Abstract

Background: Infants, children, and youth in foster care have frequently experienced prenatal substance exposure (PSE), neglect, and maltreatment as well as disruptions in their relationships with families. They also have great capacity for overcoming early adversities. In this synthesis of two previously conducted scoping reviews, we aimed to identify and describe literature that identifies a range of interventions that support the health and development of this population.

Methods: This review integrates and extends two previously conducted scoping reviews, one focusing on infants and one focusing on children and youth, to synthesize themes across these developmental stages. The Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology was employed for the current and previous reviews. A three-step search strategy identified published studies in the English language from January 2006 to February 2020.

Results: One-hundred and fifty-three sources were included in this review. Four themes were identified: (1) early screening, diagnosis, and intervention; (2) providing theoretically grounded care; (3) supporting parents and foster care providers; and (4) intersectoral collaboration.

Conclusion:Infants, children, and youth with PSE are overrepresented in foster care. Child welfare system planning should take a multi-sectoral approach to addressing the cumulative needs of this population and their care providers over developmental ages and stages. Although research remains limited, early screening, diagnosis, and developmentally and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder-informed intersectoral interventions are critical for optimizing outcomes.

Providing optimal care and supporting positive outcomes for children from infancy to adolescence requiring foster care has been a challenging area of service delivery within child welfare and appears to remain a major concern in the USA, Canada, and internationally (Fernandez and Delfabbro Citation2021). Infants, children, and youth with prenatal substance exposure (PSE) are a significant cohort in foster care that demonstrates specific health, socio-emotional, educational, and developmental needs. For the purpose of this review, we define the term PSE as ‘fetal exposure to maternal drug and alcohol use that can significantly increase the risk for developmental and neurological disabilities in the child’ (Child Welfare Information Gateway ND) . We employ this broader umbrella term to be inclusive of multiple potential diagnoses resulting from PSE, with two more well-known diagnoses that are neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS, increasingly being called neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, NOWS, Patrick et al. Citation2019) and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD). Research also notes that polysubstance use during pregnancy is the norm, not the exception, with many children exposed to multiple substances, including tobacco, alcohol, and prescription medications (Jarlesnki et al. Citation2020).

It is critical that programs and services for this population are evidence-based, population-oriented, and accounted for in-service delivery models. However, best practice approaches in child welfare are still developing, including in relation to supporting children and families where PSE is a concern (Trocme et al. Citation2016). Research is increasingly highlighting the negative impact of cumulative disadvantage and the importance of long-term supports for children in foster care (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University Citation2016). Thus, the purpose of this scoping review was to integrate two previously conducted scoping reviews, one focusing on infants in care with PSE and one focusing on children and youth in care with PSE, synthesize themes across these developmental stages, and identify and describe a range of interventions for supporting them and their families and caregivers that address the concern of cumulative disadvantage across the life course. Specific research questions addressed in this review included the following:

What are the characteristics of interventions and programs designed to support optimal physical, social-emotional, and cognitive development of infants, children and youth (from birth to 19) who are in foster care with PSE?

What are the characteristics of interventions and programs designed to improve the satisfaction and retention of foster and kinship care providers caring for this population?

What are the gaps for future intervention and program development, research and system and policy mapping for this population?

Background

It is generally recognized that there is a greater likelihood that child protection and foster care services will be involved when families and children are impacted by PSE (American Academy of Pediatrics, Waite et al. Citation2018). Prindle et al. (2017) report that parental substance abuse is a concern in approximately from 11% to 40% of the investigated reports of child maltreatment globally, with rates rising from 16% to 79% in the USA. This wide variation is influenced by reporting and classification processes, state policy context, cultural and ethnic background, and community determinants of health (Faherty et al. Citation2019, Meinhofer et al. Citation2020, Seay Citation2015). The US National Centre on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare (2016) reports that the overwhelming majority of children in foster care now have a parent with a substance use disorder. More recently, the opioid epidemic has contributed to a dramatic doubling in the number of children entering foster care between 2000 and 2017 (Meinhofer et al. Citation2020) .

For infants, PSE is most frequently reported within the context of prenatal opioid exposure and diagnosis of NAS. FASD is more challenging to diagnose before the age of three as currently used tests may not be sensitive to differences at young ages and indicators may be attributed to alternate explanations such as trauma (Hanlon-Dearman et al. 2020). Sanlorenzo et al. (Citation2018) report an evolving epidemiology of NAS in the USA, with variability across states and disproportionate impact in rural areas, among the Medicaid population and across different cultural groups. From 2000 to 2016, the incidence of NAS increased from 1.2 to 8.8 per 1000 hospital births in the USA. Similar increases are noted in other countries (Corsi et al. Citation2020, Davies et al. Citation2016). Consequently, an increase of 10,000 infants was noted from 2011 to 2017 in the US foster care system (Patrick et al. Citation2019). Infants and young children up to the age of five now represent over 41% of children in care.

From a child and youth perspective, PSE within the context of foster care is represented in the literature more commonly as FASD. FASD has been identified as the leading cause of developmental/intellectual disability in Western society and as such has implications for health care, education systems, and social service involvement (Brownell et al. Citation2011). Popova et al. (Citation2019) conducted a global estimate of FASD prevalence and identified children in foster care as a special subpopulation with rates substantially higher than the general population. The pooled prevalence in the USA was noted to be 251.5 per 1000 for children in foster care, compared with 7.7 per 1000 in the global general population. Chasnoff et al. (Citation2015) report that foster and adopted children with PSE are often misdiagnosed along the spectrum or, more frequently, have a missed diagnosis. Although diagnosis before the age of six has been recommended as ideal, in reality assessment services are hard to access and often delayed, thus increasing the risk of adverse outcomes (Benz et al. Citation2009).

Research shows that early intervention and support can improve the course of development in both the short and long term (Olson et al. Citation2007). However, Bertrand (Citation2009) has noted that historically, interventions for children with FASD have been extrapolated from those employed with children with other disabilities and from practical experience. More recently, systematic reviews have been published in relation to interventions for infants with NAS and children and youth with FASD; however, they are not specific to the foster care context (Bertrand, Citation2009, Peadon et al. Citation2009, Reid et al. Citation2015).

A unique opportunity for collaborative research emerged when the two authors of this paper each received funding from different sources to study a similar topic. Marcellus et al. (Citation2017) was interested in studying interventions and programs that supported the development and well-being of infants with PSE in foster care, while Badry (Citation2018) was interested in the same context, but with children and youth. A parallel approach was taken up to develop a shared methodology for each project, allowing for further synthesis of the literature located across both studies. The search strategy described below is a merging and updating of these two scoping reviews. All search processes were identical other than the population of focus, facilitating a developmental analysis from infancy to the time when youth exit foster care, typically at approximately age 19. Currently, no review of the literature exists from this perspective. We have employed the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis-extension for Scoping Reviews) checklist to guide reporting in this article (Tricco et al. 2018).

Materials and methods

A scoping review was chosen as the methodology for this review for three reasons: (1) to provide a broad overview of the field; (2) to report on the types of evidence that address and inform practice in this area; and (3) because scoping reviews are more inclusive of a diverse range of forms of evidence. We employed the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews as described by Aromataris and Munn (Citation2020), as reviewers can draw upon data from any source of evidence and research methodology. The resulting broad review is useful for bringing together evidence from disparate or heterogeneous sources.

Philosophical perspective

The JBI approach to evidence synthesis is drawn from the JBI Model of Evidence-Based Healthcare, where evidence-based care is defined as decision making that considers not only effectiveness but also the ‘real world’ feasibility, appropriateness, and meaningfulness of practices (Jordan et al. Citation2019). Thus, JBI takes a pragmatic stance to inclusion of the diverse forms of evidence used by decision makers. Sensitivity to the practicality and usability of synthesis findings to diverse stakeholders facilitates bridging the gap between researchers and practitioners and adapting findings to different contexts (Hannes and Lockwood Citation2011).

Search strategy

Together, the two scoping reviews considered sources that included foster care situations where infants, children, and youth had been exposed prenatally to substances considered harmful from a child protection perspective. For the purposes of these reviews, substances included tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, crystal methamphetamine, cocaine, opioids, and solvents if used for the purpose of intoxication. Studies were not included if they were related to environmental exposure to substances (food, lead, pollution) or medications used as prescribed by health care providers. The scoping reviews considered quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, and economic studies for inclusion. In addition, literature reviews, policy documents, quality improvement, and program evaluation sources that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved. Gray (unpublished literature) including theses and dissertations were also included if there was not a subsequent publication.

The search strategy in the two previous scoping reviews aimed to find both published and unpublished studies between 2006 and 2016. We originally chose 2006 as the starting point for the previous reviews to capture 10 years of literature following the time when the Canadian FASD Diagnostic Guidelines were first published (Cook et al. 2006). For this integrated synthesis, we replicated and updated the search from January 2017 to February 2020. A three-step search strategy was utilized. In Stage 1, an initial limited search was undertaken to identify the text words contained in the title and abstract of relevant sources, along with the controlled language index terms used to describe the sources. In Stage 2, a second search using these identified keywords and index terms was then conducted across MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsychINFO (see ). The search for relevant gray literature included non-profit and government websites for child welfare and foster parenting. Stage 3 involved a final search of the reference lists of all retrieved publications for additional sources. Only studies published in English were considered for inclusion in this review.

Table 1 Search strategy

Reference software was used to manage the list of all the retrieved citations and all duplicates were removed. If retrieved theses or dissertations were related to a peer-reviewed publication, the theses or dissertations were removed. Articles were then assessed for relevance to the review based on the information provided in the title, abstract, and descriptor/MESH terms by two independent reviewers. When relevance was not clear after this review, the full article was retrieved. Disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. In accordance with the JBI review manual, the sources that were identified during searching for inclusion in this scoping review that were authored by one of the review authors were assessed for inclusion by other reviewers to limit bias.

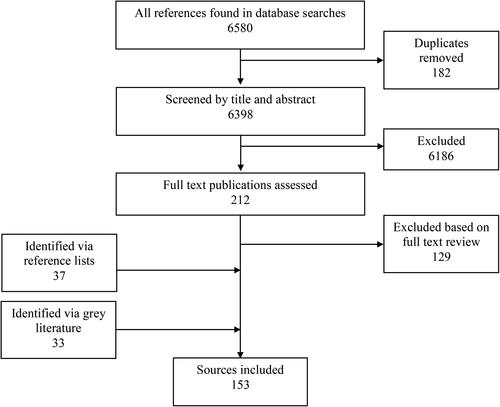

The database searches identified a total of 6580 records. One hundred and eighty-two citations were duplicates and removed. The titles and abstracts for 6398 citations were screened and 212 citations were considered for full-text review. Following this step 83 sources were identified for inclusion. A further 70 sources were identified from reference list review and gray literature. A flowchart showing the number of citations is detailed in . In total, 153 sources are included in this review. Eight of these sources were identified in the final search between January 2017 and February 2020.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from papers included in the scoping review using a data extraction tool developed for this review. The data extracted included specific details about the populations, concept, context, and study methods of significance to the scoping review questions. The draft data extraction tool was iteratively modified and revised as necessary during the process of extracting data from each included study.

Data mapping

Marcellus et al. (Citation2017) and Badry (Citation2018) each previously developed an overview of the included material to December 2016 and summarized findings using tables and figures, which mapped the literature in the two specific developmental areas (infants and children/youth). Literature was tabulated using the following headings: type of source, area of focus/intervention, country of publication, methodology, primary aim of article, sample size and characteristics, key findings, and recommendations for practice, policy, and research.

For this integrated review, we replicated these steps. First, the two datasets were merged alphabetically. Second, data from additional sources from January 2017 to December 2020 were included. Third, the extracted data and literature maps were re-analyzed and a narrative summary and visual map of key themes were developed that represented the full developmental scope of foster care demographics from infancy through to age 19, when youth ‘age out’ of the foster care system. Extracted data are collated in .

Table 2 Extracted data

Results

Source characteristics

Country of publication

The sources included in this review were published in the following six countries: the USA (73), Canada (54), the UK (10), Australia (8), Finland (3), the Netherlands (2), South Africa (2), Norway (2), Israel (1), and France (1). Of note, one of the Australian sources compared child welfare systems in Australia, Canada, Scotland, and the USA. This source was included as Australian as it was published through an Australian institution.

Types of source

The following types of sources were included in this review: quantitative research publications (70), program descriptions (18), qualitative research publications (12), literature reviews (12), educational resources (12), mixed methods research publications (11), expert opinions (11), practice guidelines (3), and non-peer-reviewed reports on research (2).

Quality of sources

Formal appraisal of the quality of sources is not a required component of the JBI scoping review methodology, as it is challenging to compare across different epistemological and methodological traditions (Hong and Pluye Citation2019). Published research included topics such as infant, child and youth mental health, adoption and foster care, health, child development, child psychology, child welfare including child abuse and neglect, developmental disability research, youth work, addictions, justice, and human behavior and emerges from the disciplines of psychology, health, medicine, science, social work, psychiatry, nursing, pediatrics, neuropsychology, neuroscience, developmental disabilities, and occupational therapy. All included gray literature sources were developed by reputable government, research, and policy organizations. Quantitative and mixed methods studies were primarily focused on early screening, diagnosis, and intervention, followed by supporting foster care providers. Qualitative approaches were used primarily to study collaboration and supporting foster care providers. Overall, research studies were appropriately designed.

Key themes

Overall, four broad themes were identified in the literature from infancy through to adolescence, within the broader construct of PSE-informed care: (1) early screening, diagnosis, and intervention; (2) supporting parents and foster care providers; (3) providing theoretically grounded care; and (4) intersectoral collaboration. It is noted that the emphasis in the majority of articles focused on early screening, diagnosis, and intervention, followed by supporting parents, intersectoral collaboration, and finally, providing theoretically grounded care. With a strong emphasis on screening, diagnosis, and intervention in the research, it is recognized that a gap exists in the literature in relation to the work involved in caring for this population including interventions with caregivers, working across systems (intersectoral collaboration), and in relation to models of best practice (theoretically grounded care). As noted above, a number of disciplines are engaged in responding to FASD, yet FASD remains somewhat underrecognized as a developmental disability. provides a map of the themes identified in this review, the infant review, and the children and youth review. Both similarities and differences were noted in themes between the overall developmental approach and age-specific approaches, which are addressed below. Throughout the results, we employ the terminology of the sources. The term ‘children’ is employed in general for the broader group of infants, children, and youth, with specific age categories identified when done so in the sources.

Table 3 Comparison of themes from the three analyses

Early screening, diagnosis, and intervention

Seventy-six of the publications focused on a component of the process of early screening, diagnosis, and intervention. In the infant literature, early screening, diagnosis, and intervention were framed primarily as identifying infants and families at risk of requiring foster care, related to the context of prenatal substance exposure but also to multiple other factors that contributed to circumstances of risk, including poverty, mental health issues, and family violence. In these sources, screening for infants and young children was typically related to identifying safety risks for infants and the need to involve families in the child welfare system, including placing infants in foster care (Brownell et al. Citation2011, Delfabbro et al. Citation2009, Eiden et al. Citation2007, Tonmyr et al. Citation2011). At this early age, the connection to substance use was focused on illicit substances such as opioids and stimulants (cocaine, crystal methamphetamine) and the development of NAS. An FASD diagnosis was usually not reported in infants and young children.

A number of interventions and programs developed specifically for this population were identified, with some publications providing evidence of effectiveness. For infants and young children, interventions were primarily focused on supporting the development of attachment within the context of dysregulation, caregiving challenges, and disruptions in relationships, including the Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up (ABC) intervention (Dozier et al. Citation2013), the Foster Family Intervention (FFI) (Van Andel et al. Citation2016), the New Orleans Intervention Model (Zeanah et al. Citation2011), and the Promoting First Relationships (PFR) intervention (Spieker et al. Citation2012).

In the children and youth literature, early screening, diagnosis, and intervention shifted to a focus on FASD and also concurrent mental health disorders. Early screening and diagnosis for PSE has been identified as a critical first step in the research literature for over two decades (Olson et al. Citation2007, Popova et al. Citation2016), and the importance of secondary prevention via improved diagnosis was advocated for across sources (Reid et al. Citation2015). Diagnosis of FASD in particular at an early age, before six or as early as possible, was widely considered a protective factor in this literature. Diagnosis at this early stage was noted to help children and youth gain access to appropriate resources, including casework planning, educational supports, family supports, counseling, and health services ( Author name [and reference] Badry et al. 2011, Child and Youth Working Group Citation2007, First Nations Child and Family Caring Society & Paukuutit Inuit Women of Canada Citation2006, Taylor et al. n.d).

Although early diagnosis is considered a gold standard practice, the findings of this review indicated that only a small percentage of children and youth with FASD in foster care were able to access diagnostic services, no matter their age. Carmichael Olson (Citation2015) identifies that gold standard practice in FASD diagnosis includes a multi- or interdisciplinary team with specialized knowledge about FASD. There was often reporting of inadequate funding of diagnostic clinics, lack of knowledge and training in diagnosis, lack of funding for diagnostic clinics, and steep economic and time requirements necessary for comprehensive multidisciplinary diagnostic assessments (Badry et al. 2011; Cook et al. 2016, First Nations Child and Family Caring Society & Paukuutit Inuit Women of Canada Citation2006, Watkins et al. Citation2013). Other reported barriers included rural and remote geography and stigma contributing to lack of confirmation of PSE that would support a diagnosis.

Children and youth also may receive concurrent mental health and neurocognitive diagnoses. Children with FASD were noted to have a high rate of co-occurring mental health concerns, which impacted their development (Chasnoff et al. Citation2015). There was a need for mental health services to be tailored to their specific needs and abilities, including intensive therapy to address attachment concerns and behavioral difficulties. Service providers should recognize that children with FASD have a distinct behavior profile and may react differently to the pharmaceutical treatments normally provided mental health and neurocognitive disorders.

Interventions and programs for school-aged children were centered on improving self-regulation and emotional control, remediating problem behavior in classroom settings, supporting cognitive development, and developing skills of daily living. Interventions for self-regulation and emotional control included the ALERT Program and Neurocognitive Habilitation Therapy (Wells et al. Citation2012). Social skills interventions included Children’s Friendship Training (Bertrand Citation2009). Specific cognitive and daily living skills interventions included fire and safety skills (Coles et al. Citation2007), Math Interactive Learning Experience (Kable et al. Citation2007), Language and Literacy Training (Adnams et al. Citation2007), and Rehearsal Training to Improve Working memory (Loomes et al. Citation2008). One intervention was noted for youth, the Youth Outreach Program and was focused on mental health and preparation for transition to adulthood (Hubberstey et al. Citation2014).

Specific areas of focus related to youth were screening, assessment, and diagnosis within the context of correctional and justice programs (Paley et al. 2010) . Suggested improvements in the assessment process that could be made when FASD is suspected included starting evaluation at the earliest point possible when a child first entered into the child welfare system and developing opportunities for juvenile courts to evaluate and treat children and youth who may not yet have a diagnosis (Paley et al. 2010). Because of the steep prevalence of people with FASD in correctional systems (approximately 19 times higher risk for individuals with FASD to be incarcerated), screening needs to be incorporated at the earliest possible point in the criminal justice process (Popova et al. Citation2011).

Providing theoretically grounded care

Theories, approaches, models, and frameworks provide a logical structure for examining current evidence, studying issues, and designing interventions. Theoretical approaches were the focus of 19 articles in this review. The most frequently identified theories in these sources were strengths-based approaches, ecological approaches, culturally appropriate approaches, attachment and trauma-informed care, and developmentally appropriate care.

A key theme across age groups was the importance of child welfare workers and foster parents adopting a strengths-based approach when working with children with PSE. The concept of strengths-based child protection practice emerged over 30 years ago as an appreciative and action-oriented approach to service response that focuses on ‘positive possibilities for helping’ (Cameron and Freymond 2006, p. 348). For health and social services professionals, this approach includes a greater awareness of intergenerational, structural, historical, and political influences on parenting capacity. Paley et al. (2010) suggested that there is a need for more programs and activities to be developed, which focus on and build on children’s strengths and promote positive engagement with the community.

In addition to adopting a strengths-based approach, Morrison and Mishna (Citation2006) argued for an ecological approach where interventions are specifically tailored to the needs of each child and should consider the environmental context. They suggested that there is often a critical need to modify the environment alongside interventions to improve functioning. Ungar et al. (Citation2014) recommended employing an ecological conceptualization of resilience, with the need for services to be developed, which not only promote a child’s individual strengths but achieve systemic change through addressing social disadvantage. One way to do this is to draw on a social determinants of health perspective, being mindful of the effects of poverty, racism, unsafe housing, violence, victimization, and trauma, and how these can impact a child’s development (Hubberstey et al. Citation2014). In a review of research on interventions for people with FASD across the life span, Reid et al. (Citation2015) concluded that ecological or holistic approaches that examine multiple factors can be more effective and have longer lasting benefits.

Although there has been a substantially increased focus in child welfare and health systems on integrating culturally appropriate perspectives into policies, programs, and values, this was not yet heavily reflected in the literature, particularly in sources focusing on infants and young children. Forty-one of the 61 sources for this age group were published in the USA and therefore reflected their demographics, where African-American and Native American children are overrepresented in foster care, compared with the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in foster care in Canada. Forty-two of the 74 articles that focused on children and youth were published in Canada, and a number of sources substantially addressed the issue of providing culturally appropriate family interventions.

Attachment based theories provided the framework for the majority of sources focused on infants and young children. The care strategies and interventions identified for this younger population were primarily focused on supporting social–emotional development (often framed as infant mental health). For older children and youth, attachment was often framed as ensuring consistent relationships. In the years since 2006, there has been a substantial increase in awareness of related concepts such as attachment, resilience, epigenetics, and trauma-informed practice. The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (Citation2016) has translated and applied this science to the context of child welfare. Children’s experiences of prolonged adversity such as neglect, toxic stress, abuse, and impoverished living conditions can have long-term impacts on health and development. Interventions provided from an attachment-based perspective included sustaining the relationship of the child with their family, providing visitation, and ensuring consistent quality placements.

A key thread across many sources was the importance of applying a developmental perspective to how interventions, practices, services, and programs are oriented. Most foster care practice documents (such as guidelines, policies, and standards) are generic from a developmental perspective even though they are applied from infancy though to older adolescence. Although the literature primarily identifies the early years as a key window of opportunity for the greatest impact from early intervention, there is also more literature emerging on the importance of prevention and early intervention approaches with youth and adolescents (National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2019).

Supporting parents and foster care providers

Access to adequate resources was described as a key element in keeping children in their birth families and sustaining foster care placements and the focus of 36 publications. For birth and kinship families, sources described how support was focused on prioritizing providing services to maximize the potential for infants and children to stay together (Barth Citation2012, Beckmann et al. Citation2010). These services included child care, respite, housing support, and mental health and substance use counseling, access to case management services, and education on best practices. If foster care was required, this support extended to creating opportunities to sustain relationships and address timely permanency planning (Frame Citation2002, Kenrick Citation2009, McCombs-Thornton Citation2012, Mauren Citation2007, Miron et al. Citation2013, Twomey et al. Citation2011). Inadequate resources resulted in care providers being blamed for poor parenting, stress, and leaving the foster care system.

It was noted that offering specific training on PSE, NAS, and FASD was critical and should be inclusive of the specific needs of infants through to adulthood. For example, the British Columbia Baby Steps publication (2009) offered information on the impact of substances on infants and caregiving strategies addressing concerns related to feeding and sleeping. McGee (Citation2011) identified the need for care providers to have a solid understanding of the adverse impacts of trauma and abuse and suggested that recognizing these issues promotes foster carer responsiveness to children’s needs. Mukherjee et al. (Citation2013) proposed the need for post-adoptive and kinship care supports to reduce caregiver isolation and concerns. Paley and Auerbach (Citation2010) identified a lack of training for caregivers, child welfare, and youth justice staff, while Fuchs et al. (Citation2010) strongly highlighted the need for social workers, particular those doing child welfare work to receive training on FASD to gain a solid understanding of the developmental needs of this population.

Intersectoral collaboration

Twenty-two publications focused on the imperative for groups to operate in interdisciplinary, collaborative, and cohesive ways to best serve children in care affected by PSE. Foster parents reported specific struggles with multi-professional groups that did not recognize the varying presentation of symptoms or the special needs related to PSE, NAS, and FASD (Marcellus Citation2010, Mukherjee et al. Citation2013). Moreover, publications reported a need not only for long-term, integrated planning, but also for support networks (which could include other family members, including birth families, as well as other caregivers) and broad, inclusive community-wide responses to their needs (First Nations Child and Family Caring Society & Paukuutit Inuit Women of Canada Citation2006, First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services Citation2007, Marcellus Citation2010, Mukherjee et al. Citation2013, Pelech et al. Citation2013, Rowbottom et al. Citation2010).

Systemic responses on the way in which services are provided were noted to be critical in relation to coordination and integration of services (Badry and Harding Citation2020, Badry et al. 2011, Centre on the Developing Child at Harvard University 2016, Child Trends and Zero to Three Citation2013, Lloyd et al. Citation2019). For example, Ungar et al. (Citation2014) recommended developing coordinated multi-level services that provide supports at a variety of ecological levels and ensuring that these services are continuous rather than time-limited interventions. They suggested designing a continuum of care system that moves from least to more intensive interventions, which is also strengths-based. Fuchs et al. (Citation2010) further pointed out the potential to create a service model that spans agencies and determinants of health, enabling a systemic response involving interventions at the early childhood stage, child care, other family supports, vocational and employment resources, independent living supports, and affordable housing. They urged that this scale of delivery service integration creates social inclusion could reduce the demand on burdened child welfare systems while simultaneously opening better access to the range of suitable services.

From a developmental perspective, intersectoral collaboration in relation to the infant and young child populations involved connection to perinatal, public health, early childhood, and pediatric partners (Popova et al. Citation2014). Schools systems were identified as key partners across most of the time spent by children in foster care (Assink et al. Citation2009, Badry et al. 2014, Baskin et al. Citation2016, Brown et al. Citation2007, Chasnoff et al. Citation2015, Green Citation2007, Paley and Auerbach Citation2010, Roberts Citation2015). For older children and youth, systemic responses also included justice systems (Burnside and Fuchs Citation2013, Fuchs et al. Citation2010, Popova et al. Citation2011).

Discussion

The primary research questions serve as a guide to this discussion with a focus on the characteristics of interventions and programs to support infants, children, and youth, to promote the satisfaction and retention of a caregivers such as foster and kinship care providers and to identify gaps for further intervention and research and policy development for this population.

Overall, our findings reflected findings from other scoping reviews of foster family care interventions and supports for children with FASD (Bergstrom et al. Citation2020, Bertrand Citation2009, Gypen et al. Citation2017, Peadon et al. Citation2009). In addition, they reflected the compounding disadvantage from PSE, the social conditions from which PSE emerges, and the impact of foster care and disrupted family relationships. Evidence-informed practice, research, and policy in response to PSE, while emerging, remains fragmented, particularly when it relates to the delivery of point of care child welfare services across developmental stages. Emerging literature on stigma also is relevant in this discussion as FASD and other PSE-related diagnoses are not well understood as a disability, nor are they as well positioned for service delivery in contrast to other developmental disabilities (Choate et al. 2019; Corrigan et al. Citation2018).

Developing a continuum of early interventions and supportive programs

Overall, the literature showed that early intervention and support can improve the course of development in both the short and long term (D'Angiulli and Sullivan, Citation2010, Dozier et al. Citation2008, Hubberstey et al. Citation2014; Kalberg and Buckley Citation2007, Nash et al. Citation2015, Olson et al. Citation2007). Infants, children, and youth with PSE are significantly more likely to be in out of home care than the general population (Brownell et al. Citation2011, Meinhofer et al. Citation2020), and as such, it is critical to recognize that early screening, diagnosis, and intervention are the crucial elements of sound care. Even though research has pointed to the need for immediate appropriate service provision and interventions after a PSE diagnosis has been made, many children living in foster care receive inadequate or fragmented services that are not PSE informed. Olson and Montague (Citation2011) identified the need for services to be provided from a neurodevelopmental perspective or viewpoint that recognizes that this population will require specific interventions. Earlier diagnoses tend to result in increased tailored supports (Petrenko Citation2015).

The child protection system has substantial challenges and issues such as confidentiality, privacy, legislation, and overburdened systems, and different professional/disciplinary perspectives and worldviews exist. Any child in this system inevitably experiences multiple transitions and disruptions over time in relation to worker turnover, placement changes, school movement, and continuity in relationships to their birth families, and these changes take a developmental toll that often goes unrecognized. The need exists to consider a life span or life course perspective that addresses the impact of cumulative experiences of change on a child and the long-term consequences of these experiences. Pragmatically speaking, adults who are of legal age who transition out of the child welfare system are rarely ready to do so as limited adult support programs exist. Developmentally, these individuals can lag behind their peers and need ongoing disability supports over their life span in areas such as health care, daily living and social skills, learning, memory, emotional regulation, and communication (Cook et al. 2016). The need for services that support youth in adolescence and in the transition to adulthood is crucial (Burnside and Fuchs Citation2013) alongside adaptive educational environments that accommodate around the challenges of executive functioning for children and youth with FASD and other PSE-related developmental and intellectual disabilities (Green Citation2007).

Supporting foster care providers and parents

A key recommendation in the literature was facilitating and sustaining early, stable, and permanent placements for children with PSE. Children who are placed with foster families early and who have fewer placements have better outcomes in later childhood (Pelech et al. Citation2013, Badry Citation2020). Thus, supporting and retaining skilled foster care providers is a critical component of an integrated and responsive child welfare system. While caseworkers consider permanency planning as a priority for this population, it is not always easy to recruit and retain permanent placements for children with PSE (Burnside and Fuchs Citation2013, Marcellus Citation2010). Placement stability was proposed as particularly important during infancy and adolescence, with consistency in care being critical to helping infants develop quality attachment relationships early in life and helping youth function and adapt as they transition out of care (Hanlon-Dearman et al. Citation2015).

Caregivers of infants, children, and youth with PSE benefit from having a strong understanding of health and developmental implications, alongside knowledge of available supports within the community. Child welfare agencies should make special efforts to recruit those interested in fostering a child with PSE and should provide adequate information to potential care providers to ensure that their expectations are realistic. Foster care providers should also be provided with specialized age-specific additional support, which should include education on how to adapt parenting skills and providing links with support and advocacy groups (Bobbitt et al. Citation2016). Providing respite care and appropriate community resources and activities were also key recommendations to support care providers. Adopting these measures in child welfare agencies could help to prevent placement breakdown, promote stability, and improve outcomes for children and families (Brown et al. Citation2007, Casanueva et al. 2014).

Gaps in practice, policy, and research

The majority of published research focused on the needs and experiences of infants, young children, and school-aged children, with fewer articles addressing practice recommendations for youth and emerging adults in foster care. A key gap noted is the need for research and program development for this population, as they become increasingly vulnerable approaching the age of majority. A further recommendation was the importance of beginning transition planning into adulthood early and involving youth and their families collaboratively in this process, starting before or around age 16 or sooner (Badry and Harding Citation2020, Child and Youth Working Group Citation2007, Manitoba Family Services and Consumer Affairs Citation2011). These recommendations align with a systematic review of the literature on FASD interventions across the life span conducted by Pei et al. (2012), who reported similar findings and argued that there is a need for more research and program development for youth with FASD due to the increased risk at this time for secondary effects of an FASD diagnosis, including trouble with the law, victimization and sexual exploitation, and drug and alcohol concerns.

Placement in foster care is considered a sentinel event for children, acting as a far-reaching signature on the lives of children with long-term physical, emotional, social, and developmental implications (Gypen et al. Citation2017, Zlotnick et al. Citation2012). We began this review with a developmental approach, knowing that ages and stages would most likely underpin how interventions were conceptualized and operationalized. Reflecting on the complex circumstances of many families that arose in the literature, we propose that life course theories, for example Elder’s paradigm, as a form of developmental theory with broader consideration of the influence of socio-structural contexts over time, hold potential utility as frameworks for informing intervention and policy development for this population (Elder Citation1998). Nurius et al. (Citation2015) advance Elder’s paradigm and indicate that using a life course theory serves to amplify the need to pay attention to early life experiences and conditions as these experiences align closely with later health and social outcomes. Further, Nurius et al. discuss the challenge of ‘stacked disadvantage’ (p. 574), which can be aptly applied to infants, children, youth and young adults with PSE.

Although this scoping review examined the impact of PSE, a distinct focus on FASD emerged in particular for children and youth, a topic that has not yet gained the expected traction that is required for effective responses in the child protection system. Strong evidence exists regarding the developmental and life challenges for this population, yet systemic responses consistently fall short due to a lack of existing policy and program infrastructure. Brownell et al. (Citation2011) indicated that individuals with FASD have higher service utilization in health, education, and social services/child welfare system and further note that children with FASD were 10 times more likely in out-of-home care than those in the general population and often have ongoing protection and support needs. Every involvement with children and their families and alternate care providers is a window of opportunity for a response that makes a difference. Therefore, every professional involved in a child’s life has a responsibility to promote positive developmental outcomes. Employing a less functional/task-driven agenda for a more authentic, relational approach between and across the caseworkers responsible for the child’s best interests is a shift that is long overdue (Murphy et al. 2013).

In a recent study comparing outcomes of children and youth with FASD through data gathered on the Canada National FASD Database on 665 youth and adolescents with a confirmed FASD diagnosis, it was noted youth with FASD in care experienced higher rates of sexual/physical abuse in contrast to those not living in care (Burns et al. 2020). Further, these youth also had higher rates of legal problems as both offender and victim in contrast to those not living in care. Of note is that 39% of individuals also with FASD living in care (21.7%) and those living with biological family (27.3%) experienced suicidal ideation and attempts. This research implies that the experiences of youth with FASD in care are critical to examine given the rates of sexual/physical abuse the high risk of suicidal behavior among this population.

The need to keep the cumulative impact of events of early life experiences, including adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), in mind while providing service to this population is essential. In a seminal, online webinar held on March 18, 2021 in Canada through the University of British Columbia, Continuing Education, a research-based presentation by the FASD Changemakers (Lutke et al. Citation2021) identified challenges with ‘Adverse Continuing Experiences’ into adulthood. The introduction of this term serves to underscore that FASD is a lifelong disability with many distinct challenges. It is recognized that many children with FASD have ACEs and new research emerging from adults with FASD in collaboration with researchers suggests that these experiences continue into adulthood. The need exists to mediate these experiences through FASD informed care consistently across all environments. Further, the application of an FASD lens suggests that a basic understanding of the impact of PSE is required, that the disability is understood, that a strengths-based approach is utilized, and that the individual is effectively supported. Recognizing the inherent struggles of FASD as a disabling condition places a responsibility on both professionals and the caregiving network to provide effective care and support.

Limitations

This review primarily included North American sources available in English. As a result, this review may not encompass some potentially applicable publications reflecting wider global context. The review was also limited to a 14-year period of time, three key databases, and selected key child welfare websites. Some potentially relevant publications may not have been identified with these search strategies.

Conclusion

The aim of this scoping review was to identify and describe literature that identifies a range of interventions to support infants, children, and youth in foster care with Prenatal Substance Exposure (PSE) and their care providers. Our goal was to map the available interventions that support this population in particular living with a disabling condition that has a major impact over a life time. Across developmental stages, early screening, diagnosis, and interventions are critical for optimizing conditions for healthy development and stability. However, research on best practices for this population remains limited, particularly for youth approaching transition out of care. There are also still limited evidence-informed interventions and programs for foster and kinship care providers who care for children with PSE. We recognize that there are distinct structural barriers for children in foster care with PSE who have a lifetime of cumulative disadvantages including mental health problems and learning difficulties. Thus, responses should be intersectoral, as opposed to fragmented and siloed approaches that are solely child welfare focused.

Overall the need to provide PSE-informed foster care across infancy, childhood, and into adulthood exists, yet consistent infrastructure in both policy and programs is a challenge in Canada, the USA, and globally. This scoping review highlights the need for a more intentional approach to practice, education, and research on PSE and foster care at the critical intersections of child protection, education, justice, health, and social care. The disabilities associated with PSE have lifelong developmental implications and the need for evidence-based interventions and effective child welfare responses resounds in the literature. It is almost 50 years since the first publications on NAS and FASD in North American literature (Finnegan et al. Citation1975, Jones and Smith Citation1973) and time for a universal model of service delivery from infancy to adulthood.Finally, major gaps exist in the ways in which FASD is understood as a disability, largely due to the stigma associated with the cause – alcohol use in pregnancy. The Canada FASD Research Network (Citation2020) recognizes FASD as the ‘leading cause of neurodevelopmental disability in Canada, affecting 4% of the population…[with an] economic impact [in] health, justice, social services and education…at 9.7 billion’ (https://canfasd.ca/national-fasd-strategy/). FASD remains a stigmatized disability and it is evident through this scoping review that greater attention is required in the areas of supporting parents and caregivers, in forging greater interdisciplinary collaborations and in developing models of excellence in responding to the care needs of this population. FASD is a developmental disability that is rarely talked about in disability venues such as conferences and publications. It is time to include FASD in dialogues on disability globally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Foster Care, Adoption and Kinship Care, Waite, D., Greiner, M. and Laris, Z. 2018. Putting families first: How the opioid epidemic is affecting children and families, and the child welfare policy options to address it. Journal of Applied Research on Children, 9, 4.

- Adams, P. and Bevan, S. 2011. Mother and baby foster placements: Experiences and issues. Adoption & Fostering, 35, 32–40.

- Adnams, C. M., Sorour, P., Kalberg, W. O., Kodituwakku, P., Perold, M. D., Kotze, A., September, S., Castle, B., Gossage, J. and May, P. A. 2007. Language and literacy outcomes from a pilot intervention study for children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in South Africa. Alcohol (Fayetteville, N.Y.), 41, 403–414.

- Alberta Government Ministry of Human Services. 2013. Baby steps: Caring for babies with prenatal substance exposure. Edmonton, AB: Government of Alberta. [online]. Available through: <https://www.mountainplains.ca/assets/files/baby-steps-information-manual.pdf> [Accessed 16 January 2017].

- American Humane Association, Center for the Study of Social Policy, Child Welfare League of America, Children’s Defence Fund, and Zero to Three. 2011. A call to action on behalf of maltreated infants and toddlers. [online] Available through: <www.zerotothree.org> [Accessed 27 October 2020].

- Aromataris, E. and Munn, Z. Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12.

- Assink, E., Rouweler, B. J., Minis, M. A. H. and Hess-April, L. 2009. How teachers can manage attention span and activity level difficulties due to Foetal Alcohol Syndrome in the classroom: An occupational therapy approach. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy, 39, 10–16.

- Bada, H., Langer, J., Twomey, J., Bursi, C., Lagasse, L., Bauer, C., Shankaran, S., Lester, B., Higgins, R. and Maza, P. 2008. Importance of stability of early living arrangements on behavior outcomes of children with and without prenatal drug exposure. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 29, 173–182.

- Badry, D. 2018. Care of children and youth with prenatal substance exposure in child welfare: A scoping literature review of best practices. [online] Available through: <https://canfasd.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2018/07/Scoping-Review-2-pager_April-12-2018-final.pdf> [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- Badry, D. and Harding, K. 2020. Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder and child welfare. Available through: <https://canfasd.ca/wp-content/uploads/publications/FASD-and-Child-Welfare-Final.pdf> [Accessed 27 October 2020].

- Badry, D., Hickey, J, and the Tri Province FASD Research Team. 2014. Caregiver curriculum on fasd (fetal alcohol spectrum disorder). [online] Available through: <https://edmontonfetalalcoholnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/fasd-caregiver-curriculum-6-1-working-with-professionals.pdf> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- Badry, D. and Pelech, W. 2011. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder promising practices: Standards for children in the care of Children’s Services. [online] Available through: <https://policywise.com/wp-content/uploads/resources/2016/07/Fetalalcoholspectrumdisorderpromisingpracticesforchildrenpdf.pdf> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- Badry, D. 2020. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder standards: Supporting children in the care of children’s services. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 4, 47–56.

- Badry, D. and Choate, P. 2015. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A disability in need of social work education, knowledge and practice. Social Work and Social Sciences Review, 17, 20–32.

- Badry, D. and Felske, A. W. 2013. An examination of three key factors: Alcohol, trauma and child welfare: Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and the northwest territories of Canada. Brightening our home fires. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 8, 130–142.

- Barth, R. P. 2012. Progress in developing responsive parenting programs for child welfare-involved infants: Commentary on Spieker, Oxford, Kelly, Nelson, and Fleming. Child Maltreatment, 17, 287–290.

- Baskin, J., Delja, J. R., Mogil, C., Gorospe, C. M. and Paley, B. 2016. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders and challenges faced by caregivers: Clinicians’ perspectives. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology, 23.

- Beckmann, K. A., Knitzer, J., Cooper, J. and Dicker, S. 2010. Supporting the parents of young children in the child welfare system. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty. Available through: <https://www.nccp.org/publication/supporting-parents-of-young-children-in-the-child-welfare-system/> [Accessed 16 January 2017].

- Bergstrom, M., Cederblad, M., Hakansson, K., Jonsson, A., Munthe, C., Vinnerljung, B., Wirtberg, I., Ostlund, P. and Sundell, K. 2020. Interventions in foster family care: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 30, 3–18.

- Benz, J., Rasmussen, C. and Andrew, G. 2009. Diagnosing fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: History, challenges and future directions. Paediatrics & Child Health, 14, 231–237.

- Bernard, K. and Dozier, M. 2011. This is my baby: Foster Parents' feelings of commitment and displays of delight. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32, 251–262.

- Bertrand, J, Interventions for Children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Research Consortium. 2009. Interventions for children with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum disorders (FASDs): Overview of findings for five innovative research projects. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 986–1006.

- Bick, J. and Dozier, M. 2013. The effectiveness of an attachment-based intervention in promoting foster mothers' sensitivity toward foster infants. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34, 95–103.

- Bick, J., Dozier, M., Bernard, K., Grasso, D. and Simons, R. 2013. Foster mother-infant bonding: associations between foster mothers' oxytocin production, electrophysiological brain activity, feelings of commitment, and caregiving quality. Child Development, 84, 826–840.

- Bishop, S., Murphy, J., Hicks, R., Quinn, D., Lewis, P., Grace, M. and Jellinek, M. 2001. The youngest victims of child maltreatment: What happens to infants in a court sample? Child Maltreatment, 6, 243–249.

- Bobbitt, S. A., Baugh, L. A., Andrew, G. H., Cook, J. L., Green, C. R., Pei, J. R. and Rasmussen, C. 2016. Caregiver needs and stress in caring for individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 55, 100–113.

- Boyd, K. A., Balogun, M. O. and Minnis, H. 2016. Development of a radical foster care intervention in Glasgow, Scotland. Health Promotion International, 31, 665–673.

- Boyd, R. 2019. Foster care outcomes and experiences of infants removed due to substance abuse. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 13, 529–555.

- Burry, C. and Noble, L. 2001. The STAFF project. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 1, 71–82.

- British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development and the Vancouver Island Foster Parent Support Services Society. 2009. Safe babies foster parent education program. [online] Available through: <http://fpsss.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Safe-Babies-Resources-links-updated-July-2018.pdf> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development. 2009. Key worker and parent support: Program standards. [online] Available through: <http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/managing-your-health/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder/key_worker_program_standards.pdf> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- British Columbia Ministry of Children and Family Development. 2014. Baby steps: Caring for babieswith prenatal substance exposure. 3rd ed. Victoria, BC: Government of British Columbia.

- Brown, J. D., Bednar, L. M. and Sigvaldason, N. 2007. Causes of placement breakdown for foster children affected by alcohol. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 24, 313–332.

- Brown, J., Sigvaldason, N. and Bednar, L. M. 2007. Motives for fostering children with alcohol-related disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 16, 197–208.

- Brownell, M. D., Chartier, M., Santos, R., Au, W., Roos, N. P. and Girard, D. 2011. Evaluation of a newborn screen for predicting out-of-home placement. Child Maltreatment, 16, 239–249.

- Bruskas, D. 2010. Developmental health of infants and children subsequent to foster care. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing : official Publication of the Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nurses, Inc, 23, 231–241.

- Burd, L., Cohen, C., Shah, R. and Norris, J. 2011. A court team model for young children in foster care: The role of prenatal alcohol exposure and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. The Journal of Psychiatry & Law, 39, 179–191.

- Burns, J., Badry, D., Harding, K., Roberts, N., Unsworth, K. and Cook, J. 2021. Comparing outcomes of children and youth with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) in the child welfare system to those in other living situations in Canada: Results from the Canadian National FASD Database. Child: care, health and development, 47, 77–84.

- Burnside, L. and Fuchs, D. 2013. Bound by the clock: The experiences of youth with FASD transitioning to adulthood from child welfare care. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 8, 40–61.

- Burry, C. L. and Wright, L. 2006. Facilitating visitation for infants with prenatal substance exposure. Child Welfare, 85, 899–918.

- Cameron, G., Freymond, N., Cornfield, D., and Palmer, S. 2001. Positive Possibilities for Child and Family Welfare: Options for expanding the Anglo-American child protection paradigm. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University, Partnerships for Children and Families Project.

- Canada FASD Research Network. 2020. National FASD strategy. Available through: https://canfasd.ca/national-fasd-strategy/[Accessed June 9, 2021].

- Casanueva, C., Dozier, M., Tueller, S., Dolan, M., Smith, K., Webb, M. B., Westbrook, T. and Harden, B. J. 2014. Caregiver instability and early life changes among infants reported to the child welfare system. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38, 498–509.

- Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. 2016. Applying the science of child development in child welfare systems. [online] Available through: <www.developingchild.harvard.edu> [Accessed 25 September 2020]

- Chamberlain, K., Reid, N., Warner, J., Shelton, D. and Dawe, S. 2017. A qualitative evaluation of caregivers' experiences, understanding and outcomes following diagnosis of FASD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 63, 99–106.

- Chasnoff, I., Wells, A. and King, L. 2015. Misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses in foster and adopted children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Pediatrics, 135, 264–272.

- Child and Youth Working Group. 2007. FASD strategies not solutions. [online] Available through: <https://edmontonfetalalcoholnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/strategies_not_solutions_handbook.pdf> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. Glossary: Prenatal substance exposure. [online] Available at://www.childwelfare.gov/glossary/glossaryp/> [Accessed October 26, 2020].

- Child Trends and Zero to Three. 2013. Changing the course for infants and toddlers: A survey of state child welfare policies and initiatives. [online] Available through: <https://www.childtrends.org/publications/changing-the-course-for-infants-and-toddlers-a-survey-of-state-child-welfare-policies-and-initiatives/> [Accessed 25 September 2020].

- Choate, P. 2013. Parents with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders in the child protection systems: Issues for parenting capacity assessments. First Peoples Child and Family Review, 8, 81–92.

- Cohen, J. 2009. Securing a bright future: Infants and toddlers in foster care. [online] Available through: <https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/725-securing-a-bright-future-maltreated-infants-and-toddlers> [Accessed December 13, 2016].

- Cole, S. A. 2006. Building secure relationships: Attachment in kin and unrelated foster caregiver–infant relationships. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87, 497–508.

- Cole, S. A. and Hernandez, P. M. 2011. Crisis nursery effects on child placement after foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 1445–1453.

- Coles, C. D., Strickland, D. C., Padgett, L. and Bellmoff, L. 2007. Games that “work”: Using computer games to teach alcohol-affected children about fire and street safety. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28, 518–530.

- Cook, J. L., Green, C. R., Lilley, C. M., Anderson, S. M., Baldwin, M. E., Chudley, A. E., Conry, J. L., LeBlanc, N., Loock, C. A., Lutke, J., Mallon, B. F., McFarlane, A. A., Temple, V. K. and Rosales, T., Canada Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Research Network. 2016. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: A guideline for diagnosis across the lifespan. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L'Association Medicale Canadienne, 188, 191–197.

- Corsi, D., Hsu, H., Fell, D., Wen, S. and Walker, M. 2020. Association of maternal opioid use in pregnancy with adverse perinatal outcomes in Ontario, Canada, from 2012-2018. JAMA Network Open, 3, e208256.

- Corrigan, P., Shah, B., Lara, J., Mitchell, K., Simmes, D. and Jones, K. 2018. Addressing the public health concerns of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Impact of stigma and health literacy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 185, 266–270.

- Crea, T. M., Guo, S., Barth, R. P. and Brooks, D. 2008. Behavioral outcomes for substance‐exposed adopted children: Fourteen years postadoption. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78, 11–19.

- D'Angiulli, A. and Sullivan, R. 2010. Early specialized foster care, developmental outcomes and home salivary cortisol patterns in prenatally substance-exposed infants. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 460–465.

- Davies, H., Gilbert, R., Johnson, K., Petersen, I., Nazareth, I., O'Donnell, M., Guttmann, A. and Gonzalez-Izquierdo, A. 2016. Neonatal drug withdrawal syndrome: Cross-country comparison using hospital administrative data in England, the USA, Western Australia and Ontario, Canada. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition, 101, 26–30.

- Davidson-Arad, B. and Mussel, O. 2002. Placement of children born to drug using mothers: A preliminary study in Israel. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 2, 15–28.

- Delfabbro, P., Borgas, M., Rogers, N., Jeffreys, H. and Wilson, R. 2009. The social and family backgrounds of infants in South Australian out-of-home care 2000–2005: Predictors of subsequent abuse notifications. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 219–226.

- Denys, K., Rasmussen, C. and Henneveld, D. 2011. The effectiveness of a community-based intervention for parents with FASD. Community Mental Health Journal, 47, 209–219.

- Dozier, M., Peloso, E., Lewis, E., Laurenceau, J. P. and Levine, S. 2008. Effects of an attachment-based intervention of the cortisol production of infants and toddlers in foster care. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 845–859.

- Dozier, M., Peloso, E., Lindhiem, O., Gordon, M. K., Manni, M., Sepulveda, S., Ackerman, J., Bernier, A. and Levine, S. 2006. Developing evidence based interventions for foster children: An example of a randomized clinical trial with infants and toddlers. Journal of Social Issues, 62, 767–785.

- Dozier, M., Zeanah, C. H. and Bernard, K. 2013. Infants and toddlers in foster care. Child Development Perspectives, 7, 166–171.

- Eiden, R. D., Foote, A. and Schuetze, P. 2007. Maternal cocaine use and caregiving status: Group differences in caregiver and infant risk variables. Addictive Behaviors, 32, 465–476.

- Elder, G. H. Jr. 1998. The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69, 1–12.

- Enns, L. N. and Taylor, N. M. 2016. Factors predictive of a fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: Neuropsychological assessment. Child Neuropsychology, 24, 1–23.

- Evaluation Directorate, Government of Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. 2014. Evaluation of the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Initiative 2008-2009 to 2012-2013. [online]. Available through: <https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/mandate/about-agency/office-evaluation/evaluation-reports/evaluation-fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder-initiative-2008-2009-2012-2013.html> [Accessed 16 December 2016].

- Faherty, L., Kranz, A., Russell-Fritch, J., Patrick, S., Cantor, J. and Stein, B. 2019. Association of punitive and reporting state policies related to substance use in pregnancy with rates of Neonatal Opioid Withdrawal. JAMA Network Open, 2, e1914078.

- Fernandez, E. and Delfabbro, P. 2021. Child protection and the care continuum: theoretical, empirical and practice insights. New York: Routledge.

- Finnegan, L., Connaughton, J., Kron, R. and Emich, J. 1975. Neonatal abstinence syndrome: Assessment and management. Addictive Diseases, 2, 141–158.

- First Nations Child and Family Caring Society & Paukuutit Inuit Women of Canada. 2006. FASD training study: Final report. [online] Available through: <<https://fncaringsociety.com/sites/default/files/Caring%20Society%20FASD%20Training%20Study.%20Final%20Report.pdf > [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Services. 2007. Exploring successful models of respite care for First Nations communities in Quebec. [online] Available through: <http://www.cssspnql.com/docs/centre-de-documentation/rapport-services-r%C3%A9pit-ang.pdf?sfvrsn=2> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- Frame, L., Berrick, J. and Brodowski, M. 2000. Understanding reentry to -out-of-home care for reunified infants. Child Welfare, 79, 340–369.

- Frame, L. 2002. Maltreatment reports and placement outcomes for infants and toddlers in out-of-home care. Infant Mental Health Journal, 23, 517–540.

- França, U. L., Mustafa, S. and McManus, M. L. 2016. The growing burden of neonatal opiate exposure on children and family services in Massachusetts. Child Maltreatment, 21, 80–84.

- Fuchs, D., Burnside, L., Marchenski, S. and Mudry, A. 2010. Children with FASD-related disabilities receiving services from child welfare agencies in Manitoba. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 8, 232–244.

- Green, J. H. 2007. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Understanding the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure and supporting students. The Journal of School Health, 77, 103–108.

- Gregory, G., Reddy, V. and Young, C. 2015. Identifying children who are at risk of FASD in Peterborough: Working in a community clinic without access to gold standard diagnosis. Adoption & Fostering, 39, 225–234.

- Gypen, L., Vanderfaeillie, J., De Maeyer, S., Belenger, L. and Van Holen, F. 2017. Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: Systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 74–83.

- Hanlon-Dearman, A., Green, C. R., Andrew, G., LeBlanc, N. and Cook, J. L. 2015. Anticipatory guidance for children and adolescents with Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD): Practice points for primary health care providers. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology, 22.

- Hanlon-Dearman, A., Proven, S., Scheepers, K., Cheung, K., Marles, S. and Centre Team, T. M. F., The Manitoba FASD Centre Team. 2020. Ten years of evidence for the diagnostic assessment of preschoolers with prenatal alcohol exposure. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical Pharmacology, 27, e49–e68.

- Hannes, K. and Lockwood, C. 2011. Pragmatism as the philosophical foundation for the Joanna Briggs meta-aggregative approach to qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 1632–1641.

- Hong, Q. and Pluye, P. 2019. A conceptual framework for critical appraisal in systematic mixed studies reviews. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13, 446–460.

- Hubberstey, C., Rutman, D. and Hume, S. 2014. Evaluation of a three-year youth outreach program for Aboriginal youth with suspected fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research, 3, 63–70.

- Humphreys, C. and Kiraly, M. 2011. High‐frequency family contact: A road to nowhere for infants. Child & Family Social Work, 16, 1–11.

- Hutchison, E.D. 2005. The life course perspective: A promising approach for bridging the micro and macro worlds for social workers. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 86, 143–152.

- Hutchison, E.D. 2019. An update on the relevance of the life course perspective for social work. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 100, 351–366.

- Jarlesnki, M., Paul, N. and Krans, E. 2020. Polysubstanec use among pregnant women with opioid use disorder in the United States, 2007-2016. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 136, 556–564.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. 2015. Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. [online] Available through: <https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/ReviewersManuals/Scoping-.pdf> [Accessed October 9, 2020].

- Johnson, K. 2014. A foster carers’ training package for home treatment of neonatal abstinence syndrome: Facilitating early discharge. Infant, 10, 191–193.

- Jones, K. and Smith, D. 1973. Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. The Lancet, 302, 999–1001.

- Jordan, Z., Lockwood, C., Munn, Z. and Aromataris, E. 2019. The updated Joanna Briggs Institute Model of Evidence-Based Healthcare. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 17, 58–71.

- Kable, J. A., Coles, C. D. and Taddeo, E. 2007. Sociocognitive habilitation using the math interactive learning experience program for alcohol affected children. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 31, 1425–1434.

- Kable, J. A., Coles, C. D., Strickland, D. and Taddeo, E. 2012. Comparing the effectiveness of on-line versus in-person caregiver education and training for behavioral regulation in families of children with FASD. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10, 791–803.

- Kalberg, W. O. and Buckley, D. 2007. FASD: What types of intervention and rehabilitation are useful? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 31, 278–285.

- Kalland, M., Sinkkonen, J., Gissler, M., Meriläinen, J. and Siimes, M. A. 2006. Maternal smoking behavior, background and neonatal health in Finnish children subsequently placed in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 1037–1047.

- Kenrick, J. 2009. Concurrent planning: A retrospective study of the continuities and discontinuities of care, and their impact on the development of infants and young children placed for adoption by the Coram Concurrent Planning Project. Adoption & Fostering, 33, 5–18.

- Koponen, A. M., Kalland, M. and Autti-Rämö, I. 2009. Caregiving environment and socio-emotional development of foster-placed FASD-children. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1049–1056.

- Koponen, A., Sarkola, T., Nissinen, N., Autti-Ramo, I., Gissler, M. and Kahila, H. 2020. Cohort profile: ADEF Helsinki – a longitudinal register-based study on exposure to alcohol and drugs during foetal life. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 37, 32–42.

- Lange, S., Shield, K., Rehm, J. and Popova, S. 2013. Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in childcare settings: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 132, e980–e995.

- Larrieu, J. A., Heller, S. S., Smyke, A. T. and Zeanah, C. H. 2008. Predictors of permanent loss of custody for mothers of infants and toddlers in foster care. Infant Mental Health Journal, 29, 48–60.

- Leenaars, L. S., Denys, K., Henneveld, D. and Rasmussen, C. 2012. The impact of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders on families: Evaluation of a family intervention program. Community Mental Health Journal, 48, 431–435.

- Lloyd, M., Luczak, S. and Lew, S. 2019. Planning for safe care or widening the net?: A review and analysis of 51 states’ CAPTA policies addressing substance-exposed infants. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 343–354.

- Loomes, C., Rasmussen, C., Pei, J., Manji, S. and Andrew, G. 2008. The effect of rehearsal training on working memory span of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 29, 113–124.

- Lutke, C.J., Himmelreich, M., Lutke, A., Griffin, K. and Mitchell, J. 2021. The LIVE FASD Webinar: Results from the FASD Changemakers Lay of the Land Survey #2. University of British Columbia Interprofessional Continuing Education.

- Manitoba Family Services and Consumer Affairs. 2011. Agency standards for children in care with FASD. [online] Available through: <http://www.gov.mb.ca/fs/cfsmanual/pubs/pdf/1.4.9_enp.pdf> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- Marcellus, L. 2008. (Ad)ministering love: Providing family foster care to infants with prenatal substance exposure. Qualitative Health Research, 18, 1220–1230.

- Marcellus, L. 2010. Supporting resilience in foster families: A model for program design that supports recruitment, retention, and satisfaction of foster families who care for infants with prenatal substance exposure. Child Welfare, 89, 7–29.

- Marcellus, L. and Nelson, C. 2011. Pilot project to provincial program: Sustaining safe babies. The Canadian Nurse, 107, 28–31.

- Marcellus, L., Shaw, L., MacKinnon, K. and Gordon, C. 2017. A rapid evidence assessment of best practice literature on the care of infants with prenatal substance exposure in foster care. Victoria, BC: University of Victoria.

- Mauren, G.P. 2007. The effects of foster home placements on academic achievement, executive functioning, adaptive functioning, and behavior ratings in children prenatally exposed to alcohol. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota.

- McCombs-Thornton, K. 2012. Moving young children from foster care to permanent homes: Evaluation findings for the ZERO TO THREE Safe Babies Court Teams Project. Zero to Three (J), 32, 43–49.

- McGee, J. 2011. The mental health needs of infants in foster care. Winona, MN: Winona State University.

- McGlade, A., Ware, R. and Crawford, M. 2009. Child protection outcomes for infants of substance-using mothers: A matched-cohort study. Pediatrics, 124, 285–293.

- McLaughlin, A., Minnes, S., Singer, L., Min, M., Short, E., Scott, T. and Satayathum, S. 2011. Caregiver and self-report of mental health symptoms in 9-year old children with prenatal cocaine exposure. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 33, 582–591.

- McSwiney, D. 2017. National training signals growing awareness of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder. [online] Available through: <https://edmontonfetalalcoholnetwork.org/2017/02/08/national-conference-signals-growing-awareness-of-fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder/> [Accessed September 25, 2020].

- Meinhofer, A., Onuoha, E., Angleró-Díaz, Y. and Keyes, K. M. 2020. Parental drug use and racial and ethnic disproportionality in the U.S. foster care system. Children and Youth Services Review, 118, 105336.

- Melmed, M. E. 2011. A call to action for infants and toddlers in foster care. Zero to Three, 31, 29.

- Michaud, D. and Temple, V. 2013. The complexities of caring for individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: The perspective of mothers. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 19, 94.

- Minnes, S., Singer, L. T., Humphrey-Wall, R. and Satayathum, S. 2008. Psychosocial and behavioral factors related to the post-partum placements of infants born to cocaine-using women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 353–366.