Abstract

Families with a child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (PIMD) have to manage the child’s pervasive support needs. To ensure that families are able to manage these needs, they should be properly supported. However, knowledge about the specific support needs of these families is sparse and fragmented, nor is it known if and which needs are age-specific. To learn more about these families’ support needs, 20 parents of a child with PIMD aged 3–26 years were interviewed about their family’s support needs through interviews with open-ended questions. Interview transcripts were qualitatively analysed to identify support needs in five domains (child with PIMD, family, environment, services, and system). Various (age-specific) support needs were identified. The findings of this study can help health professionals and policy makers to improve the support of families with a child with PIMD by attuning the support to these families’ specific needs.

Managing the support needs of a person with Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities (PIMD) is complex and requires a significant amount of time and energy. Persons with PIMD have both a profound intellectual disability (Nakken and Vlaskamp Citation2007, Schalock et al. Citation2021, Van der Putten et al. Citation2017) and a severe or profound motor disability (Nakken and Vlaskamp Citation2007, Van der Putten et al. Citation2017). They often need specialized support related to their physical well-being, such as for constipation, epilepsy, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (Nakken and Vlaskamp Citation2007, Van Timmeren et al. Citation2017). The limitations in their conceptual, social, and practical skills are profound (Schalock et al. Citation2021), requiring dedicated support as well. Persons with PIMD also need the support of others for their personal development (Van der Putten et al. Citation2017). Moreover, the communication of persons with PIMD is atypical, consisting of sounds, gestures, and/or physiological signals, and may be idiosyncratic.These persons therefore require augmentative and alternative communication aids to communicate or the support of others who can interpret their signals (Van der Putten et al. Citation2017). Together, their support needs can be categorized as pervasive (Schalock et al. Citation2021).

Due to these pervasive support needs, the parents and other family members of a person with PIMD spent time and energy both on supporting the persons with PIMD as well as navigating complex support systems, especially when the child with PIMD lives at home and family members are the primary caregivers. Parents of children with PIMD indeed spend more time on care and supervision tasks compared to parents of typically developing children (Luijkx et al. Citation2017). And as social policies assign an increased responsibility to informal caregivers (Dermaut et al. Citation2020, Woodgate et al. Citation2015), their support tasks are likely to increase.However, families with a child with PIMD are on average satisfied with their well-being or family quality of life (FQOL), although they report limited satisfaction with some family life aspects, such as the support for stress relief (Lahaije et al. Citationin press).

Children with disabilities in general have more support needs than typically developing children, which have to be managed by other members of their family system. However, they are still considered to be best served within their own family, as their family knows their needs and well-being best, and are thus their best helpers (Wang and Brown Citation2009). To ensure that children with disabilities and their family members will thrive and enjoy a good well-being, a growing number of studies in the past three decades have focused on the FQOL, and the support needs of families with a child with disabilities (Luitwieler et al. Citation2021, Kyzar et al. Citation2012, Zuna et al. Citation2009). That is, by understanding how the well-being of these families is formed, what their support needs are, and consequently providing the necessary support, families can better support their child with disabilities, function better as a unit, and ultimately live a positive and meaningful life (Thompson et al. Citation2009, Wang and Brown Citation2009). A complete and proper understanding of the well-being of families can be acquired by studying a family not in the isolation of the family unit, but from a system perspective. Zuna et al. (Citation2009) describe how the well-being of families is the outcome of (and also input to) the interaction of various factors at different levels of a system: individual family members (e.g. gender, age), family (e.g. annual family income), support, services, and practices provided to the family as a whole as well as its members (e.g. respite care, medical care), and systems, policies, and programs (e.g. welfare programs). Support needs should similarly be studied from a system perspective, so as to acquire a complete inventory of needs, by which families can be accurately supported.

General support needs of families with a child with disabilities include respite care (Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009, Resch et al. Citation2010, Vilaseca et al. Citation2017), educational support for the child (Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009, Hart and Neil Citation2021), and transportation (Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009, Vilaseca et al. Citation2017). Financial support (e.g. through government programs) (Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009, Hart and Neil Citation2021, Vilaseca et al. Citation2017), and informational support (about the child’s medical condition or disability, but also about administrative matters) (Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009, Resch et al. Citation2010, Vilaseca et al. Citation2017, Wang and Michaels Citation2009) are needed by families as well. Parents also benefit from peer support (Shilling et al. Citation2013). Support needs also include good collaboration with professionals (Ryan and Quinlan Citation2018) and a family-centred practice by professionals (Hiebert-Murphy et al. Citation2011), i.e. a practice in which health professionals work collaboratively with families, empower them, and individualize their support to them. A family-centred practice is positively related to FQOL in families with a child with an intellectual disability (Davis and Gavidia-Payne Citation2009, Vanderkerken et al. Citation2019).

However, as persons with disabilities have unique support needs depending on their disability, their families are likely to have unique support needs as well (Hart and Neil Citation2021, Siklos and Kerns Citation2006, Wang and Michaels Citation2009). In order for family support to be effective, it has to be properly tailored to these specific needs. And as persons with PIMD should be uniquely supported (Van der Putten et al. Citation2017), we may assume that families of a child with PIMD should be uniquely supported as well. There is a growing insight into the environmental, familial, and personal factors affecting the well-being of these families (Lahaije et al. in press, Luitwieler et al. Citation2021), as well as their support needs. Parents with a child with complex care needs in general lack the necessary support and services to help them with their intense parenting tasks (Woodgate et al. Citation2015). A family-centred practice is important to parents of a child with PIMD (Jansen et al. Citation2013). Also, the needs of young adults with a profound intellectual disability and their parents during the transition to adulthood are found to be unmet (Gauthier-Boudreault et al. Citation2017). However, there is not yet a complete inventory of the varied needs of families with a child with PIMD from a system perspective.

Support for families with a child with PIMD can be further refined by being sensitive to age-specific support needs. These needs may be age-specific due to the child’s physiological changes or disease progression, while there may also be unique support needs related to specific transitional phases. For example, as children move from home to a residential facility, parents may have concerns regarding the successful transfer of parental knowledge (Kruithof et al. Citation2022). Findings regarding age-specific support needs of families with a child with PIMD are as of yet inconclusive (Luitwieler et al. Citation2021), and therefore require further study.

This study aims to investigate the support needs of families with a child with PIMD. To this end, the following research questions are formulated:

Research Question 1: What are the support needs of families with a child with PIMD from a system perspective?

Research Question 2: Are there support needs of families with a child with PIMD that are age-specific and if so, which?

Method

This study is part of a larger project (Sterker Samen [Stronger Together]) that aims to support families with a child with PIMD by strengthening their well-being.

Recruitment

Participants were approached after participating in a previous study (Lahaije et al. in press), and had been recruited for that study through convenience sampling, namely by social media, conferences, websites, newsletters and magazines, leaflets and letters sent out to service-providing facilities, and personal invitation. E-mails with information regarding this study along with an invitation to participate were sent out to 37 parents, one of whom declined to participate, 24 were willing to participate, and others did not respond. Inclusion criteria for this study were the same as for the previous study, namely families with a child with PIMD aged 0 to 30 years.For that study, participants completed questionnaires regarding the characteristics of their child with PIMD (e.g. indication of the intellectual disability [estimated IQ or developmental age], motor functioning skills, communicative abilities, and additional health problems) by which the researchers determined if the child had PIMD, as well as background characteristics of their family.

Participants

This study used a sample of 20 participants, four fathers aged 41 to 67 years (M = 53.00, SD = 10.95), and 16 mothers aged 32 to 57 years (M = 44.31, SD = 7.62), all from different families.All participants met the inclusion criteria of being a primary caregiver of a person with PIMD (profound intellectual disability, i.e. estimated IQ of <25 points/developmental age <24 months, and severe or profound motor disability, i.e. level IV or V on the Gross Motor Functioning Classification System [GMFCS; Palisano et al. Citation1997]) between the ages of 0 and 30. A cut-off age of 30 was used, as this was a follow-up to a previous study regarding the FQOL of families with a child with PIMD (Lahaije et al. in press), and the same inclusion criteria were therefore used.Children with PIMD were 9 men and 11 women, aged 3 to 26 years (M = 12.05, SD = 7.40). Furthermore, all included participants were from the Netherlands and were native Dutch speakers. See for additional self-reported characteristics of the participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants (family, parents, and child with PIMD).

Ethics

Ethical permission for this study was granted by the ethical committee of the department of Pedagogical and Educational Sciences (Ethische Commissie PEDON) after independent review. Participants were informed on the nature and goal of the study, data handling, and privacy. An online consent form was signed by all participants, who gave oral consent as well. Participants received no financial compensation, but were informed on the outcomes of the study.

Data collection

Interviews took place between January and May 2021, and were planned according to the participant’s wishes regarding time and day. Participants were, according to their wishes, interviewed either online or over the phone due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All interviews were carried out by the first author STAL (14 interviews) and PhD-student NDL (6 interviews), who frequently discussed (the themes emerging in) the interviews. Interviews lasted between 27 min and 2 h and 54 min (M = 1 h and 54 min).One interview was ended prematurely (and lasted 27 min) because the participant did not feel well, and was later finished by email.

Materials

The interview protocol was created by the authors and NDL. Open-ended questions were selected instead of closed questions or topic list, as open-ended questions allow participants to share in detail what is important to them, and may reveal information that was not anticipated (Stewart and Cash Citation2018). As such, it would ensure that participants were able to share all their support needs in detail. After a short introduction about the procedure and purpose of the interview, participants were asked to briefly introduce themselves through a description of their family. Next, for the main part of the interview, they were asked about their family’s support needs in the past, present, and future. For the past and present, they were asked what went well, and what did not go well or was missing in the support of their family (and its individual members). For the future, they were asked what they expected their family’s support needs would be. Additionally, they were asked what kind of support should be developed for families like theirs, or what would have been beneficial for them in the past and present. Interviewers were free to ask probing questions to have participants elaborate on their answers so as to better understand their support needs. Interviewers also familiarized themselves with factors known to affect the well-being of families with a child with PIMD (Lahaije et al. in press, Luitwieler et al. Citation2021) as preparation for the interviews. They were also free to ask participants about support needs regarding these factors, though this was sparsely done, as participants talked extensively about these subjects without probing. A small pilot study (N = 1) was conducted by STAL with a sibling of a person with an intellectual disability to evaluate the protocol.The outcomes of this pilot study were positive, and no changes to the protocol were therefore deemed necessary. See Appendix for the complete interview protocol.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed semi-verbatim (i.e. limited non-verbal nods were transcribed) by STAL, NDL, and master students. For a member check, all participants were invited to validate their complete interview transcript. Nine participants made minor changes and/or additions to the transcripts (e.g. minor corrections and clarifications,additional support needs). One participant did not respond to the initial invitation or to reminders to validate the transcript. Other participants validated the transcripts without changes and/or additions.

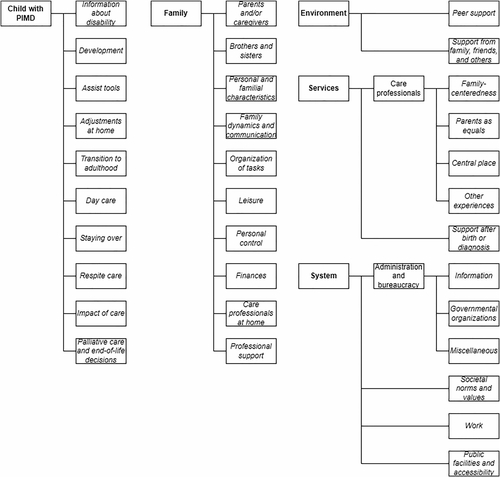

The full dataset was coded using ATLAS.ti. All text fragments regarding the support needs of these families (what support they needed, and what support they received from others and themselves) were coded. Three interviews were coded openly for an initial set of codes. Emerging codes were combined and grouped within larger categories and domains in a framework based on the FQOL model of Zuna et al. (Citation2009), with a distinction made between the child with PIMD and the rest of the family unit, and with the domain of environment added. This was done as both the interviews and previous studies suggested that social support was important for families, which could not be fit into any of the identified domains. The five domains used in this study were therefore: child with PIMD (support, development, assistive technology), family (family unit, parents, siblings), environment (family, friends, peers), services (care professionals, physicians), and system (society, government, health insurance companies, personalized care budget). While there is an interaction between domains on certain subjects (e.g. assistive technology benefits the child with PIMD, but is often funded through government programs), we opted to place all needs regarding a subject in one domain, namely the one it was most relevant to.

Discussions between the authors and coder NDL led to further refinement of the coding framework, in that some codes were added, and several codes got extended definitions. For an initial intercoder agreement (ICA) STAL and AS (a master student) coded 200 random fragments, and NDL and AS coded 200 random fragments as well. These fragments were from 16 interviews. The ICA was low (36.4% and 40.4% respectively), and therefore the coding framework was discussed and refined. Some codes were found to be divided into subcodes that were too narrow, and were therefore combined into broader codes, while other codes were found to be overlapping, and were therefore more clearly demarcated. Also, the code ‘Other experiences’ was added to the domain of services. Both STAL and AS, and NDL and AS, then each coded random 200 fragments (from 19 interviews) again for the ICA. ICA was higher, but not yet sufficient (36.0% and 76.4% respectively) to continue. The coding framework was again discussed and further refined, in that codes were more clearly demarcated. All coders believed it would be beneficial to discuss the coding in a joint session to clarify any misconceptions and align their interpretations of codes, and therefore opted for this joint session as an alternative for a typical ICA. STAL, NDL, and AS thus independently coded 30 random fragments in a joint session, and reached a high ICA (78.3%). They discussed the fragments with differing coding for clarification and to align their interpretation of the codes, after which the coding framework was considered to be complete (see for a visualization of the framework of domains and codes). All fragments (1896) were then divided between and coded by STAL, NDL, and AS. Final fragments on which coders had doubt (108) were discussed and codes were determined together in two final joint sessions between STAL, NDL, and AS. For the first research question, codes were qualitatively analysed by the first author to uncover major support needs in each of the five domains. For the second research question, each interview was analysed separately by the first author to uncover major support needs mentioned by parents only in relation to a specific age (period).These outcomes were then qualitatively analysed to determine major age-specific support needs of families with a child with PIMD.

Results

Support needs

All presented quotes are from participants.

Child with PIMD

Many parents expressed they needed more information regarding their child’s condition, what it entails, and how it would develop over time. Parents expressed this most when their child was still young and when it was still unclear what condition their child had. Parents expressed a need for clarity, and disliked itwhen they were given false hope. However, their concerns regarding their child’s condition were sometimes dismissed, and parents had to actively ask for a diagnosis. Several parents therefore expressed a need to have their concerns be heard, and have care professionals take a pro-active role in the diagnosis of their child.

Several parents mentioned they needed informational support regarding the availability, characteristics, and possibilities of assistive technology (e.g. hoist, specialized wheelchair), and how they could be funded. Some parents wished to have a greater say in their choice of assistive technology, as they were limited in their choices by governmental policies.They were not allowed to select an aid that was better suited to their or their child’s needs, even if they funded part of the costs themselves. Others mentioned that they would not receive funding for multiple copies of the same technology, in case they wanted it to be available at home and elsewhere. Some parents expressed that they needed the aesthetics of assistive technology to be improved so it would fit better in their home interior, as it was currently found to be too ‘hospital-like’.

Most parents’ children went to a day care centre. Parents expressed that they needed day care centre professionals to be invested in their child and family unit, and needed close and prompt personal contact with professionals. Parents also needed the professionals at the day care centre to spend time and effort on the development of their child.

Mother (38): Yes, I think, that they see that development is still possible, and that they are also committed to development, and not just to caring. So stimulating as well, and maybe also move beyond limits, like, well, we’re going to try this, and if it doesn’t work, we’ll take a step back. That’s what I think. I find that really important.

Family

All parents spoke about how managing the intensive support for their child with PIMD affected their family dynamics, and expressed the need for resources to relieve themselves from their support duties, so that they could maintain a balanced and healthy family life. This included parents having time for each other, and for their other children if they had any.

Father (55): You deal with so many things that at some point I said to my partner, my girlfriend, you know, the moment our child is in bed, I’ll give it fifteen minutes, and then I’m out. Then it’s done. And very consciously we made that choice, that from Friday evening six o’clock till Monday morning, it’s just our family, and we only have time for each other, and for my mom or whatever. We’re going to cook something nice, anything, just nothing else.

These resources included a day care centre for their child, having their child stay over, respite care, and/or in home support. However, some barriers hindered parents from securing the resources they needed, such as a lack of proper facilities for their child to stay over, limited time and budget to pay for respite care, a limited number of professionals who are specialized in PIMD, or a possible disruption of their home life. Some parents expressed that they were not (fully) equipped to create or restore balance within their family system themselves, and therefore required professional support (e.g. family coach or relationship therapist) to guide and support them.

Nearly all parents talked about how they needed leisure time for themselves and for other family members, and for their family as a unit, but struggled with finding the time, resources, and facilities for leisure. Some parents made the decision to go on a holiday without their child with PIMD, whereas others found it important to go on a holiday with all family members. However, these parents sometimes struggled with finding the holiday resorts that would accommodate families with a child with PIMD, as most resorts did not have the assistive technology parents had at home. Similarly, some parents found it difficult to go out with their child, as there are limited public facilities available for people with PIMD.

Most parents were fulltime or part-time employed, and several parents expressed they needed to work not just for financial, but for personal reasons as well, as their employment gave them a purpose, and helped them to take their mind of the support duties for their child. However, some parents experienced difficulties combining support duties with paid work, and needed their employers to be more understanding and facilitating.

Mother (57): I’ve always kept working, and I can recommend that to everyone. That is important. That you’re just… Work is almost relaxing then. There, for a moment, you’re not the mother of. (…) You’re also appreciated for what you do there. And besides having a child with intense care and support needs, I found it important to be in a different environment.

Environment

Nearly all parents spoke about the various kinds of peer support they needed (and had found). In all cases, parents sought out other parents for informational support, such as exchanging information regarding administrative and legal matters, information regarding assistive technology, and to learn about new technologies and toys. Some parents also went to peers for emotional support and affirmation, in that they felt that their experiences unique to having a child with (multiple) disabilities were only shared and understood by other parents of a child with PIMD.

Mother (48): Yes, and maybe especially that they can fill in the blanks. And that you don’t argue with each other, or calm each other down. And that you can also say, it all just sucks. Other people would say, oh, but other children are also sick sometimes, or they also do this or that. But I’m like, no, it’s different for us. A cold is not just a cold. We have to be very careful with a cold. And that you don’t have to explain that, that the other person just understands where you’re at. And that sometimes… It’s not all just misery. You can also laugh about what’s going on. Because that’s also what happens.

Parents found peers through social media, but also met other parents at the day care centre of their child. Several parents noted that it was important to have chemistry with other parents, and that apart from a child with PIMD, they may have little to nothing in common with other parents.

Most parents needed and received support from their social environment, such as family, friends, acquaintances, neighbours, or church members. Support was both practical (e.g. helping with household tasks) and emotional (e.g. asking how someone is doing).

Mother (48): You know, just ask how it’s going. Send a text when we’ve had a hospital appointment, I don’t need that for all appointments, but for example for his hip, which I was nervous about, that someone wonders about how that went. Or ask if I would appreciate it if they would come with me when it’s a more complicated appointment, something like that. Or invite us to go for a walk. That, or invite us to come over. Come by, relax, just that.

Several parents mentioned that a barrier in receiving support was that family and friends did not understand or appreciate what they were going through, and/or showed little to no interest. They subsequently lost touch with these people. At the same time, several parents also mentioned that reaching out and sharing personal experiences with other people facilitated the support they received.

Services

Nearly all parents mentioned that they needed a family-centred practice from care professionals. Participants talked about how they needed professionals to be aware of and sensitive to the fact that the child with PIMD was part of a larger family unit that the child affected, but was also affected by, and that the family (members) of the child with PIMD had needs as well. Parents spoke about how they needed professionals to be pro-active, in that they would anticipate needs, inform parents (ahead of time) on support-related matters (e.g. new assistive technology), help them get in touch with other care professionals, and, if possible, relieve them from support duties. Next to that, most parents needed professionals to inform them how they were handling the support for their child, and some parents also needed (information on) family support and interventions from professionals.

Mother (52): What I really appreciate about that is that there are people there who can also mentally take the care over from me. That I get the feeling that he is seen there, that they really think along, sometimes anticipate, that they also notice it when he has pressure sores or that his wheelchair isn’t set up correctly. That they really think along and try to support us and relieve our family.

Most parents also mentioned that in their relationship with professionals, they found it important that they could collaborate with professionals as equals, in that they did not want be patronized, and instead wanted to be fully informed, valued and respected. Participants also expressed that professionals should value the practical and medical knowledge that parents have regarding their child, such as how their child communicates and behaves, the unique combination of health problems, and information about their child’s syndrome, in case it is rare. Moreover, parents stated that they appreciate it when professionals are willing to admit they lack knowledge or experience, or were at fault, but were also willing to listen and learn.

Mother (57): Well, that you are appreciated as a mother, and that people listen to you. That doesn’t mean you’re always right, or that you know best. That’s not the case. But we should be able to talk about it, have open communication and… Yes, that you’re taken into account as parents. It’s not as if the people who studied for it have a monopoly on wisdom. Because it seems that way sometimes. Even though they have no experience.

Several parents mentioned that they needed one central place where they could turn to for informational and practical support regarding their child’s condition, but also for administrative matters. This central place could come in the form of a website, a clinic, or a person. Several parents also expressed their need for one professional to have a complete overview of the complete support network of their child, who can provide the proper support, and help parents find the right professionals for their child. This person should preferably be with a family for an extended period of time. Several parents also mentioned the ‘co-pilot’ pilot study in the Netherlands, in which Dutch families with a child with PIMD were assigned a family assistant who provided support for various (administrative) matters. They expressed that they either had positive experiences with this service, or wished they had had this service when their child was young.

The need to think about and discuss palliative care, quality of life and end-of-life decisions with professionals was mentioned by several parents. They found it important that their wishes and opinions were heard and respected, and agreements were made ahead of time.

Mother (57): I find it important that these things can be discussed and are taken care of. And that agreements are made. That way I have made arrangements for when my child will pass. Just so you don’t have to think about it at the last moment.

System

Nearly all parents expressed how they needed financial and material support from government programs and/or health insurance companies, but had difficulties receiving this support, even when they were eligible for it. Several parents mentioned that governmental support systems are not adapted to, and do not reflect the reality and complexities of supporting a child with PIMD. Instead, they need these systems to be better adapted to their situation, and to be more flexible. Parents also found it unfair that the provided financial and material support differed per municipality, meaning parents did not always receive the support they (believed they) were eligible for. Also, several parents mentioned that governmental employees were not sensitive to their situation, and were therefore experienced as rude or insensitive.

Mother (48): That made me really sad. That someone questioned why I applied for support again. It was almost as if I was stealing. As if I wanted to steal from the government. I just need it, we just need it. I’d rather not have that ugly thing in our home. We just need it.

Parents also expressed that they need governmental organizations to be more efficient and less bureaucratic and fragmented. That is, parents have to apply for a variety of support for their child with PIMD, but are required to explain their situation with each new application. Additionally, since their child will most likely have PIMD for the rest of their lives, parents expressed they find it unnecessary to apply for the same support every year.

Father (55): Yes, it would save a lot of time on our side if we don’t have to tell our story every time. And I think it would also save a lot of time on their side, because four out of five organizations are from our municipal government. Except they each have a different counter. And each counter needs to make its own file. Yes, that takes time. And I think that time is better spent. At least on our side it is better spent.

Several parents mentionedthat they need governmental organizations to be more pro-active, as they found it hard and did not have time to understand and navigate through the various government programs they could apply to.

Mother (52): So I called the Care Administration Office. Well, the woman on the phone explained some things to me and then sent me a form. And then she called two weeks later, saying, I talked to you, I sent you that form, and are you able to complete it? I said, well, I have never experienced that an organization that I asked for help reaches out to me to ask if I can complete by myself or if I need help. (…) And that is nice, and generous, and pro-active. And not like, oh, I’ve sent an e-mail, and if they don’t respond, who cares, and then nothing.

Nearly all parents also needed informational support about what governmental programs they could apply for, and where and how they had to apply. Additionally, parents needed more support regarding legal matters, such as conservatorship, that are different for children with disabilities compared to typically developing children.

Mother (32): Well, I always say, taking care of my daughter is not hard. But all the administration, that’s what makes it hard. Getting a personal care budget, problems with compulsory education, then you have to go after that person, then this again… I spend more time on that, than on the care for my daughter, that’s just a waste of time.

Age-specific support needs

There are a number of age-specific support needs of families with a child with PIMD. First, while parents need informational support regarding their child’s condition at all ages, this was most expressed at an early age. Furthermore, nearly all parents expressed that (looking back) it was important for them that when they first receive the diagnosis of their child’s condition, a physician would take time to explain and discuss the diagnosis, what to expect (e.g. is the condition progressive and in what form, what is the life expectancy of their child), and talk about what the life of their child and their family would look like. Moreover, most parents mentioned they needed support at an early age for setting up the support system for their child, for administrative and legal matters, and for finding the right assistive technology. They found it difficult to combine these tasks with the care for a young child with disabilities, and needed support to relieve them from these tasks and/or be properly set up.

Mother (57): I was really searching during that time. Although I thought to myself, is there no one who knows this? You just don’t know the way. You end up in a whole different world. I never had anything with handicapped people. Never… Well, not in my family or anything. No acquaintances, family or friends either… No, that time, the first four years, I found it very difficult to find my way. Though that is so important, I think, that you receive intensive support then.

New and specific support needs appear during the child transition to adulthood. Several parents mentioned they needed support to find the right residential facility for their child. Parents lacked information on living facilities for people with PIMD (e.g. which facilities there were, where they were, and what their characteristics were), but were also concerned that the provided care, support, and services might not live up to their standards. Some parents therefore opted to continue to care for their child themselves, while few were interested in, or had even taken the initiative to start their own living facility. Next to that, many parents needed informational support regarding administrative and legal matters unique for a child with an intellectual disability transitioning to adulthood, but did not know where to find it, and hoped the information would be offered to them. Finally, some parents expressed concern that the elaborate (medical) support system they had carefully set up for their child would have to be rebuilt or rearranged, as their child moved from child to adult care.

Mother (46): Yes, like right now, for example when he turns 18, I know a lot of things have to be taken care of, but what. There is no one who already tells me , like, think about that, like, I hear all around me that people say, you have to start early. It’s not done easily, but there is no one who now tells me what needs to happen. I don’t know, I guess we have to find out ourselves.

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to understand the support needs of families with a child with PIMD, and if they have age-specific needs. We found various major support needs. For their child with PIMD, parents expressed needs for informational support regarding their child’s condition, informational and practical support regarding assistive technology, and day care centres that provide good (developmental) support for their child. On the domain of family, parents mentioned the need for resources to alleviate their care burden and maintain a healthy family well-being, resources for leisure time, and needed paid work that could be combined with the care duties for their child. As for environment, parents needed practical and emotional support from peers, as well as from their social environment. For services, parents mentioned they needed care professionals to have a family-centred approach, to collaborate on equal footing with care professionals, a central place for all matters related to their child with PIMD, and needed to discuss and agree on palliative care and quality of life. Within the domain of system, parents indicated they needed material and financial support, needed government programs to be better adapted to their situation and to be more pro-active, and also needed informational support. For age-specific needs, we found that at an early age, parents needed informational support regarding their child’s diagnosis, as well as informational and practical support to be properly set up. When the child with PIMD transitions to adulthood, parents expressed the need for support to find the right residential facility for their child, as well as informational support regarding administrative and legal matters.

Comparing the results of this study with previous studies on the needs of families with a child with a disability, we find that families with a child with PIMD share needs regarding respite care, financial support, informational support, good collaboration with professionals, and family-centred practice by professionals (e.g. Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009, Hiebert-Murphy et al. Citation2011, Resch et al. Citation2010, Ryan and Quinlan Citation2018, Vilaseca et al. Citation2017). This study also reaffirms that a family-centred approach is important for families with a child with PIMD (Jansen et al. Citation2013). Parents in this study also use various resources for informational support, similar to other parents with a child with a disability (Alsem et al. Citation2017).Some parents in this study were able to make work arrangements, whereas several parents did not but had a need to, similar to other informal caregivers (Oldenkamp et al. Citation2018). We found that parents of a child with PIMD also benefit from peer support, though sharing a social identity was not expressed as a benefit (Shilling et al. Citation2013). In line with the findings of Woodgate et al. (Citation2015), we found that parents are in need of respite care and social support.For support after birth or diagnosis, we found some similarities between parents of a child with PIMD and parents of a child with Down syndrome (Valentine et al. Citation2022), namely taking time to discuss the condition of the child, and being provided with sufficient, up-to-date information. For the transition to adulthood, we also found that parents have needs for informational and material support (Gauthier-Boudreault et al. Citation2017).

Contrarily, transportation and educational support (Burton-Smith et al. Citation2009) were not found as major support needs for families with a child with PIMD. Families in this study may be sufficiently supported in their transportation needs due to the study taking place in the Netherlands, a (conservative) welfare state (Nugroho Citation2018) with social support for families that is also densely populated. Also, while most parents expressed a need for developmental support for their child, no parents mentioned support to have their child be part of a traditional educational setting. This is at odds with the growth of inclusive education, initiated by parents of children with PIMD themselves (De Boer and Munde Citation2015). Parents in this study may not be aware of (schools offering) inclusive education, or perhaps believe that their child can only be properly supported at day care centres specialized in PIMD, in particular because of additional health problems that persons with PIMD often have (Nakken and Vlaskamp Citation2007, Van Timmeren et al. Citation2017).

This study not only has provided an extensive inventory of the needs of families with a child with PIMD from a system perspective, but has also provided insight in which support needs are particular or more pronounced for these families. A particular support need for these families is support regarding assistive technology. This can be understood in that persons with PIMD have a severe to profound motor disability, and therefore require specialized technologyto move, be moved, and physically develop.Moreover, due to their atypical communication, persons with PIMD may also use devices for augmentative and alternate communication. Assistive technologyistherefore a fundamental and major part of the care for persons with PIMD, and parents (as informal carers) thus have a need for it. Despite the integral role of assistive technology, it appears that informational and administrative support regarding assistive technology is insufficient for parents, however. Additionally, due to the multiple severe and profound disabilities of their child, parents interact with many care professionals, and face a high administrative load, as they (have to) apply for a significant amount of financial and material support. Many parents therefore expressed a need to be supported in these matters, and their need can be expected to be higher than for parents with children with other disabilities. However, while informal caregivers are expected to take on more responsibilities (Dermaut et al. Citation2020) not all parents are able to commit to that, stressing the importance of supporting parents in this need. Furthermore, while not all parents mentioned this subject, needs related to palliative care and end-of-life decisions are expected to be more prevalent for families with a child with PIMD due to the child’s condition. Similar to Zaal-Schuller et al. (Citation2016), we found that parents found it important that conversations and agreements regarding end-of-life decisions were made ahead of time, and that parents’ views were valued and respected. While the need for information regarding the condition of their child is not typical for parents with a child with PIMD, it may be significantly more difficult to fulfil this need for these parents. That is, a proper diagnosis is sometimes not possible, or the child is diagnosed with a very rare syndrome on which limited information is available.Finally, several parents expressed they did not look too far into the futureas their child had a limited life expectancy, and/or had severe health problems. Some parents expressed that this hindered them from making long-term plans, and this uncertainty may be a unique challenge for families with a child with PIMD.

When compared to the study of Lahaije et al. (in press), which explored the well-being or FQOL of families with a child with PIMD and found that families are satisfied with their FQOL, there are congruent and incongruent findings with this study. Families in that study had limited satisfaction with (support for) stress relief, which is also expressed in this study in that parents needed more resources to maintain a healthy family well-being. However, while families in that study were least satisfied with the support for their child with PIMD to make friends, this was not mentioned as a support need by the participants in this study, possibly because parents may believe that their child with PIMD is not able to, or does not benefit from making friends. Moreover, while considered to be a part of FQOL, no support needs regarding dental care and transportation facilities were found in this study, possibly due to these needs being already met. Future studies may further explore these discrepancies to understand what they imply for the support of these families, and the (theorization of) FQOL.

Limitations

The outcomes of this study should be understood within the following limitations. As is common in this kind of studies, more mothers than fathers participated (Davys et al. Citation2017). While there are differences in reported needs between mothers and fathers (Wang and Michaels Citation2009), the number of fathers in this study is limited (4 out of 20), and it is therefore not possible to compare their answers with those of participating mothers to see if there are any significant differences in this study. Furthermore, only the parent who was indicated as the primary caregiver was interviewed, and this parent may have different needs or perspectives than the other parent (if any). Additionally, no brothers or sisters were interviewed, even though siblings have a different perspective on family life than parents (Correia and Seabra-Santos Citation2021) and are more satisfied with certain family life aspects than parents (Lahaije et al. in press). There were a limited number of families with low annual incomes, and no families with a migratory background included, though these families may have different support needs. No parents with a child living ina residential facility were interviewed either, though these parents may have, and have had different support needs. Moreover, this study took place in the Netherlands, a conservative welfare state with affordable health insurance and governmental support for families (Nugroho Citation2018).This may have affected the outcomes of this study, in that some support needs of parents in the Netherlands are generally met compared to parents in countries with limited governmental support.

Implications for practice

This study has provided valuable insights into the support needs of families with a child with PIMD, which can be used to improve the support and services provided to these families. Of note is that several parents mentioned the ‘co-pilot’ pilot study (Ten Brug et al. Citation2020), in which Dutch families with a child with PIMD were assigned a family assistant who provided support for various matters (e.g. administrative tasks, solving organizational conflicts), so that families could spend more time on what was important to them (e.g. friends, hobbies) and improve their well-being. This kind of support was positively met by families, and parents in this study mentioned either having positive experiences with a co-pilot, or expressed the desire to have had the support of a co-pilot.A co-pilotmay therefore be considered as a service for these families, and could also be adapted in other cultures and countries.

In line with Jansen et al. (Citation2013), most parents in this study expressed that a family-centred approach by care professionals was important to them. Training of health professionals as well as service policies should therefore ensure that professionals use this approach in support of these families. As mentioned by Oldenkamp et al. (Citation2018), informal carers have certain rights (in the Netherlands) regarding work arrangements to facilitate them in their informal care, but are not fully informed on these rights. Since several parents in this study mentioned that they experienced difficulties combining paid work with informal care, informational (and/or legal) support regarding work arrangements may have to be intensified. Furthermore, families may also be indirectly supported by changes in governmental organizations, by making these organizations more accessible, and less bureaucratic. This is especially of note since several parents mentioned that they did not receive the financial and material support (they believed) they were eligible to. Moreover, this study shows that support for families with a child with PIMD should be approached from a system perspective, in that their support needs extend beyond their family unit. That is, support and interventions should not only be directed at the family unit and its members, but should takehigher domains (environment, services, and system) into account as well.

Future studies

This study found particular and more pronounced support needs for families with a child with PIMD, confirming that PIMD specifically, and other disabilities in general, should be studied separately, in that support needs cannot be generalized over all disabilities. The results of this study also suggest new research possibilities and opportunities. For future studies, we recommend to include more family members than the primary caregiver, as there may be differences in support needs and perspectives on family life depending on family role, which has not been uncovered by this study. It may also be insightful to include multiple members from the same family, or to interview multiple members from the same family at once. Furthermore, we recommend to include more families with a migratory background, with a low annual income, and families whose child with PIMD lives at a residential facility, as these families were not included and/or underrepresented in this study, but may have different or unique support needs. Also, longitudinal studies may provide additional insight into age-specific needs, and/or changes in support needs over time. Furthermore, as many parents expressed the need for informational support regarding their child’s condition and if and how it changes over time, future research may focus on gaining more insightin PIMD and any rare underlying syndromes. Moreover, future studies may also focus on how to best supportparents after birth or diagnosis, and during the transition to adulthood.That is, more insight is needed in how to best communicate with and support parents during these critical phases, similar to what has been found for, for example, parents with a child with Down syndrome (Valentine et al. Citation2022). Finally, intervention studies may provide further insight into how these families are best supported, and we recommend developing interventions in cooperation with families, so as to ensure the intervention is appropriately attuned to these families’ needs.

Conclusion

This study has provided more insight into the support needs of families with a child with PIMD by providing an extensive inventory from a system perspective. Several support needs within five domains (child with PIMD, family, environment, services, system) were identified. Age-specific support needs were identified as well. The results of this study may contribute to improve the support for these families, by better attuning it to the specific needs that were identified in this study. Through proper support, we can ensure that families with a child with PIMD enjoy a good well-being, and will continue to thrive.

Ethical statement

Ethical permission for this study was granted by the ethical committee of the department of Pedagogical and Educational Sciences (Ethische Commissie PEDON) after independent review.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Nicole van den Dries-Luitwieler for her help in interviewing and coding, Anne Schepers for her help in coding, and Amy Holtvlüwer, Sharon Hulzebos, and Minke de Vries for their help in transcribing the interviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alsem, M. W., Ausems, F., Verhoef, M., Jongmans, M. J., Meily-Visser, J. M. A. and Ketelaar, M. 2017. Information seeking by parents of children with physical disabilities: An exploratory qualitative study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 60, 125–134.

- Burton-Smith, R., McVilly, K. R., Yazbeck, M., Parmenter, T. R. and Tsutsui, T. 2009. Service and support needs of Australian carers supporting a family member with disability at home. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34, 239–247.

- Correia, R. A. and Seabra-Santos, M. J. 2021. “I would like to have a normal brother but I’m happy with the brother that I have”: A pilot study about intellectual disabilities and family quality of life from the perspective of siblings. Journal of Family Issues, 43, 3148–3167.

- Davis, K. and Gavidia-Payne, S. 2009. The impact of child, family, and professional support characteristics on the quality of life in families of young children with disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34, 153–162.

- Davys, D., Mitchell, D. and Martin, R. 2017. Fathers of people with intellectual disability: A review of the literature. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities : JOID, 21, 175–196.

- De Boer, A. A. and Munde, V. S. 2015. Parental attitudes toward the inclusion of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities in general primary education in the Netherlands. The Journal of Special Education, 49, 179–187.

- Dermaut, V., Schiettecat, T., Vandevelde, S. and Roets, G. 2020. Citizenship, disability rights and the changing relationship between formal and informal caregivers: It takes three to tango. Disability & Society, 35, 280–302.

- Gauthier-Boudreault, C., Gallagher, F. and Couture, M. 2017. Specific needs of families of young adults with profound intellectual disability during and after transition to adulthood: What are we missing? Research in Developmental Disabilities, 66, 16–26.

- Hart, K. M. and Neil, N. 2021. Down syndrome caregivers’ support needs: A mixed-method participatory approach. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 65, 60–76.

- Hiebert-Murphy, D., Trute, B. and Wright, A. 2011. Parents’ definition of effective child disability support services: Implications for implementing family-centered practice. Journal of Family Social Work, 14, 144–158.

- Jansen, S. L. G., Van der Putten, A. A. J. and Vlaskamp, C. 2013. What parents find important in the support of a child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 39, 432–441.

- Kruithof, K., Olsman, E., Nieuwenhuijse, A. and Willems, D. 2022. “I hope I’ll outlive him”: A qualitative study of parents’ concerns about being outlived by their child with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 47, 107–117.

- Kyzar, K. B., Turnbull, A. P., Summers, J. A. and Gómez, V. A. 2012. The relationship of family support to family outcomes: A synthesis of key findings from research on severe disability. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37, 31–44.

- Lahaije, S. T. A., Luijkx, J., Waninge, A. and Van der Putten, A. A. J. in press. Well-being of Families With a Child With Profound Intellectual and Multiple Disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities.

- Luijkx, J., Van der Putten, A. A. J. and Vlaskamp, C. 2017. Time use of parents raising children with severe or profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Child: Care, Health and Development, 43, 518–526.

- Luitwieler, N., Luijkx, J., Salavati, M., Van der Schans, C. P., Van der Putten, A. A. J. and Waninge, A. 2021. Variables related to the quality of life of families that have a child with severe to profound intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. Heliyon, 7, e07372.

- Nakken, H. and Vlaskamp, C. 2007. A need for a taxonomy for profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 4, 83–87.

- Nugroho, W. S. 2018. Role of state and welfare state: From commons, Keynes to Esping-andersen. JurnalEkonomi&Studi Pembangunan, 19, 101–115.

- Oldenkamp, M., Bültmann, U., Wittek, R. P., Stolk, R. P., Hagedoorn, M. and Smidt, N. 2018. Combining informal care and paid work: The use of work arrangements by working adult‐child caregivers in the Netherlands. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26, e122–e131.

- Palisano, R., Rosenbaum, P., Walter, S., Russell, D., Wood, E. and Galuppi, B. 1997. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental medicine and Child Neurology, 39, 214–223.

- Resch, J. A., Mireles, G., Benz, M. R., Grenwelge, C., Peterson, R. and Zhang, D. 2010. Giving parents a voice: A qualitative study of the challenges experienced by parents of children with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55, 139–150.

- Ryan, C. and Quinlan, E. 2018. Whoever shouts the loudest: Listening to parents of children with disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31, 203–214.

- Schalock, R. L., Luckasson, R. and Tassé, M. J. 2021. Intellectual disability: Definition, diagnosis, classification, and systems of supports. 12th ed. Washington, DC: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

- Shilling, V., Morris, C., Thompson-Coon, J., Ukoumunne, O., Rogers, M. and Logan, S. 2013. Peer support for parents of children with chronic disabling conditions: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Developmental medicine and Child Neurology, 55, 602–609.

- Siklos, S. and Kerns, K. A. 2006. Assessing need for social support in parents of children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 367, 921–933.

- Stewart, C. and Cash, W. 2018. Interviewing: Principles and Practices. 15th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Ten Brug, A., Beernink, J. and Luijkx, J. 2020. Een Copiloot geeft een ZEVMB-gezin lucht en ruimte. Een onderzoek naar gezinnen rondom een kind met ZEVMB, die ondersteund worden door een Copiloot [A Co-pilot let’s a PIMD-family breathe.A study about families with a child with PIMD who are supported by a Co-pilot]. Partoer. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2020/09/30/een-copiloot-geeft-een-zevmb-gezin-lucht-en-ruimte

- Thompson, J. R., Bradley, V. J., Buntinx, W. H., Schalock, R. L., Shogren, K. A., Snell, M. E., Wehmeyer, M. L., Borthwick-Duffy, S., Coulter, D. L., Craig, E. M., Gomez, S. C., Lachapelle, Y., Luckasson, R. A., Reeve, A., Spreat, S., Tassé, M. J., Verdugo, M. A. and Yeager, M. H. 2009. Conceptualizing supports and the support needs of people with intellectual disability. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 47, 135–146.

- Valentine, K., Reynolds, S., Donegan, D., Ghazali, F. W., Khan, D., Lim, E. Q., Mair Nasser, M. N. S., Mc Grane, F., Corcoran, B., Purcell, C., Isweisi, E., Ó Catháin, N., Roche, E. F., Meehan, J., Allen, J. and Molloy, E. 2022. Communicating a neonatal diagnosis of Down syndrome to parents. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 107, 409–411.

- Van der Putten, A. A. J., Vlaskamp, C., Luijkx, J. and Poppes, P. 2017. Kinderen en volwassenen met zeer ernstige verstandelijke en meervoudige beperkingen: Tijd voor een nieuw perspectief. [Children and adults with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities: Time for a new perspective] [Position paper]. http://www.qolcentre.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/mensen-meerv-bep-pos-pap-van-derputten-2017.pdf

- van Timmeren, E. A., van der Schans, C. P., van der Putten, A. A. J., Krijnen, W. P., Steenbergen, H. A., van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H. M. J. and Waninge, A. 2017. Physical health issues in adults with severe or profound intellectual and motor disabilities: A systematic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61, 30–49.

- Vanderkerken, L., Heyvaert, M., Onghena, P. and Maes, B. 2019. The relation between family quality of life and the family-centered approach in families with children with an intellectual disability. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 16, 296–311.

- Vilaseca, R., Gràcia, M., Beltran, F. S., Dalmau, M., Alomar, E., Adam-Alcocer, A. L. and Simó-Pinatella, D. 2017. Needs and supports of people with intellectual disability and their families in Catalonia. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities : JARID, 30, 33–46.

- Wang, M. and Brown, R. 2009. Family quality of life: A framework for policy and social service provisions to support families of children with disabilities. Journal of Family Social Work, 12, 144–167.

- Wang, P. and Michaels, C. A. 2009. Chinese families of children with severe disabilities: Family needs and available support. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 34, 21–32.

- Woodgate, R. L., Edwards, M., Ripat, J. D., Borton, B. and Rempel, G. 2015. Intense parenting: A qualitative study detailing the experiences of parenting children with complex care needs. BMC Pediatrics, 15, 1–15.

- Zaal-Schuller, I. H., Willems, D. L., Ewals, F. V., Van Goudoever, J. B. and De Vos, M. A. 2016. How parents and physicians experience end-of-life decision-making for children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 59, 283–293.

- Zuna, N. I., Turnbull, A. and Summers, J. A. 2009. Family quality of life: Moving from measurement to application. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6, 25–31.

Appendix

Interview protocol

BEFORE THE INTERVIEW

<approach participant by email>

<make an appointment>

<confirm appointment and send information brochure>

<in case of online interview: have the participant sign online consent form>

<in case of live interview: print consent form>

DURING THE INTERVIEW

<prepare recording equipment>

<ensure quiet environment, e.g. phone on quiet mode>

Good morning/afternoon, before we start the interview I would like to have your permission to record it. During the interview I will also make notes. You may have read all the information in the information brochure, but I would like to reaffirm that everything you say will be completely anonymous. Do you consent to this interview being recorded?

<in case of live interview: have the participant sign the consent form>

<start recording>

<have the participant give oral consent>

First of all, I would like to thank you kindly for your time. My name is (…) and I will be interviewing you today about the support of families like yours. This interview is part of the project Sterker Samen (Stronger Together). The goal of this project is to increase the well-being of families with a child with PIMD. This will be done by first finding out how the family quality of life of these families is formed (by questionnaires), and what their support needs are (by interviews such as this one). We will then use this knowledge to create products together with parents, other relatives and care professionals that will help to increase the family quality of life. By what you tell us today, you will help us to create products that are specifically attuned to the wishes and needs of families like yours.

I am going to ask you questions about the support of your family in the past, present, and future. What matters is what is helping, or has helped you, but also what can be improved. You can also indicate that you do not need support for specific aspects, or instead that you have missed it. For every question you may think about your family as a whole, but also about individual members. For support you may think about formal support (physicians, nurses), but also informal support (family, friends), but also about what you have done for yourselves. There are no right or wrong questions. My goal is to limit the interview to one to one and a half hours, but we can always pause if you want to. Do you have any further questions?

-introduction

1. As an introduction: could you paint me a picture of your family? How should other people know you?

-past

2. Looking back, what has helped your family in terms of support in the past? You may think about what others did for you, but also what you did for yourselves.

3. Looking back, what could have been improved, or what did you miss in the support of your family?

-present

4. What is presently helpful in the support of your family? What is going well?

5. What do you presently need, or could be improved in the support of your family?

-future

6. What kind of support do you expect to need in the future?

7. Do you have any ideas for a product that we could develop? What is something you want or would have wanted?

8. Is there anything else regarding support needs you would like to share (for example something you can recommend)?

<end recording>

Thank you kindly again for your time. What did you think about the interview? Do you have any suggestions to improve the interview?

-----

The following topics are (possible) factors that play a role in family quality of life, and in the support needs of families. One or more of these topics may be asked to comment on if they have not been mentioned.

-role of professionals (family-centeredness, communication)

-support from family/friends/neighbours

-family interaction and communication

-coping skills

-personal norms and values (including religion)

-societal norms and values

-characteristics of child with PIMD

-specific needs of different family members