ABSTRACT

We examined the interplay of message plausibility and trustworthiness in the validation of tweet-like messages. Reading times served as implicit indicator for validation and participants rated the tweets’ plausibility and source credibility. In Experiment 1, plausibility was varied via text-belief consistency and trustworthiness via the message’s fit with the source’s typical argumentative position. Participants read belief-inconsistent (vs. belief-consistent) messages longer and judged these as less plausible. Similarly, participants read messages from untrustworthy (vs. trustworthy) sources longer and judged these as less plausible. Belief-consistent messages by a trustworthy (vs. untrustworthy) source were judged as more plausible. In Experiment 2, plausibility was varied via world-knowledge consistency and trustworthiness via the reputation of media organizations. Participants read plausible messages from untrustworthy (vs. trustworthy) sources more slowly. Plausibility and trustworthiness seem to be considered in the validation of tweet-like messages, but their exact relationship seems to depend on contextual factors.

Readers using the World Wide Web to learn more about socioscientific issues are faced with an abundance of information, which can be inaccurate and imbalanced, especially in social-media outlets. Despite the fact that content providers and social media platforms have adjusted their policies to counteract the spread of inaccurate or imbalanced information, misinformation is still spread with little gatekeeping (e.g. Vosoughi et al., Citation2018). Most of the existing research on the evaluation of the information accuracy in an online context has focused on biasing effects of motivated processing such as the strategic preference for information and more positive evaluations of information that aligns with self-beliefs (Kahne & Bowyer, Citation2017). In this article, we study the evaluation of online information from a different theoretical perspective, starting from the assumption that the comprehension of online information already entails a passive process called validation, that is, a general mechanism that implicitly evaluates the consistency of incoming text information with the current mental model, accessible world knowledge, and prior beliefs (Richter, Citation2015).

Experimental approaches based on a variety of paradigms suggest that validation is an integral and routine component of text comprehension (e.g. Ferretti et al., Citation2008; Maier & Richter, Citation2013; Rapp & Kendeou, Citation2009; Richter et al., Citation2009; Schroeder et al., Citation2008). However, research on contextual factors affecting validation has been more recent (e.g. Gilead et al., Citation2019; Guéraud et al., Citation2018; Piest et al., Citation2018; Singer & Doering, Citation2014). We propose that source credibility is a specific type of contextual information that is particularly important for validation because it may signal to the reader whether information provided by the source is believable or not. Thus, source credibility itself bears a strong conceptual overlap to validity, permitting source credibility to affect the validation of information.

We examine the extent that source credibility, more precisely the trustworthiness of sources, is considered in the validation of text information in a social media context for which the evaluation of the plausibility of information is a particularly important issue (Metzger et al., Citation2010). In two experiments, we used short messages in Twitter style (i.e. tweets) with varying plausibility (text-belief or world-knowledge consistency) and varying trustworthiness (source-message consistency or reputation of a media organisation). We collected plausibility and source credibility judgments as explicit and reading times as implicit measurements to receive a thorough understanding of online and offline evaluation processes (Rapp & Mensink, Citation2011).

In the following review, we start with research on validation and the text-belief consistency effect, which provides the conceptual framework for this article. We then briefly review relevant research on the evaluation of source information and the available studies that have investigated combined effects of plausibility and source credibility on validation. This discussion forms the basis for the hypotheses tested in the current experiments.

Validation of text information: implicit plausibility checks

Plausibility may be defined as the “acceptability or likelihood of a situation or a sentence describing it” (Matsuki et al., Citation2011, p. 926). Readers continually check the plausibility of incoming text information against activated world knowledge and relevant beliefs in a routine and nonstrategic process called validation (O’Brien & Cook, Citation2016a, Citation2016b; Richter, Citation2015; Singer, Citation2013, Citation2019). Different lines of research support the assumption of a routine validation process. For example, Richter et al. (Citation2009) introduced a Stroop-like paradigm (Stroop, Citation1935) to investigate routine validation processes. If validation is routine and nonstrategic, then reading world-knowledge inconsistent sentences should elicit a negative response tendency. This tendency should interfere with positive responses in an unrelated judgment task, implying that these judgments should be slowed down. Richter et al. (Citation2009) found this slow-down (epistemic Stroop effect) in two experiments with true and false sentences, which support the assumption of the involuntary and routine character of validation processes. A growing body of research with different stimuli, such as true versus false, merely plausible versus implausible sentences, and matching versus mismatching audiovisual information to opinion statements testifies to the robustness and generality of the epistemic Stroop effect (e.g. Gilead et al., Citation2019; Isberner & Richter, Citation2013, Citation2014; Piest et al., Citation2018). Experiments based on eye-tracking (Matsuki et al., Citation2011), event-related potential data (e.g. Ferretti et al., Citation2008), and reading times (e.g. Cook & O’Brien, Citation2014) provide further evidence for routine validation. For example, numerous experiments with the inconsistency paradigm show that reading times are longer for sentences that conflict with information provided earlier in the text and pertinent prior knowledge (e.g.Albrecht & O'Brien, Citation1993; O'Brien & Albrecht, Citation1992).

O’Brien and Cook (Citation2016a, Citation2016b) proposed the Resonance-Integration-Validation Model (RI-Val) in which resonance, integration, and validation are three passive, asynchronous processes that once started run to completion. A resonance-like process triggered by the information activates memory-based knowledge (R; Myers & O’Brien, Citation1998; O’Brien & Myers, Citation1999). Based on conceptual overlap, linkages between the information and content in active memory are made (I). In a third process, these linkages are validated against information in active memory (Val). The three processes start asynchronously but overlap and work in a cascaded style.

Validation and text-belief consistency effects

Knowledge is usually regarded to subsume accurate and objective representations of the world whereas beliefs are subjective cognitions that also refer to the world and do not need to be true or justified. Validation processes can be based on readers’ world knowledge and prior beliefs alike (Richter, Citation2015), regardless of the fact that knowledge and beliefs may differ in their epistemic status (e.g. Southerland et al., Citation2001). For example, reading text information about a controversial socioscientific topic (e.g. climate change) might activate relevant prior beliefs among other aspects. To evaluate this information, readers may use relevant prior beliefs to validate text information, which in turn affects comprehension processes and outcomes. Gilead et al. (Citation2019) showed that statements contradicting personal beliefs (e.g. “The Internet has made people more isolated/sociable”) elicit the same epistemic Stroop effect in comprehension processes, indicating a negative response tendency, which has been found with world-knowledge inconsistent sentences. Epistemic Stroop effects have even been demonstrated for sentences that threaten readers’ self-concept (Abendroth et al., Citation2022). Numerous studies have also shown that under most circumstances, readers comprehend belief-consistent information to a greater extent than belief-inconsistent information (text-belief consistency effect; e.g. Maier et al., Citation2018; Maier & Richter, Citation2013, Citation2014; Schroeder et al., Citation2008; Wiley, Citation2005). In their Two-Step Model of Validation, Richter and Maier (Citation2017) posit that these effects are due to the validation mechanism. By default, information detected as implausible during comprehension (e.g. belief-inconsistent information) is processed in a relatively shallow manner, leading to a mental model that is biased towards readers’ prior beliefs. Such text-belief consistency effects occur with different types of texts, different types of assessments of prior beliefs, and different types of comprehension measures (for reviews, see Richter et al., Citation2020; Richter & Maier, Citation2017). In conclusion, a growing body of research on validation and text-belief consistency effects suggests that readers routinely assess the plausibility during reading and validate it against relevant world knowledge and prior beliefs, yet the possible influence of source information on validation has received relatively little attention.

The roles of source credibility and plausibility in text comprehension

The credibility of a source conveying information is conceptually and empirically related to the validity of the information. In general, a credible source signals to a reader that the information is likely to be valid. In research on source credibility, it is common to distinguish two dimensions of the construct. Expertise refers “to the extent to which a speaker is perceived to be capable of making correct assertions”, whereas trustworthiness “refers to the degree to which an audience perceives the assertions made by a communicator to be ones that the speaker considers valid” (Pornpitakpan, Citation2004, p. 244; see also Lombardi et al., Citation2014; Self, Citation2009). The experiments reported in this article focus on trustworthiness, the credibility dimension which has rarely been examined in the context of validation (with the exception of Foy et al., Citation2017). Trustworthiness may be particularly relevant in a social media context, as it may be easier and more important for readers to evaluate the trustworthiness of a source than to evaluate its expertise.

When readers comprehend multiple texts that describe or discuss a specific topic from different or even conflicting perspectives (e.g. scientific texts dealing with the same phenomenon or argumentative texts advocating different positions in a political debate), source information is particularly relevant (e.g. Britt et al., Citation1999). In multiple text comprehension, a reader ideally constructs a document model, which is a mental representation that consists of an intertext model and an integrated mental model (Perfetti et al., Citation1999). Source information is relevant for the construction of an adequate intertext model that includes source information along with the semantic and argumentative links between multiple documents. However, source information, and especially cues to the credibility of the source, is also relevant for constructing an integrated mental model because it can be used strategically to weigh and select information that should be included in the integrated mental model. Broadly in line with these assumptions, several studies indicate that multiple text comprehension improves when readers engage in the processing of credibility-related source features such as evaluating texts for trustworthiness based on source characteristics (e.g. Anmarkrud et al., Citation2014; Bråten et al., Citation2009; Goldman et al., Citation2012; Wiley et al., Citation2009; Wineburg, Citation1991).

The discrepancy-induced source comprehension assumption (D-ISC assumption; Braasch et al., Citation2012) focuses specifically on the processing of conflicting information by multiple sources and builds on the Documents Model Framework (Perfetti et al., Citation1999). The assumption holds that inconsistencies within a text or between texts prompt readers to pay more attention to source information. To test this assumption, Braasch et al. (Citation2012) presented participants with two-sentence news reports, collected eye movements, and memory data. Stories consisted of consistent or discrepant claims made by two sources. Discrepant claims increased attention for source information, as indicated by eye-tracking data and memory of source information (for similar results, see Kammerer et al., Citation2016; Rouet et al., Citation2016). The basic idea of the D-ISC model has also been supported by studies with implausible (belief-inconsistent) information (e.g. Bråten et al., Citation2016; de Pereyra et al., Citation2014).

The D-ISC model predicts how inconsistent or implausible information affects the processing of source information. Only a handful of studies to date have addressed the complementary question of how source information affects the processing of implausible information in a text. Foy et al. (Citation2017, Experiment 1) used short narratives with a person introduced as a trustworthy or untrustworthy source (e.g. a sober vs. drugged person). Later in the story, this source would state something implausible (e.g. “There are wolves in the backyard”). Participants read the implausible assertions and the subsequent (spillover) sentences faster when these assertions came from a trustworthy compared to an untrustworthy source, indicating that source credibility affected validation in making the implausible assertion appear more plausible. In contrast to Foy et al. (Citation2017, Experiment 1) who used assertions that were merely implausible in the story world, Wertgen and Richter (Citation2020) used assertions that were clearly consistent or inconsistent with world knowledge and varied source credibility through expertise. A source introduced as an expert or non-expert in a specific field (e.g. physics) stated a fact consistent (e.g. “the relativity theory is a theory by Einstein”) or inconsistent with general world knowledge (e.g. “the relativity theory is a theory by Newton”). In addition to plausibility and source credibility ratings as explicit measurements of evaluation (Experiment 1), Wertgen and Richter used reading times on target and spillover sentences as an online indicator of validation (Experiment 2). Analyses revealed an interaction effect of plausibility and source credibility on plausibility ratings and reading times. Participants rated the plausibility of an assertion slightly higher when a low-credible source stated a world-knowledge inconsistent assertion compared to a high-credible source. Similarly, reading times were longer for a high-credible source stating a world-knowledge inconsistent assertion compared to a low-credible source. Interestingly, this pattern of results emerged on spillover sentences as well, showing partial convergence of online and offline processes for the validation of world-knowledge inconsistent information (Rapp & Mensink, Citation2011). Wertgen et al. (Citation2021) extended this research by including an intermediate condition of somewhat implausible but not clearly world-knowledge inconsistent assertions. Otherwise, the design of the experiment was the same as the design used by Wertgen and Richter (Citation2020). Reading times increased and plausibility decreased from knowledge-consistent to implausible to knowledge-inconsistent assertions. Moreover, interactions of source credibility and plausibility were found for reading times of spillover sentences and plausibility judgments, indicating that source credibility and plausibility are jointly considered in validation. High-credible sources increased the plausibility of somewhat implausible assertions but exacerbated the perceived implausibility of knowledge-inconsistent assertion. A corresponding interactive pattern was found for the reading times of the spillover sentences. Thus, the effects of source credibility on implicit validation processes and explicit plausibility judgments seems to depend on the degree of implausibility.

Rationale of the present experiments

The present research examined the interplay of source credibility and plausibility in short multiple documents embedded in a social media context. The impact of source credibility on text comprehension has been investigated primarily in the context of multiple documents comprehension, and few studies have investigated the interplay of source credibility and plausibility in the validation of information (e.g. Salmerón et al., Citation2016). We constructed short messages and presented these in an authentic, Twitter-like setting. Twitter is a popular microblogging social media network that is famous for short messages (tweets). These messages often convey political or socioscientific contents (Maireder & Ausserhofer, Citation2014). In tweets, message and source information are displayed together. With these features, Twitter seems like an ideal environment for the experimental and ecologically valid study of interactions of source credibility and message plausibility.

In two experiments based on within-subjects designs, we varied plausibility of the messages either by manipulating text-belief consistency (Experiment 1) or world-knowledge consistency (Experiment 2). We also manipulated source credibility, more specifically trustworthiness, in two different ways. In Experiment 1, we varied whether the source expresses an authentic, trustworthy message that fits their known argumentative positions (e.g. The oil company Shell supporting the claim of natural causes of climate change) or not (e.g. The oil company Shell supporting the claim of man-made causes of climate change). Hence, readers could infer the trustworthiness of the source based on the consistency between the expressed message and their typical argumentative position. In Experiment 2, we varied the trustworthiness of the source by using high- versus low-reputable media sources (e.g. high-quality vs. yellow-press/tabloid newspapers) for the Twitter messages. The construction of text materials, the selection of sources and the manipulations of plausibility and source credibility were based on separate norming studies for sources and texts with independent samples of participants.

We collected reading times as an implicit online indicator for validation processes. Longer reading times for belief-inconsistent or implausible information are usually interpreted as indicating that the inconsistency has been detected, which slows down processing. In a separate run, we asked the same participants who first read the messages for comprehension to read them again and explicitly judge the presented tweets with regard to plausibility and source credibility. Using both kinds of data allow a better understanding of online and offline processes during reading, particularly by determining the extent that indicators of validation during reading and offline judgments of the plausibility of text information converge (Rapp & Mensink, Citation2011).

Based on the existing research examining the combined effects of source credibility and plausibility (Braasch et al., Citation2012; Foy et al., Citation2017; Wertgen et al., Citation2021; Wertgen & Richter, Citation2020), our general assumption was that both aspects, plausibility and source credibility (i.e. trustworthiness), are considered for validation (see for all Hypotheses). In Experiment 1, we expected main effects of plausibility and trustworthiness (i.e. source-message consistency) on the online and offline indicators of validation. Thus, in line with previous studies that found a disruptive effect of belief-inconsistent or implausible information (e.g. Maier et al., Citation2018; Wertgen et al., Citation2021; Wertgen & Richter, Citation2020), readers were expected to take longer for reading belief-inconsistent texts compared to belief-consistent texts (Hypothesis 1.1). Validation processes are assumed to be unrestricted and can be built on the broader discourse context as well (e.g. O’Brien & Cook, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Thus, salient contextual information about the source’s untrustworthiness based on an inconsistency of source and message should have a similar disruptive effect on reading and lead to longer reading times than messages from trustworthy sources (e.g. message-consistent sources; Hypothesis 1.2). Moreover, readers might especially consider the trustworthiness of the source when they are confronted with belief-inconsistent information, attempting to resolve the inconsistency (as posited by the D-ISC assumption, Braasch et al., Citation2012). Learning that the belief-inconsistent information comes from an authentic, trustworthy source that is known for advocating this position allows for a resolution of the conflict, but learning that the information comes from an unauthentic, untrustworthy source that usually stands for a different position allows for no resolution. This latter scenario might instead increase the conflict and hence the reading time. Therefore, the predicted effect of trustworthiness might be even larger for belief-inconsistent messages, which would amount to an ordinal interaction of the two independent variables. We examined this possibility as an open research question (Open Research Question 1).

Table 1. Overview of all hypothesised effects of Experiment 1 and 2.

For the explicit plausibility ratings, we expected a main effect of text-belief consistency (Hypothesis 1.3) that mirrors its predicted effect on reading times. This hypothesis may be construed as a kind of manipulation check. Starting with the definition of plausibility by Connell and Keane (Citation2006), we assumed that readers base their judgments of plausibility primarily on the fit of the tweets with their beliefs. However, trustworthiness in the sense of source-message consistency might also affect the perceived plausibility of the message. In particular, we expected messages from trustworthy sources to be evaluated as more plausible than messages from untrustworthy sources (Hypothesis 1.4). Again, the latter effect might be even more pronounced in belief-inconsistent messages that, according to the D-ISC hypothesis, should increase the likelihood that readers consider source information in their judgments. We examined this possibility as an open research question (Open Research Question 2). Finally, we expected ratings of source credibility to be higher for trustworthy sources (Hypothesis 1.5). This comparison served as a manipulation check for trustworthiness in Experiment 1.

In Experiment 2, a slightly different pattern was expected, given the different operationalisation of trustworthiness. We expected a main effect of plausibility (operationalised as world-knowledge consistency) on the reading times and the plausibility ratings (Hypothesis 2.1 and 2.3). However, trustworthiness (operationalised as reputation of media sources) was expected to interact with plausibility. Readers were expected to take longer for implausible texts presented by trustworthy sources (Hypothesis 2.2) compared to a matching combination of implausible texts presented by untrustworthy sources (see Wertgen & Richter, Citation2020). Similarly, plausible statements from a trustworthy source might be judged as even more plausible, whereas implausible statements might be judged as even more implausible when coming from a trustworthy source. Thus, we expected an interaction of plausibility and credibility for the explicit plausibility ratings (Hypothesis 2.4). Finally, as a manipulation check, we used the credibility ratings to test whether the trustworthy sources were judged as more credible than the untrustworthy sources (Hypothesis 2.5).

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 investigated the effects of plausibility, operationalised as text-belief consistency, and trustworthiness, operationalised as source-message consistency, on reading times and explicit ratings of plausibility and source credibility.

Method

Participants

We recruited 64 participants with an average age of 25.39 years (SD = 7.52 years). Most of them were university students (84.38%) and female (82.81%). Eleven participants reported a first language other than German (five participants) or a bilingual background (six participants). Participants received 13 Euros or study credit for participation.

Materials

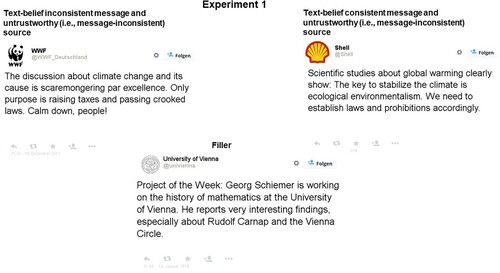

We created 64 short texts about four socioscientific, controversial topics. The filler and experimental texts (the original German versions and English translations) are available in the online supplementary material. The topics were vaccination, anthropogenic versus natural causes of climate change, the use of digital media in educational contexts and the use of glyphosate as an herbicide. For every topic, 16 texts were created, 8 arguing for one position and 8 arguing for the opposite position in the controversy. We combined the texts with matching and non-matching sources associated with either one of the argumentative positions in the controversy. All items were designed in the style of Twitter messages (tweets). Each tweet consisted of a small profile picture in the upper left corner, the text, the name of the source, the Twitter short name of the source and a date and time. The Twitter short name of the source, date and time were typeset in a lighter grey. The profile picture was that of the original Twitter account of the source or we chose an authentic alternative if no profile picture was available. Sources were media outlets (e.g. Fox News), companies (e.g. Monsanto, Shell), foundations or other non-profit organisations (e.g. World Health Organization, Greenpeace), ministries (e.g. Bavarian ministry of education), professional organisations (e.g. German organisation of the automobile industry), political parties (e.g. the German green party), or public persons (e.g. Donald Trump). Additionally, all tweets had the typical features such as a “like” and a “share” button (see for examples). The length of the texts between topics varied within the limits set by Twitter (max. 280 characters), but the lengths (in characters) of the texts within a topic were very similar (glyphosate: M = 206.50, SD = 10.63; vaccination: M = 201.88, SD = 7.03; climate change: M = 195.06, SD = 9.08; digital media: M = 214.31, SD = 11.82). We also created 64 filler tweets about uncontroversial topics (e.g. concerts), of similar length (M = 203.48, SD = 11.75).

We conducted two post hoc norming studies to assess how students perceive the messages and the sources used in the experimental texts independently. Belief-consistent texts (M = 3.74, SE = 0.09) were judged as more plausible compared with belief-inconsistent texts (M = 2.83, SE = 0.09), t(55.4) = 8.33, p < .001, d = 0.83. Sources associated with a belief-consistent message (M = 3.27, SE = 0.09) were judged as more credible compared with sources associated with a belief-inconsistent message (M = 2.44, SE = 0.09), t(125) = 5.74, p < .001, d = 0.81. These findings suggest that the manipulation of plausibility and source credibility was successful. For a full description and results of the post hoc norming studies as well as descriptions of the used sources, see the online supplemental material.

Prior beliefs

Participants’ prior beliefs were assessed approximately one week before the experiment took place. Participants judged the likelihood that a statement is true on a scale from 0 to 100%. We used 10 items for each of the four topics, with five items stating a pro stance and five items stating a contra stance. We used the statements for the topics vaccination and climate change from Maier and Richter (Citation2013). The internal consistencies were satisfactory (glyphosate: Cronbach’s α = .91, climate change: Cronbach’s α = .89, vaccination: Cronbach’s α = .92, digital media in education: Cronbach’s α = .87).

Procedure

Participants were tested in groups of up to eight at a time. The experiment consisted of two parts. All participants gave informed consent. In the first part, we instructed participants to read the tweets carefully and for comprehension because they would later answer a comprehension task to some of the read tweets. All participants read 64 experimental and 64 filler tweets on a computer screen in a self-paced fashion and in randomised order. The experimental software was Inquisit 5 (Millisecond Software, Citation2016). A fixation cross was presented for 500 ms before every trial. After every filler tweet, participants judged whether a statement in the tweet was true or false by pressing “d” or “k”. Half of the statements required “true” as an answer. For example, the filler tweet () required the verification of the statement “Georg Schiemer’s research focuses on different mathematicians” (the correct response would be “true”). None of the questions required specific prior knowledge but could be answered based on the information communicated in the tweets. After the reading task, participants could take a short break. In the second part, we instructed participants to rate either plausibility on a scale from 1 ( = “not plausible at all”) to 7 ( = “very plausible”) or source credibility from 1 ( = “not credible at all”) to 7 ( = “very credible”). To this end, participants saw the same 64 experimental tweets again in a randomised order. Finally, participants provided sociodemographic data and were compensated for their participation.

Design

The design was a 2 (text-belief consistency: belief-consistent vs. inconsistent) × 2 (trustworthiness: trustworthy vs. untrustworthy) within-subjects design. All participants read the texts in the first part of the experiment. In the second part participants were split into two groups, half of the participants provided plausibility ratings for the tweets, the other half provided ratings of source credibility for the Twitter accounts posting the tweet. Two item lists ensured a counterbalanced assignment of tweets to experimental conditions across participants.

Results and discussion

We conducted linear mixed models with the lmer function of the R package lme4 Version 1.1-23 (Bates et al., Citation2015) for all linear mixed models (Baayen et al., Citation2008) and used the emmeans function in the emmeans package (Version 1.4,7; Lenth, Citation2016) for follow-up tests to interpret interactions. The Type I error probability was set at .05 (two-tailed) in all significance tests unless stated otherwise.

Participants and items were entered as random effects (random intercepts) in the models. Including topic as an additional random explained only very small proportions of variance and did not change the effects of interest. Therefore, topic was not included in the analyses to keep the models parsimonious (but see the online supplemental material for the results of the models including topic). The main effects of the two contrast-coded independent variables and their interaction were entered as fixed effects in the models. Belief-consistent messages were coded as 1 and belief-inconsistent messages were coded as −1. Trustworthy sources were coded as 1 and untrustworthy sources were coded as −1. The position in the experiment and the character count of a tweet were entered in the model as centred predictors. Reading times were log-transformed for analyses and contrasts were back-transformed from their logarithmic model estimates and are reported in milliseconds.

We estimated effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for differences in condition means based on the approximate formula proposed by Westfall et al. (Citation2014) for linear mixed models with contrast codes and tests with df = 1 (see also Judd et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, we conducted a post-hoc sensitivity analysis of the effects based on the method proposed by Westfall et al. (Citation2014)., As implemented in the accompanying web-based app (https://jakewestfall.shinyapps.io/crossedpower/). For the post-hoc sensitivity analysis, we used the standardised variance components of the random effect of participants (0.07), the random effect of items (0.05) and the residual variance (0.88) taken from the corresponding linear mixed model (source credibility ratings of Experiment 1). All other variance components were assumed to be 0 because the random intercept of participants and stories were the only random effects in the model. With the given sample size of 31 participants and 64 tweets for source credibility ratings of Experiment 1, effects of d = 0.099 or higher could be detected with a power (1-β) of .90 and a Type I error probability of .05.

Tables with means and standard deviations as well as tables with the estimated means and standard errors of the three dependent variables are available in the online supplemental material.

Prior beliefs

The distributions of prior beliefs differed between topics, but most participants agreed more with one side of the debate (i.e. the majority position). The average agreement was 73.59% (SD = 16.68%) for the position that the herbicide glyphosate is more toxic than beneficial, 76.64% (SD = 15.98%) for the position that climate change is due to anthropogenic causes, 74.94% (SD = 21.07%) for the position that vaccination is more beneficial than harmful and 62.50% (SD = 15.86%) for the position that digital media is beneficial rather than harmful in educational contexts.

Data cleaning of reading times

We examined reading times on a millisecond level. Thus, data of non-native speakers (eleven participants; 704 data points, 17.19% of data) and data of participants with less than 65% accuracy in the reading comprehension task (four participants; 256 data points, 6.25% of data) were excluded from analysis. To ensure a clear-cut manipulation of text-belief consistency, we excluded data from participants with less than 50% agreement to the majority position (see Prior Beliefs section) for the corresponding topic (400 data points, 9.77% of data). Moreover, reading times (per character) outside the interval defined by ±3 SD from the item mean of the log-transformed reading times were treated as outliers (76 data points, 1.86% of data). The final sample consisted of 49 participants with a mean accuracy of 79.37% (SD = 6.49%) on the comprehension task.

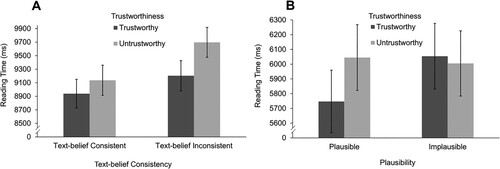

Reading times

provides estimates and significance tests of the fixed effects. We expected a main effect of text-belief consistency, with longer reading times for belief-inconsistent messages compared with belief-consistent messages (Hypothesis 1.1). A significant main effect of text-belief consistency emerged, β = −0.027, t(62) = −2.30, p = .025, d = −0.13. In support of Hypothesis 1.1, participants read belief-consistent messages (M = 8,927 ms, SE = 346 ms) faster than belief-inconsistent messages (M = 9,416 ms, SE = 365 ms). Apparently, participants used their prior beliefs to evaluate the tweets, resulting in slower validation processes for belief-inconsistent information as indicated by longer reading times.

Table 2. Estimated coefficients, standard errors, degrees of freedom, and t values for the linear mixed model of the reading times in Experiment 1.

Likewise, we predicted that varying trustworthiness in form of source-message consistency might elicit longer reading times for messages presented by untrustworthy (i.e. message-inconsistent) sources compared with trustworthy (i.e. message-consistent sources; Hypothesis 1.2). Analysis revealed a significant main effect of trustworthiness that supports Hypothesis 1.2, β = −0.019, t(2,636) = −3.18, p = .001, d = −0.09. Untrustworthy sources (M = 9,344 ms, SE = 350 ms) led to longer reading times compared with trustworthy sources (M = 8,996 ms, SE = 337 ms). An inconsistency of a source and message seems to produce a comparable disruptive effect on reading times as a text-belief inconsistency, which suggests that readers additionally considered trustworthiness for validation.

In addition to the expected main effects of text-belief consistency and trustworthiness, we explored the extent that reading times of belief-inconsistent messages could be modulated by source credibility as posited by the D-ISC assumption (Braasch et al., Citation2012) in our Open Research Question 1. In particular, we assumed a matching pair of a belief-inconsistent message by an authentic, trustworthy source could resolve the text-belief inconsistency by attributing it to the source, whereas a belief-inconsistent text by an unauthentic, untrustworthy source would not allow a resolution. Hence, reading times of belief-inconsistent messages by a trustworthy source should be faster compared with an untrustworthy source. Analysis revealed no significant interaction effect of text-belief consistency and trustworthiness, β = 0.003, t(2638) = 0.48, p = .630 (A). To understand the effects of trustworthiness better, we ran exploratory comparisons of trustworthy vs. untrustworthy sources for belief-consistent and belief-inconsistent messages with adjusted p-values based on the Holm–Bonferroni procedure. The comparison for trustworthiness within belief-inconsistent messages was significant, t(2638) = −2.58, p = .02, d = −0.11. Readers were faster to process a belief-inconsistent message when it was presented by a trustworthy source (M = 9,213 ms, SE = 366 ms) compared with a belief-inconsistent message by an untrustworthy source (M = 9,623 ms, SE = 382 ms). Interestingly trustworthiness seemed to also affect reading times of belief-consistent messages. The comparison between belief-consistent messages was significant, t(2637) = −1.91, p = .028 (one-tailed), d = −0.08. Belief-consistent messages by a trustworthy source (M = 8,785 ms, SE = 348 ms) were read faster compared with an untrustworthy source (M = 9,072 ms, SE = 360 ms).

Figure 2. Mean reading times with ±1 standard error of Experiment 1 and 2 by experimental condition.

Finally, two control variables, the item position in the experiment and the text length, had significant effects on reading times. Participants read longer texts more slowly and later presented tweets faster.

In sum, the results show that text-belief consistency and trustworthiness are both considered for validation of tweets about socioscientific topics during moment-by-moment processing, with processing advantages for belief-consistent texts and matching trustworthy sources. Moreover, the results can be interpreted in light of the D-ISC assumption (Braasch et al., Citation2012), which predicts extended processing effort on source information for readers confronted with discrepant or inconsistent information. Thus, readers possibly took longer to process belief-inconsistent tweets presented by an untrustworthy source in an attempt to dissolve the belief-inconsistency, whereas belief-inconsistent tweets presented by an authentic, trustworthy source led to faster reading times, possibly because the belief-inconsistent information could be easily attributed to the source. Note, however, that this interpretation must be seen with caution given that the corresponding interaction effect was not significant, and an effect of trustworthiness was also found for belief-consistent tweets. Apparently, readers also considered this specific type of source credibility when the message was consistent with their beliefs.

Plausibility and source credibility ratings

Data from participants with a prior belief score of less than 50% agreement were excluded (for plausibility ratings: 224 data points, 10.61%; source credibility ratings: 208 data points, 10.48%). Separate analyses of plausibility and source credibility ratings without data from nonnative participants and from participants with a low performance on comprehension questions (analog to the exclusion criteria for the reading-time data) elicited no substantial differences in results (see online supplemental material for the analyses). Thus, we excluded no data from the analyses of plausibility and source credibility ratings based on these criteria. Plausibility ratings were available from 33 participants and source credibility ratings from 31 participants.

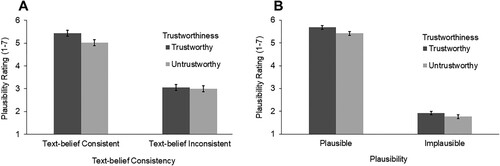

Plausibility Ratings. provides estimates and significance tests of the fixed effects. We expected participants to judge belief-consistent messages as more plausible compared with belief-inconsistent messages (Hypothesis 1.3). In support of this hypothesis, we found a strong main effect of text-belief consistency on plausibility ratings, β = 1.10, t(61) = 14.41, p < .001, d = 1.36. Belief-consistent messages (M = 5.23, SE = 0.12) were judged as more plausible as belief-inconsistent messages (M = 3.03, SE = 0.12). Participants used the consistency of their belief with the position of the text as a major criterion for their plausibility judgments, which can be seen as an extended manipulation check of plausibility.

Table 3. Estimated coefficients, standard errors, degrees of freedom, and t values for the linear mixed model of the plausibility ratings in Experiment 1.

Similarly, we expected a main effect of trustworthiness with higher plausibility ratings for messages by trustworthy sources compared with untrustworthy sources (Hypothesis 1.4). In support of this hypothesis, participants judged messages as slightly more plausible when presented by a trustworthy source (M = 4.24, SE = 0.10) compared with an untrustworthy source (M = 4.01, SE = 0.10), β = 0.12, t(1797) = 3.32, p < .001, d = 0.14. Apparently, sources that made authentic statements that fit with their known argumentative position also increased the plausibility of the Twitter messages.

Following the D-ISC assumption (Braasch et al., Citation2012), we explored whether the trustworthiness effect might be more pronounced in belief-inconsistent messages because readers might increase their attention to source information based on the inconsistency (Open Research Question 2). The analysis revealed a significant interaction effect of text-belief consistency and trustworthiness (A), β = 0.09, t(1797) = 2.57, p = .010. Unexpectedly, no significant difference in plausibility ratings emerged between belief-inconsistent messages presented by a trustworthy source (M = 3.05, SE = 0.13) compared with an untrustworthy source (M = 3.00, SE = 0.13), t(1799) = −0.53, p = .593. Apparently, trustworthiness was not considered when explicitly evaluating the plausibility of belief-inconsistent tweets, possibly because the belief-inconsistent tweets were implausible based on the conflict with participants’ beliefs. Interestingly, the perceived plausibility of belief-consistent messages was boosted when it came from a trustworthy source (M = 5.43, SE = 0.13) compared with an untrustworthy source (M = 5.02, SE = 0.13), t(1799) = 4.17, p < .001, d = 0.25.

Figure 3. Mean plausibility ratings with ±1 standard error of Experiment 1 and 2 by experimental condition.

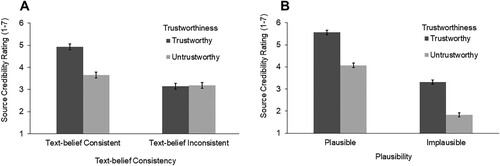

Source Credibility Ratings. A similar pattern of results emerged for source credibility ratings (A). The analysis revealed the main effect of trustworthiness predicted in Hypothesis 1.5. Trustworthy sources received higher source credibility ratings (M = 4.04, SE = 0.11) compared with untrustworthy sources (M = 3.42, SE = 0.11), β = 0.31, t(1684) = 7.97, p < .001, d = 0.36. Thus, the manipulation of source credibility via trustworthiness (i.e. source-message consistency) was successful.

Figure 4. Mean source credibility ratings with ±1 standard error of Experiment 1 and 2 by experimental condition.

Interestingly, the analysis revealed a significant main effect of text-belief consistency, β = 0.57, t(62) = 9.06, p < .001, d = 0.65. Belief-consistent messages led to higher source credibility ratings (M = 4.30, SE = 0.12) than belief-inconsistent messages (M = 3.16, SE = 0.12). Moreover, these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction effect, β = 0.33, t(1684) = 7.97, p < .001. A combination of belief-consistent messages and trustworthy sources led to higher source credibility ratings (M = 4.93, SE = 0.13) compared with a belief-consistent message by an untrustworthy source (M = 3.66, SE = 0.13), t(1683) = 11.57, p < .001, d = 0.73. We found no significant difference in source credibility ratings for belief-inconsistent messages stated by a trustworthy compared with an untrustworthy source, β = −0.03, t(1683.39) = −0.31, p = .754. Again, the item position in the experiment was significant, β = −0.10, t(1720) = −2.52, p = .011. Later presented tweets led to slightly lower source credibility ratings.

Experiment 1 investigated the extent that plausibility and trustworthiness are considered in the validation of socioscientific controversial texts embedded in a social media context. In support of the Hypotheses 1.1 and 1.3, belief-consistent texts were read faster and judged as more plausible compared with belief-inconsistent texts. This finding is in line with research on the text-belief consistency effect that shows processing advantages for belief-consistent information (e.g. Maier et al., Citation2018; Wolfe et al., Citation2013). Similarly, texts by trustworthy sources were read faster and judged as more plausible compared with untrustworthy sources (e.g. Lombardi et al., Citation2014), supporting Hypotheses 1.2 and 1.4. The latter effect of trustworthiness might be more pronounced in belief-inconsistent texts because a detected inconsistency potentially triggers readers to contemplate source information more (D-ISC assumption, Braasch et al., Citation2012), which we examined in our open research questions (Open Research Questions 1 and 2). No interaction effect emerged for reading times. However, exploratory comparisons revealed significant differences with faster reading times for belief-inconsistent texts by a trustworthy compared with an untrustworthy source. Likewise, a belief-consistent text by a matching, trustworthy source elicited faster reading times than an untrustworthy source. This finding is important as it suggests that source credibility is already considered in the integration phase of the comprehension process. Moreover, we found an interaction effect of text-belief consistency and trustworthiness for plausibility ratings in support of this interpretation. Finally, our manipulation check of source credibility was supported (Hypothesis 1.5). Participants judged trustworthy sources as significantly more credible compared with untrustworthy sources.

To conclude, convergent implicit and explicit indicators of validation suggest that trustworthiness and text-belief consistency are both considered in the validation of tweets. The results can be interpreted in terms of theories on validation, especially the large effects of text-belief consistency on reading times and plausibility ratings (Richter & Maier, Citation2017). They are also partly coherent with theories that highlight the role of source credibility in the online processing and evaluation of information from multiple sources such as the D-ISC assumption (Braasch et al., Citation2012; Braasch & Bråten, Citation2017).

However, validation processes are not only based on readers’ prior beliefs but also on world knowledge (Richter, Citation2015). Moreover, source aspects differ within social media contexts and the evaluation of trustworthiness may therefore be based on multiple aspects (e.g. the reputation of a source). Hence, a fruitful approach to further investigate the effects of trustworthiness and plausibility on validation of texts in a social media context would be to vary world-knowledge consistency and source reputation of tweets. This approach was pursued in Experiment 2.

Experiment 2

We conducted Experiment 2 to further investigate the extent that plausibility and trustworthiness are considered in validation. Plausibility was manipulated via the consistency of text information with world knowledge. Trustworthiness was manipulated via the reputation of high- versus low-reputable media outlets. As in Experiment 1, reading times, plausibility and source credibility ratings were the dependent variables, but the current experiment included a different manipulation of trustworthiness with partly divergent Hypotheses. We expected main effects of plausibility on reading times (Hypothesis 2.1) and plausibility ratings (Hypothesis 2.3) with longer reading times and lower plausibility ratings for implausible compared with plausible tweets. However, unlike in Experiment 1, we expected plausibility and trustworthiness to interact on implicit and explicit indicators of validation. Reading times of implausible tweets from trustworthy sources should be longer compared with untrustworthy sources (Hypothesis 2.2). We also expected higher plausibility judgments for plausible texts from trustworthy sources compared with untrustworthy sources. Conversely, implausible tweets from trustworthy sources should be rated as less plausible compared with untrustworthy sources (Hypothesis 2.4). As a manipulation check, we expected source credibility ratings to be higher for trustworthy sources compared with untrustworthy sources (Hypothesis 2.5).

Method

Participants

Seventy-two participants with an average age of 26.61 years (SD = 7.47 years) took part in the experiment and received study credit or 7 Euros for participation. Most participants were female (76.39%), university students (83.33%) and reported German as a first language (84.72%).

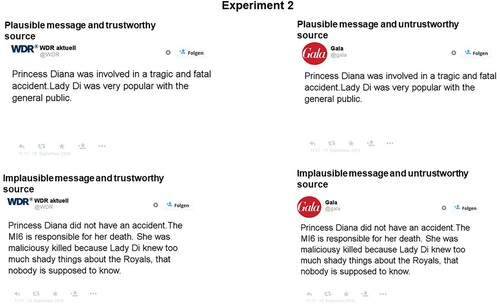

Materials

We created 40 tweets with four versions each () based on a pilot study (N = 25). Every tweet was available in a plausible and an implausible version and combined with a trustworthy or untrustworthy source. Sources were journalistic channels that vary in their reputation such as (online) newspapers (e.g. The Sun, Zeit Online), public (e.g. WDR) or private television broadcasts (e.g. RTL II), radio stations (e.g. Radio NDR) or other print media (e.g. Gala, Vice). Some texts had elements of famous conspiracy theories (e.g. the moon landing was fake). Fifty-six filler tweets from Experiment 1 were used. Translated and original experimental texts, a description and the results of the pilot study and descriptions of the media sources are available in the online supplementary material. We assessed the Locus of Control (Kovaleva et al., Citation2012) and the Generic Conspiracy Belief Scale (Brotherton et al., Citation2013) to control for possible affinities to conspiracy theories and for exploratory reasons. We did not include results for the two scales in the article because they are irrelevant for the hypotheses and had no significant influence on hypothesis-relevant results. For descriptions and results of the two scales, see the online supplemental material.

Design

The design was a 2 (plausibility: plausible vs. implausible) x 2 (trustworthiness: trustworthy vs. untrustworthy) within-subjects design. Four lists assured the counterbalanced assignment of tweets to experimental conditions across participants.

Procedure

Participants were tested in groups of up to eight at a time. All participants gave informed consent. First, participants completed the IE-4, the GCBS, and a socio-demographic survey. Afterwards, we instructed participants to read as naturally as possible and in a way that they will comprehend the tweets. Participants read all 96 tweets in a randomised order and self-paced fashion on a computer screen. The procedure was mostly identical to Experiment 1. The only deviation was that participants rated plausibility (“how would you judge the plausibility of this text?”) and source credibility (“how would you judge the credibility of the source (twitter account)?”) of the tweets in separate counterbalanced blocks on a scale from 1 (“not plausible at all” or “not credible at all”) to 7 (“very plausible” or “very credible”). Participants were debriefed and compensated.

Results and discussion

Similar to Experiment 1, we conducted linear mixed models to analyse reading times. The Type I error probability was set at .05 (two-tailed) in all significance tests. Participants and items were entered as random effects (random intercepts) in the models. The main effects and the interaction of the contrast-coded independent variables were entered as fixed effects in the models. Plausible messages were coded as 1 and implausible messages as −1. Trustworthy sources were coded as 1 and untrustworthy sources as −1. The position in the experiment and the character count of an item were entered as centred predictors in the model. Reading times were log-transformed for analyses and contrasts were back-transformed from their logarithmic model estimates and are reported in milliseconds. As in Experiment 1, we estimated effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for differences in condition means and assessed post hoc sensitivity. To this end, we used the corresponding standardised variance components of the linear mixed model for reading times (participants = 0.26, items = 0.08, residual = 0.65) with 40 items and 50 participants. With a power of .90 and a Type I error probability of .05, the model should be able to detect effects of d = 0.087 or higher.

Data cleaning of reading times

As in Experiment 1, data from participants with less than 75% accuracy on the reading comprehension task (11 participants; 440 data points or 15.28% of data) and additionally data from non-native speakers (2 participants; 80 data points or 1.39% of data) were excluded from the analysis. Moreover, reading times (per character) outside the interval defined by ±3 SD from the mean of the log-transformed reading times were treated as outliers (nine data points, 0.31% of the data). The final sample consisted of 50 participants with a mean accuracy of 83.25% (SD = 5.34%) on the comprehension task.

Reading times

provides estimates and significance tests of the fixed effects. We expected a main effect of plausibility with longer reading times of implausible messages compared with plausible messages (Hypothesis 2.1). The main effect failed to reach significance, β = 0.01, t(1923) = 1.57, p = .116. To explore the effects of plausibility further, we performed two post-hoc comparisons with adjusted p-values based on the Holm–Bonferroni procedure. The first comparison was between plausible and implausible tweets from a trustworthy source, the second comparison was between plausible and implausible tweets from an untrustworthy source. Longer reading times emerged for implausible tweets (M = 6,054, SE = 223) compared to plausible tweets (M = 5,747, SE = 212) when they came from a trustworthy source, which partially supports Hypothesis 2.1, t(1917) = −2.55, p = .022, d = −0.13. However, no significant difference occurred in tweets from an untrustworthy source, t(1910) = 0.33, p = .741. Here, reading times of plausible (M = 6,045, SE = 223) and implausible tweets (M = 6,005, SE = 221) were quite similar.

Table 4. Estimated coefficients, standard errors, degrees of freedom, and t values for the linear mixed model of the reading times in Experiment 2.

The analysis also revealed an interaction effect of plausibility and trustworthiness, β = 0.01, t(1901) = 2.04, p = .041 (B). We conducted follow-up analyses to explore whether the pattern underlying the interaction conformed to Hypothesis 2.2, which predicted that reading times for implausible tweets from an untrustworthy source should be faster compared with implausible tweets from a trustworthy source. Unexpectedly, we found no significant difference in reading times of implausible tweets stated by trustworthy (M = 6,054 ms, SE = 223 ms) compared with untrustworthy sources (M = 6,005 ms, SE = 221 ms), t(1903) = 0.40, p = .689. However, plausible tweets coming from trustworthy sources (M = 5,747 ms, SE = 212 ms) elicited faster reading times than plausible tweets from untrustworthy sources (M = 6,045 ms, SE = 223 ms), t(1903) = −2.48, p = .013, d = −0.13. Thus, the pattern of the interaction was not in line with Hypothesis 2.2. It seems that untrustworthy sources might have weakened the plausibility of the plausible tweets during moment-by-moment processing in a way that the sources led to lesser-perceived plausibility and thus to slower validation processes as indicated by longer reading times. Still, the interaction is in line with the general assumption that trustworthiness and plausibility jointly affect the validation of plausible text information early in the comprehension process.

Two control variables, the item position and length, had a significant effect on reading times. Participants read longer texts more slowly and later presented tweets faster.

Plausibility and source credibility ratings

We conducted linear mixed models to analyse plausibility and source credibility ratings. Model specifications were identical to those in the analysis of reading times and separate analyses of plausibility and source credibility ratings without data from nonnative participants and from participants with a low performance on comprehension questions elicited no substantial differences in results (see online supplemental material for the analyses). Thus, we excluded no data from the analyses of plausibility and source credibility ratings. Data from 71 participants was available.

Plausibility Ratings. provides estimates and significance tests of the fixed effects. We expected participants to judge plausible tweets as more plausible compared with implausible tweets (Hypothesis 2.3). In support of Hypothesis 2.3, analysis revealed a large significant main effect of plausibility on plausibility ratings, t(2728.98) = 65.33, p < .001, d = 2.37 (B). Participants rated plausible tweets (M = 5.55, SE = 0.07) as considerably more plausible than implausible tweets (M = 1.84, SE = 0.07). This strong plausibility effect suggests that the manipulation of plausibility was successful. Apparently, participants used the texts’ consistency with world knowledge as a major criterion for their plausibility ratings.

Table 5. Estimated coefficients, standard errors, degrees of freedom, and t values for the linear mixed model of the plausibility ratings in Experiment 2.

Moreover, we expected plausibility and trustworthiness to interact on plausibility ratings (Hypothesis 2.4). Trustworthy sources were expected to increase perceived plausibility of plausible texts and to decrease perceived plausibility of implausible texts. This hypothesis was not supported, indicated by a nonsignificant interaction effect, β = 0.02, t(2727.22) = 0.81, p = .419. Instead, a significant albeit weak main effect of trustworthiness on plausibility ratings emerged, t(2727.22) = 3.76, p < .001, d = 0.14. Tweets from trustworthy sources (M = 3.80, SE = 0.07) led to slightly higher plausibility ratings than from untrustworthy sources (M = 3.59, SE = 0.07). Taken together, the findings with plausibility ratings add to the general assumption that both plausibility and trustworthiness are considered for validation.

Source Credibility Ratings. A comparable pattern occurred for source credibility ratings (B). The main effect of source credibility on source credibility ratings predicted by Hypothesis 2.5 emerged, t(2727) = 23.58, p < .001, d = 0.84. Participants rated source credibility higher for tweets presented by high-credible sources (M = 4.44, SE = 0.08) compared with low-credible sources (M = 2.95, SE = 0.08). Hence, the manipulation of source credibility based on reputation of media outlets was a success. The plausibility of the tweets had an even stronger impact on source credibility ratings, t(2731) = 35.67, p < .001, d = 1.28. Participants rated source credibility higher for plausible tweets (M = 4.82, SE = 0.08) compared with implausible tweets (M = 2.57, SE = 0.08). Interestingly, plausibility affected source credibility ratings in equal proportions, irrespective of the source’s reputation implying that the readers’ ability to assess source credibility independent from the provided information by the source may be limited. Again, no significant interaction effect occurred, β = 0.004, t(2727) = 0.14, p = .89.

Experiment 2 examined the extent that plausibility and source credibility (i.e. trustworthiness) are considered in the validation of tweet-like texts. Text plausibility was manipulated via world-knowledge consistency and trustworthiness was manipulated by using media outlets with a high or low reputation. Unexpectedly, plausibility had no overall effect on reading times, but it interacted with trustworthiness. Plausible tweets were read faster than implausible tweets when these tweets came from a trustworthy source, whereas tweets from untrustworthy sources elicited no significant difference in reading times, irrespective of their plausibility. This interactive pattern provides partial support for Hypothesis 2.1 but differs from the pattern predicted in Hypothesis 2.2, given that untrustworthy sources seem to have slowed down reading in texts inconsistent with world-knowledge, which contrasts previous research based on narrative texts (Wertgen & Richter, Citation2020). In the analysis of offline ratings, plausibility exerted a strong main effect on plausibility ratings, supporting Hypothesis 2.3. We did not find the expected interaction of plausibility and trustworthiness (Hypothesis 2.4) but instead a main effect of trustworthiness. Thus, participants seemed to use the reputation of the media outlets as an independent criterion for judging the plausibility of the tweet-like messages.

General discussion

The present study examined the general assumption that plausibility and source credibility (i.e. trustworthiness) are considered in the validation of text information embedded in a social media context. In two experiments, participants read Twitter-like messages with varying plausibility and trustworthiness. We used reading times as an online indicator of validation and plausibility judgments as an offline indicator in both experiments (Rapp & Mensink, Citation2011). Overall, the present experiments elicited two informative findings.

First, we found strong plausibility effects on reading times and plausibility judgments in Experiment 1 (Hypotheses 1.1 and 1.3). Participants judged belief-consistent texts as more plausible, which is in line with research on the text-belief consistency effect (e.g. Maier et al., Citation2018) and supports the validity of the plausibility manipulation. The findings regarding the reading times in Experiment 1 are also broadly in line with reading-time experiments based on the inconsistency paradigm (e.g. Albrecht & O’Brien, Citation1993; O'Brien & Albrecht, Citation1992). In Experiment 2, no overall effect of plausibility occurred with reading times, a finding that diverged from the expected pattern (Hypothesis 2.1). However, an interaction effect emerged for reading times showing a plausibility effect for plausible versus implausible texts coming from trustworthy sources. Likewise, a strong plausibility effect occurred for plausibility judgments in Experiment 2 (supporting Hypothesis 2.3 and testifying to the validity of the plausibility manipulation). In sum, the partial converging evidence across online and offline validation indicators suggests that the texts’ consistency with participants’ prior beliefs and world knowledge are major criteria for validation during reading and for the explicit plausibility judgments that are fed by the implicit plausibility judgments created by the validation process (Schroeder et al., Citation2008).

Second, we found important evidence for the general assumption that source credibility is also considered in the validation of tweet-like texts in both experiments and even with different manipulations of trustworthiness. In Experiment 1, trustworthy sources raised the perceived plausibility and likewise affected reading times as implicit indicators of validation, as predicted in Hypotheses 1.2 and 1.4. Moreover, we found partial evidence for an interplay of text-belief consistency and trustworthiness on reading times and on plausibility judgments. As exploratory comparisons revealed, participants allocated more time to tweets that contradicted their beliefs when these tweets came from untrustworthy sources compared with trustworthy sources. An authentic, trustworthy source shortened reading times and raised the perceived plausibility for belief-consistent tweets, suggesting that the source’s authenticity was considered for validation in belief-inconsistent and belief-consistent texts alike, though.

In Experiment 2, plausibility was operationalised via the consistency of information with readers’ world knowledge and trustworthiness was operationalised via the reputation of media outlets, which captures an aspect of the trustworthiness dimension that differs from Experiment 1 (Pornpitakpan, Citation2004). We expected plausibility and trustworthiness to interact because readers might expect plausible statements to come from reputable media sources but implausible statements to come from less reputable media sources. Such an interaction effect was partly found for reading times, which were longer for plausible tweets from an untrustworthy source compared with a trustworthy source. For plausibility judgments, the expected interaction did not occur but instead a main effect of trustworthiness emerged as in Experiment 1. In sum, the results from both experiments suggest that plausibility is the main criterion used for the validation of tweet-like messages and ensuing explicit plausibility judgments, but that trustworthiness can be an extra criterion—although the exact way that the two criteria are combined in validation may differ depending on the type of source credibility.

These results are broadly in line with research based on short narratives (Foy et al., Citation2017; Wertgen et al., Citation2021; Wertgen & Richter, Citation2020). This research suggests that source credibility can be regarded as an important contextual information that signals to the reader whether text information conveyed by the source might be believable or not. However, the present experiments focused on the trustworthiness dimension of source credibility and not on the expertise dimension, as in the experiments by Wertgen and Richter. Whether expertise and trustworthiness differ in their potential to affect validation processes is an open question. An evaluation of expertise might be more informative for validation compared with trustworthiness when information veracity is assessed through world knowledge. Nonetheless, Foy et al. (Citation2017) found that trustworthy sources mitigated the implausibility of unlikely (but not impossible) story events. As in Foy et al., participants in Experiment 1 might have deemed the belief-inconsistent texts as somewhat (but not completely) implausible, given their moderate prior beliefs and the relatively high plausibility ratings for the belief-inconsistent texts. For somewhat implausible information, the truth value is difficult to determine and source credibility can function as an additional criterion for validation (Wertgen et al., Citation2021). In Experiment 2, the plausibility manipulation was much stronger. For example, several implausible tweets conveyed conspiracy theories such as the bizarre idea that the earth is flat. Readers were able to reject these grossly implausible texts without considering source credibility (similar to de Pereyra et al., Citation2014).

Source credibility not only affected the validation of belief-inconsistent texts, but also of plausible texts in both experiments, which is at odds with recent research on the role of source credibility in validation (Foy et al., Citation2017; Wertgen et al., Citation2021; Wertgen & Richter, Citation2020). Apparently, untrustworthy sources also disrupted the processing of plausible texts, suggesting that untrustworthy sources signalled readers to adopt a more critical stance. Moreover, although expertise and trustworthiness are the core dimensions of source credibility (Self, Citation2009), McCroskey and Teven (Citation1999) argued that goodwill (i.e. the degree to which a perceiver believes a sender has his or her best interests at heart) may play a role as a third dimension of source credibility. In our experiments, an evaluation of goodwill might have contributed to validation of plausible tweets, as the untrustworthy sources might appear as biased or partisan (Lee, Citation2010). For example, corporations might attempt to improve their reputation by paying a lip service to environmental concerns or by greenwashing (de Vries et al., Citation2015) and yellow press is often linked to unethical journalism (e.g. Sparks, Citation2000).

The source credibility effects on the processing of plausible texts are only partly in line with the D-ISC model, which distinguishes between consistent (e.g. reading plausible texts) and discrepant processing (Braasch & Kessler, Citation2021). Only discrepant processing is assumed to induce attention to source information because readers might try to resolve the discrepancy, whereas consistent processing should move on without disruption. While the original scope of the D-ISC model is based on consistencies and discrepancies of statements rather than on message plausibility, the deviation from the D-ISC model might be caused by the specific operationalizations of source credibility but also by the high salience of source information in the present experiments. Research on multiple documents comprehension often focuses on readers’ strategic use of source information in reading situations in which source information is easily overlooked. Hence, readers need to actively direct their attention to the source (Bråten et al., Citation2018). Likewise, Sparks and Rapp (Citation2011) used text material with more distant and therefore less salient source information and found little evidence for effects of source credibility (see also de Pereyra et al., Citation2014). In contrast to the reading situations used in the present experiments, source information is very salient in a social media setting like Twitter, where the name and often the well-known logo of an organisation are right above the message. Thus, the social media setting employed in the present experiments seems suitable to increase the salience of source credibility and hence the likelihood that it is considered in validation.

The interpretation of the results of our experiments suffers from several limitations. First, the operational definitions of both independent variables, plausibility and source credibility, differed between the two experiments. The specific combinations of plausibility and source credibility manipulations in Experiment 1 and 2 were chosen to maximise ecological validity. However, the divergent results of the two experiments are difficult to pinpoint given that two central aspects of the experiments were changed simultaneously. Future research should aim at a more systematic combination of source credibility and plausibility manipulations and include, for example, the combination of trustworthy vs. untrustworthy sources and true vs. false information. A second limitation is that reading up to 128 experimenter-made texts is a relatively artificial reading situation. Using of a more naturalistic paradigm would allow a more ecologically valid investigation of validation processes in real-world reading situations. However, we have no reason to assume that motivational effects or fatigue biased the focal effects. Additional analyses with text position and its interactions with the independent variables yielded no significant interaction effects with text position and no substantial change in the focal effects (see the online supplemental material for the results). A third limitation is the possibility of sequential effects of reading plus plausibility or source-credibility ratings. For obvious reasons, we could not counterbalance the order of these tasks. Therefore, despite the fact that we included filler materials and pauses between the tasks, we cannot rule out entirely that the reading tasks may have influenced participants in their ensuing plausibility and source credibility ratings. Fourth, future research should cross-validate the findings of the present experiments as the sizes of the effects of trustworthiness were relatively small. This research should also attempt to answer the question of generalizability across different groups of readers. Sourcing intervention research has shown that teenage students, for example, often fail to distinguish between aspects of source credibility without training (e.g. Pérez et al., Citation2018). The university students participating in the present experiments may be more competent in using source information and might even consider this information routinely. Therefore, the effects might look different in teenagers and other groups of readers with lower educational background. Finally, future research could test whether participants respond differently when they are given clear definitions of plausibility and source credibility to ensure that these concepts are understood in the same way by all participants. We did not give any definitions in the present experiments because respondents should respond spontaneously based on their own concepts of plausibility and credibility. But of course, this approach bears the risk that participants respond differently because they have different concepts in mind.

To conclude, the present study adds evidence for the role of prior beliefs in validation during text comprehension. The present experiments provide evidence for the general assumption that plausibility and source credibility (i.e. trustworthiness) are considered in the validation of text information. Plausibility exerted the strongest and most consistent effects, but trustworthiness also affected both the online processing of the messages and the offline plausibility judgments. Apparently, readers use salient cues to the trustworthiness of a source as signals as to whether a message may be deemed believable.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sarah Engel and Theresa Pfingst for their help in constructing stimulus material and collecting data.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest. Parts of the data have been presented at two conferences (61st Tagung experimentell arbeitender Psychologen (TeaP) in London, UK; 29th Annual Meeting of the Society for Text & Discourse (ST&D) in New York City, USA). This research was partly funded by the Human Dynamics Centre (HDC) of the University of Würzburg.

Data availability statement

The experimental texts, data files, and R-scripts for the full and additional analyses are available (https://osf.io/r5bgx/). The reported experiments were not preregistered.

References

- Abendroth, J., Nauroth, P., Richter, T., & Gollwitzer, M. (2022). Non-strategic detection of identity-threatening information: Epistemic validation and identity defense may share a common cognitive basis. PLoS ONE, 17(1), e0261535. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261535

- Albrecht, J. E., & O'Brien, E. J. (1993). Updating a mental model: Maintaining both local and global coherence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 19(5), 1061–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.19.5.1061

- Anmarkrud, Ø, Bråten, I., & Strømsø, H. I. (2014). Multiple-documents literacy: Strategic processing, source awareness, and argumentation when reading multiple conflicting documents. Learning and Individual Differences, 30, 64–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2013.01.007

- Baayen, R. H., Davidson, D. J., & Bates, D. M. (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59(4), 390–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005

- Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

- Braasch, J. L. G., & Bråten, I. (2017). The discrepancy-induced source comprehension (D-ISC) model: Basic assumptions and preliminary evidence. Educational Psychologist, 52(3), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1323219

- Braasch, J. L. G., & Kessler, E. D. (2021). Working toward a theoretical model for source comprehension in everyday discourse. Discourse Processes, 58(5–6), 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2021.1905393

- Braasch, J. L. G., Rouet, J. F., Vibert, N., & Britt, M. A. (2012). Readers’ use of source information in text comprehension. Memory & Cognition, 40(3), 450–465. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13421-011-0160-6

- Bråten, I., Salmerón, L., & Strømsø, H. I. (2016). Who said that? Investigating the plausibility-induced source focusing assumption with Norwegian undergraduate readers. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.07.004

- Bråten, I., Stadtler, M., & Salmerón, L. (2018). The role of sourcing in discourse comprehension. In M. F. Schober, D. N. Rapp, & M. A. Britt (Eds.), Handbook of discourse processes (2nd ed., pp. 141–166). Routledge.

- Bråten, I., Strømsø, H. I., & Britt, M. A. (2009). Trust matters: Examining the role of source evaluation in students’ construction of meaning within and across multiple texts. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(1), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1598/RRQ.44.1.1

- Britt, M. A., Perfetti, C. A., Sandak, R., & Rouet, J. F. (1999). Content integration and source separation in learning from multiple texts. In S. R. Goldman (Ed.), Essays in honor of Tom Trabasso (pp. 209–233). Erlbaum.

- Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 279. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279

- Connell, L., & Keane, M. T. (2006). A model of plausibility. Cognitive Science, 30(1), 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog0000_53

- Cook, A. E., & O’Brien, E. J. (2014). Knowledge activation, integration, and validation during narrative text comprehension. Discourse Processes, 51(1–2), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2013.855107

- de Pereyra, G. d., Britt, M. A., Braasch, J. L. G., & Rouet, J.-F. (2014). Reader’s memory for information sources in simple news stories: Effects of text and task features. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 26(2), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2013.879152