Abstract

Background: The target group of this study concerns young people with a mild intellectual disability. The central research question is: What evidence can be found in the literature for common and specific factors for a play therapy intervention for young people with a mild intellectual disability struggling with aggression regulation. Method: The criteria used for selecting articles are presented according to the PRISMA, and the PRISMA guidelines for writing a review have been applied. Results: Common factors have been found in the literature that relate to the relationship between therapist and client and the therapeutic skills of the play therapist. Clues have also been found for specific factors of play therapy, such as the use of play as a language and a connection with the child's inner world. In addition, certain factors have been found that are specific to the target group of this article. The non-verbal element of play therapy is an active part of this.

Introduction

Play therapy is a form of psychotherapy that has been developed specially for children (Groothoff et al. 2009). In practice, this therapy is also used for people with intellectual disabilities (Hermsen et al. Citation2020). Practical experience has taught us that for both target groups, children and people with intellectual disabilities, it is an effective therapy for treatment issues aimed at strengthening personal growth. This growth then results in positive behavioural changes (Landreth, Citation2012).

This article focuses specifically on the target group of young people with mild intellectual disabilities. A literature search was conducted, to establish what is currently effective with regard to the play therapy treatment interventions offered to this target group with this specific need for help. This article aims to contribute to the current literature in the field of play therapy aimed at young people with a mild intellectual disability and the possible effects of this intervention. This article identifies where further research is needed on these themes.

From scientific research into the efficacy of psychotherapy for adults, we know that there are general and specific contributing factors, but that little is known about the factors of change effected by these therapies (Cuijpers et al. Citation2019). Various models have been developed about these common factors, with the contextual model by Wampold and Imel (Citation2015) being the best suited to play therapy. The main common factor cited is the therapeutic alliance. In play therapy, the therapeutic alliance is described as the therapeutic relationship that encompasses the therapeutic skills and attitude (Stewart and Echterling Citation2014).

This article reviews the literature regarding the common factors of play therapy intervention for young people with a mild Intellectual Disability. Play therapy is widely used for young people in order to bring about changes in behaviour. The success of this approach is determined by two factors: the interventions by the play therapist and key characteristics or, as they are commonly called, common factors of the process in applying play therapy. This article focuses on finding relevant common factors from the existing literature specifically relating to young people with mild intellectual disabilities, aged 10 to 18, who have behavioural challenging problems due to difficulties in regulating aggression and thus in regulating feelings, thoughts, and behaviours. Little is known about the effectiveness of play therapy for young people with a mild intellectual disability and this need for help. Accordingly, this is an area where more research is needed.

These difficulties often cause problems in daily functioning. These young people have a need for support in the area of aggression regulation. Our study concerns young people with an IQ score of 50 − 70, and also those with an IQ of 70-85 with additional serious problems with social safety (Leeuwen Citation2013). These young people have limited language development and have difficulty in expressing their feelings and emotions in language, leading to aggressive outbursts in situations of distress.

Play therapy could therefore be a suitable intervention for dealing with such aggressive behaviour, because play therapy is largely non-verbal therapy. In particular, Client Centered Play Therapy (CCPT) (Roger, 2012) aims to uncover the underlying causes of aggressive behaviour from the observed changes in behaviour as a result of the therapy (Landreth, Citation2012). Play therapy aims to initiate a change process that influences the cause of the challenging behaviour in the areas of self-regulation, behavioural control and executive functions rather than trying to teach alternative behaviour. This is where CCTP differs from cognitive behaviour therapy, for example. Although in practice, play therapy as an intervention is used regularly with people with a mild intellectual disability, there is still limited evidence of its value and effectiveness (van de Witte et al. Citation2017). Mora et al. (Citation2018) have studied the use of play therapy for this target group and reported effects of changes in behaviour, and have suggested that the common factors producing these changes should be investigated.

This study aims to give an overview of the common factors cited in the literature on play therapy as a treatment intervention for young people with a mild intellectual disability. A distinction is made in this article between the common and specific active elements of play therapy. The generally working factors are the skills and attitude of the therapist. The specific factors are the play therapeutic features and the elements of play therapy that are specifically active for young people with mild intellectual disabilities.

Mild intellectual disability

The young people considered in this study have a mild intellectual disability. The DSM-5 gives the following definition of 'intellectual disability' for our target group: a level of mental ability which is so weak that this determines their functioning in daily life (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013-2018).

This intellectual disability manifests itself in the field of cognition, social and practical development.

During the development from child to adult, a number of transitions can be identified.

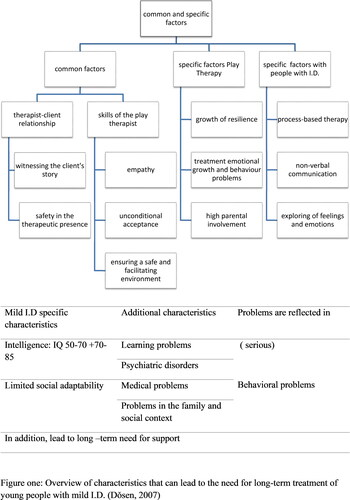

These transitions refer to the development of a person in the different phases of their life. In this development we distinguish four areas: 1) physical and motor development, 2) mental or cognitive development, 3) social-emotional development, 4) sexual development. Young people with a mild intellectual disability have more trouble with these transitions than their peers with a normal development. Mild intellectual disability is defined here as an IQ score between 50-70 but can also include an IQ score between 70 and 85 with additional psychological problems. provides an overview of characteristics of young people with mild intellectual disability which leads to a need for long-term support and therapeutic treatment.

Figure 1. Overview of characteristics that can lead to a need for long-term treatment for young people with mild intellectual disability (Dǒsen, 2014).

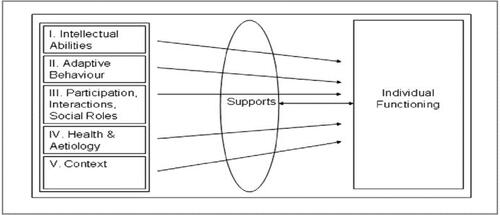

The other definition of intellectual disability is that of the American Association on Developmental and Disabilities (AAIDD) (Buntinx and Schalock Citation2010). The AAIDD indicates that there is a limitation if you cannot perform one or more essential life operations. Five areas are used in the description of the disability: a) Intelligence: the measurement of learning ability in comparison with peers and how one can apply knowledge; b) Adaptive behaviour: the behaviour through which people deal with changes: young people with intellectual disabilities are often limited by their poor adaptive behaviour; c) social roles, interaction and participation: they are often less able to engage in family contacts and social interaction; d) Health: physical complaints weigh more heavily in combination with reduced intelligence and less capacity for adaptive behaviour; e) Context or environment: in addition to the immediate environment such as family, school and work, this also concerns the environments in which the family, for example, participates. The five domains cannot be seen as separate areas because they influence each other.

In the model of the AAIDD (Buntinx and Schalock Citation2010), the aspect of emotional development is not yet visible (Bruijn et al. 2017). For young people with mild intellectual disability, recognizing and regulating emotions can be challenging and can disrupt daily life. The aspect of emotional development and the (lack of) ability to regulate emotions is a common reason for needing play therapy (Yeager and Yeager Citation2014).

Aggression regulation

Aggressive behaviour in this article is understood as behaviour that causes damage to another person or an object. This includes both physical and verbal aggression. It is striking that verbal aggression scores high in people with mild intellectual disabilities (Kok et al. Citation2016). It is difficult to make a statement about the prevalence of aggressive behaviour in people with intellectual disability. This is due to the use of the many definitions of aggressive behaviour, the variation between severe and mild intellectual disability in the research groups, and the different settings within which the studies took place (Tenneij et al. Citation2009). The approach to aggression is based on the development perspective as an explanatory model, see (Dosen, Citation2014). Young people with mild intellectual disability are at greater risk of derailment and aggression control problems owing to the following reasons: a) it is difficult to complete school education successfully; b) their prospect for a job on the labour market is limited; c) filling free time is difficult and it is often hard to start friendships and relationships; d) there is a greater risk of getting into debt and becoming involved in crime; e) there are often challenges in the family system due to insufficient adaptation or too high expectations from relatives (Leeuwen Citation2013).

Figure 2. Theoretical model of intellectual disability, AAIDD (Buntinx and Schalock Citation2010).

Young people with mild intellectual disability are often overstretched because they have learned to present themselves well and to mask their disability. They hide the fact that they do not understand something and their limitation often does not become apparent (Buntinx and Schalock Citation2010). This makes it difficult to recognize signs of overload. Communication with these young people involves a continuous balance between their self-presentation and the actual support they need. In therapy for such young people, the therapeutic skills of the therapist are important. A therapist needs to be able to facilitate young people during the therapy and to create sufficient safety so that these clients actually dare to speak up about their problems (Geller and Porges Citation2014).

In summary, young people with mild intellectual disability have problems in several areas, including the regulation of their emotions, which can lead to aggression. Play therapy has been shown to be a suitable intervention for young people in general. However, we do not yet know what the common and specific active mechanisms of play therapy are for our target group. That is why a review of the literature is now being conducted to clarify this.

Play therapy

To clarify what is meant by play therapy as a treatment intervention, the definition of The Association for Play Therapy (2014) is used. They describes play therapy as follows:

“The systematic use of a theoretical model to establish an interpersonal process in which therapy is used to help prevent psychosocial problems and resolve optimal growth and development." (Jensen et al. Citation2017, p. 390).

All of this leads to the research question that is addressed in this review of the literature: What is known in the literature about the common factors of play therapy as a treatment intervention for young people between the ages of 10 and 18 with mild intellectual disability and aggression regulation problems?

Method

Design

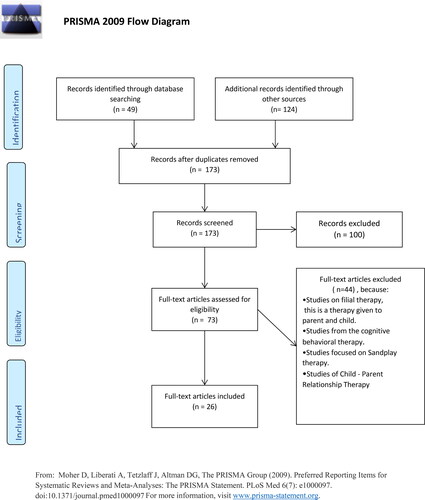

The guidelines of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) (Moher et al. 2009) and the literature of Nightingale (2009) have been used. It was decided to work with the PRISMA model in order to provide more transparency and to substantiate the choice of studies used. The PRISMA model works with a checklist, which can be used to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. This checklist was used to select the studies.

The studies used for this review were found in electronic databases. The following databases were searched: Academic Search, Wily, Science Direct, Psych Articles, Google Scholar Psych Info, Sage Journals Online and PubMed.

The following search terms were used: play therapy active mechanisms, play therapy effects, play therapy youngsters, play therapy young people with a mild intellectual disability, play therapy behavioural problems, and play therapy aggression regulation, and a combination of these search terms. The selected articles are coded with the following terms as defined by Rogers (Citation2012) for client-centered play therapy: empathy, unconditional acceptance, being able to witness, being able to provide a safe environment. These concepts were chosen because these are the basic forms of the therapeutic relationship in play therapy In addition, the following codes were used: play as language, parental involvement, resilience, process-based nature of play therapy, non-verbal communication, exploration of emotions and feelings.

The following journals were also searched: Journal of Counselling and Development, Journal of Play Therapy, American Journal of Family Therapy, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, Journal of Humanistic Counselling, Journal of Psychology at the Schools, Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, Research in Developmental Disabilities. The following selection criteria were applied: 1) appeared in print between 2008 and 2020; 2) use of non-directive play therapy and/or the CCPT (client-centred play therapy) approach; 3) the studies must be peer-reviewed articles; 4) both studies with a quantitative and a qualitative research design have been included; 5) the studies must give an indication about the common factors of play therapy; 6) studies on individual play therapy as well as group play therapy treatments.

The literature search focused on common factors of play therapy. This search was divided into three parts: the first part focused on common factors. The second part focused on specific factors regarding adolescents and adults in play therapy. The third part concentrated on specific factors for play therapy concerning young people with mild intellectual disability, and on the combination of these specific factors of play therapy for the respondents of this study: young people with a mild intellectual disability and aggression regulation problems. Specific factors in other treatment interventions for aggression regulation of young people with a mild intellectual disabilities are included in this study as well.

In 2010, Phillips published a systematic review of the meta-analyses conducted up to that date on the effectiveness of play therapy (Bratton et al. Citation2005; LeBlanc and Ritchie Citation2001). Philips noted three deficiencies in these meta-analyses: 1) forms of treatment were included in the analyses that do not comply with the traditional description of play therapy; 2) poor quality in the studies that were included, and 3) a lack of studies with long-term outcomes. We agree with Philips in this assessment, and have therefore not included these meta-studies in our review.

No inclusion criteria were formulated for the participants of the studies. This is because there are few studies that have conducted research on play therapy and adolescents/children with mild intellectual disability, play therapy with adolescents, or play therapy as treatment intervention for behavioural problems such as aggression regulation. The three analyses as described in the introduction have focused on the common factors. Our search based on the above approach produced a total of 30 articles. These articles have been categorised as 1) common factors, 2) specific factors for play therapy and 3) articles dealing with specific factors for young people with mild intellectual disability. gives a schematic overview of the literature included in this review.

Results

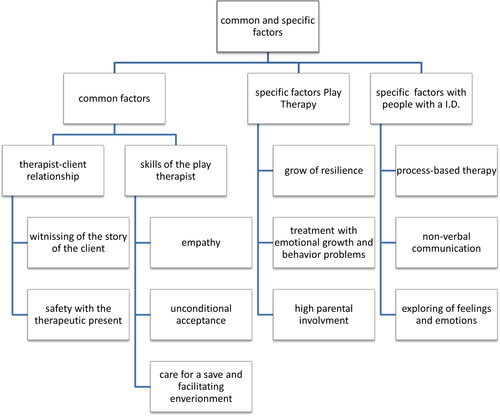

The results will be presented schematically with a classification in the following three main categories, i.e. common factors, specific factors of play therapy in general, and specific factors concerning young people with an intellectual disability.

provides an overview of the common and specific factors found in the literature.

The scheme in does not include the specific factors of aggression control and play therapy. The reason is that the literature shows that the specific factors of aggression control correspond to the common factors. These mechanisms all relate to the attitude and skills of the play therapist (Davenport and Bourgeois Citation2008).

The common factors are divided into two groups, namely: the therapeutic skills and the relationship between therapist and client. This classification emphasizes the importance of the therapeutic relationship in play therapy. The therapeutic relationship gives the opportunity to communicate with children through their own language (play) and words (toys) (Landreth, Citation2012; Post et al. Citation2019). The play therapist develops an important relationship with the child, which allows the child to develop resilience (Post et al. Citation2019).

The following tables provide an overview of the articles used for the following description as they all address common and specific factors.

In the description of the tables it has been decided to also say something about the persuasiveness of the articles. The reason for doing this stems from the fact that the play therapy studies sometimes have problems with their methodology which reduces the reliability. The studies are divided into three groups: case studies, RCT studies and literature reviews. Conclusive are the the studies as described below.

Of the single case studies, these are the studies that used a design with two phases, the baseline and the treatment phase (AB design). The literature studies looked at the completeness of the concepts described. The RCT studies looked at the number of sessions of the intervention, representative study population and the use of a control group. A short intervention period, the study population not representative for play therapy, for example pre-school children or counselors, in the single case studies no AB design were reasons to consider these studies as unconclusive ().

Table 1. Overview of articles with an overall effect of Play Therapy, 2008-2020

Table 2. Overview of articles with an indication of active mechanisms of Play Therapy specifically for Adolescents and Adults, 2008-2020

Table 3. Overview of articles with an indication of active mechanisms of Play Therapy with people with a mild intellectual disability 2008-2020

Common factors

An important common factor of play therapy is the sense of safety that the client experiences in the interaction with the therapist (Landreth, Citation2012). Vanfleet and Mochi (Citation2018) describe how the ability of people to function generally, make contact with others, and process information is affected by strong feelings of insecurity. The literature also mentions that for adult clients, experiencing safety during therapy is a common factor for a positive outcome of therapy (Lin and BrattonCitation2015,Olson-Morisson Citation2017, Swank et al. Citation2018). The therapeutic presence facilitates this feeling of safety so that it can be further strengthened in the therapist-client relationship. The therapist-client relationship is enhanced in therapy sessions by another common factor: the unconditional acceptance of the client by the therapist. Unconditional acceptance helps the client to accept their own feelings, to respect themselves and to express these feelings (Landreth, Citation2012). An important part of this unconditional acceptance is that the therapist can witness the client’s story. The therapist doesn’t look away but actively engages with the story and the effort of the client who shares this story through play (Gil Citation2018). Another important common factor is the term empathy (Jayne et al. Citation2019). Winburn et al. (Citation2020) describes the empathic ability of the play therapist as the vehicle for establishing a therapeutic relationship within which the child accepts the therapy into its world. These potential common factors: empathy, safety, unconditional acceptance and witnessing can all find their place within the therapist-client relationship. Within the CCPT tradition (Rogers Citation2012), the therapist-client relationship is an important common factor. In CCPT, the therapeutic relationship is seen as the means for sustainable change and growth in the client (Landreth, Citation2012). Another common factor is that the therapist connects with the development of the client and can communicate through play.

In addition to a common factors that is linked to the therapeutic relationship, there are also indications in the literature of specific effects of play and the therapeutic effect of play (Rahman and Hamedi et al, Citation2014). Eberle’s description of play (Citation2014) gives insight into why play as a language works in therapy. This definition is as follows:

Play is an old voluntary process that is driven by pleasure but also strengthens our muscles, develops our social skills, strengthens and deepens our positive emotions and brings us into a state of balance that makes us want to play more (Eberle Citation2014, p. 231).

These broad and common functions of play can be used to orient play therapy towards the intrinsic qualities of play that can strengthen the therapeutic relationship. They can also be used to determine the choice for those play interventions that connect to the therapeutic interventions that are performed with the client and to make optimal use of the therapeutic mechanisms of play (Brooks and Goldstein Citation2018). In their research, Brooks and Goldstein (Citation2001, Citation2004) state as an elementary conclusion that child resilience develops in a meaningful relationship and contact with adults involved (Brooks and Goldstein Citation2018). This can be interpreted as a common factors in terms of the therapist’s attitude, which acts as an example to the client of resilience and hope.

Specific active mechanisms

In the literature, there are several indications of specific factors in play therapy. The client-centered approach (CCPT) in play therapy was originally focused on children without an intellectual disability, but with a behaviour-related need for help. There are also indications in the literature for specific factors of play therapy for youth and adolescents.

A specific factors cited in various articles is high parental involvement in play therapy (Jensen et al. Citation2017). A note of caution here is that in the first meta-analysis in which the CCPT approach was central, studies were also used in which Filial Therapy was considered. This is a form of play therapy that does not treat the individual child but is a form of parent-child treatment with the aim of improving the parent-child relationship and empowering the parent (Porter, Hermandez-Reif et al. 2009). This implies that the effect of parental involvement in play therapy as a common factor is reduced to a low-to-average level of importance.

Another indication in the literature for specific active mechanisms in play therapy concerns resilience-enhancing factors. Play is connected to the inner world of the child and we see this inner world reflected in the interactions and relationships that children have with others. In these interactions we also see the hope and resilience of the child. By playing with the child and being an example of a committed and charismatic adult as a therapist, the child's hope and resilience can develop further (Crenshaw et al. 2018). These processes are helped by the observation that play therapy somehow acts as a substitute for the use of language.

Another natural element of play is that children learn to manage their emotions and feelings through play. Play aimed at controlling emotions could be seen as a reflection of the innate capacity for resilience in the child. Play therapy has been influenced by resilience research in the last 20 years (Mei Citation2006; Seymour Citation2014). During this period, Schaefer and Drewes (Citation2014) made an overview of the specific active mechanisms of play therapy. This overview is divided into four categories, namely: facilitating communication, strengthening emotional well-being, increasing parental involvement (and possibly social contacts in general) and promoting personal growth. A specific active mechanism is the personal growth of the client focused on hope and resilience. Resilience one of the active mechanisms which, according to Seymour (Citation2018), needs to be investigated further because this is a relatively new concept for play therapy. This recent theory about the connection between resilience research and play therapy suggests new specific active mechanisms.

Another indication of efficacy in play therapy not mentioned in is related to the treatment demand from clients .Various studies show that play therapy can be an effective intervention for issues in the areas of emotional growth and externalizing behavioural problems (Ritzi et al. Citation2017; Meany-Walen Citation2017, Meany-Walen et al. Citation2015; Landreth et al. Citation2009). It should be noted that this indication is based on relatively small studies.

Specific active mechanisms for people with a mild intellectual disability

Limited evidence for specific factors of play therapy in adolescents with a mild intellectual disability and aggression regulation problems has been found in the literature. There are two case studies (Swan and Ray Citation2015; Swan and Schottelkorb, Citation2014) that investigated the effects of play therapy in children with a mild intellectual disability that can be called promising with regard to the reduction of behavioural problems.

According to these studies, common factors of play therapy for this target group are the non-verbal nature of therapy, the process-based nature of play therapy and the ability to investigate one's own feelings and emotions. The efficacy of Prouty et al. (Citation2001) Pre-Therapy is also described, which concerns the process of contact work. This is the concept of building “psychological contact” which includes the following elements: 1) contact reflections by the therapist, 2) contact functions of the client, 3) contact behaviour that is measurable. The importance of the therapeutic attitude and relationship that emerged in the other articles seems to indicate that pre-therapy can make an important contribution to the building of the therapeutic relationship in play therapy offered to people with mild intellectual disabilities.

Strength and limitations of this review

A strong point of this review is its systematic approach. The articles have been carefully selected using predefined criteria. An adapted PRISMA 2009 flow diagram has been used for the studies included in this review. Only studies relevant to common factors of play therapy have been used. An important criteria is that this common factors can also tell us something about the specific factors of play therapy offered to young people with mild intellectual disabilities. Because play therapy is a specific form of therapy, specific characteristics of therapeutic play have also been included.

Finally, to the authors' knowledge this is the first systematic review in which the three perspectives: different working mechanisms of play therapy, young people with mild intellectual disabilities and aggression regulation problems have been investigated.

However, publication bias could not be reliably assessed due to the limited number of included studies (Higgins and Green Citation2011).

Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we opted to focus on young people with a mild intellectual disability and aggression regulation problems. Other characteristics such as autism, for example, have not been taken into account. This choice was made to keep the complexity of the study manageable as more underlying problems require a different approach to play therapy. This choice also represents a limitation of this article because many autistic children have mild to moderate intellectual disability

This study aims to give an overview of the common factors mentioned in the literature on play therapy as a treatment intervention for young people with a mild intellectual disability. There are a number of issues that stand out when studying the literature on common factors and play therapy. Firstly, the average benefit of play therapy is moderate in the case of more behaviourally oriented treatments. This is partially due to the limited amount of research in the field of play therapy and this research does not always meet the standard quality requirements for research. The studies concerned are mostly small-scale and include a number of meta-analyses in which the different approaches to play therapy are taken together.

Another striking point is the small number of continental European studies on play therapy. Most of the research has been conducted in America, England, and a small number of Asian countries.

On the basis of the literature, indications have been found for common factors of play therapy. From the clues found in the literature, a distribution has been made of common factors that in turn are subdivided into attitudes and skills of the therapist. In addition, two groups with specific factors have been found: specific factors of play therapy, and specific factors of play therapy given to people with mild intellectual disability. These common and specific factors are combined in a diagram as shown in of this article.

It is remarkable that little is known about the common factors of play therapy in relation to people with mild intellectual disability. This is all the more striking because in the Netherlands play therapy is often used in practice for people with mild intellectual disability. It may be possible that the common factors found together with the specific play therapeutic factors could also be effective in play therapy offered to people with mild intellectual disability. But this is only a hypothesis and needs further (experimental?) investigation. It is important that further research is conducted on the common factors of play therapy offered to this target group. This is because there are few forms of treatment for this target group that process-regulate aggression.

Further research on play therapy as an effective intervention for this group of young people would therefore be appropriate.

The findings from the literature described in this study and the non-verbal nature of the play therapy will form the starting point for the development of a program theory.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013–2018. Handboek voor classificatie van psychische stoornissen (DSM-5). Nedelandse vertaling van Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Bratton, S. C., Ray, D., Rhine, T. and Jones, L. 2005. The efficacy of play therapy with children: A meta-analytic review of treatment outcomes. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 376–390.

- Brooks, R. and Goldstein, S. 2001. Raising resilient children. New York: McGrawHill.

- Brooks, R. and Goldstein, S. 2004. The power of resilience. New York: McGrawHill.

- Brooks, R., and Goldstein, S. 2018. Chapter 1: De kracht van mindsets. In: D. B. Crenshaw, ed. Veerkracht versterken met speltherapeutische interventies. Amsterdam: SWP, pp.13–40.

- Bruin de, J., Broek van de, A., Vonk, J. and Twint, B. 2017. Emotionele ontwikkeling en verstandelijke beperking: Inleiding op een dynamisch begrip. In: J. de Bruijn, ed. Handboek emotionele ontwikkeling en verstandelijke beperking. Amsterdam: Boom.

- Buntinx, W.H.E. and Schalock, R.L. 2010. Models of disability, quality of life, and individualized supports: Implication for professional practice in intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7, 283–294.

- Cuijpers, P., Reijnders, M., Huibers M. J. H. 2019. De rol van gemeenschappelijke factoren in psychotherapie-uitkomsten. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 207–231.

- Davenport, B. and Bourgeois, M.N. 2008. Play, agression, the preschool child, and the family: A review of literature to guide empirically informes play therapy with agressive preschool children. International Journal of Play Therapy, 17, 2–23.

- DǒSen, A. 2014. Psychische stoornissen, gedragsproblemen en verstandelijke beperking. Assen: Van Gorcum.

- Geller, M.S. and Porges, S.W. 2014. Therapeutic presence: Neurophysiological mechanisms mediating feeling safe in therapeutic relationships. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 24, 178–192.

- Eberle, S. G. 2014. The elements of play: Toward a philosophy and definition of play. American Journal of Play, 6, 214–233.

- Gil, E. 2018. Chapter 5: Postraumatisch spel. Een solide weg naar veerkracht. In: D. B. Crenshaw, ed. Veerkracht versterken met speltherapeutische interventies. Amsterdam: SWP, pp. 105–123.

- Hermsen, P., Embregts, P. and van der Meer, J. (Eds) 2020. Mensen met een verstandelijke beperking. 6de ed. Twello: Van Trigt uitgeverij.

- Higgins, J. P. T. and Green, S. 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. <www.cochrane-handboek.org>.

- Jayne, M., Purswell, K. E. and Stulmaker, H. L. 2019. Facilitating congruence, empathy, and unconditional positive regard through therapeutic limit-setting: Attitudinal conditions limit -setting model (ACLM). International Journal of Play Therapy, 28, 238–249.

- Jensen, S. A., Graham, E.R. and Biesen, J.N. 2017. A meta-analytic review of play therapy with emphasis on outcome measures. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 48, 390–400.

- Kok, L., Waa van der, A., and Didden, R. 2016. Gedragsstoornissen en agressief gedrag. In R. Didden, P. Troost, X. Moonen and W. Groen, ed. Handboek Psychiatrie en lichte verstandelijke beperking. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom, pp.81–98.

- Landreth, G. 2012. Chapter 1:The meaning of play. In: G. Landreth, ed. Play therapy the art of the relationship. New York, London: Routledge, pp.7–24.

- Landreth, G. 2012. Chapter 5: Child-centered play therapy. In: G. Landreth, ed. Play therapy: The art of the relationship. New York/London: Routledge, pp.53–95.

- LeBlanc, M. and Ritchie, R.M. 2001. A meta-analysis of play therapy outcomes. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 14, 149–163.

- Leeuwen, M. v. 2013. Heel gewoon en toch bijzonder. Aandacht voor kinderen en jongeren met een lichte verstandelijke beperking in de gemeente. Den Haag: Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport/Directie Jeugd.

- Lin, Y. W. and Bratton, S.C. 2015. A meta-analytic review of child-centered play therapy approaches. Journal of Counseling & Development, 93, 45–58.

- Mei, D. 2006. Tijdgebonden speltherapie om de veerkracht bij kinderen te verbeteren. In: C.E. Schaefer and H.G. Kaduson, eds. Contemporary play therapy: Theory, research, and practice, pp. 293–306. Guilford Pers.

- Meany-Walen, K.K. 2017. Effectiveness of a play therapy intervention on children's externalizing and off-task behaviour. ASCA Professional School Counseling, 89–103.

- Meany-Walen, K. K., Kottman, T., Bullis, Q. and Taylor, D.D. 2015. Effects of Adlerian play therapy on children's externalizing behaviour. Journal of Counseling and Development, 93, 418–428.

- Mora, L., Sebille van, K. and Neill, L. 2018. An evaluation of play therapy for children and young people with intellectual disabilities. Research and Practice in Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 5, 178–191.

- Olson-Morisson, D. 2017. Intergrative play therapy with adults with complex trauma: A devellopmentally-informed approach. International Journal of Play Therapy, 26, 172–183.

- Phillips, R. 2010. How firm is our foundation? Current play therapy research. International Journal of Play Therapy, 19, 13–25.

- Post, P. B., Phipps, C. B., Camp, A. C. and Grybush, A. L. 2019. Effectiveness of child-centered play therapy among marginalized children. International Journal of Play Therapy, 28, 88–96.

- Prochaska, J. O., and DiClemente, C. C. 1983. Stadia en processen van zelfverandering van roken: naar een integratief model van verandering. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51, 390–395.

- Prouty, G., Werde van, D. and Portner, M. 2001. Pre-therapie. Maarssen, Elsevier gezondheidszorg, pp.81–135.

- Rahnama, F., Hamedi, F. R.M., Shahraei, F. and Parto, E. 2014. Effectiveness of play therapy (lego therapy) on behaviour problems in children. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 5, 1040–1086.

- Ray, D. C., Armstrong, S. A., Balkin, R. S. and Jayne, K. M. 2015. Child-centerd playtherapy in the schools: Review and meta-analysis. Psychology in the Schools, 52, 107–123.

- Ray, D. C., Blanco, P. J., Sullivan, J. M. and Holliman, R. 2009. An exploratory study of child-centered play therapy with aggressive children. International Journal of Play Therapy, 18, 162–175.

- Rogers, C. R. 2012. Mens worden. Een visie op persoonlijke groei. Utrecht: Bijleveld.

- Ritzi, R. M., Ray, D.C. and Schumann, B.R. 2017. Intensive short-term child-centered play therapy and externalizing behaviours in children. International Journal of Play Therapy, 26, 33–46.

- Russ, S. 2004. Play in child development and psychotherapy: Toward empirically supported practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Schumann, B. 2010. Effectiveness of child-centered play therapy for children refered for aggresion. In D. D. Baggerly, ed. Child-centered play therapy research:The evidence base for effective practice. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, pp.193–2008.

- Seymour, J. W. 2014. Resiliency as a therapeutic power of play. In: C.E. Schaefer and A.A. Drewes, eds., The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Seymour, J. W. 2018. Chaper 2: Veerkrachtversterkende factoren in speltherapie. In: D.B. Crenshaw, ed. Veerkracht versterken met speltherapeutische interventies. Amsterdam: SWP, pp. 41–54.

- Schaefer, C.E. and Drewes, A. A. 2014. The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Stewart, A. L. and Echterling, L. G. 2014. Therapeutic relationship. In: C.E. Schaefer and A.A. Drewes, eds. The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Swan, K. L. and Ray, D. C. 2014. Effects of child-centered play therapy on irritability and hyperactivity behaviours of children with intellectual disabilities. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 53, 120–133.

- Swan, K. S. and Ray, D.C. 2015. Contact work in child-centered Play Therapy: A case study. Person-Centered and Experiental Psychotherapies, 268–284.

- Swank, J. C., Cheung, C. and Williams, S.A. 2018. Play therapy and psychoeducational school-based group interventions: A comparison of treatment effectiveness. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 43, 230–249.

- Tenneij, N., Didden, R., Stolker, J. and Koot, H. 2009. Markers for aggression in inpatient treatment facilities for adults with mild to borderline intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 1248–1257.

- Vanfleet, R. and Mochi, M. 2018. Hoofdstuk 8: Speltherapie bij kinderen en gezinnen die een massa trauma meemaakten. In: D.B. Crenshaw, ed. Veerkracht versterken met speltherapeutische interventies. Amsterdam: SWP, pp.163–187.

- van de Witte, M. B., Bellemans, T., Tukker, K. and Hooren van, S.A. 2017. Vaktherapie. In J.J. Bruijn, ed. Handboek emotionele ontwikkeling en verstandelijke beperking. Amsterdam: Boom, pp.277–291.

- van Hooren, S. W., Witte de, M., Didden, R. and Moonen, X. 2016. Vaktherapie. In: R. T. Didden, ed. Handboek Psychiatrie en lichte-verstandelijke beperking. Utrecht: De Tijdstroom, pp. 425–469.

- van Yperen, T.A. and van der En Steege, M. 2006. Voor het goede doel. Amsterdam: SWP.

- Wampold, B. E. and Imel, Z. E. 2015. The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

- Wilson, B. J. and Ray, D.C. 2018. Child-centered play-therapy: Aggression, empathy, and self-regulation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96, 399–409.

- Winburn, A., Perepiczka, M., Frankum, J. and Neal, S. 2020. Play therapists’ empathy levels as a predictor of self-perceived advocacy competency. International Journal of Play Therapy, 29, 144–154.

- Yeager, M. and Yeager, D. 2014. Self-regulation. In: C.E. Schaefer and A.A. Drewes, eds. The therapeutic powers of play: 20 core agents of change. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley.