ABSTRACT

The side-effect effect (SEE) demonstrates that the valence of an unintended side effect influences intentionality judgements; people assess harmful (helpful) side effects as (un)intentional. Some evidence suggests that the SEE can be moderated by factors relating to the side effect’s causal agent and to its recipient. However, these findings are often derived from between-subjects studies with a single or few items, limiting generalisability. Our two within-subjects experiments utilised multiple items and successfully conceptually replicated these patterns of findings. Cumulative link mixed models showed the valence of both the agent and the recipient moderated intentionality and accountability ratings. This supports the view that people represent and consider multiple factors of a SEE scenario when judging intentionality. Importantly, it also demonstrates the applicability of multi-vignette, within-subjects approaches for generalising the effect to the wider population, within individuals, and to a multitude of potential scenarios. For open materials, data, and code, see https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5MGKN.

The side-effect effect (SEE; a.k.a. “the Knobe effect”; Knobe, Citation2003a) reveals a striking asymmetry whereby people judge that morally negative, but not positive, side effects are intentional. Knobe asked participants to consider a scenario in which a company Chairman unintentionally helped or harmed the environment as a consequent to an intended action (). Knobe’s participants generally responded that the Chairman intentionally harmed, but unintentionally helped, the environment. There was also an accountability asymmetry: the Chairman deserved blame for the harm but little praise for the help.

Figure 1. Knobe’s (Citation2003a) Experiment 1 scenario.

Knobe’s (Citation2003a) explanation was that people assess a side effect’s moral valence (e.g. helping or harming the environment) and then use that assessment to determine whether intention drove the causal agent’s (e.g. the Chairman’s) behaviour. Later, Pettit and Knobe (Citation2009) formulated a more general theory that people adopt a default expectation about a situation that can be applied to multiple folk psychology concepts including intentionality, and that for the SEE, there are different defaults for the “help” versus the “harm” scenarios. This explanation would say that the Chairman in the above example should, by default, have an attitude that is at least somewhat pro-help / anti-harm towards the environment. Taking into account the Chairman’s expression of indifference and the execution of an action that will knowingly produce the side effect, observers make a scalar judgement that the Chairman is pro-harm (though not pro-help). According to Pettit and Knobe’s formulation, only perceptions of “pro” stances in “intermediate” scenarios will produce the intentionality asymmetry. The SEE is striking because we might intuitively expect its reverse: that observers assess whether a causal agent possessed intention towards an outcome and, only then, determine the morality of the agent’s actions.

The SEE is a robust effect that has replicated across a variety of samples and settings (Knobe, Citation2010; Leslie, Knobe, & Cohen, Citation2006; Mallon, Citation2008; Pellizzoni, Siegal, & Surian, Citation2009; Phelan & Sarkissian, Citation2009; Robbins, Shepard, & Rochat, Citation2017; Vonasch, & Baumeister, Citation2017) and with a larger effect size in an extensive pre-registered exact replication (Klein et al., Citation2018). Alongside the accumulation of empirical findings, a number of competing frameworks have been developed in addition to Knobe’s (Citation2003a) original and later (Pettit & Knobe, Citation2009) explanations, outlined above. These include (1) the idea that more general violations of norms (which can include, but are not limited to, moral norms) influence judgments (the “Rational Scientist” view, Uttich & Lombrozo, Citation2010), (2) that the SEE is a result of pragmatic aspects of the vignettes; for example, that different participants interpret and apply the concept of “intentional” variously (Adams & Steadman, Citation2004; Guglielmo & Malle, Citation2010a; Nichols & Ulakowski, Citation2007), (3) that there is an influential asymmetry in the degree of foreknowledge and/or belief possessed by the agent in the helpful versus harmful scenarios (Beebe, Citation2013; Beebe & Buckwalter, Citation2010; Beebe & Jensen, Citation2012) or the degree to which participants consider the agent’s foreknowledge (Laurent, Clark, & Schweitzer, Citation2015) and in the context of the side effect valence influencing the interpretation of the critical questions (Laurent, Reich, & Skorinko, Citation2019), (4) that, critically, a cost–benefit analysis can be applied in the harmful but not the helpful condition (the “Trade-Off” hypothesis, Machery, Citation2008; “Tradeoff Justification Model,” Vonasch & Baumeister, Citation2017), (5) that responsibility is a necessary antecedent of intentionality and, further, that responsibility is quickly assigned when harmful outcomes occur but that responsibility for helpful outcomes is only assigned when they are performed “for the right reasons” (Wright & Bengson, Citation2009, p. 46; the “Culpable Control Model,” Alicke & Rose, Citation2010, Citation2012), i.e. an asymmetry in the assignment of blame and praise (Nadelhoffer, Citation2004; see also Hindriks, Douven & Singmann, Citation2016), and (6) that people evaluate the (in)congruency of the agent’s traits, attitudes, and values with the side effect (the “Deep Self Concordance Model,” Sripada, Citation2010; Sripada & Konrath, Citation2011).

The accumulation of empirical evidence supporting the SEE in the context of so many competing mechanistic and theoretical explanations suggests that the area may benefit from expanding the repertoire of typical methodological approaches in order to aid SEE researchers in disentangling these theoretical frameworks in the future. While the SEE literature has benefited from a number of cleverly designed experiments, the majority share the same basic design features. In particular, many experiments tend to use only a single vignette, or occasionally, a few vignettes (though there are a small number of exceptions, e.g. Cova & Naar, Citation2012, Exp. 1; Robinson, Stey, & Alfano, Citation2015, Study 2), often in a between-subjects design. Thus, participants may be primarily responding to a quirk of a single (or very few) vignette(s) (we note that Knobe even raises this possibility in his discussion of the first experiment of his seminal Citation2003a paper). Furthermore, the Chairman scenario, or slight modifications of it, is frequently used, and experienced participants (e.g. Psychology students and MTurk workers) may already be familiar with it. Therefore, generalisation of the effect within individuals across many different scenarios is not yet verified; this is particularly important in the context of Psychology’s “replication crisis” which should compel scientists to generalise effects not only to the wider population but also to a wider pool of stimuli. While it is clear that the SEE replicates with Knobe’s original vignettes and the handful of others developed since then, one of our aims is to provide new evidence through two conceptual replications that the SEE is also broadly replicable and generalisable across many scenarios and, simultaneously, within the same individuals (i.e. in a within-subjects design; see also Feltz & Cokely, Citation2011). Finally, the literature’s conventional use of statistical analyses like t-tests and ANOVA, in combination with the typical use of single (or few) vignettes and between-subjects designs, means that variance due to both participant and item differences could be better controlled (see Judd, Westfall, & Kenny, Citation2012). Even with randomisation to different between-subjects conditions, participant differences cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor. Furthermore, where multiple items have been used, statistically uncontrolled item variance may also play a role. Thus, we hope that by providing evidence for the SEE through using openly available multiple items in a within-subjects design and statistically controlling for both participant and item variance simultaneously in two conceptual replications, our work can provide a springboard for future work on the SEE to use a similar approach to advance theoretical understanding of this interesting effect and to more easily test controlled manipulations of finer-grained aspects of the stimuli.

Thus, our work undertakes two experiments, each representing a methodologically advanced, rigorous conceptual replication of a different but nuanced aspect of the broader SEE literature: moderation of the effect due to the valence of the agent’s character (Experiment 1) and the valence of the side effect’s recipient (Experiment 2). Because these are finer-grained effects, they are well-suited to a conceptual replication approach in order to demonstrate the utility of our methodology for the area. Specifically, our aim is to provide evidence for the applicability of multi-item, within-subjects designs and analyses that control for random variance due to participants and items simultaneously (Judd et al., Citation2012) to examinations of the SEE. Both experiments utilise (1) a larger-than-usual number of openly available experimental items to generalise across, (2) within-subjects designs that eliminate between-subject variance and allow for generalisation of the effect within the same individuals as well as across individuals, and (3) an analysis strategy that accounts for random effects of both participants and items simultaneously (Judd et al., Citation2012). We hope that our demonstration of these methodological choices through conceptual replications will provide other researchers with additional, rigorous ways of testing relevant theoretical explanations in the future.

Experiment 1

In attempting to discern the mechanisms underlying the SEE, some previous empirical work has shown that factors relating to the agent can moderate it (Cova, Lantian, & Boudesseul, Citation2016), such as personality, motives, and past behaviour (Brogaard, Citation2010; Hughes & Trafimow, Citation2012, Citation2015; Shepherd, Citation2012), level of power (Robbins et al., Citation2017), skill (Guglielmo & Malle, Citation2010b), goodness or badness (Beebe & Jensen, Citation2012; Newman, De Freitas, & Knobe, Citation2015), contextual constraints on the agent (Monroe & Reeder, Citation2011), and social role (Rowe, Vonasch, & Turp, Citation2020). Participants may also strongly consider the agent’s “I don’t care” statement in representing the agent’s attitudes (Sripada & Konrath, Citation2011) as it communicates an active and negative desire (Guglielmo & Malle, Citation2010a). Participants may additionally consider areas such as stereotypes related to the agent’s occupation (e.g. Chairman of the Board; Hughes & Trafimow, Citation2012), suggesting that participants draw on general and social knowledge in representing the scenario. Experiment 1 was designed as a conceptual replication of this pattern of evidence.

While our aim is not to contrast and test theories that seek to explain these findings, the unfamiliar reader may benefit from brief descriptions of relevant models to help contextualise the pattern of findings described above. First, the “Deep Self Concordance Model” (DSCM) suggests that people evaluate the (in)congruency of the agent’s traits, attitudes, and values with the side effect (Sripada, Citation2010; Sripada & Konrath, Citation2011). In this model, individuals pay attention to the agent’s character when it is made relevant and salient (such information may come from the agent’s job role, explicit descriptions about their traits, stereotypical associations with factors like their perceived gender and name, their “I don’t care” reaction to the possibility of the side effect, and questions about the agent that precede the accountability and intentionality judgements). Thus, participants maintain consistency in their understanding of a given vignette by ascribing different levels of accountability and intentionality when the agent’s characteristics are congruent versus incongruent with the side effect. A second relevant model is the “Culpable Control Model” (CCM; Alicke & Rose, Citation2010, Citation2012). According to this framework, observers who have a negative reaction to a scenario implicitly justify their reaction by assigning blame, control, and intentionality to the agent; such negative reactions may be induced by harmful outcomes as well as unlikeable agents. This model would suggest that a negatively valenced agent may create or exacerbate negative reactions, while positively valenced agents may mitigate negative reactions to harmful outcomes, resulting in a judgement asymmetry between helpful and harmful scenarios. Closely aligned with the CCM are accounts that highlight differing degrees of blame versus praise and how this relates to the ascription of intentionality (Nadelhoffer, Citation2004; Hindriks et al., Citation2016). Both the DSCM and the CCM would be consistent with results that show a main effect of the side effect valence (the typical SEE) in addition to an interaction between the agent valence and the side effect valence. Readers should note that our foregrounding of these two accounts is not at the exclusion of other accounts; rather, it is that other frameworks tend to focus on other aspects while these two are especially applicable to considerations of the agent. Indeed, as Cova et al. (Citation2016) suggest, it is likely that multiple factors influence observers’ judgements.

While the empirical studies mentioned above tell a reliable story about the SEE, they are primarily based on single-item (or few-item) between-subjects designs, often with analyses that are unable to account for variance from participants and vignettes. Thus, the aim of Experiment 1 was to conduct a conceptual replication of these agent characteristic studies and provide evidence about the appropriateness of a multi-item, within-subjects approach.

In line with previous work, Experiment 1 tested whether (in)consistencies between the agent’s character description and the valence of the side effect moderate the SEE by comparing explicitly positive versus negative descriptions for the agents, fully crossed with harmful versus helpful side effects. In keeping with the DSCM, the CCM, and previous findings, we predicted an interaction between Agent Valence and Side Effect Valence such that positive agents would be judged as having more intentionality towards (and deserving more praise for) helpful outcomes than negative agents, while negative agents would be judged as having more intentionality towards (and deserving more blame for) harmful outcomes than positive agents. Data that support these hypotheses would replicate previous work and also show that consideration of agent-related factors makes a significant impact on judgements across many scenarios and within the same individuals; i.e. that factors relating to the agent can explain a significant amount of variance in the SEE judgements above and beyond the side effect valence itself.

Methods

Participants

A power analysis for general linear models suggested that 76 participants would be required to detect a medium effect (f2 = 0.15; e.g. Hughes & Trafimow, Citation2012) with 80% power at alpha = .05. Participants were opportunity sampled from Psychology students at the University of Chester and at Northumbria University. Ninety-two began the online study but eight did not finish; their partial data were not used. Six more participants’ data were removed because their participation duration was less than five minutes; the researchers agreed that it would be impossible to complete the experiment in an engaged fashion in such a short time. Thus, the final sample comprised 78 participants (mean age = 19.85 years, SD = 2.57; 79.5% female; Northumbria n = 41, Chester n = 37). Participants were reimbursed with participation credits. Ethical approval was given at both recruiting institutions, and the experiment was carried out in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials

Twenty-four vignettes were composed. Each vignette consisted of eight sentences. Sentence 1 introduced the agent and their job role. Sentence 2 described the agent (positively or negatively, in line with the Agent Valence experimental factor). Sentence 3 described a subordinate character presenting information relevant to a decision that the agent will need to make. Sentence 4 contained speech from the subordinate character which confirmed that an intended action will have an intended outcome and that this action will also produce a side effect (helpful or harmful, in line with the Side Effect Valence experimental factor). When the side effect was helpful, this subordinate character uttered a conditional phrase in the form of “If X, then Y AND Z.” When the side effect was harmful, the subordinate character uttered a conditional phrase in the form “If X, then Y BUT Z.” Sentence 5 contained speech from the agent confirming that they cannot be concerned with side effect Z, only with achieving intended effect Y. Sentence 6 was a continuation of the agent’s speech in which they confirmed that they would execute action X. Sentence 7 confirmed that action X was executed. Sentence 8 confirmed that side effect Z occurred as predicted.

Regarding Sentence 5, previous studies have tended to follow Knobe’s (Citation2003a) original vignettes with the agent saying that they “do not care” about the side effect, only about the intended effect. While this construction was used to make the unintended nature of the side effect clear, participants may interpret this phrasing as an active and, therefore, intentional choice and not an indifferent, neutral attitude: Guglielmo and Malle (Citation2010a) demonstrated that varying this phrasing influences how much intentionality is ascribed. To ameliorate this concern, we phrased this portion of the dialogue to highlight a lack of choice and a neutral inability (rather than a neutral attitude, given that it is debatable whether truly neutral attitudes are possible to communicate), whereby the agent expresses an inability to be concerned with the side effect (e.g. “I am not able to be concerned with … ”). See Example Experiment 1 Vignette.

Given the 2 × 2 design, four versions of each vignette were created that varied the Agent Valence (positive/negative) and the Side Effect Valence (helpful/harmful). The 96 total vignettes were Latin squared to create four lists of 24 vignettes each (six from each condition).

Procedure

Participants undertook the experiment as an online study on the Qualtrics (Citation2015–2017) survey platform. Participants were randomised to one of the four lists (for the final sample, Lists 1, 3, and 4 had 19 participants each while List 2 had 21 participants). Participants were first given information and instructions before being asked for their consent to take part. Qualtrics randomised the presentation order of the 24 vignette items for each participant; each vignette was presented one at a time. Participants were instructed to read each vignette, and they were presented with two ratings questions immediately below the vignette. The Praise/Blame question was always presented first in the format: “How much (praise/blame) does (agent name) deserve for (the side effect)?” Participants responded on a Likert scale from 0 (None) to 6 (A lot). Then participants responded to the Intentionality question in the format: “To what extent did (agent name) intentionally (help/harm) (the side effect)?” Participants also responded to this question on a Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 6 (Very much). Participants then clicked on an arrow to proceed to the next vignette. After completing the vignettes task, participants answered brief demographic questions. Mean completion time for the final sample was 20.87 min (SD = 14.21).

Analysis

To analyse the effect of Agent Valence and Side Effect Valence on (1) Accountability (Praise/Blame) and (2) Intentionality ratings, we used cumulative link mixed models (CLMMs), a type of generalised linear mixed model appropriate for ordinal response variables (Christensen, Citation2015; Liddell & Kruschke, Citation2018), fitted with the Laplace approximation using the ordinal package (Christensen, Citation2018) in R (R Development Core Team, Citation2017). This analysis strategy allows individual responses to be entered (rather than means for each condition per participant) as mixed models can account for the interdependency of repeated observations, giving more statistical power (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, Citation2008). Furthermore, mixed models can simultaneously model random effects due to participants and due to items, allowing more of the error variance to be modelled (see Clark, Citation1973, for a discussion of the importance of considering items random effects). Neither experiment was preregistered, but all materials, anonymised data, and R code are available here under a CC-BY 4.0 licence: https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5MGKN. Details of the parameter estimates of the CLMMS are given in the Results section.

Results

In the CLMM analysis for Praise/Blame ratings and the Intentionality ratings, the fixed effects were Agent Valence (positive, negative), Side Effect Valence (helpful, harmful), and the interaction between these. We used deviation coding for the two experimental factors. The models contained crossed random effects for participants and vignettes.

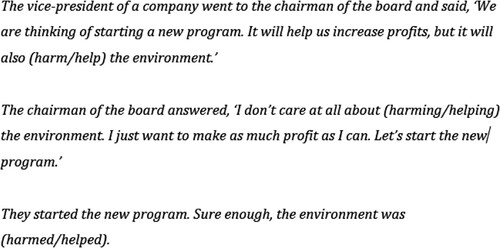

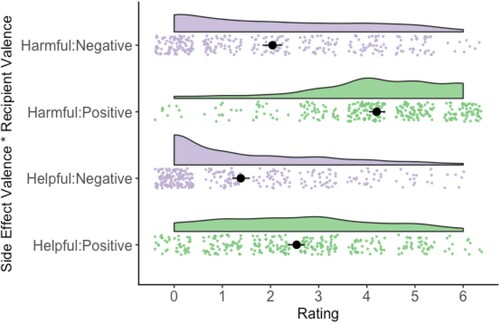

The maximal model for the Praise/Blame ratings converged (see for parameter estimates). The model showed the typical SEE, as the main effect for Side Effect Valence was significant at p < .001. In line with previous work, agents who caused harmful side effects were judged as deserving more blame than the level of praise afforded to agents who caused helpful side effects. A post-hoc decision was made to explore whether the typical SEE was clearly apparent for positive agents and for negative agents, separately, using pairwise comparisons as computed by the emmeans package in R (Lenth, Love, & Hervé, Citation2018) with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of .025. This demonstrated that participants assigned more blame for harmful side effects than praise for helpful side effects both for positive agents (z = −6.90, p < .001) and for negative agents (z = −8.70, p < .001). Importantly for our aims, the model also demonstrated an interaction between Agent Valence and Side Effect Valence that was significant at p < .001. This interaction was explored using pairwise comparisons and interpreted using a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of .025. These comparisons showed that positive agents were judged to deserve significantly more praise for helpful side effects than negative agents, (z = 3.18, p = .002). However, under the corrected alpha level, there was no significant difference in the level of blame for harmful side effects assigned to positive versus negative agents (z = −2.07, p = .038; see ).

Figure 2. Means, confidence limits, and distributions for Side Effect Valence by Agent Valence for Praise (Helpful conditions)/Blame (Harmful conditions).

Table 1. Parameter estimates for the Praise/Blame CLMM from Experiment 1.

The maximal model for the Intentionality ratings converged (see for parameter estimates). The main effect for Side Effect Valence was significant at p < .001, showing the typical SEE in which participants deemed agents to have more intention towards harmful versus helpful side effects. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of .025 showed that this held true both for positive agents (z = −6.49, p < .001) and for negative agents (z = −7.71, p < .001) separately. Furthermore, the model demonstrated an interaction between Agent Valence and Side Effect Valence that was significant at p < .001. This interaction was explored using pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of .025. These comparisons showed that for helpful side effects, positive agents were judged to have more intentionality than negative agents (z = 3.28, p = .001) and, for harmful side effects, negative agents were judged to have more intentionality than positive agents (z = −2.64, p = .008; see ).

Figure 3. Means, confidence limits, and distributions for Side Effect Valence by Agent Valence for Intentionality.

Table 2. Parameter estimates for the Intentionality CLMM from Experiment 1.

For both of the Blame/Praise and Intentionality analyses, null models were created that contained only the random effects terms. These null models were then compared to the experimental models to analyse whether the experimental models were better fits for the data using likelihood ratio tests. These analyses confirmed that they were: for Blame/Praise (AIC null = 5828.2 versus AIC experimental = 5791.3, χ2 (3) = 43.53, p < .001) and for Intentionality (AIC null = 5554.9 versus AIC experimental = 5520.8, χ2 (3) = 40.09, p < .001).

Similarly, for both Blame/Praise and Intentionality, we constructed main effects-only models consisting of fixed factors of Side Effect Valence and Agent Valence and random effects terms for participants and vignettes. We then compared these main-effects only models to the interaction models to analyse whether including the interaction term provided significantly better models of the data. These analyses confirmed that the interaction model was a significantly better fit for Blame/Praise (AIC main effects only = 5792.3 versus AIC interaction model = 5791.3, χ2 (9) = 19.02, p = .025) and for Intentionality (AIC main effects only = 5526.4 versus AIC interaction model = 5520.8, χ2 (9) = 23.65, p = .005).

Discussion

Experiment 1 provided evidence that participants’ responses were influenced by the congruency of the valence of the agent’s traits with the side effect valence. While, formally, both positive and negative agents unintentionally caused the same side effects, participants judged the agents to have more intentionality towards congruent versus incongruent side effects. Positive agents were also rated as deserving more praise for helpful side effects than negative agents, although there were no significant differences in ratings of blame for harmful side effects. Our analytical strategy allowed us to demonstrate that this moderation effect makes a statistically significant impact above and beyond the typical SEE, which was also demonstrated. These findings generally supported the hypotheses that were formulated on the basis of previous findings, which was a successful conceptual replication of previous work. The results are broadly consistent with the DSCM and the CCM, though it is less compatible that levels of blame ascription did not differ between different types of agents while judgements of intentionality in harmful scenarios did. It may be that differences in intentionality ascription are not solely reliant on asymmetries in accountability, but rather they may additionally encompass considerations of control, foreknowledge, and responsibility which might be differentially constructed due to the additional details about the agent’s positive versus negative character, as well as other aspects of the scenarios which are the focus of other accounts. Thus, Experiment 1 met our aim of providing evidence that the SEE and moderation effects due to factors relating to the agent conceptually replicate in a design using a variety of items and within the same individuals, clearly demonstrating the applicability of this methodological approach.

Experiment 2

Following Experiment 1’s successful conceptual replication, we utilised Experiment 2 to provide a conceptual replication of a less well-studied aspect of the SEE literature. While one key aspect of a typical side effect scenario is its agent, as we examined in the first experiment, another key aspect is the recipient of the side effect (e.g. the environment). It may be possible that participants also account for the characteristics of the recipient in judging the accountability and intentionality of the agent towards the side effect.

In Knobe’s (Citation2003a) experiments, the recipients were the environment (Experiment 1) and soldiers (Experiment 2). Whether participants viewed these recipients to be inherently positive or negative may have impacted their judgements, independently of whether the side effect was helpful or harmful. Knobe even acknowledged that views about businesses and the environment could be a factor in the Chairman scenario, which was partly the motivation for his second experiment involving the Lieutenant. Yet, it was also possible that agents and recipients associated with the military were viewed positively by some participants and negatively by others, introducing uncontrolled between-participant variance. Indeed, we cannot know if Knobe’s participants would have responded differently if the Chairman had caused harm to a fracking site versus the environment, or if the Lieutenant had caused harm to children, or terrorists, in contrast to his own soldiers. Nevertheless, it was not Knobe’s aim to contrast different recipients and the results from his two experiments were consistent, demonstrating that the nature of the recipient does not impede detection of the basic SEE. Nevertheless, unpublished work by Tannenbaum, Ditto, and Pizarro (Citation2007) sheds light on this question. They found that participants who had a stronger moral affinity with a salient characteristic of the recipient (i.e. values relating to the environment, the economy, political orientation, gender) showed a more pronounced SEE. In other words, Tannenbaum et al.’s results showed that perceptions about the recipient of the side effect moderated judgements of intentionality. Later, Sripada (Citation2012) found that participants accounted for the moral status of the recipient of the Chairman’s action when differently-valenced recipients were contrasted in a between-subjects design (e.g. a chemical company versus a charity versus an abortion clinic), demonstrating that the recipient description may moderate the SEE. Thus, the aim of Experiment 2 (and its key motivation) was to provide a conceptual replication of this moderation effect through a multi-item, within-subjects design and with analyses that controlled for random variance due to participants and items simultaneously.

As with Experiment 1, we would like to provide unfamiliar readers with some information about relevant theoretical explanations to aid their understanding of this moderation effect, though this should not be taken as a rejection of other frameworks. The first account is the “Rational Scientist” view, which outlines that more general violations of norms (which can include, but are not limited to, moral norms) influence judgments (Uttich & Lombrozo, Citation2010). The “norm violation” aspect of the Rational Scientist view suggests that participants utilise information about aspects like the valence of the side effect recipient to finely discriminate between “harm” scenarios with different recipients and between “help” scenarios with different recipients, because they represent more- or less-severe violations of norms (or none). For example, harming an innocent person would be a violation while harming a terrorist may not be; helping a terrorist would be a violation while helping a child would not be. Second, accounts that focus on the “trade-off” are also relevant: the “Trade-Off Hypothesis” (Machery, Citation2008) and the “Tradeoff Justification Model” (Vonasch & Baumeister, Citation2017). Broadly, these frameworks argue that observers consider whether the harmful side effect was justifiable in achieving the intended outcome. Observers assess the side effect as more intentional when the trade-off between the intended outcome and the side effect is not justifiable compared to when it is. Machery notes that no such trade-off is applicable in the typical “help” scenario, as there are no costs to weigh against the benefits. These models would predict that observers will view harming positive recipients as more intentional than harming negative ones (because harm to a positive recipient is a cost that does not justify the trade-off, whereas harming a negative recipient does not involve a cost, or is an acceptable cost). By extension, they would also predict that helping a negative recipient is more intentional than helping a positive one (because helping a negative recipient will be interpreted as a cost which does not justify the trade-off, but helping a positive recipient involves no cost).

Thus, in Experiment 2, we formulated our hypotheses in line with previous findings and with both the Rational Scientist and the “Tradeoff” models. We predicted that agents would be judged as more blameworthy and as having more intention towards harming positive recipients than negative ones (i.e. because it is immoral/costly to harm a positive person and, thus, a norm violation) and that agents would be judged as less praiseworthy and having more intention towards helping negative recipients than positive ones (i.e. because it is immoral/costly to help a negative person and, thus, a norm violation). In keeping with Knobe’s original work, we are proceeding with the assumption that “help” indicates “produces a positive outcome” and that “harm” indicates “produces a negative outcome” for the recipient. It is these meanings of “help” and “harm” that will be viewed as being congruent or incongruent with the recipient’s valence.

In addition, Experiment 2 further tests whether participants’ own Belief in a Just World (Lerner, Citation1965) is influential, which is the belief that good (bad) events generally occur to good (bad) people (Furnham, Citation2003). This aspect fits well with the norm-violation view emphasised by the Rational Scientist account, and acquiring evidence on this strengthens the conceptual replication attempt of this experiment. People with a strong belief in a just world need to alleviate the threat to their belief that injustices pose by helping victims and/or punishing perpetrators, or by blaming victims (Hafer & Bègue, Citation2005; Hafer & Sutton, Citation2016). Regarding the SEE, there are mixed findings that individual differences, like gender, extraversion, training in philosophy, and feelings of anger, influence it (Cokely & Feltz, Citation2009; Díaz, Viciana, & Gomila, Citation2017; Feltz & Cokely, Citation2011). However, an influence of belief in a just world, particularly the need to redress harm by assigning blame and intention, may influence participants’ judgements. This would mean that the participants’ own biases, in relation to their general and social knowledge, impact their representations of the scenarios and, hence, the judgements they make. With reference to the “Tradeoff” models, it is possible that these biases also influence the perceptions of costs and benefits in the scenarios. Thus, we further predicted that the expected effect (described above) would be moderated by level of belief in a just world, such that the effect would be more pronounced in those with a stronger belief, representing a need to be relatively more punitive in the case of immoral (norm-violating/costly) actions (harming a positive recipient or helping a negative one).

Methods

Participants

A power analysis for general linear models suggested that 48 participants would be needed to detect a medium effect size (f2 = 0.25) at 80% power and alpha = .05. We assumed that because this experiment was modifying the side effect itself, which has more primacy in SEE scenarios, the likely effect size would be somewhat larger than that in Experiment 1. We recruited an additional four participants in anticipation of withdrawals or data exclusions; however, we were able to retain all participants’ data. Thus, 52 participants (mean age = 21.86 years, SD = 5.85; 82.7% female) were opportunity sampled from Psychology students at the University of Chester. To better control for participation duration following Experiment 1, these participants completed the experiment in a lab setting. Participants were reimbursed £5 and participation credits. Ethical approval was given by the University of Chester Department of Psychology Ethics Committee, and the experiment was carried out in line with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials

Similarly to Experiment 1, 24 vignettes were composed. Key changes for Experiment 2 were (1) that no description was given for agents apart from their name and job role, which was held constant across vignette versions, and (2) that side effects were described as having a specific impact on a positive or negative person, group of people, or entity (e.g. disabled children versus imprisoned murderers; the environment versus a fracking site). Thus, these vignettes were seven sentences in length. Sentence 1 introduced the agent and their job role. Sentence 2 described a subordinate character coming to the agent with information relevant to a decision that the agent will need to make. Sentence 3 contained speech from the subordinate character which confirmed that an intended action will have an intended outcome and that this action will also have a side effect (helpful or harmful, in line with the Side Effect Valence experimental factor) on a specific recipient (positive or negative, in line with the Recipient Valence experimental factor) in the structure “If action X, then outcome Y, and also side effect Z.” Sentence 4 contained speech from the agent confirming that they cannot be concerned with the side effect Z, only with achieving outcome Y. Sentence 5 was a continuation of the agent’s speech in which the agent confirms that they will execute action X. Sentence 6 confirmed that action X was executed. Sentence 7 confirmed that side effect Z occurred to the recipient as predicted. See Example Experiment 2 Vignette.

Similarly to Experiment 1, four versions for each vignette were developed across the 2 × 2 design (positive or negative Recipient; helpful or harmful Side Effect). The 96 vignettes were Latin squared to create four lists with six vignettes from each condition; equal numbers of participants saw each list.

Participants were also administered the General Belief in a Just World Scale (which taps into the belief that the world is (un)just for other people; GBJW) and the Personal Belief in a Just World Scale (which taps into the belief that the world is (un)just for the self; PBJW; Dalbert, Citation1999). The GBJW comprises six items while the PBJW comprises seven items. For both, participants read statements about justice and responded on a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 6 (Strongly agree). For each scale, average scores were computed where all, or all but one, items had been answered (Dalbert, Citation1999). The scales have been found to have good validity and internal reliability and to tap discrete constructs (Dalbert, Citation1999; Furnham, Citation2003).

Procedure

Participants were randomised in blocks of four to each of the four lists. In a lab setting, the participants completed the experiment on the online survey platform Qualtrics, which randomised the 24 vignettes within each list for each participant. Participants were asked to read each vignette and respond to the same blame/praise and intentionality questions as in Experiment 1. Participants completed the vignettes task first, followed by the Just World Scales, and lastly brief demographic questions.

Analysis

The overall analysis strategy was similar to Experiment 1. For Experiment 2, the CLMMs utilised GBJW and PBJW as moderators to the interactions of the experimental factors for both the Praise/Blame and Intentionality Models.

Results

One participant did not respond to a sufficient number of PBJW items to calculate a PBJW average score, thus, this person’s data were excluded from the models utilising PBJW.

In the CLMMs for Praise/Blame ratings and the Intentionality ratings, the fixed effects were Recipient Valence (positive, negative), Side Effect Valence (helpful, harmful), GBJW or PBJW (in separate models), and the interaction between these three. We used deviation coding for the two experimental factors. The models contained crossed random effects for Agent Valence and Side Effect Valence for participants and vignettes.

Praise/Blame models

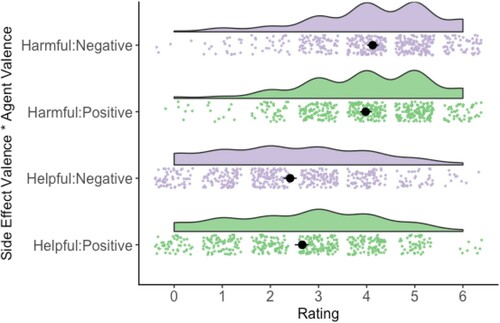

The maximal model utilising GBJW for the Praise/Blame ratings converged (see for parameter estimates). We present the key findings in order of increasing complexity. First, the model demonstrated a main effect of Side Effect Valence at p < .001, in which higher levels of blame were assigned for harmful side effects compared to levels of praise for helpful side effects.

Table 3. Parameter estimates for the Blame/Praise CLMMs from Experiment 2.

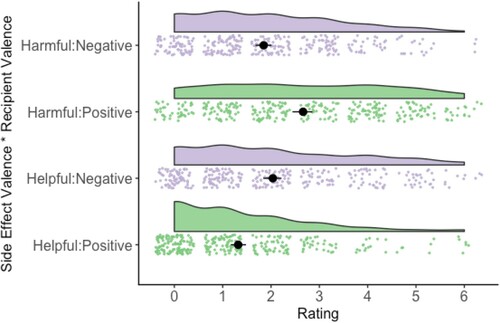

Second, the model also demonstrated the key two-way interaction between Recipient Valence and Side Effect Valence that was significant at p = .002. This interaction was explored by first creating a model which separated GBJW from the interaction (see parameter estimates in ) and then using pairwise comparisons as computed by the emmeans package in R (Lenth et al., Citation2018) with a Bonferroni corrected alpha of .025. GBJW was separated because it interacted significantly (see below). These comparisons showed that agents were rated as deserving more praise for helping positive recipients compared to negative ones (z = 5.53, p < .001) and also that agents deserved more blame for harming positive recipients compared to negative ones (z = 9.65, p < .001; see ).

Figure 4. Means, confidence limits, and distributions for Side Effect Valence by Recipient Valence for Praise (Helpful conditions)/Blame (Harmful conditions).

There was also a three-way interaction of GBJW, Recipient Valence, and Side Effect Valence that was significant at p = .009. A likelihood ratio test showed that this model was a better fit for the data than the null model containing only the random effects terms (AIC null = 3986.9 versus AIC final = 3917.1, χ2 (7) = 83.79, p < .001). We also constructed a main-effects only model with fixed factors of Side Effect Valence, Recipient Valence, and GBJW (but no interaction) and random effects for participants and vignettes. A likelihood ratio test showed that the final model containing the three-way interaction was a better fit for the data than the main-effects only model (AIC main effect 3959.2 versus AIC final 3917.1, χ2 (12) = 66.09, p < .001). This demonstrates that including the interaction provides a significantly better account of the data than the main effects only, i.e. that Recipient Valence and GBJW significantly moderate the SEE. Furthermore, a likelihood ratio test showed that the model including GBJW in the interaction was a better fit for the data than the model separating GBJW from the interaction: (AIC interaction with GBJW = 3917.1 versus AIC interaction without GBJW = 3921.0, χ2 (2) = 7.92, p = .019). This suggests that the model with the three-way interaction is a better fit for the data than the model with the two-way interaction of the experimental factors and a main effect of GBJW.

In order to better understand the interaction with GBJW, we created visualisations of the magnitude of the “congruency effects” plotted against GBJW, first for Negative Recipients and then for Positive Recipients (a and b). The “congruency effect” is the mathematical difference in the ratings given for the incongruent pairing (Negative & Helpful, or Positive & Harmful) and the congruent pairing (Negative & Harmful, or Positive & Helpful). Larger absolute numerical differences indicate a more pronounced difference in ratings; positive differences indicate a higher rating for the incongruent pairing over the congruent pairing, while negative differences indicate a higher rating for the congruent pairing over the incongruent pairing. Thus, the congruency effects were calculated by subtracting the ratings for the congruent pairing from the incongruent pairing (for the Negative Recipient figure, this = Helpful ratings – Harmful ratings; for the Positive Recipient figure, this = Harmful ratings – Helpful ratings). Collapsing the data in this way allows for an easier visualisation of the effect of GBJW, in order to understand how it interacts with Side Effect Valence and Recipient Valence (see a and b). For Negative Recipients, a shows that the magnitude of the congruency effect is similar regardless of GBJW score and is close to zero (demonstrating little difference in the accountability ratings for helping versus harming a negative recipient). In contrast, for Positive Recipients, b shows that the magnitude of the congruency effect was larger (> 2) for those with lower GBJW scores compared to those with higher GBJW scores, whose magnitude of the congruency effect was close to zero. Thus, those with a weaker belief in a just world ascribed higher accountability ratings for harming a positive recipient than helping a positive recipient (the left-hand side of b), whereas these ratings were similar for those with a strong belief in a just world (the right-hand side of b). Thus, the interaction of Recipient Valence and Side Effect Valence was more pronounced for those with a weaker belief in a just world rather than for those with a stronger belief, but only for Positive Recipients.

The maximal model for the Blame/Praise ratings involving PBJW also converged (see ). This also showed the key two-way interaction between Recipient Valence and Side Effect Valence described above, but there was no significant three-way interaction with PBJW (p = .371).

Intentionality Models

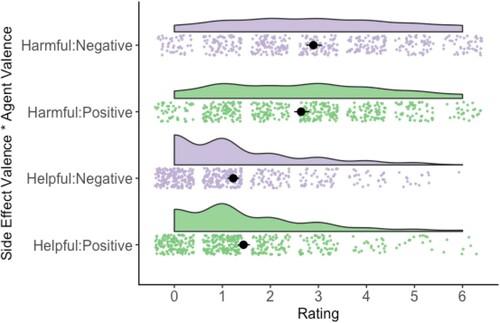

The maximal models for the Intentionality ratings involving GBJW and PBJW both converged, but there were no significant three-way interactions with these (GBJW p = .859; PBJW p = .683; see for parameter estimates). However, in both models, the key two-way interaction between Recipient Valence and Side Effect Valence was significant; thus, a model was created excluding the Just World moderators in order to clearly investigate the key two-way interaction. This model converged and, first, showed a main effect of Side Effect Valence at p < .001, in which harmful side effects were rated as more intentional than helpful side effects. The key two-way interaction between Recipient Valence and Side Effect Valence was significant at p < .001 (see ). This interaction was explored using pairwise comparisons with a Bonferroni corrected alpha level of .025. These comparisons showed that agents were rated as having more intentionality towards helping negative recipients than positive ones (z = −4.41, p < .001) and more intentionality towards harming positive recipients than negative ones (z = 5.38, p < .001; see ). A likelihood ratio test showed that this model was a better fit for the data than the null model (AIC null 3558.1 versus AIC final 3511.2, χ2 (3) = 52.86, p < .001). As before, we constructed a main-effects only model with fixed factors of Side Effect Valence and Recipient Valence (but no interaction) and random effects for participants and vignettes. A likelihood ratio test showed that the final two-way interaction model was a better fit for the data than the main-effects only model (AIC main effects 3729.7 versus AIC final interaction 3511.2, χ2 (9) = 236.5, p < .001). This demonstrates that the SEE is significantly moderated by Recipient Valence for intentionality judgements.

Figure 6. Means, confidence limits, and distributions for Side Effect Valence by Recipient Valence for Intentionality.

Table 4. Parameter estimates for the Intentionality CLMMs from Experiment 2.

Post-hoc comparisons of globally positive and negative side effects

One criticism of our approach to Experiment 2 is that these findings are unsurprising because “helping” or “harming” is not solely indicative of the moral valence of the side effect (since the moral valence of the recipient likely changes the overall valence of the side effect). In other words, these comparisons do not sufficiently test whether participants take a finer-grained approach to their intentionality judgements. In their second experiment, Kneer and Bourgeois-Gironde (Citation2017) demonstrated that professional judges ascribe different levels of intentionality and blame to agents who induce minor versus severe harmful side effects. Thus, to further test whether participants make fine-grained distinctions about intentionality between different globally morally positive side effects and also between different globally morally negative side effects, we performed post-hoc comparisons (with alpha lowered to .0125) of the intentionality ratings for (1) the globally morally positive side effects (helping positive recipients versus harming negative recipients) and (2) the globally morally negative side effects (harming positive recipients versus helping negative recipients). The first comparison revealed that agents were rated as having significantly more intention towards harming a negative recipient versus helping a positive recipient (z = −4.64, p < .001) even though these can both be considered “good” outcomes. The second comparison revealed that agents were rated as having significantly more intention towards harming a positive recipient versus helping a negative one (z = −5.96, p < .001) even though these can both be considered “bad” outcomes. Thus, participants ascribe varying levels of intentionality even between two overall “good” side effects and between two overall “bad” side effects.

Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 provide evidence that the SEE can be significantly moderated by the valence of the recipient. Overall, both final models for Praise/Blame and for Intentionality which included an interaction of Side Effect Valence and Recipient Valence (and GBJW in the case of Praise/Blame) were better fits for the data than main-effects only models, demonstrating that accounting for factors that significantly moderate the SEE above and beyond the SEE itself improves our ability to explain how participants arrive at their judgements. This is consistent with previous findings in this area and with the explanations of the Rational Scientist and the “Trade-off” models, suggesting it is a successful conceptual replication.

The findings showed that helping negative recipients was less praiseworthy and more intentional than helping positive ones, and harming positive recipients was more blameworthy and more intentional than harming negative ones. Thus, when considering incongruencies between Recipient Valence and Side Effect Valence, participants appeared to resolve these incongruencies (harming positive recipients or helping negative ones) by ascribing different levels of accountability and greater intentionality, perhaps by drawing on knowledge about the recipients and about norm violations, as per the Rational Scientist account. The results can also be read as support for the “Tradeoff” models, as they may show that observers weigh up the costs and benefits of the unintended side effects and the intended outcomes. In other words, both harming a positive recipient and helping a negative one are costs too great to justify the intended outcome. However, we caution readers against interpreting our results as ruling out other theories about the SEE, as we did not design this experiment to pit different frameworks against each other. From another angle, our analyses also show that participants make fine-grained distinctions between side effects that share the same overall valence (e.g. both positive or both negative). This experiment also provides further support for the application of multi-item, within-subjects designs and the use of mixed models to the SEE literature.

Our prediction that this effect would be stronger in participants with a stronger belief in a just world was not supported. PBJW was not influential, and this makes sense as the scenarios were about others. If future work examined scenarios where the side effect is portrayed as happening to the participant, then PBJW may moderate the SEE. GBJW interacted with Side Effect Valence and Recipient Valence for ratings of accountability (but not for ratings of intentionality), such that those with a weak belief demonstrated the typical SEE asymmetry, not those with a strong belief (in opposition to the prediction), but only for positive recipients. It is possible that a strong belief is maintained by not only assigning blame for unjust acts but also by actively assigning praise for just ones.

General discussion

Our work provides two successful conceptual replications and demonstrated the suitability of multi-item, within-subjects designs and of mixed models for investigations of the SEE. Our replications provide additional evidence in line with previous findings showing that considerations of the agent’s character and the recipient’s character moderate the SEE and that examining such factors provides an explanation for participants’ responses above and beyond the SEE itself. When faced with inconsistencies between the agent’s character and the side effect, or between the nature of the recipient and the side effect, observers appear to resolve these by assigning different levels of accountability and intentionality. Incongruencies between the agent and the outcome led to relatively lower ratings of praise and intentionality (Experiment 1), while incongruencies between the recipient and the outcome led to different ratings of accountability and greater intentionality (Experiment 2). Thus, our work emphasises the SEE’s robustness but also suggests that it can be moderated by factors relating to both the agent and the recipient, replicating previous patterns of findings.

From a methodological point of view, our advanced, rigorous conceptual replications demonstrated the SEE’s robustness and its susceptibility to moderation across many scenarios, used within-subjects designs to control for participant differences, and utilised an analysis strategy that accounted for random effects of participants and items simultaneously. These methodological avenues can help future SEE researchers further investigate the nature of the SEE and may be valuable in generating evidence for particular theoretical explanations over others. Importantly, our work has provided novel evidence via these methods that the SEE replicates, can be moderated, and generalises across individuals, within individuals, and across multiple scenarios.

Although our aim was not to contrast theoretical explanations in order to support one while rejecting another, our conceptual replications demonstrate the applicability of our methodological strategies for providing evidence to evaluate hypotheses formulated from existing theoretical explanations. Specifically, our experiments generated results that are broadly consistent with the DSCM and the CCM in Experiment 1, and the Rational Scientist view and the “Tradeoff” models in Experiment 2. More generally, our findings conceptually replicated previous work that demonstrated moderation of the SEE, and we also showed that this occurs within the same participants and across multiple scenarios. In the future, it is possible to continue advancing knowledge of the SEE by utilising within-subjects designs, multiple items, and more comprehensive analyses. Such an approach can allow comparisons of scenarios that systematically emphasise different aspects of the stimuli, thus providing rigorous tests of currently co-existing theoretical frameworks.

We should also note that while the “blame” ratings (in particular) were fairly high, all of the mean intentionality ratings were in the lower half of the Likert scale for both experiments. Although participants ascribed varying levels of intentionality, the mean ratings can all be described as “unintentional.” This is at odds with the typical SEE, i.e. our participants did not perceive clear intention towards harmful side effects. This may be because of the sentence, “I am unable to be concerned with (the side effect),” which we used to communicate a lack of choice and neutral inability towards the side effect over the typical “I don’t care about (the side effect),” which may communicate an active choice and intentional attitude to show indifference towards the side effect (Guglielmo & Malle, Citation2010a).

It may be that when the vignette makes clear that the agent has a passive relationship with the side effect (rather than an active one), intentionality weakens despite the SEE asymmetry still being apparent. Both the Rational Scientist view (Uttich & Lombrozo, Citation2010) with its focus on norm violations, and the “Tradeoff” models (Machery, Citation2008; Vonasch & Baumeister, Citation2017), first highlighted in the context of Experiment 2, may shed light on this observation. The former would suggest that the passive stance means that the harmful side effect is viewed as a more tolerable norm violation. The latter would suggest that the agent’s more passive stance towards the side effect may affect the cost–benefit analysis in which observers engage, such that the trade-off is more justifiable because the agent is not actively disregarding the side effect. However, it is also possible that this observation is due to a methodological artefact: the high degree of intentionality found previously may be related to quirks of the single or few vignettes used and individual differences in the typical between-subjects design; in our study, such responses may have “averaged out” across our larger set of scenarios and/or been controlled by our within-subjects design. Given that our work demonstrates that it is possible to examine multiple scenarios in a within-subjects design, it would be prudent for future work to systematically manipulate the formulation and compare the original negative, active “I don’t care” stance, to our neutral, passive one, as well as to Guglielmo and Malle’s active, “welcoming” one.

Our work is not without limitations. Our student samples had relatively young mean ages and were mostly female. While the SEE has been replicated in many samples, there is substantial variation in its prominence in different cultures (Klein et al., Citation2018; Robbins et al., Citation2017). Additionally, while our work suggests that a general belief in a just world has some impact on accountability judgments, future work that directly manipulates such constructs would provide a clearer picture of the interaction of observers’ moral schemas with factors relating to the scenarios. Furthermore, using a design similar to our multi-item, within-subjects experiments, future research can systematically manipulate and compare the orders of the accountability and intentionality questions to examine how these judgements influence each other. This would provide a test of theories that link the assignment of blame (in particular) to judgements of intentionality. This would provide evidence in addition to that from studies which have examined different types of intentionality and attitudinal questions and the presence/absence of the accountability question (e.g. Cova, Citation2017; Cova et al., Citation2016; Knobe, Citation2003b) and how participants understand and interpret them (Laurent, Reich, & Skorinko, Citation2021).

Work on the SEE should also consider its application to different spheres of human activity, similar to Kneer and Bourgeois-Gironde’s (Citation2017) work on samples of professional judges. A common strategy among defence lawyers is to demean a victim’s character (e.g. by highlighting a victim’s sexual history, or explicitly activating negative stereotypes related to the victim’s ethnicity). The findings of Experiment 2 suggest that if victims are seen in a negative light by a jury, then jurors may perceive the actions of the accused individual as less blameworthy and less intentional (Furnham, Citation2003). Such assessments relating to accused persons may influence outcome verdicts.

In sum, our work provides conceptual replications of previous studies that show that individuals represent and consider aspects such as the valence of agents and recipients and consistency between characters and outcomes in making fine-grained judgements about intentionality and accountability. This evidence is consistent with the view of Cova et al. (Citation2016), who suggested that a multitude of factors likely influence such decisions. Our findings alongside the literature’s accumulated empirical evidence suggest that while the SEE appears to be a robust phenomenon, it also represents a complex and multifaceted moral decision-making process. This process as well as its possible mechanisms can be studied in a fine-grained way by continuing to utilise innovative and robust methods such as multiple items, within-subjects designs, and statistically accounting for by-participant and by-item variance.

Data availability statement

The experimental materials, anonymised data, and R analytical code are openly available here: https://www.doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5MGKN.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, F., & Steadman, A. (2004). Intentional action in ordinary language: Core concept or pragmatic understanding? Analysis, 64(2), 173–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8284.2004.00480.x

- Alicke, M., & Rose, D. (2010). Culpable control or moral concepts? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(4), 330–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10001664

- Alicke, M., & Rose, D. (2012). Culpable control and causal deviance. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(10), 723–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2012.00459.x

- Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., & Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modelling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59(4), 390–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

- Beebe, J. R. (2013). A Knobe effect for belief ascriptions. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 4(2), 235–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-013-0132-9

- Beebe, J. R., & Buckwalter, W. (2010). The epistemic side-effect effect. Mind & Language, 25(4), 474–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2010.01398.x

- Beebe, J. R., & Jensen, M. (2012). Surprising connections between knowledge and action: The robustness of the epistemic side-effect effect. Philosophical Psychology, 25(5), 689–715. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2011.622439

- Brogaard, B. (2010). “Stupid people deserve what they get”: The effects of personality assessment on judgments of intentional action. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(4), 332–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X1000169X

- Christensen, R. H. B. (2015). Analysis of ordinal data with cumulative link models – estimation with the R-package ordinal. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ordinal/vignettes/clm_intro.pdf

- Christensen, R. H. B. (2018). Ordinal - regression models for ordinal data (R Package Version 2018.4-19). http://www.cran.r-project.org/package=ordinal

- Clark, H. H. (1973). The language-as-fixed-effect fallacy: A critique of language statistics in psychological research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 12(4), 335–359. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5371(73)80014-3

- Cokely, E. T., & Feltz, A. (2009). Individual differences, judgment biases, and theory-of-mind: Deconstructing the intentional action side effect asymmetry. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.10.007

- Cova, F. (2017). Intentional action and the frame-of-mind argument: New experimental challenges to hindriks. Philosophical Explorations, 20(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13869795.2016.1234638

- Cova, F., Lantian, A., & Boudesseul, J. (2016). Can the Knobe effect be explained away? Methodological controversies in the study of the relationship between intentionality and morality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(10), 1295–1308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216656356

- Cova, F., & Naar, H. (2012). Side-Effect effect without side effects: The pervasive impact of moral considerations on judgments of intentionality. Philosophical Psychology, 25(6), 837–854. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2011.622363

- Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the Personal belief in a Just World scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022091609047

- Díaz, R., Viciana, H., & Gomila, A. (2017). Cold side-effect effect: Affect does not mediate the influence of moral considerations in intentionality judgments. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00295

- Feltz, A., & Cokely, E. T. (2011). Individual differences in theory-of-mind judgments: Order effects and side effects. Philosophical Psychology, 24(3), 343–355. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2011.556611

- Furnham, A. (2003). Belief in a just world: Research progress over the past decade. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(5), 795–817. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00072-7

- Guglielmo, S., & Malle, B. F. (2010a). Can unintended side effects be intentional? Resolving a controversy over intentionality and morality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(12), 1635–1647. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210386733

- Guglielmo, S., & Malle, B. F. (2010b). Enough skill to kill: Intentionality judgments and the moral valence of action. Cognition, 117(2), 139–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.08.002

- Hafer, C. L., & Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: Problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 128–167. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.1.128

- Hafer, C. L., & Sutton, R. (2016). Belief in a just world. In C. Sabbagh & M. Schmitt (Eds.), Handbook of social justice theory and research (pp. 145–160). Springer.

- Hindriks, F., Douven, I., & Singmann, H. (2016). A new angle on the Knobe effect: Intentionality correlates with blame, not with praise. Mind & Language, 31(2), 204–220. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/mila.12101

- Hughes, J. S., & Trafimow, D. (2012). Inferences about character and motive influence intentionality attributions about side effects. British Journal of Social Psychology, 51(4), 661–673. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8309.2011.02031.x

- Hughes, J. S., & Trafimow, D. (2015). Mind attributions about moral actors: Intentionality is greater given coherent cues. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54(2), 220–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12077

- Judd, C. M., Westfall, J., & Kenny, D. A. (2012). Treating stimuli as a random factor in social psychology: A new and comprehensive solution to a pervasive but largely ignored problem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028347

- Klein, R. A., Vianello, M., Hasselman, F., Adams, B. G., Adams, R. B., Alper, S., … Nosek, B. A. (2018). Many labs 2: Investigating variation in replicability across sample and setting. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(4), 443–490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245918810225

- Kneer, M., & Bourgeois-Gironde, S. (2017). Mens rea ascription, expertise and outcome effects: Professional judges surveyed. Cognition, 169, 139–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.08.008

- Knobe, J. (2003a). Intentional action and side effects in ordinary language. Analysis, 63(3), 190–194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/63.3.190

- Knobe, J. (2003b). Intentional action in folk psychology: An experimental investigation. Philosophical Psychology, 16(2), 309–324. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09515080307771

- Knobe, J. (2010). Person as scientist, person as moralist. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(4), 315–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000907

- Laurent, S. M., Clark, B. A., & Schweitzer, K. A. (2015). Why side-effect outcomes do not affect intuitions about intentional actions: Properly shifting the focus from intentional outcomes back to intentional actions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000011

- Laurent, S. M., Reich, B. J., & Skorinko, J. L. M. (2019). Reconstructing the side-effect effect: A new way of understanding how moral considerations drive intentionality asymmetries. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148, 1747–1766. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000554

- Laurent, S. M., Reich, B. J., & Skorinko, J. L. M. (2021). Understanding side-effect intentionality asymmetries: Meaning, morality, or attitudes and defaults? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(3), 410–425. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220928237

- Lenth, R., Love, J., & Hervé, M. (2018). Package emmeans. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/emmeans.pdf.

- Lerner, M. J. (1965). Evaluation of performance as a function of performer’s reward and attractiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1(4), 355–360. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021806

- Leslie, A. M., Knobe, J., & Cohen, A. (2006). Acting intentionally and the side-effect effect: Theory of mind and moral judgment. Psychological Science, 17(5), 421–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01722.x

- Liddell, T. M., & Kruschke, J. K. (2018). Analyzing ordinal data with metric models: What could possibly go wrong? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 328–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.08.009

- Machery, E. (2008). The folk concept of intentional action: Philosophical and experimental issues. Mind & Language, 23(2), 165–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2007.00336.x

- Mallon, R. (2008). Knobe versus Machery: Testing the trade-off hypothesis. Mind & Language, 23(2), 247–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2007.00339.x

- Monroe, A. E., & Reeder, G. D. (2011). Motive-matching: Perceptions of intentionality for coerced action. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1255–1261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.012

- Nadelhoffer, T. (2004). On praise, side effects, and folk ascriptions of intentionality. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 24(2), 196–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091241

- Newman, G. E., De Freitas, J., & Knobe, J. (2015). Beliefs about the true self explain asymmetries based on moral judgment. Cognitive Science, 39(1), 96–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12134

- Nichols, S., & Ulatowski, J. (2007). Intuitions and individual differences: The Knobe effect revisited. Mind & Language, 22(4), 346–365. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2007.00312.x

- Pellizzoni, S., Siegal, M., & Surian, L. (2009). Foreknowledge, caring, and the side-effect effect in young children. Developmental Psychology, 45(1), 289–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014165

- Pettit, D., & Knobe, J. (2009). The pervasive impact of moral judgment. Mind & Language, 24(5), 586–604. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2009.01375.x

- Phelan, M., & Sarkissian, H. (2009). Is the ‘trade-off hypothesis’ worth trading for? Mind & Language, 24(2), 164–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2008.01358.x

- Qualtrics. (2015–2017). Qualtrics. http://qualtrics.com/

- R Development Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org

- Robbins, E., Shepard, J., & Rochat, P. (2017). Variations in judgements of intentional action and moral evaluation across eight cultures. Cognition, 164, 22–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.02.012

- Robinson, B., Stey, P., & Alfano, M. (2015). Reversing the side-effect effect: The power of salient norms. Philosophical Studies, 172(1), 177–206. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11908-014-0283-2

- Rowe, S. J., Vonasch, A. J., & Turp, M.-J. (2020). Unjustifiably irresponsible: The effects of social roles on attributions of intent. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 194855062097108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620971086

- Shepherd, J. (2012). Action, attitude, and the Knobe effect: Another asymmetry. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 3(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13164-011-0079-7

- Sripada, C. S. (2010). The deep self model and asymmetries in folk judgments about intentional action. Philosophical Studies, 151(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-009-9423-5

- Sripada, C. S. (2012). Mental state attributions and the side-effect effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 232–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.07.008

- Sripada, C. S., & Konrath, S. (2011). Telling more than we can know about intentional action. Mind & Language, 26(3), 353–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2011.01421.x

- Tannenbaum, D., Ditto, P. H., & Pizarro, D. A. (2007). Different moral values produce different judgments of intentional action. Unpublished manuscript. Downloaded from academia.edu, The Pennsylvania State University.

- Uttich, K., & Lombrozo, T. (2010). Norms inform mental state ascriptions: A rational explanation for the side-effect effect. Cognition, 116(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.04.003

- Vonasch, A. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2017). Unjustified side effects were strongly intended: Taboo tradeoffs and the side-effect effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 68, 83–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2016.05.006

- Wright, J. C., & Bengson, J. (2009). Asymmetries in judgments of responsibility and intentional action. Mind & Language, 24(1), 24–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0017.2008.01352.x