?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Although sustainable finance (SF) has become a leading trend in the financial industry, little is known about how attention to news on SF, trust in the industry, and recent accusations of greenwashing affect the likelihood to invest in SF products. Based on a survey of a representative sample of Swiss citizens, we find that more attention to news about SF and trust in SF are positively related to the likelihood of investing in SF, whereas greenwashing perceptions are negatively related. Furthermore, attention to SF and economic news are positive predictors of sustainable finance literacy (SFL), whereas attention to SF news is negatively associated with greenwashing perception of SF. Collectively, these findings imply that engaging citizens with SF investments, particularly information seeking on SF news and trust in SF rather than SFL, need to be fostered. The Implications of the communication practices of the SF industry and policy implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

Investments in seemingly sustainable investment products have skyrocketed in Switzerland over the past years. Between 2015 and 2020, investments in sustainable finance (SF) have increased from CHF 141.7 billion to CHF 1,520 billion (Busch et al. Citation2021). Even across Europe, and the world, SF has become one of the leading trends in the financial industry, with $37 billion net new money in the fourth quarter of 2022, reaching $2.5 trillion global sustainable fund assets by the end of 2022 (Morningstar Citation2023). However, the financial industry has also experienced increased criticism regarding advertised SF investment products, which has recently been widely reported in the news media (Fletcher and Oliver Citation2022). NGOs and civil society movements regularly accuse the financial sector of greenwashing (e.g. ShareAction Citation2021). Furthermore, the industry has been strongly criticized by academics for using varying definitions and inconsistent labeling of sustainable investment products, leading to confusion and distrust among financial market actors (e.g. Amaeshi Citation2010; Lambillon and Chesney Citation2023; Cremasco and Boni Citation2022). Regulators worldwide are putting the topic of greenwashing high on their agenda, as media-intensive reactive cases, such as the investigation of DWS, or proactive reactions, such as the creation of SF taxonomies show (e.g. European Parliament Citation2022).

Although such efforts are attempts to counteract the inconsistencies of sustainable investments in the market and to provide a framework for identifying what can be considered as ‘green’ investments, for retail investors and citizens it becomes difficult to trust and evaluate the products offered by the financial industry. In fact, a recent survey among investors in Switzerland showed that although Swiss retail investors score high on general financial literacy, the level of sustainable finance literacy (SFL) is rather low, particularly among women (Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof Citation2022). In the past, academics advocated more initiatives to increase financial literacy among the public, including engaging economic news reporting (Knowles and Schifferes Citation2020). However, academic research in the field of SF that also considers the news media when explaining financial attitudes and behavior, particularly in the field of SF, is scant. Yet, research has shown that news media play a crucial role in setting the agenda (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972) and educating the public about a diverse set of topics (e.g. finance: Hayo and Neuenkirch Citation2018). In this vein, literacy about SF, trust in the SF industry, greenwashing perceptions, and attention to news about SF become decisive in explaining attitudes and investments intentions. Considering these points, the following two research questions arise: (RQ1) How is attention to news about SF and sustainable finance literacy related to sustainable investment intentions? and (RQ2) What is the role of trust and greenwashing perceptions in explaining sustainable investment intentions?

This study sought to answers these two research questions by conducting a representative survey of the Swiss public. The findings show that greenwashing perceptions are negatively related to investment intentions, and that attention to SF news and trust in SF are positively related to the likelihood of investing in SF, whereas the relationship with SFL does not seem to be robust, as previous research suggests (e.g. Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof Citation2022). Furthermore, attention to SF news and economic news attention are positive predictors of SFL. Interestingly, SF news attention was found to be negatively associated with greenwashing perceptions of SF, which might imply that the news media do not cover SF critically enough, or that SF news readers are more informed about the positive aspects of SF. On the one hand, the findings highlight the crucial role that the news media play in educating the public about economic topics; on the other hand, the results imply that the current greenwashing perceptions of the industry might have an adverse effect on the sustainable investment trend. Although greenwashing perceptions of the SF industry have rarely been explored using empirical data, this study suggests that stricter regulations in the financial markets are needed to eradicate greenwashing and misleading information, thereby increasing the public's trust in the industry and its ‘sustainable’ investment products.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Financial literacy, sustainable finance literacy and sustainable investment intentions

Financial literacy in Switzerland is generally high according to international standards, compared to other OECD countries (Ackermann and Eberle Citation2016). The OECD defines financial literacy as ‘a combination of awareness, knowledge, skill, attitude and behavior necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial well-being’ (Atkinson and Messy Citation2012, 14). Previous research argues that financial literacy is important for individuals’ financial well-being and the stability of financial markets and the economy (Kuchciak and Wiktorowicz Citation2021). Therefore, a high level of financial literacy is commonly seen as a prerequisite to becoming an active member on financial markets (e.g. van Rooij, Lusardi, and Alessie Citation2012) and making ‘good’ financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell Citation2007). However, only 50% of the respondents in a Swiss study answered the Big Three questions about financial literacy (interest rate, inflation, risk diversification) correctly, and financial literacy was considerably lower among people with less income and lower education, immigrants and non-native speaking groups, and women (Brown and Graf Citation2013). Thus, financial literacy might even be lower for newly emerging topics, such as SF.

Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022) have recently published a pre-print on sustainable finance literacy (SFL), in which they surveyed investors in Switzerland about their knowledge of SF. They define SFL as ‘the knowledge of regulations, norms, and standards about financial products that have sustainable characteristics’ (highlighted in the original, p. 2). Their results show that Swiss investors have a low level of SFL, as measured by questions regarding concepts, rules, and labels (e.g. ESG), the requirement for an ESG label, and the impact of ESG and investment on the real economy. Policymakers and scholars are increasingly advocating for increased knowledge among investors and citizens in this field. The European Commission (Citation2018), for example, stated that ‘further efforts are needed to empower citizens to choose the financial products and services that best suit their needs. This is necessary for sustainable finance literacy efforts to translate into increased demand for sustainable financial products’ (49). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no studies available on SFL, in addition to the recent pre-print published by Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022). Hence, there is an urgent need to study the state and determinants of SFL among the public and identify how it is related to investment attitudes, industry perceptions, and news attention towards SF.

In fact, knowledge about financial matters also becomes growingly decisive when it comes to environmental behavior (e.g. Chesney et al. Citation2016; Schoenmaker and Schramade Citation2019). Based on a cluster analysis of Hungarian household survey data, Bethlendi, László Nagy, and Póra (Citation2022) recently identified a consumer group in which green knowledge, financial knowledge, and the demand for green financial products were positively related. Similarly, Anderson and Robinson (Citation2020) found that individuals with high financial literacy and pro-environmental preferences are more likely to hold system-labeled ESG funds. In line with these findings, Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022) provide evidence that higher SFL is significantly related to sustainable investment product ownership. However, Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022) surveyed only experienced investors in Switzerland, thus, Swiss citizens who either had a pension plan or had one in the past. Hence, the public and their level of knowledge about SF, and how it relates to sustainable investment attitudes have not been comprehensively investigated so far. Following the findings of previous research, we assume (H1): A higher level of sustainable finance literacy is related to a higher likeliness to invest in sustainable finance investment products.

2.2. News attention, sustainable finance literacy, and sustainable investment intentions

While there are increasingly new educational offers by the public (e.g. Swiss National Bank) and private actors to improve financial literacy among the Swiss public; and at schools specifically, Switzerland does not have a national strategy for financial education, according to Arrondel et al. (Citation2021). At the same time, it is well known from research in communication science that news use is related to knowledge gain – particularly regarding political news (e.g. Beckers et al. Citation2021). Likewise, scholars in the field of environmental communication have argued and found evidence that the news media are the most widely used information source to find out about climate change (Feldman Citation2016; Newman Citation2020), and economic scholars have also shown that economic news use is positively associated with financial literacy (e.g. Hayo and Neuenkirch Citation2018). Thus, attention paid to news about certain topical areas (e.g. SF) can be assumed to be positively related to the knowledge gained in this field: (H2a) More attention being paid to sustainable finance news is positively related to sustainable finance literacy.

In fact, the news media offer a forum in which information about climate change and sustainability can be easily retrieved, evaluated, and acted upon (Carvalho Citation2010). Thus, the news media have the potential to influence attitudes, knowledge, and behavior regarding climate-related topics (cf. Feldman Citation2016). For example, a study combining a content analysis of 29 news media channels with a two-wave panel survey showed that knowledge about climate change was predicted most by print media use and prior knowledge (Oschatz, Maurer, and Haßler Citation2019). In addition, a range of studies based on the agenda-setting effect imply that more attention given to climate change in the news increases public knowledge, concern, and activism about the topic (Arlt, Hoppe, and Wolling Citation2011; Hestres Citation2014), and is likely to lead to behavioral change, although the relationship between climate change news use and offline behavioral change is less understood by research (O’Neill and Boykoff Citation2011). In contrast, research that has studied the relationship between news media reporting and stock market reactions does find support for the impact of news volume about certain listed companies and trading reactions of the respective company days after (e.g. Strauß, Vliegenthart, and Verhoeven Citation2016). Thus, following previous research, we assume: (H2b) More attention being paid to sustainable finance news is positively related to the likeliness to invest in sustainable finance investment products.

2.3. Criticism and greenwashing perceptions of sustainable finance

Knowledge about SF becomes particularly relevant considering increasing criticism towards the financial sector and its advertised sustainable investment products. Greenwashing can be defined as ‘(t)he creation or propagation of an unfounded or misleading environmentalist image’ (Oxford English Dictionary Citation2023). de Freitas Netto et al. (Citation2020) provide a systematic literature review of the concepts and typologies of greenwashing and identify four classifications of greenwashing: (1) firm-level executional, (2) firm-level claim, (3) product-level executional, and (4) product-level claim. In the realm of SF, all four classes of greenwashing are present. Financial institutions not only present themselves as green and sustainable (firm-level claim) but they also use vivid imagery and advertisements to convey their ‘green’ message (firm-level executional). Furthermore, at the product-level, sustainable investment products highlight the climate compatibility of the investments (product-level claim), while simultaneously using eye-catching and sustainability –appealing investment portfolios to transport the message (product-level executional).

In fact, since 2021 more attention is being paid to fraud, deception, and greenwashing in the financial sector. Tariq Fancy, the former CIO for Sustainable Investing at BlackRock, for example, has openly accused Wall Street of using SF as a marketing stunt, stating that ‘existing mutual funds are cynically rebranded as “green” – with no discernible change to the fund itself or its underlying strategies – simply for the sake of appearances and marketing purposes’ (Fancy Citation2021). Similarly, Desiree Fixler, who was the Global Sustainability Officer at the asset management firm DWS in Germany, was presumably fired over her criticism regarding the legitimacy of the firm’s claims whether their assets under management deserve the label ‘ESG’ or ‘green.’ As a result of these allegations, German financial regulators (BaFin) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the U.S. are investigating DWS and the marketing claims of their sustainable investment products (Eccles Citation2021).

In addition to whistleblowers from inside the industry, NGOs regularly release new reports in which they debunk the commitment of financial institutions to sustainability. For example, the ‘2 Degrees Investing Initiative’ found that 85% of green themed funds make ‘unsubstantiated and misleading impact-related claims that violate existing market regulations’ (Dupre and Roa Citation2020, 4). Academics have equally criticized the lack of transparency regarding responsible investments (Schrader Citation2006), the insufficient data availability and reporting (Ferrua Rotaru Citation2019), inconsistent definitions (Paetzold, Busch, and Chesney Citation2015; Lambillon and Chesney Citation2023), and incoherent and divergent measurements of ESG ratings across providers (Berg, Kölbel, and Rigobon Citation2022; Popescu, Hitaj, and Benetto Citation2021). Industry voices have also been vocal about the dilution of regulations regarding sustainable investments at the European level (e.g. EU Taxonomy; Webb Citation2021) and strong lobbying activities by financial institutions. What is more, the news media and particularly financial news outlets have recently published lead articles, uncovering ‘greenwashing’ in the financial sector (e.g. ‘Sustainable finance is rife with greenwash,’ The Economist; ‘Greenwashing in finance: Europe’s push to police ESG investing,’ Financial Times). Thus, given the widespread criticism regarding SF by various actors in the public sphere and the news media, it is of interest to investigate whether citizens who pay more attention to and consume news about SF have developed a similar critical viewpoint vis-à-vis the financial sector and its SF activities. Therefore, we propose: (H3) More attention being paid to news about sustainable finance is positively related with greenwashing perceptions about sustainable finance.

Likewise, given the strong media visibility of the previously described greenwashing accusations, it can be suspected that such cases might also lead to a loss of credibility of SF market practices among the public. Particularly in Switzerland, where the financial industry is one of the most important sectors of the Swiss economy, making up about ten percent of the overall Swiss economy (e.g. direct added value of CHF 70.5 billion in 2019; BAK Citation2020)´, Swiss citizens should also be vigilant about the activities on their financial markets (cf. Credit Suisse takeover by UBS in spring 2023). Zhang and colleagues (Citation2018) showed that consumers’ greenwashing perceptions are negatively related to green purchase intentions, which are even strengthened by green concerns. Hence, it is likely that citizens who perceive SF practices as greenwashing are less likely to invest in such products. Yet, given that there is no previous research about greenwashing perceptions of SF market activities among citizens and their relationship with SF investment intentions, we formulate our fourth hypothesis as follows: (H4) Stronger greenwashing perceptions about sustainable finance are negatively related to the likeliness to invest in sustainable finance investment products.

2.4. Trust in sustainable finance

In contrast to greenwashing perceptions, citizens might have also developed trust in SF market practices, given their wide coverage in the news media (Strauß Citation2022) and the pronounced support by various political and public actors (United Nations Citation2021), and stricter regulations (European Parliament Citation2022). However, a recent survey by Edelman (Citation2021) has shown that individuals worldwide have low levels of trust in financial markets and their actors. While trust levels recovered slowly after the Great Financial Crisis (2007-2009), they have declined since the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous research has shown that individuals with a lower incomes evince stronger distrust and alienation towards the financial industry (e.g. Bertrand, Mullainathan, and Shafir Citation2006). At the same time, trust has been identified as one of the main heuristics for investment decision making. For example, Guiso, Sapienza, and Zingales (Citation2008) report that generalized trust levels are positively related to stock market participation in twelve European countries, and Georgarakos and Pasini (Citation2009) find a particularly strong effect between generalized trust and stockholding in countries where stock market trust and participation is low, such as Austria, Spain, or Italy.

Trust is of special relevance in investment decisions that refer to sustainable, responsible, or ethical investments, considering the prevalence of marketing claims by financial institutions regarding SF investment products and growing greenwashing accusations (Fancy Citation2021). Marketers are increasingly facing cynicism and confusion among consumers when marketing green products (e.g. Crane Citation2000). Scholars have labeled the relationship between skepticism vis-à-vis green product claims and the rejection of such products as ‘green backlash’ (Crane Citation2000). Hence, the likelihood of investing the in SF investment products might be strongly related to the trust that individuals ascribe to SF activities and the industry. Nilsson (Citation2008), for example, finds that trust in sustainable and responsible investments among Swedish investors increases with the proportion invested in socially responsible investments (SRI). However, when testing a larger model, he did not find a significant relationship between trust in SRI and investors’ SRI behavior. Measuring trust more generally (e.g. trust in people, strangers), Gutsche, Wetzel, and Ziegler (Citation2020) only found a significant positive relationship at the 10% significance level between trust in and the amount invested in sustainable funds in Germany. Given the incoherent findings of research on trust and SF investment behavior, we test the relationship between trust in SF and the likeliness of investing in SF investment products by assuming: (H5) A higher level of trust in sustainable finance is related to a higher likeliness to invest in sustainable finance investment products.

Research on organizational trust has established that knowledge is an important determinant of trust (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman Citation1995). For example, previous research has found that increased economic knowledge is positively related to public policy support and institutional trust (e.g. ECB: Hayo and Neuenkirch Citation2014). Furthermore, consumer research has shown that more knowledgeable consumers can formulate more critical questions (Brucks Citation1985). Studies have also shown that consumer knowledge is positively related to trust in certain food product categories (e.g. Puspa and Kühl Citation2006). One of the first studies to test this relationship in the financial context, found that knowledge is positively related to narrow-scope (financial service provider) and broad-scope (financial companies) trust (Hansen Citation2012). However, the relationship between knowledge and trust regarding SF investment products might not be clear, given the controversies, recent criticisms, and greenwashing accusations (ShareAction Citation2021). Furthermore, following the theory of information asymmetry ‘information is not homogeneously distributed in the market … nor is access to relevant information open to all firms in the market’ (Schmidt and Keil Citation2013, 214). Thus, translating this theory to individual market actors, an unequal distribution of market knowledge or specialized knowledge can lead to high information asymmetry regarding SF, affecting market behavior (cf. Bergh et al. Citation2019), or other determining factors for sustainable investment behavior, such as trust or greenwashing perceptions.

On the one hand, knowledge about SF could lead to more trust, if knowing more leads to being better informed and able to distinguish between greenwashing and trustworthy SF practices, thereby becoming convinced that there are impactful and reliable SF investment opportunities. On the other hand, higher SF literacy could also imply that investors know more about the limitations and criticism of SF investment products, leading to more critical attitudes towards SF (greenwashing perceptions), which in turn might be negatively related to the likelihood of investing in SF investment products. Without assuming a certain direction, we hypothesize that the relationship between SFL and the likeliness to invest in SF products is mediated by trust and greenwashing perceptions: (H6) The relationship between sustainable finance literacy and the likeliness to invest in sustainable finance investment products is mediated by a) trust in sustainable finance and b) by greenwashing perceptions about sustainable finance.

3. Method

3.1. The state of sustainable finance in Switzerland

The Swiss government is strongly engaged in promoting the Swiss financial markets as a leader in SF and considers the trend as an ‘opportunity’ (SIF Citation2022). According to the most recent ‘Swiss Sustainable Investment Market Study Citation2021,’ the market for sustainable investments (SI) in Switzerland increased considerably, with a 48% growth rate for SI funds, from 2020 to 2021, and an increase in SI volumes by 31% within the same period. In total, sustainable funds comprise 52% of the overall Swiss fund market. However, the study used a rather broad definition of sustainable investments, including sustainable funds, mandates, and other assets of asset owners, and was based on responses from a survey among approx. 85 asset owners in Switzerland (out of 261 contacted). Beyond such industry reports, the perspectives of the broader public, the Swiss citizens, have rarely been considered in previous research in this field. However, the public plays a crucial role in questioning and legitimizing the activities of financial markets, the SF investment practices, and the institutions associated with them by acting as retail investors, pensioners (e.g. Säule 3a), activists, and democratic citizens who cast their votes in elections.

3.2. Survey

To answer the research questions and hypotheses posed in this study, we conducted a representative survey of the Swiss population. The survey was structured into various parts (see Appendix 1 for more information) and was approved by the Ethical Commission of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Zurich (reference number: 21.9.19). Wherever possible, the answer options to the questions ranged on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g. 1 = not at all; 5 = a lot) and offered the answer option of ‘I don’t know’ or ‘I don’t want to answer.’Footnote1 Furthermore, all answer options were randomized to bypass primacy effects in responses (de Leeuw, Hox, and Dillman Citation2008). As we wanted to cover all regions in Switzerland, we translated our survey from English into German, French, and Italian. The estimated time to complete the online survey was 15-20 min. To obtain a representative sample of the Swiss population, we collaborated with LINK, the Swiss market leader for market and social research. The survey was launched at the end of January and closed by mid-February 2022 – before the ‘Suisse Secret’ scandal and the start of the war in the Ukraine. Representativeness of the Swiss online population was reached through quotas at the selection and completion stage by LINK. In the following, the measurements are presented in English; complete questions with answer options for all reported survey questions can be found in Appendix 2-4.

3.3. Key variables

To measure Sustainable Finance Literacy (SFL), we opted for a mix of four questions that financial providers (UBS, Morningstar) and other organizations (e.g. Global Landscapes Forum) have used in their online quizzes, on ESG and sustainable investment. Adding all correct answers, we find that only 9.1% answered all questions correctly; 11.2% answered three questions correctly; 15.1% answered two questions; 30.6% answered one question; and 33.9% did not answer any question correctly or indicated ‘I don’t know’ to all questions. Sustainable finance news attention was measured by three items that relate to information seeking and news use behavior regarding SF. The three items formed a reliable scale ( = .85). Furthermore, to inquire citizens’ trust in SF providers, we used the scale developed by Nilsson (Citation2008) with slight adjustments. The five questions and answers formed a reliable scale (

= .89). Additionally, to measure citizens’ greenwashing perceptions towards SF, we used the scale for measuring the perception of SF as a marketing stunt from Paetzold, Busch, and Chesney (Citation2015) and adjusted it towards SF in general. Three statements were given where people could indicate their level of agreement, forming an acceptable scale (

= .76). We used a single question to assess individuals’ likeliness to invest in SF products, that is, ‘How likely is it for you to invest in sustainable investment products some time in the future?’ (answer options: 1 = very unlikely; 5 = very likely). Given that previous research has already investigated actual investment data (Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof Citation2022), we opted for this future-oriented questio because we were interested in behavioral intentions, despite being aware of the caveat of social desirability (de Leeuw, Hox, and Dillman Citation2008).

3.4. Control variables

In addition to controlling for socioeconomic variables (age, gender, education, having children, income, rural vs. urban living area: see Appendix 2), we also controlled for additional variables known from the literature to influence environmental or financial attitudes or behavior: Financial literacy was gauged by a traditional, international measurement of financial literacy based on three questions from the Baseline Survey of Financial Capability carried out by the Financial Services Authority (Atkinson et al. Citation2006). All answers to the three questions were added to form the financial literacy scale. 47.0% answered all three questions correctly; 34.5% answered two questions; 12.6% answered one question; and 5.8% answered all questions wrongly or indicated ‘I don’t know’ to all questions, similar to previous research (Brown and Graf Citation2013). Following Roser-Renouf et al. (Citation2016), we measured affective issue involvement with climate change. The two items formed a reliable climate change awareness index (r = .80). Furthermore, we used the scale by Yoon and Kim (Citation2016) of self-efficacy for environmental behavior. Taking the answers to these three statements together, we formed a scale for environmental behavior ( = .78). To control for general economic news attention, we asked three questions about economic information seeking and news use behavior (

= .89). Lastly, as a proxy measurement of engagement or interest in the topic of SF, we control for discussion frequency about SF-related topics among the respondents with friends and family. To do so, we asked them to indicate how often they discuss the (a) environmental, (b) social, and (c) climate impacts of investments with their friends and family (

= .87).

3.5. Analysis

After controlling for our attention checks and timestamps, 675 of the original 1488 participants who started the survey remained (45.4%). To test the hypotheses based on the theoretical framework, we used hierarchical regression analyses and mediation analyses with the analysis software R. Listwise deletion was used to overcome the issue of missing values when performing mediation analysis (n = 537). To test the robustness of our results, we employed predictive mean imputation for the main OLS regression analyses, which showed similar results (see Appendix, Table I and Table II). Furthermore, we conducted several diagnostic tests to ensure the validity of our OLS regression results, including Cook’s distance (outliers), Durbin-Watson test (autocorrelation), and variance inflation factor (multicollinearity). None of the OLS models indicated any estimation issues. Eventually, regarding the reliability of our scales and indices created from our survey items, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha or Pearson’s correlation coefficient, respectively; all scores were above the threshold of 0.7 or 0.8 (Bernard Citation2013) as presented in the previous section.

4. Results

4.1. Sample

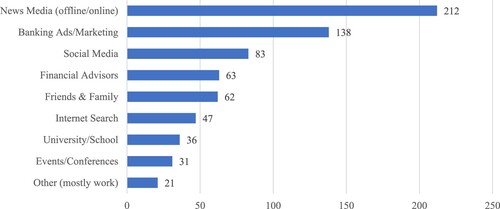

In the overall sample (n = 675), 49.2% of the survey participants were aware of SF or had heard of the term, but only 19.1% are invested in sustainable investment products, according to their self-reporting. Please note that SF can be considered a specific concept, therefore, not having heard of the topic does not imply not knowing or being able to answer questions about sustainable investments; which was the focus of the questions in the reminder of the survey. When asked how the survey participants found out about SF, the majority indicated ‘news media’ and ‘banking advertisement and marketing’ (see ). The answers shown in indicate the relevance of the news media in educating the public about SF, whereas the communication (marketing/ads) by financial institutions also plays an important role in informing (potential) clients.

Figure 1. Responses to the question ‘How did you find out about sustainable finance (click all that apply)?’; n = 675.

After excluding cases with missing values for subsequent analyses (n = 537), the average age of the participants was between 36 and 55 years. The distribution of the age groups was as follows: 18–25 years (7.1%), 26–35 years (19.2%), 36–45 years (20.9%), 46–55 years (17.9%), 56–65 years (22.9%), 66 or older (12.1%). 46.4% of the sample were female and 53.6% were male. The mean income of the participants ranged between 75,000 CHF and 99,999 CHF. 26.1% indicated to live in a city, 28.1% lived in a suburban area, and 45.8% lived in a rural area. 58.1% had one or more children and 41.9% indicated that they did not have children. The average Swiss citizen in the survey achieved the equivalent of a vocational baccalaureate for adults or a high school degree. See for all descriptives of the key variables and controls used for the analysis, and the correlation matrix among these variables in .

Table 1. Descriptives for all variables.

Table 2. Zero-Order Correlations Among All Key Variables and Control Variables

4.2. Antecedents for SFL, SF news attention, trust in SF, and greenwashing perceptions

shows the results of the OLS regression analyses, in which we tested the antecedents of various key variables. First, we find that education (β = .20, p < .001), general financial literacy (β = .18, p < .001), SF news attention (β = .14, p < .01), and economic news attention (β = .23, p < .001) are significant positive predictors of SFL. Hence, H2a is supported by showing a positive relationship between SF news attention and SFL. Second, general economic news attention has been found to be a significant and strong predictor of SF news attention (β = .45, p < .001), whereas environmental behavior (β = .13, p < .001), climate change awareness (β = .09, p < .01), discussion frequency about SF (β = .30, p < .001), SFL (β = .09, p < .01), and trust in SF (β = .06, p < .05) are also significantly related to SF news attention, but to a lower extent. However, more greenwashing perceptions (β = −.07, p < .05) are negatively related to SF news attention. Third, it becomes apparent that age (β = −.16, p < .01), education (β = −.11, p < .05) and greenwashing perceptions (β = −.22, p < .001) are negatively related to trust in SF, whereas SF news attention is positively related to trust in SF (β = .14, p < .05). Similarly, trusting SF (β = −.19, p < .001), being more aware of climate change (β = −.32, p < .001), consuming more SF news (β = −.15, p < .05) and age (β = −.09, p < .05) are negatively related to greenwashing perceptions. Hence, the hypothesis that more SF news attention leads to stronger greenwashing perceptions was not supported (H3). In contrast, citizens who pay more attention to SF news seem to have lower greenwashing perceptions.

Table 3. Antecedents of key variables.

4.3. Explaining the likeliness to invest in SF

To answer the first research question concerning the relationship between news attention on SF, sustainable finance literacy, and the intention to invest in SF, we ran hierarchical OLS regressions models. In the first step (see ), we entered sociodemographic variables into the model and found that being male (β = .14, p < .001) and having a higher income (β = .13, p < .01) were positively related to the likeliness to invest in SF. Note that the explained variance is very low in this first model (6.9%). In the second step, we checked for variables related to climate change awareness and behavior as well as discussion frequency about SF. Here, climate change awareness (β = .24, p < .001) and discussion frequency regarding SF (β = .14, p < .01) are positively related to the likelihood of investing in SF. In the third block, we entered SFL and controlled for general financial literacy. The findings show that only SFL (β = .14, p < .01) is positively related to the likeliness to invest in SF. Thus, H1 is supported but fails to remain significant once news attention and mediating variables are controlled for in the following models. The fourth block included additional variables related to SF and economic news attention. We find that SF news attention is significantly positively related to the likeliness to invest in SF (β = .29, p < .001), supporting H2b.

Table 4. Regression analyses predicting the likeliness to invest in SF.

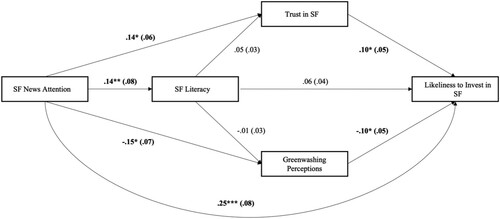

In the last block (related to research question two), we completed the model by adding trust in SF and greenwashing perceptions as mediators. The results show that while greenwashing perceptions are significantly negatively related to the outcome variable (β = −.10, p < .05), supporting H4, trust is significantly positively related to the likeliness to invest in SF (β = .10, p < .01), supporting H5. The final model explains 28.5% of the outcome variable. Considering the final model with all control variables, it can be concluded that, while the relationship between SFL and the likelihood of investing in SF (H1) does not seem robust, the hypotheses that higher use of SF news (H2b) and higher trust in SF (H5) are related to a stronger likeliness to invest in SF find support. Thus, our findings contrast those of Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022), showing that paying more attention to news and information about SF is a stronger predictor of the likeliness to invest in SF than factual knowledge about SF. Furthermore, the assumption that greenwashing perceptions are negatively related to the outcome variable is also supported (H4). presents an overview of the relationships found in the conceptual model.

Figure 2 .Conceptual model of the relationship between SF news attention, sustainable finance literacy and the likeliness to invest in sustainable finance investment products, mediated by trust in sustainable finance and greenwashing perceptions. Results are from final-entry ordinary least squares (OLS) (see and ), standardized Beta () coefficients; standard errors in parentheses; n = 537 (after listwise deletion); bolded results are within normal confidence intervals based on 5,000 bootstraps; controlled for age, gender, income, education, having children, living area, environmental behavior, climate change awareness, and discussion frequency about SF; * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

4.4. Mediation analysis

Mediation analyses are conducted to find better answers to the second research question regarding the role of trust and greenwashing perceptions in explaining SF investment intention. First, the unstandardized regression coefficient between SFL and the likelihood to invest in SF, controlling for all other variables (except for greenwashing perceptions) was found to be non-significant (B = .06, p > .05), whereas the regression between SFL and the mediator trust was highly significant (B = .22, p < .001), and the regression between trust and the likelihood to invest in SF was significant (B = .19, p < .01). Using 5,000 bootstrapped samples, the unstandardized indirect effect (average causal mediation effect) was found to be .01. The 95% confidence interval ranges from −.01 to .02 and is thus not statistically significant (p >.05). Second, we tested the mediating effect of greenwashing perceptions (trust as a control was not included here). Here, the unstandardized regression coefficient of SFL and greenwashing perceptions was non-significant (B = −.01, p > .05), whereas the regression between greenwashing perceptions and the likelihood to invest in SF was significant (B = −.17, p < .01), and the regression between SFL and the likelihood to invest in SF remains the same (B = .06, p > .05). After estimating 5,000 bootstrapped samples, the unstandardized indirect effect was .002. In line with the small coefficient, the 95% confidence interval ranges from −.01 to .02 and is thus also not statistically significant (p > .05). Therefore, the relationship between SFL and the likeliness to invest in SF is not mediated by greenwashing perceptions of SF. Hence, both H6a (trust) and H6b (greenwashing perceptions) were rejected.

5. Discussion

Although general financial literacy among the Swiss population has been found to be high compared to that of other OECD countries, a recent paper by Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022) has shown that sustainable finance literacy (SFL) among Swiss investors is considerably low. This is alarming, as the financial sector in Switzerland has shifted its focus and activities towards sustainable finance (SF) more recently, pouring billions of CHF into ESG-focused and sustainable investments (Busch et al. Citation2021), amid increasing criticism about ‘greenwashing’ in the financial sector, that has widely been covered in the news. Given the lack of research on literacy, news attention, and perceptions about SF among the public, we sought to understand the current state of knowledge about SF among the Swiss public, its relationship with news attention towards SF, and the mediating functions of trust and greenwashing perceptions on SF investment intention.

Through a representative survey, we find support for our hypothesis that higher SFL is related to a stronger likeliness to invest in SF among the Swiss population. However, this relationship was not robust, and in direct contrast to the findings of Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022). Furthermore, while almost 50% of the Swiss population surveyed (before listwise deletion) had heard or come across the term ‘Sustainable Finance,’ the answers to the four literacy questions about SF were sobering. Approximately 10% answered all four questions correctly, whereas almost 34% answered all questions incorrectly or indicated that they did not know the answer. Although we used different questions (partly even easier) than Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022), the overall findings confirm the general conclusion by Filippini, Leippold, and Wekhof (Citation2022), showing that there is a lack of SFL not only among investors but also among Swiss citizens.

Moreover, in line with research on political and environmental communication (Beckers et al. Citation2021), we could show that staying informed about SF by paying attention to news about the topic is a strong and robust predictor of the likeliness to invest in SF, thereby overruling the relevance that sustainable or financial literacy has been attributed so far in determining investment decisions. Thus, this study extends previous findings (e.g. on economic news use and knowledge and trust in the ECB: Hayo and Neuenkirch Citation2018) by showing that paying attention to information and news about certain topics tends to be more strongly related to behavioral intentions than factual knowledge. In addition, the analyses supported tentative evidence from previous research (e.g. Gutsche, Wetzel, and Ziegler Citation2020; Nilsson Citation2008) in showing that trust in SF practices is positively related to the likeliness to invest in SF. Despite the lack of previous research, this study provides proof that greenwashing perceptions about SF are negatively related to the likelihood of investing in SF, supporting research in the field of green consumer behavior (Zhang et al. Citation2018).

However, the mediation analysis showed that the relationship between SFL and the likeliness to invest in SF investment products was neither mediated by trust in SF nor by greenwashing perceptions. Further analyses also substantiated the argument that factual knowledge of SF is not related to whether citizens trust SF or perceive it as greenwashing. Hence, educating the public about SF may be less fruitful for engaging citizens in sustainable investments products. Instead, establishing trust in the SF sector, raising awareness for climate change, and increasing information seeking about SF via the news are gateways to increasing citizens' likeliness to invest in SF. Undoubtedly, the trustworthiness and reliability of SF activities as assessed by citizens will strongly depend on the respective financial provider citizens have in mind and the individual client-bank relationship (Schrader Citation2006).

However, fostering trust among citizens in the SF financial industry is crucial for accelerating the transition towards a climate-neutral future. Thus, to engage the broader public with SF investments, the following practice and policy implications are suggested. First, financial providers need to communicate transparently, honestly, and offer insights how the shift of clients’ capital towards sustainable investments really makes a difference, limits global warming, and supports a sustainable future. Thereby, greenwashing perceptions are likely to be mitigated and trust in the SF industry could be established or fostered. Second, financial regulators and authorities should strengthen their supervision activities regarding the labeling of ESG investment products, misleading sustainability claims, advertisements, and further introduce clear procedures to penalize the fraudulent use of sustainability marketing in the financial sector. Third, regarding the role of the news media, this study shows that journalists covering SF can play a mediating role in engaging citizens with sustainable investments. The results not only show that SF news attention leads to more SFL – supporting previous research on the role of the news in information acquisition (e.g. Beckers et al. Citation2021) – but also imply that it leads to lower greenwashing perceptions, an albeit worrisome result. From an industry perspective, the findings suggest that journalists seem to support the financial industry by helping to reduce greenwashing perceptions. From a more critical and normative perspective, the results suggest that journalists do not live up to their watchdog role and fail to cover SF with more scrutiny, thereby reducing greenwashing perceptions among the public (cf. Global Financial Crisis: e.g. Usher Citation2012). In fact, a recent interview study supports the apprehension that journalists are overwhelmed by PR messages about SF, by the industry, having difficulties separating news from mere marketing, and have limited resources to conduct investigative research (Strauß Citation2022). Thus, more training in covering SF (e.g. workshops) and more resources for covering the topic should be provided to financial journalists by editorial offices.

Although these findings are of direct use to corporate financial communication, financial regulators, and financial journalistic practices, the study is not without limitations. First, the use of a cross-sectional survey and hierarchical regression analyses did not allow us to draw any causal inferences. In addition, the focus on the Swiss population does not allow any generalization to the entire SF industry. Future research should adopt a comparative approach and replicate our study across various countries, including additional control variables that we did not measure (e.g. personal values and norms). Given that cultural differences towards the urgency of climate action and sustainability-related issues have been found in previous research (Wolf and Moser Citation2011), this might also be the case for SF. Finally, this study did not provide in-depth insights into the reasons, sense-making processes, and motivations of respondents for answering some of our questions in this survey in a certain way. After all, half of the respondents had not heard of SF before taking the survey. Follow-up studies should take a qualitative approach by conducting interviews or focus groups with citizens and investors to learn how and why they think about SF in a particular manner, and to find out what heuristics they use in assessing SF activities and products, eventually making an investment decision.

To summarize, the findings show that building trust in SF products and the industry, decreasing greenwashing perceptions, and triggering news seeking about SF are crucial for increasing the likeliness of citizens to invest in sustainable investment products. At the same time, these results demand financial and environmental journalism to cover the topic of SF from a more engaging and critical angle, that also helps citizens to form an informed opinion about SF investments. Furthermore, the findings imply that the financial industry needs to become more transparent, honest, and trustworthy regarding SF practices and the communication thereof. In other words, financial providers and institutions should not only improve their information material on SF but also professionalize financial advisory talks with clients, focusing more on transparency, background information on SF investment products, and impact reports of ESG investments (Strauß Citation2021). Finally, trust in the SF industry can only be fostered if the practices and activities are trustworthy, reliable, and transparent, which requires a robust and stringent regulatory and supervision framework. Future research should, therefore, gain more insights into how sustainable market practices can be tailored towards a net-zero economy by engaging citizens and the news media with the financial industry using effective communication strategies.

Compliance with ethical standards

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose regarding this article.

This research involved human participants. We surveyed a representative sample of Swiss citizens (German, French, Italian) who were recruited with the help of the polling agency LINK in Switzerland in January/February 2022.

We obtained informed consent from all participants before they started the survey.

The survey has been approved by the Ethical Commission of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Zurich on the 24th of September 2021 (number: 21.9.19).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in OSF at https://osf.io/zb3c8/.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 For the variables ‘trust in SF’ and ‘greenwashing perceptions,’, ‘I don’t know’ answers were recoded to 3 to equal the middle scale (otherwise, we would have had to deal with additional missing values).

References

- Ackermann, N., and F. Eberle. 2016. Financial literacy in Switzerland. In International handbook of financial literacy, eds. C. Aprea, E. Wuttke, K. Breuer, N. K. Koh, P. Davies, B. Greimel-Fuhrmann, and J. S. Lopus, 341–355. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Amaeshi, K. 2010. Different markets for different folks: Exploring the challenges of mainstreaming responsible investment practices. Journal of Business Ethics 92, no. 1: 41–56.

- Anderson, A., and D.T. Robinson. 2020. Financial literacy in the age of green investment. Swedish House of Finance Research Paper 19, no. 6: 1–45.

- Arlt, D., I. Hoppe, and J. Wolling. 2011. Climate change and media usage: Effects on problem awareness and behavioural intentions. International Communication Gazette 73, no. 1–2: 45–63.

- Arrondel, L., M. Haupt, M. Mancebón, G. Nicolini, M. Wälti, and J. Wiersma. 2021. Financial literacy in Western Europe. Working Paper No. 37, 1–37.

- Atkinson, A., S. McKay, E. Kempson, and S.S. Collard. 2006. Levels of financial capability in the UK: Results of a baseline survey. Public Money and Management 27, no. 1: 29–36.

- Atkinson, A., and F. Messy. 2012. Measuring financial literacy: Results of the OECD / International Network on Financial Education (INFE) pilot study. OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance and Private Pensions 15: 1–73.

- BAK. 2020. “Economic Impact of the Swiss Financial Sector.” BAK Economics AG. https://www.swissbanking.ch/_Resources/Persistent/1/d/c/1/1dc148d0616e3676f52cfdee714c87f03690378f/BAK_Economics_Economic_Impact_Swiss_Financial_Sector_Executive_Summary.pdf (accessed 29 March 2020).

- Beckers, K., P. Van Aelst, P. Verhoest, and L. d’Haenens. 2021. What do people learn from following the news? A diary study on the influence of media use on knowledge of current news stories. European Journal of Communication 36, no. 3: 254–269.

- Berg, F., J.F. Kölbel, and R. Rigobon. 2022. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings. Review of Finance.

- Bergh, D.D., D.J. Ketchen, I. Orlandi, P.P.M.A.R. Heugens, and B.K. Boyd. 2019. Information asymmetry in management research: Past accomplishments and future opportunities. Journal of Management 45, no. 1: 122–158.

- Bernard, H.R. 2013. Social research methods. Qualitive and quantitative approaches (Ed. 2). SAGE Publications.

- Bertrand, M., S. Mullainathan, and E. Shafir. 2006. Behavioral economics and marketing in aid of decision making among the poor. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 25, no. 19: 8–23.

- Bethlendi, A., L. László Nagy, and A. Póra. 2022. Green finance: The neglected consumer demand. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment.

- Brown, M., and R. Graf. 2013. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy 6, no. 2: 2–23.

- Brucks, M. 1985. The effects of product class knowledge on information search behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 12, no. 1: 1–16.

- Busch, T., P. Bruce-Clark, J. Derwall, R. Eccles, T. Hebb, A. Hoepner, C. Klein, et al. 2021. Impact Investments – a call for (re)orientation. SN Business & Economics 1, no. 2: 1–13.

- Carvalho, A. 2010. Media(ted) discourses and climate change: A focus on political subjectivity and (dis)engagement. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1, no. 2: 172–179.

- Chesney, M., A. Pana, J. Gheyssens, and L. Taschini. 2016. Environmental finance and investments (2nd ed). Berlin: Springer Verlag.

- Crane, A. 2000. “Facing the backlash: Green marketing and strategic reorientation in the 1990s.”. Journal of Strategic Marketing 8, no. 3: 277–296.

- Cremasco, C., and L. Boni. 2022. Is the European Union (EU) Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) effective in shaping sustainability objectives? An analysis of investment funds’ behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment.

- de Freitas Netto, S.V., M.F.F. Sobral, A.R.B. Ribeiro, and G.R. da Luz Soares. 2020. Concepts and forms of greenwashing: a systematic review. Environmental Science Europe 32, no. 19: 1–12.

- de Leeuw, E.D., J. Hox, and D. Dillman. 2008. International handbook of survey methodology. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Dupre, S., and P.F. Roa. 2020. “Impact washing gets a free ride. An analysis of the draft EU ecolabel criteria for financial products.” 2 Degrees Investing Initiative. https://2degrees-investing.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/2019-Paper-Impact-washing.pdf.

- Eccles, R.G. 2021. “Seven Principles For ESG Investing: A Conversation With Desiree Fixler.” Forbes, September 19. https://www.forbes.com/sites/bobeccles/2021/09/19/seven-principles-for-esg-investing-a-conversation-with-desiree-fixler/?sh=7a33279e6011.

- Edelman. 2021. Edelman Trust Barometer 2021. https://www.edelman.com/sites/g/files/aatuss191/files/2021-04/2021%20Edelman%20Trust%20Barometer%20Trust%20in%20Financial%20Services%20Global%20Report_website%20version.pdf.

- European Commission. 2018. “Financing a Sustainable European Economy. Final Report 2018 by the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance Secretariat provided by the European Commission.” European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/180131-sustainable-finance-final-report_en.pdf.

- European Parliament. 2022. “Taxonomy: MEPs do not object to inclusion of gas and nuclear activities.” News European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220701IPR34365/taxonomy-meps-do-not-object-to-inclusion-of-gas-and-nuclear-activities.

- Fancy, T. 2021. “Financial world greenwashing the public with deadly distraction in sustainable investing practices.” USA Today. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/opinion/2021/03/16/wall-street-esg-sustainable-investing-greenwashing-column/6948923002/.

- Feldman, L. 2016. Effects of TV and cable news viewing on climate change opinion, knowledge, and behavior. Oxford Research Encyclopedias, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.367.

- Ferrua Rotaru, C.S. 2019. Challenges and opportunities for sustainable finance. The Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government 25, no. 1: 1–13.

- Filippini, M., M. Leippold, and T. Wekhof. 2022. Sustainable finance literacy and the determinants of sustainable investing. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper 22, no. 02: 1–48.

- Fletcher, L., and J. Oliver. 2022. Green investing: The risk of a new mis-selling scandal. Financial Times, February 20. https://www.ft.com/content/ae78c05a-0481-4774-8f9b-d3f02e4f2c6f.

- Georgarakos, D., and G. Pasini. 2009. “Trust, sociability and stock market participation.”(SSRN Scholarly Paper Nr. 1509178). Social Science Research Network.

- Guiso, L., P. Sapienza, and L. Zingales. 2008. Trusting the stock market. The Journal of Finance 63, no. 6: 2557–2600.

- Gutsche, G., H. Wetzel, and A. Ziegler. 2020. Determinants of individual sustainable investment behavior—A framed field experiment. MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics 33.

- Hansen, T. 2012. Understanding trust in financial services: The influence of financial healthiness, knowledge, and satisfaction. Journal of Service Research 15, no. 3: 280–295.

- Hayo, B., and E. Neuenkirch. 2014. The German public and its trust in the ECB: The ole of knowledge and information search. Journal of International Money and Finance 47: 286–303.

- Hayo, B., and E. Neuenkirch. 2018. The influence of media use on layperson monetary policy knowledge in Germany. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 65, no. 1: 1–26.

- Hestres, L.E. 2014. Preaching to the choir: Internet-mediated advocacy, issue public mobilization, and climate change. New Media & Society 16, no. 2: 323–339.

- Knowles, S., and S. Schifferes. 2020. Financial capability, the financial crisis and trust in news media. Journal of Applied Journalism & Media Studies 9, no. 1: 61–83.

- Kuchciak, I., and J. Wiktorowicz. 2021. Empowering financial education by banks–social media as a modern channel. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 3: 118.

- Lambillon, A.-P., and Chesney. 2023. “How green is ‘dark green’? An analysis of SFDR Article 9 funds. SSRN. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4366889.

- Lusardi, A. 2019. Financial literacy and the need for financial education: Evidence and implications. Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics 155, no. 1: 1–8.

- Lusardi, A., and O.S. Mitchell. 2007. Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education programs. Business Economics 42, no. 1: 35–44.

- Mayer, R.C., J.H. Davis, and F.D. Schoorman. 1995. An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review 20, no. 3: 709–734.

- McCombs, M.E., and D.L. Shaw. 1972. The agenda setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly 36, no. 2: 176–187.

- Morningstar. 2023. Global sustainable fund flows: Q4 2022 in review. Morningstar Manager Research. https://assets.contentstack.io/v3/assets/blt4eb669caa7dc65b2/blt7df82e5b9c6a5528/63d40a22f1b8c22282814816/Global_ESG_Q4_2022_Flow_Report.pdf.

- Newman, N., et al. 2020. Reuters institute digital news report 2020. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Nilsson, J. 2008. Investment with a conscience: Examining the impact of pro-social attitudes and perceived financial performance on socially responsible investment behavior. Journal of Business Ethics 83, no. 2: 307–325.

- O’Neill, S., and M. Boykoff. 2011. “The role of new media in engaging the public with climate change. In Engaging the public with climate change: Behaviour change and communication, eds. L. Whitmarsh, S. O’Neill, and I. Lorenzoni, 233–251. London: Earthscan.

- Oschatz, C., M. Maurer, and J. Haßler. 2019. Learning from the news about the consequences of climate change: An amendment of the cognitive mediation model. Journal of Science Communication 18, no. 2: A07.

- Oxford English Dictionary. 2023. Greenwashing. https://www.oed.com/viewdictionaryentry/Entry/249122.

- Paetzold, F., T. Busch, and M. Chesney. 2015. More than money: Exploring the role of investment advisors for sustainable investing. Annals in Social Responsibility 1, no. 1: 195–223.

- Popescu, I.-S., C. Hitaj, and E. Benetto. 2021. Measuring the sustainability of investment funds: A critical review of methods and frameworks in sustainable finance. Journal of Cleaner Production 314: 128016.

- Puspa, J., and R. Kühl. 2006. Building Consumer’s Trust through Persuasive Interpersonal Communication in a Saturated Market: The Role of Market Mavens. No 7752, 99th Seminar, February 8-10, Bonn, Germany, European Association of Agricultural Economists.

- Roser-Renouf, C., L. Atkinson, E. Maibach, and A. Leiserowitz. 2016. The consumer as climate activist. International Journal of Communication 10: 4759–4783.

- Schmidt, J., and T. Keil. 2013. What makes a resource valuable? Identifying the drivers of firm-idiosyncratic resource value. Academy of Management Review 38, no. 2: 206–228.

- Schoenmaker, D., and W. Schramade. 2019. Principles of sustainable finance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schrader, U. 2006. Ignorant advice – customer advisory service for ethical investment funds. Business Strategy and the Environment 15, no. 3: 200–214.

- ShareAction. 2021. “New research puts big banks’ sustainability claims in doubt.” ShareAction. https://shareaction.org/news/new-research-puts-big-banks-sustainability-claims-in-doubt.

- SIF. 2022. “Sustainable finance.” State Secretariat for International Finance. https://www.sif.admin.ch/sif/en/home/finanzmarktpolitik/sustainable-finance.html (accessed 29 March 2020).

- Strauß, N. 2021. Communicating sustainable responsible investments as financial advisors: Engaging private investors with strategic communication. Sustainability 13: 3161.

- Strauß, N. 2022. Covering sustainable finance: Role perceptions, journalistic practices and moral dilemmas. Journalism 23, no. 6: 1–19.

- Strauß, N., R. Vliegenthart, and P. Verhoeven. 2016. Lagging behind? Emotions in newspaper articles and stock market prices in the Netherlands. Public Relations Review 42, no. 4: 548–555.

- Swiss Sustainable Investment Market Study. 2021. Swiss Sustainable Finance. https://www.sustainablefinance.ch/upload/cms/user/2021_06_07_SSF_Swiss_Sustainable_Investment_Market_Study_2021_E_final_Screen.pdf.

- United Nations. 2021. “Goal 13 Climate Action.” UNDP. https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals#climate-action.

- Usher, N. 2012. Ignored, uninterested, and the blame game: How The New York Times, Marketplace, and The Street distanced themselves from preventing the 2007-2009 financial crisis. Journalism 14, no. 2: 190–207.

- van Rooij, M.C., A. Lusardi, and R.J.M. Alessie. 2012. Financial literacy, retirement planning and household wealth. The Economic Journal 122, no. 560: 449–478.

- Webb, D. 2021. “Daily ESG briefing: Investors urge EU not to let gas into taxonomy.” Responsible Investor. https://www.responsible-investor.com/articles/daily-esg-briefing-investors-urge-eu-not-to-let-gas-into-taxonomy.

- Wolf, J., and S.C. Moser. 2011. Individual understandings, perceptions, and engagement with climate change: Insights from in-depth studies across the world. WIREs Climate Change 2, no. 11: 547–569.

- Yoon, H.J., and Y. Kim. 2016. Understanding green advertising attitude and behavioral intention: An application of the health belief model. Journal of Promotion Management 22: 49–70.

- Zhang, L., D. Li, C. Cao, and S. Huang. 2018. The influence of greenwashing perception on green purchasing intentions: The mediating role of green word-of-mouth and moderating role of green concern. Journal of Cleaner Production 187: 740–750.

Appendix

Description of the Survey

In the beginning, we informed the respondents about the topic of the survey (‘sustainable finance’), the research team, and we provided information on data privacy, anonymity of answers, voluntariness and the benefits and risks of participating in this research. Furthermore, a link referred to a more detailed information sheet about the research project. Before starting the survey, respondents had to confirm that they were above 18 years of age and that they read and understood the consent form.

The German translation was done by the first author (native German), and the French and Italian versions were translated by professional translators; the French version was proof-read by one of the co-authors of this manuscript (native French).

The first part of the survey dealt with questions about individuals‘ climate change attitudes and awareness, followed by questions about their familiarity with ‘sustainable finance.’ Afterwards, we asked how they found out about SF and what information sources they used, to stay informed about SF. In the following part, we asked the respondents to define SF in their own words. They were then provided with instruments and areas of SF that they had to rank regarding their perceived importance. Subsequently, we posed questions regarding their individual SF information seeking and information distribution behavior (e.g. economic news, news about SF), followed by questions about their assessment of the information and quality about SF information provided to them. Next, we wanted to find out about areas related to SF they would like to know more about (e.g. risk management), their assessment of the possible achievement of certain goals with SF (e.g. positive impact on climate), their evaluations of the attractiveness of certain SF investment products (e.g. return, risk, impact, management fees), and their evaluation of potential obstacles for SF (e.g. high risk, complexity etc.). The following sections of the survey dealt with respondents’ evaluation of SF information offered by financial providers and their assessment of certain measures to prevent the market from greenwashing (e.g. taxonomy, investigative research). The next section dealt with the Big Three financial literacy questions (Lusardi Citation2019) and four questions regarding SF knowledge. The survey ended with questions related to sociodemographic data (e.g. age, gender, education, income, political leaning) and a question whether they invested in SF products. If they indicated that they did not invest, they were presented with follow-up questions asking them reasons for not doing so. At the end of the survey, respondents also had the opportunity to leave some final remarks.

LINK has administered our survey and shared it with their online panel, consisting of 115,000 active Swiss people who reflect the Swiss population, including smaller cantons as well as German-, French- and Italian-speaking regions.

Survey Questions for Sociodemographic Variables

Age

How old are you?

- 18–15

- 26–35

- 36–45

- 46–55

- 56–65

- 66 or older

Gender

What is your gender?

- Female

- Male

- Other (please specify)

Education

What is the highest level of education you have completed? (roughly translated from the education scale in Switzerland)

- Not finished primary school

- Primary school

- 10th grade

- Secondary, junior high and high school

- Basic professional training

- Apprenticeship or vocational baccalaureate

- Teachers’ seminar, school for teaching professions

- Technical schools

- Gymnasium Matura schools

- Second apprenticeship

- Vocational baccalaureate for adults

- High school diploma for adults

- Master's diploma or diploma or post-diploma from a higher technical school

- University colleges - basic studies

- Technical colleges (FH), teacher training colleges – Bachelor

- Universities, Federal Institutes of Technology (ETH) – Bachelor

- Universities of applied sciences (FH), colleges of education – master’s, diploma

- Universities, Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology (ETH) – Masters

- Doctorate, PhD

- Other (please indicate)

Income

Last year, what was your total household income, before taxes? (If you are supported by your parents, what would you estimate for their total household income, before taxes?)

- Under 15,000 CHF

- Between 15,000 and 29,999 CHF

- Between 30,000 CHF and 49,999 CHF

- Between 50,000 CHF and 74,999 CHF

- Between 75,000 CHF and 99,999 CHF

- Between 100,000 CHF and 149,999 CHF

- Between 150,000 CHF and 300,000 CHF

- Over 300,000 CHF

- I don’t want to answer

Children

Do you have any children?

- Yes, all 18 or over

- Yes, one or more under 18

- No

Living Area

Which type of location best describes where you live?

- Urban

- Suburban

- Rural

3. Survey Questions for Key Variables

Sustainable Finance Literacy

What does ESG stand for?

- Ecological, standard, governance

- Environmental, social, governance (correct)

- Environmental, social, green

- I don’t know

What does ‘the best in class’ investment approach entail?

- Investing in those companies that are leading in their sector regarding ESG factors (correct)

- Investing in those industries that are leading in ESG factors

- Investing in indices that are leading on ESG factors

- I don’t know

The method of constructing your portfolio so that it excludes or avoids ‘problem’ stocks, such as tobacco companies, is called:

- Impact investing

- Negative screening (correct)

- Positive screening

- I don’t know

What is a green bond?

- A bond denominated in the national currency (e.g. Euro, U.S. dollars)

- Raising debt to finance environmentally-friendly investments (correct)

- Only sovereign debt issues for the purpose of funding public transportation

- I don’t know

SF News Attention

Please answer the following questions regarding your information seeking behavior: (1 = not at all; 5 = a great deal)

- How much attention to you pay to information about sustainable finance?

- In the past 30 days, how much have you actively looked for information about sustainable finance?

- How closely do you follow the news about sustainable finance?

Trust in Sustainable Finance

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree, I don’t know)

- I trust the sustainability criteria that the mainstream financial providers use to identify sustainable investments

- I trust the measurement of sustainability criteria that the mainstream financial providers use to identify sustainable investments

- I trust the data that mainstream financial providers use to identify sustainable investments

- I trust the marketing documents that mainstream financial providers use to identify sustainable investments

- I trust that mainstream financial providers make use of their right to engage with companies to promote sustainable behavior (e.g. shareholder engagement)

Greenwashing Perceptions

To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree, I don’t know)

- I perceive sustainable finance as a marketing stunt.

- I think sustainable finance is not much different from traditional investments – it’s just a new label.

- I think that sustainable finance is not contributing to a sustainable, climate-friendly future.

4. Survey Questions for Control Variables

Financial Literacy

Suppose you had 100 CHF in a savings account and the interest rate was 2% per year. After 5 years, how much do you think you would have in the account if you left the money to grow:

- More than 102 CHF (correct)

- exactly 102 CHF

- less than 102 CHF

- I don’t know

Imagine that the interest rate on your savings account was 1% per year and inflation was 2% per year. After 1 year, with the money in this account, would you be able to buy …

- More than than today

- Exactly the same as today

- Less than today (correct)?

- I don’t know

Do you think that the following statement is true or false? Buying shares in a single company provides a safer return than buying shares in several companies through a unit trust.’

- True

- False

- I don’t know

Environmental Behavior

Please indicate your level of agreement regarding the following points (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree):

- I lead an environmentally friendly lifestyle.

- I make environmentally friendly choices whenever possible

- I choose environmentally friendly products over conventional products.

Climate Change Awareness

How important is climate change to you personally?

- 1 – not at all important

- 2

- …

- 5 – extremely important

To what extent do you worry about climate change?

- 1 – not at all

- 2

- …

- 5 – a great deal

Discussion Frequency Sustainable Finance

How often do you engage in the following activities (1 = never; 5 = very often):

- I discuss the environmental impacts of financial investments with family and friends.

- I discuss the social impacts of financial investments with family and friends.

- I discuss the impacts of financial investments on climate change with family and friends.

Economic News Attention

Please answer the following questions regarding your information seeking behavior: (1 = not at all; 5 = a great deal)

- How much attention do you pay to information about the economy in general?

- In the past 30 days, how much have you actively looked for information about the economy in general?

- How closely do you follow the news about the economy in general?

Table I. Antecedents of key variables – predictive mean imputation.

Table II. Regression Analyses Predicting the Likeliness to Invest in SF – Predictive Mean Imputation.