are influenced by their care obligations) were taken into account in the design of transport projects, one focus group participant observed that

if a lot of the planning has already been done by the time we come in with our financing (…) it’s really difficult to make those changes. When we come in as in investor really affects how much we can influence those ‘hard’ infrastructure systems.

6. Opportunities for future involvement in the care economy by DFIs and other investors along the 5R framework

This research revealed that COVID-19 is provoking a change of perspective on the relationship between the private sector and society, to which DFIs and other private sector actors can contribute. There is a growing expectation that companies have a duty to provide a range of care economy support to their workforce and potentially even to the communities in which they operate. This will likely lead to increased demand for care service providers and encourage the emergence of innovative care-related business models that require financing.

In line with an approach focusing on a transformative approach to care using the 5R Framework, key opportunities for future involvement in the care economy by DFIs and other investors include ():

Table 1. Opportunities for future involvement in the care economy by DFIs and other investors along the 5R framework.

6.1. Recognize

An essential first step is for DFIs to better recognize care in their interventions. This starts with improving data collection and analysis of care-related indicators, such as time-use data. The same principle should be applied to technical assistance interventions supporting investees implementing care-enabling policies and practices, which should further contribute to building and disseminating the business case for such provisions.

Greater recognition of care should also help DFIs better understand and measure the impact of their investments on caregivers in developing countries, especially women. What can be considered ‘positive’ impacts for women’s economic empowerment (e.g. job creation, greater access to leadership, and entrepreneurship opportunities) can sometimes result in additional stress and exhaustion for women and girls, compromising the quality of care, and decreasing their well-being and sense of empowerment at the same time.

This ‘R’ is also about DFIs recognizing the business and economic opportunities presented by the care economy. According to the ILO (Citation2018), more than 600 million women remain outside the labour force because of their unpaid care responsibilities, representing 42 percent of all women not active in the labour market, and doubling investment in the paid care economy would result in nearly 270 million new jobs by 2030.

To further explore the potential role of DFIs and private sector investments in the care economy, a detailed market mapping is essential. This includes analysing disaggregated data on private sector care providers (such as size, coverage, business model, quality, and commercial viability), their particular financing needs (including amounts, type of capital, tenor) as well as local regulatory frameworks. Further research on the context-specific demand and local preferences for different models of care would also provide DFIs with important insights.

6.2. Reduce

Care being an integral and essential part of human life, it is unrealistic to expect it can be entirely eliminated – nor would this be desirable, since certain tasks might produce joy for both caregivers and care recipients (Chopra et al. Citation2020). Rather, the objective is to reduce the amount of time and effort dedicated to these tasks, to limit the toll (e.g. in terms physical effort and time povertyFootnote10) they exert on women and girls. DFIs can contribute to the reduction of the care burden by investing in time- and labour-saving technologies and infrastructures, including (but not limited to): clean energy, water and sanitation, safe and efficient transport, and the production and distribution of time-saving devices and technologies. This calls for care considerations and gender analysis to be intentionally incorporated in the design, implementation and evaluation of these investments, as evidence suggests that the mere fact of financing such projects does not in itself lead to positive outcomes for women and other caregivers (World Bank Citation2010).

6.3. Redistribute

DFIs seem well positioned to make a positive contribution to the redistribution of care work from households to the marketplace. DFIs can engage with the state through policy dialogue and collaboration. More importantly, DFIs can help redistribute certain care obligations to the private sector by promoting both demand (through encouraging their investees to offer care support solutions to their employees) and supply (through direct investments in care providers or through financial intermediaries) for market-based care solutions.

Finally, DFIs can also indirectly contribute to the redistribution of care work by encouraging changes in gender norms around the provision of care, so care responsibilities are shared equally between women and men. This can be done by ensuring that care-friendly measures implemented by investees are offered to both men and women employees, or by challenging stereotypes about care occupations being women’s jobs through the promotion of equal opportunity and workplace diversity initiatives with their investees.

6.4. Reward

As mentioned above, jobs in the paid care economy – especially those carried out by women – are characterized by low pay and poor working conditions. DFIs with investments in paid care sectors should be working with investees to ensure the work of care workers is valued and therefore rewarded (i.e. paid) appropriately.

DFIs can also ‘reward’ care work by providing incentives to investees that implement care-related improvements. DFIs have a strong signalling role and can stimulate the supply of innovative care solutions by making their interest in long-term investments in the care economy explicit. This signalling can encourage local entrepreneurs to establish news models of care. Importantly, angel investors, and other early-stage investors are also more likely to support emerging care providers in the start-up phase when they have the confidence that DFIs are there to ensure the following rounds of financing as these companies grow.

6.5. Representation

Finally, when it comes to promoting the effective representation of care work and care workers through their operations, DFIs should, at a minimum, ensure that investee companies comply with ILO Conventions on freedom of association and collective bargaining. They should also use their convening and signalling power to ensure women and care workers are meaningfully represented in decision-making around care work within their own institutions (for example, when developing their investment strategy for the care economy or when designing TA projects with a care economy component) as well as in the various organizations and initiatives they participate in.

7. Conclusion

This research shows that there are several opportunities for DFIs to contribute to building more resilient and gender-equitable economies via the care economy. It is encouraging to know that some DFIs already contribute (albeit sometimes indirectly or unknowingly) to this vital sector of human activity, particularly by promoting care- and gender-related interventions with their investees and by investing in sectors with transformative potential for the care economy. This suggests the existence of several leverage points within their current policies, tools, and processes which could be used to achieve ‘quick wins’ on the recognition, reduction, redistribution, rewarding, and representation of care work globally. Such ‘quick wins’ include technical assistance programmes, existing presence in the infrastructure and energy sectors, and market signalling.

The findings also show that, for DFIs to have a transformational impact, a much more deliberate and intentional approach is needed. Improved data collection and analysis on care-related metrics and indicators represents an essential starting point to gain a better understanding of key gaps and of the impact of care-related investments. More importantly, direct investments in the care economy by DFIs can only be enabled by first conducting an extensive market mapping of care providers and the economic opportunity they represent in emerging markets, which itself requires DFIs to approach their business development and deal origination process with a gender lens. DFIs that want to lead in this space should consider building their internal capacity and expertise about the care economy, similar to the sectoral expertise many of them have built over the years in areas such as infrastructure, healthcare, agriculture, and financial services.

As to what exactly should be the role of DFIs in the care economy vis-à-vis that of the public sector, there was consensus among focus group participants and interviewees that there is and should be a role for DFIs to play in this sector. This feeling was supported by the fact that DFIs (some more than others) already contribute in some way to a transformative approach to care. As the paid economy could not thrive without the care economy, the private sector should play a more active role in providing solutions along the 5R framework. However, several participants expressed a certain reticence towards increasing the role of the private sector in care provision, citing the criticism certain multilateral DFIs received for their investments in early childhood education, for example. The role DFIs should play in ensuring the quality of the care provided was identified as a key challenge and a potential barrier to greater investments in the sector. As one focus group participant noted, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed tremendous gaps in elder care provision in Europe and North America, illustrating the potentially severe human rights risks that can arise when the quality of care is not properly ensured. Public-private partnership models (such as collaboration between private companies and local municipalities) represent an interesting alternative that would deserve further exploration.

This research is based on focus group discussions and key informant interviews with 13 bilateral and multilateral DFIs conducted in May 2020. While this sample reflects the perspectives and early experiences of DFIs most active in gender-lens investing, their experiences point to relevant insights and lessons for the wider DFI community. The findings advance the understanding and practice of gender-lens investing on a timely theme – the care economy – whose importance has been highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic and is reinforced as the world economy prepares for recovery. Given nascency of DFIs’ engagement in the care economy and the rapidly evolving field of gender-lens investing, these research findings are limited to a certain point in time at the beginning of the pandemic and there is an opportunity to explore these research questions further with research studying trends and changes over time (throughout the pandemic and in the recovery).

Four key areas for future research emerge from this paper:

What does the market opportunity for private sector care provision (including local models and providers, funding needs, size of the demand, local regulatory framework) look like in emerging markets? Has the landscape changed because of the COVID-19 crisis? How do these relate to national development objectives and public policies? A country-by-country approach would be needed. Academic researchers might want to consider partnering with a DFI to work together on certain geographies.

How do local norms, patterns, and preferences around care influence the demand and supply of care provision in emerging markets? Has COVID-19 had an impact? Like the previous question, a country-by-country approach would likely be needed.

Building on the work already done by multilateral DFIs such as the IFC and the EBRD, how can we better disseminate the business case for employer-supported care support to those it needs to reach, i.e. employers and investors? How can DFIs help investees in this area, and how can they best measure the success of their interventions?

What alternative or hybrid (e.g. public-private) care provision models exist that have the potential to be replicated in other countries? Could certain models increase the accessibility of care for underserved or excluded groups, such as women living in low-income areas?

Disclosure statement

All personal information that would allow the identification of any person or person (s) described in the article has been removed. This excludes any information obtained through publicly-available information.

Notes

1 DFIs are specialised development banks with the mandate to support private sector development in developing countries by providing long-term investment capital in form of debt, equity, mezzanine and/or guarantees to profitable companies in developing countries. Bilateral DFIs are either independent institutions or part of larger bilateral development banks. Multilateral DFIs are private-sector arms of international financial institutions (IFIs).

2 Given that the vast majority of literature and case studies on the role of DFIs in the care economy have focused on childcare, this article primarily uses childcare examples.

3 IFC’s Tackling Childcare Initiative has a global focus while EBRD’s initiative initially focused on Turkey and then looked at scaling and replicating good practices in other countries.

4 While the focus of this paper is on DFI investments in developing economies, we have included examples from developed economies, insofar as they could provide relevant insights or learnings. This does not imply that care needs are the same in developing and developed markets.

5 Globally, only around 40 percent of women in employment are covered by maternity protection, and 830 million women do not have adequate maternity protection (ILO Citation2018 cited in OECD Citation2019)

6 Technical assistance (TA) can be defined as the transfer, adaptation, mobilisation, and use of services, skills, knowledge, technology, and engineering for developmental purposes (World Bank Citation1996).

7 It is, however, problematic that 70 percent (18 economies) of these 26 countries link this requirement to the number of female employees, which can disincentivise employers to hire women.

8 PIDG is owned and funded by the governments of the UK, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Australia, Sweden, and Germany (in some cases via their national development banks), and the IFC.

9 This aspect is also illustrated by the DAC gender equality policy-marker: less than 1 percent (equivalent to as little as USD 15 million) of aid to the energy sector targets gender equality as a principal objective over the period 2016–2017 (OECD Citation2019).

10 See Section 2.

References

- 2X Challenge. 2020. “2X Challenge and Gender Finance Collaborative Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Accessed February 2021. https://www.2xchallenge.org/press-news/2020/04/07/2x-challenge-and-gender-finance-collaborative-response-to-covid19-pandemic.

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2015. Balancing the Burden? Desk Review of Women’s Time Poverty and Infrastructure in Asia and the Pacific. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

- Agénor, Pierre-Richard, and Agénor Madina. 2014. “Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Development.” Journal of Economics 113: 1–30.

- Borrowman, Mary, and Stephan Klasen. 2020. “Drivers of Gendered Sectoral and Occupational Segregation in Developing Countries.” Feminist Economics. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1649708.

- CDC Group. 2019. How Innovation in Off-Grid Refrigeration Impacts Lives in Kenya. Accessed February 2021. https://assets.cdcgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/29165356/How-innovation-in-off-grid-refrigeration-impacts-lives-in-Kenya.pdf.

- Chant, Sylvia. 2008. “The ‘Feminisation of Poverty’ and the ‘Feminisation’ of Anti-Poverty Programmes: Room for Revision?” Journal of Development Studies 44 (2): 153–186.

- Chopra, D., A. Saha, S. Nazneen, and M. Krishnan. 2020. Are Women Not ‘Working’? Interactions Between Childcare and Women’s Economic Engagement, IDS Working Paper 533. Brighton: IDS.

- Chopra, Deepta, and Caroline Sweetman. 2014. “Introduction to Gender, Development and Care.” Gender & Development 22 (3): 409–421.

- Chopra, Deepta, and Elena Zambelli. 2017. No Time to Rest: Women’s Lived Experiences of Balancing Paid Work and Unpaid Care Work. Global Synthesis Report for Women’s Economic Empowerment Policy and Programming. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

- Clark, S., C. W. Kabiru, S. Laszlo, S. Muthuri. 2019. “The Impact of Childcare on Poor Urban Women’s Economic Empowerment in Africa.” Demography 56: 1247–1272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00793-3.

- Esquivel, Valeria. 2014. “What is a Transformative Approach to Care, and Why do we Need it?.” Gender & Development 22 (3): 423–439.

- Folbre, Nancy. 2014. Who Cares? A Feminist Critique of the Care Economy. New York: Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. Accessed February 2021. http://www.rosalux-nyc.org/a-feminist-critique-of-the-care-economy/.

- Folbre, N. 2018. Developing Care: Recent Research on the Care Economy and Economic Development. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre. Accessed February 2021. https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/handle/10625/57142.

- Fontana, Marzia, and Diane Elson. 2014. “Public Policies on Water Provision and Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC): Do They Reduce and Redistribute Unpaid Work?.” Gender & Development 22 (3): 459–474.

- Gundumogula, M. 2020. “Importance of Focus Groups in Qualitative Research.” The International Journal of Humanities & Social Studies 8. doi:https://doi.org/10.24940/theijhss/2020/v8/i11/HS2011-082.

- Heger, D., and T. Korfhage. 2020. “Short- and Medium-Term Effects of Informal Eldercare on Labor Market Outcomes.” Feminist Economics 26 (4): 205–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2020.1786594.

- Heymann, J., A. R. Sprague, A. Nandi, A. Earle, P. Batra, A. Schickedanz, P.J. Chung, A. Raub. 2017. “Paid Parental Leave and Family Wellbeing in the Sustainable Development Era.” Public Health Reviews 38: 21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0067-2.

- Hsieh, H., and S. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- ICRW (International Center for Research on Women). n.d. Gender-Smart Investing: Healthcare Case Study – PORTEA. Accessed February 2021. https://www.icrw.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/ICRW_Portea_CaseStudy_2.pdf.

- IFC (International Financial Corporation). 2019. Tackling Childcare: A Guide for Employer-Supported Childcare. Washington, DC: IFC. Accessed February 2021. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/da7fbf72-e4d9-4334-955f-671a104877a7/201911-A-guide-for-employer-supported-childcare.pdf?MOD = AJPERES&CVID = mVHadh3.

- Ilkkaracan, Ipek, Kijong Kim, and Tolga Kaya. 2015. The Impact of Public Investment in Social Care Services on Employment, Gender Equality, and Poverty: The Turkish Case. Istanbul, Istanbul Technical University, Women’s Studies Center in Science, Engineering and Technology and the Levy Economics Institute.

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2018. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Organization. Accessed February 2021. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_633135/lang–en/index.htm?.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). 2017. Energy Access Outlook 2017: From Poverty to Prosperity. Paris: International Agency Agency.

- Krishnan, P. 2020. “Intersectional Grievances in Care Work: Framing Inequalities of Gender, Class and Caste.” Mobilization 25 (4): 493–512.

- Lee, N., M. O’Donnell, and K. Ross. 2020. Gender Equity in Development Finance Survey, How Do Development Finance Institutions Integrate Gender Equity Into Their Development Finance? Washington, DC: Center for Global Development. Accessed September 2021. https://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/gender-equity-in-development-finance-survey.pdf.

- Moser, Caroline. 1989. “Gender Planning in the Third World: Meeting Practical and Strategic Gender Needs.” World Development 17 (11): 1799/825.

- Nandi, Arijit, Parul Agarwal, Anoushaka Chandrashekar, and Sam Harper. 2020. “Access to Affordable Daycare and Women’s Economic Opportunities: Evidence from a Cluster Randomised Intervention in India,” OSF Preprints du3xg, Center for Open Science.

- OECD. 2014. Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes. Accessed February 2021. https://www.oecd.org/dev/development-gender/Unpaid_care_work.pdf.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2019. Enabling Women’s Economic Empowerment: New Approaches to Unpaid Care Work in Developing Countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Oxfam. 2018. Unpaid Care: Why and How to Invest – Policy Briefing for National Governments. Oxford: Oxfam GB for Oxfam International. Accessed February 2021. https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/unpaid-care-why-and- how-to-invest-policy-briefing-for-national-governments-620406.

- Power, Kate. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic has Increased the Care Burden of Women and Families.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 16 (1): 67–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561.

- Razavi, Shahra. 2007. The Political and Social Economy of Care in a Development Context: Conceptual Issues, Research Questions and Policy Options. 3 vols. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

- Savoy, C., P. Carter, and A. Lemma. 2016. Development Finance Institutions Come of Age: Policy Engagement, Impact, and New Directions. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic & International Studies.

- Seguino, Stephanie. 2020. “Engendering Macroeconomic Theory and Policy.” Feminist Economics. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1609691.

- Song, Yueping, and Xiao-yuan Dong. 2018. “Childcare Costs and Migrant and Local Mothers’ Labor Force Participation in Urban China.” Feminist Economics 24 (2): 122–146.

- Staab, Silke, and Roberto Gerhard. 2011. “Putting Two and Two Together? Early Childhood Education, Mothers’ Employment and Care Service Expansion in Chile and Mexico.” Development and Change 42 (4): 1079–1107.

- UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund). 2020. “Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Family Planning and Ending Gender-based Violence, Female Genital Mutilation and Child Marriage.” Accessed February 2021. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/impact-covid-19-pandemic-family-planning-and-ending-gender-based-violence-female-genital.

- Warner, Mildred, and Zhilin Liu. 2006. “The Importance of Child Care in Economic Development: A Comparative Analysis of Regional Economic Linkage.” Economic Development Quarterly 20 (1): 97–103.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2019. Gender Equity in the Health Workforce: Analysis of 104 Countries, Health Workforce Working Paper 1. Geneva: WHO. Accessed February 2021. https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/gender_equity-health_workforce_analysis/en/.

- World Bank. 1996. Technical Assistance (English). IEG Lessons and Practices. Washington, DC: World Bank. Accessed February 2021. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/264181468156582056/Technical-assistance.

- World Bank. 2010. Making Infrastructure Work for Women and Men: A Review of World Bank Infrastructure Projects (1995-2009). Washington, DC: World Bank. Accessed February 2021. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/28131.

- World Bank Group. 2019. Women, Business and the Law 2019 Policy Note. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Accessed February 2021. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/459771566827285080/WBL-Child-Care-4Pager-WEB.pdf.