Abstract

Background: Challenging behaviours are common among children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Such behaviours often result in poor quality of life outcomes such as physical injury, difficulties with relationships and community integration.

Aim: This systematic review aimed to synthesise evidence from studies that assessed the effect of interventions used to reduce/manage challenging behaviour among children with intellectual disabilities in community settings.

Methods: Studies published between January 2015 and January 2021 were sought from five electronic databases. The quality of studies was assessed, and a narrative synthesis was conducted.

Results: A total of 11 studies were included which utilised various non-pharmacological interventions including multi-model interventions, microswitch technology, cognitive behavioural therapy, art, music and illustrated stories. Microswitch cluster technology was the most used intervention. Studies using pharmacological interventions were not retrieved. Results indicated that a person-centred planning approach was key to offering individualised treatment.

Conclusions: The superiority of one intervention or a combination of interventions could not be determined from this review given the heterogeneity of studies. Future research is required to explore the use and effects of pharmacological interventions to compare outcomes and improve quality of care of children with intellectual disabilities.

1. Introduction

Intellectual disability (ID) is defined by the World Health Organisation (Citation2019) as having ‘a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn and apply new skills (impaired intelligence)’. Individuals diagnosed with an ID often present with challenging behaviours (CB) which include aggression, stereotypy, self-injury and destruction of property (Lloyd and Kennedy Citation2014). CB has been defined by Emerson (Citation2001) as ‘culturally abnormal behaviour(s) of such intensity, frequency or duration that the physical safety of the person or others is likely to be placed in serious jeopardy, or behaviour which is likely to seriously limit the use of, or the person being denied access to, ordinary community facilities’ (p.7). According to Emerson (2001), the prevalence of CB among the overall ID population is 10 to 15%, however among children with IDs, the prevalence increases to 60% worldwide. This is consistent with recent findings from a systematic review on the prevalence of CB which found that the overall prevalence rates of CB among children with ID ranged from 48% to 60% (Simo-Pinatella et al. Citation2019).

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have been reported as common comorbidities associated with IDs (Tonnsen et al. Citation2016). The prevalence of CB among children with ASD is even higher than children with IDs and has been reported to affect up to 73.5% of children with ASD (Brereton et al. Citation2006). This is of great concern as these behaviours can lead to physical injury (Poppes et al. Citation2016), significant implications in terms of the child’s ability to integrate into their community, develop and maintain relationships (Gonzalez et al. Citation2009) and their overall quality of life. Such behaviours are also known to have a major impact on family members, peers and healthcare staff leading to increased stress and burnout (Absoud et al. Citation2019). Pharmacological interventions are frequently prescribed for children with IDs who display CB, many of which include psychotropic medications (Menon et al. Citation2012), despite a lack of evidence for their efficacy (McQuire et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, those who have a dual diagnosis of both ID and ASD are often the most pharmacologically treated population (Sappok et al. Citation2013). Since the airing of the Winterbourne View scandal (Department of Health Citation2012), there has been a greater focus internationally on individualised care and positive behavioural support to reduce CB and the risk of abuse among this population (Absoud et al. 2019, Brady et al. Citation2019). In recent years, a variety of non-pharmacological interventions have been used to reduce and manage CB including behavioural and environmental strategies/therapies, parent training programmes such as Stepping Stones Triple P (Tellegen and Sanders Citation2013), and physical restraint which involves non-restrictive and restrictive interventions (Menon et al. 2012).

On review of the literature, recent studies have focused on specific behaviours such as self-injurious behaviours, children with Autism (Chezan et al. Citation2017), specific levels of IDs such as children with mild to borderline IDs (Schuiringa et al. Citation2017) or focused on single pharmacological interventions (McQuire et al. 2015). Despite the evidence to support the use of some of those strategies, there seems to be a lack of comparisons within studies evaluating various interventions and their effects. Timely access to interventions which are evidence-based and effective is crucial for this population and their families (Benson et al. Citation2018). Several systematic reviews have been conducted in the area of CB for children with IDs in recent years, one of which included a recent review of non-pharmacological interventions for children up to 12 years with IDs who display self-injurious behaviours conducted by Erturk et al. (Citation2018). The authors of this review outlined the need for future research to consider the effects of pharmacological interventions in conjunction with behavioural interventions.

To date, to the best of our knowledge, there is no systematic review that comprehensively evaluated the broad range of interventions used among this population without focusing on specific behaviours, subgroups, or limited ages as outlined above. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to synthesise evidence from studies that assessed the effect of any interventions used to reduce and/or manage CB among children and adolescents with IDs in community settings. Using the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO) framework (Richardson et al. Citation1995), this systematic review aimed to answer the following questions:

What pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions compared with baseline and/or control conditions were used for children and adolescents with IDs who present with CB in community care settings?

What is the effect of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions used to reduce/manage CB compared with baseline and/or control conditions for children and adolescents with IDs in community care settings?

2. Methods

This systematic review was conducted in conjunction with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins et al. Citation2019) and reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Page et al. Citation2021).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for this review were guided by the modified PICO framework, namely the PICOSS framework to include ‘S’ for Setting and ‘S’ for Study design. The following were the inclusion criteria: Population: Children aged up to 19 years, with a diagnosis of ID and a history of CB. IDs were defined as intelligence quotient (IQ) test score of ≤70, onset before 18 years of age and a significant impairment of social or adaptive functioning (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013). Throughout this review children and adolescents are referred to as children ≤19 years of age (World Health Organisation Citation2013). Children diagnosed with Autism/ASD were included only if they had an IQ ≤ 70. Intervention: Pharmacological and/or non-pharmacological interventions aimed at reducing/managing CBs. Comparison: Studies with between or within group comparisons. Outcome: The effect of interventions on reducing and/or managing CBs. Setting: Community-based settings. Study design: Any experimental study design.

Studies with participants over the age of 19 years, without an ID (IQ > 70), and without a history of CB were not eligible for inclusion. Participants with a diagnosis of autism who do not have a diagnosis of ID (i.e. IQ > 70) were not eligible for inclusion as the primary focus of this review is on children and adolescents with confirmed ID. Studies without interventions, comparisons and/or conducted in acute care settings were also excluded. Review papers, abstract only articles, pilot studies, and conference and editorial papers were not included. Single case studies were also excluded due to limited generalisability of findings to the target population (Stark and Torrance Citation2005). See for full review eligibility criteria.

Table 1. Study inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Search strategy

A scoping search of the grey literature was completed in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (Citation2021), Health Information and Quality Authority (Citation2021), Health Service Executive (Citation2021), World Health Organisation (Citation2021), Google (Citation2021), and Google Scholar (Citation2021), to identify common keywords and synonyms. A comprehensive search was then conducted in five electronic databases namely: MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsychArticles, Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection and APA PsycInfo. The search was conducted based on title or abstract using truncation, the explode feature and phrase searching. Concepts were combined using Boolean operators ‘OR’ and ‘AND’ as follows: (‘intellectual disabilit*’ OR ‘learning disabilit*’ OR ‘developmental disabilit*’ OR ‘mental retard*’ OR ‘mental handicap*’) AND (‘challeng* behav*’ OR behav* OR ‘problem* behav*’ OR ‘aggress* behav*’ OR aggress* OR ‘physical* aggress*’ OR ‘verbal* aggress*’ OR ‘difficult* behav*’ OR self-injur* OR ‘self injur*’ OR self-harm* OR ‘self harm*’) AND (medicat* OR interven* OR treat* OR pharma* OR non-pharma* OR ‘non pharma*’ OR therap* OR manag* OR reduc* OR strateg*) AND (child* OR paediatric* OR pediatric* OR infant* OR toddler* OR adolesc* OR youth* OR teen*).

The search was conducted in February 2021 and was limited to peer-reviewed studies published in English within a six-year timeframe (between January 2015 and January 2021). Of note, a similar systematic review with studies published between 2009 and 2016 was conducted by Erturk et al. (2018). Therefore, the present review provides recent interventions to manage and reduce CBs among children and adolescents with confirmed ID. Moreover, the year limit in the current review coincides with the publication of the National Institute of Care and Excellence (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Citation2015) seminal guidelines: ‘Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges.’

2.3. Study selection

Records identified through database searching were uploaded to Endnote X9, a citation management tool and transferred to Rayyan QCRI ®, a systematic review software system to be screened (Ouzzani et al. Citation2016). Duplicates were removed then aims, objectives and inclusion and exclusion criteria were shared with a second reviewer. Records were screened based on title and abstract independently by the two reviewers. All records deemed potentially eligible were then reviewed on full text by both reviewers and conflicts were resolved through discussions and consensus. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve screening conflicts when needed. The reference lists of the included studies were hand searched for potentially eligible papers.

2.4. Data extraction

Data were extracted using two standardised tables. The first table was based on study characteristics and included the following headings: Author/year and country, aims and objectives, research design, sample and setting, relevant outcome(s), intervention(s) and data collection and instruments (Fineout-Overholt et al. Citation2010). The second table was based on the summary of key study findings for each study. Data were extracted by one author and cross-checked for accuracy by a second author.

2.5. Data synthesis

Given the methodological (i.e. measurement tools and study designs) and clinical (i.e. intervention type and delivery) heterogeneity of studies, a meta-analysis was not plausible. Moreover, it was not plausible to conduct a statistical comparison between the studies using the mean differences and standard deviations. Therefore, a textual narrative approach guided by Popay et al.’s (Citation2006) guidance on narrative synthesis was utilised to report results and draw conclusions from the reviewed studies. Narrative synthesis offers a transparent and systematic means of combining studies together in accordance with the review aim and questions (Soundy et al. Citation2014). This type of synthesis also helps explore gaps in the literature and discuss the strengths of studies using a descriptive approach. In the present review, data were synthesised according to the type of interventions used to reduce and/or manage CB.

2.6. Quality appraisal

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the following four Joanna Briggs Institute (Citation2017) tools: Checklist for Randomised Controlled Trials (Tufanaru et al. Citation2017a), Checklist for Case Series (Moola et al. Citation2017a), Checklist for Quasi-Experimental Studies (Tufanaru et al. Citation2017b), and the checklist for Cohort Studies (Moola et al. 2017b). The key elements of these tools included sample representativeness, randomisation, blinding, validity and reliability of outcome measures, and appropriateness of analysis. Each question was answered as ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘unclear’, or ‘not applicable’. Quality appraisal was conducted by the first author and cross-checked by the last author. Conflicts in quality appraisal were discussed until consensus was reached.

3. Results

3.1. Study selection

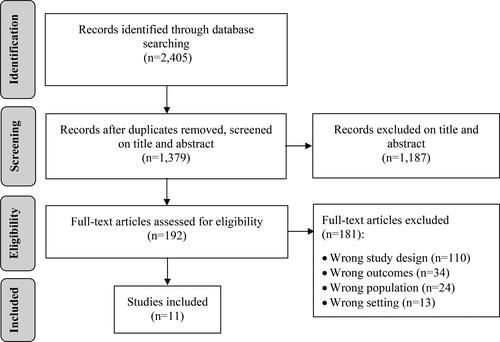

The search identified a total of 2,405 records. Duplicates were removed, and 1,379 records were screened based on title and abstract. In conjunction with the review eligibility criteria, 1,187 records were excluded and judged as irrelevant. Full text screening was completed for 192 records. Of those, 181 records were excluded primarily due to wrong study design (n = 110). A total of 11 studies were included. No additional records were identified from the hand search. See flow diagram of the study selection process.

3.2. Study characteristics

A total of 11 studies were included. Most studies used a case series design (n = 5) and quasi-experimental design (n = 4). The sample size ranged from 3 (Moskowitz et al. Citation2017) to 60 participants (Beh-Pajooh et al. Citation2018). The ages of children ranged from 6 (Kalgotra and Warwal Citation2017, Moskowitz et al. 2017) to 18 (Perilli et al. Citation2019) years across the studies. Nine countries were represented, with Italy as the majority country (n = 3). Most studies were conducted in school and home settings, while one study was conducted in a rehabilitative medical centre (Stasolla et al. Citation2018) and another conducted in a residential care facility (Grey et al. 2018). CBs discussed in the reviewed studies include stereotypic behaviour such as hand/objects mouthing and body rocking (n = 4), aggression including verbal, physical and self-injurious (n = 9) and absconding, avoidance, and tantrum behaviours (n = 5). Microswitch cluster technology was the most used intervention (Stasolla et al. Citation2017; Stasolla et al. 2018; Perilli et al. 2019). This is an educational and rehabilitative program which supports individuals with a dual simultaneous goal of promoting an adaptive response and reducing a challenging behaviour (Stasolla et al. 2017). The technology utilised was dependant on the primary purpose of the intervention and the experimental sequence varied in each study: ABCAC (Stasolla et al. 2017), ABB1AB1 (Perilli et al. 2019), and ABABCBCB (Stasolla et al. 2018). Other interventions included positive behavioural support (Grey et al. 2018), music (Kalgotra and Warwal. 2017, Ekins et al. Citation2019), painting therapy (Beh-Pajooh et al. 2018), cognitive behavioural therapy (Moskowitz et al. 2017, Agbaria Citation2020), functional assessment-based consultations (Inoue and Oda Citation2020) and a socioemotional learning programme (Faria, Esgalhado and Pereira Citation2019). Applied behaviour analysis was utilised as a strategy to implement an intervention in one study (Kalgotra and Warwal 2017), while Moskowitz et al. (2017), also utilised aspects of applied behaviour analysis combined with aspects of positive behavioural support in their study. See Appendices A1 for full study characteristics.

3.3. Quality appraisal

For all quasi-experimental studies (n = 4), it was clear what the cause and effect were, the participants were included in similar comparisons and there were multiple measurements of the outcome pre- and post-test. Methodological issues, however, related to lack of clarity in statistical analysis (Grey et al. 2018), completion of follow up and differentiating between groups (Kalgotra and Warwal 2017), and reliability of outcome measurements (Faria et al. 2019). Furthermore, none of the participants in the studies (n = 4) were included in any comparisons receiving similar care other than the intervention of interest and one study did not have a control group (Grey et al. 2018).

All case series studies (n = 5) reported measuring the condition in a standard and reliable way, utilised valid measures and clearly reported the outcomes and results of cases. Clinical information relating to participants were reported and appropriate statistical analysis was utilised in four studies (Inoue and Oda 2020, Perilli et al. 2019, Stasolla et al. 2017, Stasolla et al. 2018). However, three studies were unclear in relation to having complete inclusion of the participants (Inoue and Oda 2020, Moskowitz et al. 2017, Perilli et al. 2019) and only one study (Stasolla et al. 2017) clearly reported consecutive inclusion of participants.

The quality of the only randomised controlled trial (Beh-Pajooh et al. 2018) was assessed and resulted in several items rated as unclear. For instance, it was not clear if true randomisation took place and if the allocation to treatment groups was concealed. The reliability of outcome measurements and blinding of participants was not clear for those delivering the intervention and outcome assessors. However, analysis was clear, both groups were similar at baseline, the trial was appropriate, and outcomes were measured in the same way for both groups.

The remaining cohort study (Agbaria 2020) met most of the quality appraisal criteria. Groups were similar and recruited from the same population, exposures were measured similarly for assignment, and appropriate statistical analysis was used. Furthermore, follow up time was reported and deemed sufficient for outcomes to occur, and exposures and outcomes were measured in a valid and reliable way. However, confounding factors were not identified it was not clear if participants were free of the outcome at the beginning of the study and the completion of follow-up was unclear. See Appendices A2 for the full quality appraisal checklists. Of note, studies were not ranked based on quality since the use of scales for assessing quality in systematic reviews is discouraged (Higgins and Green 2019).

3.4. Synthesis of results

Non-pharmacological interventions were used to reduce and/or manage CBs in all the reviewed studies (n = 11). None of the reviewed studies included pharmacological interventions as the primary intervention and none included combined (i.e. pharmacological and non-pharmacological) interventions.

Results from this systematic review were synthesised and grouped by intervention type as follows: (i) multi-modal interventions; (ii) microswitch technology; (iii) cognitive behavioural therapy; and (iv) art, music and illustrated stories. The summary of key study findings is presented in supplemental materials in Appendix A3.

3.4.1. Multi-modal interventions

Grey et al. (2018) reported that six of the seven participants in their study reduced their frequency of CBs from baseline and maintained this in the months following implementation of unique behavioural support plans.Further to this Grey et al. (2018) reported an overall reduction in the use of pharmacological interventions as a secondary outcome. Of the seven participants, five were receiving psychotropic medications at the start of the study including ‘anti-depressants, anxiolytics, ADHD medication, anti-psychotics and mood stabilizers’ (Grey et al. 2018, p.402). On completion of this study, however, one participant’s psychotropic medication was no longer required, another participant’s medication dose was significantly reduced, and the remaining three participants had their medication doses stabilized. Although this study had a small sample size (n = 7), it provided evidence that the use of positive behavioural support as a non-pharmacological intervention is effective in discontinuing, reducing, and stabilizing psychotropic medications for this population (Grey et al. 2018).

Similarly, the study by Inoue and Oda (2020) used functional assessment and developed individual interventions for each participant. Among the 10 behaviours identified, the interventions resulted in slightly high to high rates of reduction of 6/10, low reduction rate of 2/10 and no records for the remaining 2 behaviours (teachers reported difficulty recording due to high frequency) among participants. Although not all behaviours reported reductions in this study, in contrast to the study conducted by Grey et al. (2018), Inoue and Oda (2020) reported statistically significant results for overall and average scores. A statistically significant improvement was seen in the total scores of the Criteria for Determining Severe Problem Behaviour (CDSPB), Aberrant Behaviour Checklist (ABC), and externalising behaviours factor of the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL). The pre-average score of the CDSPB was 17.38 (Standard Deviation [SD] = 8.40) with the post average score decreasing to 9 points, a statistically significant improvement (p = 0.05). Statistically significant improvements in the total scores of the ABC (p = 0.02), and total (p = 0.02) and externalising (p = 0.02) scores of the CBCL were also reported (Inoue and Oda 2020).

3.4.2. Microswitch technology

Microswitch technology was the most commonly used intervention (n = 3) to reduce CBs (Perilli et al. 2019, Stasolla et al. 2017, Stasolla et al. 2018). Overall, studies reported positive outcomes relating to the reduction of CBs including hand/object mouthing (Stasolla et al. 2017), hand biting (Perilli et al. 2019), body rocking and hand clapping (Stasolla et al. 2018), as well as increase in participants’ quality of life. For instance, Stasolla et al. (2017) reported that participants (n = 6) commenced their baseline with a mean frequency free of CB (hand/objects mouthing) of 0/30. This increased from 11.7/30 to 14.4/30 during the intervention phase and although it fluctuated during other phases, participants’ time free of CB increased significantly from 16.4/30 to 21.6/30 during follow-up (p < 0.01). This indicates a positive result as a higher score reflects an increase in the amount of time participants did not display CBs. These results are comparable to another study by Perilli et al. (2019), whereby one participant had a mean value of CB (hand biting) significantly decrease from 9.17/60 at the first baseline to 4.67/60 at the second cluster phase and finally to 4.3/60 at the end of the one-year follow-up phase (p < 0.01). This indicated a positive result as a lower score reflected an increase in the amount of time CBs were not displayed by participants. Stasolla et al. (2018) also reported a substantial result for one participant whose CB (body rocking) decreased from 94/100 at the first baseline to 10.33/100 at the fourth contingent intervention, where a lower score indicated a decrease in the amount of time CB was displayed. In accordance with the other two studies which used microswitch technology (Perilli et al. 2019, Stasolla et al. 2017), a difference of statistical significance of p < 0.01 was reported for all participants for the reduction of stereotypic behaviours (body rocking and hand clapping) during the contingent intervention phases.

3.4.3. Cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy was used as an intervention in two studies (Agbaria 2020, Moskowitz et al. 2017), with both studies noting a positive impact of cognitive behavioural therapy on children’s behaviours. Agbaria (2020) included parents as participants (n = 50). The experimental group (n = 25) received fifteen 2.5-hour cognitive behavioural therapy group sessions and the control group participated in an art and painting intervention. It was found that cognitive behavioural therapy significantly improved children’s ability to manage anger and obedience to rules. The mean overall score for the intervention group was 2.56 (SD = 0.26) at pre-test which increased significantly to 3.21 (SD = 0.34) at post-test (t = 3.68; p < 0.01). As for the control group, no statistically significant improvements were observed. Similarly, Moskowitz et al. (2017) indicated significant reductions of CBs (absconding, verbal and physical aggression and tantrum behaviour) post cognitive behavioural therapy as compared to baseline for all three participants: participant 1: 81% CB pre-test (SD = 7%) versus 2% post-test (SD = 4%); participant 2: 77% CB pre-test (SD = 27%) versus 3% (SD = 5%) post-test; and participant 3: 54% CB pre-test (SD = 16%) versus 0% post-test which is a 100% mean baseline reduction.

3.4.4. Art, music, and illustrated stories

Art therapy was utilised in a randomised controlled trial conducted by Beh-Pajooh et al. (2018). The programme delivered to children in the intervention group (n = 30, painting therapy) resulted in a statistically significant difference in externalising behaviours from pre-test (M = 52, SD = 0.73) to post-test (M = 45, SD = 0.80; p < 0.01), while no statistically significant difference was reported in externalising behaviours for the control group (n = 30, usual care) from pre-test (M = 51.56, SD = 0.70) to post-test (M = 51.90, SD = 0.67; p < 0.01).

Two studies focused on music (drums) as an intervention to reduce CB (Ekins et al. 2019, Kalgotra and Warwal 2017). Ekins et al. (2019) found that drums alive sessions for the intervention group (two drums alive sessions and two physical exercise classes per week) demonstrated a non-statistically significant improvement among individual behaviour patterns from week one (M = 1.08/2, SD = 0.64) to week seven (M = 0.52/2, SD = 0.25; p = 0.344) and the control group (exercise intervention alone) showed a slight decrease over time: week one (M = 1.42/2, SD = 0.36) to week seven (M = 1.66/2, SD = 0.47; p = 0.062). However, at the end of the intervention (week 7), the overall difference from results of the developmental behaviour checklist pre- and post-intervention were statistically significant (p = 0.007), indicating the significantly better effect of the drums alive sessions on observed behaviour patterns in comparison to the conventional exercise programme. Kalgotra and Warwal (2017) also found that songs, rhymes, soft music, and drum beating positively reduced CBs (destructive and violent behaviour), using strategies from applied behavioural analysis: verbal instructions, skill modelling, prompting, task analysis, shaping and the use of positive feedback. The mean differences (for mild F1 [contrast] F2 [error], for moderate F1 [contrast] F13 [error]), were significant for children with mild ID (F [1,2] = 36.937, p = 0.26) and moderate ID (F [1,13] = 71.686, p = 0.000) where measures of significance were p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 respectively). In contrast, no statistically significant differences were seen in the control group. Of note, the authors reported that no statistically significant changes were noted within the domains of ‘temper tantrums, odd behaviours and fears’ (p.173).

Faria et al. (2019) focused on a ‘smile, cry, scream and blush’ programme which utilised simple illustrated stories for children with IDs in conjunction with socioemotional learning to improve socioemotional competencies related to behaviour, positive relationships and decision making. It was found that the programme had a positive effect on the experimental group’s (n = 21) behaviours by enabling children to learn, understand and manage their emotions pre-test M = 0.54 (SD = 0.19) versus post-test M = 0.96 (SD = 0.07; p < 0.05) in comparison to the control group (n = 29), where no statistically significant differences were noted. The authors did note, however, that although a statistical difference was reported overall for the experimental group, this was not the case for the item ‘recognition of emotions based on facial expressions.’

4. Discussion

This systematic review aimed to synthesise evidence from 11 studies that assessed the effect of interventions used to reduce/manage challenging behaviour among children with intellectual disabilities in community settings. A variety of CBs were included in the identified studies including aggression, stereotypical, self-injurious, destructive, and anxiolytic behaviours. Non-pharmacological interventions were used in all included studies with microswitch technology being the most common (n = 3). Positive outcomes relating to indices of happiness and statistically significant reductions of CBs including hand/object mouthing, hand biting, body rocking, and hand clapping were reported (Perilli et al. 2019, Stasolla et al. 2017, Stasolla et al. 2018). These results are consistent with earlier research conducted by Stasolla et al. (Citation2014), which reported a reduction of stereotypical behaviours among two high functioning children with ASD through assistive technology. Microswitch-aided technology has also been used in other populations including those in a minimally conscious state to increase functional responding (Lancioni et al. Citation2018). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic review to synthesise evidence from studies which used microswitch technology to reduce and manage CB, specifically among children and adolescents who have a clear/formal diagnosis of ID (IQ ≤ 70).

Other non-pharmacological interventions associated with reductions in CBs included: music (Ekins et al. 2019, Kalgotra and Warwal 2017), painting therapy (Beh-Pajooh et al. 2018), cognitive behavioural therapy (Agbaria 2020, Moskowitz et al. 2017), functional assessment-based consultations (Inoue and Oda 2020), positive behavioural support (Grey et al. 2018) and a socioemotional learning programme involving illustrated stories (Faria et al. 2019). Indeed, in recent years, therapies have been highlighted as high-quality interventions for CBs. Results from the cognitive behavioural therapy intervention in this review are comparable to previous research among adult ID populations. In a study conducted by Willner et al. (Citation2013), cognitive behavioural therapy was found to be effective in improving anger control and decreasing physical aggression among adults with IDs, while Cooney et al. (Citation2017), reported a decrease in anxiety symptoms among adults with mild to moderate IDs using computerised cognitive behavioural therapy in a randomised controlled trial.

Each of the included studies utilised different methodologies and focused on various behaviours and populations, however, all studies centred on the functions of CBs (although preliminary functional analysis was not always conducted). This is reflected through the collection and analysis of data such as: informal interviews and questionnaires and monitoring for improvements following implementation of interventions, which is an interesting finding. The analysis and assessments of the function of behaviours is one of the main components of functional analysis which is a growing area of interest and is recommended as a means of determining appropriate interventions based on the functions of behaviours (Ali et al. 2014).

Studies utilising pharmacological interventions were not retrieved in this review. This may indicate that more studies are being conducted internationally on the use of non-pharmacological rather than pharmacological interventions for the management of CB in children and adolescents with ID across community settings. The rationale for this, perhaps, is the increased focus on non-pharmacological interventions as first treatment options, in line with NICE (2015) recommendations. One of the included studies (Grey et al. 2018) reported on the reduction, stabilisation, and discontinuation of psychotropic medications as a secondary outcome following implementation of their non-pharmacological intervention of behaviour support plans. This contrasts with a systematic review conducted by Deb et al. (Citation2014) on the use of pharmacological interventions for CB among the overall ID and ASD population where improvements were reported for participants receiving aripiprazole (anti-psychotic medication). However, Deb et al (2014) noted that due to the low quantity and quality of studies included, further research on pharmacological interventions was required.

Overall, results from this systematic review indicate that non-pharmacological interventions such as multi-model interventions, microswitch technology, cognitive behavioural therapy, art, music and illustrated stories are effective in reducing and managing a broad range of CBs displayed by children and adolescents with mild to moderate and severe to profound IDs including aggression, stereotypical, self-injurious, destructive, and anxiolytic behaviours. The broad range of non-pharmacological interventions available to this population is promising in terms of possible movement away from historic strategies of punishment, restrictions and negativity which came to light in the Winterbourne View exposure (Department of Health 2012), towards more evidence based proactive strategies which are person-centred.

5. Limitations and future directions

Current review findings suggest several avenues for future research. Given this review did not retrieve any studies which utilise pharmacological interventions, an exploration of the impact of pharmacological interventions on CB is warranted. It is also evident that there is a lack of high-quality evidence available within the systematic review timeframe (i.e. January 2015 to January 2021), to evaluate the effect of non-pharmacological interventions among this population. In addition, only one randomised controlled trial (Beh-Pajooh et al. 2018) was retrieved in comparison to recent studies conducted amongst adult ID populations (Hassiotis et al. Citation2018, McGill et al. Citation2018, Singh et al. Citation2020). This highlights a need for randomised controlled trials on both, pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions, and trials to compare the impact of such interventions, to allow opportunity to compare outcomes. Studies incorporating larger sample sizes with longitudinal design should be a priority for research in this area in order to measure more long-term outcomes.

The results of this review will help build on previous research and offer up to date evidence for policy development and healthcare professionals and families supporting this population. For clinical practice, a continued need exists to support the appropriate assessment and causes/functions of CB among children with IDs to identify individuals in need of intervention. Findings suggest a need for appropriately trained staff to support the implementation and evaluation of evidenced based interventions in community settings and support parents who care for their children at home. Results can also be integrated into curricula for nurses and healthcare professionals working with this population to increase knowledge on the range of non-pharmacological interventions available and ensure the delivery of evidenced based care. Educating students, nurses, and healthcare professionals on the effects of non-pharmacological interventions for CB reduction and management is essential given the potentially serious adverse effects of commonly used pharmacological interventions (Matson and Mahan Citation2010). Furthermore, children with ID have the right to evidenced based services which strive to achieve positive outcomes and improve quality of life (Townsend-White et al. Citation2012).

Despite the encouraging outcomes relating to the reduction and management of CBs for children and adolescents with IDs, this systematic review has some limitations. Firstly, only one randomised controlled trial was retrieved through the database search (Beh-Pajooh et al. 2018). Randomised controlled trials are considered as level 1 evidence and gold standard when evaluating the effectiveness of interventions therefore the significant lack of this study design may impact on the overall findings from this review. The significant lack of randomised controlled trials is a known issue within ID research and has been acknowledged as a priority for this population (Hastings Citation2013). However, previous research has noted that ethical issues may be posed to those wishing to conduct randomised controlled trials on therapeutic interventions for CBs (Oliver et al. Citation2002). The authors excluded single case studies due to limited generalizability of findings. Studies represented small sample sizes with the maximum sample involving 60 participants (Beh-Pajooh et al. 2018) and the review was limited by year of publication (January 2015 to January 2021). While this could have led to the exclusion of relevant studies published before 2015, the decision to limit the search by year of publication helped source the most up to date interventions used to manage and reduce CBs among children and adolescents with ID. There are a number of different tools used to collect data and measure outcomes, which made it impossible to conduct a meta-analysis as findings could not be grouped statistically (Higgins and Green 2019). Finally, many studies involved parents who completed questionnaires and other pre- and post-tests to measure CBs which may have resulted in biased results due to subjective opinions.

6. Conclusion

While this review provides areas for improvement and further research is warranted, evidence to support the use and increasing value of several non-pharmacological interventions to reduce CB among children with IDs is provided. Children with a broad range of ID severity and who present with various forms of CB were included in this review in which results are applicable to many families, healthcare professionals and services supporting this population. From a practical standpoint, all interventions evaluated in this review can be considered for implementation in community settings with many having the potential to add fun and play to routines and/or school curricula. These results have both, social and clinical significance as well as the potential to build on previous evidence, and positively impact on the treatment and reduction of CBs among this population with several important implications for practice, research, and education.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

| Abbreviations | ||

| ABA | = | applied behaviour analysis |

| ABC | = | aberrant behaviour checklist |

| BSP | = | behaviour support plan |

| CB | = | challenging behaviours/ behaviours that challenge |

| CBCL | = | child behaviour checklist /4-18 |

| CBT | = | cognitive behavioural therapy |

| CDSPB | = | criteria for determining severe problem behaviour |

| ID | = | intellectual disability |

| NR | = | not reported |

| O | = | objective |

| PBS | = | positive behaviour support |

| SEL | = | socioemotional learning. |

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge St Joseph’s Foundation for supporting this research piece and approving leave for the first author when/as required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Funding

No external funding received.

References

- Absoud, M., Wake, H., Ziriat, M. and Hassiotis, A. 2019. Managing challenging behaviour in children with possible learning disability. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 365, l1663–6.

- Agbaria, Q. 2020. Acquiring social and cognitive skills in an intervention for Arab parents of children with intellectual developmental disability accompanied by behavioural conditions. Child & Family Social Work, 25, 73–82.

- Ali, A., Blickwedel, J. and Hassiotis, A. 2014. Interventions for challenging behaviour in intellectual disability. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 20, 184–192.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Beh-Pajooh, A., Abdollahi, A. and Hosseinian, S. 2018. The effectiveness of painting therapy program for the treatment of externalising behaviors in children with intellectual disability. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 13, 221–227. https://www.researchgate.net/deref/http%3A%2F%2F http://www.tandfonline.com%2Faction%2FshowCitFormats%3Fdoi%3D10.1080%2F17450128.2018.1428779

- Benson, S. S., Dimian, A. F., Elmquist, M., Simacek, J., McComas, J. J. and Symons, F. J. 2018. Coaching parents to assess and treat self-injurious behaviour via telehealth. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : Jidr, 62, 1114–1123.

- Brady, L., Padden, C. and McGill, P. 2019. Improving procedural fidelity of behavioural interventions for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 32, 762–778.

- Brereton, A. V., Tonge, B. J. and Einfeld, S. L. 2006. Psychopathology in children and adolescents with autism compared to young people with intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 863–870.

- Chezan, L. C., Gable, R. A., McWhorter, G. Z. and White, S. D. 2017. Current perspectives on interventions for self-injurious behaviour of children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 26, 293–329.

- Cooney, P., Jackman, C., Coyle, D., O. and Reilly, G. 2017. Computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for adults with intellectual disability: randomised controlled trial . The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 211, 95–102.

- Deb, S., Farmah, B. K., Arshad, E., Deb, T., Roy, M. and Unwin, G. L. 2014. The effectiveness of aripiprazole in the management of problem behaviour in people with intellectual disabilities, developmental disabilities and/or autistic spectrum disorder-a systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 35, 711–725.

- Department of Health. 2012. Transforming care: A national response to winterbourne view hospital. Department of Health Review: Final Report. Available at: http://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/213215/final-report.pdf (Accessed 10 March 2021).

- Ekins, C., Wright, J., Schulz, H., Wright, R.P., Owens, D. and Miller, W. 2019. Effects of a drums alive kids beats intervention on motor skills and behavior in children with intellectual disabilities. Palaestra, 33, 16–25.

- Emerson, E. 2001. Challenging behaviour: Analysis and intervention in people with severe intellectual disabilities, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Erturk, B., Machalicek, W. and Drew, C. 2018. Self-injurious behavior in children with developmental disabilities: A systematic review of behavioral intervention literature. Behavior Modification, 42, 498–542.

- Faria, S. M. M., Esgalhado, G. and Pereira, C. M. G. 2019. Efficacy of a socioemotional learning programme in a sample of children with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 32, 457–470.

- Fineout-Overholt, E., Melnyk, M. B., Stillwell, B. S. and Williamson, M. K. 2010. Evidence-based practice step by step: Critical appraisal of the evidence: part I. The American Journal of Nursing, 110, 47–52.

- Gonzalez, M. L., Dixon, D. R., Rojahn, J., Esbensen, A. J., Matson, J. L., Terlonge, C. and Smith, K. R. 2009. The behaviour problems inventory: Reliability and factor validity in institutionalised adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 22, 223–235.

- Google Scholar. 2021. Google Scholar. Available at:http://scholar.google.com/. (accessed 20 January 2021).

- Google. 2021. Google. Available at:http://www.google.ie/. (accessed 20 January 2021).

- Grey, I., Mesbur, M., Lydon, H., Healy, O. and Thomas, J. 2018. An evaluation of positive behavioural support for children with challenging behaviour in community settings. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities : JOID, 22, 394–411.

- Hassiotis, A., Poppe, M., Strydom, A., Vickerstaff, V., Hall, I. S., Crabtree, J., Omar, R. Z., King, M., Hunter, R., Biswas, A., Cooper, V., Howie, W. and Crawford, M. J. 2018. Clinical outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support to reduce challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: cluster randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 212, 161–168.

- Hastings, P. R. 2013. Running to catch up: Rapid generation of evidence for interventions in learning disability services. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 203, 245–246.

- Health Information and Quality Authority. 2021. HIQA Resources. Available at: http://www.hiqa.ie/. (accessed 20 January 2021).

- Health Service Executive. 2021. HSE Reports and Publications. Available at: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/. (accessed 20 January 2021).

- Higgins, J. P. T. and Green, S. (Eds.) 2019. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 6.0., Updated July. Chichester, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration. Available at:http://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed 29 January 2021).

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J. and Welch, V. A. 2019. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Inoue, M. and Oda, M. 2020. Consultation on the functional assessment of students with severe challenging behavior in a japanese special school for intellectual disabilities. Yonago Acta Medica, 63, 107–114.

- Joanna Briggs Institute. 2017. The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews. Available at: http://joannabriggs.org/ebp/critical_appraisal_tools. (accessed 3 January 2021).

- Kalgotra, R. and Warwal, S. J. 2017. Effects of music intervention on behavioural disorders of children with intellectual disability using strategies from applied behaviour analysis. Disability, CBR & Inclusive Development, 28, 161–177. http://dx.doi.org/10.5463/dcid.v1i1.584

- Lancioni, E. G., O’Reilly, F. M., Sigafoos, J., D’Amico, F., Buonocunto, F., Devalle, G., Trimarchi, D. P., Navarro, J. and Lanzilotti, C. 2018. A further evaluation of microswitch-aided intervention for fostering responding and stimulation control in persons in a minimally conscious state. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 2, 322–331.

- Lloyd, B. P. and Kennedy, C. H. 2014. Assessment and treatment of challenging behaviour for individuals with intellectual disability: A research review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 27, 187–199.

- Matson, J. L. and Mahan, S. 2010. Antipsychotic drug side effects for persons with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 1570–1576.

- McGill, P., Vanono, L., Clover, W., Smyth, E., Cooper, V., Hopkins, L., Barratt, N., Joyce, C., Henderson, K., Sekasi, S., Davis, S. and Deveau, R. 2018. Reducing challenging behaviour of adults with intellectual disabilities in supported accommodation: A cluster randomized controlled trial of setting-wide positive behaviour support. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 81, 143–154.

- McQuire, C., Hassiotis, A., Harrison, B. and Pilling, S. 2015. Pharmacological interventions for challenging behaviour in children with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 1–13.

- Menon, K., Baburaj, R. and Bernard, S. 2012. Use of restraint for the management of challenging behaviour in children with intellectual disabilities. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 6, 62–75.

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K. and Mu, P.-F. 2017a. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, and Munn Z. (Eds.), Joanna Briggs institute reviewer's manual. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available at: http://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Case_Series2017_0.pdf (accessed 30 January 2021).

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K. and Mu, P.-F. 2017b. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: E. Aromataris and Z. Munn eds., Joanna Briggs institute reviewer's manual. Adelaide, Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available at:http://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Critical_Appraisal-Checklist_for_Cohort_Studies2017_0.pdf. (accessed 30 January 2021).

- Moskowitz, L. J., Walsh, C. E., Mulder, E., McLaughlin, D. M., Hajcak, G., Carr, E. G. and Zarcone, J. R. 2017. Intervention for anxiety and problem behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 3930–3948.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2015. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges. Available at:http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11/resources/challenging-behaviour-and-learning-disabilities-prevention-and-interventions-for-people-with-learning-disabilities-whose-behaviour-challenges-pdf-1837266392005. (accessed 15 January 2021).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2021. NICE Guidance. Available at:http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance. (accessed 20 January 2021).

- Oliver, C. P., Piachaud, J., Done, J., Regan, A., Cooray, S. and Tyrer, P. 2002. Difficulties in conducting a randomized controlled trial of health service interventions in intellectual disability: Implications for evidence-based practice. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 46, 340–345.

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. and Elmagarmid, A. 2016. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M. and Moher, D. 2021. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112.

- Perilli, V., Stasolla, F., Caffo, A. O., Albano, V. and D’Amico, F. 2019. Microswitch-cluster technology for promoting occupational and reducing hand biting of six adolescents with fragile X syndrome: New evidence and social rating. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 31, 115–133.

- Popay, J., Arai, L., Britten, N., Duffy, S., Petticrew, M., Roberts, H., Roen, K., Rodgers, M. and Sowden, A. 2006. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product from the ESRC methods programme. Available at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme. (accessed 10 January 2021)

- Poppes, P., van der Putten, A., Post, W., Frans, N., Ten Brug, A., van Es, A. and Vlaskamp, C. 2016. Relabelling behaviour. The effects of psycho-education on the perceived severity and causes of challenging behaviour in people with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities . Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 60, 1140–1152.

- Richardson, W. S., Wilson, M. C., Nishikawa, J. and Hayward, R. S. 1995. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP Journal Club, 123, A12–3.

- Sappok, T., Budczies, J., Bolte, S., Dziobek, I., Dosen, A. and Diefenbacher, A. 2013. Emotional development in adults with autism and intellectual disabilities: A retrospective, clinical analysis. PLoS One, 8, e74036

- Schuiringa, H., van Nieuwenhuijzen, M., Orobio de Castro, B., Lochman, J. E. and Matthys, W. 2017. Effectiveness of an intervention for children with externalizing behavior and mild to borderline intellectual disabilities: A randomized trial. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41, 237–251.

- Simo-Pinatella, D., Mumbardó-Adam, C., Alomar-Kurz, E., Sugai, G. and Simonsen, B. 2019. Prevalence of challenging behaviors exhibited by children with disabilities: Mapping the literature. Journal of Behavioral Education, 28, 323–343.

- Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Medvedev, O. N., Myers, R. E., Chan, J., McPherson, C. L., Jackman, M. M. and Kim, E. 2020. Comparative effectiveness of caregiver training in mindfulness-based positive behavior support (MBPBS) and positive behavior support (PBS) in a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 11, 99–111.

- Soundy, A., Roskell, C., Stubbs, B. and Vancampfort, D. 2014. Selection, use and psychometric properties of physical activity measures to assess individuals with severe mental illness: A narrative synthesis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 28, 135–151.

- Stark, S. and Torrance, H. 2005. Case study. In B. Somekh and C. Lewin, eds. Research methods in the social sciences (pp. 33–40). London: .Sage

- Stasolla, F., Damiani, R. and Caffo, A.O. 2014. Promoting constructive engagement by two boys with autism spectrum disorders and high functioning through behavioral interventions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 376–380.

- Stasolla, F., Caffo, A. O., Perilli, V., Boccasini, A., Damiani, R. and D’Amico, F. 2018. Fostering locomotion fluency of five adolescents with Rett syndrome through a microswitch-based program: Contingency awareness and social rating. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 30, 239–258.

- Stasolla, F., Perilli, V., Caffo, O. A., Boccasini, A., Stella, A., Damiani, R., Albano, V., D’Amico, F., Damato, C. and Albano, A. 2017. Extending microswitch-cluster programs to promote occupational activities and reduce mouthing by six children with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 29, 307–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-016-9525-x

- Tellegen, C. L. and Sanders, M. R. 2013. Stepping Stones Triple P-Positive Parenting Program for children with disability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34, 1556–1571.

- Tonnsen, B. L., Boan, A. D., Bradley, C. C., Charles, J., Cohen, A. and Carpenter, L. A. 2016. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders among children with intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121, 487–566.

- Townsend-White, C., Pham, A. N. and Vassos, M. V. 2012. Review: a systematic review of quality of life measures for people with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviours. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research : JIDR, 56, 270–284.

- Tufanaru, C. Munn, Z. Aromataris, E. Campbell, J. and Hopp, L. 2017a. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromatari, E. and Munn, Z. (Eds.), Joanna Briggs institute reviewer's manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available at:http://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_RCTs_Appraisal_tool2017_0.pdf. (accessed 30 January 2021).

- Tufanaru, C. Munn, Z. Aromataris, E. Campbell, J. Hopp, L. 2017b. Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness.In: Aromatari, E. and Munn, Z. (Eds.), Joanna Briggs institute reviewer's manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. Available at:http://joannabriggs.org/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI_Quasi-Experimental_Appraisal_Tool2017_0.pdf. (accessed 30 January 2021).

- Willner, P., Rose, J., Jahoda, A., Kroese, B. S., Felce, D., Cohen, D., MacMahon, P., Stimpson, A., Rose, N., Gillespie, D., Shead, J., Lammie, C., Woodgate, C., Townson, J., Nuttall, J. and Hood, K. 2013. Group-based cognitive-behavioural anger management for people with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities: cluster randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 203, 288–296.

- World Health Organisation. (2013). Consolidated Guidelines on the use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection. Available at:http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/arv2013/intro/keyterms/en/. (accessed 20 January 2021).

- World Health Organisation. (2019). Definition: Intellectual disability. Retrieved from http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/mental-health/news/news/2010/15/childrens-right-to-family-life/definition-intellectual-disability. (accessed 4 January 2021).

- World Health Organisation. (2021). WHO Publications. Available at:http://www.who.int/publications. (accessed 20 January 2021).

Appendix A1.

Study characteristics (n = 11)

Appendix A2.

Quality appraisal checklists from joanna briggs institute

A2.1. Quality appraisal of the included quasi experimental studies (n = 4)

A2.2. Quality appraisal of the included case series studies (n = 5)

A2.3. Quality appraisal of the included randomised controlled trials (n = 1)

A2.4. Quality appraisal of the included cohort studies (n = 1)