Abstract

Objectives

Care providers are key agents in the lives of individuals with an intellectual disability (ID). The quality of their support can be affected by manifestations of stigma. This scoping review was conducted to explore studies that provide indications of care providers’ stigmatization of people with ID. Methods: A structured search was made in four databases to identify relevant studies in English-language peer-reviewed journals. Records were systematically and independently screened by the researchers. Results: The 40 articles included in this review were mainly conducted in Western countries and used Likert-type self-report measures of explicit attitudes. Stigmatization seemed more distinct concerning people with high support needs. The few studies on public stigma preliminary suggest that staff may also stigmatize people with ID based on other social identities. Regarding the support of structural stigma, staff reported skepticism regarding community inclusion for people with high support needs, and tended to be ambivalent about the protection-or-empowerment balance in the support of people with ID. Possible indications of stigmatization regarding sexuality were found on specific issues, such as self-determination and privacy. Agreement of staff with certain rights did not necessarily lead to staff acting in accordance with such rights. Conclusion: Indications of stigmatization of people with ID by care providers were found. Stigmatizing attitudes might affect the quality of care providers’ support. Potential leads for future interventions concern creating awareness, sharing power, addressing diagnostic overshadowing, and providing explicit policy translations. Directions for future research concern strengthening the methodology of studies and enriching the studied topics.

Most people with an intellectual disability (ID) need life-long support in one or more areas of life (e.g. Wehmeyer et al. Citation2012). This support is, for a significant part, provided by care providers (e.g. support staff) (Sanderson et al. Citation2017) who fulfill a broad range of needs in the lives of people with ID. For example, care providers are a source of emotional and practical support (Giesbers et al. Citation2019, Van Asselt-Goverts et al. Citation2013), can increase possibilities for choice and independence (Channon Citation2014, Felce Citation1998), manage situations of social participation and social roles (Bigby and Wiesel Citation2015, Todd Citation2000), and expand and strengthen social networks of people with ID (Van Asselt-Goverts et al. Citation2014). Thus, care providers are key agents in the lives of individuals with ID and the quality of the support they provide is important (Giesbers et al. Citation2019).

Studies in related care fields have demonstrated that the quality of care provider’s support can be affected by their stigmatization of the group of clients involved. For example, stigmatization by professionals in mental health care has been shown to affect service delivery (e.g. Lauber et al. Citation2006, Van Boekel et al. Citation2013), the recovery of patients (Schomerus et al. Citation2011), and the accuracy of diagnoses (Thornicroft et al. Citation2007). Stigma is an overarching term that refers to problems of knowledge (ignorance), attitude (prejudice), and behavior (discrimination) (Thornicroft et al., Citation2007).

Various reasons have been reported that can explain why care providers may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward their clients. First, care providers are part of the general public. This is a sphere in which stigmatization toward minority groups (including people with ID) is present and forms a subtle barrier to social inclusion (for a review: see Scior Citation2011). Therefore, it is possible that care providers, even though working with people with ID, may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward people with ID (e.g. having similar concerns regarding the vulnerability of people with ID as the general public reports). Likewise, stigmatization toward people with ID was found within mainstream health professionals (Pelleboer-Gunnink et al. Citation2017). Moreover, care providers may especially have more intense and more frequent contact with people with the highest support needs. Such clinician bias may lead to a more pessimistic view on people’s life chances (e.g. Thornicroft et al. Citation2007, Horsfall et al. Citation2010, Hugo Citation2001). Finally, the tendency to include attitudes and regard in the content of staff training programs is still limited, which may not benefit the awareness and combatting of stigma (Hastings Citation2010, Smidt et al., Citation2009, van Oorsouw et al., Citation2013). Possible stigmatization by care providers is particularly significant when considering that staff are key agents in supporting people with ID to fully participate in society (e.g. Stevens and Harris Citation2017) and to cope with stigmatization (Craig et al. Citation2002).

Two specific forms of stigmatization might be relevant with respect to care providers: (1) public stigma, and (2) structural stigma. Public stigma refers to negative cognitions (e.g. stereotypes) and negative emotions (e.g. prejudice), followed by discriminatory behavior toward people with ID in the general public (e.g. Corrigan and Watson Citation2002, Link and Phelan Citation2001). For example, stereotypes regarding the incompetency to learn new skills (Werner Citation2015, Meppelder et al. Citation2014) may prove a challenge to people with ID who are seeking to enter competitive employment (Skelton and Moore Citation1999). With respect to the second form of stigma, staff can be supportive of social norms and policies that (un-)intentionally restrict opportunities for individuals with ID (i.e. structural stigma) (Corrigan et al. Citation2004). For example, staff members may support social norms (e.g. the belief that people with ID must be protected/sheltered) that may inhibit community inclusion for people with ID (e.g. Venema et al. Citation2015).

In the field of ID, research on stigma is limited, especially concerning care providers. Alternatively, indications of possible stigmatization by care providers might be found in the more prevalent literature on “attitudes” of care providers regarding people with ID. For example, studies on the attitudes of care providers toward community inclusion may provide indications of support of social norms that restrict opportunities for people with ID (i.e. structural stigma) (e.g. Henry et al. Citation2004). This scoping review aims to (i) explore the volume and characteristics of research that may provide indications of possible stigmatization of people with ID by care providers, and (ii) explore the nature of possible stigmatization by care providers (i.e. public stigma and support of structural stigma).

The present article displays the characteristics of a scoping review. Scoping studies still lack a uniform definition, and guidelines for procedure and reporting (Pham et al. Citation2014). Yet, scoping reviews have been described as systematic literature reviews that aim to map primary research in a field of interest in terms of the volume, nature, and characteristics, to provide directions for future research (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). Results are presented following this scoping-review aim due to our broad research question and the highly heterogeneous nature of the available literature (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005, Pham et al. Citation2014).

Method

Search strategy

A structured search was made (January 1994 to April 2017) in four databases (i.e. PubMed, PsychINFO, CINAHL, and ProQuest [i.e. Social Services Abstracts and Sociological Abstracts]) to identify relevant studies in English-language peer-reviewed journals. An update in the two main databases—PubMed and PsychINFO—was performed by the first author in February 2019. Search terms were structured following the PICO approach by specifying a population, intervention/exposure, comparison, and outcome component (Liberati et al. Citation2009). However, for the present study, no comparison component was specified due to the descriptive nature of the research aim. Also, the type of study design was not conditional, since various empirical designs (including qualitative and quantitative studies) could provide relevant information related to the research aim.

The population under study were care providers with direct client contact. This was defined as care providers working for an ID-service provider for whom treatment, care, or support of clients was an important part of their job description (e.g. support staff, direct-care staff, social workers, therapists). Studies were excluded when participants were, for instance, employed as household staff, managers, or directors. “Direct client contact” was assumed to be present based on the participants’ job titles and the context/information provided by each study. In case of uncertainty about the nature of participants’ contacts with clients, the authors of the original article were contacted. When a mix of professionals with and without direct client contact participated in a study (e.g. care providers and managers), either the results of subgroups were reported, or in case no subgroup means were provided, results for the whole group were included, but only when statistical tests had demonstrated no significant differences on the outcome measures between the subgroups. Furthermore, all studies focusing on students were excluded.

Concerning exposure, studies had to focus on people with ID.

The outcome investigated in the studies had to include public stigma (i.e. the cognitive, affective, or behavioral dimensions by which people are viewed or treated as devalued), or structural stigma (i.e. support of social norms and policies that may reduce opportunities for people). Therefore, attitude studies were included when attitudes were reported that are supportive of restrictive social norms or policies (i.e. negative attitudes).

presents an overview of the search terms and strategy applied in PubMed, using medical subject headings (MeSH) and additional text words. Our search strategy was repeatedly tested to reveal which text words were necessary (in addition to the thesaurus terms) in the aim to include all relevant studies. The following text words were added: intellectual disab*, staff, service-provider*, and attitude*. Search strategies similar to the one used in PubMed were applied in the other three databases.

Table 1. Search strategy in PubMed using medical subject headings [MeSH] and text words.

Study selection

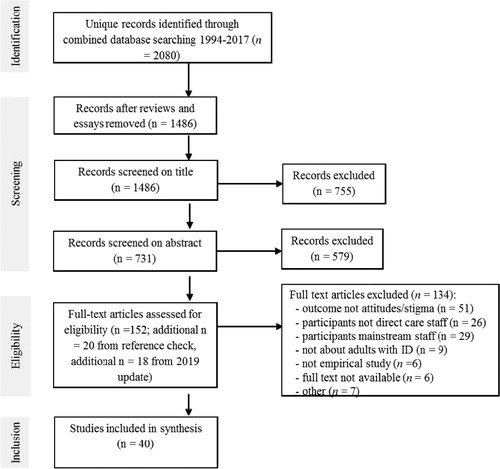

is a flowchart showing the process of identifying and selecting relevant studies.

In the identification phase, records were identified in four databases; then, during screening, duplicates, essays, and reviews were excluded. Next, the remaining records were independently screened on title by two reviewers (HP and PE, WvO or JvW) using the inclusion criteria (). When all inclusion criteria were met, or when there was uncertainty about an inclusion criterion, the records were retained; this strategy resulted in 84% inter-rater agreement. Full consensus on inclusion or exclusion was reached through discussion between the reviewers. Then, abstracts were independently assessed by two reviewers (HP and WvO) based on the exclusion criteria; this resulted in 77% inter-rater agreement. Again, full consensus was reached through discussion between the reviewers. In case of complex decisions, the remaining authors (PE and JvW) were consulted. Full-text articles were assessed on exclusion and inclusion criteria by the first author. Reasons for inclusion or exclusion were then extensively discussed by two reviewers (HP and WvO). In case of lack of clarity about the presence/absence of inclusion/exclusion criteria, the authors of the original article were contacted.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Moreover, the bibliographies of all eligible full-text articles were screened for additional eligible studies. Finally, the quality of studies was assessed using the multi method appraisal tool (MMAT) (Pace et al. Citation2012). This instrument assesses the quality of studies with various research designs, and has demonstrated good content validity and reliability (Pace et al. Citation2012). Appraisal was discussed by a senior researcher WvO (experienced in conducting and supervising systematic reviews) and the first author . Because of the scoping nature of the review, no studies were excluded based on quality (Pham et al., Citation2014). The MMAT quality appraisal format was used to retrieve descriptive quality information about each individual study.

Charting the data

Information on the following items was extracted from the studies: the country of study, study sample, research design and methods, dependent/independent variables, severity of ID, and the methodological strengths/limitations of the studies. In addition, data were extracted on the nature of the possible stigmatization by care providers concerning both structural and public stigma. presents general and methodological information derived from the studies.

Table 3. Main characteristics of the included studies.

Results

This review included 40 articles that reported about 39 studies; the resulting information is presented below in a narrative form (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). The main results are divided into (1) general characteristics of the studies, (2) methodological characteristics, (3) possible moderators of stigma, and (4) reported indications concerning the nature of stigmatization (i.e. both public stigma and support of structural stigma). Concerning the latter part (i.e. the nature of stigmatization), the support of structural stigma is described in the most detail because most studies addressed support of structural stigma and few reported on public stigma.

General characteristics of the studies

Countries

Studies were mainly conducted in Western countries: that is, in the UK (n = 13), Australia (n = 7), USA (n = 5), the Netherlands (n = 3), Ireland (n = 2), Canada (n = 2), and Israel (n = 2). Single studies were found in Greece, Belgium, Poland, and Italy. Two studies were conducted in non-Western countries, namely Pakistan and Japan. In two of the studies, comparisons were made between two countries, which are Japan and USA, and Israel and USA, respectively.

Participants and setting

In most studies, care providers with direct client contact comprised support staff (n = 30). In the remaining studies, participants were specialized ID nurses (n = 3), specialized ID speech and language therapists (n = 1), social workers (n = 1), or a combination of different specialized ID care providers (n = 4). Studies were mainly conducted in a combination of different settings (e.g. day care, outpatient treatment, and residential services) (n = 14), or in an unspecified setting (e.g. client and community services) (n = 11). Qualitative studies mostly described the setting of a community group home (n = 4 out of 7 studies).

Methodological characteristics

Concerning the critical appraisal of the included studies, provides methodological strengths and limitations for each individual study. Following, trends in methodological strengths and limitations are described.

Designs and sampling

Quantitative, cross-sectional designs were mostly used (n = 26), but also descriptive (n = 4), qualitative (n = 8), and mixed method (n = 1) designs were applied. Sampling in quantitative studies was mostly selective using convenience or opportunity samples (n = 21), whereby several studies sampled within one service organization (n = 9 studies). Response rates were not always reported, or were relatively limited (<60%). Only within five studies a (stratified) random sampling procedure was followed. In qualitative studies, three studies used a purposive sample, and three studies presented no inclusion criteria and/or self-selection into the sample (). Thus, the sampling strategy used within studies in this field of research has significant limitations.

Measures

With the exception of three studies, two of which employed semantic differential scales (Harris and Brady Citation1995, Parchomiuk Citation2012) and the other a repertory grid technique (Hare et al. Citation2012), all quantitative studies used Likert-scale self-report measures of explicit attitudes. Most measures did not specifically aim to capture stigmatization, but tended to address general attitudes. Although some validated outcome measures were used (e.g. CLAS-ID; SMRAI), most studies used self-developed questionnaires and reported only on Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of internal consistency of the measure, but no other indicators of reliability (e.g. test-retest reliability) were described. Regarding qualitative studies, semi-structured interviews (n = 3), focus groups (n = 2), open-ended questions (n = 1), and observations with additional interviews (n = 1) were used.

Independent variables: possible moderators of stigmatization

In cross-sectional studies, mainly demographic variables (e.g. gender, age, and education) were examined as moderators of attitudes; in most studies, these demographic variables were not related to stigmatization. Moreover, a minority of studies examined job-related variables, such as work setting, professional role, and prior contact with people with ID. Finally, three studies examined structural relations between attitudes and other outcome variables (i.e. value preference, burnout levels, social norms, effort to facilitate inclusion, experienced competencies, role identity, and meta-evaluations) (Tartakovsky et al. Citation2013, Venema et al. Citation2015, Citation2016).

Prior personal contact

Within stigma research, the contact hypothesis is prominent and states that becoming more familiar with a minority group relates to less stigmatization, especially when contact takes place under positive conditions (Allport Citation1954, Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006). Therefore, in this review we have looked into the evidence base for this hypothesis within the population of care providers. First, support staff in the included qualitative study by Golding and Rose (Citation2015), reported that prior to working in the ID field, they felt that they were stigmatizing people with ID by believing that (i) people with ID “did not have the ability to be independent and were like ‘vegetables’,” and that (ii) that they were too scared to speak to them; however, these beliefs positively changed when they started working (i.e. becoming familiar) with individuals with ID (Golding and Rose, Citation2015). Yet, care providers already working in the ID field will inevitably be familiar with people with ID to some extent. Therefore, three studies have assessed care providers’ familiarity/contact with people with ID within care providers’ personal lives, and one study addressed the quality of contact they reported with people with ID. One study found that care providers’ regular contact with individuals with ID in their personal life was associated with more willingness to have contact with a group of people with ID living in their neighborhood (McConkey and Truesdale Citation2000). Yet, having a friend or family member with a disability was not significantly related to attitudes toward inclusion (Patka et al. Citation2013), and only concerning the subscale self-control related to attitudes toward sexuality (Pebdani, Citation2016). Self-reported quality of contact with persons with ID was not related to attitudes toward sexuality (Murray et al. Citation1995). Thus, having personal contact with people with ID might have positive effects on care provider’s attitudes, however, evidence is still inconclusive.

Severity of ID

Given the diversity in the population of people with ID, it is relevant to examine whether the nature of stigmatization by staff differs according to different levels of impairment. Of the 40 articles in this review, 30 did not provide details on the severity of ID (), in six articles the severity of ID was specified, and in five articles staff outcomes were related to the severity of ID. These comparison studies indicated that higher levels of stigma are found when participants are asked to answer questions regarding individuals with severe ID as compared to those with mild ID. For example, Bigby et al. (Citation2009) demonstrated that, irrespective of a general agreement with principles of choice and inclusion, staff found it difficult to envision that this can be applied to people with severe ID or people with challenging behavior. Moreover, Harris and Brady (Citation1995) reported that people with mild ID were more positively perceived within a relationship (e.g. more kind) than were people with severe ID (e.g. more selfish). Finally, no studies addressed other variables known to influence stigmatization, such as the concealability of the disability, or the degree to which the disability/stigma impedes social interactions.

Table 4. Articles that reported on the level of intellectual disability.

Nature of stigmatization

thematically presents the main outcomes of all individual studies.

Table 5. Overview of themed stigmatizing attitude outcomes

Public stigmatization

Concerning the nature of possible stigmatization, six studies described elements of public stigma by care providers (e.g. stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination). These studies mainly discussed the presence of stereotypical perceptions of people with ID (n = 5). For example, Hare et al. (Citation2012) examined how care providers perceive clients with ID who show challenging behavior. They concluded that the team of care providers did not hold a collective or stereotyped view of their clients, but showed a high degree of variability in how they construe their clients (Hare et al. Citation2012). Besides the relatively positive finding of non-stereotypical perceptions in this study from the UK, other studies indicated the presence of stereotypical views of people with ID. For example, Kordoutis et al. (Citation1995) described clear stereotyping and segregation attitudes in a very specific situation in the Leros asylum in Greece. In that situation, a three-year deinstitutionalization and rehabilitation pilot-intervention project was implemented due to the appalling conditions at the asylum: residents suffered severe deprivation, extreme institutionalization, and violation of basic human rights (see, Tsiantis et al. Citation2000). In those deprived situations, people with ID were, for example, viewed as “unhappy,” and as if “they cannot manage even their simplest needs” (Kordoutis et al. Citation1995). Moreover, when focusing on particular stereotypes regarding “people with ID being in a relationship,” people with mild ID were viewed more favorably (e.g. kindly, truthful or confident) than those with severe ID (e.g. more selfish, false, shy) (Harris and Brady Citation1995).

In addition to stereotypes regarding ID, staff may have stereotypical perceptions of people with ID based on other social identities. For example, Lee and Kiemle (Citation2015) suggested, based on their findings that, in case of comorbidity of both a personality disorder and ID, the complexity of the personality disorder seemed to minimize the relevance of ID. Staff, for example, mainly attributed negative traits (like “unpredictable,” “insecure,” “self-centred,” “lacking in empathy”) to the personality disorder and not the ID of their clients. Also, Maes and Van Puyenbroeck (Citation2008) demonstrated that some staff members held stereotypical attitudes toward elderly patients with ID based on ageist assumptions (e.g. people should have the opportunity to slow down and be inactive), that may limit the range of opportunities that are offered to older people with ID.

Only the study by McConkey and Truesdale (Citation2000) did not focus on cognitive aspects of public stigma but on staff’s behavioral intentions. The authors found that care providers did not differ from mainstream nurses in terms of the amount of contact they had with people with ID in their personal lives, as well as their willingness to engage in social contact with people with ID.

In summary, studies concerning public stigma were scarce and mainly focused on the cognitive aspects of stigma (i.e. stereotypes). Evidence was found for the presence of both stereotypical and non-stereotypical views on people with ID among care providers. In addition, based on two studies, there is preliminary evidence that care providers may hold stereotypical views on people with ID based on other social identities, such as personality disorders or being elderly. Regarding behavioral intentions, specialized ID care providers appeared not to differ from mainstream nurses.

Structural stigma

The largest number of studies (n = 33) provided indications of the support of structural stigma. Regarding the focus of these studies, two issues were prominent, namely community inclusion and sexuality. In addition, three studies (as presented within four articles) addressed the attitudes of care providers to processes of decision-making by people with ID and being informed and involved, and finally, one article reported on human-rights knowledge of staff (Redman et al. Citation2012).

First, within articles addressing community inclusion (n = 14), in a general sense, this inclusion was valued as important for people with ID (Doody et al. Citation2013, Golding and Rose Citation2015). For example, in the study by Golding and Rose (Citation2015), care providers were generally positive about integration and believed that both the individual with ID and society would gain from integration. Moreover, based on outcomes from the Community Living Attitude Scale (n = 7), care providers showed no desire to exclude people with ID from community life (i.e. in all studies, the subscale “exclusion” received the lowest mean score) and care providers unanimously perceived people with ID as being similar to themselves (in all studies, the highest mean score). For example, Henry et al. (Citation2004) reported on the CLAS (note: in other studies referred to as CLAS-MR or CLAS-ID [Henry et al. Citation1996]) (6-point scale, Mdn = 3.5) low scores on exclusion (M = 1.68) and high scores on similarity (M = 4.81). Similarly, on item level, there was clear consensus on items of the exclusion and similarity subscales (e.g. 95% of staff disagreed that homes/services for people with ID should be kept out of residential neighborhoods [exclusion subscale]; and 93.4% agreed that people with ID have goals for their lives just like other people [similarity subscale]) (Jones et al. Citation2008).

However, care providers had ambivalent attitudes (i.e. scores inclined toward the mean “not agree/not disagree”) toward sheltering (i.e. belief that people must be protected) and empowerment (i.e. support of self-advocacy and empowerment). For example, Henry et al. (Citation2004) reported close to neutral scores on sheltering (M = 3.43) and empowerment (M = 3.97). Jones et al. (Citation2008) showed a similar indecisiveness on item level, (e.g. 23.7% of staff disagreed with the statement that “the opinion of people with ID themselves should carry more weight than those of their family members and professionals,” in decisions affecting that person [empowerment subscale]); moreover, 48.1% agreed that sheltered workshops for people with ID are essential [sheltering subscale]). Similarly, Golding and Rose (Citation2015) reported that care providers acknowledge being overprotective and concluded that care providers care providers needed to find a balance between protection and empowerment.

Moreover, four of the 14 studies clearly indicated the skepticism of staff with regard to community inclusion. That is, in two Australian studies, care providers working in comparable community-based group homes in one geographical area, doubted the feasibility of the principles of community inclusion, choice, and participation for people with severe/profound ID (Bigby et al. Citation2009, Clement and Bigby Citation2009). Reasons for non-feasibility were, for example, that the implementation of such principles would make no difference for people with severe ID, that people are too different, or that they are not ready for inclusion (Bigby et al. Citation2009). Moreover, Venema et al. (Citation2015, Citation2016) conducted two studies in the Netherlands with care providers working in a reversed integration setting (i.e., a setting in which people without an ID purposefully choose to live next to people with an ID). In these studies, conducted in one geographical area with staff working with people with high support needs, staff held relatively negative attitudes toward integration. They mentioned several perceived disadvantages of integration, such as the possibility of a decreased freedom of movement compared to residential areas. That is: “In contrast to the residential facility, in the reversed integration setting there were “regular” traffic movements and because the clients were unfamiliar with the traffic rules, they were not allowed to go outside on their own anymore.” Moreover, staff assumed that neighbors in a reversed integration setting held less positive social norms regarding integration than the neighbors themselves actually held (Venema et al. Citation2016). Similarly, Golding and Rose (Citation2015) reported that, when specifically asked, care providers discussed potential harms to society by integrating people with ID in the community such as physical harm, or feeling intimidated and frightened. Moreover, Clement and Bigby (Citation2009) reported that activities for people with ID guided by care providers were focused on community presence, not participation.

Thus, concerning community inclusion, care providers seem to hold a generally positive attitude. When looking for possible support of social norms and policies that restrict opportunities for people with ID (stigma), there are indications that care providers judge community inclusion to be less feasible for specific groups of people with ID (i.e. those with behavioral or psychiatric problems, and people with severe/profound ID) (Bigby et al. Citation2009, Venema et al. Citation2015). Moreover, there was a tendency for care providers to be ambivalent about whether people with ID should be protected or empowered (e.g. Golding and Rose, Citation2015).

Second, studies concerning possible structural stigma related to the sexuality and parenthood of people with ID (n = 14) focused on a large variety of aspects, such as sexual rights, masturbation, intercourse, sexual education, marriage, relationships, homosexuality, and parenthood. Attitudes of staff were mainly discussed as being either liberal or conservative, with most results being interpreted as (moderately) liberal. For example, liberal attitudes referred to the agreement that sexuality is an important aspect of a person’s life and that people with ID have sexual desires similar to those of people without ID (Parkes Citation2006, Christian et al. Citation2002). Nevertheless, care providers seemed to be more positive toward the sexuality of people from the general population than toward the sexuality of people with ID (Gilmore and Chambers Citation2010, Meaney-Tavares and Gavidia-Payne Citation2012). For example, Gilmore and Chambers (Citation2010) demonstrated that, on issues related to access to sexual education, contraception and freedom of sexual expression, care providers saw more freedom as acceptable for women without ID than for women with ID. This relationship was not found for men with and without ID. Also, Christian et al. (Citation2002) demonstrated that liberal attitudes do not necessarily indicate that the support of people with ID regarding sexuality is a high priority. That is, 44% of staff felt that when providing support to women with ID, there were more important priorities to focus on than sexuality (Christian et al. Citation2002).

Concerning homosexual relationships and parenthood, care providers seemed to hold more ambiguous views. Care providers expressed uncertainty about how to deal with homosexual relationships compared to heterosexual relationships (Yool et al. Citation2003) and were less positive about parenthood compared to other aspects of sexuality (Gilmore and Chambers Citation2010, Cuskelly and Bryde Citation2004). Moreover, some staff members seemed to support restrictions related to mandatory HIV testing (44% of staff agreed with mandatory testing for people with ID) (Murray et al. Citation1995). Additionally, care providers seemed to hold ambiguous attitudes toward both privacy and self-determination in terms of sexuality. For instance, about 25% of the care providers were not sure whether people with ID should be allowed to have unsupervised relationships, or whether to inform parents about their adult child’s intimate relationships (Evans et al. Citation2009). Finally, intimate relationships were viewed as less acceptable for people with severe compared to mild ID (Evans et al. Citation2009, Harris and Brady Citation1995); moreover, care providers deemed the individual’s level of understanding as relevant to the acceptability of sexual relationships, as well as involvement in decisions about the individual’s own sexuality (Christian et al. Citation2002, Yool et al. Citation2003).

In summary, sexuality was a prominent theme and staff seemed to hold mostly liberal attitudes toward sexuality of people with ID, although some restrictive or ambiguous attitudes were present. Indications of possible stigmatization were found regarding homosexuality, parenthood, the priority of sexuality in support, privacy, and self-determination concerning sexuality.

Finally, a Dutch study [(Bekkema et al. Citation2014, Citation2015)], an Australian (Wiese et al. Citation2013), and a British one (Crook et al. Citation2016) examined staff attitudes, as well as their behavior related to processes of decision-making and being informed and involved. It was demonstrated that agreement with certain social norms/human rights did not automatically lead to staff following-up on such rights. That is, care providers were highly likely to believe that clients’ wishes should always be leading in terms of decisions about the place of end-of-life care and they believed this more so than ID physicians and general practitioners. Nevertheless, in the end, only 8% of the respondents reported the wishes of the client as an actual consideration in the decision about the place of end-of-life care (Bekkema et al. Citation2015). Similarly, although staff working with elderly people with ID felt that people with ID have the right to know about dying, clients were hardly ever engaged in this topic (Wiese et al. Citation2013). Also, clinicians feel that people with ID should not be excluded from research. Yet, a suspicion of research intentions, or not perceiving immediate of direct benefits for a client, can prevent clinicians from allowing people with ID to participate in research (Crook et al. Citation2016). Moreover, in medical decision-making, the wishes/preferences of people with mild/moderate ID were taken into account more often (27.8%) than the wishes/preferences of people with severe/profound ID (2.9%) (Bekkema et al. Citation2014).

Discussion

This scoping review was systematically conducted to identify studies that may address possible stigmatization by care providers toward people with an ID. The aim was to provide an overview of these studies in terms of general characteristics, methodology used, moderators of stigma, and indications concerning the nature of the stigmatization.

Given the ubiquity of stigmatization, it seems especially relevant to address stigmatization in relation to care providers who have direct client contact. Obtained knowledge may help care providers to enact their key role in the lives of people with ID. Stigmatization was conceptualized as either public stigma (i.e. stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination) or support of structural stigma (i.e. social norms and policies that restrict opportunities for people with ID). Due to the lack of research on stigma in the field of ID, our exploration of possible stigmatization by care providers included the more prevalent literature on “attitudes” and related concepts (e.g. beliefs). However, because these studies did not explicitly aim to address stigmatization, any interpretations regarding possible stigmatization of staff should be made with caution.

The 40 studies included in the review were mainly conducted in Western countries, with care providers working either in unspecified ID settings or a variety of different settings (e.g. day care, residential). A minority of studies considered care providers other than support staff (e.g. therapists, nurses, or social workers), the majority of studies focused on support staff. Studies mostly did not differentiate between varying levels of ID. Most studies used self-report Likert-type measures of explicit attitudes; this has been reported before by, for example, Antonak and Livneh (Citation2000). Several studies were conducted in a forensic setting, which might have colored the experiences and perceptions of staff working in these specialized institutions. For example, staff’s perceptions may have been influenced by clients’ criminal behavior and the environmental/procedural restraints of the secure setting, as well as their ID.

Studies related to public stigma were scarce. Two studies showed that care providers may stigmatize people with ID based on other social identities (e.g. in case of comorbidity, a person’s personality disorder was found to be more strongly stigmatized than the person’s ID). This issue of intersecting identities may need further research, especially considering the fact that an ID is often viewed as a dominant social identity (e.g. Beart et al. Citation2005, Logeswaran et al., Citation2019). Concerning the presence of stereotypical perceptions of people with ID, both the presence and absence of stereotypes were demonstrated. All studies (except for one on behavior/behavioral intentions) focused on cognitive aspects of public stigma. Studies on the possible support of structural stigma mainly focused on aspects of community inclusion, sexuality, and parenthood. Of note, some alternative, current, and relevant themes were scarce (e.g. decision-making, or being informed) or even missing (e.g. employment and social networks).

There was skepticism regarding the feasibility of community inclusion for clients with high support needs. Care providers tended to be ambivalent about whether people with ID should be protected or empowered. This finding is specifically relevant, given the fact that people with an ID have reported experiences of over-protection, lack of recognition, and dependence on support as important expressions of stigmatizing treatment (e.g. Jahoda and Markova Citation2004, Jahoda et al. Citation2010, Giesbers et al. Citation2019). Possible indications of stigmatization regarding sexuality were found on issues related to parenthood, homosexual relationships, priority of supporting sexuality, sexuality-related privacy, and self-determination; these issues may warrant more research into possible support of structural stigma. Furthermore, stigmatization seemed to be related to subgroups of people with ID and appeared to be the strongest for people with severe/profound ID, and people with high support needs (including people with challenging behavior, or comorbid psychiatric diagnoses). Finally, agreement of staff with certain rights, such as (informed) decision-making, did not necessarily lead to staff acting in accordance with such rights.

Implications for clinical practice

Due to the key role of care providers, their continuous training and coaching in maintaining high-quality levels of support is essential. Based on the present results, attention for the potential presence and influence of stigmatizing attitudes on the quality of care providers’ support seems needed. The tendency to include care providers’ attitudes in the content of staff training programs is however, still limited in the field of ID (Hastings Citation2010, Smidt et al. Citation2009, Van Oorsouw et al. Citation2013). Comparably, in the field of mental illness, interventions that address stigmatization by mental health professionals are also uncommon (Thornicroft et al. Citation2016). The few interventions that were found in the field of mental illness, concerned information-based approaches that resulted in short-term improvements in knowledge and behavior (Thornicroft et al. Citation2016). Therefore, a first step may be to raise awareness concerning the relevance of stigmatization and attitudes in the context of services that are provided to people with ID (Embregts Citation2011, Pijnenborg et al. Citation2016, United Nations Citation2006).

There is, however, limited evidence concerning what might follow this first step to raise awareness. In all healthcare fields, the question what might constitute effective elements of training that can reduce stigmatization of care providers are hardly explored. Yet, leads for future development of interventions can, for example, be derived from the general reference point that stigmatization can only exist in a context of power difference (Goffman Citation1963, Link and Phelan Citation2001). Given the inevitable power difference that does exist in the relationship between care provider and service user (client), it seems important that care providers are willing to share their power (e.g. by shared-decision making) and to listen carefully to clients and their families/network (Douglas and Bigby Citation2018, Pijnenborg et al. Citation2016). This may reduce the demonstrated risk on over-protection and limited involvement in decision-making for people with ID. For this purpose, out of many possibilities, the approach of experience-based co-design might, for example, be useful (e.g. Bate and Robert Citation2006), because it facilitates the exchange of experiences between service users and care providers with the aim to improve the quality of services. Also, working together with experts-by-experience in individual support questions of service users toward more independence, may prove specifically helpful because of its empowering function (Pijnenborg et al. Citation2016).

A second lead for future development of interventions, concerns the potential risk on diagnostic overshadowing which is often related to stigmatization (e.g. Evans‐lacko et al., Citation2010). Diagnostic overshadowing concerns a tendency to overlook symptoms of mental health or physical problems and attribute them to being part of “having an intellectual disability” (Mason and Scior, Citation2004, Werner et al., Citation2013). Care providers (e.g. support staff) in the field of ID often have a signaling function of mental and physical health symptoms toward health professionals and may therefore contribute to diagnostic overshadowing by overlooking relevant symptoms. In staff coaching, the advices regarding diagnostics in relation to stigmatization as made by Pijnenborg et al. (Citation2016) may prove relevant: (1) try to place symptoms in a normalizing framework, (2) do not insist on people accepting the diagnosis (of ID/personality disorder), but validate emotions and symptoms, (3), do not stress biomedical factors in discussing a client’s diagnosis but stress the potential to improve and learn.

A final implication concerning what support staff may need to maintain high quality levels of support, was found within studies concerning attitudes toward community inclusion. Two of these studies demonstrated that support staff struggle to interpret the meaning of broad and often not specifically defined policy principles (e.g. community inclusion) or display uncertainty in terms of how to apply such principles to specific groups of people (e.g. people with severe ID) (Bigby et al. Citation2009, Clement and Bigby Citation2009). Therefore, staff may need explicit, practical information regarding policy principles concerning human rights, possibly in combination with on-the-job coaching to convey latest knowledge to the daily support of individual clients (Van Oorsouw et al. Citation2009).

Implications for research

Concerning future research, studies on staff’s expression of public stigma are currently limited in both number and scope. Addressing not only cognitions, but also emotions and behavior of staff, may provide directions for staff training. Moreover, studies on staff’s support of structural stigma have mainly focused on sexuality and community inclusion, while other issues are scarcely represented. For example, Stevens and Harris (Citation2017) indicate that attitudes of care providers are pivotal in creating a positive (or negative) climate when supporting people to get and keep jobs (Stevens and Harris Citation2017). Future research into staff’s possible support of restrictive social norms regarding employment may prove to be a fruitful effort to improve an individual’s opportunity for employment. Additionally, several other issues, such as friendships, social networks, self-determination, valued leisure activities, or physical health, may also benefit from this focus (e.g. Wong and Wong Citation2008).

Related to methodology, mostly Likert-type self-report studies or qualitative thematic studies into explicit attitudes were employed. Future observation studies or proxy reports can have the additional potential to address behavioral presentations of stigma that care providers may not be aware of or either may not be willing to report. Moreover, given the complex nature of the process of stigmatization, it seems meager that only Likert scales are used to assess internal processes. Numerous alternatives to Likert-type scales have been described (e.g. q-methodology, adjective checklists, rankings, socio-metrics, qualitative methods) that may increase the validity of the conclusions drawn from existing studies (Antonak and Livneh Citation2000, Haddock and Zanna Citation1998). Moreover, to obviate the threats of validity inherent to explicit measures of stigma/attitudes (e.g. social desirability bias, generosity effect), implicit methods such as the quantitative implicit association test, qualitative causal layered analysis, may prove valuable (Antonak and Livneh Citation2000, Dorozenko et al. Citation2015). Finally, most studies did not differentiate between subgroups of people with ID. Given the large diversity within the total group of people with ID, and the indications that stigma might vary for different subgroups of people with ID, future studies might benefit from using vignettes or examining real-life situations to explore the impact of (for example) the concealability of ID, or the amount of deviant behavior on stigmatization by care providers.

The present study has some limitations. The exclusion of gray literature and studies published in languages other than English may have caused a bias toward significant results and information from specific regions of the world. Also, as this review covers research from around the world the recommendations are generic. Therefore, some issues may be of local concern rather than a widespread issue and might need further exploration in local conditions. Finally, this study focused on care providers as participants of studies. Future review study might focus on the reports of clients and relatives about their care providers’ attitudes to complete the picture.

Conclusion

Care providers are key agents in supporting people with ID to achieve valuable life goals. To provide high-quality support, staff should receive training not only to improve the level of their knowledge and skills, but also to address the possible presence of stigmatization. It is of foremost importance to raise awareness of the relevance of stigmatization in the context of services provided to people with ID. Moreover, care providers should be encouraged to share power with people with ID and their families, for example, in working together with experts-by-experience. Also, the accurate use of diagnostic information is relevant to prevent diagnostic overshadowing. More studies on public stigma may provide new directions for staff training regarding stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. Preferably, future studies into support of structural stigma among care providers, should address a wider range of life domains (e.g. employment).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allport, G. W. 1954. The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Antonak, F. R., and Livneh, H. 2000. Measurement of attitudes towards persons with disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22, 211–224.

- Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. 2005. Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–25.

- Bate, P., and Robert, G. 2006. Experience-based design: From redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 15, 307–310.

- Bazzo G., Nota, L., Soresi, S., Ferrari, L., and Minnes, P. 2007. Attitudes of social service providers towards the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 20, 110–115.

- Beart, S., Hardy, G., and Buchan, L. 2005. How People with Intellectual Disabilities View Their Social Identity: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 18, 47–56.

- Bekkema, N., de Veer, A. J. E., Wagemans, A. M. A., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., and Francke, A. L. 2014. Decision making about medical interventions in the end-of-life care of people with intellectual disabilities: A national survey of the considerations and beliefs of GPs, ID physicians and care staff. Patient Education and Counselling, 96, 204–209.

- Bekkema, N., de Veer, A. J. E., Wagemans, A. M. A., Hertogh, C. M. P. M., and Francke, A. L. 2015. To move or not to move: A national survey among professionals on beliefs and considerations about the place of end-of-life care for people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59, 226–237.

- Bigby, C., Clement, T., Mansell, J., and Beadle-Brown, J. 2009. “It’s pretty hard with our ones, they can’t talk, the more able bodied can participate”: Staff attitudes about the applicability of disability policies to people with severe and profound intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53, 363–76.

- Bigby, C., and Wiesel, I. 2015. Mediating community participation: Practice of support workers in initiating, facilitating or disrupting encounters between people with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 28, 307–318.

- Channon, A. 2014. Intellectual disability and activity engagement: Exploring the literature from an occupational perspective. Journal of Occupational Science, 21, 443–458.

- Christian, L. A., Stinson, J., and Dotson, L. A. 2002. Staff values regarding the sexual expression of women with developmental disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 19, 283–291.

- Clement, T., and Bigby, C. 2009. Breaking out of a distinct social space: Reflections on supporting community participation for people with severe and profound intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 264–275.

- Corrigan, P., Markowitz, F., and Watson, A. 2004. Structural levels of mental illness stigma and discrimination. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30, 481–491.

- Corrigan, P. W., and Watson, A. C. 2002. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 1, 16–20.

- Craig, J., Craig, F., Withers, P., Hatton, C., and Limb, K. 2002. Identity conflict in people with intellectual disabilities: What role do service-providers play in mediating stigma? Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 15, 61–72.

- Crook, B., Tomlins, R., Bancroft, A., and Ogi, L. 2016. “So often they do not get recruited”: Exploring service user and staff perspectives on participation in learning disability research and the barriers that inhibit it. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 44, 130–137.

- Cuskelly, M., and Bryde, R. 2004. Attitudes towards the sexuality of adults with an intellectual disability: Parents, support staff, and a community sample. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29, 255–264.

- Doody, C. M., Markey, K., and Doody, O. 2013. The experiences of registered intellectual disability nurses caring for the older person with intellectual disability. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22, 1112–1123.

- Dorozenko, K. P., Roberts, L. D., and Bishop, B. J. 2015. Imposed identities and limited opportunities: Advocacy agency staff perspectives on the construction of their clients with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 282–299.

- Douglas, J., and Bigby, C. 2018. Development of an evidence-based framework to guide decision making support for people with cognitive impairment due to acquired brain injury or intellectual disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30451022.

- Embregts, P. J. C. M. 2011. Zien, bewogen worden, in beweging komen [Notice, being touched, and coming into action]. Tilburg: Tilburg University.

- Evans, D. S., McGuire, B. E., Healy, E., and Carley, S. N. 2009. Sexuality and personal relationships for people with an intellectual disability. Part II: Staff and family carer perspectives. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 53, 913–921.

- Evans‐lacko, S. Little, K. Meltzer, H. Rose, D. Rhydderch, D. Henderson, C.& Thornicroft, G.2010. Development and psychometric properties of the Mental Health KnowledgeSchedule. La Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie. 55(7) 440–448.

- Felce, D. 1998. The determinants of staff and resident activity in residential services for people with severe intellectual disability: Moving beyond size, building design, location and number of staff. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 23, 103–119.

- Flatt-Fultz, E., and Phillips, L. A. 2012. Empowerment training and direct support professionals’ attitudes about individuals with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 16, 119–125.

- Giesbers, S. A. H., Hendriks, L., Jahoda, A., Hastings, R. P., and Embregts, P. J. C. M. 2019. Living with support: Experiences of people with mild intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32, 446–456.

- Gilmore, L., and Chambers, B. 2010. Intellectual disability and sexuality: Attitudes of disability support staff and leisure industry employees. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 35, 22–8.

- Goffman, E. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. 2nd ed. New York: Prentice-Hall.

- Golding, N. S., and Rose, J. 2015. Exploring the attitudes and knowledge of support workers towards individuals with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 19, 116–129.

- Grieve, A., McLaren, S., Lindsay, W., and Culling, E. 2009. Staff attitudes towards the sexuality of people with learning disabilities: A comparison of different professional groups and residential facilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, 76–84.

- Haddock, G, Zanna M. P. 1998. On the use of open-ended measures to assess attitudinal components. British Journal on Social Psychology, 37, 129–49.

- Hare, D. J., Durand, M., Hendy, S., and Wittkowski, A. 2012. Thinking about challenging behavior: A repertory grid study of inpatient staff beliefs. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 50, 468–478.

- Harper, D. J. 1994. Evaluating a training package for staff working with people with learning disabilities prior to hospital closure. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 78, 45–53.

- Harris, P., and Brady, C. 1995. Attitudes of speech and language therapists to intimate relationships among people with learning difficulties: An exploratory study. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 23, 160–163.

- Hastings, R. P. 2010. Support staff working in intellectual disability services: The importance of relationships and positive experiences. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 35, 207–210.

- Henry, D., Keys, C., Balcazar, F., and Jopp, D. 1996. Attitudes of community-living staff members toward persons with mental retardation, mental illness, and dual diagnosis. Mental Retardation, 34, 367–379.

- Henry, D. B., Duvdevany, I., Keys, C. B., and Balcazar, F. E. 2004. Attitudes of American and Israeli staff toward people with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation, 42, 26–36.

- Holmes, M. 1998. An evaluation of staff attitudes towards the sexual activity of people with learning disabilities. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 61, 111–115.

- Horner-Johnson, W., Keys, C. B., Henry, D., Yamaki, K., Watanabe, K., Oi, F., Fujimura, I., Graham, B. C., and Shimada, H. 2015. Staff attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities in Japan and the United States. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59, 942–947.

- Horsfall, J., Cleary, M., and Hunt, G. E. 2010. Stigma in mental health: Clients and professionals. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31, 450–455.

- Hugo, M. 2001. Mental health professionals’ attitudes towards people who have experienced a mental health disorder. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 8, 419–425.

- Jahoda, A., and Markova, I. 2004. Coping with social stigma: people with intellectual disabilities moving from institutions and family home. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 48, 719–729.

- Jahoda, A., Wilson, A., Stalker, K., and Cairney, A. 2010. Living with stigma and the self-perceptions of people with mild intellectual disabilities. Journal of Social Issues, 66, 521–534.

- Jones, J., Ouellette-Kuntz, H., Vilela, T., and Brown, H. 2008. Attitudes of community developmental services agency staff toward issues of inclusion for individuals with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 5, 219–226.

- Kordoutis, P., Kolaitis, G., Perakis, A., Papanikolopoulou, P., and Tsiantis, J. 1995. Change in care staff attitudes towards people with learning disabilities following intervention at Leros PIKPA Asylum. British Journal of Psychiatry, Supplement, 167(28), 56–69.

- Lauber, C., Nordt, C., Braunschweig, C., and Rössler, W. 2006. Do mental health professionals stigmatize their patients? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113(429), 51–59.

- Lee, A., and Kiemle, G. 2015. “It”s one of the hardest jobs in the world’: The experience and understanding of qualified nurses who work with individuals diagnosed with both learning disability and personality disorder. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 28, 238–248.

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P. J., Kleijnen, J., and Moher, D. 2009. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. British Medical Journal, 339, b2700.

- Link, B. G., and Phelan, J. C. 2001. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 363–385.

- Logeswaran, Sophini. Hollett, Megan. Zala, Sonia. Richardson, Lisa. Scior, Katrina. How do people with intellectual disabilities construct their social identity? A review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2019. 32(3) 533–542. 10.1111/jar.12566.

- Maes, B., and Van Puyenbroeck, J. 2008. Adaptation of Flemish services to accommodate and support the aging of people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 5, 245–252.

- Mason, J.& Scior, K.2004. “Diagnostic Overshadowing” Amongst Clinicians Working with People withIntellectual Disabilities in the UK. Journal of Applied Research in IntellectualDisabilities. 17(2) 85–90.

- McConkey, R., and Truesdale, M. 2000. Reactions of nurses and therapists in mainstream health services to contact with people who have learning disabilities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 158–163.

- Meaney-Tavares, R., and Gavidia-Payne, S. 2012. Staff characteristics and attitudes towards the sexuality of people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 37, 269–273.

- Meppelder, M., Hodes, M. W., Kef, S., and Schuengel, C. 2014. Expecting change: Mindset of staff supporting parents with mild intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35, 3260–8.

- Murray, J. L., and Minnes, P. M. 1994. Staff attitudes towards the sexuality of persons with intellectual disability. Australia and New Zealand Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 19, 45–52.

- Murray, J. L., MacDonald, A. R., and Minnes, P. M. 1995. Staff attitudes towards individuals with learning disabilities and AIDS: The role of attitudes towards client sexuality and the issue of mandatory testing for HIV infection. Mental Handicap Research, 8, 322–332.

- Oliver, M. N., Anthony, A., Leimkuhl, T. T., and Skillman, G. D. 2002. Attitudes toward acceptable socio-sexual behaviors for persons with mental retardation: Implications for normalization and community integration. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 37, 193–201.

- Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jahosh, J., and Seller, R. 2012. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, 47–53.

- Parchomiuk, M. 2012. Specialist and sexuality of individuals with disability. Sexuality and Disability, 30, 407–419.

- Parkes, N. 2006. Sexual issues and people with a learning disability. Learning Disability Practice, 9, 32–37.

- Patka, M., Keys, C. B., Henry, D. B., and McDonald, K. E. 2013. Attitudes of Pakistani community members and staff toward people with intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 118, 32–43.

- Pebdani, R. N. 2016. Attitudes of group home employees towards the sexuality of individuals with intellectual disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 34, 329–339.

- Pelleboer-Gunnink, H. A., Van Oorsouw, W. M. W. J., Van Weeghel, J., and Embregts, P. J. C. M. 2017. Mainstream health professionals’ stigmatising attitudes towards people with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61, 411–434.

- Pettigrew, T. F., and Tropp, L. R. 2006. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 751–783.

- Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., and Mcewen, S. A. 2014. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5, 371–385.

- Pijnenborg, M., Kienhorst, G., van ’t Veer, J., and van Weeghel, J. 2016. Epiloog: Lessen voor de toekomst [Epilogue: Lessons for the future]. In J. van Weeghel, M. Pijnenborg, J. van ’t Veer, and G. Kienhors, eds., Handboek destigmatisering bij psychische aandoeningen: principes, perspectieven en praktijken [Handbook destigmatisation in mental illness: principles, perspectives and practices]. Bussum: Uitgeverij Coutinho, pp.305–322.

- Redman, M., Taylor, E., Furlong, R., Carney, G., and Greenhill, B. 2012. Human rights training: Impact on attitudes and knowledge. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 17, 80–87.

- Sanderson, K. A., Burke, M. M., Urbano, R. C., Arnold, C. K., and Hodapp, R. M. 2017. Who Helps? Characteristics and correlates of informal supporters to adults with disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 122, 492–510.

- Schomerus, G., Corrigan, P. W., Klauer, T., Kuwert, P., Freyberger, H. J., and Lucht, M. 2011. Self-stigma in alcohol dependence: Consequences for drinking-refusal self-efficacy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 114, 12–17.

- Scior, K. 2011. Public awareness, attitudes and beliefs regarding intellectual disability: a systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32, 2164–2182.

- Skelton J., and Moore M. 1999 The role of self-advocacy in work for people with learning difficulties. Community, Work & Family 2, 133–145.

- Smidt, Andy. Balandin, Susan. Sigafoos, Jeff. Reed, Vicki A.. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2009. 34(3) 266–274. 10.1080/13668250903093125.

- Stevens, M., and Harris, J. 2017. Social work support for employment of people with learning disabilities: Findings from the English Jobs First demonstration sites. Journal of Social Work, 17, 167–185.

- Tartakovsky, E., Gafter-Shor, A., and Perelman-Hayim, M. 2013. Staff members of community services for people with intellectual disability and severe mental illness: Values, attitudes, and burnout. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 3807–3821.

- Thornicroft, G., Rose, D., and Kassam, A. 2007. Discrimination in health care against people with mental illness. International Review of Psychiatry, 19, 113–122.

- Thornicroft, G., Mehta, N., Clement, S., Evans-Lacko, S., Doherty, M., Rose, D., Koschorke, M., Shidhaye, R., O'Reilly, C., and Henderson, C. 2016. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. The Lancet, 387, 1123–1132.

- Todd, S. 2000. Working in the public and private domains: staff management of community activities for and the identities of people with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 44, 600–620.

- Tsiantis, J., Diareme, S., and Kolaitis, G. 2000. The Leros PIKPA Asylum, deinstitutionalization and rehabilitation project. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 4, 281–292.

- United Nations. 2006. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Geneva: United Nations.

- Van Asselt-Goverts, A. E., Embregts, P. J. C. M., and Hendriks, A. H. C. 2013. Structural and functional characteristics of the social networks of people with mild intellectual disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 1280–1288.

- Van Asselt-Goverts, A. E., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Hendriks, A. H. C., and Frielink, N. 2014. Experiences of support staff with expanding and strengthening social networks of people with mild intellectual disabilities. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 24, 111–124.

- Van Boekel, L. C., Brouwers, E. P. M., Van Weeghel, J., and Garretsen, H. F. L. 2013. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: Systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 131, 23–35.

- van Oorsouw, Wietske M. W. J..Embregts, Petri J. C. M..Bosman, Anna M. T.. Evaluating staff training: Taking account of interactions between staff and clients with intellectual disability and challenging behaviour. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2013. 38(4) 356–364. 10.3109/13668250.2013.826787.

- Van Oorsouw, W. M. W. J., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Bosman, A. M. T., and Jahoda, A. 2009. Training staff serving clients with intellectual disabilities: A meta-analysis of aspects determining effectiveness. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 503–511.

- Venema, E., Otten, S., and Vlaskamp, C. 2015. The efforts of direct support professionals to facilitate inclusion: The role of psychological determinants and work setting. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 59, 970–979.

- Venema, E., Otten, S., and Vlaskamp, C. 2016. Direct support professionals and reversed integration of people with intellectual disabilities: Impact of attitudes, perceived social norms, and meta-evaluations. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 13, 41–49.

- Wehmeyer, M. L., Davies, D. K., Tassé, M. J., and Stock, S. 2012. Support needs of adults with intellectual disability across domains: The role of technology. Journal of Special Eudcation and Technology, 27, 11–22.

- Werner, S. Stawski, M. Polakiewicz, Y.& Levav, I.2013. Psychiatrists’ knowledge. training andattitudes regarding the care of individuals with intellectual disability.Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 57(8) 774–782.

- Werner, S. 2015. Stigma in the area of intellectual disabilities: Examining a conceptual model of public stigma. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 120, 460–475.

- Wiese, M., Dew, A., Stancliffe, R. J., Howarth, G., and Balandin, S. 2013. “If and when?”: The beliefs and experiences of community living staff in supporting older people with intellectual disability to know about dying. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 57, 980–992.

- Wong, P. K. S., and Wong, D. F. K. 2008. Enhancing staff attitudes, knowledge and skills in supporting the self-determination of adults with intellectual disability in residential settings in Hong Kong: a pretest-posttest comparison group design. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52, 230–43.

- Yazbeck, M., McVilly, K., and Parmenter, T. R. 2004. Attitudes toward people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 15, 97–111.

- Yool, L., Langdon, P. E., and Garner, K. 2003. The attitudes of a medium-secure unit staff toward the sexuality of adults with learning disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 21, 137–149.