Abstract

Positive Behaviour Support is an applied behaviour analytic system of support that is utilised in schools and in residential care settings for children and adults with disabilities who engage in challenging behaviour. Implementation fidelity depends on appropriate staff training and organisational behaviour management. A systematic literature review is reported that evaluated the evidence in relation to change in staff and service user behaviour and the impact of organisational behaviour management systems on effectiveness, generalization, and maintenance of these outcomes. Nine relevant articles were identified and analysed according to (1) the demographics of staff and residents and methods of staff training; (2) organisational behaviour management systems; (3) staff and service-user behavioural outcome measures; and (4) the methodological quality of the study. A combination of antecedent and consequence-based training strategies was used in the studies. Eight studies reported on the organisational behaviour management systems that were used, with five reporting on the responsibility of trainees to transfer their training to their untrained teams (pyramidal training). Although the studies reported on staff behaviour change following the training, only one of the studies reported significant increases of service user quality of life as a result of staff training and only two studies provided adequate methodological strength.

Introduction

Positive behaviour support (PBS) is a multicomponent framework for supporting people with intellectual disabilities who engage in behaviour commonly described as challenging (Gore et al., Citation2013). PBS is one of many applications of the science of behaviour analysis (NICE, Citation2015). Like other natural sciences, behaviour analysis has three interconnected branches: the conceptual analysis of behaviour (radical behaviourism), the experimental analysis of behaviour (EBA), and the application of the science, applied behaviour analysis (ABA) (Cooper et al., Citation2019). ABA is ‘the science in which tactics derived from the principles of behavior are applied systematically to improve socially significant behavior, and experimentation is used to identify the variables responsible for behavior change’ (Cooper et al., Citation2019, p.3). PBS utilises ABA-based procedures to focus on

developing a functional assessment of the social and physical context within which challenging behaviour occurs; including direct behavioural observations, interviews, record reviews, and behaviour rating scales;

the inclusion and involvement of key stakeholders, including the family, friends, other family members, care staff and/or therapists;

developing, implementing, and evaluating the effectiveness of comprehensive person-centred systems of support aimed at enhancing the quality-of-life of the person using procedures including

a clear description of the targeted behaviour, triggers or antecedents of the behaviour, maintaining consequences, and the function of the problem behaviour,

strategies to reduce the probability of the problem behaviour, including environmental arrangements, personal support, changes in activities, prompts, and changes in expectations,

teaching of skills to replace the problem behaviour, use positive reinforcement for promoting appropriate behaviour, and ensuring behaviour generalizes and is maintained via developing friendships and getting involved in the community (Gore et al., Citation2013, p.15; NCPMI, Citation2022).

In concord with disability rights and relevant government guidelines, PBS focuses on value-based, theory-driven, evidence-base practice (Beadle-Brown and Murphy, Citation2016, Denne, Citation2015). The quality of PBS services depends to an important extent on the skills of front-line staff (Reed and Henley Citation2015). While staff in education settings usually are teacher trained or receive training as teaching assistant, commonly, frontline staff in residential care settings do not hold recognised professional qualifications. Residential staff usually receive in-house, on the job training, either specifically in PBS philosophy and procedures or more generally in the overarching scientific discipline of ABA (Gormley et al., Citation2020). The quality and effectiveness of this training and the organisational behaviour management (OBM) systems in place to ensure intervention fidelity directly affect services user outcomes (Reed and Henley, Citation2015), including their social engagement (Szczech, Citation2007) and quality of life (Jahr, Citation1998). OBM applies behaviour analytic knowledge to performance management, system analysis and behaviour-based safety (Agnew and Uhl, Citation2021, Daniels, Citation2000, Daniels and Bailey, Citation2015).

The traditional ‘train and hope’ approach (Stokes and Baer Citation1977) is not effective and can even have a negative impact on service delivery (Campbell Citation2007). In contrast, there is ample evidence that behavioural skills training can be effective (Campbell Citation2010; Griffin et al., Citation2019). However, a number of barriers remain, such as a lack of measures to ensure intervention fidelity and a failure to ensure generalization of new skills across the team (Smith et al. Citation1992). Consequently, MacDonald et al. (Citation2018) identified the need for a ‘whole organization’ approach to staff training. This approach does not only include behaviour skills training for individual staff, it also includes the identification of effective OBM processes to ensure training leads to the desired outcomes.

The impact of staff training on behavioural skills has been explored in a number of reviews (Gormley et al. Citation2020, MacDonald and McGill Citation2013, Shapiro and Kazemi Citation2017) and meta-analyses (van Oorsouw et al. Citation2009). Most of these studies focused on teaching specific behavioural intervention procedures, rather than educating staff in an overarching scientific framework. For example, Shapiro and Kazemi (Citation2017) reported that training in token economy or discrete trial teaching (DTT) resulted in increased staff skills in these procedures, meeting mastery criteria in 18 of the studies. Gormley et al. (Citation2020) reported a scoping review of studies regarding antecedent-based procedures and found that most studies reported improved staff skills with regards to these procedures. Van Oorsouw et al. (Citation2009) conducted a meta-analysis and concluded that overall staff training was effective.

In sum, while the effectiveness of staff training in commonly used procedures is relatively well documented, outcomes for clients regarding quality of life or reduction of challenging behaviour are reported less often (MacDonald and McGill Citation2013). Furthermore, little is known about the OBM structures used to support effective long-term outcomes of staff training. The objective of the present systematic literature review was to analyse outcomes of staff training in relation to overarching frameworks (i.e. PBS and/or ABA) and service-user outcomes and to assess the impact of different OBM systems. Given that Dickinson (Citation2001) covered the historical roots of OBM earlier, the present review covered studies published since then.

Methodology

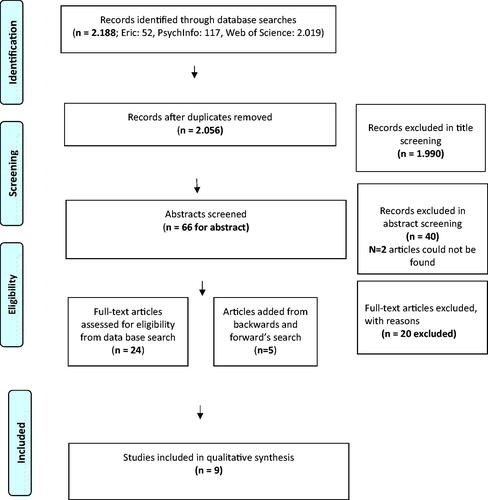

The search methods used in this review were based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework and findings are reported according to the PRISMA checklist (Moher et al. Citation2009) ().

Inclusion and/exclusion criteria

To be included in this review, the study had to be conducted within a social care setting (including residential services, community-based programmes, training providers for disability services) for adults with intellectual disabilities and

be peer-reviewed and published in English between 2000 and 2021;

describe staff training in PBS and/or ABA, as the independent variable;

report on outcomes for at least one of the following: quality of staff skills, quality of behaviour support plans, and fidelity of implementation of intervention.

Studies were excluded if

the independent variable of the study was training on only one specific behavioural procedure (e.g., Discrete Trial Training; most-to-least prompting);

they described school-wide PBS or training for staff in formal school settings;

they described training for staff only in specific professional roles e.g., social workers, speech and language therapists (unless the training met inclusion criteria);

they described training of staff who already had qualifications in ABA, for example, a degree in behaviour analysis;

they included parents training;

they were systematic reviews, process reviews, and grey literature.

Screening procedures

Searches of electronic databases (ERIC, PsycINFO, Web of Science) were conducted in June 2021. The following search terms were used: ‘positive behavio* support’, ‘PBS’, ‘applied behavio* analysis’, ‘ABA’, and ‘staff train*’. The terms were combined using variations of Boolean operators, according to each database. Specifically:

for Eric (‘positive behavio* support’ or pbs) AND staff N3 train* and (‘applied behavio* analysis’ or aba) and staff N3 train*,

for PsychInfo (‘positive behavio* support’ or pbs) AND staff adj3 train* and ‘applied behavio* analysis’ or aba) AND staff adj3 train*,

for the Web of Science: ‘applied behavio* analysis’ or aba and ‘staff NEAR/3 train*’ and ‘positive behavio* support’ or pbs and ‘staff NEAR/3 train*’.

The search resulted in 2188 articles (Eric: 52, PsychInfo: 117, Web of Science: 2019). After removing all duplicates, a total of 2056 studies remained. Title screening excluded 1990 studies. Of the remaining 66 studies, 42 were excluded during abstract screening, including 2 studies that did not have an abstract. This resulted in 24 studies eligible for full text screening. Forward and backwards searches were conducted, including searching for additional published research by the first author of these 24 studies, searching the reference sections of these 24 articles, and searching Google Scholar. An additional five studies were identified. Therefore, full text screening was conducted for 29 studies and this resulted in the exclusion of a further 20 studies. Nine studies met all the inclusion criteria ().

Inter-rater reliability

Inter-rater reliability checks were conducted by the first author as well as another Board-Certified Behaviour Analyst. Inter-rater reliability was assessed for 50% of the studies that were eligible for full text screening (inter-rater reliability = 93.33%.). Inter-rater reliability also was calculated for the data extraction of all categories in 30% of the studies. This resulted in 100% inter-rater reliability for the general and training information, 90% inter-rater reliability for the outcomes, and 80% inter-rater reliability for organisational systems. For the quality assessment of the studies, the criteria were discussed with a second rater until 100% agreement was achieved. The IOA for the quality assessment was 93.33%.

Categories for analysis

Apart from general and demographic information about staff training (i.e. participants, setting, type of training, length of training, country in which the study took place) information was extracted for behavioural outcomes (staff and service users) and organisational systems.

Behavioural outcome categories for staff included their knowledge (i.e. theoretical, factual, procedural, value-based) and skills (i.e. practical, interpersonal, technical, problem-solving), the overall quality of support they provided including the fidelity of implementation of the interventions, and the quality of the behaviour support plans they designed. Information on other outcomes including staff attitudes and beliefs were also provided.

The measurement systems used for the quality of staff skills, quality of behaviour support plans and fidelity of implementation of interventions were also included. All outcomes for residents were analysed, regardless under which category they were reported in an article.

OBM systems were categorised according to Gravina et al. (Citation2018) into those that used antecedent-based strategies and those that used consequence-based strategies. Antecedent-based strategies were strategies that were in place before or at the beginning of the training and included:

Assessment (Assess), such as collecting and using data to identify training needs or OBM systems in place to reinforce training outcomes;

Training for staff in supervisory roles (super.roles);

Clarification of responsibility for generalization of learning across the whole team (respons.), such as train the trainers model or training to implement of specific training goals;

Other antecedent-based strategies that were implemented prior to or at the beginning of training, which do not meet criteria for the categories described above. For example, ‘prompts’ or other supports to reinforce the training and the desired outcomes or ‘change in resource availability’ (for example, reducing trainees’ responsibilities).

Consequence-based strategies were those that were in place as part of longitudinal training or after the completion of staff training. These included

Monitoring/feedback systems (mon/feed systems) that were in place continuously to evaluate training outcomes and systems to deliver performance feedback after the training. Monitoring systems that were used only by the researcher of the study or external trainers were not included;

Other consequence-based interventions in place to reinforce implementation or generalization of training outcomes.

Brief information about the effectiveness of each study regarding the target outcomes was provided. Outcomes were scored as positive, if they led to a significant change. Information was also provided for the studies that reported results on maintenance (i.e. after the post-training phase) and generalization of the staff skills to the staff group.

The overall quality of the studies was assessed using Reichow et al.’s (Citation2008, Reichow et al Citation2011) evaluative method for determining evidence-based practices (EBP) in autism. Reichow et al. propose three levels of assessment:

rubrics for the evaluation of research report rigor;

guidelines for the evaluation of research report strength; and

criteria for the determination of EBP.

Research rigor assessment was similar for group research and for single subject research. Common primary quality indicators included participant characteristics, dependent measures, and independent variables; common secondary quality indicators including interobserver agreement, blinding of raters, procedural fidelity, generalization and maintenance, and social validity. Research strength was assessed on three levels: strong (provide concrete evidence of high quality), adequate (showing strong evidence in most, but not all areas), and weak (many missing elements, and/or fatal flaws). Finally, criteria for the determination of EBP included two categories: established EBP and promising EBP. Established EBP were effective across multiple strong studies conducted by at least two independent research groups, while promising EBP were effective across multiple studies but there was some evidence that practice was limited by weak methodological rigor, few replications, or an inadequate number of independent researchers demonstrating the effects (Reichow et al. Citation2008)

Results

General information

The studies reviewed included a total of 876 members of staff, including managers and frontline staff, as well as 202 adults with intellectual disabilities (). The training was carried out mainly in large-scale statutory and voluntary sector residential settings, located in the community or in hospital settings. The main training methods were pyramidal style ‘train the trainer’, with some of the programmes focussing on staff skills development while others focussed on system-wide interventions. Most of the training was relatively short-term, over fewer than 5 days, while some of the maintenance training stretched over 9-12 months.

Table 1. General and training information.

Staff skills outcomes

The impact of training on staff skills () was assessed through the quality of behaviour support plans in four studies (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017, Wardale et al. Citation2014), the implementation of behavioural strategies and/or behaviour support plans in four studies (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McKenzie et al. Citation2002), the quality of support in two studies (MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McGill et al. Citation2018), and through other competency assessments in two studies (Haberlin et al. Citation2012, Reid et al. Citation2003).

Table 2. Type of outcomes and measurement systems for staff overt behaviour.

The studies that reported on the quality of behaviour support plans, used three different evaluation systems. Crates and Spicer (Citation2012) used the Assessment and Intervention Plan Evaluation Instrument (AIEI; LaVigna et al. Citation2005). Dench (Citation2005) used the Callan Institute version of the Behaviour Assessment Report and Intervention Plan Evaluation Instrument (Willis and LaVigna Citation1990). O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2017) used direct observations via the first author assessing the behaviour support plans prior and 12 months post staff training, while Wardale et al. (Citation2014) used observations by facilitators after the training without collection of pre-training data. Only two of the studies used the same assessment tool; The Behaviour Support Plan Quality Evaluation-II (BSP QE-II; Browning-Wright et al. Citation2006). Three studies included two outcome measures each (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, MacDonald et al. Citation2018).

To evaluate the fidelity of implementation of behaviour strategies and/or intervention plans, four of studies used the Periodic System Review (PSR; LaVigna Citation1994). For example, MacDonald et al. (Citation2018) used the PSR to evaluate the performance for both direct care staff and their managers. McKenzie et al. (Citation2002) used specific tasks to assess fidelity for 14 trainees prior to training as well as 16 and 20 weeks after the training.

The quality of staff support was reported in two studies (MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McGill et al. Citation2018) using the Active Support Measure (ASM; Mansell et al. Citation2005). The ASM is an observer completed rating scale, that provides ratings for staff support during activities and choice making. Data were collected during baseline and 3-6 months follow-up.

Other competence-based skills were reported in two studies. Haberlin et al. (Citation2012) reported percentage of correctly applied teaching procedures for direct care staff, after training their supervisors, while Reid et al. (Citation2003) reported on 26 sets of skills of supervisors. In both cases, checklists were used during observations to record the competence on the relevant skills. In both studies staff skills were assessed on the job, while Reid et al. (Citation2003) also assessed the target skills during role play.

Most studies that explicitly focussed on staff outcomes reported improvements. Crates and Spicer (Citation2012) found the quality of reports reached a mean AIEI score of 79.5% (range 44%-94%) for training in 2006, and a mean AIEI score of 80.2% (range 64%-92%) in 2008. Their mean PSR score was 47% (range 19%-86%). Dench (Citation2005) reported that trainees achieved an average of 91.7% across all units (the success criterion was 85%) while PSR were not reported. Haberlin et al. (Citation2012) found that for both groups of direct care staff, percentage of correct teaching and knowledge increased, although it improved more for the pyramidal training group. These gains were maintained at 3-months follow up. MacDonald et al. (Citation2018) reported no significant improvement in skills for staff and managers, however, knowledge increased significantly for managers in the experimental group.

McGill et al. (Citation2018) reported positive ASM scores increased in 7/9 settings and mean percentage of engagement increased, but not significantly. McKenzie et al. (Citation2002) found that PSR scores increased from 26% pre-training to 74% at 16 weeks after training; 20 weeks after training, these improvements increased to 95%. However, they found no significant changes in staff attributional dimensions but staff rated their knowledge levels as higher both immediately following training and 8 weeks later. O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2017) reported that the behaviour support quality increased (statistically significant improvement compared to control group). However, the quality of behaviour support plans of the trained group remained below optimal levels. No significant change was reported with regards the use of chemical restraint. Reid et al. (Citation2003) reported that 85% of staff successfully completed the training by performing all classroom and on-the-job skills checks at mastery criterion. All classroom probes were successful although frequently several observation and feedback sessions were required. Finally, Wardale et al. (Citation2014) achieved positive results for support plan quality, significant change in causal attributions and staff knowledge, but no significant difference with evidence-based practices.

Service user outcomes

Service user outcomes with regards to the reduction in challenging behaviour were reported in five studies (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McGill et al. Citation2018, O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017). Only three studies reported on changes in residents’ quality of life (Dench Citation2005, MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McGill et al. Citation2018) and one study reported on changes in mental health (O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017). Crates and Spicer (Citation2012) demonstrated a statistically significant reduction of targeted challenging behaviour at 3-month follow-up for 27/30 service users. Dench (Citation2005) reported that 56% cases presented with significant improvements with regards to challenging behaviour (defined by reduction to less than 30% of baseline) within three months of training. They argued that the Quality-of-Life Questionnaire (Schalock and Keith 1993) was insufficiently sensitive to measure some of the anecdotal evidence. MacDonald et al. (Citation2018) achieved a significant reduction in challenging behaviour, however reported no significant increase for quality of life at 6-months follow up. McGill et al. (Citation2018) reported that challenging behaviour reduced significantly more in the experimental group than in the control group and that the difference between these groups was maintained at follow-up. They found no significant difference between the groups in terms of quality of life. O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2017) did not achieve a significant change for severity of challenging behaviour, however, they reported statistically significant change in client mental health.

Other outcomes

Other outcomes that were not the focus of the present review, for example outcomes for staff knowledge, attitudes, or beliefs, were reported in 8 studies. Specifically, 4 studies reported on staff knowledge (Haberlin et al. Citation2012, MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McKenzie et al. Citation2002, Wardale et al. Citation2014), 3 studies reported on staff attitudes or beliefs, including challenging behaviour attribution and evidence-based practice attitude (MacDonald et al. Citation2018, McKenzie et al. Citation2002, Wardale et al. Citation2014); three studies reported the outcomes for the organization, including cost effectiveness, referral data, and quality of support (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, McGdaill et al. Citation2018); one study reported the use of physical restraints (O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017); and one study focussed on practice leadership (MacDonald et al. Citation2018).

Organisational behaviour management systems

Organisational behaviour management (OBM) strategies were considered according to strategies that were used; either antecedent-based (e.g. training of supervisors; allocation of responsibility to trainees; prompts; additional resources) and/or consequence-based (e.g. monitoring, feedback) (). Five studies evaluated the use of two antecedent OBM strategies (inclusion of supervisors in staff training and allocating responsibility to generalize learning) (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Haberlin et al. Citation2012, MacDonald et al. Citation2018, O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017, Reid et al. Citation2003). McGill et al. (Citation2018) used three antecedent strategies (including supervisors in training, prompts, and change in resource availability), while two studies (Dench Citation2005, Wardale et al. Citation2014) reported only one antecedent strategy (training supervisors). From those studies, only one (Wardale et al. Citation2014) did not report the use of consequence based OBM strategy (monitoring, feedback). McKenzie et al. (Citation2002) did not describe any organisational supporting systems in place to assist the staff training outcomes.

Table 3. Organisational systems in combination with training.

Training staff for their supervisory roles generally is considered part of a system-wide staff training process (Reid et al. Citation2003) and this was recorded in all studies, except McKenzie et al. (Citation2002). Wardale et al. (Citation2014) did not use this as inclusion criteria for their study, but reported on multidisciplinary staff (i.e. allied health professionals, direct support workers, and team leaders) who had attended the training. Dench (Citation2005) was the only study that did not specifically target staff in supervisory roles, while McGill et al. (Citation2018) was the only study to describe training for both managers and direct care staff.

The responsibility to generalize training outcomes within the team was described in five studies in different ways. In two studies, the ‘train the trainer’ model was assessed (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Haberlin et al. Citation2012), while two of the studies (MacDonald and McGill Citation2013, O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017) described practice-based training, where the individuals in supervisory roles had the responsibility to ensure generalisation of new skills across the team. Reid et al. (Citation2003) was the only study that measured supervisor competency to train font-line staff in specific skills.

Consequence-based systems that included monitoring and feedback were reported in seven of the studies and this included monitoring performance, evaluating intervention fidelity, or mentoring regarding specific staff behaviours as part of maintenance procedures. For example, Macdonald and McGill (Citation2013) included PSR in their manager training to ensure ongoing evaluation regarding the organisation of team meetings and monitoring staff performance via direct observations. The results of the PSR were presented to the team with graphs to deliver visual feedback. O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2017) used the BSP QE-II, in order to assess the quality of behaviour support plans, including staff communication about their implementation. McGill et al. (Citation2018) used a traffic light system to monitor progress. Although initially the feedback to the managers was completed by the researchers, in the end their support was faded, and managers acquired this new responsibility. There was no detailed description exactly how staff training was conducted.

Another approach to monitoring performance and delivering performance-based feedback was reported by Reid et al. (Citation2003), who trained supervisors to conduct evaluative observations and provide feedback and performance-based staff training. Haberlin et al. (Citation2012) instructed the pyramidal training group of supervisors to deliver performance-based feedback while the direct care staff group did not receive this training. Finally, Dench (Citation2005) used a quality assurance process with responsibility for supervisors of the trainees.

Only two studies reported on OBM outcomes. Crates and Spicer (Citation2012) found that the priority of referrals reduced from 100% Priority 1 in the first year of training to 25% after training. McGill et al. (Citation2018) reported that the quality of service improved and achieved a median percentage after training of 80.1% in each setting.

The two studies (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Haberlin et al. Citation2012) that applied a pyramidal ‘training the trainer’ model described at least one positive target outcome for staff. Crates and Spicer (Citation2012) found that first-generation trainees were able to successfully train second-generation staff to produce good quality reports. The study also demonstrated positive outcomes for residents, including the reduction of challenging behaviour and anecdotal evidence of improvements of quality of life. A decrease in severity rating was reported also as a positive outcome for the organisation.

Haberlin et al. (Citation2012) compared the outcomes of ‘train the trainer’ with group training of staff. The group-based training led to positive staff outcome, although the pyramidal training was more positive for all staff outcomes, including staff knowledge, practical skills, and maintenance of learning. In a similar cascade approach described by Macdonald et al. (Citation2018), first level managers were trained and the impact on this training was assessed for the managers, their staff teams, and their service users. However, the training did not demonstrate significant change in any of their behaviour, although there was an increase in manager’s knowledge and a reduction of residents’ challenging behaviour. No significant change was reported for residents’ quality of life.

Other studies that used supervisor training reported less effect. For example, O’Dwyer et al. (Citation2017) assessed the impact of training supervisors, who then were asked to communicate their learning to their team. Although, compared to the control group, statistically significant improvements were reported regarding the quality of behaviour support plans and their implementation, these findings remained below optimal levels. Furthermore, the authors did not report significant change in the use of chemical restraint or the severity of challenging behaviour, but they reported significant change in client’s mental health. Reid et al. (Citation2003) focused on supervisor competence rather than the effect on other staff and reported that, after training, 85% of the supervisors successfully performed all on-the-job skills checks.

McGill et al. (Citation2018) was the only study that used more than two antecedent-based strategies. They described a setting-wide intervention, using a cluster randomized controlled trial that included a briefing meeting with the staff and management team, an assessment of provider needs, including staff training needs, additional resource by having researcher conducting the intervention, and a traffic light system to monitor staff performance. The quality of care improved for the training group and challenging behaviour of residents reduced significantly. These improvements were maintained at follow up. However, compared with the control group, residents’ quality of life did not improve significantly.

The only organisational system used by Wardale et al. (Citation2014) was to include trainees in supervisory roles along with other staff with the results that staff causal attributions and staff knowledge changed significantly but there was no significant difference regarding attitudes to evidence-based practices.

McKenzie et al. (Citation2002) did not report any organisational systems to support staff training. Their training consisted of a one-day course regarding challenging behaviour. They reported positive outcomes for maintenance of staff knowledge and practice skills, as staff self-scored their knowledge as higher both immediately after training and eight weeks later. These perceptions were confirmed 16 weeks after training when the PCR score had increased from 26% to 74% and 20 weeks after training when the score had increased to 95%.

Social validity

Social validity was reported by Crates and Spicer (Citation2012), staff satisfaction was assessed by Dench (Citation2005) and Haberlin et al. (Citation2012), training was evaluated by McGill et al. (Citation2018) and Wardale et al. (Citation2014), and training acceptability was assessed by Reid et al. (Citation2003). Findings were positive for all of these studies.

Crates and Spicer (Citation2012) used the Social Validity Survey (SVS; LaVigna et al. Citation2005) and found that the total mean for all SVS item scores was 88.3% (range of 69.2%-98.5%); for their 2006 Tasmanian cohort the mean score was 89.8% (range 77%-97%); for the 2008 Tasmanian cohort the mean score was 84.8% (range 76%-94%). Dench (Citation2005) assessed staff satisfaction of staff and found that 94% of staff rated the course as ‘very relevant’. Haberlin et al. (Citation2012) used a satisfaction survey and reported positive results for both groups, with higher scored for the consultant-led training. McGill et al. (Citation2018) used a one-page questionnaire for the overall evaluation that was completed by staff, family members professionals and found overall positive ratings. Reid et al. (Citation2003) used an acceptability questionnaire and got positive results with 95% of trainees reporting the training to have been extremely or very useful. Finally, Wardale et al.’s (Citation2014) evaluation questionnaire also produced positive results.

Quality assessment of the studies

The overall quality of the studies was assessed using Reichow et al.’s (Citation2008; cf., Reichow et al. Citation2011) evaluative method for determining evidence-based practices (EBP) in autism (). One study was rated as ‘strong’ (McGill et al. Citation2018) and one as ‘adequate’ (Macdonald et al. Citation2018). These studies reported good interobserver agreement (IOA), good levels of generalization and maintenance, and high levels of social validity. McGill et al. (Citation2018) also reported randomization, attrition, and effect size.

Table 4. Quality assessment according to Reichow et al. (Citation2011).

The remaining seven studies were rated as ‘weak’ due to an ‘unacceptable score’ for at least one of the primary indicators. Five of these studies failed to report a comparison condition (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, McKenzie et al. Citation2002, O’Dwyer et al. Citation2017, Wardale et al. Citation2014), while four studies did not provide adequate information for participants characteristics (Crates and Spicer Citation2012, Dench Citation2005, Haberlin et al. Citation2012, Reid et al. Citation2003), and two studies failed to include statistical analysis (Dench Citation2005, Reid et al. Citation2003). Furthermore, these studies received a negative score for at least four secondary indicators. None of those studies reported randomization for group allocation, raters being blinded to the treatment condition, procedural fidelity, or criteria for attrition. Two of these studies provided information for generalization and/or maintenance (Haberlin et al. Citation2012, McKenzie et al. Citation2002), three studies reported interobserver agreement (IOA; Haberlin et al. Citation2012, Reid et al. Citation2003, Wardale et al. Citation2014), and all of them reported social validity. Finally, acceptable effect size was reported in all those studies, expect in Dench (Citation2005).

Discussion

The present review identified nine studies that reported results of staff training in the general PBS framework and/or the whole science approach of ABA and analysed these studies according to a) general study and training information, b) type of outcomes and measurement systems, c) organisational behaviour management (OBM) systems in place related to staff training, d) effectiveness of the training, and e) quality of the studies. Although the variety of training methods, OBM systems, and outcome measures make a direct comparison between studies difficult, overall, training appeared to have a positive effect on staff knowledge and practice skills, especially with regards to developing and implementing behaviour support plans.

Interestingly, only few studies included specific behavioural resident outcomes or more general residents’ quality of life measures. They also lacked focus on stakeholder outcomes. This lack of focus on residents was particularly conspicuous in the context of PBS claims regarding person-centred processes, values, and disability rights as well as stakeholder involvement, where one would expect research to be particularly focussed on outcomes for residents and stakeholder. The studies that reported positive outcomes considered mainly a reduction in challenging behaviour. Measurable improvements with regards to quality of life were not demonstrated, although it was not clear whether this was due to inclusion criteria in this review, or the difficulties in measurement, lack of attention to detail, or lack of progress. Clearly, this gap in the research literature should be addressed in future studies reporting more precisely on behavioural outcomes for residents as well as stakeholders.

A number of OBM processes were utilised in the studies. These included antecedent as well as consequence-based procedures. Generally, the pyramidal ‘train the trainer’ systems seemed to work well, but a number of questions remained. For example, it was not clear, if those responsible for training second-generation staff were given specific instruction to do so, or equally, if the second-generation staff were expecting to learn from those who had received the initial training. None of the studies described replicable procedures for this cascading process. Future research should explore these issues as findings would be of interest of researchers in OBM more generally, who intend to use the pyramid system to train their staff (Dillenburger Citation2016). The question is whether or not untrained staff learn from trained staff without added instruction to do so (e.g. model learning; Cooper at al. 2019), or if specific procedures may be necessary to ensure pyramidal learning takes place (Daniels Citation2000, Daniels and Bailey Citation2015). While other antecedent and consequence-based OBM strategies were used, the description of those systems also was not always clear enough to allow replication. Given the growing pool of OBM research especially in relation to occupational safety (Agnew and Uhl Citation2021), it would be important in future studies that procedures are described in enough detail to allow for replication.

With regards to the evaluation of the strength of the studies, it is important to remember that this kind of research is conducted in residential settings were the strict criteria, such as randomisation and blinding commonly are impossible to achieve (Keenan and Dillenburger Citation2011). Other criteria, such as detailed description of diagnostic processes, also often are not available in applied studies of adults in residential care, given that most of these residents would have been diagnosed as children and entered residential care as adults (Dillenburger and McKerr Citation2011). As such, their exact diagnostic history often remains unknown. Therefore, the categorisation of the studies included in this review should be viewed cautiously. A more flexible categorisation system would likely conclude that most of these studies are strong enough to support the concept of staff training in residential care for adults with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour. In fact, findings reported here largely confirm those reported in previous reviews (Gormley et al. Citation2020, MacDonald and McGill Citation2013, Shapiro and Kazemi Citation2017) and meta-analyses (van Oorsouw et al. Citation2009) that had concentrated on specific behavioural intervention procedures. Evidently, staff training in the PBS framework and/or training in the overarching science of behaviour analysis can have an impact on staff behaviour as well as residents’ outcome. Future studies would need to try and achieve stronger methodological rigour to ensure that the existing evidence gains in credibility.

Acknowledgement

This study was conducted in part fulfilment of doctoral research by the first author under the supervision of the second author (1st supervisor) and third author (2nd supervisor).

Conflict of interest

The authors are board certified behavior analysts and have no financial or other conflict of interest in the data reported here.

References

- Agnew, J. and Uhl, D. 2021. Safe by design. A behavioral systems approach to human performance improvement. Atlanta: Aubrey Daniels International.

- Beadle-Brown, J. and Murphy, B. 2016. What does good look like? A guide for observing in services for people with learning disabilities and/or autism. United Response and Tizard Centre 38.

- Browning-Wright, D. Mayer, G. and Saren, D. 2006. The Behaviour Support Plan Quality Evaluation Quide-Version II.

- Campbell, M. 2007. Staff training and challenging behaviour: Who needs it? Journal of Intellectual Disabilities: JOID, 11, 143–156.

- Campbell, M. 2010. Workforce development and challenging behaviour: Training staff to treat, to manage or to cope? Journal of Intellectual Disabilities: JOID, 14, 185–196.

- Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E. and Hw, L. 2019. Applied behavior analysis. 3rd ed. Hoboken: Pearson Education.

- Crates, N. and Spicer, M. 2012. Developing behavioural training services to meet defined standards within an Australian statewide disability service system and the associated client outcomes. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37, 196–208.

- Daniels, A. C. 2000. Bringing out the best in people. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Daniels, A. C. and Bailey, J. S. 2015. Performance management: changing behavior that drives organizational performance. Atlanta: Performance Management Publications.

- Dench, C. 2005. A model for training staff in positive behaviour support. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 10, 24–30.

- Denne, L. 2015. Positive Behavioural Support (PBS) Coalition UK Positive Behavioural Support A Competence Framework. <www.pbsacademy.org.uk> [Accessed February 20, 2022].

- Dickinson, A. M. 2001. The historical roots of Organizational Behavior Management in the private sector. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 20, 9–58.

- Dillenburger, K. 2016. Staff training. In Handbook of autism treatments. Autism and child psychopathology series. New York: Springer, pp. 95–107.

- Dillenburger, K. and McKerr, L. 2011. “How long are we able to go on?” Issues faced by older family caregivers of adults with disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, 29–38.

- Donnellan, A. M., LaVigna, G. W., Zambito, J. and Thvedt, J. 1985. A time limited intensive intervention program model to support community placement for persons with severe behavior problems. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 10, 123–131.

- Gore, N. J., McGill, P., Toogood, S., Allen, D., Hughes, J. C., Baker, P. A., Hastings, R. P., Noone, S. J. and Denne, L. D. 2013. Definition and scope for positive behavioural support. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 3, 14–23.

- Gormley, L., Healy, O., Doherty, A., O’Regan, D. and Grey, I. 2020. Staff training in intellectual and developmental disability settings: A scoping review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32, 187–212. Springer

- Gravina, N., Villacorta, J., Albert, K., Clark, R., Curry, S. and Wilder, D. 2018. A literature review of organizational behavior management interventions in human service settings from 1990 to 2016. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 38, 191–224.

- Griffin, M., Gravina, N. E., Matey, N., Pritchard, J. and Wine, B. 2019. Using scorecards and a lottery to improve the performance of behavior technicians in two autism treatment clinics. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 39, 280–292.

- Haberlin, A. T., Beauchamp, K., Agnew, J. and O'Brien, F. 2012. A comparison of pyramidal staff training and direct staff training in community-based day programs. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 32, 65–74.

- Jahr, E. 1998. Current issues in staff training. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 19, 73–87.

- Keenan, M., Dillenburger, K. 2011. If all you have is a hammer …RCTs and hegemony in science. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1–13.

- Lavigna, G. and Willis, T. 2005. A positive behavioural support model for breaking the barriers to social and community inclusion. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 10, 16–23.

- LaVigna, G. W. 1994. The Periodic service review: a total quality assurance system for human services and education. Baltimore: P.H. Brookes Pub. Co., pp. 234.

- LaVigna, G. W., Christian, L. and Willis, T. J. 2005. Developing behavioural services to meet defined standards within a national system of specialist education services. Pediatric Rehabilitation, 8, 144–155.

- MacDonald, A. and McGill, P. 2013. Outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support: A systematic review. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 25, 17–33.

- MacDonald, A., McGill, P. and Murphy, G. 2018. An evaluation of staff training in positive behavioural support. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities: JARID, 31, 1046–1061.

- Mansell, J., Elliott, T. E. and Beadle-Brown, J. 2005. Active support measure (Revised). Canterbury: Tizard Centre.

- McGill, P., Vanono, L., Clover, W., Smyth, E., Cooper, V., Hopkins, L., Barratt, N., Joyce, C., Henderson, K., Sekasi, S., Davis, S. and Deveau, R. 2018. Reducing challenging behaviour of adults with intellectual disabilities in supported accommodation: A cluster randomized controlled trial of setting-wide positive behaviour support. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 81, 143–154.

- McKenzie, K., Sharp, K., Paxton, D. and Murray, G. C. 2002. The impact of training and staff attributions on staff practice in learning disability services: A pilot study. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6, 239–251.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. and Altman, D. G. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 339, b2535.

- National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations (NCPMI). 2022. The Positive Behavior Support process: Six steps for implementing PBS. <https://www.challengingbehavior.cbcs.usf.edu/Pyramid/pbs/process.html>

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). 2015. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: Prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges | Guidance and guidelines | NICE. <https:////www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11>

- O’Dwyer, C., McVilly, K. and Webber, L. 2017. The impact of positive behavioural support training on staff and the people they support. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 7, 13–23.

- van Oorsouw, W. M. W. J., Embregts, P. J. C. M., Bosman, A. M. T. and Jahoda, A. 2009. Training staff serving clients with intellectual disabilities: A meta-analysis of aspects determining effectiveness. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 503–511.

- Reed, F. D. D. and Henley, A. J. 2015. A survey of staff training and performance management practices: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 8, 16–26.

- Reichow, B., Doehring, P., Cicchetti, D. v. and Volkmar, F. R. 2011. Evidence-based practices and treatments for children with autism. New York: Springer, pp. 1–408.

- Reichow, B., Volkmar, F. R. and Cicchetti, D. V. 2008. Development of the evaluative method for evaluating and determining evidence-based practices in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1311–1319..

- Reid, D. H. and Parsons, M. B. 2004. Positive behavior support training curricilum: Supervisory trainer’s curriculum. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation.

- Reid, D. H., Rotholz, D. A., Parsons, M. B., Morris, L., Braswell, B. A., Green, C. W. and Schell, R. M. 2003. Training human service supervisors in aspects of PBS: Evaluation of a statewide, performance-based program. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 5, 35–46.

- Shapiro, M. and Kazemi, E. 2017. A review of training strategies to teach individuals implementation of behavioral interventions. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 37, 32–62.

- Schalock, R. L. and Keith, K. D. 1993. Quality of life questionnaire manual. Worthington: IDS Publishing Corporation.

- Smith, T., Parker, T., Taubman, M. and Lovaas, O. I. 1992. Transfer of staff training from workshops to group homes: A failure to generalize across settings. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 13, 57–71.

- Stokes, Stokes and Baer, D. M. 1977. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 349–367.

- Szczech, F. M. 2007. Effects of a multifaceted staff management program on the engagement of adults with developmental disabilities in community-based settings. Psychology - Dissertations. <https://www.surface.syr.edu/psy_etd/18> [Accessed February 15, 2022].

- Wardale, S., Davis, F., Carroll, M. and Vassos, M. V. 2014. Outcomes for staff participating in positive behavioural support training. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 4, 10–23.

- Willis, T. and LaVigna, G. W. 1990. Behavioral assessment report and intervention plan: evaluation instrument. Los Angeles: Institute for Applied Behavior Analysis.